1. Introduction

Primary lung tumors in children are a group of rare and mostly benign lesions that differ in etiology, radiologic, bronchologic, and pathologic features (1). Since patients with malignant lesions usually present with heterogeneous and nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms, diagnostic efforts focus on early recognition and prompt treatment (1). Low incidence, heterogeneity of both local protocols and availability of advanced healthcare protection across the world, and single-center designed studies typically including case reports/series. Lack of international studies on standards of treatment often impedes the adoption of uniform recommendations about diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of those diagnosed with malignant lung masses during childhood.

The inability to establish a diagnosis based solely on clinical characteristics and chest X-ray shifted the focus to more sophisticated diagnostic procedures (2). While chest CT often offers key discriminating features that reliably render the final diagnosis, the overlapping of image patterns has urged for a tool that thoroughly provides the exact interpretation (3). As open-lung biopsy has remained the gold standard, continuous development and introduction of novel high-yield bronchoscopic techniques have facilitated a less invasive but highly trustworthy approach in a histopathologic domain. Nowadays, flexible bronchoscopy with advanced techniques - endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA), cryobiopsy, laser, and cautery—has become an essential diagnostic tool with an ever-developing perspective in the treatment of malignant lesions in selected cases (4–7). Likewise, the ongoing advancement in comprehension of the molecular underpinnings of tumor proliferation has progressively enabled the integration of novel therapeutic agents into clinical practice. These agents target and inhibit specific signaling pathways crucial for cell proliferation and survival (8,9). Although the treatment of malignant lung tumors in children primarily relies on complete surgical resection or, in selected cases, bronchoscopic extraction, the use of innovative drugs that inhibit specific metabolic and biochemical pathways critical for tumor growth may be beneficial for inoperable and disseminated lesions (10). As a result, analyzing tumor tissue for chromosomal rearrangements and genetic variations is among the critical components of contemporary diagnostic methods (8–10).

Nonetheless, managing pediatric patients diagnosed with pulmonary malignancies can be particularly challenging in settings with constrained resources and limited access to advanced diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. Given the paucity of studies on pulmonary malignancies in childhood outside high-income countries, this study primarily aims to propose a diagnostic and therapeutic strategy for primary lung tumors in children within under-resourced healthcare systems.

A secondary objective is to underscore the importance of postoperative histopathological analysis and chromosomal rearrangement testing using specific biomarkers. Due to the high mitotic index and consequent genomic instability of tumor tissue, the emergence of previously undetected chromosomal or genetic alterations is possible. In this context, special attention is given to a case involving a child with type II pleuropulmonary blastoma and a previously unreported genetic variant.

The parents provided written consent for the publication of the data. The local ethics committee approved the conduct and publication of this study (decision number 11140/1 and date of approval: 26 December 2025).

2. Materials and Methods

The study included retrospectively evaluated medical records of the patients diagnosed with primary tumors of the lungs at the Mother and Child Health Institute of Serbia, a national tertiary care university hospital, from 2015 to 2025. Analyzed data included patients' demographics (age, sex), symptoms, results of diagnostic workup (laboratory findings, radiologic and bronchoscopic workup data, histopathologic findings), and treatment, including disease complications and clinical outcomes. Children diagnosed with primary extrapulmonary neoplastic disorders with secondary pulmonary involvement, as well as tumors of vascular origin and tumors stemming from supraglottic structures, met the criteria for exclusion from the study. Moreover, exclusion criteria included primary tumors originating in lymphatic tissue within the thoracic cavity.

2.1. Laboratory findings

A routine initial workup consisted of a complete blood count, electrolytes, liver function tests, inflammatory markers (sedimentation, C-reactive protein, and lactate dehydrogenase), and urinalysis. Supplementary genetic testing on a blood sample would be performed when an underlying syndrome was suspected.

2.2. Chest imaging and metastasis screening

The initial imaging tool used for each patient was a chest X-ray. Additionally, chest X-rays served for disease progression monitoring and assessment following interventional procedures.

The main indications for a chest CT scan included the persistence of radiologic lesions despite conventional antibiotic treatment or a highly suspicious mass, with or without displacement of midline structures. The procedure would be performed under analgosedation and monitored by an anesthesiologist. Based on the CT scan results, the lesions were classified into two topographic categories: intraluminal/endotracheal and peripheral/parenchymal lesions. All three tumor dimensions were expressed in millimeters, while the tissue pattern was classified as either solid or cystic/mixed based on the presence of an air-fluid level or septation within the lesion. A CT scan evaluated the vascular anatomy of the mass by comparing pre- and post-contrast series. Understanding the tumor's regional advancement and the intrathoracic relationships revealed by the chest CT scan was crucial in determining the need for flexible bronchoscopy. Flexible bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy would be performed in all cases of primarily intraluminal lesions and peripheral lesions that showed secondary intraluminal propagation or mass effect with mediastinal shift.

