1. Introduction

Hip fractures among the elderly constitute a major global health challenge, resulting in considerable morbidity, functional decline, extended hospital stays, and high mortality rates [

1,

2]. As populations age, the incidence of hip fractures rises globally, posing significant implications for patients and healthcare systems [

3,

4]. Over 300,000 Americans aged 65 and older sustain hip fractures annually, with similar trends elsewhere [

3,

4]. Age-related frailty makes this group highly vulnerable to postoperative complications, underscoring the need for early risk stratification upon hospital admission [

5,

6]. Conventional predictors such as advanced age, comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index, CCI), nutritional deficiencies (hypoalbuminemia), and cardiovascular biomarkers (N-terminal pro–B-type Natriuretic Peptide NT-proBNP) are established indicators of poor outcomes following surgery [

5,

6,

7]. However, the role of systemic inflammatory responses in recovery needs further exploration [

8]. Growing evidence emphasizes inflammatory markers as prognostic tools across surgical fields [

9,

10,

11]. Among these, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have gained attention. Elevated NLR reflects a heightened pro-inflammatory state with neutrophilia and lymphopenia, linked to infection, poor healing, and worse prognosis [

9,

10,

12]. Similarly, high PLR indicates systemic inflammation and altered thrombosis, contributing to perioperative complications [

12,

13]. Despite research into NLR and PLR in cancer, cardiovascular, and infectious diseases [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], their prognostic role in hip fracture surgery remains underexplored [

14]. Addressing this knowledge gap is crucial given the clinical and economic burden of hip fractures. A refined evaluation of NLR and PLR could offer cost-effective tools for early risk identification and personalized perioperative care. Recognizing high-risk patients via these accessible biomarkers may enhance monitoring, preemptive intervention, and resource allocation, improving outcomes and reducing healthcare strain. This study aims to investigate the associations between NLR and PLR at emergency admission and short-term (30-day, 90-day) and long-term (1-year, overall) mortality, ICU admissions, and prolonged hospital stays (over 15 days) in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. By clarifying their predictive value, we hope to provide clinicians with practical, evidence-based tools for optimizing patient management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

This retrospective, single-center cohort study included patients admitted to the Emergency Department of our institution with hip fractures between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2023. The study adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [

15].

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were aged 65 years or older and sustained a hip fracture following a low-energy trauma, defined as a fall from standing height or lower. Patients were excluded if they were deemed inoperable, had pathological fractures, presented with established sepsis at admission, had previous surgery for femoral neck fracture, or were affected by advanced malignancies.

2.3. Data Collection and Database Formations

At admission, all patients were registered in a standardized institutional database capturing demographic information (sex, age), clinical variables (CCI, type of fracture), and pre-existing anticoagulant therapy. For this analysis, additional surgical data (type of surgery performed, time from emergency admission to surgery) and laboratory parameters measured at admission were extracted. Laboratory data included complete blood count (used to calculate NLR and PLR according Vitiello et al. [

8]), hemoglobin concentration, serum albumin level (hypoalbuminemia defined as albumin <3.5 g/dL), and NT-proBNP values (A cut-off value of 1099 ng/l was established according to Zhang et al. [

7]). Time to surgery was treated as both a continuous and categorical variable, distinguishing early (<48 hours) versus delayed (≥48 hours) interventions. Length of stay (LoS) was recorded as a continuous measure, with a prolonged hospitalization defined as a stay exceeding 15 days.

