Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

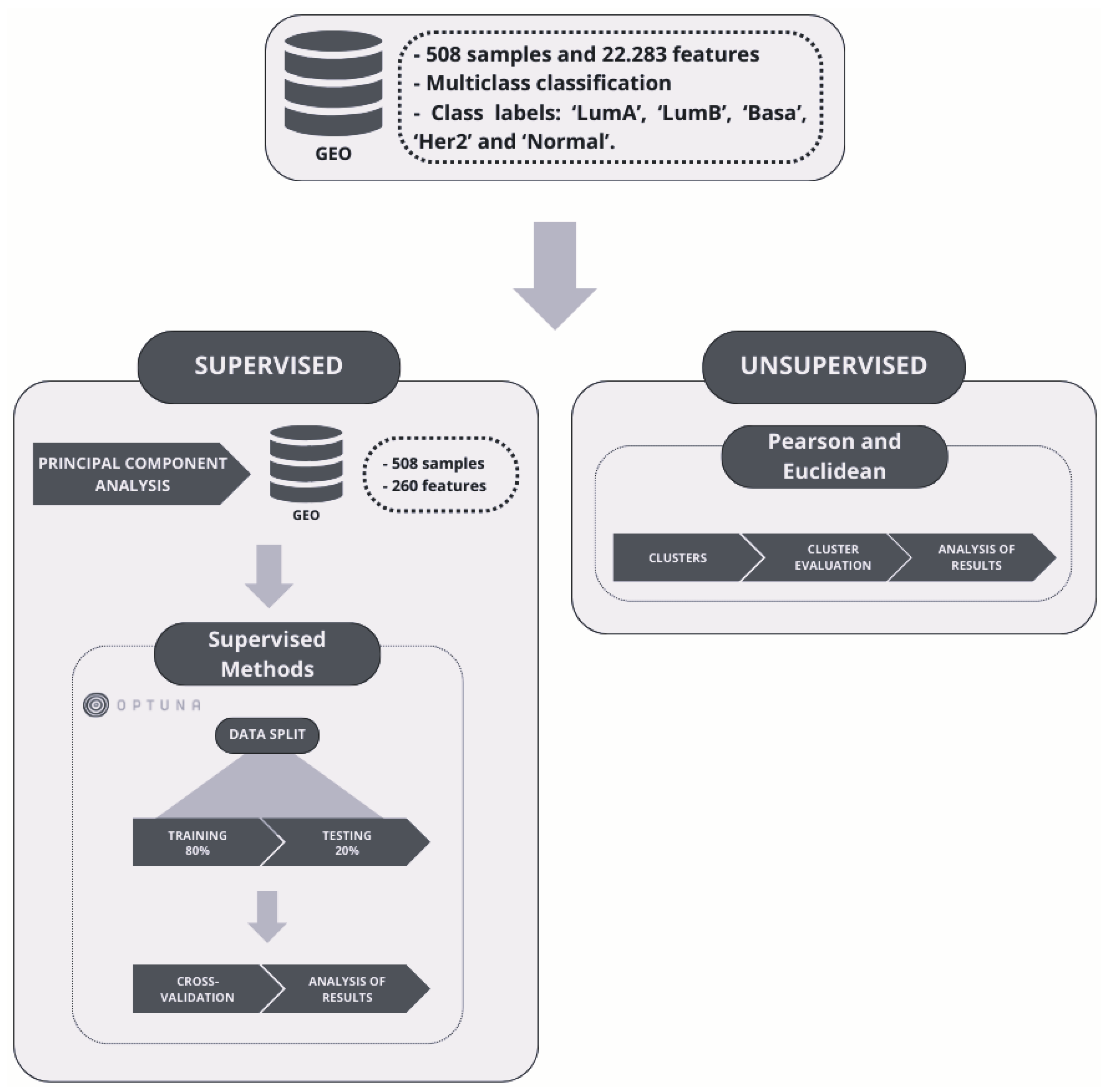

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. GEO Dataset Description

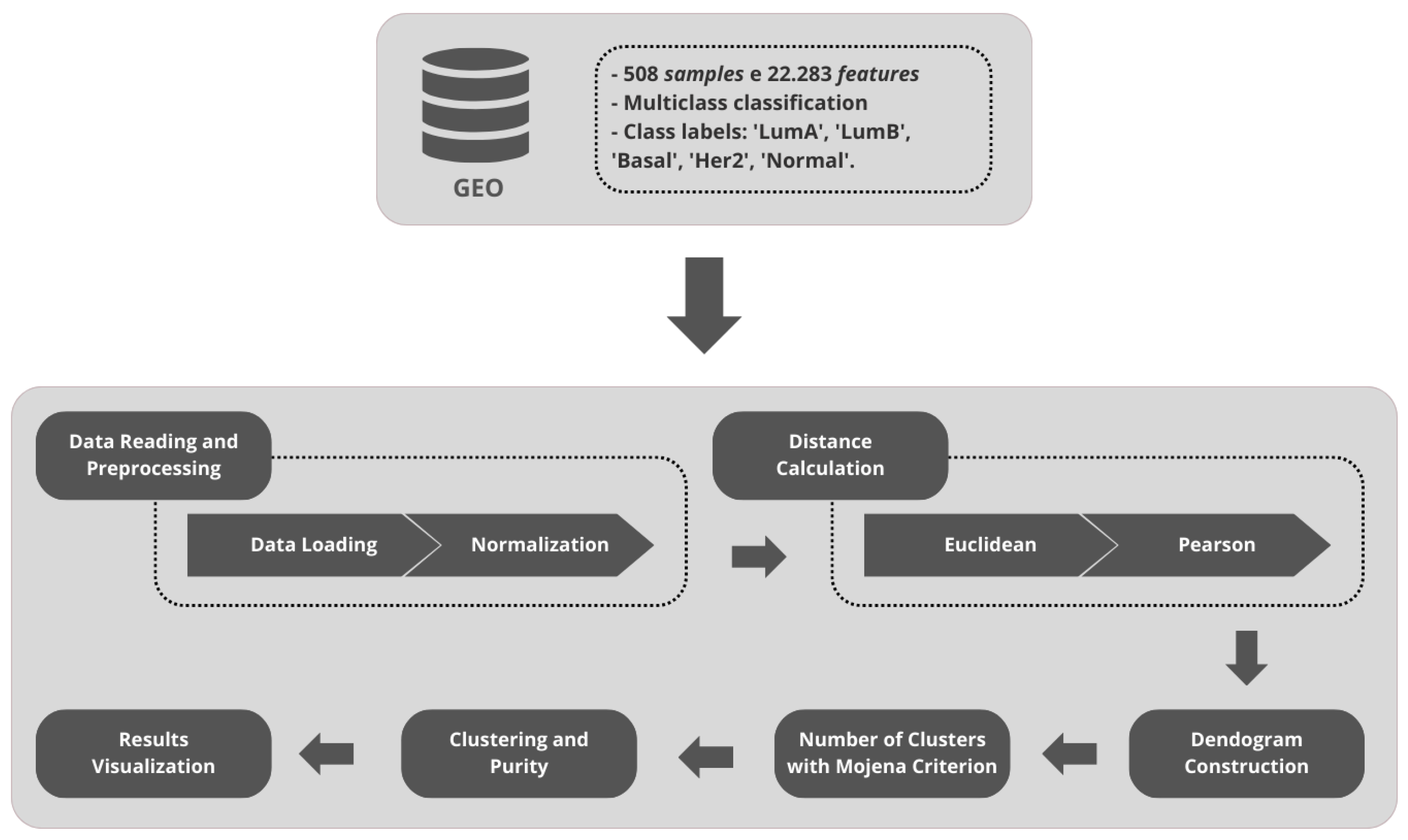

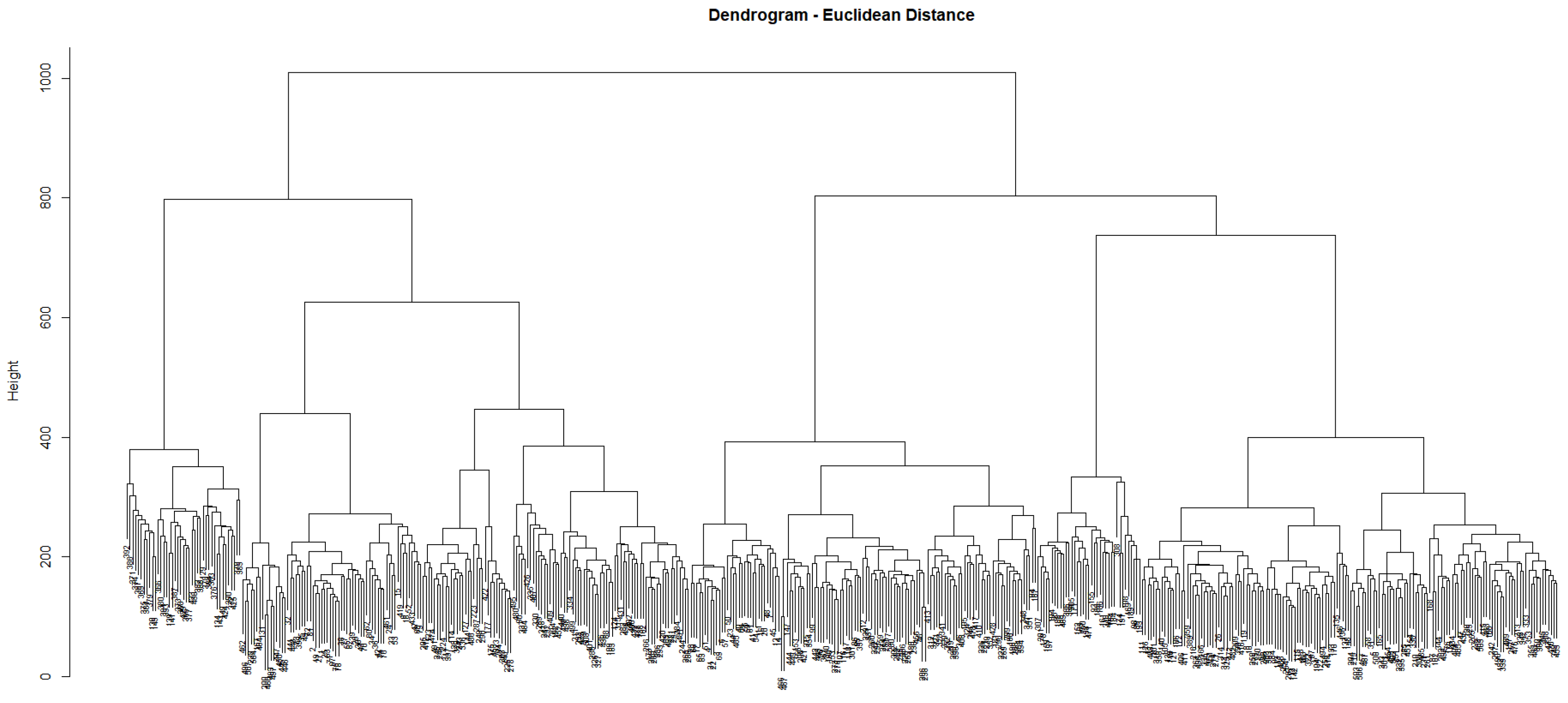

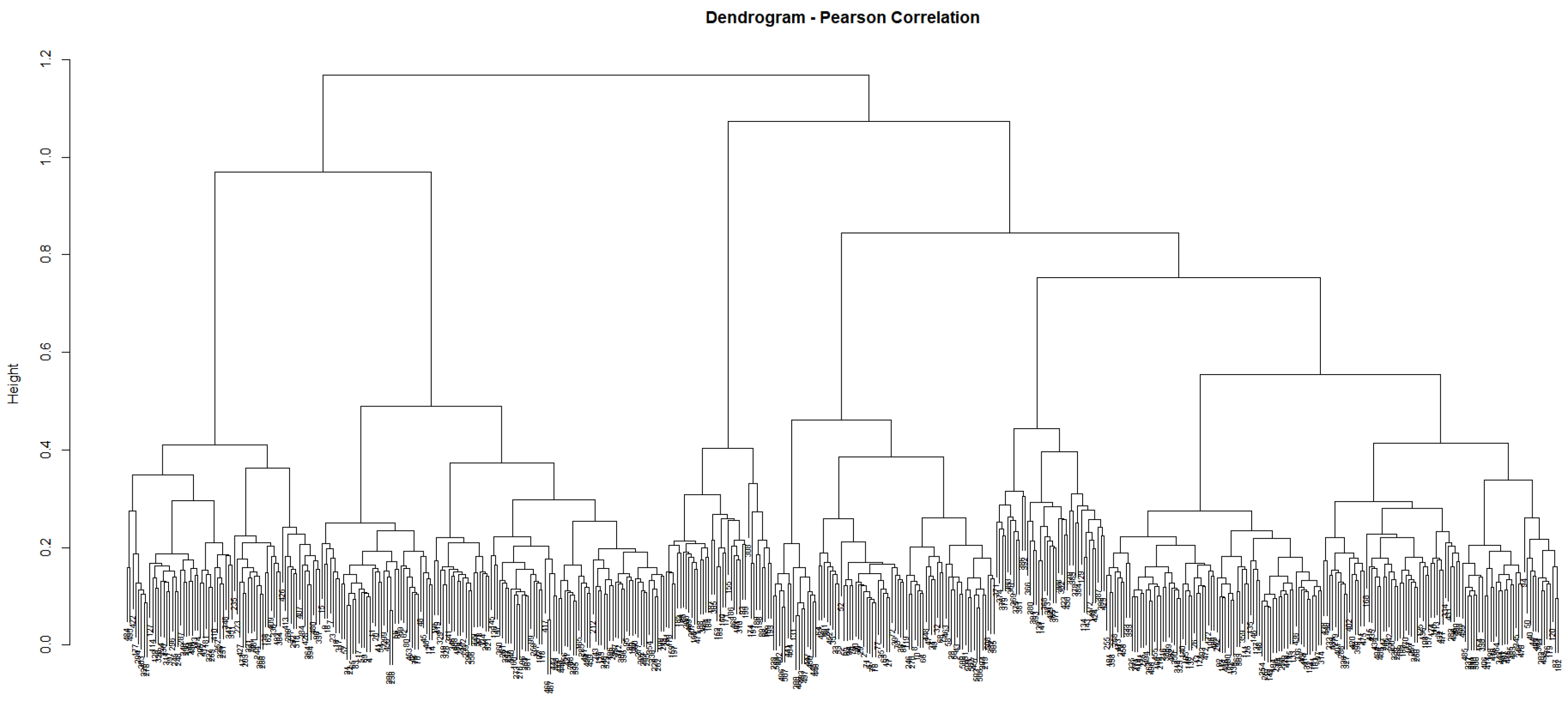

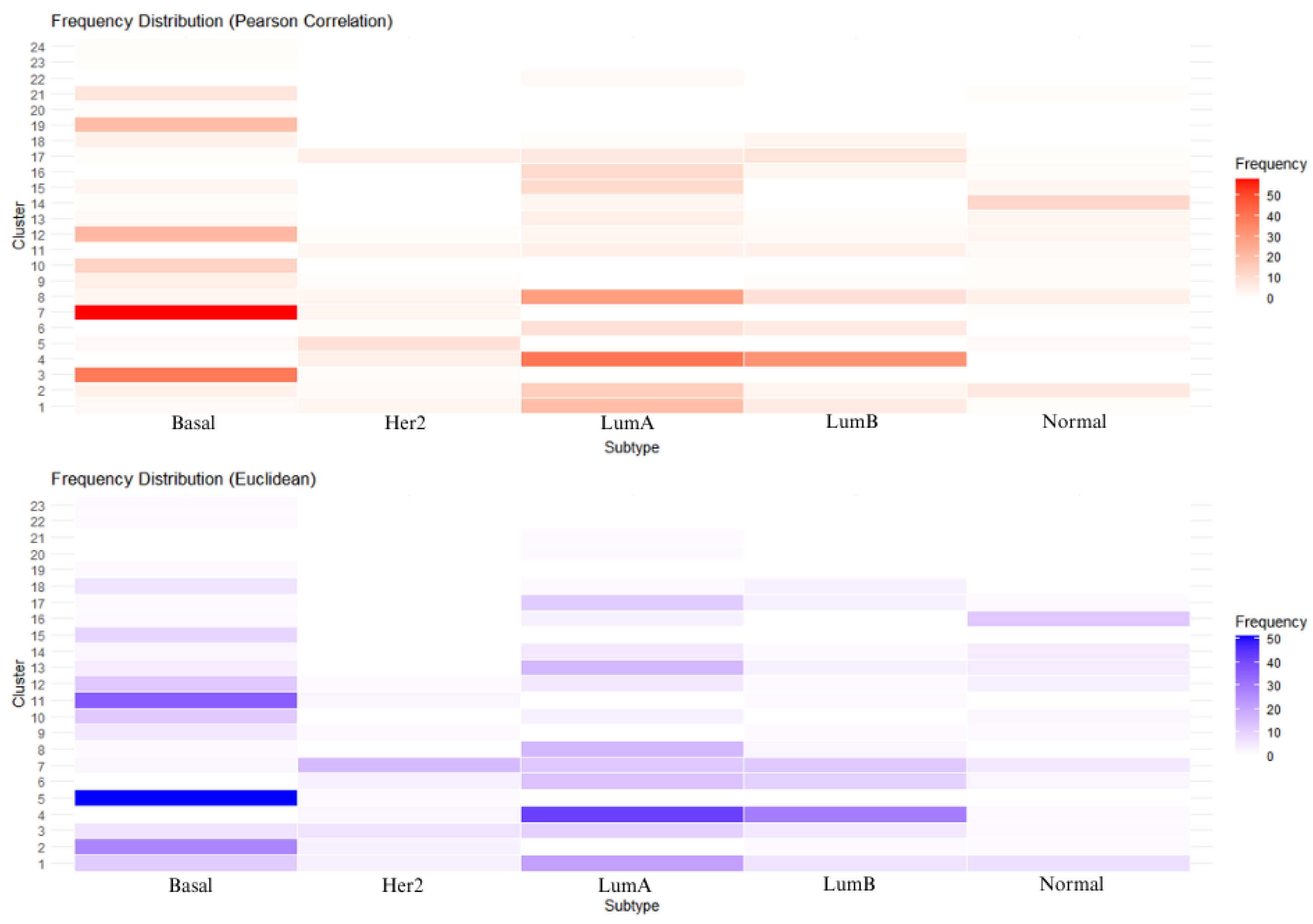

3.2. Unsupervised Approach: Hierarchical Clustering

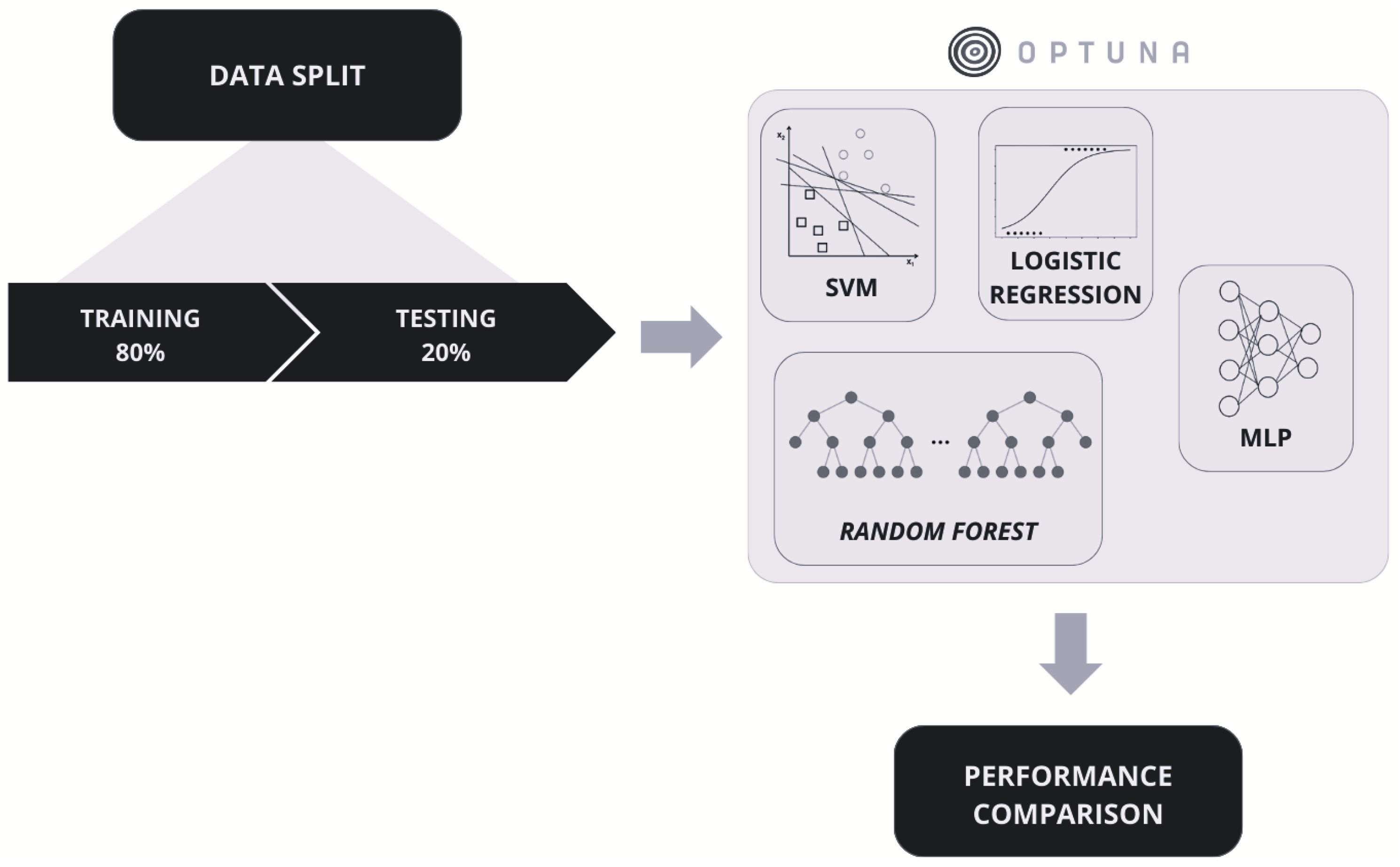

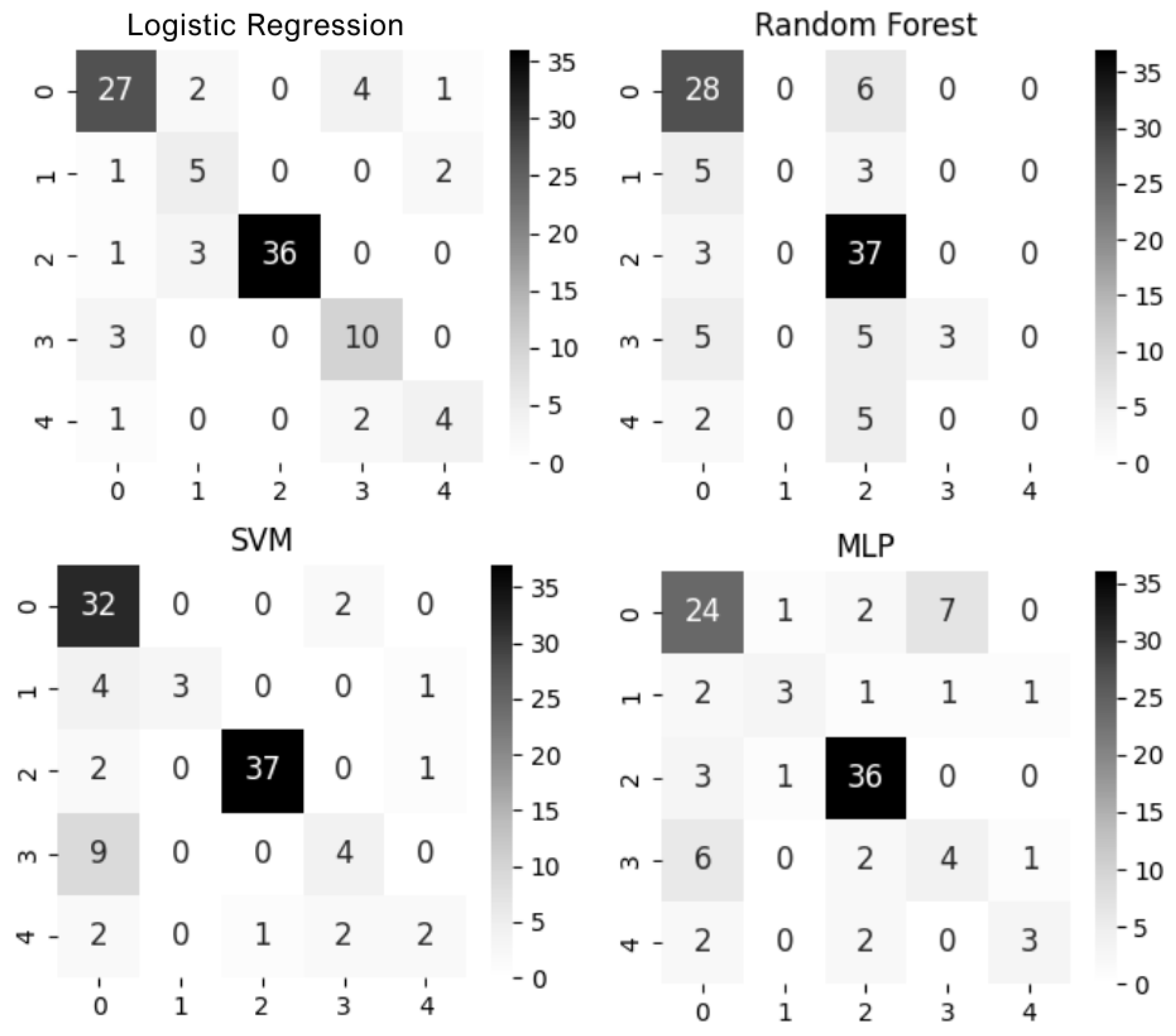

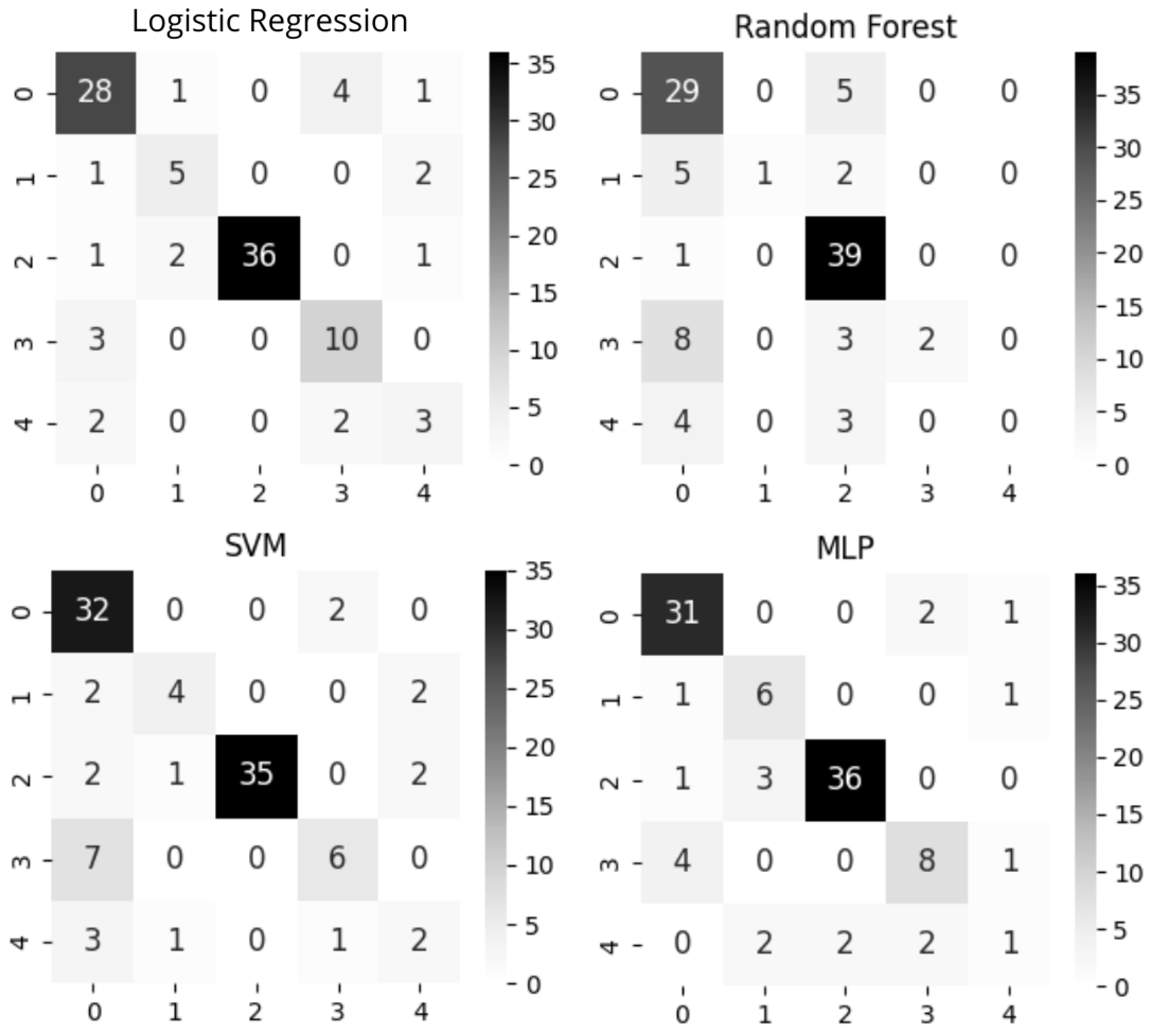

3.3. Supervised Learning Approaches

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

4. Results and Discussion

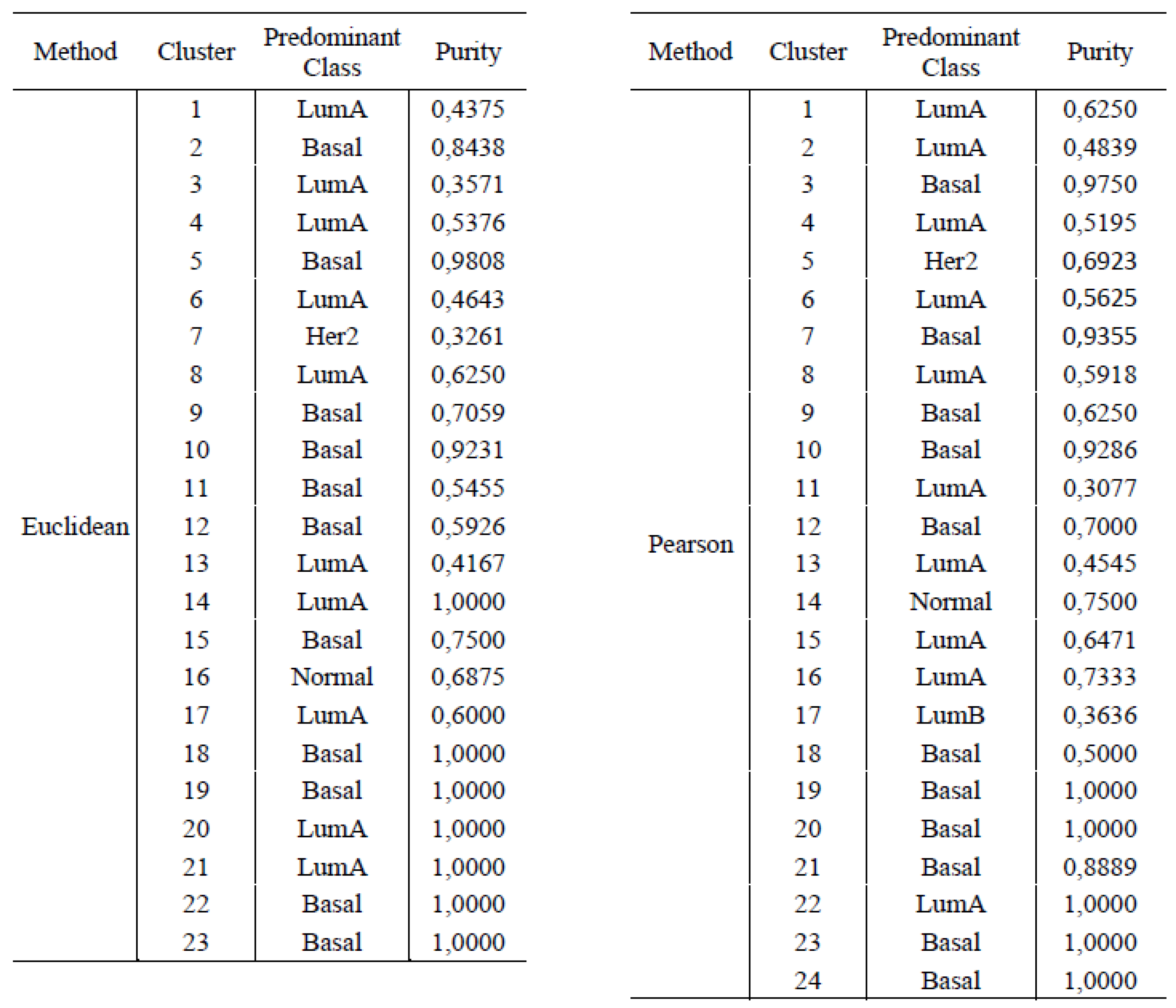

4.1. Unsupervised Learning

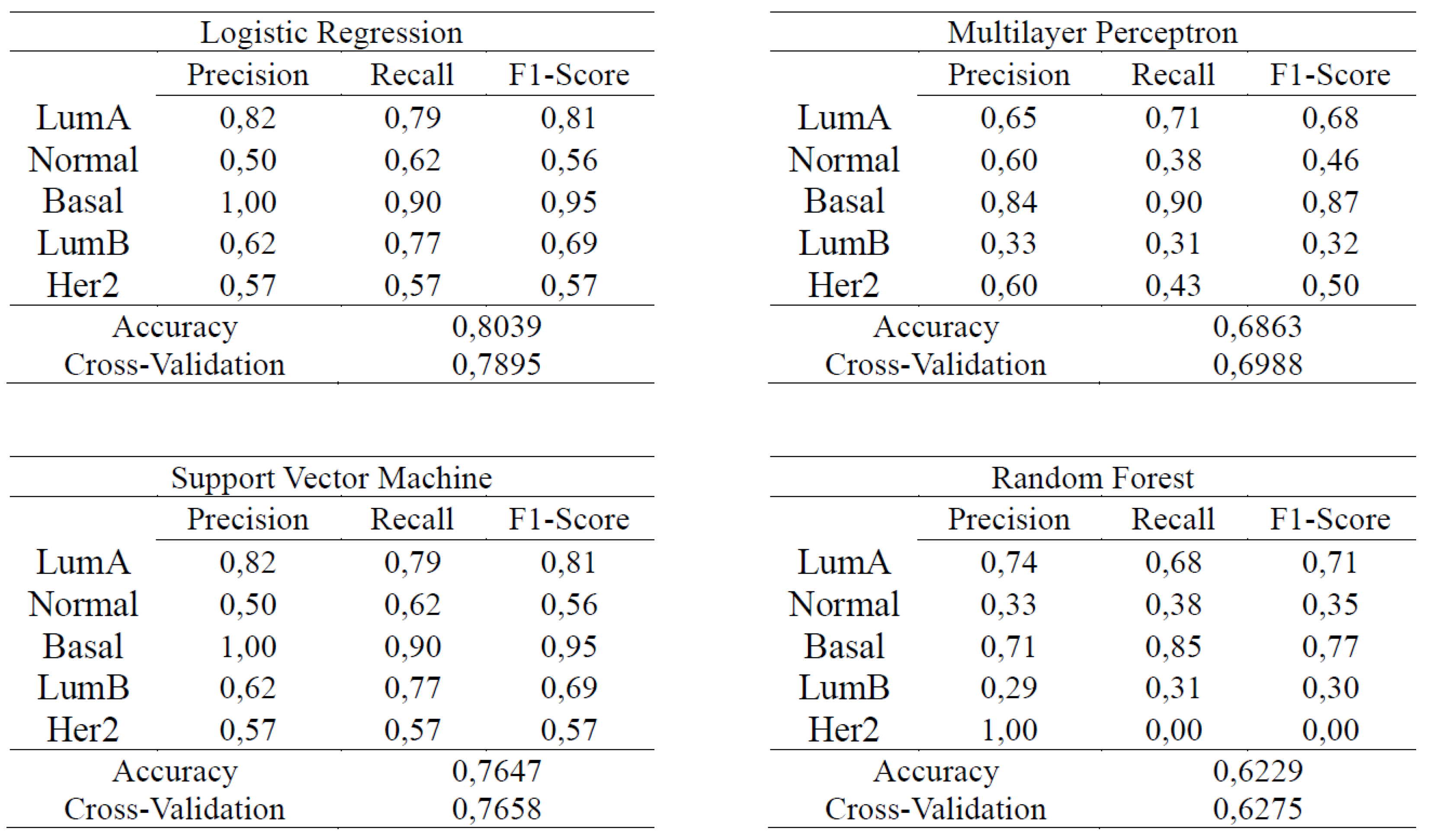

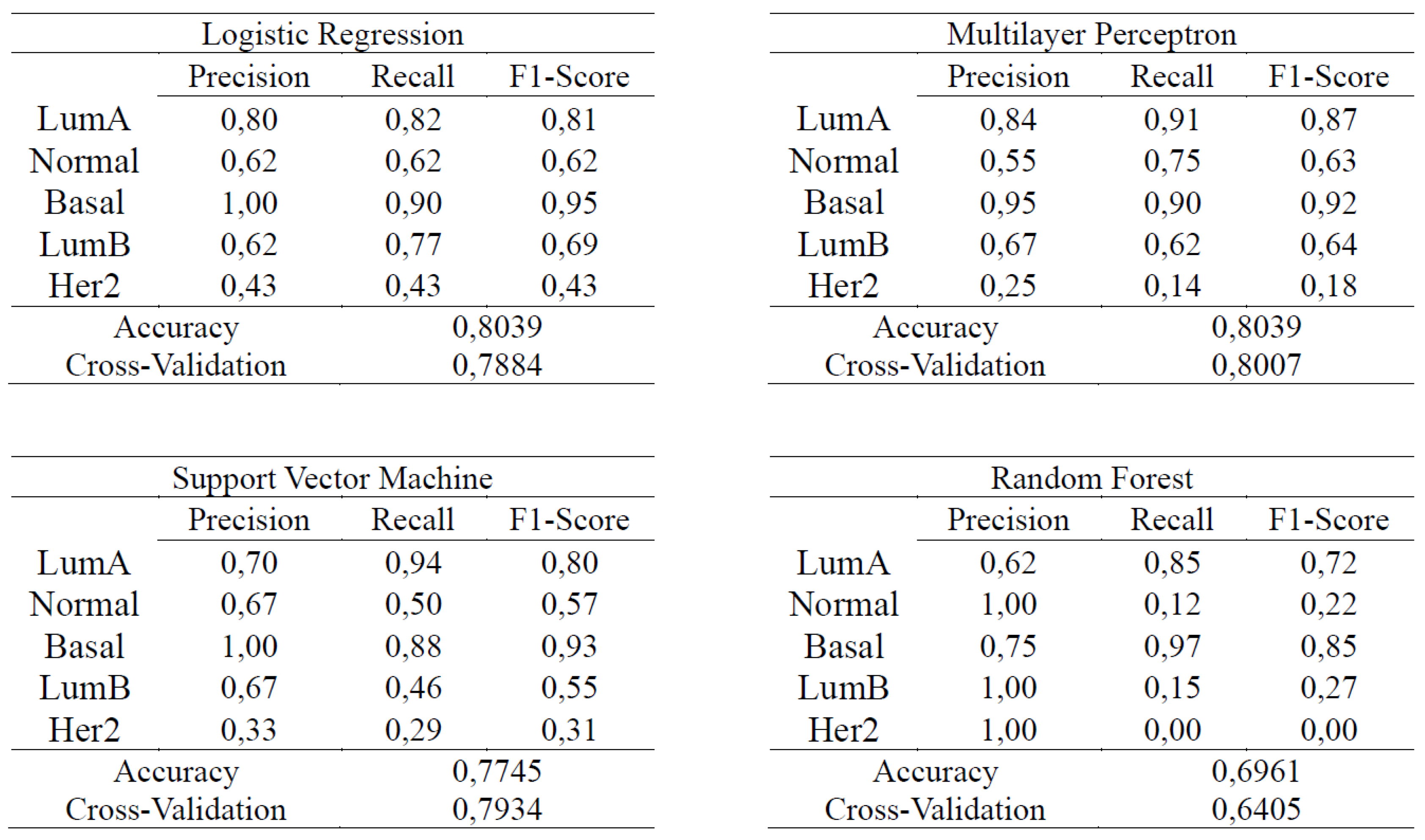

4.2. Supervised Learning

