1. Introduction

The cornea exhibits dense sensory innervation, predominantly supplied by the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, which contributes to epithelial turnover, neurotrophic support, reflex lacrimation, and the orchestration of wound healing mechanisms [

1]. As seen in neurotrophic keratopathy (NK), damage to corneal nerves disrupts these mechanisms, leading to persistent epithelial defects and potential corneal perforation [

2].Emerging evidence suggests that topical insulin may facilitate corneal healing by stimulating epithelial proliferation, reducing inflammation, and restoring cellular homeostasis.

1.1. Anatomy of the Cornea

The anterior segment is composed of the conjunctiva, cornea, lens, ciliary body, iris, and aqueous humor. The cornea and sclera form the outer protective layer of the eye. The cornea is a transparent, avascular tissue that contributes approximately two-thirds of the eye’s refractive power (40–44 D) and has a 1.376 refractive index. The cornea is horizontally round, convex, and aspheric. The confines of the anterior curve are 7.8 mm, and the posterior curve is roughly 6.5 mm [

3].

1.2. Corneal Histology

The corneal surface is composed of a multi-layered squamous epithelium that does not undergo keratinization, particularly at the periphery. Basal epithelial cells exhibit a polygonal morphology, transitioning into progressively flattened cells as they approach the superficial strata. Within the epithelial layers, immune-responsive Langerhans cells can be observed, typically identifiable by CD1a expression. Bowman’s layer contributes significantly to the anterior stroma. The central stroma, which constitutes approximately 90% of the corneal thickness, is acellular and contains uniformly spaced collagen fibrils interspersed with mucoproteins and glycoproteins—essential components responsible for maintaining corneal transparency. This layer measures approximately 8 to 14 microns in thickness and lacks regenerative capacity. Descemet’s membrane, synthesized by corneal endothelial cells, measures around 10–12 microns in adults and also does not regenerate after injury. The innermost layer, the endothelium, is composed of a single layer of flattened cells that play a vital role in maintaining corneal deturgescence through active ionic transport mechanisms, thereby ensuring tissue transparency [

4].

1.3. Corneal Innervation and Sensation

The cornea receives extensive sensory innervation, accompanied by a smaller proportion of autonomic fibers. These nerve fibers originate primarily from the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. At the corneal periphery, both unmyelinated C fibers and myelinated Aδ fibers penetrate the stroma. As they extend toward the central cornea, they lose their myelin sheath, a physiological adaptation that contributes to maintaining corneal transparency [

2]. Corneal innervation plays a vital role in promoting tear secretion, blinking reflexes, and the release of trophic factors necessary for epithelial maintenance. When corneal nerves are damaged, these processes are disrupted, leading to reduced corneal sensitivity, persistent epithelial defects, and, in severe cases, corneal perforation [

5]. Approximately 20% of the sensory fibers are mechanoreceptors that detect mechanical stimuli and transmit sharp pain signals through thin myelinated Aδ fibers. Around 70% are polymodal nociceptors that respond to chemical mediators (e.g., acetylcholine, prostaglandins, bradykinin), thermal, and mechanical stimuli via slow-conducting unmyelinated C fibers [

6]. The remaining 10% are cold thermoreceptors that are activated by tear film evaporation or exposure to cold air or solutions, and signal through both Aδ and C fibers [

7].

1.4. The Involvement of Insulin in the Corneal Healing Process

Insulin is a hormone with an essential role in cellular metabolism, closely related to the insulin growth factor (IGF), which is capable of stimulating keratinocyte migration. At the ocular surface, insulin stimulates the proliferation and migration of corneal epithelial cells and the synthesis of growth factors involved in tissue regeneration and significantly reduces inflammatory biomarkers [

8]. The mechanism by which insulin contributes to the regeneration of the corneal epithelium is not fully understood, and the optimal dose has not yet been established in studies. Bartlett et al. applied eye drops of insulin in concentrations of 100 IU/mL to eight healthy eyes and demonstrated the safety of topical insulin in the form of drops [

9].

The Mackie classification stages the severity of the lesions as follows [

10]

:

Table 1.

The Mackie classification [

10].

Table 1.