2.4. Outcome Measures

Primary endpoints were 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included the necessity of postoperative admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and prolonged hospitalization (LoS >15 days). Mortality data were collected through hospital records and follow-up contact with primary care physicians or relatives when necessary.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

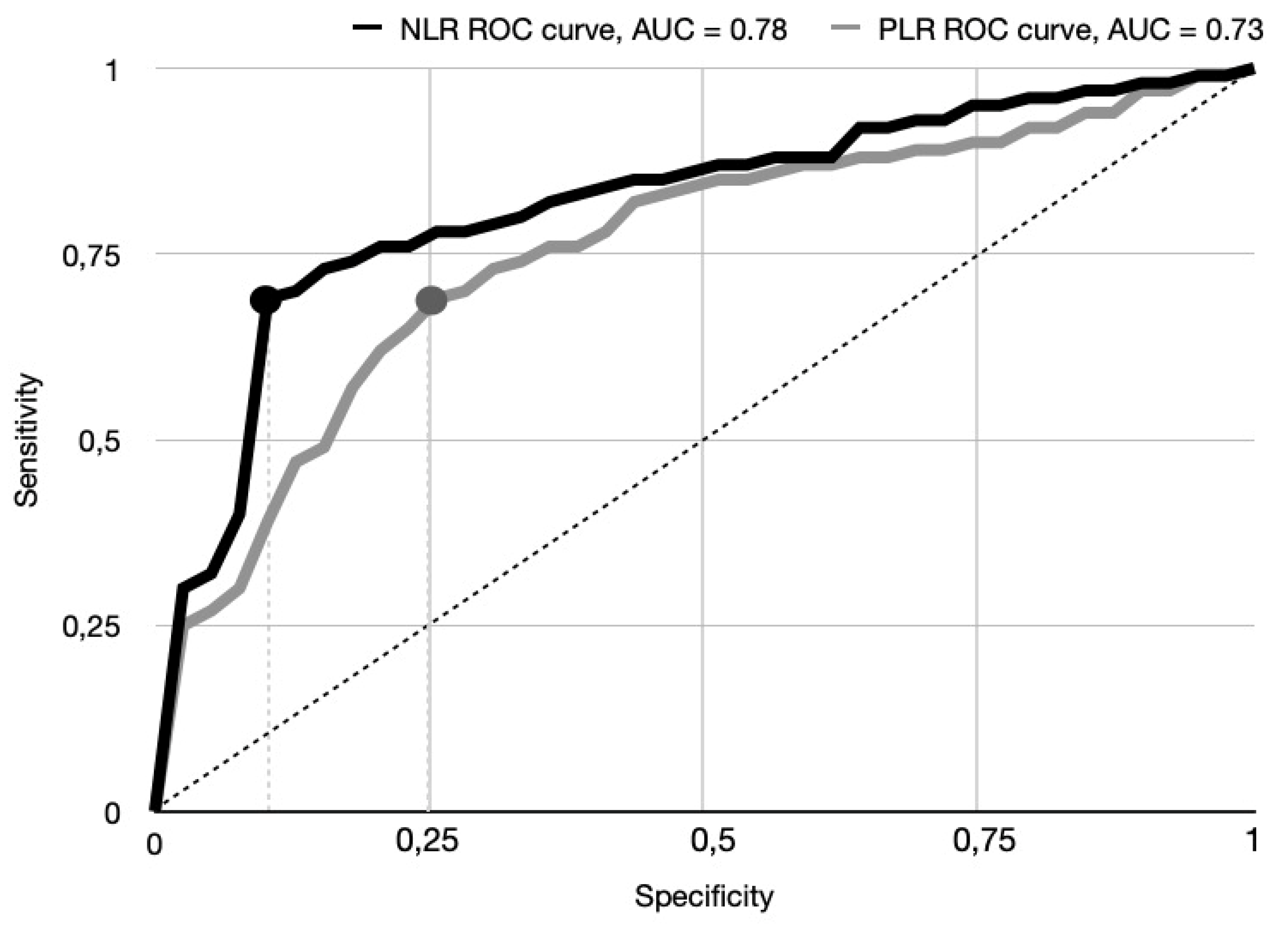

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data completeness was assessed, and missing continuous values (<3% of cases) were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations, ensuring robust variance estimates. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) and compared using the independent samples t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Univariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were conducted to explore associations between candidate predictors and outcomes (30-day and 90-day mortality, ICU need, and prolonged LoS). Predictors with a p-value <0.10 in univariable analyses were selected for multivariable Cox regression models to identify independent risk factors for 1-year and total mortality. Model assumptions, including proportional hazards, were tested using Schoenfeld residuals. The predictive performance of inflammatory markers (NLR, PLR) for 30-day mortality and ICU need was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses, and optimal thresholds were determined using the Youden Index. NLR and PLR cut-off values were established at 7.2 and 189.4, respectively. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in

