Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Conceptualizing Sexual Health

Overview of Research on Orgasms

Sexual Health Correlates

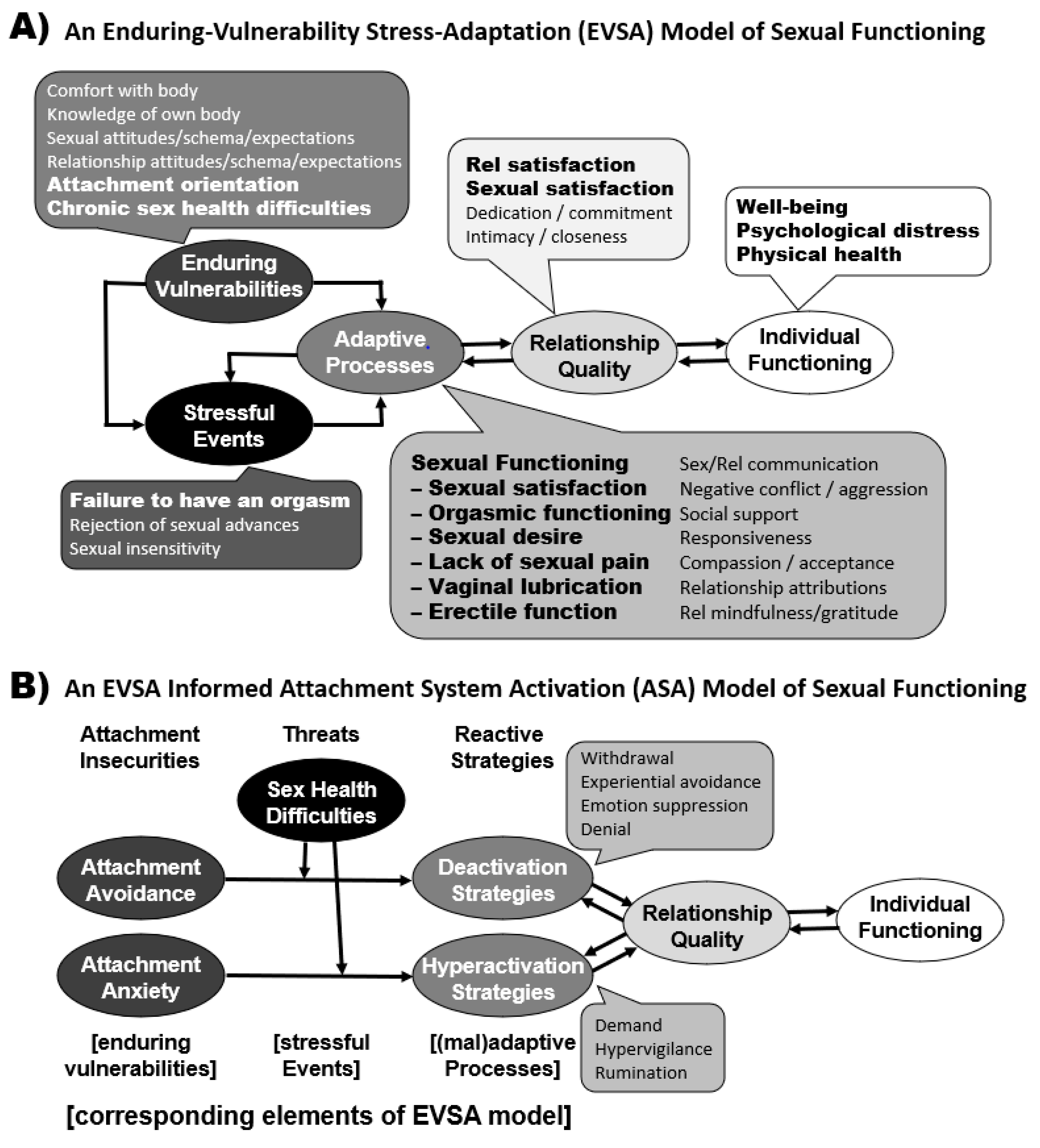

Organizing Conceptual Framework

Previous Reviews

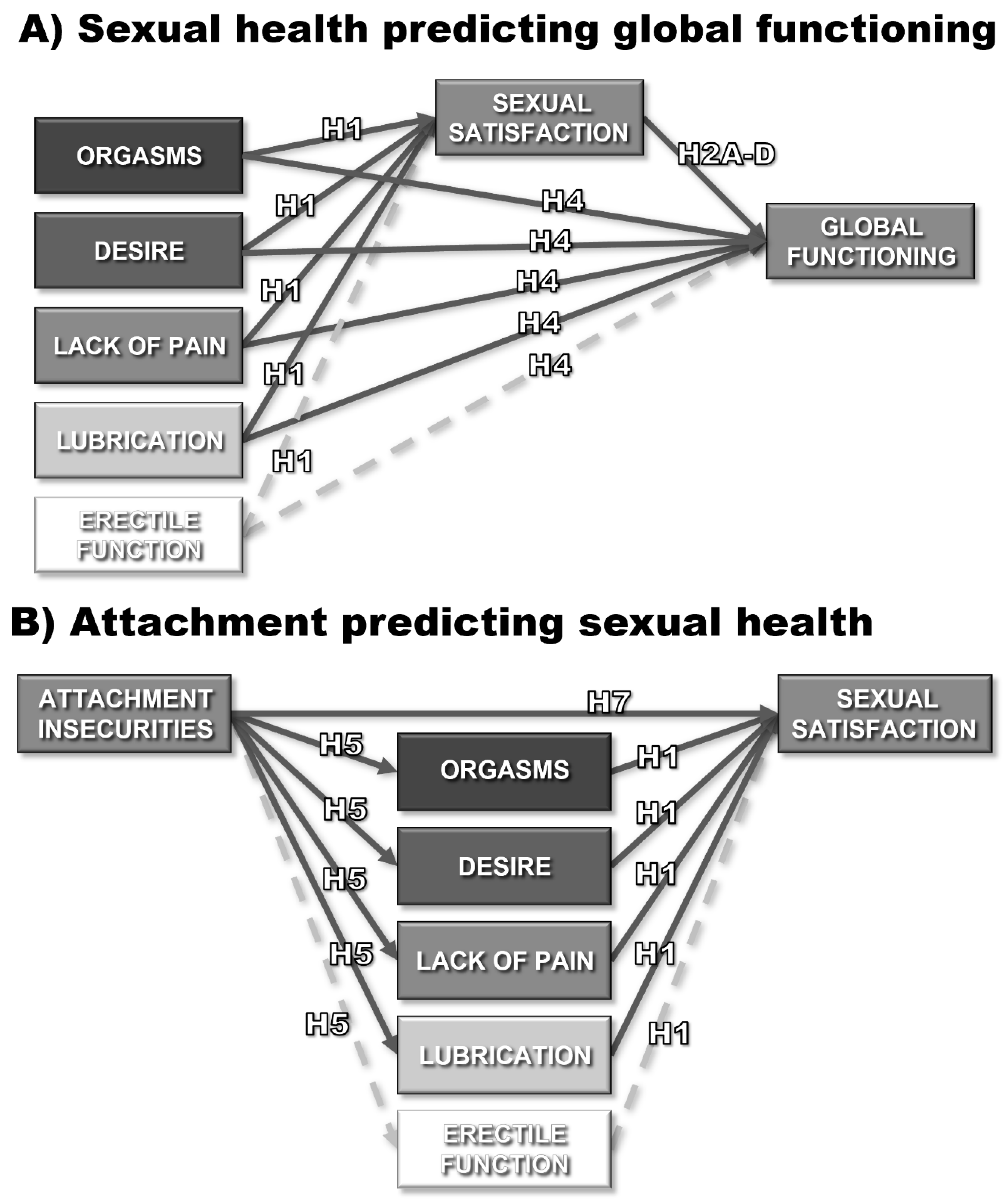

Present Meta-Analysis

Method

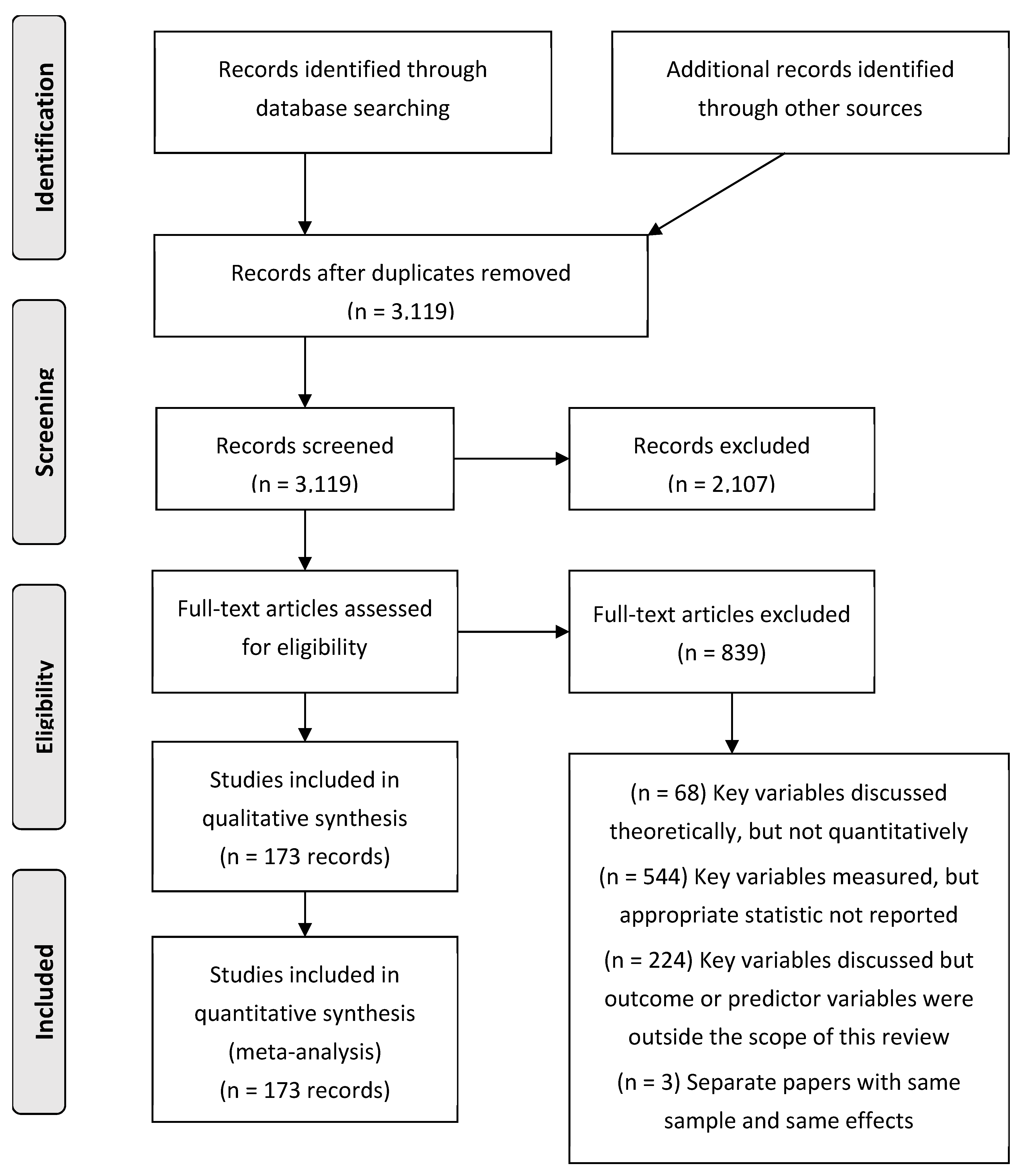

Selection of Records

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- written in English, Spanish, or Polish;

- (2)

- consisted of human participants only;

- (3)

- contained independent samples (i.e., providing effects within a group of participants that have not been previously published in other articles out of that sample);

- (4)

- included a measure of orgasms (i.e., orgasm consistency, difficulty, frequency, or general ability/inability to have an orgasm) resulting from sexual intercourse;

- (5)

- included a measure of individual functioning (i.e., attachment, depression, distress, life satisfaction, loneliness, psychological well-being, negative affect, stress, well-being, vitality) or relationship functioning (i.e., maintenance behavior, relationship conflict, relationship longevity, relationship quality, relationship satisfaction, relationship stability, sexual satisfaction, support);

- (6)

- provided statistical indices of the association between orgasms and individual or relationship functioning within the record (if relevant variables were measured but an effect of their association was not reported, authors of the record were contacted via repeated emails in an attempt to collect the relevant statistic);

- (7)

- reported an effect size specifically either in the form of a Pearson’s r correlation coefficient, a standardized regression coefficient, or other statistical value from which a Pearson’s r correlation coefficient or standardized regression coefficient could be computed (e.g., a 2 by 2 chi-squared, a Cohen’s d; see Method Statistical Analyses for transformation formulas used).

