Introduction

Life depends on the integrity of biological barriers, beginning with the cell membranes that separate the human body from the outside environment and the barriers that separate tissues and organs.

Homeostasis of biological barriers is of utmost importance as their disruption was demonstrated in many diseases, including metabolic disorders and severe mental illness (SMI). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a transcription factor abundantly expressed at the gut and blood-brain barrier (BBB), is the master regulator of both tight junctions (TJs) and cellular senescence, thus controlling barrier permeability [

1,

2]. Conversely, dysfunctional AhR allows gut microbes to migrate through the paracellular spaces, accessing the systemic circulation from where they can reach many tissues, including the brain. Dysfunctional TJs and premature cellular senescence were demonstrated in patients with SMI and obesity, implicating AhR in these pathologies [

3,

4,

5]. Indeed, patients with SCZ are known to live 15-20 years shorter compared to the general population and exhibit a more porous blood-brain barrier (BBB).

Mitochondria express mitochondrial AhR (mAhR), suggesting that aberrant activation of this receptor may contribute to eliminating healthy organelles, a phenomenon documented in both SCZ and metabolic syndrome.

The second law of thermodynamics postulates that entropy, a measure of disorder or randomness in a system, applies to both inanimate and animate matter. This article surmises that entropy can detect cellular senescence before microorganismal migration outside the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Shortened telomeres, mitochondrial loss or dysfunction, and microbial translocation markers, such as LPS binding protein (LBP) and CD14, may be utilized to screen for the early signs of SMI and dysmetabolism. Indeed, entropy-driven protein translocation has been demonstrated in bacteria, while mitochondrial dysfunction was shown to precede cellular senescence [

6,

7].

The host immune system responds to translocated bacteria and/ or their molecules by inflammation, likely engendering the clinical picture of major neuropsychiatric syndromes and dysmetabolism. In addition, dysfunctional AhR can lead to premature molecular aging in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), further increasing microbial translocation. Moreover, impaired AhR may respond aberrantly to microbial metabolites, such as tryptophan derivatives, shifting the catabolism of this amino acid toward kynurenine and quinolinic acid both associated with SCZ, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), major depressive disorder (MDD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicide [

8,

9]. Interestingly, psychological stress may increase microbial translocation by activating indoleamine dioxygenase (IDO), an essential enzyme of tryptophan catabolism known for promoting immunological tolerance. Furthermore, microbe-activated AhR and the subsequent premature cellular senescence drive lipid peroxidation, plasmalogen depletion, and toxic ceramide formation, hastening neuronal apoptosis and obesity.

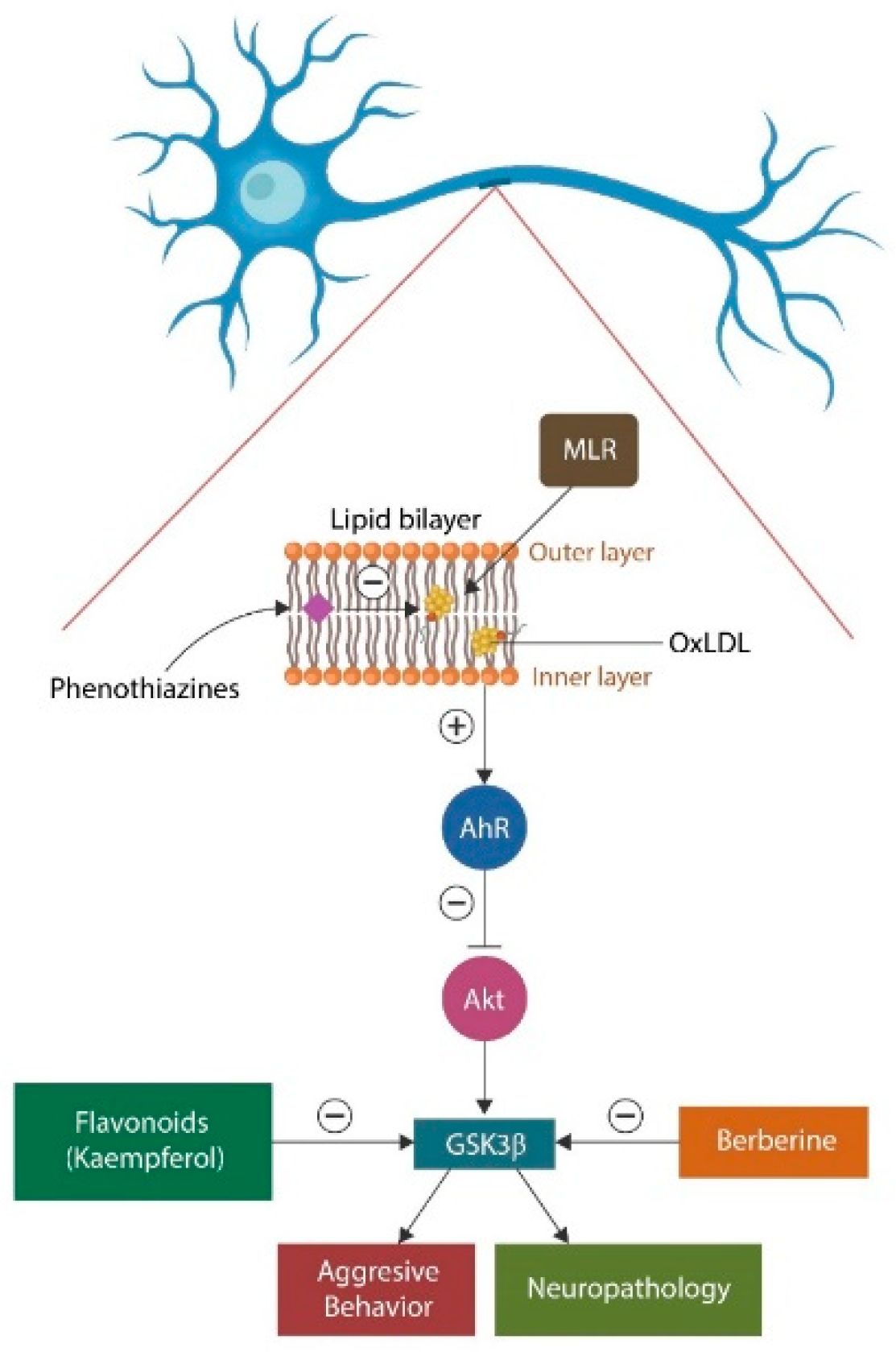

Membrane lipid replacement (MLR) and plasmalogen replacement therapy (PRT) are believed to gradually remove oxidized phospholipids from plasma and mitochondrial membranes, replacing them with healthy and natural phospholipids, thus, preventing neuropathology and dysmetabolism (

Figure 1). Electric, magnetic, sound or ultrasonic stimulation of Vagus nerve and/or spleen may further lower the permeability of biological membranes and microbial translocation.

This review summarizes what is known about biophysical approaches in healing neuropathology and metabolic syndrome. It emphasizes entropy as a biomarker of severe mental illness and metabolic syndrome.

Entropy in biological systems quick reminder

In 1944, Erwin Schrödinger wrote “What is Life,” one of the most influential books of the 20th century. In it, he attempted to apply the second law of thermodynamics to the living matter. In this endeavor, Schrödinger encountered difficulties in reconciling entropy with biological systems. In physics, entropy drives disorder in a system and represents a measure of randomness or uncertainty. Reverting disorder to order requires energy from outside the observed system [

10].

Unlike inanimate matter, living organisms produce energy via glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), which can temporarily reverse entropy and enable the system to thrive.

