1. Introduction

In an increasingly globalized world, English has established itself as the primary language for international communication, attracting learners from various linguistic backgrounds. Language learning encompasses not only grammar and vocabulary, but also accent and pronunciation, which significantly affect communicative competence and speech standardization [

1]. Regional accents, shaped by speakers’ native languages, often introduce challenges in achieving clear and comprehensible English. Recent advancements in deep learning technologies have accelerated the development of speech analysis systems, demonstrating their potential to enhance language learning outcomes. However, regional accents, often influenced by a speaker’s native language, introduce challenges in achieving clear and comprehensible English. Recent advances in deep learning technology have fueled the development of sophisticated speech analysis systems, offering potential for improving language learning outcomes through enhanced pronunciation feedback [

2,

4]. Furthermore, pronunciation is a fundamental component of effective communication, yet it remains one of the most challenging aspects for language learners. nonnative speakers often substitute phonemes with those familiar from their native languages, producing distinct accents that can impede mutual understanding [

1,

7]. Addressing pronunciation through targeted learning tools not only enhances learners’ speech intelligibility but also fosters confidence and fluency in language use [

2,

6]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in particular, have proven to be effective in feature extraction and classification tasks within speech recognition [

3,

6]. These models can discern intricate patterns in audio data, making them highly suitable for accent recognition and pronunciation analysis. Nevertheless, the majority of studies focus on major English accents, such as American and British, with limited exploration and application for a broader array of nonnative accents [

4,

5,

8]. Machine learning techniques, including Mel frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) and spectrogram-based feature extraction, have shown promise in classifying and assessing nonnative pronunciation [

7,

11]. Such approaches enable more precise identification of speech characteristics, contributing to personalized feedback systems designed to support accent improvement and language learning. Deep learning-powered speech analysis systems offer a refined approach to evaluating pronunciation and accent, providing feedback with greater accuracy. By utilizing models trained on diverse linguistic data, these systems offer feedback tailored to learners’ unique needs, encouraging an iterative learning process [

8,

9]. This focus on accent adaptation and enhancement is crucial for supporting language acquisition and reducing communication barriers among nonnative speakers. Despite substantial progress, current speech recognition and analysis systems encounter limitations, particularly in handling a wide range of accents with the same efficacy as native accents [

5]. Most models are optimized for standard American and British English, leading to an underrepresentation of nonnative accents [

4,

11]. Additionally, noise sensitivity and variations in pronunciation reduce the effectiveness of these systems in real-world scenarios [

3,

5].

In a study by Ensslin et al. [

6], deep learning was investigated for speech accent detection within video games, with a focus on sociolinguistic aspects, such as stereotypical accent usage and related social judgments. AlexNet was trained on the Speech Accent Archive data and applied to audio from a video game. To optimize the model, experiments were conducted with varying parameters, including epochs, batch sizes, time windows, and frequency filters, resulting in an optimal test accuracy of 61%. Following training, 75% accuracy was achieved on the Speech Accent Archive data and 52.7% accuracy on game audio samples, with accuracy improving to 60% in low-noise conditions. Limitations in speech analysis systems, which are typically optimized for American and British English, were addressed by Upadhyay and Lui [

4]. A model capable of classifying nonnative accents was developed. Audio signals were pre-processed and converted to MFCCs. Four classification methods were tested: Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, CNN, and Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP). Among these methods, the CNN model demonstrated the highest accuracy, achieving rates between 80% and 88%, significantly outperforming traditional approaches.

Foreign-accented English classification was explored by Russell and Najafian [

5] to determine speakers’ countries of origin. A corpus of 30 speakers from six countries was developed, and MFCC features were used with a Deep Belief Network (DBN) classifier. After noise cancellation and normalization, the DBN model, consisting of two hidden layers with 1000 nodes 90 each, achieved 90.2% accuracy for two accents and 71.9% for six accents, outperforming conventional classifiers like SVM, k-NN, and Random Forest. Pronunciation quality in English learners was assessed by Nicolao et al. [

10] using deep neural network features and phoneme-specific discriminative classifiers. A system was introduced to provide phoneme-level scoring based on teacher-annotated error patterns. Learner pronunciation was compared with a reference, and pronunciation scores were generated based on phoneme duration and similarity.

For mobile-assisted pronunciation learning, the Smartphone-Assisted Pronunciation Learning Technique (SAPT) was proposed by Lee et al. [

9]. Pronunciation errors were detected, and words were recommended for practice. Processing was offloaded to an Internet of Things (IoT) system to address the constraints of low-computation devices. Through a seven-step process, user speech was analyzed, phoneme correlations were evaluated, and practice words were suggested. Finally, pronunciation variation across English varieties was addressed by Kasahara et al. [

8]. A structure-based method to predict pronunciation distances was proposed. Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Bhattacharyya Distances (BDs) were used to represent pronunciation differences. Local contrasts and phonetic class features were identified as significant contributors to accurate pronunciation distance predictions, as indicated by high correlation scores. In [

26], MALL was proposed as a tool to enhance student motivation and readiness, promoting flexibility and engagement in language learning for achieving positive outcomes. However, the study faced limitations, including a restricted sample from Indian universities, hardware constraints affecting speaking and listening tasks, a narrow focus on English. Liu et al. [

27] proposed a knowledge based intelligence program to address pronunciation challenges. The proposed methods achieved significant accuracy in classifying correct and incorrect pronunciations. However, the study’s limitations include a small dataset and its generalizability to other phonemes and real-world contexts. Recently, Rukwong and Pongpinigpinyo [

28] introduced an innovative approach to computer-assisted pronunciation training (CAPT) for Thai vowel recognition, leveraging CNN and acoustic features such as Mel spectrograms. Their system effectively addresses key challenges in Thai vowel pronunciation training, including the reliance on expert intervention and the complexity of traditional manual methods. While the system demonstrated impressive accuracy of 98.61%, its limitations include a reliance on a narrowly focused dataset of standard Thai speakers in controlled environments, raising concerns about its adaptability and robustness in diverse real-world scenarios.

Although significant progress has been demonstrated in accent classification and pronunciation analysis, several limitations remain. Most systems prioritize American and British English accents, with limited application to nonnative or regional varieties. Few studies address the challenges of deploying these systems on resource-constrained mobile platforms [

9]. Additionally, current systems rarely accommodate multiple languages or integrate multimodal inputs, which limits their adaptability.

Pronunciation, a fundamental component of language proficiency, remains one of the most challenging aspects for nonnative speakers to master. Current speech feedback systems often lack the precision, accessibility, and personalization needed to significantly improve pronunciation skills. This study addresses these limitations by introducing a novel Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) application that leverages deep learning technology to analyze nonnative English accents with unprecedented accuracy. Our system employs advanced pre-processing techniques and multiple feature extraction methods, including mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) and spectrograms, to create a robust framework for accent identification and customized pronunciation feedback. By prioritizing inclusivity and accuracy within a user-friendly mobile interface, the proposed MALL application bridges the critical gap between self-guided learning and professional pronunciation training. The system's interactive and adaptive approach enables learners to practice independently while receiving clear, actionable feedback that facilitates continuous improvement. This research not only enhances the technological capabilities of pronunciation assessment but also transforms the learning experience for nonnative speakers by making expert-level guidance accessible anytime and anywhere through mobile technology.

