Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

- pH levels

- Dissolved oxygen (DO)

- Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD)

- Heavy metal concentration (Pb, Zn, As, etc.)

- High processing time – Manual classification can take hours or even days, depending on the dataset size.

- Prone to human errors – Data entry mistakes and formula inconsistencies can lead to misclassifications.

- Limited scalability – The method struggles to handle large-scale datasets efficiently.

- Water quality prediction using regression models.

- Anomaly detection in water contamination events.

- Pattern recognition in water parameter fluctuations.

3. Previous concepts

3.1. Water Quality Index (WQI)

- 1-A2: Suitable for human consumption after conventional treatment.

- 3-D2: Suitable for animal drinking purposes.

3.2. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Distance Calculation: The algorithm calculates the distance between the new data point and existing samples using metrics such as:

- Euclidean Distance (for continuous data).

- Manhattan Distance (for multidimensional data).

- b.

- Choosing the Value of K: Determines the number of neighbors to consider. In this study, k = 8 was selected as the optimal value through parameter tuning (Saddiqi et al., 2024).

- c.

- Majority Vote: The algorithm assigns the category that appears most frequently among the k-nearest neighbors [27].

- d.

- Advantages of the KNN Algorithm:

- Simplicity and Flexibility: Easy to implement and interpret, adaptable to various types of data.

- Robustness: Effective for noisy data if the k value is chosen appropriately.

- Versatility: Works with both numerical and categorical datasets [22].

3.3. Cross-Validation

- Data Splitting: The dataset is divided into five equal folds using the KFold method from the scikit-learn library.

- Training and Evaluation: For each iteration:

- The model is trained in four folds and validated on the fifth.

- The coefficient of determination (R²) is calculated to measure model accuracy.

- 3.

- Parameter Optimization: GridSearchCV was used to identify the optimal k value (k = 8), maximizing classification performance.

- 4.

- Overfitting Prevention: This process helps prevent overfitting by ensuring that the model does not rely too heavily on specific subsets of the data

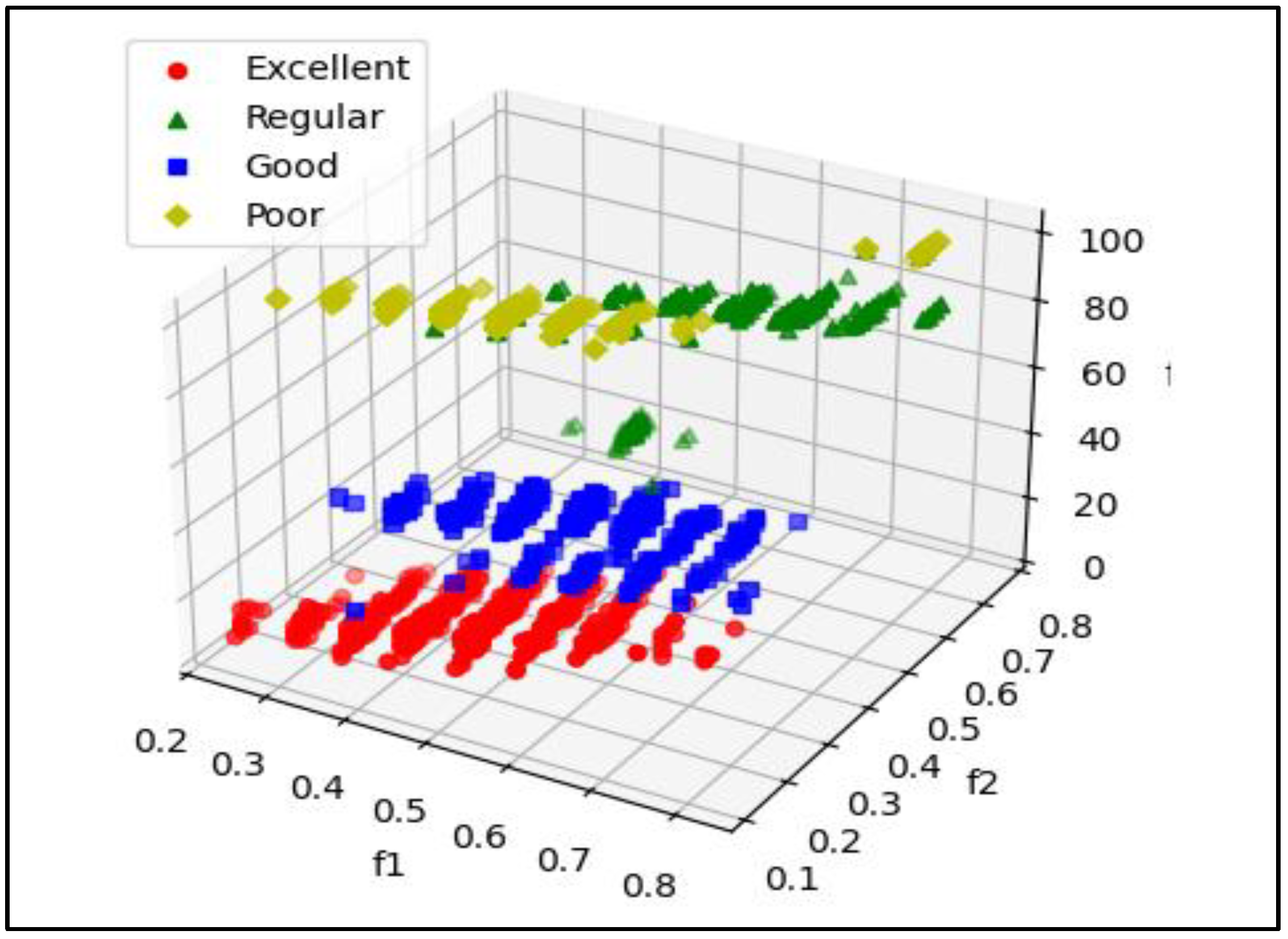

- The horizontal "f1" axis represents a quantitative characteristic or metric, with values ranging from 0 to 1.