The timing of follow-up chest CT scans was tailored individually, according to the treatment protocol, and typically at the end of treatment or in case of a relapse.

Abdominal ultrasound served as a tool for routine metastasis screening. When the ultrasound findings or clinical signs were suggestive of metastatic lesions elsewhere, CT or NMR would be performed.

2.3. Flexible bronchoscopy (FB)

While the procedure primarily facilitated airway exploration and the collection of BALF for bacteriology and cytology, it also allowed for tissue biopsy in select cases. It provided valuable insights into the macroscopic appearance of the neoplasm, its intraluminal extension, and the degree of stenosis of the large airways. The team performed transbronchial biopsies using forceps combined with suction catheter aspiration or needle aspiration technique, considering at least three obtained tissue samples as adequate. In addition to its diagnostic role, FB had an interventional role. Lobulated or round-shaped endobronchial lesions lacking broad bases and resembling foreign bodies were suitable for endoscopic removal and subsequent histopathological examination.

The procedure was carried out by experienced bronchologists using flexible video bronchoscopes. Each procedure was conducted under general anesthesia after obtaining informed consent from the parents. Bronchoscopic cryobiopsy and EBUS-TBNA were not accessible.

2.4. Treatment modalities

Surgical resection served as the definitive treatment for patients with tumors unsuitable for endoscopic extraction or following recurrence after bronchoscopic removal. The excised tumor tissue was sent for further histopathological, immunohistochemical (IHC), and genetic analysis, making open lung biopsy the final diagnostic procedure.

In cases of unresectable lesions and the presence of metastases, which would preclude an immediate radical surgical approach, the treatment modalities consisted of immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. The intensity, duration, and scope of these treatments depended on the type of primary lesion.

2.5. Histopathological analyses

Tissue samples were processed using routine histopathological techniques, including fixation in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin embedding, and sectioning at 4 µm thickness. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on all samples to evaluate the morphological features. For further characterization, IHC analysis was performed using a tailored panel of antibodies selected based on the morphological features observed in H&E-stained sections to aid in diagnosis and classification. The stained slides were evaluated using bright-field optical microscopy to integrate morphological and immunophenotypic findings.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using JASP statistical software (JASP Team (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.3)[Computer software]). Descriptive data were conveyed using frequency and traditional central tendency indicators. The Kaplan-Meier curve illustrated survival.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical features and laboratory analyses

This study examined seven patients aged two to eighteen, demonstrating a slight male predominance (4/7 or 57% male; 3/7 or 43% female). The mean age at diagnosis was 11.1 years (SD ±5.57). The mean duration from clinical presentation to definitive diagnosis was 5.1 weeks (SD ±4.81), with three weeks as the most common interval, occurring in 4/7 (57%) cases (table 1).

Clinical presentations were nonspecific and heterogeneous. A dry cough was the most frequent symptom (6/7 or 86%), while other signs, such as fever, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and weight loss, were reported in 3/7 (43%) patients, separately or in combination. There were no symptoms of obstruction of the esophagus or the superior vena cava.

Routine laboratory findings were largely unremarkable. Most (5/7 or 71%) exhibited normal leukocyte counts, whereas two patients (a patient diagnosed with carcinoid and one child with inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor) had leukocytosis. Inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase, were elevated in 4/7 (57%) patients. A patient diagnosed with carcinoid during follow-up for a pituitary adenoma underwent analysis for genes associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). However, whole exome sequencing (WES) did not reveal any mutations related to MEN1. The patient diagnosed with pleuropulmonary blastoma was found to have a confirmed DICER1 gene mutation through next-generation sequencing of DNA obtained from a blood sample.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical features.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical features.

| Patient |

Sex |

Age at dg |

Time to dg |

Cough |

Fever |

Dyspnea |

Hemoptysis |

Weight

loss

|

Type of

a tumor

|

| I |

M |

11 y |

3 weeks |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

Carcinoid |

| II |

F |

9 y |

3 weeks |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

IMT |

| III |

F |

2.5 y |

3 weeks |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

PPB II |

| IV |

M |

16 y |

4 weeks |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

NC |

| V |

M |

18 y |

4 months |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

SCC |

| VI |

M |

6.5 y |

4 weeks |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

IMT |

| VII |

M |

15 y |

3 weeks |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

IMT |

3.2. Chest imaging findings

Nonspecific patchy parenchymal opacifications and segmental atelectasis, either unilaterally or bilaterally, were the most prevalent findings alongside a sagittal midline shift, occurring in 4 out of 7 patients (57%). Hilar lymphadenopathy was present in 3 out of 7 cases: one patient had an endotracheal tumor (squamous cell carcinoma), while the other two had primary parenchymal lesions (NUT carcinoma and PPB). However, chest X-rays proved insufficient in differentiating between malignant and benign lesions or in assessing the extent of regional tumor progression.

