1. Introduction

The fractal theory, with its inherent geometric characteristics of self-similarity and scale invariance, has provided a robust mathematical framework for examining non-linear scientific phenomena. This theory, breaking away from the confines of Euclidean geometry, has offered scientists an effective means of describing irregular phenomena mathematically. In compression technology, the redundancy found among pixels and within structural textures is closely linked to self-similarity. This link naturally lends itself to applying fractal theory in image compression. Exploring scientific theories led American scholar Barnsley [

1] to establish the mathematical foundation for fractal image compression technology, effectively initiating the fractal image compression research field. Subsequently, in 1992, Jacquin proposed an enhanced algorithm named Basic Fractal Image Compression (BFIC) [

2]. Jacquin’s improvement scheme employs a partitioned Iterative Function System (IFS) [

3] to autonomously search for affine transformation information, eliminating the need for human-computer interaction and extending its applicability to general natural images.

However, the BFIC is recognized for its relatively high encoding time during optimal block matching. Consequently, numerous practical fast fractal image compression coding algorithms have been proposed and developed in current research. These methods often originate from spatial relationships and utilize neighborhood approaches [

4,

5] to identify correlations between R-blocks and D-blocks. Wang et al. [

6] introduced an asymptotic strategy based on quadtree partition and enhanced neighborhood searching, which marginally reduces encoding time and achieves a higher compression ratio. Methods have also been developed to classify feature data extracted from R-blocks and D-blocks based on texture information or statistical features [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Notably, the quadtree fractal image compression (QFIC) scheme proposed by Fisher [

11] categorizes R-blocks and D-blocks into 72 groups based on block brightness levels. Wang Xing-Yuan et al. [

12] later proposed using the plane fitting coefficient of a block to determine if a D-block is sufficiently similar to a given R-block, significantly reducing the encoding time. Additionally, typical optimization algorithms such as the genetic algorithm [

13] or a hybrid of Ant Lion Optimization (ALO) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [

14] can also decrease encoding time. Tang et al. [

15] proposed an adaptive super-resolution image reconstruction technique based on fractal theory, integrating the wavelet’s multi-scale analysis capabilities with the multi-scale self-similarity trait of fractals and leveraging investigations into the local fractal dimension. Finally, L.-F. Li et al. [

16] proposed a fast fractal image compression algorithm based on the centroid radius to address the high encoding time associated with conventional fractal encoding algorithms.

The previously discussed fractal image compression techniques often falter in capturing the self-similarity and intricate details in images characterized by rich textures and detailed structures. This shortfall usually results in reconstructed images that lack realism and naturalness. Moreover, these conventional methods predominantly employ fixed-size segmentation approaches, which are inflexible and do not adjust based on the local attributes of the image content. Such rigidity challenges preserving crucial details in certain regions while creating unnecessary redundancy in others. To overcome the limitations of fixed-size block segmentation and better accommodate image textures and features, we introduce an enhanced fractal image compression algorithm based on the adaptive non-uniform rectangle partition (FICANRP). This novel approach adaptively segments the image into variable-sized range blocks (R-blocks) and non-overlapping domain blocks (D-blocks), taking cues from local textures and features through the adaptive non-uniform rectangle partition. Empirical results indicate that FICANRP enhances image reconstruction quality, reduces encoding duration, and achieves a superior compression ratio. The primary contributions of this paper are encapsulated as follows:

1. We propose utilizing the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition algorithm to segment images into non-overlapping D-blocks guided by local textures and features. This approach results in D-blocks of varying sizes and categorizes them based on block dimensions, ultimately effectively reducing the pool of D-blocks and matching scope while improving the compression ratio and match precision.

2. We design and use the non-uniform partition algorithm to adaptively segment images into different-sized R-blocks. Small R-blocks reconstruct regions with complex textures, while large R-blocks reconstruct areas with smooth or straightforward textures. The variable block size can help compress images, reduce “block effects” more effectively, and improve image reconstruction quality and compression ratio.

3. We propose a novel block similarity matching algorithm that incorporates precomputing. This approach entails summing pixel values for each D-block before conducting the R-block similarity match. This approach avoids redundant calculations during the loop-matching process, reducing computational complexity and encoding time.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a succinct overview of the fundamental methodologies associated with fractal image compression and non-uniform rectangular partition.

Section 3 presents a comprehensive examination of the fractal image compression techniques predicated on adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition, accompanied by an in-depth analysis of our proposed algorithms.

Section 4 thoroughly assesses the compression algorithms’ performance, examining a range of parameters and presenting the associated experimental results. Finally,

Section 5 outlines the conclusions drawn from this study.

2. The Fractal Image Compression and Non-Uniform Rectangular Partition

Fractal image compression leverages images' self-similarity and local repetition, significantly reducing data volume by storing pattern descriptors rather than individual pixel values. The non-uniform partition is adaptable to the varying characteristics across different image regions. Segmenting images into adaptable blocks of various sizes and shapes effectively captures nuanced changes, particularly within areas featuring complex textures or irregular structures, thereby markedly improving data compression efficiency.

2.1. The Fractal Image Compression

The fractal image compression algorithm primarily relies on the iterative function system(IFS) and the collage theorem [

17] to construct a fractal representation of images. This algorithm analyzes local similarities within an image, searching for suitable affine transformations. It then establishes corresponding fractal codes to minimize any discrepancies between the original image and its fractal reconstruction. Fractal image compression coding aims to identify a series of compression mappings for a given image, thereby creating an IFS that closely approximates the original image by retaining its key parameters. In this context, we present the BFIC algorithm, which is broadly divided into three stages: image segmentation, compressed affine transformation, and decoding reconstruction.

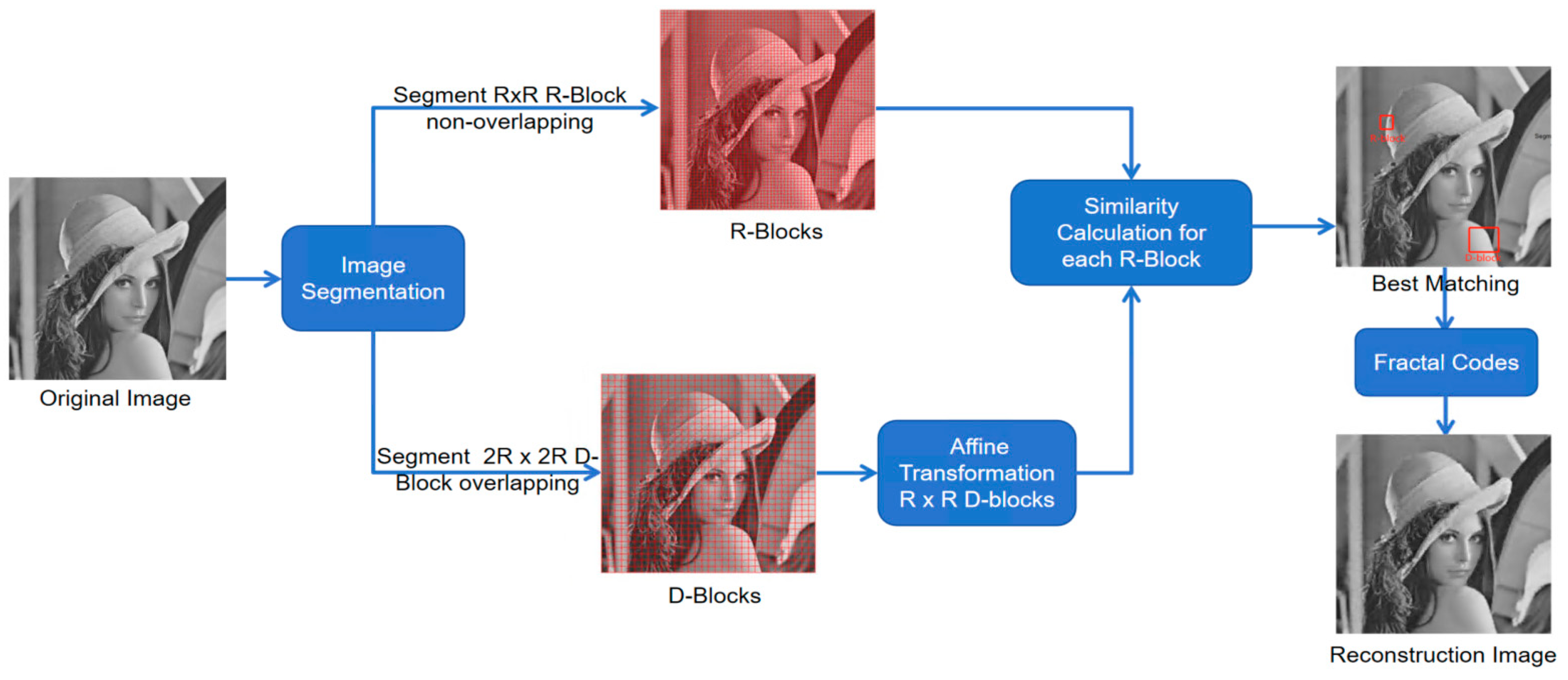

Figure 1.

Process of BFIC with fixed R-block size (8×8) and D-block size (16×16).

Figure 1.

Process of BFIC with fixed R-block size (8×8) and D-block size (16×16).

2.1.1. Image Segmentation

In the BFIC algorithms, a prevalent technique is utilizing a basic fixed-size block segmentation method. Here, the original image is partitioned into non-overlapping R-blocks and overlapping D-blocks. The R-blocks, segmented with dimensions RR, form the encoded R-blocks. These blocks symbolize specific image regions intended for approximation via fractal coding. The desired compression ratio and the image characteristics determine the size of the R-blocks. Conversely, D-blocks are divided into dimensions DD with a sliding step length of δ. A sliding window approach is employed horizontally and vertically across the image to generate these overlapping D-blocks.

