1. Introduction

In recent years, the Caribbean has experienced unprecedented accumulations of Sargassum seaweed, disrupting coastal economies and ecosystems [

1,

2,

3]. Beyond its negative impacts such as beach fouling, habitat loss, and economic burdens Sargassum represents a potentially valuable biomass for circular economy solutions, including the production of liquid biofertilizers [

4,

5]. Prior investigations demonstrate that Sargassum is rich in nitrogen, potassium, and micronutrients, which are beneficial for plant growth [

6,

7]. However, the same macroalgae can accumulate heavy metals in the marine environment, raising food safety and ecological concerns [

3,

8].

Recent research on Sargassum-derived biofertilizers has focused primarily on heavy metal and nutrient concentrations and agronomic efficacy [

9]. However, biosecurity factors such as microbial safety and ecotoxicological behavior must also be evaluated to ensure safe adoption in agriculture. In this sense, ecotoxicological assays are especially critical for verifying the absence of phytotoxic substances and gauging the potential impacts on plant growth [

10,

11]. Despite these efforts, little attention has been given to the microbiological composition of these biofertilizers and how it influences their safety and effectiveness. Understanding the microbial communities present in biofertilizers is essential, as beneficial microbes can enhance soil health and plant growth, whereas potential pathogens could pose risks to agricultural systems. This study builds on previous research that characterized the chemical composition of Sargassum and its liquid biofertilizer agronomic performance, shifting focus to microbiological quality and ecotoxicological safety in Sargassum-based liquid biofertilizer produced by the Banelino Association in the Dominican Republic.

Moreover, genomic analysis of biofertilizer samples is becoming essential for accurately characterizing the microbial communities present in these bioproducts [

12]. The recent decades' widespread use of DNA sequencing has played a pivotal role in accurately understanding microbial ecology and detecting specific functional groups within microbial populations [

13]. DNA barcoding utilizes standardized species-specific genomic regions (DNA barcodes) to generate vast DNA libraries, aiding in identifying unknown specimens [

14]. This methodology is crucial, particularly for bacteria with unusual phenotypic profiles, slow-growing or uncultivable bacteria, and culture-negative infections [

15]. In the case of biofertilizers, metagenomic approaches such as 16S rRNA sequencing enable the identification of microbial communities that contribute to nutrient cycling and plant growth promotion, while also verifying the absence of potentially harmful microorganisms. An excellent example of this in bacteria is the 16S ribosomal RNA [

16].

Specifically, we compare (i) a Sargassum-Based Liquid Biofertilizer (SBLB-INTEC) and (ii) a conventional biofertilizer (LB-BANELINO) lacking Sargassum. The objectives are to (1) assess microbial diversity and potential pathogenic organisms and (2) evaluate phytotoxic effects using Lactuca sativa germination assays. By integrating microbiological characterization with ecotoxicological testing, this study provides a holistic perspective on the biosecurity of Sargassum-based biofertilizers, offering valuable insights for farmers, researchers, and policymakers interested in sustainable coastal resource utilization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Production of the Biofertilizers in the Banelino Association in the Dominican Republic

Two liquid biofertilizers were produced at the Banelino Association facility in Montecristi, Dominican Republic (figure 1), an organization uniting small-scale banana producers focused on sustainable organic farming.

Figure 1.

Locations in the Dominican Republic: the Bioferment plant of the BANELINO Association in the Northeast (blue point) and the Sargassum sampling place in Punta Cana (red point). Source: Google Earth.

Figure 1.

Locations in the Dominican Republic: the Bioferment plant of the BANELINO Association in the Northeast (blue point) and the Sargassum sampling place in Punta Cana (red point). Source: Google Earth.

SBLB-INTEC: Sargassum was collected from Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, in May 2024, and mixed with molasses, baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), yogurt, milk, and water from the Yaque del Norte River (pre-filtered to remove debris). The mixture was fermented anaerobically in a 1000 L static reactor for approximately 30 days.

LB-BANELINO: This conventional biofertilizer, lacking Sargassum, combined molasses with a “mother culture” of forest mulch, rice bran, and grass, fermented anaerobically in a 1000 L plastic fermenter for 30 days.

Note: The details of how the detailed chemical composition of the

Sargassum was determined and used in the SBLB-INTEC production are presented in a previous publication [

17].

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 below show the results of the chemical-physical analyses, metals, heavy metals and biomolecules determined for both biofertilizers following the same methodology used in the previous article to this research [

17]. In this research, we focused on microbiological and biosecurity parameters.

2.2. Microbiological Composition Analysis

2.2.1. DNA Extraction

Biofertilizer samples were pre-filtered using a vacuum-assisted system with a 1.6 µm cellulose membrane to remove coarse particles, followed by a 0.2 µm membrane to retain microbes. Membranes were stored in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer at -20°C until processing. Metagenomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy® PowerWater Kit (Qiagen, Germany) per the manufacturer’s instructions after thawing at room temperature.

2.2.2. Sequencing and Assembly

The concentration and quality of the extracted DNA were evaluated spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). DNA integrity, purity, fragment size, and concentration were further assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis. The universal primer set 341F (5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACNNNGGGGGTATCTAAT-3′) were used to amplify the V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. Following 16S rRNA library preparation, library quality was assessed on a Qubit® 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. The libraries were then sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating 250 bp paired-end reads at Novogene (Beijing, China).

2.2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

The microbiome analysis used two groups (BB, and BSI) with the 16S amplicon paired-end sequenced data. Each group was sequenced in triplicate samples, and their Quality Control was analyzed using FastQC [

40] and reads that had a Phred score smaller than 20 were removed using Trimmomatic [

41] so the resulting files could be used for the next steps.

From the obtained sequenced amplicon data, the reads were compared with the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Release 11.5 using the kraken2 software [

42] for taxonomic classification. The taxonomic reports were converted into “mpa” file format and merged using the Krakentools [

43] according to each group compared. The file was prepared for microbiome data analysis using the microeco package [

44] from R language (version R-4.4.2) to perform diversity analysis and plot the results [

45]. 16S raw data were deposited in NCBI under the link:

https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1237349?reviewer=hfn4upgclrlc7u9b4819oiofog

