Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Synopsis of Diabetes Mellitus

2.2. Existing Comparative Analysis of ML, DL, and Ensemble Models for DM Prediction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Techniques for Datasets Imbalance

3.1.1. Oversampling Techniques

-

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Techniques (SMOTE): By creating artificial samples for the minority class, SMOTE is a synthetic minority oversampling technique that balances class distribution [49,50]. Rather than simply duplicating existing minority class samples, SMOTE interpolates between them to create new instances, selecting k nearest neighbours for each minority class observation and creating synthetic points along the line segments connecting them, with a random interpolation factor between 0 and 1 to ensure diversity [51]. SMOTE is represented as:where = ith minority instances, n = No. of features (dimensions) and N = number of minority class instances.The k nearest neighbours of based on a distance metric (usually Euclidean distance) denoting the set of these neighbours as:where = k-nearest neighbours of . Finally, it creates a new synthetic sample by randomly choosing a neighbour and then generate the through interpolation between andwhere is the random scalar randomly drawn from the uniform distribution between 0 and 1 i.e. U(0,1). These steps continue until the desired amount of synthetic minority samples has been created.

- SMOTE and Edited Nearest Neighbours (SMOTE-ENN): To improve the data quality, this method combines SMOTE with Edited Nearest Neighbours (ENN). To balance the dataset, SMOTE first creates artificial minority samples. Then, the noisy cases, synthetic and original, where most of their nearest neighbours are in the opposite class, are eliminated using ENN [50,52]. By removing incorrectly categorized or unclear samples, this two-step procedure guarantees more precise decision limits and improves generalization in classification tasks.

- Random Oversampling: To rectify class imbalance, minority class samples are replicated at random until the required balance is reached. This approach, in contrast to SMOTE, replicates current observations without producing artificial data. Although efficient and straightforward, it risks the danger of overfitting if the same data are used too frequently. Subsets of minority cases can be resampled using replacement to lower this risk and guarantee variety in the enhanced dataset [53].

-

Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN): As an adaptive extension of SMOTE, ADASYN focuses on complex minority class samples. Minority occurrences that are close to the decision border or encircled by majority class samples are given greater weights by ADASYN [54]. For these "hard-to-learn" situations, more synthetic data is produced, directing the classifier's focus to unclear areas [51,54]. By decreasing bias and fine-tuning the decision boundary in unbalanced datasets, this adaptability increases model resilience. Mathematically, it is represented in this regard:andnearest neighbours computation for majority class for each minority samples is given as:where if , is easy to classify but if , is difficult to classify and hence requires more synthetic samples. Normalized density distribution for each minority sample (difficult scores)where the distribution represents the importance of each minority sample in oversampling. The method then computes how many synthetics to generate from each minority sample as:where can be rounded to the nearest integer. Therefore, for each minority sample , it then generates synthetic samples by randomly selecting a minority-class neighbour from the K-nearest neighbours of belonging to minority class and then generate the synthetic samplesThis process continues times for each minority sample

2.1.1. Undersampling Techniques

- Clustering Centroids: Swapping out clusters for corresponding centroids lowers the number of majority class samples. Groups of majority occurrences are compressed into a single representative point using K-means clustering [55].

- Random Undersampling with Tomek Links: Firstly, random undersampling is used to lower the size of the majority class. Next, it eliminates Tomek Links, which are pairings of instances of the opposite class nearest to each other. It then lowers noise and clarifies the decision boundary by eliminating the majority of samples from these pairings. This hybrid strategy compromises increased classifier performance and efficiency [55].

- NearMiss–3: This method chooses samples from the majority class according to how far away they are from minority cases. It finds each minority observation's M nearest neighbours in its first phase. Next, it eliminates duplicate or overlapping locations by keeping most samples with the most significant average distance to these neighbours. This method improves class separability by prioritising the majority instances farthest from the minority class [55,57].

- One-Sided Selection (OSS): This method prunes superfluous majority samples by combining Condensed Nearest Neighbour (CNN) and Tomek Links elimination. First, questionable situations are removed from Tomek Links. CNN then keeps a small subset of majority instances that faithfully capture the initial distribution. By ensuring a small but representative majority class, this two-step procedure improves the accuracy and efficiency of the model [55].

- Neighbourhood Cleaning: This method improves undersampling by eliminating the noisy majority of samples. It detects and removes misclassified majority cases using a k-NN classifier. While maintaining essential data structures, this focused cleaning lessens class overlap. For best effects, it is frequently used with other undersampling techniques [55].

3.2. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques employed

3.2.1. Machine Learning Models

- Logistic Regression (LR): LR is an ML and statistics algorithm for binary classification tasks. The sigmoid (logistic) function, which converts real-valued inputs to a range between 0 and 1, describes the connection between input data and the likelihood of a class label. Using methods such as Gradient Descent, the log-likelihood function is optimized to train the model. It assumes that the log odds of the dependent and independent variables have a linear relationship [58,59].

- Naïve Bayes (NB): Based on the Bayes theorem, the Naïve Bayes algorithm is a probabilistic classification algorithm that assumes all features are conditionally independent, given the class label. Despite this high independence assumption, It works effectively in various real-world applications, including spam filtering and text categorization. It uses observed data and past knowledge to determine a class's posterior probability [59,60,61].

- Decision Trees (DT): This supervised learning system iteratively divides data into subsets according to feature requirements to generate predictions. It is composed of leaves (final predictions), branches (outcomes), and nodes (decision points). Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression and Gini Index or Entropy (Information Gain) for classification serve as the foundation for the splitting criterion. To minimize impurity until a stopping condition is satisfied, the tree develops by choosing the best feature at each stage [61].

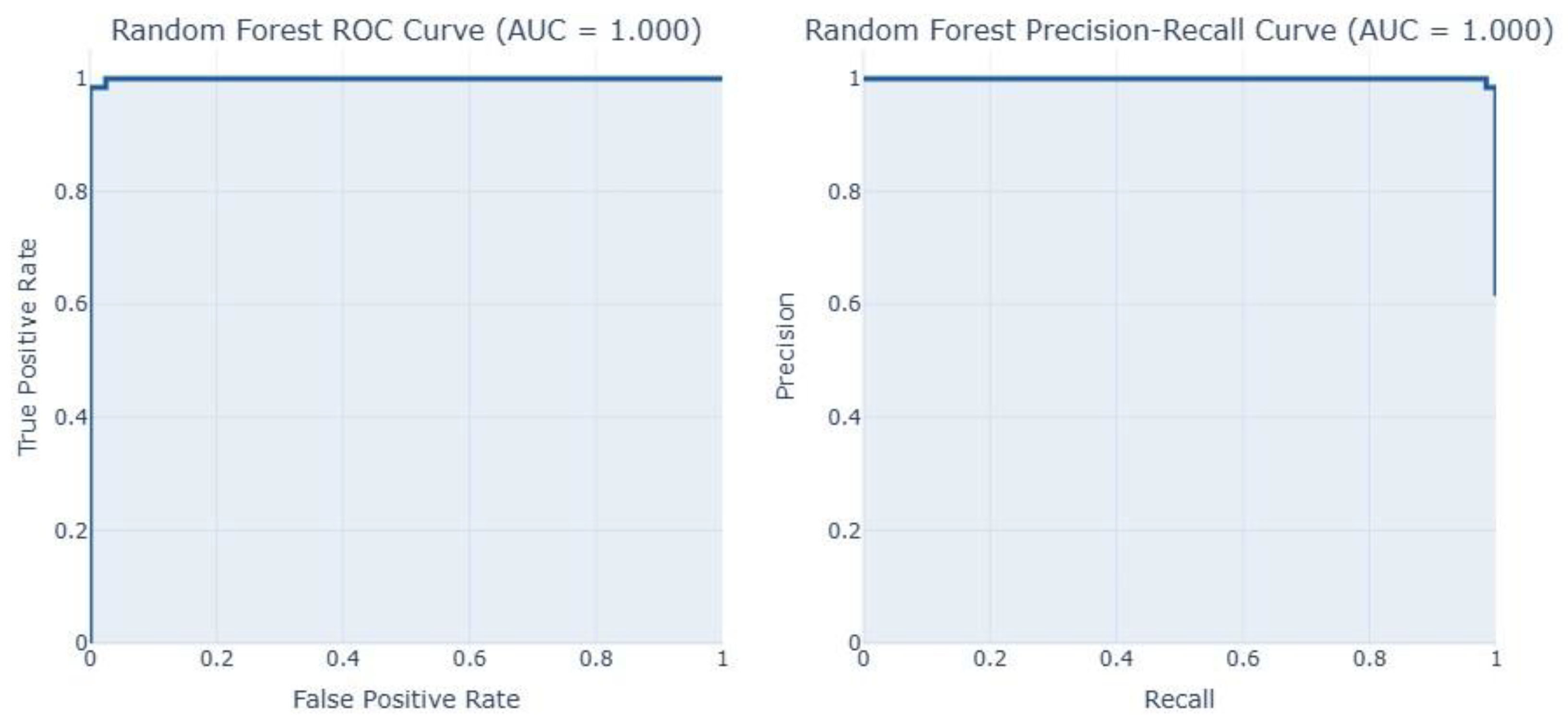

- Random Forest (RF): This ensemble learning system builds many DTs during training and aggregates their results to provide more accurate predictions. To minimize overfitting and enhance generalization, each tree is trained on a randomly sampled fraction of the data (bagging) and employs a randomly chosen subset of features at each split. Either majority voting (classification) or average (regression) over all trees determines the final prediction. RF delivers feature relevance ratings, is noise-resistant, and can handle numerical and categorical data [10,16,59,62].

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): This supervised learning technique determines the best hyperplane to divide data points by maximising the gap between classes. The most important data points defining the decision boundary are support vectors, which are what it depends on. SVM uses kernel functions (such as linear, polynomial, and Radial Basis Functions – RBF) to translate data that is not linearly separable into a higher-dimensional space where separation is possible. It works well with high-dimensional [10,16,59,63].

- K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN): Data points are categorized using this instance-based, non-parametric learning approach according to the majority class of their k-closest neighbours. The Euclidean, Manhattan, or Minkowski distances are commonly used to quantify the separation between two points. Because KNN does not require explicit training, it is computationally cheap while training but costly when inferring because it needs to store and search the full dataset. The amount of k impacts model performance; small values may result in overfitting, while high values may result in underfitting [16,64,65,66].

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): XGBoost is a sophisticated gradient boosting method that has been fine-tuned for accuracy and efficiency. It approximates the loss function using a second-order Taylor expansion to provide more accurate updates during training. Through cache-aware access patterns, histogram-based split discovery, and parallelized execution, the approach enhances computing performance. L1 (alpha) and L2 (lambda) penalties are two regularization strategies that assist in reducing overfitting and managing model complexity. To improve generalization, XGBoost further uses column subsampling and shrinkage (learning rate tuning) [10,16,62,63].

- Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost): An ensemble learning method builds a robust classifier by combining several weak learners, usually decision stumps. Iteratively, it forces weaker learners to concentrate on more challenging examples by giving misclassified samples larger weights. All weak classifiers cast a weighted majority vote to determine the final prediction. AdaBoost dynamically modifies sample importance to enhance model performance and minimizes an exponential loss function [16,59].

3.2.2. Deep Learning Models

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): CNNs are DL models that manage grid-like data, including time series and pictures. It comprises fully connected layers that carry out classification or regression, pooling layers that lower dimensionality while preserving important information, and convolutional layers that use filters to identify spatial characteristics. CNNs extract features well because they use weight sharing and local connection. Activation functions like Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) introduce non-linearity, which improves learning. Achieving the best performance requires careful architectural design consideration, including the number of layers, filter sizes, and pooling algorithms [16,67,68].

