Introduction

Morphogenesis is the study of forms, their development and evolution. For physics this program already made certain steps, with models in the language of mathematics, but extending this program to biology is a major challenge. In response to E. Wigner’s “

The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”, I.M. Gelfand stated:

‘’There exists yet another phenomenon which is comparable in its inconceivability with the inconceivable effectiveness of mathematics in physics noted by Wigner - this is the equally inconceivable ineffectiveness of mathematics in biology’’[

1].

Marcel Berger explicitly states: ‘‘

Present models of geometry, even if they are quite numerous, are not able to answer various essential questions. For example: among all possible configurations of a living organism, describe its trajectory (life) in time”[

2]. The challenge can even prove insurmountable: If you observe a plant, it is impossible to find in an algorithmic or otherwise mathematically precise way the mathematical system that created it. “Plants” can be substituted with rocks, galaxies, animals, clouds, ....

A geometrization of physics seems to be an easier task than a geometrization of biology, where history plays a crucial role, be it in development or in an evolutionary context. A biologist works with the discrete (animals, plants, microbes, cells, and DNA, RNA, proteins, …) but knows the continuous in evolution and development. René Thom once said that we can only experience the continuous (space and time), but need the discrete to understand (categories, measurements, …).

An illustrative example of the difference between a mathematical and a biological mind is the Cantor set. The iterative algorithm, where parts of a line are taken away to arrive at the Cantor dust, is mathematically very sound. From a biologist’s point of view, however, the discarded pieces of line neither disappear nor are they lost. They remain firmly connected to all other pieces by historical or other threads (in another place or dimension) and from this perspective continuity is maintained.

Our focus is on a geometric theory of forms and their evolution in the broadest possible sense, including their history. Such theory of forms and morphogenesis must overcome several fundamental challenges.

First, it concerns both natural and abstract forms. Natural forms include everything from the small and smallest (molecules, atoms, quarks, to the infinitely small) to the large and largest (stars, galaxies, black holes, the universe, to the infinitely large) to the meso-scale (plants, animals, rocks, mountains, oceans, …..). Natural forms can be extended to everyday forms and thus include man-made forms (cars, bridges, windows, music, stories, myths, …). They also include more abstract forms, such as inspirations, thoughts and dreams, sensory (and non-sensory) perceptions.

Abstract forms include mathematical objects such as geometric forms, manifolds and categories in the broadest sense. They may also include some expected developments like the extension of the notion of manifold [

3]. Abstract forms also include non-existent objects such as golden mountains and square circles [

4].

Second, it is not only about the pure description of forms, but also about their emergence and their entire history, regardless of whether they are viewed through a discrete or continuous lens, one of the oldest conflicts in human thought. We need the discrete to understand (categories, measurements, …), but experience space and time as continuous. Bifurcations seem to us as discrete, but the underlying manifolds are continuous [

5], much like the biologist’s view on the Cantor set.

Third, the challenge is to deal with individual instances of natural and abstract forms, knowing that mathematics is the science of patterns. When modeling plants or other natural phenomena, one starts from a particular model and applies stochastic methods to obtain more realistic forms, but this is at best a very rough approximation. An example is Pattern Theory [

6,

7,

8] , which focuses on stochastic methods [

9,

10].

When examining a particular plant, it is impossible to find the mathematical model that generated it in an algorithmic or otherwise mathematically precise way. If you study a thousand plants, they will all differ in some way, because their phenotypes are a temporal sequence of adaptations to internal and external stressors acting on the plants. Again, one can replace “plants” with rocks, galaxies, animals, clouds, .... However small the differences may be, there will be differences, and one cannot understand the true diversity of nature by focusing only on patterns. A geometrical theory must consider the individual plants, animals, crystals, galaxies, atoms, ….

Fourth, the relationships between a real plant (or any other object under study) and its model (i.e., any approximation, with arbitrary accuracy), combine much of the first three challenges. But accuracy in science is always finite

1. However small or negligible certain effects may seem, one must consider Dirac’s extension of Archimedes: “

If you pick a flower on Earth, you move the farthest star.” The Point-Theory of Morphogenesis aims to overcome all these challenges and match exactly with the object under study.