The Mackie classification [

10].

| Stage |

Clinical Features |

| Stage 1 |

dry and cloudy corneal epithelium, the presence of superficial punctate keratopathy and edema |

| Stage 2 |

recurrent and/or persistent epithelial defects with an oval or circular shape in the upper half of the cornea. |

| Stage 3 |

corneal ulcer with stromal involvement, stromal melting phenomena, and progression to corneal perforation. |

2. Results

For this review, a systematic search was performed in PubMed using the terms: “Insulin Eye Drops” OR “Topical Insulin” AND “Neurotrophic Keratopathy” OR “Corneal Ulcer”. We selected studies published between 2020 and 2025. Included studies were analyzed according to the method used, number of patients, dose administered, and reported outcomes.

Inclusion criteria

Clinical studies (RCTs, observational, case series) evaluating the effect of topical insulin on neurotrophic keratopathy.

Preclinical studies (in vitro, animals) exploring the mechanism of action of insulin in corneal healing.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews synthesizing relevant data on ophthalmic insulin.

Clinical guidelines mentioning insulin as a possible therapeutic option.

Exclusion criteria

Studies analyzing systemic insulin without ophthalmological applicability

Studies on other corneal conditions not relevant to neurotrophic keratopathy.

Letters to the editor, opinions, and articles without peer review.

