1. Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) is a valuable treatment in cancer management, leveraging ionizing radiation to selectively target and destroy malignant cells. More than half of all cancer patients receive RT as a part of their treatment regimen [

1]. The therapeutic efficacy of RT contributes to approximately 40% of tumor control in multimodal treatment approaches. The specific frequency, duration, and combination with other treatments depend on multiple factors, including the type and stage of the cancer, the patient's overall health, and the treatment goals as well as radiation dosages and duration. However, the primary problem is the damage it causes to the surrounding normal tissues of the malignant tumor [

2]. Observed side effects of RT include chromosomal aberrations, secondary cancers, infertility, internal organs, and skin damage [

3,

4,

5].

One of the prevalent adverse effects of RT is radiation-induced skin injury (RISI), also described as radiodermatitis or radiation dermatitis, which at some levels affects up to 95% of patients undergoing RT. Acute RISI (aRISI) manifests within the first 90 days of radiation treatment and presents as erythema, pigmentation changes, edema, and dry or moist desquamation. Noteworthy, in severe cases, aRISI may necessitate temporary or permanent cessation of RT, jeopardizing the success of the treatment. Chronic RISI, on the other hand, can appear months to years post treatment and includes symptoms such as skin hypersensitivity, dyspigmentation, xerosis, telangiectasia, alopecia, fibrosis, ulcers, and radiation-induced morphea (RIM)[

6,

7]. Although chronic RISI does not interfere directly with the effectiveness of RT, it significantly impacts the patient’s quality of life.

The risk and severity of RISI are influenced by several factors, including higher radiation doses per fraction, greater cumulative doses, concurrent chemotherapy or immunotherapy, and treatment in anatomically sensitive regions in areas with thin skin or skin folds, such as head, neck, breast, and axilla [

8,

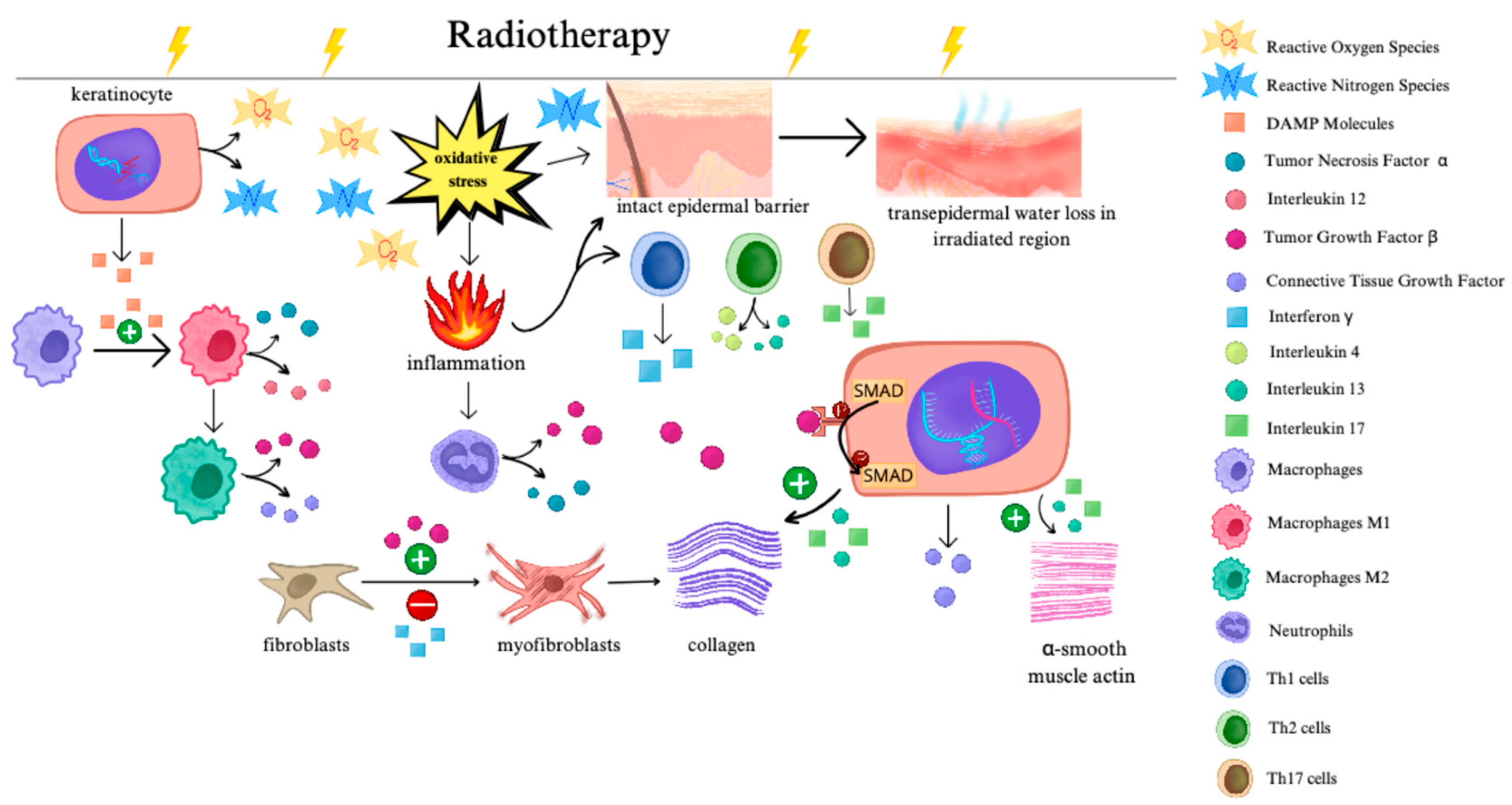

9]. The RT induced damage occurs at the molecular level, leading to extensive DNA damage and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which disrupt critical cellular metabolic processes and induce a complex cascade of signaling pathways [

10]. Within the skin, these effects initiate a cascade of inflammatory responses, including the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and the release of chemokines, adhesion molecules, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including eotaxin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), interleukin (IL)-1, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Together, they contribute to endothelial cell damage, increased vascular permeability, and immune cell recruitment, ultimately leading to local inflammation and skin breakdown [

11]. Monocyte migration to the irradiated skin sites results in their differentiation into macrophages, which secrete platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). These factors, in turn, promote migration of fibroblasts and activation of pro-fibrotic pathways [

12].

