Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

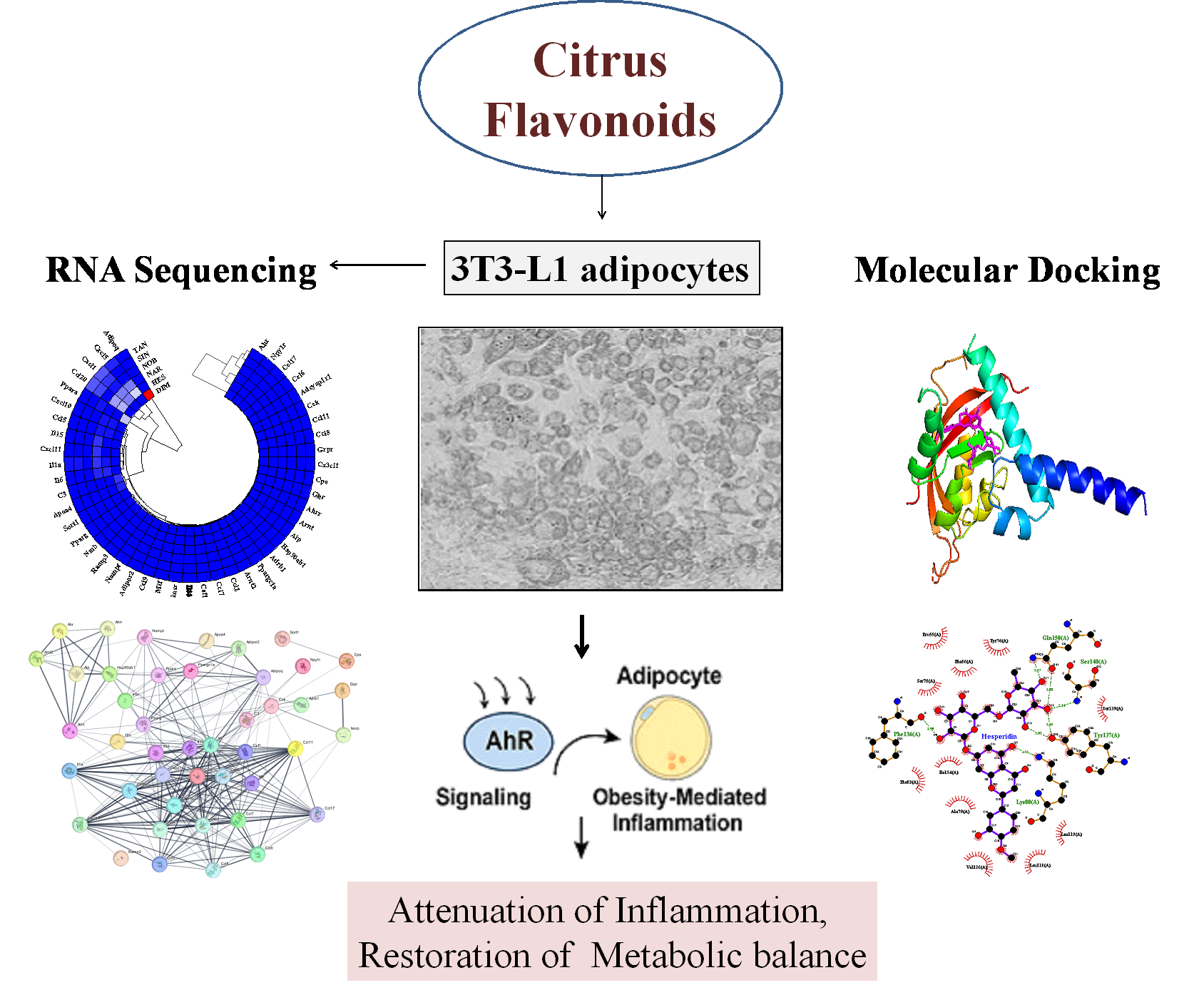

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

