Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

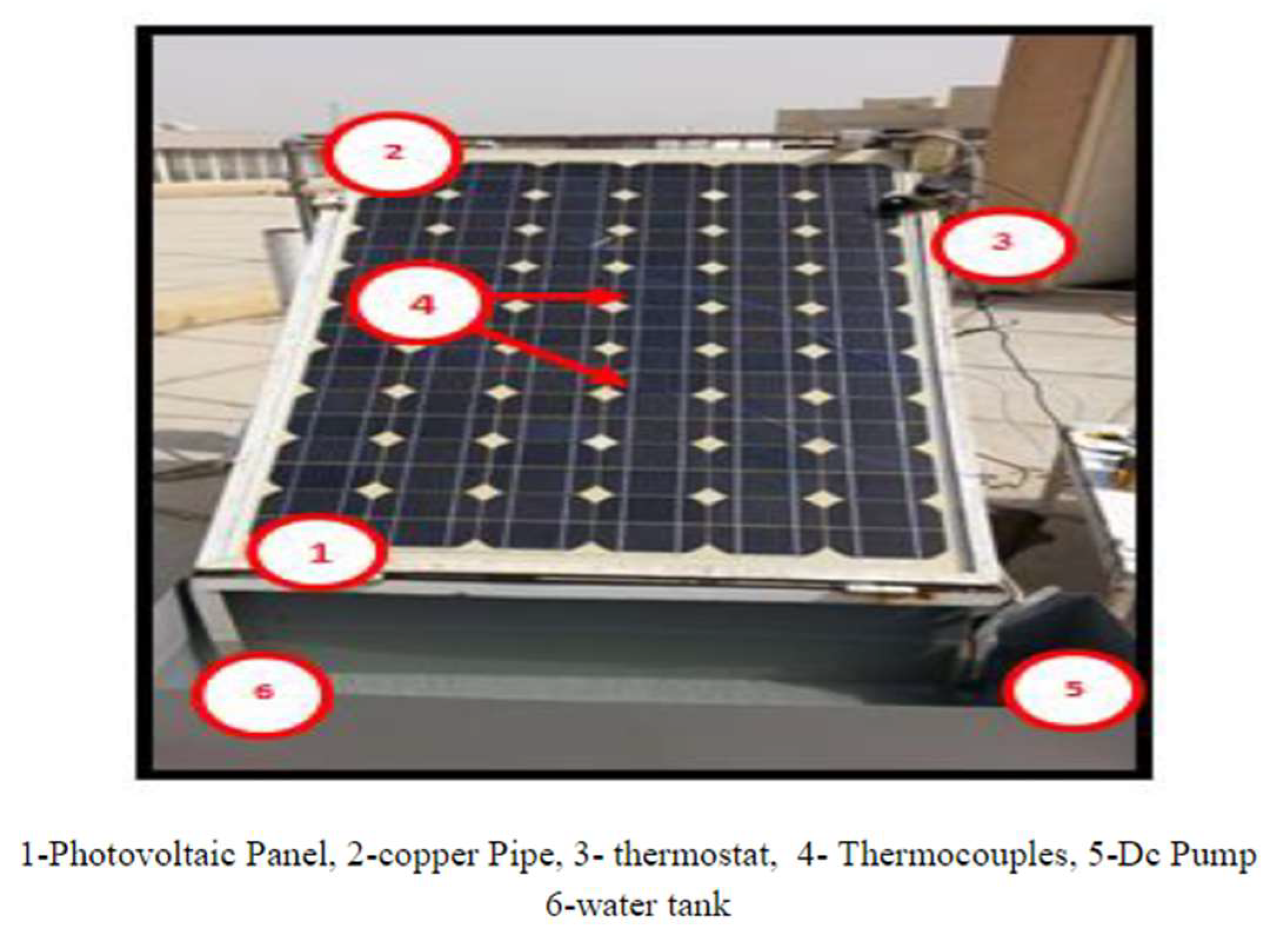

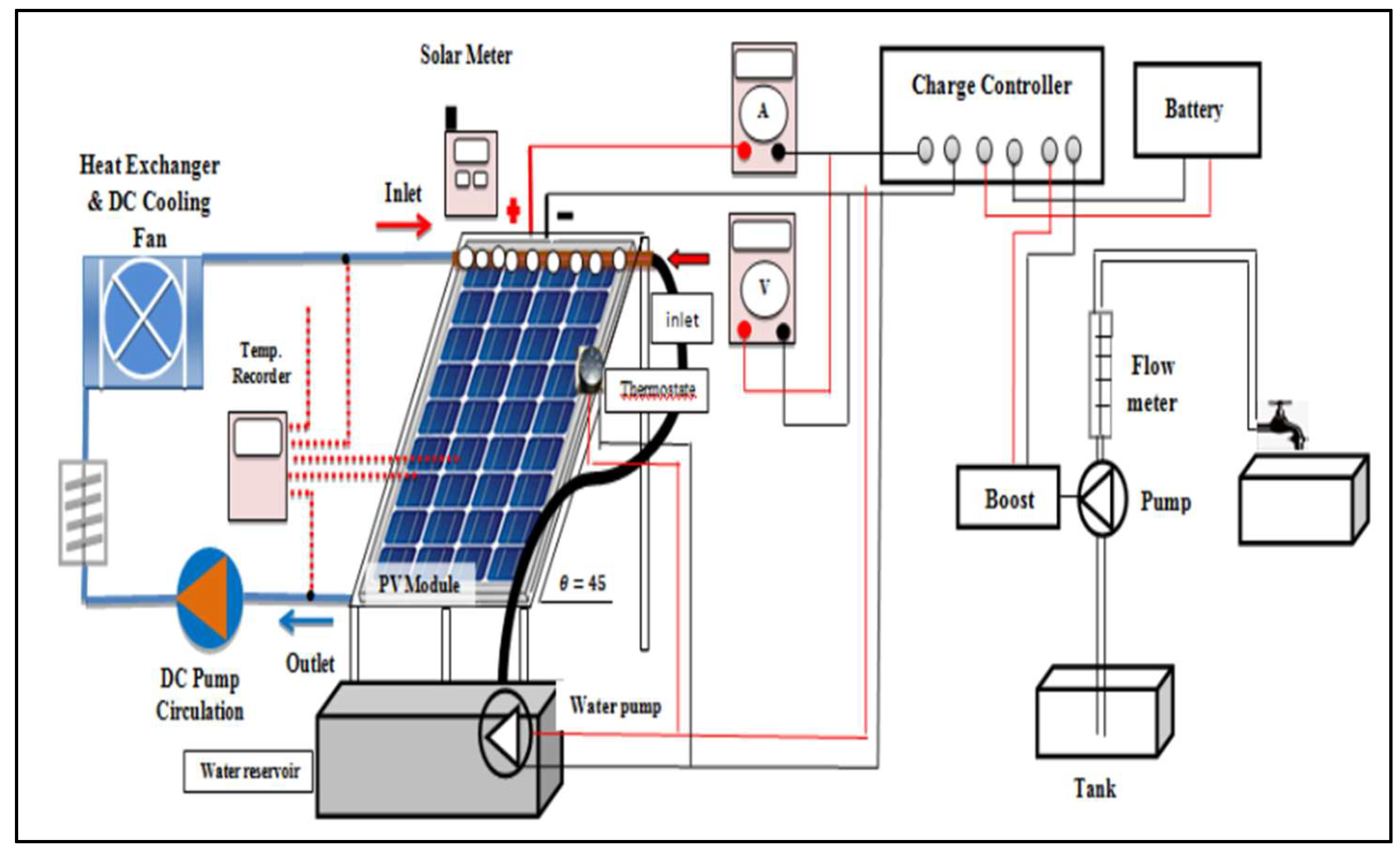

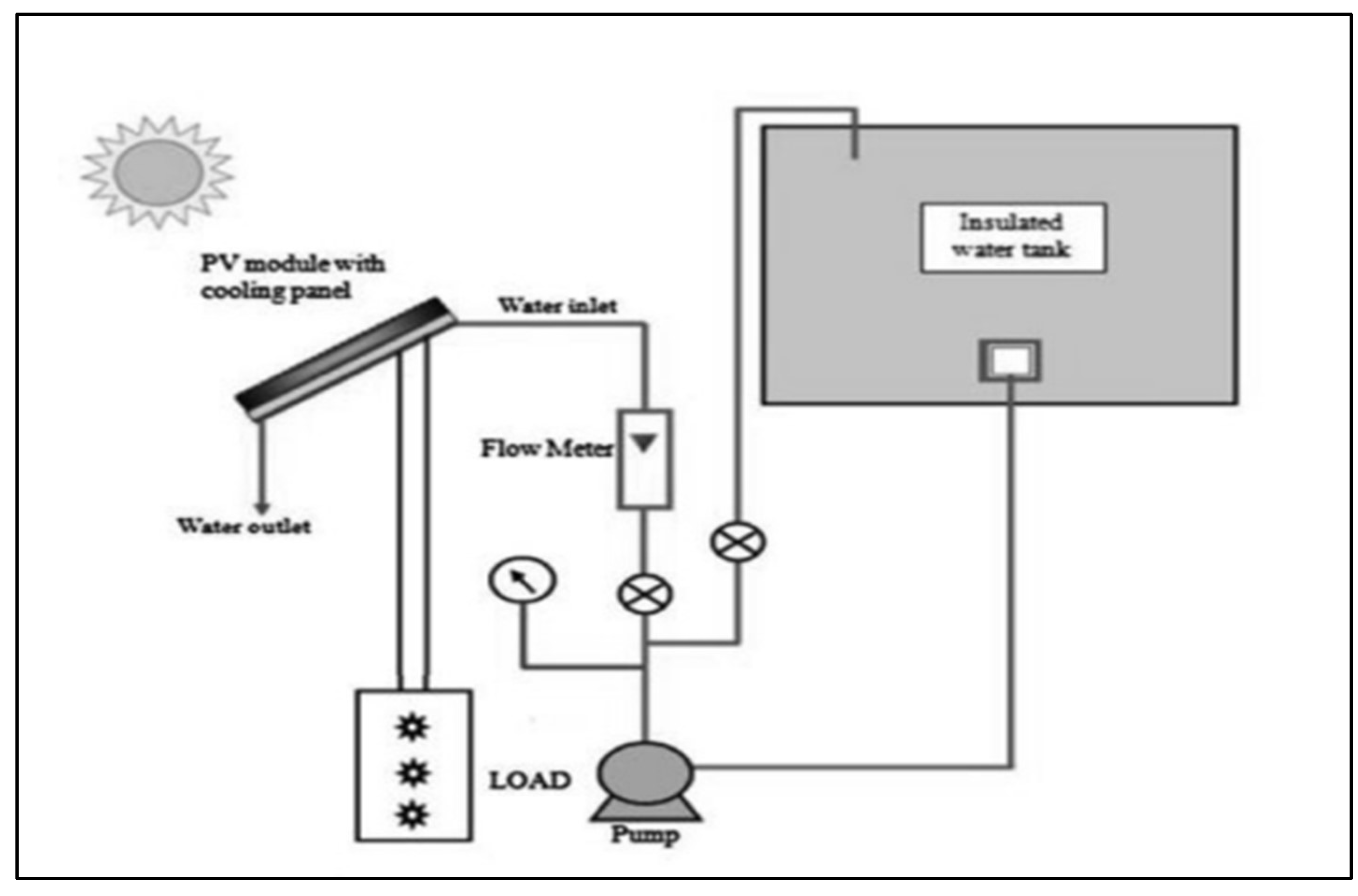

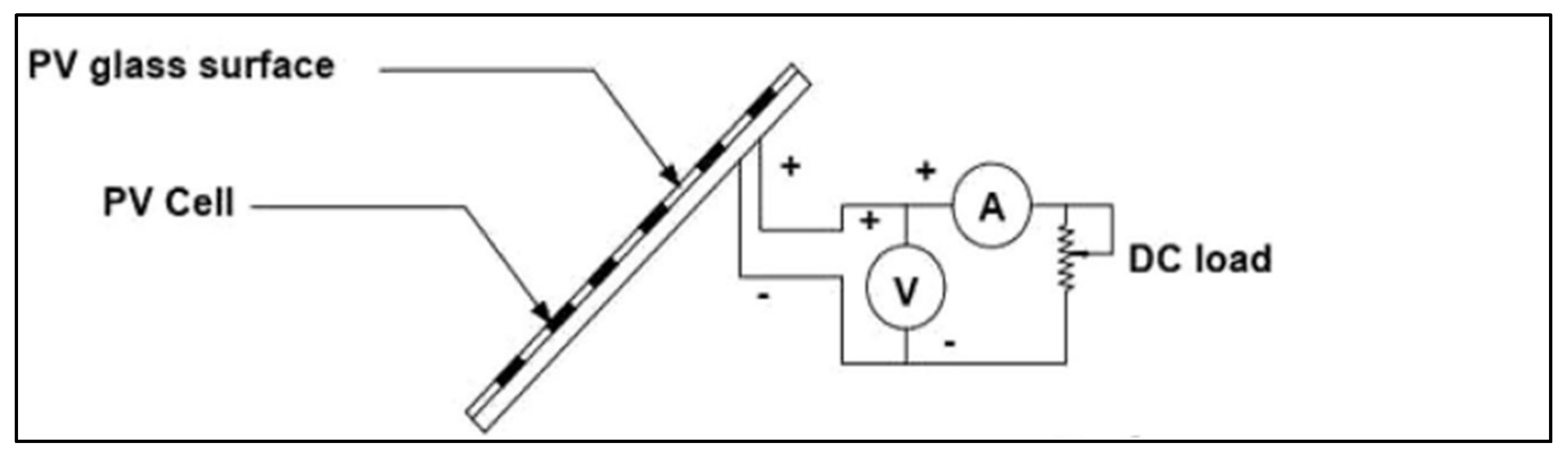

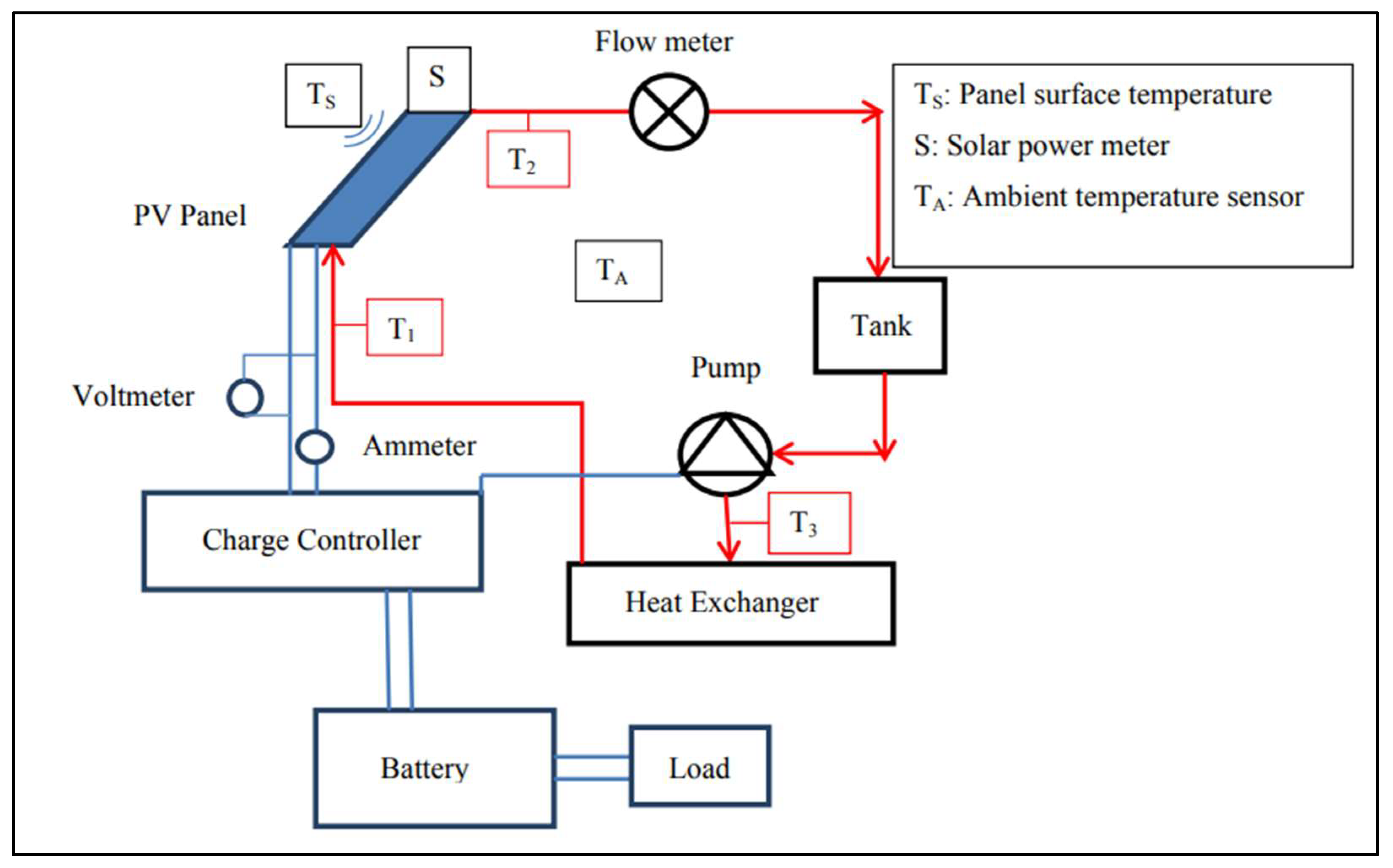

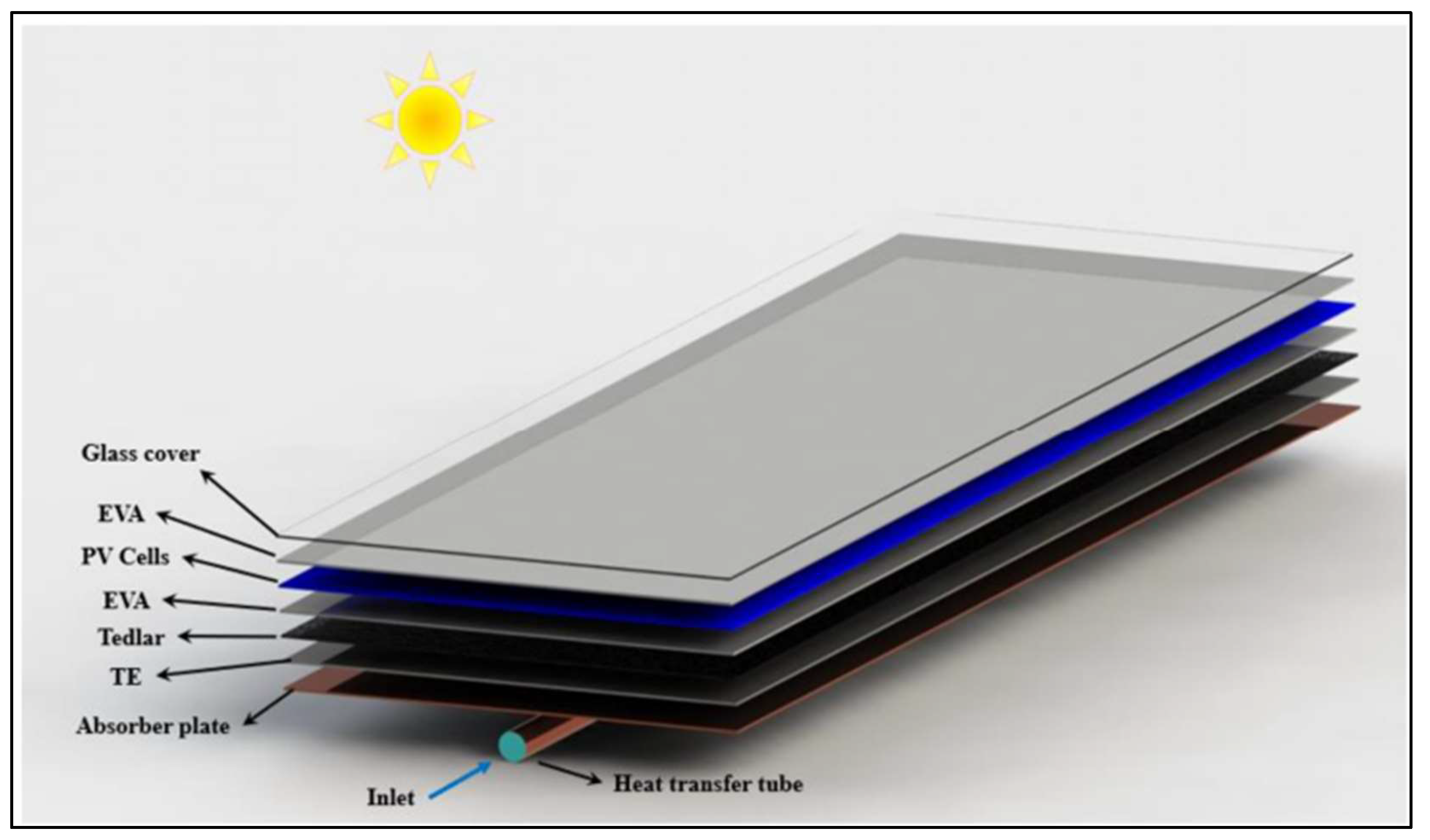

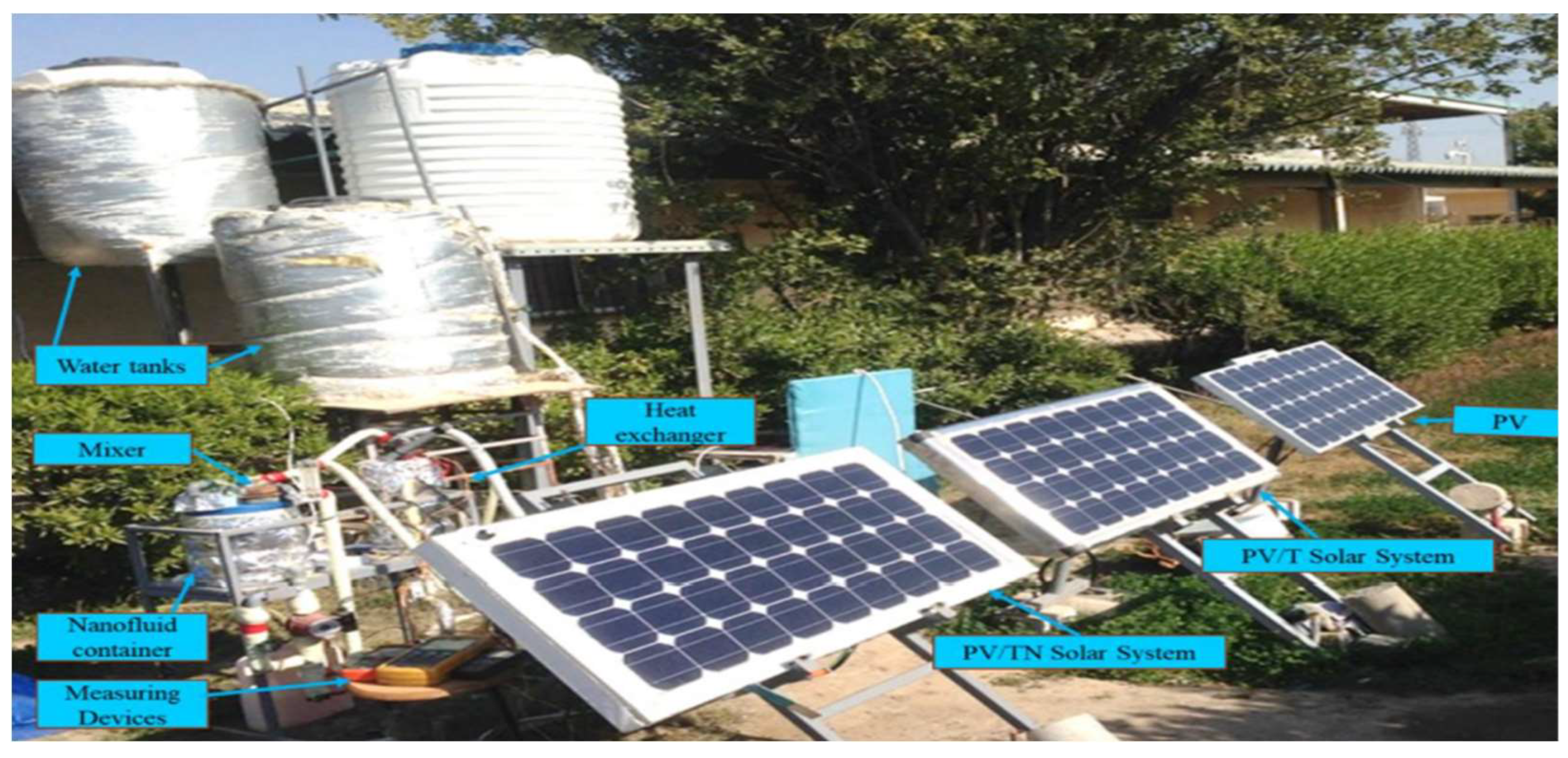

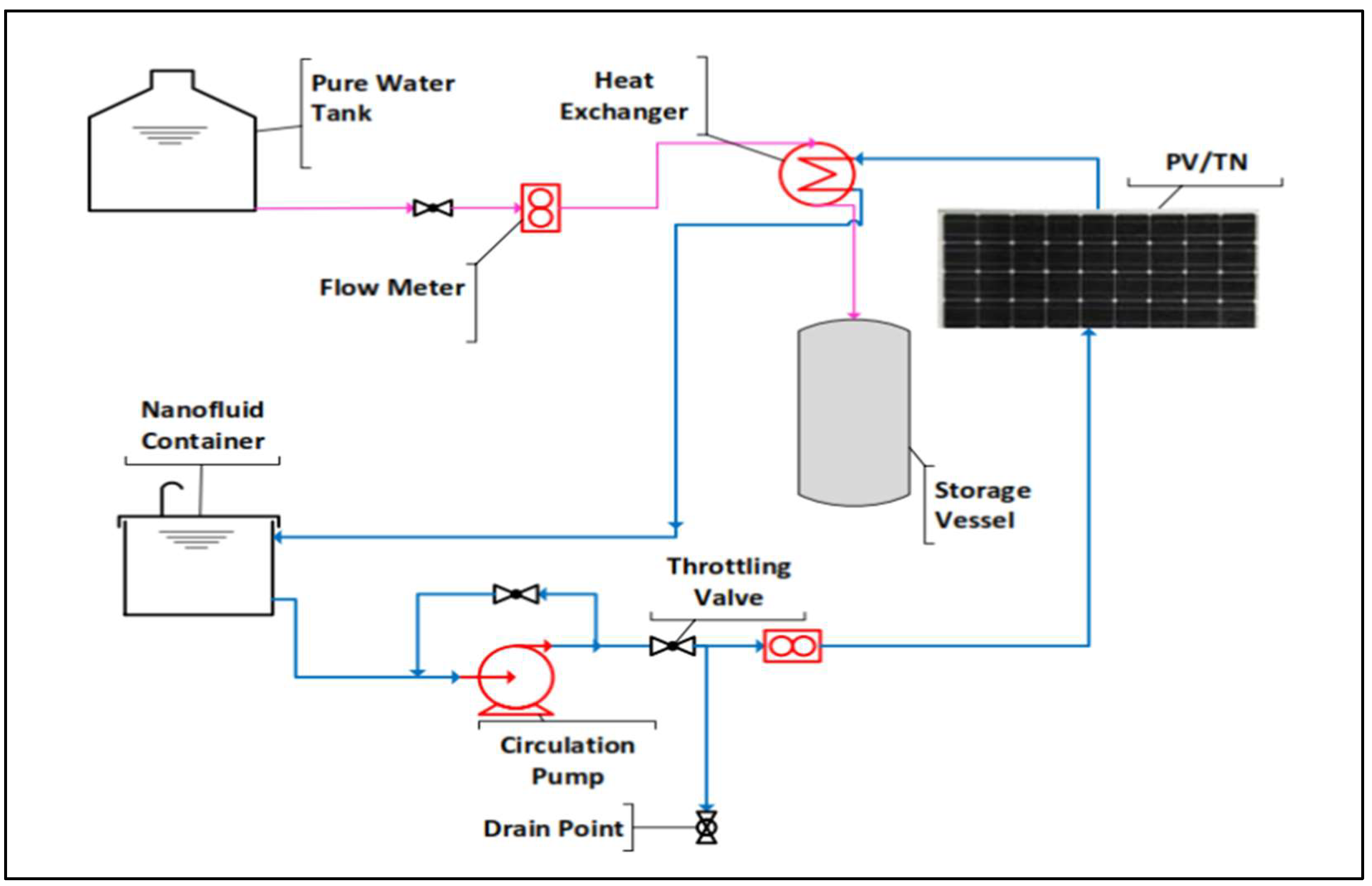

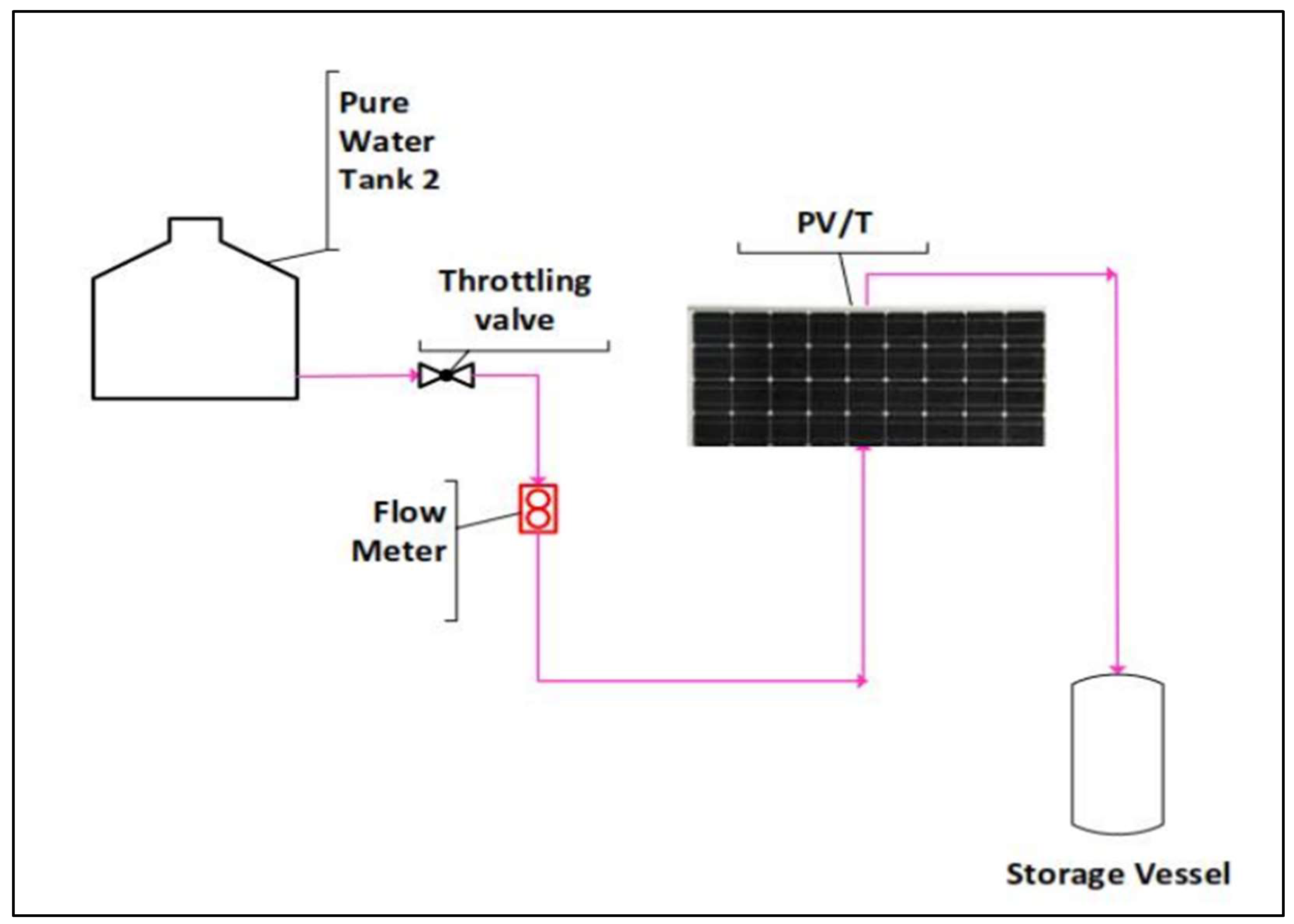

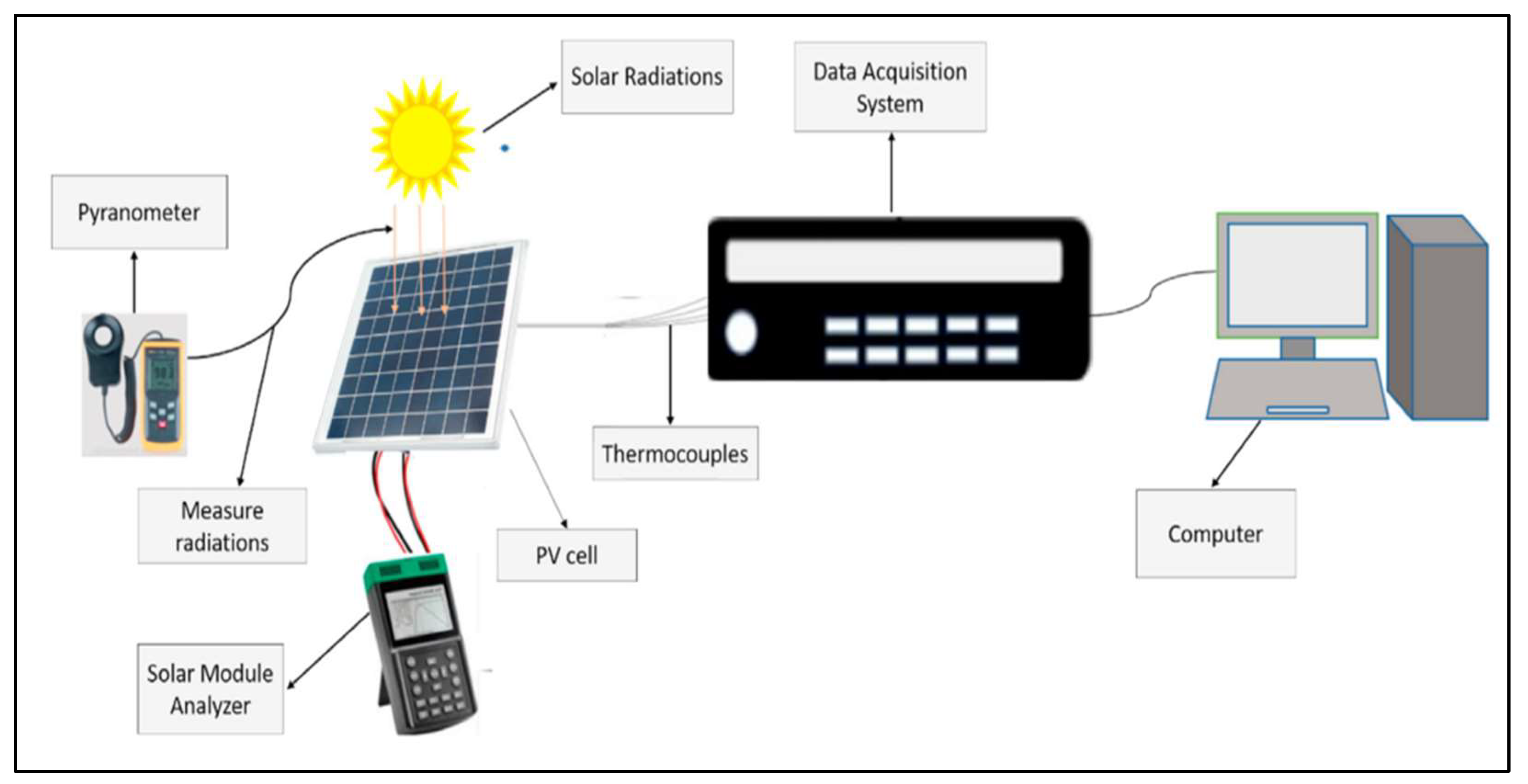

2.1. Photovoltaic Panel Cooling Using Heat Exchanger

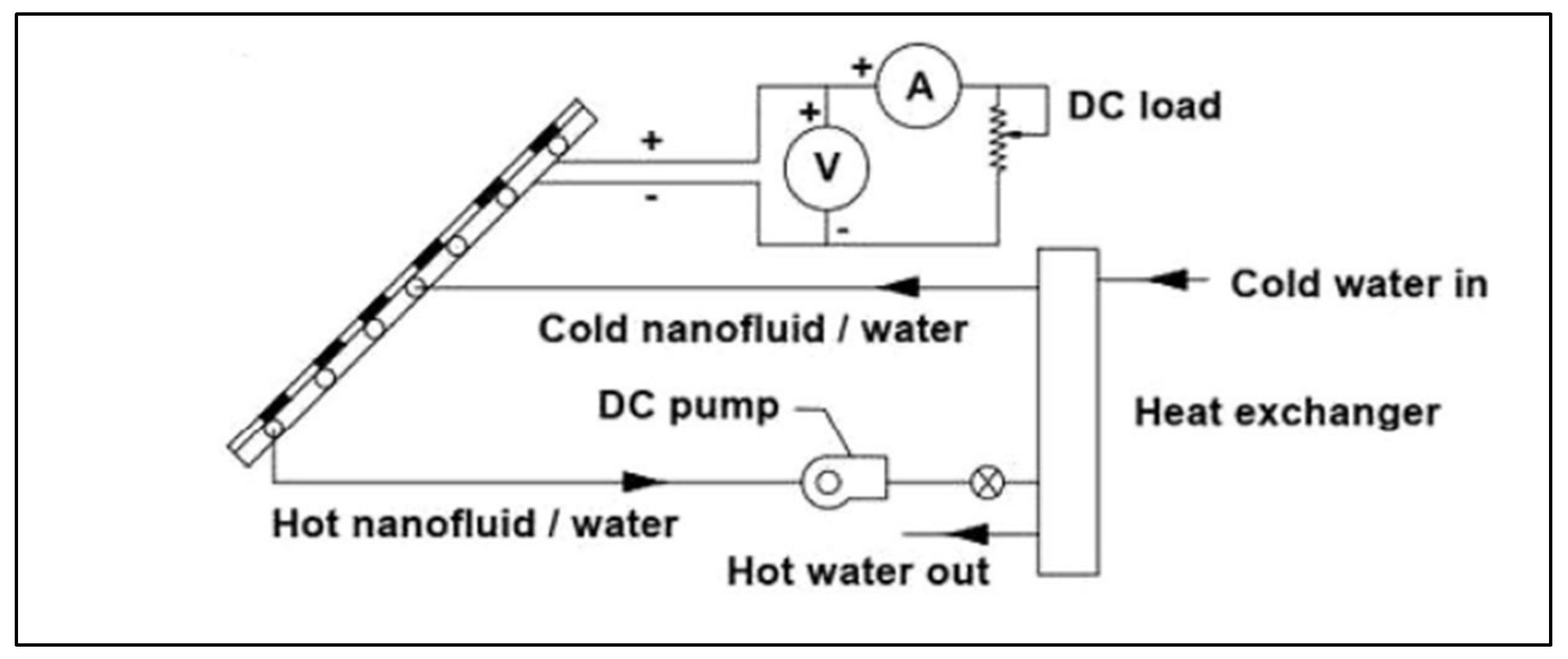

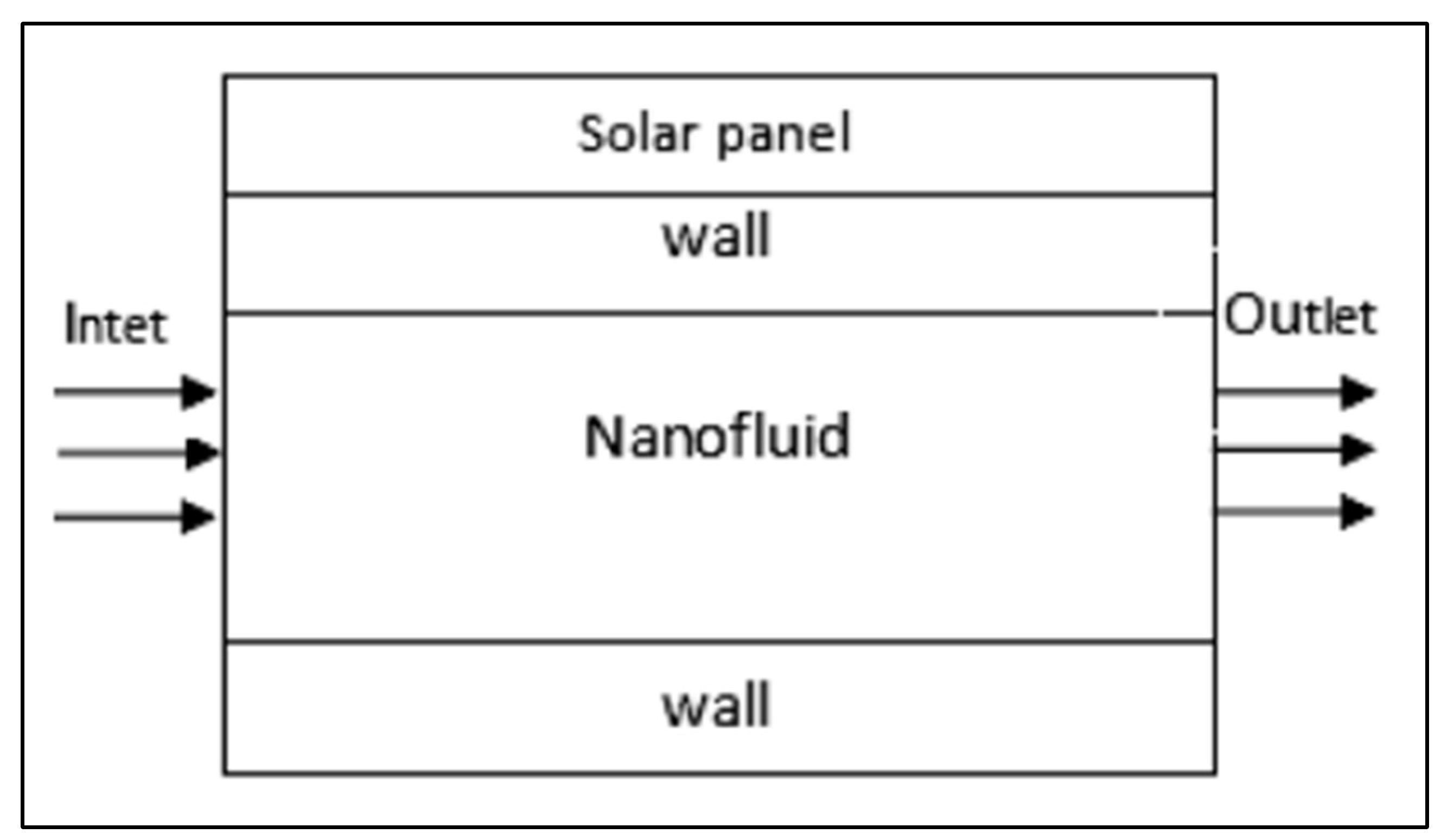