Table 1. Among the records of 632 patients, only 395 patients met inclusion and exclusion criteria therefore were included in the final analysis, with a mean age of 84 years (SD 12.3), and females representing 56.4% of the cohort. Fracture types were distributed as follows: 46.7% were intertrochanteric fractures, 28.5% sub-capital fractures, and 24.8% basi-cervical fractures. Surgical management predominantly involved internal fixation (64.3%), with hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty accounting for 18.3% and 13.6% of cases respectively, while cannulated screw fixation was performed in 3.8% of patients. The median time from admission to surgery was 2.9 days (IQR 0.5–5.9), with 72.4% of surgeries completed within 48 hours. The observed rates of mortality were 4.8% at 30 days, 10.5% at 90 days, and 13.9% at one year, with a total mortality rate of 28% during the study period. Postoperative admission to the ICU was required for 9.6% of patients, and 15.9% experienced prolonged hospitalization, defined as a length of stay exceeding 15 days, with a mean hospitalization duration of 9 days (SD 3.2).

3.2. NLR and PLR Cut-Off Value Determination

Univariate analysis followed by ROC curve analysis was performed to identify optimal cut-off values for NLR and PLR in predicting the primary outcome of 30-day mortality. This analysis yielded a cut-off value of 7.2 for NLR and 189.4 for PLR. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for NLR was 0.78 [95% CI 0.66–0.81], indicating good discriminatory power for 30-day mortality. Specifically the sensitivity prediction of NLR > 7.2 was 69.7%, and the specificity was 85.4% The AUC for PLR was 0.73 [95% CI 0.61–0.79], suggesting moderate discriminatory ability. A PLR > 189.4. demonstrated a sensitivity of 65.1%, a specificity of 76.1%. These ROC curve findings concerning primary outcome are visually represented in

Figure 1.

3.3. Univariate Analysis: Initial Assessment of Predictors

The univariable Cox regression analysis, summarized in

Table 2, confirmed the significant association between several classical clinical predictors and adverse outcomes. Advanced age, CCI greater than 2, delayed surgical intervention, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated NT-proBNP levels were all associated with increased mortality, higher likelihood of ICU admission, and longer hospital stay. Importantly, particular emphasis was placed on the prognostic impact of inflammatory biomarkers. Patients with an NLR greater than 7.2 had a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.38 (95% CI 2.01–2.75; p=0.001) for 30-day mortality, corresponding to a 138% increase in the risk compared to those with lower NLR values. The risk of 90-day mortality was similarly elevated by 92% (HR 1.92; 95% CI 1.23–2.13; p=0.003) among patients with elevated NLR. In terms of postoperative outcomes, an NLR above the established threshold was associated with a 152% increased likelihood of requiring ICU admission (HR 2.52; 95% CI 2.21–2.87; p=0.0023) and a 97% increase in the risk of prolonged hospitalization (HR 1.97; 95% CI 1.23–2.17; p=0.002). The PLR demonstrated a similar predictive trend. Patients with a PLR greater than 189.4 had a 99% higher risk of 30-day mortality (HR 1.99; 95% CI 1.73–2.31; p=0.002) and a 78% higher risk of 90-day mortality (HR 1.78; 95% CI 1.43–1.99; p=0.002). An elevated PLR was also associated with a 65% increased likelihood of ICU admission (HR 1.65; 95% CI 1.23–1.89; p=0.0021) and a 54% increased risk of a hospital stay exceeding 15 days (HR 1.54; 95% CI 1.21–1.78; p=0.0052).

