Introduction

Non-uniformity or unevenness is inherent in probability distributions because outcomes or values from a probability system are generally not uniformly or evenly distributed. While the shape of a distribution can provide an intuitive understanding of its non-uniformity, researchers often need a quantitative measure of non-uniformity (or unevenness) that can be useful for building distribution models or for comparing different distributions.

A probability distribution is considered uniform if all outcomes have equal probability (in the discrete case) or if its probability density is constant (in the continuous case). Consequently, a uniform distribution should be used as a baseline for measuring the non-uniformity of a given distribution. That is, non-uniformity refers to how a probability distribution deviates from a baseline uniform distribution. It is important to note that comparing a given distribution to the baseline uniform distribution assumes that both distributions are defined on the same support. This is especially critical in the continuous case, where ensuring that the support is fixed is essential for a meaningful comparison.

The Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence can be employed as a metric for measuring the non-uniformity of a given distribution by quantifying how different the distribution is from a baseline uniform distribution. A small KL divergence value indicates that the distribution is close to uniform. The KL divergence is applicable in both the discrete case and in the continuous case provided that the support is fixed. However, one significant drawback of using the KL divergence in this context is that it is unbounded. While a KL divergence value of zero represents perfect uniformity, there is no natural upper limit that allows us to contextualize how “non-uniform” a distribution is. This lack of an upper bound can make interpretation challenging, especially when comparing different distributions or when the scale of the divergence matters.

In recent work, Rajaram et al. (2024a, b), proposed a measure called the “degree of inequality” to quantify how evenly the probability mass (or density) is spread over the available outcomes or support. They defined the degree of inequality (DOI) for a partial distribution on a fixed interval as the ratio of the exponential of the Shannon entropy of the partial distribution to the coverage probability of that interval. That is (Rajaram et al., 2024a, b),

where the subscript “P” stands for “part”, referring to the partial distribution on a fixed interval of the given distribution,

represents the coverage probability of the interval,

is the entropy of the partial distribution, and

is the entropy-based diversity of the partial distribution. It is noted that Rajaram et al. (2024a) also named the ratio

as the “degree of uniformity”. However, calling this ratio the “degree of inequality” (or “degree of uniformity”) is potentially misleading, as it behaves more like an

amplified diversity than a bounded evenness/unevenness index. In addition, the DOI diverges as

. This means that, tiny probability (for small intervals) will yield huge DOI values. Moreover, the DOI is not a standardized (or normalized) quantity. The lack of standardization can hinder comparisons between different distributions, as absolute values may not have an intuitive interpretation without a proper reference point. Thus, the unstandardized nature of the DOI limits its usefulness as a generally comparable indicator of the non-uniformity of distributions.

Classical evenness measures such as Simpson’s evenness and Buzas & Gibson’s evenness are essentially diversity ratios. Simpson’s evenness is given by (e.g., Roy & Bhattacharya, 2024)

Buzas & Gibson’s evenness is given by (Buzas & Gibson, 1969)

where

H is the Shannon entropy of the given distribution.

However, Gregorius and Gillet (2021) pointed out, “Diversity-based methods of assessing evenness cannot provide information on unevenness, since measures of diversity generally do not produce characteristic values that are associated with states of complete unevenness.” This is because measures of diversity are aimed at properties of individual distributions rather than differences between such distributions, which makes them difficult to transform into meaningful distance measures (Gregorius & Gillet, 2021).

It is important to note that the non-uniformity or unevenness of a given distribution should be measured by a distance relative to the ideal of perfect uniformity. However, the DOI proposed by Rajaram et al. (2024a, b), or the diversity-based evenness measures and never compute any distance relative to a uniform benchmark.

The aim of this study is to develop a new index for measuring the non-uniformity of a probability distribution. In the following sections,

Section 2 describes the proposed distribution non-uniformity index (DNUI).

Section 3 presents several examples.

Section 4 provides discussion and conclusion.

2. The Proposed Distribution Non-Uniformity Index (DNUI)

2.1. Discrete Cases

Consider a discrete random variable X with probability mass function (PMF) and n possible outcomes. Let denote the uniform distribution with the same possible outcomes, so that for all x. We use this uniform distribution as the baseline for measuring the non-uniformity of the distribution of X.