3. Results

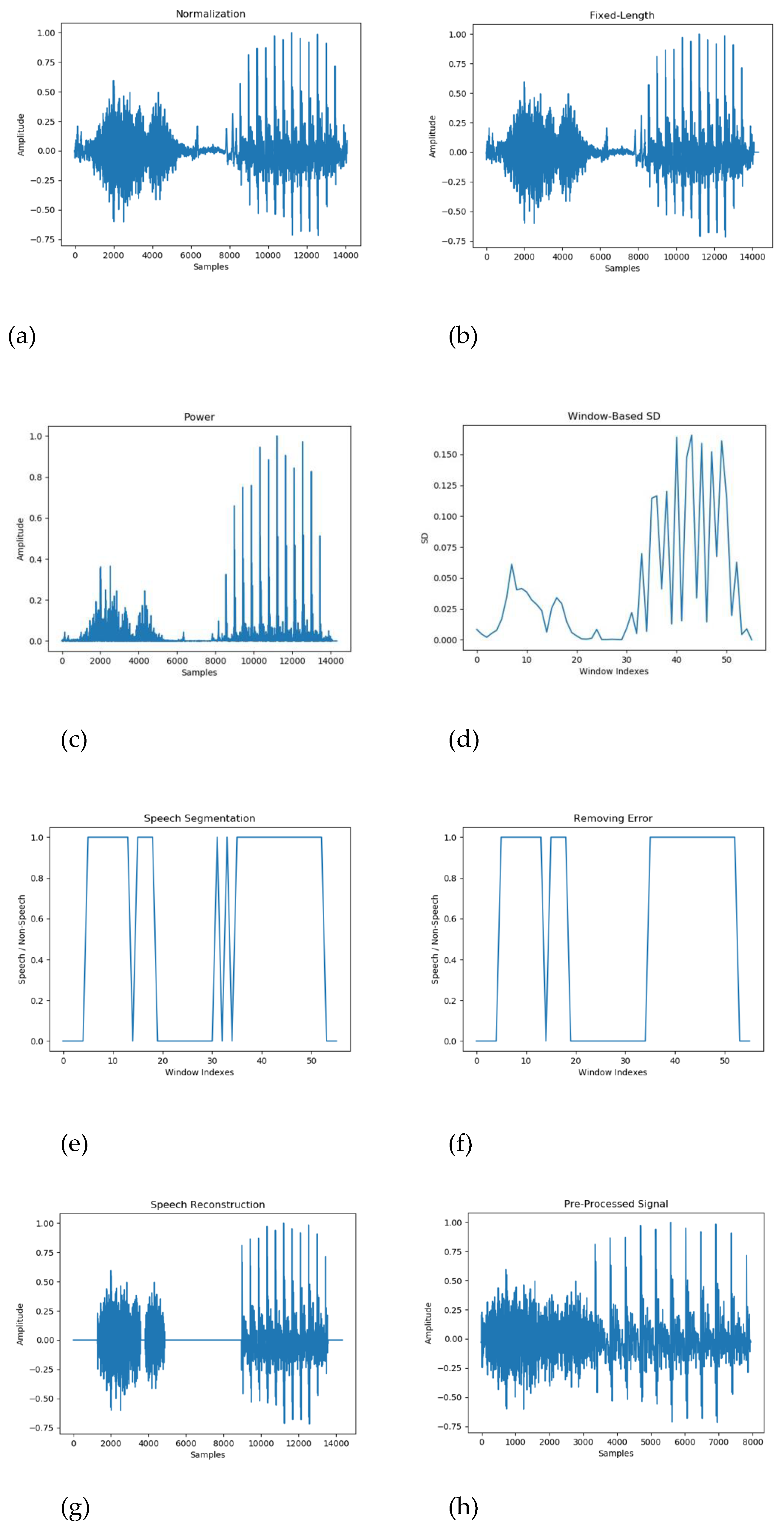

The pre-processing phase is essential for enhancing the quality and consistency of audio signals before feature extraction and classification.

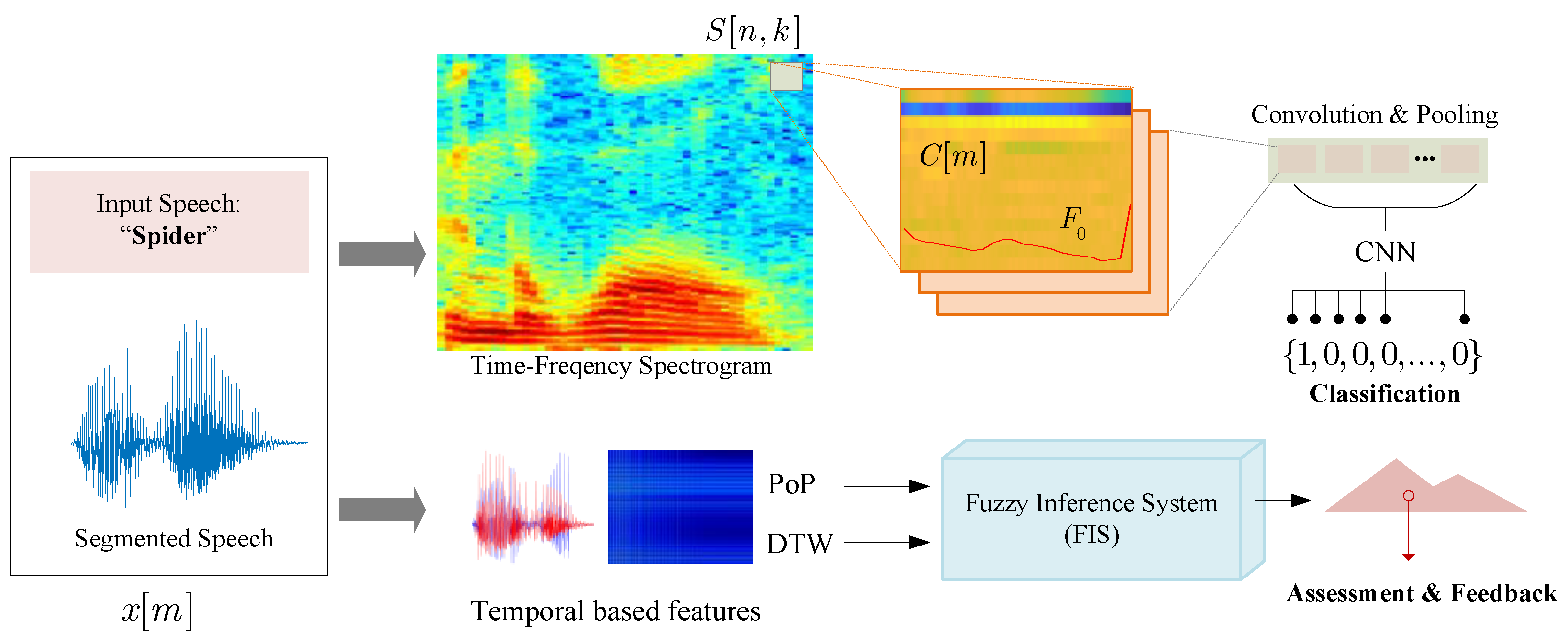

Figure 3 shows the preprocessing stages, how the original audio signal undergoes transformations such as zero-mean normalization, fixed-length segmentation, and noise removal to improve clarity and uniformity.

