Submitted:

12 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Formulation and Framework

2.1. Problem Setting

2.2. Loss Function Construction

2.3. Architectural Variants

| Method | Core Idea | Target Problem | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla PINN | PDE residual in loss | General PDEs | Raissi et al. (2019) |

| XPINN | Domain decomposition | Multi-scale domains | Jagtap et al [21]. (2020) |

| fPINN | Fourier features | High-frequency solutions | Wang et al. (2021) |

| UQ-PINN | Probabilistic weights | Uncertainty quantification | Yang et al. (2021) |

| hp-PINN | Adaptive meshing and depth | Stiff problems | Lu et al. (2022) |

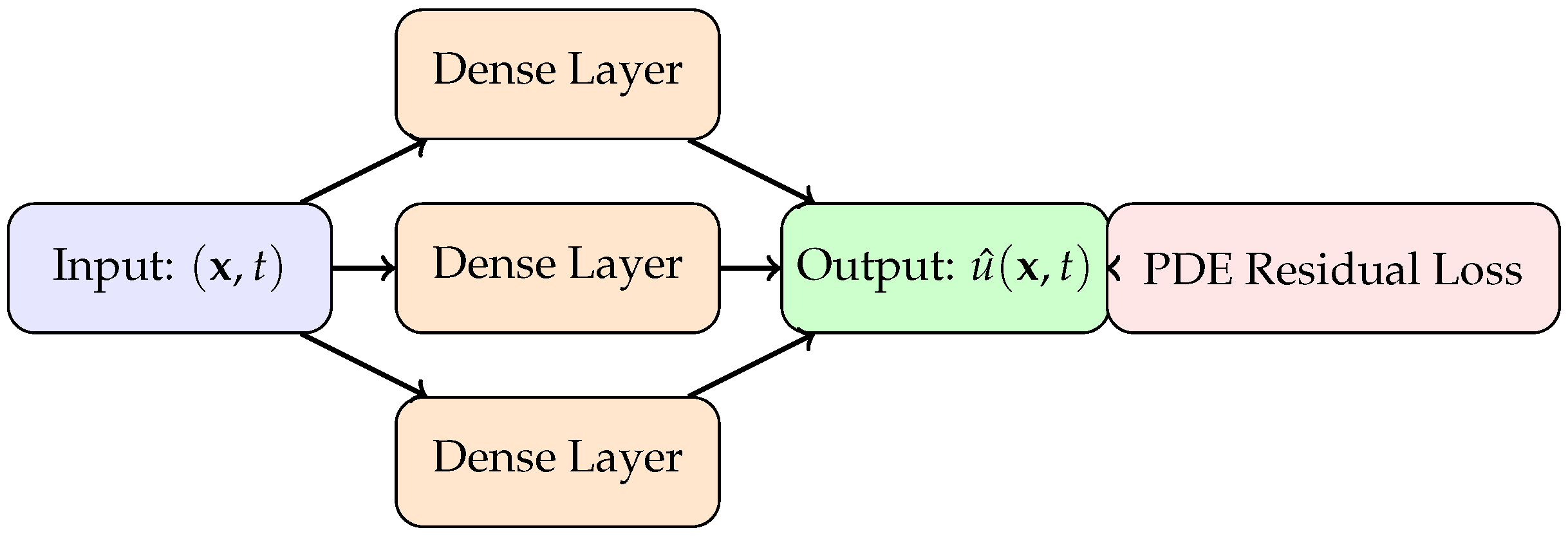

2.4. Neural Network Architecture

3. Training Strategies and Optimization Techniques

3.1. Optimization Challenges

3.2. Gradient Pathologies and Stiffness

3.3. Training Enhancements

3.4. Optimization Algorithms

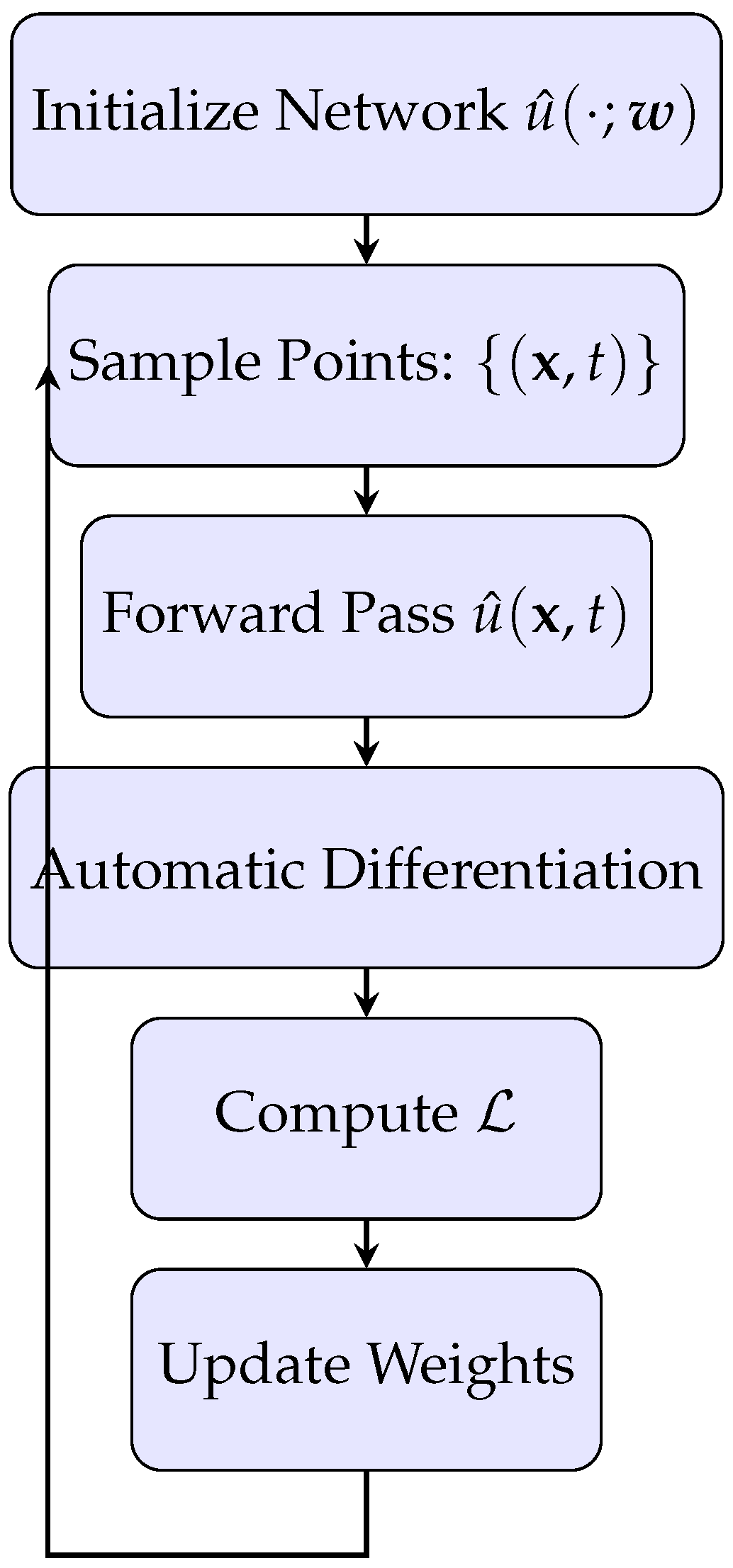

3.5. Training Pipeline Overview

4. Theoretical Foundations and Analysis

4.1. Universal Approximation and PDE Solutions

4.2. Error Decomposition and Convergence Guarantees

- Approximation error: Due to the finite capacity of the neural network.

- Optimization error: Due to incomplete minimization of the loss function.

- Generalization error: Due to the finite number of training points.

4.3. Generalization in Function Space

4.4. Comparison with Classical Numerical Methods

4.5. Limitations and Open Problems

- There is no universal guidance for choosing the collocation point distribution, network architecture, or loss weights that guarantee convergence for arbitrary PDEs [44].

- PINNs often struggle with sharp discontinuities and multi-scale features, where classical solvers are more robust due to explicit mesh refinement and adaptivity [45].

- The impact of network depth and width on approximation accuracy in the presence of stiff differential operators is not fully understood.

- It remains an open question how to formally characterize the solution manifold of complex PDE systems and how this geometry interacts with the inductive bias of neural networks.