Skin damage induced by RT includes direct destruction of the skin layers. A prospective study conducted by Pazdrowski et al. revealed statistically significant differences in transepidermal water loss (TEWL), an indicator of the compromised epidermal barrier, in irradiated skin across various time points [

13]. Furthermore, in patients who had previously undergone RT for head and neck cancer, TEWL was significantly elevated in irradiated regions compared to non-irradiated areas. Notably, the median time since RT was 6 years, and increased TEWL was observed irrespective of the presence of clinical manifestation of cRISI [

14].

The intact epidermal lipid barrier plays a crucial role in inhibiting the overgrowth of pathological microbiota due to the antibacterial properties of skin fatty acids [

15]. Additionally, for many skin commensals, skin lipids serve as an essential nutrient source [

16]. Therefore, damage to the skin barrier induced by RT is a plausible factor contributing to alterations in the skin microbiome in cancer patients.

Figure 1 illustrates changes in skin cells and cell signaling following RT.

The skin microbiome, a vast and diverse community, has been suggested to play a key role in the development and progression of RISI [

17]. The aim of this review is to present current findings on the interaction between skin microbiome and radiation-induced skin damage, and to discuss potential therapeutic strategies for its prevention and management.

2. Skin Microbiome

Skin, the largest organ of the human body, serves as a protective barrier against environmental factors. It is estimated to harbor thousands to millions of microbial cells per square centimeter, depending on the specific region. This diverse microbial population includes bacteria, viruses, fungi, and micro-eukaryotes (e.g. mites), which co-exist in symbiotic relationship with the host. Numerous internal and external factors, influence the distribution and abundance of these microbial communities including age, sex, hormone levels, stress, climate, exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, pollution, or chemicals, as well as hygienic and cosmetic practices [

18,

19,

20]. Additionally, the local composition of glands and hair follicles affects bacterial colonization in different body regions. Sebaceous areas such as face and back are enriched with lipophilic

Cutibacterium species. Moist areas, including the axillary vault, interdigital spaces, and inguinal crease, favor the growth of

Corynebacterium and

Staphylococci species. In contrast dry areas like the inner forearms, are more commonly colonized by

Proteobacteria and

Flavobacteriales [

21]. Among fungi,

Malassezia is the most prevalent genus, accounting for 80% of the skin fungal flora [

22] and is particularly dominant in sebum-rich areas such as face, trunk, and scalp [

23].

Demodex mites, a type of microeukaryote inhabit pilosebaceous follicles, predominantly on the face [

24]. Viruses remain the least studied component of the skin microbiome, with the majority being bacteriophages belonging to families such as

Caudovirales,

Siphoviridae, and

Myoviridae [

25].

The presence of commensal microbiota contributes to upregulation of genes associated with immune and inflammatory response, as well as keratinocyte differentiation. Skin colonization by microorganisms stimulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α and IL-1β by immune cells. Furthermore, the commensal microbiota modulates epidermal proliferation and differentiation by influencing the gene expression of structural proteins, such as filaggrin, repetin, and psoriasin [

26].

Importantly, the skin microbiota plays an essential role in maintaining the skin’s barrier function. For example,

Staphylococcus epidermidis produces sphingomyelinase, an enzyme that facilitates host ceramide synthesis- waxy lipid molecules that prevent dehydration [

27]. In addition, microbes are also responsible for secreting agents that activate aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) in keratinocytes, supporting epidermal differentiation and skin integrity [

28]. Skin also maintains microbial balance through antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and enzymes that regulate the skin's pH and moisture levels. Defensins, including human neutrophil peptides (HNPs), are a class of AMPs-secreted by both keratinocytes and immune cells during inflammation. These peptides exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, directly targeting pathogens and preventing their colonization [

29].

Furthermore, human skin is an active immune organ populated by various immune cells, including Langerhans cells, dermal dendritic cells, macrophages, mast cells, and different subtypes of T cells and B lymphocytes [

30]. Immune cells within the skin interact dynamically with the skin microbiota, and this mutual relationship is crucial for maintaining skin homeostasis.

Staphylococcus epidermidis has been shown to activate gamma delta (GD) T cells and induce the expression of antimicrobial perforin-2 (P-2) [

31]. In murine models, early life colonization of skin with

Staphylococcus epidermidis promotes activation of regulatory T (Treg) cells in the neonatal skin, thereby establishing immune tolerance to commensal microbes [

32]. Interestingly, neonatal colonization with

Staphylococcus aureus but not with

Staphylococcus epidermidis upregulates IL-1β expression and increases the ratio of helper T helper 17 (Th17) cells to Tregs, suggesting a more inflammatory immune response [

33]. Furthermore, commensal colonization with

Staphylococcus epidermidis,

Staphylococcus xylosus,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum, and

Cutibacterium acnes leads to an accumulation of IL-17A- and IFN-γ-expressing T cells in the skin, which in turn upregulates the expression of antimicrobial alarmins S100A8 and S100A6 [

34]. Therefore, colonization with commensal species is a crucial element of effective protection against invasive microbes. Keratinocyte expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) is another factor contributing to homeostatic immunity to commensal colonization, primarily through the accumulation of Th1 cells in the skin [

35]. Importantly, T cells induced by

Staphylococcus epidermidis have been demonstrated to accelerate wound healing in mice [

36]. Interestingly,

Cutibacterium acnes regulates immune tolerance through the production of short-chain free fatty acids (SCFAs), which inhibit the activity of histone deacetylase (HDAC) 8 and 9, and therefore downregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory IL-6 and IL-8 [

37]. These evidence altogether indicate that alterations in the skin microbiome, accompanied by disrupted skin barrier, increase the susceptibility to multiple skin diseases. On the other hand, the presence of inflammation in different skin disorders significantly contributes to dysbiosis [

38].