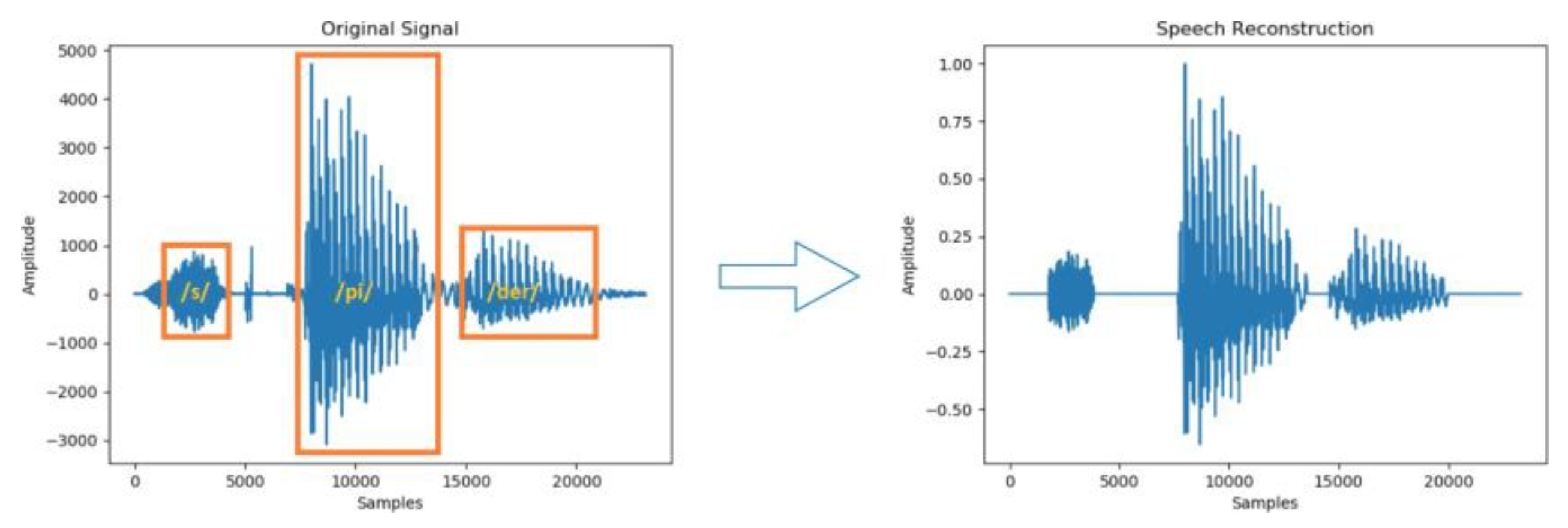

Figure 4 highlights the impact of preprocessing on the audio signal, illustrating significant improvements in clarity and consistency. These enhancements directly affect the quality of extracted features, which form the basis of the classification model.

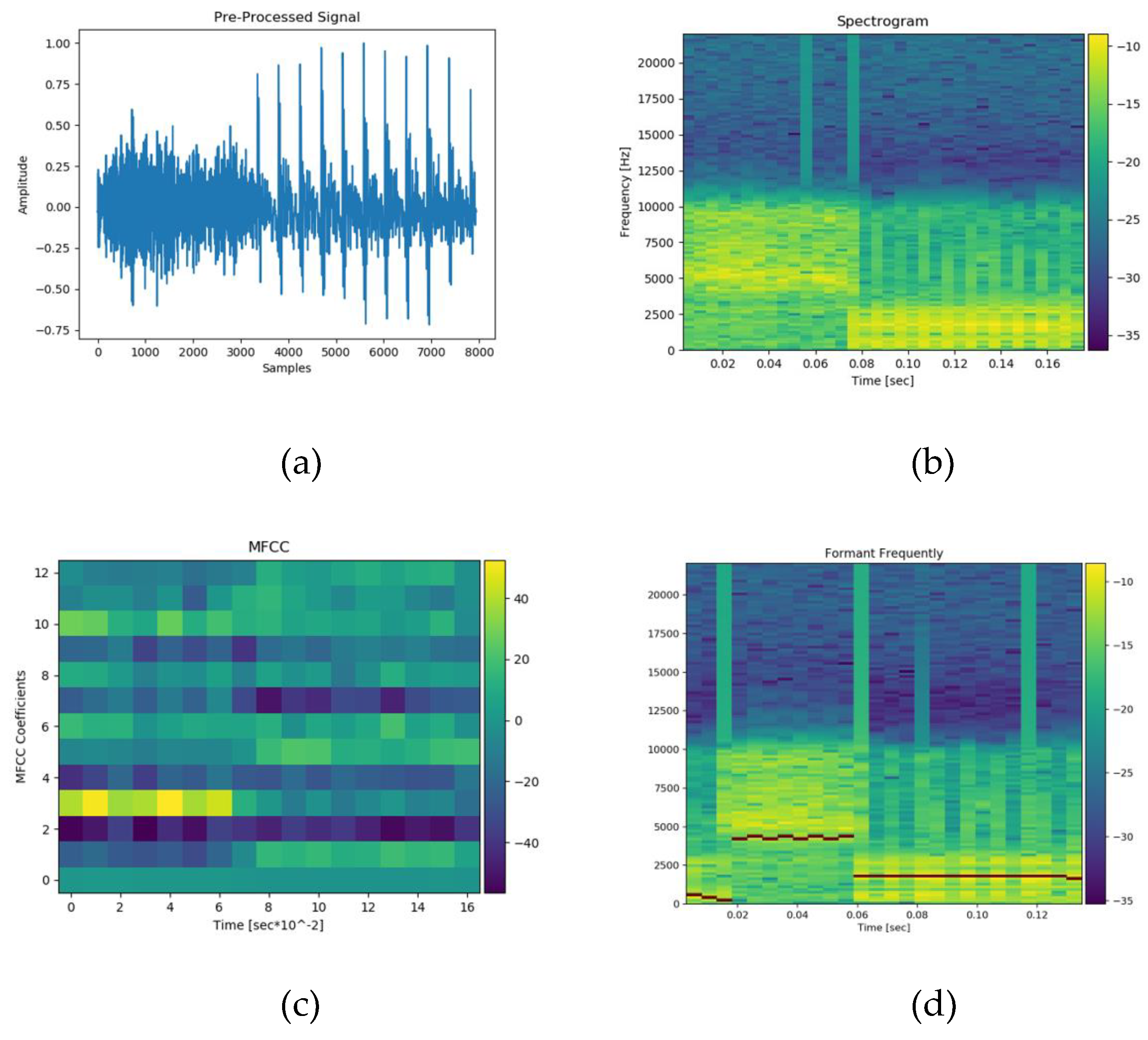

Figure 5 provides an overview of the extracted features used for classification, including spectrograms, MFCCs, and formant frequencies. These features serve as critical inputs for the CNN model and contribute to its high classification accuracy, as demonstrated in [

19]. The proposed method involves a feature extraction procedure aimed at identifying salient characteristics from a pre-processed signal to form a two-dimensional array with unique properties. These two-dimensional representations-Spectrogram and MFCC-are then used as input data for the CNN model, both as array data and image data, formatted with a resolution of 640x480 pixels.

3.1. Data Preparation

The dataset used in this study was sourced from the OSCAAR (Open Speech Corpus for Accent 270 Recognition), which contains a scripted reading scenario. In this scenario, participants clearly enunciated a scripted list of words one at a time. This dataset proved valuable during the pre-processing step, where we segmented individual word utterances from the original speech recording. The segmentation produced a collection of word-level utterances, which were then used for further feature extraction and analysis.

In addition to the Hoosier database of native and nonnative speech, this database includes digital audio recordings of both native and nonnative English speakers reading words, sentences, and paragraphs, providing a diverse range of speech samples for our study. The Hoosier Database

1 of Native and nonnative Speech consists of 27 speakers, representing the aforementioned seven native language backgrounds. These speakers produced a total of 1,139 recordings across the various tasks listed in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

This study also includes a group of Chinese-accented subjects who participated in the experiment. A total of 50 participants were selected (25 male and 25 female), with ages ranging from 18 to 30 years. None of the subjects had any prior background in English proficiency tests. The audio signals were recorded in a soundproof studio, ensuring a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 60 dB or higher, in line with the standard for high-quality studio sound recordings. The recordings were captured at Dali University, where all participants gave their informed consent to take part in the study. The inclusion of this additional accent category serves two primary purposes: first, to explore the development of a system designed to help native Chinese speakers learn other languages, and second, to investigate how variations in the dataset may influence the performance of deep learning models. This research aims to measure the impact of these differences on the model’s accuracy and robustness. The participants were selected from a group of native Chinese individuals with no history of exposure to environments that might influence their pronunciation, such as attending international schools from a young age or engaging in prolonged daily interactions with foreigners. For the recordings, a sampling rate of 44,100 Hz was used. The recordings were made in a mono-channel configuration, with a 16-bit resolution, ensuring high-quality, precise sound capture.