In contrast, chest CT scans emerged as a reliable diagnostic tool across three critical domains: primary localization, regional tumor advancement, and evaluation of intrathoracic relationships. Among the findings, four out of seven had intraluminal airway neoplasms (57%), and three had primarily parenchymal neoplasms (43%)—table 2. Intraluminal lesions originating from large airways were commonly associated with lobar or segmental atelectasis. Primary parenchymal lesions initially had unilobar localization—either lower lobes or the middle lobe.

Findings of hilar lymphadenopathy were consistent with the chest X-ray results. A solid appearance predominated in 5/7 cases (71%). Interestingly, a patient initially categorized as having a pulmonary abscess was ultimately diagnosed with PPB, characterized by mixed cystic/solid structures on a CT scan.

Minimal ipsilateral pleural effusion was observed in the child diagnosed with NUT carcinoma, while there were no effusions in the remaining cases. Metastases in the liver existed in a child diagnosed with NUT carcinoma.

The decision to pursue transbronchial biopsy depended on CT findings. Intraluminal masses located in large airways underwent transbronchial biopsy by default. Peripheral lesions with mediastinal shift or intraluminal propagation were indications for endoscopy. Notably, the patient with NUT carcinoma met both criteria for transbronchial biopsy, while the child with PPB did not have any of these.

Table 2.

Radiological features of primary lung tumors.

Table 2.

Radiological features of primary lung tumors.

| |

Chest X-rays |

Chest CT scan |

| |

Lobar

/segmental atelectasis

|

Hilar

adenopathy

|

Mediastinal shift

|

Origin

|

Localization

|

Appearance

|

Hilar

adenopathy

|

| I |

+ |

- |

- |

airways |

Intermediate bronchus |

solid |

- |

| II |

+ |

- |

+ |

airways |

Main tracheal carina |

solid |

- |

| III |

- |

+ |

- |

parenchyma |

Left lower lobe |

Mixed

cystic/solid |

+ |

| IV |

+ |

+ |

+ |

parenchyma |

Middle lobe |

solid |

+ |

| V |

- |

+ |

+ |

airways |

Right upper lobe bronchus |

solid |

+ |

| VI |

+ |

- |

+ |

parenchyma |

Right lower lobe |

solid |

+ |

| VII |

+ |

- |

- |

airways |

Left main bronchus |

solid |

- |

3.3. Bronchologic assessment

FB had important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. While each patient underwent airway exploration, 4/7 (57%) patients underwent FB with transbronchial bronchoscopy based on CT findings. Tumors showed two distinct endoscopic patterns:

- round-shaped and lobulated surface characterized by large airway masses with low-grade malignant potential (carcinoid and IMT)

- irregular surface with infiltrative growth and necrotic areas characterized by high-grade malignant lesions (SCC and NUT carcinoma)

No congenital structural airway abnormalities were observed. None of the patients had any major adverse event after the procedure.

3.4. Histopathological findings

The histopathological analysis of the endobronchial biopsy specimen indicated the neuroendocrine origin of the tumor in a child with a carcinoid. Due to the limited size of the biopsy, tumor grading could not be determined; it was noted that grading could be performed on an excisional biopsy. Macroscopic examination of the subsequently resected specimen revealed a polypoid tumor measuring up to 3 mm, protruding into the bronchial lumen measuring 10 mm in diameter. Histopathological analysis confirmed a typical carcinoid/neuroendocrine tumor, grade 1 (

Figure 1). The resection margins were tumor-free.

In all three patients with IMT, the diagnosis was established from endobronchial biopsy specimens by correlating morphological features with immunohistochemical findings (

Figure 2, Patient No. II). Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated ALK1 protein expression in only one of the biopsy specimens. In Patient No. VI, the diagnosis of IMT with a

TFG::ROS1 fusion was confirmed through whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing.