2.3. Ecotoxicological Assay

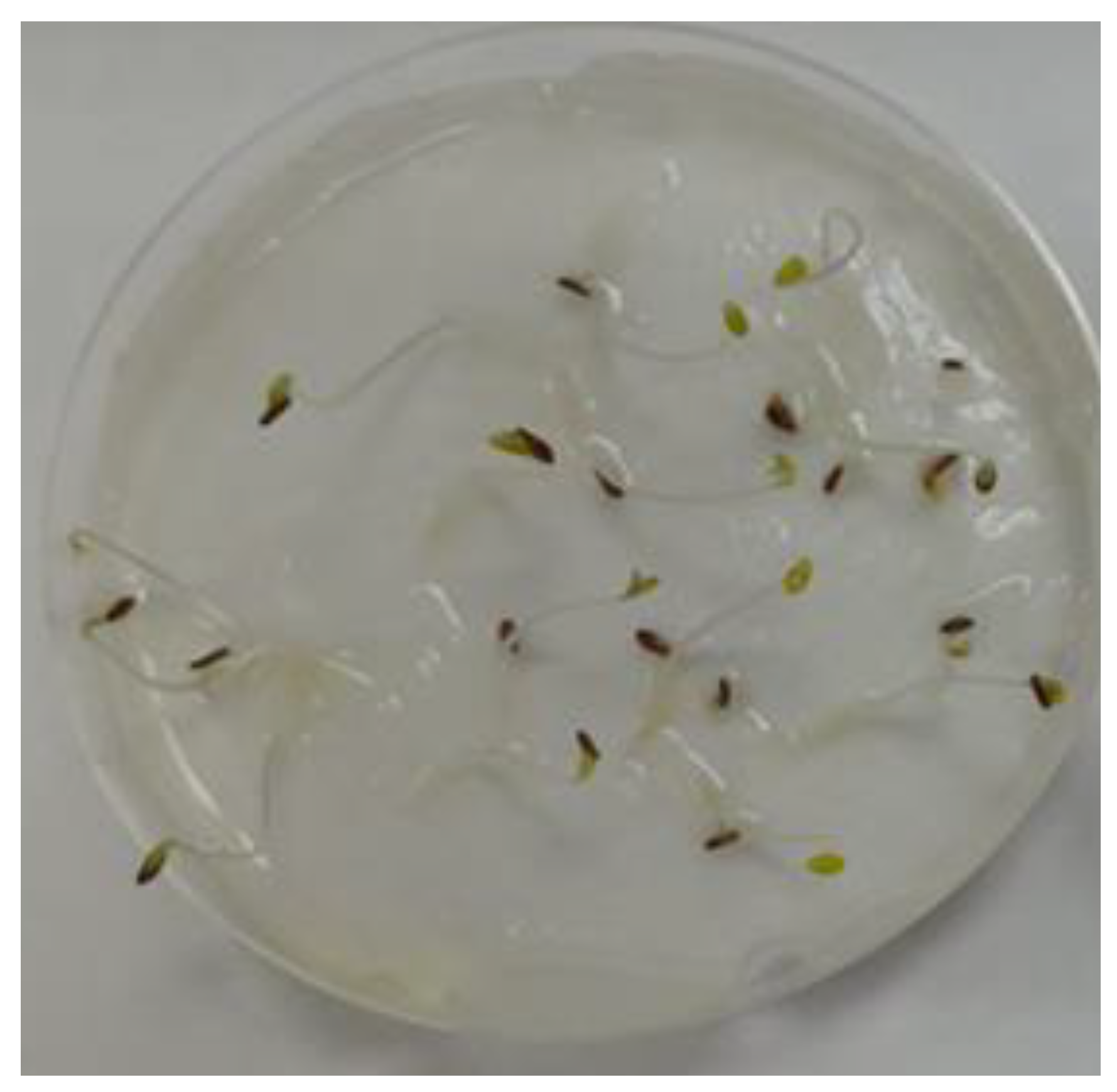

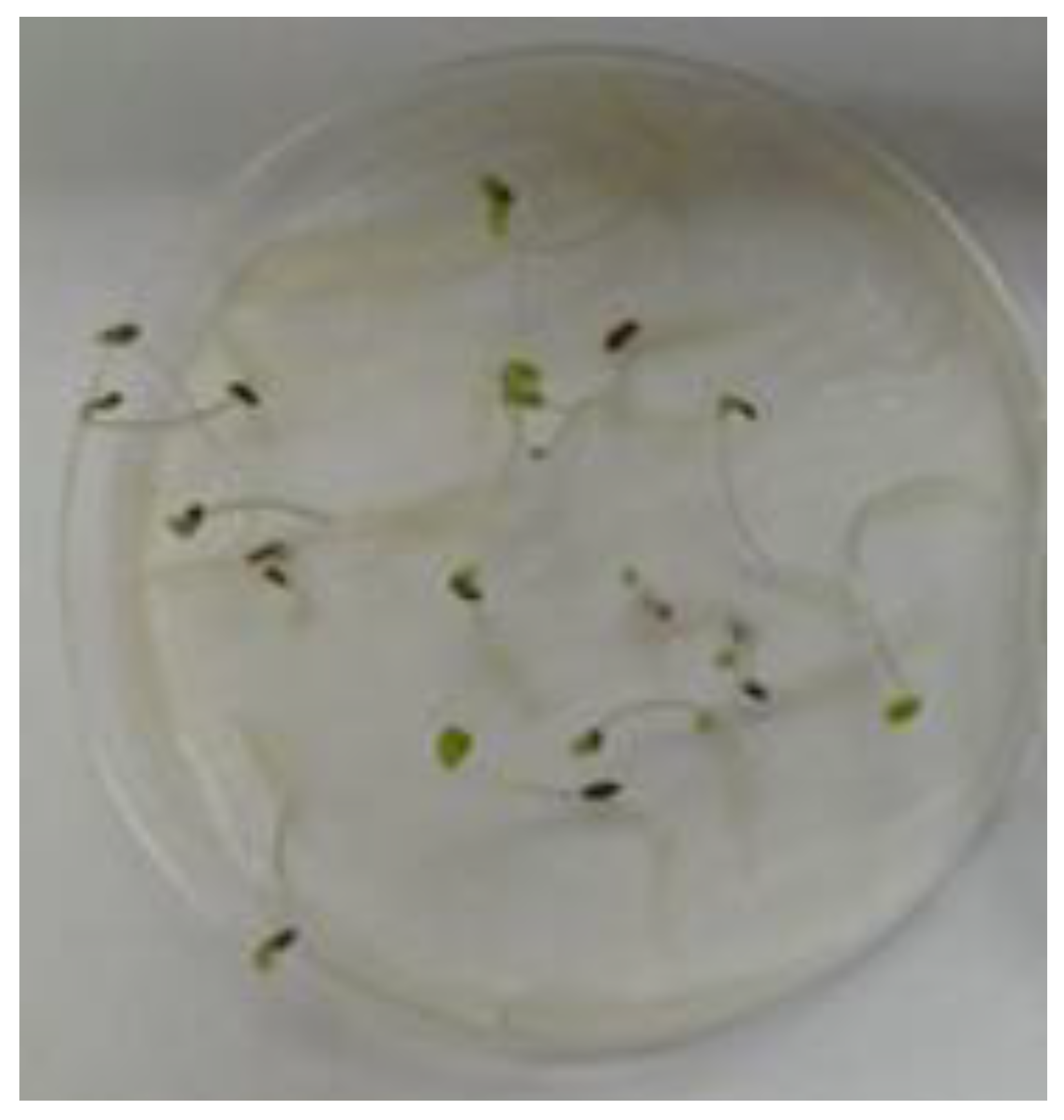

2.3.1. Germination Tests with Lactuca Sativa

Lactuca sativa seeds (var. Gentilina, ≥85% germination rate) were placed on Whatman

® No. 3 filter paper (90 mm) in 100 mm Petri dishes and treated with 5 mL of biofertilizer dilutions (100%, 50%, 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, 3.12%, 0%) in distilled water. The control used 5 mL distilled water (0%). Dishes were sealed with Parafilm

® and incubated in darkness at 22 ± 2°C for 5 days. This species was chosen for its sensitivity to contaminants and established use in phytotoxicity testing [

10,

11,

46,

47]. This species provides a reliable indicator of potential phytotoxic effects caused by biofertilizers. Serial dilutions followed [

48] modified by [

46], with each treatment in triplicate (20 seeds/dish). Parallel tests adjusted pH to 7.0 to assess acidity effects. The pH can be a critical factor influencing germination outcomes. High acidity can cause osmotic stress and impair nutrient availability [

49], negatively impacting seed germination and root development.

