1. Introduction

Adaptive control methods are still in the mainstream of research in the control of non-linear objects [

1,

2]. This is due to the fact that control should take into account variable operating conditions. One approach that takes into account variable operating conditions and compensates for the non-linearity of the control object is feedback linearisation [

3]. It is based on a model of the dynamics of the controlled object. Therefore, the quality of control obtained in this way strongly depends on the quality of the model, which is affected by the accuracy of identification of its parameters [

4,

5,

6]. It is reduced by the disturbances acting on the object, which can be divided into those that result from modelling inaccuracies and those that are the result of varying operating conditions. In the context of mobile wheeled robots, this can be a change in the mass carried or a change in the resistance to motion of wheel-surface pairs. It therefore becomes crucial to introduce a mechanism into the structure of the control algorithm that allows real-time adjustment of the model parameters. This is done by gradient methods, based on the control error or its function [

7,

8,

9]. This approach integrates adaptive control with optimisation problems [

10,

11]. Therefore, modern control algorithms make extensive use of artificial intelligence methods, which are based on the search for the minimum function of the model parameters. This opens up the possibility of using models known from machine learning methods, including hybrid algorithms that integrate data-driven approaches with knowledge of the controlled object [

12].

In 2023, the IEEE Control Systems Society published a report [

13], In 2023, the IEEE Control Systems Society published a report [1] that outlines how control systems will evolve by 2030. Systems will respond to increasing levels of automation across sectors. The report identifies five key methodologies emerging in control systems. One of these is data-driven modelling and control, which can be understood as the integration of machine learning and control systems. A particular expression of this integration is the combination of data-driven models with physics-based models in control algorithms, e.g. in adaptive control. The aforementioned report and the authors of many papers, e.g. [

14,

15] propose the use of hybrid modelling methods in control which are a combination of data-based and physics-based models. The paper [

14] provides an overview of hybrid models used in smart manufacturing. There, a physical model was compared with a data-based model and the benefits of hybrid models were pointed out. An analogous review was included in the paper [

16], where 81 articles on the application of models integrating knowledge (physics of the controlled object) and data were selected. As before, reference was made to manufacturing issues. The article [

16] provides a comprehensive overview of predictive models used in different industrial sectors. It classifies models based on the level of knowledge used to construct them: full knowledge models, zero knowledge models and partial knowledge models. The paper [

15] discusses the development and application of hybrid machine learning methods supported by physics models in the context of cyber-physical systems. The authors emphasise that traditional physics-based and data-only modelling approaches have their limitations. Their combination offers new possibilities for mapping complex physical objects.

It was mentioned earlier that adaptive control algorithms include a real-time parameter estimation mechanism. This process can be understood as an optimisation problem, which consists of selecting the values of the parameters of the mathematical model in such a way as to minimise the control error or its functions. Hence, genetic algorithms, which the literature refers to as nature-inspired approximation optimisation algorithms [

17] can be used in the parameter estimation problem. Reviews on genetic algorithms. [

18,

19,

20] and in particular the article [

21] state that genetic algorithms belong to the group of metaheuristic algorithms. They are strategies for searching the solution space, typically of an optimisation problem, to obtain an approximate solution.

In this paper, a successful attempt is made to apply a genetic algorithm that is based on the theory of natural selection (GABONST) to the parameter estimation of a mathematical model of a wheeled robot. This algorithm was proposed in the article [

22] and is an extension of the classical genetic algorithm by introducing Darwin’s idea of natural selection. Moreover, the proposed algorithm has been extended with knowledge-based mechanisms that address, among other things, the value of the tracking error of the wheeled robot. Another type of knowledge used is that the model parameters are interval constant. In this way, a hybrid algorithm was obtained that combines the features of a genetic algorithm and process knowledge.

In summary, there are three areas of contribution of this paper:

Synthesis of an adaptive control law that uses a hybrid genetic algorithm to estimate the parameters of a mathematical model of a wheeled robot.

The use of the GABONST algorithm as a hybrid model based on process knowledge.

Numerical verification of the proposed adaptive control algorithm for a mobile wheeled robot under varying operating conditions.