- Deep Neural Networks (DNN): There are hidden layers between the input and output layers of this kind of ANN. The DNN model can learn intricate patterns because each layer comprises linked neurons with nonlinear activation functions. Backpropagation and optimization algorithms such as Adam or Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) are used for training. DNNs are very good at tasks like image recognition, NLP, and time-series forecasting because of their superiority in feature extraction and representation learning. Overfitting may be avoided, and generalization can be enhanced via regularization techniques like batch normalization and dropout [5,14,69]

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN): RNN is a kind of NN that uses hidden states to retain a memory of prior inputs to interpret sequential data. RNNs can capture temporal dependencies because, in contrast to feedforward networks, they exchange parameters across time steps. They are often employed in applications like NLP, time-series forecasting, and speech recognition. However, learning long-term dependencies is challenging for ordinary RNNs due to issues like disappearing and expanding gradients [16].

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): Long-term relationships in sequential data can be captured efficiently by this sophisticated RNN. The vanishing gradient issue is solved by adding the forget gate, input gate, and output gate, which control the information flow. Because of these gates, LSTMs may selectively keep or reject data, which makes them ideal for applications like time-series forecasting, language modelling, and speech recognition. Long-range dependencies may be learned by LSTMs without a substantial loss of information, in contrast to conventional RNNs. Gate activations and sequence durations must be tuned appropriately for best results [14,16,68].

- Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU): It is a sophisticated RNN that deals with the vanishing gradient issue and processes sequential input. Introducing gating techniques that control information flow enables the network to save essential historical data and eliminate extraneous details. GRUs are computationally easier and perform similarly to LSTMs since they feature update and reset gates. GRUs are frequently employed in machine translation, time-series forecasting, and speech recognition applications. They are effective at identifying long-term relationships in sequences because they can adaptively regulate memory retention [16].

3.2.3. Ensemble Models

3.3. Performance Metrics Tools

3.3.1. Hyperparameter Tuning

3.3.2. Evaluation Metrics

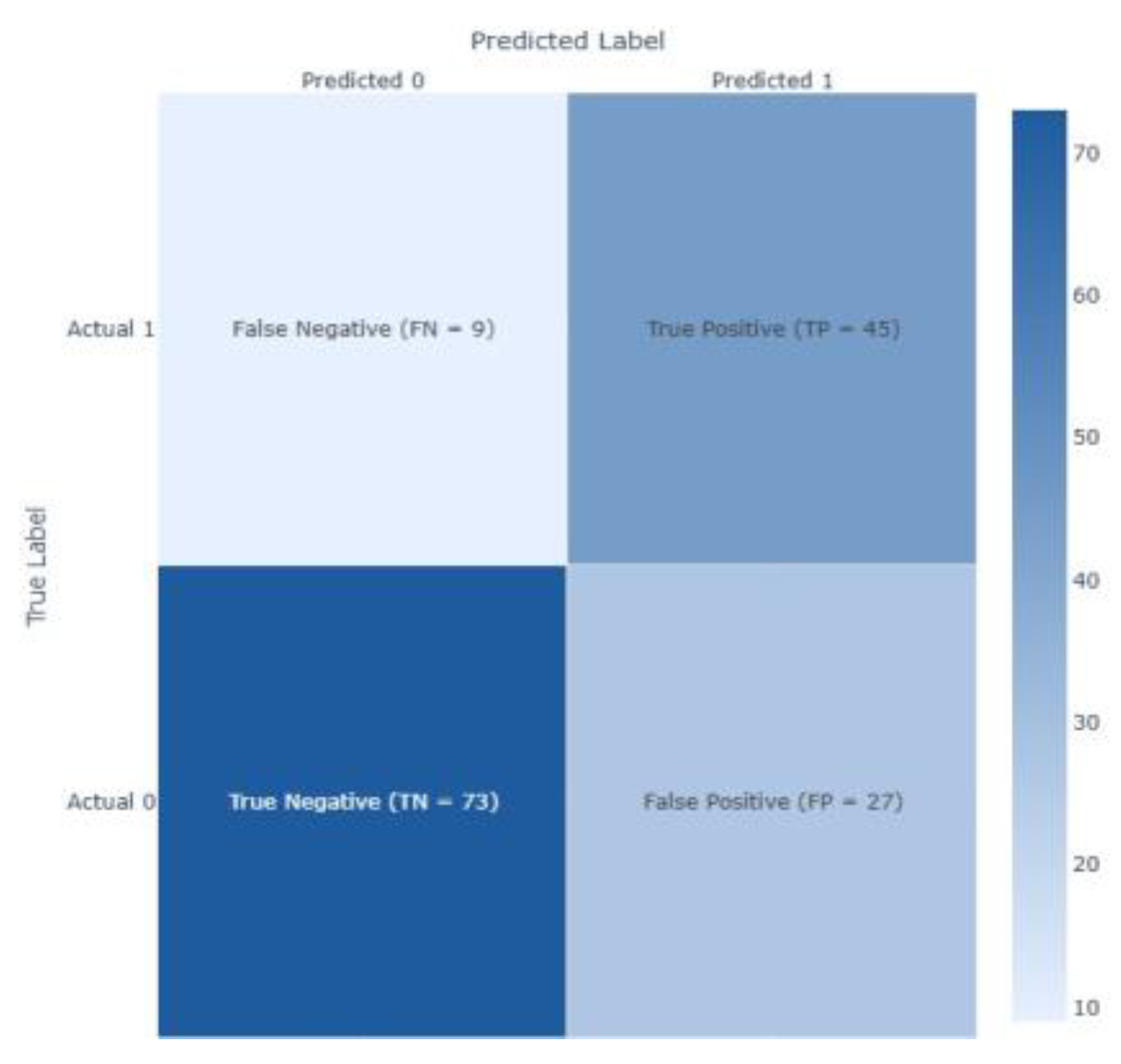

- Accuracy: calculates the ratio of true predictions (both positive and negative) to all forecasts produced to get the total percentage of accurate predictions. Although accuracy seems straightforward, it might be deceptive for unbalanced datasets since it does not differentiate between different kinds of mistakes.where TP = True Positive, TN = True Negative, FP = False Positive, and FN = False Negative.

- Precision: determines how reliable positive predictions are by calculating the percentage of TP among all positive forecasts. This measure is crucial when FP might result in significant expenses, such as unneeded medical procedures or fraudulent notifications.

- Recall (Sensitivity): calculates the percentage of TP that are successfully detected, which indicates how well the model detects positive cases. In applications like illness screening or security threat identification, where it is risky to overlook positive instances, high recall is crucial.

- F1-Score: It combines accuracy and recall using their harmonic mean to assess model performance fairly. This is our primary assessment statistic since it evenly weights FP and FN, effectively managing class imbalance.

- AUC-ROC: The model's capacity to differentiate between classes across all potential classification thresholds is assessed using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve. A perfect classifier obtains an AUC of 1, whereas 0.5 is obtained by random guessing.where represents the decision threshold

- Inference Time: This logs the time needed to produce predictions to assess the model's computational efficiency. Although it has no bearing on the statistical performance of the model, this parameter is essential for real-time applications and deployment in contexts with limited resources.