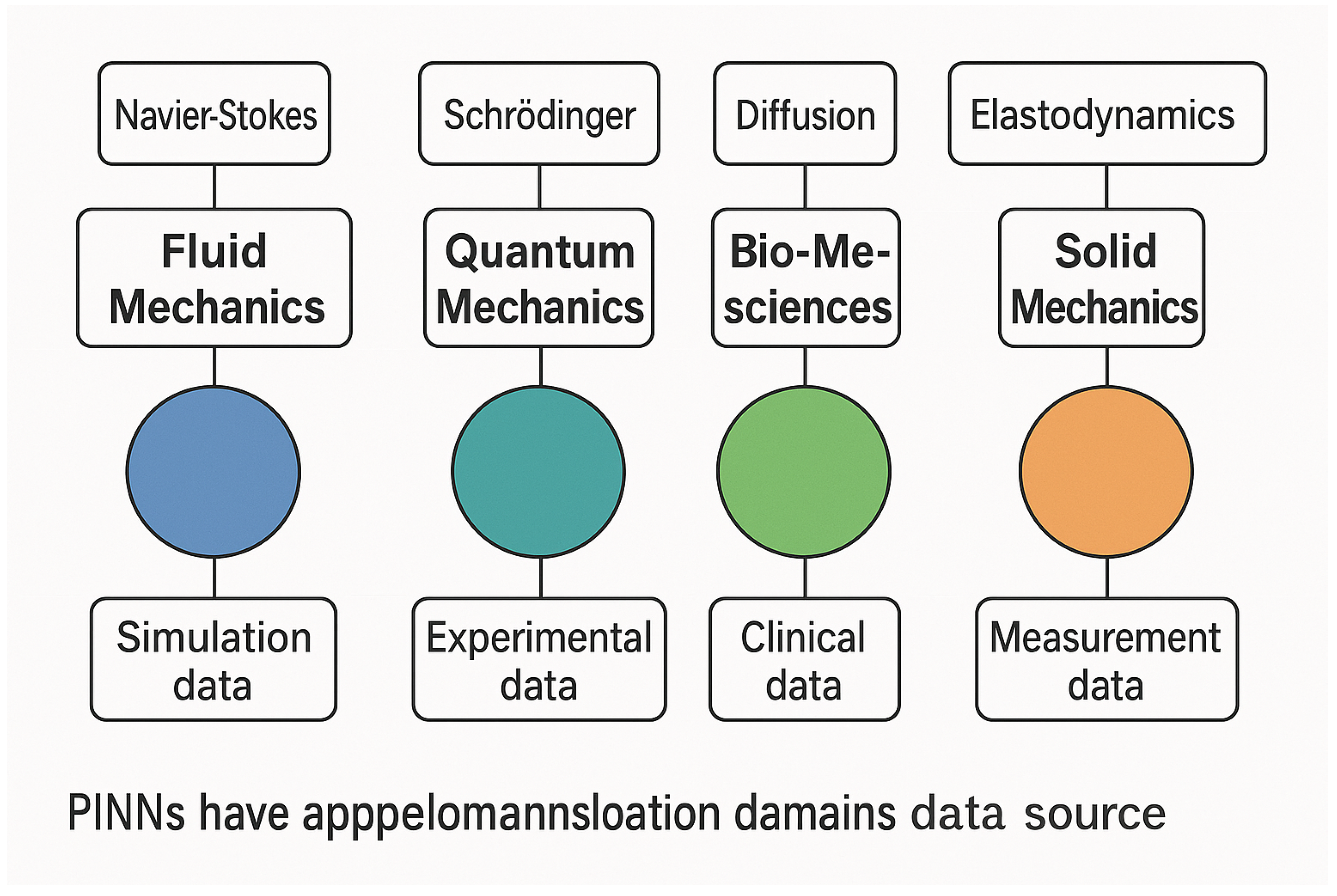

5. Applications Across Scientific and Engineering Domains

5.1. Fluid Mechanics and Navier–Stokes Solvers

5.2. Solid Mechanics and Material Modeling

5.3. Electromagnetics and Wave Propagation

5.4. Biomedical Applications and Physiology Modeling

5.5. Energy Systems and Geophysical Simulations

5.6. Summary of Application Landscape

6. Hybrid Architectures and Extensions of PINNs

6.1. XPINNs: Domain Decomposition for Parallelization

6.2. cPINNs: Conservative PINNs for Physical Consistency

6.3. hpPINNs: Multi-Resolution Refinement Strategies

6.4. DeepONets and Neural Operators

- The branch net encodes the input function f sampled at sensors .

- The trunk net encodes the target location x.

- The output is .

6.5. Variational, Probabilistic, and Multi-Modal Extensions

- Bayesian PINNs use variational inference or Hamiltonian Monte Carlo to estimate posterior distributions over the solution u or parameters , enabling uncertainty-aware predictions [72].

- Variational PINNs (VPINNs) reformulate the training objective as a variational minimization, inspired by finite element weak formulations:where are test functions in a Hilbert space.

- Multi-modal PINNs integrate diverse data modalities—such as pointwise measurements, images, and boundary sensor arrays—by encoding each modality into a shared latent space before applying PDE constraints. This is particularly powerful in biomedical imaging and remote sensing.

6.6. Summary and Design Taxonomy

7. Evaluation, Benchmarks, and Performance Metrics

7.1. Quantitative Metrics for PINN Evaluation

- Relative Error:where is the predicted solution and is the ground truth from analytical or high-fidelity numerical solvers.

- Pointwise Residual Error: Measures how well the predicted solution satisfies the governing PDE:where are collocation points and is the PDE operator.

- Boundary Error: Quantifies the deviation at boundaries:where g is the specified boundary condition [73].

- Conservation Loss: For problems with integral conservation laws (e.g., mass, energy), the global integral of the discrepancy is evaluated.

- Computation Time and Scalability: Total training time, GPU/CPU utilization, and memory footprint are critical performance measures, particularly for large-scale applications [74].

7.2. Common Benchmark Problems and Datasets

7.3. Ablation Studies and Model Diagnostics

- Activation Function Sensitivity: Comparing tanh, ReLU, GELU, sine activations for convergence behavior.

- Network Depth and Width: Impacts expressivity vs. trainability trade-offs.

- Gradient Pathologies: Monitoring gradient norms and Hessian spectra to detect vanishing/exploding gradients or stiffness [78].

- Loss Weighting Strategies: Empirical comparisons between fixed, dynamic, and adaptive loss weighting.

7.4. Reproducibility and Open-Source Benchmarks

- DeepXDE (Lu et al.): TensorFlow-based library for solving differential equations with PINNs and DeepONets.