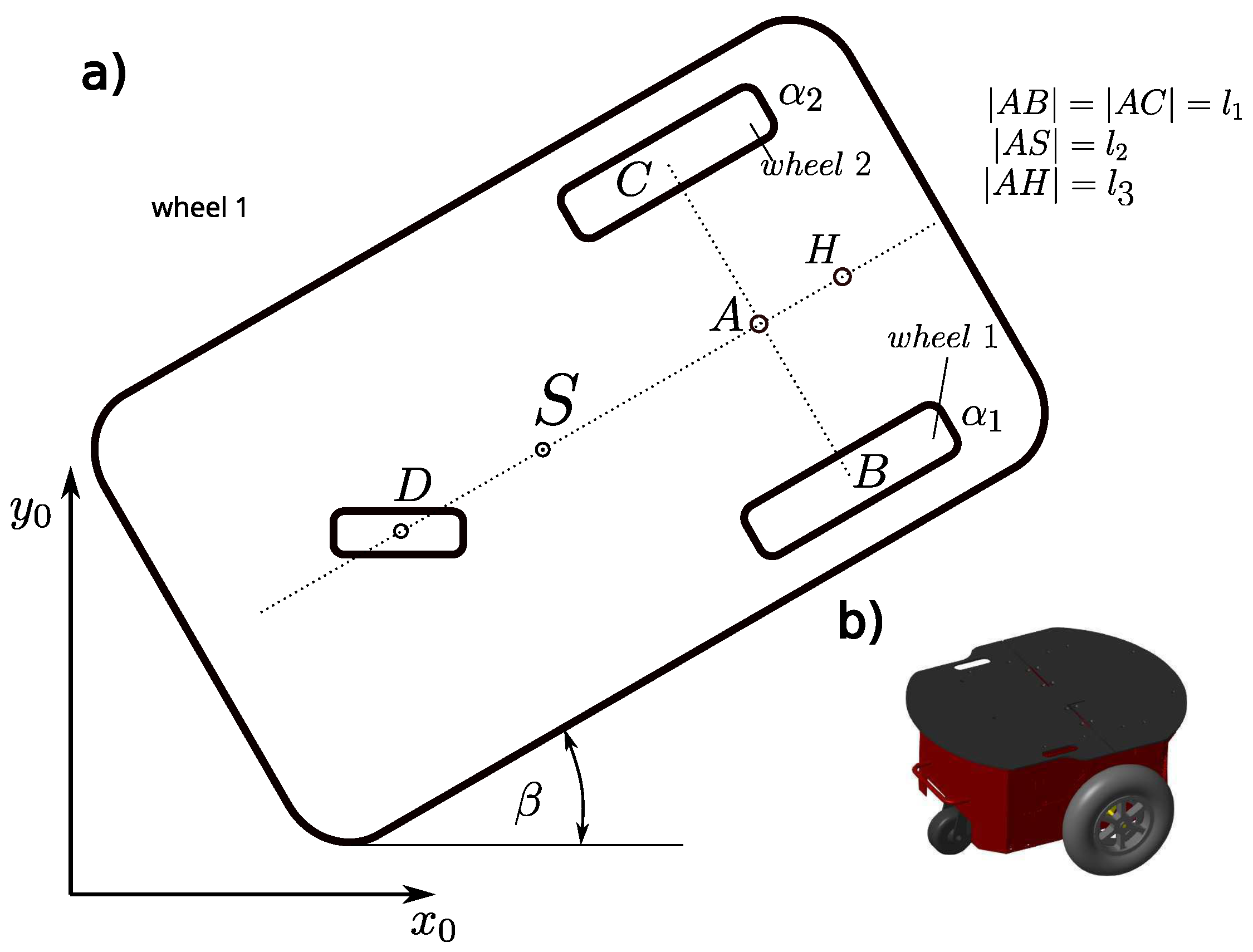

The rest of the article, in

Section 2, presents a description of the kinematics and dynamics of a mobile wheeled robot.

Section 3 presents the synthesis of optimal adaptive control of the robot. The control synthesis was carried out using a mathematical model of the control object.

Section 4 presents the genetic algorithm used in the control to optimize the model parameters. Selection, crossover and mutation procedures are presented in detail, as well as how to incorporate physical knowledge of the robot into the genetic algorithm procedures.

Section 5 presents and discusses the results of a numerical test, confirming the correctness of the developed theoretical solutions Conclusions on the results of the work are gathered in

Section 6.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version).

3. Synthesis of Adaptive Control in a Tracking Task

An adaptive control algorithm is designed in such a way that it can modify its properties under varying operating conditions. In the case described here, the adaptive algorithm is used to control a mobile robot in a tracking task. The task of following a desired trajectory for mobile robots can be understood as determining such a solution for the initial conditions

, that converges to a manifold defined as:

, where

is the vector of desired coordinates,

is the vector of desired angular velocity resulting from the solution of the inverse kinematics problem [

25].

The equation describing the dynamics of the mobile robot has the form (

7). The tracking error in relation to angle of rotation and angular velocity was defined in the following form

In addition, a filtered tracking error was defined as

where

is a diagonal design matrix with positive elements

. By differentiating the generalised tracking error (

11), the expression was obtained

Multiplying both sides of Equation (

12) by the inertia matrix

we obtain

By substituting Equation (

7) into the above equation, the following was obtained

and after transformation, the result is

Multiplying both sides of relation (

11) by matrix

yields

Hence it is easy to determine the expression

Taking this into account, relation (

15) can be written as a function of the filtered tracking error

with non-linear function

whereby the vector

contains the signals on which

depends. By defining the auxiliary signals

the form of the function

can be simplified to the form

Note that the function

can be written in linear form with respect to the model parameters

, i.e.

The matrix

contains the functions resulting from the description of the robot’s dynamics and has the form:

where

are the elements of vector

,

are the elements of vector

,

are the elements of vector

.

Determining the value of the function

requires knowledge of the parameter values. This is difficult to implement, especially in the case of varying operating conditions. Hence, adaptive control uses an estimate of the function

i.e.

which is given as:

where

is an estimate of the model parameter vector. This approach requires an extension of the control algorithm to include the parameter adaptation law, which is usually implemented as:

It should be noted that this approach requires the assumption that the

parameters are constant over the time intervals.

Usually, the law of parameter adaptation is applied in continuous time, but in the context of using adaptation techniques operating in discrete time, the law of parameter adaptation given in the form (

25) can be written in discrete form [

27]:

where

h is a discrete step. In the context of the application of optimisation methods, the Equation (

26) is more favourably written in the form of

On this basis, the function to be minimised was defined in quadratic form

where

is a design matrix and

. If optimisation methods, like genetic algorithms, are designed to search for a maximum, the function

J can be transformed to the form

where

is a design constant.