Data Extraction and Coding Procedure

Classification of Variable Domains

Statistical Analyses

Results

Overview of Records

Meta-Analytic Correlations

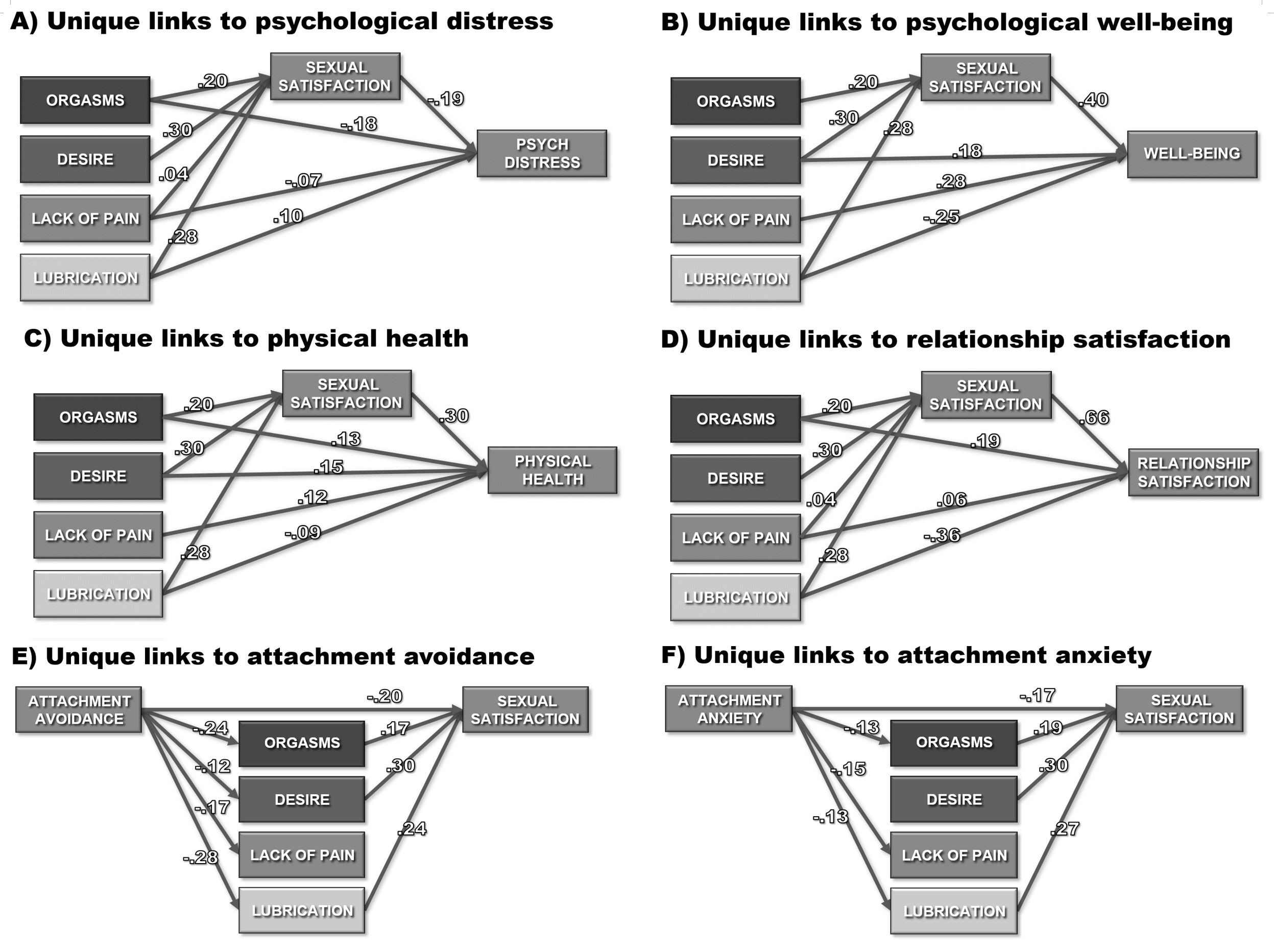

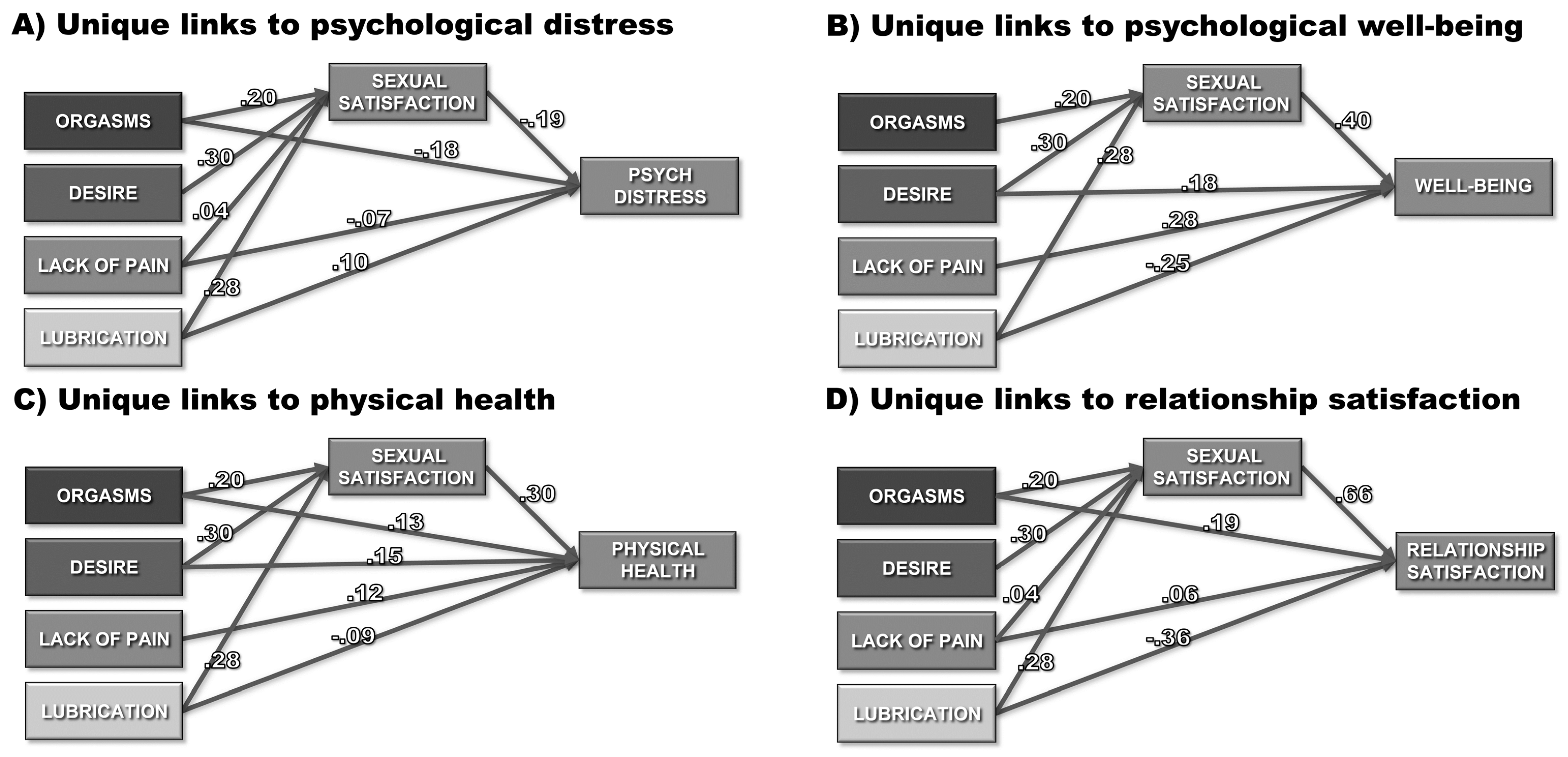

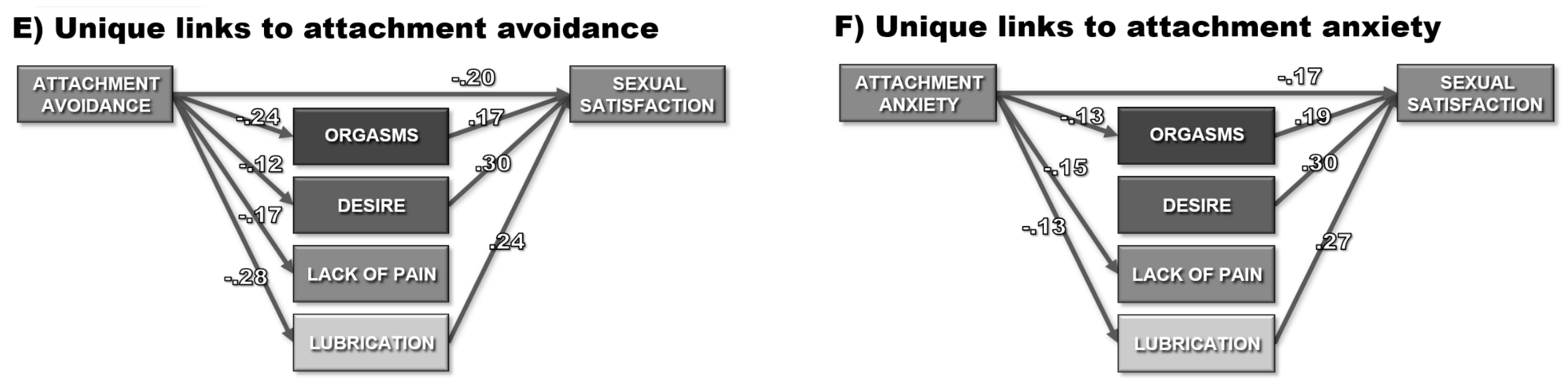

Meta-Analytic Path Analyses

Moderation Effects

Publication Bias

Discussion

Implications

Future Directions

Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

References

- *Abdel-Hamid, I. A. , & Saleh, E. S. (2011). Primary lifelong delayed ejaculation: Characteristics and response to bupropion. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Abedi, P. , Afrazeh, M., Javadifar, N., & Saki, A. (2015). The relation between stress and sexual function and satisfaction in reproductive-age women in Iran: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Abramov, L. A. (1976). Sexual life and sexual frigidity among women developing acute myocardial infarction. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38. [CrossRef]