3.4. Datasets

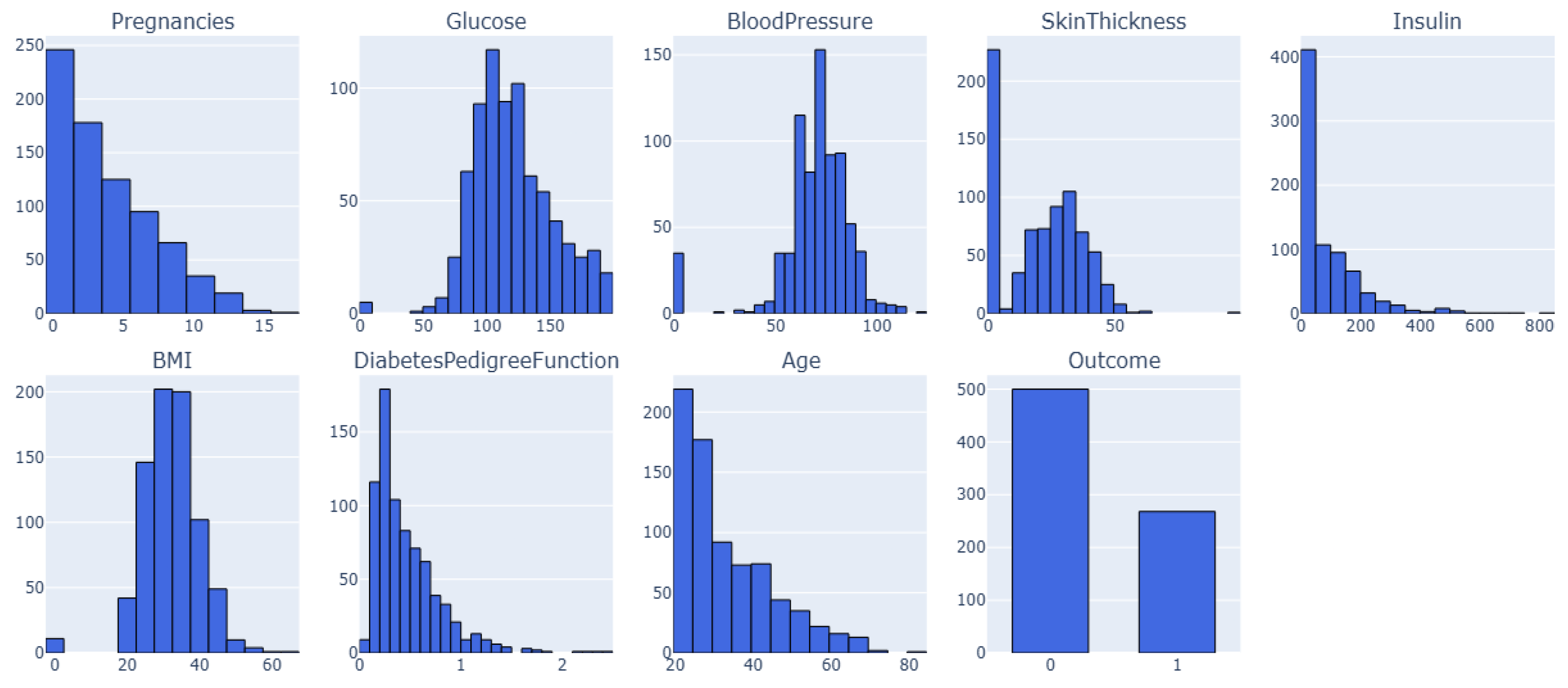

3.4.1. Dataset 1

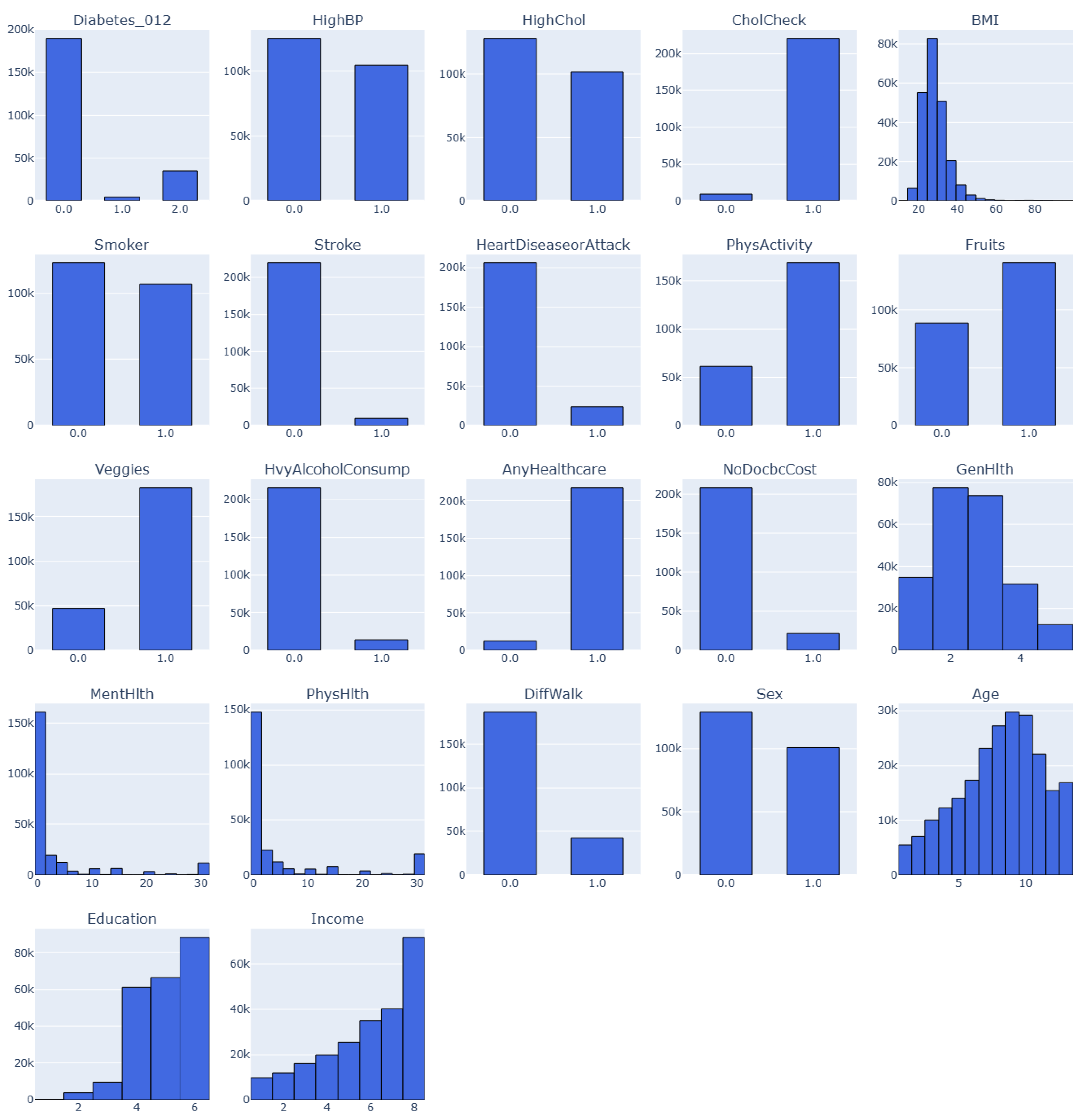

3.4.2. Dataset 2

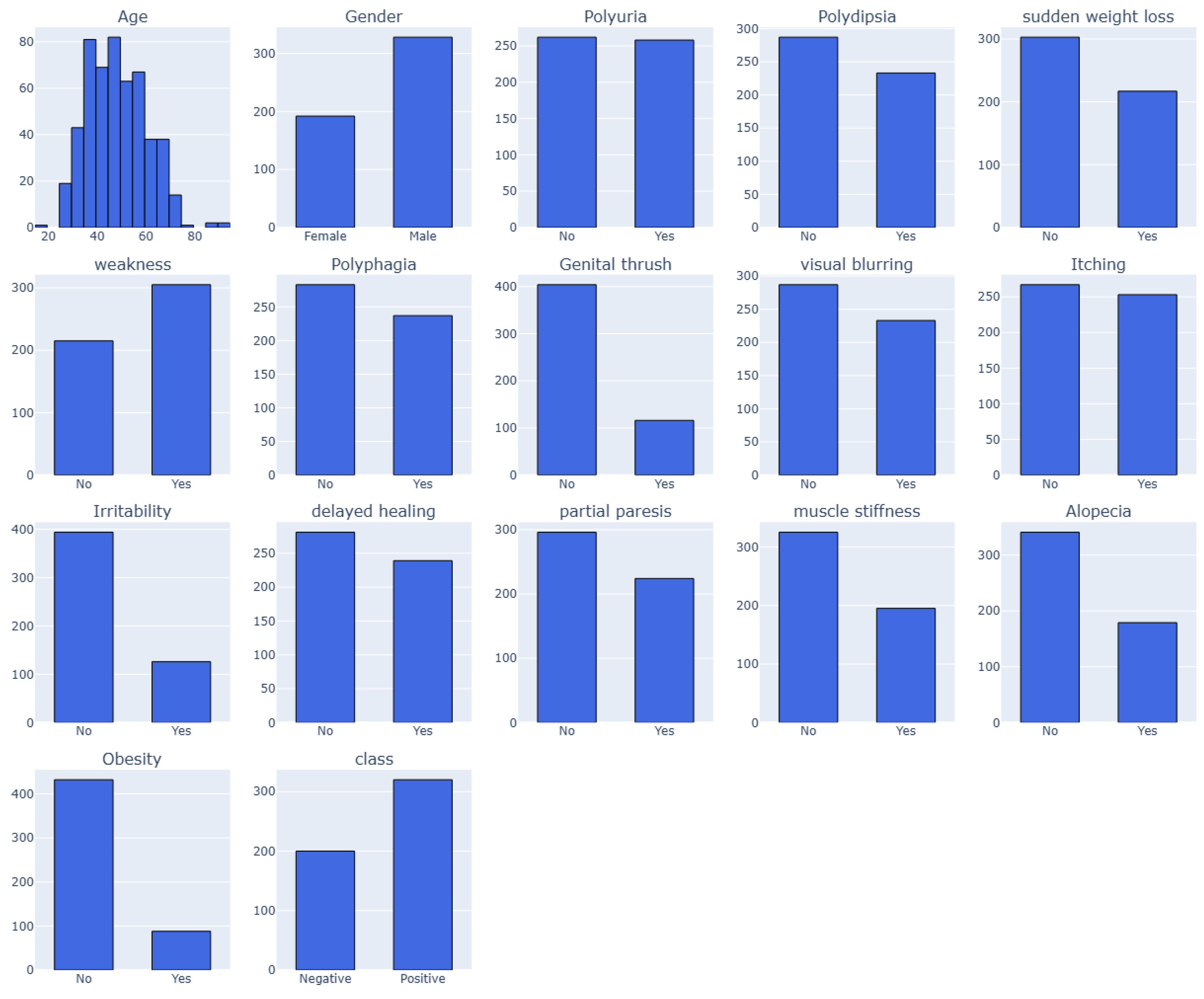

3.4.3. Dataset 3

3.4.4. Dataset 4

3.4.5. Dataset 5

3.5. Preprocessing

- Median Imputation: In each column, the median of non-zero values for zeros is substituted.

- Minimum Imputation: Instead of actual measurement, the zeros may mean data was not collected. This might indicate that the physiological levels of the patients with missing results were normal. Consequently, we used each column's smallest non-zero value to impute missing data.