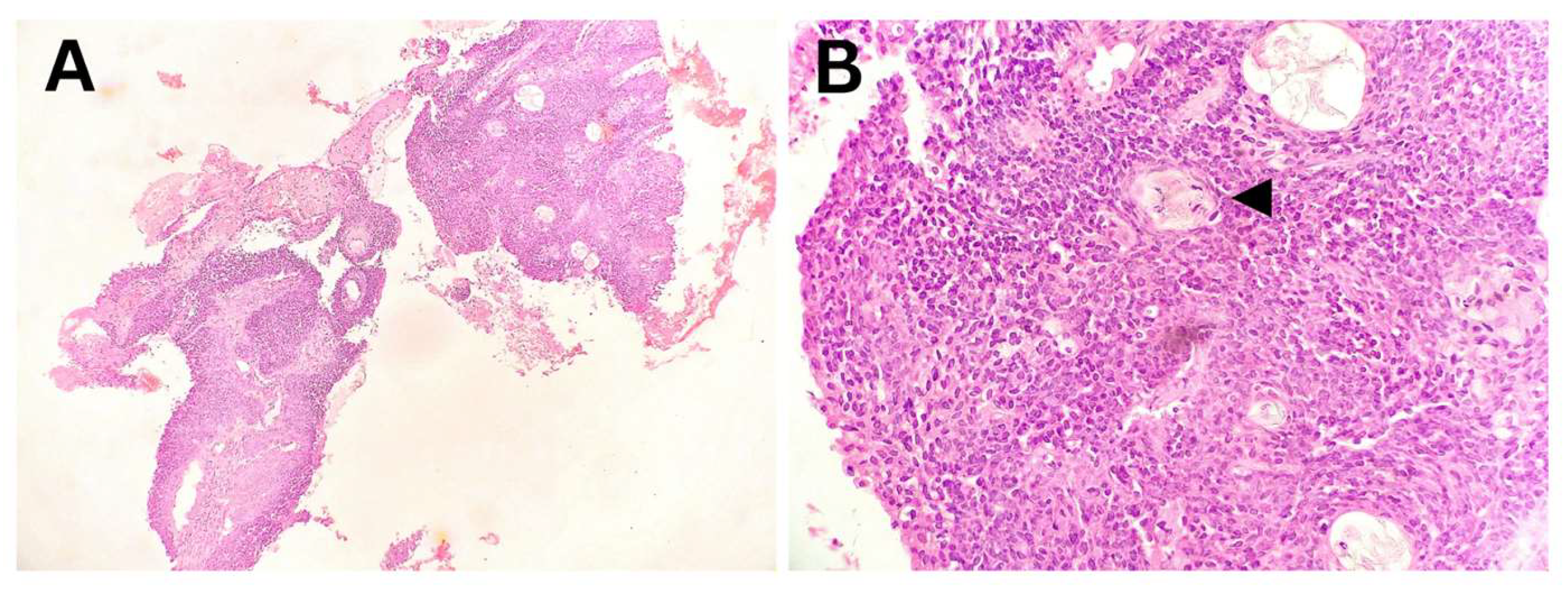

Macroscopically, the tumor nodule in the lobectomy specimen of a child with PPB was well-defined, measuring up to 55 mm, and sharply demarcated from the surrounding lung tissue. The tumor displayed a fleshy consistency, a solid structure, and rare collapsed macrocysts. Histopathological analysis demonstrated a predominant blastemal and sarcomatoid component in solid areas, with multiple microcysts and a few larger macrocysts present (

Figure 3). Correlation with additional IHC findings excluded other differential diagnoses, confirming the diagnosis of PPB type 2, predominantly solid. On the mediastinal side, the tumor was covered by visceral pleura, which was focally absent, resulting in positive surgical margins.

The diagnosis of NUT carcinoma was established from endobronchial biopsy specimens. Morphological analysis indicated carcinoma infiltrating the bronchial wall. The IHC profile of the tumor cells was consistent with non-small cell lung carcinoma, specifically undifferentiated squamous cell carcinoma, with a characteristic NUT protein expression pattern in tumor cells (

Figure 4).

In the child with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, the diagnosis was made based on endobronchial biopsy samples. The degree of differentiation corresponded to a moderately differentiated tumor (

Figure 5). Tumor histogenesis was eventually confirmed by IHC analysis.

3.5. Treatment and outcomes

Four different treatment modalities were employed and often combined to achieve complete remission: neoadjuvant immunotherapy, chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy, minimally noninvasive interventional FB, and invasive radical surgery excision (

Table 3). The final decision on the implemented modality depended on multiple determinants: primary localization and type of tumor, extent of metastatic lesions, and overall health condition.

The therapeutic role of FB came to the fore in two patients with round-shaped large airway masses: carcinoid and one patient with IMT. Namely, the removal of tumors by endoscopic biopsy forceps resulted in the resolution of consolidated and atelectatic lung regions. Nonetheless, recurrent lesions appeared within three months in both cases.

Radical surgical resection via lobectomy was the treatment of choice in children with pleuropulmonary blastoma and in one child with IMT following neoadjuvant immunotherapy, with surgical resection planned subsequently. Additionally, it provided definitive remission in a child with carcinoid tumor after recurrence following initial endoscopic removal.

The role of chemotherapy was double-natured. While it was the only possibility when other therapeutic modalities were not helpful, such as NUT carcinoma, which became disseminated in a few weeks following the diagnosis, anthracycline-based chemotherapy represented the eventual modality for the child with IMT.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy with crizotinib was used in one child with unresectable IMT exhibiting mass effect and a confirmed TFG::ROS1 fusion, in order to achieve tumor shrinkage prior to definitive surgical resection.