Schrödinger’s insistence that entropy applies to living matter was frustrating, as organisms appear to restore order by generating energy in mitochondria. In doing so, the mitochondrion must import nutrients from the environment, increasing the entropy of its surroundings. Therefore, applying the second law of thermodynamics to biology is incomplete because it requires the existence of an orderly subsystem within an entropic one. In other words, to validate Schrödinger’s hypothesis, nature would need a system of “order” built into “disorder”. Aware of this contradiction, Schrödinger suggested that living matter may follow laws of physics that are yet unknown.

In neuropsychiatry, entropy is used primarily to study pathological states of consciousness. For example, several studies suggest that SCZ and MDD are disorders of consciousness, a state of being that requires crosstalk and coherence among distant brain areas [

11,

12].

Mitochondria contain a unique microbe-like double membrane structure, highlighting its bacterial origin. The membrane comprises an inner and outer leaflet, an intermembrane space, and a matrix containing mitochondrial enzymes, ribosomes, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). The inner membrane harbors the electron transport enzymes driving OXPHOS, a subsystem that may oppose entropy.

Like plasma membranes, the mitochondrial membrane contains an asymmetric lipid bilayer comprised of phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE), cardiolipin (CL), and phosphatidylcholine (PC). CL is a unique lipid found primarily in the mitochondrial inner membrane that is crucial for maintaining the inner membrane fluidity and the transmembrane potential. In the CNS, CL is found in neurons and glial cells, where it maintains energy homeostasis and drives apoptosis when the cell is damaged beyond repair. Interestingly, anti-cardiolipin antibodies were documented in SCZ, while commensal gut flora, including

Muribaculum intestinale, produces CL, suggesting that host antibodies may be directed against the product of this microbe (when translocated) and not the mitochondrion itself [

13].

Mitochondria contain mAhR, which the oxidized lipids can aberrantly activate, causing organelle demise. This generates excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can lead to membrane damage, leakage of protons across the inner membrane, impaired ATP production, and cell death by apoptosis. For this reason, AhR and mAhR aberrant activation may be entropy drivers. For example, oxidized lipids activate mAhR, ultimately disinhibiting glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), a known pathogenetic mechanism of SMI [

14](

Figure 1).

Cellular and mitochondrial membranes consist of asymmetric lipid bilayers in which each leaflet contains a different lipidome. For example, sphingomyelin is much higher in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, whereas PE and PS are predominantly located in the inner leaflet. This asymmetry of membrane bilayers drives the physiological properties of cell membranes and their functional characteristics. For example, the asymmetric distribution of membrane lipids plays a vital role in signal transduction, temperature adaptation, endocytosis, apoptosis, and other critical cellular functions [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Conversely, loss of membrane asymmetry comprises a primary entropy driver, indicating a marker value for prodromal SMI and dysmetabolism.

Mitochondrial Lipidomics

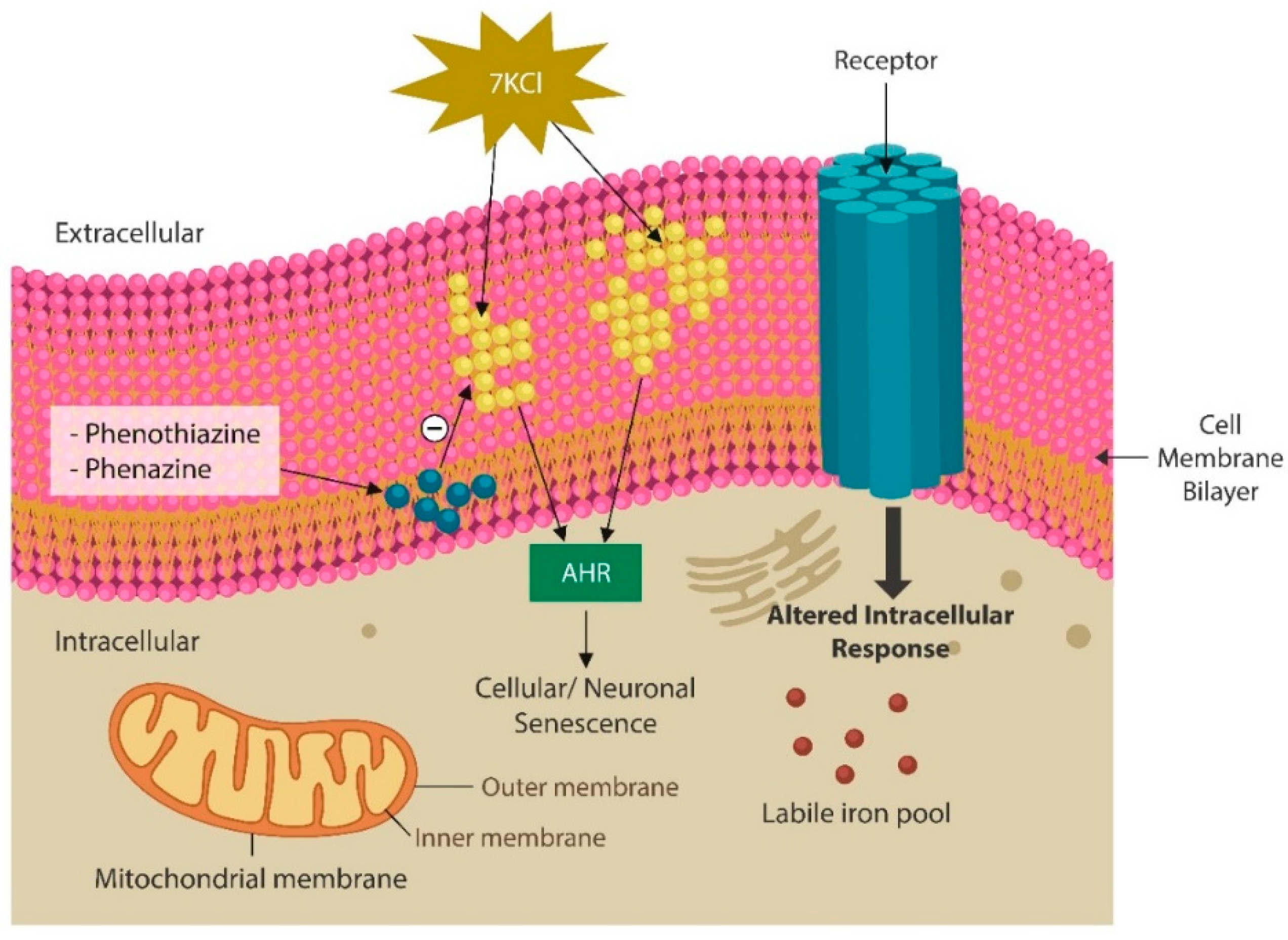

Cellular and mitochondrial lipid bilayer is susceptible to oxidation that can trigger cellular senescence, which may reflect a defense mechanism against ferroptosis [

26,

27]. Indeed, senescent cells upregulate intracellular iron, increasing the risk of ferroptosis, a programmed cell death triggered by lipid peroxidation. Indeed, peroxidation-disrupted neuronal membranes can alter the biophysical properties of surface receptors, disrupting neurotransmission (

Figure 2).