- The "f2" axis also measures a characteristic or metric, and its values range from 0 to approximately 0.7.

- The vertical axis represents an outcome or assessment variable, with values ranging from 0 to 100.

- The data are labeled with four different categories:

- Red (Circles): Represents the "Bad" category, with high scores (close to 100) on the vertical axis and located in a particular area of the "f1" and "f2" axes.

- Green (Triangles): Represents the "Excellent" category, with data distributed primarily in the lower part of the graph (low scores on the vertical axis) and concentrated within a specific range of "f1" and "f2".

- Blue (Squares): Represents the "Fair" category, with points mainly in the middle of the graph (vertical axis around 50) and with intermediate values for "f1" and "f2".

- Yellow (Diamonds): Represents the "Good" category, with values distributed primarily in the left quadrant of the graph.

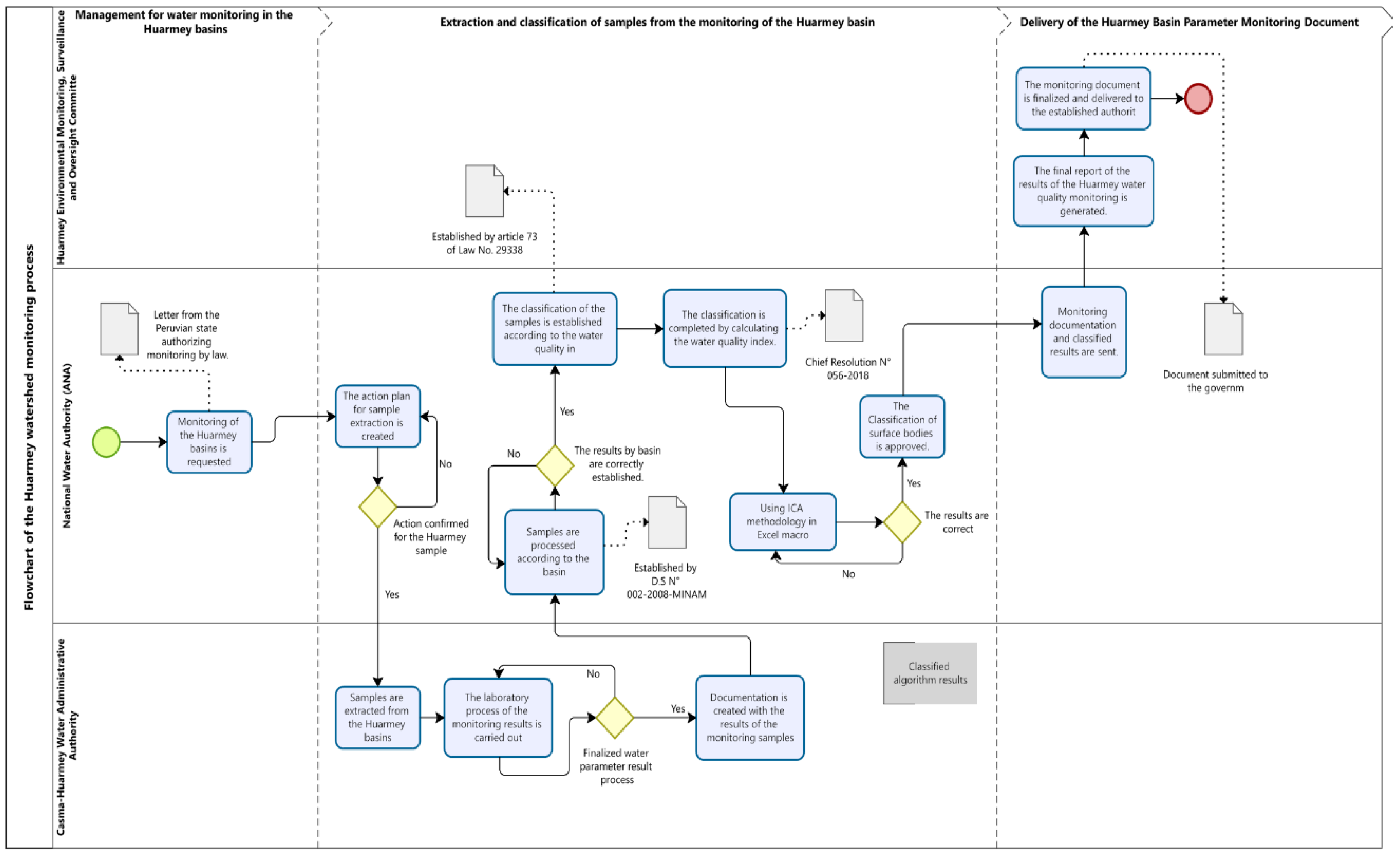

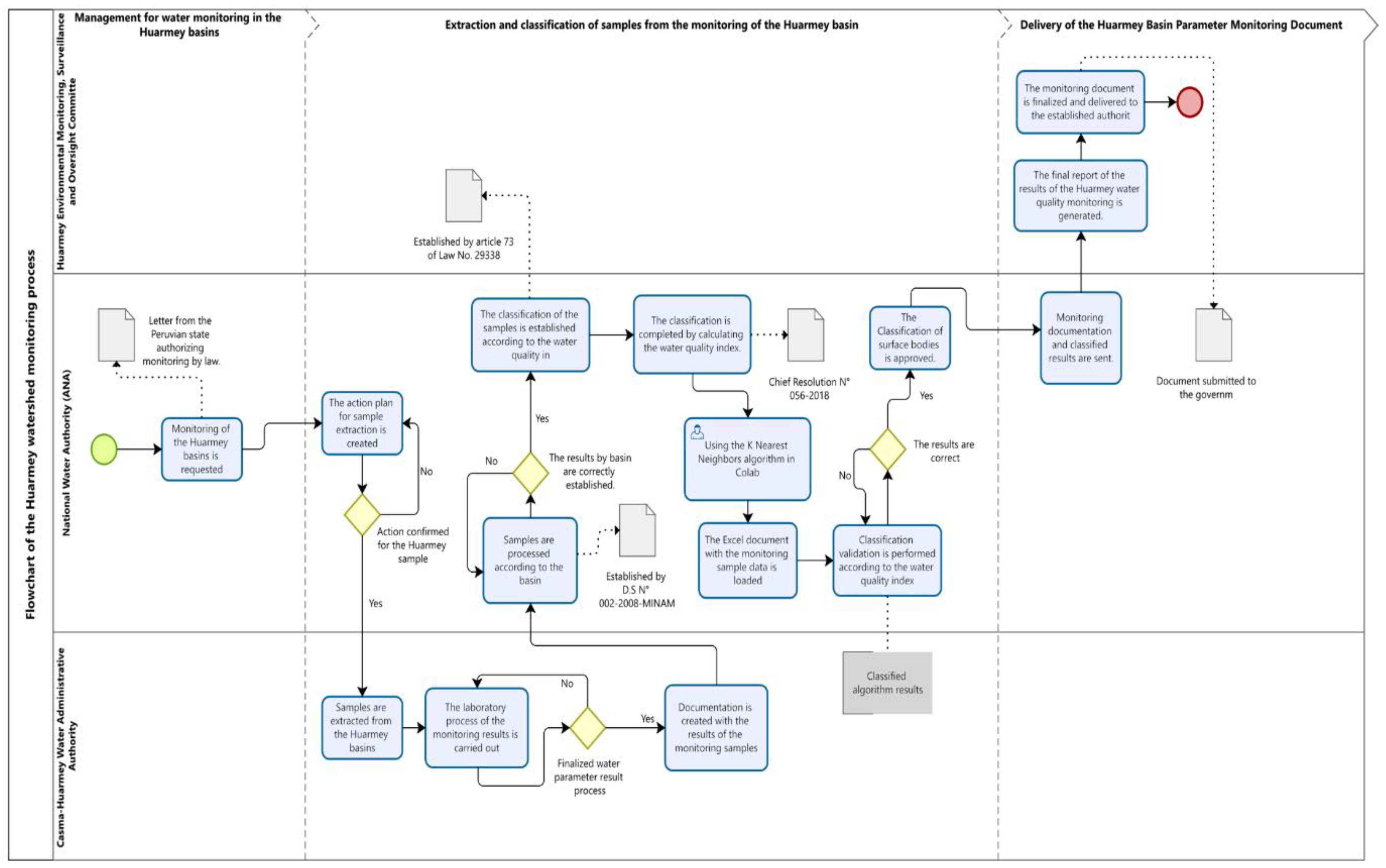

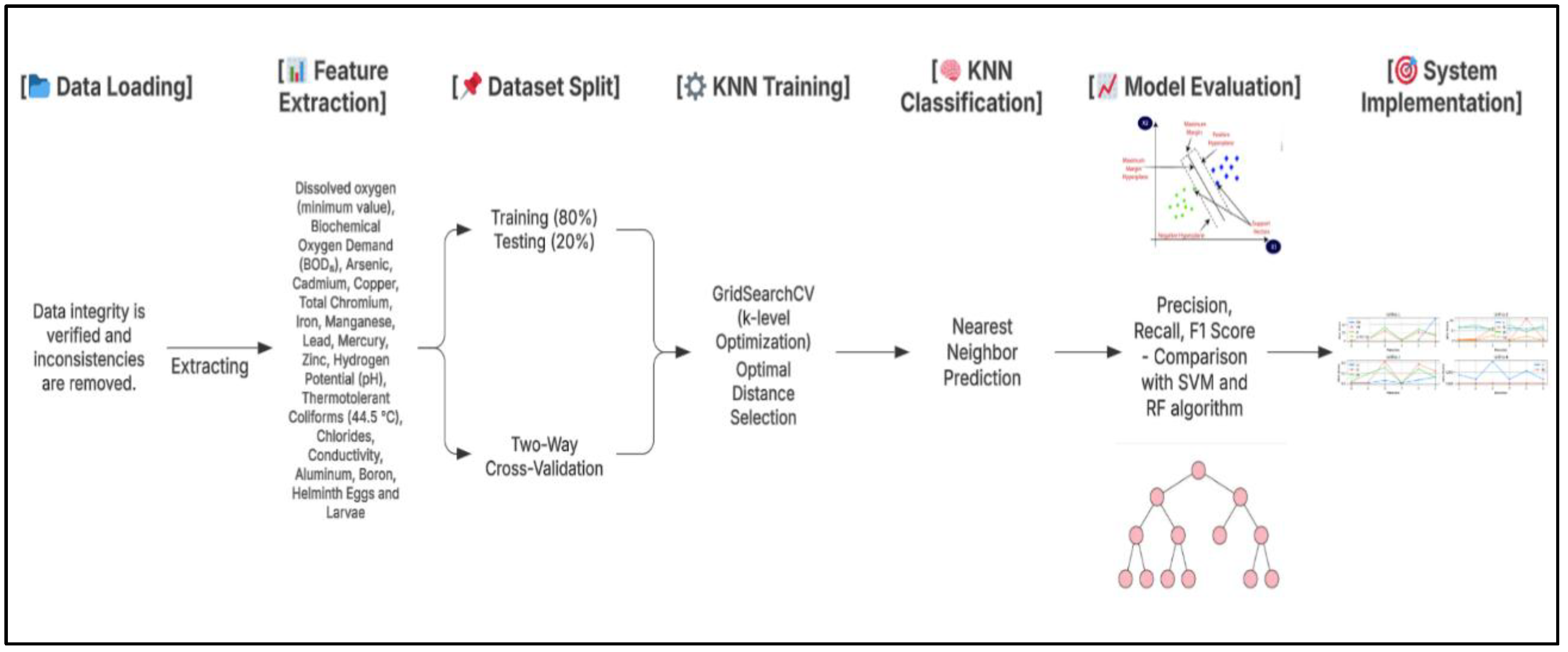

4. Methodology

4.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

4.1.1. Data Acquisition

- The dataset was obtained from the ANA which conducts regular water quality monitoring in Peru.