The difference between

and

is given by

Thus, can be written as

Taking squares on both sides of Eq. (5) yields

Then taking the expectation on both sides of Eq. (6) yields

where is called the total variance and is called the total deviation

where

is the variance of

relative to

, given by

is the bias of

relative to

, given by

where

is the informity of

X. The concept of informity is introduced in Huang (2025). The informity of a discrete random variable is defined as the expectation of its PMF. The informity of the baseline uniform distribution

, is

. Thus,

is the seen as the informity bias.

Definition 1. The proposed distribution non-uniformity index (DNUI) (denoted by

) is given by

is the root mean square (RMS) of

and

is the

second moment of the probability , given by

2.2. Continuous Cases

Consider the continuous random variable

Y with probability density function (PDF)

defined on an unbounded support (e.g.,

)). Since no baseline uniform distribution exists for an unbounded support, we cannot measure the non-uniformity of the entire distribution of

Y. Instead, we focus on a partial distribution of

Y on a fixed interval

. According to Rajaram et al. (2024a), the PDF of the partial distribution is given by renormalization of the original PDF

where

, which is the coverage probability of the interval

.

Let denote the uniform distribution on with density . We use this uniform distribution as the baseline for measuring the non-uniformity of the partial distribution.

Similar to the discrete cases, the difference between

and

is given by

Thus, can be written as

Taking squares on both sides of Eq. (15) yields

Then taking the expectation on both sides of Eq. (16) yields

The total deviation is given by

where

is the variance of

relative to

on

, given by

is the bias of

relative to

, given by

Definition 2. The proposed DNUI for the partial distribution on

(denoted by

) is given by

where

is the second moment of the probability density

, given by

Definition 3. If the continuous distribution is defined on the fixed support

,

and

, the proposed DNUI for the entire distribution of

Y (denoted by

is given by

where

is the second moment of the probability density

, given by

the variance

is given by

and the bias

is given by

3. Examples

3.1. Coin-Tossing

Consider tossing a coin, which is a simplest two-state probability system: {

X;

P(

x)}={head, tail;