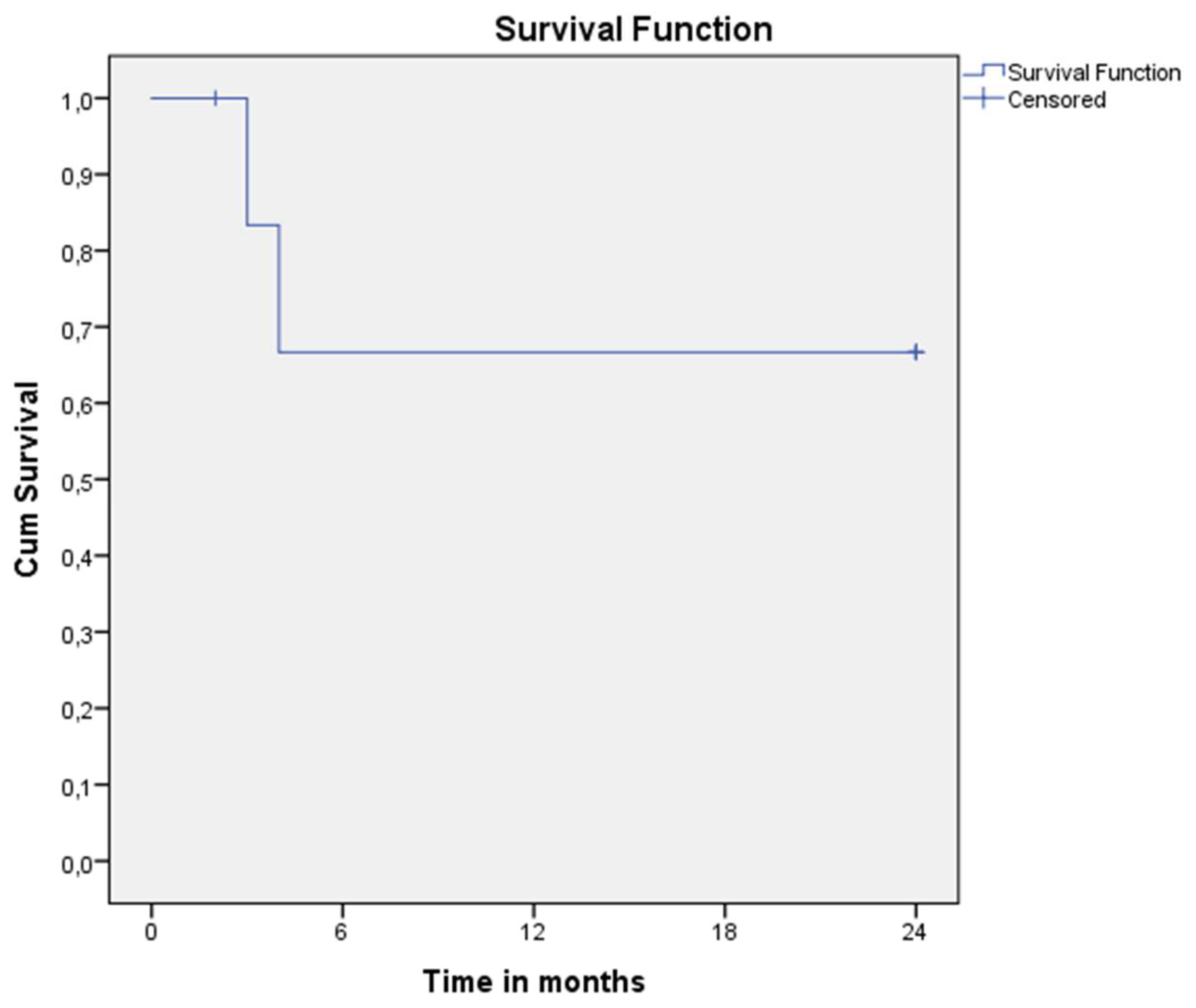

The overall two-year survival was 66.67% (4/7 patients survived, two died, and one was lost to follow-up)—

Figure 6. Mortality resulted from disseminated lesions associated with multiorgan failure within four months after the initial presentation.

4. Discussion

The heterogeneous clinical presentation of primary malignant lung tumors, along with their radiographic characteristics, often precludes a definitive distinction from non-neoplastic changes (11). This uncertainty necessitates the need for histopathological analysis of biopsy samples, which is crucial for establishing a definitive diagnosis that guides treatment and predicts the prognosis of the disease (12).