On natural forms, D’Arcy Thompson wrote: “

So the living and the dead, things animate and inanimate, we dwellers in the world, and the world in which we dwell - πάντα γα μὰν τὰ γιγνωσκόμενα2 -

are bound alike by physical and mathematical law”[

11]. However, our strategy, our first goal, should be consistent with René Thom’s endeavor “

to construct an abstract, purely geometrical theory of morphogenesis that is independent of the substrate of forms and the nature of the forces that create them”[

5], and with the Unique Rational Science of Gabriel Lamé’s (1795-1870): first find a best-fitting coordinate system, then solve the relevant boundary value problem.

To this end we must decouple form and shape (and their morphogenesis) from any numerical model (decoupling the geo- from the -metric in geometry). The assignment of categories such as dimensions, time, space, maps, grids and number systems can be done in a separate step. The only thing we need to ensure in the first step is the commensurability of forms and shapes, a continuous transformation from one form to any other. Unity in diversity and diversity from unity. Before Pythagoras’ All is Number comes All is One

3

A Plurality of Geometries

The motivation for our geometric methods lies in our observations of the world, and so geometry began. Euclidean geometry in dimension 2 essentially uses the circle as a base or fundamental figure to determine isotropic distances from a human perspective.

In the 19th century, doubts about Euclid’s fifth postulate, Gauss’ study of surfaces in two dimensions, and Riemann’s generalization to the multidimensional case led to Riemannian geometry, which enabled great advances in the study of natural phenomena. The specific choice of rules and metrics in geometry corresponded to specific invariants, and these invariants corresponded to conservation laws in physics.

In almost all developments, the circle is the main concept in the mathematical vocabulary for the study of nature, as the following three examples show:

The circle and the concept of isotropy continue to dominate the study of natural phenomena, often in disguised form. For Richard Feynman, it is one of the most fundamental enigmas in science: “We have in our minds a tendency to accept symmetry as some kind of perfection. In fact, it is the old idea of the Greeks that circles were perfect, and it was rather horrible to believe that the planetary orbits were not circles, but only nearly circles. The difference between being a circle and being nearly a circle is not a small difference; it is a fundamental change so far as the mind is concerned. There is a sign of perfection and symmetry in a circle that is not there the moment the circle is slightly off. That is the end of it, it is no longer symmetrical. Then the question is why it is only nearly a circle - that is a much more difficult question.... So, our problem is to explain where symmetry comes from. Why is nature so nearly symmetrical? No one has any idea why

”[

15].

In the study of natural forms and phenomena, it is by no means self-evident that other creatures, living under different conditions, would arrive at the same geometry with the Euclidean circle as the basic figure. This is one of the main ideas of Finsler geometry, in which the basic figure can be ellipses or other shapes. Riemann had already established that an extension to the fourth power was possible. In the words of Chern, Finsler geometry is Riemannian geometry without the quadratic restriction [

16]. The simplest Riemann-Finsler geometry is given by

and the simplest Minkowski metrics by

with the Euclidean case for

.

Generalized Conic Sections in the Natural Sciences

Our faith in the circle has led to considerable successes in science, but one should not be blinded by success for it can hinder progress. Indeed, science can always progress further when conic sections (circle, ellipse, parabola and hyperbola, or their generalized forms, provide very compact and less complex models.

Galilei and Kepler used conic sections (projectively equivalent to the circle) for the trajectories of projectiles and the orbits of planets.

The generalization of conic sections to higher order, with superparabolas and supercircles (Lamé curves), adds one additional parameter to (4).

The further generalization of Lamé curves to any symmetry via the Superformula, which has its roots in biology and reduces complexity.

The discoveries of Galilei and Kepler (4.) inspired Newton to his laws and methods (based on lines and circles). The generalization of conic sections to higher-order (in the exponents) includes power laws are all higher-order parabolas. These are widely used in the natural sciences in the study of allometry, first systematically studied in biology by Galilei.

Supercircles and superellipses (5.) and more generally Lamé curves, have received much less attention, although the equations were known (e.g., Fermat’s Last Theorem and Barrow’s quasicircular curves [

17]. Gabriel Lamé was the first to systematically study this class of curves, and his motivation was “

to apply Descartes’ beautiful geometry to crystallography”[

18]. The extension to Finsler geometry should therefore be called Riemann-Finsler-Minkowski-Lamé geometry.