3.2. Model Training and Test Results

The approach employed in this study leverages deep learning techniques to develop a reference-based model for word pronunciation. This model functions as a classifier to analyze, assess, and classify pronunciation accuracy from speech or word input. The proposed method utilizes a CNN model to achieve this task. The data used to train the deep learning model consists of the extracted features from the pronunciation audio of words or speech, which are represented through corresponding spectrograms, MFCCs, and formant frequencies. The CNN model was trained with different feature sets, including MFCCs, spectrograms, and formant frequencies.

The results, summarized in

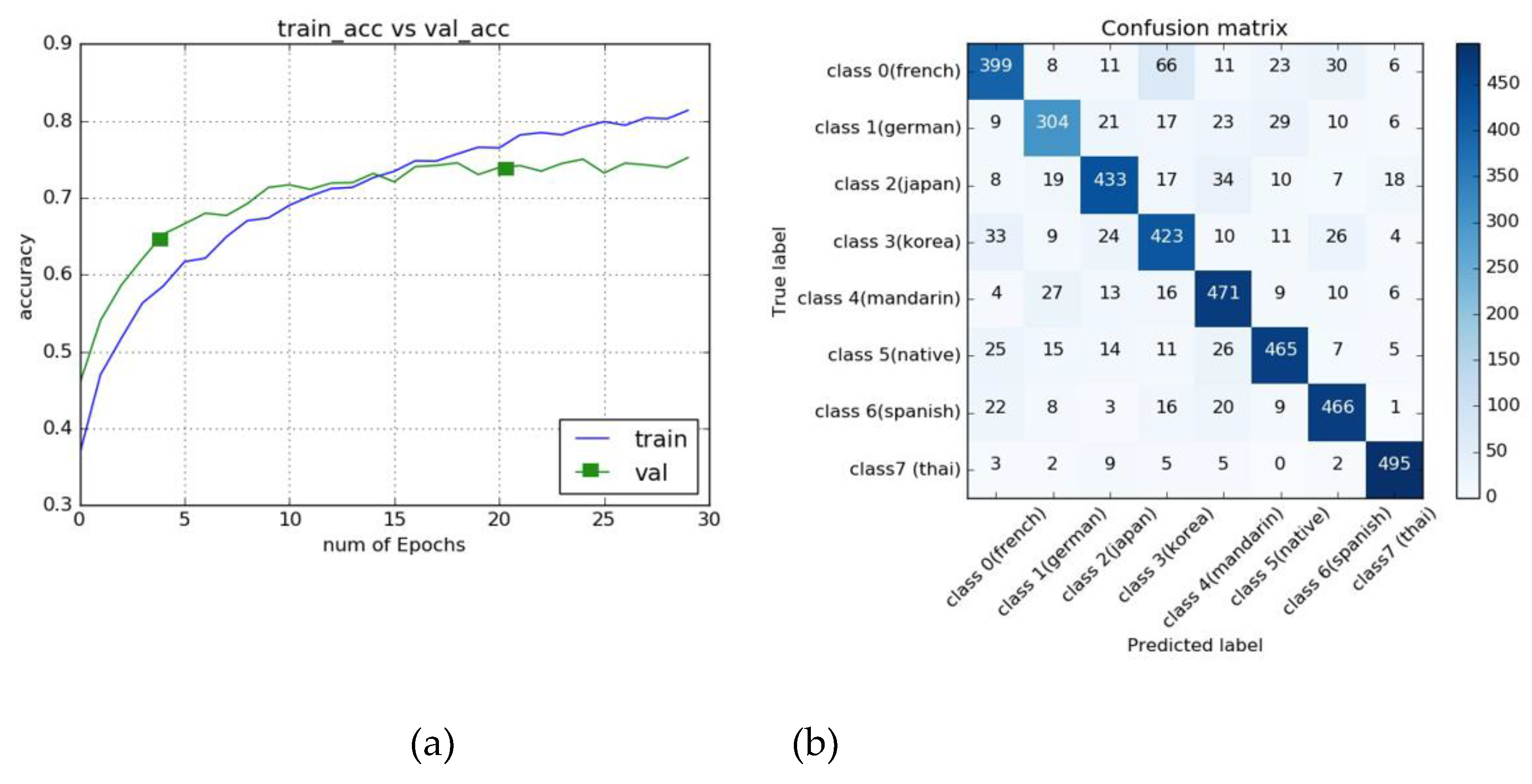

Table 4, highlight the effectiveness of MFCCs and spectrograms, with test accuracies peaking at 73.89% and 74.27%, respectively. As demonstrated by previous research, MFCCs can achieve high precision when used for accent classification. In this study, we aim to investigate how the chosen dataset and pre-processing methods impact the classification results across eight distinct accent classes.

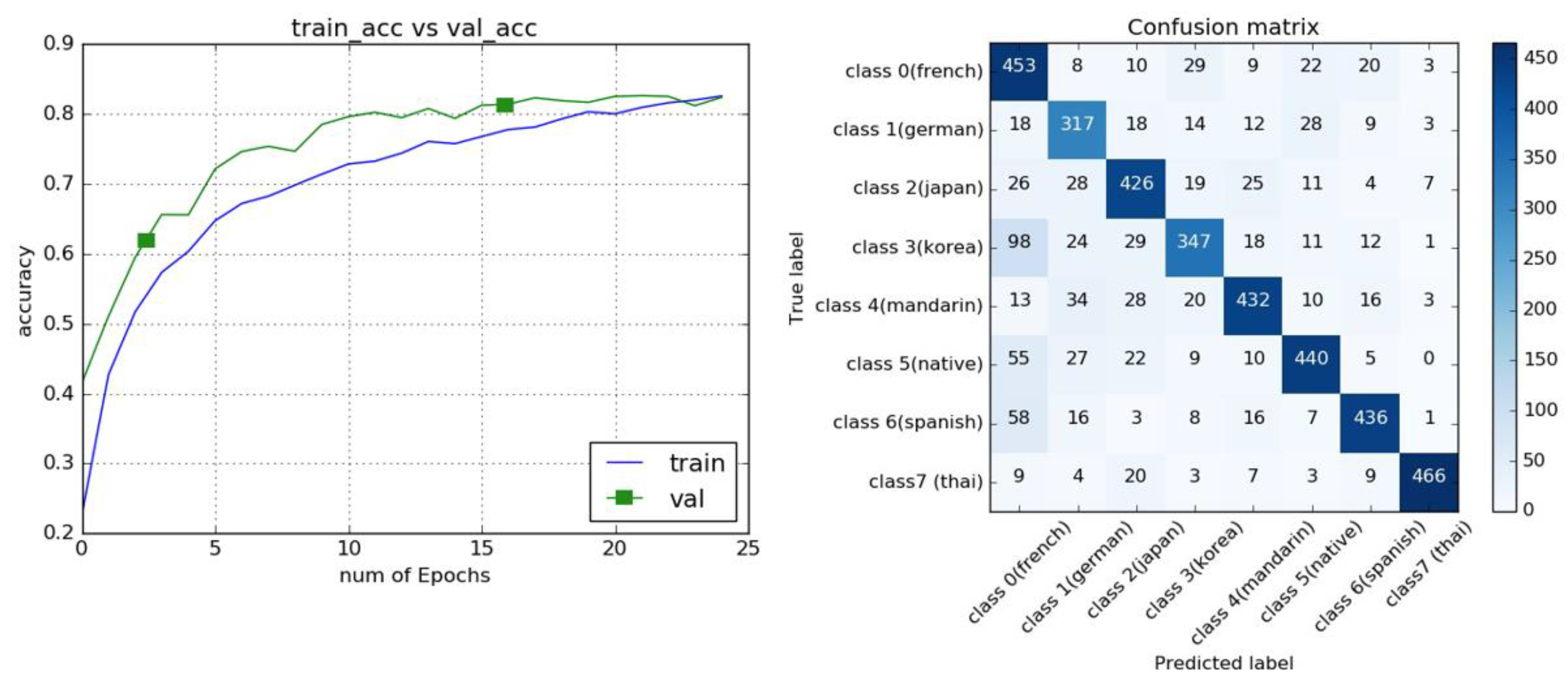

Figure 6 (a) illustrates the average accuracy across all parameters during the training of the classification model using the MFCC dataset with a 0.005 threshold over 30 epochs. After the 15th epoch, the model began to overfit: while the training accuracy continued to improve, the testing accuracy plateaued and remained stagnant.