3. Skin Microbiota in RISI

Studies have shown that RT alters the skin microbial barrier by significantly reducing its abundance and diversity. Noteworthy, the composition of the skin microbiome before the beginning of RT significantly impacts the occurrence and severity of RISI, providing a possible prediction for the disease outcome. However, the results of studies conducted so far are inconclusive. Research by Huang et al. on aRISI rat models revealed a significant predominance of Firmicutes, especially

Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Acetivibrio ethanolgignens, Peptostreptococcus, and

Anaerofilum in rats that developed aRISI after RT, compared to the control group with no previous contact with RT. Researchers additionally analyzed patient data from BioProject 665,254 and observed an overall significant reduction in bacterial diversity following RT, as well as a greater abundance of

Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and

Staphylococcus in patients with RISI compared to healthy subjects. Interestingly, the analysis revealed a significant predominance of Proteobacteria and a low abundance of Firmicutes after RT in the group of patients who developed chronic ulcers [

39].

Another study explored the cutaneous microbiota of 78 patients with RISI, both acute and chronic. Compared to the control group with no RT history, RISI patients exhibited a predominance of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria. RISI was associated with a predominance of

Klebsiella, Staphylococcus, or Pseudomonas, while the skin of healthy subjects was mainly inhabited by

Klebsiella,

Cutibacterium,

Corynebacterium,

Bacillus, and

Paracoccus. In addition, a longer duration of RISI was negatively correlated with the diversity of cutaneous bacteria. A slower healing of RISI was associated with greater amounts of

Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, and

Stenotrophomonas. Consistent with the previous study, chronic ulcers were linked to the predominance of Proteobacteria and a low abundance of Firmicutes. The skin microbiota of these patients consisted mainly of

Klebsiella or

Pseudomonas,

Cutibacterium, and

Stenotrophomonas. The coexistence of

Pseudomonas,

Staphylococcus, and

Stenotrophomonas was strongly correlated with the development of chronic ulcers [

17].

Another study exploring skin microbiota in RISI detected a significantly higher abundance of

Ralstonia,

Truepera, and

Methyloversatilis genera and a lower abundance of

Staphylococcus and

Corynebacterium genera in patients with no/mild aRISI (RTOG 0/1) compared to patients with severe aRISI (RTOG 2 or higher), both before and after RT [

40]. On the other hand, research by Hülpüsch et al. revealed the association between a low number of commensal skin bacteria, i.e.

Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus hominis, and

Cutibacterium acnes at the beginning of the treatment and the development of severe aRISI. Additionally, a non-species-specific overgrowth of skin bacteria has been proven to occur right before the onset of RISI symptoms [

41]. Similarly, another study assessed the composition of cutaneous

Staphylococcus species before RT and linked the low abundance of

Staphylococcus hominis and

Staphylococcus aureus to the development of severe aRISI [

42]. In addition, research by Kost et al. explored the impact of nasal colonization with

Staphylococcus aureus before RT on the development of aRISI in patients with breast and head and neck cancer. The baseline colonization with

Staphylococcus aureus in nares was higher in patients who developed grade 2 or higher aRISI compared to those with grade 1. Interestingly, after RT, the

Staphylococcus aureus colonization was higher in nares, irradiated skin region, and contralateral skin in patients with grade 2 compared to patients with grade 1 aRISI [

43].

Ulceration is one of the most severe clinical manifestations of RISI. Acute ulcers are less frequent and develop on the base of wet desquamation. Conversely, chronic ulcers typically occur in the later stages of the disease [

44]. Patient-related risk factors for ulcer development include concomitant diseases, and a particular composition of the skin microbiota, which, as mentioned above, exhibits several differences when compared to RISI patients without chronic ulcers [

17,

39]. Although the ulceration is a clinical manifestation of RISI, assumptions about its microbiome should not be extrapolated solely from data regarding typical bacteria in RISI.

Table 1 summarizes studies on microbiota in RISI.

It is essential to highlight the bidirectional influence of RISI and skin microbiome. On one hand, RT induces a cascade of events that cause alterations in immune cells and damage to the skin barrier, subsequently leading to dysbiosis. On the other hand, changes in the proportion of different microorganism species residing on the skin have been linked to the development of various types of dermatosis, such as atopic dermatitis (AD), seborrheic dermatitis (SD), among others, and therefore could potentially aggravate RISI. Apart from significantly reducing the diversity of skin microorganisms, the cause-and-effect sequence between RT and skin microbiome needs further investigation.

Overall, the findings suggest a significant impact of RT on creating a potentially favorable environment for the excessive proliferation of pathogens, and as a result, for an exacerbation of inflammatory process and severe skin injuries. First of all, a few studies showed that the predominance of bacterial species from the Firmicutes and/or Proteobacteria phylum was associated with prolonged healing of aRISI. The most frequently detected genera of cutaneous microbiota in patients with aRISI were Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas. On the other hand, research linked the low abundance of Staphylococcus species, specifically Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus hominis, as well as Staphylococcus aureus before RT to either the development of aRISI or severe course of aRISI, suggesting that the cutaneous microbiota composition before RT might be one of the predictors of the RISI course. The major limitation of certain studies is the absence of specification of exact Staphylococcus species that are overgrowth in RISI patients. This information could provide a better understanding of the microbiota characteristics both before and after radiotherapy, as well as its influence on the clinical outcomes. Further research focusing on skin microbiota is needed to help identify these associations. Noteworthy, results were unequivocal regarding the predominance of Proteobacteria and low abundance of Firmicutes in patients who developed chronic ulcers.

4. Management of RISI by Supporting the Skin Microbiome

4.1. Skin Care Products

Implementing preventative actions might alleviate severe cases of aRISI and improve patients’ condition. Proper skin care is well-established and regarded as essential in the prevention and treatment of RISI. The skin should be washed with gentle cleansing products that do not disrupt the hydrolipid barrier, such as synthetic detergents (syndets), while concurrently using emollients to maintain skin moisture and UV protection. Noteworthy, washing irradiated skin solely with water during RT is associated with increased severity of RISI, as well as a higher frequency of moist desquamation and itching compared to washing with water and mild soap [

45].