In general, the size of the D-block is four times larger than the R-block (D=2R), which facilitates a more flexible and precise matching process. The sliding step length δ (δ=R) dictates the overlap between contiguous D-blocks and influences the pool of D-blocks density. A smaller step length yields a larger pool of D-blocks with more potential transformations, whereas a larger step length results in a denser pool of D-blocks with fewer alternatives. During the encoding phase, each R-block is juxtaposed against the D-blocks to identify the most visually similar match. The affine transformation parameters that align the best-matching D-block with the R-block are meticulously recorded.

2.1.2. Affine Transformation

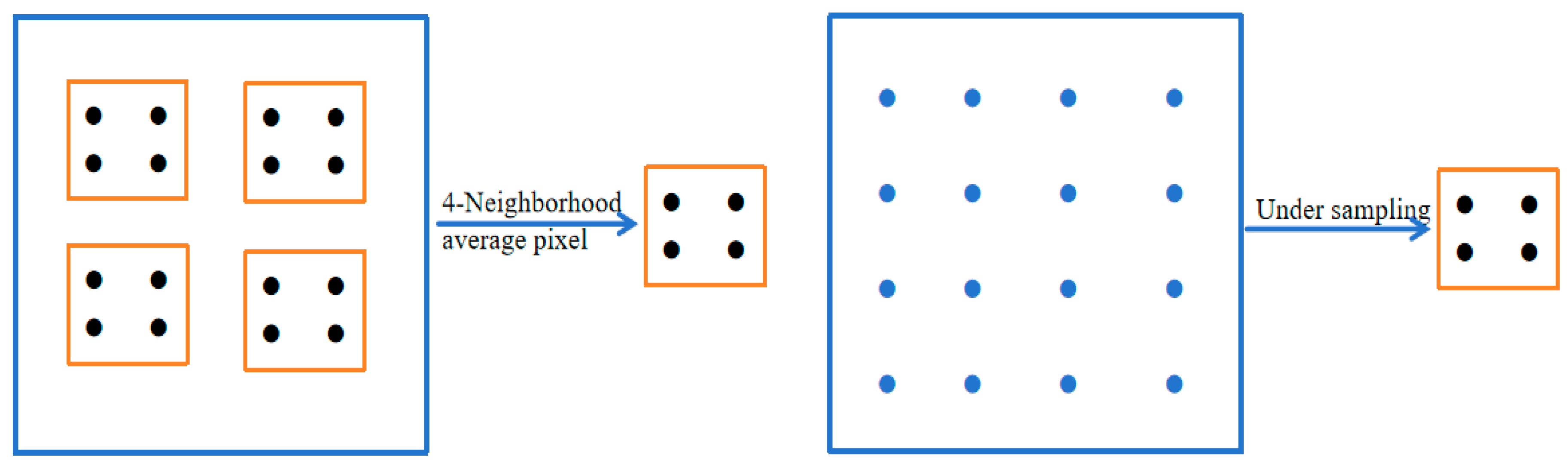

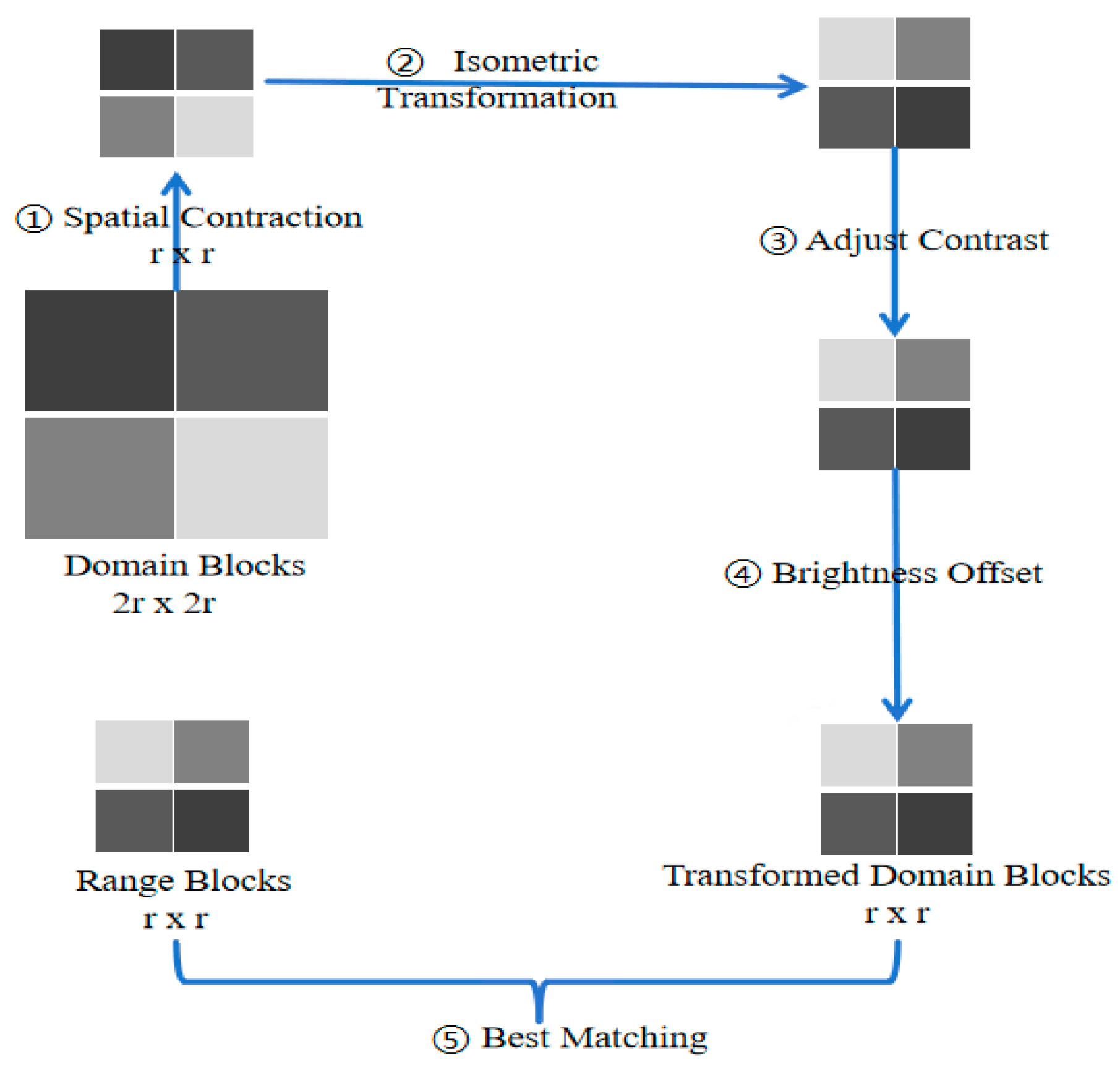

The encoding stage of fractal compressive affine transformation can be conceptualized as a process involving spatial compression, isometric transformation, and grayscale matching search. Regarding spatial compression, the size of D-blocks must be decreased to match that of R-blocks for a proportional comparison. This is typically achieved using standard technologies such as pixel averaging and undersampling methods, as depicted in

Figure 2.

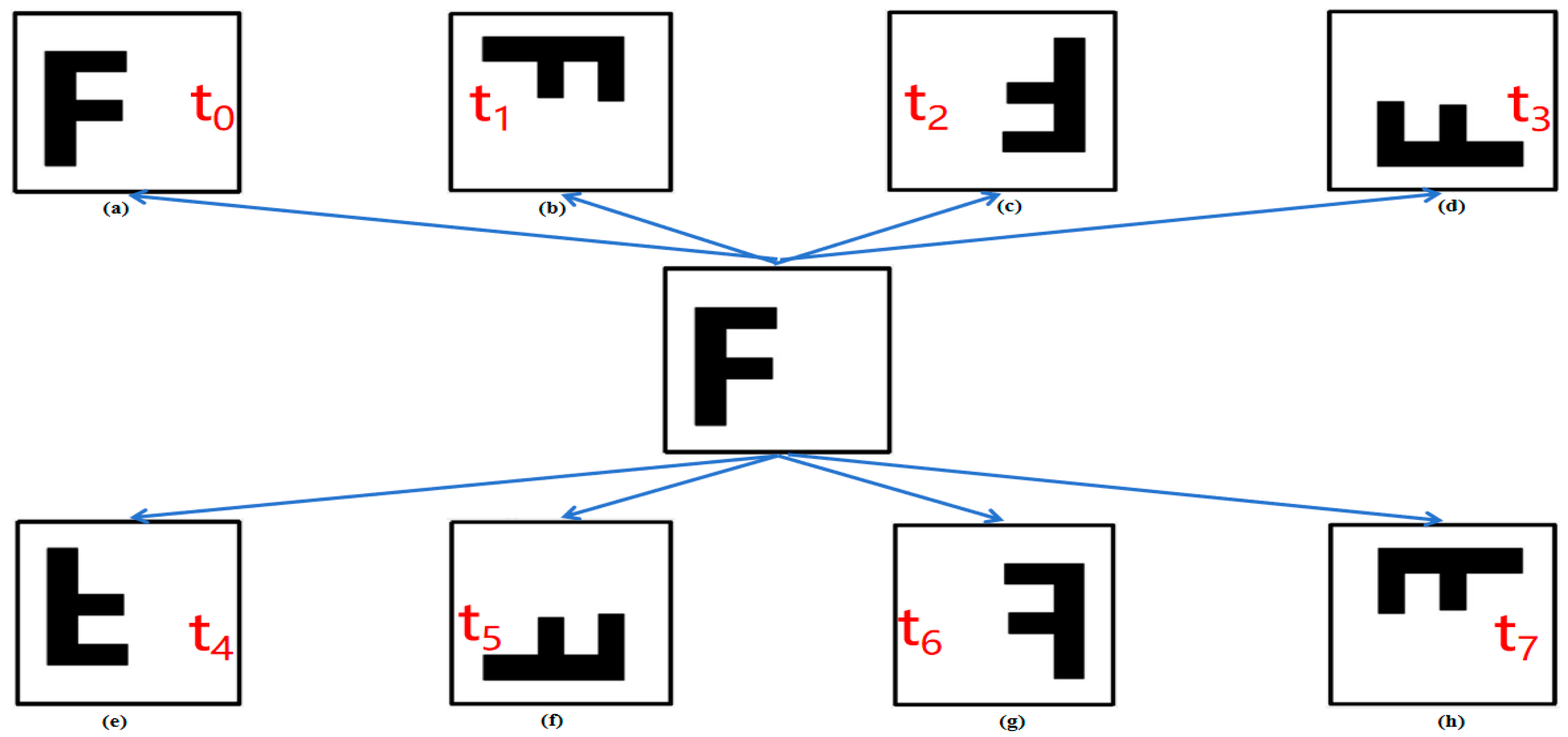

The isometric transformation guarantees that the fundamental geometric properties of the D-blocks are preserved despite resizing. This maintains the self-similar characteristics vital for fractal image compression coding. To enhance the quality of image reconstruction, we employed eight distinct isometric transformations, denoted as ( i=0,1, , 7) to augment the pool of D-blocks. These include:

- (1)

Identity transformation

:

; as show in

Figure 3(a).