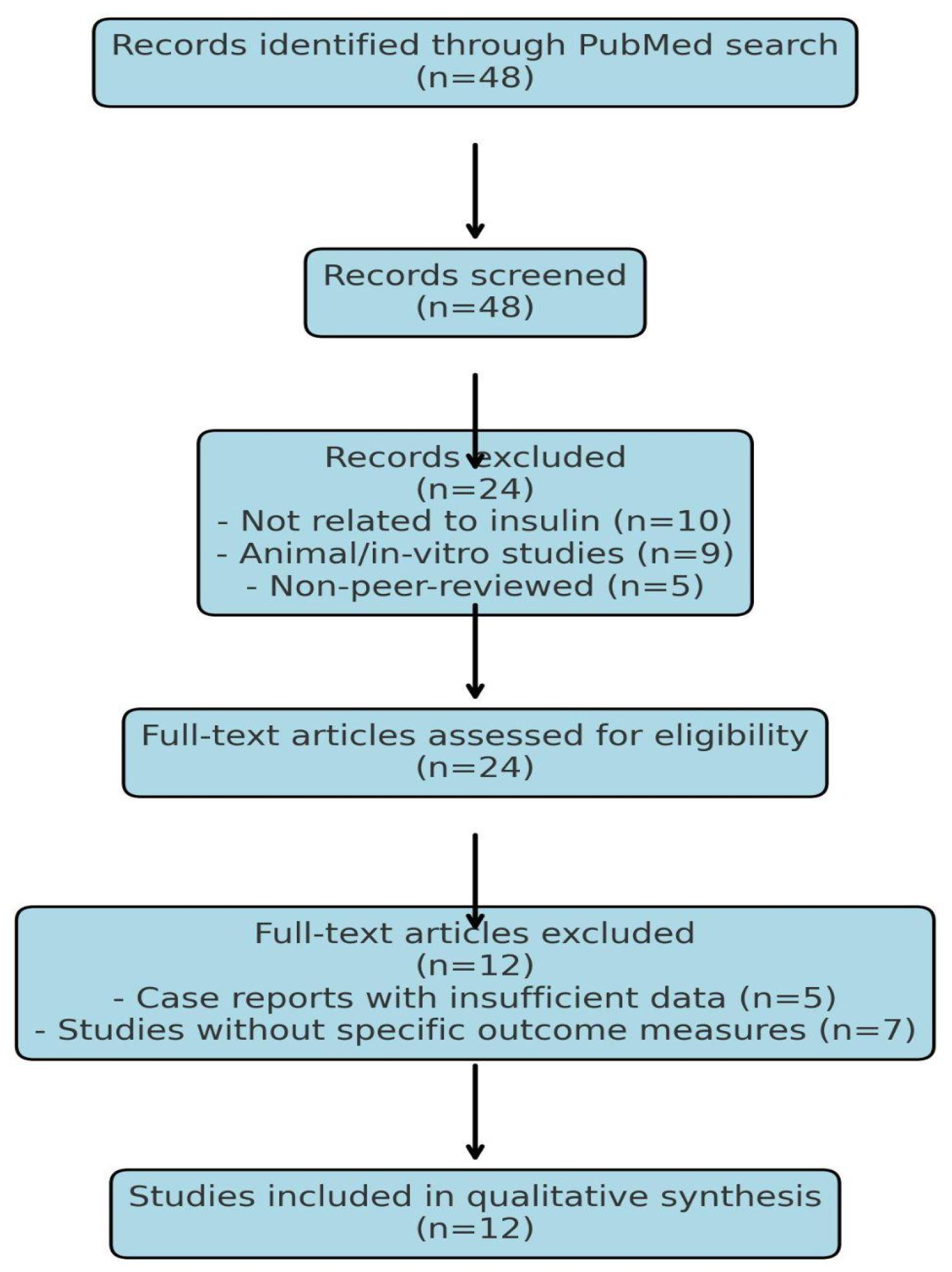

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed to identify relevant studies published between 2020 and 2025. The search was performed using the following key terms and Boolean operators: (“Insulin Eye Drops” OR “Topical Insulin”) AND (“Neurotrophic Keratopathy” OR “Corneal Ulcer”).

Filters were applied, such as “Include only human studies”, “Exclude animal studies and in vitro research,” and “Select clinical trials, observational studies, case reports, and systematic reviews.”

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Clinical studies (randomized controlled trials, observational studies, case series) evaluating topical insulin for neurotrophic keratopathy

- Preclinical studies investigating the mechanism of action of insulin in corneal wound healing

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses summarizing the efficacy of insulin in ocular surface pathology

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies analyzing systemic insulin therapy without ophthalmic application

- Research on other corneal diseases without direct relevance to neurotrophic keratopathy

- Editorials, letters to the editor, and non-peer-reviewed articles

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for (“Insulin Eye Drops” OR “Topical Insulin”) AND (“Neurotrophic Keratopathy” OR “Corneal Ulcer”).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for (“Insulin Eye Drops” OR “Topical Insulin”) AND (“Neurotrophic Keratopathy” OR “Corneal Ulcer”).

The literature search and study selection followed PRISMA guidelines, and no automated screening tools (e.g., Rayyan, Covidence) were used.

Table 2.

Summary of Selected Studies on Topical Insulin for Neurotrophic Keratopathy Treatment.

Table 2.

Summary of Selected Studies on Topical Insulin for Neurotrophic Keratopathy Treatment.

| Study |

Type of Study |

Patients |

Insulin Dosage |

Treatment Duration |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

Adverse Effects |

| Soares et al. (2022) |

Retrospective clinical study |

21 eyes with refractory NK |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

7-45 days |

90% complete re-epithelialization, improved BCVA, no side effects. |

Small sample size, no long-term follow-up. |

None reported. |

| Khilji et al. (2023) |

Case report |

1 patient (64 y/o, NK post-herpetic) |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

2 months |

Full re-epithelialization, significant improvement in corneal integrity. |

Single case study, no control group. |

None reported. |

| Jaworski et al. (2024) |

Systematic review |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Comprehensive analysis of insulin’s mechanism in NK treatment. |

No direct patient data, theoretical analysis. |

N/A |

| Eleiwa et al. (2024) |

Clinical study |

18 patients post-diabetic vitrectomy |

1 IU/mL, 3x/day |

6 weeks |

85% epithelial healing, improved corneal transparency. |

Limited sample size, no RCTs. |

None reported. |

| Moin et al. (2024) |

Narrative review |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Summary of insulin’s efficacy in ocular surface disease management. |

No patient data, theoretical analysis. |

N/A |

| Mancini et al. (2024) |

Clinical study |

10 patients with refractory NK |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

Improved corneal healing, best results with combination therapy (insulin + contact lens). |

Limited to refractory cases, no placebo control. |

None reported. |

| Giannaccare et al. (2024) |

Clinical study |

8 patients with recalcitrant NK |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