Emollients are fundamental in the treatment of AD, which, as mentioned before, shares several pathophysiological similarities with RISI [

46,

47]. Emollients are composed of a mixture of lipids, typically in a 3:1:1:1 ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, essential free fatty acids, and non-essential free fatty acids. Additionally, they may contain other lipids, such as mevalonic acid, which has been demonstrated to accelerate the restoration of the hydrolipid barrier. Emollients in AD have been shown to reduce TEWL and restore the hydrolipid barrier, likely by decreasing involucrin, claudin-1, and caspase-14 expression [

48,

49]. Additionally, they reduce the

Staphylococcus aureus population and restore the balance between

Staphylococcus aureus and

Staphylococcus epidermidis, as involucrin is crucial for

Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to skin cells via the staphylococcal adhesion receptor [

50]. "Emollient plus" refers to emollients that contain additional active agents designed to enhance their therapeutic efficacy. Bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, riboflavins, quinones, tannins, catechins, and phenols, commonly derived from botanical extracts such as

Aloe vera,

Curcuma longa,

Calendula officinalis,

Matricaria chamomilla, among others, are incorporated for their bacteriostatic and antioxidant properties [

51,

52]. These compounds act through mechanisms such as inactivating microbial adhesins and cell envelope transport proteins by binding to nucleophilic amino acids in these proteins, as demonstrated

in vitro and in animal models [

52,

53,

54]. However, efficacy data from only a limited number of randomized controlled trials are available for these formulations in the context of RISI, therefore they are not currently recommended in clinical practice [

55]. It is important to highlight that while plant-derived compounds are generally safe, there is a growing number of cosmetics and topical products containing whole-natural botanical extracts. In susceptible individuals, these extracts might cause allergic contact dermatitis [

56].

Moreover, topical probiotics, such as

Vitreoscilla filiformis biomass (VFB) or

Bifidobacterium longum, have been studied [

57,

58]. VFB is widely used in emollient products and has been proven to stimulate the production of antimicrobial peptides through toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)/protein kinase C, zeta pathway (PKCζ), thus modulating the activity of free-radical scavenger mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD) [

59,

60]. Prebiotics, such as fructooligosaccharides (FOS), galactooligosaccharides (GOS), lactosucrose, glucomannan, lactulose, isomalto-oligosaccharides, sorbitol, xylitooligosaccharides, and xylitol, are frequently incorporated into emollient formulations [

57]. Limited knowledge exists regarding the efficacy of topically applied prebiotics, as they are always studied in products with complex formulations. However, they are believed to stimulate the activity of beneficial skin microbiota, thereby suppressing the expansion of pathogenic skin flora, such as

Staphylococcus aureus, among others.

The skin affected by RISI is highly susceptible to UV radiation due to disruptions in the hydrolipid barrier and alterations in the natural skin microbiota [

61].

Staphylococcus epidermidis, for instance, produces 6-N hydroxyaminopurine (6-HAP), which inhibits UV-induced cell proliferation.

Cyanobacteria produce mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) that absorb UV radiation, while

Micrococcus luteus synthesizes an endonuclease that enhances the efficacy of DNA repair enzymes, thereby bolstering the skin's defense against UV-induced damage.

In vitro studies have shown that

Lactobacillus species prevent the development of skin cancers due to the activity of cell wall-embedded lipoteichoic acid (LTA). Moreover, post-RT patients exhibit an elevated risk of developing both melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs). Daily application of sun protection factor (SPF)-containing products is essential for all individuals; however, it is particularly significant for patients receiving RT, as the disrupted hydrolipid barrier and cutaneous microbiota increase sensitivity to UV radiation, necessitating rigorous photoprotection to mitigate potential skin damage [

62,

63].

4.2. Treatment Options and the Skin Microbiome

The management of RISI remains without universally accepted treatment protocols. Despite extensive literature describing treatment modalities, significant disparities exist in clinical practice. The data available for acute RISI (aRISI) is considerably more substantial than that for cRISI, with minimal evidence addressing the appropriate management of cRISI [

55,

64].

Topical glucocorticoids (GCSs) remain the mainstay in the treatment of RISI. They have anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and immunosuppressive effects [

65]. They suppress multiple immune cells, including neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, and skin-resident Langerhans cells, through the inhibition of various pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, TNF-α, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [

65]. On the other hand, topical GCSs disrupt the synthesis of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, leading to the impairment of the hydrolipid barrier [

66]. This results in increased TEWL and compromises the antimicrobial function of the skin barrier. While topical GCS therapy decreases inflammation and the clinical signs of RISI, it can further impair the already damaged skin barrier due to RT. As previously noted, the microbiome in RISI is significantly less diverse, with a predominance of certain opportunistic pathogens. However, even in the absence of clinical signs of skin infection, topical GCSs reduce inflammation and promote healing [

67]. Another study indicates that topical GCSs alone and the addition of topical mupirocin to topical GCSs can reduce

Staphylococcus aureus colonization, resulting in a significant clinical improvement in patients with AD [

68].

The alternative to topical GCSs could be topical calcineurin inhibitors (CI), although it is important to note that these have not yet been extensively studied in RISI and are not included in current consensus statements and recommendations. They appear to be safe in the RT setting and, together with topical GCSs, form a cornerstone of AD treatment [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Experimental studies using rat models of radiotherapy-induced cystitis demonstrated that intravesical administration of tacrolimus exhibited protective effects against this condition [

72]. Furthermore, patients receiving systemic administration of calcineurin inhibitors, such as those undergoing organ transplantation, did not appear to exhibit increased levels of radiotherapy-related toxicities [

73]. Topical CI inhibit the activation of T cells, thereby suppressing the production of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, interferon (IFN)-γ, and TNF-α, with no effect on Th cells and Langerhans cells [

74,

75]. Furthermore, topical pimecrolimus has been observed to reduce involucrin levels, thereby restoring the hydrolipid barrier and reducing the adhesion of

Staphylococcus aureus [

50].