In the same way as Euclidean geometry in dimension 2 essentially derives from the circle as ground figure

, Lamé’s supercircles (

are at the basis of the simplest definite Minkowski-Finsler geometries in which 4-fold anisotropies occur,

when considered from a human point of view [

19]. For each supercircle the associated trigonometric functions can be defined, and a Pythagorean theorem applies to any supercircle based on these functions. In recent years superellipses have been successfully used to model tree rings of softwoods [

20,

21], plant leaves [

23], and the cross sections of square bamboos [

24,

25],

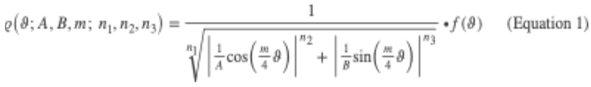

The generalization of supercircles to any symmetry (6) can act as a generic geometric transformation on planar functions (Equation 1) [

26]:

This generates so-called Gielis curves for dimension 2 and the Gielis (hyper)surfaces for dimension 3 (and more) [

27,

28], as basic figures for describing most natural m-fold anisotropies for any

Specific instances of the superformula have parameters

with specific numerical values. The first group

defines symmetry and size, and the second group are the shape parameters

. In the case of supercircles,

and the size is denoted by

, the radius of the circle. A number ϱ

is called an n-tuple, a number with various parameters. The n-tuple may be denoted as f

for the transformation of planar curves

.

Some examples:

The inscribed square is denoted as ϱ

A unit supercircle is denoted as ϱ

The starfish is denoted as ϱ

The circle is denoted as ϱ

For the circle are all 2, and then ϱ is always equal to 1 for A = B. Hence the symmetry parameter can be any natural number, and one can consider a circle a shape without angles ( but also as a square (), or a pentagon (). A continuous transformation from circle to a square or into a pentagram () only requires a change in the shape parameters from to (. To morph a circle into a square or pentagram requires no change in the symmetry parameter and no symmetry is broken.

From the point of view of the natural sciences, the application of Equation 1 to the “most natural” curves and surfaces of Euclidean geometry (e.g., for dimension 2: the circles with

and the logarithmic spirals

among the closed and non-closed curves, respectively), leads to many of the forms that we can observe in nature -in biology, crystallography, physics and chemistry [

28,

29]

5.

In the last ten years, the Superformula has established itself as a solid scientific method. For example, all bamboo leaves and all bird eggs can be defined with arbitrary precision. In total over 40,000 biological shapes have been tested and successfully modeled [

29] with Equation 1. The tree rings of softwoods are a simplified form of Equation 1, and only two parameters are sufficient to describe the changes in the tree rings over the years.

Equation 1 has been applied in Finsler geometry, to model wildfires [

30], and seismic wave propagation [

31], or to generalize constant mean curvature surfaces [

32] and Euler’s elastic curves [

33] for anisotropic cases. It has also led to generalization of the Laplacian, that allows the Fourier projection method to be used to solve boundary value problems in a variety of domains in 2 and 3 dimensions [

34,

35].

The generalization to 3D or higher can be done in different ways, for example, in parametric, spherical or cylindrical coordinates. In the latter case, a generalized cylinder is obtained, whose cross sections can be circles, polygons or starfish. They can change along the height of the cylinder, together with changes of the parameter values in the n-tuple. An example is the stem of a cactus, which changes slightly in each cross section.

The ends of the generalized cylinder or prism can be connected, with or without torsion, leading to the class of Generalized Möbius Listing surfaces or bodies. It is not limited to closed shapes, as the associated trigonometric functions lead to completely new ways of generating sounds and waves in general [

36,

37]. Interestingly, self-intersecting curves (

m is a rational number) produce polyphonic sounds [

38].

From Rigid to Ultraflex

One of the main motivations for Equation 1, is the unified description of a wide range of natural and abstract shapes with a generic geometric transformation, with continuous transformations from circles to squares or starfish, and from spheres, to spindle tori to tori, and more.

A second motivation for Equation 1 is that it can be thought of in terms of a flexible radius. The classical application of geometric methods in the natural sciences start from rigid geometries, with rules for flexibility, through of geometric transformations. Topology has its own rules, e.g., stretching without breaking.