Oxidized membrane lipids, especially sphingolipids, have been directly correlated with the vulnerability to mental illness and metabolic syndrome, suggesting that ferroptosis may play a significant role in these conditions [

28,

29]. Together, this emphasizes once again the role of dysfunctional lipidome in neuropsychiatric disorders and its association with obesity/metabolic syndrome. Indeed, increased ceramide and reduced mitochondria have been documented in SCZ and insulin resistance, linking neuropathology to dysmetabolism [

30,

31]. Since ceramide is known for tagging defective mitochondria for mitophagy, it has been hypothesized that excess ceramide may contribute to the aberrant elimination of healthy mitochondria [

32]. Moreover, ceramide has been implicated in neuronophagia, an autophagic process in which microglia engulfs and digests intact neurons [

33]. This is significant as it can explain the gray and white matter volume loss in both SCZ and metabolic syndrome. In addition, this may explain why most patients with SCZ exhibit low levels of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and high ceramide in the white matter [

34]. Moreover, these findings suggest that correcting membrane lipidomes via MLR and PRT could ameliorate SCZ outcomes.

Ceramides are cell membrane phospholipids (composed of sphingosine and fatty acids) that play a key role in many cellular events, including growth, cell cycle, migration, autophagy, and response to stressors [

35]

Under physiological circumstances, ceramides are obtained from three sources: the diet, de novo synthesis in human tissues, and production by gut commensal flora, such as

Bacteroidetes spp. Along this line, the oral cavity

Bacteroidetes spp., more abundant in patients with SCZ than healthy controls, emphasize the likely origin of ceramide in this disorder [

36]. Moreover, several studies have shown that inflammation can convert ceramide into a toxin, leading to neuropathology, likely linking this lipid to the neuroinflammation demonstrated in SMI [

37].

Novel preclinical studies have shown that gut microbes can metabolize dietary PC into a toxin, trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a biomolecule implicated in obesity, atherosclerosis, and SCZ [

38]. This is important not only for explaining the lower levels of PC in SCZ but also the high prevalence of coronary artery disease in people with this disorder [

39]. Indeed, proinflammatory cytokines and inflammation likely account for the presence of TMAO in SCZ and metabolism disorders. Indeed, earlier studies have shown that inflammation drives the formation of toxic ceramide species, resulting in CNS pathology, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress [

39,

40].

Plasmalogens are a class of cell membrane glycerophospholipids with powerful antioxidant properties, including the ability to protect the membrane bilayer from peroxidation, a pathology documented in SCZ, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and metabolic syndrome [

41]. Asymmetrically displayed glycerophospholipids help maintain the biophysical properties of neuronal membranes, including their shape, fluidity, and thickness, and stabilize membrane proteins, including cell surface receptors, facilitating neurotransmission.

Phenazines and Phenothiazines

Antipsychotic drugs with antioxidant properties, such as phenothiazines, were demonstrated to ingress the lipid bilayers of cellular and mitochondrial membranes, repairing the lipids [

42,

43] (Figure2).

Reduced phospholipids in plasma membranes and platelets of patients with SCZ, mood disorders, and dysmetabolism are considered biomarkers of SMI and metabolic syndrome [

44,

45,

46].

Naturally occurring phenazines, a class of phenothiazines produced by the marine and terrestrial microorganisms as well as by some gut microbes, can also act on neuronal membranes, likely comprising an inbuilt antipsychotic system, akin to the analgesic endogenous opioids. In addition, these agents exert antimicrobial, antiparasitic, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities and are currently in clinical trials for these pathologies [

42]. At present, there are over 100 natural phenazines and about 6000 synthetic derivatives with antioxidant properties that can ingress cell membranes, protecting the lipid bilayer against peroxidation [

42]. Moreover, there are important new phenothiazines with strong antioxidant properties, that have been developed for cancer treatment, such as azaphenothiazines, that can be utilized in SMI along with PRT or MLR (

Table 1).

Cellular senescence and microbial translocation

SMI is characterized by accelerated aging, shorter lifespan, decreased telomere length, and early onset of age-related diseases, indicating the involvement of cellular senescence, a program driven by AhR. Senescent cells arrest proliferation, rewire their metabolism to protect against carcinogens and other endogenous or exogenous toxicants, and release a toxic secretome known as senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) that can spread senescence to the neighboring healthy cells. Senescent IECs disrupt the gut barrier, leading to increased microbial translocation, and systemic inflammation [

47]. Indeed, the movement of microbes across the intestinal barrier, can promote inflammation, upregulate the levels of toxic ceramide, and alter the composition of gut commensals [

48].

Mitochondrial Lipidome and Rapid EEG Frequences

Premature cellular senescence can occur in response to mitochondrial damage, impaired OXPHOS, and production of excessive ROS [

49]. Reduced mitochondrial number in neurons have been associated with the loss of EEG gamma waves (30-100Hz), frequences associated with cognition and higher intellectual functions [

50].

The role of oscillations and vibrations in nature has been appreciated for thousands of years. In ancient Greece, Pythagoras and his followers thought that celestial bodies vibrated in a musical rhythm. Nikola Tesla envisioned a universe governed by oscillatory frequencies, while in our time, two separate groups detected Universe-emitted acoustic oscillations [

51]. Moreover, an Italian study found that 432 Hz tuned music can decrease heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate compared to other frequencies [

52]. Another recent study found that music can alter entropy, suggesting that the type and genre of musical compositions can induce measurable entropy changes [

52]. Indeed, coherent sound vibrations of musical frequences were found to ameliorate hemodynamic, neurological, and musculoskeletal symptoms, further emphasizing the healing role of oscillations [

53].

Together this data show that the Newtonian model of current medical thinking may have limitations as the human body is more than the sum of its components therefore, a quantum paradigm may be more adequate for explaining the effects of gamma frequences on entropy. For example, a novel paradigm conceptualizes human beings as networks of energy fields that are in harmony with physical and biological systems [

54]. Indeed, at the neuronal level, oscillations are a prerequisite for “synchronization”, bringing distant areas of the brain in harmony with each other, a phenomenon believed to enhance consciousness [

55].

Several sound and light frequences were demonstrated to increase empathy and compassion, suggesting interference with the function of the anterior insular cortex (AIC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), brain areas that harbor social intelligence [

56]. In addition, certain oscillatory frequences were found to improve the overall health and wellbeing even in the absence of music, suggesting that the frequency itself rather than the delivering vehicle is beneficial [

53]. Along this line, another study showed measurable improvement in depression and anxiety in college students who exercised twice weekly using a whole-body vibration platform [

57].

Interoceptive Awareness and Oscillations

The synchronization of oscillatory brain activity is thought to drive self -awareness, while desynchronization, inhibition of inter-regional signaling occurs in general anesthesia, further linking communication between brain areas to consciousness [

58,

59,

60]. In this regard, gamma oscillations connect distant brain regions essential for the body movement, memory, and emotion, highlighting the fact that together several brain regions make these activities possible [

61,

62].

It is believed that gamma waves, drive both interoceptive awareness and cognition, contributing to emotional intelligence, the ability to see things from another person’s perspective [

63,

64]. Moreover, awareness of pain, well-being, or the position of one’s limbs and body parts, represent interoceptive awareness. In psychopathology, including SCZ, anosognosia (lack of insight) is a marker of higher severity of symptoms and frequently a marker of aggressive behaviors [

65].