- (2)

Rotate 90 degrees clockwise

:

; as show in

Figure 3(b).

- (3)

Rotate 180 degrees clockwise

:

; as show in

Figure 3(c).

- (4)

Rotate 270 degrees clockwise

:

; as show in

Figure 3(d).

- (5)

Symmetric reflection on x

:

; as show in

Figure 3(e).

- (6)

Symmetric reflection on y=x

:

; as show in

Figure 3(f).

- (7)

Symmetric reflection on y

:

; as show in

Figure 3(g).

- (8)

Symmetric reflection on y=-x

:

; as show in

Figure 3(h).

Finally, a grayscale matching search is performed on each R-block to find the best matching D-block, as well as the corresponding contrast factor

Fs and brightness offset coefficient

Fo, so that the R-block and the best matching D-block meet the following grayscale transformations.

Simultaneously meeting the minimum matching error, i.e.

Wherein ||•|| represents an L2-norm;

is a constant block with grayscale values 1. By using the least squares method(LSM) to solve

, which can obtain:

Wherein

represents the Euclidean inner product,

and

represent the mean of the grey pixel of R-blocks and D-blocks, respectively. If

, then

Fs = 0,

Fo =

. So, the fractal codes for R-block include the coordinate position of D-block (Dt

x, Dt

y), isometric transformation

Tw, contrast factor

Fs, and brightness offset coefficient

Fo. Therefore, the reconstruction structure of the fractal codes is

Fs, Fo, Tw, Dtx, Dty. The detailed compression affine transformation process is shown in

Figure 4.

2.1.3. Decoding and Reconstruction

The process of decoding and reconstruction adheres to the iteration and collage method, starting from an arbitrary initial image, denoted as

and executing

N iterations as directed by a predetermined fractal code. The image that has been reconstructed, labeled as

, can be considered an approximate fixed point of the compression transformation

W, as outlined by the fractal codes. This mathematical model is represented as:

In each iteration, the functional relationship between

and its best matching block

are as follow:

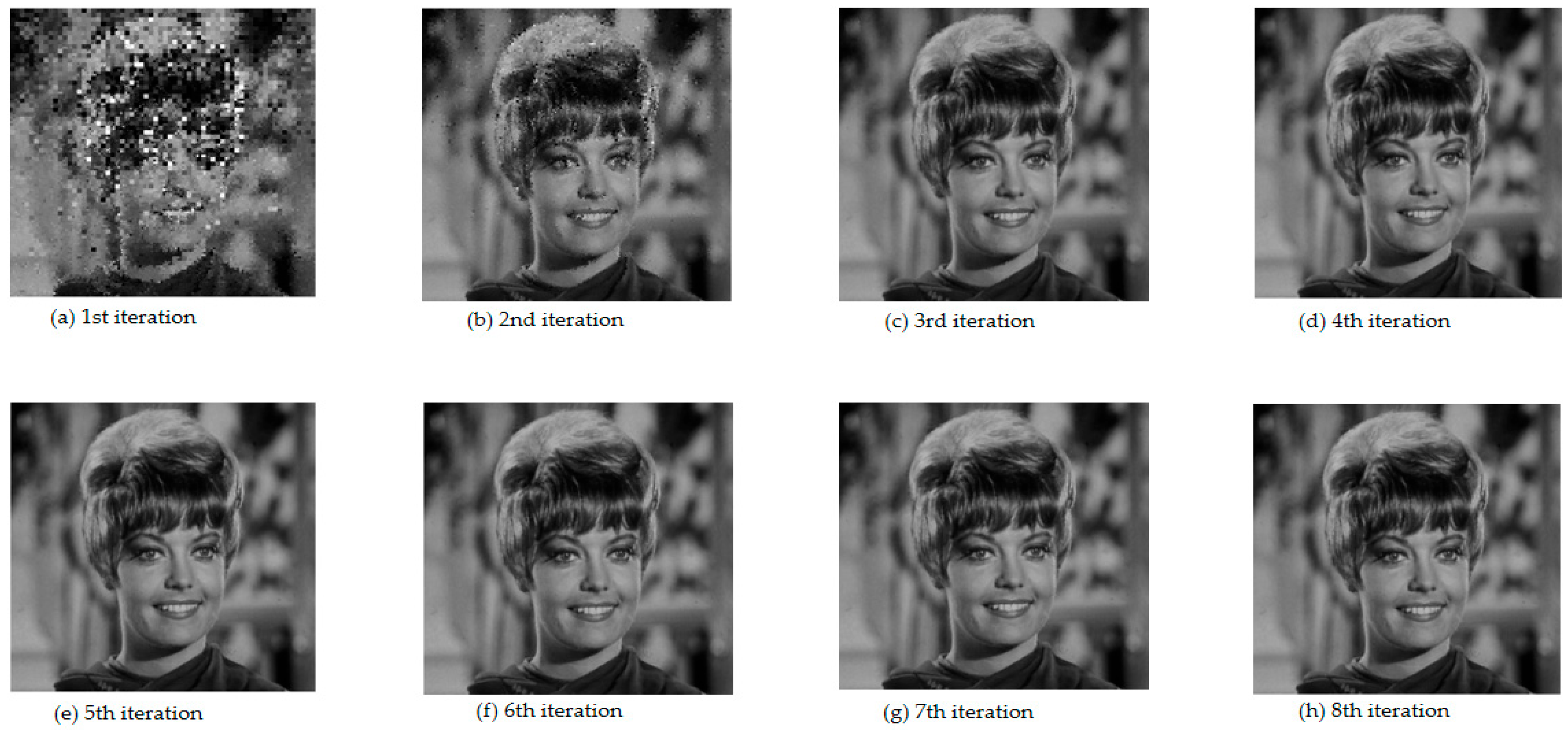

After fractal image compression encoding, the generated fractal codes are used for image reconstruction. After 8-10 iterations, the image reconstruction quality remained stable, and there was no significant change in the reconstruction image’s PSNR. The following is the transformation process of the Zelda image generated in the first eight iterations, and the iterative reconstruction process is shown in

Figure 5.

2.2. The Non-Uniform Rectangular Partition

The non-uniform partition is a digital signal processing and reconstruction technique that includes non-uniform rectangular and triangular partitions based on the configuration of the partition grid. The concept and methodology of non-uniform partitions were introduced in 1971 by A.V. Oppenheim et al. [

18]. They proposed an algorithm utilizing the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to compute the Z-transform of non-uniformly distributed sampling points on the unit circle. This laid the groundwork for spectrum analysis with non-uniform spectral accuracy via the Non-uniform Discrete Fourier Transform (NDFT) [

19]. The NDFT operates on the principle of non-uniform spectrum sampling and allows flexibility in selecting the position of the sampling point on the Z plane. Subsequent developments have introduced various methods of non-uniform partition, such as the Non-uniform Discrete Fourier Transform (NDFT) [

20], Non-uniform Wedgelet Decomposition (NWD) [

21], Non-uniform V-Transformation (NVT) [

22], Non-Uniform Rectangular Partition (NURP) [

23], and Non-Uniform Triangle Partition (NUTP) [

24]. Furthermore, Zhang et al. proposed an image compression and reconstruction algorithm known as APUBT3-NUP [

25], rooted in a non-uniform rectangular partition and U-system. This algorithm’s adaptive partitioning capability enhances the capture of image textures and features, yielding a superior compression ratio and reconstruction quality compared to traditional JPEG methods. These discoveries underscore the unique advantages and potential applications of the non-uniform partition concept.