- NeuralPDE.jl (SciML): A Julia-based framework emphasizing scientific machine learning with strong PDE support.

- PINNBench: A curated benchmark suite with standardized problem definitions, metrics, and logging.

- NSFnets, PhyCRNet: PyTorch-based specialized PINN variants for fluid dynamics and conservation laws.

7.5. Challenges in Evaluation and Future Needs

- Lack of Standard Baselines: Results across papers are often not directly comparable due to differing training protocols, data sampling schemes, and evaluation regions.

- Inconsistent Reporting: Studies may report only error metrics, omitting critical training diagnostics such as convergence time or gradient behavior.

- No Ground Truth for Real-World Inverse Problems: In many scientific applications, the exact solution is unknown, making surrogate benchmarking difficult [82].

- Neglected Generalization Metrics: PINNs are rarely evaluated on their ability to generalize across PDE parameters, geometries, or domains—an important aspect for true operator learning.

8. Challenges, Limitations, and Open Problems

8.1. Optimization Landscape and Training Instabilities

- The PDE residual component of the loss may exhibit high stiffness, leading to vanishing gradients in early layers (gradient pathologies).

- The loss terms may have significantly different magnitudes, necessitating sophisticated loss balancing or dynamic reweighting schemes (e.g., NTK-based weights, adaptive residual weighting).

- Overparameterized networks often converge to poor minima that satisfy the data terms but poorly approximate the solution manifold.

8.2. Expressivity and Approximation Theory

- PINNs struggle to capture sharp gradients, shocks, or discontinuities, such as those found in hyperbolic PDEs and multiphase flows.

- In multi-scale problems (e.g., turbulent flow), the global nature of the neural representation may smooth out fine-grained features unless explicitly encoded using hierarchical or Fourier-based structures.

- There is a lack of a priori error bounds or convergence guarantees for PINNs under general conditions.

8.3. Scalability and High-Dimensional PDEs

- The number of collocation points and gradient evaluations increases steeply with the problem size.

- Training time grows nonlinearly with input dimension, limiting use in climate models, molecular dynamics, or plasma physics where .

8.4. Data-Physics Conflicts and Label Inconsistency

- Overfitting to noisy or incorrect labels at the expense of physical fidelity.

- Inability to resolve model discrepancies due to unmodeled physics, missing terms, or coarse discretization.

- Instability in inverse problems where the ground truth is ill-posed or ambiguous.

8.5. Generalization and Transfer Learning in PDE Settings

- How do PINNs generalize to new geometries, boundary conditions, or PDE coefficients not seen during training?

- Can pretrained PINNs on a family of PDEs be fine-tuned efficiently (e.g., transfer learning) [31]?

- How robust are PINNs to small perturbations in input conditions or model parameters?

8.6. Interpretability and Physical Insight

8.7. Integration into Scientific Workflows

8.8. Summary of Limitations and Research Gaps

9. Future Directions and Opportunities

9.1. Hybrid Modeling: Bridging Data and Simulation

- Embed numerical solvers as differentiable modules within deep architectures (e.g., physics-informed recurrent solvers).

- Use PINNs to correct or augment coarse-grid solvers, serving as learned subgrid models or data-driven closures [96].

- Couple PINNs with classical methods such as finite elements (FEM) or boundary element methods (BEM) in multi-resolution or multi-physics setups [97].

9.2. Probabilistic and Bayesian PINNs

- Bayesian formulations of PINNs using stochastic variational inference or Hamiltonian Monte Carlo.

- Deep ensembles or dropout-based Bayesian approximations to capture epistemic uncertainty.

- PINNs as priors in probabilistic graphical models for inverse problems [100].

9.3. Operator Learning and Meta-Learning for PINNs

- Meta-learning across PDE families, geometries, or boundary conditions, where a PINN model can adapt rapidly to new tasks [103].

- Learning parameterized PDE solvers as reusable surrogates that generalize beyond single simulations.

- Incorporating differentiable optimization or bilevel learning into the PINN framework for PDE-constrained problems.

9.4. Geometry-Aware and Mesh-Compatible Architectures

- Using graph neural networks (GNNs) or mesh-based convolutions to process non-Euclidean domains.

- Incorporating spectral methods or manifold learning to represent irregular geometries.

- Leveraging symmetry and invariance principles (e.g., gauge symmetries, Lie groups) to inform network architecture.

9.5. Neurosymbolic and Interpretable PINNs

- Develop sparse PINN architectures that can recover underlying governing equations (e.g., Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics—SINDy).

- Combine neural representations with logic rules or physics ontologies for mixed-symbolic reasoning.

- Enable interactive tools for domain experts to query, interpret, and validate PINN behaviors [107].

9.6. Hardware-Aware and Real-Time PINNs

9.7. Standardization and Community Infrastructure

- Public benchmark suites with reproducible pipelines and baseline models.

- Domain-specific extensions of PINN toolkits (e.g., for electromagnetics, fluid dynamics, or medical physics) [111].