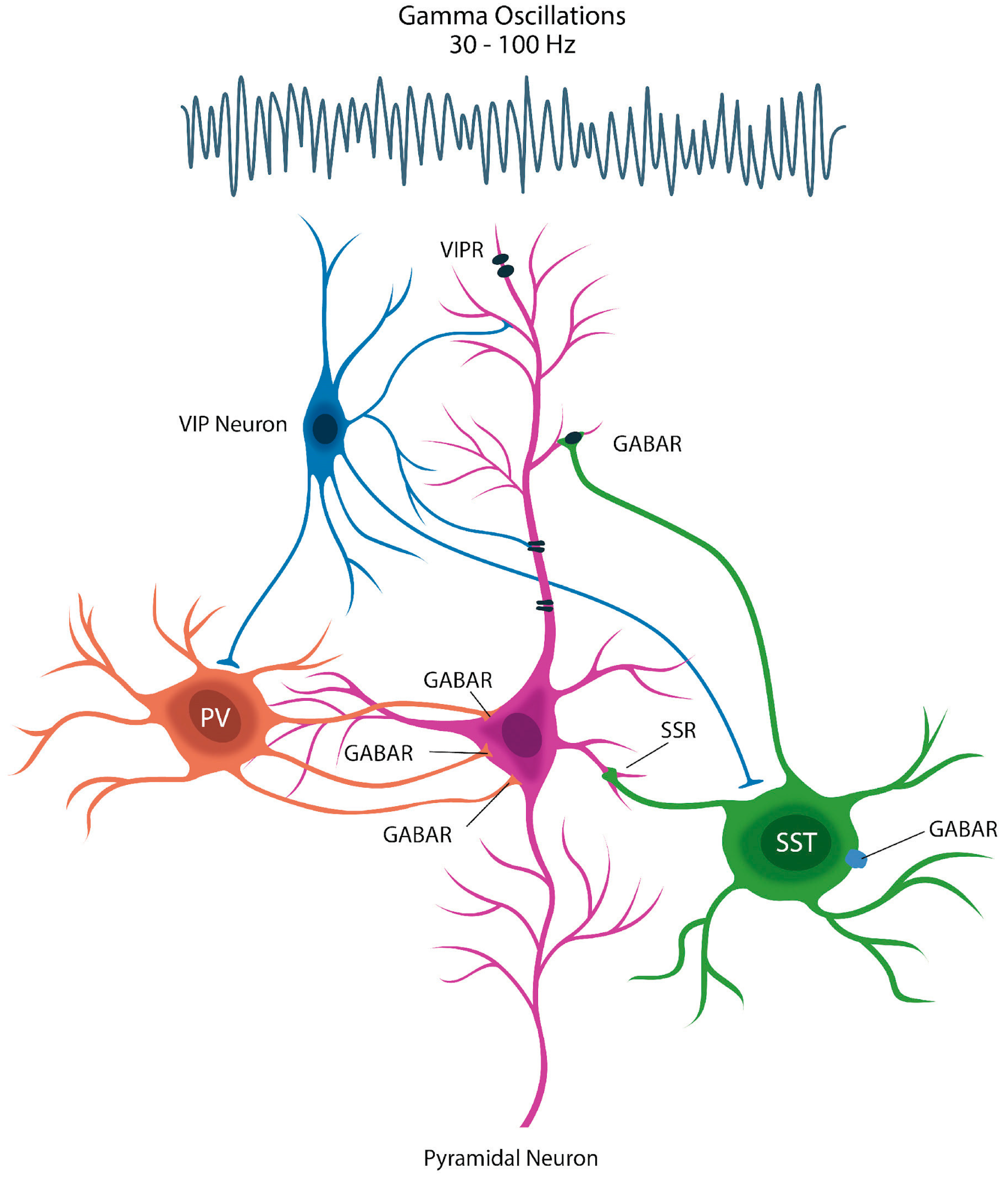

Since SST-secreting γ -aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons are depleted in SCZ, patients with this condition rarely generate gamma waves, likely contributing to anosognosia [

66]. Indeed, loss of gamma oscillations was also documented in AD and PD, linking depletion of these interneurons to poor insight [

67,

68] (

Figure 3).

Desynchronization and Violent Crime

Several EEG studies in the perpetrators of violent crime on death row, found diminished or absent gamma frequencies, highlighting impaired insight [

69]. Electrophysiological changes, low activity in the right prefrontal cortex, and increased striatal activity, reflect cortico-subcortical desynchronization, a likely cause of anosognosia and violent crime [

70,

71]. Altered prefrontal coherence, especially hypo-frontality, may reflect dysfunctional information processing and inability to distinguish reality from imaginary content [

72].

Vaso-intestinal peptide (VIP)-releasing neurons counteract inhibition by inhibiting the inhibitory neurons, an action that leads to the disinhibition of pyramidal cells.

Potential biophysical interventions

It has been said that the 20th century was an era of biochemistry, when drugs were thought to optimally address illnesses. In contrast, the 21st century may be a time of biophysical interventions marked by modulation of physical forces, such as entropy, oscillations, or electromagnetic energy to influence various cellular molecular pathways. In addition, the 20th century was a time of specializing and overspecializing in most fields, learning more and more about less and less, a form of acquiring knowledge by overemphasizing the details, often at the expence of the whole. The 21st century appears to restore the Renaissance concept of synchronization of biological and physical realms, focusing on natural healing, restauration, and repair.

MLR and PRT

PRT and MLR aim at restoring the physiological levels and saturation states of membrane lipids in cell and mitochondrial membranes via natural lipids combined with antioxidants. Altered membrane lipids and oxidation states have been observed in several conditions, including normal aging, SCZ, chronic inflammation, and other neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders.

PRT and MLR can replace and restore functional membrane lipids that are necessary for the adequate separation of body compartments. Natural glycerophospholipids and plasminogen are administered by mouth and in time, they remove and replace toxic lipids and other detrimental hydrophobic molecules, reducing symptom severities in many conditions. This was recently demonstrated in chemically exposed veterans with Gulph War Illness (GWI) treated with MLR [

65].

Other properties of PRT and MLR could be significant for treating SMIs. For example, plasmalogens may function as endogenous statins, lowering cholesterol synthesis, suggesting the existence of an equilibrium between membrane lipid species [

73]. Since plasmalogens are natural compounds devoid of statin side effects (hepatotoxicity, and diabetes mellitus), they are preferable in psychiatric patients in which regular statins were associated with aggressive behavior [

74]. A recent study determined the optimal oral dose of PRT as being 900 to 3,600 mg/day over a 4-month period. The authors of this study noted improved cognition and mobility in patients with neurocognitive disorders after about 120 days of PRT in the above doses [

75].

Like PRT, MLR replaces damaged membrane lipids in cells via oral intake of natural, unoxidized membrane lipid supplements. The purpose is to replace oxidized lipids in cellular membranes with natural, unoxidized glycerophospholipids and remove oxidized lipid species and other toxic molecules. MLR has shown efficacy in various conditions involving loss of mitochondrial number and function as well as damage to plasma membranes [

43].

MLR restores the physiological function of plasma membranes throughout the body, including the gut barrier and BBB. It lowers the permeability of epithelial and endothelial barriers, thus averting microbial migration and microbial translocation disorders.

Viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, damage cell membranes as they ingress the intracellular compartment to replicate. Damaged membranes externalize PS, a universal signal attracting phagocytes to eliminate damaged cell. SARS-CoV-2-induced cellular senescence upregulates cytosolic iron, predisposing patients to excess lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis [

76].

Ferroptosis is an iron-induced form of programmed cell death caused by the intracellular accumulation of this biometal in the absence of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)[

77], an enzyme involved in lipid repair. Oxidized lipids can act as foreign molecules and activate the host pattern recognition receptors (PRR), triggering chronic inflammation, neuropathic pain, depression, and neurodegeneration [

77].

Rescue from ferroptosis can be achieved by lowering intracellular iron, increasing GPX4, or replacing the oxidized lipids in cell membranes. Several studies have shown that the SARS-CoV-2 virus upregulates intracellular iron by hijacking host endo-lysosomal system, thus, disrupting ferritin autophagy.

Repair of membranes using MLR has been shown to reduce neuropathic pain, chronic inflammation, and other symptoms as well as enhance mitochondrial dynamics, including fission that upregulates the overall mitochondrial numbers [

43].

Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis have been associated with several conditions, including myalgic encephalomyelitis /chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), GWI, chronic pain, and neuropsychiatric disorders. Ferroptosis-disintegrating cells release alarmins, such as the high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), known for disrupting the intestinal barrier and BBB [

78]. Alarmins trigger inflammation in response to intracellular molecules spilled into the extracellular compartment. In MLR, the natural membrane supplementation with glycerophospholipids was demonstrated to safely restore the homeostasis of biological barriers, limiting microbial translocation [

65]. The aim of MLR here is to substitute ferroptosis-driving oxidized lipids with healthy glycerophospholipids and remove oxidized, toxic membrane lipids.

Oxidized membrane lipids can also induce toxicity by aberrantly activating AhR that in return inhibits Akt, activating GSK3β. Overactive GSK3β has been documented in various neuropsychiatric conditions, especially SCZ and bipolar disorder, as well as in violent crime in forensic detainees.

Several antipsychotic drugs, lithium, and the natural compounds berberine and kaempferol, inhibit GSK3β, suggesting that these herbal medicines exert antipsychotic properties, without the adverse effects of conventional psychotropic drugs [

66].

Unlike the antipsychotic drugs that are symptomatic and may not affect outcomes, MLR and PRT likely comprise etiopathogenetic treatments that could correct lipidomic defects in the plasma and mitochondrial membranes of patients with SMI.

Oscillations and Vibrations

Oscillations or vibrations are fundamental properties of matter, including the biological systems [

71,

72]. For example, from yeast to humans cells communicate via oscillations, indicating that this is likely a highly conserved mechanism [

73,

74,

75]. Indeed, it is believed that certain frequencies may be ideal for encoding and transmitting information, suggesting that oscillations may play a role in neurotransmission, functioning in parallel with the synaptic and exocrine/paracrine systems [

76,

77].

How brain oscillatory frequencies relate to information processing in neuronal networks is not entirely clear. However, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated that neurons can function as oscillators, making cognition possible by synchronizing with the same frequency oscillators in other brain regions [

78,

79]. Adaptive resonance theory (ART) and communication through coherence (CTC) are two neurophysiological models which utilize inter-region signaling to explain information processing [

80,

81]. For example, the auditory cortex generates its own spontaneous oscillations in response to the exogenous oscillatory input, synchronizing with the environment [

82].

Synchronized oscillations may engender a body-wide communication platform, connecting structures inside and outside the CNS. For example, GI tract microbes entrain “brain-like” oscillations, suggesting that the gut-brain axis may be driven by this modality [

83]. This is in line with another novel discovery, that oscillations drive the expression of microbial genes, division, cell cycle progression, and antibiotic resistance [

84]. Furthermore, the GI tract microbiota oscillations are driven by metabolism, suggesting that the enteric nervous system (ENS) may function as an oscillatory sensor and direct this information to the CNS [

85].

Auricular Vagal Nerve Stimmulation (aVNS)

Electrical stimulation of auricular transcutaneous vagal nerve is a modality that can alter the functioning of the neural tissue for therapeutic benefits. Vagus nerve, links the brain directly with several visceral organs, providing a bridge to the GI tract.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is an invasive procedure which requires implantation of a pulse generator and electrodes close to the nerve , usually cervical vagus. As auricular nerve travels superficially and projects to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) where the vagus nerve also reaches, this method could yield results comparable to those of VNS without being invasive [

86,

87].

Aside from its central role of increasing norepinephrine, endorphines, and serotonin, VNS was shown to optimize the permeability of gut barrier, averting microbial translocation [

88]. This is significant as migration of commensal flora (or its components) outside the GI tract is a hallmark of SMI. For this reason, VNS should be used more often as an adjunct to other psychiatric treatments.

Gamma Band Entrainment

Gamma oscillations on EEG have been involved in higher neural functions, including working memory, attention, and likely consciousness [

89]. Gamma waves are generated by the GABA interneurons secreting SST, cells that are absent or disrupted in SCZ and MDD [

90]. Other studies have associated loss of gamma rhythm with aggressive behaviors in forensic psychiatric patients.

The question asked more and more is can we induce gamma waves in a schizophrenic brain to lower psychotic symptoms? Most researchers and clinicians believe that gamma band can be elicited by exposing the patient to this rhythm by various brain stimulatory techniques, including flickering light stimulation (FLS) or exposure to 40 Hz sounds [

91].

Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy (PEMF)

Magnetotherapy can be static or pulsed and is produced by the electric current flowing through a coil, generating an electromagnetic field. Exposure to magnets is an old strategy which has been revisited as we learn more about physics interacting with human biological processes.

A recent large study, 8-weeks PEMF therapy in patients with treatment-resistant depression emphasized the beneficial role of this modality as an augmentation treatment to pharmacotherapy.

PEMF has been used in several conditions, including chronic pain, wound healing, postoperative pain, and depression.

Red Light Therapy (RLT)

RLT has been used in various pathologies, including SCZ and metabolic disorders in which it is neuroprotective, improves mitochondrial function, mood, and cognition. As higher number of mitochondria can be generated by fission, it has been suggested that fission-inducing modalities could benefit individuals with SCZ.

It is believed that RLT lowers inflammation and reduces oxidative stress. In obesity, RLT promotes lipolysis, lowers the adipocyte size, and enhances musculoskeletal system circulation thus, lowering insulin resistance.

More studies are needed to clarify the role of RLT in SCZ and dysmetabolism, especially on mitochondrial upregulation.

Other Biochemical Modalities

Several noninvasive stimulatory techniques, such as low-level laser therapy (LLLT), transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), may enhance the gamma band synchronization, improving illness insight [

92,

93,

94]. Indeed, a study found that a 40 Hz auditory steady-state response (ASSR), stimulated the brain to generate gamma waves, opening novel therapeutic avenues for anosognosia and negative symptoms of SCZ [

95,

96]. In addition, as SST has been implicated in the CNS synchronization and brain plasticity, loss of this hormone may enhance the negative and cognitive symptoms in SCZ [

97]. Aging downregulates SST and upregulates the non-pituitary growth hormone (npGH), inducing premature neuronal senescence and lowering the gamma band [

98]. Since SST-generating GABAergic interneurons are depleted in SCZ, stimulation at 40 Hz may entrain a similar frequency in the cortex [

99,

100].

Conclusion

Both medicated and psychotropic naïve patients with SMI exhibit higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, suggesting that dysmetabolism is an inherent component of psychopathology and not a different entity.

At the cellular level, functional, energy-generating, mitochondria likely delay entropy in biological systems, indicating that measuring mitochondrial randomness or disorder may be an early identifier of SMI and metabolic syndrome. Indeed, aging individuals, patients with SCZ, and those suffering from metabolic syndrome exhibit reduced number of mitochondria, premature aging and dysfunctional biological barriers. Reduced mitochondrial number slows down the general metabolism, predisposing to weight gain.

At the molecular level, aberrant AhR and mAhR activation by the translocated microbes and/or their metabolites, triggers cellular senescence and TJ disruption, contributing to microorganismal migration from the gut lumen into the systemic circulation.

In summary, reduced mitochondrial number lowers body metabolism, predisposing to obesity and SMI. Conversely, early detection of mitochondrial depletion and restoration of organelle number and function by various biophysical modalities may ameliorate both neuropsychiatric and metabolic dysfunction.

