1. Introduction

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the country has rapidly developed into the world’s second-largest economy, achieving remarkable progress in just over 70 years. As China’s population of 1.4 billion continues to age, a significant segment of the elderly—individuals who have experienced eras of depression, hardship, and poverty—are now entering retirement. Freed from occupational responsibilities, they are emerging as a new cohort of consumers who possess both vitality and emotional richness, thus unleashing fresh potential in the tourism sector.

At the same time, China and R country are entering a new era of consumption [Li et al., 2021]. The two countries share a unique historical trajectory, including personnel exchanges and cooperation during the communist period. This common background fosters a mutual curiosity and desire among the elderly populations of both nations to understand each other more deeply. These dynamics contribute to the development of the R country tourism market, drawing inspiration from the expansion of China’s silver tourism experience and further attracting cross-border visitors. In light of the current international environment, traveling to R country has become one of the most favorable options for Chinese tourists.

Tourist behavior and intentions—such as sightseeing, word-of-mouth promotion, and personal recommendation—play a critical role in reducing operational costs, enhancing competitive advantages, and promoting the sustainable development of tourism destinations [Guo et al., 2018]. Perceived value lies at the core of service experiences and is widely acknowledged as a vital competitive asset for tourism enterprises. Existing research indicates that perceived value can directly or indirectly influence behavioral intention [Bradley et al., 2012; Habibi \& Rasoolimanesh, 2021; Haji et al., 2021]. However, due to the diverse and complex nature of tourism participants, consumption environments, and behavioral contexts, the precise mechanisms linking perceived value and visit intention remain underexplored. While some studies have applied the theoretical framework of perceived value and behavioral intention to tourism destinations, few have investigated how tourists’ emotional shifts during travel impact their personal intentions [Jia and Lin, 2016], making it difficult to understand the drivers of positive tourist behavior fully.

Emotional attachment to place is a key dimension of the human–land relationship. Related studies help to interpret this complex relationship through perspectives such as perception and psychology [Gao and Zhao, 2016]. Generally, individuals develop strong emotional bonds with their long-term living environments, such as their hometowns and communities [Pani-Harreman et al., 2021; Shu et al., 2023]. In certain travel scenarios, tourists may also form emotional attachments to destinations, which can significantly influence their behavioral intentions. Therefore, it is worthwhile to further examine how tourists’ perceived value and emotional connections to destinations affect their intention to visit, particularly in the context of silver tourism.

In recent years, R country has introduced a series of measures to simplify the visa application process for Chinese tourists. Since August 1, 2023, R country has implemented an electronic visa system for Chinese nationals, eliminating the previously cumbersome paper-based procedures. To enhance service accessibility, China Visa Centers have been established in major cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg, offering more convenient and efficient visa services. Furthermore, the bilateral visa-free agreement for group tours has been reinstated, enabling Chinese tourists to visit R country without the need to apply for individual visas. These initiatives have significantly improved travel accessibility for Chinese silver-haired tourists.

As a nation endowed with a rich historical heritage, diverse culture, and stunning natural landscapes, R country continues to attract substantial interest among Chinese travelers. In parallel, the aging of China’s population has led to a noticeable increase in demand within the silver tourism market [Zuo \& Lai, 2020; TALOŞ et al., 2021]. Elderly tourists, who typically possess ample leisure time and strong purchasing power, are becoming an increasingly influential segment within the tourism industry. During travel, silver tourists form subjective perceptions of tourism products and services; when their experiences exceed expectations, they often report psychological satisfaction, form positive emotional bonds, and exhibit favorable behavioral intentions such as engaging in sightseeing or offering recommendations.