At the end of the exposure period, the number of germinated seeds was quantified, and the elongation of the radicle was measured. Using the equations described by [

47], the relative percentage of germination (RG) and the relative percentage of radicle growth (RRG) were determined. From these values, the germination indexes (GI) corresponding to each concentration were calculated:

2.3.2. Lactuca sativa with pH adjustment.

To evaluate the phytotoxicity of the biofertilizers, the No Observed Effect Concentration (NOEC) and the Lowest Observed Effect Concentration (LOEC) values were determined using a germination bioassay with Lactuca sativa. Seed germination and root elongation were analyzed to identify the lowest biofertilizer concentration at which no significant inhibitory effect was observed (NOEC) and the minimum concentration that caused a statistically significant reduction in germination or growth compared to the control (LOEC).

The NOEC and LOEC values were obtained using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test, comparing treated groups to the control (p < 0.05). The concentrations tested ranged from 3.12% to 100%, and adjustments to pH were applied in a parallel experiment to evaluate the impact of acidity on phytotoxicity. These statistical analyses enabled the identification of a safe biofertilizer application threshold, ensuring that seed germination and early plant growth are not adversely affected.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Microbiological Composition of Biofertilizers

Metagenomic analysis (16S rRNA) revealed distinct archaeal communities in SBLB-INTEC and LB-BANELINO biofertilizers (

Table 4). This information reveals key differences between the two biofertilizers, particularly in the presence of Thaumarchaeota

, which was found exclusively in SBLB-INTEC, suggesting a stronger potential for ammonia oxidation and nitrogen cycling. In contrast, the presence of Methanomicrobia in LB-BANELINO indicates a higher contribution to methanogenesis, possibly due to differences in organic matter degradation pathways between both formulations.

The Phylum Thaumarchaeota includes organisms known for their role in ammonia oxidation in the soil, transforming it into nitrite and nitric oxide. This process, which is the first and limiting step of nitrification, highlights its key role in the nitrogen cycle [

50]. On the other hand, the Phylum Euryarchaeota, contains the alkaline phosphatases PhoD and PhoX, responsible for hydrolyzing organic phosphorus in the soil. Previous studies have shown that Euryarchaeota isolated from agricultural, forest, and grassland soils express the phoD and phoX genes, which are involved in phosphorus hydrolysis near plant roots [

51].

Classes such as Methanomicrobia and Methanobacteria are commonly associated with methanogenesis, indicating potential roles in the anaerobic degradation of organic matter [

52]. Genera like

Methanocorpusculum (only in the LB-BANELINO) and

Methanobrevibacter further underscore active methanogenic processes, while

Nitrososphaera (only in the SBLB-INTEC) points to ammonia-oxidizing capabilities. Collectively, these archaea can influence nutrient cycling and fermentation dynamics, providing insights into how biofertilizers may enhance soil fertility and microbial activity [

53,

54].

Overall, the archaeal communities present in both biofertilizers indicate their potential to enhance soil fertility by contributing to essential biogeochemical cycles, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus transformations [

55]. The differences in the microbial composition between the two biofertilizers suggest that SBLB-INTEC may be more effective in nitrogen cycling, while LB-BANELINO could play a more significant role in phosphorus mobilization. Further studies are recommended to evaluate the long-term impact of these microbial communities on plant growth and soil health under field conditions.

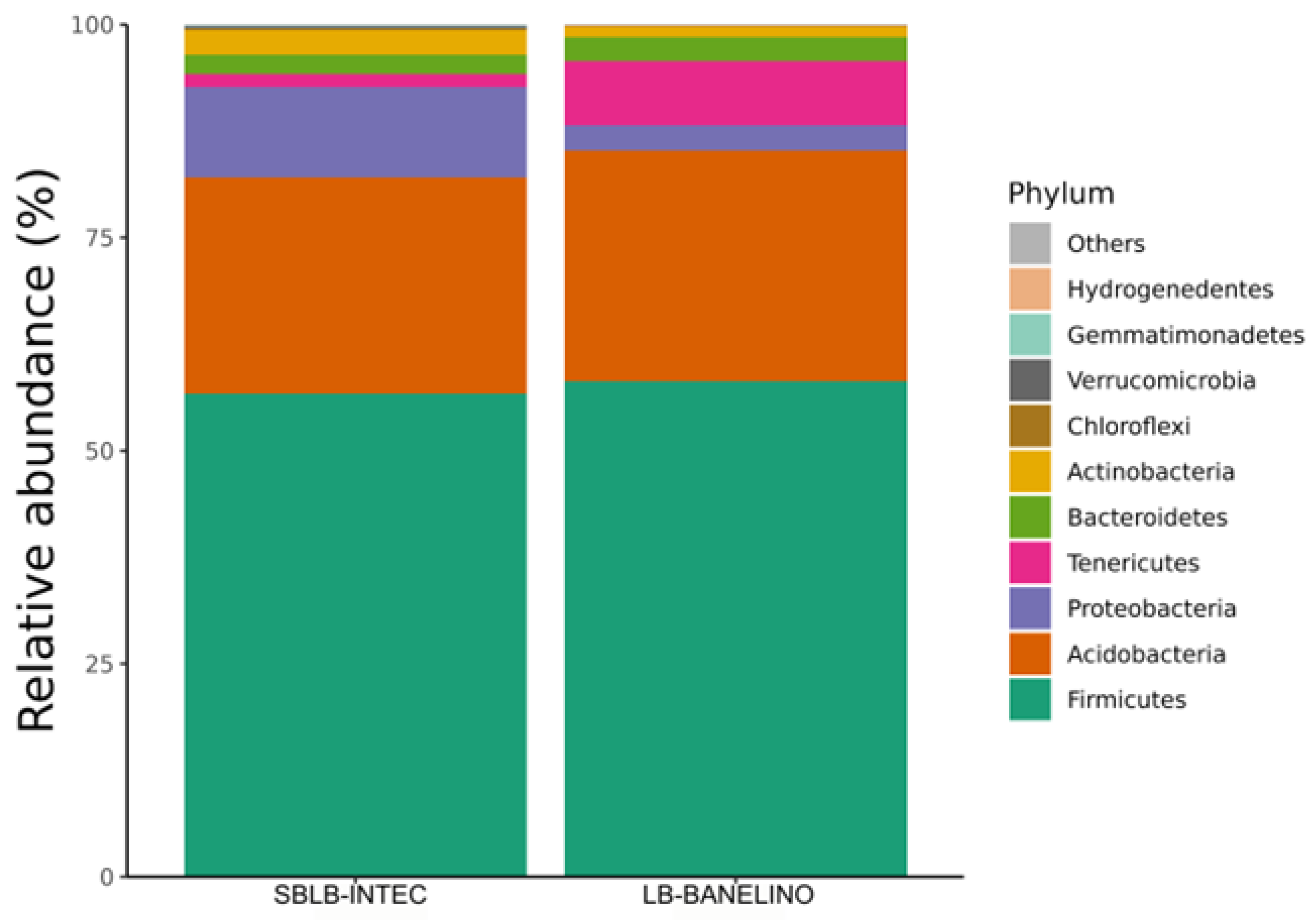

Table 5 shows the presence or absence of bacterial taxa in SBLB-INTEC and LB-BANELINO biofertilizers. The results indicate that both biofertilizers harbor a diverse set of bacterial phyla, with Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, Proteobacteria, Tenericutes, and Bacteroidetes detected in both samples.