References

- Yu M, Wang Q, Ma Y, Li L, Yu K, Zhang Z, Chen G, Li X, Xiao W, Xu P, Yang H. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation Modulates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function by Maintaining Tight Junction Integrity. Int J Biol Sci. 2018 Jan 11;14(1):69-77. [CrossRef]

- Nacarino-Palma A, Rico-Leo EM, Campisi J, Ramanathan A, González-Rico FJ, Rejano-Gordillo CM, Ordiales-Talavero A, Merino JM, Fernández-Salguero PM. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor blocks aging-induced senescence in the liver and fibroblast cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2022 May 26;14(10):4281-4304. [CrossRef]

- Greene C, Hanley N, Campbell M. Blood-brain barrier associated tight junction disruption is a hallmark feature of major psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2020 Nov 2;10(1):373. [CrossRef]

- Solana C, Pereira D, Tarazona R. Early Senescence and Leukocyte Telomere Shortening in SCHIZOPHRENIA: A Role for Cytomegalovirus Infection? Brain Sci. 2018 Oct 18;8(10):188. [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou E, Gaughran F, Smith S. Schizophrenia as segmental progeria. J R Soc Med. 2011 Nov;104(11):475-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatullo M. Entropy Meets Physiology: Should We Translate Aging as Disorder? Stem Cells. 2024 Feb 8;42(2):91-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halladin DK, Ortega FE, Ng KM, Footer MJ, Mitić NS, Malkov SN, Gopinathan A, Huang KC, Theriot JA. Entropy-driven translocation of disordered proteins through the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall. Nat Microbiol. 2021 Aug;6(8):1055-1065. [CrossRef]

- Marx W, McGuinness AJ, Rocks T, Ruusunen A, Cleminson J, Walker AJ, Gomes-da-Costa S, Lane M, Sanches M, Diaz AP, Tseng PT, Lin PY, Berk M, Clarke G, O'Neil A, Jacka F, Stubbs B, Carvalho AF, Quevedo J, Soares JC, Fernandes BS. The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of 101 studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Aug;26(8):4158-4178. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Kai ; Yuan, Yanling ; Xie, Qinglian ; Dong, Zaiquan. Relationship between human oral microbiome dysbiosis and neuropsychiatric diseases: An updated overview Behavioural brain research, 2024-08, Vol.471, p.115111, Article 115111.

- Erwin Schrödinger (1944), What Is Life? and Other Scientific Essays. Based on lectures delivered under the auspices of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies at Trinity College, Dublin, in February 1943. Doubleday (1956).

- Venkatasubramanian G. Understanding schizophrenia as a disorder of consciousness: biological correlates and translational implications from quantum theory perspectives. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015 Apr 30;13(1):36-47. [CrossRef]

- Walter J. Consciousness as a multidimensional phenomenon: implications for the assessment of disorders of consciousness. Neurosci Conscious. 2021 Dec 30;2021(2):niab047. [CrossRef]

- Bang S, Shin YH, Ma X, Park SM, Graham DB, Xavier RJ, Clardy J. A Cardiolipin from Muribaculum intestinale Induces Antigen-Specific Cytokine Responses. J Am Chem Soc. 2023 Nov 1;145(43):23422-23426. [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu JM, Zhang X, Rodriguiz RM, Sotnikova TD, Cools MJ, Wetsel WC, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Role of GSK3 beta in behavioral abnormalities induced by serotonin deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Jan 29;105(4):1333-8. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, G.L. The Fluid—Mosaic Model of Membrane Structure: Still relevant to understanding the structure, function and dynamics of biological membranes after more than 40 years. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2014; 1838: 1451–1466.

- Nicolson, G.L.; Ferriera de Matos, G. A brief introduction to some aspects of the Fluid—Mosaic Model of cell membrane structure.

- and its importance in Membrane Lipid Replacement. Membranes 2021; 11: 947.

- Harayama T, Reizman H. Understanding the diversity of membrane lipid composition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018; 19: 281-296.

- Jinling Wang, Xiufu Lin, Ningning Zhao, Guanping Dong, Wei Wu, Ke Huang, Junfen Fu. Effects of Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Pathophysiology of Obesity. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2022, 27(3), 107. [CrossRef]

- Kim JA, Wei Y, Sowers JR. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Circ Res. 2008 Feb 29;102(4):401-14. [CrossRef]

- Masenga SK, Kabwe LS, Chakulya M, Kirabo A. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr 26;24(9):7898. [CrossRef]

- Poljšak B, Milisav I. Decreasing Intracellular Entropy by Increasing Mitochondrial Efficiency and Reducing ROS Formation-The Effect on the Ageing Process and Age-Related Damage. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 7;25(12):6321. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D. Time-Shift Multiscale Entropy Analysis of Physiological Signals. Entropy 2017, 19, 257. [CrossRef]

- Xiang J, Tian C, Niu Y, Yan T, Li D, Cao R, Guo H, Cui X, Cui H, Tan S, Wang B. Abnormal Entropy Modulation of the EEG Signal in Patients With Schizophrenia During the Auditory Paired-Stimulus Paradigm. Front Neuroinform. 2019 Feb 19;13:4. [CrossRef]

- Soliz-Rueda JR, Cuesta-Marti C, O'Mahony SM, Clarke G, Schellekens H, Muguerza B. Gut microbiota and eating behaviour in circadian syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2025 Jan;36(1):15-28. [CrossRef]

- Decker ST, Funai K. Mitochondrial membrane lipids in the regulation of bioenergetic flux. Cell Metab. 2024 Sep 3;36(9):1963-1978. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira MC, Yusupov M, Bogaerts A, Cordeiro RM. Lipid Oxidation: Role of Membrane Phase-Separated Domains. J Chem Inf Model. 2021 Jun 28;61(6):2857-2868. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo C, Zhao F, Tian H, Chen J, Li Q, Yang L, Ping J, Li R, Wang L, Xu Y, Cai Z, Song X. Acid sphingomyelinase/ceramide system in schizophrenia: implications for therapeutic intervention as a potential novel target. Transl Psychiatry. 2022 Jun 23;12(1):260. [CrossRef]

- Adams JM 2nd, Pratipanawatr T, Berria R, Wang E, DeFronzo RA, Sullards MC, Mandarino LJ. Ceramide content is increased in skeletal muscle from obese insulin-resistant humans. Diabetes. 2004 Jan;53(1):25-31. [CrossRef]

- Fizíková I, Dragašek J, Račay P. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Altered Mitochondrial Oxygen, and Energy Metabolism Associated with the Pathogenesis of Schizophrenia. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr 28;24(9):7991. [CrossRef]

- Xia W, Veeragandham P, Cao Y, Xu Y, Rhyne TE, Qian J, Hung CW, Zhao P, Jones Y, Gao H, Liddle C, Yu RT, Downes M, Evans RM, Rydén M, Wabitsch M, Wang Z, Hakozaki H, Schöneberg J, Reilly SM, Huang J, Saltiel AR. Obesity causes mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in white adipocytes due to RalA activation. Nat Metab. 2024 Feb;6(2):273-289. [CrossRef]

- Sentelle RD, Senkal CE, Jiang W, Ponnusamy S, Gencer S, Selvam SP, Ramshesh VK, Peterson YK, Lemasters JJ, Szulc ZM, Bielawski J, Ogretmen B. Ceramide targets autophagosomes to mitochondria and induces lethal mitophagy. Nat Chem Biol. 2012 Oct;8(10):831-8. Erratum in: Nat Chem Biol. 2012 Dec;8(12):1008. [CrossRef]

- Mencarelli C, Martinez-Martinez P. Ceramide function in the brain: when a slight tilt is enough. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013 Jan;70(2):181-203. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz E., Prabakaran S., Whitfield P., Major H., Leweke F. M., Keothe D., et al.. (2008). High troughput lipidomic profiling of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder brain tissue reveals alterations of free fatty acids, phosphatidylcolines and ceramides. J. Proteome Res. 7, 4266–4277. 10.1021/pr800188y.