75% full recovery, hyper-CL lenses improved insulin absorption. |

Small sample size, needs larger trials. |

None reported. |

| Wouters et al. (2024) |

Systematic review |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Summarizes current evidence on topical insulin for neurotrophic epithelial defects. |

No direct clinical application. |

N/A |

| Le Nguyen et al. (2022) |

Laboratory study |

N/A |

Artificial tear vehicle with insulin |

N/A |

Stability and microbiological safety of insulin eye drops in long-term storage. |

Preclinical data, no human trials. |

Not applicable. |

| Krolo et al. (2024) |

Review article |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Overview of insulin’s role in ocular surface restoration. |

General overview, no new clinical insights. |

N/A |

| Eleiwa et al. (2025) |

Pediatric case study |

1 patient with congenital insensitivity to pain (CIPA) |

1 IU/mL, 3x/day |

6 weeks |

Improvement in corneal healing, long-term follow-up needed. |

Single pediatric case, long-term effects unknown. |

None reported. |

| Fu & Zeppieri (2024) |

Clinical discussion |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Discusses neurotization as an alternative or adjunct therapy for NK. |

Discussion-based, no clinical trials. |

N/A |

A comparative analysis of included studies highlights the promising efficacy of topical insulin in the treatment of neurotrophic keratopathy (NK). Most of the clinical studies and case reports reviewed report high rates of re-epithelialization and improvement of corneal transparency, without significant adverse effects

[11]. Reported studies indicate a healing rate between 75% and 90% in patients treated with topical insulin. No major adverse effects have been reported following the use of topical insulin [

12]

. The treatment duration ranged from 7 days to 8 weeks, depending on the severity of corneal lesions and response to therapy [

13]. Studies suggest that the combination treatment (insulin + Hyper-CL therapeutic lenses) improves absorption and clinical effects. One possible explanation for the improved outcomes observed with insulin and therapeutic lenses is enhanced bioavailability and prolonged contact time with the corneal epithelium, leading to increased cellular uptake and sustained release of insulin over time [

14].

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Clinical Studies on Topical Insulin in Neurotrophic Keratopathy.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Clinical Studies on Topical Insulin in Neurotrophic Keratopathy.

| Study |

Number of patients |

insulin dose |

period of treatment |

Cure rate |

Comments |

| Topical Insulin-Utility (Soares et al., 2022) |

10 |

1 IU/ml, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

Complete epithelial healing in 80% of patients after 6-8 weeks |

Effective for refractory KN |

| Insulin in KN post-vitrectomie (Eleiwa et al., 2024) |

18 |

1 IU/ml, 3x/day |

6 weeks |

Significant improvement in 85% of patients after 6 weeks |

Positive response in vitrectomy patients |

| Insulin in pediatric KN (Eleiwa et al., 2025) |

4 |

1 IU/ml, 3-4x/day |

6 weeks-8 weeks |

Epithelial healing in 75% of patients after 6-8 weeks |

Promising results in children |

| Topical insulin used alone or in combination with drug-depository contact lens for refractory cases of neurotrophic keratopathy. |

12 |

1 IU/ml, 4x/day |

12 weeks |

Epithelial healing in 90% of patients after 6-10 weeks |

Combination therapy accelerates healing |

| Combined Use of Therapeutic Hyper-CL Soft Contact Lens and Insulin Eye Drops for the Treatment of Recalcitrant Neurotrophic Keratopathy. |

8 |

1 IU/ml, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

Epithelial healing in 75% of patients after 6-8 weeks |

Hyper-CL lenses improve epithelial stability |

2.4. Comparison (C): Standard Treatments for Neurotrophic Keratopathy (NK)

Neurotrophic keratopathy (NK) is a challenging condition characterized by impaired corneal healing due to sensory nerve damage. Conventional treatments aim to restore corneal integrity, reduce inflammation, and promote epithelial regeneration [

2,

13].

Table 4.

Summary of Evidence on the Efficacy of Topical Insulin for Neurotrophic Keratopathy.

Table 4.