The bacterial community composition of the biofertilizers SBLB-INTEC and LB-BANELINO includes Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, and Proteobacteria, which together account for most of the relative abundance observed in both formulations (

Figure 2). In this sense, Firmicutes represents the most abundant phylum in both biofertilizers. This phylum is widely recognized for its role in organic matter decomposition, stress tolerance, and plant growth promotion. Certain species within Firmicutes, such as

Bacillus spp., are known to produce antimicrobial compounds that suppress soil pathogens, as well as exopolysaccharides that help plants withstand drought and salinity stress [

56,

57]. The high relative abundance of Firmicutes in both biofertilizers suggests their potential role in enhancing soil health and crop resilience.

On the other hand, Acidobacteria is the second most represented phylum, supporting nutrient cycling and organic matter mineralization. Members of Acidobacteria are known for their ability to break down complex polysaccharides and organic acids, facilitating the release of nutrients that can be absorbed by plants [

58]. Their presence in both biofertilizers indicates that these microbial products may contribute to soil microbial diversity and organic matter decomposition.

Also, Proteobacteria are key contributors to nitrogen cycling, with many of its members participating in biological nitrogen fixation, denitrification, and ammonification. The presence of nitrogen-fixing Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria within this phylum suggests that these biofertilizers may enhance soil fertility and nutrient availability for crops [

59]. The role of Proteobacteria in phosphate solubilization is also relevant, as it can improve phosphorus uptake efficiency in plants [

60].

Other bacterial phyla, such as Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Tenericutes, and Chloroflexi were detected, though at lower relative abundances. These groups contribute to soil organic matter degradation, secondary metabolite production, and microbial interactions that enhance the functionality of biofertilizers. The presence of Hydrogenedentes and Verrucomicrobia in minor proportions also suggests potential specialized ecological roles in carbon cycling and plant-microbe interactions [

61].

Then, the relative abundance patterns observed in

Figure 2 indicate that both biofertilizers harbor diverse and functionally relevant bacterial communities. The dominance of Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, and Proteobacteria highlights their potential roles in enhancing soil structure, nutrient cycling, and plant growth promotion.

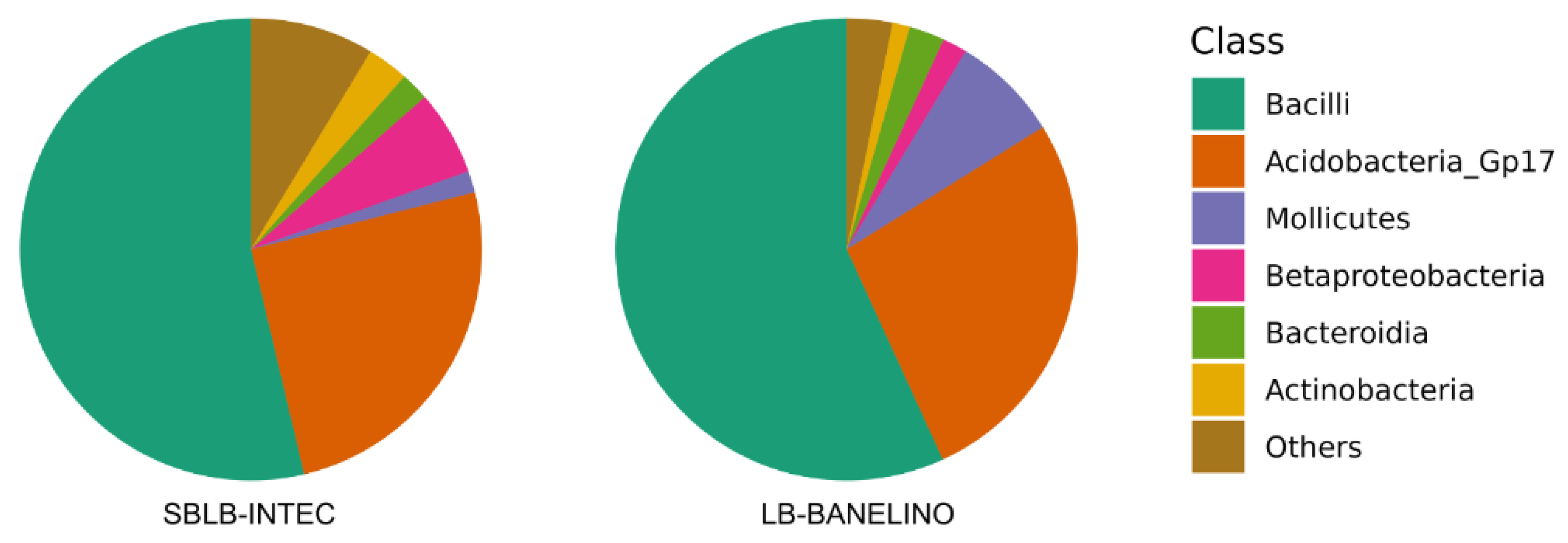

The high representation of the Bacilli class indicates a significant capacity for organic matter decomposition and nutrient mineralization, as well as the production of biomolecules such as siderophores, which facilitate iron transport, an essential nutrient involved in various physiological processes [

62] (see

Figure 3).