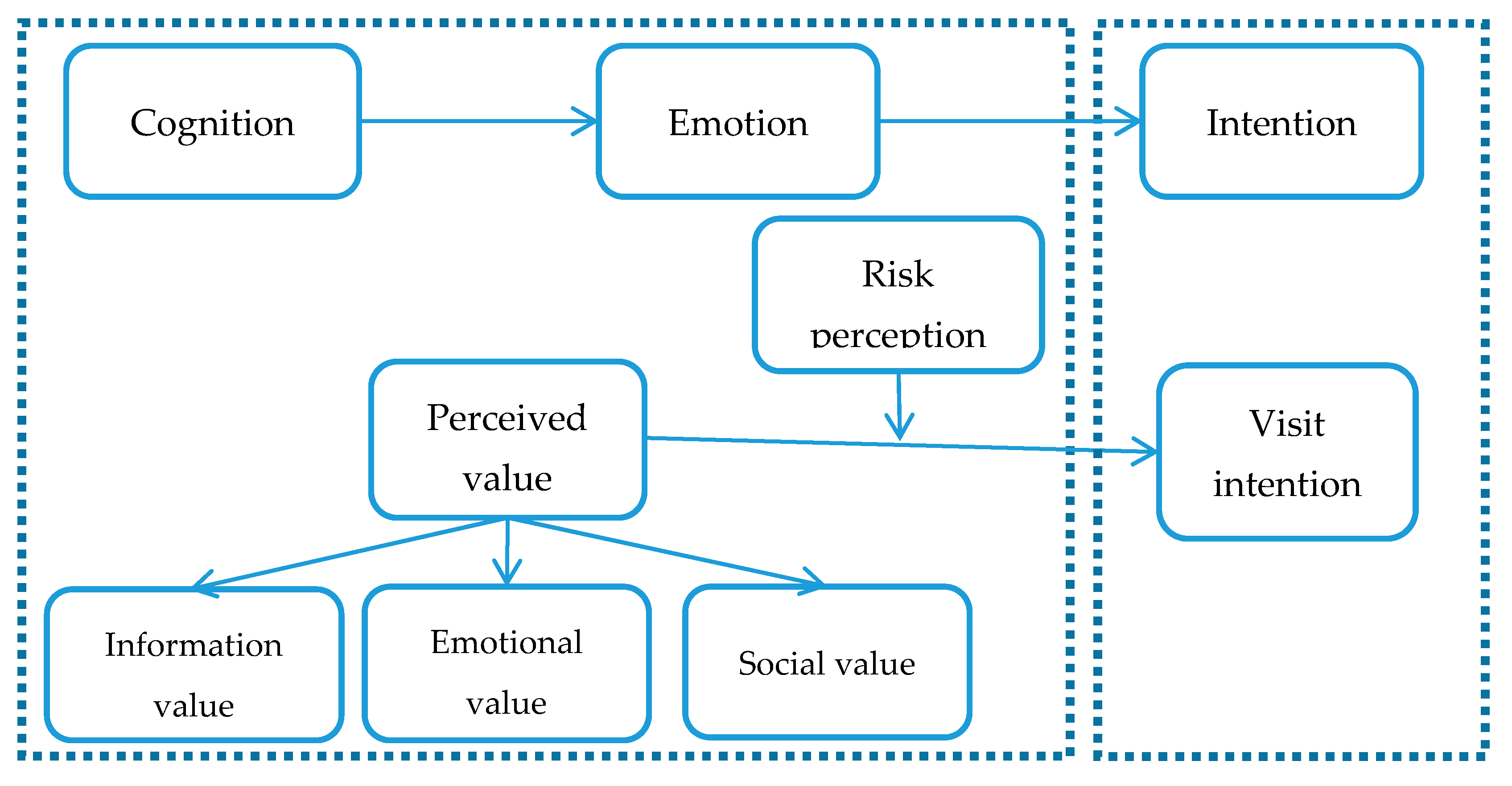

The objective of this study is to examine the visit intention of Chinese silver tourists through three dimensions of perceived value: information value, emotional value, and social value. Anchored in the cognition–emotion–intention framework and drawing upon prior research [Guo et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2020], we develop a conceptual model that situates perceived value within the domains of “cognition” and “emotion”, incorporates risk perception within the domain of “emotion”, and locates visit intention within the domain of “intention”. Based on a questionnaire survey of 314 Chinese silver tourists aged over 50, we employ both an Ordered Probit model and a moderating effect model to empirically assess the influence of perceived value on visit intention toward R country, as well as the moderating role played by risk perception.

This study seeks to explore how value propositions can be dynamically adjusted in response to organizational cognitive processes and absorptive capacity within a changing external environment. It aims to stimulate the travel intentions of Chinese silver-haired tourists, clarify the formation mechanism of their perceived value, and analyze how perceived value affects visit intention under different contextual conditions. Overall, this research offers a novel perspective for understanding the relationship between tourist perceived value and behavioral intention.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and theoretical background, and presents the research hypotheses.

Section 3 details the data sources, model specifications, and variable definitions.

Section 4 presents the empirical findings and corresponding discussion.

Section 5 concludes the study and offers policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Hypothesis

2.1. Definition of Perceived Value

The generally accepted definition of perceived value is given by Zeithaml (1988)[

1], which refers to the overall evaluation of product utility by customers on the basis of weighing gains and losses. It is the evaluation of the unity of a tangible or intangible product based on the benefits they received from the service provider and the price they pay for the service (Kim and Thapa, 2018[

2]; Molinillo et al., 2021[

3]). Particularly, the definition of tourist perceived value has not been unified. Based on the definition of customer perceived value, the existing studies tend to believe that tourist perceived value is the overall evaluation of tourists on the degree to which the tourism products and services they purchase to meet their tourism needs (Stevens, 1992)[

4]. Many studies in recent years (Gallarza and Saura, 2006[

5]; Prebensen et al., 2015[

6]; Jeong & Kim, 2020) suggested that single-dimensional scale could not accurately measure the whole perceived value, and multi-dimensional scale should be adopted for measurement. At present, most literature assume that tourist perceived value is a multi-dimensional concept.