- *Aerts, L. , Enzlin, P., Verhaeghe, J., Poppe, W., Vergote, I., & Amant, F. (2015). Sexual functioning in women after surgical treatment for endometrial cancer: A prospective controlled study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Adam, F. , De Sutter, P., Day, J., & Grimm, E. (2020). A randomized study comparing video-based mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with video-based traditional cognitive behavioral therapy in a sample of women struggling to achieve orgasm. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Alvisi, S., Baldassarre, M., Lambertini, M., Martelli, V., Berra, M., Moscatiello, S., Marchesini, G., Venturoli, S., & Meriggiola, M. C. (2014). Sexuality and psychopathological aspects in premenopausal women with metabolic syndrome. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11, 2020–2028. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Amicis, L. A. De, Goldberg, D. C., Lopiccolo, J., & Davies, L. (1984). Three-year follow-up of couples evaluated for sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Appa, A. A. , Creasman, J., Brown, J. S., Van Den Eeden, S. K., Thom, D. H., Subak, L. L., & Huang, A. J. (2014). The impact of multimorbidity on sexual function in middle-aged and older women: Beyond the single disease perspective. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, E. A. , England, P., & Fogarty, A. C. K. (2012). Accounting for women’s orgasm and sexual enjoyment in college hookups and relationships. American Sociological Review. [CrossRef]

- *Artune-Ulkumen, B. , Erkan, M. M., Pala, H. G., & Bulbul, Y. B. (2014). Sexual dysfunction in Turkish women with dyspareunia and its impact on the quality of life. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology. [CrossRef]

- *Asselmann, E. , Hoyer, J., Wittchen, H. U., & Martini, J. (2016). Sexual problems during pregnancy and after delivery among women with and without anxiety and depressive disorders prior to pregnancy: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Assimakopoulos, K. , Panayiotopoulos, S., Iconomou, G., Karaivazoglou, K., Matzaroglou, C., Vagenas, K., & Kalfarentzos, F. (2006). Assessing sexual function in obese women preparing for bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Atarodi-Kashani, Z. , Kariman, N., Ebadi, A., Majd, H. A., & Beladi-Moghadam, N. (2017). Sexual function and related factors in Iranian woman with epilepsy. Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy. [CrossRef]

- *Atis, G. , Dalkilinc, A., Altuntas, Y., Atis, A., Gurbuz, C., Ofluoglu, Y., Cil, E., & Caskurlu, T. (2011). Hyperthyroidism: A risk factor for female sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Aubin, S., Berger, R., Heiman, J. R., & Ciol, M. (2008). The association between sexual function, pain, and psychological adaptation of men diagnosed with chronic pelvic pain syndrome type III. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 657–667. [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, J. S. , Harrison, K., Kramer, L., & Yellin, J. (2003). Variety versus timing: Gender differences in college students’ sexual expectations as predicted by exposure to sexually oriented television. Communication Research. [CrossRef]

- *Bakhtiari, A., Basirat, Z., & Nasiri-Amiri, F. (2016). Sexual dysfunction in women undergoing fertility treatment in Iran: prevalence and associated risk factors. Journal of Reproduction & Infertility, 17, 26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4769852/.

- *Barbara, G. , Pifarotti, P., Facchin, F., Cortinovis, I., Dridi, D., Ronchetti, C., Calzolari, L., & Vercellini, P. (2016). Impact of mode of delivery on female postpartum sexual functioning: Spontaneous vaginal delivery and operative vaginal delivery vs cesarean section. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Barrientos, J. E. , & Páez, D. (2006). Psychosocial variables of sexual satisfaction in Chile. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Battaglia, C., Battaglia, B., Mancini, F., Nappi, R. E., Paradisi, R., & Venturoli, S. (2011). Moderate alcohol intake, genital vascularization, and sexuality in young, healthy, eumenorrheic women. A pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8, 2334–2343. [CrossRef]

- *Beaber, T. E., & Werner, P. D. (2009). The relationship between anxiety and sexual functioning in lesbians and heterosexual women. Journal of Homosexuality, 56, 639–654. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. , Steer, R.A., & Brown, G.K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation.

- *Berenguer, C. , Rebôlo, C., & Costa, R. M. (2019). Interoceptive awareness, alexithymia, and sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Berman, J. R. , Berman, L. A., Lin, H., Flaherty, E., Lahey, N., & Cantey-Kiser, J. (2011). Effect of sildenafil on subjective and physiologic parameters of the female sexual response in women with sexual arousal disorder. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Blair, K. L. , Cappell, J., & Pukall, C. F. (2018). Not all orgasms were created equal: Differences in frequency and satisfaction of orgasm experiences by sexual activity in same-sex versus mixed-sex relationships. Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Bodenmann, G., Atkins, D. C., Schär, M., & Poffet, V. (2010). The association between daily stress and sexual activity. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 271–279. [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- *Borissova, A. M. , Kovatcheva, R., Shinkov, A., & Vukov, M. (2001). A study of the psychological status and sexuality in middle-aged Bulgarian women: Significance of the hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Maturitas. [CrossRef]

- Bouhlel, S. , Derbel, C. H., Nakhli, J., Bellazreg, F., Meriem, H. Ben, Omezzine, A., & Hadj, B. Ben. (2017). Sexual dysfunction in Tunisian patients living with HIV. Sexologies 26, e11–e16. [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Sadness and depression. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge.

- Brezsnyak, M. , & Whisman, M. A. (2004). Sexual desire and relationship functioning: The effects of marital satisfaction and power. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. (2006). Penile—vaginal intercourse is better: Evidence trumps ideology. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. (2007). Vaginal orgasm is associated with better psychological function. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. (2010). The relative health benefits of different sexual activities. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. (2017). Evaluation of female orgasmic disorder. In W. W. Ishak (Ed.), Textbook of Clinical Sexual Medicine (pp. 203–218). Springer, Cham.

- Brody, S., & Costa, R. M. (2008). Vaginal orgasm is associated with less use of immature psychological defense mechanisms. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 1167–1176. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. , & Costa, R. M. (2009). Satisfaction (sexual, life, relationship, and mental health) is associated directly with penile-vaginal intercourse, but inversely with other sexual behavior frequencies. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. , Costa, R. M., Klapilová, K., & Weiss, P. (2018). Specifically penile-vaginal intercourse frequency is associated with better relationship satisfaction: A commentary on Hicks, McNulty, Meltzer, and Olson (2016). Psychological science. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S. , Houde, S., & Hess, U. (2010). Greater tactile sensitivity and less use of immature psychological defense mechanisms predict women’s penile-vaginal intercourse orgasm. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Brody, S., & Weiss, P. (2010). Vaginal orgasm is associated with vaginal (not clitoral) sex education, focusing mental attention on vaginal sensations, intercourse duration, and a preference for a longer penis. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 2774–2781. [CrossRef]

- *Brody, S. , & Weiss, P. (2011). Simultaneous penile-vaginal intercourse orgasm is associated with satisfaction (sexual, life, partnership, and mental health). Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Brotto, L. , Atallah, S., Johnson-Agbakwu, C., Rosenbaum, T., Abdo, C., Byers, E. S., Graham, C., Nobe, P., & Wylie, K. (2016). Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. The journal of sexual medicine.

- Brotto, L. A., Heiman, J. R., Goff, B., Greer, B., Lentz, G. M., Swisher, E., Tamimi, H., & Van Blaricom, A. (2008). A Psychoeducational Intervention for Sexual Dysfunction in Women with Gynecologic Cancer. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 317–329. [CrossRef]

- *Burleson, M. H. , Trevathan, W. R., & Todd, M. (2007). In the mood for love or vice versa? Exploring the relations among sexual activity, physical affection, affect, and stress in the daily lives of mid-aged women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Burri, A. (2017). Sexual sensation seeking, sexual compulsivity, and gender identity and its relationship with sexual functioning in a population sample of men and women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine.

- *Burri, A. , Hilpert, P., & Spector, T. (2015). Longitudinal evaluation of sexual function in a cohort of pre- and postmenopausal women. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Burri, A., Spector, T., & Rahman, Q. (2013). A discordant monozygotic twin approach to testing environmental influences on sexual dysfunction in women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 961–972. [CrossRef]

- *Cagnacci, A., Venier, M., Xholli, A., Paglietti, C., & Caruso, S. (2020). Female sexuality and vaginal health across the menopausal age. Menopause, 27, 14-19. [CrossRef]

- *Canat, M., Canat, L., Öztürk, F. Y., Eroğlu, H., Atalay, H. A., & Altuntaş, Y. (2016). Vitamin D 3 deficiency is associated with female sexual dysfunction in premenopausal women. International Urology and Nephrology, 48, 1789-1795. [CrossRef]

- *Carmen, R. A. (2014). Untangling the complexities of female sexuality: A mixed approach (Master’s thesis, State University of New York at New Paltz, New Paltz, New York). http://hdl.handle.net/1951/63469.

- Carmichael, M. S. , Humbert, R., Dixen, J., Palmisano, G., Greenleaf, W., & Davidson, J. M. (1987). Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. [CrossRef]

- *Carrobles, J. A., Guadix, M. G., & Almendros, C. (2011). Funcionamiento sexual, satisfacción sexual y bienestar psicológico y subjetivo en una muestra de mujeres españolas. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 27, 27-34. https://revistas.um.es/analesps/article/view/113441.

- Carter, C. S. (1992). Oxytocin and sexual behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S., Cicero, C., Romano, M., Presti, L. Lo, Ventura, B., & Malandrino, C. (2012). Tadalafil 5 mg daily treatment for type 1 diabetic premenopausal women affected by sexual genital arousal disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9, 2057–2065. [CrossRef]

- *Castellini, G., Mannucci, E., Mazzei, C., Lo Sauro, C., Faravelli, C., Rotella, C. M., Maggi, M., & Ricca, V. (2010). Sexual function in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 3969–3978. [CrossRef]

- Celikel, E. , Ozel-kizil, E. T., Akbostanci, M. C., & Cevik, A. (2008). Assessment of sexual dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A case–control study. European Journal of Neurology. [CrossRef]

- *Ceyhan, O. , Ozen, B., Simsek, N., & Dogan, A. (2019). Sexuality and marital adjustment in women with hypertension in Turkey: how culture affects sex. Journal of Human Hypertension. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, S. B. , Francisco, M., & van Anders, S. M. (2019). When orgasms do not equal pleasure: Accounts of “bad” orgasm experiences during consensual sexual encounters. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Chang, S., Ho, H., Chen, K., Shyu, M., Huang, L., & Lin, W. (2012). Depressive symptoms as a predictor of sexual function during pregnancy. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9, 2582–2589. [CrossRef]

- *Chang, S. R. , Yang, C. F., & Chen, K. H. (2019). Relationships between body image, sexual dysfunction, and health-related quality of life among middle-aged women: A cross-sectional study. Maturitas. [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, S. , Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Schick, V., Dodge, B., Baldwin, A., Van Der Pol, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2017). The year’s best: Interpersonal elements of bisexual women’s most satisfying sexual experiences in the past year. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- *Cheng, J. Y. W., Ng, E. M. L., & Ko, J. S. N. (2007). Depressive symptomatology and male sexual functions in late life. Journal of Affective Disorders, 104, 225–229. [CrossRef]

- *Chivers, M. L. , Pittini, R., Grigoriadis, S., Villegas, L., & Ross, L. E. (2011). The relationship between sexual functioning and depressive symptomatology in postpartum women: A pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, H., Savas, M., Gulum, M., Yeni, E., Verit, A., & Topal, U. (2011). Evaluation of sexual function in men with orchialgia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 631–634. [CrossRef]

- *Cohen, D. L. , & Belsky, J. (2008). Avoidant romantic attachment and female orgasm: Testing an emotion-regulation hypothesis. Attachment and Human Development. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1992). A Power Primer. Psychological Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385-396. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1954). The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. [CrossRef]

- *Conroy, K. (2018). The relationship between sexual activity and sexual function in breast and gynecologic cancer patients during adjuvant chemotherapy (Master’s thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio). http://hdl.handle.net/1811/84805.