- Bernal-Vega S, García-Juárez M, Camacho-Morales A. Contribution of ceramides metabolism in psychiatric disorders. J. Neurochem.2023; 164: 708-724.

- Zhu, F., Ju, Y., Wang, W. et al. Metagenome-wide association of gut microbiome features for schizophrenia. Nat Commun 11, 1612 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.L., Heaver, S.L., Waters, J.L. et al. Sphingolipids produced by gut bacteria enter host metabolic pathways, impacting ceramide levels. Nat Commun 11, 2471 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Schugar RC, Shih DM, Warrier M, Helsley RN, Burrows A, Ferguson D, Brown AL, Gromovsky AD, Heine M, Chatterjee A, Li L, Li XS, et al. The TMAO-Producing Enzyme Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 Regulates Obesity and the Beiging of White Adipose Tissue. Cell Rep. 2017 Jun 20;19(12):2451-2461. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.077. Erratum in: Cell Rep. 2017 Jul 5;20(1):279. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Dai M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Generated by the Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Vascular Inflammation: New Insights into Atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2020 Feb 17;2020:4634172. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TT, Kosciolek T, Daly RE, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Swafford A, Knight R, Jeste DV. Gut microbiome in Schizophrenia: Altered functional pathways related to immune modulation and atherosclerotic risk. Brain Behav Immun. 2021 Jan;91:245-256. [CrossRef]

- de la Monte SM. Triangulated mal-signaling in Alzheimer's disease: roles of neurotoxic ceramides, ER stress, and insulin resistance reviewed. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30 Suppl 2(0 2):S231-49. [CrossRef]

- Voronova O, Zhuravkov S, Korotkova E, Artamonov A, Plotnikov E. Antioxidant Properties of New Phenothiazine Derivatives. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Jul 14;11(7):1371. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson GL, Ferreira de Mattos G, Settineri R, Breeding PC. Membrane Lipid Replacement and its role in restoring mitochondrial membrane function and reducing symptoms in aging and age-related clinical conditions. Nature Cell Sci. 2024; 2(4): 238-256.

- Nicolson GL, Breeding PC. Membrane Lipid Replacement with glycerolphospholipids slowly reduces self-reported symptom severities in chemically exposed Gulf War veterans. International Journal of Translational Medicine 2022; 2(2): 164-173.

- Almsherqi ZA. Potential Role of Plasmalogens in the Modulation of Biomembrane Morphology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Jul 21;9:673917. [CrossRef]

- Schooneveldt YL, Paul S, Calkin AC, Meikle PJ. Ether Lipids in Obesity: From Cells to Population Studies. Front Physiol. 2022 Mar 3;13:841278. [CrossRef]

- Thevaranjan N, Puchta A, Schulz C, Naidoo A, Szamosi JC, Verschoor CP, Loukov D, Schenck LP, Jury J, Foley KP, Schertzer JD, et al. Age-Associated Microbial Dysbiosis Promotes Intestinal Permeability, Systemic Inflammation, and Macrophage Dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe. 2017 Apr 12;21(4):455-466.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.002. Erratum in: Cell Host Microbe. 2018 Apr 11;23(4):570. [CrossRef]

- Johnson EL, Heaver SL, Waters JL, Kim BI, Bretin A, Goodman AL, Gewirtz AT, Worgall TS, Ley RE. Sphingolipids produced by gut bacteria enter host metabolic pathways impacting ceramide levels. Nat Commun. 2020 May 18;11(1):2471. [CrossRef]

- Miwa S, Kashyap S, Chini E, von Zglinicki T. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cell senescence and aging. J Clin Invest. 2022 Jul 1;132(13):e158447. [CrossRef]

- .Guan A, Wang S, Huang A, Qiu C, Li Y, Li X, Wang J, Wang Q, Deng B. The role of gamma oscillations in central nervous system diseases: Mechanism and treatment. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022 Jul 29;16:962957. [CrossRef]

- Miller CJ, Nichol RC, Batuski DJ. Acoustic oscillations in the early universe and today. Science. 2001 Jun 22;292(5525):2302-3. Epub 2001 May 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calamassi D, Lucicesare A, Pomponi GP, Bambi S. Music tuned to 432 Hz versus music tuned to 440 Hz for improving sleep in patients with spinal cord injuries: a double-blind cross-over pilot study. Acta Biomed. 2020 Nov 30;91(12-S):e2020008. [CrossRef]

- Bartel L, Mosabbir A. Possible Mechanisms for the Effects of Sound Vibration on Human Health. Healthcare (Basel). 2021 May 18;9(5):597. [CrossRef]

- Beri K. A future perspective for regenerative medicine: understanding the concept of vibrational medicine. Future Sci OA. 2018 Jan 5;4(3):FSO274. [CrossRef]

- Arnulfo G, Wang SH, Myrov V, Toselli B, Hirvonen J, Fato MM, Nobili L, Cardinale F, Rubino A, Zhigalov A, Palva S, Palva JM. Long-range phase synchronization of high-frequency oscillations in human cortex. Nat Commun. 2020 Oct 23;11(1):5363. [CrossRef]

- Wallmark Z, Deblieck C, Iacoboni M. Neurophysiological Effects of Trait Empathy in Music Listening. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018 Apr 6;12:66. [CrossRef]

- Chawla G, Azharuddin M, Ahmad I, Hussain ME. Effect of Whole-body Vibration on Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Quality of Life in College Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Oman Med J. 2022 Jul 31;37(4):e408. [CrossRef]

- Sfera A, Hazan S, Klein C, Zapata-Martin del Campo CM, Sasannia S, Anton JJ, Rahman L, Andronescu CV, Sfera DO, Kozakidis Z, Nicolson GL. Microbial translocation disorders: assigning an etiology to idiopathic illnesses. Applied Microbiology 2023; 3(1): 212-240.

- Jang JE, Park HS, Yoo HJ, Baek IJ, Yoon JE, Ko MS, Kim AR, Kim HS, Park HS, Lee SE, Kim SW, Kim SJ, Leem J, Kang YM, Jung MK, Pack CG, Kim CJ, Sung CO, Lee IK, Park JY, Fernández-Checa JC, Koh EH, Lee KU. Protective role of endogenous plasmalogens against hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2017.

- Leppien E, Mulcahy K, Demler TL, Trigoboff E, Opler L. Effects of Statins and Cholesterol on Patient Aggression: Is There a Connection? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018 Apr 1;15(3-4):24-27.