Although chest CT scans cannot reliably indicate the type of tumor, this procedure is paramount for assessing the size of the lesion, its relationship with surrounding structures, and the origin of its blood supply (13). Particular focus is on features that help distinguish between malignant and benign lung tumors. While bilateral distribution strongly indicates a malignant process, hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy, tumor size, and appearance do not always reliably indicate malignancy (13). Metastases to nearby and distant lymph nodes may occur irrespective of an apparent absence of radiological lymphadenopathy (14). Conversely, malignant lung tumors may initially be interpreted as non-neoplastic pathological changes on CT imaging, potentially delaying timely intervention and increasing the risk of a poor outcome (15). Preoperative diagnostic reliability for malignant lesions depends on device technical aspects, radiologist experience, and lung pathology. Reported overall accuracy rates below 80%—especially regarding discrimination between PPB and congenital pulmonary airway malformation - may impose significant challenges and have urged for a novel approach based on multiple diagnostic tools (16). To minimize the risk of delayed diagnosis in cases of an unrecognized tumor or, conversely, the unnecessary application of invasive therapeutic procedures in a child with non-neoplastic pathology, integrated algorithms utilize a combination of radiological (sagittal structure displacement and vascularity of the lesion), bronchoscopic, and genetic analyses from a serum blood sample alongside chest CT scans (12,17). In type 1 PPB, this approach has resulted in nearly 100% positive and negative predictive values for distinguishing it from congenital pulmonary airway malformation type IV (18). Unfortunately, diagnostic algorithms for solid tumor formations are not as widely developed as those for cystic lesions. Thus, a tissue sample is subjected to histological investigation to establish a definitive diagnosis. Presuming that surgical resection is the most common form of definitive treatment, postoperative tissue analysis remains the gold standard for final diagnosis (16). Although reliable, this method of determining the nature of observed changes has its drawbacks; primarily, it involves an invasive surgical approach and, by its nature, excludes definitive knowledge of the neoplasm type in the preoperative period. Flexible bronchoscopy has led to a significant advancement in the diagnostic domain (19,20).

The minimally invasive nature of flexible bronchoscopy, coupled with technical advancements that have minimized adverse effects of the procedure, allows for the visualization of endoluminal propagation and the macroscopic appearance of the tumor mass (19). Although there was a correlation between the macroscopic appearance of the tumor mass and the degree of malignancy in our series of patients—where a lobulated structure with a smooth surface indicated low-grade malignancy and an irregular surface with infiltrative growth suggested high-grade malignancies — literature review has not established the reliability of such a method for distinguishing the malignant potential of tumor lesions (21). Nevertheless, observation of the macroscopic appearance of the endoluminal mass contributes to a decision about the feasibility of endoscopic tumor extraction, which could potentially obviate the need for aggressive approaches with classical surgical techniques. Notably, endoscopic extraction may be considered in selected cases where the tumor mass is unifocal, does not infiltrate surrounding structures, and does not affect adjacent lymph nodes (6,22). Novel bronchoscopic advancements secured a safe approach, but the possibility of the tumor's regrowth seeks attention and definitive treatment with either surgical excision or chemotherapy (6,22).

Although advances in surgical and endoscopic techniques enabled better overall treatment and prognosis for children with malignant lung neoplasms, a better understanding of cell biology directed therapeutic focus to novel agents targeting specific genes and molecules essential for cell cycle control. However, numerous molecular findings are still of unknown significance and demand a future investigation. Besides the well-known DICER1 gene mutation associated with pleuropulmonary blastoma that is important for both familial and individual genetic screening, concomitant detection of the EWSR1/ERG gene rearrangement in one patient has not been described so far in this type of tumor. Typically involved in Ewing sarcoma genesis, this gene fusion is the subject of thorough investigations with the potential to become a target for innovative therapy (23). The use of crizotinib in the child with IMT exemplifies the synthesis of basic molecular findings with the practical application of an innovative targeted agent, serving as neoadjuvant therapy in primary unresectable lesions. Clearly, future prospective trials are crucial to assess the effectiveness of novel therapies targeting specific genetic rearrangements in tumor tissue, particularly in cases of previously inoperable and treatment-resistant tumors, especially when used as part of neoadjuvant therapy.

5. Conclusions

Primary malignant lung tumors remain a rare and challenging entity that often clinically and radiologically mimics nonmalignant lung pathology. The combination of radiologic, bronchoscopic, histopathological, and genetic testing yields high diagnostic accuracy for tumor type and dissemination. While traditional therapeutic modalities offer definitive curation in most patients, innovative therapy aiming at essential molecules necessary for cell proliferation may become the preferred treatment for selected patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MB and AS; methodology, MB, AS and NM; software, MB, NM; investigation, MB, NM, DA, GS, MS, ID, MDF, TG, AS; resources, NM, DA, GS, MS, ID, MDF, AS; writing—original draft preparation, MB; writing—review and editing, MB, NM, DA, GS, MS, ID, MDF, TG, AS; visualization, MB, NM, DA, GS, MS, ID, MDF, TG, AS; supervision, AS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Mother and Child Health Care Institute of Serbia (protocol code 11140/1 and date of approval: 26 December 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Jelena Visekruna and Dr Milan Rodic (Department of Pulmonology, Mother and Child Health Care Institute of Serbia, Dr. Dejana Bozic (Pathology Department, Mother and Child Health Institute of Serbia), and Danka Redzic (Department of Hemato-Oncology, Mother and Child Health Care Institute of Serbia) for their invaluable clinical insights and support throughout this work. Their expertise and dedication greatly contributed to the depth and accuracy of the clinical aspects presented here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EBUS-TBNA |

endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration |

| FB |

Flexible bronchoscopy |

| CT |

computed tomography |

| MR |

magnetic resonance |

| IHC |

immunohistochemical |

| MEN1 |

multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 |

| WES |

whole exome sequencing |

| IMT |

inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor |

| PPB |

pleuropulmonary blastoma |

| NC |

NUT carcinoma |

| SCC |

squamous cell carcinoma |

| ALK1 |

activin receptor-like kinase 1 |

Appendix A

Figure 1.