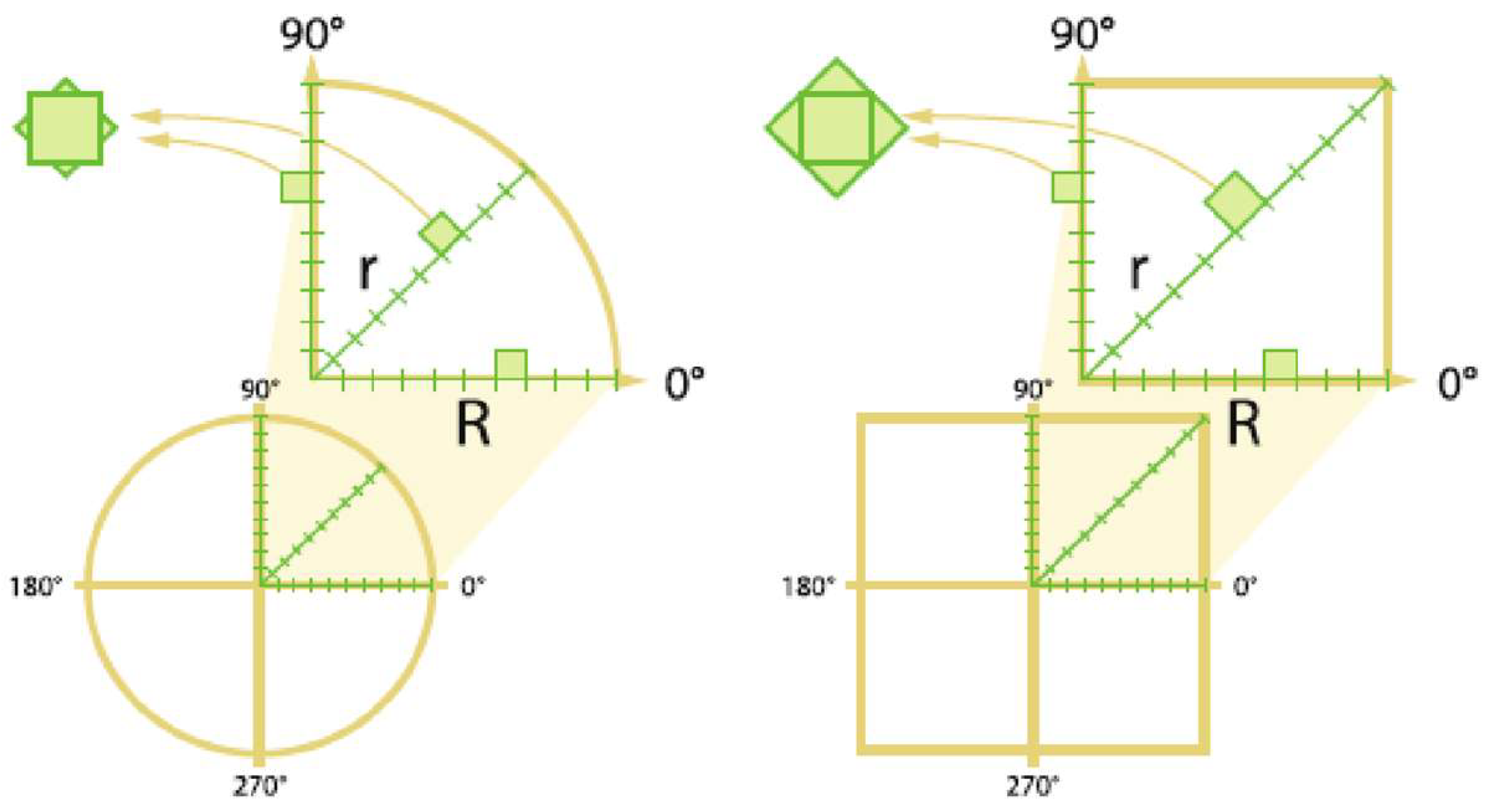

To draw a starfish or a square (

Figure 1), one can use a rubber band or a spring, and Equation 1 tells you how and when to stretch. It will be a unit circle in its own metric, and only for an outside observer, the length of the elastic radius will change. An inner observer will not notice, simply because he or she is also stretching

6. Furthermore, the observers live in their own Circles. It is only a square, if you look at it from the outside,

from a human point of view.

With equation 1 we can turn a circle into a starfish, a flower or a seed, and extensions of Equation 1 can create very wild shapes. But in our imagination, we can go even further and turn a circle or a starfish into anything, including a unicorn or an explosion. That is what we want to model. Then we must go from flexible to ultraflexible, with ultra as in Nec Plus Ultra, the highest possible, the ultimate flexibility.

In Euclid’s Elements a point is defined as that which has no dimension. The first Postulate states that a line can be drawn between any two points and how close or how far apart they are, makes no difference; a line can extend all the way to infinity (the second Postulate). Imagine, however, that we do not connect a point to another point by a line, but define a point as infinitely extensible. Then we can stretch a point to any length, and it is still the same point, that creates a line7. We can stretch this Point-Line to a finite or infinite plane, and this plane to a space. The same point can be stretched into any curve, disk, plane or surface, in any dimension. It can form continuous manifolds but also discrete grids, nets and meshes.