P(head),

P(tail)}, where

. The DNUI for this system is given by

where the second moment

can be calculated as

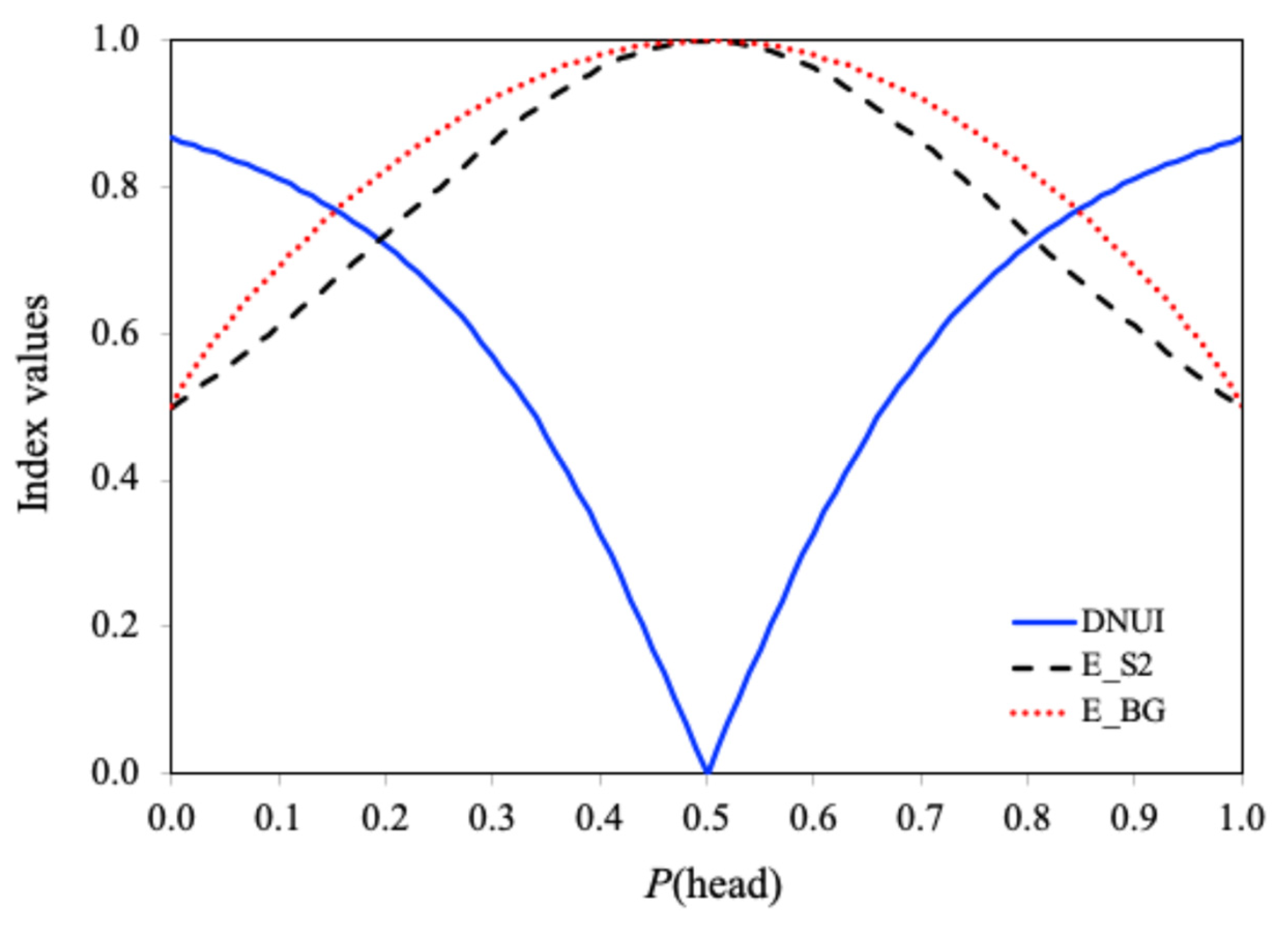

Figure 1 shows the DNUI of the coin-tossing system as a function of the bias represented by

. The two evenness measures: Simpson’s evenness

and Buzas & Gibson’s evenness

are also shown in the figure for comparison.

As shown in

Figure 1, when the coin is fair, i.e.,

, the DNUI is 0, and Simpson’s evenness

and Buzas & Gibson’s evenness

are both 1, indicating perfect uniformity. When a coin is highly biased towards the tail or head, the DNUI increases, while both Simpson’s evenness

and Buzas & Gibson’s evenness

decrease. In the most extreme case where

or

, the DNUI is the highest:

, indicating the highest non-uniformity or unevenness. However, although

and

are the lowest, i.e.,

, this value does not reflect the high degree of unevenness. This confirms the argument of Gregorius and Gillet (2021): “… measures of diversity generally do not produce characteristic values that are associated with states of complete unevenness.”

3.2. Three Frequency Data Series

JJC (2024) posted a question on Cross Validated about quantifying distribution non-uniformity. He supplied three frequency datasets (Series A, B, and C), each containing 10 values (

Table 1). Visually, Series A is almost perfectly uniform, Series B is nearly uniform, and Series C is heavily skewed by a single outlier (0.6).

Table 1 lists these datasets alongside their corresponding DNUI,

, and

values.

From

Table 1, we can see that the DNUI value of Series A is 0.1864, confirming its high uniformity, and the DNUI value of Series B is 0.2499, indicating its close uniformity. In contrast, the DNUI value of Series C is 0.9767 (close to 1), indicating its extreme non-uniformity. On the other hand, the

and

values for Series A and Series B are close to 1, indicating high uniformity. The

value for Series C is 0.2625, indicating the high degree of unevenness. However, the

value for Series C is 0.4545, not reflecting the high degree of unevenness.

3.3. Five Continuous Distributions with Fixed Support

Consider five continuous distributions with fixed support

: uniform, triangular, quadratic, raised cosine, and half-cosine.