However, there is no consensus on the dimension composition of tourist perceived value, due to the different attributes of tourist destinations, tourists’ desires and expectations. For example, Sui et al. (2009)[

7] proposed that the tourist perceived value of intangible cultural heritage includes six dimensions: entity value, efficiency value, service value, social value, cost value and hedonic value. Prebensen et al. (2015) studied on winter tourist and showed that the tourist perceived value includes five dimensions including physical value, social value, emotional value, learning value and economic value. Waheed and Hassan (2017) [

8]measured the direct impacts of the 5 variables on revisit intention including functional value, emotional value, epistemic value, social value and conditional value. Guo et al. (2018) examined the impacts of perceived value on revisiting intention, as well as its mechanism from the three dimensions of entity value, learning value and economic value. Chen and Xu (2021)[

9] categorized perceived value from three dimensions including emotional value, cognitive value and cost value, while Li et al. (2022)[

10] suggested that perceived value should be categorized into ecological and environmental value, historical and cultural value, learning and educational value. Since the definition and dimension of tourist perceived value are not unified, the scales developed by scholars are also different.

Based on the existing studies, as well as the individual characteristics of Chinese silver tourists and the development of tourism in China and R country, we attempt to construct a conceptual framework of perceived value from three dimensions, i.e., information value, emotional value and social value, and examine the impacts of perceived value on Chinese silver tourists’ visit intention to R country and its mechanism.

2.2. Perceived Value and Visit Intention

Visit intention refers to the possibility of tourists going to the tourist destination to participate in tourism activities, which belongs to the category of “intention” in the attitude component. Tourist perceived value of the products or services they consume is a rational evaluation based on perceived gain and perceived gain and loss. According to the theory of social exchange, tourist destinations with perceived gains overweight losses are more popular among tourists (Daye et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Based on the theory of “cognitive-emotion-intention”, perceived value belongs to the categories of “cognition” and “emotion”, and will play a role in visit intention of tourists (Yin & Borbon, 2022). In the field of tourism, perceived value is considered to be a key factor affecting tourists’ consumption and decision-making behavior, and has an significant impact on tourists’ satisfaction and travel intention (Williams and Soutar, 2009 [

11]; Gardiner et al., 2013 [

12]; Meng et al., 2018[

13]; Wen and Huang, 2021[

14]). Hence, perceived value is an important determinant affecting revisiting intention and behaviors, and its inclusion in the analysis will help to better explain the formation of visit intention.

However, the interaction between perceived value and behavioral intention has not yet to be fully understood. Some scholars show that tourist perceived value has no significant impact on revisiting intention (Murphy et al., 2000[

15]), while others suggest that single dimension of tourist perceived value can indirectly affect loyalty through satisfaction (Li and Zhang, 2010)[

16]. Ranjbarian and Pool (2015)[

17] believed that the higher the perceived value obtained by tourists, the more likely they are to return to the exact same destination in the future. For instance, Ban et al. (2021) [

18] showed that perceived value exerted limited effect on customer satisfaction and intention to revisit among the re-visitors. Wang et al. (2023) [

19]found that pluralistic values have significant effects on tourist’s attitudes towards visited heritage destinations and other postmodern heritage sites, which affects the tourists’ intention to visit other postmodern heritage sites, based on the value-attitude-behaviour model. Overall, most studies show that the perceived value of tourists will positively affect the visit intention (Kim et al., 2010[

20]; Cheng and Lu, 2013[

21]; Han, 2015[

22]; Jeong & Kim, 2020). Although the existing studies have explored the possibility of perceived value affecting travel intention, there is no certain answer on how perceived value affects travel intention, and there is a lack of detailed research on perceived value to show the impacts and mechanism of perceived value on travel intention from different dimensions.

Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) theory not only links individual knowledge and behavior, but also noticed the influence of different knowledge levels on individual attitudes (Chen et al., 2023). This theory provides a theoretical perspective for understanding the influence mechanism of silver tourists’ attitude and behavior on visiting R country. However, only obtaining the attitude of tourists to travel to R country cannot understand the trigger sources of these attitudes, and it is not conducive to the targeted adjustment and optimization of tourism services. Hence, based on the cognition-emotion-intention theory and the KAP theory, we believe that the formation of perceived information value, emotional value and social value of silver tourists is highly dependent on their own cognitive level, and the intention to visit R country would be produced, before entering the new tourism environment. During the process, the risk perception of tourists will exert a moderating effect and affect the relationship between perceived value and visit intention. By analyzing the interaction between perceived value, risk perception and tourism intention of silver tourists, it is helpful to understand the demand of tourists, highlight the individual attributes, and provide beneficial inspiration for promoting the development of inbound tourism in R country.