3.4. Multivariable Analysis: NLR and PLR as Independent Predictors

Multivariable Cox regression analyses, presented in

Table 3, were conducted to adjust for confounders including age, comorbidity burden, timing of surgery, hypoalbuminemia, and NT-proBNP levels. In these models, both NLR and PLR retained their significance as independent predictors of mortality. An NLR greater than 7.2 remained associated with a 98% increased risk of 1-year mortality (HR 1.98; 95% CI 1.73–2.15; p=0.001) and a 95% higher risk of overall mortality across the study period (HR 1.95; 95% CI 1.27–2.23; p=0.003). Similarly, a PLR above 189.4 independently predicted an 81% increase in 1-year mortality risk (HR 1.81; 95% CI 1.61–2.23; p=0.032) and a 68% increase in total mortality risk (HR 1.68; 95% CI 1.29–1.83; p=0.029). As expected, traditional clinical predictors also demonstrated robust independent associations. A CCI greater than 2 conferred a ten-fold increase in the risk of 1-year mortality (HR 10.24; 95% CI 7.94–11.45; p<0.0001), and hypoalbuminemia was associated with a four-fold increase (HR 4.23; 95% CI 2.59–4.16; p=0.0043). Delayed surgery and elevated NT-proBNP levels were similarly confirmed as independent risk factors for adverse outcomes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Background

Fractures of the hip among the elderly are characterized by severe morbidity, longer hospital stays, and elevated mortality rates and are thus of paramount interest for optimizing management strategies and outcomes [

1,

7,

16]. Classical factors predicting a poorer prognosis following hip fracture have included advanced age, comorbidity quantified by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), hypoalbuminemia, and markers of cardiac impairment such as NT-proBNP [

7]. These factors have been thoroughly tested by the literature [

16]. In the past few years, the role of background inflammatory response as a predictive factor gained growing attention [

17]. Of the reported biomarkers, the NLR and PLR have appeared of interest as markers due to the fact that they reflect both innate immunity activation and adaptive immunity depression, mechanisms implied to be implicated in frailty, healing failure, and postoperative complications [

18]. Studies have consistently shown that increased NLR and PLR values are correlated with poorer outcomes across different clinical conditions such as those undergoing cancer surgery, those suffering from cardiovascular disease and sepsis [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Their utility as predictors in the specific context of hip fracture surgery among elderly patients has, however, remained inadequately investigated [

14]. Particularly, few studies have examined the independent contribution of these markers to short- and long-term mortality and the necessity for intensive care unit admission and hospital length of stay, the most relevant endpoints for both clinicians and the health system [

16,

19,

20]. Their availability, affordability, and fast turnaround time from routine laboratory tests confirm the predictive value of NLR and PLR as a means by which clinicians could have simple tools for optimizing preoperative risk assessment and individualization of the postoperative management.

4.2. Our Findings

This retrospective cohort study evaluated the prognostic value of admission neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery, with particular attention to 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year mortality, need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and prolonged hospital stay. While confirming the established relevance of factors such as age, comorbidity burden, surgical delay, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated NT-proBNP levels, our analysis highlighted the independent and strong association of elevated NLR and PLR values with adverse clinical outcomes. Univariable analysis showed that an NLR greater than 7.2 was significantly associated with increased risks of 30-day mortality (HR 2.38), 90-day mortality (HR 1.92), ICU admission (HR 2.52), and prolonged hospitalization (HR 1.97). Similarly, a PLR above 189.4 predicted poor outcomes, albeit with slightly lower hazard ratios. Multivariable Cox regression models, adjusted for key confounders, confirmed the independent prognostic significance of both markers for 1-year and overall mortality. Our findings suggest that elevated NLR and PLR are not merely byproducts of pre-existing disease but reflect active pathophysiological processes that adversely influence postoperative recovery and survival. A heightened neutrophilic response may drive catabolism, endothelial dysfunction, and impaired healing, while lymphopenia may signal immunosuppression and increased susceptibility to postoperative complications [