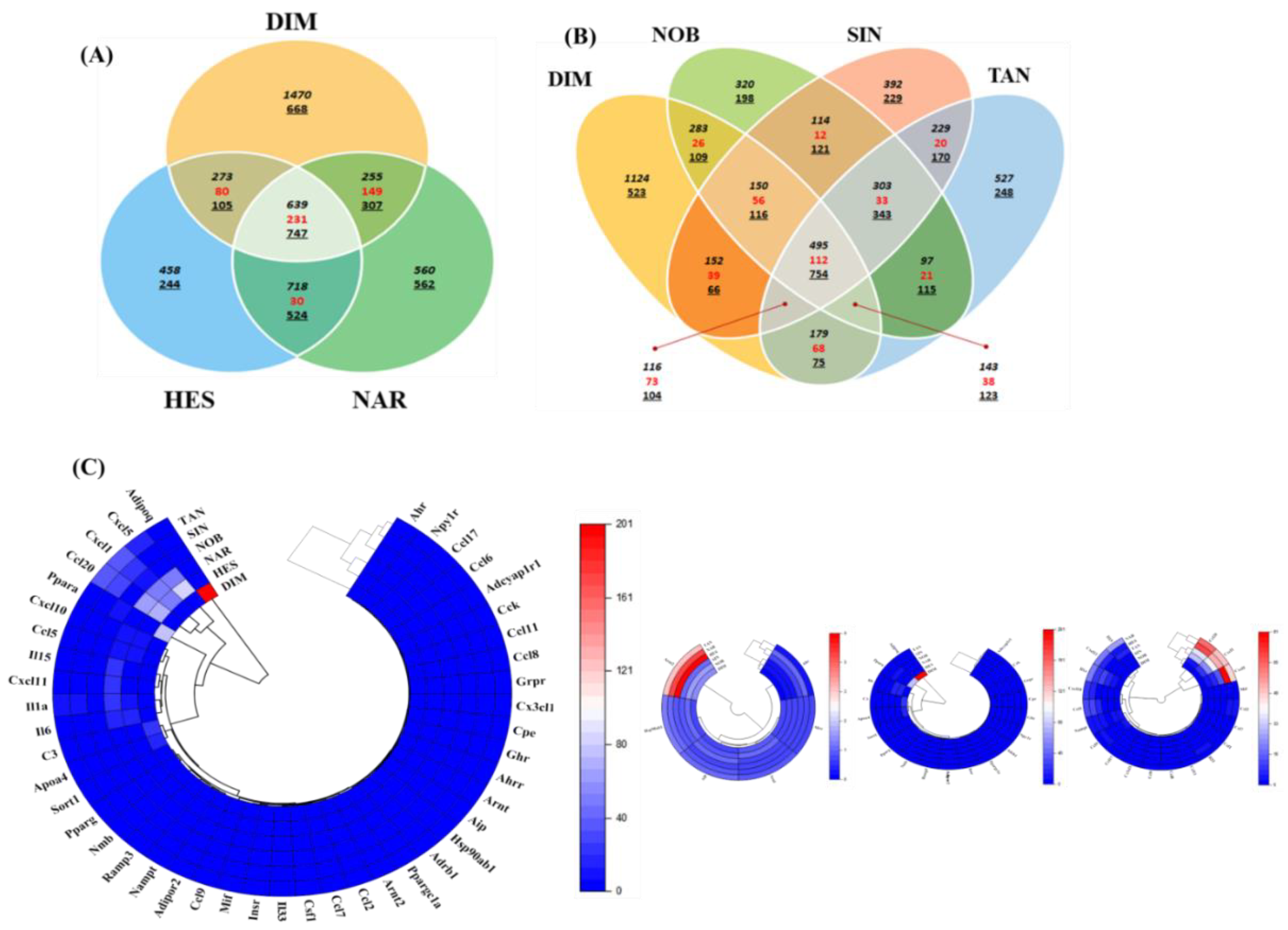

2.1. Differentially Expressed Genes in Flavonoid-Treated 