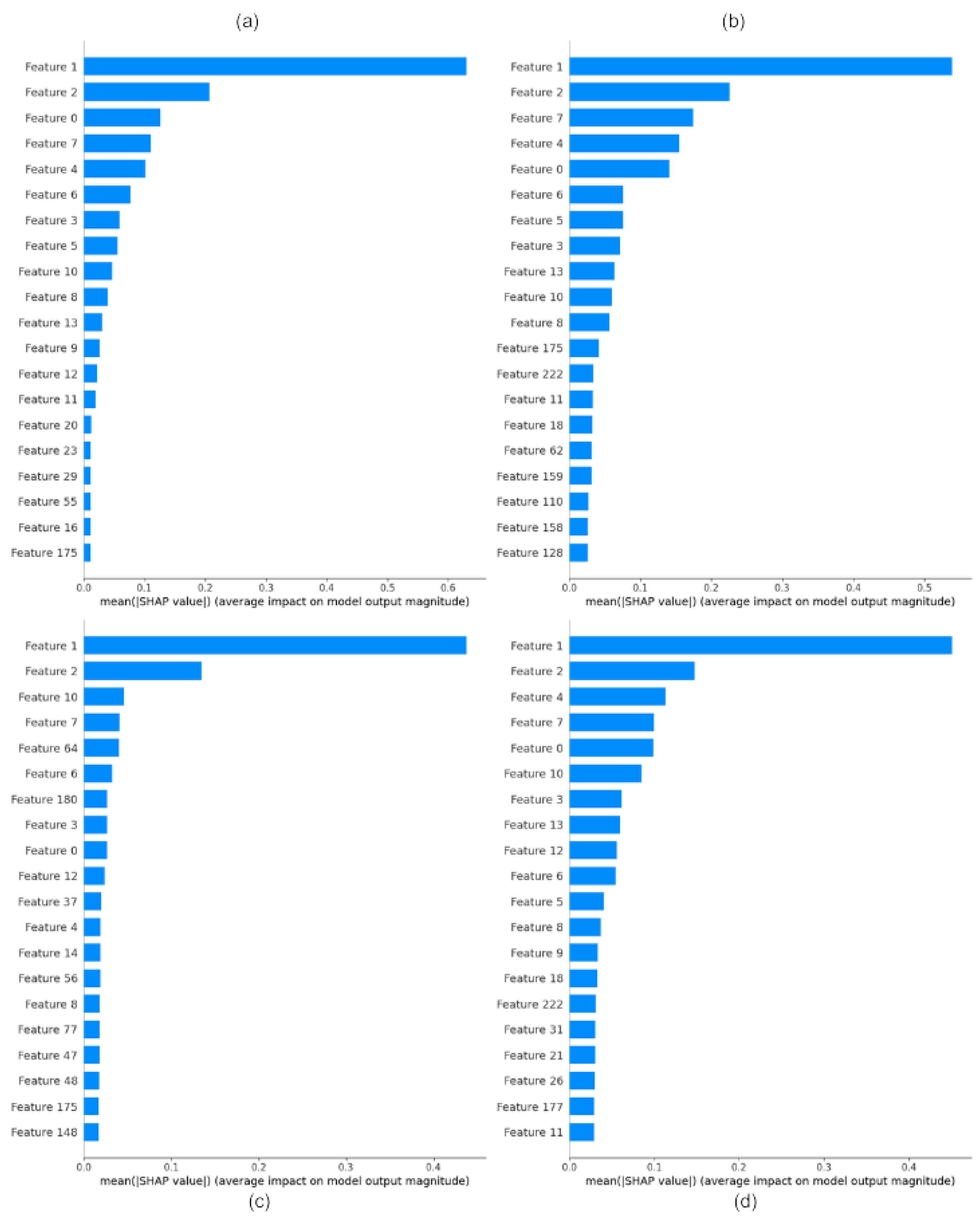

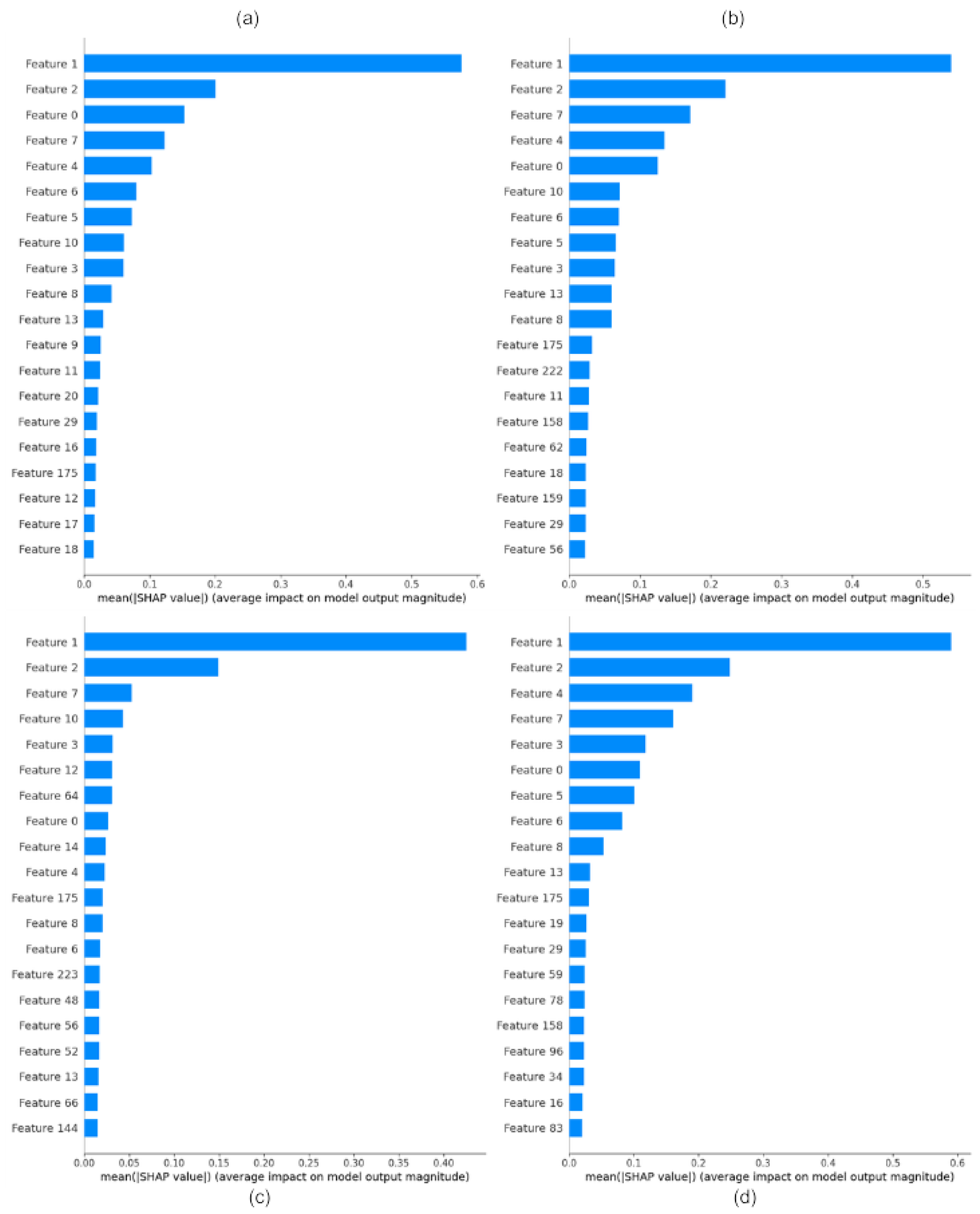

4.3. Feature Importance

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggarwal, C. C. Data classification. New York: Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Amrane, M., Oukid, S., Gagaoua, I., Ensari, T. Breast cancer classification using machine learning. In: 2018 Electric Electronics, Computer Science, Biomedical Engineerings’ Meeting (EBBT), pp. 1-4, 2018.

- Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T., Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, pp. 2623-2631, 2019.

- Amor, R. D., Colomer, A., Monteagudo, C., Naranjo, V. A deep embedded refined clustering approach for breast cancer distinction based on DNA methylation. Neural Computing and Applications, 1-13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, B. F., Rocha, A. M. A., & Pereira, A. I. Hybrid