1. Introduction

Floral reward chemistry is the complex and dynamic composition of chemicals flowers produce, such as nectar and pollen, to attract and influence pollinators like bees. These rewards contain primary metabolites such as carbohydrates, amino acids, and lipids, as well as secondary chemicals like alkaloids and phenolics, all of which can influence pollinator behaviour, preferences, and health. The composition of these rewards is influenced by evolutionary specialisation and ecological adaptability, which alter plant-pollinator interactions across locales.(Leonhardt et al., 2024; Nicolson & Thornburg, 2007).

Floral reward chemistry is crucial in plant-pollinator interactions by influencing pollinator behaviour through chemical signals and responses. In 2000, Reis et al. observed that most flowers and their pollinators engage in mutualistic relationships fundamental to chemical ecology. Jeffrey (2018) further outlines that these interactions are in three stages: (1) flowers attract pollinators using scent and colour, (2) pollinators visit flowers seeking rewards such as nectar, pollen, or nesting materials, and (3) pollen is exchanged between flowers and pollinators, facilitating pollination. Beyond these mutualistic relationships, Palmer-Young et al. (2018) highlighted that floral reward chemistry extends its influence beyond pollinators, affecting flower-visiting antagonists and microbial communities interacting with floral structures. This complexity highlights the importance of exploring the factors that drive variations in floral reward chemistry.

Studies have shown that geographic and genetic influences shape the chemical composition of floral rewards (Majetic, Raguso and Ashman, 2009; Gross, Sun and Schiestl, 2016; Egan et al., 2018), ultimately affecting plant-pollinator interactions. Geographic factors like climate and surrounding flora contribute to regional differences in nectar and volatile organic compound (VOC) production (Manincor et al., 2021). Simultaneously, genetic variation within plant populations can lead to distinct chemical profiles, influencing pollinator preferences and reproductive success (Manincor et al., 2021). These dynamics are particularly relevant in Vaccinium species (Blueberries), which rely on insect pollination for fruit production. Recent studies on wild and cultivated blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium and Vaccinium corymbosum) have shown that environmental conditions and genetic diversity significantly impact floral traits, including nectar composition and volatile emissions (Egan et al., 2018; Cromie et al., 2024). Consequently, investigating how geographic and genetic factors shape floral reward chemistry in blueberries provides a deeper understanding of the ecological and evolutionary pressures influencing pollination success in this economically and ecologically important genus. This intricacy emphasises the importance of recognising genetic and environmental factors to thoroughly comprehend how floral reward chemistry affects pollination dynamics in various environments.