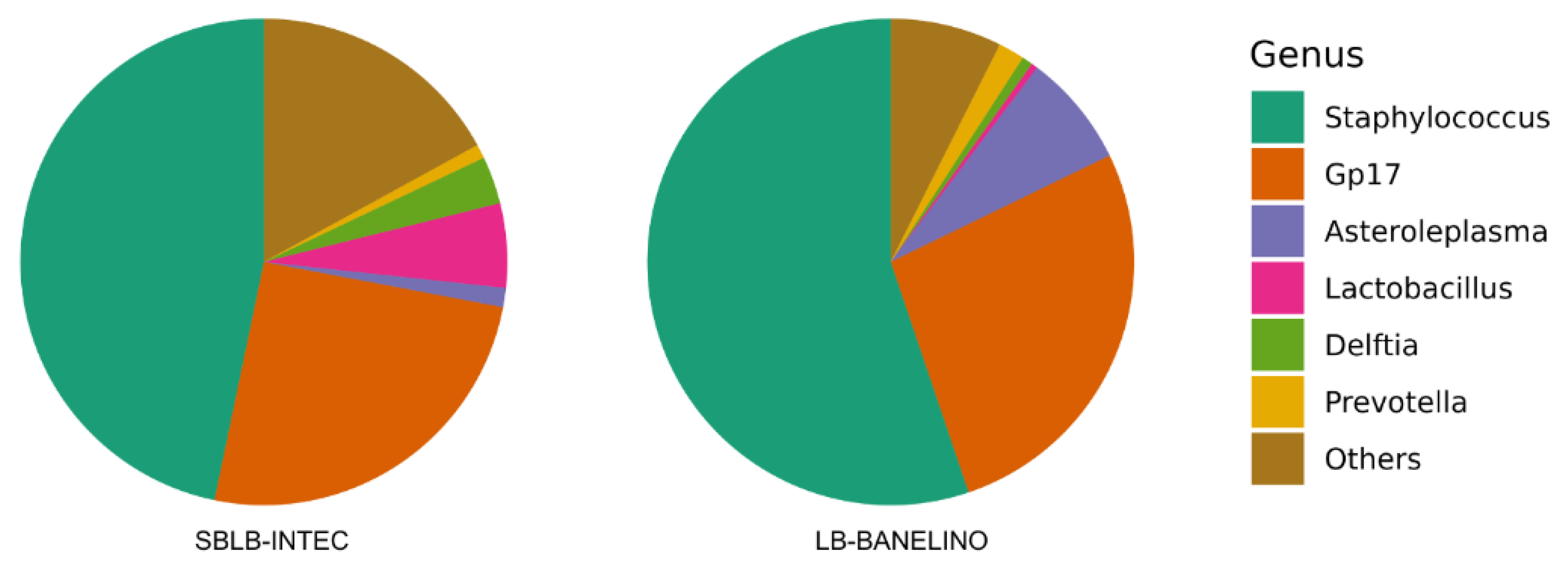

Genera such as

Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, and

Propionibacterium (

Figure 4) highlight various fermentation pathways [

63], while

Prevotella is known for degrading complex organic substrates [

64]. Overall, this diverse bacterial community underlines the potential of these biofertilizers to improve soil fertility, stimulate microbial activity, and support healthy plant growth [

65,

66]. Specific studies have revealed positive aspects associated with certain species, such as

Staphylococcus equorum, Staphylococcus sp., and

Staphylococcus succinus, with the latter demonstrating promising plant growth-promoting abilities, including ammonia production and phosphate solubilization [

67].

Furthermore,

Lactobacillus provides several benefits for plants, such as controlling soil pathogens, including fungi like

Fusarium oxysporum. It also promotes plant growth and protects against abiotic stress using

lactic acid bacteria,

yeasts, and

phototrophic bacteria. Notably, seed treatments with

Lactobacillus nutrient solutions have been shown to reduce damping-off diseases caused by pathogenic fungi [

68].

3.2. Ecotoxicological Evaluation

3.2.1. Lactuca sativa Without pH Adjustment

According to [

69], the pH recommended by lettuce is 5.8. However, when comparing these values with the pH observed in the liquid biofertilizers (see

Table 3), it is evident that pH adjustment is necessary to mitigate phytotoxic effects caused by their high acidity.

The ecotoxicity results with this biomodel indicated the necessity of adjusting the pH to 7 for conducting the ecotoxicological test. This was due to the absence of germination in Lactuca sativa at all evaluated concentrations. The accuracy of the test was supported by the control, which achieved a germination index of over 90%.

3.2.2. Lactuca sativa with pH Adjustment

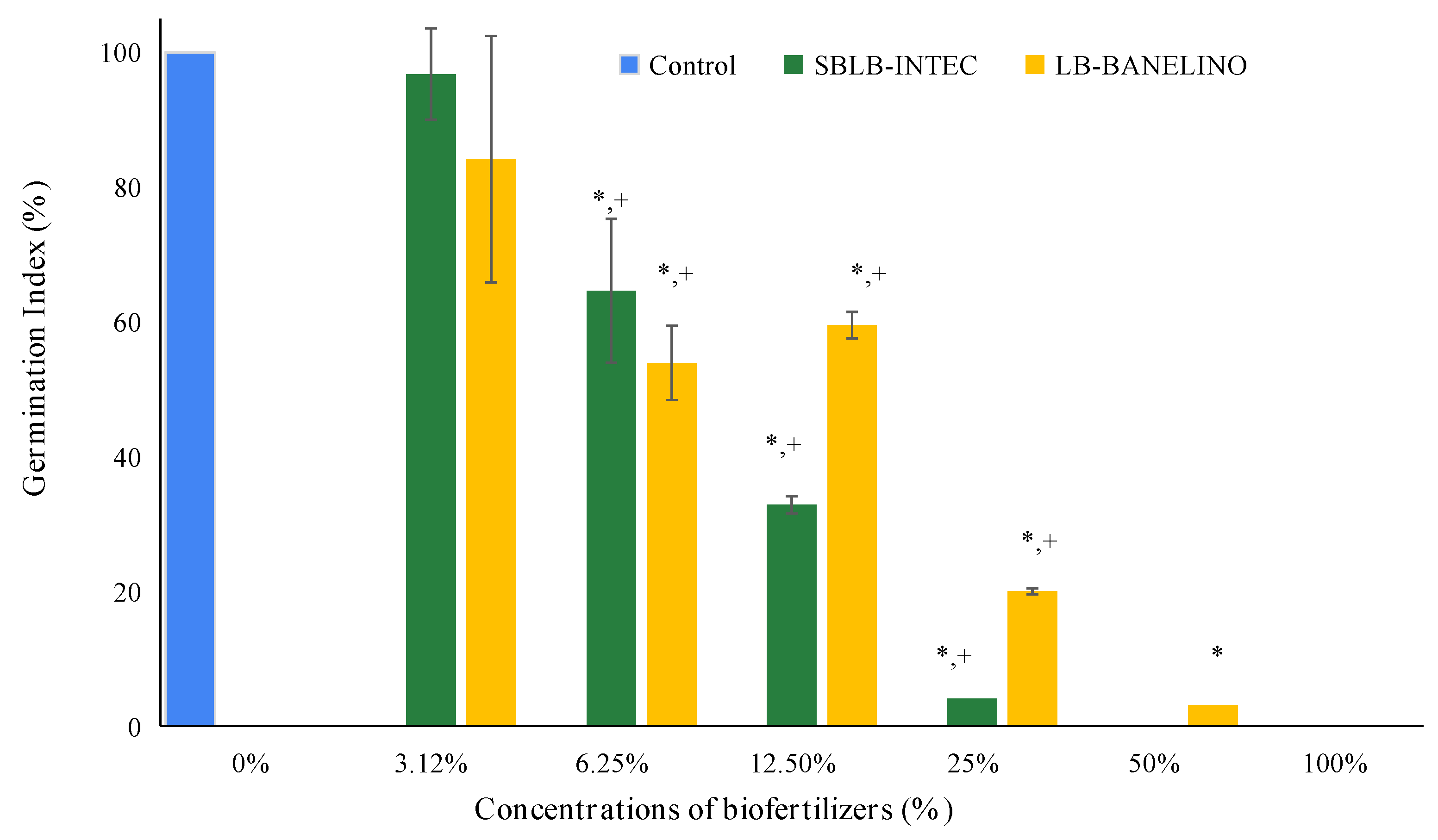

The results of the germination index as a function of liquid biofertilizer concentration (see

Figure 5) show a common trend: as the liquid biofertilizer is diluted, the germination index increases. It is important to note that, according to [

70] doses resulting in a germination index (GI) between 80% and 100% indicate the absence of phytotoxic substances, while values between 50% and 80% and below 50% indicate moderate and high presence of these substances, respectively.