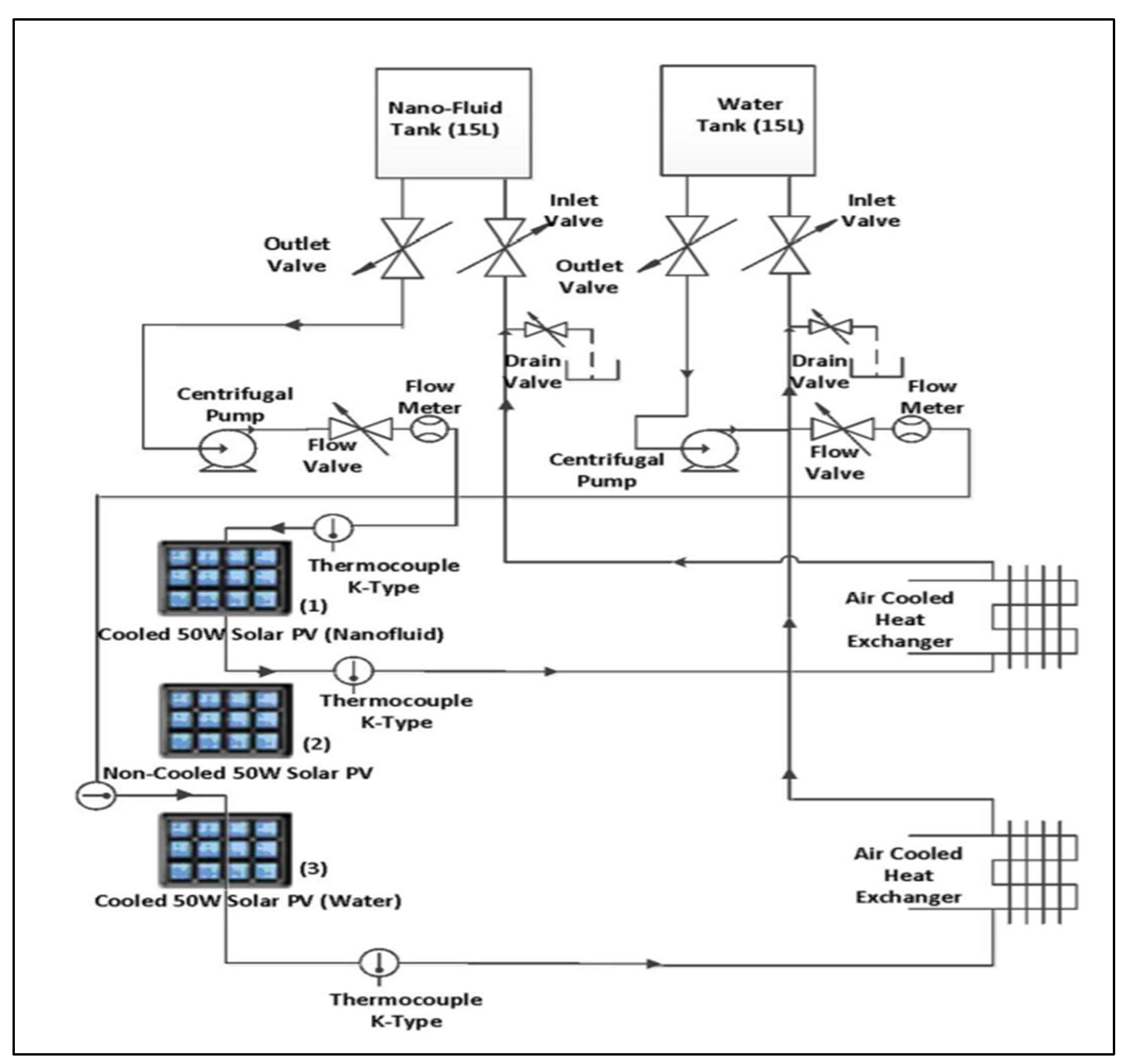

2.2. Photovoltaic Panel Cooling Using Nanofluid

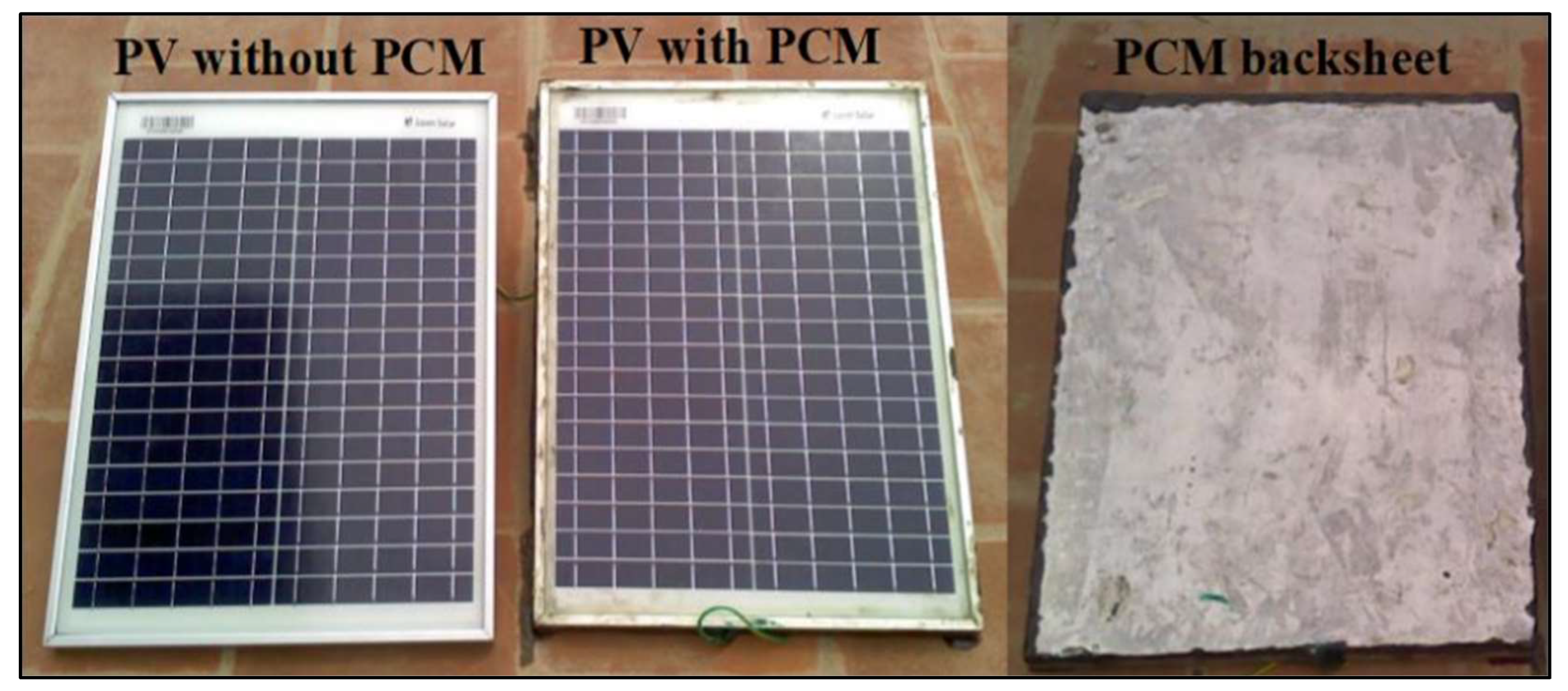

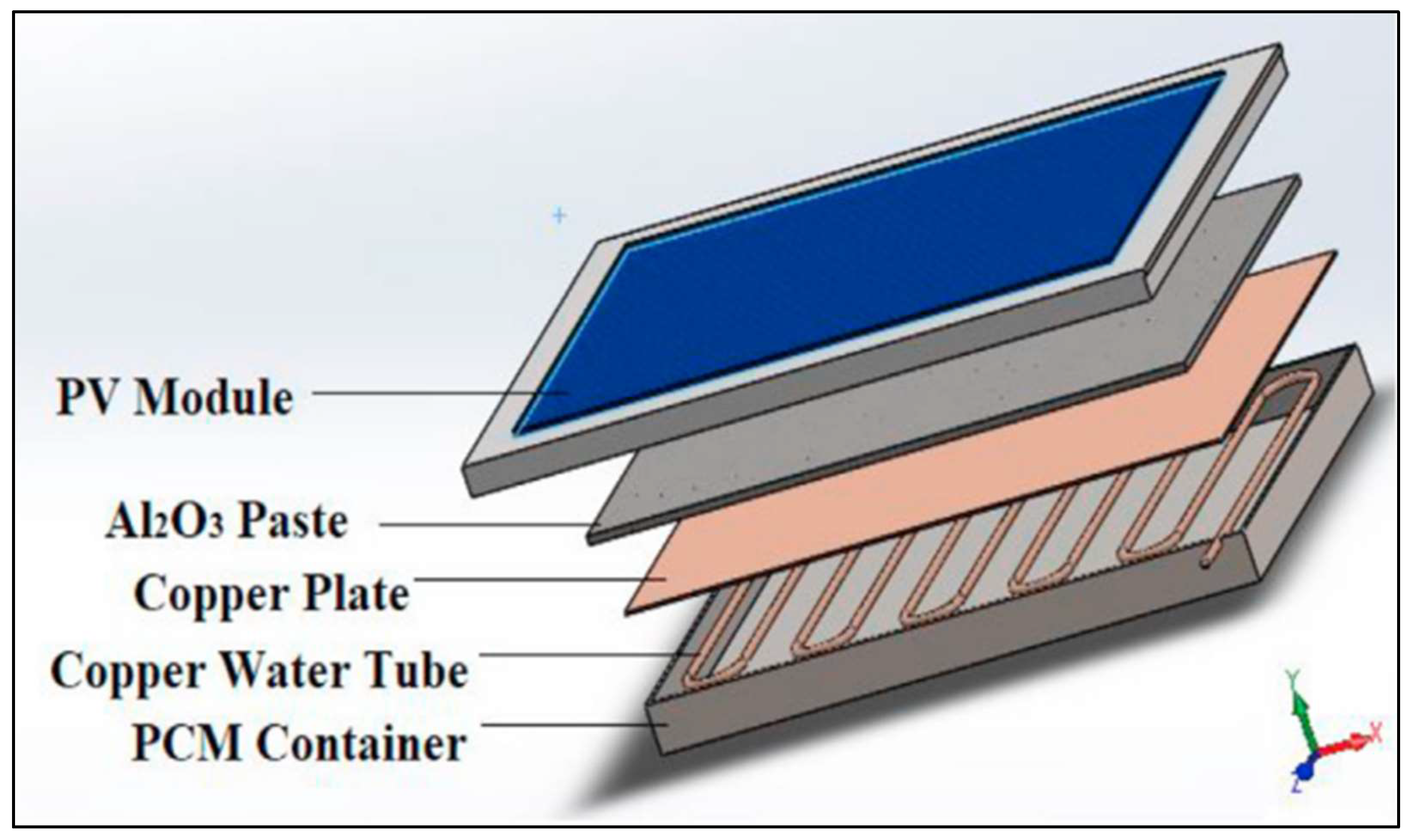

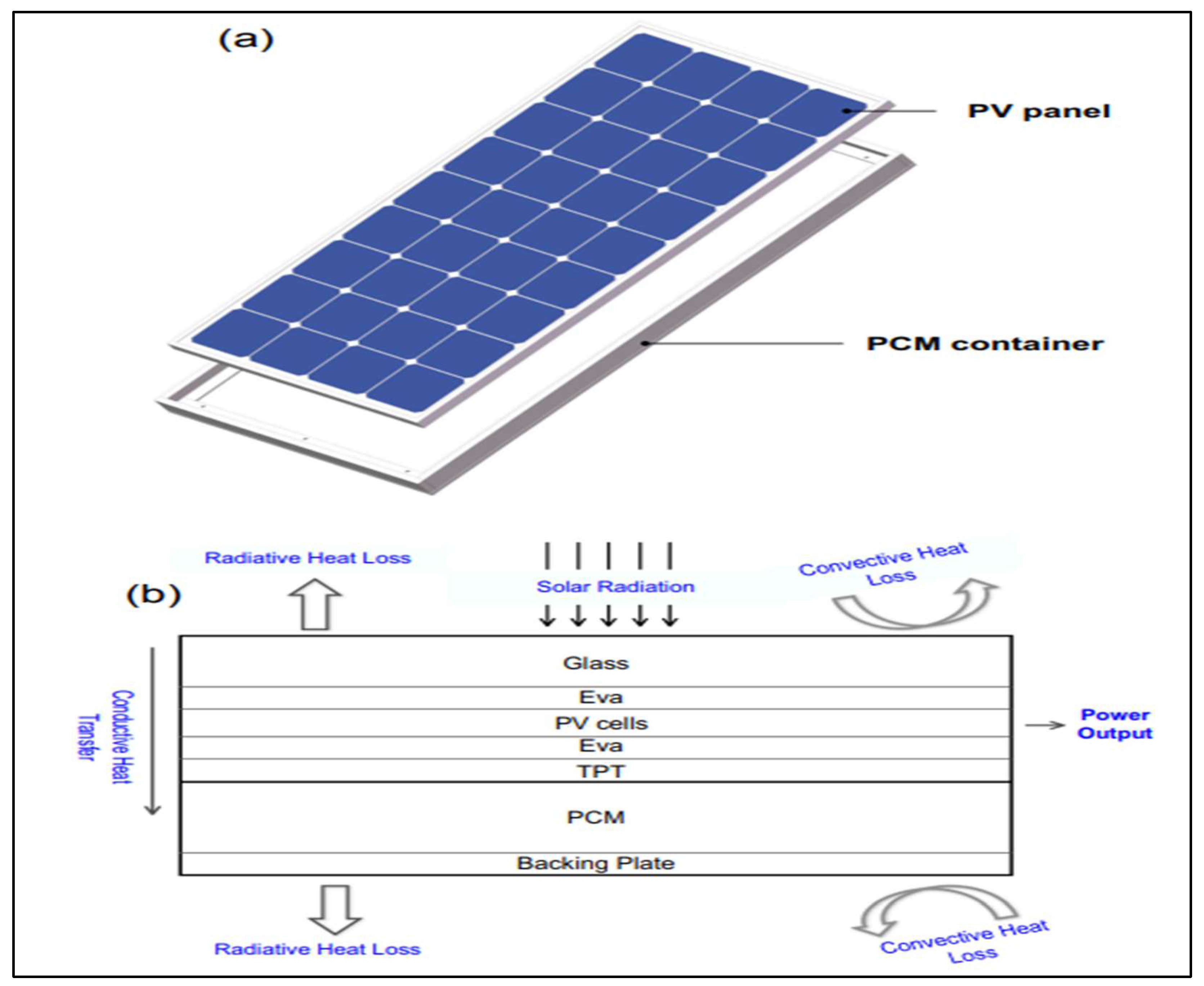

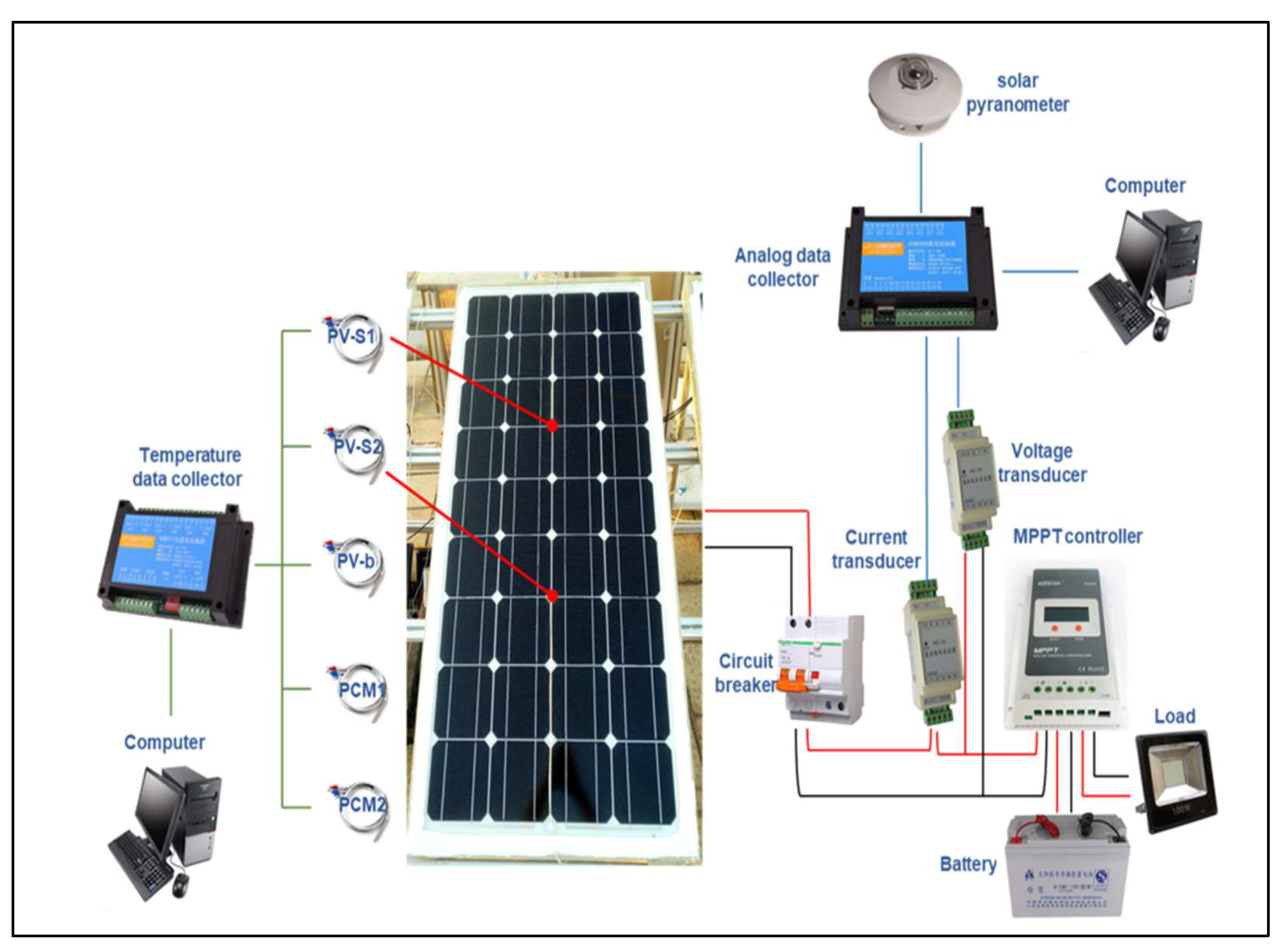

2.3. Photovoltaic Panel Using Phase Change Material

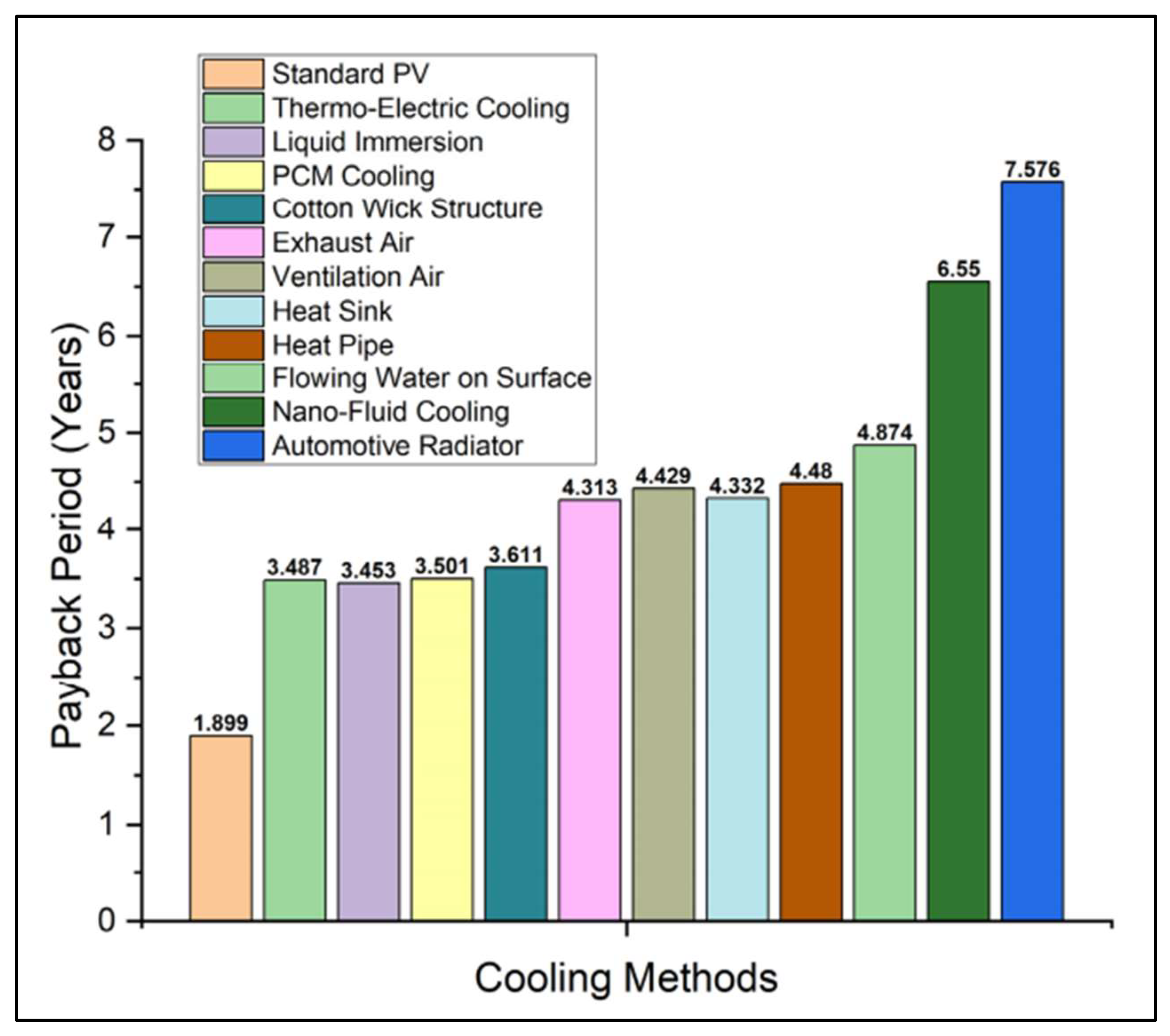

3. Economical Advantages

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PCM | Phase Change Material |

| TE | Thermoelectric |

| EVA | Ethylene Vinyl Acetate |

| TEG | Thermoelectric Generator |

| STC | Standard Test Conditions |