- *Constantine, S. (2017). Women’s sexual fantasies in context: The emotional content of sexual fantasies, psychological and interpersonal distress, and satisfaction in romantic relationships (Doctoral dissertation, City University of New York, New York City, New York). https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2162.

- Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, E. B. , Fenigstein, A., & Fauber, R. L. (2014). The faking orgasm scale for women: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (2009). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed). Russell Sage Foundation.

- *Costa, R. M. , & Brody, S. (2007). Women’s relationship quality is associated with specifically penile-vaginal intercourse orgasm and frequency. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Costa, R. M., & Brody, S. (2011). Anxious and avoidant attachment, vibrator use, anal sex, and impaired vaginal orgasm. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8, 2493–2500. [CrossRef]

- Costa, R. M. , & Brody, S. (2012a). Greater resting heart rate variability is associated with orgasms through penile–vaginal intercourse, but not with orgasms from other sources. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Costa, R. M., Pestana, J., Costa, D., & Wittmann, M. (2016). Altered states of consciousness are related to higher sexual responsiveness. Consciousness and Cognition, 42, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- *Dashti, S., Latiff, L. A., Hamid, H. A., Sani, S. M., Akhtari-Zavare, M., Bakar, A., Sabiri, N. A., Ismail, M., & Esfehani, A. J. (2016). Sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome in Malaysia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 17, 3747-3751. http://journal.waocp.org/article_33048.html.

- *Davidson, J. K. , & Hoffman, L. E. (1986). Sexual fantasies and sexual satisfaction: An empirical analysis of erotic thought. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L. , & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘‘what’’ and ‘‘why’’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11. [CrossRef]

- *de Jong, D. C. (2016). Validation of a measure of implicit sexual desire for romantic partners (Doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York). https://search.proquest.com/docview/1823257882?pq-origsite=gscholar.

- *de Lucena, B. B. , & Abdo, C. H. N. (2014). Personal factors that contribute to or impair women’s ability to achieve orgasm. International Journal of Impotence Research. [CrossRef]

- *de Oliveira Ferro, J. K. , Lemos, A., da Silva, C. P., de Paiva Lima, C. R. O., Raposo, M. C. F., de Aguiar Cavalcanti, G., & de Oliveira, D. A. (2019). Predictive Factors of Male Sexual Dysfunction After Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Spine. [CrossRef]

- Delavierre, D. (2008). Diagnosis of male anorgasmia. Progres en urologie: journal de l’Association francaise d’urologie et de la Societe francaise d’urologie, 18, F8-10. https://europepmc.org/article/med/18773846.

- *Demir, S. E., Rezvani, A., & Ok, S. (2013). Assessment of sexual functions in female patients with ankylosing spondylitis compared with healthy controls. Rheumatology International, 33, 57-63. [CrossRef]

- *Denes, A. (2012). Pillow talk: Exploring disclosures after sexual activity. Western Journal of Communication. [CrossRef]

- *Denes, A. (2018). Toward a post-sex disclosures model: Exploring the associations among orgasm, self-disclosure, and relationship satisfaction. Communication Research. [CrossRef]

- Denes, A. , Horan, S. M., & Bennett, M. (2019). “Faking it” and affectionate communication: Exploring the authenticity of orgasm and relational quality indicators. Personality and Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L. R. (1997). The Derogatis Interview for Sexual Functioning (DISF/DISF-SR): An introductory report. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 23. [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L. R. , & Melisaratos, N. (1979). The DSFI: A multidimensional measure of sexual functioning. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 5. [CrossRef]

- *Dèttore, D. , Pucciarelli, M., & Santarnecchi, E. (2013). Anxiety and female sexual functioning: An empirical study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. [CrossRef]

- *Dissiz, M. (2018). The effect of heroin use disorder on the sexual functions of women. Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences. [CrossRef]

- *Dogan, V. B., Dagdeviren, H., Dirican, A., Dirican, A. C., Tutar, N. K., Yayla, V. A., & Cengiz, H. (2017). Hormonal effect on the relationship between migraine and female sexual dysfunction. Neurological Sciences, 38, 1651–1655. [CrossRef]

- Dosch, A. , Ghisletta, P., & Van der Linden, M. (2016). Body image in dyadic and solitary sexual desire: The role of encoding style and distracting thoughts. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Du, J. , Ruan, X., Gu, M., Bitzer, J., & Mueck, A. O. (2016). Prevalence of and risk factors for sexual dysfunction in young Chinese women according to the Female Sexual Function Index: An internet-based survey. European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. [CrossRef]

- *Duits, A. , Van Oirschot, N., Van Oostenbrugge, R. J., & Van Lankveld, J. (2009). The relevance of sexual responsiveness to sexual function in male stroke patients. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Dunkley, C. R. , Dang, S. S., Chang, S. C. H., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2016). Sexual functioning in young women and men: Role of attachment orientation. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Dunn, K. M. , Croft, P. R., & Hackett, G. I. (1999). Association of sexual problems with social, psychological, and physical problems in men and women: a cross sectional population survey. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. [CrossRef]

- Duval, S. , & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. [CrossRef]

- *Dyar, C., Newcomb, M. E., Mustanski, B., & Whitton, S. W. (2019). A structural equation model of sexual satisfaction and relationship functioning among sexual and gender minority individuals assigned female at birth in diverse relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, online first, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- *Eaton, L., Kueck, A., Maksut, J., Gordon, L., Metersky, K., Miga, A., Brewer, M., Siembida, E., & Bradley, A. (2017). Sexual health, mental health, and beliefs about cancer treatments among women attending a gynecologic oncology clinic. Sexual Medicine, 5, e175-e183. [CrossRef]

- Egger, M. , Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal. [CrossRef]

- *Eichel, E. W. , De Simone Eichel, J., & Kule, S. (1988). The technique of coital alignment and its relation to female orgasmic response and simultaneous orgasm. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Ellero, J. (2019). Altered states of consciousness, absorption, and sexual responsiveness (Master’s thesis, ISPA—Instituto Universitário, Lisbon, Portugal). http://hdl.handle.net/10400.12/7173.

- *Ellsworth, R. M. , & Bailey, D. H. (2013). Human female orgasm as evolved signal: A test of two hypotheses. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Fabre, L. F. , Clayton, A. H., Smith, L. C., Goldstein, I. M., & Derogatis, L. R. (2013). Association of major depression with sexual dysfunction in men. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 25, 308–318. [CrossRef]

- *Fabre, L. F. , & Smith, L. C. (2012). The effect of major depression on sexual function in women. Journal of Sexual Medicine 9, 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Fahs, B. (2014). Coming to power: Women’s fake orgasms and best orgasm experiences illuminate the failures of (hetero) sex and the pleasures of connection. Culture, Health & Sexuality. [CrossRef]

- Fahs, B. , & Plante, R. (2017). On ‘good sex’ and other dangerous ideas: women narrate their joyous and happy sexual encounters. Journal of Gender Studies. [CrossRef]

- *Fan, X. , Henderson, D. C., Chiang, E., Briggs, L. B. N., Freudenreich, O., Evins, A. E., Cather, C., & Goff, D. C. (2007). Sexual functioning, psychopathology and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, F. , Pakgohar, M., Mirmohamadali, M., & Mahmoodi, M. (2008). Effect of sexual education on sexual health in Iran. Sex Education. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. , & Larsen, K. (2014). Sexual Dysfunction. In S. Richards & M. W. O’Hara (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity (pp. 218–235). Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

- Fisher, W. A. , Rosen, R. C., Eardley, I., Sand, M., & Goldstein, I. (2005). Sexual experience of female partners of men with erectile dysfunction: The female experience of men’s attitudes to life events and sexuality (FEMALES) study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K. E. , Lin, L., Cyranowski, J. M., Reeve, B. B., Reese, J. B., Jeffery, D. D., Smith, A. W., Porter, L. S., Dombeck, C. B., Burner, D. W., Keefe, F. J., & Weinfurt, K. P. (2013). Development of the NIH PROMIS® sexual function and satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Forbes, M. K. , Baillie, A. J., & Schniering, C. A. (2016). Should sexual problems be included in the internalizing spectrum? A comparison of dimensional and categorical models. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Fragla, E. , Privitera, S., Giardina, R., Di Rosa, A., Russo, G. I., Favilla, V., Caramma, A., Patti, F., Cimino, S., & Morgia, G. (2014). Determinants of sexual impairment in multiple sclerosis in male and female patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction: Results from an Italian cross-sectional study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R. C. , Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- *Frederick, D. A. , Lever, J., Gillespie, B. J., & Garcia, J. R. (2017). What keeps passion alive? Sexual satisfaction is associated with sexual communication, mood setting, sexual variety, oral sex, orgasm, and sex frequency in a national U.S. study. Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D. A. John, H. K. S., Garcia, J. R., & Lloyd, E. A. (2018). Differences in orgasm frequency among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual men and women in a U.S. national sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior 47, 273–288. [CrossRef]

- Gades, N. M., Jacobson, D. J., McGree, M. E., Sauver, J. L. S., Lieber, M. M., Nehra, A., Girman, C. J., Klee, G. G., & Jacobsen, S. J. (2008). The associations between serum sex hormones, erectile function, and sex drive: the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status among Men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 2209-2220.

- Galinsky, A. M. (2012). Sexual touching and difficulties with sexual arousal and orgasm among U.S. older adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Gallup, G. G. , Ampel, B. C., Wedberg, N., & Pogosjan, A. (2014). Do orgasms give women feedback about mate choice? Evolutionary Psychology. [CrossRef]

- *Gracia, C. R. , Freeman, E. W., Sammel, M. D., Lin, H., & Mogul, M. (2007). Hormones and sexuality during transition to menopause. Obstetrics & Gynecology. [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, J. R. , & Kringelbach, M. L. (2012). The human sexual response cycle: Brain imaging evidence linking sex to other pleasures. Progress in Neurobiology. [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, J. R. , Reinders, A. S., Paans, A. M., Renken, R., & Kortekaas, R. (2009). Men versus women on sexual brain function: prominent differences during tactile genital stimulation, but not during orgasm. Human Brain Mapping. [CrossRef]

- *Gewirtz-Meydan, A. (2017). Why do narcissistic individuals engage in sex? Exploring sexual motives as a mediator for sexual satisfaction and function. Personality and Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- *Gewirtz-Meydan, A. , & Finzi-Dottan, R. (2018). Sexual satisfaction among couples: The role of attachment orientation and sexual motives. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, F. G. , & Rush, C. L. (2010). Self-esteem and sexuality: An exploration of differentiation and attachment. Self-esteem across the lifespan: Issues and interventions.