approaches to optimization and machine learning methods: a systematic literature review. Machine Learning, 113(7), 4055-4097, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J., Bardenet, R., Bengio, Y., Kégl, B. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Advances in neural information processing systems, 24, 2011.

- Bishop, C. M. Pattern recognition and machine learning. Springer Google Scholar, 2, 645-678, 2006.

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning. 45:5-32, 2001.

- Carlin, B. P., Louis, T. A. Bayesian methods for data analysis. 3rd edn. CRC press, Boca Raton, USA, 2008.

- Dianatinasab, M., Mohammadianpanah, M., Daneshi, N., Zare-Bandamiri, M., Rezaeianzadeh, A., Fararouei, M. Socioeconomic factors, health behavior, and late-stage diagnosis of breast cancer: considering the impact of delay in diagnosis. Clin. Breast Cancer, 18(3), 239–245, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Do, J. H., Choi, D. K. Clustering approaches to identifying gene expression patterns from DNA microarray data. Molecules and cells, 25(2), 279-288, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M., Stahl, D. Hierarchical clustering. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 3(4), 374-379, 2011.

- Gelman, A., Carlin, J. B., Stern, H. S., Rubin, D. B. Bayesian data analysis. 1st edn. Chapman and Hall/CRC, New York, EUA (1995).

- Haykin, S. S. Neural Networks and Learning Machines. New York: Pearson International Edition, 2009.