4. Results Analysis

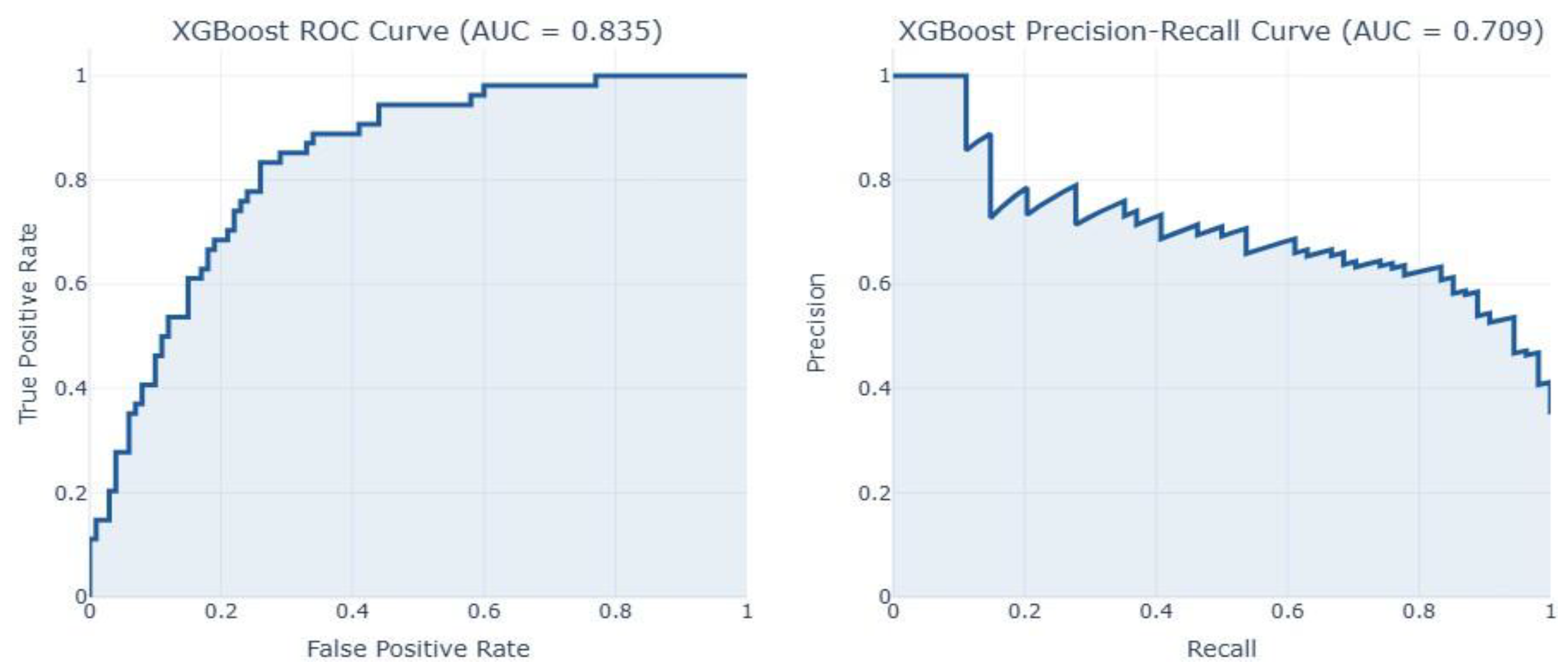

4.1. Result Analysis on Dataset 1

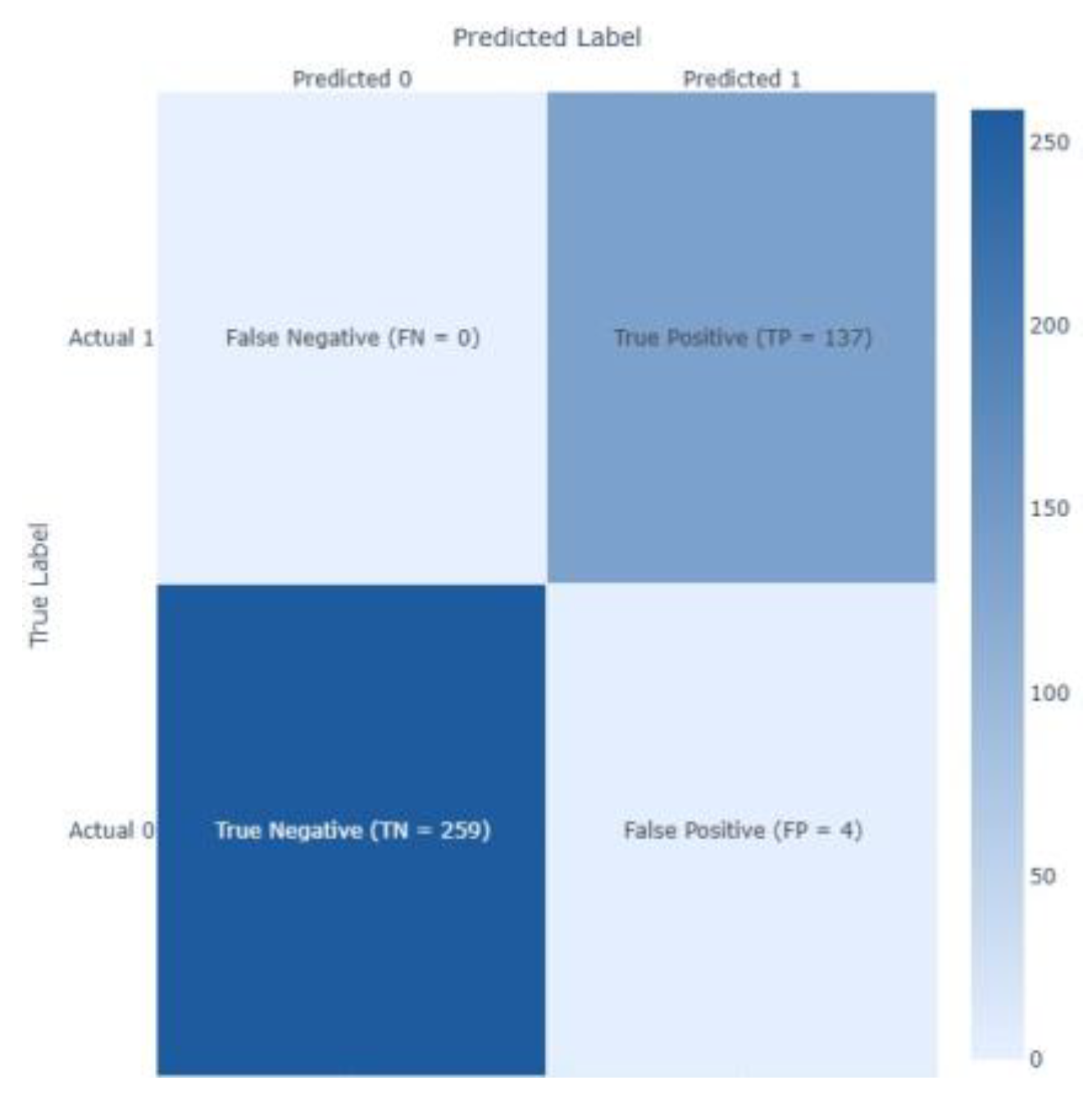

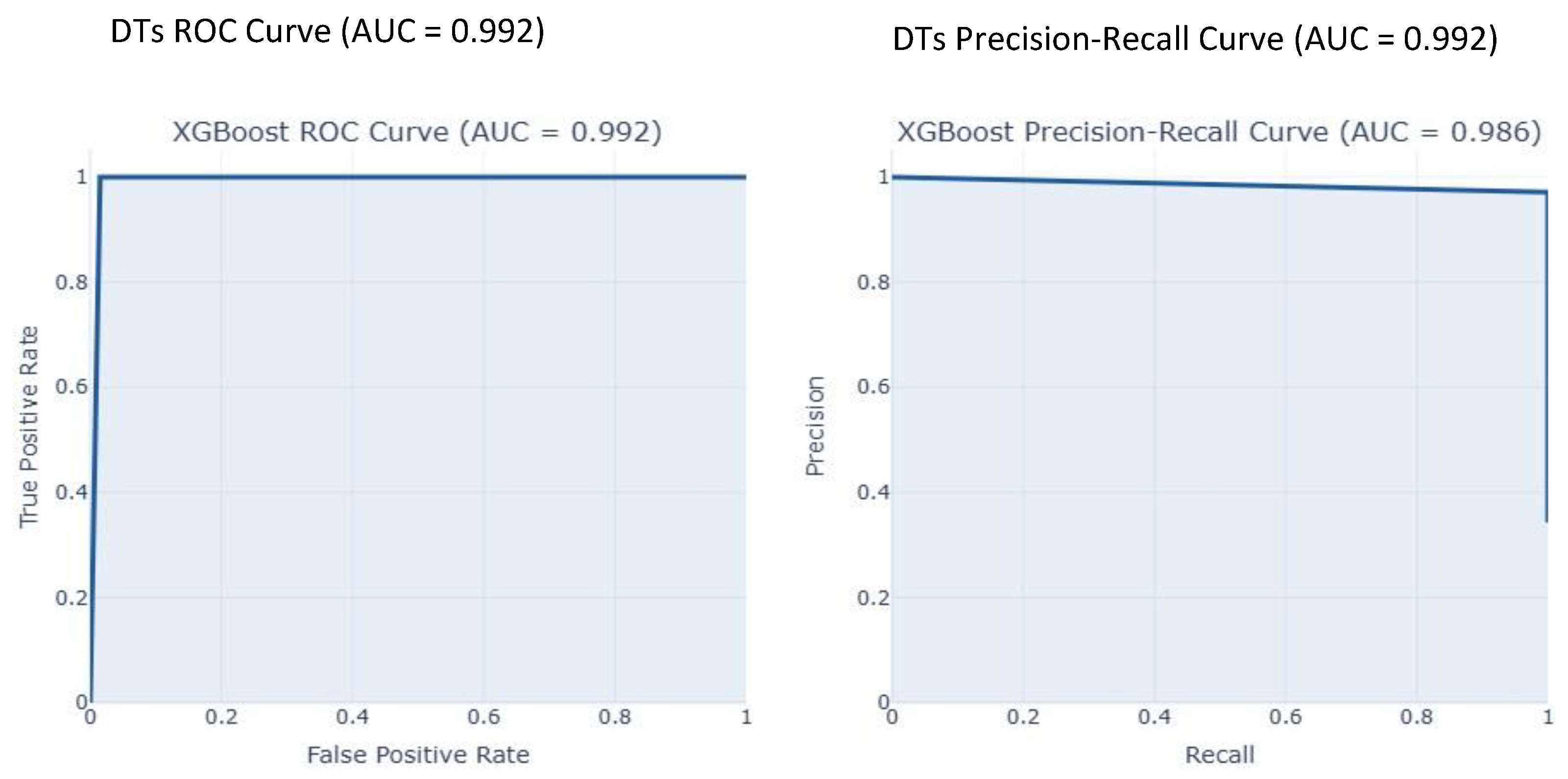

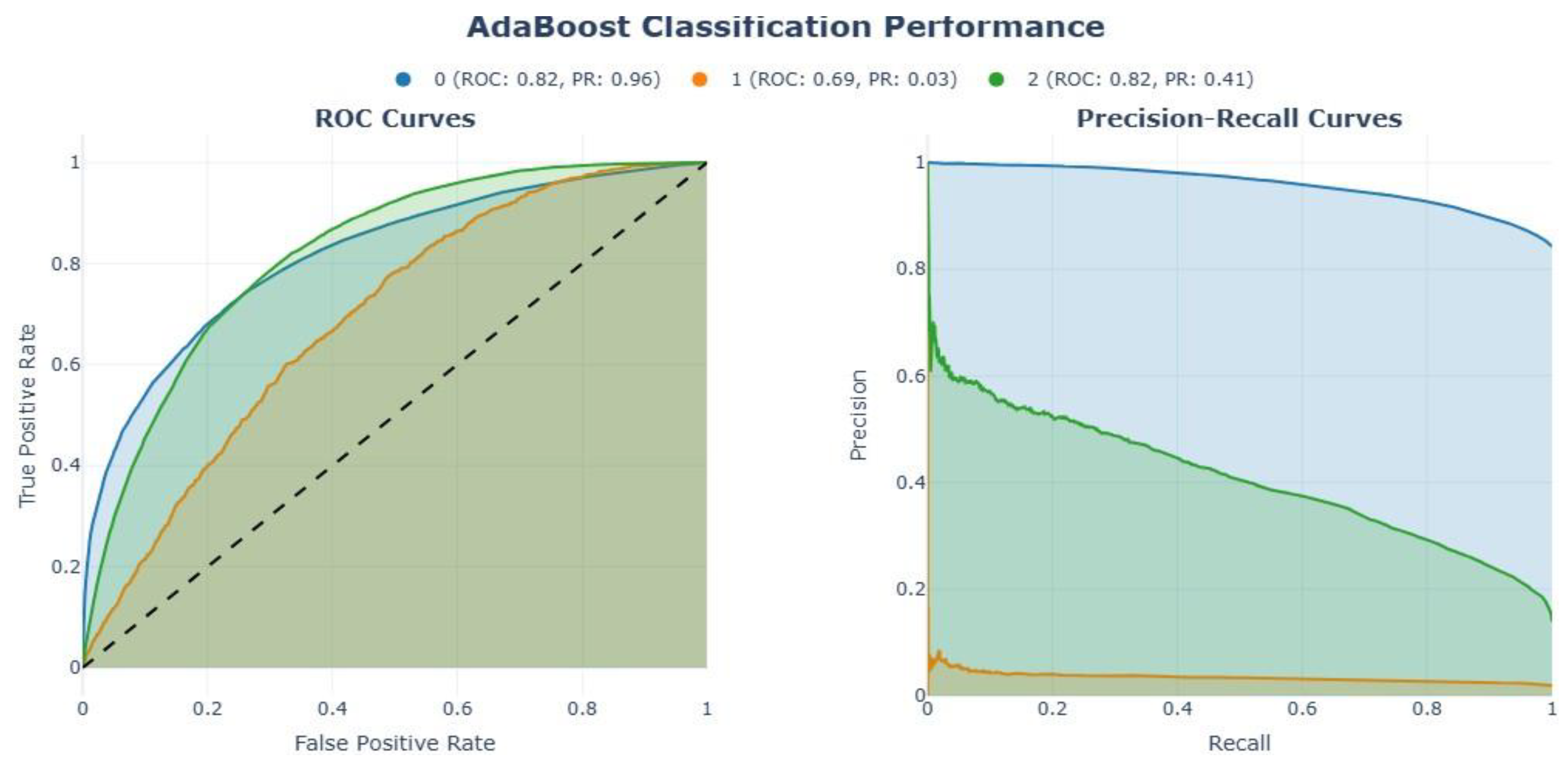

4.2. Result Analysis on Dataset 2

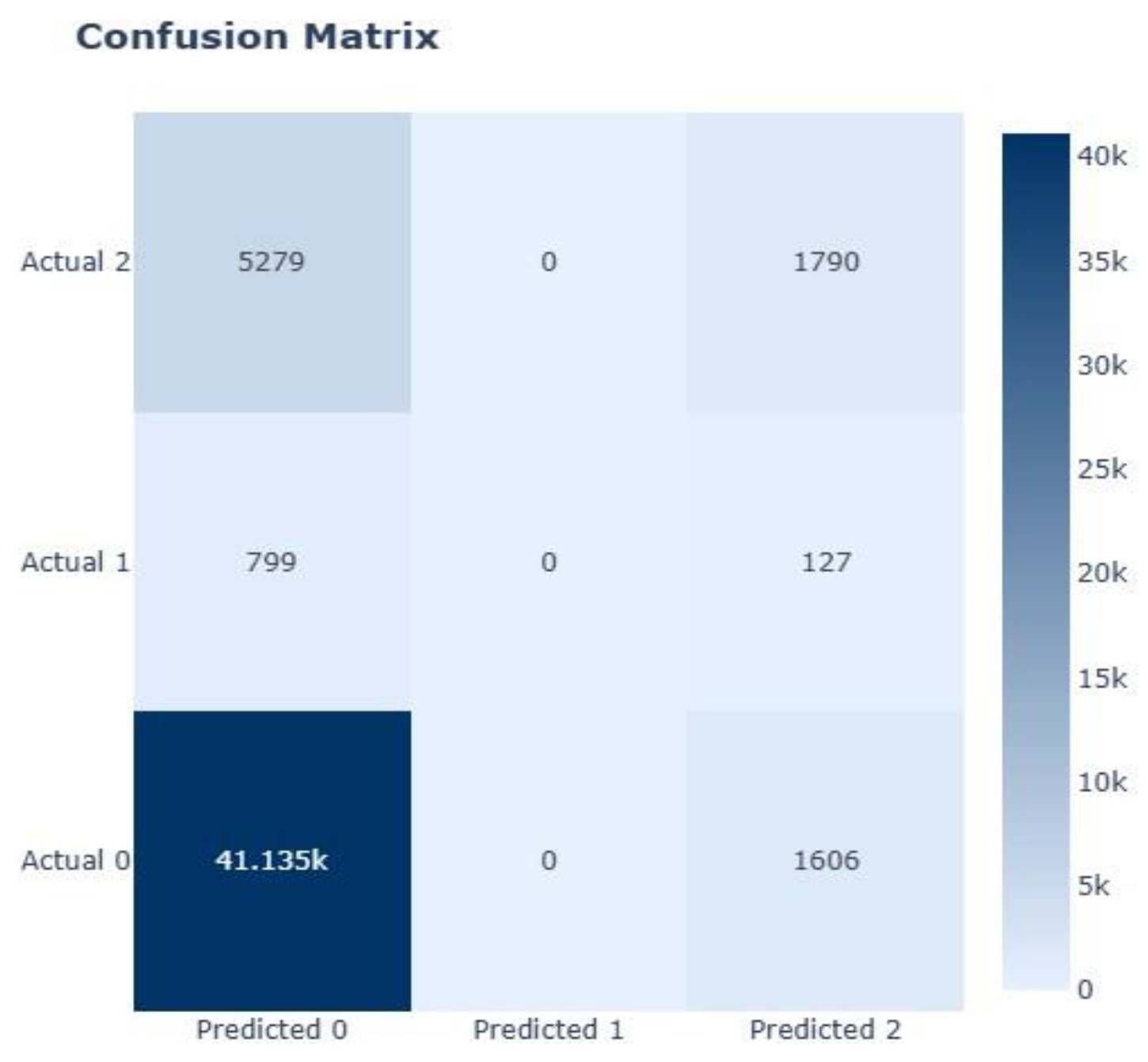

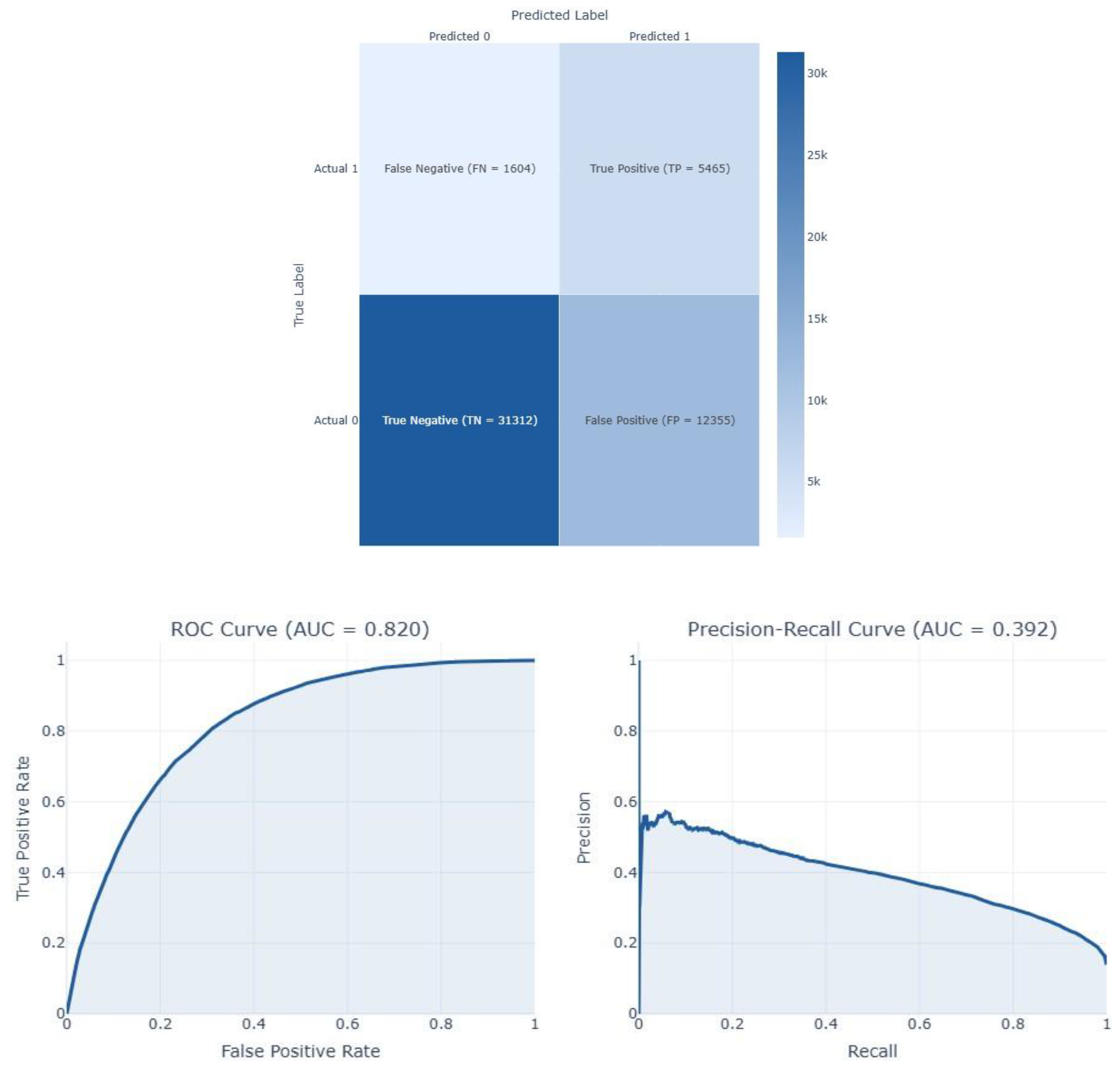