For the two liquid biofertilizers tested, the 3.12% concentration was the only one that presented a germination index above 80% (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Thus, it can be deduced that at this concentration, there are minimal or no phytotoxic substances present. From a concentration of 6.25% onwards, the germination indices fell below 80%. From a concentration of 12.50% onwards, the SBLB-INTEC and LB-BANELINO showed a high presence of phytotoxic substances, with germination indices below 50%. Only the LB-BANELINO showed a germination index below 50% at a concentration of 25%.

The high salinity levels observed in the liquid biofertilizers (see

Table 4) could explain the results obtained for the germination indices. According to [

71], these effects are due to an elevated salt concentration. It is important to highlight that lettuce tolerance to salinity ranges between 1,400 µS/cm and 2,000 µS/cm [

72]. Saline stress, by increasing Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ion concentrations, generates ionic toxicity, water stress, and a reduction in the osmotic potential of seeds, which affects water absorption during imbibition and cellular turgor. These processes collectively limit germination and the development of tissues such as the root and hypocotyl [

72,

73].

3.2.2.1. Determination of NOEC and LOEC for Lactuca sativa Lengths

Comparison of the mean length of lettuce seeds showed significant differences between the six concentrations and the control for SBLB-INTEC, F(4,10)=58.43, P < 0.05, and LB-BANELINO, F(4,10)=20.88, P<0.05 (see

Table 6). Regarding the estimation of the minimum observed effect concentration (LOEC) and no observed effect concentration (NOEC), for SBLB-INTEC, D(4,10)=13.47, P=2.89, and LB-BANELINO, D(4,10)=16.16, P=2.89, NOEC was observed for the 3.12% concentration, while LOEC was identified at 6.25%. These results are consistent with those obtained previously for germination rates, where the 3.12% concentration exceeded the 80% threshold for the two biofertilizers. This suggests the use of 3.12% as suitable for non-inhibitory use in the crop.

4. Conclusions

This study assessed the microbiological and ecotoxicological profiles of two Dominican Republic-produced liquid biofertilizers: Sargassum-based SBLB-INTEC and conventional LB-BANELINO. Both exhibited diverse microbial communities, including Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Acidobacteria, which support nutrient cycling and soil health, with no pathogens detected. Ecotoxicological tests with Lactuca sativa showed phytotoxicity at high concentrations due to acidity and salinity, mitigated at ≤6.25% dilution and pH 7.0, yielding germination indexes >80%. These results affirm the biosecurity and agronomic potential of Sargassum-based biofertilizers, highlighting the need for combined microbial and toxicity assessments in their development. Future field trials are recommended to validate efficacy across diverse crops and soils, advancing sustainable agriculture in coastal regions. Also, this research underscores the importance of integrating microbiological characterization and ecotoxicological testing in biofertilizer evaluation. The findings provide valuable insights for farmers, researchers, and policymakers seeking to develop safe and effective bio-based fertilizers for sustainable agriculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.R.R, E.F.F, M.A.G, R.T.R, and U.J.J.H.; methodology, A.M.M.D, M.E.R.O, G.G, and P.T.T.; software R.T.R, E.F.F., and C.W.D.D.; validation, A.M.M.D, M.E.R.O, G.G, C.W.D.D. and P.T.T; formal analysis, A.M.M.D, Y.R.R, U.J.J.H, E.F.F, C.W.D.D. and P.T.T;.; investigation, Y.R.R, A.M.M.D, C.W.D.D. and P.T.T;.; resources, Y.R.R, E.F.F, M.A.G, R.T.R, and U.J.J.H; data curation, R.T.R, E.F.F, and C.W.D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.R.R, A.M.M.D, M.E.R.O, G.G, and P.T.T. ; writing—review and editing, Y.R.R, E.F.F, M.A.G, R.T.R, and U.J.J.H.; visualization, C.W.D.D.; supervision, Y.R.R, E.F.F, M.A.G, R.T.R, and U.J.J.H.; project administration, Y.R.R, E.F.F, M.A.G, R.T.R, and U.J.J.H; funding acquisition, Y.R.R, E.F.F, M.A.G, R.T.R, and U.J.J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministerio de Eduacion Supeior Ciencia y Tecnologia (MESCYT) through Fondo Nacional de Innovación y Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDOCYT), grant number 2020-2021-2C6-029: Abordaje de onehealth para la mejora de la calidad e innocuidad de los vegetales y hortalizas producidos y comercializados en república dominicana a través de las ciencias ómicas y bioinformática.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This research project was successfully conducted thanks to the support provided by the Research Vice-Rectory and the Deanship of Basic and Environmental Sciences at Instituto Tecnologico de Santo Domingo (INTEC).

Conflicts of Interest

Logistical support and access to experimental facilities were provided by the Asociación Bananos Ecológicos de la Línea Noroeste (BANELINO). The authors declare that this support did not influence the study's design, data collection, interpretation, or publication.

References

- Wang, M.; Hu, C.; Barnes, B.B.; Mitchum, G.; Lapointe, B.; Montoya, J.P. The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. Science (80-. ). 2019, 365, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liranzo-Gómez, R.E.; García-Cortés, D.; Jáuregui-Haza, U. ADAPTATION AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF MASSIVE INFLUX OF SARGASSUM IN THE CARIBBEAN. Procedia Environ. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Tejada-Tejada, P.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Y.; de Francisco, L.E.R.; Paíno-Perdomo, O.; Boluda, C.J. Lead, Chromium, Nickel, Copper and Zinc Levels in Sargassum Species Reached the Coasts of Dominican Republic during 2019: A Preliminary Evaluation for the Use of Algal Biomass as Fertilizer and Animal Feeding. Tecnol. y Ciencias del Agua 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, G.; Guevara, M.A.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, Y. Desarrollo de Un Biofertilizante Basado En Sargassum Sp . Para La Producción de La Cianobacteria Arthrospira Platensis. In Proceedings of the Taller: Las afluencias masivas de sargazo en el Caribe: hechos, impactos y retos; (INTEC), I.T. de S.D., Ed.; Santo Domingo, 2022.