- Water samples were collected from multiple locations in the Huarmey basin.

- Physicochemical and Biological Attributes Considered:

- pH levels – Determines acidity or alkalinity.

- Dissolved Oxygen (DO) – Essential for aquatic life.

- Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) – Measures organic pollution levels.

- Heavy Metals (Pb, Zn, As, Cd, etc.) – Indicates industrial or agricultural contamination.

- Coliform Bacteria – Measures microbiological contamination.

4.1.2. Data Preprocessing

- Normalization – Standardizing numerical values to ensure uniform feature scaling.

- Handling missing values – Using imputation techniques to maintain data integrity.

- Encoding categorical labels – Converting WQI classification categories into numerical values (e.g., 1-A2 → Class 0, 3-D2 → Class 1).

4.2. KNN Model Implementation

4.2.1. Hyperparameter Optimization

- The optimal value of k was determined using GridSearchCV, which tested multiple values to maximize accuracy.

- The best-performing model was found at k=8.

4.2.2. Validation Method

- 5-Fold Cross-Validation was used to improve model reliability and prevent overfitting.

- Weighted F-score was selected as the primary evaluation metric.

| Aspect | Excel Macros (Traditional Method) | KNN-Based Classification |

| Accuracy (F-Score) | 75% | 90% |

| Processing Time | Several hours | Minutes |

| Error Margin | High (Manual Entry Errors, Formula Inconsistencies) | Low (Automated, Consistent Computation) |

| Scalability | Limited to Small Datasets | Efficient for Large-Scale Data |

| Human Intervention | Required for Data Entry and Formula Validation | Fully Automated Once Trained |

| Flexibility to New Data | Requires Manual Updates | Learns and Adapts from New Data |

4.3. Comparison with the Traditional WQI Method

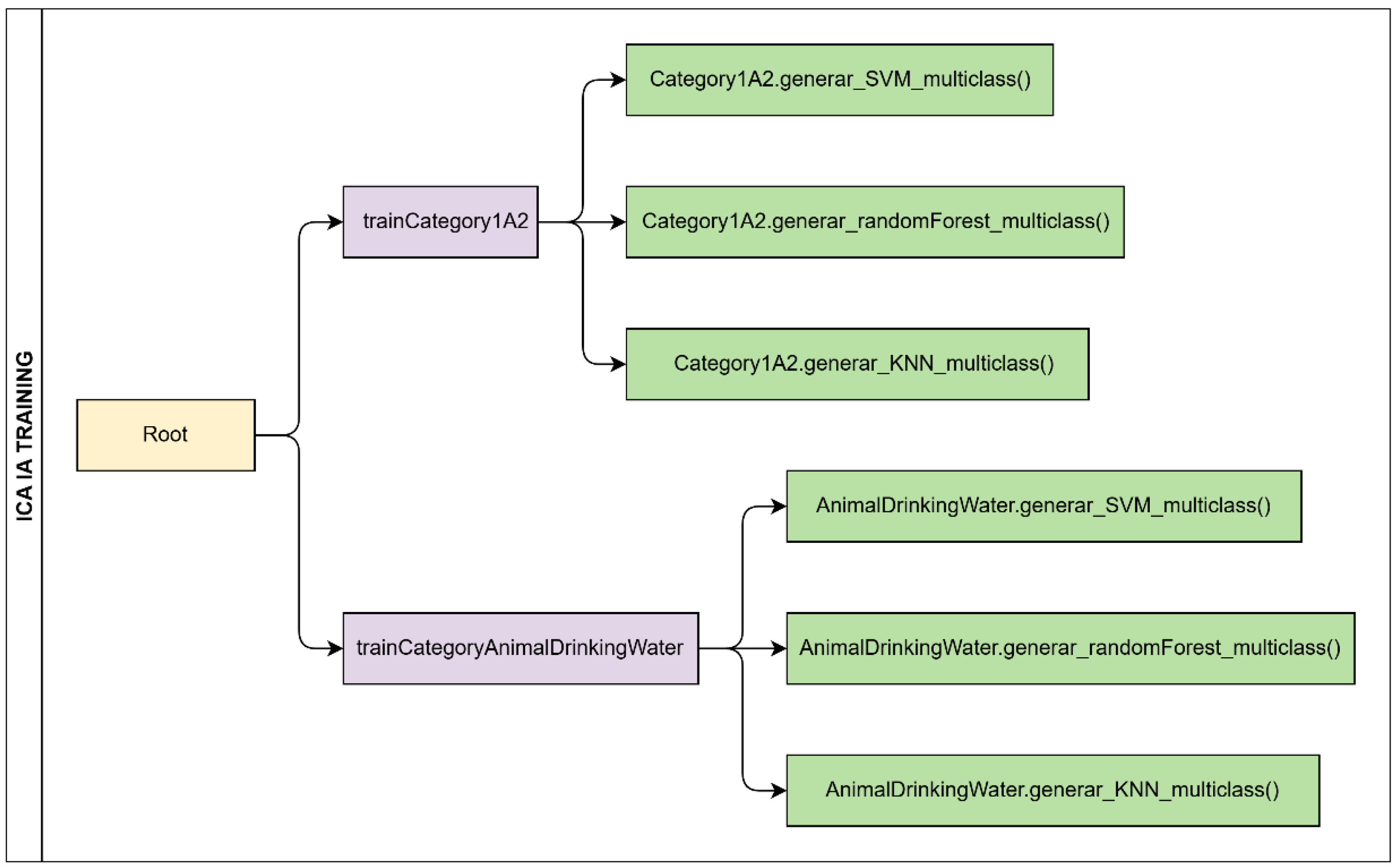

5. System Implementation

- Data Input Module: Receives raw water quality data.