An example from physics is gold, a very ductile (stretchable) material, that it can be drawn into very fine wires. A block of 1cm3 gold, for example, can be stretched into a gold wire of almost 13 km, if the wire thickness is 10 micrometers. Even more: if the wire thickness were 1 micrometer, the gold cube could even be stretched to a length of 100 km. Metals such as copper and platinum are even more ductile than gold.

Then imagine that we have an infinitely stretchable material at our disposal, and we reduce the 1cm3 to a very small size, a point. We can then stretch this point into a finite or infinitely long wire (which is our straight line). This line can in turn be stretched into a plane, a (hyper-)surface or a (hyper-)solid. Our geometry is then made entirely of a stretchable point (or vice versa: any plane or surface can be reduced to a single point).

Note that we do not necessarily define a point as infinitely small; it can have a certain size or other properties, such as being square of starfish-shaped.

Figure 2 shows three double cones, and their cross-section are defined by specific n-tuple of parameters (Equation 1). When one moves along the height axis, the cross-section increases or decreases until it reaches a singularity at the intersection of the cones. During this movement, only one set of parameters in the n-tuple changes, namely the size parameter (

). All other parameters of the n-tuple

(remember: a single superformula number) remain fixed. Size and shape are independent.

Despite the apparent shrinkage of the shape to a size of zero at this singularity, the structural information remains encoded in the parameters of the superformula. The superformula remains invariant even as individual parameters change. The number of dimensions does not increase either; only the values of the n-tuple evolve over time. No information is lost or destroyed. This is not surprising, because it is like lenses and our visual system.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

A Point-Theory of Morphogenesis

A Point may be a fertilized egg that grows into an animal or a tree, a Cosmic Egg

8 that develops into our present universe, a flash of inspiration that evolves into a book about seashells, or a flash of inspiration that gives rise to a Point-Theory of Morphogenesis. All these things can be regarded as Point-Manifolds.

The advantage now is that we have a model which fits the manifold under study with infinite precision; the manifold and the model are identical, and their entire history is also encoded. In this sense it is an ontological model.

Challenge 3. noted that mathematics, the science of patterns, has never been the science of single or individual objects in the natural sciences [

39]. When a unique plant form is given, one cannot reconstruct, in a mathematically precise way, how it came to be. Our earlier goal [

40] was to develop an “abstract” plant including its morphogenesis. We imagined that an abstract tree is different from an abstract cactus, but the mathematical model underlying both is the same, and stands as a model for all plants (like Goethe’s Urpflanz).

However, there is a second possibility: every individual cactus or tree is both a natural and an abstract Point-Cactus or Point-Tree. Every individual person is both an abstract and a natural Point-Person, and we have individual Point-Animals, Point-Cells, Point-Photons, and Point-Galaxies, which allows us to combine the abstract and the individual (mundane or worldly) realizations. This also allows all these Points to be connected in a discrete or continuous way, to form Point-Networks.

Definition, Axioms and Postulates

For a more formal approach to our Point Theory of Morphogenesis, we follow the advice of one of the great geometers of the 20th century, A.N. Alexandrov: “

Retreat to Euclid!” For Alexandrov, Euclid’s geometry provided a universal, visually intuitive foundation that connected mathematics to the cultural and intellectual traditions of ancient Greece. For the study of nature, we can now return to the elegance and universality of these methods, aiming for a minimal set of definitions, axioms and postulates

9.

Euclid begins with axioms stating that things which are equal to the same thing are also equal to one another, and if things coincide with one another, they are equal to one another. However, when considering equal, greater or less, we should be mindful of

Figure 1, our external glasses and our God’s Eye views.

In our Point-view, all things are commensurable in the same way that all supercircles and supercurves are commensurable. They can be measured with a common ruler, namely equation 1 or an ultra-flex ruler. The fifth axiom in the Elements states that the whole is greater than the part, but in a Point, everything can be both whole and part.

In our minimal set only one definition and two postulates are needed, namely:

D1: A point has size and shape,

and

P1. A point is that which has extension

P2. A point is that which has intension

Ex- (P1) and In- (P2) are about points developing into manifolds and increasing in size (extension) but also decrease in size (in- as the opposite of ex-). The extension and intension are understood as Nec Plus Ultra, nothing beyond the infinite and the infinitesimal.