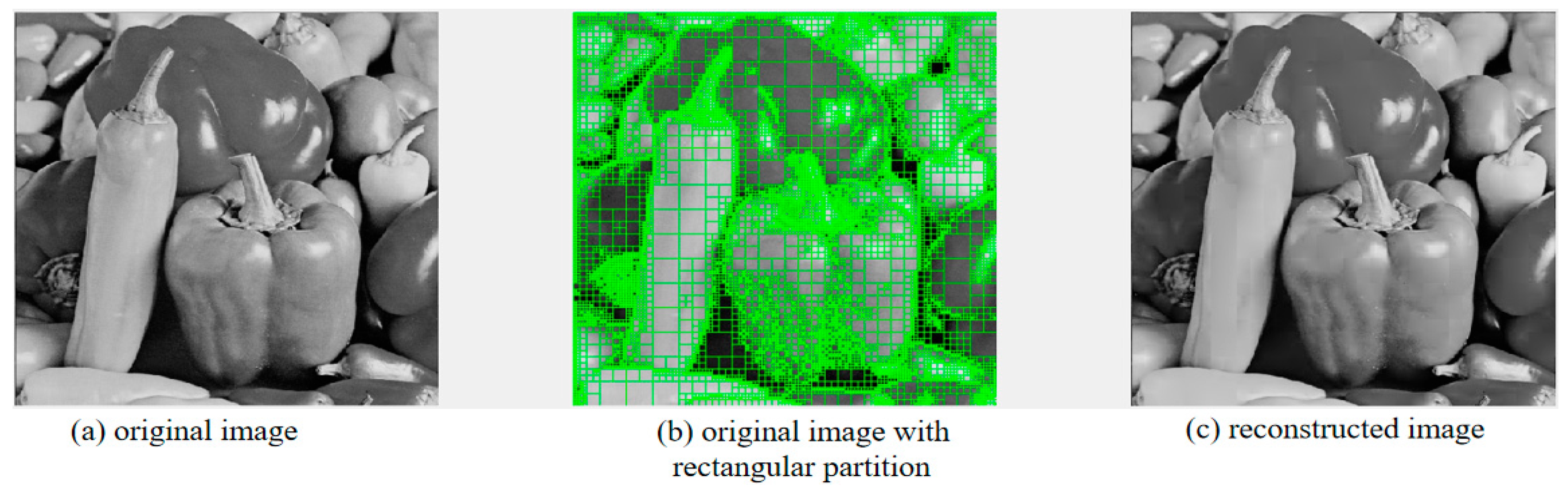

Practical evidence supports the efficacy of the non-uniform rectangle partition algorithm in adaptively dividing images of varying sizes based on local textures and features, utilizing the self-similar partition rule. This allows for rapid image reconstruction with enhanced quality. The methodology is rooted in the concept of least square approximation [

26] via a polynomial function, which improves signal quality. Given a predetermined control threshold and initial region partition, the digital signal can be adaptively subdivided into diverse sizes, showcasing different textures and features, guided by the self-similar partition rule. This non-uniform partition approach has widespread applications in digital signal processing, including curve reconstruction [

27], image representation [

28], image compression [

29], image denoising [

30], image fusion [

31], image super-resolution [

32], information steganography [

33], and image watermarking [

34].

In the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition algorithm context, three critical parameters influence any dimensional signal's partitioning efficiency and reconstruction accuracy. First, the initial partition scheme is crucial as variations in initial partitions can alter the configuration of partition grids and subsequently impact reconstruction parameters. Second, the predefined control threshold significantly affects the number of partition times and directly affects reconstruction quality. Finally, the polynomial function, which utilizes the least squares method (LSM) to determine polynomial coefficients, is instrumental in defining fitting accuracy. Notably, Formula (6) is invariably selected.

The following example will describe how the process of adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition works. Suppose an image

is regarded as a two-dimensional function over a rectangular domain:

=

,

denotes grayscale value of pixle of the sub-region,

∈

, the

and

represents the coordinates corresponding to pixel grayscale values. According to the self-similarity partition rule, during the initialization phase, image

will be divided into four sub-regions, recorded as

,

,

and

. Then, for each sub-region, the current region is divided into four sub-regions based on the self-similarity rules, and this process is repeated until the current region’s MSE (mean square error) is lower than the preset control threshold.

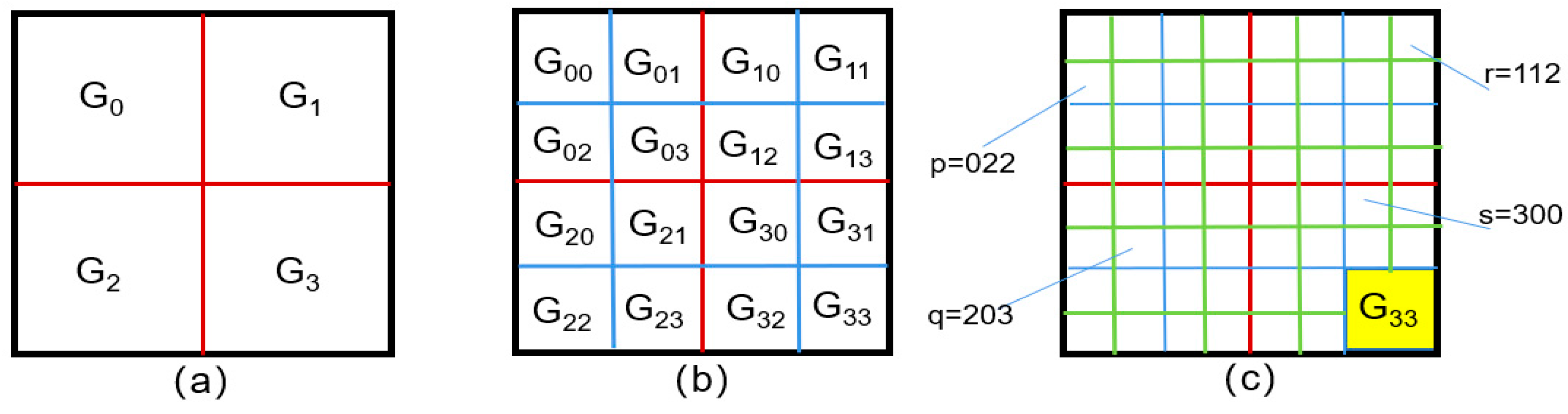

When a sub-region is designated as , the positive integer serves as its identifier within a quaternary numbering system, as depicted in Figure 6; this quaternary representation encodes the hierarchical position and structural relationship of the sub-region within the self-similar partition process.

Similarly, the sub-regions obtained by non-uniform rectangular partition, according to the principle of the quadtree, assign numbers

.

So that the position and size of the required sub-regions can be quickly found based on the numbers, facilitating the least squares method for approximation calculations and image reconstruction operations. As shown in

Figure 6(c), the numbers p, q, r, and s are subdivided quadtree partition codes, such as r=112, which can be traced from

to its specific location. Finally,

Figure 7 shows an example of using the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition algorithm for image reconstruction.

3. Methodology and Algorithm Analysis

The fractal image compression algorithm invariably segments blocks uniformly during the encoding phase, yielding fixed-sized R-blocks and overlapping D-blocks. Notably, the dimensions of the segmentation block have profound implications for the algorithm’s encoding duration, reconstruction fidelity, and overall compression efficacy. Employing smaller block segmentation enhances reconstruction quality; however, it may negatively impact the compression ratio and prolong encoding time, potentially leading to redundancy and a loss of inherent structural image information. Conversely, more extensive block segmentation might compromise reconstruction quality, manifesting as noticeable “block effects” within the reconstructed images.

The adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition is characterized by its ability to adapt to various features across different image regions. By segmenting images into adaptable blocks of varying sizes and shapes, this method effectively captures nuanced changes, particularly in areas with complex textures or irregular structures, thereby markedly improving data compression efficiency. During the encoding phase, the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition approach directs the division of R-blocks and D-blocks, facilitating a more accurate alignment with diverse image content. This is especially apparent when handling feature vectors from R-blocks compared to D-blocks, utilizing distance metrics and least squares approximation. Such integration not only assists in identifying the most suitable D-block but also reduces redundancy, decreases encoding durations, and enhances the quality of the reconstructed images.

The amalgamation of fractal image compression and adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition showcases an impressive equilibrium between image compression and preserving visual fidelity during reconstruction. This method exhibits superior performance and presents broader practical applications.

3.1. Block Segmentation Method

Fractal image compression techniques predominantly employ a uniform segmentation approach, where the original image (N N) is divided into overlapping D-blocks of dimensions 2R 2R. These D-blocks comprise R-blocks of size R x R. The total count of D-blocks can be calculated using the formula: ((N-2R)/R + 1)((N-2R)/R + 1). Furthermore, when eight distinct isometric transformations are applied, they generate a composite pool of D-blocks Ω, containing 8 × ((N-2R)/R + 1) ((N-2R)/R + 1) blocks. This extensive D-block results in a considerable amount of time being spent on the best-matching computation.

We introduce and utilize the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition method to address the limitation above. This technique segments the original image into non-overlapping D-blocks and R-blocks of varying sizes based on the local texture within the image. Given the same reconstruction quality, the quantity of R-blocks and D-blocks produced using this method is significantly less than that in BFIC. Consequently, this results in a substantial reduction in encoding time and an improvement in the compression ratio. The adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition algorithm establishes a preset block size range. The image is segmented into non-overlapping D-blocks with

88, 1616, and 3232 dimensions. Concurrently, it is partitioned into R-blocks measuring 44, 88, and 1616.