- Common standards for dataset formats, geometry representation, and loss function design.

- Collaborative platforms for crowdsourced model development and cross-lab evaluations [112].

9.8. Cross-Disciplinary Integration and Education

- Interdisciplinary curricula and workshops to bridge technical vocabularies and methodological gaps.

- Inclusion of PINNs in graduate courses on scientific computing, ML for physics, and data-driven engineering.

- Joint research initiatives and funding programs that support long-horizon, high-risk ideas.

10. Conclusions and Outlook

References

- Cao, L.; Lin, Z.; Tan, K.C.; Jiang, M. Interpretable Solutions for Multi-Physics PDEs Using T-NNGP 2025.

- Oszkinat, C.; Luczak, S.E.; Rosen, I. Uncertainty quantification in estimating blood alcohol concentration from transdermal alcohol level with physics-informed neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sun, W.; Song, X. Designing a shape–performance integrated digital twin based on multiple models and dynamic data: a boom crane example. Journal of Mechanical Design 2021, 143, 071703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penwarden, M.; Zhe, S.; Narayan, A.; Kirby, R.M. A metalearning approach for physics-informed neural networks (PINNs): Application to parameterized PDEs. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 477, 111912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, L.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Feng, Z. A Novel Multi-Fidelity Surrogate for Efficient Turbine Design Optimization. Journal of Turbomachinery 2024, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, G.; Claessens, B.; Develder, C. Physics informed neural networks for control oriented thermal modeling of buildings. Applied Energy 2022, 314, 118852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2017; pp. 1126–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2009, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, C.a. Adaptive transfer learning for PINN. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 490, 112291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, A.; Achiam, J.; Schulman, J. 2018; arXiv:cs.LG/1803.02999].

- Zhang, D.; Lu, L.; Guo, L.; Karniadakis, G.E. Quantifying total uncertainty in physics-informed neural networks for solving forward and inverse stochastic problems. Journal of Computational Physics 2019, 397, 108850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Physics-informed learning of governing equations from scarce data. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, L. NAS-PINN: neural architecture search-guided physics-informed neural network for solving PDEs. Journal of Computational Physics 2024, 496, 112603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, S.; Di Cola, V.S.; Giampaolo, F.; Rozza, G.; Raissi, M.; Piccialli, F. Scientific machine learning through physics–informed neural networks: Where we are and what’s next. Journal of Scientific Computing 2022, 92, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davi, C.; Braga-Neto, U. PSO-PINN: physics-informed neural networks trained with particle swarm optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.01943, arXiv:2202.01943 2022.

- Fuks, O.; Tchelepi, H.A. Limitations of physics informed machine learning for nonlinear two-phase transport in porous media. Journal of Machine Learning for Modeling and Computing 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Mao, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM review 2021, 63, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Koohy, S. Gpt-pinn: Generative pre-trained physics-informed neural networks toward non-intrusive meta-learning of parametric pdes. Finite Elements in Analysis and Design 2024, 228, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, A.; Schulman, J. Reptile: a scalable metalearning algorithm. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.02999 2018, arXiv:1803.02999 2018, 2, 42, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Doh, J.; Raju, N.; Raghavan, N.; Rosen, D.W.; Kim, S. Bayesian inference-based decision of fatigue life model for metal additive manufacturing considering effects of build orientation and post-processing. International Journal of Fatigue 2022, 155, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowlavi, S.; Nabi, S. Optimal control of PDEs using physics-informed neural networks. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 473, 111731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mishra, B. Neuroevolving monotonic PINNs for particle breakage analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI). IEEE; 2024; pp. 993–996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Gupta, A.; Chen, Z.; Ong, Y.S. Multitask Neuroevolution for Reinforcement Learning with Long and Short Episodes. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandel, N.; Weinmann, M.; Neidlin, M.; Klein, R. Spline-pinn: Approaching pdes without data using fast, physics-informed hermite-spline cnns. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol.

- Michoski, C.; Milosavljević, M.; Oliver, T.; Hatch, D.R. Solving differential equations using deep neural networks. Neurocomputing 2020, 399, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. Journal of global optimization 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaros, A.F.; Kawaguchi, K.; Karniadakis, G.E. Meta-learning PINN loss functions. Journal of computational physics 2022, 458, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proceedings of the IEEE 2020, 109, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Ueda, N. Meta-learning of Physics-informed Neural Networks for Efficiently Solving Newly Given PDEs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.13270, arXiv:2310.13270 2023.

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Peng, W.; Zhou, W.; Yao, W. A novel meta-learning initialization method for physics-informed neural networks. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 14511–14534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toloubidokhti, M.; Ye, Y.; Missel, R.; Jiang, X.; Kumar, N.; Shrestha, R.; Wang, L. DATS: Difficulty-Aware Task Sampler for Meta-Learning Physics-Informed Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrhofer, F.M.; Posch, S.; Gößnitzer, C.; Geiger, B.C. On the apparent Pareto front of physics-informed neural networks. IEEE Access 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, A.; Bu, J.; Wang, S.; Perdikaris, P.; Karpatne, A. Mitigating propagation failures in physics-informed neural networks using retain-resample-release (r3) sampling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023, pp.