2.3. Moderating Effects of Risk Perception

Risk perception reflects the risks and uncertainties that tourists may confront in while choosing tourist destinations (Xie et al., 2020; Chan, 2021), and it is a main factor affecting tourists’ perception and attitude towards destinations. Since tourism activities are carried out in an unusual environment, tourists cannot perceive the specific content and form of tourism products before purchasing. Therefore, the remoteness of tourism activities and the invisibility of tourism products increase the risk of tourism decision-making. Gursoy and Gavcar (2003)[

23] showed that possibility of risk will promote the tourists’ understanding of the travel destination. Zhang and Lu (2010)[

24] also suggested that the greater the perceived risk possibility of tourists in the process of choosing tourist destinations, the more time and energy they will spend collecting relevant information of tourist destinations, making thorough plans and arrangements for travel schedules, and actively participating in various activities in tourist destinations, in order to avoid risks and obtain high-quality tourism experience.

Similar to the interaction between perceived effort, perceived value and satisfaction, risk possibility may affect the interaction between perceived value and visit intention due to perceived efforts (Nguyen Viet et al., 2020). If the tourist perceived the possibility of high risk when making travel decisions, they would need to pay more time, energy and costs to avoid risks, which would weaken the impacts of perceived value on satisfaction. On the contrary, the cost to pay is small when the possibility of low risk is perceived (Yin et AL., 2020), and the perceived value is mainly attributed to the travel agency and the tourist destination, thus enhancing the impacts of perceived value on visit intention. The interaction mechanism between perceived value, risk perception and visit intention is shown in

Figure 1.

Hence, we propose the following theoretical hypothesis:

H1: Perceived value has a significant positive effect on the visit intention of silver tourists traveling to R country;

H2: Risk perception has a significant negative effect on the visit intention of silver tourists traveling to R country;

H3: Risk perception can negatively moderate the positive effects of perceived value on the visit intention of silver tourists traveling to R country.

3. Data, Model and Variables

3.1. Source of Data

This study uses a questionnaire survey data set collected from October 08 to November 08, 2023. Using the Questionnaire Star platform, the investigators mainly collected questionnaires by telephone interview, face-to-face interview and online filling. The respondents were Chinese silver-haired tourists over the age of 50. To prompt the enthusiasm of tourists to complete the questionnaire, when asking whether they were willing to accept the survey, they would be informed that they will be rewarded with red envelopes. A total of 380 questionnaires were sent out, 372 were recovered, and 314 valid questionnaires were obtained. The sample overview is shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Model Specification

The dependent variable is the intention of Chinese silver tourists to visit R country, which is a natural and orderly discrete variable. Probabilistic models, such as Logit, Probit, Tobit, etc. are ideal estimation methods when analyzing discrete choice problems. For the discrete values of dependent variable greater than two classes, the ordered probability model should be used. As Ordered Probit model is commonly used to process multi-category discrete data in recent years, we use Ordered Probit model to evaluate the impacts of perceived value on visit intention. Compared with OLS regression, structural equation model and other methods, Ordered Probit model can better fit complex datasets and estimate the results more accurately.

The Ordered Probit model can be derived using the latent variable method, as shown in Equation (1).

where i=1,2,... N,

is a set of independent variables,

is a set of parameters to be estimated, and

is a random error term that follows the standard normal distribution. If

is observable for all observations, then the distribution assumptions of

are not needed for

which can be estimated using ordinary least square (OLS) method. For the data types considered in this article,

itself is not observed. On the contrary, the observed dependent variables

are discrete and take values {1,2,... , J}, and is related to

as follows:

where,

a is an additional parameter, and

. Therefore, the range of

is divided into J mutually exclusive exhaustive intervals, and the variable y represents the interval in which a particular observation is located. The dependent variable y is an ordinal number and

is the parameter to be estimated. For 2≤j≤j−1, the probability of a particular observation is given by:

where F is the cumulative distribution function of

, and suppose it contains no additional unknown parameters, for instance,

has a known variance. The hypothesis determines the scale at which y * is measured, but does not determine the origin. Identification can be achieved by assuming that the intercept is zero (

contains no constant term), or by fixing one of

. Here, we use the former, and the probability of all possible outcomes is:

If we use additional symbols

and

, we can rewrite them as:

It defines a class of cumulative probability models where the known cumulative probability transformation is considered to be a linear function of

variable, only the intercept of that function varies in different classes:

The natural estimator of such models is the maximum likelihood estimator.

Then, the log-likelihood of the model is given by:

For (), the parameter M + J−1, is maximized, where N is the number of exogenous variables, (and therefore, N) does not include the intercept.