We want to ensure the stability of the closed-loop system without changing the designed compensating control signal

given by Equation (

24). This means that the control law

must be designed in such a way that the filtered tracking error

is bounded i.e.

where

is a constant value. For this purpose, the control signal was enriched with a supervising control

, generated by an additional supervisory term, which is different from zero when the tracking error reaches the limits of the following set:

In addition, a component responsible for stabilising tracking errors in the form of proportional-differential control expressed as

is included. Finally, to ensure the stability of the closed system, the control law will take the form

where

is a matrix with elements

, which take the value 1 when

and 0 otherwise. By substituting the Equation (

32) into the Equation (

18) the result was obtained:

By defining a positive definite function

, differentiating it and considering the worst-case when tracking errors are large and supervisory control is active, i.e.

, the result is:

After transformations, the following form was obtained:

Since

is a skew-symmetric matrix, the derivative of the scalar function (

35) takes the form

If we select the supervisory control signal in the following form

and assuming

, we obtain:

The derivative of the Lyapunov function is negatively definite, so the closed system (18) is stable, for tracking errors such that . When then the supervisory control is inactive and the derivative of the Lyapunov function has the form . This proves that the filtered tracking error is bounded. The elements of the vector are generated by the genetic algorithm, which is formulated in such a way that it searches for solutions in a limited region of the parameter space. Therefore, the estimate of the parameter vector is by assumption bounded. Thus, no proof of this fact is required in the stability analysis.

There is a step function

in the control law (

32), which activates the supervisory control signal

at the boundary

. To eliminate the high switching frequency of the actuator, an approximation of

in the region defined by

is introduced, according to the relation

A general diagram of the control system is shown graphically in

Figure 2.

Finally, the adaptive control of the trailing motion of a wheeled mobile robot is in the form of the Equation (

32) and is realised based on the estimation of the non-linear function

and the parameter adaptation law (

26), which is implemented as an optimisation problem of a discrete function given in the form (

29). In this case, the optimisation algorithm is implemented based on genetic algorithms, which are described in the next section.

4. Classical Genetic Algorithm

A genetic algorithm is a non-linear, discrete and stochastic process, rather than a mathematically controlled algorithm, which was introduced by John Holland of the University of Michigan in 1975 [

28]. Since then, this approach has found a permanent place in machine learning methods. Its task is understood as the search for the minimum or maximum of a function in a specified solution space [

28,

29]. The practice has been introduced that genetic algorithms search for the maximum of the objective function. Furthermore, the paper [

28] states that, depending on the particular problem, it may be sufficient to determine a local maximum or a solution that is close to the local or global maximum. Hence the term that the genetic algorithm is an approximation algorithm, as it returns a solution for which the value of the objective function is as high as possible. The search for the maximum of the objective function, which is called the fitness function, is implemented based on the cyclic execution of the selection, crossover and mutation mechanism, which is preceded by the initialisation of the population. From this perspective, the genetic algorithm can be regarded as iterative.

The initialisation of the algorithm, i.e. the generation of the first population in the specified range, appears to have a significant impact on the success of the algorithm. This was confirmed in the paper [

19], where the selection of the population was identified as the

main challenge determining the quality of the solutions. It is not only its proper selection that is at the heart of initialisation. The choice of the type of chromosome representation is also made at this stage. The papers [

20,

21] note that the common coding scheme is binary coding, but octal, hexadecimal or decimal coding are also used. The latter was used in this work.

4.1. Selection

Selection reproduces the phenomenon of natural selection, the emergence of a group of the best individuals from a given population, i.e. those for which the values of the fitness function are greatest. The selection operation determines which of the genes in the current generation can constitute the parental group of the next generation. Such an operation is intended to ensure that the optimal solution is approached. Several selection methods are described in the paper [

30], including roulette wheel, linear ranked selection or tournament selection.

4.2. Crossover

Individuals that pass the selection process can generate new offspring. Through crossover operators, new offspring are created on the basis of the two parents [

31]. Through crossover, using biological comparison, new genetic material is introduced, thereby maintaining genetic diversity [

32]. In the context of an optimisation task, the crossover operator prevents the genetic algorithm from converging too quickly and allows a larger region of the solution space to be searched. Many crossover techniques can be found in the literature that differ in the way genes are exchanged between parents. An overview of these methods can be found in the paper [

33].

In the work described in this article, the Simulated Binary Crossover (SBX) method is used for crossover. Its operation is based on binary individuals (encoded in decimal), which can be written as vectors

and

where

t encodes the iteration number of the genetic algorithm. In the SBX method, offspring generation starts with the determination of the coefficient

, który kontroluje odległość między rodzicami a potomstwem. which controls the distance between parents and offspring. Its value is calculated according to the relation:

where

is the random crossover coefficient, and

is the parameter controlling its intensity. Based on the value of the

coefficient, the values of the offspring genes are determined:

Based on the relationship (

41) and taking into account the crossover interval (determines which elements of the vector representing the individual will be changed) and the mutation probability, the SBX algorithm can be presented in pseudocode form:

|

Algorithm 1 Simulated Binary Crossover (SBX) |

- 1:

function SBX() ▹ where X,Y is a pair of parents, is the intensity parameter, is the crossover interval, is the crossover probability - 2:

if then

- 3:

for to n do

- 4:

if then

- 5:

choose randomly

- 6:

if then

- 7:

- 8:

else

- 9:

- 10:

end if

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

else

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

end if

- 17:

end for

- 18:

else

- 19:

- 20:

- 21:

end if

- 22:

end function |

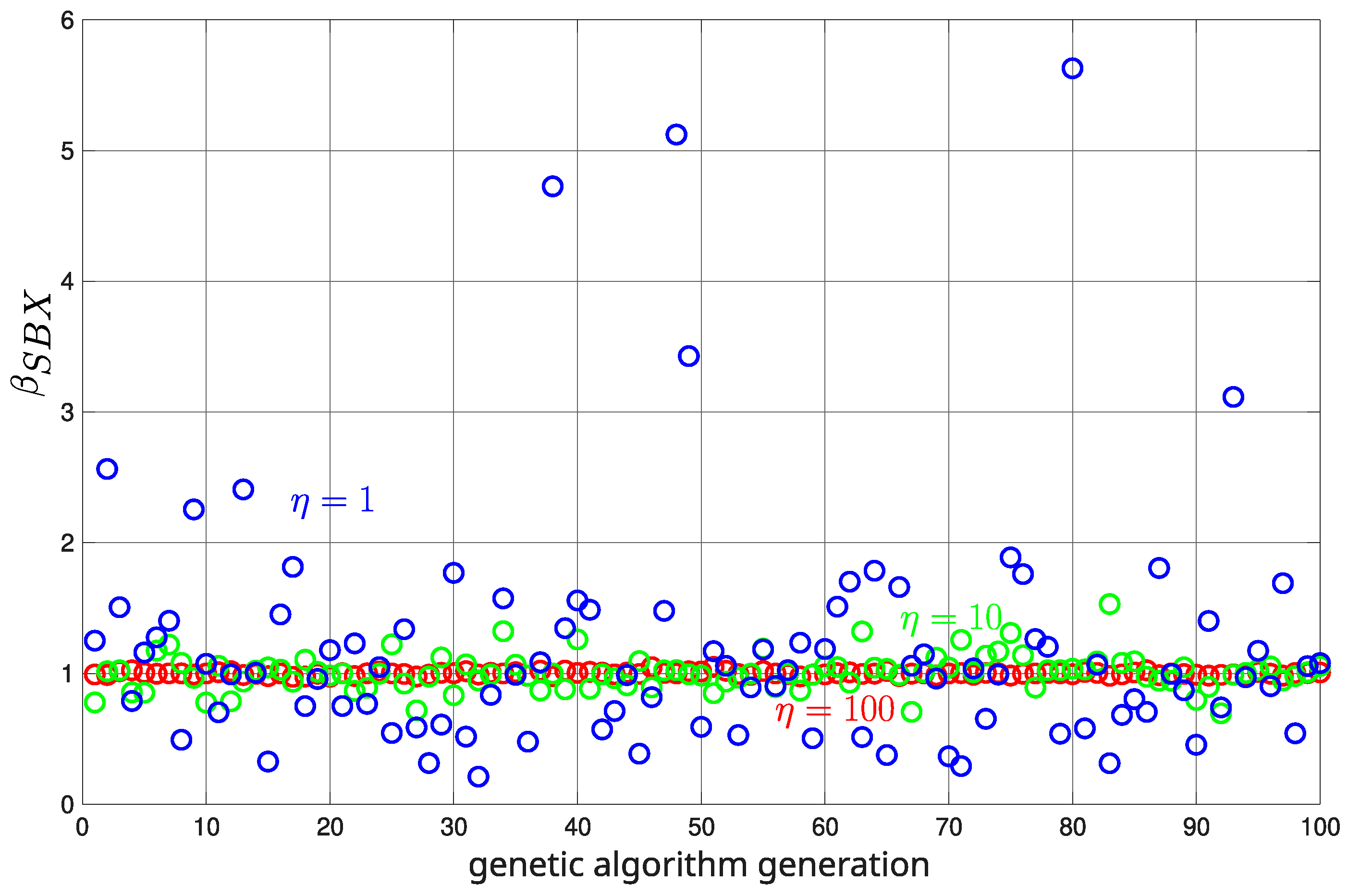

Figure 3 shows the values of the

coefficient for different values of the

parameter.

The values for are close to 1 which means that the offspring genes will be more similar to those of the parents. In the case of , the values of are more diverse, allowing the generation of more diverse offspring.

4.3. Mutation

The author of dissertation [

34] notes, that one of the limitations of genetic algorithms is premature convergence, which results in a narrowing of the evolutionary process to a local optimum. The author of paper [

17] sees the cause of this phenomenon in the lack of genetic diversity in the population, which is due to the fact that the crossover operator does not introduce new genes into the population. So this is a problem that needs to be solved. To do this, mutation operators are used, which by changing the values stored in the vectors representing the individuals, new areas of the considered search space can be explored. [

34]. A number of mutation techniques can be found in the literature, which differ in the way they work. A list of these can be found in the paper [

35]. A large number of citations relating to mutations of individuals encoded by real numbers can be found in the paper [

20].

This work uses the Gaussian mutation method, which is one of the most commonly used mutation operators in genetic algorithms with coding by real numbers. It consists in adding a random number generated from a normal distribution to the value of the gene, which allows modifying the values of the elements of the vector

. These are modified according to the equation:

where

is the value of the gene

i after mutation and

denotes a random number from a normal distribution with mean

and variance

which can vary depending on the iteration of the genetic algorithm.