2. Environmental Influence on Floral Reward Chemistry

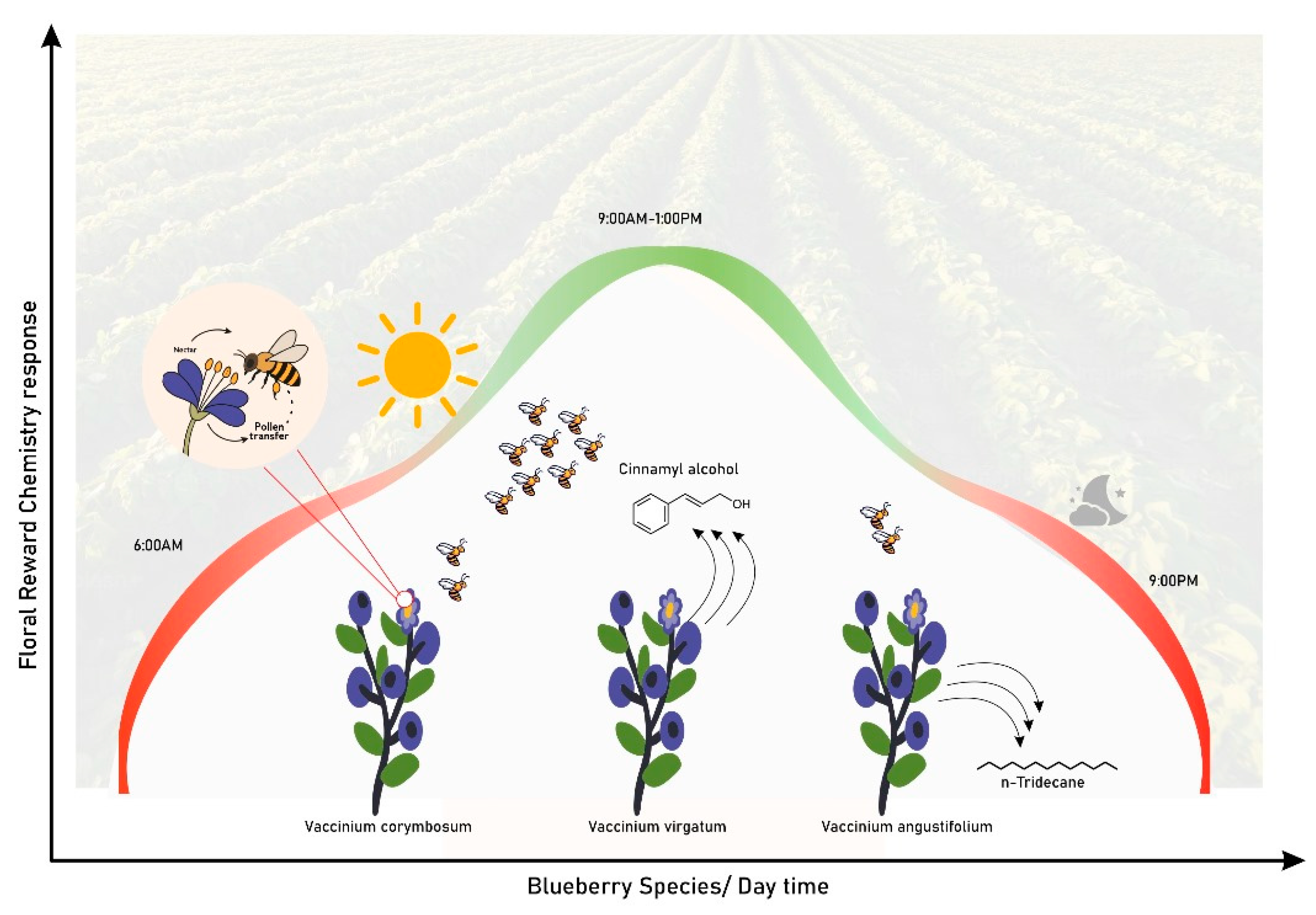

Environmental conditions significantly influence the chemical composition of floral rewards in blueberries (Vaccinium species), shaping nectar and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions. Studies have shown that variations in climate, soil properties, and local flora can modulate these chemical signals, impacting pollinator attraction and plant fitness. Temporal variations in volatile emissions further emphasise the role of environmental regulation in floral reward chemistry. According to Rodriguez-Saona et al. (2011), while cinnamyl alcohol levels in Vaccinium corymbosum remained stable across different times of the day, other floral volatiles peaked at midday, coinciding with optimal pollinator foraging activity. This suggests that environmental factors, such as light intensity and temperature, regulate the biosynthesis of key volatiles, thereby enhancing pollinator attraction during the most effective foraging periods.

Beyond daily fluctuations, geographic differences also impact floral volatile emissions and nectar composition. As observed by Forney et al. (2023) when investigating the role of species, cultivar, and growing location in determining the chemical profiles of blueberry fruit, including sugars, organic acids, and volatiles. The study revealed that lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium) and highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) exhibited distinct volatile compositions, with additional variations observed among different cultivars and geographical locations. These findings indicate that local climatic conditions and soil properties influence floral chemistry, affecting pollinator behaviour and fruit quality.

Furthermore, heritability studies have further substantiated the dominant influence of environmental factors over genetic determinants in shaping floral rewards or volatiles. Huber, Bohlmann, and Ritland (2023) assessed the heritability of floral volatile compounds in blueberries and discovered that these compounds were relatively low (~15%). This suggests that even within genetically similar populations, VOC emissions can vary significantly due to external environmental factors and biotic interactions. Thus, the geographic setting of blueberry populations plays a crucial role in determining the chemical composition of floral rewards. These findings underscore the necessity of considering environmental variability in studies of floral reward chemistry nonetheless, genetic factors further refine and stabilize these chemical signals across plant populations, as discussed below.