4.3. Result Analysis on Dataset 3

4.4. Result Analysis on Dataset 4

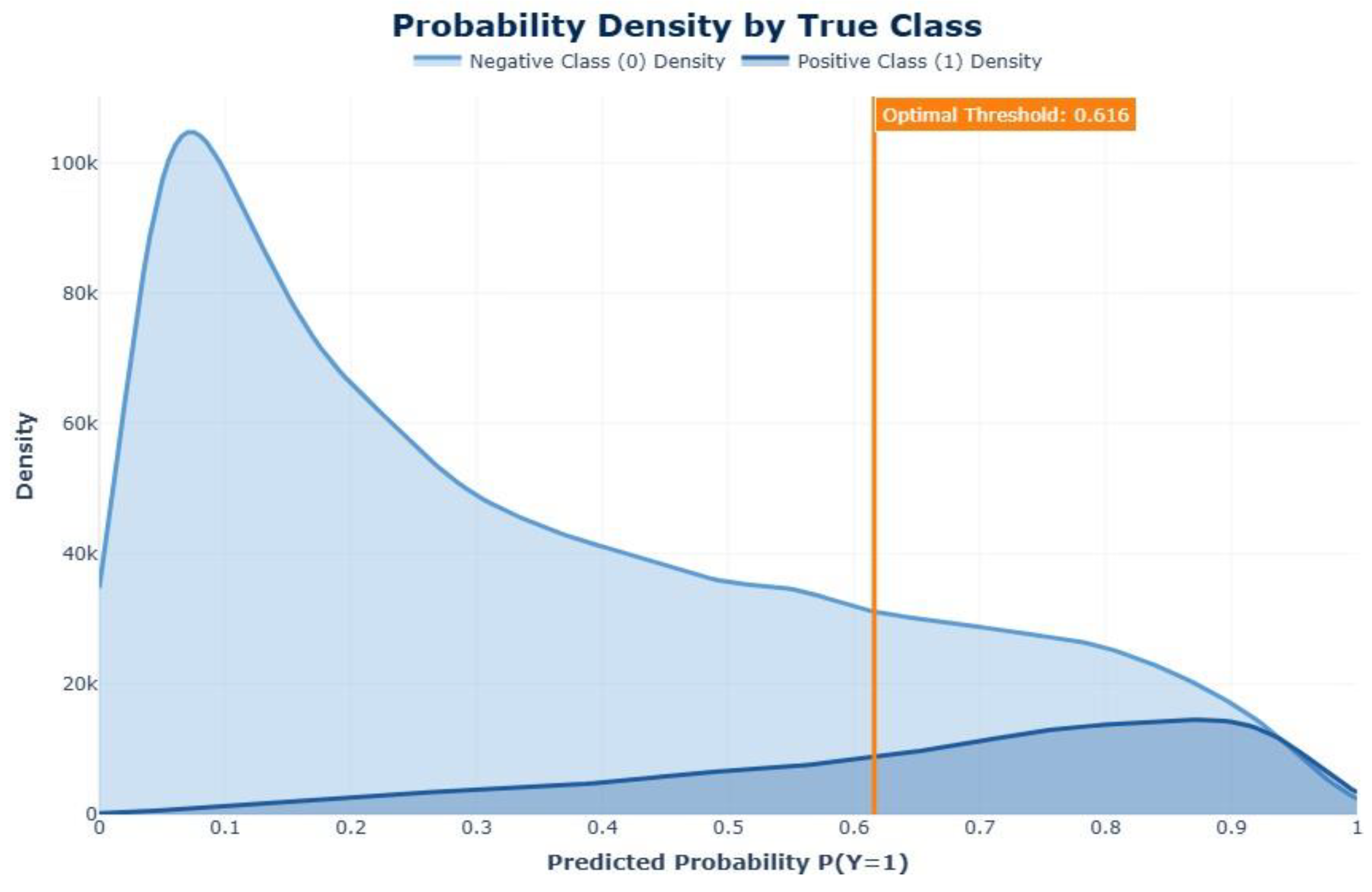

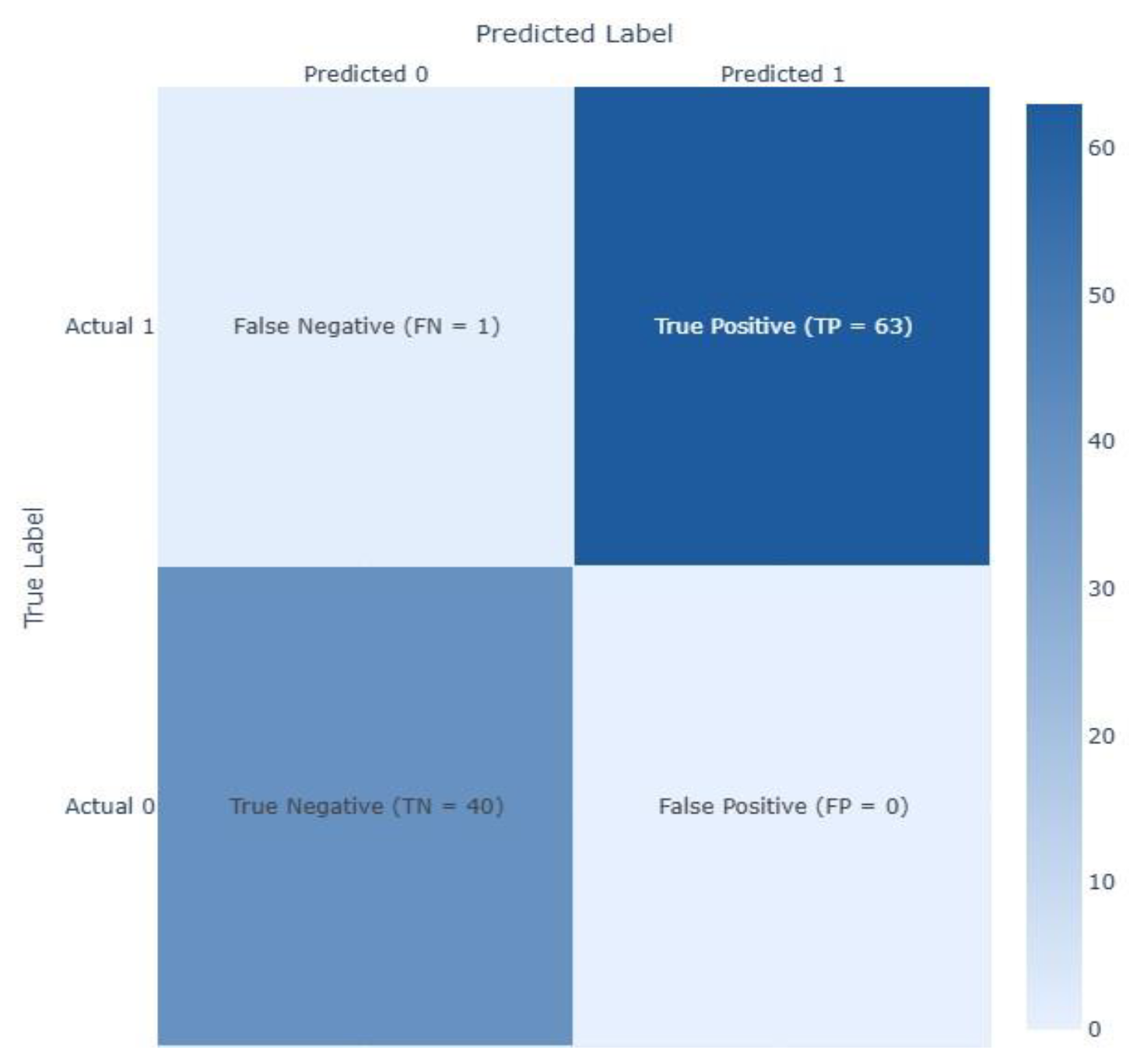

4.5. Result Analysis on Dataset 5

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Analysis of Results with Already Developed Diabetes Prediction Models