Silver sulfadiazine and silver-containing dressings are frequently utilized in patients with aRISI and clinical signs of infection [

76,

77]. Noteworthy, silver sulfadiazine should not be used for longer than 14 days, as it may slow down re-epithelization [

78]. Silver exerts its antimicrobial activity by binding to bacterial DNA, thereby inhibiting the replication process [

79]. Additionally, silver inhibits the microbial electron transport system and respiration. It has demonstrated efficacy against pathogenic species of bacteria commonly implicated in skin infections, such as

Staphylococcus aureus and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which are also prevalent among RISI patients [

80]. As anticipated, this may also result in bacteriostatic effects on positive, commensal bacteria on the skin. While comprehensive studies on antimicrobial silver-containing agents are lacking, research has explored the impact of silver-thread-enriched clothing on human skin [

81]. Findings indicate that individuals wearing silver-containing clothing exhibit increased bacterial biomass, contradicting expectations given silver's antimicrobial properties. Predominant species identified include

Staphylococcus,

Corynebacterium, and

Cutibacterium, associated with heightened production of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) such as myristoleic acid, contributing to elevated sebum production and skin inflammation [

82]. This investigation suggests that the application of silver-containing agents in RT patients could perturb the natural microbiota of the skin, thereby compromising the integrity of the skin barrier and promoting the proliferation of pathogenic species, leading to RISI exacerbation.

Table 2 summarizes the main treatment options in RISI, as well as their effect on the skin microbiome.

Current recommendations suggest that there is no need to use topical or systemic antibiotics in the absence of clinical signs of infection. However, a recent study by Kost et al. indicated a significant reduction in the risk of RISI following bacterial decolonization of the nose and skin [

83]. The researchers used chlorhexidine, which is known to be allergenic and to damage the skin barrier. Therefore, we propose using sodium hypochlorite baths, which are successfully used in patients with atopic dermatitis and recurrent bacterial skin infections and are currently considered the least aggressive antiseptic [

46,

84,

85]. Hypochlorous acid non-selectively eradicates

Staphylococcus aureus, along with other bacteria, such as

Staphylococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Propionibacterium acnes, fungi, such as

Candida species, and viruses [

85,

86,

87]. Additionally, it exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by reducing the levels of IL-1, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-13, as well as TNF-α. Importantly, it does not significantly affect the TEWL parameter but improves the stratum corneum integrity, thus reinforcing the skin barrier [

85,

88]. Furthermore, it alleviates itching by decreasing the levels of pruritogenic cytokines and inhibiting mast cell degranulation [

89,

90].

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Human skin is home to a vast number of different species of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Its complex microbiome is crucial for proper barrier function, and dysbiosis has been associated with the pathogenesis of numerous skin disorders and diseases. RISI has recently emerged as being characterized by significant alterations in the abundance of certain bacterial species. Given the complex symbiotic and pathomechanistic relationships of the development of RISI, which includes a cascade of immunological processes and damage to the epidermal barrier, it is crucial to further explore the mutual relationship between skin microorganisms before, during, and after RT to provide valuable insights into the dynamics of microbial communities in response to radiation exposure. Importantly, it remains unknown whether microbial cells or their metabolites impact skin cells and surrounding cells like immune, neuronal and other sensory, sweat and other activities. Further research should also explore the long-term effects of irradiation on the destabilization of skin microbiota. In addition, the development of microbiome-based interventions with either probiotics or bacterial metabolites should be a future therapeutic target to prevent and manage RISI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W.B. and A.D.-P.; methodology, A.W.B., P.G. and M.J.; validation, A.W.B., J.K., J.P., A.P., S.J., H.Y., M.M.M. and A.D.-P.; formal analysis, A.W.B.; investigation, A.W.B., P.G., M.J. and A.D.-P.; resources, A.D.-P.; data curation, A.W.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W.B., P.G., M.J., J.K., J.P., A.P., S.J., H.Y., M.M.M. and A.D.-P.; writing—review and editing, A.W.B., P.G., M.J., J.K., J.P., A.P., S.J., H.Y., M.M.M. and A.D.-P.; visualization, A.W.B. and A.D.-P.; supervision, A.D.-P.; project administration, A.D.-P.; funding acquisition, A.D.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Begg, A.C.; Stewart, F.A.; Vens, C. Strategies to improve radiotherapy with targeted drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, G.C.; West, C.M.L.; Dunning, A.M.; Elliott, R.M.; Coles, C.E.; Pharoah, P.D.P.; Burnet, N.G. Normal tissue reactions to radiotherapy: towards tailoring treatment dose by genotype. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilalla, V.; Chaput, G.; Williams, T.; Sultanem, K. Radiotherapy Side Effects: Integrating a Survivorship Clinical Lens to Better Serve Patients. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rübe, C.E.; Freyter, B.M.; Tewary, G.; Roemer, K.; Hecht, M.; Rübe, C. Radiation Dermatitis: Radiation-Induced Effects on the Structural and Immunological Barrier Function of the Epidermis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Woo, H.D.; Kim, Y.J.; Ha, S.W.; Chung, H.W. Delayed Numerical Chromosome Aberrations in Human Fibroblasts by Low Dose of Radiation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2015, 12, 15162–15172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnegan, P.; Kiely, L.; Gallagher, C.; Mhaolcatha, S.N.; Feeley, L.; Fitzgibbon, J.; et al. Radiation-induced morphea of the breast-A case series. Skin Health Dis. 2023, 3, e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Alavi, A.; Wong, R.; Akita, S. Radiodermatitis: A Review of Our Current Understanding. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2016, 17, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behroozian, T.; Milton, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, L.; Lou, J.; Karam, I.; Wronski, M.; McKenzie, E.; Mawdsley, G.; Razvi, Y.; et al. Predictive factors associated with radiation dermatitis in breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 28, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of risk factors related to acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients during radiotherapy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2022, 18, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thariat, J.; Hannoun-Levi, J.-M.; Myint, A.S.; Vuong, T.; Gérard, J.-P. Past, present, and future of radiotherapy for the benefit of patients. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 10, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Meng, L.; Hou, X.; Qu, C.; Wang, B.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Radiation-induced skin reactions: mechanism and treatment. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, ume 11, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, M.R.; Shen, A.H.; Lee, G.K.; Momeni, A.; Longaker, M.T.; Wan, D.C. Radiation-Induced Skin Fibrosis: Pathogenesis, Current Treatment Options, and Emerging Therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019, 83, S59–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdrowski, J.; Polaſska, A.; Kaźmierska, J.; Barczak, W.; Szewczyk, M.; Adamski, Z.; Żaba, R.; Golusiſski, P.; Golusiſski, W.; Daſczak-Pazdrowska, A. Skin barrier function in patients under radiation therapy due to the head and neck cancers - Preliminary study. Rep. Pr. Oncol. Radiother. 2019, 24, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdrowski, J.; Polańska, A.; Kaźmierska, J.; Kowalczyk, M.J.; Szewczyk, M.; Niewinski, P.; Golusiński, W.; Dańczak-Pazdrowska, A. The Assessment of the Long-Term Impact of Radiotherapy on Biophysical Skin Properties in Patients after Head and Neck Cancer. Medicina 2024, 60, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.L.; Drake, D.R.; Dawson, D.V.; Blanchette, D.R.; Brogden, K.A.; Wertz, P.W. Antibacterial Activity of Sphingoid Bases and Fatty Acids against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaney, M.H.; Nelsen, A.; Sandstrom, S.; Kalan, L.R. Sweat and Sebum Preferences of the Human Skin Microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0418022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, M.; Hetta, H.F.; Saleh, M.M.; Ali, M.E.; Ahmed, A.A.; Salah, M. Alterations in skin microbiome mediated by radiotherapy and their potential roles in the prognosis of radiotherapy-induced dermatitis: a pilot study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, K.; Bauza-Kaszewska, J.; Kraszewska, Z.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Kwiecińska-Piróg, J.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Radtke, L.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Human Skin Microbiome: Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors on Skin Microbiota. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundell, A.M. Microbial Ecology of the Human Skin. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 76, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Lekkala, L.; Yadav, D.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Microbiome and Postbiotics in Skin Health. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Kong, H.H.; Conlan, S.; Deming, C.B.; Davis, J.; Young, A.C.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Bouffard, G. G.; Blakesley, R.W.; Murray, P.R.; et al. Topographical and Temporal Diversity of the Human Skin Microbiome. Science 2009, 324, 1190–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Cruz, S.; Orozco-Covarrubias, L.; Sáez-De-Ocariz, M. The Human Skin Microbiome in Selected Cutaneous Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 834135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prohic, A.; Sadikovic, T.J.; Krupalija-Fazlic, M.; Kuskunovic-Vlahovljak, S. Malasseziaspecies in healthy skin and in dermatological conditions. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015, 55, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forton FMN, De Maertelaer V. Which factors influence Demodex proliferation? A retrospective pilot study highlighting a possible role of subtle immune variations and sebaceous gland status. J Dermatol. 2021;48(8):1210-20.