Another motivation for P2 (intension) is the classical meaning of intention. A Point-Seed’s intention is to grow into a plant, and a Point-Termite having evolved from a Point-Termite_Egg intends to contribute to the well-being of the Point-Termite_Mound

10.

A critical look at axiomatic systems also reveals intent. Euclid’s axioms are rules, with the intention that others apply or follow these rules. The geometer using Euclid’s axioms and theorems to study abstract or natural shapes, has the intention to follow these rules.

The use of -tension in both axioms also refer to physical tension

11. Although any stretching is possible in our Point-theory, under natural (earthly or cosmological) conditions both the flexible radius of natural superellipses or supershapes and the drawing of gold wires are finite.

These two examples also serve another purpose, namely, to reveal the implicit conventions in the language of science (in the broadest sense). Golden Mountains and Square Circles have served as examples of non-existent objects under certain rules and requirements, such as having the properties square and round at the same time [

4].

But for the square circle, these are additional constraints, where square and round are defined from a human point of view. Supercircles are Point-Manifolds that give existence to square circles. Likewise, a Point-Gold_Nugget developing into a Golden Mountain gives existence to this abstract object.

Numbers and Grids

To the Point-Theory of Morphogenesis, additional elements or constraints such as space and time can be introduced in a next step

12. Time for example, requires the notion of a totally ordered set [

42]. Euclid’s axioms and the exclusive requirement of ruler and compass leads to Euclid’s Elements, and from there to the various generalizations that followed, with the circle and n-sphere based on our human thoughts. Studying nature through a circular lens, leads to questions like Feynman’s enigma: “

Why is nature so nearly symmetrical? No one has any idea why.”

The introduction of concepts such as space, time, symmetry and dimensions, depends on our human perspective. From there, we develop theories and methods and use them as the basis for our study of nature, with our external glasses and our God’s Eye views. Mathematicians and scientists use many such implicit assumptions, and the Axiom of Indistinguishability, hidden in plain sight in quantum theory, is one of the best examples.

From the perspective of generalized conic sections, things look very different. The observation of superparabolas, superellipses and supercurves in nature leads to the use of generalized conic sections as the preferred method. Nature is not nearly symmetrical.

The Point-Theory with postulates P1 and P2 is the first step, but D1 (points with shape and size) is already prepares for the next step. The assignment of grids, meshes and numbers to the Point-Manifold, can be done with continuous maps or discrete grids, and one can choose between a variety of number systems

13.

To combine differential and difference calculus from the start, Time Scales introduced by Stefan Hilger [

43,

44], can be used. Such Time Scales can include real and rational numbers, but also any continuous or discrete scale, including Cantor dust. A proposed method for combining Point-Manifolds are R-functions [

45]. They are directly related to supercircles and are naturally suited to multivalued logic [

46,

47], as an extension of the simple binary logic. Equation 1 and a flexible radius inspired the generalization of the Laplacian [

33,

37,

48], so that relevant boundary value problems can be solved on any normal polar domain.

Conclusion

One of the advantages of Equation 1 identified by geometers is that it describes the shape and its development starting from a central point. The (Nec Plus Ultra)-flex extension allows all possible and conceivable transformations from a single Point.

The results of our Point-Theory of Forms and their Genesis include Darwin’s endless forms most beautiful, but also dreams, thought patterns, thinking kernels [

49] and square circles

14. All things, indeed, the known and the unknown, πάντα γὰρ μὰν τὰ γιγνωσκόμενα καὶ τὰ ἀγνοούμενα.

Using the idea of an infinitely flexible point, a Point-Theory of Morphogenesis is constructed that completely and uniquely identifies the object or manifold under study. Model

Manifold, and in this sense, it is ontologically perfect

15.

Notes

| 1 |

10987654321 may seem a big number, but it is hardly any closer to infinity than 100. |

| 2 |

All things indeed, that are known. |

| 3 |

Barbara McClintock: Basically everything is one. There is no way in which you draw a line between things. What we normally do is to make these subdivisions, but they are not real. Our educational system is full of subdivisions that are artificial, that shouldn’t be there [ 12]. |

| 4 |

In this sense, quantum mechanics is a complexification of Ptolemy’s epicycles [ 14]. |

| 5 |

Even our universe itself: The space-time metrics of Robertson-Walker types originating from formal deformations of the theorem of Pythagoras are formally similar to supertransformations (Eq1) of Euclidean circles [ 28]. |

| 6 |

The Lorentz-Fitzgerald transformation of Special Relativity is a special case of Equation 1. |