3. Genetic Differences in Floral Chemistry

Genetic variation plays a fundamental role in shaping the chemical composition of floral rewards in blueberries, particularly nectar composition and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions. Studies have demonstrated that different cultivars of highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) exhibit significant variation in floral chemistry, even under similar environmental conditions. Forney et al. (2023) reported that sugar, acid, and volatile profiles differed among genotypes, highlighting the role of genetic factors in regulating these traits. Ventorim et al. (2020) identified key genomic regions associated with VOC biosynthesis in blueberries using metabolite genome-wide association studies (mGWAS). This study revealed that some of these genomic regions contain genes encoding biosynthetic enzymes, suggesting that genetic factors partially control VOC production. Additionally, predictive models based on genomic markers accurately forecast VOC profiles, reinforcing the heritable nature of floral and fruit scent composition. (Cromie et al., 2024) demonstrated that genotypic variation among 38 southern highbush blueberry cultivars significantly influenced nectar volume, a key determinant of floral reward chemistry. The study reported moderate to high narrow-sense heritability (h² = 0.30 to 0.77) for nectar traits, indicating a strong genetic basis for their regulation. Additionally, volatile emissions vary across genotypes due to differences in metabolic pathways and genetic regulation. Rodriguez Saona et al. (2011) found that while some volatile compounds, such as cinnamyl alcohol, remained stable across cultivars, others exhibited significant genetic variation, further supporting the role of genetic background in VOC emissions. These findings highlight the crucial role of genetic variation in shaping the floral reward chemistry of blueberries.

4. Methods of Investigating Environmental and Genetic Influences on Floral Reward Chemistry and VOCs of Blueberries

4.1. Experimental Techniques in VOC Profiling

Rodriguez-Saona et al. (2011) and Huber et al. (2023) investigated floral volatile organic compounds (VOCs) while considering environmental factors. Specifically, Rodriguez-Saona et al. (2011) employed headspace solid-phase microextraction (SPME) in field conditions to collect floral volatiles at various times of the day and from individual floral organs. These volatiles were analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to determine how pollination status, cultivar, and time of day influenced VOC emissions.

Similarly, Huber et al. (2023) collected floral VOCs using airflow chambers and oven bags, sampling floral and leaf tissues separately to control contamination. Volatile collection occurred at peak bloom, with samples stored at -20°C before GC-MS analysis. Importantly, internal standards were used to normalize peak areas, ensuring reliable quantification. Furthermore, the study included solvent and environmental controls to separate genetics from environmental effects, ensuring only compounds consistently present in floral samples were analysed.

Building on these environmental assessments, Forney et al. (2023) and Rowland et al. (2023) conducted typical garden and multi-site trials to distinguish genetic influences from environmental variation in floral chemistry. These trials helped estimate heritability by evaluating variance in VOCs across different growing conditions. Additionally, field experiments examined pollinator responses to variations in VOCS, providing an ecological context for volatile emissions. Complementing these studies, Sater et al. (2020) reviewed analytical methods used in VOC research, highlighting the dominance of SPME-GC-MS in modern studies due to its efficiency and automation capabilities. Historically, alternative methods such as dynamic headspace trapping, solvent extraction, and distillation were widely used. However, SPME has largely replaced these techniques due to its reliability. Recently, newer approaches have been introduced, including proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PTR-TOF-MS) and fast gas chromatography-surface acoustic wave (FGC-SAW). While promising, these methods have not yet matched SPME’s detection capability. However, characterizing heritable traits requires genetic dissection beyond volatile profiling alone, necessitating robust quantitative genetic methodologies

4.2. Quantitative Genetic Approaches to Heritability

Shifting focus to genetic influences, Ventorim et al. (2020) and Rowland et al. (2023) examined the genetic basis of VOC emissions using metabolite-genome-wide association studies (mGWAS) and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping. These methods linked specific genetic variants to VOC composition by correlating single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPS) with volatile profiles. To achieve this, VOCs were collected using HS-SPME, followed by GC-MS for compound identification and quantification. In addition, transcriptomic analysis further validated candidate genes involved in volatile biosynthesis.