| TEM | Thermoelectric Modules |

| PVT | Photovoltaic Thermal |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| GCHE | Ground-Coupled Heat Exchanger |

References

- Rejeb, O.; Gaillard, L.; Giroux-Julien, S.; Ghenai, C.; Jemni, A.; Bettayeb, M.; Menezo, C. Novel Solar PV/Thermal Collector Design for the Enhancement of Thermal and Electrical Performances. Renew Energy 2020, 146, 610–627. [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, İ.; Bilen, K.; Kıvrak, S. Experimental Investigation of the Efficiency of Solar Panel Over Which Water Film Flows. Politeknik Dergisi 2024, 27 (2), 699–707. [CrossRef]

- Daher, D. H.; Gaillard, L.; Amara, M.; Ménézo, C. Impact of Tropical Desert Maritime Climate on the Performance of a PV Grid-Connected Power Plant. Renew Energy 2018, 125, 729–737. [CrossRef]

- Alzaabi, A. A.; Badawiyeh, N. K.; Hantoush, H. O.; Hamid, A. K. Electrical/Thermal Performance of Hybrid PV/T System in Sharjah, UAE. International Journal of Smart Grid and Clean Energy 2014. [CrossRef]

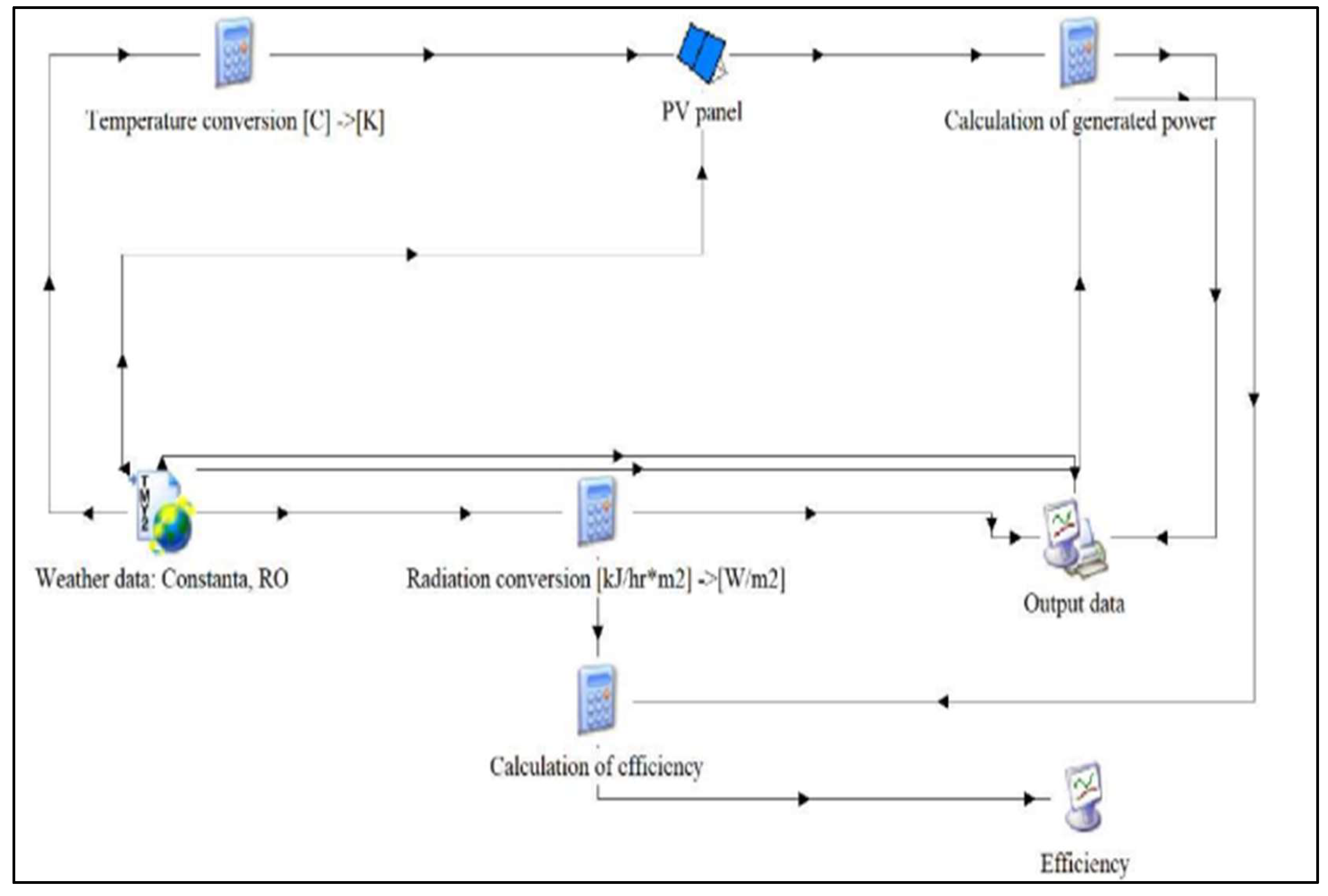

- da Silva, R. M.; Fernandes, J. L. M. Hybrid Photovoltaic/Thermal (PV/T) Solar Systems Simulation with Simulink/Matlab. Solar Energy 2010, 84 (12), 1985–1996. [CrossRef]