- Graham, E.H.; Tom, W.A.; Neujahr, A.C.; Adamowicz, M.S.; Clarke, J.L.; Herr, J.R.; Fernando, S.C. The persistence and stabilization of auxiliary genes in the human skin virome. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, J.S.; Sfyroera, G.; Bartow-McKenney, C.; Gimblet, C.; Bugayev, J.; Horwinski, J.; Kim, B.; Brestoff, J.R.; Tyldsley, A.S.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Commensal microbiota modulate gene expression in the skin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Hunt, R.L.; Villaruz, A.E.; Fisher, E.L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Q.; Cheung, G.Y.; Li, M.; Otto, M. Commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis contributes to skin barrier homeostasis by generating protective ceramides. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 301–313.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberoi, A.; Bartow-McKenney, C.; Zheng, Q.; Flowers, L.; Campbell, A.; Knight, S.A.; Chan, N.; Wei, M.; Lovins, V.; Bugayev, J.; et al. Commensal microbiota regulates skin barrier function and repair via signaling through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1235–1248.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudiero, O.; Brancaccio, M.; Mennitti, C.; Laneri, S.; Lombardo, B.; De Biasi, M.G.; De Gregorio, E.; Pagliuca, C.; Colicchio, R.; Salvatore, P.; et al. Human Defensins: A Novel Approach in the Fight against Skin Colonizing Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.V.; Soulika, A.M. The Dynamics of the Skin’s Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastar, I.; O’neill, K.; Padula, L.; Head, C.R.; Burgess, J.L.; Chen, V.; Garcia, D.; Stojadinovic, O.; Hower, S.; Plano, G.V.; et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis Boosts Innate Immune Response by Activation of Gamma Delta T Cells and Induction of Perforin-2 in Human Skin. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharschmidt, T.C.; Vasquez, K.S.; Truong, H.-A.; Gearty, S.V.; Pauli, M.L.; Nosbaum, A.; Gratz, I.K.; Otto, M.; Moon, J.J.; Liese, J.; et al. A Wave of Regulatory T Cells into Neonatal Skin Mediates Tolerance to Commensal Microbes. Immunity 2015, 43, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leech, J.M.; Dhariwala, M.O.; Lowe, M.M.; Chu, K.; Merana, G.R.; Cornuot, C.; Weckel, A.; Ma, J.M.; Leitner, E.G.; Gonzalez, J.R.; et al. Toxin-Triggered Interleukin-1 Receptor Signaling Enables Early-Life Discrimination of Pathogenic versus Commensal Skin Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 795–809.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.; Bouladoux, N.; Linehan, J.L.; Han, S.-J.; Harrison, O.J.; Wilhelm, C.; Conlan, S.; Himmelfarb, S.; Byrd, A.L.; Deming, C.; et al. Commensal–dendritic-cell interaction specifies a unique protective skin immune signature. Nature 2015, 520, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamoutounour, S.; Han, S.-J.; Deckers, J.; Constantinides, M.G.; Hurabielle, C.; Harrison, O.J.; Bouladoux, N.; Linehan, J.L.; Link, V.M.; Vujkovic-Cvijin, I.; et al. Keratinocyte-intrinsic MHCII expression controls microbiota-induced Th1 cell responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 23643–23652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, J.L.; Harrison, O.J.; Han, S.-J.; Byrd, A.L.; Vujkovic-Cvijin, I.; Villarino, A.V.; Sen, S.K.; Shaik, J.; Smelkinson, M.; Tamoutounour, S.; et al. Non-classical Immunity Controls Microbiota Impact on Skin Immunity and Tissue Repair. Cell 2018, 172, 784–796.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford JA, O'Neill AM, Zouboulis CC, Gallo RL. Short-Chain Fatty Acids from. J Immunol. 2019;202(6):1767-76.