The pseudocode of the Gaussian mutation method, which takes into account the mutation probability

and the parameter

, can be presented in the form:

|

Algorithm 2 Gaussian Mutation |

- 1:

function GaussianMutation() ▹ where X is a chromosome, is the mutation probability, is the standard deviation - 2:

for to n do

- 3:

choose randomly

- 4:

if then

- 5:

- 6:

end if

- 7:

end for

- 8:

end function |

4.4. Algorithm GABONST

The paper published in 2020 [

22] proposes modifications to the classical genetic algorithm by adding mechanisms to incorporate Darwin’s postulates of natural selection. The authors postulate that the genetic algorithm should incorporate a mechanism of natural selection that makes the best individuals likely to survive. These chances for weaker individuals are less, but possible in two cases: 1) crossover with an individual with a high ability to survive in the environment, which can lead to the transmission of favourable genetic features; 2) mutation, which can lead to favourable genetic features. If the individual resulting from these two cases does not meet the requirements of the environment, it may become extinct over time.

This bilogical description of the natural selection method was converted by the authors into the GABONST algorithm, available in the paper [

22]. A modified version of it, which was used in this work, is presented below:

Generate an initial population consisting of n individuals that are stored as a vector. Set .

Calculate the value of the fitness function for each individual in the population .

Return the smallest value of the fitness function for percent of the best individuals and store it in the variable .

-

For compare the value of the fitness function with the value of :

- (a)

If : mutate an individual using the Gaussian method (with a variance and a mutation probability ); record in the population ;

- (b)

-

If :

Select a random individual from the set of best individuals and write to the variable .

Perform a crossover of an individual with individual using the SBX method (with parameters for all elements of the individual’s coding vector) and save the single offspring to the variable .

If then save the individual in the population

-

If :

Perform a mutation of an individual using the Gaussian method (with a variance and a mutation probability ) and write to the variable .

If then save the individual in the population .

If then generate a new individual and save it in the population .

Increase by 1 and return to step 2.

The above genetic algorithm taking into account the mechanism of natural selection, in the context of this work, is used to adapt the parameters of the estimation of the function

in the control law (

32). Therefore, there is no specific stopping criterion. In this application, the GABONST algorithm is executed

times within one discrete step. After its completion, the individual whose fitness function is the largest is determined. This is the individual that encodes the value of the parameter estimate

.

4.5. Knowledge in the Genetic Algorithm

Knowledge of the fitness function optimised by the genetic algorithm can be used to control the optimisation process. In the context of the use of the GABONST algorithm in adaptive control, this could be the use of information about the filtered tracking error , the assumption of equal movement resistance at each driving wheel or the assumption of the variability of the model parameters, which are interval constant. In view of the above statement, several assumptions can be made regarding the assumed parameters of the GABONST algorithm:

The estimates of the values of the parameters related to resistance to movement in the initial population should be the same and within the assumed range.

The structure of the GABONST algorithm reflects the assumption of interval constancy of parameters.

The percentage of individuals, i.e. determining how they are processed in the GABONST algorithm, should be dependent on the filtered tracking error .

The mutation intensity for the case when should increase as the filtered tracking error increases.

The influence of an individual on the outcome of a crossover with an individual should be reduced as the filtered tracking error increases.

In the case when , the intensity of mutation that can lead to the inclusion of an individual in a new population should increase as the filtered tracking error increases.

The above points, which are written down as suggestions, arise from knowledge of the controlled object. The first point relates to the assumption of an interval of variation in movement resistance, which can be derived from knowledge of the surfaces on which the robot moves. The assumption of equality of movement resistance is related to the assumption that both wheels are on the same surface when the robot starts.

The second and third points refer to the assumption that the parameters of the robot model are constant intervals. This, in turn, means that for a given interval there is no need to adjust the parameters according to the idea of natural selection, but only a small mutation is necessary to fine-tune them. This approach will also reduce the noise associated with the operation of the genetic algorithm. Only if there is a change in the parameter values, which happens at the boundary of the interval, should a larger number of individuals undergo crossover and mutation, which in the GABONST algorithm is done in steps related to natural selection. Whether the robot’s parameters are within the new interval can be determined by the value of the filtered tracking error , as discussed in point 3.

Points 4-6 deal with mutation and crossover intensity. In the case when , an individual can be assumed not to survive in a given environment. For the application under consideration, the intensity of mutation and crossover should increase as the filtered tracking error increases, on which the parameters of the SBX method (crossover) and the Gaussian method (mutation) can be made dependent. This can be realised based on the error norm of .

5. Numerical Test

This section describes the numerical test that was performed to verify the correct operation of the proposed adaptive control, in which the knowledge-based GABONST algorithm was used to adapt the parameters of the mathematical model of the wheeled robot. The test assumes that the desired trajectory of the robot point

H is a fragment of the Lame curve of the form

where

,

are the design constants. From the Equations (

5) and (

6) were determined:

Using the Matlab/Simulink package, a coordinate vector

for a wheeled robot moving along a section of the Lame curve was determined based on the system of Equations (

44). The length of the path is determined by the numerical test time (

) and the profile of velocity

which assumed that the acceleration and deceleration phases of the robot occurred in the 3rd and 18th second, respectively, at the maximum steady-state velocity

. The other parameters associated with the assumed kinematics equations are:

,

,

,

,

and

.