Figure 6 (b) presents the confusion matrix for the MFCC-based model. The distribution of correctly predicted accents is relatively uniform across the different accent classes, with most classes having a prediction frequency exceeding 300 instances in the test dataset. This discrepancy is attributed to the unequal distribution of data, as the German-accented speech data were approximately 20% less than other accent data, leading to a slight imbalance in predictions. The spectrogram-based model demonstrated superior performance, achieving a peak test accuracy of 79% when optimized network parameters were applied, as shown in

Table 4. This underscores the ability of spectrograms to capture more detailed temporal and frequency-related information, providing a more comprehensive representation of the speech signal compared to MFCCs alone.

In

Table 5, the highest precision achieved by the model was 0.829, while the lowest precision across all parameters derived from MFCC-based data was 0.7878. These results indicate that the spectrogram approach consistently outperformed the MFCC method.

Figure 7 (a) illustrates the average accuracy across all parameters while training the classification model using the spectrogram dataset with a threshold of 0.005 and 30 epochs. After approximately the 24th epoch, the accuracy stabilized and ceased to improve.

Figure 7 (b) shows the prediction map for all classes from the classification model trained using spectrograms. The pattern is consistent across all classes, with a very high prediction rate, except for the German accent, which showed lower accuracy. The highest classification accuracy, approximately 87%, was achieved by combining MFCCs and spectrograms. This approach leverages both the frequency emphasis from MFCCs and the temporal detail from spectrograms, optimizing the model’s classification capabilities for accent detection.

3.3. Period of Phonetic (PoP)

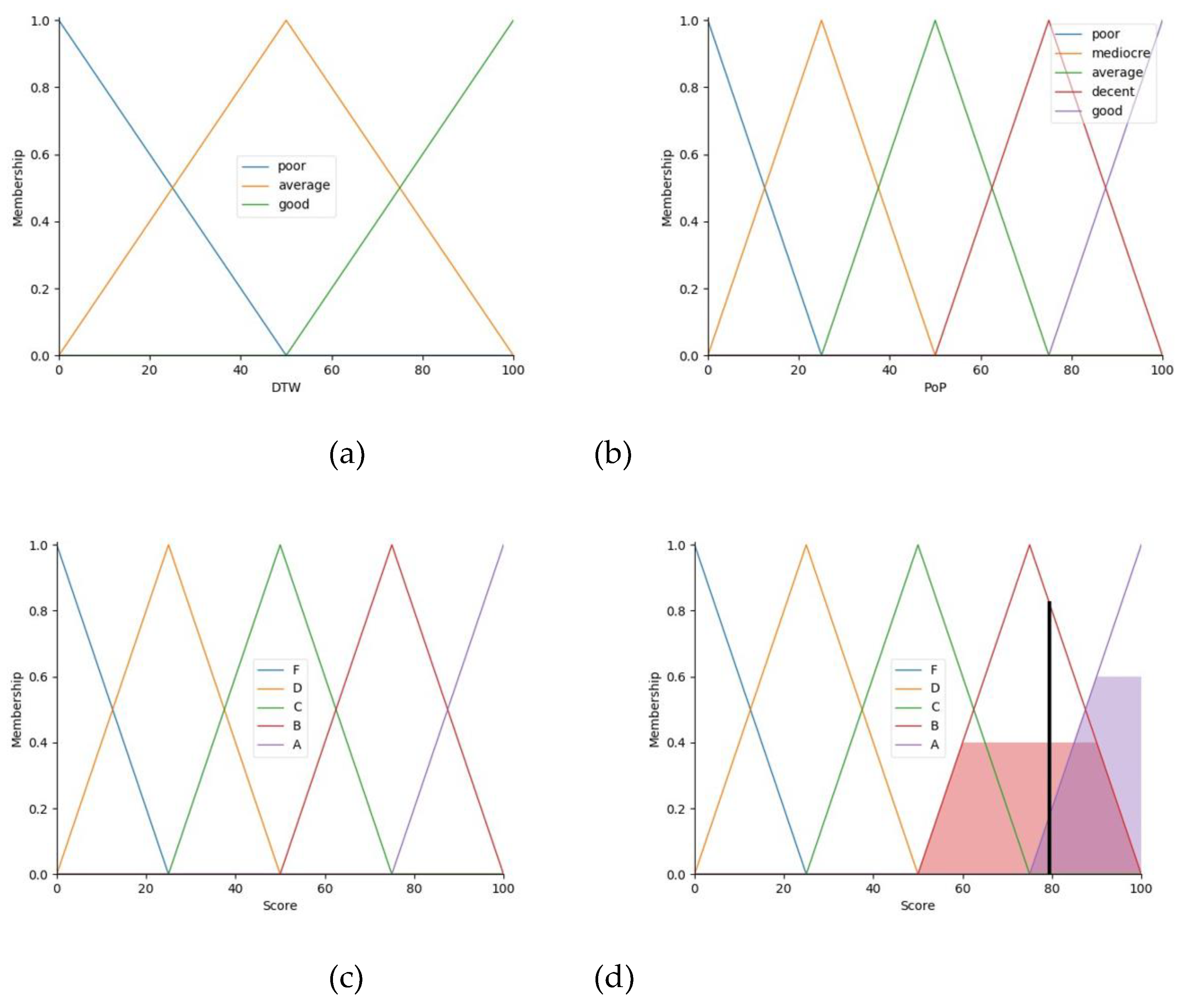

PoP approach begins by segmenting the phonetic components of the sample signal using a preprocessing method. The resulting PoP value represents the time (in seconds) of each segmented part of the sample signal, as compared to each corresponding template segment. During the segmentation process, a single threshold is insufficient to achieve optimal segmentation results. Therefore, an adaptive thresholding method is employed, which spans values from 0.001 to 0.017. The PoP values are constrained within a range of 0 to 1 second. PoP is converted into five sets of fuzzy since its value can distinguish the range of similarity better including poor, mediocre, average, decent, and good.

3.4. Dynamic Time Warping (DTW)

DTW is used to extract features from the MFCCs of both the template and sample signals. DTW measures the similarity between the temporal sequences of the signals, producing a normalized distance value. DTW is converted into three sets of fuzzy due to the large boundary of its value including poor, average, and good.

3.5. Knowledge Base

This section stores IF-THEN rules in the format illustrated in

Table 6, which represents a matrix of DTW values and PoP values. In

Figure 9 (d), the score obtained from evaluation is shown. The centroid estimation method, used to find the center of the graph area, computes the result. For this example, the final decision using the center of gravity is approximately 79.39.