- Akrouch, M. A.; Chahine, K.; Faraj, J.; Hachem, F.; Castelain, C.; Khaled, M. Advancements in Cooling Techniques for Enhanced Efficiency of Solar Photovoltaic Panels: A Detailed Comprehensive Review and Innovative Classification. Energy and Built Environment. KeAi Communications Co. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. M. Recent Advancements in PV Cooling and Efficiency Enhancement Integrating Phase Change Materials Based Systems – A Comprehensive Review. Solar Energy 2020, 197, 163–198. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A. K.; Khurana, S.; Nandan, G.; Dwivedi, G.; Kumar, S. Role on Nanofluids in Cooling Solar Photovoltaic Cell to Enhance Overall Efficiency. Mater Today Proc 2018, 5 (9), 20614–20620. [CrossRef]

- Bhakre, S. S.; Sawarkar, P. D.; Kalamkar, V. R. Performance Evaluation of PV Panel Surfaces Exposed to Hydraulic Cooling – A Review. Solar Energy 2021, 224, 1193–1209. [CrossRef]

- Preet, S. Water and Phase Change Material Based Photovoltaic Thermal Management Systems: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 791–807. [CrossRef]

- Othman, M. Y.; Ibrahim, A.; Jin, G. L.; Ruslan, M. H.; Sopian, K. Photovoltaic-Thermal (PV/T) Technology – The Future Energy Technology. Renew Energy 2013, 49, 171–174. [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.; Verma, V.; Singh, B. Optimization of Thermoelectric Cooling Technology for an Active Cooling of Photovoltaic Panel. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 75, 1295–1305. [CrossRef]

- Elbreki, A. M.; Alghoul, M. A.; Sopian, K.; Hussein, T. Towards Adopting Passive Heat Dissipation Approaches for Temperature Regulation of PV Module as a Sustainable Solution. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 69, 961–1017. [CrossRef]

- Bahaidarah, H. M. S.; Baloch, A. A. B.; Gandhidasan, P. Uniform Cooling of Photovoltaic Panels: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 57, 1520–1544. [CrossRef]

- Siah Chehreh Ghadikolaei, S. Solar Photovoltaic Cells Performance Improvement by Cooling Technology: An Overall Review. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46 (18), 10939–10972. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, J.; Abd, H.; Muzahim, R. Enhancement of the Photovoltaic Thermal System Performance Using Dual Cooling Techniques. Exp. Theo. NANOTECHNOLOGY 2019, 3, 149–167. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, U.; Saif-ur-Rehman; Waqas, A.; Majeed, R. Improving Photovoltaic Module Efficiency Using Back Side Water-Cooling Technique. In 2020 IEEE 23rd International Multitopic Conference (INMIC); IEEE, 2020; pp 1–6.

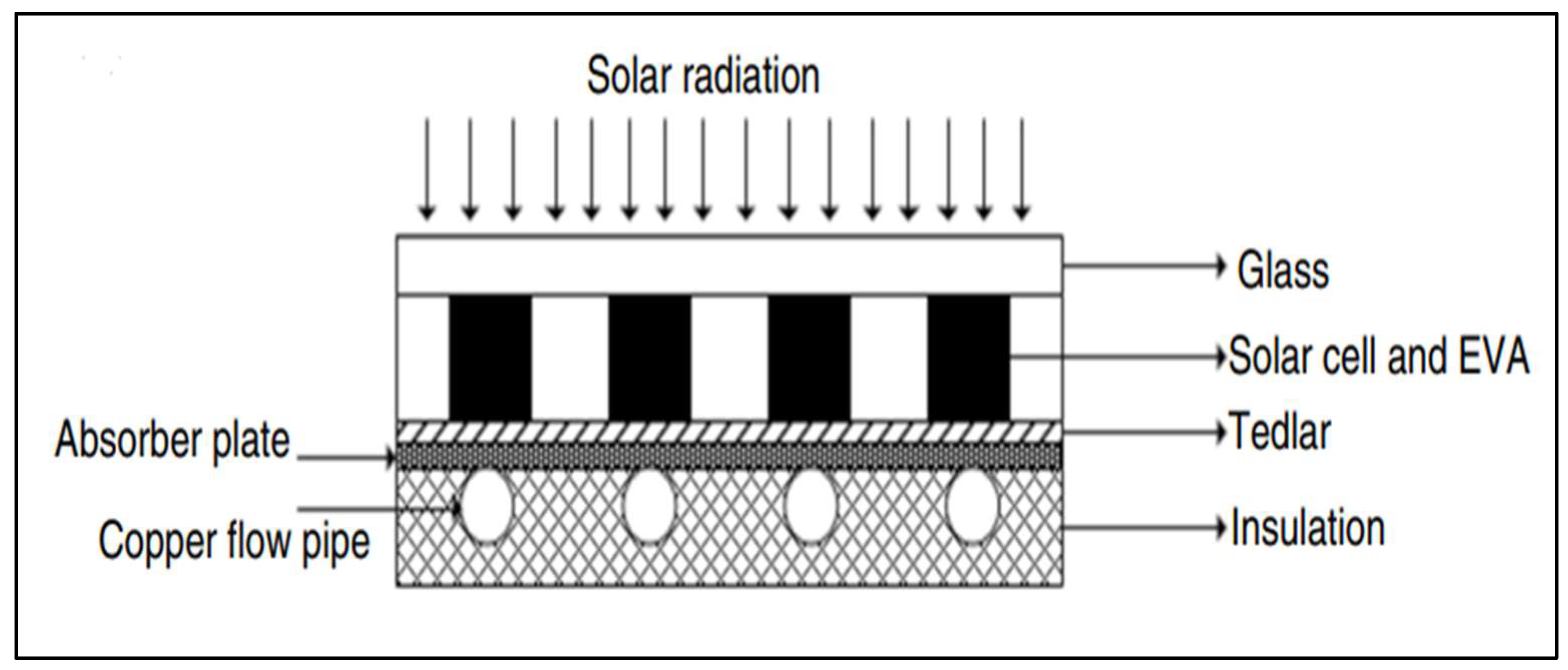

- Jakhar, S.; Paliwal, M. K.; Purohit, N. Assessment of Alumina/Water Nanofluid in a Glazed Tube and Sheet Photovoltaic/Thermal System with Geothermal Cooling. J Therm Anal Calorim 2022, 147 (5), 3901–3918. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, Z.; Heidari, N.; Rahimi, M.; Azimi, N. Enhancing the Thermal Performance of a Photovoltaic Panel Using Nano-Graphite/Paraffin Composite as Phase Change Material. J Therm Anal Calorim 2022, 147 (5), 3947–3964. [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, G.; Greppi, M. Numerical Modeling of a New Integrated PV-TE Cooling System and Support. Results in Engineering 2021, 11, 100240. [CrossRef]

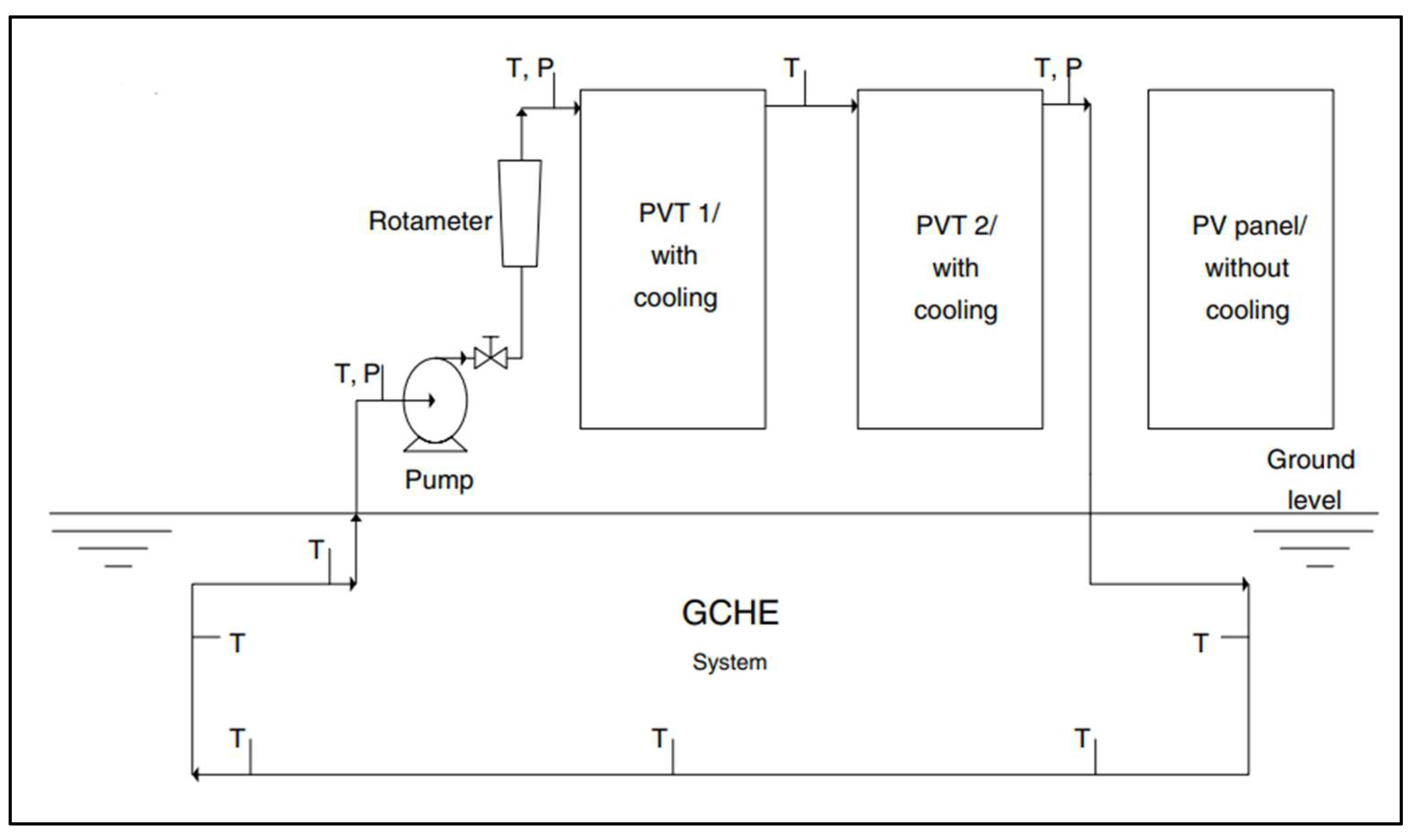

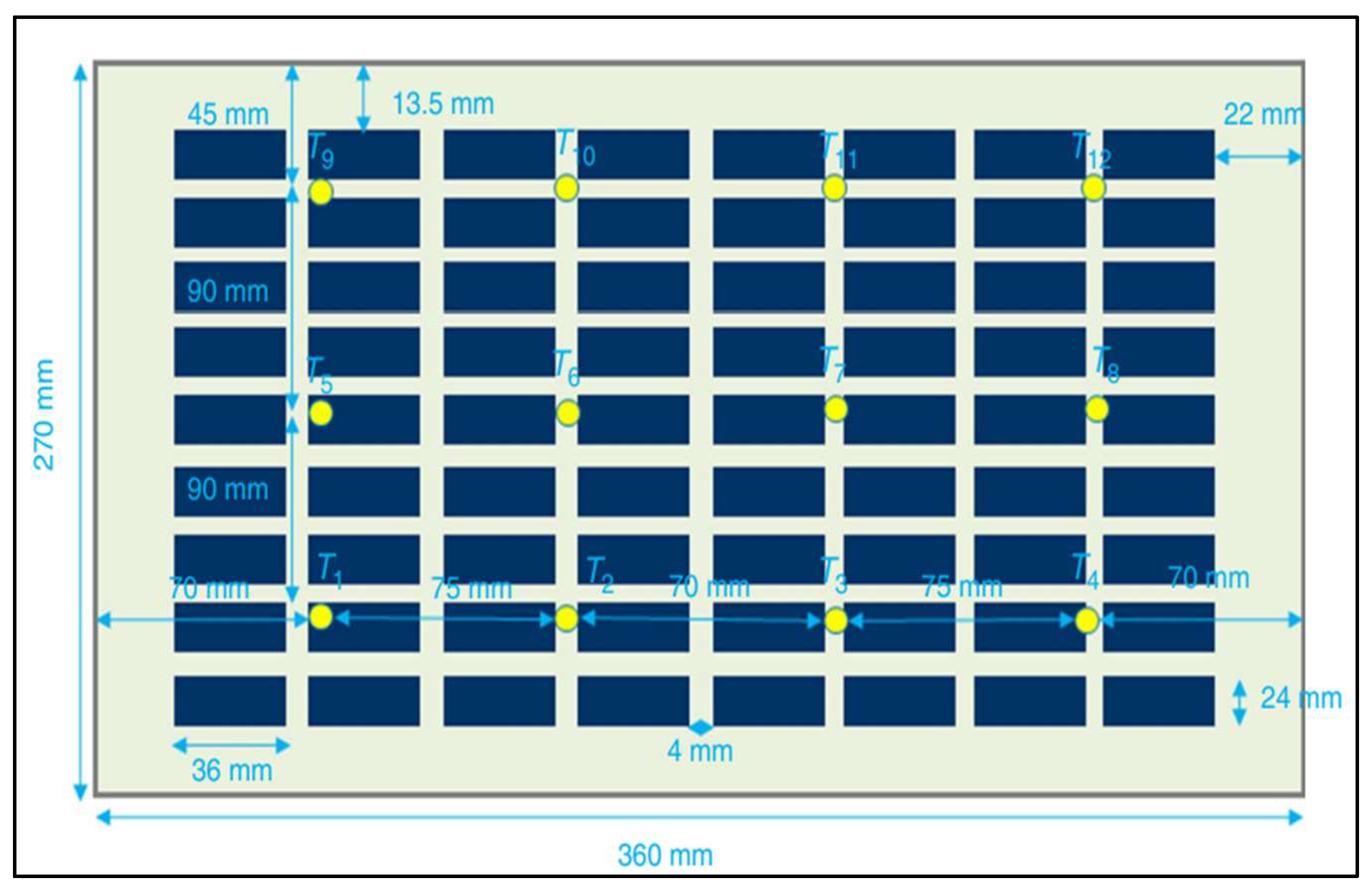

- Majeed, S. H.; Abdul-Zahra, A. S.; Mutasher, D. G.; Dhahd, H. A.; Fayad, M. A.; Al-Waeli, A. H. A.; Kazem, H. A.; Chaichan, M. T.; Al-Amiery, A. A.; Roslam Wan Isahak, W. N. Cooling of a PVT System Using an Underground Heat Exchanger: An Experimental Study. ACS Omega 2023, 8 (33), 29926–29938. [CrossRef]

- Saftoiu, F.; Morega, A. Pulsed Cooling System for Photovoltaic Panels. In 2023 13th International Symposium on Advanced Topics in Electrical Engineering (ATEE); IEEE, 2023; pp 1–5.

- Jafari, R.; Erkılıç, K. T.; Uğurer, D.; Kanbur, Y.; Yıldız, M. Ö.; Ayhan, E. B. Enhanced Photovoltaic Panel Energy by Minichannel Cooler and Natural Geothermal System. Int J Energy Res 2021, 45 (9), 13646–13656. [CrossRef]

- Hudișteanu, S. V.; Popovici, C. G.; Verdeș, M.; Ciocan, V.; Țurcanu, F. E. Case Study on the Efficiency Improvement of Photovoltaic Panels by Cooling. Technium: Romanian Journal of Applied Sciences and Technology 2020, 2 (1), 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M. U.; Siddiqui, O. K.; Al-Sarkhi, A.; Arif, A. F. M.; Zubair, S. M. A Novel Heat Exchanger Design Procedure for Photovoltaic Panel Cooling Application: An Analytical and Experimental Evaluation. Appl Energy 2019, 239, 41–56. [CrossRef]

- Elminshawy, N. A. S.; Mohamed, A. M. I.; Morad, K.; Elhenawy, Y.; Alrobaian, A. A. Performance of PV Panel Coupled with Geothermal Air Cooling System Subjected to Hot Climatic. Appl Therm Eng 2019, 148, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-H.; Liang, J.-D.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Yang, T.-H.; Chen, S.-L. Enhanced Efficiency of Photovoltaic Panels by Integrating a Spray Cooling System with Shallow Geothermal Energy Heat Exchanger. Renew Energy 2019, 134, 970–981. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhai, P.; Li, J.; Liu, X. Experimental Study and Performance Enhancement of a Novel Micro Heat Pipe Photovoltaic/Thermal System in a Cold Region. Appl Therm Eng 2024, 248, 123336. [CrossRef]

- Sathyamurthy, R.; Kabeel, A. E.; Chamkha, A.; Karthick, A.; Muthu Manokar, A.; Sumithra, M. G. Experimental Investigation on Cooling the Photovoltaic Panel Using Hybrid Nanofluids. Appl Nanosci 2021, 11 (2), 363–374. [CrossRef]

- Qeays, I. A.; Yahya, S. Mohd.; Asjad, M.; Khan, Z. A. Multi-Performance Optimization of Nanofluid Cooled Hybrid Photovoltaic Thermal System Using Fuzzy Integrated Methodology. J Clean Prod 2020, 256, 120451. [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, A.; Abdo, G. M.; Emara, A. A. Output Power Boosting of a Photovoltaic Panel Based on Various Back Pipe Structures: A Computational Study. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021, 1172 (1), 012017.