- Preprocessing Module: Normalizes, cleans, and encodes the data.

- Training Module: Implements KNN with optimized hyperparameters.

- Classification Module: Classifies water quality into 1-A2 and 3-D2 categories.

- Visualization Module: Generates graphical outputs for better interpretation [37].

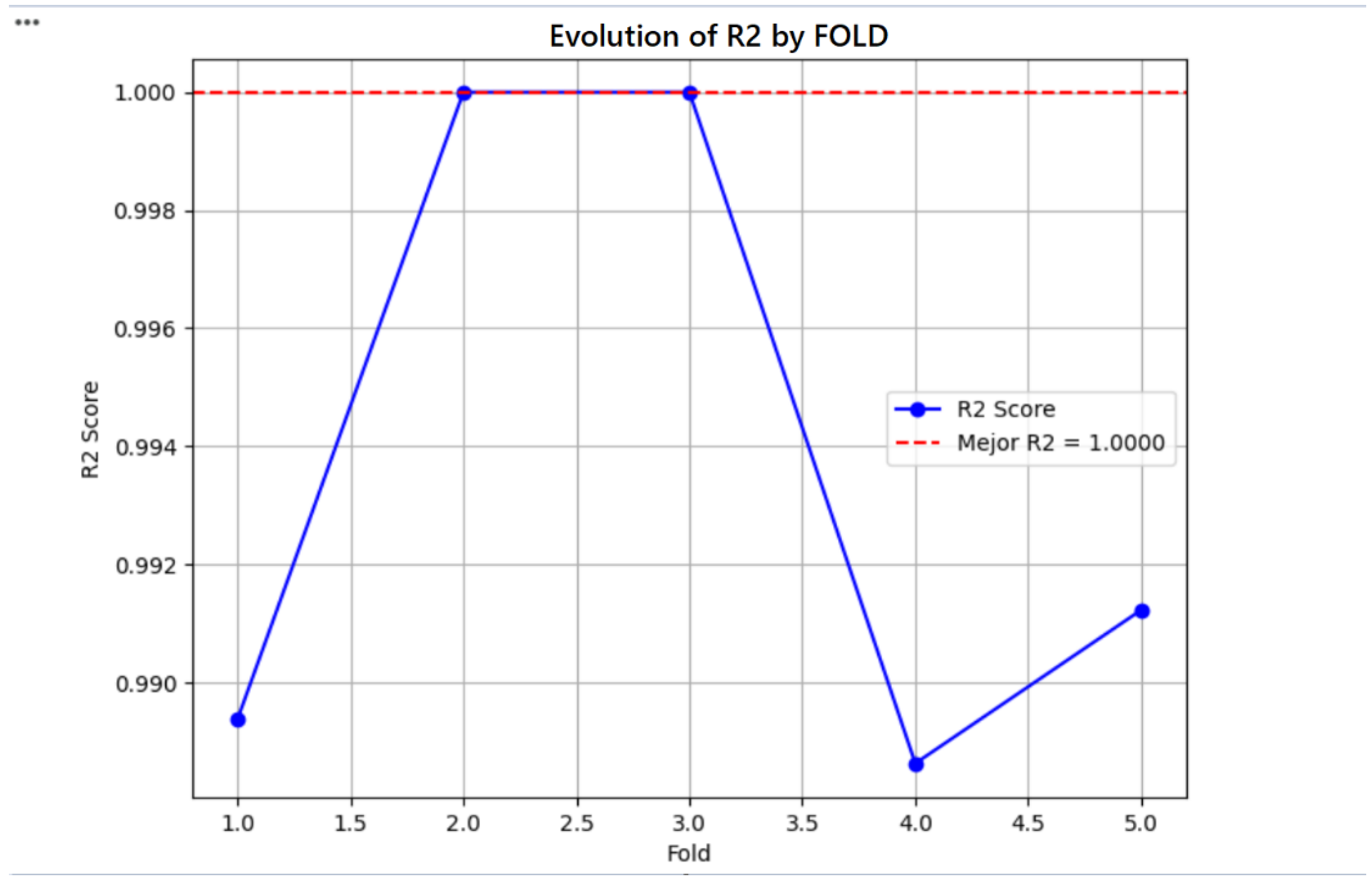

- High R² Scores Across Folds

- The R² score remains very close to 1, indicating a near-perfect prediction capability.

- Two folds (2 and 3) achieve an optimal R² score of 1.0000, highlighting the model's robustness.

- b.

- Stable Performance with Minor Variations

- Despite slight fluctuations in folds 1, 4, and 5, the scores remain above 0.99, ensuring high reliability.

- The minor dip in fold 4 still maintains an exceptionally high predictive accuracy, showcasing the model's generalization capability.

- c.

- Successful Model Export and Training Efficiency

- The model was successfully trained and exported with 8,000 samples, ensuring a well-generalized learning process.

- The structured approach, including label encoding and data partitioning, facilitated an efficient classification workflow.