| 8 |

Lemaître’s Primeval atom or cosmic egg, giving rise to our Universe. |

| 9 |

“Examples, problems, and solutions come first. …In developing and understanding a subject, axioms come late. Then in the formal presentations, they come early” [ 41]. |

| 10 |

One counterargument is that the explosion of fireworks is not intentional in the fireworks, but it is intentional in those handling (or mishandling) the fireworks. |

| 11 |

Gabriel Lamé was considered by Carl-Friedrich Gauss as the best French mathematician of his time. This makes sense, since, among many others results, Lamé was the first to study superellipses systematically, and his work on curvilinear coordinates led Elie Cartan to name Lamé one of the cofounders (with Gauss and Riemann) of Riemannian geometry, He is also one of the founding fathers of elasticity theory. |

| 12 |

We focus here only on more classical and differential/difference geometry, but Points can also be (operator) algebras as in non-commutative geometry (where classical points have no meaning). |

| 13 |

considerations of the Infinite one should separate the pure (Nec Plus Ultra) extension (P1) and intension (P2) of Points before and after the introduction of numbers and numerical systems to the Point-Manifolds . |

| 14 |

For nothing would a geometrician wonder so much as if the diagonal became measurable (with the side). οὺθὲν γἀρ ἂν οὕτωϛ θαυμάσειεν ἀνὴρ γεωμετρικὸϛ ὠϛ εὶ γένοιτο ή διάμετροϛ μετρητή (Aristotle) [ 50]. |

| 15 |

...ἀλλὰ τὴν μὲν πλεῖστα ἰδοῦσαν εἰς γονὴν ἀνδρὸς γενησομένου φιλοσόφου ἢ φιλοκάλου ἢ μουσικοῦ. … The soul that has seen the most (of truth) shall be planted in the seed of a man who will become a philosopher (φιλόσοφος) or a lover of beauty (φιλόκαλος), or a man devoted to the Muses and to love (Plato) [ 51]. |

References

- Gelfand.

- Berger, M. A panoramic view of Riemannian geometry; Springer, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chern, S.S. Foreword to Handbook of Differential Geometry; Volume I (eds. Dillen and Verstraelen); North-Holland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zalta, E. Abstract objects: An introduction to axiomatic metaphysics (No. 160); Springer, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, R. Structural stability and morphogenesis; CRC press.

- Grenander, U. Elements of pattern theory; JHU Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grenander, U.; Chow, Y.S.; Keenan, D.M. Hands: A pattern theoretic study of biological shapes (Vol. 2); Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grenander, U. Calculus Of Ideas, A: A Mathematical Study Of Human Thought; World Scientific.

- Mumford, D. Pattern theory: a unifying perspective. In First European Congress of Mathematics: Paris, July 6-10, 1992 Volume I Invited Lectures (Part 1); Birkhäuser Basel, 1994; pp. 187–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, D.; Desolneux, A. Pattern theory: the stochastic analysis of real-world signals; CRC Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.A.W. On growth and form; Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara McClintock’s.

- Boccaletti, D. Epicycles of the Greeks to Kepler’s ellipse and the breakdown of the circle paradigm. Cosmology through time: ancient and modern cosmology in the meditteranean area; Monte Porzio Catone (Rome),, 18–20 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yuri, I. Manin Time and Periodicity from Ptolomy to Schrödinger: Paradigm shifts versus continuity in the history of Mathematics. Geometry in history 2019, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Feynman, R.P. Feynman lectures on computation; CRC Press, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Chern, S.S. Foreword to Handbook of Differential Geometry; Volume I (eds. Dillen and Verstraelen); North-Holland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, I. Geometrical Lectures, Explaining the Generation, Nature and Properties of Curve Lines. He used these curves to illustrate tangents and differentiation in higher order curves in Lecture X.