- Pellegrin, R.; Bullwinkel, B.; Mattheakis, M.; Protopapas, P. Transfer learning with physics-informed neural networks for efficient simulation of branched flows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.00214, arXiv:2211.00214 2022.

- McClenny, L.; Braga-Neto, U. 2022; arXiv:cs.LG/2009.04544].

- Ruiz Herrera, C.; Grandits, T.; Plank, G.; Perdikaris, P.; Sahli Costabal, F.; Pezzuto, S. Physics-informed neural networks to learn cardiac fiber orientation from multiple electroanatomical maps. Engineering with Computers 2022, 38, 3957–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Tong, Y.; Neri, F. An ensemble of differential evolution and Adam for training feed-forward neural networks. Information Sciences 2022, 608, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prantikos, K.; Chatzidakis, S.; Tsoukalas, L.H.; Heifetz, A. Physics-informed neural network with transfer learning (TL-PINN) based on domain similarity measure for prediction of nuclear reactor transients. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 16840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazé, F.; Ahmed, F. Diffusion models beat gans on topology optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2023, Vol.

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Bengio, S.; Cloutier, J. Learning a synaptic learning rule; Citeseer, 1990.

- Ma, W.; Liu, Z.; Kudyshev, Z.A.; Boltasseva, A.; Cai, W.; Liu, Y. Deep learning for the design of photonic structures. Nature Photonics 2021, 15, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S. Transfer learning based multi-fidelity physics informed deep neural network. Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 426, 109942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temam, R. Navier–Stokes equations: theory and numerical analysis; Vol. 343, American Mathematical Society, 2024.

- Peiró, J.; Sherwin, S. Finite difference, finite element and finite volume methods for partial differential equations. Handbook of Materials Modeling: Methods, 2415. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Zheng, Z.; Ding, C.; Cai, J.; Jiang, M. Genetic programming symbolic regression with simplification-pruning operator for solving differential equations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing. Springer; 2023; pp. 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Taccari, M.L.; Chen, X. Loss-attentional physics-informed neural networks. Journal of Computational Physics 2024, 501, 112781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, A.M.; Marrero, C.O.; Perdikaris, P.; Tartakovsky, G.D.; Barajas-Solano, D. Physics-informed deep neural networks for learning parameters and constitutive relationships in subsurface flow problems. Water Resources Research 2020, 56, e2019WR026731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Q.J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y. Training behavior of deep neural network in frequency domain. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing: 26th International Conference, ICONIP 2019, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2019, Proceedings, Part I 26. Springer, 2019, December 12–15; pp. 264–274.

- Ong, Y.S.; Gupta, A. Air 5: Five pillars of artificial intelligence research. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2019, 3, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, N.; Wong, J.C.; Ooi, C.C.; Gupta, A.; Chiu, P.H.; Ong, Y.S. Neuroevolution of physics-informed neural nets: benchmark problems and comparative results. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Companion Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, 2023, pp.

- Khoo, Y.; Lu, J.; Ying, L. Solving parametric partial differential equations using the neural convolution. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 2021, 43, A1697–A1719. [Google Scholar]

- Von Rueden, L.; Mayer, S.; Beckh, K.; Georgiev, B.; Giesselbach, S.; Heese, R.; Kirsch, B.; Pfrommer, J.; Pick, A.; Ramamurthy, R.; et al. Informed Machine Learning–A taxonomy and survey of integrating prior knowledge into learning systems. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021, 35, 614–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mishra, B.K. Globally optimized dynamic mode decomposition: A first study in particulate systems modelling. Theoretical and Applied Mechanics Letters, 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Gunning, D.; Aha, D. DARPA’s explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) program. AI magazine 2019, 40, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Cao, B.T.; Yuan, Y.; Meschke, G. Transfer learning based physics-informed neural networks for solving inverse problems in engineering structures under different loading scenarios. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2023, 405, 115852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, R.; Kraus, M. Multi-objective loss balancing for physics-informed deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.09813, arXiv:2110.09813 2021.

- Mustajab, A.H.; Lyu, H.; Rizvi, Z.; Wuttke, F. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for High-Frequency and Multi-Scale Problems Using Transfer Learning. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, S.; He, D.; Wang, L. Is L2 Physics-Informed Loss Always Suitable for Training Physics-Informed Neural Network? arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.02016, arXiv:2206.02016 2022.

- Hochreiter, S.; Younger, A.S.; Conwell, P.R. Learning to learn using gradient descent. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks—ICANN 2001: International Conference Vienna, Austria, 2001 Proceedings 11. Springer, 2001, August 21–25; pp. 87–94.

- Négiar, G.; Mahoney, M.W.; Krishnapriyan, A.S. Learning differentiable solvers for systems with hard constraints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.08675, arXiv:2207.08675 2022.