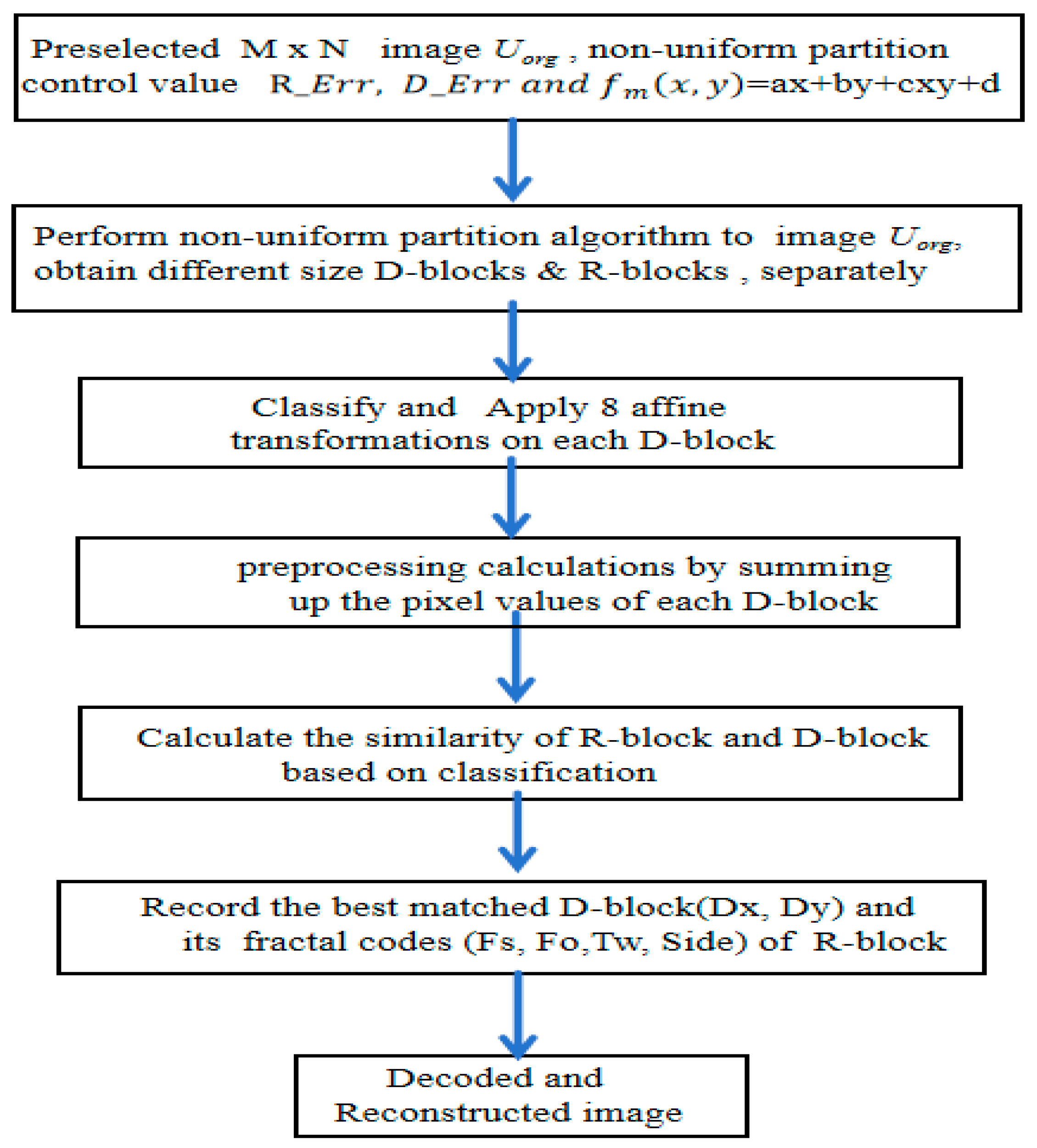

3.2. Process of FICANRP Scheme

The non-uniform partition method provides significant advantages in image segmentation and feature representation. The FICANRP initiates applying an adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition scheme to the original image. This results in the division of the image into variable-sized R-blocks and D-blocks. Then, eight isometric transformations and the precomputation of the sum are applied to each D-block. Finally, a localized optimal matching computation is conducted to generate the fractal codes. A comprehensive flowchart presenting the core algorithmic procedure has been provided for enhanced comprehension of our proposed methodology, as shown in

Figure 8. This diagram clearly outlines the sequential steps of fractal image compression using the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition approach.

3.3. Algorithm Detail

As can be seen from Formula (3), the traditional R-block matching algorithm suffers from significant computational inefficiency due to the repeated summation of D-blocks during similarity calculations, which is repeated four times. This issue arises because each D-block must undergo eight isometric transformations requiring independent similarity metric computations. The cumulative effect of these redundant operations leads to a substantial increase in computational complexity. This bottleneck is particularly pronounced in real-time applications like video compression, where latency directly impacts performance. The FICANRP algorithm addresses this by precomputing and reusing pixel sums, eliminating redundant operations while maintaining matching accuracy. Pixel value sums for all D-blocks are precalculated during initialization and stored in a temporary table indexed by each block’s spatial coordinates and dimensions. At runtime, similarity matching retrieves these precomputed sums in constant time, bypassing iterative recalculations.

In R-block similarity matching, the complexity calculation for the pixel sum of the D-block is presented as Formula (8). Suppose an

NN image is divided into

RR R-blocks and

2

R2

R D-blocks, respectively. The computational complexity of the D-block pixel sum of the traditional fractal image compression algorithm is as follows.

Using the precomputation method of D-block pixel summation, the complexity of the FICANRP algorithm is calculated as follows.

Accelerating similarity calculations by orders of magnitude. The algorithm drastically reduces computational overhead by eliminating redundant recalculations, making it particularly suitable for real-time systems such as video compression.

3.4. Algorithm Description

The FICANRP algorithm entails partitioning the image into non-uniform rectangular blocks in the segmentation and encoding phase. Subsequently, a contractive transformation function is constructed for each R-block, representing the image as a series of fractal codes. The following provides a detailed description of Algorithm 1:

|

Algorithm 1 FICANRP Encoding Algorithm |

Input: Size N x N Image

Output: Fractal codes (Fs, Fo, Tw, R_size, Dtx, Dty)

Algorithm process:

|

Preset the non-uniform partition control threshold R_Err, D_Err, and the range of R-block size and D-block size. Apply the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition algorithm on image, to obtain different sizes of R-blocks and D-blocks, respectively. /* k is the sub-region code */ Set k=1 Initial partition the into four small rectangular sub-regions , m∈ 0,1,2,3 Compute Vk, Sk, Bk with ENCODING ()

Function ENCODING()

Set the top left vertex of as Vm, the size of as Sk, the grey value of as Bk

For each pixel point (, ) in do Compute (, )←+++ with LSM /* is the gray value of the pixel in the sub-region / Compute e ←

Endfor If e < R_Err or Sk <=min R-block size / e < D_Err or Sk <= min D-block size Record Gm, Vm, Sm of R-block / D-block, as Bk, Vk, Sk, Classify Bk based on block size. Else Compute ENCODING (Gmr), r∈0,1,2,3 End if End Function Perform the average of 4-neighborhood pixel values for each D-block to obtain the compression transformation D'-block. Then, perform eight isometric transformations and various summations with block pixels to form the pool Ω of D-blocks. Preprocess calculations by summing up the pixel values of the D-block before each R-block similarity match. According to the partition order of R-block, calculate the similarity coefficient of R-block and D-block, the smaller the , the more similar it is, then record the fractal codes of each R-block where the is smallest. After all R-blocks are matched, the corresponding image reconstruction of fractal codes Fs, Fo, Tw, R_size, Dtx, and Dty will be obtained. |

In the decoding and reconstruction phase, iterative techniques systematically deform, concatenate, and fuse subgraphs across various scales, adhering to the non-uniform distribution pattern. This ensures image reconstruction with high fidelity and minimal redundancy. The primary steps in this phase are outlined in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2 FICANRP Decoding Algorithm |

Input: Fractal codes (Fs, Fo, Tw, R_size, Dtx, Dty)

Output: Decoding reconstruction Image

Algorithm process:

|

Preset the maximum iteration number N, read the fractal codes information, and extract data from fractal encoding files, including the IFS parameter set (Fs, Fo, Tw, R_size, Dtx, Dty) of each R-block. Initialize decoding space and create two buffers the same size as the original image: an R-region buffer and a D-region buffer. Initialize an arbitrary image matrix I_New, the same size as the original, to reconstruct the decoded image.

For n=1:N /* n represents the iteration number /

For Nr=1: Tprn /* Tprn represents the number of R-block/

Dx = Dtx(Nr)

Dy = Dty (Nr)

/* For each R-block R(Nr), locate the best match D-block D(Nr)

/ D(Nr)= I_New(Dx+2R_size: Dy+ 2R_size)

/* Apply spatial compression Ts and isometric transformation Tw to D(Nr) /

Temp(Nr)= Tw (Ts(D(Nr)))

I_New(Nr)= Fs(Nr)Temp(Nr) + Fo

(Nr)Nr= Nr+1

End for

End for

- 4.

Update the decoding area, copy and paste the content of the R-region image generated by the current iteration into the D-region, thereby updating the content of the entire decoded image. - 5.

Check if the number of iterations N has reached the preset maximum n. If so, end the iteration process; If not, return to step (2) to continue with the next iteration. Generally, the number of iterations is 8-10 times, and the reconstruction quality of the image will reach its optimal level.

|

The integration of fractal image compression and adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition allows for flexible adaptation to the diverse characteristics of different image regions, enhancing the encoding efficiency and maintaining a certain level of quality in the reconstructed images.

4. Simulation Experiments and Results

Our study primarily focuses on assessing the efficiency of image compression and reconstruction using an experimental simulation. The comparison is between the Basic Fractal Image Compression (BFIC) and Quadtree Fractal Image Compression (QFIC) schemes. Furthermore, we have conducted an exhaustive comparative analysis using the methodology proposed in this paper.

4.1. Experimental Conditions and Key Parameters

All methods are implemented in the MATLAB R2016a environment, with the hardware platform of Intel i5-9500 CPU @ 3.0 GHz and a computer operation system with Windows 10. The experiments will select Zelda, Peppers, Plane, Lena, and Cameraman as the standard 8-bit grayscale test images with the size of 512 × 512 for experimentation.