Further advancing genetic analysis, Huber et al. (2023) explored genetic influences by employing clonal repeatability analysis to estimate broad-sense heritability, comparing VOC variation within and between clones. Moreover, microsatellite markers were used for marker covariance analysis, estimating narrow-sense heritability based on genetic relatedness among genotypes. Through this combined approach, the study distinguished VOCs with strong genetic control from those influenced by environmental conditions. Emerging trends in genetic methodologies include multi-omics approaches that integrate genomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics (Ventorim et al., 2020). Machine learning models predicting volatile profiles based on genetic markers are also gaining traction. Collectively, these approaches enhance the ability to identify genetic determinants of floral chemistry and their implications for breeding and pollination ecology.

5. Gaps in Both Geographic and Genetic Research

Environmental Interactions and Abiotic Complex

Despite advances in understanding the genetic and environmental influences on floral reward chemistry in blueberries, several knowledge gaps remain. Rodriguez Saona et al. (2011) highlighted the need to explore how multiple environmental factors interact to shape volatile organic compound emissions over time. Their study acknowledged that while pollination status, cultivar, and floral organ influence volatile organic compound emissions, the combined effects of abiotic factors such as temperature, humidity, and soil composition remain understudied. Similarly, Huber et al. (2023) noted the challenge of disentangling environmental variability from genetic contributions, emphasising that although common garden experiments help control site effects, microenvironmental fluctuations can still introduce noise into volatile organic compound measurements.

Genetic Architecture and Regulatory Pathways

From a genetic perspective, Ventorim et al. (2020) underscored the limitation of current metabolite genome-wide association studies in capturing the full complexity of volatile organic compound biosynthesis. They pointed out that single-nucleotide polymorphism markers can be associated with specific volatile organic compound traits, and the regulatory networks governing these pathways require further transcriptomic and functional validation. Rowland et al. (2023) reinforced this by identifying a gap in understanding how genetic variation influences floral reward chemistry across different environments, emphasising that gene-environment interactions are still poorly resolved. Forney et al. (2023) similarly suggested that while heritability estimates provide insights into genetic control, they do not fully capture the plasticity of floral volatile organic compounds in response to environmental changes.

Technical limitations in VOC sampling and Analysis

Several challenges complicate research in this field. Sater et al. (2020) noted the technical limitations of volatile organic compound collection methods, particularly the trade-offs between sensitivity, repeatability, and field applicability. While solid phase microextraction is widely used, they pointed out that it may not accurately capture highly volatile or short-lived compounds. Palmer Young et al. (2018) also highlighted the need for ecological network analyses incorporating microbial interactions with floral rewards, suggesting that a more holistic approach is necessary to understand the broader ecological implications of volatile organic compound variation.

Proposed Solutions and Future Research Directions

Several researchers have proposed strategies to address these limitations. For instance, Ventorim et al. (2020) proposed integrating multi-omics approaches combining genomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics to improve predictive models of volatile organic compound production.

Huber et al. (2023) recommended expanding heritability studies using larger genetic populations to refine estimates of genetic influence while controlling for environmental variation.

Forney et al. (2023) further suggested that long-term, multi-site trials could provide more comprehensive insights into the stability of floral reward traits under changing climatic conditions.

Figure 1.

The picture depicts the various environmental and genetic differences influencing Floral reward chemistry and interaction.

Figure 1.

The picture depicts the various environmental and genetic differences influencing Floral reward chemistry and interaction.

6. Conclusion

Significant progress has been made in identifying genetic and environmental influences on floral chemistry in blueberries, but the complexity of these interactions remains a key challenge. Future research should prioritise multidisciplinary approaches integrating genetic, chemical, and ecological perspectives to provide a more comprehensive understanding of floral reward evolution and its implications for pollination ecology.

Research on floral reward chemistry in blueberries reveals that genetic and environmental factors shape nectar composition and volatile organic compound emissions. Geographic variation, including climate and soil conditions, predominantly influences floral chemical profiles, while genetic differences among cultivars further affect floral traits. Studies show some volatiles are heritable, whereas environmental conditions largely shape others. Advanced methodologies such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and genome-wide association studies have enhanced our understanding of these influences. However, challenges remain in disentangling genetic control from environmental variability. Future research should integrate multi-omics approaches and long-term field trials to refine our understanding of floral reward chemistry. A multidisciplinary approach will be essential for optimising pollination success and improving blueberry cultivation.