- Madejón, E.; Panettieri, M.; Madejón, P.; Pérez-de-Mora, A. Composting as Sustainable Managing Option for Seaweed Blooms on Recreational Beaches. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrowes, R.; Wabnitz, C.; Eyzaguirre, J. The Great Sargassum Disaster of 2018 - ESSA; 2018;

- Desrochers, A.; Cox, S.-A.; Oxenford, H.A.; van Tussenbroek, B.I. Pelagic Sargassum - A Guide to Current and Potential Uses in the Caribbean; NATIONS, F.A.A.O.O.T.U., Ed.; FAO: Roma, 2022; ISBN 9789251373200.

- Liranzo-Gómez, R.E.; Gómez, A.M.; Gómez, B.; González-Hernández, Y.; Jauregui-Haza, U.J. Characterization of Sargassum Accumulated on Dominican Beaches in 2021: Analysis of Heavy, Alkaline and Alkaline-Earth Metals, Proteins and Fats. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 193, 115120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adderley, A.; Wallace, S.; Stubbs, D.; Bowen-O’Connor, C.; Ferguson, J.; Watson, C.; Gustave, W. Sargassum Sp. as a Biofertilizer: Is It Really a Key towards Sustainable Agriculture for The Bahamas? Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priac, A.; Badot, P.-M.; Crini, G. Treated Wastewater Phytotoxicity Assessment Using Lactuca Sativa: Focus on Germination and Root Elongation Test Parameters. C. R. Biol. 2017, 340, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabaleta, R.; Sánchez, E.; Navas, A.L.; Fernández, V.; Fernandez, A.; Zalazar-García, D.; Fabani, M.P.; Mazza, G.; Rodriguez, R. Phytotoxicity Assessment of Agro-Industrial Waste and Its Biochar: Germination Bioassay in Four Horticultural Species. Agronomy 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimi, A.R.; Ezeokoli, O.T.; Adeleke, R.A. High-Throughput Sequence Analysis of Bacterial Communities in Commercial Biofertiliser Products Marketed in South Africa: An Independent Snapshot Quality Assessment. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilraj, R.; Prasad, G.S.; Janakiraman, K. Sequence-Based Identification of Microbial Contaminants in Non-Parenteral Products. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 52, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, W.J.; Erickson, D.L. DNA Barcodes: Genes, Genomics, and Bioinformatics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 2761–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Teng, J.L.L.; Tse, H.; Yuen, K.-Y. Then and Now: Use of 16S RDNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification and Discovery of Novel Bacteria in Clinical Microbiology Laboratories. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 908–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-N.; Han, Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, T.; You, X.-M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.-C.; Shi, Y.-Q.; Qiao, P.-Z.; Man, C.-L. 16S RRNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification and Infectious Disease Diagnosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 739, 150974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Yaset; Soldevilla-Hernández, L.I.; Guevara, M.Á..; Gandini, G.; Jauregui-Haza, U.J. Assessment of a Sargassum-Based Liquid Biofertilizer for Enhanced Banana Cultivation in Small-Scale Family Farms. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng.

- Bahmani Jafarlou, M.; Pilehvar, B.; Modaresi, M.; Mohammadi, M. Seaweed Liquid Extract as an Alternative Biostimulant for the Amelioration of Salt-Stress Effects in Calotropis Procera (Aiton) W.T. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Hernández, M.; Bennet-Eaton, A.; Silva-Guerrero, E.; Robles-González, S.; Sainos-Aguirre, U.; Castorena-García, H. Caracterización de Bioles de La Fermentación Anaeróbica de Excretas Bovinas y Porcinas. Agrociencia 2016, 50, 471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, E.N.; Rianingsih, L.; Anggo, A.D. The Addition of Different Starters on Characteristics Sargassum Sp. Liquid Fertilizer. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 246, 0–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo-Herrera, D.A.; Muñoz-Ochoa, M.; Hernández-Herrera, R.M.; Hernández-Carmona, G. Biostimulant Activity of Individual and Blended Seaweed Extracts on the Germination and Growth of the Mung Bean. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 2025–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, R.; Nurhayati; Pangestu, H.E.; Basmal, J. Effect of Trichoderma Addition on Sargassum Organic Fertilizer. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 715, 0–5. [CrossRef]

- Opeña, J.M. .; Pacris Jr., F.A.; Pascual, B.N.P. Cellulase-Enhanced Fermented Edible Seaweed Extracts as Liquid Organic Fertilizers for Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L. Var. Crispa). Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2022, 18, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, Z.; Hagare, D.; Liu, M.; Panatta, O.; Hussain, T. Hydroponic Cultivation of Lettuce, Cucumber And. Foods 2023, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aganga, A.A.; Machacha, S.; Sebolai, B.; Thema, T.; Marotsi, B.B. Minerals in Soils and Forages Irrigated with Secondary Treated Sewage Water in Sebele, Botswana. J. Appl. Sci. 2005, 5, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bassam, N.; Tietjen, C. Municipal Sludge as Organic Fertilizer with Special Reference to the Heavy Metal Constituents. 1977.

- Elliott, S.; Frio, A.; Jarman, T. Heavy Metal Contamination of Animal Feedstuffs – a New Survey. J. Appl. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union DIRECTIVE 2002/32/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 7 May 2002 on Undesirable Substances in Animal Feed; 2006; pp. 1–22;

- European Union COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) 2019/1869 Amending and Correcting Annex I to Directive 2002/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Maximum Levels for Certain Undesirable Substances in Animal Feed. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, Commission.

- FAO NORMA GENERAL PARA LOS CONTAMINANTES Y LAS TOXINAS PRESENTES EN LOS ALIMENTOS Y PIENSOS; 1995; pp. 1–86;

- Huertos, E.G.; Baena, A.R. Contaminación de Suelos Por Metales Pesados. MACLA, Rev. la Soc. Española Mineral. 2008, 10, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants; CRC press, 2000; ISBN 042919112X.

- Kfle, G.; Asgedom, G.; Goje, T.; Abbebe, F.; Habtom, L.; Hanes, H. The Level of Heavy Metal Contamination in Selected Vegetables and Animal Feed Grasses Grown in Wastewater Irrigated Area, around Asmara, Eritrea. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 1359710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloke, A. Contents of Arsenic, Cadmium, Chromium, Fluorine, Lead, Mercury and Nickel in Plants Grown on Contaminated Soil. In Proceedings of the UN-ECE Symposium, Geneva; 1979.

- Linzon, S.N. Phytotoxicology Excessive Levels for Contaminants in Soil and Vegetation. Rep. Minist. Environ. Ontario, Canada 1978.

- McDowell, L.R. Minerals in Animal and Human Nutrition 1992.

- Serrato, F.B.; Díaz, A.R.; Sarría, F.A.; Brotóns, J.M.; López, S.R. Afección de Suelos Agrícolas Por Metales Pesados En Áreas Limítrofes a Explotaciones Mineras Del Sureste de España. Papeles Geogr. 2010, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.B.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, A.K. Effect of Lactic Acid on the Hydration of Portland Cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 1986, 16, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMARN Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-147-SEMARNAT/SSA1-2004, Que Establece Criterios Para Determinar Las Concentraciones de Remediación de Suelos Contaminados Por Arsénico, Bario, Berilio, Cadmio, Cromo Hexavalente, Mercurio, Níquel, Plata, Plomo, Selenio, Talio Y/. D. Of. 2007.