Typical carcinoid/neuroendocrine tumor, Grade 1 – Excisional biopsy. (A) Macroscopic cross-section of the bronchus showing a polypoid tumor within the lumen. (B) Ulcerated polypoid tumor infiltrating the bronchial wall. (C) Tumor infiltration extending to the boundary with the cartilage. (D) Organoid nests and trabeculae of tumor cells with "salt-and-pepper" chromatin and low mitotic activity. (E, F, G) Immunohistochemical positivity for CD56, Synaptophysin, and Chromogranin, respectively. (H) Proliferative marker Ki-67 positive in fewer than 4–5% of tumor cells.

Figure 1.

Typical carcinoid/neuroendocrine tumor, Grade 1 – Excisional biopsy. (A) Macroscopic cross-section of the bronchus showing a polypoid tumor within the lumen. (B) Ulcerated polypoid tumor infiltrating the bronchial wall. (C) Tumor infiltration extending to the boundary with the cartilage. (D) Organoid nests and trabeculae of tumor cells with "salt-and-pepper" chromatin and low mitotic activity. (E, F, G) Immunohistochemical positivity for CD56, Synaptophysin, and Chromogranin, respectively. (H) Proliferative marker Ki-67 positive in fewer than 4–5% of tumor cells.

Figure 2.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung – Endobronchial biopsy. (A) Bronchial wall with surface squamous metaplasia infiltrated by tumor tissue. (B) Uniform spindle-shaped tumor cells with myofibroblastic morphology intermixed with inflammatory cells. (C) Immunohistochemical positivity of tumor cells for smooth muscle actin. (D) Immunohistochemical positivity of inflammatory cells for leukocyte common antigen.

Figure 2.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung – Endobronchial biopsy. (A) Bronchial wall with surface squamous metaplasia infiltrated by tumor tissue. (B) Uniform spindle-shaped tumor cells with myofibroblastic morphology intermixed with inflammatory cells. (C) Immunohistochemical positivity of tumor cells for smooth muscle actin. (D) Immunohistochemical positivity of inflammatory cells for leukocyte common antigen.

Figure 3.

Pleuropulmonary blastoma, Type 2, predominantly solid – Excisional biopsy. (A) Macroscopic appearance of a solid tumor with a collapsed macrocytic area (arrowhead). (B) Solid tumor component composed of blastematous and sarcomatoid elements. (C) Primitive, undifferentiated blastematous cells with numerous mitotic figures. (D) Sarcomatoid fibromyxoid component with foci of chondroid differentiation. (E) Zones of anaplasia with atypical mitotic figures and rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. (F) Multiple microcysts surrounded by condensed blastematous cells.

Figure 3.

Pleuropulmonary blastoma, Type 2, predominantly solid – Excisional biopsy. (A) Macroscopic appearance of a solid tumor with a collapsed macrocytic area (arrowhead). (B) Solid tumor component composed of blastematous and sarcomatoid elements. (C) Primitive, undifferentiated blastematous cells with numerous mitotic figures. (D) Sarcomatoid fibromyxoid component with foci of chondroid differentiation. (E) Zones of anaplasia with atypical mitotic figures and rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. (F) Multiple microcysts surrounded by condensed blastematous cells.

Figure 4.

NUT carcinoma of the lung – Endobronchial biopsy. (A) Bronchial wall with surface squamous metaplasia infiltrated by tumor tissue. (B, C) Immunohistochemical positivity of tumor cells for CK AE1/AE3 and p63, respectively. (D) Proliferative marker Ki-67 positive in approximately 60% of tumor cells. (E, F) Characteristic nuclear dot-like positivity of tumor cells for NUT protein.

Figure 4.

NUT carcinoma of the lung – Endobronchial biopsy. (A) Bronchial wall with surface squamous metaplasia infiltrated by tumor tissue. (B, C) Immunohistochemical positivity of tumor cells for CK AE1/AE3 and p63, respectively. (D) Proliferative marker Ki-67 positive in approximately 60% of tumor cells. (E, F) Characteristic nuclear dot-like positivity of tumor cells for NUT protein.

Figure 5.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, moderately differentiated – Endobronchial biopsy. (A) Tissue fragments with nests of infiltrative tumor growth. (B) Smaller epithelial tumor cells with a focus of squamous differentiation (arrowhead).