- *Gomes, A. L. Q. , & Nobre, P. (2012). The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-15): Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Goodman, D. L. (2011). Associations of attachment style and reasons to pretend orgasm; development and validation of reasons to pretend orgasm measure in a relational context (Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas). http://hdl.handle.net/1808/13008.

- Goodman, D. L. , Gillath, O., & Haj-Mohamadi, P. (2017). Development and validation of the pretending orgasm reasons measure. Archives of Sexual Behavior 46, 1973–1991.

- Graham, C. A. (2014). Orgasm Disorders in Women. In Y. M. Binik & K. S. K. Hall (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy (5th ed., pp. 89–111). The Guildford Press.

- *Granata, A. , Tirabassi, G., Pugni, V., Arnaldi, G., Boscaro, M., Carani, C., & Balercia, G. (2013). Sexual dysfunctions in men affected by autoimmune Addison’s disease before and after short-term gluco-and mineralocorticoid replacement therapy. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Grose, R. G. (2016). Critical consciousness and sexual pleasure: Evidence for a sexual empowerment process for heterosexual and sexual minority women (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/61r1d1sm.

- *Gunst, A. , Ventus, D., Kärnä, A., Salo, P., & Jern, P. (2017). Female sexual function varies over time and is dependent on partner-specific factors: A population-based longitudinal analysis of six sexual function domains. Psychological Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Guo, Y. N. , Ng, E. M. L., & Chan, K. (2004). Foreplay, orgasm, and after-play among Shanghai couple and its integrative relation with their marital satisfaction. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Gutsche, M. , & Burri, A. (2017). What women want—An explorative study on women’s attitudes toward sexuality boosting medication in a sample of Swiss women. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Haavio-Mannila, E. , & Kontula, O. (1997). Correlates of increased sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior 26, 399–419. [CrossRef]

- Hangen, F. , Crasta, D., & Rogge, R. D. (2019). Delineating the boundaries between nonmonogamy and infidelity: Bringing consent back into definitions of consensual nonmonogamy with latent profile analysis. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Hangen, F. , & Rogge, R. D. (2021). Focusing the Conceptualization of Erotophilia and Erotophobia on Global Attitudes Toward Sex: Development and Validation of the Sex Positivity-Negativity Scale. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Harte, C. B. , & Meston, C. M. (2012). Recreational use of erectile dysfunction medications and its adverse effects on erectile function in young healthy men: the mediating role of confidence in erectile ability. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Hassan, A. , El-Hadidy, M., El-Deeck, B. S., & Mostafa, T. (2008). Couple satisfaction to different therapeutic modalities for organic erectile dysfunction. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 5, 2381–2391. [CrossRef]

- *Hazewinkel, M. H. , Laan, E. T., Sprangers, M. A., Fons, G., Burger, M. P., & Roovers, J. P. W. (2012). Long-term sexual function in survivors of vulvar cancer: a cross-sectional study. Gynecologic Oncology. [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, D. W. , Hanlon, T. E., & Carpenter Jr, W. T. (1984). The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, S. S. , Dicke, A., & Hendrick, C. (1998). The relationship assessment scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 15, 137–142. [CrossRef]

- *Hevesi, K. , Gergely Hevesi, B., Kolba, T. N., & Rowland, D. L. (2019). Self-reported reasons for having difficulty reaching orgasm during partnered sex: relation to orgasmic pleasure. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. [CrossRef]

- *Hevesi, K. , Mészáros, V., Kövi, Z., Márki, G., & Szabó, M. (2017). Different characteristics of the Female Sexual Function Index in a sample of sexually active and inactive women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 14, 1133–1141. [CrossRef]

- Holstege, G. , & Huynh, H. K. (2011). Brain circuits for mating behavior in cats and brain activations and de-activations during sexual stimulation and ejaculation and orgasm in humans. Hormones and Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Horton, D. J. (1982). Sex-role orientation, sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction in women (Doctoral dissertation, George Washington University, Washington, District of Columbia). https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=7351884.

- *Hoyer, J. , Uhmann, S., Rambow, J., & Jacobi, F. (2009). Reduction of sexual dysfunction: By-product of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychological disorders? Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. L., & Goodie, J. L. (2017). Sexual Problems. American Psychiatric Association.

- *Hurlbert, D. F. , Apt, C., & Rabehl, S. M. (1993). Key variables to understanding female sexual satisfaction: An examination of women in nondistressed marriages. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, D. F. , & Whittaker, K. E. (1991). The role of masturbation in marital and sexual satisfaction: A comparative study of female masturbators and nonmasturbators. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Hwang, U. J. , Lee, M. S., Jung, S. H., Ahn, S. H., & Kwon, O. Y. (2019). Pelvic Floor Muscle Parameters Affect Sexual Function After 8 Weeks of Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence. Sexual Medicine 7, 505–513. [CrossRef]

- Jannini, E. A. , & Lenzi, A. (2005). Ejaculatory disorders: epidemiology and current approaches to definition, classification and subtyping. World Journal of Urology. [CrossRef]

- *Jensen, P. T. , Klee, M. C., Tharanov, I., & Groenvold, M. (2004). Validation of a questionnaire for self-assesment of sexual function and vaginal changes after gynaecological cancer. Psycho-Oncology. [CrossRef]

- Jiann, B. , Su, C., & Tsai, J. (2013). Is female sexual function related to the male partners’ erectile function? Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Jones, A. C. , Robinson, W. D., & Seedall, R. B. (2018). The role of sexual communication in couples’ sexual outcomes: A dyadic path analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Kahn, A. S. (2001). Entitlement and sexuality: An exploration of the relationship between entitlement level and female sexual attitudes, behaviors, and satisfaction (Doctoral dissertation, Adelphi University, Garden City, New York). https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=5346342.

- Kaighobadi, F., Shackelford, T. K., & Weekes-Shackelford, V. A. (2012). Do women pretend orgasm to retain a mate? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 1121-1125.

- *Kalmbach, D. A. , Arnedt, J. T., Pillai, V., & Ciesla, J. A. (2015). The impact of sleep on female sexual response and behavior: A pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Kalmbach, D. A. , Ciesla, J. A., Janata, J. W., & Kingsberg, S. A. (2012). Specificity of anhedonic depression and anxious arousal with sexual problems among sexually healthy young adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine 9, 505–513. [CrossRef]

- *Kalmbach, D. A. , Kingsberg, S. A., Roth, T., Cheng, P., Fellman-Couture, C., & Drake, C. L. (2019). Sexual function and distress in postmenopausal women with chronic insomnia: exploring the role of stress dysregulation. Nature and Science of Sleep. [CrossRef]

- *Kalmbach, D. A. , & Pillai, V. (2014). Daily affect and female sexual function. Journal of Sexual Medicine 11, 2938–2954. [CrossRef]

- *Karabulutlu, E. Y., Okanli, A., & Sivrikaya, S. K. (2011). Sexual dysfunction and depression in Turkish female hemodialysis patients. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 27, 842-846. http://dspace.balikesir.edu.tr/xmlui/handle/20.500.12462/7148#sthash.4HofFX3Y.dpbs.

- Karney, B. R. , & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- *Kelley, E. L. , & Gidycz, C. A. (2017). Mediators of the relationship between sexual assault and sexual behaviors in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 7, 574–582. [CrossRef]

- *Keskin, G. , Babacan Gümüş, A., & Taşdemir Yiğitoğlu, G. (2019). Sexual dysfunctions and related variables with sexual function in patients who undergo dialysis for chronic renal failure. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28, 257–269. [CrossRef]

- *Khajehei, M. , Doherty, M., Tilley, P. J. M., & Sauer, K. (2015). Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in postpartum Australian women. Journal of Sexual Medicine 12, 1415–1426. [CrossRef]

- Khazaie, H. , Rezaie, L., Payam, N. R., & Najafi, F. (2015). Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction during treatment with fluoxetine, sertraline and trazodone: A randomized controlled trial. General Hospital Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- *Khnaba, D. , Rostom, S., Lahlou, R., Bahiri, R., Abouqal, R., & Hajjaj-Hassouni, N. (2016). Sexual dysfunction and its determinants in Moroccan women with rheumatoid arthritis. Pan African Medical Journal 24, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kikusui, T. , Winslow, J. T., & Mori, Y. (2006). Social buffering: relief from stress and anxiety. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. [CrossRef]

- *Klapilová, K. , Brody, S., Krejčová, L., Husárová, B., & Binter, J. (2015). Sexual satisfaction, sexual compatibility, and relationship adjustment in couples: The role of sexual behaviors, orgasm, and men’s discernment of women’s intercourse orgasm. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Komisaruk, B. R. , & Whipple, B. (2005). Functional MRI of the brain during orgasm in women. Annual Review of Sex Research 16, 62–86. [CrossRef]

- *Kračun, I. , Tul, N., Blickstein, I., & Velikonja, V. G. (2019). Quantitative and qualitative assessment of maternal sexuality during pregnancy. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 47, 335–340. [CrossRef]

- *Kreuter, M. , Dahllöf, A. G., Gudjonsson, G., Sullivan, M., & Siösteen, A. (1998). Sexual adjustment and its predictors after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 12, 349–368. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, T. H. , Haake, P., Hartmann, U., Schedlowski, M., & Exton, M. S. (2002). Orgasm-induced prolactin secretion: feedback control of sexual drive? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, T. H. , Hartmann, U., & Schedlowski, M. (2005). Prolactinergic and dopaminergic mechanisms underlying sexual arousal and orgasm in humans. World Journal of Urology 23(2), 130–138. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K. , Avasthi, A., & Grover, S. (2011). Prevalence and psychological impact of antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: A study from North India. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Kuffel, S. W. , & Heiman, J. R. (2006). Effects of depressive symptoms and experimentally adopted schemas on sexual arousal and affect in sexually healthy women. Archives of Sexual Behavior 35, 163–177. [CrossRef]

- Laan, E. , & Rellini, A. H. (2012). Can we treat anorgasmia in women? The challenge to experiencing pleasure. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Lamela, D. , Figueiredo, B., Jongenelen, I., Morais, A., & Simpson, J. A. (2020). Coparenting and relationship satisfaction in mothers: The moderating role of sociosexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (2000). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. University of Chicago press.

- Laurent, S. M. , & Simons, A. D. (2009). Sexual dysfunction in depression and anxiety: Conceptualizing sexual dysfunction as part of an internalizing dimension. Clinical Psychology Review. [CrossRef]

- *Leeners, B. , Hengartner, M. P., Rössler, W., Ajdacic-Gross, V., & Angst, J. (2014). The role of psychopathological and personality covariates in orgasmic difficulties: A prospective longitudinal evaluation in a cohort of women from age 30 to 50. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Leeners, B. , Kruger, T. H., Brody, S., Schmidlin, S., Naegeli, E., & Egli, M. (2013). The quality of sexual experience in women correlates with post-orgasmic prolactin surges: Results from an experimental prototype study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Leonhardt, N. D. , Willoughby, B. J., Busby, D. M., Yorgason, J. B., & Holmes, E. K. (2018). The significance of the female orgasm: A nationally representative, dyadic study of newlyweds’ orgasm experience. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Levin, R. J. (2007). Sexual activity, health and well-being—The beneficial roles of coitus and masturbation. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Levin, R. J. (2012a). The ever continuing life of that ‘little death’–the human orgasm.