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

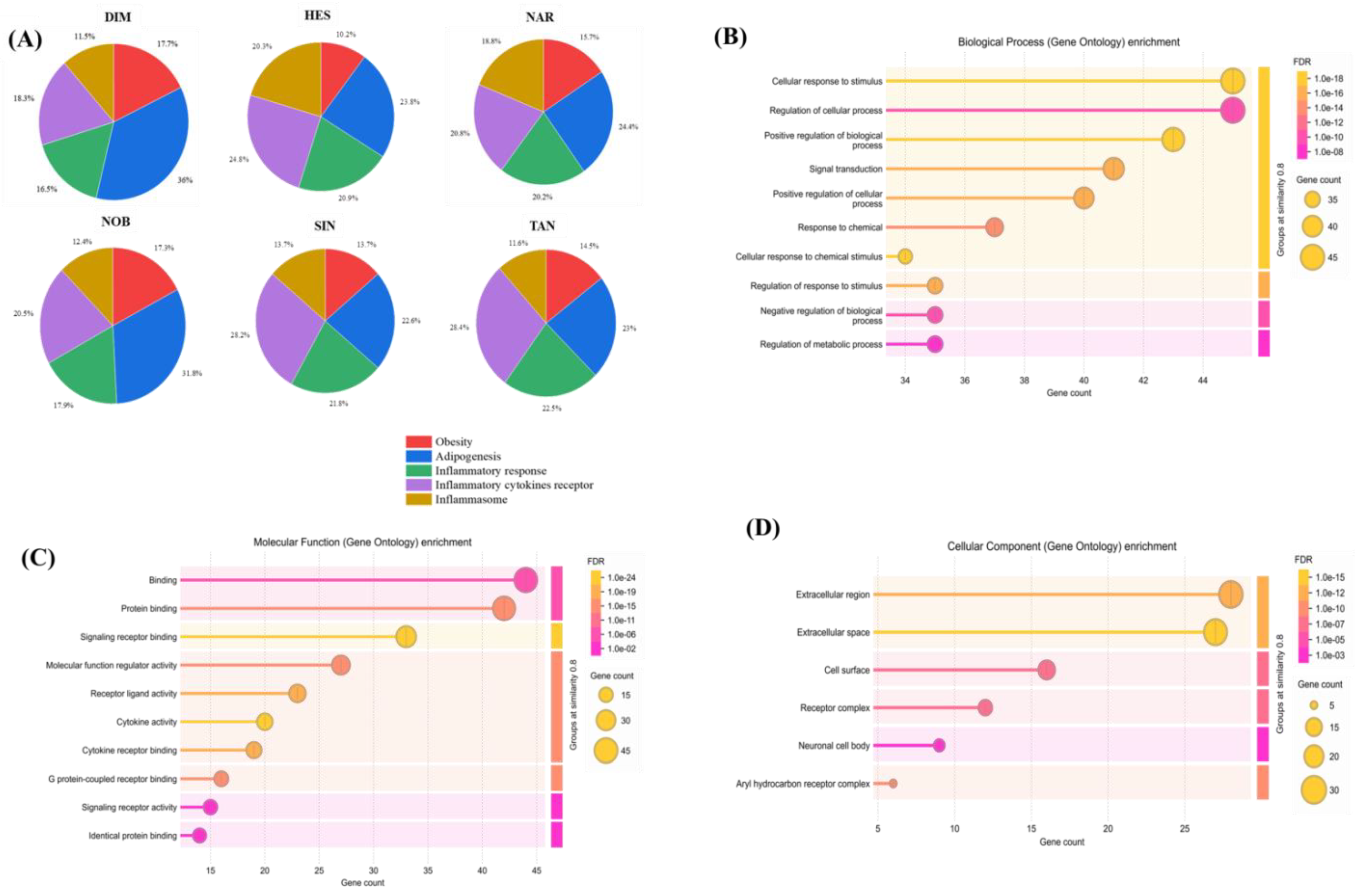

2.2. Gene Ontology Analysis

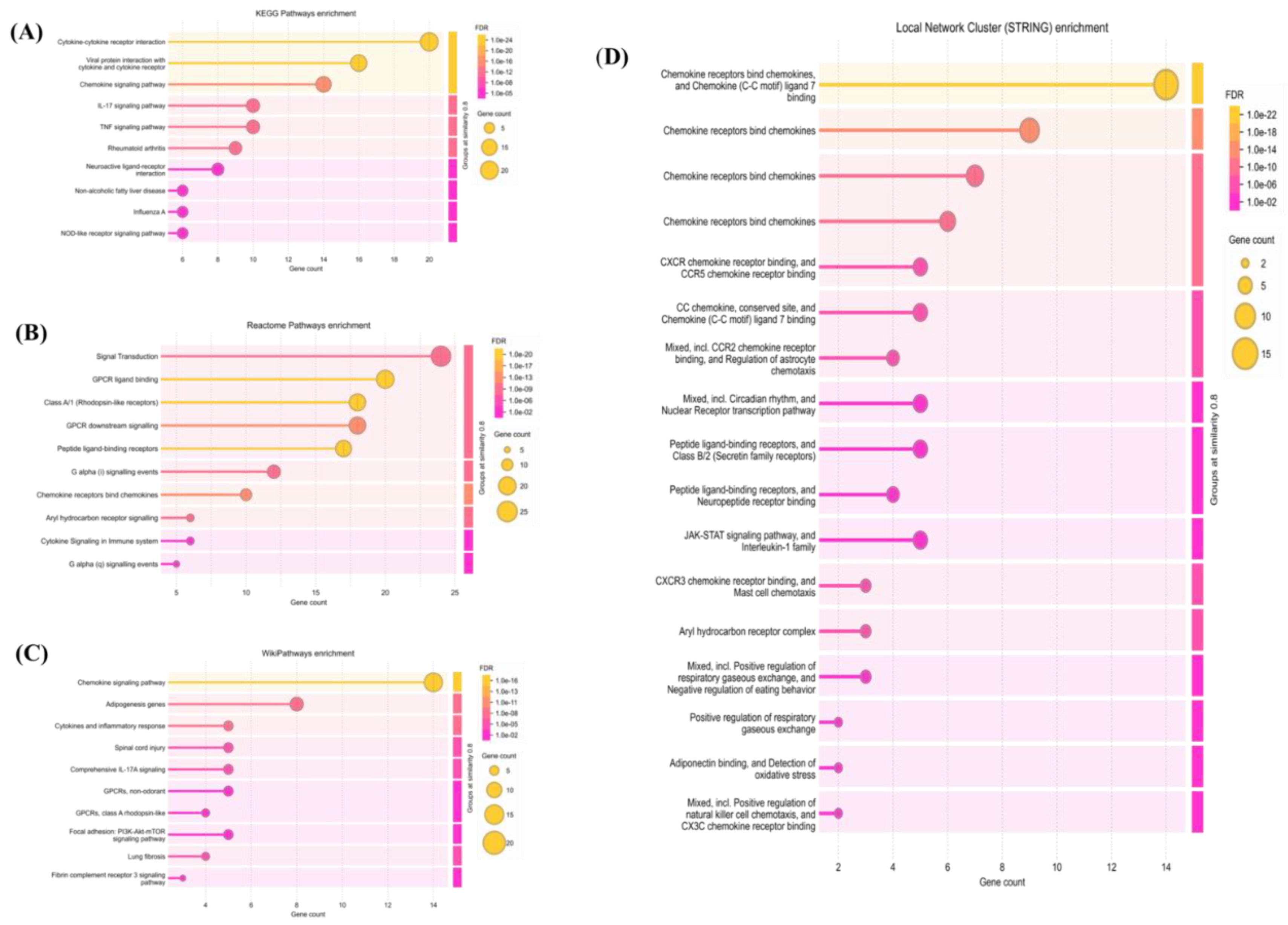

2.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.4. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis

2.5. Molecular Docking Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. 3T3-L1 Cell Culture and Differentiation

4.3. RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

4.4. Gene Ontology and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.5. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Analysis

4.6. Molecular Docking Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AhR | Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DIM | Differentiated adipocyte model |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| HES | Hesperidin |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| NAR | Narirutin |

| NOB | Nobiletin |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| SAhRMs | Selective AhR modulators |

| SIN | Sinensetin |

| STRING | Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| TAN | Tangeretin |

References

- Xu, C.X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.M.; Jaeger, C.D.; Krager, S.L.; Bottum, K.M.; Liu, J.; Liao, D.F.; Tischkau, S.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor deficiency protects mice from diet-induced adiposity and metabolic disorders through increased energy expenditure. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015, 39, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, K.W. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), integrating energy metabolism and microbial or obesity-mediated inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol 2021, 184, 114346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beischlag, T.V.; Luis Morales, J.; Hollingshead, B.D.; Perdew, G.H. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2008, 18, 207–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Feng, Y.; Fu, H.; Xie, H.Q.; Jiang, J.X.; Zhao, B. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: A Key Bridging Molecule of External and Internal Chemical Signals. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49, 9518–9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnieri, T.; Abruzzo, P.M.; Bolotta, A. More than a cell biosensor: aryl hydrocarbon receptor at the intersection of physiology and inflammation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020, 318, C1078–C1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lin, L.; Xie, N.; Chen, W.; Nong, W.; Li, R. Role of aryl hydrocarbon receptors in infection and inflammation. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1367734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, R.; McGaha, T.L. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: Connecting Immunity to the Microenvironment. Trends Immunol 2018, 39, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothhammer, V.; Quintana, F.J. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: an environmental sensor integrating immune responses in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, P.; Kahar, P.; Patel, B.M. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus 2022, 14, e22711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, N.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Piette, J.; Scheen, A.J.; Paquot, N. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014, 105, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wu, B.; Xiao, H.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Xu, X.; Li, T. Signaling pathways in obesity: mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Wang, H.; Liang, F. Mechanisms Linking Inflammation to Insulin Resistance. Int J Endocrinol 2015, 2015, 508409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatterale, F.; Longo, M.; Naderi, J.; Raciti, G.A.; Desiderio, A.; Miele, C.; Beguinot, F. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavakis, T.; Alexaki, V.I.; Ferrante, A.W., Jr. Macrophage function in adipose tissue homeostasis and metabolic inflammation. Nat Immunol 2023, 24, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Chang, K.; Wu, W.; Griffiths, H.R.; Lu, S.; Gao, D. Adipose tissue macrophages as potential targets for obesity and metabolic diseases. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1153915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, M.; Agrawal, S.; Agrawal, A.; Dubey, G.P. Metaflammatory responses during obesity: Pathomechanism and treatment. Obes Res Clin Pract 2016, 10, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, L.; Yu, R.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Proud, C.G.; Jiang, T. Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 2403–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, I.A.; Perdew, G.H. How Ah Receptor Ligand Specificity Became Important in Understanding Its Physiological Function. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, K.W. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) functions: Balancing opposing processes including inflammatory reactions. Biochem Pharmacol 2020, 178, 114093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhiz, H.; Roohbakhsh, A.; Soltani, F.; Rezaee, R.; Iranshahi, M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of the citrus flavonoids hesperidin and hesperetin: an updated review of their molecular mechanisms and experimental models. Phytother Res 2015, 29, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavente-García, O.; Castillo, J.; Marin, F.R.; Ortuño, A.; Del Río, J.A. Uses and properties of citrus flavonoids. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 1997, 45, 4505–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natraj, P.; Rajan, P.; Jeon, Y.A.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, Y.J. Antiadipogenic effect of citrus flavonoids: Evidence from RNA sequencing analysis and activation of AMPK in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2023, 71, 17788–17800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, P.; Natraj, P.; Ranaweera, S.S.; Dayarathne, L.A.; Lee, Y.J.; Han, C.-H. Anti-adipogenic effect of the flavonoids through the activation of AMPK in palmitate (PA)-treated HepG2 cells. Journal of Veterinary Science 2021, 23, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohjanvirta, R. AHR in energy balance regulation. Current Opinion in Toxicology 2017, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, U.