6. Results

- Improved Accuracy: The KNN model provided a classification accuracy of 90% for human consumption (1-A2) and for animal drinking (3-D2).

- Reduced Processing Time: The model automated and accelerated the classification process, reducing manual intervention by 40%.

- Error Reduction: Cross-validation reduced the risk of overfitting, enhancing the reliability of the classification process [38].

6.1. Performance Metrics and Accuracy Comparison

- KNN significantly outperformed Excel-based classification, improving the f-score from 75% to 90%.

- Processing time was reduced from several hours to just minutes, making the model more suitable for large-scale and real-time applications.

- The model demonstrated strong generalization capabilities, meaning it maintained high accuracy across different datasets from 2020, 2021, and 2023.

6.2. Cross-Validation and Model Stability

- Without Cross-Validation: The model showed high variance, meaning performance fluctuated across different datasets.

- With Cross-Validation: The accuracy remained consistent, confirming the model's ability to generalize new water samples.

- GridSearchCV was used to optimize k, identifying k=8 as the best value. The f-score remained stable between 89%-91% across different folds, demonstrating robustness [22].

6.3. Comparison with Traditional WQI Classification Methods

- Higher accuracy with fewer errors.

- Significant time savings, completing tasks in minutes instead of hours.

- Automation and scalability, making it adaptable for larger datasets and future integrations with IoT-based water monitoring systems.

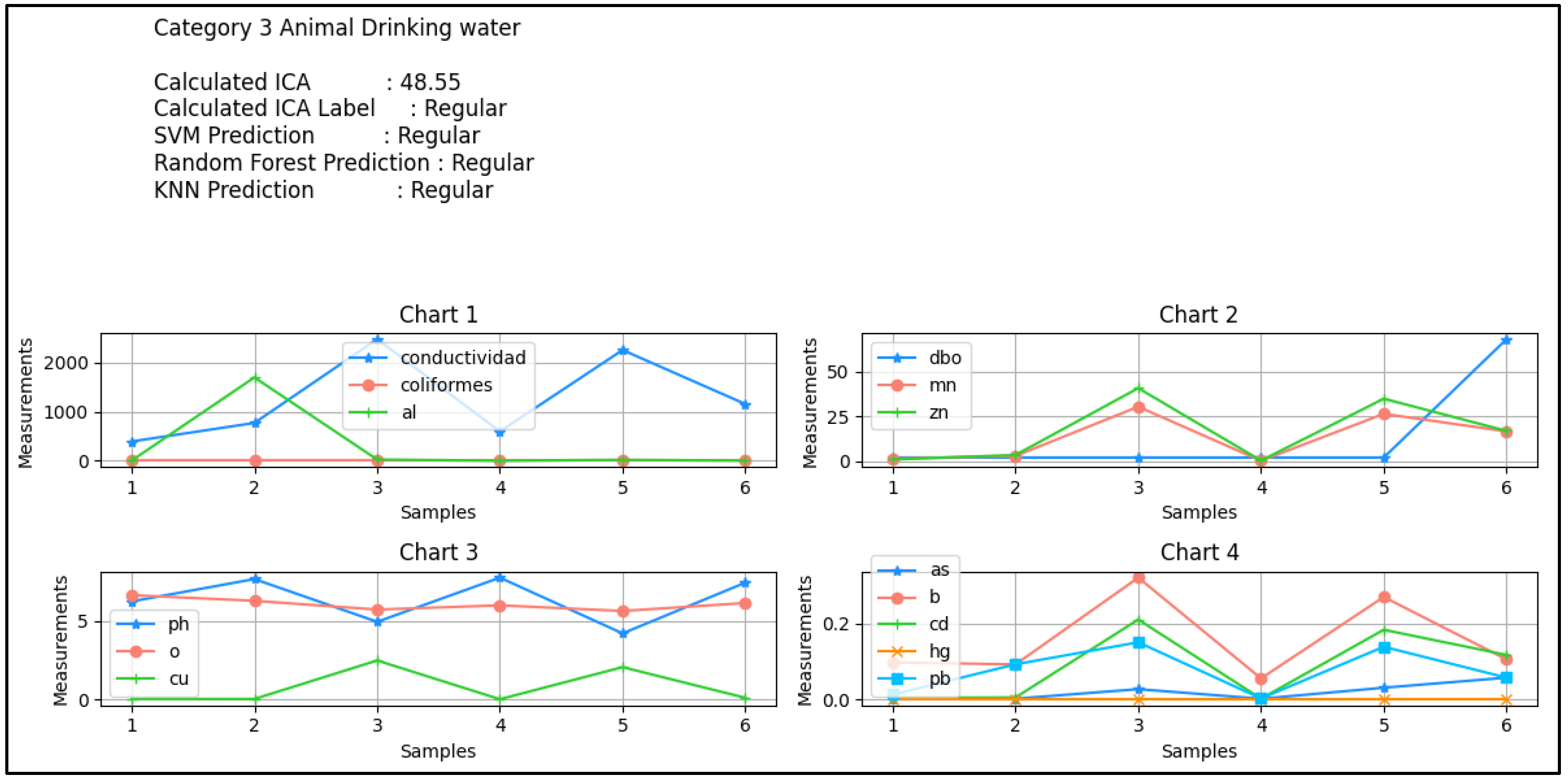

- Conductivity (blue) shows fluctuations across samples, with peaks at samples 4 and 6.

- Coliforms (orange) present a significant spike at sample 3, indicating a potential biological contamination event.

- Aluminum (al) (green) remains consistently low across all samples.

- BOD (blue) shows an increase in sample 6, suggesting a possible rise in organic matter.

- Manganese (mn) and Zinc (zn) remain relatively stable, with a slight increase at sample 3.

- pH (blue) remains stable throughout the samplings.