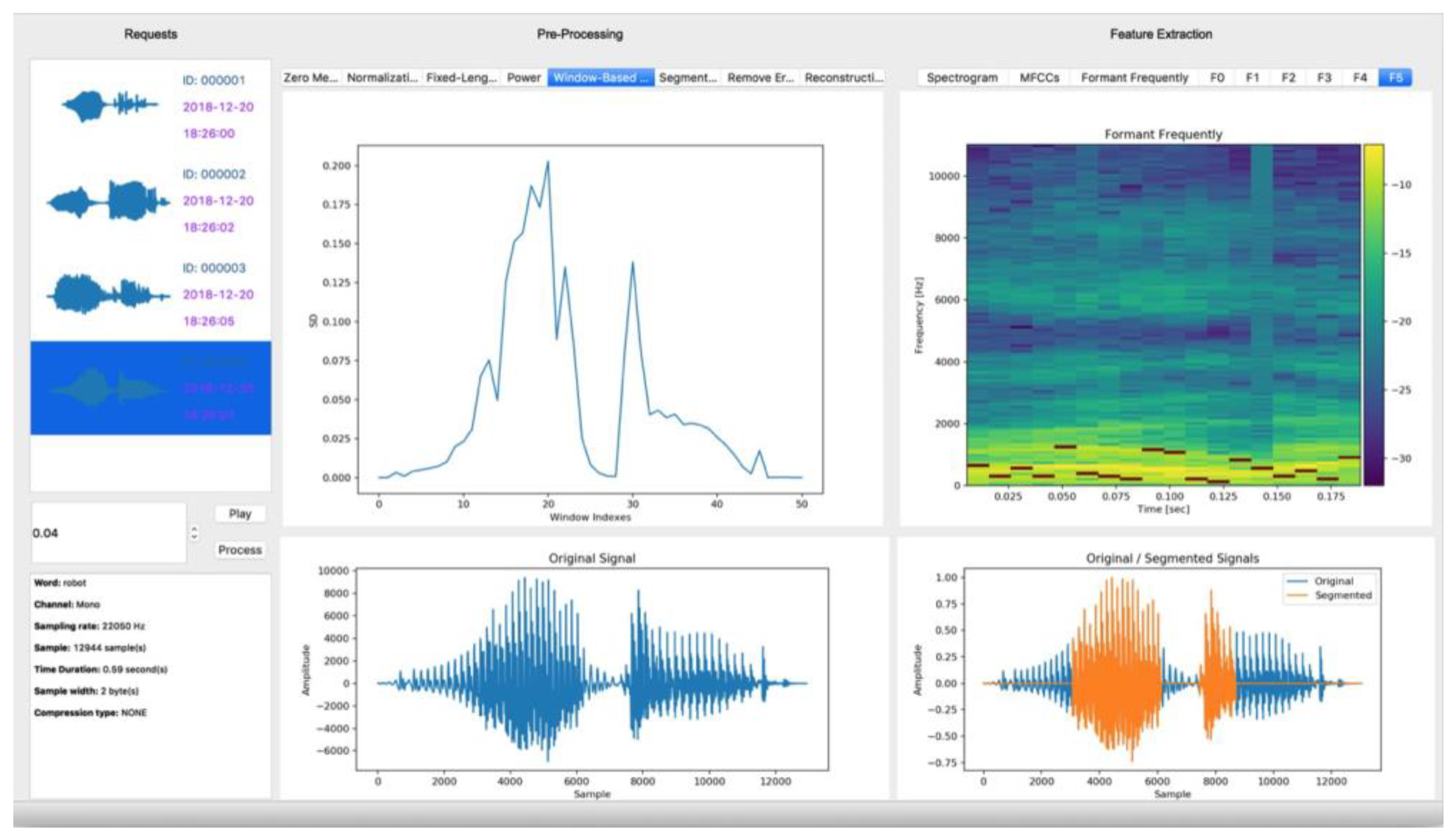

The proposed system features a server monitoring interface, as shown in

Figure 8, which presents overview of the entire processing. This includes the preprocessing and feature extraction steps, ensuring that the system not only provides immediate feedback to the user but also performs real-time assessment and analysis in the background. This integrated approach helps maintain the accuracy and consistency of the pronunciation evaluation throughout the process.

Figure 8.

Server Monitoring Interface of the Proposed System. This interface provides a comprehensive overview of the entire processing workflow, including preprocessing and feature extraction steps. It enables real-time evaluation and feedback of pronunciation accuracy while maintaining system performance and consistency in analysis.

Figure 8.

Server Monitoring Interface of the Proposed System. This interface provides a comprehensive overview of the entire processing workflow, including preprocessing and feature extraction steps. It enables real-time evaluation and feedback of pronunciation accuracy while maintaining system performance and consistency in analysis.

Figure 9.

Membership functions and final score evaluation: (a) DTW, (b) PoP, (c) Score, and (d) Final score after evaluation.

Figure 9.

Membership functions and final score evaluation: (a) DTW, (b) PoP, (c) Score, and (d) Final score after evaluation.

3.6. Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL)

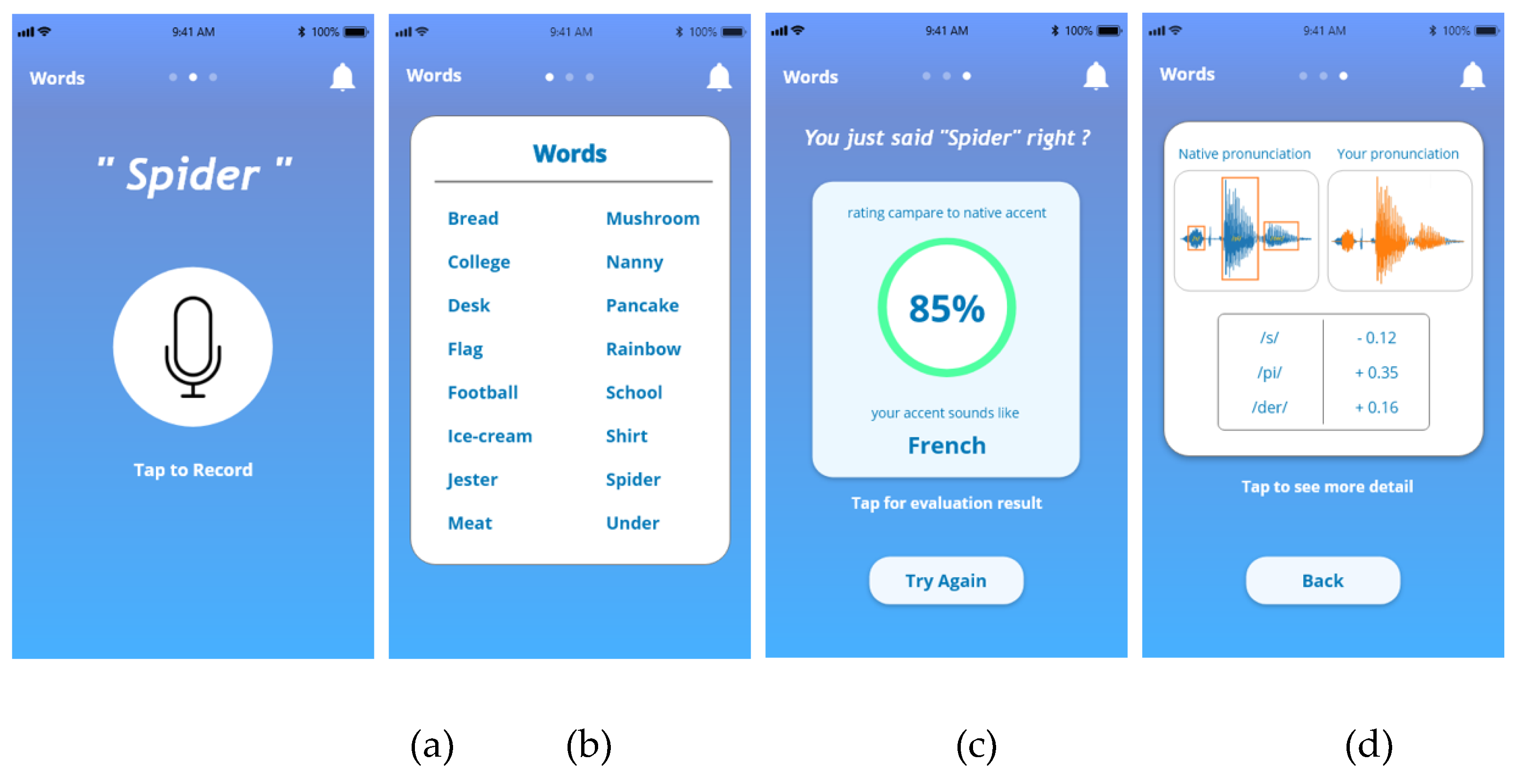

To implement a mobile platform interface showcasing the system’s workflow, we utilized the React Native framework, a hybrid mobile development framework that enables efficient development while ensuring compatibility with both Android and iOS platforms.