-H.; Park, H.; Li, X.; Davidson, L.A.; Allred, C.; Patil, B.; Jayaprakasha, G.; Orr, A.A.; Mao, L.; Chapkin, R.S. Structure-dependent modulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated activities by flavonoids. Toxicological Sciences 2018, 164, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungsu, I.; Kifli, N.; Ahmad, S.R.; Ghani, H.; Cunningham, A.C. Herbal Plants: The Role of AhR in Mediating Immunomodulation. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 697663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya-Jorge, E.; Jorge Rodriguez, M.E.; Veitia, M.S.; Giner, R.M. Plant Occurring Flavonoids as Modulators of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Q.; Di, Q.; Song, Y.; Li, P.; Gong, Y. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) regulates adipocyte differentiation by assembling CRL4B ubiquitin ligase to target PPARgamma for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 18504–18515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cui, Y.; Gao, X.; Wei, C.; Wang, Q.; Yang, B.; Sun, W.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, Y. Resveratrol inhibits the formation and accumulation of lipid droplets through AdipoQ signal pathway and lipid metabolism lncRNAs. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2023, 117, 109351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.E.; Beilby, J.; Cadby, G.; Warrington, N.M.; Bruce, D.G.; Davis, W.A.; Davis, T.M.; Wiltshire, S.; Knuiman, M.; McQuillan, B.M. A comprehensive investigation of variants in genes encoding adiponectin (ADIPOQ) and its receptors (ADIPOR1/R2), and their association with serum adiponectin, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. BMC Medical Genetics 2013, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Z.; Wu, H.; Song, K.K.; Zhao, H.H.; Tang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Wang, D.; Dong, S.L.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; et al. Transcriptome analysis revealed enrichment pathways and regulation of gene expression associated with somatic embryogenesis in Camellia sinensis. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 15946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Weng, D.; Zhou, F.; Owen, Y.D.; Qin, H.; Zhao, J.; Wen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Fu, H.; et al. Activation of PPARgamma by a Natural Flavonoid Modulator, Apigenin Ameliorates Obesity-Related Inflammation Via Regulation of Macrophage Polarization. EBioMedicine 2016, 9, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, M.; Wang, Z.; Lara, B.; Fimbres, J.; Pichardo, T.; Mazzilli, S.; Khan, M.M.; Duggineni, V.K.; Monti, S.; Sherr, D.H. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor controls IFN-γ-induced immune checkpoints PD-L1 and IDO via the JAK/STAT pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. The Journal of Immunology 2025, 214, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, Y.; Kado, S.Y.; Bein, K.J.; He, Y.; Pouraryan, A.A.; Urban, A.; Haarmann-Stemmann, T.; Sweeney, C.; Vogel, C.F. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling synergizes with TLR/NF-κB-signaling for induction of IL-22 through canonical and non-canonical AhR pathways. Frontiers in toxicology 2022, 3, 787360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, A.S.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Targeting AhR as a Novel Therapeutic Modality against Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Chen, D.; Zhu, W.; Sun, C. Pharmacological Effects of Polyphenol Phytochemicals on the JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 716672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, K.W. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)-mediated inflammation and resolution: Non-genomic and genomic signaling. Biochemical pharmacology 2020, 182, 114220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Da Rocha, G.H.; Müller, C.; Przybylski-Wartner, S.; Schaller, H.; Riemschneider, S.; Lehmann, J. P0145 Role of PPARg on anti-inflammatory effects mediated by AhR ligands in a Caco-2/THP-1 in vitro “inflamed gut” model. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2025, 19, i535–i535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Wang, L. Identification of key genes and their association with immune infiltration in adipose tissue of obese patients: a bioinformatic analysis. Adipocyte 2022, 11, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mijiti, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a prognostic biomarker and is correlated with immune responses in cervical cancer. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 11922–11935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; You, L.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H. Docking and 3D-QSAR studies on the Ah receptor binding affinities of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) and dibenzofurans (PCDFs). Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 2011, 32, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.X.; Li, X.; Deng, S.Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Deng, X.; Han, B.; Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.Z.; et al. Urolithin A ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by targeting aryl hydrocarbon receptor. EBioMedicine 2021, 64, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safe, S.; Jin, U.H.; Park, H.; Chapkin, R.S.; Jayaraman, A. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR) Ligands as Selective AHR Modulators (SAhRMs). Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosa, F.E.; El-Kadi, A.O.; Barakat, K. Targeting the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR): a review of the in-silico screening approaches to identify AhR modulators. High-Throughput Screening for Drug Discovery 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, S.C.; Giani Tagliabue, S.; Bonati, L.; Denison, M.S. The cellular and molecular determinants of naphthoquinone-dependent activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | DIM | HES | NAR | NOB | SIN | TAN | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahr | 0.416 | 0.988 | 1.214 | 0.537 | 0.582 | 0.568 | aryl-hydrocarbon receptor |