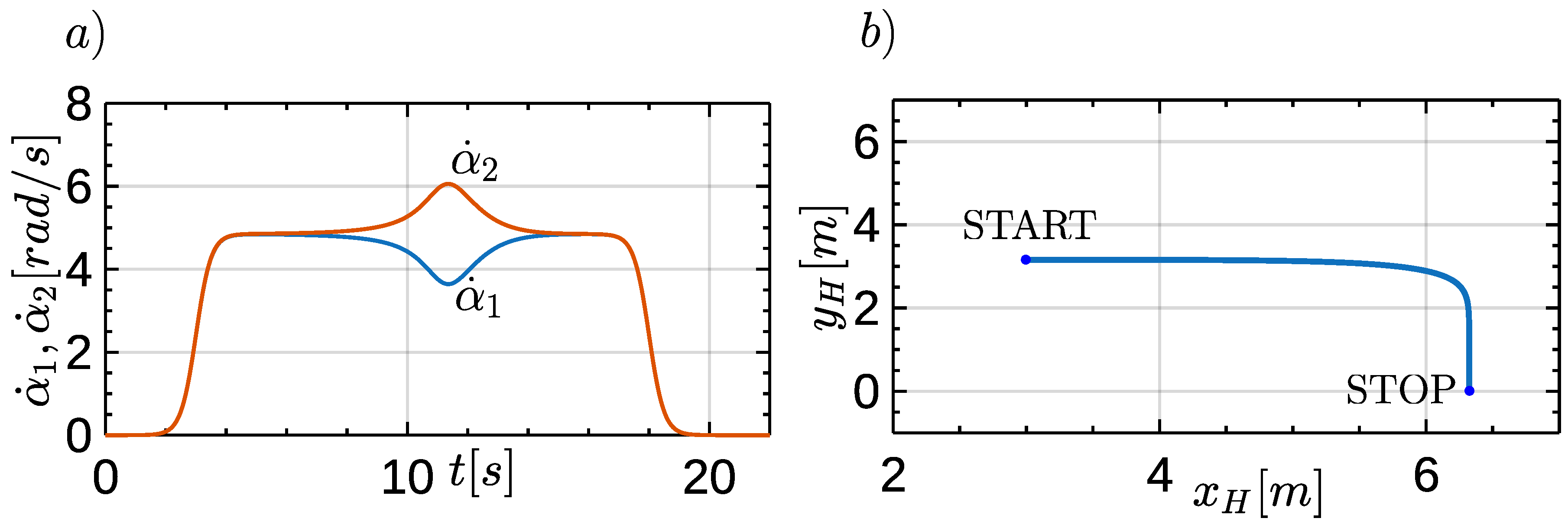

Figure 4a shows the speed course of the drive wheels, where the acceleration and braking phases are visible.

Figure 4b shows the trajectory of the wheeled robot in the reference system

. This is a fragment of the Lame curve, which is described by the equation (

43).

The presented trajectory of the robot and the obtained kinematic parameters of the driving wheels will be the basis for determining the filtered tracking error given by Equation (

11) in the tracking control task, for a wheeled robot described by the dynamic equation of motion (

7). The parameters of the robot were assumed as follows:

,

,

,

,

. The control law was assumed according to the Equation (

32) and for its implementation it was assumed that:

,

,

,

,

.

In the numerical test considered, the model parameters that are related to the resistance to motion, i.e. and , were adapted, while the others were assumed constant. For their adaptation, the GABONST algorithm was used, which in this work was enriched with object knowledge. As an initial population, 16 individuals were randomly generated, which are represented by the vectors , where is the value of the parameters related to movement resistance. The values of are randomly chosen from the range . Furthermore, due to the assumption that the wheels of the robot are on the same surface, it was assumed for the initial population that .

The objective function that the genetic algorithm maximised is given by the Equation (

29) with

. The genetic algorithm was implemented according to the procedure that is presented in

Section 4.4. In one discrete step of the control algorithm, which was

, three loops of the genetic algorithm were implemented. The value of

was 8. The other parameter values of the GABONST algorithm used in the numerical test were dependent on the knowledge of the object, as indicated in section 4.5. Their detailed values are summarised in

Table 1.

In order to force the GABONST algorithm to adapt the model parameters, it was assumed in the numerical test that the parameters related to the movement resistance would have different values in the time intervals. Therefore, it was assumed in the robot model that the parameters

and

would vary according to the relationship:

where

t is the simulation time.