Figure 10 (a) presents the main page, where users can interact with the MALL system by pressing the microphone button to record audio. The recorded audio is automatically sent to the server for processing.

Figure 10 (b) displays the list of available words that can be assessed using the proposed method.

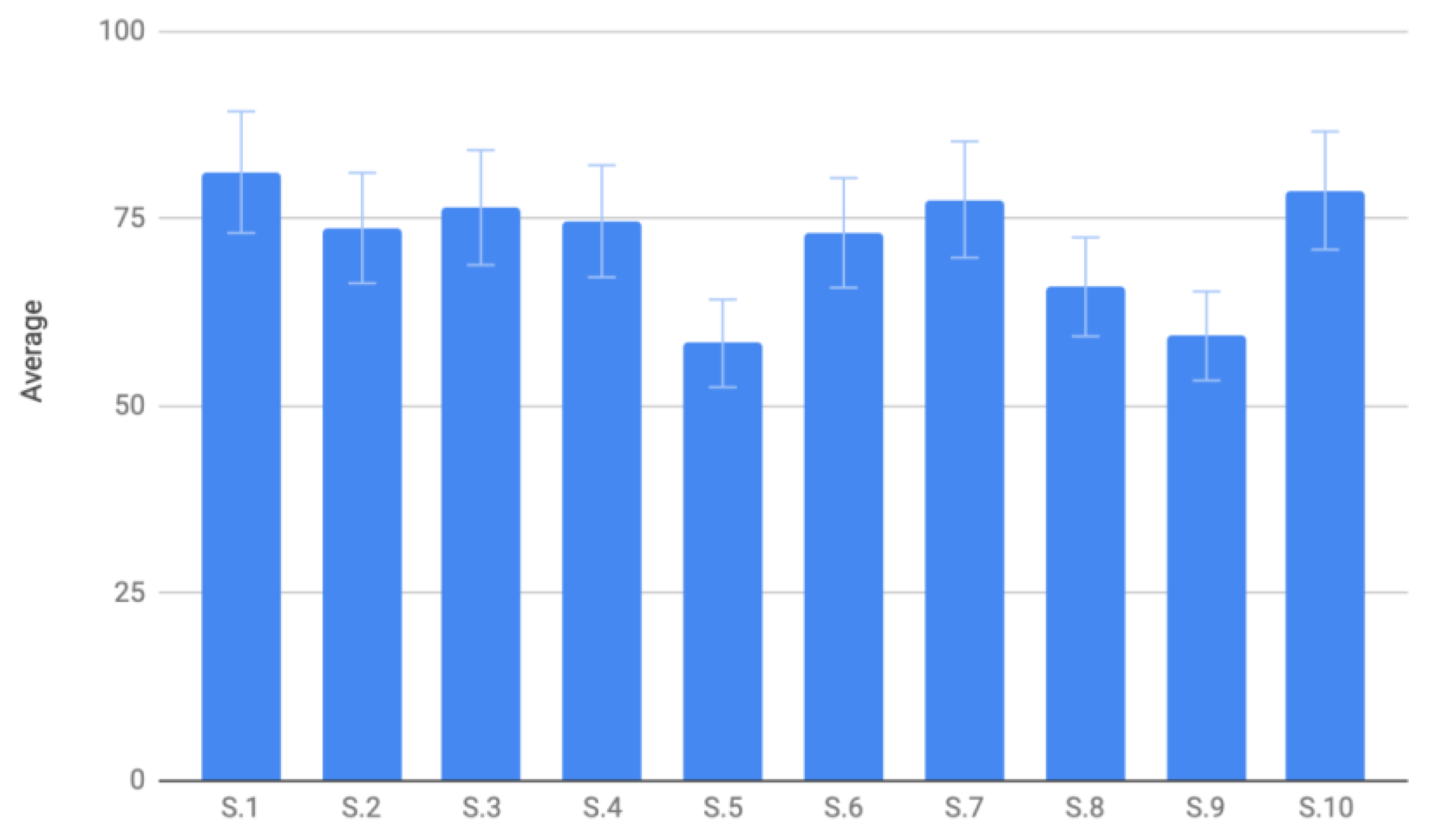

Figure 11 illustrates the results of 10 selected subjects, chosen from a total of 50 participants, who attempted to pronounce 10 words with 5 trials per word. The scores range from 55 to 80, compared to the native speakers’ scores, which range from 80 to 100. The standard deviations are represented by the error bars. Notably, all selected subjects had studied in an international program, which may have contributed to their relatively high initial scores.

Before using the MALL proposed system, the subjects’ pronunciation correctness was significantly lower, with scores trailing the native speech data by 5% to 20%. After utilizing the MALL system, which provided real-time feedback and detailed pronunciation assessments, all subjects showed notable improvement in their pronunciation accuracy. The increased scores highlight the system’s effectiveness in bridging the gap between nonnative and native pronunciation, demonstrating its potential as a powerful tool for language learning and accent refinement.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a comprehensive mobile-assisted pronunciation analysis system that leverages convolutional neural networks and fuzzy inference to provide personalized, real-time feedback for language learners. Through the integration of advanced pre-processing techniques and multiple complementary feature extraction methods—spectrograms, MFCCs, and formant frequencies—our system effectively analyzes and classifies pronunciation patterns across diverse accent profiles. The incorporation of a fuzzy inference system enables context-aware assessment that accommodates the natural variability inherent in human speech, providing feedback that is both precise and interpretable.

Our experimental results demonstrate the power of feature fusion in improving classification accuracy, achieving approximately 87% when combining spectrograms and MFCCs—significantly outperforming single-feature approaches. User testing confirmed the system's practical effectiveness, with participants showing measurable improvements in pronunciation accuracy after using the application. These findings align with existing research on the importance of robust feature extraction while extending the practical application of deep learning in educational technology.

The mobile platform implementation addresses accessibility needs in language education, allowing learners to practice pronunciation independently and receive immediate feedback regardless of location. Despite its current capabilities, limitations in multilingual support and computational efficiency on mobile platforms indicate promising directions for future research. Expanding the system to support additional languages, incorporating adaptive learning mechanisms that personalize feedback based on learner progress, and optimizing performance on resource-constrained devices represent important next steps. These advancements would further enhance the system's impact as an effective tool for self-directed language learning in our increasingly globalized world.