| Ahrr | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | aryl-hydrocarbon receptor repressor |

| Aip | 0.955 | 0.961 | 1.033 | 1.061 | 1.2 | 1.139 | aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein |

| Arnt | 1.102 | 0.973 | 0.936 | 1.194 | 1.004 | 1.048 | aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator |

| Arnt2 | 1.439 | 4.046 | 3.471 | 1.559 | 1.248 | 2.681 | aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 2 |

| Hsp90ab1 | 0.975 | 1.126 | 1.232 | 1.174 | 1.072 | 1.267 | heat shock protein 90 alpha (cytosolic), class B member 1 |

| Gene | DIM | HES | NAR | NOB | SIN | TAN | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adcyap1r1 | 0.557 | 0.071 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.106 | 0.044 | adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 receptor 1 |

| Adipoq | 200.049 | 0.186 | 0.406 | 2.73 | 0.055 | 0.18 | adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing |

| Adipor2 | 5.596 | 3.039 | 3.764 | 3.79 | 3.004 | 2.828 | adiponectin receptor 2 |

| Adrb1 | 2.375 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.418 | 0.156 | 0.668 | adrenergic receptor, beta 1 |

| Apoa4 | 19.218 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.95 | 1.096 | 1.116 | apolipoprotein A-IV |

| C3 | 20.91 | 5.389 | 4.011 | 1.479 | 1.001 | 1.255 | complement component 3 |

| Cck | 0.191 | 0.377 | 0.057 | 0.099 | 0.06 | 0.4 | cholecystokinin |

| Cpe | 0.313 | 0.473 | 0.453 | 0.916 | 0.512 | 0.55 | carboxypeptidase E |

| Ghr | 0.487 | 0.536 | 0.467 | 0.478 | 0.403 | 0.309 | growth hormone receptor |

| Grpr | 0.341 | 0.815 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.327 | 0.203 | gastrin releasing peptide receptor |

| IL-6 | 1.127 | 16.345 | 19.068 | 4.612 | 1.994 | 6.532 | interleukin 6 |

| Insr | 1.82 | 1.551 | 1.83 | 2.045 | 1.574 | 1.553 | insulin receptor |

| Nmb | 2.361 | 1.803 | 3.986 | 6.027 | 2.739 | 2.124 | neuromedin B |

| Npy1r | 0.288 | 1.422 | 0.835 | 0.309 | 0.371 | 0.383 | neuropeptide Y receptor Y1 |

| Ppara | 78.683 | 0.597 | 0.597 | 8.704 | 0.703 | 1.47 | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha |

| Pparg | 5.735 | 0.681 | 0.492 | 2.228 | 1.033 | 1.085 | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma |

| Ppargc1a | 2.11 | 0.118 | 0.113 | 1.707 | 0.701 | 0.582 | peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 alpha |