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| AU-ROC | Area under the ROC |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicators |

| IDF | International Diabetes Federation |

| T1DM | Type 1 DM |

| T2DM | Type 2 DM |

| GDM | Gestational DM |

| RF | Random Forest |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| NN | Neural Networks |

| RNN | Recurrent NN |

| CNN | Convolutional NN |

| DNN | Deep NN |

| QML | Quantum ML |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbour |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| DT | Decision Tress |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

Appendix A

| Datasets Statistics Description | Dataset 1 | Dataset 2 | Dataset 3 | Dataset 4 | Dataset 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | UCL Machine Learning Repository, Kaggle and CDC websites | ||||

| Samples | 768 | 2000 | 253,680 | 253,680 | 520 |

| Features | 9 | 9 | 21 | 21 | 17 |

| Positive instances | 268 | 684 | 35346 | 35346 | 320 |

| Negative instances | 500 | 1316 | 218334 | 35346 | 200 |

References

- Kavakiotis, O. Tsave, A. Salifoglou, N. Maglaveras, I. Vlahavas, and I. Chouvarda, "Machine Learning and Data Mining Methods in Diabetes Research," Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, vol. 15, pp. 104-116, 2017. [CrossRef]

- IDF, International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas 2021 (IDF Atlas 2021). 2021, pp. 1-141.

- M. A. R. Refat, M. A. Amin, C. Kaushal, M. N. Yeasmin, and M. K. Islam, "A Comparative Analysis of Early Stage Diabetes Prediction using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approach," in 6th IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Computing and Control (ISPCC), Solan, India, 2021 2021: IEEE, pp. 654-659. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9609364/. [CrossRef]

- S. Ayon and M. M. Islam, "Diabetes Prediction: A Deep Learning Approach," International Journal of Information Engineering and Electronic Business, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 21-27, 2019. [CrossRef]

- U. M. Butt et al., "Machine Learning Based Diabetes Classification and Prediction for Healthcare Applications," Journal of Healthcare Engineering, vol. 2021, pp. 9930985-17, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Alex David et al., "Comparative Analysis of Diabetes Prediction Using Machine Learning," in Soft Computing for Security Applications, vol. 1428, G. Ranganathan, X. Fernando, and S. Piramuthu Eds., (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Singapore: Springer, 2022, ch. 13, pp. 155-163.

- E. Longato, G. P. Fadini, G. Sparacino, A. Avogaro, L. Tramontan, and B. Di Camillo, "A Deep Learning Approach to Predict Diabetes' Cardiovascular Complications From Administrative Claims," IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics, vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 3608-3617, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Saeedi et al., "Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition," Diabetes Res Clin Pract, vol. 157, p. 107843, Nov 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Zarkogianni, M. Athanasiou, A. C. Thanopoulou, and K. S. Nikita, "Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches Toward Assessing the Risk of Developing Cardiovascular Disease as a Long-Term Diabetes Complication," IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 1637-1647, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Dinh, S. Miertschin, A. Young, and S. D. Mohanty, "A data-driven approach to predicting diabetes and cardiovascular disease with machine learning," BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 211, Nov 6 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Hasan et al., "Cardiovascular Disease Prediction Through Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models," presented at the 2023 International Conference on Modeling & E-Information Research, Artificial Learning and Digital Applications (ICMERALDA), Karawang, Indonesia, 24-24 November 2023, 2023.

- X. Lin et al., "Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories - an analysis from 1990 to 2025," Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, 14790, pp. 1-11, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Kodama et al., "Predictive ability of current machine learning algorithms for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis," J Diabetes Investig, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 900-908, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Larabi-Marie-Sainte, L. Aburahmah, R. Almohaini, and T. Saba, "Current Techniques for Diabetes Prediction: Review and Case Study," Applied sciences, vol. 9, no. 21, p. 4604, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Islam and F. Tariq, "Machine Learning-Enabled Detection and Management of Diabetes Mellitus," in Artificial Intelligence for Disease Diagnosis and Prognosis in Smart Healthcare, 2023, pp. 203-218.

- E. Afsaneh, A. Sharifdini, H. Ghazzaghi, and M. Z. Ghobadi, "Recent applications of machine learning and deep learning models in the prediction, diagnosis, and management of diabetes: a comprehensive review," Diabetol Metab Syndr, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 196, Dec 27 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Giacomo, V. Martina, S. Giovanni, and F. Andrea, "Continuous Glucose Monitoring Sensors for Diabetes Management - A Review of Technologies and Applications," Diabetes Metabolism Journal, vol. 43, pp. 383-397, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M. Noguchi, M. Kometani, K. Furukawa, and T. Yoneda, "Artificial Intelligence in Current Diabetes Management and Prediction," Curr Diab Rep, vol. 21, no. 12, p. 61, Dec 13 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guan et al., "Artificial intelligence in diabetes management: Advancements, opportunities, and challenges," Cell Rep Med, vol. 4, no. 10, p. 101213, Oct 17 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Lu et al., "Digital Health and Machine Learning Technologies for Blood Glucose Monitoring and Management of Gestational Diabetes," IEEE Rev Biomed Eng, vol. 17, pp. 98-117, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Ba, S. Li, and Y. Wei, "A data-driven machine learning integrated wearable medical sensor framework for elderly care service," Measurement, vol. 167, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Kakoly, M. R. Hoque, and N. Hasan, "Data-Driven Diabetes Risk Factor Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms with Feature Selection Technique," Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 1-15, 2023, Art no. 4930. [CrossRef]

- T. Mora, D. Roche, and B. Rodriguez-Sanchez, "Predicting the onset of diabetes-related complications after a diabetes diagnosis with machine learning algorithms," Diabetes Res Clin Pract, vol. 204, pp. 1-7, Oct 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. C. Han, J. Kim, and J. Choi, "Prediction of complications in diabetes mellitus using machine learning models with transplanted topic model features," Biomedical engineering letters, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 163-171, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dagliati et al., "Machine Learning Methods to Predict Diabetes Complications," Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 295-302, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Ochocinski et al., "Life-Threatening Infectious Complications in Sickle Cell Disease: A Concise Narrative Review," Front Pediatr, vol. 8, p. 38, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. R. Tan et al., "Evaluation of Machine Learning Methods Developed for Prediction of Diabetes Complications: A Systematic Review," Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 474-489, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Chauhan, M. S. Varre, K. Izuora, M. B. Trabia, and J. S. Dufek, "Prediction of Diabetes Mellitus Progression Using Supervised Machine Learning," Sensors (Basel), vol. 23, no. 10, May 11 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Skyler et al., "Differentiation of Diabetes by Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Prognosis," Diabetes, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 241-255, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Banday, A. S. Sameer, and S. Nissar, "Pathophysiology of diabetes - An overview," Avicenna Journal of Medicine, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 174–188, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Y. Fujimoto, "The Importance of Insulin Resistance in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus," American Journal of Medicine, vol. 108, 6A, pp. 9S-14S, 2000. [CrossRef]

- U. Galicia-Garcia et al., "Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus," International Journal of Molecular Science, vol. 21, no. 17, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Agliata, D. Giordano, F. Bardozzo, S. Bottiglieri, A. Facchiano, and R. Tagliaferri, "Machine Learning as a Support for the Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes," Int J Mol Sci, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 1-14, Apr 5 2023, Art no. 6775. [CrossRef]

- H. D. McIntyre, P. Catalano, C. Zhang, G. Desoye, E. R. Mathiesen, and P. Damm, "Gestational diabetes mellitus," Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-19, 2019, Art no. 47. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Plows, J. L. Stanley, P. N. Baker, C. M. Reynolds, and M. H. Vickers, "The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus," International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 1-21, 2018, Art no. 3342. [CrossRef]

- R. Ahmad, M. Narwaria, and M. Haque, "Gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence and progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus: A matter of global concern," Advances in Human Biology, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 232-237, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Mahajan, S. Uddin, F. Hajati, M. A. Moni, and E. Gide, "A comparative evaluation of machine learning ensemble approaches for disease prediction using multiple datasets," Health and technology, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 597-613, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Flores, R. M. Hernandez, L. H. Macatangay, S. M. G. Garcia, and J. R. Melo, "Comparative analysis in the prediction of early-stage diabetes using multiple machine learning techniques," Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 32, no. 2, p. 887, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Gupta, H. Varshney, T. K. Sharma, N. Pachauri, and O. P. Verma, "Comparative performance analysis of quantum machine learning with deep learning for diabetes prediction," Complex & intelligent systems, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 3073-3087, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Aggarwal, C. B. Basha, A. Arya, and N. Gupta, "A Comparative Analysis of Machine Leaming-Based Classifiers for Predicting Diabetes," presented at the 2023 International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Technologies (ICACCTech), Banur, India, 23-24 December 20, 2023.

- M. A. R. Refat, M. A. Amin, C. Kaushal, M. N. Yeasmin, and M. K. Islam, "A Comparative Analysis of Early Stage Diabetes Prediction using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approach," in 6th IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Computing and Control (ISPCC 2k21), Solan, India, 2021 2021: IEEE, pp. 654-659. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stampPDF/getPDF.jsp?tp=&arnumber=9609364&ref=. [CrossRef]

- M. Swathy and K. Saruladha, "A comparative study of classification and prediction of Cardio-Vascular Diseases (CVD) using Machine Learning and Deep Learning techniques," ICT Express, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 109-116, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Fregoso-Aparicio, J. Noguez, L. Montesinos, and J. A. Garcia-Garcia, "Machine learning and deep learning predictive models for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review," Diabetology and Metabolic Syndrome, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 148-148, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Uddin, A. Khan, M. E. Hossain, and M. A. Moni, "Comparing different supervised machine learning algorithms for disease prediction," BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 281-281, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Naz and S. Ahuja, "Deep learning approach for diabetes prediction using PIMA Indian dataset," Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 391-403, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Hasan, M. A. Alam, D. Das, E. Hossain, and M. Hasan, "Diabetes Prediction Using Ensembling of Different Machine Learning Classifiers," IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 76516-76531, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Sahoo, C. Pradhan, H. Das, M. Rout, H. Das, and J. K. Rout, "Performance Evaluation of Different Machine Learning Methods and Deep-Learning Based Convolutional Neural Network for Health Decision Making," in Nature Inspired Computing for Data Science, vol. 871, M. Rout, J. K. Rout, and H. Das Eds., (Studies in Computational Intelligence. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 2020, ch. Chapter 8, pp. 201-212.

- H. Lai, H. Huang, K. Keshavjee, A. Guergachi, and X. Gao, "Predictive models for diabetes mellitus using machine learning techniques," BMC Endocrine Disorders, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 101-101, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Elreedy and A. F. Atiya, "A Comprehensive Analysis of Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) for handling class imbalance," Information Sciences, vol. 505, pp. 32-64, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Wongvorachan, S. He, and O. Bulut, "A Comparison of Undersampling, Oversampling, and SMOTE Methods for Dealing with Imbalanced Classification in Educational Data Mining," Information - MDPI, vol. 14, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Kaur, R. Sharma, and M. K. Dhaliwal, "Evaluating Performance of SMOTE and ADASYNtoClassify Falls and Activities of Daily Living," in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Soft Computing for Problem Solving. SocProS 2023, Springer, Singapore, M. Pant, K. Deep, and A. Nagar, Eds., 2024, vol. 995: Springer, in Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. [CrossRef]

- R. Panigrahi, L. Kumar, and S. K. Kuanar, "An Empirical Study to Investigate Different SMOTE Data Sampling Techniques for Improving Software Refactoring Prediction," in Neural Information Processing. ICONIP 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol. 1332, H. Yang, K. Pasupa, A. C. Leung, J. T. Kwok, J. H. Chan, and I. e. King Eds. Switzerland: Springer, Cham, 2020, pp. 23-31.