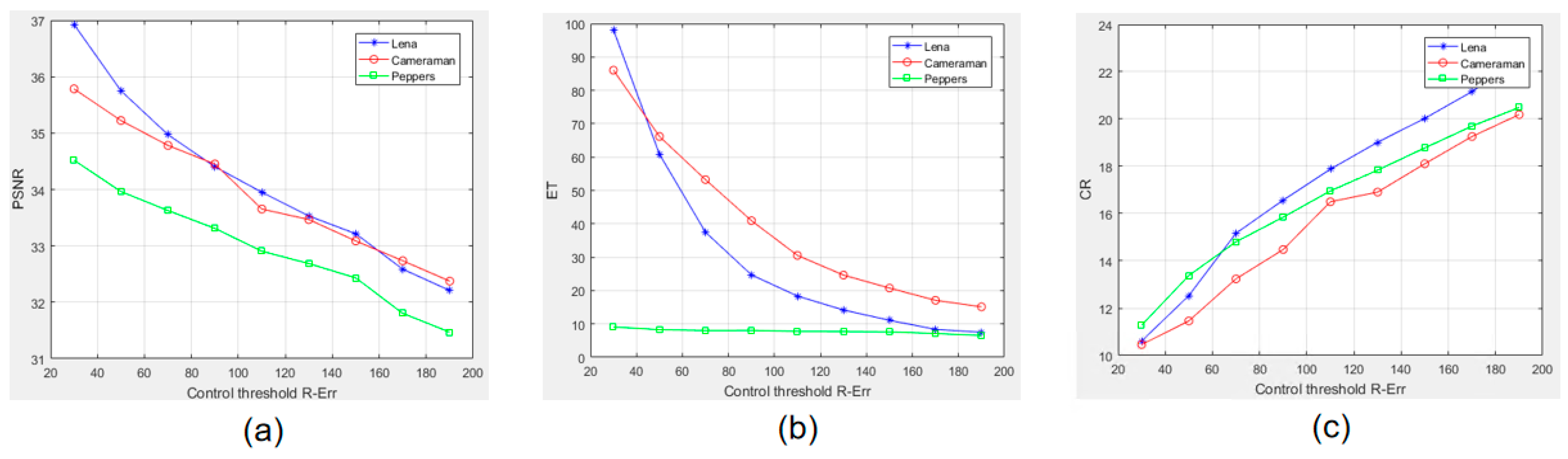

The simulation experiment below is designed for data analysis in fractal image compression, employing an adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition. The critical parameter for the partition control threshold, denoted as R_Err/ D_Err, plays a significant role in determining the image segmentation of R-blocks and D-blocks. This includes specifications such as their size and quantity. Furthermore, it influences experimental performance indicators, among which are the Peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), Encoding Time (ET), and Compression Ratio (CR). As shown in

Figure 9, the partition control threshold R_Err decreases, and the image is segmented into more R-blocks, enhancing the reconstruction quality. However, this also means that more parameters are needed for reconstruction, reducing the compression ratio and prolonging the encoding time. Therefore, setting the experimental parameter for the partition control threshold R_Err significantly influences the outcomes.

In fractal image compression based on the adaptive non-uniform rectangular partition (FICANRP) framework, calculating R_Err is critical in determining the quality of image compression and reconstruction. To efficiently compute R_Err in scenarios where computational resources are limited or standard deviation values are difficult to obtain, we propose a simplified model that leverages the image's mean intensity (Me) and mean gradient (Mg). This model significantly reduces computational complexity while maintaining high accuracy in R_Err estimation.

Through experimental data analysis, we observed a strong linear relationship between R_Err and mean intensity and mean gradient. Therefore, a linear regression model can effectively describe this relationship. The R_Err can be expressed as a linear combination of mean intensity (

Me) and mean gradient (

Mg).

4.2. Evaluation Standard

In fractal image compression, the compression ratio (CR) serves as a crucial metric for evaluating the efficacy of the compression method. This ratio provides a quantitative measure of the reduction in data size achieved through the encoding process using fractal properties. The formula for the compression ratio is CR = U/C, where U represents the size of the original, uncompressed image data, and C represents the size of the compressed image data. This metric is instrumental in assessing the performance and efficiency of fractal image compression.

The fractal codes

Fs, Fo, and

Tw used in fractal image compression are typically quantized into 5-bit, 7-bit, and 3-bit formats, respectively. In our proposed method, the fractal codes for an N

N image—

Fs, Fo, Tw,

R_size, Dtx, and

Dty are quantified as 5-bit, 7-bit, 3-bit, 2-bit, p-bit, and q-bit, respectively. Here, p and q are dynamically quantized based on the partition number of the D-block. Consequently, the compression ratio (CR) of the image is defined as follows:

Wherein Num_R represents the number of R-blocks, while R_size characterizes the style of image segmentation into varying R-block sizes. It should be noted that the count of R-blocks and D-blocks is not fixed. Instead, the number of image blocks procured will be dynamically adjusted based on the texture of the image and the partition control thresholds.

To evaluate the performance of our method, we introduce some basic metrics, such as the total encoding time and the PSNR of the reconstructed image. In our method, the PSNR is defined as:

Where N denotes the number of pixels, denotes the grayscale value of pixel within the original image, and denotes the grayscale value of pixel within the reconstructed image.

4.3. Algorithm Complexity

In the BFIC algorithm, the computational overhead primarily originates from exhaustive comparisons between fixed-size R-blocks and a large D-block pool. The complexity calculation for the pixel sum of the D-block is as follows.

The computational complexity of quadtree fractal image compression (QFIC) primarily stems from its hierarchical block-matching mechanism between R-blocks and D-blocks. This complexity is determined by three interdependent factors. First, the hierarchical block dimensions, where operations scale quadratically with the size of R-blocks and D-blocks. Second, the reconstruction fidelity constraint imposed by R-blocks' mean square error (R_mse). Finally, the quadtree segmentation depth governs the multi-resolution decomposition granularity. Suppose an image is divided into three layers, and the number of 16

16 R-blocks is

, the number of 8

8 R-blocks is

, and the number of 4

4 R-blocks is

. The corresponding number of 32

32 D-blocks is

, 16

16 D-blocks is

, 8

8 D-blocks is

. The QFIC algorithm complexity for pixel sum of the D-block is shown in formula (14).

Since the FICAURP uses an adaptive algorithm to segment R-blocks, the number of R-blocks will change dynamically according to the presetting of the non-uniform partition coefficient. Suppose the FICAURP segments the original image into

16

16 R-blocks,

8

8 R-blocks, and

4

4 R-blocks. The corresponding number of 32

32 D-blocks is

, The number of 16

16 D-blocks is

, The number of 8

8 D-blocks is

. Using the precomputing and reusing algorithm to sum the D-block pixel value, its computational complexity is:

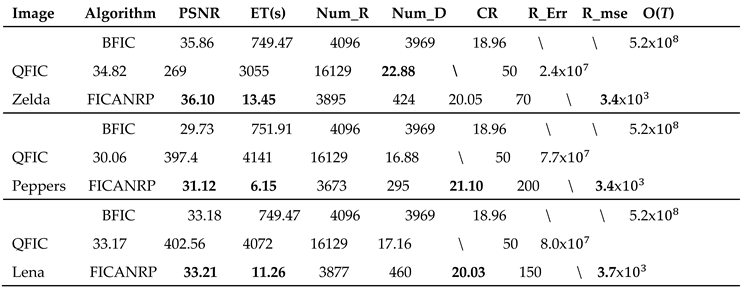

4.4. Analysis and Results of Experimental

In our comparative analysis condition, the BFIC approach partitions the original image into 4096 non-overlapping R-blocks using a fixed 8×8 grid size. Simultaneously, an overlapping segmentation method that uses a 16×16 grid with an eight-unit step size is implemented, giving rise to 3969 D-blocks. A comprehensive search and matching process is conducted on each R-block within the D-blocks' post-affine transformation. The

Fs, Fo, Tw,

Dtx, and

Dty fractal codes are quantized using 5-bit, 7-bit, 3-bit, 6-bit, and 6-bit resolutions, respectively. The resulting image compression ratio(CR) is:

The QFIC [

11] results are predicated on the following conditions: the minimum R-block size is preset at 4x4, and the reconstructed R-block's mean square error (R_mse) is set to 50. Initially, the original image is segmented into non-overlapping 16x16 R-blocks and overlapping 32x32 D-blocks. Subsequently, a classification scheme is applied to all D-blocks, dividing them into three major categories and 24 subcategories to minimize the number of domains relative to a range. The next step involves calculating the best match between each R-block and D-block, selecting the one with the slightest error, and comparing it with R_mse. If the R_mse exceeds 50 and the R-block size is more significant than 4x4, the R-block is segmented into four smaller blocks until the R_mse is less than 50 or the R-block size is less than or equal to 4x4. The fractal codes of

Fs, Fo, Tw, Ql, Dtx, and

Dty are quantized as 5-bit, 7-bit, 3-bit, 1-bit, 6-bit, and 6-bit, respectively. Here, the Ql represents the depth of the quadtree segmentation.

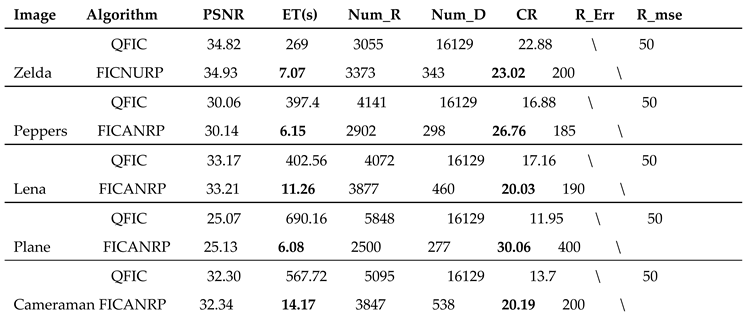

In

Table 1, PSNR stands for peak signal-to-noise ratio; ET stands for encoding time, its measurement unit is seconds, and CR stands for compression ratio. Num_R denotes the total number of R-blocks, Num_D denotes the total number of D-blocks, R_mse denotes the mean squared error of the R-block reconstructed, R_Err denotes the partition control threshold, and O(

T) represents the algorithm complexity.

As demonstrated in

Table 1, the FICANRP scheme significantly improves the fractal image compression coding efficiency and reconstruction quality compared to BFIC and QFIC, which simultaneously preserves critical image details while requiring fewer R-blocks for reconstruction. The FICANRP shows superior performance metrics with average improvements of 1.425 in compression ratio (CR), 1.51dB in peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), and an encoding acceleration factor of 67.44× relative to the BFIC baseline. Particularly noteworthy is the performance enhancement observed in processing the Peppers test image, where the algorithm achieves a remarkable 122× encoding speed improvement accompanied by a 1.39dB PSNR gain and a CR of 21.10 - representing a 2.14-fold enhancement over BFIC's compression capability. These substantial improvements stem from the optimized partitioning mechanism that dynamically adjusts block dimensions based on local texture complexity, effectively balancing computational load with reconstruction fidelity.