12,

18]. Likewise, an elevated PLR may indicate a prothrombotic and immunologically imbalanced state known to compromise outcomes after major orthopedic interventions [

13,

14]. Importantly, the prognostic impact of elevated NLR and PLR was comparable to that of established markers such as hypoalbuminemia and NT-proBNP, reinforcing the clinical significance of systemic inflammation in this setting. Given the rapid, cost-effective availability of NLR and PLR at admission, incorporating these indices into existing risk models could enhance early identification of high-risk patients and inform targeted perioperative management strategies. Optimal cut-off values for NLR and PLR were determined through univariable and ROC curve analyses, yielding thresholds of 7.2 and 189.4, respectively. The AUC for NLR was 0.78 (95% CI 0.66–0.81), demonstrating good discriminatory power, with a sensitivity of 69.7% and a specificity of 85.4%. The AUC for PLR was 0.73 (95% CI 0.61–0.79), indicating moderate discriminatory ability, with a sensitivity of 65.1% and a specificity of 76.1%. While these results underscore the strong predictive performance of NLR, and to a lesser extent PLR, further validation in larger, prospective cohorts is necessary to confirm these cut-offs and extend their applicability across broader clinical contexts.

4.3. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results of our study. First, its retrospective, single-center design inherently introduces potential biases related to data completeness, selection, and unmeasured confounders. Although multiple imputation techniques and rigorous multivariable adjustments were employed, residual confounding cannot be entirely excluded. Second, while NLR and PLR were measured at the time of emergency department admission, dynamic changes in these markers over the perioperative period were not assessed. It is possible that serial measurements might provide even greater prognostic information compared to single time-point assessments. Third, differences in laboratory techniques, patient characteristics, and healthcare delivery systems could affect the reproducibility of our findings. Lastly, cause-specific mortality was not distinguished from all-cause mortality in our study, which might limit the ability to attribute death directly to surgical complications or systemic decompensation. Despite these limitations, the consistency, strength, and clinical plausibility of the associations observed support the robustness of our conclusions and provide a compelling rationale for future prospective studies focusing on the role of systemic inflammation in postoperative outcomes among elderly hip fracture patients.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that elevated NRL and PRL at admission are powerful, independent predictors of short-term and long-term adverse outcomes in elderly patients undergoing surgery for hip fractures. While traditional risk factors such as age, comorbidity burden, nutritional status, and cardiac function remain essential components of risk assessment, the addition of simple, inexpensive inflammatory markers such as NLR and PLR could substantially enhance prognostic stratification. NLR and PLR have the potential to be incorporated into routine clinical practice to guide perioperative management, optimize resource allocation, and ultimately improve patient outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AP,GR.; methodology, AP, MP.; software, AP, MP.; validation, FM, LM, FLG; formal analysis, GR, MP.; investigation, AP, FM resources, AF, FM, LM.; data curation, AF, FM, LM writing—original draft preparation, AP, GR.; writing—review and editing, LM, FM.; visualization, AF, LM supervision, FLG.; project administration FLG.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments. Following extensive consultation with the internal departmental Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Fondazione Casa Sollievo Della Sofferenza, IRCSS, and in consideration of the retrospective, non-interventional nature of the study, as well as the fact that all patients received treatment in accordance with the standard of care defined by our institution, formal ethical committee approval was deemed unnecessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for the scientific use of anonymized clinical data was obtained in compliance with institutional regulations and the guidelines of the Italian Data Protection Authority. All patient data were fully anonymized to safeguard confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional data protection policies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for the purposes of language editing, specifically to review grammar and assist in the final stylistic and structural revisions of the manuscript. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| LoS |

Length of Stay |

| NLR |

Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| NT-proBNP |

N-terminal pro–B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| PLR |

Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

References

- Vitiello R, Perisano C, Covino M, et al. Euthyroid sick syndrome in hip fractures: Valuation of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone axis. Injury. 2020;51 Suppl 3:S13-S16. [CrossRef]