Table 2 summarizes their PDFs, variances, biases,

second moments, and DNUIs.

As can be seen from

Table 2, the DNUI is independent of the scale parameter

a, which is a desirable property for the measures of distribution non-uniformity. The DNUI value for the uniform distribution is 0, which is by definition. The DNUI for the other four distribution are all greater than 0.9, indicating these four distributions are highly non-uniform. This result is consistent with our common sense. In addition, for the raised cosine distribution, the DNUI is the highest among the five distributions, indicating that it is the greatest non-uniformity.

3.4. Exponential Distribution

The PDF of the exponential distribution with support

is

where

is the shape parameter.

We consider the partial exponential distribution on the interval [

(i.e.,

and

), where

b is the length of the interval. The informity of the baseline uniform distribution on [

is 1/

. Thus, the DNUI for the partial exponential distribution on [

is given by

where the second moment

is given by

The coverage probability of the interval [

is given by

The integral

can be solved as

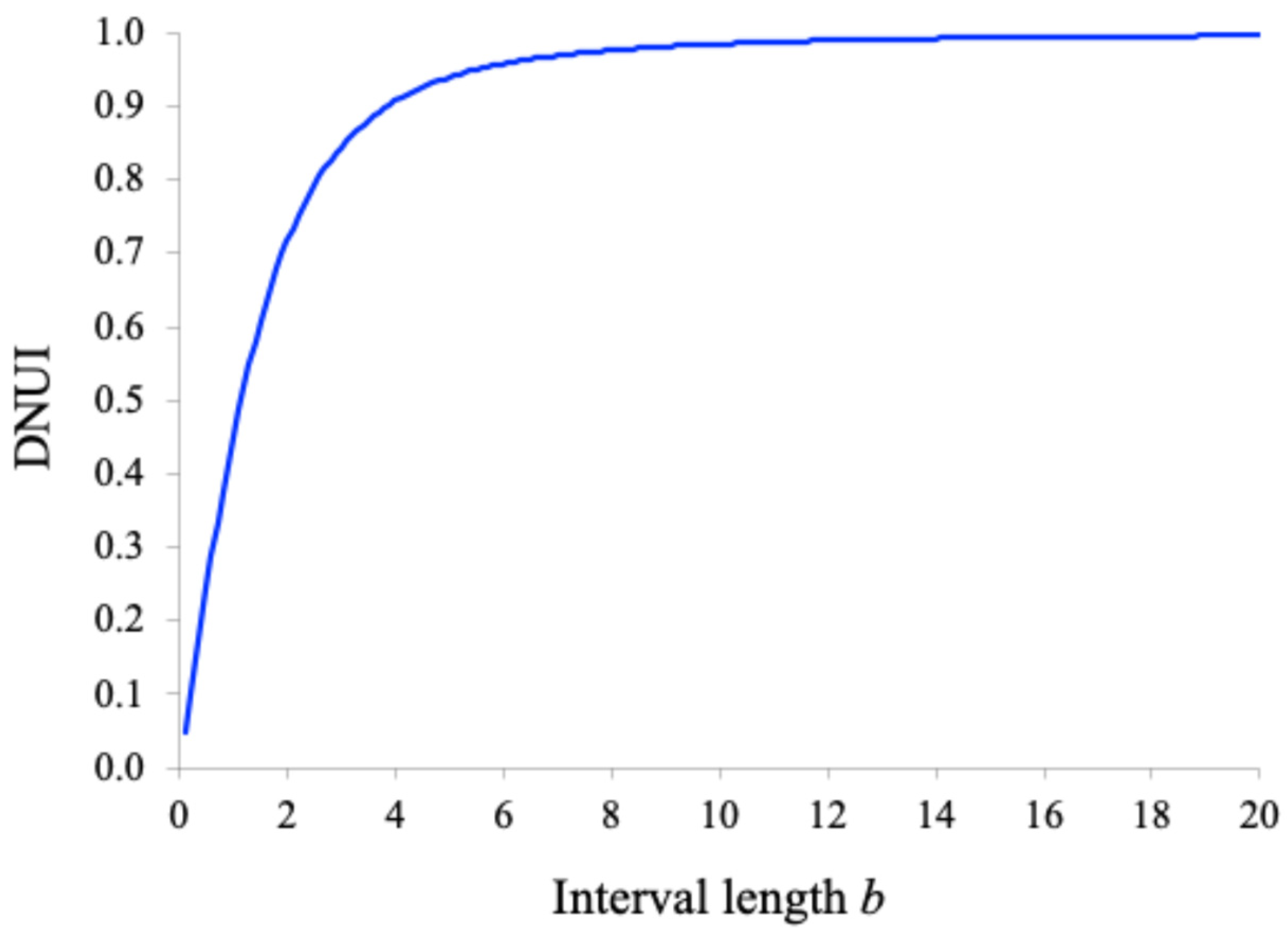

Figure 2 shows the plots of the DNUI for the partial exponential distribution with

as a function of the interval length

b. As the interval length

b increases, the DNUI increases, indicating that the non-uniformity of the partial distribution increases with a longer interval.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Unlike the degree of inequality (DOI) proposed by Rajaram et al. (2024a, b) or the diversity-based evenness measures and (which are not distance measures), the proposed DNUI is a standardized distance measure based on the total deviation defined by Eq. (8). It is important to note that the total deviation consists of two components: variance and bias, both of which are relative to the baseline uniform distribution.

The proposed DNUI ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates perfect uniformity and 1 indicates extreme non-uniformity. Lower DNUI values (close to 0) indicate a lower degree of non-uniformity or a flatter distribution, while larger DNUI (close to 1) values correspond to a higher degree of non-uniformity or a more uneven distribution. However, there is no universal standard for defining the level (or degree) of non-uniformity of a distribution. Based on the examples presented, we tentatively propose to use DNUI values of 0.4, 0.7, and 0.85 (corresponding to low, moderate, and high non-uniformity, respectively) to assess the levels of non-uniformity of a distribution.