References

- Leonhardt, S. D., Chui, S. X., & Kuba, K. (2024). The role of non-volatile chemicals of floral rewards in plant-pollinator interactions. Basic and Applied Ecology, 75, 31–43. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, S. W., & Thornburg, R. W. (2007). Nectar chemistry. In S. W. Nicolson, M. Nepi, & E. Pacini (Eds.), Nectaries and Nectar (pp. 215–264). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Cromie, J., Ternest, J.J., Komatz, A.P., Adunola, P.M., Azevedo, C., Mallinger, R.E. and Muñoz, P.R. (2024). Genotypic variation in blueberry flower morphology and nectar reward content affects pollinator attraction in a diverse breeding population. BMC Plant Biology, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Egan, P.A., Adler, L.S., Irwin, R.E., Farrell, I.W., Palmer-Young, E.C. and Stevenson, P.C. (2018). Crop Domestication Alters Floral Reward Chemistry With Potential Consequences for Pollinator Health. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9. [CrossRef]

- Forney, C.F., Qiu, S., Jordan, M.A., Munro Pennell, K. and Fillmore, S. (2023). Impact of species, growing location and cultivar on flavor chemistry of blueberry fruit. Acta Horticulturae, (1357), pp.199–206. [CrossRef]

- Gross, K., Sun, M. and Schiestl, F.P. (2016). Why Do Floral Perfumes Become Different? Region-Specific Selection on Floral Scent in a Terrestrial Orchid. PLOS ONE, 11(2), p.e0147975. [CrossRef]

- Huber, G., Bohlmann, J. and Ritland, K. (2023). Variation and Natural Heritability of Blueberry Floral Volatiles. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 71(21), pp.8121–8128. [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, H. (2018). Introduction to Ecological Biochemistry : Harborne, J. B. (Jeffrey B.) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive. [online] Internet Archive. Available at: https://archive.org/details/introductiontoec0000harb/page/n11/mode/2up [Accessed 4 Mar. 2025].

- Majetic, C.J., Raguso, R.A. and Ashman, T.-L. (2009). Sources of floral scent variation. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 4(2), pp.129–131. [CrossRef]

- Manincor, N. de, Andreu, B., Buatois, B., Chao, H.L., Hautekèete, N., François Massol, Yves Piquot, Schatz, B., Schmitt, E. and Dufay, M. (2021). Geographical variation of floral scents in generalist entomophilous species with variable pollinator communities. Functional Ecology, 36(3), pp.763–778. [CrossRef]

- Mariza Gomes Reis, de, D., Volker Bittrich, Maria and Marsaioli, A.J. (2000). The chemistry of flower rewards -- Oncidium (Orchidaceae). Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 11(6), pp.600–608. [CrossRef]

- Palmer-Young, E. C., Farrell, I. W., Adler, L. S., Milano, N. J., Egan, P. A., Junker, R. R., Irwin, R. E., & Stevenson, P. C. (2018). Chemistry of floral rewards: intra- and interspecific variability of nectar and pollen secondary metabolites across taxa. Ecological Monographs, 89(1). [CrossRef]

- Rering, C.C., Rudolph, A.B., Li, Q.-B., Read, Q.D., Muñoz, P.R., Ternest, J.J. and Hunter, C.T. (2024). A quantitative survey of the blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) culturable nectar microbiome: variation between cultivars, locations, and farm management approaches. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 100(3). [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, C., Parra, L., Quiroz, A. and Isaacs, R. (2011). Variation in highbush blueberry floral volatile profiles as a function of pollination status, cultivar, time of day and flower part: implications for flower visitation by bees. Annals of Botany, 107(8), pp.1377–1390. [CrossRef]

- Sater, H.M., Bizzio, L.N., Tieman, D.M. and Muñoz, P.D. (2020). A Review of the Fruit Volatiles Found in Blueberry and Other Vaccinium Species. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 68(21), pp.5777–5786. [CrossRef]

- Ventorim, F., Johnson, T.S., Benevenuto, J., Edger, P.P., Colquhoun, T.A. and Patricio Muñoz (2020). Genome-wide association of volatiles reveals candidate loci for blueberry flavor. New Phytologist, 226(6), pp.1725–1737. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).