- Khalili, Z.; Sheikholeslami, M.; Momayez, L. Hybrid Nanofluid Flow within Cooling Tube of Photovoltaic-Thermoelectric Solar Unit. Sci Rep 2023, 13 (1), 8202. [CrossRef]

- Abdeldjebar, R.; Elmir, M.; Douha, M. Study of the Performance of a Photovoltaic Solar Panel by Using a Nanofluid as a Cooler. Latvian Journal of Physics and Technical Sciences 2023, 60 (3), 69–84. [CrossRef]

- Shahad, H. A.; Abbood, M. H.; Ali, A. A. Investigating the Impact of Using Nano-Fluid as a Cooling Medium on Photovoltaic/Thermal Panel System Performance. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021, 1067 (1), 012118.

- Ebaid, M. S. Y.; Al-busoul, M.; Ghrair, A. M. Performance Enhancement of Photovoltaic Panels Using Two Types of Nanofluids. Heat Transfer 2020, 49 (5), 2789–2812. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, N.; Rahimi, M. Heat Transfer Enhancement in a Hybrid PV/PCM Based Cooling Tower Using Boehmite Nanofluid. Heat and Mass Transfer 2020, 56 (3), 859–869. [CrossRef]

- Ebaid, Munzer. S. Y.; Ghrair, Ayoup. M.; Al-Busoul, M. Experimental Investigation of Cooling Photovoltaic (PV) Panels Using (TiO 2 ) Nanofluid in Water -Polyethylene Glycol Mixture and (Al 2 O 3 ) Nanofluid in Water- Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide Mixture. Energy Convers Manag 2018, 155, 324–343. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, Z.; Rahimi, M.; Azimi, N. Using High-Frequency Ultrasound Waves and Nanofluid for Increasing the Efficiency and Cooling Performance of a PV Module. Energy Convers Manag 2018, 160, 141–149. [CrossRef]

- Vaziri Rad, M. A.; Kasaeian, A.; Mousavi, S.; Rajaee, F.; Kouravand, A. Empirical Investigation of a Photovoltaic-Thermal System with Phase Change Materials and Aluminum Shavings Porous Media. Renew Energy 2021, 167, 662–675. [CrossRef]

- Kiwan, S.; Ahmad, H.; Alkhalidi, A.; Wahib, W. O.; Al-Kouz, W. Photovoltaic Cooling Utilizing Phase Change Materials. E3S Web of Conferences 2020, 160, 02004.

- Aneli, S.; Arena, R.; Gagliano, A. Numerical Simulations of a PV Module with Phase Change Material (PV-PCM) under Variable Weather Conditions. International Journal of Heat and Technology 2021, 39 (2), 643–652. [CrossRef]

- Badi, N.; Alghamdi, S. A.; El-Hageen, H. M.; Albalawi, H. Onsite Enhancement of REEEC Solar Photovoltaic Performance through PCM Cooling Technique. PLoS One 2023, 18 (3), e0281391. [CrossRef]

- Rajaee, F.; Rad, M. A. V.; Kasaeian, A.; Mahian, O.; Yan, W.-M. Experimental Analysis of a Photovoltaic/Thermoelectric Generator Using Cobalt Oxide Nanofluid and Phase Change Material Heat Sink. Energy Convers Manag 2020, 212, 112780. [CrossRef]

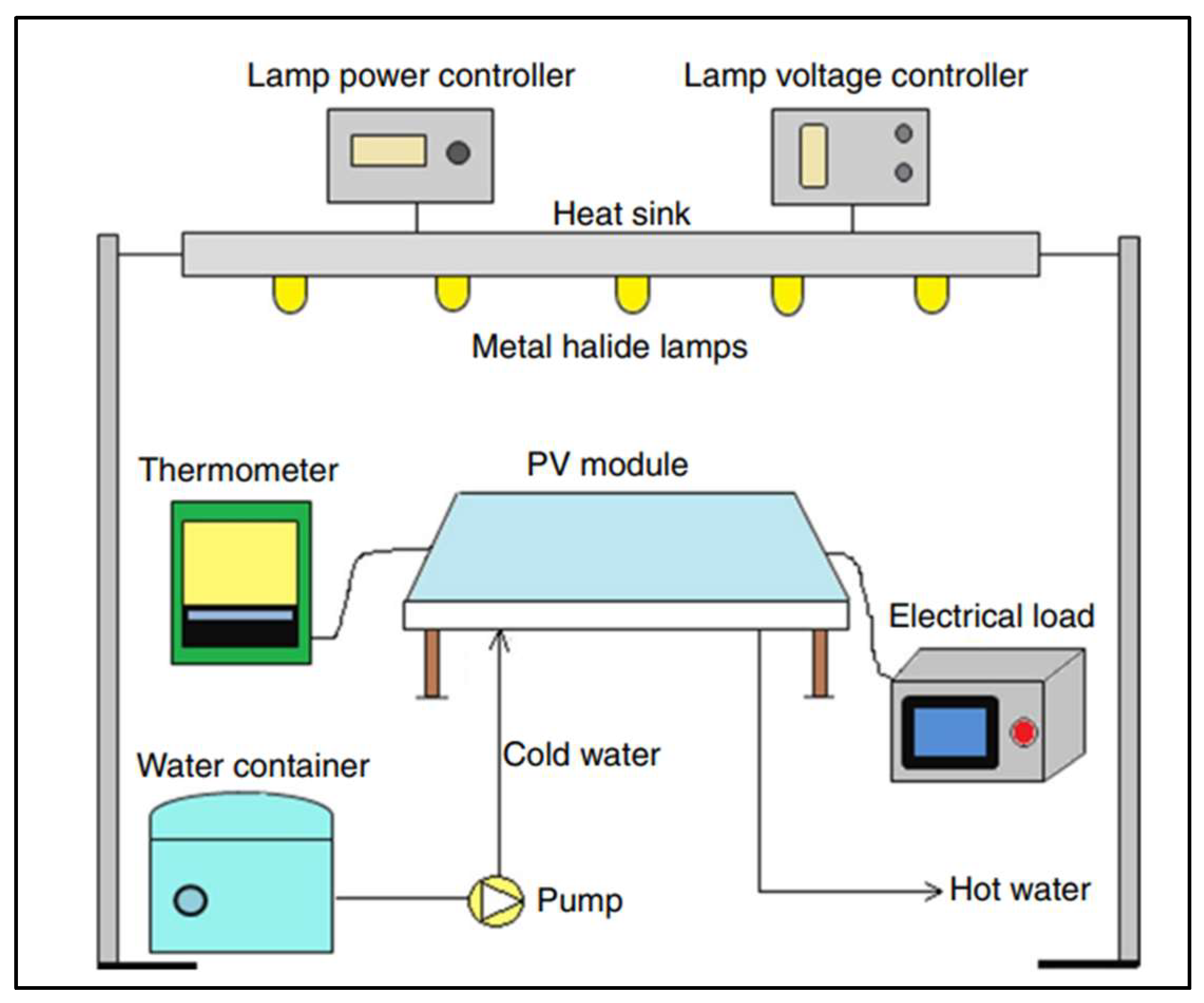

- Bayrak, F.; Oztop, H. F.; Selimefendigil, F. Experimental Study for the Application of Different Cooling Techniques in Photovoltaic (PV) Panels. Energy Convers Manag 2020, 212, 112789. [CrossRef]

- Elavarasan, R.; Velmurugan, K.; Subramaniam, U.; Kumar, A.; Almakhles, D. Experimental Investigations Conducted for the Characteristic Study of OM29 Phase Change Material and Its Incorporation in Photovoltaic Panel. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13 (4), 897. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, F.; Ali, H. M.; Nasir, M. A.; Karahan, M.; Janjua, M. M.; Naseer, A.; Ejaz, A.; Pasha, R. A. Evaluation of Photovoltaic Panels Using Different Nano Phase Change Material and a Concise Comparison: An Experimental Study. Renew Energy 2021, 169, 1265–1279. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, T.; Li, Z.; Song, A. Year-Round Performance Analysis of a Photovoltaic Panel Coupled with Phase Change Material. Appl Energy 2019, 245, 51–64. [CrossRef]

- Selabi, N. B. S.; Lenwoue, A. R. K.; Djouonkep, L. D. W. Numerical Investigation of the Optimization of PV-System Performances Using a Composite PCM-Metal Matrix for PV-Solar Panel Cooling System. J Fluid Flow Heat Mass Transf 2021. [CrossRef]

- Marudaipillai, S. K.; Karuppudayar Ramaraj, B.; Kottala, R. K.; Lakshmanan, M. Experimental Study on Thermal Management and Performance Improvement of Solar PV Panel Cooling Using Form Stable Phase Change Material. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2023, 45 (1), 160–177. [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, V.; Sirisamphanwong, C.; Sukchai, S.; Sahoo, S. K.; Wongwuttanasatian, T. Reducing PV Module Temperature with Radiation Based PV Module Incorporating Composite Phase Change Material. J Energy Storage 2020, 29, 101346. [CrossRef]

- Arıcı, M.; Bilgin, F.; Nižetić, S.; Papadopoulos, A. M. Phase Change Material Based Cooling of Photovoltaic Panel: A Simplified Numerical Model for the Optimization of the Phase Change Material Layer and General Economic Evaluation. J Clean Prod 2018, 189, 738–745. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Alhuyi Nazari, M.; Ghasempour, R.; Shafii, M. B.; Akbarzadeh, A. Numerical Analysis of Photovoltaic Solar Panel Cooling by a Flat Plate Closed-Loop Pulsating Heat Pipe. Solar Energy 2020, 206, 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.; Abou Akrouch, M.; Hachem, F.; Ramadan, M.; Ramadan, H. S.; Khaled, M. Cooling Techniques for Enhanced Efficiency of Photovoltaic Panels—Comparative Analysis with Environmental and Economic Insights. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17 (3), 713. [CrossRef]

- Sornek, K.; Goryl, W.; Figaj, R.; Dąbrowska, G.; Brezdeń, J. Development and Tests of the Water Cooling System Dedicated to Photovoltaic Panels. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15 (16), 5884. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Method used to enhance efficiency | Outcome/Remarks |

| Hamed et al. (2019) [16] |

Dual cooling Technique which involves front and back cooling using copper pipes with heat exchanger. | Temperature dropped significantly. Improves the average electrical PV efficiency. The optimal ratio of nanofluid concentration is 0.3%. The temperature dropped to 45°C, which resulted in improvement of PV efficiency of 10.9%. The optimal flow rate of nanofluid is 2L/min. |

| Nasir et al. (2020) [17] | Copper pipes bent into elliptical shape and bonded thermally to the back of PV panels. Two mono-crystalline and two poly-crystalline were used. | PV modules temperature dropped by 12°C. The mono-crystalline showed more improvement in efficiency (increase of 4.46%) compared to poly-crystalline (increase of 3.45%) |

| Jakhar et al. (2022) [18] | Developed a detail mathematical model of PV/T system with ground coupled heat exchanger (GCHE) with alumina/water nanofluid. | Temperature of PV panel reduced by 2°C. Decrease in temperature difference between the PV/T outlet and inlet by 6°C, an increase in electrical efficiency by 0.1%, and an increase in thermal efficiency by 4%. |

| Rostami et al., (2022) [19] | Nano-graphite/paraffin composite as phase change material(PCM). To slow down the melting of phase change material (PCM), a finned tube-heat exchanger was placed inside the PCM. | Higher water flow rate resulted in lower surface temperature of PV panel. Average surface temperature dropped from 336.15K to 310.25K with the usage of concentration of 0.01(w/v) nano-graphite PCM and water flow rate of 100mLs-1. Maximum enhancement was 21.2% at efficient condition. |

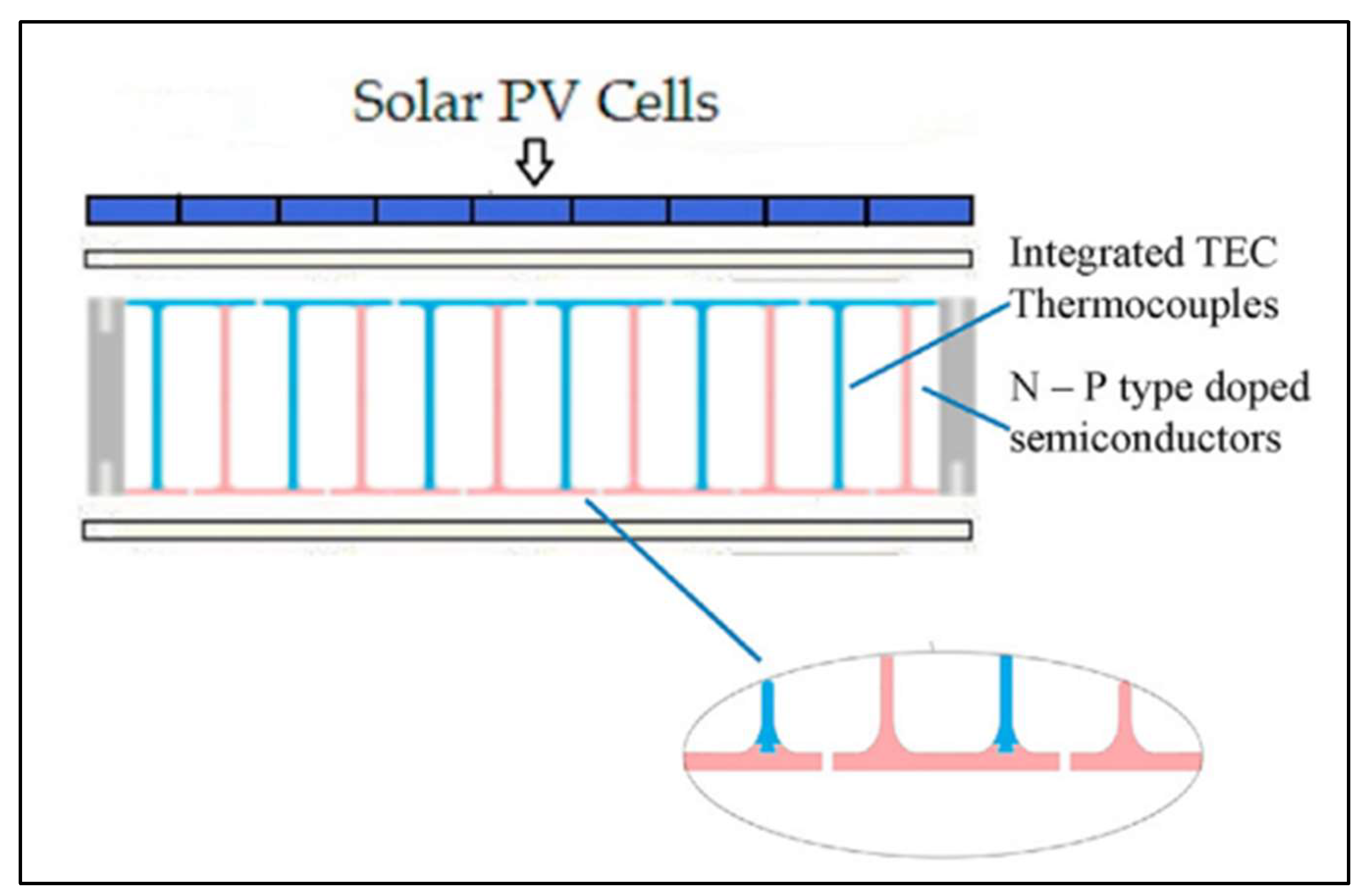

| Fabbri & Greppi (2021) [20] | The thermoelectric generator is included into the heat exchange system, using a fraction of the extracted heat to produce the necessary temperature gradient for the Seebeck effect to produce electrical energy. |

Enhance electrical power by almost 15%. Seebeck effect resulted in additional electrical power ranges from 61.2 to 71.2W. The maximum attainable system electrical power, accounting for all power gains and losses, is approximately 300–310 W/m2. |