- Wong, J.C.; Gupta, A.; Ong, Y.S. Can transfer neuroevolution tractably solve your differential equations? IEEE Computational Intelligence Magazine 2021, 16, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, K.O.; Miikkulainen, R. Evolving neural networks through augmenting topologies. Evolutionary computation 2002, 10, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, R.; Mo, Z.; Di, X. Physics-informed deep learning for traffic state estimation: A hybrid paradigm informed by second-order traffic models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, Vol.

- Goswami, S.; Anitescu, C.; Chakraborty, S.; Rabczuk, T. Transfer learning enhanced physics informed neural network for phase-field modeling of fracture. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics 2020, 106, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; Bruno, G.; Cipriani, C. The Challenges of the Nonlinear Regime for Physics-Informed Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03864, arXiv:2402.03864 2024.

- Davi, C.; Braga-Neto, U. Multi-Objective PSO-PINN. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on the Synergy of Scientific and Machine Learning Modeling@ ICML2023; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Alkhalifah, T. Meta-PINN: Meta learning for improved neural network wavefield solutions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.11502, arXiv:2401.11502 2024.

- Cho, W.; Jo, M.; Lim, H.; Lee, K.; Lee, D.; Hong, S.; Park, N. Parameterized physics-informed neural networks for parameterized PDEs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.09446, arXiv:2408.09446 2024.

- Hennigh, O.; Narasimhan, S.; Nabian, M.A.; Subramaniam, A.; Tangsali, K.; Fang, Z.; Rietmann, M.; Byeon, W.; Choudhry, S. NVIDIA SimNet™: An AI-accelerated multi-physics simulation framework. In Proceedings of the Computational Science–ICCS 2021: 21st International Conference, Krakow, Poland, 2021, Proceedings, Part V. Springer, 2021, June 16–18; pp. 447–461.

- Cai, S.; Mao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yin, M.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) for fluid mechanics: A review. Acta Mechanica Sinica 2021, 37, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cheung, K.C.; Ng, M.K. Svd-pinns: Transfer learning of physics-informed neural networks via singular value decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1443–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y. An evolutionary algorithm for large-scale sparse multiobjective optimization problems. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2019, 24, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Mattheakis, M.; Joy, H.; Protopapas, P.; Roberts, S. One-shot transfer learning of physics-informed neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.11286, arXiv:2110.11286 2021.

- Xiong, Y.; Duong, P.L.T.; Wang, D.; Park, S.I.; Ge, Q.; Raghavan, N.; Rosen, D.W. Data-driven design space exploration and exploitation for design for additive manufacturing. Journal of Mechanical Design 2019, 141, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Perdikaris, P. When and why PINNs fail to train: A neural tangent kernel perspective. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 449, 110768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Jin, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Deeponet: Learning nonlinear operators for identifying differential equations based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.03193, arXiv:1910.03193 2019.

- Yuan, G.; Zhuojia, F.; Jian, M.; Xiaoting, L.; Haitao, Z. Curriculum-Transfer-Learning Based Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Long-Time Simulation of Nonlinear Wave. SSRN 2023, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpatne, A.; Atluri, G.; Faghmous, J.H.; Steinbach, M.; Banerjee, A.; Ganguly, A.; Shekhar, S.; Samatova, N.; Kumar, V. Theory-guided data science: A new paradigm for scientific discovery from data. IEEE Transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2017, 29, 2318–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yao, D.; Pervez, A.; Alistarh, D.; Locatello, F. Scalable Mechanistic Neural Networks. arXiv [cs.LG].

- He, X.; Yang, L.; Gong, Z.; Pang, Y.; Li, J.; Kan, Z.; Song, X. Digital Twin-based Online Structural Optimization? Yes, It’s Possible! Thin-Walled Structures 2024, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihlo, A. Improving physics-informed neural networks with meta-learned optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, J.P.; Grauer, S.J. Flow field tomography with uncertainty quantification using a Bayesian physics-informed neural network. Measurement Science and Technology 2022, 33, 065305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Efficient tensor decomposition-based filter pruning. Neural Networks 2024, 178, 106393. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ha, D. Evojax: Hardware-accelerated neuroevolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, 2022, pp.

- Wu, C.; Zhu, M.; Tan, Q.; Kartha, Y.; Lu, L. A comprehensive study of non-adaptive and residual-based adaptive sampling for physics-informed neural networks. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2023, 403, 115671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Yang, J. On computing the hyperparameter of extreme learning machines: Algorithm and application to computational PDEs, and comparison with classical and high-order finite elements. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 463, 111290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouli, S.C.; Alam, M.; Ribeiro, B. MetaPhysiCa: Improving OOD Robustness in Physics-informed Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Jin, Y. A random forest-assisted evolutionary algorithm for data-driven constrained multiobjective combinatorial optimization of trauma systems. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2018, 50, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.C.; Ji, Z.D.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.X.; Li, Z. A Physics-Informed Composite Network for Modeling of Electrochemical Process of Large-Scale Lithium-Ion Batteries. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, J.A.; Grossmann, I.E. An algorithm for the use of surrogate models in modular flowsheet optimization. AIChE journal 2008, 54, 2633–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervez, A.; Locatello, F.; Gavves, E. Mechanistic Neural Networks for scientific machine learning. arXiv [cs.LG].