- Iparraguirre-Villanueva, O., Epifanía-Huerta, A., Torres-Ceclén, C., Ruiz-Alvarado, J., Cabanillas-Carbonel, M. Breast cancer prediction using machine learning models. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 14(2), 610–620, 2023.

- Jain, A. K., Murty, M. N., Flynn, P. J. Data clustering: a review. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 31(3), 264-323, 1999.

- Lemeshow, S., Hosmer, D. W. Logistic regression analysis: applications to ophthalmic research. American journal of ophthalmology, 147(5), 766-767, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Lin, I. H., Chen, D. T., Chang, Y. F., Lee, Y. L., Su, C. H., Cheng, C., ... Hsu, M. T. Hierarchical clustering of breast cancer methylomes revealed differentially methylated and expressed breast cancer genes. PloS one, 10(2), e0118453, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. M., Lee, S-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 2017. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.07874.

- Milligan G.W., Cooper M.C. An Examination of Procedures for Determining the Number of Clusters in a Data Set. Psychometrika. 50(2):159-179, 985. [CrossRef]

- Mojena, R. Hierarchical grouping methods and stopping rules: an evaluation, The Computer Journal, 20(4):359–363, 1977. [CrossRef]

- Perou, C. M., et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 406(6797), 747-752, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J. R. Learning decision tree classifiers. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 28(1), 71-72, 1996.

- Rabiei, R., M., A. S., Sohrabei, S., Esmaeili, M., and Atashi, A. Prediction of breast cancer using machine learning approaches. J Biomed Phys Eng, 12(3), 297–308, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rencher, A. C. Methods