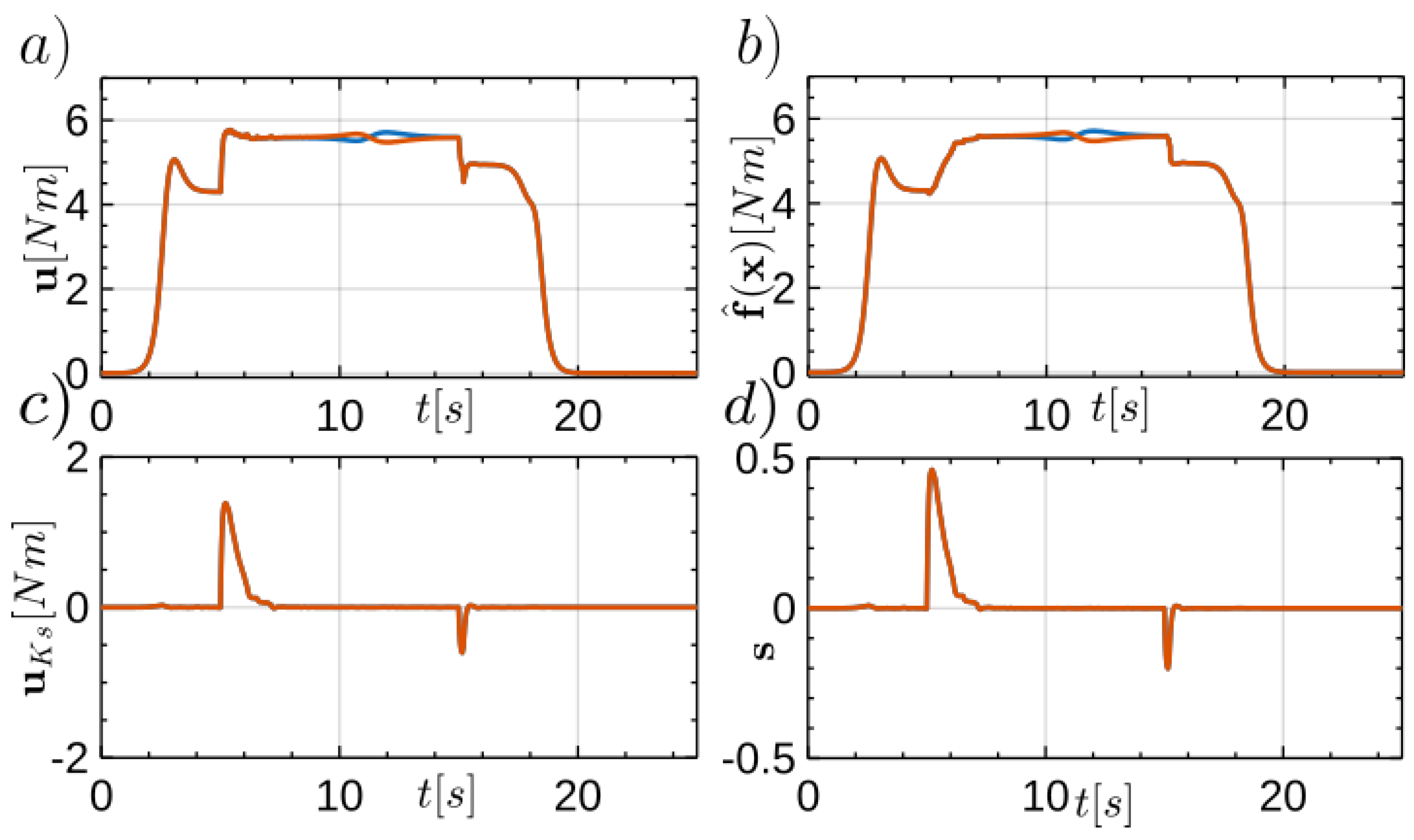

The control signals are presented in

Figure 5.

Figure 5a) shows the waveform of the overall control

consisting of the stabilising control PD, i.e.

, the adaptive control

and the supervisory controlo

. For the assumed parameter

the supervisory control term

did not activate because the condition

was satisfied. The system remained stable during the movement.

During the initial phase of the movement, the control

(rys.

Figure 5b), is immediately activated, as the initial values of the parameter evaluations are consistent with the values assumed in the robot dynamics model and the initial population of the GABONST algorithm was drawn near the nominal values of the parameters

and

. Only when the parameter values in the model are increased by 30 % (which happens at time

) is the PD control (

Figure 5c) activated. This is related to the higher values of the tracking errors

and

, and therefore also the filtered tracking error

(rys. 5d). This is due to the maladaptation of the values of the parameter estimates, which are represented by the individual with the maximum value of the fitness function after three loops of the GABONST algorithm in a given iteration step. As the adaptation progresses, the compensating control becomes more and more adequate to the changed dynamics of the object, while the PD control signal decreases. The quality of adaptation is also confirmed by the course of the filtered tracking error

, which remains close to zero after the increase due to the change in the value of the parameters

and

.

The above description is also valid for the situation occurring at time when the values of the parameters and change and reach 115 % of the nominal values. Then, analogously as before, the role of PD control temporarily increases and then decreases (in amplitude) as the adaptive control adapts to the new values of the changed parameters.