Generally, the Ordered Probit and Ordered Logit models are used to analyze ordered responses. The Ordered Probit model proposed by Aitchison and Silvey (1957) [

25] assumes

. Using scale normalization σ= 1 and applying zero intercept for identification, the probability can be obtained.

where Φ is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal, where the logarithmic likelihood is (3) and F is replaced by Φ.

In the study, we aim to empirically examine the impacts of perceived value on visit intention. The model can be set as:

where

is the visit intention of the

ith tourist traveling to R country,

is the perceived value of the

ith tourist,

is the risk perception of the

ith tourist, and

is a vector of control variables affecting the visit intention of Chinese silver tourists traveling to R country.

is constant,

、

、

are parameters to be estimated, and

is a random error term.

To examine whether risk perception can moderate the impacts of perceived value on visit intention, we introduce an interaction term into the model.

where,

is the interaction term of perceived value and risk perception,

is constant,

and

are parameters to be estimated, and

is a random error term.

3.3. Variables and Descriptive Statistics

Dependent variable: Visit intention

The dependent variable of this study is visit intention, measured as the willingness of Chinese silver tourists to visit R country in the near future. It is an ordered variable assigned a value of 1 to 5, and higher value means stronger visit intention of silver tourists traveling to R country.

Core independent variable: Perceived value

We mainly measure perceived value from three dimensions: information value, emotional value and social value. The information value is measured by the tourists’ knowledge of R country’s tourism, the emotional value is measured by the consideration of tourists’ dreams or feelings when traveling to R country, and the social value is measured by the tourists’ attention to tourist evaluation and comments on the scenic spot.

Moderating variable: Risk perception

Considering that risk possibility may affect the process of perceived value affecting visit intention, we introduce two moderating variables: tourists’ willingness to travel by air and tourists’ willingness to travel only when they are convinced that the tourist destination is absolutely safe. The former is used for empirical analysis of the moderating effect of risk perception, while the latter is used for robustness checks.

Control variables

In this study, we also controlled the individual and family characteristics of the silver tourists, including age, gender, education level, income level, residence registration, risk preference, proportion of travel expenditure, outbound travel frequency and other factors on their visit intention to R country.

Table 2 lists the definitions and descriptions of variables.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Perceived Value on Visit Intention

In order to examine whether the perceived value can affect the intention of Chinese silver tourists to visit R country, an empirical analysis is carried out on Equation (4), and the regression results are shown in

Table 3. Model (1)–(3) used Ordered Probit model to evaluate the effects of perceived value on tourism intention under different circumstances. For robustness checks, models (4) and (5) used Ordered Logit model and OLS regression analysis respectively.

The results show that under different conditions, the estimated coefficients of information value, emotional value and social value are significantly positive, indicating that the perceived information value, emotional value and social value of silver tourists will positively promote the intention to visit R country. It is consistent with the existing findings (Cheng and Lu, 2013 [

26]; Ranjbarian and Pool, 2015 [

27]). First, the more silver tourists know about R country’s tourism, the higher the perceived information value is, and the more willing they are to visit R country. Second, the stronger the emotional attachment of silver tourists to R country, the higher the perceived emotional value is, the more willing to visit R country. Third, the more attention silver tourists pay to the tourists’ evaluation and comments on R country’s tourism, the higher the perceived social value is, and the more willing they are to visit R country.

The estimated coefficient of risk perception is significantly negative, suggesting that the stronger the risk perception of silver tourists, the weaker intention to visit R country, which verifies the above-mentioned theoretical hypothesis. Risk possibility means risks and uncertainties that tourists may confront with while choosing tourist destinations. Since tourism activities are carried out in an unusual environment, tourists cannot perceive the specific content and form of tourism products and services before traveling, so the remoteness of tourism activities and the intangibility of products increase the risk of tourism decision-making.

We can see from the Models (4) and (5) that similar results were obtained by using Ordered Logit model and OLS regression analysis, further indicating that perceived value can significantly promote their intention to visit R country, while risk perception reduces the visit intention.

4.2. Moderating Effects of Risk Perception

In order to explore whether risk perception can moderate the impacts of perceived value on visit intention, we conducted a regression analysis on Equation (5) by using Ordered Probit model, and the empirical results were shown in

Table 4. Model (1) evaluated the moderating effects of risk perception on the impacts of perceived information value on visit intention. It can be seen that the estimated coefficient of information value is significantly positive, while the estimated coefficient of the interaction term between information value and risk perception is significant and negative, indicating that perceived risk will reduce the positive effects of perceived information value on visit intention of silver tourists. A possible explanation is that silver tourists perceive the possibility of high risk when making travel decisions. In order to avoid risks, they need to pay more time, energy and other costs to collect destination information, thus weakening the positive impacts of perceived information value on visit intention. On the contrary, if the possibility of low risk is perceived, the cost for tourists to search for information becomes smaller, and the positive impacts of perceived information value on visit intention would be enhanced.