- H. Sahlaoui, E. A. A. Alaoui, S. Agoujil, and A. Nayyar, "An empirical assessment of smote variants techniques and interpretation methods in improving the accuracy and the interpretability of student performance models," Education and Information Technologies, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 5447-5483, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Haibo, B. Yang, E. A. Garcia, and L. Shutao, "ADASYN: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning," presented at the 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), 2008.

- E. A. Elsoud et al., "Under Sampling Techniques for Handling Unbalanced Data with Various Imbalance Rates - A Comparative Study," International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA), vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 1274-1284, 2024.

- M. Bach and A. Werner, "Improvement of Random Undersampling to Avoid Excessive Removal of Points from a Given Area of the Majority Class," in Computational Science – ICCS 2021 - 21st International Conference Krakow, Poland, June 16–18, 2021 Proceedings, Part III, Poland, M. Paszynski, D. Kranzlmüller, V. V. Krzhizhanovskaya, J. J. Dongarra, and P. M. Sloot, Eds., 2021, vol. 12744: Springer, Cham, in ICCS 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 172-186. [CrossRef]

- G.Rekha, A. K. Tyagi, and V. K. Reddy, "Performance Analysis of Under-Sampling and Over-Sampling Techniques for Solving Class Imbalance Problem," International Conference on Sustainable Computing in Science, Technology & Management (SUSCOM-2019), pp. 1305-1315, Feb 26-28, 2019 2019.

- R. D. Joshi and C. K. Dhakal, "Predicting Type 2 Diabetes Using Logistic Regression and Machine Learning Approaches," International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 14, pp. 1-17, 2021, Art no. 7346. [CrossRef]

- M. Maniruzzaman et al., "Accurate Diabetes Risk Stratification Using Machine Learning: Role of Missing Value and Outliers," J Med Syst, vol. 42, no. 5, p. 92, Apr 10 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Mittal and Y. Hasija, "Applications of Deep Learning in Healthcare and Biomedicine," in Deep Learning Techniques for Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 68, S. Dash, B. R. Acharya, M. Mittal, A. Abraham, and A. Kelemen Eds. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 2019, ch. Chapter 4, pp. 57-78.

- Iyer, J. S, and R. Sumbaly, "Diagnosis of Diabetes Using Classification Mining Techniques," International journal of data mining & knowledge management process, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-14, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Barik, S. Mohanty, S. Mohanty, and D. Singh, "Analysis of Prediction Accuracy of Diabetes Using Classifier and Hybrid Machine Learning Techniques," in Intelligent and Cloud Computing, D. Mishra, R. Buyya, P. Mohapatra, and S. Patnaik Eds., (Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020, pp. 399-409.

- S. M. Ganie, M. B. Malik, and T. Arif, "Performance analysis and prediction of type 2 diabetes mellitus based on lifestyle data using machine learning approaches," Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 339-352, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Iparraguirre-Villanueva, K. Espinola-Linares, R. O. Flores Castaneda, and M. Cabanillas-Carbonell, "Application of Machine Learning Models for Early Detection and Accurate Classification of Type 2 Diabetes," Diagnostics (Basel), vol. 13, no. 14, Jul 15 2023. [CrossRef]

- Altamimi et al., "An automated approach to predict diabetic patients using KNN imputation and effective data mining techniques," BMC Medical Research Methodology, vol. 24, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Suriya and J. J. Muthu, "Type 2 Diabetes Prediction using K-Nearest Neighbor Algorithm," Journal of Trends in Computer Science and Smart Technology, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 190-205, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Salam and R. Rafi, "Deep Learning Approach for Sleep Apnea Detection Using Single Lead ECG: Comparative Analysis Between CNN and SNN," presented at the 2023 26th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13-15 December 2023, 2023.

- M. Rahman, D. Islam, R. J. Mukti, and I. Saha, "A deep learning approach based on convolutional LSTM for detecting diabetes," Computational biology and chemistry, vol. 88, pp. 107329-107329, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. K. P, S. P. R, N. R K, and A. K, "Type 2: Diabetes mellitus prediction using Deep Neural Networks classifier," International Journal of Cognitive Computing in Engineering, vol. 1, pp. 55-61, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Wadghiri, A. Idri, T. E. Idrissi, and H. Hakkoum, "Ensemble blood glucose prediction in diabetes mellitus - A review," Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, vol. 147, 105674, pp. 1-25, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guan and T. Plotz, "Ensembles of Deep LSTM Learners for Activity Recognition using Wearables," ACM, vol. 0, pp. 1-28, 2017.

- M. Y. Shams, Z. Tarek, and A. M. Elshewey, "A novel RFE-GRU model for diabetes classification using PIMA Indian dataset," Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 982, Jan 6 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Raquibul Hossain, M. J. Hossain, M. M. Rahman, and M. Manjur Alam, "Machine Learning Based Prediction and Insights of Diabetes Disease: Pima Indian and Frankfurt Datasets," Journal of Mechanics of Continua and Mathematical Sciences, vol. 20, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mousa, W. Mustafa, and R. B. Marqas, "A Comparative Study of Diabetes Detection Using The Pima Indian Diabetes Database," The Journal of University of Duhok, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 277-288, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Zargar, A. Bhagat, T. A. Teli, and S. Sheikh, "Early Prediction of Diabetes Mellitus on Pima Dataset Using ML And DL Techniques," Journal of Army Engineering University of PLA, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 230-249, 2023.

- V. Chang, J. Bailey, Q. A. Xu, and Z. Sun, "Pima Indians diabetes mellitus classification based on machine learning (ML) algorithms," Neural Comput Appl, pp. 1-17, Mar 24 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xie, O. Nikolayeva, J. Luo, and D. Li, "Building Risk Prediction Models for Type 2 Diabetes Using Machine Learning Techniques," Prev Chronic Dis, vol. 16, p. E130, Sep 19 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. M. F. Islam, R. Ferdousi, S. Rahman, and H. Y. Bushra, "Likelihood Prediction of Diabetes at Early Stage Using Data Mining Techniques," in Computer Vision and Machine Intelligence in Medical Image Analysis, (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 2020, ch. Chapter 12, pp. 113-125.

- Sadhu and A. Jadli, "Early-Stage Diabetes Risk Prediction - A Comparative Analysis of Classification Algorithms," International Advanced Research Journal in Science, Engineering and Technology, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 193-201, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. A. Al-Haija, M. Smadi, and O. M. Al-Bataineh, "Early Stage Diabetes Risk Prediction via Machine Learning," Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Soft Computing and Pattern Recognition (SoCPaR 2021), vol. 417, pp. 451-461, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Chatrati et al., "Smart home health monitoring system for predicting type 2 diabetes and hypertension," Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 862-870, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Bozkurt, N. Yurtay, Z. Yilmaz, and C. Sertkaya, "Comparison of different methods for determining diabetes," Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering & Computer Sciences, vol. 22, pp. 1044-1055, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Bashir, U. Qamar, and F. H. Khan, "IntelliHealth: A medical decision support application using a novel weighted multi-layer classifier ensemble framework," J Biomed Inform, vol. 59, pp. 185-200, Feb 2016. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, W. Cao, J. Guo, J. Ren, Y. Cheng, and D. N. Davis, "DMP_MI: An Effective Diabetes Mellitus Classification Algorithm on Imbalanced Data With Missing Values," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 102232-102238, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Kaur and V. Kumari, "Predictive modelling and analytics for diabetes using a machine learning approach," Applied Computing and Informatics, vol. 18, no. 1/2, pp. 90-100, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Yuvaraj and K. R. SriPreethaa, "Diabetes prediction in healthcare systems using machine learning algorithms on Hadoop cluster," Cluster Computing, vol. 22, no. S1, pp. 1-9, 2017. [CrossRef]

| Feature | Dataset 1 | Dataset 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancies | 111 | 301 |

| Glucose | 5 | 13 |

| BloodPressure | 35 | 90 |

| SkinThickness | 227 | 573 |

| Insulin | 374 | 956 |

| BMI | 11 | 28 |

| DiabetesPedigreeFunction | 0 | 0 |

| Age | 0 | 0 |

| Outcome (Target class) | Dataset 1 | Dataset 2 | Dataset 3 | Dataset 4 | Dataset 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 400 | 1053 | 213703 | 218334 | 200 |

| 1 | 214 | 547 | 4631 | 35346 | 320 |

| 2 | - | - | 35346 | - | - |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | AUC-ROC | Time Taken (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.7727 | 0.6301 | 0.8519 | 0.7244 | 0.8356 | 0.0122 |

| XGBoost-CNN | 0.7727 | 0.6338 | 0.8333 | 0.7200 | 0.8224 | 4.3404 |

| AdaBoost | 0.7727 | 0.6338 | 0.8333 | 0.7200 | 0.8411 | 0.0091 |

| DNN | 0.7727 | 0.6377 | 0.8148 | 0.7154 | 0.8219 | 0.0144 |

| RF-GRU | 0.7597 | 0.6164 | 0.8333 | 0.7087 | 0.8120 | 9.1299 |

| Random Forest | 0.7597 | 0.6232 | 0.7963 | 0.6992 | 0.8196 | 0.0095 |

| Decision Tree | 0.7597 | 0.6308 | 0.7593 | 0.6891 | 0.7984 | 0.0167 |

| SVM | 0.7532 | 0.6176 | 0.7778 | 0.6885 | 0.8213 | 0.0145 |

| KNN | 0.7403 | 0.5946 | 0.8148 | 0.6875 | 0.8077 | 0.0147 |

| RF-CNN | 0.7597 | 0.6349 | 0.7407 | 0.6838 | 0.8120 | 0.0134 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.7468 | 0.6087 | 0.7778 | 0.6829 | 0.8189 | 0.0138 |

| LR-MLP | 0.7403 | 0.6029 | 0.7593 | 0.6721 | 0.8200 | 2.4844 |

| SVM-RNN | 0.7468 | 0.6119 | 0.7593 | 0.6777 | 0.8225 | 6.7487 |

| XGBoost-LSTM | 0.7403 | 0.6000 | 0.7778 | 0.6774 | 0.8219 | 11.4212 |

| DT-CNN | 0.6818 | 0.5275 | 0.8889 | 0.6621 | 0.7946 | 5.4317 |

| AdaBoost-DBN | 0.7013 | 0.5526 | 0.7778 | 0.6462 | 0.8004 | 18.8776 |

| CNN | 0.7143 | 0.5694 | 0.7593 | 0.6508 | 0.8219 | 0.0165 |

| KNN-Autoencoders | 0.6883 | 0.5417 | 0.7222 | 0.6190 | 0.7711 | 9.5224 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.6948 | 0.5522 | 0.6852 | 0.6116 | 0.7676 | 0.0908 |

| RNN | 0.6948 | 0.5522 | 0.6852 | 0.6116 | 0.7806 | 0.0110 |

| GRU | 0.6623 | 0.5156 | 0.6111 | 0.5593 | 0.7000 | 0.0106 |

| LSTM | 0.6688 | 0.5246 | 0.5926 | 0.5565 | 0.7013 | 0.0171 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | AUC-ROC | Time Taken (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 0.9900 | 0.9716 | 1.0000 | 0.9856 | 0.9924 | 0.0276 |

| Random Forest | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9972 | 0.0104 |

| KNN | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9942 | 0.0097 |

| AdaBoost | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9993 | 0.0091 |

| RF-CNN | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9972 | 0.0158 |

| XGBoost-LSTM | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9893 | 14.9132 |

| RF-GRU | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9958 | 9.6351 |

| XGBoost-CNN | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | 0.9888 | 6.3965 |