Summary of Evidence on the Efficacy of Topical Insulin for Neurotrophic Keratopathy.

| Study |

number of patients |

insulin dose |

period of treatment |

Cure rate |

Comments |

| Topical Insulin-Utility (Soares et al., 2022) |

10 |

1 IU/ml, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

Complete epithelial healing in 80% of patients after 6-8 weeks |

Effective for refractory KN |

| Insulin in KN post-vitrectomie (Eleiwa et al., 2024) |

18 |

1 IU/ml, 3x/day |

6 weeks |

Significant improvement in 85% of patients after 6 weeks |

Positive response in vitrectomy patients |

| Insulin in pediatric KN (Eleiwa et al., 2025) |

4 |

1 IU/ml, 3-4x/day |

6 weeks-8 weeks |

Epithelial healing in 75% of patients after 6-8 weeks |

Promising results in children |

| Topical insulin used alone or in combination with drug-depository contact lens for refractory cases of neurotrophic keratopathy. |

12 |

1 IU/ml, 4x/day |

12 weeks |

Epithelial healing in 90% of patients after 6-10 weeks |

Combination therapy accelerates healing |

| Combined Use of Therapeutic Hyper-CL Soft Contact Lens and Insulin Eye Drops for the Treatment of Recalcitrant Neurotrophic Keratopathy. |

8 |

1 IU/ml, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

Epithelial healing in 75% of patients after 6-8 weeks |

Hyper-CL lenses improve epithelial stability |

Table 5.

Comparison of Topical Insulin vs. Standard Treatments.

Table 5.

Comparison of Topical Insulin vs. Standard Treatments.

| Treatment |

Mechanism of Action |

Efficacy |

Challenges |

| Artificial Tears |

Hydration, mechanical protection |

Symptomatic relief only |

Does not promote healing |

| Growth Factors (NGF, EGF) |

Stimulate epithelial and nerve regeneration |

High (NGF shows nerve regeneration) |

Expensive, limited access |

| Autologous Serum Eye Drops |

Supply growth factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines |

Moderate to high |

Requires preparation from patient’s blood |

| Corneal Neurotization |

Restores corneal sensation via nerve grafts |

High (permanent effect) |

Invasive, requires surgery |

| Topical Insulin |

Stimulates epithelial proliferation, reduces inflammation |

Promising (75-90% healing rates in studies) |

Optimal dosage/duration not yet standardized |

Large-scale randomized clinical trials are needed to establish the optimal dose and exact duration of treatment. Future research should explore possible synergies with other therapies to maximize clinical benefits. In conclusion, topical insulin emerges as a promising and affordable treatment for NK, with a high safety profile and favorable outcomes in corneal epithelial regeneration.

3. Discussion

The largest clinical trials of ophthalmic insulin have involved 10–18 patients, highlighting the need for research on larger sample sizes

[11,13]. Case studies examine the effects of insulin on 1–4 patients [

15]. The standard dose used in most clinical trials is 1 unit/mL, administered 3 to 4 times daily [

13]. The duration of treatment varies between 6 and 12 weeks, with most studies reporting epithelial healing after 6–8 weeks

[12]. Patients treated with insulin and therapeutic lenses had faster results (6 weeks vs. 8–10 weeks in insulin therapy alone) [

13].

There are no long-term clinical studies yet (more than 3 months of follow-up) [

11]. Although most studies included in this review report high rates of re-epithelialization and the absence of major adverse effects associated with the use of topical insulin, the duration of post-treatment follow-up is limited. The longest follow-up period identified was 2 months (8 weeks) in the study by Khilji et al. (2023), in which a patient with post-herpetic neurotrophic keratopathy (NK) was treated and followed for 2 months [

15].

In other studies, follow-up durations ranged from 7–45 days in the study of

Soares et al. (2022) [

11], 6 weeks in

Eleiwa et al. (2024) [13],

Eleiwa et al. (2025), and 8 weeks in the studies by

Mancini et al. (2024) [14] and Giannaccare et al. (2024) [12].

The lack of long-term studies (more than 3–6 months) limits the ability to assess late effects of topical insulin, such as possible corneal structural changes over time, risk of angiogenesis or corneal fibrosis, and potential decrease in efficacy with prolonged use [

11,

13,

14].