Model (2) evaluated the moderating effect of risk perception on the impacts of perceived emotional value on visit intention. It can be seen that the estimated coefficient of emotional value is significantly positive, while the estimated coefficient of the interaction term between emotional value and risk perception is significantly negative, indicating that perceived risk will reduce the positive impact of perceived emotional value on visit intention to some extent. To avoid risks and obtain high-quality tourism experience, the greater the perceived risk possibility of silver tourists in the process of traveling to R country, the more time and energy they will devote to collecting relevant information about R country’s tourism, making thorough plans and arrangements for travel schedules, and actively participating in various activities at tourist destinations (Guo et al., 2018). In this process, tourists may have a strong emotional perception of pay, which will affect the relationship between perceived value and tourists’ satisfaction (Zeithaml, 1988)[

28], and then hurt visit intention.

Model (3) examines the moderating effect of risk perception on the relationship between perceived social value and visit intention. The estimation results show that the coefficient of social value is significantly positive, while the interaction term between social value and risk perception is significantly negative. This suggests that perceived risk weakens the positive influence of social value on the visit intention of silver tourists. One possible explanation is that tourists with a higher level of risk perception are more inclined to seek out evaluations and public commentary related to tourism in R country. In doing so, they may become more exposed to negative opinions or unfavorable narratives about the destination, which could amplify their sense of perceived risk and, in turn, suppress their willingness to visit. This phenomenon aligns with the current national and public discourse context surrounding R country. Following the onset of the conflict between R country and U country, a parallel information war has emerged, with media in both countries shaping and framing content in ways that reflect national perspectives and attempt to garner emotional support from the international community. Similarly, Chinese media coverage and associated public commentary on relevant events inevitably influence the perceptions and intentions of Chinese tourists toward visiting R country. Given the heterogeneity in tourists’ cognitive abilities and value orientations, their reactions to media narratives and public discourse are likely to differ. Consequently, varying levels of risk perception will lead to divergent intentions regarding travel to R country.

4.3. Robustness Checks

To assess the robustness of the findings, this study redefined the measurement of risk perception. Specifically, risk perception was captured by evaluating whether Chinese silver tourists were only willing to visit R country if they were convinced that the destination was safe. This variable was constructed as an ordered scale ranging from 1 to 5, where a higher value represents a lower perceived risk, indicating weaker risk perception. An Ordered Probit model was employed to conduct the regression analysis, and the results are presented in

Table 5.

The regression results reveal that the estimated coefficients for information value, emotional value, and social value are all significantly positive, suggesting that higher levels of perceived value are associated with stronger intentions to visit R country. This finding is consistent with the results from the baseline model. Additionally, the estimated coefficient of risk perception is significantly positive, indicating that weaker perceived risk corresponds to a stronger travel intention—an outcome that aligns with theoretical expectations. Furthermore, the estimated coefficients for the interaction terms between each dimension of perceived value (information, emotional, and social) and risk perception are all significantly positive. This implies that risk perception exerts a negative moderating effect on the relationship between perceived value and visit intention. In other words, when tourists are assured of the absolute safety of the destination, the positive influence of perceived value on visit intention is enhanced. These results are in line with earlier findings and confirm the robustness of the regression estimates.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Based on the “cognition–emotion–intention” relationship theory, this study constructs a conceptual framework to examine the impact of perceived value on visit intention. Utilizing questionnaire data collected from 314 Chinese silver tourists aged over 50, we employ an Ordered Probit model to empirically investigate whether and how perceived value influences their intention to visit R country.

The findings reveal three key insights. First, information value, emotional value, and social value each have a significant and positive effect on the visit intention of silver tourists toward R country. Second, risk perception significantly and negatively affects their intention to visit. Third, risk perception negatively moderates the positive effects of information value, emotional value, and social value on visit intention.

These results suggest that as perceived risk increases, the positive influence of perceived value dimensions on visit intention weakens. Conversely, when perceived risk is lower, the positive association becomes stronger. In contrast to previous studies that have often treated perceived value as a single, undifferentiated construct, our research adopts a multidimensional approach and provides more detailed insights. We theoretically distinguish the relative importance of each dimension, offering both theoretical clarification and practical implications for strengthening visit intention through targeted value enhancement.

The theoretical contributions of this study are threefold. First, by focusing on Chinese silver tourists as the research subject, the study extends the practical applicability of the cognition–emotion–intention framework and offers new perspectives for constructing value propositions tailored to this demographic. Second, we confirm that information value, emotional value, and social value all enhance visit intention, with emotional value having the strongest effect (= 0.416***), followed by information value (= 0.275***) and social value (= 0.169**). Third, we explore the moderating role of risk perception across all three perceived value dimensions, confirming its interactive effects with perceived value and visit intention and clarifying the boundary conditions of this relationship.