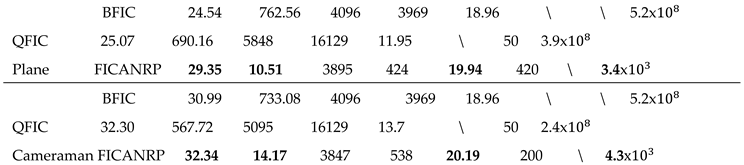

To compare the performance metrics of the QFIC and FICANRP algorithms, we evaluated encoding time and compression ratio under identical PSNR conditions. The results of these experiments, as presented in

Table 2, indicate that our proposed scheme outperforms QFIC in terms of encoding time and compression ratio, particularly within the image Plane. Notably, our method achieved an encoding time that was 114 times faster and a compression ratio that was 19 times higher.

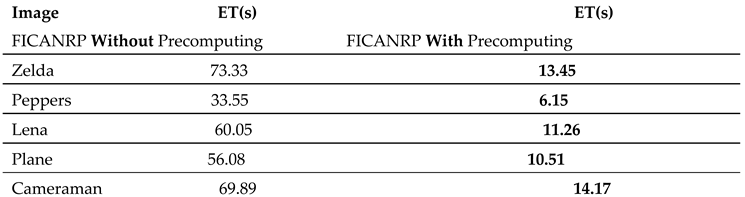

Additionally, the proposed precomputing algorithm has demonstrated remarkable efficiency improvements in the block similarity matching process of FICANRP, especially in terms of reducing the computational complexity and encoding time. As shown in

Table 3, the encoding time of the proposed algorithm with D-block sum precomputing has been significantly shortened and accelerated by 5 times compared to without precomputing. The substantial reduction in encoding time can be attributed to the core strategy of precomputing the algorithm. By precomputing various sums of pixel values for each D-block that has undergone eight isometric transformations and storing these pre-computed results in a temporary table constructed according to the block coordinates and sizes, we have effectively reduced the memory access latency during the matching process. Experiments show that the matching process of precalculation and optimization will not lead to a reduction in accuracy.