| DT-CNN | 0.9750 | 0.9504 | 0.9781 | 0.9640 | 0.9757 | 7.1950 |

| SVM-RNN | 0.9575 | 0.9167 | 0.9635 | 0.9395 | 0.9767 | 8.6150 |

| SVM | 0.9550 | 0.9103 | 0.9635 | 0.9362 | 0.9693 | 0.0136 |

| XGBoost | 0.9475 | 0.8867 | 0.9708 | 0.9268 | 0.9867 | 0.0107 |

| KNN-Autoencoders | 0.9125 | 0.8036 | 0.9854 | 0.8852 | 0.9871 | 21.7245 |

| AdaBoost-DBN | 0.8350 | 0.7052 | 0.8905 | 0.7871 | 0.9349 | 22.0284 |

| DNN | 0.8250 | 0.6872 | 0.8978 | 0.7785 | 0.9140 | 0.0123 |

| LR-MLP | 0.7975 | 0.6628 | 0.8321 | 0.7379 | 0.8891 | 11.9994 |

| CNN | 0.7800 | 0.6369 | 0.8321 | 0.7215 | 0.8590 | 0.0108 |

| RNN | 0.7600 | 0.6051 | 0.8613 | 0.7108 | 0.8549 | 0.0104 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.7600 | 0.6145 | 0.8029 | 0.6962 | 0.8524 | 0.0263 |

| GRU | 0.7400 | 0.5846 | 0.8321 | 0.6867 | 0.8467 | 0.0186 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.7525 | 0.6159 | 0.7372 | 0.6711 | 0.8322 | 0.0269 |

| LSTM | 0.7000 | 0.5464 | 0.7299 | 0.6250 | 0.7963 | 0.0240 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | AUC-ROC | Time Taken (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AdaBoost | 0.6973 | 0.4317 | 0.5122 | 0.4314 | 0.7103 | 19.4743 |

| XGBoost-CNN | 0.7018 | 0.4304 | 0.5088 | 0.4271 | 0.7167 | 55.5742 |

| XGBoost | 0.7044 | 0.4293 | 0.5068 | 0.4265 | 0.7137 | 6.0555 |

| RF-CNN | 0.6693 | 0.4314 | 0.5112 | 0.4249 | 0.7107 | 37.4420 |

| Random Forest | 0.6799 | 0.4274 | 0.5045 | 0.4244 | 0.6997 | 14.5153 |

| XGBoost-LSTM | 0.6936 | 0.4273 | 0.5049 | 0.4240 | 0.7094 | 198.5152 |

| RF-GRU | 0.6599 | 0.4328 | 0.5115 | 0.4230 | 0.7085 | 141.7040 |

| DT-CNN | 0.6890 | 0.4227 | 0.4783 | 0.4218 | 0.6566 | 43.6537 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.6259 | 0.4498 | 0.5154 | 0.4192 | 0.7077 | 3.2978 |

| GRU | 0.6678 | 0.4327 | 0.4752 | 0.4161 | 0.6729 | 210.8736 |

| DNN | 0.6428 | 0.4281 | 0.5109 | 0.4134 | 0.7052 | 51.4291 |

| LR-MLP | 0.5936 | 0.4561 | 0.5197 | 0.4117 | 0.7117 | 0.8947 |

| Decision Tree | 0.6329 | 0.4247 | 0.5028 | 0.4079 | 0.6878 | 0.2390 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.6245 | 0.4364 | 0.4892 | 0.4083 | 0.6803 | 0.1709 |

| CNN | 0.5787 | 0.4358 | 0.5180 | 0.3988 | 0.7037 | 69.0522 |

| SVM | 0.5775 | 0.4418 | 0.5012 | 0.3978 | 0.7005 | 453.5940 |

| KNN-Autoencoders | 0.5590 | 0.4116 | 0.4473 | 0.3650 | 0.6232 | 19.3189 |

| KNN (Normal) | 0.5327 | 0.4125 | 0.4476 | 0.3589 | 0.6251 | 25.1546 |

| AdaBoost-DBN | 0.5393 | 0.4414 | 0.4854 | 0.3806 | 0.6775 | 364.6265 |

| RNN | 0.5858 | 0.4197 | 0.4958 | 0.3878 | 0.6863 | 119.7845 |

| LSTM | 0.6769 | 0.4097 | 0.4746 | 0.4030 | 0.6728 | 278.3175 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | AUC-ROC | Time Taken (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 0.7249 | 0.3067 | 0.7731 | 0.4392 | 0.8197 | 0.2650 |

| LR-MLP | 0.7144 | 0.3017 | 0.7990 | 0.4381 | 0.8235 | 50.7898 |

| AdaBoost | 0.7251 | 0.3062 | 0.7690 | 0.4380 | 0.8187 | 2.0871 |

| XGBoost | 0.7132 | 0.3005 | 0.7971 | 0.4365 | 0.8209 | 0.9791 |

| XGBoost-CNN | 0.7079 | 0.2969 | 0.8010 | 0.4332 | 0.8212 | 58.5367 |

| GRU | 0.7111 | 0.2985 | 0.7947 | 0.4340 | 0.8187 | 217.5773 |

| CNN | 0.7044 | 0.2959 | 0.8131 | 0.4339 | 0.8238 | 53.9654 |

| XGBoost-LSTM | 0.7072 | 0.2960 | 0.7990 | 0.4320 | 0.8204 | 208.5252 |

| SVM-RNN | 0.7021 | 0.2943 | 0.8138 | 0.4322 | 0.8112 | 1804.6831 |

| RNN | 0.7047 | 0.2947 | 0.8037 | 0.4313 | 0.8184 | 113.6648 |

| DNN | 0.6872 | 0.2864 | 0.8345 | 0.4264 | 0.8229 | 53.0682 |

| RF-GRU | 0.7036 | 0.2919 | 0.7906 | 0.4263 | 0.8101 | 252.4819 |

| LSTM | 0.7043 | 0.2925 | 0.7911 | 0.4271 | 0.8149 | 203.2224 |

| Random Forest | 0.7025 | 0.2899 | 0.7833 | 0.4232 | 0.8070 | 9.8154 |

| RF-CNN | 0.7034 | 0.2911 | 0.7864 | 0.4249 | 0.8095 | 76.8140 |

| AdaBoost-DBN | 0.6859 | 0.2855 | 0.8345 | 0.4254 | 0.8221 | 58.1984 |

| SVM | 0.7002 | 0.2917 | 0.8068 | 0.4285 | 0.8162 | 1541.3782 |

| KNN-Autoencoders | 0.6753 | 0.2624 | 0.7349 | 0.3868 | 0.7566 | 85.9556 |

| KNN | 0.6751 | 0.2620 | 0.7333 | 0.3861 | 0.7563 | 38.4936 |

| Decision Tree | 0.6599 | 0.2391 | 0.6599 | 0.3510 | 0.6606 | 0.3532 |

| DT-CNN | 0.6649 | 0.2417 | 0.6571 | 0.3534 | 0.6618 | 62.1882 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.7235 | 0.2941 | 0.7029 | 0.4147 | 0.7799 | 0.0977 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | AUC-ROC | Time Taken (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.9904 | 1.0000 | 0.9844 | 0.9921 | 1.0000 | 0.0074 |

| Decision Tree | 0.9904 | 1.0000 | 0.9844 | 0.9921 | 0.9922 | 0.0299 |

| AdaBoost | 0.9904 | 1.0000 | 0.9844 | 0.9921 | 0.9992 | 0.0389 |

| SVM | 0.9808 | 0.9844 | 0.9844 | 0.9844 | 0.9977 | 0.0181 |

| SVM-RNN | 0.9808 | 0.9844 | 0.9844 | 0.9844 | 0.9984 | 6.6874 |

| RF-GRU | 0.9808 | 1.0000 | 0.9688 | 0.9841 | 1.0000 | 8.2692 |

| RF-CNN | 0.9808 | 1.0000 | 0.9688 | 0.9841 | 0.9992 | 0.0132 |

| XGBoost-LSTM | 0.9808 | 1.0000 | 0.9688 | 0.9841 | 1.0000 | 11.2858 |

| XGBoost-CNN | 0.9808 | 1.0000 | 0.9688 | 0.9841 | 0.9977 | 4.1041 |

| CNN | 0.9712 | 0.9841 | 0.9688 | 0.9764 | 0.9977 | 0.0132 |

| DT-CNN | 0.9712 | 0.9841 | 0.9688 | 0.9764 | 0.9826 | 5.6472 |

| LR-MLP | 0.9712 | 0.9841 | 0.9688 | 0.9764 | 0.9992 | 9.9053 |

| XGBoost | 0.9615 | 0.9688 | 0.9688 | 0.9688 | 0.9926 | 0.0244 |

| KNN-Autoencoders | 0.9615 | 1.0000 | 0.9375 | 0.9677 | 0.9828 | 8.6576 |

| DNN | 0.9615 | 0.9839 | 0.9531 | 0.9683 | 0.9988 | 0.0146 |

| RNN | 0.9615 | 0.9839 | 0.9531 | 0.9683 | 0.9918 | 0.0112 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.9519 | 1.0000 | 0.9219 | 0.9594 | 0.9914 | 0.0515 |

| KNN | 0.9519 | 0.9836 | 0.9375 | 0.9600 | 0.9633 | 0.0190 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.9423 | 0.9677 | 0.9375 | 0.9524 | 0.9863 | 0.0146 |

| AdaBoost-DBN | 0.9231 | 0.9828 | 0.8906 | 0.9344 | 0.9863 | 9.2428 |

| LSTM | 0.8654 | 0.9464 | 0.8281 | 0.8833 | 0.9512 | 0.0118 |

| GRU | 0.8365 | 0.9273 | 0.7969 | 0.8571 | 0.9305 | 0.0124 |

| Datasets | Authors | Outliers | Missing Values | Model | Precision | Accuracy | Recall | F1 score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | [46] | IQR | Attribute Mean | AB + XB | -- | -- | 0.7900 | -- |

| Dataset 2 | [48] | – | – | GBM | - | - | 0.8700 | -- |

| [81] | -- | -- | DA | -- | 0.7400 | 0.7200 | -- | |

| [82] | - | - | ANN | - | 0.7600 | 0.5300 | – | |

| [83] | ESD | k-NN | HM-BagMoov | - | 0.8600 | 0.8500 | 0.7900 | |

| [39] | IQR | Class wise median | QML | 0.7400 | 0.8600 | 0.8500 | 0.7900 | |

| [84] | – | NB | RF | 0.8100 | 0.8700 | 0.8500 | 0.8300 | |

| [85] | – | – | k-NN | 0.8700 | 0.8800 | 0.9000 | 0.8800 | |

| [59] | Group Median | Median | RF | – | 0.9300 | 0.7970 | - | |

| [86] | -- | -- | RF | 0.9400 | 0.9400 | 0.8800 | 0.9100 | |

| [39] | IQR | Class wise median | DL | 0.9000 | 0.9500 | 0.9500 | 0.9300 | |

| Our Study | IQR | ADASYN | RF | 0.9781 | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | |

| Our Study | IQR | ADASYN | k-NN | 0.9781 | 0.9850 | 0.9781 | 0.9781 | |

| Our Study | IQR | ADASYN | DT | 0.9716 | 0.9900 | 1.0000 | 0.9856 | |

| Dataset 3 | [77] | -- | Excluded | NN | -- | 0.8240 | 0.3781 | -- |

| Dataset 4 | Our Study | IQR | Clustering | AdaBoost | 0.4317 | 0.6973 | 0.5122 | 0.4314 |

| Our Study | IQR | Clustering | LR | 0.3067 | 0.7249 | 0.7731 | 0.4392 | |

| Dataset 5 | [78] | -- | Ignoring Tuple | RF | 0.9740 | 0.9740 | 0.9740 | 0.9740 |

| Our Study | IQR | -- | RF | 1.0000 | 0.9904 | 0.9844 | 0.9921 | |

| Our Study | IQR | -- | DT | 1.0000 | 0.9904 | 0.9844 | 0.9921 | |

| Our Study | IQR | -- | AdaBoost | 1.0000 | 0.9904 | 0.9844 | 0.9921 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).