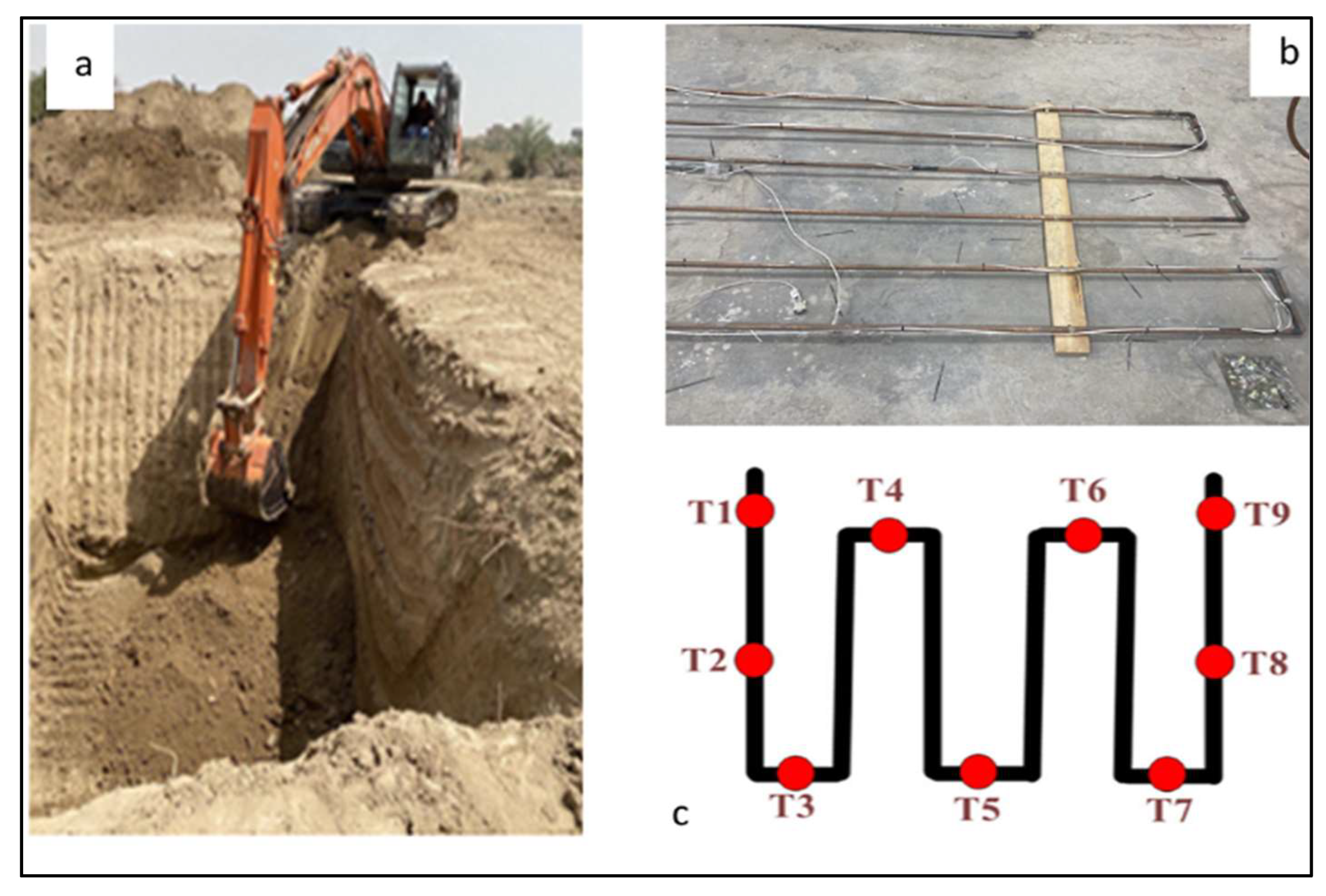

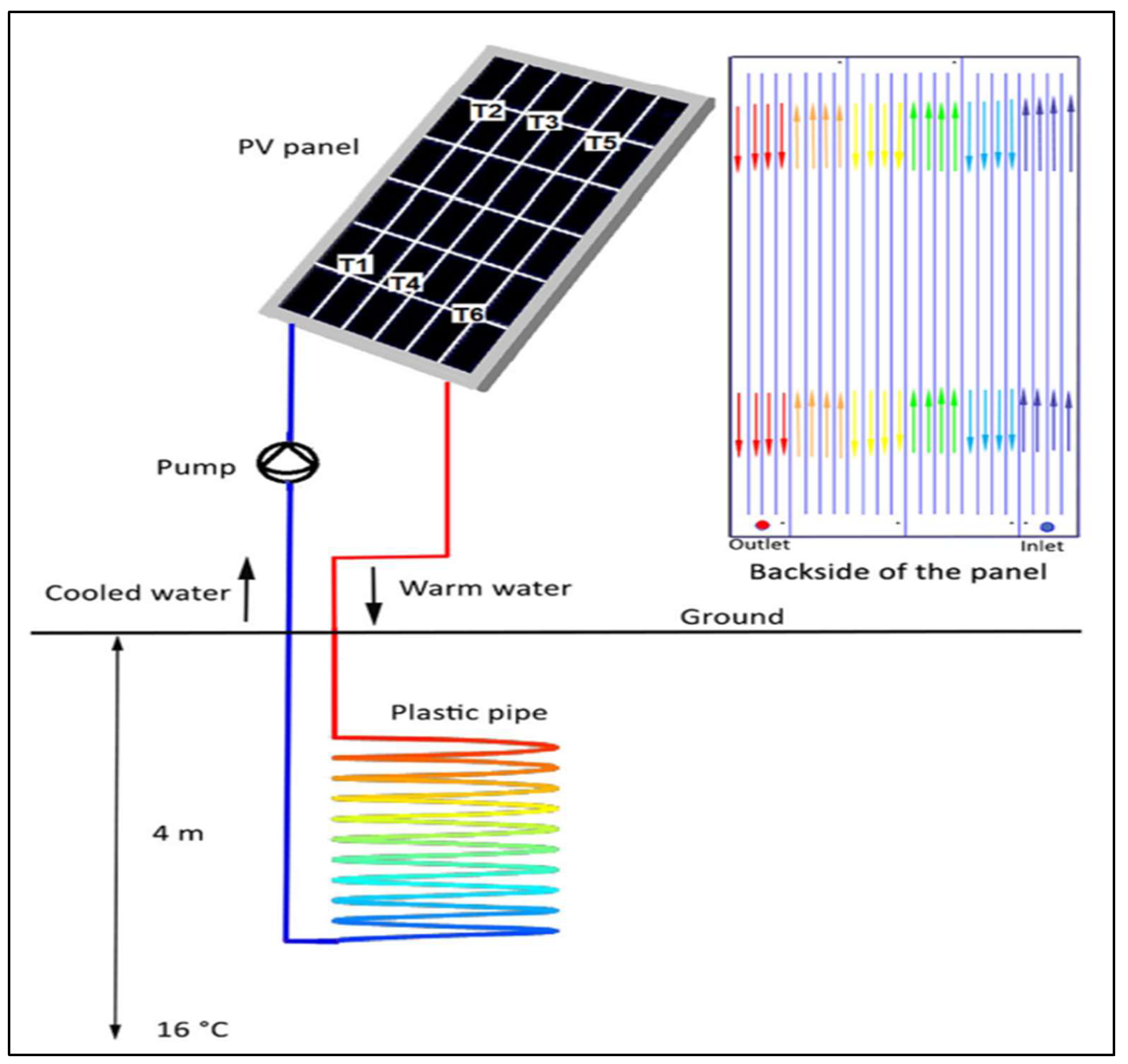

| Majeed et al., (2023) [21] | Monocrystalline PV panel and a spiral heat exchanger. A 3U-shaped copper tube is buried at a depth of 4 meters and has a total length of 22.25 meters. |

20°C difference observed between PV standalone and PVT system. The electrical efficiency increased by 127.3%. Water flow rate was 0.18L/s which caused almost zero vibration to the system. |

| Saftoiu & Morega (2023) [22] | Counter flow heat exchanger with pulsed fluid cooling. | The counter flow heat exchanger efficiently decreased the high temperatures on the PV panel. The pulsed cooling method improved the cooling process by periodically infusing cooling fluid resulting improvement in electrical efficiency caused by reduced operating temperatures. |

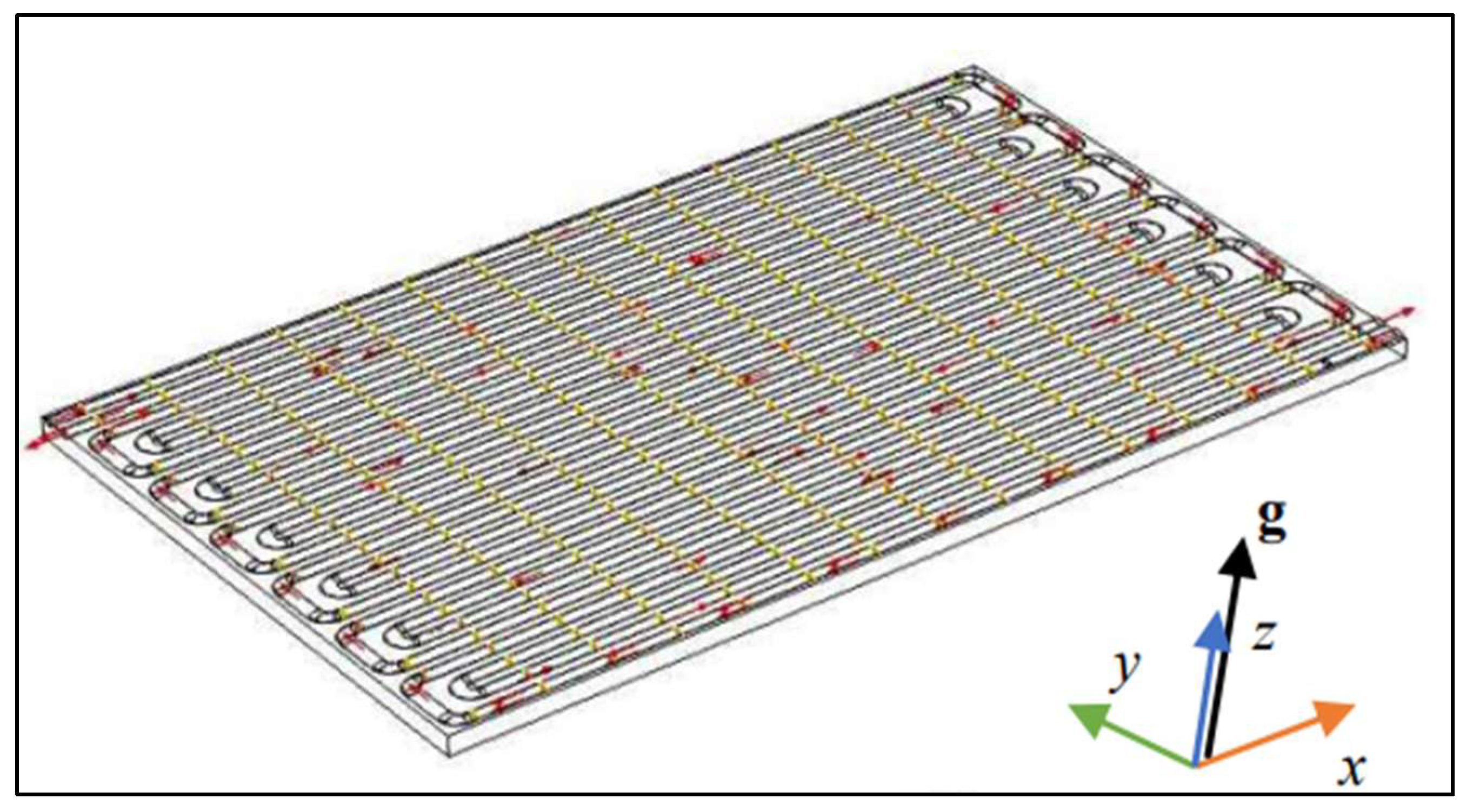

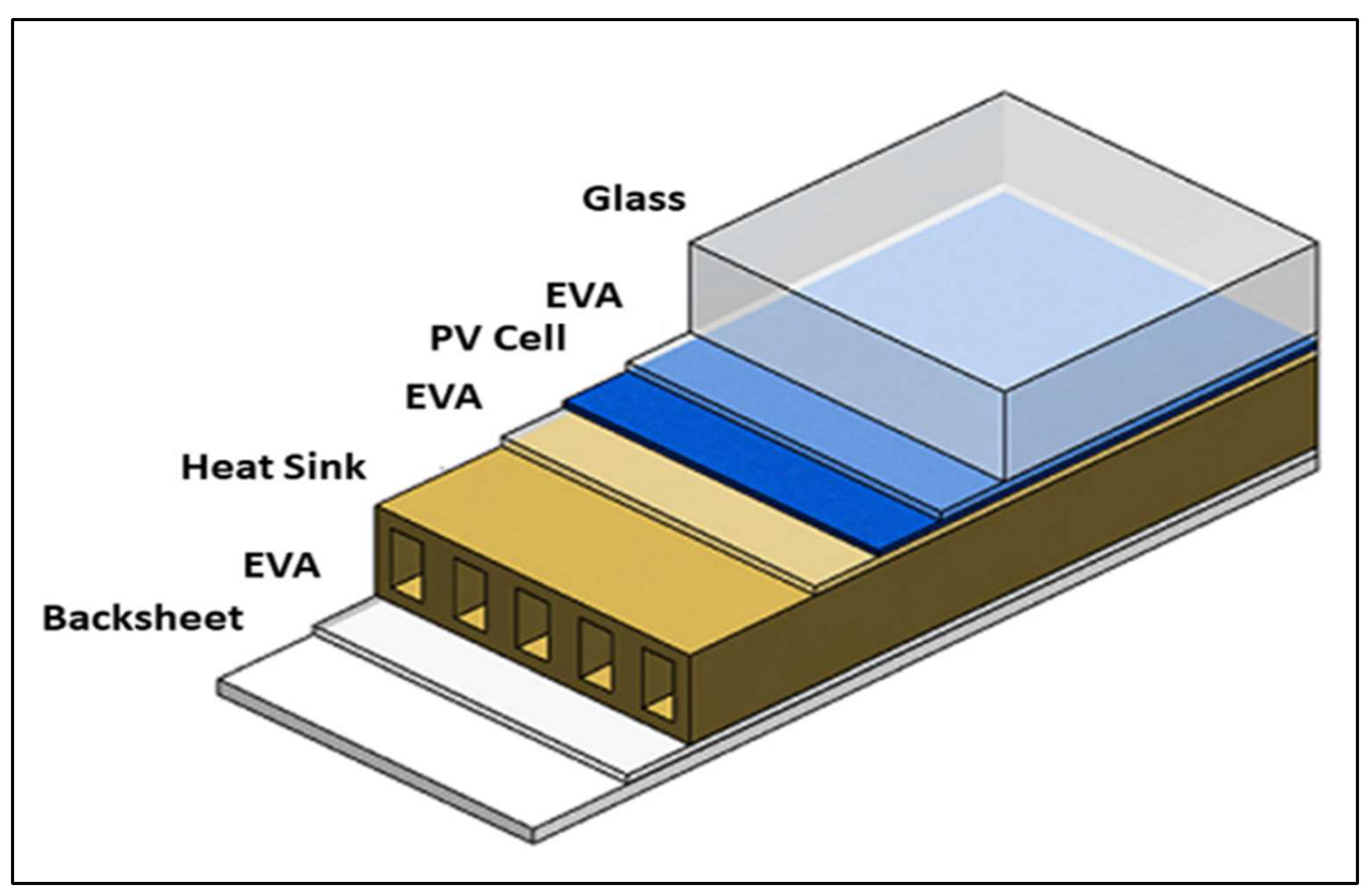

| Jafari et al., (2021) [23] | Ethylene Vinyl Acetate (EVA) was applied to standard photovoltaic cells before they were linked to a polymer minichannel heat exchanger on the rear and tempered glass on the front. |

The system showed a 10% improvement in daily power production due to efficient heat dissipation maintaining the PV cells at ideal temperatures. |

| Hudișteanu et al., (2020) [24] | Mounting water heat exchangers onto the rear side of the PV panels. |

The panels demonstrated an efficiency of around 11.4% under peak solar radiation. The efficiency was improved by roughly 12.23% with the cooling system operating. |

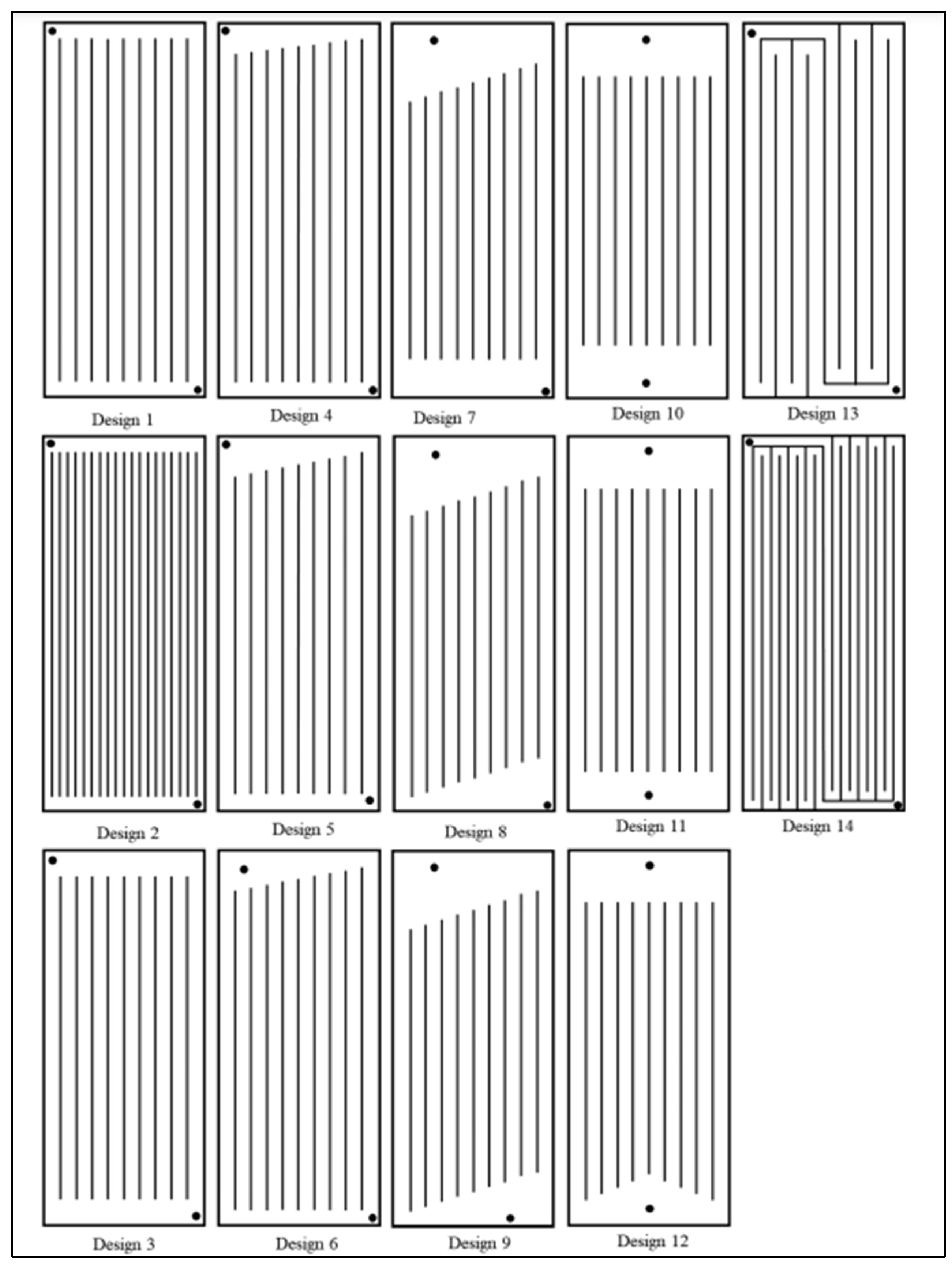

| Siddiqui et al., (2019) [25] | 14 distinct design criteria include channel numbers, manifold width, and the position and form of inlet/exit ports. |