Based on these findings, we propose the following strategies to enhance the value proposition for silver tourists traveling to R country. First, improve the information value by strengthening external promotion and marketing of R country’s tourism to attract Chinese silver tourists. Second, enhance the emotional value by developing tourism products themed around sentiment and aspiration, thereby stimulating emotional resonance and desire to visit. Third, promote social value by investing in word-of-mouth campaigns and brand building to shape public perception and strengthen tourism intention. Fourth, reduce risk perception by managing safety concerns, increasing the number of cross-border tourist trains between China and R country, implementing visa facilitation policies, and improving the overall sense of security for elderly tourists.

Against the backdrop of global population aging and increasingly diversified, personalized tourism demands, silver tourism presents enormous market potential. Providing value propositions tailored to silver tourists and tapping into their market demand will contribute to the prosperity and development of R country’s tourism sector. Lessons drawn from the success of China’s silver tourism initiatives offer valuable guidance for the development of R country’s silver tourism market and can inform the design of new products and innovative business models by tourism enterprises in R country.

Naturally, this study has certain limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the sample size is relatively limited due to challenges in reaching elderly respondents and their relatively lower levels of internet activity. Most data were collected via face-to-face or telephone interviews. Although 372 responses were collected and 314 deemed valid—sufficient for empirical analysis—future studies should aim to expand the sample to further validate the findings. Second, while this study focuses on three dimensions of perceived value—information, emotional, and social—other dimensions, such as economic value, were not analyzed separately. We controlled for income level to mitigate multicollinearity, but future research could incorporate economic value into a more comprehensive framework to explore its effects on visit intention and further elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

References

- Zeithaml V A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 1988, 52(3): 2-22.

- Kim, M., Thapa, B. Perceived value and flow experience: Application in a nature-based tourism context. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2018, 8, 373-384.

- Molinillo, S., Aguilar-Illescas, R., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Social commerce website design, perceived value and loyalty behavior intentions: The moderating roles of gender, age and frequency of use.Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2021, 63, 102404.

- Stevens B F. Price value perceptions of travelers. Journal of Travel Research, 1992, 31(2): 44-48.

- Gallarza M G, Saura I G. Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behaviour. Tourism Management, 2006, 27(3): 437-452.

- Prebensen N K, Kim H, Uysal M. Cocreation as moderator between the experience value and satisfaction relationship. Journal of Travel Research, 2015, 55(7): 934-945.

- Sui, L., Li, Y., Chen, Y. The differences of perceived value between Chinese and Western cultural heritage tourists. Tourism Science, 2009, 23(6): 14-20.

- Waheed, N., Hassan, Z. Influence of customer perceived value on tourist satisfaction and revisit intention: A study on Guesthouses in Maldives. International Journal of Accounting, Business and Management, 2017,4(1), 101-123.

- Chen, Z., Xu, F. Determinants and mechanism of tourist loyalty in rural guesthouse tourism destinations: An empirical analysis based on ABC attitude model. Economic Geography, 2021, (5): 232-240.

- Li, Y., Xiao, L., Yang, J. The impact of Grand Canal landscape value perception on tourists’ intention to protect heritage: A case study of Qingmingqiao Historical and Cultural Block in Wuxi. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment, 2022, (2): 202-208.

- Williams P, Soutar G N. Value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in an adventure tourism context. Annals of Tourism Research, 2009, 36(3): 413-438.

- Gardiner S, King C, Grace D. Travel decision making: An empirical examination of generational values, attitudes, and intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 2013, 33(3): 47-56.

- Meng, HY; Jung, SH; (...); Kim, JH. Perceived tourist values of the Museum of African Art. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 2018 , 28 (5), 375-381.

- Wen, J and Huang, SS. The effects of fashion lifestyle, perceived value of luxury consumption, and tourist-destination identification on visit intention: A study of Chinese cigar aficionados. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2021, 22, 100664.

- Murphy P, Pritchard M P, Smith B. The destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tourism Management, 2000, 21(1): 43-52.

- Li, W., Zhang, H. A conceptual model and empirical study on the perceived value of village tourists: A case study of Zhangguguan Village. Tourism Science, 2010, (2): 55-63.

- Ranjbarian B, Pool J K. The impact of perceived quality and value on tourists’ satisfaction and intention to revisit Nowshahr city of Iran. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 2015, 16(1): 103-117.

- Ban, J; Prideaux, B; (...); Sheehan, B. How service quality and perceived value affect behavioral intentions of ecolodge guests: The moderating effect of prior visit. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 2022, 28(2), 244-257.