- Levin, R. J. (2012b). The human female orgasm: A critical evaluation of its proposed reproductive functions. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Levin, R. J. (2014). The pharmacology of the human female orgasm—Its biological and physiological backgrounds. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Lew-Starowicz, M. , & Rola, R. (2014). Correlates of sexual function in male and female patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Sexual Medicine 11, 2172–2180. [CrossRef]

- Lipe, H. , Longstreth, W. T., Bird, T. D., & Linde, M. (1990). Sexual function in married men with Parkinson’s disease compared to married men with arthritis. Neurology. [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Sage Publications, Inc.

- *Llaneza, P. , Fernández-Iñarrea, J. M., Arnott, B., García-Portilla, M. P., Chedraui, P., & Pérez-López, F. R. (2011). Sexual function assessment in postmenopausal women with the 14-item Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Madewell, A. N. (2013). Knowing thyself: Constructing women’s sexual identity theory with sexual anatomy knowledge, vulva genital awareness, and sociopolitical ideations (Doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma). https://hdl.handle.net/11244/10973.

- Maes, C. A. (2017). A descriptive analysis of perceived stress and sexual function among community-dwelling older adult males (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona). https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/625647.

- Magon, N., & Kalra, S. (2011). The orgasmic history of oxytocin: Love, lust, and labor. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 15, S156-S161.

- Martin, L. R. , Friedman, H. S., Tucker, J. S., Schwartz, J. E., Criqui, M. H., Wingard, D. L., & Tomlinson-Keasey, C. (1995). An archival prospective study of mental health and longevity. Health Psychology 14(5), 381.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psycholgical Review. [CrossRef]

- *Masmoudi, R. , Aissi, M., Halouani, N., Fathallah, S., Louribi, I., Aloulou, J., Amami, O., & Frih, M. (2018). Female sexual dysfunction and multiple sclerosis: A case-control study. Progres en urologie: Journal de l’Association francaise d’urologie et de la Societe francaise d’urologie. [CrossRef]

- Maassen, G. H., & Bakker, A. B. (2001). Suppressor variables in path models: Definitions and interpretations. Sociological Methods & Research, 30(2), 241-270.

- *McNicoll, G. , Corsini-Munt, S., O. Rosen, N., McDuff, P., & Bergeron, S. (2017). Sexual assertiveness mediates the associations between partner facilitative responses and sexual outcomes in women with provoked Vestibulodynia. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- McShane, B. B. , Bockenholt, U., & Hansen, K. T. (2016). Adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis: An evaluation of selection methods and some cautionary notes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11. [CrossRef]

- Meadow, R. M. (1982). Factors contributing to the sexual satisfaction of married women: A multiple regression analysis (Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona). https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=7354749.

- Meltzer, A. L. , Makhanova, A., Hicks, L. L., French, J. E., McNulty, J. K., & Bradbury, T. N. (2017). Quantifying the sexual afterglow: The lingering benefits of sex and their implications for pair-bonded relationships. Psychological Science. [CrossRef]

- *Mendes, A. K. , Cardoso, F. L., & Savall, A. C. R. (2008). Sexual satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury. Sexuality and Disability 26, 137–147. [CrossRef]

- *Mernone, L. , Fiacco, S., & Ehlert, U. (2019). Psychobiological factors of sexual health in aging women-findings from the Women 40+ Healthy Aging Study. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Meston, C. M. , Hull, E., Levin, R. J., & Sipski, M. (2004a). Disorders of orgasm in women. Journal of Sexual Medicine 1, 66–68. [CrossRef]

- Meston, C. M. , Levin, R. J., Sipski, M. L., Hull, E. M., & Heiman, J. R. (2004b). Women’s orgasm. Annual review of sex research. [CrossRef]

- Mialon, H. M. (2012). The economics of faking ecstasy. Economic Inquiry. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Monga, T. N. , Tan, G., Ostermann, H. J., Monga, U., & Grabois, M. (1998). Sexuality and sexual adjustment of patients with chronic pain. Disability and Rehabilitation 20, 317–329. [CrossRef]

- *Morales, M. G. , Rubio, J. C., Peralta-Ramirez, M. I., Romero, L. H., Fernández, R. R., García, M. C., Navarrete, N. N., & Centeno, N. O. (2013). Impaired sexual function in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: a cross-sectional study. Lupus. [CrossRef]

- Morokqff, P. J. , & Gillilland, R. (1993). Stress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research 30, 43–53. [CrossRef]

- *Moshfeghy, Z. , Tahari, S., Janghorban, R., Najib, F. S., Mani, A., & Sayadi, M. Original Investigation Association of sexual function and psychological symptoms (depression, anxiety and stress) in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Unpublished manuscript. [CrossRef]

- Muehlenhard, C. L. , & Shippee, S. K. (2010). Men’s and women’s reports of pretending orgasm. Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. R. , Checkley, S. A., Seckl, J. R., & Lightman, S. L. (1990). Naloxone inhibits oxytocin release at orgasm in man. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. R. , Seckl, J. R., Burton, S., Checkley, S. A., & Lightman, S. L. (1987). Changes in oxytocin and vasopressin secretion during sexual activity in men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. [CrossRef]

- *Najafabady, M. T. , Salmani, Z., & Abedi, P. (2011). Prevalence and related factors for anorgasmia among reproductive aged women in Hesarak, Iran. Clinics 66, 83–86. [CrossRef]

- *Nascimento, E. R. , Maia, A. C. O., Nardi, A. E., & Silva, A. C. (2015). Sexual dysfunction in arterial hypertension women: The role of depression and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders. [CrossRef]

- *Norhayati, M. N. , & Azman Yacob, M. (2017). Long-term postpartum effect of severe maternal morbidity on sexual function. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S. , Kudo, S., Kitsunai, Y., & Fukuchi, S. (1980). Increase in oxytocin secretion at ejaculation in male. Clinical endocrinology 13, 95–97. [CrossRef]

- *Onem, K. , Erol, B., Sanli, O., Kadioglu, P., Yalin, A. S., Canik, U., Cuhadaroglu, C., & Kadioglu, A. (2008). Is sexual dysfunction in women with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome associated with the severity of the disease? A pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Opperman, E. A. , Benson, L. E., & Milhausen, R. R. (2013). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Female Sexual Function Index. Journal of Sex Research 50, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Opperman, E., Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Rogers, C. (2014). “It feels so good it almost hurts”: Young adults’ experiences of orgasm and sexual pleasure. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(5), 503-515.

- *Özcan, T. , Benli, E., Demir, E. Y., Özer, F., Kaya, Y., & Haytan, C. E. (2014). The relation of sexual dysfunction to depression and anxiety in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. [CrossRef]

- *Özdemir, C. , Eryılmaz, M., Yurtman, F., & Karaman, T. (2007). Sexual functioning after renal transplantation. Transplantation Proceedings 39, 1451–1454.

- *Pakpour, A. H. , Yekaninejad, M. S., Pallich, G., & Burri, A. (2015). Using ecological momentary assessment to investigate short-term variations in sexual functioning in a sample of peri-menopausal women from Iran. PLoS ONE. [CrossRef]

- Palmore, E. B. (1982). Predictors of the longevity difference: A 25-year follow-up. The Gerontologist. [CrossRef]

- *Papini, M. N. , Fioravanti, G., Talamba, G., Benni, L., Pracucci, C., Godini, L., Lazzeretti, L., Casale, S., & Faravelli, C. (2013). Female sexual functioning: the role of psychopathology. Rivista di Psichiatria. [CrossRef]

- *Parish, W. L. , Luo, Y., Stolzenberg, R., Laumann, E. O., Farrer, G., & Pan, S. (2007). Sexual practices and sexual satisfaction: A population based study of Chinese urban adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Pascoal, P. M. , Byers, E. S., Alvarez, M. J., Santos-Iglesias, P., Nobre, P. J., Pereira, C. R., & Laan, E. (2018). A dyadic approach to understanding the link between sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual couples. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- *Peixoto, C. , Carrilho, C. G., Ribeiro, T. T. D. S. B., da Silva, L. M., Gonçalves, E. A., Fernandes, L., Nardi, A. E., Cardoso, A., & Veras, A. B. (2019). Relationship between sexual hormones, quality of life and postmenopausal sexual function. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M. M., & Nobre, P. (2015). Prevalence and sociodemographic predictors of sexual problems in Portugal: a population-based study with women aged 18 to 79 years. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(2), 169-180.

- Persson, G. (1981). Five-year mortality in a 70-year-old urban population in relation to psychiatric diagnosis, personality, sexuality and early parental death. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. [CrossRef]

- *Philippsohn, S. , & Hartmann, U. (2009). Determinants of sexual satisfaction in a sample of German women. Journal of Sexual Medicine 6, 1001–1010. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, T. G. (2003). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: Stress, pets, and oxytocin. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. [CrossRef]

- *Pinney, E. M. , Gerrard, M., & Denney, N. W. (1987). The Pinney Sexual Satisfaction Inventory. Journal of Sex Research 23, 233–251. [CrossRef]

- *Pinsky, I. S. (2016). Attachment quality and sexual satisfaction and sexual functioning in romantic relationships for combat veterans. [CrossRef]

- Powers, C. R. (2012). Female orgasm from intercourse: Importance, partner characteristics, and health (Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Female-Orgasm-From-Intercourse%3A-Importance%2C-Partner-Powers/af8da4739c7dd49aadebf0042a99b0a4b534658f.

- Prause, N. (2012a). The human female orgasm: Critical evaluations of proposed psychological sequelae. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Prause, N. (2012b). A response to Brody, Costa and Hess (2012): theoretical, statistical and construct problems perpetuated in the study of female orgasm. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Quinn-Nilas, C. , Benson, L., Milhausen, R. R., Buchholz, A. C., & Goncalves, M. (2016). The relationship between body image and domains of sexual functioning among heterosexual, emerging adult women. Sexual Medicine 4(3), e182–e189.

- R Core Team (2017). foreign: Read data stored by SPSS, R package version 0.8-70. R Core Team.

- R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (n.d.). R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Randolph, M. E. (2002). The role of depression, relationship support, and child sexual abuse in predicting the impact of chronic pelvic pain on women’s sexual functioning (Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=5439148.

- Regan, P. C., & Atkins, L. (2006). Sex differences and similarities in frequency and intensity of sexual desire. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 34(1), 95-102.