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data 2010.

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Rincon, N.; Wood, D.E.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Pockrandt, C.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L.; Steinegger, M. Metagenome Analysis Using the Kraken Software Suite. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2815–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Yao, M. Microeco: An R Package for Data Mining in Microbial Community Ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiaa255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Niu, G.; Chen, T.; Shen, Q.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.-X. The Best Practice for Microbiome Analysis Using R. Protein Cell 2023, 14, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañedo, Z.A.; Águila, E.; Marrero, O.; Meneses-Marcel, A.; Sifontes, S.; Seijo, M.; Santana, A. Bioensayo de Toxicidad Aguda En Tres Biomodelos Utilizando Compuestos de Referencia. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 36, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Tiquia, S.M. Evaluating Phytotoxicity of Pig Manure from the Pig-on-Litter System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICS ’99; P.R. Wannan and B.R. Taylor, Ed.; 2000.

- Castillo, G. Castillo, G. Ensayos Toxicológicos y Métodos de Evaluación de Calidad de Aguas: : Estandarización, Intercalibración, Resultados y Aplicaciones 2004.

- Chadha, A.; Florentine, S.; Chauhan, B.S.; Long, B.; Jayasundera, M.; Javaid, M.M.; Turville, C. Environmental Factors Affecting the Germination and Seedling Emergence of Two Populations of an Emerging Agricultural Weed: Wild Lettuce (Lactuca Serriola). Crop Pasture Sci. 2019, 70, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelkner, J.; Huang, L.; Lin, T.W.; Schulz, A.; Osterholz, B.; Henke, C.; Blom, J.; Pühler, A.; Sczyrba, A.; Schlüter, A. Abundance, Classification and Genetic Potential of Thaumarchaeota in Metagenomes of European Agricultural Soils: A Meta-Analysis. Environ. Microbiome 2023, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kim, J.-S.; Taffner, J.; Berg, G.; Ryu, C.-M. Archaea, Tiny Helpers of Land Plants. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2494–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vítězová, M.; Kohoutová, A.; Vítěz, T.; Hanišáková, N.; Kushkevych, I. Methanogenic Microorganisms in Industrial Wastewater Anaerobic Treatment. Processes 2020, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, P.; Roldán, M.D.; Moreno-Vivián, C. Nitrate Reduction and the Nitrogen Cycle in Archaea. Microbiology 2004, 150, 3527–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.J.; De Anda, V.; Seitz, K.W.; Dombrowski, N.; Santoro, A.E.; Lloyd, K.G. Diversity, Ecology and Evolution of Archaea. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Kumar, G.; Chhabra, S.; Prasad, R. Role of Soil Microbes in Biogeochemical Cycle for Enhancing Soil Fertility. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Phytomicrobiome for Sustainable Agriculture; 2020; pp. 149–157 ISBN 9780444643254.

- Martínez-Vargas, B.I.; Pérez-y-Terrón, R. Diversidad de Bacterias No Fotosintéticas y Sus Procesos Metabólicos Asociados a Los Líquenes. Alianzas y Tendencias BUAP 2020, 5, 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaedi, Z.S.; Ashy, R.A.; Shami, A.Y.; Majeed, M.A.; Alswat, A.M.; Baz, L.; Baeshen, M.N.; Jalal, R.S. Metagenomic Study of the Communities of Bacterial Endophytes in the Desert Plant Senna Italica and Their Role in Abiotic Stress Resistance in the Plant. Brazilian J. Biol. 2022, 82, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielak, A.M.; Barreto, C.C.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; van Veen, J.A.; Kuramae, E.E. The Ecology of Acidobacteria: Moving beyond Genes and Genomes. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, S.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, E.; Ji, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, L.; et al. Effect of Different Types of Continuous Cropping on Microbial Communities and Physicochemical Properties of Black Soils. Diversity 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Das, S.; Shankhdhar, D.; Shankhdhar, S.C. Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganisms: Mechanism and Their Role in Phosphate Solubilization and Uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.R.; Siani, R.; Treder, K.; Michałowska, D.; Radl, V.; Pritsch, K.; Schloter, M. Cultivar-Specific Dynamics: Unravelling Rhizosphere Microbiome Responses to Water Deficit Stress in Potato Cultivars. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Galyamova, M.R.; Sedykh, S.E. Bacterial Siderophores: Classification, Biosynthesis, Perspectives of Use in Agriculture. Plants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Xin, Y.; Chen, X.; Wen, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, X.; You, M.; Yan, Y. Effects of Compound Lactic Acid Bacteria Additives on the Quality of Oat and Common Vetch Silage in the Northwest Sichuan Plateau. Fermentation 2025, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdeş, M.; Dincă, M.N.; Moiceanu, G.; Zabava, B.Ş.; Paraschiv, G. Microorganisms and Enzymes Used in the Biological Pretreatment of the Substrate to Enhance Biogas Production: A Review. Sustain. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, G.K.; Mukherjee, A.; Singh, S.; Gaurav, A.K.; Kumari, B.; Verma, J.P. Developing Eco-Friendly Endophytic Bioinoculants for Enhancing Productivity and Soil Fertility in Wheat. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 1640–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murindangabo, Y.T.; Kopecký, M.; Perná, K.; Nguyen, T.G.; Konvalina, P.; Kavková, M. Prominent Use of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Soil-Plant Systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 189, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, I.; Bindschedler, S.; Junier, P. Chapter 18 - Firmicutes. In Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology Bacteria and Fungi; Amaresan, N., Senthil Kumar, M., Annapurna, K., Kumar, K., Sankaranarayanan, A.B.T.-B.M. in A.-E., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 363–396 ISBN 978-0-12-823414-3.

- Raman, J.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, K.R.; Eun, H.; Yang, D.; Ko, Y.J.; Kim, S.J. Application of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) in Sustainable Agriculture: Advantages and Limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.S.; Martini, M.R.; De Villiers, D.; Timmons, M.B. Growth and Tissue Elemental Composition Response of Butterhead Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa, Cv. Flandria) to Hydroponic Conditions at Different PH and Alkalinity. Horticulturae 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas, P.; De las Heras, J. Phytotoxicity Test Applied to Sewage Sludge Using Lactuca Sativa L. and Lepidium Sativum L. Seeds. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, N.; Guerrero, F.; Polo, A. Evaluación de Corteza de Pino y Residuos Urbanos Como Componentes de Sustratos de Cultivo. Agric. Técnica 2005, 65, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones Ramirez, H.; Trejo Cadillo, W.; Juscamaita Morales, J. Evaluación De La Calidad De Un Abono Líquido Producido Vía Fermentación Homoláctica De Heces De Alpaca. Ecol. Apl. 2016, 15, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalán López, L.Á.; Lastiri Hernández, M.A.; Alvarez-Bernal, D. Efecto de Diferentes Bioles, Obtenidos a Partir de Halófitas, En La Germinación y Crecimiento de Cuatro Variedades de Hortalizas. Biotecnia 2023, 25, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).