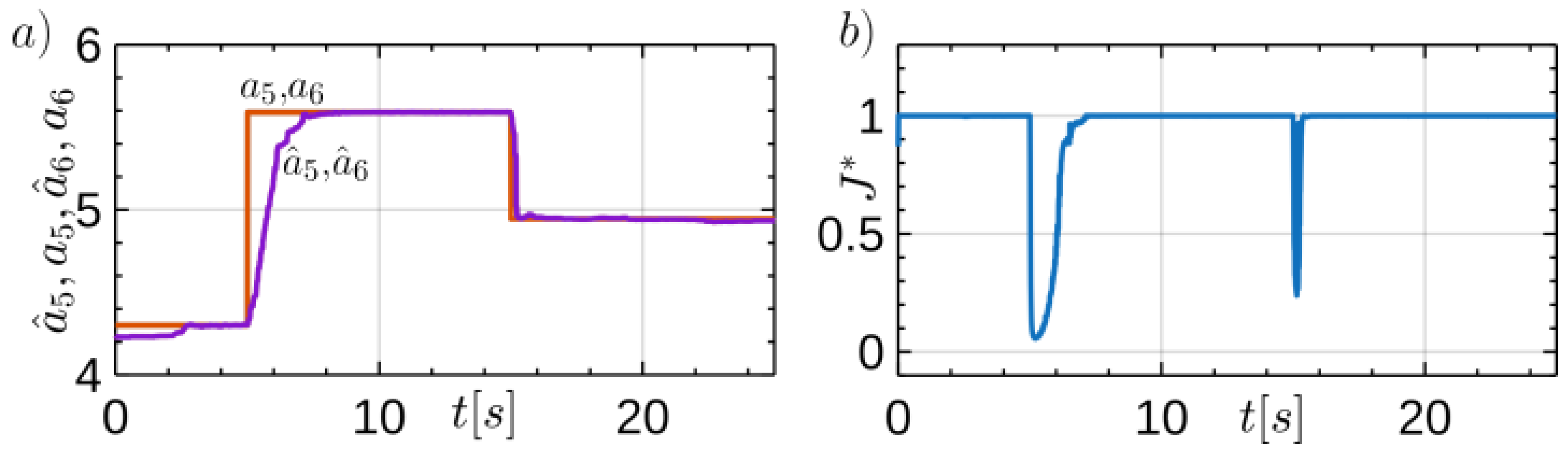

The

Figure 6a) shows the course of adaptation of the parameter estimates related to motion resistance. As mentioned earlier, the initial population was chosen so that no significant adaptation is required during the initial phase of the numerical test. This changes when for

there is a change in the value of the parameters

and

. Then, as shown in

Figure 6a), the values of the parameter estimates

and

adapt to the new values. This is related to the operation of the genetic algorithm, which seeks to maximise the fitness function (

Figure 6b). An analogous situation occurs when the parameters are changed for

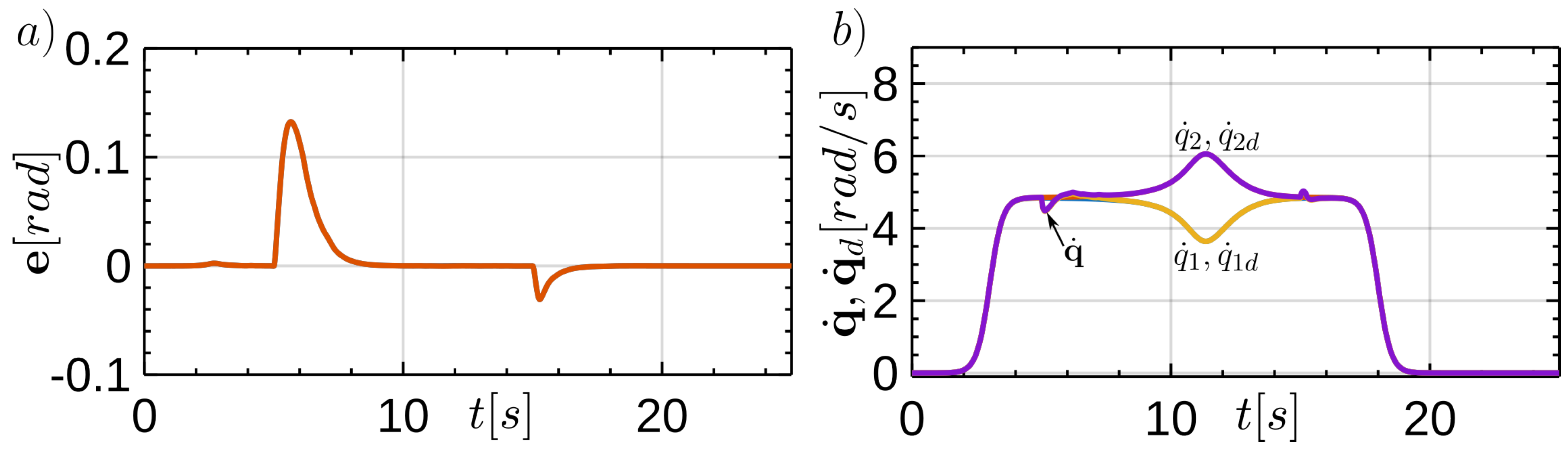

The above comments on the generalised tracking error

are confirmed by the waveform of the error

, which values remain small (

Figure 7a). Similar conclusions arise from the waveforms of the desired and obtained angular velocities of the robot wheels (

Figure 7b). These differ significantly only when there are disturbances, i.e. for

and

.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the synthesis of tracking control of a mobile wheeled robot was carried out. A genetic algorithm that takes into account the idea of natural selection was used to adapt the estimates of parameters required for the implementation of compensating control. The method provides an opportunity to take into account knowledge of the object’s operating conditions, which usually change interval-wise, for example, due to a change in the roadway surface, as studied in the article, or a change in the load being carried. In such a situation, an increase in the intensity of crossover and mutation is required, which is allowed by the algorithm used. This results in a rapid adjustment of the model parameter estimates to the new conditions. On the other hand, when the conditions of the robot do not change significantly, that is, the parameters of the robot do not undergo significant changes, the intensity of crossover and mutation in the algorithm is reduced so that there is no oscillation of parameter estimates.

The results of the simulation indicated the correctness of the assumptions made, in particular that the control system remains stable and the tracking errors are limited. Based on the values of tracking errors, the quality of the tracking task execution should be considered good. In addition, the adapted parameter estimates tend towards the values of the model parameters, and the adaptation algorithm shows sensitivity to parameter changes during the robot’s operation. Further work planned will be the study of the impact of selection, crossover and mutation algorithms on the quality of control with a particular focus on the impact of object knowledge on the parameters of these operations. The next stage of the research will be the verification of solutions using the real robot.