- Maccagnano G, Maruccia F, Rauseo M, Noia G, Coviello M, Laneve A, Quitadamo AP, Trivellin G, Malavolta M, Pesce V. Direct Anterior versus Lateral Approach for Femoral Neck Fracture: Role in COVID-19 Disease. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 16;11, 16, 4785. [CrossRef]

- Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int. 1992, 2, 285-289. [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi A, Delhougne G. Incidence and Economic Burden of Intertrochanteric Fracture: A Medicare Claims Database Analysis. JB JS Open Access. 2019;4, 1, e0045. [CrossRef]

- Xu BY, Yan S, Low LL, Vasanwala FF, Low SG. Predictors of poor functional outcomes and mortality in patients with hip fracture: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:568. [CrossRef]

- Barceló M, Torres OH, Mascaró J, Casademont J. Hip fracture and mortality: study of specific causes of death and risk factors. Arch Osteoporos. 2021;16:15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang BF, Ren SB, Wang MX. The Predictive Value of Serum NT-proBNP on One-Year All-Cause Mortality in Geriatrics Hip Fracture: A Cohort Study. Cureus. 2023;15, 9, e45398. [CrossRef]

- Vitiello R, Smimmo A, Matteini E, et al. Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) and Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR) Are Predictors of Good Outcomes in Surgical Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infections of Lower Limbs: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12, 9, 867. [CrossRef]

- Tuncay A, Yilmaz Y, Baran O, Kelesoglu S. Inflammatory Markers and Saphenous Vein Graft Stenosis: Insights into the Use of Glucose-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Marker. J Clin Med. 2025;14, 8, 2634. [CrossRef]

- Drugescu A, Gavril RS, Zota IM, et al. Inflammatory and Fibrosis Parameters Predicting CPET Performance in Males with Recent Elective PCI for Chronic Coronary Syndrome. Life (Basel). 2025;15, 4, 510. [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro MG, Ferragina F, Staglianò S, Arrotta A, D’Amico M, Barca I. Prognostic Value of Systemic Inflammatory Markers in Malignant Tumors of Minor Salivary Glands: A Retrospective Analysis of a Single Center. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17, 8, 1373. [CrossRef]

- Adamescu AI, Tilișcan C, Stratan LM, et al. Decoding Inflammation: The Role of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Predicting Critical Outcomes in COVID-19 Patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61, 4, 634. [CrossRef]

- Donghia R, Carr BI, Yilmaz S. Factors relating to Tumor size and survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: significance of PLR, PVT and albumin. Oncology. [CrossRef]

- Pan WG, Chou YC, Wu JL, Yeh TT. Impact of hematologic inflammatory markers on the prognosis of geriatric hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29, 1, 609. [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13 Suppl 1:S31-S34. [CrossRef]

- Wang ZC, Jiang W, Chen X, Yang L, Wang H, Liu YH. Systemic immune-inflammation index independently predicts poor survival of older adults with hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21, 1, 155. [CrossRef]

- Wilson JM, Boissonneault AR, Schwartz AM, Staley CA, Schenker ML. Frailty and malnutrition are associated with inpatient postoperative complications and mortality in hip fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33, 3, 143–8.

- Wang R, Wen X, Huang C, Liang Y, Mo Y, Xue L. Association between inflammation-based prognostic scores and in-hospital outcomes in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1199–206.

- Kolhe SN, Holleyman R, Chaplin A, et al. Association between markers of inflammation and outcomes after hip fracture surgery: analysis of routinely collected electronic healthcare data. BMC Geriatr. 2025;25, 1, 274. [CrossRef]

- Kilinc M, Çelik E, Demir I, Aydemir S, Akelma H. Association of Inflammatory and Metabolic Markers with Mortality in Patients with Postoperative Femur Fractures in the Intensive Care Unit. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61, 3, 538. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).