| Ramp3 | 4.255 | 1.803 | 2.387 | 4.022 | 4.775 | 2.48 | receptor (calcitonin) activity modifying protein 3 |

| Sort1 | 6.212 | 0.633 | 0.461 | 4.361 | 0.716 | 0.627 | sortilin 1 |

| Gene | DIM | HES | NAR | NOB | SIN | TAN | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ccl20 | 2.482 | 70.47 | 64.112 | 3.881 | 32.516 | 35.877 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 |

| Mif | 1.736 | 1.977 | 2.061 | 2.159 | 1.811 | 1.779 | macrophage migration inhibitory factor |

| Ccl11 | 0.053 | 0.083 | 0.171 | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.036 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 11 |

| Ccl17 | 0.265 | 1.256 | 0.615 | 0.101 | 0.058 | 0.059 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 17 |

| Ccl2 | 0.218 | 3.893 | 3.602 | 0.464 | 0.68 | 1.229 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 |

| Ccl5 | 0.491 | 11.7 | 11.249 | 1.53 | 0.697 | 6.501 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 |

| Ccl6 | 0.913 | 1.2 | 0.127 | 0.332 | 0.067 | 0.104 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 6 |

| Ccl7 | 0.385 | 1.876 | 1.806 | 0.283 | 0.351 | 0.614 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 7 |

| Ccl8 | 0.042 | 0.465 | 0.487 | 0.063 | 0.046 | 0.186 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 |

| Ccl9 | 3.265 | 4.79 | 0.747 | 1.218 | 0.715 | 0.554 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 |

| Csf1 | 0.434 | 2.595 | 2.388 | 0.948 | 1.111 | 1.329 | colony stimulating factor 1 (macrophage) |

| Cx3cl1 | 0.574 | 0.752 | 0.455 | 0.09 | 0.111 | 0.253 | chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 |

| Cxcl1 | 0.667 | 52.143 | 50.38 | 10.686 | 24.211 | 40.167 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 |

| Cxcl10 | 0.843 | 7.685 | 10.55 | 0.084 | 0.099 | 2.648 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 |

| Cxcl11 | 1.000 | 6.312 | 20.456 | 1.956 | 1.073 | 2.313 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 |

| Cxcl5 | 0.16 | 81.203 | 48.136 | 3.01 | 5.966 | 15.186 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 |

| Il15 | 2.537 | 5.296 | 26.586 | 1.000 | 1.108 | 5.917 | interleukin 15 |

| Il1a | 1.00 | 10.557 | 20.857 | 3.888 | 8.128 | 11.901 | interleukin 1 alpha |

| Il33 | 0.379 | 3.836 | 1.749 | 0.027 | 0.376 | 0.74 | interleukin 33 |

| Nampt | 3.857 | 3.437 | 3.692 | 3.04 | 2.645 | 2.719 | nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| Target | Ligand | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) |

Interaction | |

| Hydrophobic | Hydrogen bond | |||

| AhR |

HES | -8.9 | Ala79, Ile154, Leu118, Leu119, Phe56, Phe83, Pro55, Ser139, Ser75, Tyr76, Val126 |

Gln150, Lys80, Phe136, Ser140,Tyr137 |

| NAR | -8.7 | Ala79, Ile154, Leu118, Leu119, Phe56, Phe83, Pro55, Ser139, Ser75, Tyr76, Val126, |

Gln150, Lys80, Phe136, Ser140,Tyr137 | |

| NOB | -6.6 | Glu116, Gly115, Ile154, Leu199, Leu72, Phe136, Phe56, Phe83, Pro55, Ser75, Tyr137, Tyr76 |

- | |

| SIN | -6.8 | Ala79, Glu116, Gly115, Ile154, Leu119, Leu72, Phe136, Phe56, Pro55, Ser75, Tyr137, Tyr76 |

- | |

| TAN | -6.7 | Ala79, Gln150, Gly115, Ile154, Leu119, Leu72, Phe56, Phe83, Ser75, Tyr137,Tyr76 |

- | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).