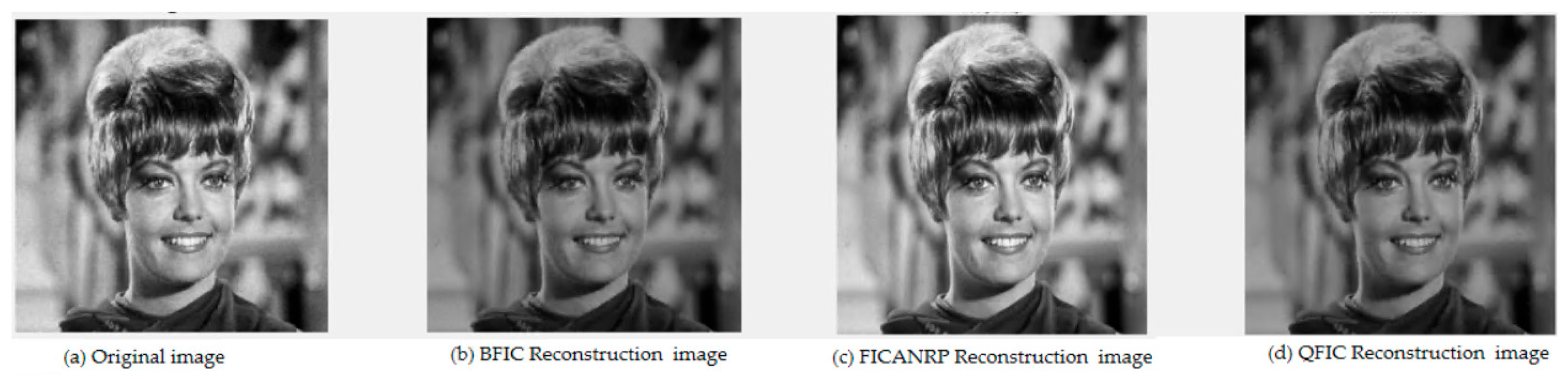

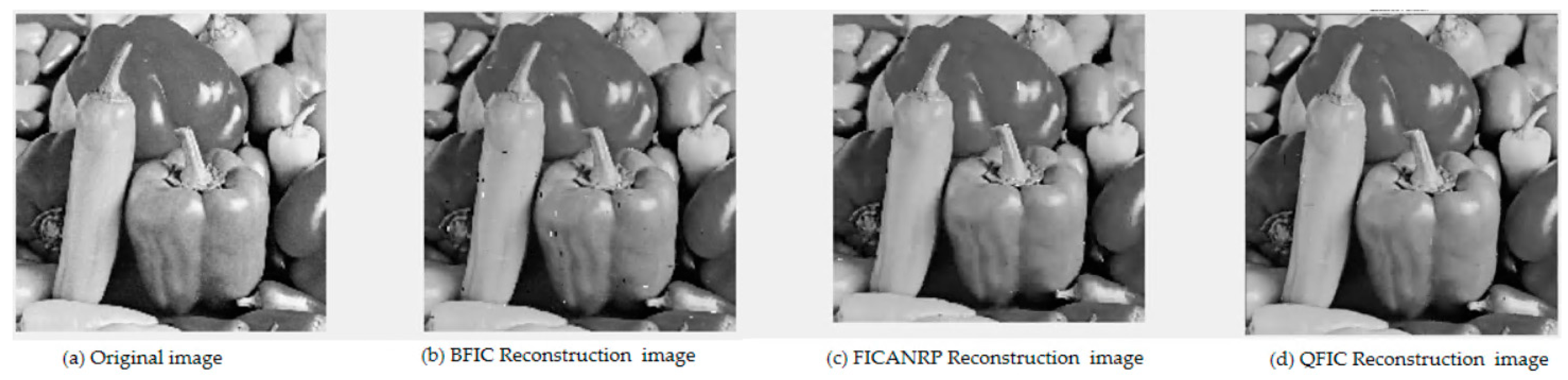

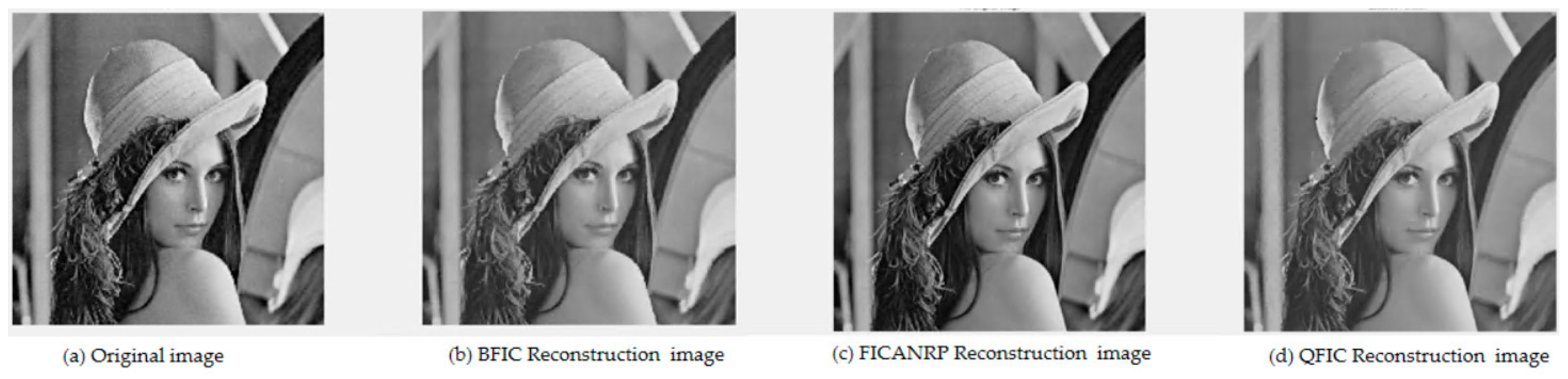

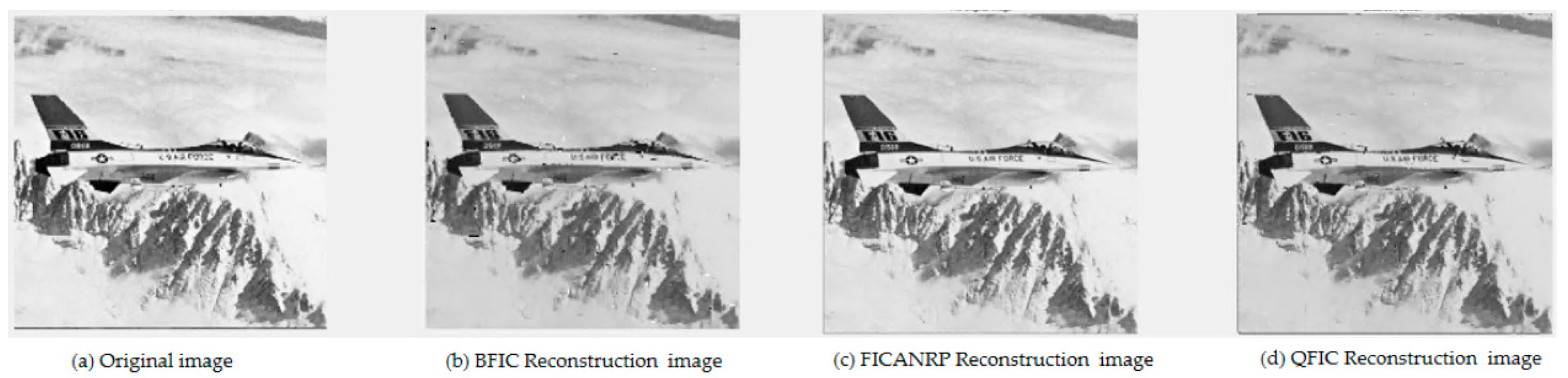

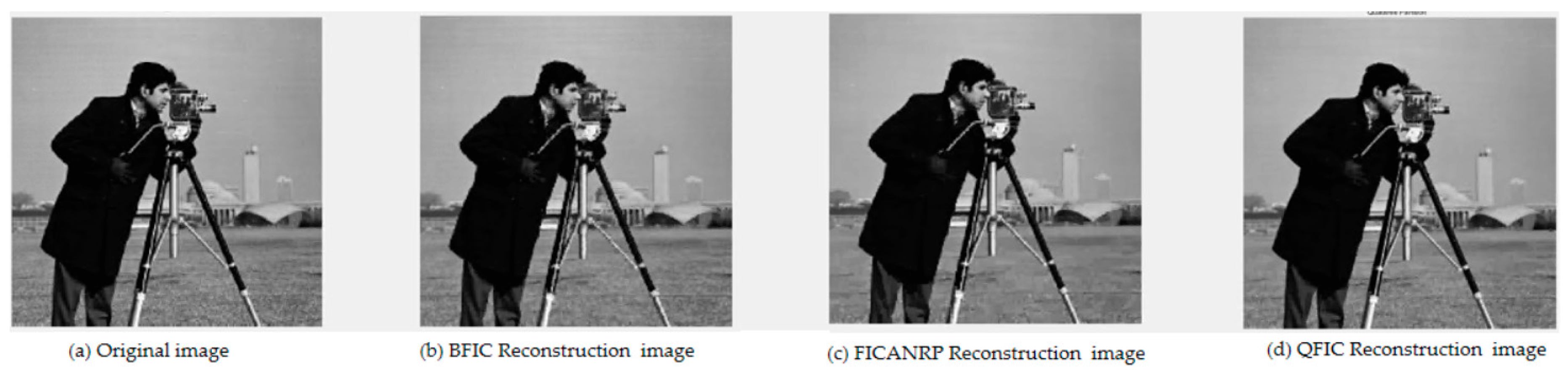

In another way, through subjective visual analysis, the performance of BFIC, QFIC, and our proposed method can be evaluated by decoding reconstruction images.

Figure 11 and

Figure 13 illustrate that the reconstructed images using the BFIC method contain numerous white spots, while those reconstructed using the QFIC method appear noticeably darker.

Figure 10.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Zelda image reconstruction results.

Figure 10.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Zelda image reconstruction results.

Figure 11.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Peppers image reconstruction results.

Figure 11.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Peppers image reconstruction results.

Figure 12.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Lena image reconstruction results.

Figure 12.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Lena image reconstruction results.

Figure 13.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Plane image reconstruction results.

Figure 13.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Plane image reconstruction results.

Figure 14.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Cameraman image reconstruction results.

Figure 14.

Comparison of different algorithms in the Cameraman image reconstruction results.

Upon comparing and analyzing the BFIC and QFIC methodologies, it is evident that our proposed FICANRP method provides superior compression performance. This methodology achieves a heightened compression ratio and maintains image reconstruction quality. Meanwhile, it effectively mitigates the space and time expenses associated with storage and transmission.

5. Conclusions and Future

This study presents the FICANRP scheme as a solution to the high computational complexity and long encoding times associated with traditional BFIC and QFIC methods. This is achieved by segmenting images into variable-sized R-blocks based on adaptive non-uniform rectangle partition guided by local textures and features, which requires fewer R-blocks for image reconstruction under the same PSNR. Furthermore, the FICANRP method uses non-overlapping block segmentation to shrink the D-block pool. It employs a novel block similarity matching algorithm, significantly reducing the algorithm complexity and encoding time. Experimental results indicate that the proposed approach effectively balances computational efficiency, reconstruction quality, and compression performance, making it an ideal choice for applications necessitating rapid encoding and efficient storage. Moreover, the proposed scheme can be adapted to various application scenarios by fine-tuning parameters to meet specific requirements of the reconstructed image, such as Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Compression Ratio (CR), or Encoding Time (ET). Future research could potentially enhance this method by optimizing segmentation algorithms, integrating deep learning techniques designed for rapid similarity-matching of image block features, or by adapting it to the fields of remote sensing and medical imaging after appropriate modifications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L., and K.U.; methodology, M.L., and K.U.; software, M.L.; validation, M.L.; resources, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L.; visualization, M.L.; supervision, K.U.; project administration, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Our research did not receive any external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed. Data sharing does not apply to this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to the editor and reviewers for their careful review and suggestions, which have greatly enhanced the quality and rigor of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M. F. Barnsley, Fractals everywhere, 2. ed., 3. [print.]. San Diego: Morgan Kaufmann, 20.

- E. Jacquin, “Image coding based on a fractal theory of iterated contractive image transformations,” IEEE Trans. Image Process., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 18–30, Jan. 1992. [CrossRef]

- “Iterated function systems and the global construction of fractals,” Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Math. Phys. Sci., vol. 399, no. 1817, pp. 243–275, Jun. 1985. [CrossRef]

- Chong Sze Tong and Man Wong, “Adaptive approximate nearest neighbor search for fractal image compression,” IEEE Trans. Image Process., vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 605–615, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- T. Tan and H. Yan, “The fractal neighbor distance measure,” Pattern Recognit., 2002.

- X.-Y. Wang, Y.-X. Wang, and J.-J. Yun, “An improved fast fractal image compression using spatial texture correlation,” Chin. Phys. B, vol. 20, no. 10, p. 104202, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. Jaferzadeh, K. Kiani, and S. Mozaffari, “Acceleration of fractal image compression using fuzzy clustering discrete-cosine-transform-based metric,” Image Process. IET, vol. 6, pp. 1024–1030, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, “A Novel Fractal Image Compression Scheme With Block Classification and Sorting Based on Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient,” IEEE Trans. IMAGE Process., vol. 22, no. 9, 2013.

- K. Jaferzadeh, I. Moon, and S. Gholami, “Enhancing fractal image compression speed using local features for reducing search space,” Pattern Anal. Appl., vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 1119–1128, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Cao, A. Zhang, and L. Shi, “Orthogonal sparse fractal coding algorithm based on image texture feature,” IET Image Process., vol. 13, no. 11, pp. 1872–1879, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fisher, Fractal Image Compression: Theory and Application. Springer Science & Business Media, 1995.

- W. Xing-Yuan and G. Xing, “An effective fractal image compression algorithm based on plane fitting,” vol. 21, no. 9, 2012.

- W. Li, Q. Pan, J. Lu, and S. Li, “Research on Image Fractal Compression Coding Algorithm Based on Gene Expression Programming”.

- S. Smriti, A. Laxmi, and B. M. Hima, “Image Compression using PSO-ALO Hybrid Metaheuristic Technique,” Int. J. Perform. Eng., vol. 17, no. 12, p. 998, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tang, S. Yan, and C. Xu, “Adaptive super-resolution image reconstruction based on fractal theory,” Displays, vol. 80, p. 102544, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L.-F. Li, Y. Hua, Y.-H. Liu, and F.-H. Huang, “Study on fast fractal image compression algorithm based on centroid radius,” Syst. Sci. Control Eng., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 2269183, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Snyder, “Fractals and the Collage Theorem”.

- A. Oppenheim, D. Johnson, and K. Steiglitz, “Computation of spectra with unequal resolution using the fast Fourier transform,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 299–301, Feb. 1971. [CrossRef]

- S. Bagchi and S. K. Mitra, “The nonuniform discrete Fourier transform and its applications in filter design. I. 1-D,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Analog Digit. Signal Process., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 422–433, Jun. 1996. [CrossRef]

- S. Bagchi and S. K. Mitra, “The nonuniform discrete Fourier transform and its applications in filter design. II. 2-D,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Analog Digit. Signal Process., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 434–444, Jun. 1996. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Donoho, “Wedgelets: nearly minimax estimation of edges,” Ann. Stat., vol. 27, no. 3, Jun. 1999. [CrossRef]

- “The Nonuniform V-Transform Theory and Applications.pdf.”.

- U. K. Tak, Z. Tang, and D. Qi, “A non-uniform rectangular partition coding of digital image and its application,” in 2009 International Conference on Information and Automation, Jun. 2009, pp. 995–999. [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan and Z. Cai, “An Adaptive Triangular Partition Algorithm for Digital Images,” IEEE Trans. Multimed., vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 1372–1383, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Z. Cai, and G. Xiong, “A New Image Compression Algorithm Based on Non-Uniform Partition and U-System,” IEEE Trans. Multimed., vol. 23, pp. 1069–1082, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Benouaz and O. Arino, “Least square approximation of a nonlinear ordinary differential equation,” Comput. Math. Appl., vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 69–84, Apr. 1996. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, K. U, and H. Luo, “Adaptive non-uniform partition algorithm based on linear canonical transform,” Chaos Solitons Fractals, vol. 163, p. 112561, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, K. U, and H. Luo, “Image representation method based on Gaussian function and non-uniform partition,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 839–861, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. U., N. Ji, D. Qi, and Z. Tang, “An Adaptive Quantization Technique for JPEG Based on Non-uniform Rectangular Partition,” in Future Wireless Networks and Information Systems, vol. 143, Y. Zhang, Ed., in Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol. 143. , Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 179–187. [CrossRef]

- R. Song, Y. Li, Q. Zhang, and Z. Zhao, “Image denoising method based on non-uniform partition and wavelet transform,” in 2010 3rd International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, Oct. 2010, pp. 703–706. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu and U. Kintak, “A novel multi-focus image-fusion scheme based on non-uniform rectangular partition,” in 2017 International Conference on Wavelet Analysis and Pattern Recognition (ICWAPR), Jul. 2017, pp. 53–58. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, K. U, and H. Luo, “An image super-resolution method based on polynomial exponential function and non-uniform rectangular partition,” J. Supercomput., vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 677–701, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Hu and K. Tak U., “A Novel Video Steganography Based on Non-uniform Rectangular Partition,” in 2011 14th IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, Aug. 2011, pp. 57–61. [CrossRef]

- K. U, S. Hu, D. Qi, and Z. Tang, “A robust image watermarking algorithm based on non-uniform rectangular partition and DWT,” in 2009 2nd International Conference on Power Electronics and Intelligent Transportation System (PEITS), Dec. 2009, pp. 25–28. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).