- Goodenowe DB, Haroon J, Kling MA, Zielinski M, Mahdavi K, Habelhah B, Shtilkind L, Jordan S. Targeted Plasmalogen Supplementation: Effects on Blood Plasmalogens, Oxidative Stress Biomarkers, Cognition, and Mobility in Cognitively Impaired Persons. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Jul 6;10:864842. [CrossRef]

- Wang MP, Joshua B, Jin NY, Du SW, Li C. Ferroptosis in viral infection: the unexplored possibility. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022 Aug;43(8):1905-1915. [CrossRef]

- Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: Death by Lipid Peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 2016 Mar;26(3):165-176. [CrossRef]

- Wen Q, Liu J, Kang R, Zhou B, Tang D. The release and activity of HMGB1 in ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019 Mar 5;510(2):278-283. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson GL, Ash ME. Membrane Lipid Replacement for chronic illnesses, aging and cancer using oral glycerolphospholipid formulations with fructooligosaccharides to restore phospholipid function in cellular membranes, organelles, cells and tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2017 Sep;1859(9 Pt B):1704-1724. [CrossRef]

- Sfera, A.; Imran, H.; Sfera, D.O.; Anton, J.J.; Kozlakidis, Z.; Hazan, S. Novel Insights into Psychosis and Antipsychotic Interventions: From Managing Symptoms to Improving Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5904. [CrossRef]

- Traikapi A, Konstantinou N. Gamma Oscillations in Alzheimer's Disease and Their Potential Therapeutic Role. Front Syst Neurosci. 2021 Dec 13;15:782399. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guerra A, Asci F, D'Onofrio V, Sveva V, Bologna M, Fabbrini G, Berardelli A, Suppa A. Enhancing Gamma Oscillations Restores Primary Motor Cortex Plasticity in Parkinson's Disease. J Neurosci. 2020 Jun 10;40(24):4788-4796. [CrossRef]

- McNally JM, McCarley RW. Gamma band oscillations: a key to understanding schizophrenia symptoms and neural circuit abnormalities. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016 May;29(3):202-10. [CrossRef]

- Pillmann F, Rohde A, Ullrich S, Draba S, Sannemüller U, Marneros A. Violence, criminal behavior, and the EEG: significance of left hemispheric focal abnormalities. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999 Fall;11(4):454-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller CJ, Nichol RC, Batuski DJ. Acoustic oscillations in the early universe and today. Science. 2001 Jun 22;292(5525):2302-3. [CrossRef]

- Noble AE, Machta J, Hastings A. Emergent long-range synchronization of oscillating ecological populations without external forcing described by Ising universality. Nat Commun. 2015 Apr 8;6:6664. [CrossRef]

- Madsen MF, Danø S, Sørensen PG. On the mechanisms of glycolytic oscillations in yeast. FEBS J. 2005 Jun;272(11):2648-60. [CrossRef]

- Weiss E, Kann M, Wang Q. Neuromodulation of Neural Oscillations in Health and Disease. Biology (Basel). 2023 Feb 26;12(3):371. [CrossRef]

- Başar E. Brain oscillations in neuropsychiatric disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013 Sep;15(3):291-300. [CrossRef]

- Chan D, Suk HJ, Jackson B, Milman NP, Stark D, Beach SD, Tsai LH. Induction of specific brain oscillations may restore neural circuits and be used for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Intern Med. 2021 Nov;290(5):993-1009. [CrossRef]

- Siebenhühner F, Palva JM, Palva S. Linking the microarchitecture of neurotransmitter systems to large-scale MEG resting state networks. iScience. 2024 Oct 9;27(11):111111. [CrossRef]

- Stiefel KM, Ermentrout GB. Neurons as oscillators. J Neurophysiol. 2016 Dec 1;116(6):2950-2960. [CrossRef]

- Singer W. Neuronal oscillations: unavoidable and useful? Eur J Neurosci. 2018 Oct;48(7):2389-2398. [CrossRef]

- González J, Cavelli M, Mondino A, Rubido N, Bl Tort A, Torterolo P. Communication Through Coherence by Means of Cross-frequency Coupling. Neuroscience. 2020 Nov 21;449:157-164. [CrossRef]

- Grossberg S. Adaptive Resonance Theory: how a brain learns to consciously attend, learn, and recognize a changing world. Neural Netw. 2013 Jan;37:1-47. [CrossRef]

- Gourévitch B, Martin C, Postal O, Eggermont JJ. Oscillations in the auditory system and their possible role. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020 Jun;113:507-528. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Corral R, Liu J, Prindle A, Süel GM, Garcia-Ojalvo J. Metabolic basis of brain-like electrical signalling in bacterial communities. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2019 Jun 10;374(1774):20180382. [CrossRef]

- Vislova A, Sosa OA, Eppley JM, Romano AE, DeLong EF. Diel Oscillation of Microbial Gene Transcripts Declines With Depth in Oligotrophic Ocean Waters. Front Microbiol. 2019 Sep 24;10:2191. [CrossRef]

- Spencer NJ, Hu H. Enteric nervous system: sensory transduction, neural circuits and gastrointestinal motility. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun;17(6):338-351. [CrossRef]

- Butt MF, Albusoda A, Farmer AD, Aziz Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. J Anat. 2020 Apr;236(4):588-611. [CrossRef]

- Howland RH. Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014 Jun;1(2):64-73. [CrossRef]

- Mogilevski T, Rosella S, Aziz Q, Gibson PR. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation protects against stress-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction in healthy adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022 Oct;34(10):e14382. [CrossRef]

- Panagiotaropoulos TI, Deco G, Kapoor V, Logothetis NK. Neuronal discharges and gamma oscillations explicitly reflect visual consciousness in the lateral prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2012 Jun 7;74(5):924-35. Erratum in: Neuron. 2012 Jun 21;74(6):1139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienel SJ, Fish KN, Lewis DA. The Nature of Prefrontal Cortical GABA Neuron Alterations in Schizophrenia: Markedly Lower Somatostatin and Parvalbumin Gene Expression Without Missing Neurons. Am J Psychiatry. 2023 Jul 1;180(7):495-507. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Duque C, Chan D, Kahn MC, Murdock MH, Tsai LH. Audiovisual gamma stimulation for the treatment of neurodegeneration. J Intern Med. 2024 Feb;295(2):146-170. [CrossRef]

- Calderone A, Cardile D, Gangemi A, De Luca R, Quartarone A, Corallo F, Calabrò RS. Traumatic Brain Injury and Neuromodulation Techniques in Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review. Biomedicines. 2024 Feb 16;12(2):438. [CrossRef]

- Nissim NR, Pham DVH, Poddar T, Blutt E, Hamilton RH. The impact of gamma transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on cognitive and memory processes in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer's disease: A literature review. Brain Stimul. 2023 May-Jun;16(3):748-755. [CrossRef]

- Mueller JK, Grigsby EM, Prevosto V, Petraglia FW 3rd, Rao H, Deng ZD, Peterchev AV, Sommer MA, Egner T, Platt ML, Grill WM. Simultaneous transcranial magnetic stimulation and single-neuron recording in alert non-human primates. Nat Neurosci. 2014 Aug;17(8):1130-6. [CrossRef]

- Woo TU, Spencer K, McCarley RW. Gamma oscillation deficits and the onset and early progression of schizophrenia. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010 May-Jun;18(3):173-89. [CrossRef]

- Roach BJ, Ford JM, Hoffman RE, Mathalon DH. Converging evidence for gamma synchrony deficits in schizophrenia. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;62:163-80. [CrossRef]

- Jahangir M, Zhou JS, Lang B, Wang XP. GABAergic System Dysfunction and Challenges in Schizophrenia Research. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 May 14;9:663854. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.663854. Erratum in: Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Aug 13;9:742519. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramuntell Y, Klimczak P, Coviello S, Perez-Rando M, Nacher J. Effects of Aging on the Structure and Expression of NMDA Receptors of Somatostatin Expressing Neurons in the Mouse Hippocampus. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021 Dec 23;13:782737. [CrossRef]

- Grent-'t-Jong, Tineke et al.40-Hz Auditory Steady-State Responses in Schizophrenia: Toward a Mechanistic Biomarker for Circuit Dysfunctions and Early Detection and Diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry, Volume 94, Issue 7, 550 – 560.

- Parciauskaite V, Voicikas A, Jurkuvenas V, Tarailis P, Kraulaidis M, Pipinis E, Griskova-Bulanova I. 40-Hz auditory steady-state responses and the complex information processing: An exploratory study in healthy young males. PLoS One. 2019 Oct 7;14(10):e0223127. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).