Current data suggest that topical insulin is safe and well tolerated, but studies with extended follow-up (>6 months – 1 year) are needed to confirm the safety profile and possible late adverse effects [

12,

15]. Future studies should include detailed clinical follow-up and histological analyses to determine long-term effects on the cornea [

11,

16]. The evidence reviewed in this study suggests that topical insulin is a promising therapy for promoting corneal healing in neurotrophic keratopathy [

11,

12,

13]. While clinical studies have demonstrated significant epithelial regeneration, optimal dosing and long-term safety require further investigation [

11,

16]. Compared to conventional treatments such as autologous serum or growth factor therapy, insulin eye drops provide a cost-effective alternative with the potential for widespread application [

12,

17]. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are necessary to establish optimal dosing, assess long-term safety, and determine the role of topical insulin as a standardized therapy for neurotrophic keratopathy [

18].

4. Study Limitations and Future Research Prospects

Although the current results suggest that topical insulin may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for neurotrophic keratopathy (NK), there are still insufficiently explored aspects, especially regarding the safety of long-term use and potential adverse effects [

11,

16]. One of the main concerns is related to the possibility of corneal angiogenesis and stromal fibrosis, phenomena that could compromise corneal transparency and, implicitly, visual function [

17,

18].

Table 6.

Overview of Clinical Studies on Topical Insulin for Neurotrophic Keratopathy: Methodology, Outcomes, Limitations, and Adverse Effects.

Table 6.

Overview of Clinical Studies on Topical Insulin for Neurotrophic Keratopathy: Methodology, Outcomes, Limitations, and Adverse Effects.

| Study |

Type of Study |

Patients |

Insulin Dosage |

Treatment Duration |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

Adverse Effects |

| Soares et al. (2022) |

Retrospective clinical study |

21 eyes with refractory NK |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

7-45 days |

90% complete re-epithelialization, improved BCVA, no side effects. |

Small sample size, no long-term follow-up. |

None reported. |

| Khilji et al. (2023) |

Case report |

1 patient (64 y/o, NK post-herpetic) |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

2 months |

Full re-epithelialization, significant improvement in corneal integrity. |

Single case study, no control group. |

None reported. |

| Jaworski et al. (2024) |

Systematic review |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Comprehensive analysis of insulin’s mechanism in NK treatment. |

No direct patient data, theoretical analysis. |

N/A |

| Eleiwa et al. (2024) |

Clinical study |

18 patients post-diabetic vitrectomy |

1 IU/mL, 3x/day |

6 weeks |

85% epithelial healing, improved corneal transparency. |

Limited sample size, no RCTs. |

None reported. |

| Moin et al. (2024) |

Narrative review |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Summary of insulin’s efficacy in ocular surface disease management. |

No patient data, theoretical analysis. |

N/A |

| Mancini et al. (2024) |

Clinical study |

10 patients with refractory NK |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

Improved corneal healing, best results with combination therapy (insulin + contact lens). |

Limited to refractory cases, no placebo control. |

None reported. |

| Giannaccare et al. (2024) |

Clinical study |

8 patients with recalcitrant NK |

1 IU/mL, 4x/day |

8 weeks |

75% full recovery, hyper-CL lenses improved insulin absorption. |

Small sample size, needs larger trials. |

None reported. |

| Wouters et al. (2024) |

Systematic review |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Summarizes current evidence on topical insulin for neurotrophic epithelial defects. |

No direct clinical application. |

N/A |

| Le Nguyen et al. (2022) |

Laboratory study |

N/A |

Artificial tear vehicle with insulin |

N/A |

Stability and microbiological safety of insulin eye drops in long-term storage. |

Preclinical data, no human trials. |

Not applicable. |

| Krolo et al. (2024) |

Review article |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Overview of insulin’s role in ocular surface restoration. |

General overview, no new clinical insights. |

N/A |

| Eleiwa et al. (2025) |

Pediatric case study |

1 patient with congenital insensitivity to pain (CIPA) |

1 IU/mL, 3x/day |

6 weeks |

Improvement in corneal healing, long-term follow-up needed. |

Single pediatric case, long-term effects unknown. |

None reported. |

| Fu & Zeppieri (2024) |

Clinical discussion |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Discusses neurotization as an alternative or adjunct therapy for NK. |