- Wang, S; Lai, IKW and Wong, JWC. The impact of pluralistic values on postmodern tourists’ behavioural intention towards renovated heritage sites. Tourism Management Perspectives, 2023, 49, 101175.

- Kim Y H, Kim M, Ruetzler T, et al. An examination of festival attendees’ behavior using SEM. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 2010, 1(1): 86-95.

- Cheng T M, Lu C C. Destination image, novelty, hedonics, perceived value, and revisiting behavioral intention for island tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 2013, 18 (7): 1-18.

- Han, C. The relationship between erceived value and satisfaction of tourism and behavioral intention. Human Geography, 2015, (3): 137-144+150.

- Gursoy D, Gavcar E. International leisure tourists’ involvement profile. Annals of Tourism Research, 2003, 30(4): 906-926.

- Zhang, H., Lu, L. The impact of tourist involvement on tourist destination image perception: a comparison between inbound Anglo tourists and domestic tourists. Acta Geographica Sinica, 2010, 65(12): 1613-1623.

- Aitchison, J. and S. Silvey. The generalization of probit analysis to the case of multiple responses. Biometrika, 1957, 44: 131-140.

- Cheng T M, Lu C C. Destination image, novelty, hedonics, perceived value, and revisiting behavioral intention for island tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 2013, 18 (7): 1-18.

- Ranjbarian B, Pool J K. The impact of perceived quality and value on tourists’ satisfaction and intention to revisit Nowshahr city of Iran. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 2015, 16(1): 103-117.

- Zeithaml V A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 1988, 52(3): 2-22.

- Chan, C. S. (2021). Developing a conceptual model for the post-COVID-19 pandemic changing tourism risk perception. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9824. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Dai, Y., Liu, A., Liu, W., & Jia, L. (2023). Can the COVID-19 risk perception affect tourists’ responsible behavior intention: An application of the structural equation model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(9), 2042-2061. [CrossRef]

- Daye, M., Charman, K., Wang, Y., & Suzhikova, B. (2020). Exploring local stakeholders’ views on the prospects of China’s Belt & Road Initiative on tourism development in Kazakhstan. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(15), 1948-1962. [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2021). Experience and service quality on perceived value and behavioral intention: Moderating effect of perceived risk and fee. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 22(6), 711-737. [CrossRef]

- Haji, S., Surachman, S., Ratnawati, K., & MintartiRahayu, M. (2021). The effect of experience quality, perceived value, happiness and tourist satisfaction on behavioral intention. Management Science Letters, 11(3), 1023-1032. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y., & Kim, S. (2020). A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction,

and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(4), 940-960. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Ye, X., & Ryzhikh, A. (2021). Consumer behavior in China and Russia: Comparative analysis. BRICS Journal of Economics, 2(1), 74-90. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Gong, J., Gao, B., & Yuan, P. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on tourists’ destination preferences: Evidence from China. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103258. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Viet, B., Dang, H. P., & Nguyen, H. H. (2020). Revisit intention and satisfaction: The role of destination image, perceived risk, and cultural contact. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1796249. [CrossRef]

- Pani-Harreman, K. E., Bours, G. J., Zander, I., Kempen, G. I., & van Duren, J. M. (2021). Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’: a scoping review. Ageing & Society, 41(9), 2026-2059. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z., Du, Y., & Li, X. (2023). Homeland, emotions, and identity: Constructing the place attachment of young overseas Chinese relatives in the returned Vietnam-Chinese community. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 984756. [CrossRef]

- TALOŞ, A. M., LEQUEUX-DINCĂ, A. I., PREDA, M., SURUGIU, C., MARECI, A., & VIJULIE, I. (2021). Silver Tourism and Recreational Activities as Possible Factors to Support Active Ageing and the Resilience of the Tourism Sector. Journal of Settlements & Spatial Planning. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C., Huang, Q., Lin, Z., & Chen, Y. (2020). Destination risk perception, image and satisfaction: The moderating effects of public opinion climate of risk. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44, 122-130. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z., & Borbon, N. M. D. (2022). Relationship among tourist experience value and satisfaction towards travel intention behavior framework in celebrities’ former residences in Shaoxing, China. International Journal of Research, 10(5), 83-99.

- Yin, J., Cheng, Y., Bi, Y., & Ni, Y. (2020). Tourists perceived crowding and destination attractiveness: The moderating effects of perceived risk and experience quality. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100489. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Zhao, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., & Luo, N. (2021). Effects of destination resource combination on tourist perceived value: In the context of Chinese ancient towns. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100899. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B., & Lai, Z. (2020). The effect of housing wealth on tourism consumption in China: Age and generation cohort comparisons. Tourism Economics, 26(2), 211-232. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).