- Richters, J. , de Visser, R., Rissel, C., & Smith, A. (2006). Sexual practices at last heterosexual encounter and occurrence of orgasm in a national survey. Journal of Sex Research 43, 217–226. [CrossRef]

- *Rosen, N. O. , Dubé, J. P., Corsini-Munt, S., & Muise, A. (2019). Partners experience consequences, too: A comparison of the sexual, relational, and psychological adjustment of women with Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder and their partners to control couples. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Rosen, R. , Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., Ferguson, D., & D’Agostino, R. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R. C. , Riley, A., Wagner, G., Osterloh, I. H., Kirkpatrick, J., & Mishra, A. (1997). The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. S. (2010). A generalized formula for converting chi-square tests to effect sizes for meta-analysis. PloS one. [CrossRef]

- *Rottmann, N. , Gilså Hansen, D., dePont Christensen, R., Hagedoorn, M., Frisch, M., Nicolaisen, A., Kroman, N., Flyger, H., & Johansen, C. (2017). Satisfaction with sex life in sexually active heterosexual couples dealing with breast cancer: a nationwide longitudinal study. Acta Oncologica. [CrossRef]

- *Rowland, D. L. , & Kolba, T. N. (2019). Relationship of Specific Sexual Activities to Orgasmic Latency, Pleasure, and Difficulty During Partnered Sex. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 16, 559–568. [CrossRef]

- *Rowland, D. L. , Sullivan, S. L., Hevesi, K., & Hevesi, B. (2018). Orgasmic latency and related parameters in women during partnered and masturbatory sex. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 15, 1463–1471. [CrossRef]

- Sahay, R. D. , Haynes, E. N., Rao, M. B., & Pirko, I. (2012). Assessment of sexual satisfaction in relation to potential sexual problems in women with multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Sexuality and Disability. [CrossRef]

- *Sakinci, M. , Ercan, C. M., Olgan, S., Coksuer, H., Karasahin, K. E., & Kuru, O. (2016). Comparative analysis of copper intrauterine device impact on female sexual dysfunction subtypes. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 55, 30–34. [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, C. M. A. , & Fisher, W. A. (2014). “Did you come?” A qualitative exploration of gender differences in beliefs, experiences, and concerns regarding female orgasm occurrence during heterosexual sexual interactions. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Salamon, E. , Esch, T., & Stefano, G. B. (2005). Role of amygdala in mediating sexual and emotional behavior via coupled nitric oxide release. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 26, 389–395. [CrossRef]

- *Sariyildiz, M. A. , Batmaz, I., Dilek, B., İnanir, A., Bez, Y., Tahtasiz, M., Em, S., & Çevik, R. (2013). Relationship of the sexual functions with the clinical parameters, radiological scores and the quality of life in male patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology International 33, 623–629. [CrossRef]

- *Sarti, C. D. , Graziottin, A., Mincigrucci, M., Ricci, E., Chiaffarino, F., Bonaca, S., Becorpi, A., & Parazzini, F. (2010). Correlates of sexual functioning in Italian menopausal women. Climacteric 13, 447–456. [CrossRef]

- *Scott, S. B. , Ritchie, L., Knopp, K., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. (2018). Sexuality within female same-gender couples: Definitions of sex, sexual frequency norms, and factors associated with sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Seguin, L. J. , Milhausen, R. R., & Kukkonen, T. (2015). The development and validation of the motives for feigning orgasms scale. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 24, 31–48.

- *Seldin, D. R. , Friedman, H. S., & Martin, L. R. (2002). Sexual activity as a predictor of life-span mortality risk. Personality and Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P. R. , & Mikulincer, M. (2002). Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment & Human Development. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A. M. , & Rogge, R. D. (2016). Evaluating and refining the construct of sexual quality with item response Theory: Development of the Quality of Sex Inventory. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Shifren, J. L. , Monz, B. U., Russo, P. A., Segreti, A., & Johannes, C. B. (2008). Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstetrics & Gynecology. [CrossRef]

- *Skoczyński, S. , Nowosielski, K., Minarowski, Ł., Brożek, G., Oraczewska, A., Glinka, K., Ficek, K., Kotulska, B., Tobiczyk, E., Skomoro, R., Mróz, R., & Barczyk, A. (2019). May Dyspnea Sensation Influence the Sexual Function in Men With Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome? A Prospective Control Study. Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. S. , & Wang, Z. (2014). Hypothalamic oxytocin mediates social buffering of the stress response. Biological Psychiatry 76, 281–288. [CrossRef]

- *Speer, J. J. , Hillenberg, B., Sugrue, D. P., Blacker, C., Kresge, C. L., Decker, V. B., Zakalik, D., & Decker, D. A. (2005). Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. The Breast Journal 11, 440–447. [CrossRef]

- Spitalnick, J. S. , & McNair, L. D. (2005). Couples therapy with gay and lesbian clients: An analysis of important clinical issues. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K. R., Ahrold, T. K., & Meston, C. M. (2011). The association between sexual motives and sexual satisfaction: Gender differences and categorical comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(3), 607-618.

- *Stephenson, K. R. , Hughan, C. P., & Meston, C. M. (2012). Childhood sexual abuse moderates the association between sexual functioning and sexual distress in women. Child Abuse and Neglect 36, 180–189. [CrossRef]

- *Stephenson, K. R. , & Meston, C. M. (2010). Differentiating components of sexual well-being in women: Are sexual satisfaction and sexual distress independent constructs? The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2015). The conditional importance of sex: Exploring the association between sexual well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(1), 25-38.

- Stern, J. , Karastoyanova, K., Kandrik, M., Torrance, J., Hahn, A. C., Holzleitner, I., DeBruine, L. M., & Jones, B. C. (2020). Are sexual desire and sociosexual orientation related to men’s salivary steroid hormones? Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology. [CrossRef]

- Strizzi, J. , Landa, L. O., Pappadis, M., Olivera, S. L., Tangarife, E. R. V., Agis, I. F., Perrin, P. B., Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2015). Sexual functioning, desire, and satisfaction in women with TBI and healthy controls. Behavioural Neurology. [CrossRef]

- *Stoeber, J. , & Harvey, L. N. (2016). Multidimensional sexual perfectionism and female sexual function: A longitudinal investigation. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *Takahashi, M. , Inokuchi, T., Watanabe, C., Saito, T., & Kai, I. (2011). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Development of a Japanese version. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Tao, P. , & Brody, S. (2011). Sexual behavior predictors of satisfaction in a Chinese sample. Journal of Sexual Medicine 8, 455–460. [CrossRef]

- *Tavares, I. M. , Laan, E. T. M., & Nobre, P. J. (2017). Cognitive-affective dimensions of female orgasm: The role of automatic thoughts and affect during sexual activity. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Thakurdesai, A. , & Sawant, N. (2018). A prospective study on sexual dysfunctions in depressed males and the response to treatment. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 60, 472. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Therrien, S. , & Brotto, L. A. (2016). A critical examination of the relationship between vaginal orgasm consistency and measures of psychological and sexual functioning and sexual concordance in women with sexual dysfunction. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 25, 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, J. , Kuikka, J., Kupila, J., Partanen, K., Vainio, P., Airaksinen, J., Eronen, M., Hallikainen, T., Paanila, J., Kinnunen, I., & Huttunen, J. (1994). Increase in cerebral blood flow of right prefrontal cortex in man during orgasm. Neuroscience letters 170, 241–243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Tracy, J. K. , & Junginger, J. (2007). Correlates of lesbian sexual functioning. Journal of Women’s Health. [CrossRef]

- *Træen, B. (2007). Sexual dissatisfaction among men and women with congenital and acquired heart disease. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Tuinman, M. A. , Hoekstra, H. J., Vidrine, D. J., Gritz, E. R., Sleijfer, D. T., Fleer, J., & Hoekstra-Weebers, J. E. H. M. (2010). Sexual function, depressive symptoms and marital status in nonseminoma testicular cancer patients: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology. [CrossRef]

- *Tutino, J. S. , Ouimet, A. J., & Shaughnessy, K. (2017). How do psychological risk factors predict sexual outcomes? A comparison of four models of young women’s sexual outcomes. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A., & Wells, B. E. (2017). Declines in sexual frequency among American adults, 1989–2014. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 2389-2401.

- *Uddenberg, N. (1974). Psychological aspects of sexual inadequacy in women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. [CrossRef]

- Urganci, B. , Sevi, B., & Sakman, E. (2021). Better relationships shut the wandering eye: Sociosexual orientation mediates the association between relationship quality and infidelity intentions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. [CrossRef]

- Uvnas-Moberg, K. (1998). Antistress pattern induced by oxytocin. Physiology. [CrossRef]

- *van den Brink, F. , Smeets, M. A. M., Hessen, D. J., & Woertman, L. (2016). Positive body image and sexual functioning in Dutch female university students: The role of adult romantic attachment. Archives of Sexual Behavior. [CrossRef]

- *van Nimwegen, J. F. , Arends, S., van Zuiden, G. S., Vissink, A., Kroese, F. G., & Bootsma, H. (2015). The impact of primary Sjögren’s syndrome on female sexual function. Rheumatology. [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. [CrossRef]

- Villeda Sandoval, C. I. V., Calao-Pérez, M., Enríquez González, A. B., Gonzalez-Cuenca, E., Ibarra-Saavedra, R., Sotomayor, M., & Castillejos Molina, R. A. (2014). Orgasmic Dysfunction: Prevalence and Risk Factors from a Cohort of Young Females in Mexico. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11, 1505-1511. [CrossRef]

- Vrangalova, Z. , & Ong, A. D. (2014). Who benefits from casual sex? The moderating role of sociosexuality. Social Psychological and Personality Science. [CrossRef]

- Velten, J., & Margraf, J. (2017). Satisfaction guaranteed? How individual, partner, and relationship factors impact sexual satisfaction within partnerships. PloS one, 12(2), e0172855.

- Wade, L. (2015). Are women bad at orgasms? Understanding the gender gap. In Tarrant, S. (Ed.), Gender, sex, and politics: In the streets and between the sheets in the 21st century (pp. 227-237). Routledge.

- Wade, L. , Kremer, E. C., & Brown, J. (2005). The incidental orgasm: The presence of clitoral knowledge and the absence of orgasm for women. Women & Health. [CrossRef]

- *Waite, L. J. , & Joyner, K. (2001). Emotional satisfaction and physical pleasure in sexual unions: Time horizon, sexual behavior, and sexual exclusivity. Journal of Marriage and Family. [CrossRef]

- *Wallace, D. H. , & Barbach, L. G. (1974). Preorgasmic group treatment. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 1. [CrossRef]

- Ware, J. E. & Sherbourne, C.D. (1992). A 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. [CrossRef]

- Ware, J. E. , Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34. [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. , & Clark, A. L. (1991). The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ). Unpublished manuscript. [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. , Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- *Weiss, P. , & Brody, S. (2011). International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) scores generated by men or female partners correlate equally well with own satisfaction (sexual, partnership, life, and mental health). The Journal of Sexual Medicine 8, 1404–1410. [CrossRef]

- White, S. E., & Reamy, K. (1982). Sexuality and pregnancy: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 11(5), 429-444.

- WHOQoL Group. (1998). Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological medicine, 28. [CrossRef]

- *Witting, K. , Santtila, P., Alanko, K., Harlaar, N., Jern, P., Johansson, A., Von Der Pahlen, B., Varjonen, M., Algars, M., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2008a). Female sexual function and its associations with number of children, pregnancy, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. [CrossRef]

- *Witting, K. , Santtila, P., Jern, P., Varjonen, M., Wager, I., Höglund, M., Johansson, A., Vikstrom, N., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2008b). Evaluation of the Female Sexual Function Index in a population based sample from Finland. Archives of Sexual Behavior 37, 912–924. [CrossRef]

- *Wongsomboon, V. , Burleson, M. H., & Webster, G. D. (2019). Women’s orgasm and sexual satisfaction in committed sex and casual sex: Relationship between sociosexuality and sexual outcomes in different sexual contexts. The Journal of Sex Research. [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. , Runciman, R., Wylie, K. R., & McManus, R. (2012). An update on female sexual function and dysfunction in old age and its relevance to old age psychiatry. Aging and Disease 3(5), 373.