It is important to note that the DNUI depends solely on the probabilities and not on the outcomes (or scores) or the specific order of outcomes. This property can be demonstrated with the frequency data from Series C in subsection 3.1: {0.03, 0.02, 0.6, 0.02, 0.03, 0.07, 0.06, 0.05, 0.05, 0.07}. If we swap the order of the second and third frequency values, the DNUI values remains unchanged. This invariance means that different distributions can yield the same DNUI value. In other words, the DNUI is not a one-to-one function of the distribution; it can “collapses” different distributions into the same DNUI value. This is similar to how different distributions can have the same mean or variance.

In summary, the proposed distribution non-uniformity index (DNUI) provides effective measures for assessing the non-uniformity of a probability distribution. It is applicable to any distribution with fixed support and can also be used for a partial distribution defined on a fixed interval, even when the entire distribution has unbounded support. The presented examples have demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed DNUI in capturing and quantifying distribution non-uniformity.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, H. The theory of informity: a novel probability framework. Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (accepted for publication). 2025. [Google Scholar]

- JJC (https://stats.stackexchange.com/users/10358/jjc), How does one measure the non-uniformity of a distribution? URL (version: 2024-10-12):https://stats.stackexchange.com/q/25827.

- Rajaram, R.; Ritchey, N.; Castellani, B. On the mathematical quantification of inequality in probability distributions. J. Phys. Commun. 2024, 8, 085002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaram, R.; Ritchey, N.; Castellani, B. On the degree of uniformity measure for probability distributions. J. Phys. Commun. 2024, 8, 115003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzas, M.A.; Gibson, T.G. Species diversity: benthonic foraminifera in western North Atlantic. Science 1969, 163, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorius, H.R.; Gillet, E.M. The Concept of Evenness/Unevenness: Less Evenness or More Unevenness? Acta Biotheor. 2021, 70, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorius, H.; Gillet, E.M. On the diversity-based measures of equalness and evenness. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2024, 15, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Bhattacharya, K.R. A theoretical study to introduce an index of biodiversity and its corresponding index of evenness based on mean deviation. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 022–032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).