- Chen, Y.; Knight, R.; Gallo, R.L. Evolving approaches to profiling the microbiome in skin disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; An, L.; Su, W.; Yan, T.; Zhang, H.; Yu, D.-J. Exploring the alterations and function of skin microbiome mediated by ionizing radiation injury. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, L.; Yu, X. Skin Microbiome Composition is Associated with Radiation Dermatitis in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiation after Reconstructive Surgery: A Prospective, Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 117, e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülpüsch, C.; Neumann, A.U.; Reiger, M.; Fischer, J.C.; de Tomassi, A.; Hammel, G.; Gülzow, C.; Fleming, M.; Dapper, H.; Mayinger, M.; et al. Association of Skin Microbiome Dynamics With Radiodermatitis in Patients With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamae, N.; Ogai, K.; Kunimitsu, M.; Fujiwara, M.; Nagai, M.; Okamoto, S.; Okuwa, M.; Oe, M. Relationship between severe radiodermatitis and skin barrier functions in patients with head and neck cancer: A prospective observational study. Asia-Pacific J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 12, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, Y.; Rzepecki, A.K.; Deutsch, A.; Birnbaum, M.R.; Ohri, N.; Hosgood, H.D.; Lin, J.; Daily, J.P.; Shinoda, K.; McLellan, B.N. Association of Staphylococcus aureus Colonization With Severity of Acute Radiation Dermatitis in Patients With Breast or Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spałek, M. Chronic radiation-induced dermatitis: challenges and solutions. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, ume 9, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Wu, Q.; Qiang, W. What is the appropriate skin cleaning method for nasopharyngeal cancer radiotherapy patients? A randomized controlled trial. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 3875–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollenberg, A.; Christen-Zäch, S.; Taieb, A.; Paul, C.; Thyssen, J.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Vestergaard, C.; Seneschal, J.; Werfel, T.; Cork, M.; et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2717–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynde, C.W.; Andriessen, A.; Bertucci, V.; McCuaig, C.; Skotnicki, S.; Weinstein, M.; Wiseman, M.; Zip, C. The Skin Microbiome in Atopic Dermatitis and Its Relationship to Emollients. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2015, 20, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri, M.; Lotti, R.; Bonzano, L.; Ciardo, S.; Guanti, M.B.; Pellacani, G.; Pincelli, C.; Marconi, A. A Novel Multi-Action Emollient Plus Cream Improves Skin Barrier Function in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: In vitro and Clinical Evidence. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2021, 34, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, P.; Theunis, J.; Casas, C.; Villeneuve, C.; Patrizi, A.; Phulpin, C.; Bacquey, A.; Redoulès, D.; Mengeaud, V.; Schmitt, A. Effects of a New Emollient-Based Treatment on Skin Microflora Balance and Barrier Function in Children with Mild Atopic Dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2016, 33, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.M.; Scherer, A.; Wanke, C.; Bräutigam, M.; Bongiovanni, S.; Letzkus, M.; Staedtler, F.; Kehren, J.; Zuehlsdorf, M.; Schwarz, T.; et al. Gene expression is differently affected by pimecrolimus and betamethasone in lesional skin of atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2011, 67, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, N.; Vlasova, I.; Skowrońska, W.; Bazylko, A.; Piwowarski, J.P.; Granica, S. Current Knowledge on Interactions of Plant Materials Traditionally Used in Skin Diseases in Poland and Ukraine with Human Skin Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daré, R.G.; Nakamura, C.V.; Ximenes, V.F.; Lautenschlager, S.O. Tannic acid, a promising anti-photoaging agent: Evidences of its antioxidant and anti-wrinkle potentials, and its ability to prevent photodamage and MMP-1 expression in L929 fibroblasts exposed to UVB. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman MM, Rahaman MS, Islam MR, Hossain ME, Mannan Mithi F, Ahmed M, et al. Multifunctional Therapeutic Potential of Phytocomplexes and Natural Extracts for Antimicrobial Properties. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(9).

- Villanueva, X.; Zhen, L.; Ares, J.N.; Vackier, T.; Lange, H.; Crestini, C.; Steenackers, H.P. Effect of chemical modifications of tannins on their antimicrobial and antibiofilm effect against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 987164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behroozian, T.; Goldshtein, D.; Wolf, J.R.; Hurk, C.v.D.; Finkelstein, S.; Lam, H.; Patel, P.; Kanee, L.; Lee, S.F.; Chan, A.W.; et al. MASCC clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of acute radiation dermatitis: part 1) systematic review. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 58, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, E. Contact sensitization from Compositae-containing herbal remedies and cosmetics. Contact Dermat. 2002, 47, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazzewi, F.H.; Tester, R.F. Impact of prebiotics and probiotics on skin health. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guéniche, A.; Bastien, P.; Ovigne, J.M.; Kermici, M.; Courchay, G.; Chevalier, V.; Breton, L.; Castiel-Higounenc, I. Bifidobacterium longum lysate, a new ingredient for reactive skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahe YF, Perez MJ, Tacheau C, Fanchon C, Martin R, Rousset F, et al. A new Vitreoscilla filiformis extract grown on spa water-enriched medium activates endogenous cutaneous antioxidant and antimicrobial defenses through a potential Toll-like receptor 2/protein kinase C, zeta transduction pathway. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:191-6.