- World Health Organization. (2002). Sexual and reproductive health: Gender and human rights. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/gender_rights/sexual_health/en/.

- *Yangin, H. B. , Sözer, G. A., Şengün, N., & Kukulu, K. (2008). The relationship between depression and sexual function in menopause period. Maturitas 61, 233–237. [CrossRef]

- *Yanikkerem, E. , Goker, A., Ustgorul, S., & Karakus, A. (2016). Evaluation of sexual functions and marital adjustment of pregnant women in Turkey. International Journal of Impotence Research 28, 176–183. [CrossRef]

- *Yela, D. A. , Soares, P. M., & Benetti-Pinto, C. L. (2018). Influence of sexual function on the social relations and quality of life of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia/RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics. [CrossRef]

- *Yeoh, S. H. , Razali, R., Sidi, H., Razi, Z. R. M., Midin, M., Jaafar, N. R. N., & Das, S. (2014). The relationship between sexual functioning among couples undergoing infertility treatment: A pair of perfect gloves. Comprehensive Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Young, M., Denny, G., Luquis, R., & Young, T. (1998). Correlates of sexual satisfaction in marriage. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 7, 115-128. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Raffy_Luquis/publication/281691542_Correlates_of_sexual_satisfaction_in_marriage/links/5693e45d08ae3ad8e33b3f5d/Correlates-of-sexual-satisfaction-in-marriage.pdf.

- Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia 67, 361–370. [CrossRef]

- *Zhang, H. , Fan, S., & Yip, P. S. F. (2015). Sexual dysfunction among reproductive-aged chinese married women in hong kong: Prevalence, risk factors, and associated consequences. Journal of Sexual Medicine. [CrossRef]

- *Zhou, M. (1993). A survey of sexual states of married, healthy, reproductive age women. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. [CrossRef]

| Category | # subsamples | Category | # subsamples | Category/code | # subsamples | |||

| Subset (# reporting) | (# of effects) | Subset | ||||||

| Summary | Clinical population2 | Country | ||||||

| Distinct samples | 205 | Addison's disease | 1 | Australia | 2 | |||

| Unique subjects | 160,466 | Ankylosing spondylitis | 2 | Belgium | 2 | |||

| Distinct effects | 930 | Brain or spinal cord injury | 3 | Brazil | 7 | |||

| Publication type | Cancer | 3 | Bulgaria | 1 | ||||

| Peer-reviewed article | 187 | Chronic pain | 3 | Canada | 10 | |||

| Thesis/dissertation | 18 | Depression &/or anxiety | 9 | Chile | 2 | |||

| Publication year | Dialysis | 2 | China | 8 | ||||

| 1971-1990 | 7 | Fertility treatment | 3 | Czech Republic | 5 | |||

| 1991-2000 | 10 | Gynecological disorders | 11 | Denmark | 2 | |||

| 2001-2010 | 47 | Heart disease / hypertension | 3 | Egypt | 1 | |||

| 2011-2020 | 141 | Heroin use | 1 | Finland | 5 | |||

| Sex Health1 | Hyperthyroidism | 1 | Germany | 4 | ||||

| Sexual Satisfaction | 152 (322) | Incontinence | 1 | Greece | 1 | |||

| Orgasm | 205 (398) | Lupus | 1 | Hungary | 1 | |||

| Desire | 96 (227) | Metabolic syndrome | 1 | India | 1 | |||

| Lack of pain | 60 (154) | Migraines | 1 | International | 5 | |||

| Lubrication | 58 (167) | Multiple sclerosis | 4 | Iran | 5 | |||

| Erectile function | 18 (38) | Nonspecific medical3 | 2 | Israel | 5 | |||

| Correlate | Obesity &/or eating disorder | 3 | Italy | 12 | ||||

| Psychological distress | 88 (280) | Parkinson's disease | 1 | Japan | 1 | |||

| Psychological well-being | 22 (66) | Pre-, post-, &/or menopausal | 8 | Malaysia | 5 | |||

| Physical health | 9 (38) | Pregnant &/or postpartum | 9 | Mexico | 1 | |||

| Attachment anxiety | 9 (25) | PTSD | 1 | Morocco | 1 | |||

| Attachment avoidance | 9 (25) | Renal transplant | 1 | Netherlands | 5 | |||

| Relationship satisfaction | 54 (110) | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | Norway | 1 | |||

| Type of population2 | Schizophrenia | 2 | Poland | 3 | ||||

| College students | 26 | Sexual abuse | 2 | Portugal | 7 | |||

| Community | 87 | Sexual dysfunction | 12 | Scotland | 1 | |||

| Clinical | 97 | Sjogren’s syndrome | 1 | South Korea | 1 | |||

| Gender | Sleep apnea | 2 | Spain | 3 | ||||

| Female only study | 152 | Stroke | 1 | Sweden | 2 | |||

| Male only study | 40 | Vitamin D3 deficiency | 1 | Switzerland | 3 | |||

| Both genders | 13 | Average age (k=199) | Taiwan | 2 | ||||

| Weighted percent female | 71% | Lowest | 18.8 | Tunisia | 1 | |||

| Relationship length (k=41) | Highest | 73.5 | Turkey | 17 | ||||

| Lowest | 1.4 | Weighted mean | 38.9 | UK | 5 | |||

| Highest | 34.1 | Married / Cohabiting (k=96) | US | 67 | ||||

| Weighted mean | 13.8 | Weighted % | 75.2 | Caucasian (k=182) | ||||

| Weighted % | 64.4 | |||||||

| Author (Year) | Record Type | N | Country | Subsample | Mean Age | Percent White | Sex Health Dimension(s) | Sex Health Scale(s) | Correlate Dimension | Correlate Scale | # effects |

| Abdel-Hamid & Saleh (2011) | PR | 38 | Egypt | Muslim males w/ lifelong delayed ejaculation | 30.8 | 0 | O | IIEF | depressive sxs | SRADM | 1 |

| Abedi et al. (2015) | PR | 228 | Iran | Women w/ & w/out abnormal sexual function | 30.4 | 0 | SODPL | FSFI | perceived stress | PSS | 5 |

| Adam et al. (2020) | PR | 65 | Belgium | Women aged 18-58 w/ orgasm difficulties | 32.7 | 100 | SO | FSFI | only sex health* | 1 | |

| Aerts et al. (2015) | PR | 84 | Belgium | Women w/ endometrial cancer | 63.0 | 100 | O | SSFS | relationship sat | DAS | 1 |

| Alvisi et al. (2014) | PR | 204 | Italy | Women w/ & w/out metabolic syndrome | 40.0 | 100 | O | FSFI | depressive sxs | MHQ | 2 |

| Appa et al. (2014) | PR | 1997 | US | Middle-aged women w/ multiple medical diagnoses | 60.2 | 36 | SODPL | 1 item | depression diagnosis | medical diagnosis | 5 |

| Artune-Ulkumen et al. (2014) | PR | 177 | Turkey | Women in sexual relationships w/ & w/o sexual dysfunction | 32.3 | 0 | SODPL | FSFI | mental health, vitality, physical health | SF-36 | 15 |

| Asselmann et al. (2016) | PR | 149 | Germany | Pregnant women w/ & w/o depression | 28.9 | 100 | SODL | MGH | depression diagnosis | CIDI | 4 |

| Assimakopoulos et al. (2006) | PR | 110 | Greece | Healthy women & obese women preparing for bariatric surgery | 34.4 | 100 | SODPL | FSFI | depressive sxs | BDI | 5 |

| Atis et al. (2011) | PR | 80 | Turkey | Women w/ & w/o hyperthyroidism | 36.8 | 0 | SODPL | FSFI | depressive sxs | BDI | 5 |

| Aubin et al. (2008) | PR | 72 | US | Men w/chronic pelvic pain syndrome | 40.8 | 66 | O | BSFQ | depressive sxs | CESD | 1 |

| Bakjtiari et al. (2016) | PR | 236 | Iran | Women in fertility treatment | 26.4 | 0 | SOD | DSM-IV | relationship sat | 1 item | 4 |

| Barbara et al. (2016) | PR | 269 | Italy | Women who have given birth 6mo ago | 34.4 | 100 | SO | FSFI | only sex health* | 1 | |

| Barrientos & Páez (2006) | PR | 4339 | Chile | Women & men aged 18-69 | 39.7 | 0 | SO | 1 item | only sex health* | 2 | |

| Battaglia et al. (2011) | PR | 87 | Italy | Menstruating women | 28.7 | 100 | O | 1 item | depressive sxs | BDI | 1 |

| Beaber & Werner (2009) | PR | 120 | US | Women in heterosexual & lesbian relationships | 29.4 | 77 | SODPL | FSFI | only sex health* | 16 | |

| Berenguer et al. (2019) | PR | 149 | Portugal | Adult women | 25.0 | 0 | SO | FSFI | only sex health* | 1 | |

| Blair et al. (2018) | PR | 750 | Canada | Women & men in same or opposite sex relationships | 30.0 | 0 | SO | IIEF | only sex health* | 2 | |

| Borissova et al. (2001) | PR | 627 | Bulgaria | Middle-aged pre- & post-menopausal women w/ & w/o hormone replacement therapy | 48.0 | 100 | O | 1 item | coping with life | 1 item | 1 |

| Brody & Weiss (2011) | PR | 1570 | Czech Republic | Women & men aged 35-65 in relationships | 48.8 | 100 | SO | 1 item | life sat, relationship sat | LiSat | 6 |

| Burleson et al. (2007) | PR | 58 | US | Middle-aged women | 47.6 | 0 | O | 1 item | Depressive sxs, positive affect | 1 item, 7 items | 2 |

| Burri et al. (2015) | PR | 507 | UK | Pre- & post-menopausal twin women | 56.3 | 100 | SODPL | FSFI | relationship sat | 1 item | 14 |

| Burri et al. (2013) | PR | 866 | UK | Monozygotic twin women discordant for sexual dysfunction | 55.0 | 100 | SODPL | FSFI | relationship sat | 1 item | 5 |

| Cagnacci et al. (2019) | PR | 518 | Italy | Sexually active women aged 40-55 at gynecological clinics | 49.4 | 100 | SO | FSFI | only sex health* | 1 | |

| Canat et al. (2016) | PR | 108 | Turkey | Women aged 22-51 w/ vitamin D3 deficiency | 34.9 | 0 | SODPL | FSFI | depressive sxs | BDI | 5 |

| Carmen (2014) | MT | 145 | US | Adult women | 25.8 | 0 | SODPL | FSFI | only sex health* | 10 | |

| Carrobles et al. (2011) | PR | 157 | Spain | College women aged 20-45 | 22.8 | 0 | SO | 3 items | mental health | WHO-5 | 3 |

| Castellini et al. (2010) | PR | 309 | Italy | Obese & not obese women w/ & w/o Binge ED | 39.1 | 100 | SODPL | FSFI | depressive sxs | BDI | 15 |

| Ceyhan et al. (2019) | PR | 102 | Turkey | Married women in treatment for hypertension | 55.1 | 0 | SOD | ASEX | relationship sat | MAT | 3 |

| Chang et al. (2012) | PR | 555 | Taiwan | Pregnant women | 33.0 | 0 | SODPL | FSFI | depressive sxs | CESD | 5 |

| Chang et al. (2019) | PR | 1026 | Taiwan | Women aged 40-65 | 48.5 | 0 | SODPL | FSFI | mental health, physical health | SF-12, SF-12 | 10 |