of Multivariate Analysis. Wiley, 2002. (Wiley series in probality and mathematical statistics). IISB 0-471-41889-7.

- Shieh, S. H., Hsieh, V. C. R., Liu, S. H., Chien, C. R., Lin, C. C., Wu, T. N. Delayed time from first medical visit to diagnosis for breast cancer patients in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc., 113(10), 696–703, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Liu, Z. P. Discovering explainable biomarkers for breast cancer anti-PD1 response via network Shapley value analysis. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 257, 108481, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tan, P. N., Steinbach, M., Kumar, V. Introduction to data mining. 2nd edn. Pearson Education, New York, 2018.

- Tewari, Y., Ujjwal, E., Kumar, L. Breast cancer classification using machine learning. In 2nd International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), IEEE, Greater Noida, India, 01-04, 2022.

- Valentin, A. B. M., Bressan, G. M., Lizzi, E. A. S., Canuto Jr., L. Optimized Learning Methods for Classifying Breast Cancer Subtypes Based on Gene Expression Data. Applied Mathematics & Information Sciences, 19(4), 819–830, 2025.

- World Health Organization. Global breast cancer initiative implementation framework: assessing, strengthening, and scaling-up of services for the early detection and management of breast cancer. World Health Organization, 2023.

- Yue, W., Wang, Z., Chen, H., Payne, A., Liu, X. Machine learning with applications in breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Designs, 2(2), 13, 2018. [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).