- Kircik, L.H. Effect of skin barrier emulsion cream vs a conventional moisturizer on transepidermal water loss and corneometry in atopic dermatitis: a pilot study. . 2014, 13, 1482–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Souak, D.; Barreau, M.; Courtois, A.; André, V.; Poc, C.D.; Feuilloley, M.G.J.; Gault, M. Challenging Cosmetic Innovation: The Skin Microbiota and Probiotics Protect the Skin from UV-Induced Damage. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.J.; Eid, E.; Tang, J.Y.; Kurian, A.W.; Kwong, B.Y.; Linos, E. Incidence of Nonkeratinocyte Skin Cancer After Breast Cancer Radiation Therapy. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e241632–e241632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, M.D.; Karagas, M.R.; Mott, L.A.; Spencer, S.K.; Stukel, T.A.; Greenberg, E.R. Therapeutic Ionizing Radiation and the Incidence of Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. 2000, 136, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.N.; Shah, R.; Menzer, C.; Aleisa, A.; Sun, M.D.; Kwong, B.Y.; Kaffenberger, B.H.; Seminario-Vidal, L.; Barker, C.A.; Stubblefield, M.D.; et al. Consensus on the clinical management of chronic radiation dermatitis and radiation fibrosis: a Delphi survey. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelc, J.; Czarnecka-Operacz, M.; Adamski, Z. The structure and function of the epidermal barrier in patients with atopic dermatitis – treatment options. Part two. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2018, 35, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAleer, M.A.; Jakasa, I.; Stefanovic, N.; McLean, W.H.I.; Kezic, S.; Irvine, A.D. Topical corticosteroids normalize both skin and systemic inflammatory markers in infant atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 185, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosanquet, D.; Rangaraj, A.; Richards, A.; Riddell, A.; Saravolac, V.; Harding, K. Topical steroids for chronic wounds displaying abnormal inflammation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 95, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Lin, L.; Lin, T.; Hao, F.; Zeng, F.; Bi, Z.; Yi, D.; Zhao, B. Skin colonization byStaphylococcus aureusin patients with eczema and atopic dermatitis and relevant combined topical therapy: a double-blind multicentre randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 155, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abędź N, Pawliczak R. Efficacy and safety of topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2019;36(6):752-9.

- Chu, C.-H.; Cheng, Y.-P.; Liang, C.-W.; Chiu, H.-C.; Jee, S.-H.; Chan, J.-Y.L.; Yu, Y. Radiation recall dermatitis induced by topical tacrolimus for post-irradiation morphea. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 31, e80–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerche, C.M.; Philipsen, P.A.; Poulsen, T.; Wulf, H.C. Topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus do not accelerate photocarcinogenesis in hairless mice after UVA or simulated solar radiation. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaganapathy, B.R.; Janicki, J.J.; Levanovich, P.; Tyagi, P.; Hafron, J.; Chancellor, M.B.; Krueger, S.; Marples, B. Intravesical Liposomal Tacrolimus Protects against Radiation Cystitis Induced by 3-Beam Targeted Bladder Radiation. J. Urol. 2015, 194, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotta, V.; D'Aviero, A.; Fionda, B.; Casà, C.; Esposito, I.; Preziosi, F.; Acampora, A.; Marazzi, F.; Kovács, G.; Jereczek-Fossa, B.A.; et al. Immunosuppressive treatment and radiotherapy in kidney transplant patients: A systematic review. World J. Radiol. 2022, 14, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, W.W. Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors for Atopic Dermatitis: Review and Treatment Recommendations. Pediatr. Drugs 2013, 15, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuetz, A.; Baumann, K.; Grassberger, M.; Wolff, K.; Meingassner, J.G. Discovery of Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors and Pharmacological Profile of Pimecrolimus. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2006, 141, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Kanee, L.; Behroozian, T.; Wolf, J.R.; Hurk, C.v.D.; Chow, E.; Bonomo, P. Comparison of clinical practice guidelines on radiation dermatitis: a narrative review. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4663–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zasadziński, K.; Spałek, M.J.; Rutkowski, P. Modern Dressings in Prevention and Therapy of Acute and Chronic Radiation Dermatitis—A Literature Review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.; Dissemond, J.; Kim, S.; Willy, C.; Mayer, D.; Papke, R.; Tuchmann, F.; Assadian, O. Consensus on Wound Antisepsis: Update 2018. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2017, 31, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, D.E.; Barillo, D.J. Silver in medicine: The basic science. Burns 2014, 40, S9–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, E.G.; De Angelis, B.; Cavallo, I.; Sivori, F.; Orlandi, F.; D’autilio, M.F.L.M.; Di Segni, C.; Gentile, P.; Scioli, M.G.; Orlandi, A.; et al. Silver Sulfadiazine Eradicates Antibiotic-Tolerant Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms in Patients with Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, A.V.; Callewaert, C.; Dorrestein, K.; Broadhead, R.; Minich, J.J.; Ernst, M.; Humphrey, G.; Ackermann, G.; Gathercole, R.; Aksenov, A.A.; et al. The Molecular Effect of Wearing Silver-Threaded Clothing on the Human Skin. mSystems 2023, 8, e0092222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-S.; Liang, S.; Zong, M.-H.; Yang, J.-G.; Lou, W.-Y. Microbial synthesis of functional odd-chain fatty acids: a review. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost Y, Deutsch A, Mieczkowska K, Nazarian R, Muskat A, Hosgood HD, et al. Bacterial Decolonization for Prevention of Radiation Dermatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(7):940-5.

- García-Valdivia, M.; Quiñones-Vico, M.I.; Ortega-Llamas, L.; Fernández-González, A.; Ubago-Rodríguez, A.; la Torre, R.S.-D.; Arias-Santiago, S. Cytotoxicity, Epidermal Barrier Function and Cytokine Evaluation after Antiseptic Treatment in Bioengineered Autologous Skin Substitute. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarouf, M.; Shi, V.Y. Bleach for Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatitis® 2018, 29, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.E.; Schaffer, J.V.; Orlow, S.J.; Gao, Z.; Li, H.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Blaser, M.J. Cutaneous microbiome effects of fluticasone propionate cream and adjunctive bleach baths in childhood atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 481–493.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, A.G.; Rong, A.; Miller, D.; Tran, A.Q.; Head, T.; Lee, M.C.; Lee, W.W. 0.01% Hypochlorous Acid as an Alternative Skin Antiseptic: An In Vitro Comparison. Dermatol. Surg. 2018, 44, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolarczyk, A.; Perez-Nazario, N.; Knowlden, S.A.; Chinchilli, E.; Grier, A.; Paller, A.; Gill, S.R.; De Benedetto, A.; Yoshida, T.; Beck, L.A. Bleach baths enhance skin barrier, reduce itch but do not normalize skin dysbiosis in atopic dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2023, 315, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rosso, J.Q.; Bhatia, N. Status Report on Topical Hypochlorous Acid: Clinical Relevance of Specific Formulations, Potential Modes of Action, and Study Outcomes. . 2018, 11, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, T.; Martel, B.C.; Linder, K.E.; Ehling, S.; Ganchingco, J.R.; Bäumer, W. Hypochlorous acid is antipruritic and anti-inflammatory in a mouse model of atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2017, 48, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).