Discussion-based, no clinical trials. |

N/A |

4.1. Possibility of Corneal Angiogenesis

The cornea is naturally an avascular tissue, and maintaining this status is essential for visual function. Insulin is known as an anabolic factor with an essential role in cellular metabolism and, in certain pathological contexts, has been associated with the regulation of the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a cytokine essential in neovascularization processes [

19]. In diabetic patients, hyperinsulinemia has been correlated with increased levels of VEGF, thus contributing to proliferative diabetic retinopathy [

20]. This observation raises the question of whether prolonged use of insulin at the corneal level could indirectly stimulate angiogenesis, thus affecting corneal transparency. However, in the clinical studies analyzed, no such effects were reported. It should be noted, however, that the maximum duration of patient monitoring was approximately 8 weeks, which does not allow a sufficient assessment of the risk of neovascularization in the long term. Therefore, prospective studies with extensive monitoring are needed to determine whether topical insulin can have an angiogenic effect in the cornea or whether it remains safe for chronic use [

16,

17].

4.2. Possibility of Corneal Fibrosis

Another aspect that requires further investigation is the potential risk of stromal fibrosis. Insulin plays a fundamental role in cellular proliferation and migration and interacts with key modulators such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), both of which are deeply involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and fibrogenesis [

8,

21]. If topical insulin excessively stimulates the activity of corneal fibroblasts, it could result in irregular collagen deposition, compromising corneal transparency and reducing visual acuity. Although no direct clinical evidence currently supports this hypothesis, the absence of detailed histological assessments in current studies restricts our understanding of insulin’s effects on the stromal layer. Therefore, future investigations should include advanced histological and imaging techniques such as in vivo confocal microscopy and anterior segment OCT to monitor stromal remodeling after prolonged insulin use

[16].

4.3. Limitations of the Current Studies

Although current data support the efficacy of topical insulin in promoting corneal epithelial regeneration, it is important to acknowledge several methodological limitations of the reviewed studies. The maximum post-treatment follow-up reported was 8 weeks, as seen in studies such as those by

Khilji et al. (2023) [15] and Mancini et al. (2024) [14], which is insufficient to evaluate potential long-term outcomes. Most clinical studies included relatively small cohorts, typically ranging from 8 to 21 patients, which reduces the statistical power and generalizability of findings [

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, much of the current evidence is derived from observational and retrospective analyses, with a notable lack of randomized controlled trials to validate the efficacy and safety of insulin therapy for neurotrophic keratopathy [

16,

22]. In addition, considerable heterogeneity exists in insulin dosing regimens (ranging from 1 IU/mL to 100 IU/mL), frequency of administration, and treatment duration, making it challenging to establish a standardized therapeutic protocol

[13,14].

4.4. Directions for Future Research

To strengthen the position of topical insulin as a safe and effective therapy for NK, future studies should include randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with larger patient samples to validate the efficacy and safety of the therapy

[16,22]. Extended follow-up (>6 months – 1 year) is also necessary to detect possible long-term adverse effects, including the risk of neovascularization or fibrosis

[13,16]. Histological and imaging studies are recommended to evaluate the effects of insulin on corneal stromal architecture [

14]. Additionally, comparison with standard therapies—such as nerve growth factor (NGF), autologous serum, or corneal neurotization—should be pursued to identify the specific advantages and limitations of each therapeutic approach [

12,

13].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, topical insulin represents an innovative and affordable therapeutic option for neurotrophic keratopathy, offering a cure rate between 75% and 90%, according to available studies [

11,

13,

15]. However, the safety of long-term use remains uncertain, and potential effects on angiogenesis and fibrogenesis need to be explored further [

19]. Until these findings are confirmed through randomized controlled trials, topical insulin should be applied in clinical practice with caution and close patient monitoring to ensure maximum therapeutic benefit and minimize risk [

14].