- Dissolved Oxygen (o) (orange) presents fluctuations but stays within an expected range.

- Copper (cu) (green) maintains low levels with minor variations.

- Cadmium (cd) and Lead (pb) show significant peaks at sample 3, indicating potential heavy metal contamination.

- Arsenic (as), Boron (b), and Mercury (hg) present small fluctuations but remain within low concentration levels.

6.4. Potential Impact of KNN for Water Quality Monitoring

- Real-Time Analysis: KNN enables rapid classification, allowing authorities to respond faster to contamination risks.

- Scalability: The model can process large datasets efficiently, making it suitable for nationwide applications.

- Adaptability: The system can incorporate new data over time, improving its predictions and accuracy.

7. Conclusions

- The implementation of KNN for WQI classification has demonstrated significant advantages over the traditional Excel-based method, improving both accuracy and processing efficiency. The key findings of this study highlight the effectiveness of machine learning in automating environmental data classification, offering a scalable solution for water monitoring systems [7].

- The weighted f-score increased from 75% (Excel) to 90% (KNN), demonstrating superior precision. This improvement reduces misclassification errors and enhances the reliability of water quality assessments. In the context of correct word use, an even more notable increase of 65% in scores was observed, compared to the control group. These findings highlight the positive and differential influence of system implementation, particularly in precision and appropriateness of word use [39].

- Real-time water quality monitoring using IoT sensors can automatically feed data into the KNN model, allowing instant classification and early detection of contamination events. Future studies should incorporate more extensive datasets, covering multiple regions and seasonal variations to improve model robustness and adaptability [40].

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Castillo Suarez, “Diseño Del Sistema De Abastecimiento De Agua Potable Para La Mejora De La Condición Sanitaria Del Caserío Molinopampa, Distrito De Malvas, Provincia De Huarmey, Región Ancash - 2020,” 2019.

- Autoridad Nacional de Agua, “MONITOREO DE LA CALIDAD DEL AGUA DE LA CUENCA AIJA-HUARMEY 2021 (11 de agosto al 22 de setiembre del 2021) PERÚ Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego Autoridad Nacional del Agua,” 2021.

- L. L. Ochoa, “Evaluation of Classification Algorithms using Cross Validation,” Ind. Innov. Infrastruct. Sustain. Cities Communities, pp. 24–26, 2019. [CrossRef]

- La República, “Áncash: Agua sin cloración consumen pobladores de ocho centros poblados de Huarmey | Sociedad | La República.” pp. 1–12, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://larepublica.pe/sociedad/2021/11/17/ancash-agua-sin-cloracion-consumen-pobladores-de-ocho-centros-poblados-de-huarmey-lrnd.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud, “Water, sanitation and hygiene links to health : Facts and figures.” 2022, [Online]. Available: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/69489.

- E. E. Hussein et al., “Groundwater Quality Assessment and Irrigation Water Quality Index Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Cakir, M. Yilmaz, M. A. Oral, H. Ö. Kazanci, and O. Oral, “Accuracy assessment of RFerns, NB, SVM, and kNN machine learning classifiers in aquaculture,” J. King Saud Univ. - Sci., vol. 35, no. 6, p. 102754, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ancash Noticias, “Preocupante: ANA constata la mala calidad de agua en la cuenca de agua del río de Huarmey - Ancash Noticias Ancash Noticias.” 2021, [Online]. Available: https://ancashnoticias.com/2021/01/03/ancash-ana-constata-la-mala-calidad-de-la-cuenca-de-agua-del-rio-de-huarmey/.

- E. Dritsas and M. Trigka, “Efficient Data-Driven Machine Learning Models for Water Quality Prediction,” Computation, vol. 11, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Vega, E. Sanez, P. D. La Cruz, S. Moquillaza, and J. Pretell, “Intelligent System to Predict University Students Dropout,” Int. J. online Biomed. Eng., vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 27–43, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Villanueva-Alarcon and H. Vega-Huerta, “PConvolutional Neural Networks on assembling classification models to detect mel-anoma skin cancer Convolutional Neural Networks on Assembling Classifi-cation Models to Detect Melanoma Skin Cancer.” 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. L. E. Maquen-Niño et al., “Brain Tumor Classification Deep Learning Model Using Neural Networks,” Int. J. online Biomed. Eng., vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 81–92, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. De-La-Cruz, R. Rojas-Coaquira, H. Vega-Huerta, J. Pérez-Quintanilla, and M. Lagos-Barzola, “A Systematic Review Regarding the Prediction of Academic Performance,” Journal of Computer Science, vol. 18, no. 12. Science Publications, pp. 1219–1231, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Yauri, M. Lagos, H. Vega-huerta, P. De-la-cruz-vdv, G. L. E. Maquen-niño, and E. Condor-tinoco, “Detection of Epileptic Seizures Based-on Channel Fusion and Transformer Network in EEG Recordings,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 14, no. 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. L. E. Maquen-niño, J. Bravo, R. Alarcón, I. Adrianzén-olano, and H. Vega-huerta, “Una revisión sistemática de Modelos de clasificación de dengue utilizando machine learning,” RISTI - Rev. Iber. Sist. e Tecnol. Inf., vol. 6, no. 50, pp. 5–27, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Vega-Huerta, K. Pantoja-Pimentel, S. Quintanilla Jaimes, G. Maquen-Niño, P. De-La-Cruz-VdV, and L. Guerra-Grados, “Classification of Alzheimer’s Disease Based on Deep Learning Using Medical Images,” vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 101–114, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Vega-huerta et al., “Reconocimiento facial mediante aprendizaje por transferencia para el control de acceso a áreas restringidas,” pp. 261–273, 2023.