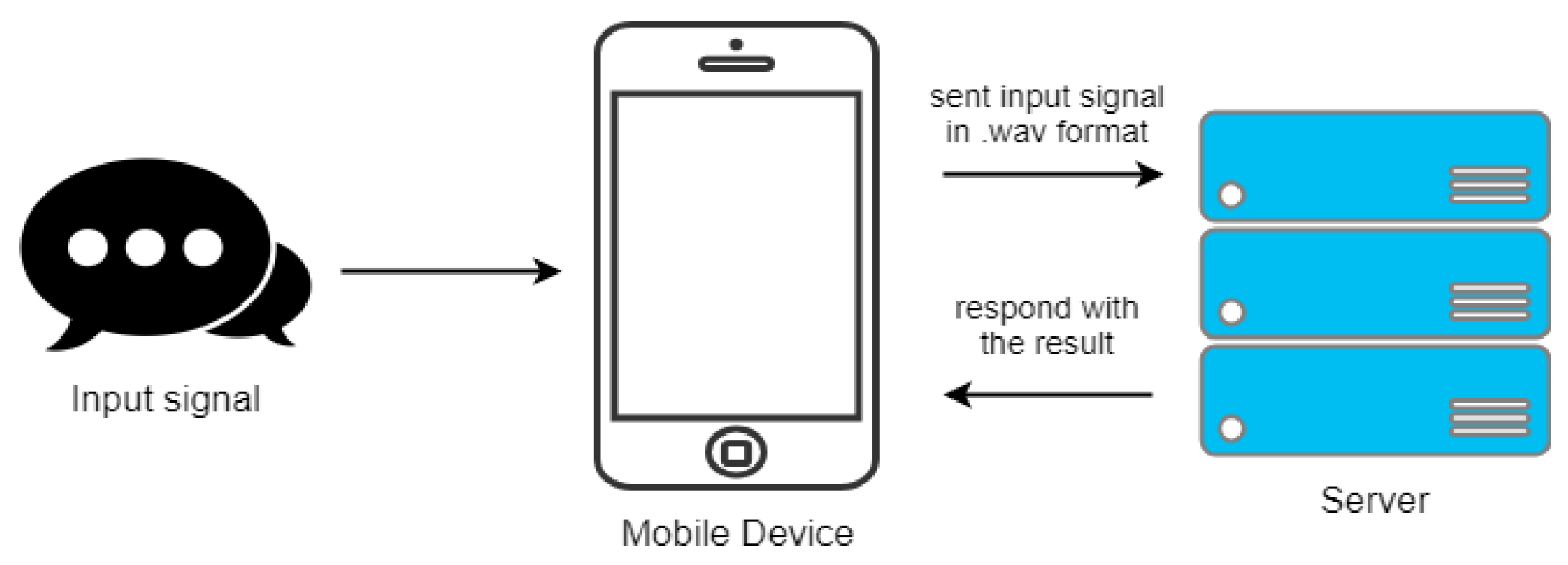

Figure 1.

Client-server architecture of the proposed system.

Figure 1.

Client-server architecture of the proposed system.

Figure 2.

System overview of the proposed method.

Figure 2.

System overview of the proposed method.

Figure 3.

Step-by-step preprocessing of the original speech signal to the segmented signal, they should be listed as: (a) Normalization; (b) Fixed-Length; (c) Power; (d) Window-based SD; (e) Speech Segmentation; (f) Removing Error; (g) Speech Reconstruction and (h) Pre-Processed Signal.

Figure 3.

Step-by-step preprocessing of the original speech signal to the segmented signal, they should be listed as: (a) Normalization; (b) Fixed-Length; (c) Power; (d) Window-based SD; (e) Speech Segmentation; (f) Removing Error; (g) Speech Reconstruction and (h) Pre-Processed Signal.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the original signal before and after preprocessing.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the original signal before and after preprocessing.

Figure 5.

Extracted features in this study, they should be listed as: (a) Pre-processed speech signal; (b) Spectrogram feature; (c) MFCC feature and (d) Formant Frequency.

Figure 5.

Extracted features in this study, they should be listed as: (a) Pre-processed speech signal; (b) Spectrogram feature; (c) MFCC feature and (d) Formant Frequency.

Figure 6.

Training Results for MFCC and Confusion Matrix for MFCC with 0.005 Threshold (a) Training Results for MFCC, (b) Confusion Matrix for MFCC.

Figure 6.

Training Results for MFCC and Confusion Matrix for MFCC with 0.005 Threshold (a) Training Results for MFCC, (b) Confusion Matrix for MFCC.

Figure 7.

Training Results for Spectrogram and Confusion Matrix for Spectrogram with a Threshold of 0.005, (a) Training Results for Spectrogram, (b) Confusion Matrix for Spectrogram.

Figure 7.

Training Results for Spectrogram and Confusion Matrix for Spectrogram with a Threshold of 0.005, (a) Training Results for Spectrogram, (b) Confusion Matrix for Spectrogram.

Figure 10.

Overview of the MALL system, highlighting its main functionalities: (a) audio recording, (b) word selection, (c) result processing, and (d) detailed feedback.

Figure 10.

Overview of the MALL system, highlighting its main functionalities: (a) audio recording, (b) word selection, (c) result processing, and (d) detailed feedback.

Figure 11.

Assessment results showing pronunciation average scores in percentage.

Figure 11.

Assessment results showing pronunciation average scores in percentage.

Table 1.

Libraries utilized in the implementation process.

Table 1.

Libraries utilized in the implementation process.

| Library |

Version |

Purpose |

| TensorFlow |

1.13.1 |

Machine learning library |

| Keras |

2.2.4 |

High-level neural network API written in Python |

| SciPy |

1.10 |

Data management and computation |

| PythonSpeechFeatures |

0.6 |

Extraction of MFCCs and filterbank energies |

| Matplotlib |

3.0.0 |

Plotting library for generating figures |

| Flask |

1.0.2 |

RESTful request dispatching |

| NumPy |

2.0 |

Core library for scientific computing |

Table 2.

Number of recordings for each accent category.

Table 2.

Number of recordings for each accent category.

| Category |

Number of recordings |

| Native |

2200 |

| French |

2150 |

| German |

1650 |

| Mandarin |

2200 |

| Spanish |

2200 |

| Japanese |

2200 |

| Korean |

2200 |

| Thai |

2195 |

| Total |

16995 |

Table 3.

Tasks in the Hoosier database of native and nonnative Speech.

Table 3.

Tasks in the Hoosier database of native and nonnative Speech.

| Category |

Number of recordings |

| 160 |

Hearing in Noise Test for Children sentences |

| 10 |

Digit words |

| 48 |

Multi-syllabic Lexical Neighborhood Test words |

| 50 |

Northwestern University-Children’s Perception of Speech words |

| 100 |

Lexical Neighborhood Test words |

| 50 |

Lexical Neighborhood Sentence Test sentences |

| 40 |

Pediatric Speech Intelligibility sentences |

| 20 |

Pediatric Speech Intelligibility words |

| 339 |

Bamford-Kowal-Bench sentences |

| 150 |

Phonetically Balanced Kindergarten words |

| 72 |

Spondee words |

| 100 |

Word Intelligibility by Picture Identification words |

Table 4.

Tasks in the Hoosier database of native and nonnative Speech.

Table 4.

Tasks in the Hoosier database of native and nonnative Speech.

| MFCC: 28×28 |

MFCC: 64×48 |

MFCC: 128×48 |

| Iter. |

Test Acc. [%] |

Time [s] |

Test Acc. [%] |

Time [s] |

Test Acc. [%] |

Time [s] |

| 1 |

40.48 |

26 |

45.37 |

123 |

45.21 |

552 |

| 5 |

57.73 |

130 |

60.16 |

612 |

60.43 |

2734 |

| 10 |

64.21 |

261 |

65.54 |

1231 |

63.94 |

5467 |

| 15 |

67.67 |

391 |

69.45 |

1830 |

66.40 |

8251 |

| 20 |

70.29 |

522 |

70.72 |

2421 |

67.05 |

11024 |

| 30 |

73.89 |

781 |

74.27 |

3636 |

|

67.51 |

16591 |

Table 5.

Tasks in the Hoosier database of native and nonnative Speech.

Table 5.

Tasks in the Hoosier database of native and nonnative Speech.

| MFCC: 28×28 |

MFCC: 64×48 |

MFCC: 128×48 |

| Iter. |

Test Acc. [%] |

Time [s] |

Test Acc. [%] |

Time [s] |

Test Acc. [%] |

Time [s] |

| 1 |

34.21 |

26 |

38.51 |

122 |

38.29 |

552 |

| 5 |

63.48 |

130 |

71.62 |

615 |

68.43 |

2734 |

| 10 |

70.45 |

260 |

76.19 |

1231 |

77.13 |

5467 |

| 15 |

75.11 |

390 |

78.35 |

1846 |

80.84 |

8251 |

| 20 |

76.83 |

520 |

79.97 |

2459 |

81.94 |

11024 |

| 30 |

78.78 |

780 |

81.16 |

3690 |

82.86 |

16591 |

Table 6.

DTW and PoP features for the rule-based FIS decision.

Table 6.

DTW and PoP features for the rule-based FIS decision.

| DTW \ PoP |

Poor

(0-20) |

Mediocre (20-40) |

Average (40-60) |

Decent (60-80) |

Good

(80-100) |

Poor

(0-33) |

F |

F |

D |

D |

D |

Average

(34-66) |

C |

C |

B |

A |

A |

Good

(67-100) |

C |

B |

A |

A |

A |