Figure 5.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, moderately differentiated – Endobronchial biopsy. (A) Tissue fragments with nests of infiltrative tumor growth. (B) Smaller epithelial tumor cells with a focus of squamous differentiation (arrowhead).

References

- Özkan, M. Pulmonary tumors in childhood. Turk Gogus Kalp Damar Cerrahisi Derg. 2024, 32 (Suppl 1), S73–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, P.; Pio, L.; Torre, M. Primary tracheobronchial tumors in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2016, 25, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenberger, J.P.; Biko, D.M.; Carter, B.W.; Pavio, M.A.; Huppmann, A.R.; Chung, E.M. Primary lung tumors in children: Radiologic-pathologic correlation from the Radiologic Pathology Archives. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc. 2018, 38, 2151–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M.B.; Sugarbaker, E.A. Bronchoplasty for pulmonary preservation: A novel technique. JTCVS Tech. 2023, 19, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Schaefer, E.; Rosenblum, J.; Stewart, F.D.; Arkovitz, M.S. Intraoperative electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (IENB) to localize peripheral lung lesions: A new technique in the pediatric oncology population. J Pediatr Surg. 2022, 57, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, N.; Tao, M.; Li, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, H.; et al. Application of interventional bronchoscopic therapy in eight pediatric patients with malignant airway tumors. Tumori. 2012, 98, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaric, B.; Stojsic, V.; Sarcev, T.; Stojanovic, G.; Carapic, V.; Perin, B.; et al. Advanced bronchoscopic techniques in diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2013, 5 (Suppl 4), S359–S370. [Google Scholar]

- Imyanitov, E.N.; Iyevleva, A.G.; Levchenko, E.V. Molecular testing and targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: Current status and perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021, 157, 103194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Brambilla, E.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Sage, J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2021, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Hanna, N. Advances in systemic therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. BMJ. 2021, 375, n2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, A.; Pederiva, F. Association between congenital lung malformations and lung tumors in children and adults: A systematic review. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2016, 11, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudin, E.; Caplin, M.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Fazio, N.; Ferolla, P.; Filosso, P.L.; et al. Lung and thymic carcinoids: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2021, 32, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.I.; Lee, E.Y. Pediatric pulmonary nodules: Imaging guidelines and recommendations. Radiol Clin North Am. 2022, 60, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarraf, N.; Gately, K.; Lucey, J.; Wilson, L.; McGovern, E.; Young, V. Lymph node staging by means of positron emission tomography is less accurate in non-small cell lung cancer patients with enlarged lymph nodes: Analysis of 1,145 lymph nodes. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2008, 60, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.H.; Chen, H.C.; Chung, F.T.; Lo, Y.L.; Lee, K.Y.; Wang, C.W.; et al. Diagnostic value of EBUS-TBNA for lung cancer with non-enlarged lymph nodes: A study in a tuberculosis-endemic country. PloS One. 2011, 6, e16877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunisaki, S.M.; Lal, D.R.; Saito, J.M.; Fallat, M.E.; St Peter, S.D.; Fox, Z.D.; et al. Pleuropulmonary blastoma in pediatric lung lesions. Pediatrics. 2021, 147, e2020028357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos Vieira Abib, S.; Chui, C.H.; Cox, S.; Abdelhafeez, A.H.; Fernandez-Pineda, I.; Elgendy, A.; et al. International Society of Paediatric Surgical Oncology (IPSO) surgical practice guidelines. Ecancermedicalscience. 2022, 16, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, A.; Hall, N.J.; Williams, G.M.; Schultz, K.A.P.; Miniati, D.; Hill, D.A.; et al. Can congenital pulmonary airway malformation be distinguished from type I pleuropulmonary blastoma based on clinical and radiological features? J Pediatr Surg. 2016, 51, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccione, J.; Hysinger, E.B.; Vicencio, A.G. Pediatric advanced diagnostic and interventional bronchoscopy. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2021, 30, 151065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, A.; Franklin, S.; Hysinger, E.; Goldfarb, S.; Phinizy, P.; Pogoriler, J.; et al. Diagnostic yield of endobronchial ultrasound and virtual CT navigational bronchoscopy for biopsy of pulmonary nodules, mediastinal lymph nodes, and thoracic tumors in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadig, T.R.; Thomas, N.; Nietert, P.J.; Lozier, J.; Tanner, N.T.; Wang Memoli, J.S.; et al. Guided bronchoscopy for the evaluation of pulmonary lesions: An updated meta-analysis. Chest. 2023, 163, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.M.; Yin, J.; Li, G.; Liu, X.C. Clinical features and interventional bronchoscopic treatment of primary airway tumor in 8 children. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi Chin J Pediatr. 2021, 59, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.S.; Morsberger, L.; Hardy, M.; Ghabrial, J.; Stinnett, V.; Murry, J.B.; et al. Complex/cryptic EWSR1::FLI1/ERG gene fusions and 1q jumping translocation in pediatric Ewing sarcomas. Genes. 2023, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).