- H. Vega-huerta et al., “Intelligent Facial Recognition System for Vehicles,” Springer Int. Publ., 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Vega-huerta et al., “Classification Model of Skin Cancer Using Convolutional Neural Network,” Ingénierie des Systèmes d ’ Inf., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 387–394, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. DelaCruz-VdV et al., “Diagnosis of Brain Tumors using a Convolutional Neural Network,” Smart Innov. Syst. Technol., vol. 366, p. Pages 45-56, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Zounemat-Kermani, O. Batelaan, M. Fadaee, and R. Hinkelmann, “Ensemble machine learning paradigms in hydrology: A review,” Journal of Hydrology, vol. 598. Elsevier B.V., 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Tahraoui et al., “Advancing Water Quality Research: K-Nearest Neighbor Coupled with the Improved Grey Wolf Optimizer Algorithm Model Unveils New Possibilities for Dry Residue Prediction,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua, “Metodología para la determinación del índice de calidad de agua Ica-PE, aplicado a los cuerpos de agua continentales superficiales.” pp. 1–55, 2018, [Online]. Available: https://repositorio.ana.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12543/2440.

- Gestión sostenible del agua, “Sustainable Water Management.” 2024, [Online]. Available: https://www.agry.purdue.edu/hydrology/projects/nexus-swm/es/Tools/WaterQualityCalculator.php.

- N. Nasir et al., “Water quality classification using machine learning algorithms,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 48, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Huang, B. Q. Hu, H. Jiang, and B. W. Fang, “A water quality prediction method based on k-nearest-neighbor probability rough sets and PSO-LSTM,” Appl. Intell., vol. 53, no. 24, pp. 31106–31128, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Hamzaoui, M. O. E. Aoueileyine, and R. Bouallegue, “A Hybrid Method of K-Nearest Neighbors with Decision Tree for Water Quality Classification in Aquaculture,” in Communications in Computer and Information Science, 2023, vol. 1864 CCIS, pp. 287–299. [CrossRef]

- C. Janiesch, P. Zschech, and K. Heinrich, “Machine learning and deep learning,” Electron. Mark., vol. 31, no. 3, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Linardatos, V. Papastefanopoulos, and S. Kotsiantis, “Explainable ai: A review of machine learning interpretability methods,” Entropy, vol. 23, no. 1. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Savitri and R. Nursalim, “Klasifikasi Kualitas Air Minum menggunakan Penerapan Algoritma Machine Learning dengan Pendekatan Supervised Learning,” Diophantine J. Math. Its Appl., vol. 2, no. 01, pp. 30–36, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Fernández-Hernández, P. Herranz-Hernández, and L. Segovia-Torres, “Validación cruzada sobre una misma muestra: Una práctica sin fundamento,” R.E.M.A. Rev. Electrónica Metodol. Apl., vol. 24, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. López Lozano, I. Palazón Bru, A. Palazón Bru, M. Arroyo Fernández, and M. González-Estecha, “Procedimiento de validación de un método para cuantificar cobalto en suero por espectroscopia de absorción atómica con atomización electrotérmica,” Rev. del Lab. Clin., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 46–51, 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Ainapure, N. Baheti, J. Buch, B. Appasani, A. V Jha, and A. Srinivasulu, “Drinking water potability prediction using machine learning approaches: A case study of Indian rivers,” Water Pract. Technol., vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 3004–3020, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Chen, “Unlocking policy effects: Water resources management plans and urban water pollution,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 365, p. 121642, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua, “Monetoreo_de_parametros_cuenca_Huarmey_2023,” 2023.

- M. Y. Shams, A. M. Elshewey, E. S. M. El-kenawy, A. Ibrahim, F. M. Talaat, and Z. Tarek, “Water quality prediction using machine learning models based on grid search method,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 83, no. 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Uddin, S. Nash, A. Rahman, and A. I. Olbert, “Performance analysis of the water quality index model for predicting water state using machine learning techniques,” Process Saf. Environ. Prot., vol. 169, pp. 808–828, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Seyedmohammadi, A. Zeinadini, M. N. Navidi, and R. W. McDowell, “A new robust hybrid model based on support vector machine and firefly meta-heuristic algorithm to predict pistachio yields and select effective soil variables,” Ecol. Inform., vol. 74, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Kanyama, F. B. Shava, A. M. Gamundani, and A. Hartmann, “Machine learning applications for anomaly detection in Smart Water Metering Networks: A systematic review,” Phys. Chem. Earth, vol. 134, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Saddiqi, Z. Javed, Q. M. Ali, A. Ullah, and I. Ahmad, “Modelling and predicting lift force and trans-membrane pressure using linear, KNN, ANN and response surface models during the separation of oil drops from produced water,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 66, p. 106014, 2024. [CrossRef]

| WQI- PE | Rating | Interpretation |

| 100 - 90 | Excellent | The water quality is protected with no threats or damage. Conditions are very close to natural or desirable levels. |

| 89 - 75 | Good | The water quality deviates slightly from its natural state. However, desirable conditions may be affected by minor threats or damage. |

| 74 - 45 | Regular | Natural water quality is occasionally threatened or degraded. Water quality often deviates from desirable values. Many uses require treatment. |

| 44 - 30 | Poor | The water quality does not meet quality objectives, and desirable conditions are frequently threatened or degraded. Many uses require treatment. |

| 29 - 0 | Very Poor | The water quality does not meet quality objectives, is almost always threatened or degraded, and all uses require prior treatment. |

| Method | Processing Time | Accuracy (F-Score) |

| Excel Macros | Hours | 75% |

| KNN (Optimized, k=8) | Minutes | 90% |

| Method | F-Score (%) | Processing Time | Scalability |

| Excel Macros (Manual) | 75% | Several hours | Limited (Manual Handling) |

| KNN (Optimized, k=8) | 90% | Minutes | High (Automated) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).