- Lamé, G. Examen des différentes méthodes employées pour résoudre les problèmes de géométrie. Mme. Ve. Courcier, imprimeur-libraire. 1818. [Google Scholar]

- Verstraelen, L. A concise mini history of geometry. Kragujevac Journal of Mathematics 2014, 38, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P. J. , et al. Capturing spiral radial growth of conifers using the superellipse to model tree-ring geometric shape. Frontiers in plant science 2015, 6, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. , et al. Ellipse or superellipse for tree-ring geometries? Evidence from six conifer species. Trees 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W. , et al. Superellipse Equation Describing the Geometries of Abies alba Tree Rings. Plants 2024, 13, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y. , et al. An elliptical blade is not a true ellipse, but a superellipse–Evidence from two Michelia species. Journal of Forestry Research 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gielis, J. De uitvinding van de Cirkel (Dutch); (2003) Inventing the Circle (English); Geniaal Publishing: Antwerp, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W. , et al. A superellipse with deformation and its application in describing the cross-sectional shapes of a square bamboo. Symmetry 2020, 12, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielis, J. A generic geometric transformation that unifies a wide range of natural and abstract shapes. American journal of botany 2003, 90, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraelen, L. A concise mini history of geometry. Kragujevac Journal of Mathematics 2014, 38, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesen, S.; Verstraelen, L. On growth and form and geometry I. Kragujevac Journal of Mathematics 2012, 36, 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gielis, J.; Shi, P.; Beirinckx, B.; Caratelli, D.; Ricci, P.E. Lamé-Gielis curves in biology and geometry. In Proceedings of the Int.Conf. Riemannian Geometry and Applications (RIGA 2021), Bucharest, Romania, January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Javaloyes, M.Á.; Pendás-Recondo, E.; Sánchez, M. Gielis superformula and wildfire models. In Proceedings of the ISSBG 2023; Geniaal Press: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yajima, T.; Nagahama, H. Finsler geometry of seismic ray path in anisotropic media. Proc. R. Soc. A 2009, 469, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koiso, M.; Palmer, B. Equilibria for anisotropic surface energies and the Gielis formula. Forma Japanese Society on Form 2008.

- Palmer, B.; Pámpano, A. Classification of planar anisotropic elasticae. Growth and Form 2020, 1, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalini, P.; Patrizi, R.; Ricci, P.E. The Dirichlet problem for the Laplace equation in a starlike domain of a Riemann surface. Numerical Algorithms 2008, 49, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caratelli, D.; Ricci, P.E. The Dirichlet problem for the Laplace equation in a starlike domain. Lecture Notes TICMI, Tbilisi, Georgia 2009, 10, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gielis, J. , et al. The common descent of biological shape description and special functions. In Differential and Difference Equations with Applications: ICDDEA, Amadora, Portugal, June 2017; Springer, 2018; Springer, 2018; pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, P.E.; Gielis, J. From Pythagoras to Fourier and from geometry to nature; Athena Publishing, 2022; ISBN 978-90-832323-1-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D.; Bunyard, R.; Gielis, J. Pitch And Timbre Of Supershape Oscillators. Symmetry: Culture & Science 2024, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Gielis, J. Conquering Mount Improbable. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Square Bamboos and the Geometree (ISSBG 2022); Athena Publishing, Amsterdam; 2023; pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oystaeyen, F.; Gielis, J.; Ceulemans, R. Mathematical aspects of plant modeling. Scripta Botanica Belgica 1996, 13, 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh, R. What is mathematics, really? Oxford University Press.

- Van Oystaeyen, F. Time-Ordered Momentary States of the Universe and a Dynamic Generic Model of Reality: Étale Over a Dynamic Non-Commutative Geometry. Growth and Form 2023, 4, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, S. Analysis on measure chains—a unified approach to continuous and discrete calculus. Results in Mathematics 1990, 18, 18–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, M.; Georgiev, S.G. Multivariable dynamic calculus on time scales; Cham: Springer, 2016; pp. 449–515. [Google Scholar]

- Fougerolle, Y. D. , et al. Boolean operations with implicit and parametric representation of primitives using R-functions. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2005, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielis, J.; Grigolia, R. Lamé curves and Rvachev’s R-functions. Reports of enlarged sessions of the Seminar of I. Vekua Institute of Applied Mathematics.-Tbilisi 2022, 37, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Grigolia, R. Three-Valued Gödel Logic With Constants and Involution for Application to R-Functions. 1st International Symposium on Square Bamboos and the Geometree (ISSBG 2022), November 2023; Athena Publishing, 2023; pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gielis, J.; Caratelli, D.; Tavkhelidze, I. Rational Science, Unique and Simple. Proceedings of the ISSBG 2023. Geniaal Press: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- He, M. Beyond D’Arcy Thompson’s ‘Theory Of Transformations’ and ‘Laws Of Growth’: Future Challenges of Transforming “Invisible” to “Visible”. In International Symposium Square Bamboos and the Geometree; Athena Publishing: Amsterdam, 2023; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book 1.

- Plato, Phaedrus 248d.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).