Author Contributions

paper conceptualization R.S, M.A.M and S. I, methodology E. U and S.O, resources M.B and N.A, review and editing, A.G.O.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the 104 manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

BCVA-best corrected visual acuity

CIPA-congenital insensitiv-ity to pain

IGF-insulin growth factor

NGF-nerve growth factor

NK-neurotrophic keratitis

OCT- optical coherence tomography

PDGF platelet-derived growth factor

RCTs -randomized clinical trials

TGF-β transforming growth factor-beta

VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- Müller, L. J., Marfurt, C. F., Kruse, F., & Tervo, T. M. (2003). Corneal nerves: Structure, contents and function. Experimental Eye Research, 76(5), 521–542. [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, M., & Lambiase, A. (2014). Diagnosis and management of neurotrophic keratitis. Clinical Ophthalmology, 8, 571–579. [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, M. S. (2018). Anatomy of cornea and ocular surface. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 66(2), 190–194. [CrossRef]

- DelMonte, D. W., & Kim, T. (2011). Anatomy and physiology of the cornea. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery, 37(3), 588–598. [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S., Lambiase, A., Rama, P., Filipo, R., & Aloe, L. (2000). Topical treatment with nerve growth factor for neurotrophic keratitis. Ophthalmology, 107(7), 1347–1352. [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, C., Acosta, M. C., & Gallar, J. (2004). Neural basis of sensation in intact and injured corneas. Experimental Eye Research, 78(3), 513–525. [CrossRef]

- MacIver, M. B., & Tanelian, D. L. (1993). Cooling-sensitive neurons in the trigeminal ganglion of the rat. Journal of Physiology, 465, 561–578. [CrossRef]

- Zagon, I. S., Klocek, M. S., Sassani, J. W., & McLaughlin, P. J. (2007). Use of topical insulin to normalize corneal epithelial healing in diabetes mellitus. Archives of Ophthalmology, 125(8), 1082–1088. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J. D., Slusser, T. G., Turner-Henson, A., Singh, K. P., Atchison, J. A., & Pillion, D. J. (1994). Toxicity of insulin administered chronically to human eye in vivo. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology, 10(1), 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Feroze, K. B., & Patel, B. C. (2023). Neurotrophic keratitis. În StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Soares, M. G.; et al. (2022). Topical insulin for refractory neurotrophic keratitis: A retrospective clinical study. Ocular Surface Journal, 20(3), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Giannaccare, G.; et al. (2024). Combined use of therapeutic Hyper-CL soft contact lens and insulin eye drops for recalcitrant neurotrophic keratopathy. Eye & Contact Lens, 50(2), 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Eleiwa, T. K.; et al. (2024). Insulin eye drops for post-vitrectomy neurotrophic keratopathy in diabetic patients: A clinical study. Journal of Diabetes & Eye Research, 9(1), 12-19. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; et al. (2024). Topical insulin used alone or in combination with therapeutic contact lenses in refractory neurotrophic keratopathy. Clinical Ophthalmology, 18, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Khilji, I. A.; et al. (2023). Insulin eye drops for post-herpetic neurotrophic keratopathy: A case report. Journal of Ophthalmic Case Reports, 4(1), 31–34.

- Wouters, R.; et al. (2024). A systematic review of topical insulin for corneal epithelial defects: Efficacy and safety. International Ophthalmology Reports, 41(1), 12–25.

- Krolo, I.; et al. (2024). Insulin and ocular surface regeneration: New perspectives. Clinical Ophthalmology Insights, 29(2), 110–117.

- Fu, Y., & Zeppieri, M. (2024). Neurotrophic keratopathy: Emerging treatments. Ocular Therapy Review, 18(2), 99–106.

- Escudero, C.; et al. (2017). VEGF and insulin: A crucial angiogenic axis in chronic disease. Endocrine Reviews, 38(4), 333–370. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. A.; et al. (2020). Hyperinsulinemia-induced angiogenesis in diabetic retinopathy: Role of VEGF signaling. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 165, 108153. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, J., & Khabbaz, F. (2019). Insulin-like growth factor 1 and keratinocyte growth factor enhance keratinocyte migration and viability: Implications for wound healing. Frontiers in Medicine, 6, 151. [CrossRef]

- Moin, M.; et al. (2024). Topical insulin for corneal healing: Current evidence and future directions. International Journal of Ophthalmic Research, 12(2), 85–92.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).