- Wang, S.; Sankaran, S.; Perdikaris, P. Respecting causality for training physics-informed neural networks. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2024, 421, 116813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, E.; Abouali, S.; Vaziri, R. Constitutive model characterization and discovery using physics-informed deep learning. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 120, 105828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Hong, H.; Jiang, M. Fast Solving Partial Differential Equations via Imitative Fourier Neural Operator. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Yao, Q.; Yang, G. A neural network-based PDE solving algorithm with high precision. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhn, Q.A.; Tano, M.E.; Ragusa, J.C. Physics-informed neural network with fourier features for radiation transport in heterogeneous media. Nuclear Science and Engineering 2023, 197, 2484–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Teng, Y.; Perdikaris, P. Understanding and mitigating gradient flow pathologies in physics-informed neural networks. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 2021, 43, A3055–A3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liao, Y.; Yang, H.; Xie, L. A transfer learning-physics informed neural network (TL-PINN) for vortex-induced vibration. Ocean Engineering 2022, 266, 113101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnapriyan, A.; Gholami, A.; Zhe, S.; Kirby, R.; Mahoney, M.W. Characterizing possible failure modes in physics-informed neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 26548–26560. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Luo, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Long, M. RoPINN: Region Optimized Physics-Informed Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14369, arXiv:2405.14369 2024.

- Lu, L.; Pestourie, R.; Yao, W.; Wang, Z.; Verdugo, F.; Johnson, S.G. Physics-informed neural networks with hard constraints for inverse design. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 2021, 43, B1105–B1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, F.; King, R. State–space modeling for control based on physics-informed neural networks. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2021, 101, 104195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R. Multitask learning. Machine learning 1997, 28, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngördü, U.; Kestner, J. Robust quantum gates using smooth pulses and physics-informed neural networks. Physical Review Research 2022, 4, 023155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, N.; Baratin, A.; Arpit, D.; Draxler, F.; Lin, M.; Hamprecht, F.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. On the spectral bias of neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 5301–5310. [Google Scholar]

- Coello, C.A.C. Evolutionary algorithms for solving multi-objective problems; Springer, 2007.

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Karniadakis, G.E. Gradient-enhanced physics-informed neural networks for forward and inverse PDE problems. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2022, 393, 114823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, D.Q.; Yang, S.; Sun, G. Global and local surrogate-assisted differential evolution for expensive constrained optimization problems with inequality constraints. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2018, 49, 1642–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strategy | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Weighting (NTK, GradNorm) | Dynamically adjusts to balance gradients or curvature. | Wang et al. (2021), Yu et al [28]. (2022) |

| Residual-based Sampling (RAR, AS-PINN) | Selects collocation points based on residual magnitude to improve training focus [29]. | Lu et al. (2021) |

| Curriculum Learning | Trains the model on simpler versions of the PDE before gradually increasing complexity. | Meng et al. (2020) |

| Domain Decomposition (XPINN) | Splits domain into subregions to parallelize and localize training [9]. | Jagtap et al. (2020) |

| Output Normalization | Rescales the PDE solution output for numerical stability during training. | Kissas et al [30]. (2020) |

| Multi-Fidelity Supervision | Combines coarse simulations with high-fidelity data. | Meng et al. (2021) |

| Extension | Key Feature | Target Problem |

|---|---|---|

| XPINNs | Domain decomposition | Large-scale, multi-physics |

| cPINNs | Integral conservation loss | Conservation laws |

| hpPINNs | Adaptive resolution | Multi-scale problems |

| DeepONets | Operator learning | Parameterized PDEs |

| FNOs | Global convolution in Fourier space | High-resolution spatiotemporal data |

| VPINNs | Variational formulation | Weak-form PDEs |

| Bayesian PINNs | Posterior inference | Uncertainty quantification |

| Multi-modal PINNs | Data fusion from sensors/images | Inverse problems in biomedicine |

| Problem | Equation | Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1D Burgers Equation | Viscous shocks, nonlinearity | |

| 2D Navier–Stokes | Incompressible flow equations | Cylinder flow, cavity flow |

| 1D Heat Equation | Diffusion modeling | |

| Wave Equation | Oscillatory dynamics | |

| Poisson Equation | Electrostatics, steady-state heat | |

| Darcy Flow | Subsurface flow, porous media | |

| Schrödinger Eq. | Quantum systems |

| Category | Limitation / Open Problem |

|---|---|

| Optimization | Stiff PDE loss, imbalance, gradient pathologies |

| Approximation | Difficulty modeling discontinuities or fine scales |

| Scalability | Poor performance on high-dimensional, long-time simulations |

| Data Conflict | Instability due to noisy or conflicting measurements |

| Generalization | Weak transfer to unseen PDEs, geometries, conditions |

| Interpretability | Black-box nature limits scientific insight |

| Deployment | Complex setup and integration into existing workflows |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).