Specific modifications in the heat exchanger design, such as altering manifold width and including V-shaped outlets, were shown to greatly influence performance by improving flow uniformity and decreasing temperature fluctuations. |

| Elminshawy et al., (2019) [26] | A photovoltaic panel connected to a geothermal air cooling system, particularly an earth-to-air heat exchanger (EAHE). |

The pre-cooled air lowered the PV module’s average temperature from 55°C to 42°C, resulting in an 18.90% increase in electrical output power and a 22.98% improvement in electrical efficiency. The improvements were most effective when the air flow rate was 0.0288 m³/s. |

| Yang et al., (2019) [27] | Incorporating a spray cooling system with a shallow geothermal energy heat exchanger. This system utilized water sprayed onto the back of the PV panels, which was then circulated via a U-shaped borehole heat exchanger (UBHE) to transfer heat with the geothermal energy in shallow soil layers. | The research discovered that implementing this configuration might enhance the panel efficiency by 14.3% in a plant industrial setting, with the equipment expenses of the system expected to be recouped within 8.7 years. |

| Li et al., (2024) [28] | PV/T system integrating a micro heat pipe with double-layer glass and a nanofluid |

During summer, the thermal collection efficiency reached a peak of 39.45%, while the power conversion efficiency peaked at 12.64% in winter. The investigation revealed that utilizing R141b as the operating fluid in the micro heat pipe greatly improved both thermal and power efficiency in comparison to conventional fluids such as acetone. |

| Authors | Method used to enhance efficiency | Outcome/Remarks |

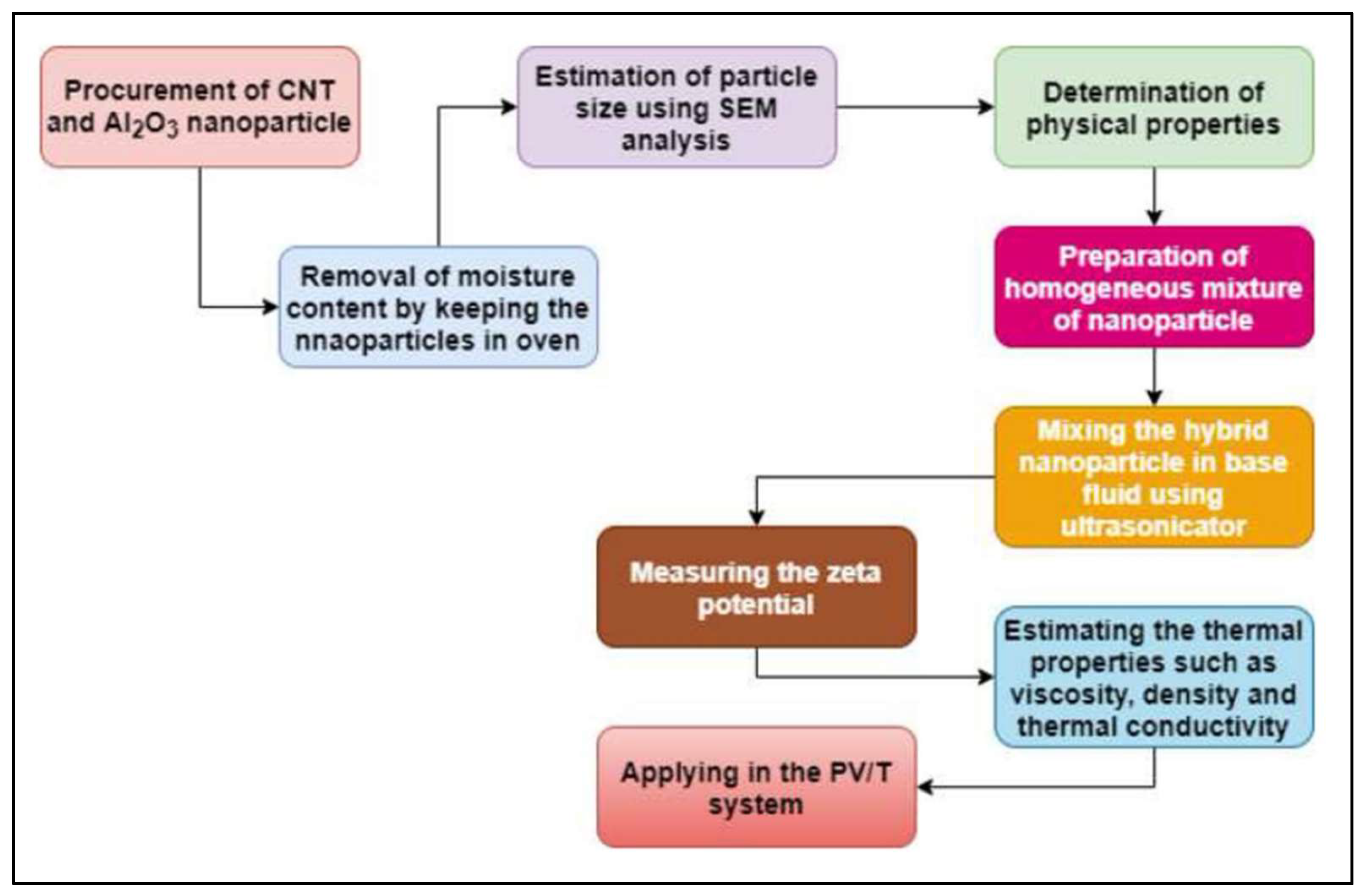

| Sathyamurthy et al., (2021) [29] | CNT/Al2O3 hybrid nanoparticles. Spiral tube collector and serpentine tube collector were studied | Combination of spiral tube with water and nanofluid improved the electrical efficiency to 7.15% and 8.2% respectively. Power production also increased by 11.7% using water and 21.4% using hybrid nanofluid. Overall enhancement is 27.3% compared to using water as medium. |

| Qeays et al., (2020) [30] | Hybrid photovoltaic thermal system with nanofluid cooling (HPVTS). Taguchi’s L16 orthogonal array. | HPVTS optimal performance was achieved for 800 W/m2 irradiance, 25°C ambient temperature, 0.5 L/min flow rate and 0.5% concentration of nanofluid. |

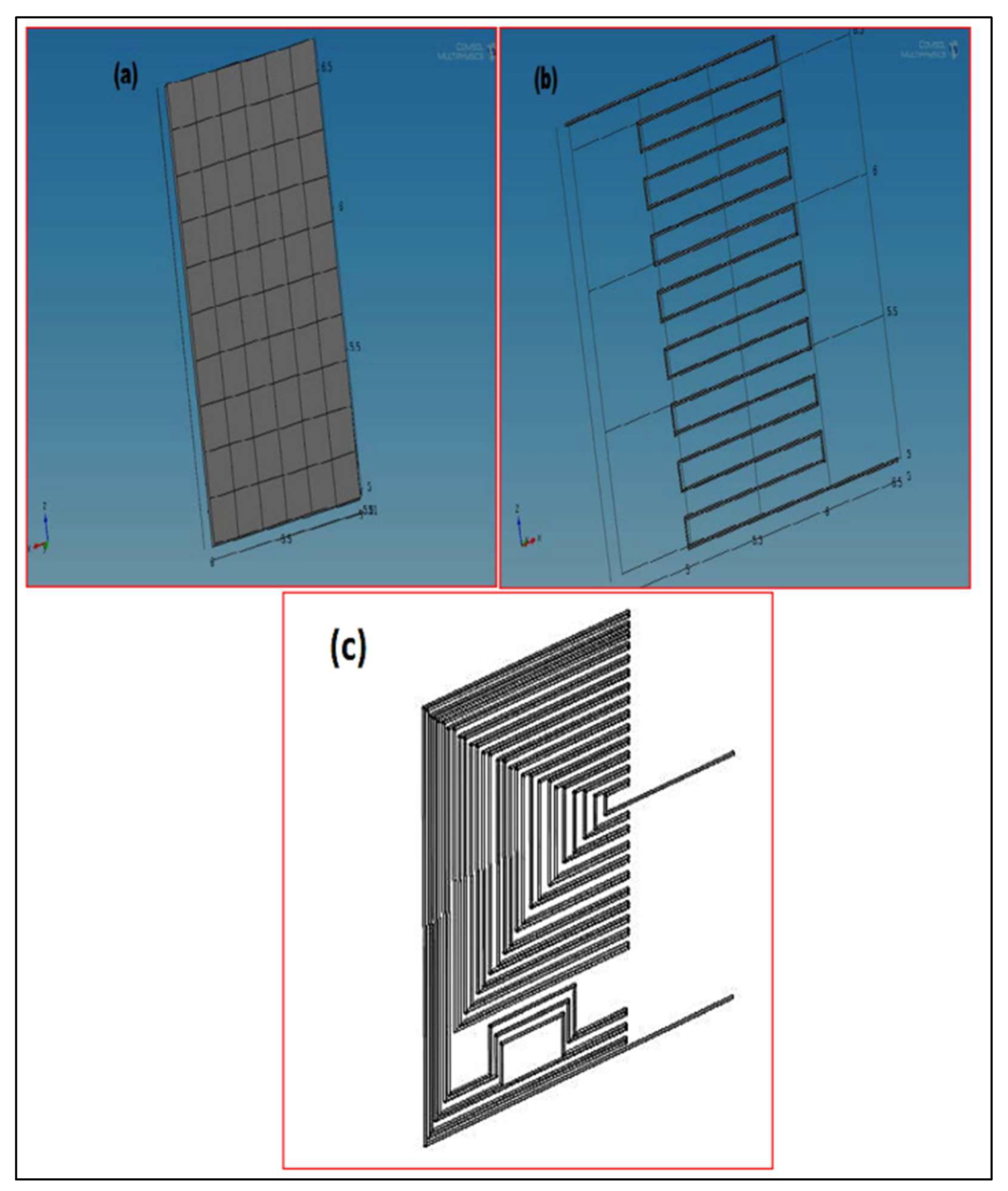

| Bayoumi et al., (2021) [31] | Uses Comsol Multiphysics software. Utilizes Finite Element Method together with Matlab program to simulate the model. Different back pipes structures. Serpentine and new square shape pipes. Nanofluid Cuo/water is used. |

The power production improved from 223W for serpentine shape to 236W for the square shape with water. Using CuO nanofluid further improved power output to 246W. |

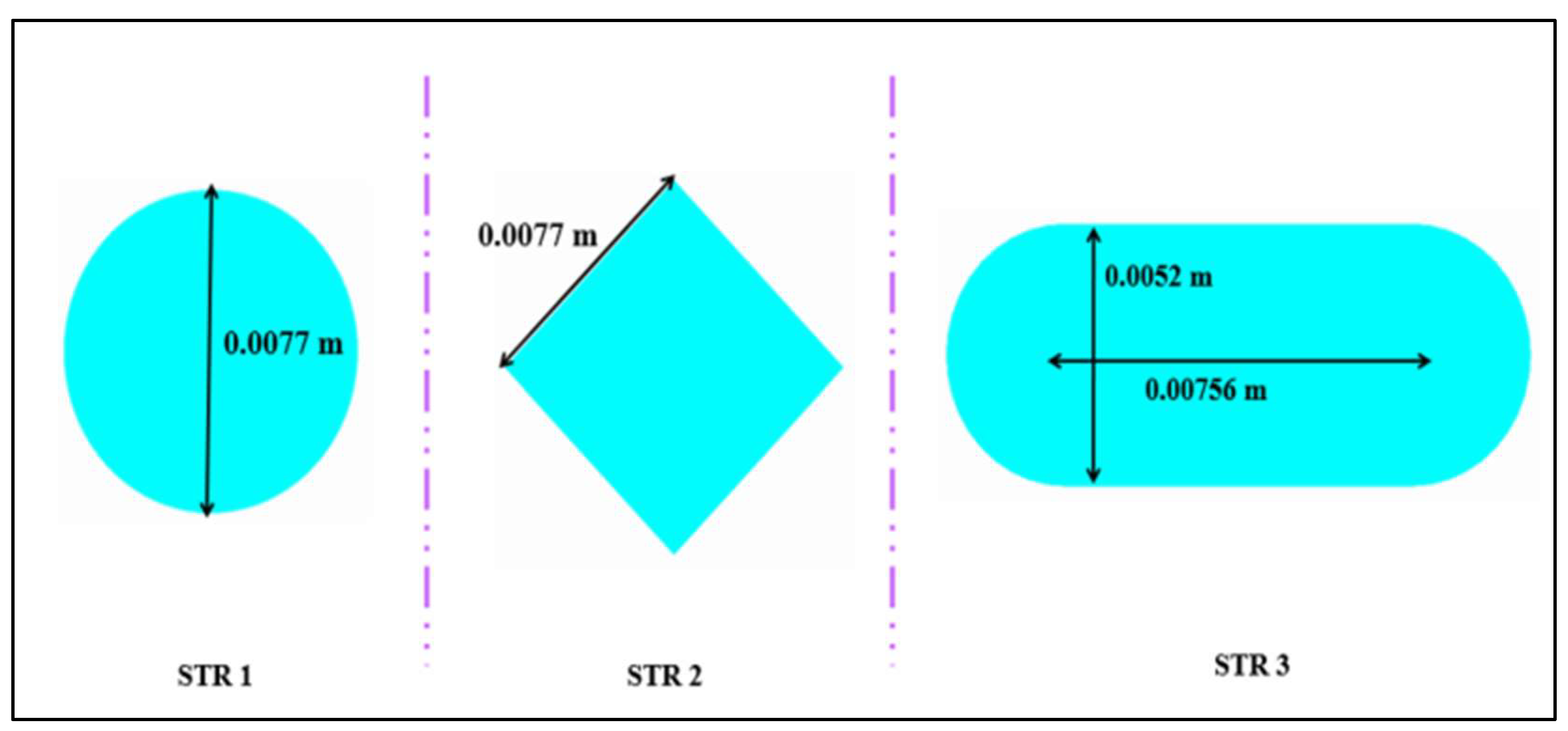

| Khalili et al., (2023) [32] | Cooling duct positioned at bottom of PVT-TEG unit. Hybrid nanofluid Fe3O4 and MWCNT with water. Three cross section configurations (circular, rhombus and elliptic). | Elliptic duct showed the best result with 6.29% improvement. Thermal and electrical performances for elliptic design are 14.56% and 55.42% respectively. Compared to uncooled system the improvement is 16.2%. |

| Abdeldjebar et al., (2023) [33] | Al2O3-water nanofluid with constant horizontal velocity. | The flow intensity was highest near the pipe’s symmetry axis, and the temperature dispersion was enhanced by adding nanoparticles. Higher Reynolds numbers often decrease heat dissipation efficiency, indicating that less velocity might be more advantageous for efficient cooling of solar panels. Higher concentration of nanofluid resulted in better heat transfer. |

| Shahad et al., (2021) [34] | Sic/Water nanofluid used to cool monocrystalline PV panel. Two concentrations of nanofluid 0.1% and 0.5% | Using a 0.5% nanofluid concentration at a flow rate of 2 L/min led to a 50% rise in electrical efficiency and an 82.41% improvement in total efficiency in March. The June observations showed minimal improvements with a nanofluid concentration of 0.1% and a flow rate of 0.5 L/min, resulting in increases of 35.4% and 34.01%, respectively. The experimental findings closely matched the theoretical predictions, with an average variance in electrical efficiency of around 5.58% in March and 11% in June. |

| Ebaid et al., (2020) [35] | Two water based nanofluid used which are titanium dioxide (TiO2) and Aluminum Oxide (Al2O3) with 0.01%, 0.05% and 0.1% wt concentrations. Three monocrystalline silicon PV panel tested. | The Nusselt number investigation showed that the TiO2 nanofluid with a concentration of 0.1 wt% yielded the most effective heat transmission results. |

| Abdollahi & Rahimi (2020) [36] | PCM and Boehmite nanofluid. Nanofluid concentrations used were 0.02, 0.06 and 0.1% wt. Helical tube is used to enhance the cooling. | At a flow rate of 18.91 mL/s, a nanofluid concentration of 0.1 wt.% resulted in the most significant decrease in panel temperature and the greatest enhancement in power output, leading to a 58.8% gain in electrical power efficiency. |

| Ebaid et al., (2018) [37] | Suspension of Al2O3 and TiO2 nanoparticles in water-polyethylene glycol and water- cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Concentrations used are 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1% wt. Heat exchanger with aluminium rectangular cross-section was fixed to the rear surface of the PV panel | The Al2O3 nanofluid exhibited superior cooling efficiency compared to the TiO2 nanofluid. Increased nanofluid concentrations typically resulted in improved cooling effects over the whole range of flow rates examined. The TiO2 nanofluid improved power and efficiency more effectively than water cooling in different flow rates and concentrations, as shown by electrical performance analysis. |

| Rostami et al., (2018) [38] | The experiment used atomized CuO nanofluid at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 0.8 w/v, together with atomized pure water as cooling liquids. Nanofluid and high frequency ultrasound were utilized to generate a cold vapor, which was subsequently applied to the PV module to improve cooling and efficiency. | The 0.8 w/v nanofluid with the highest concentration reduced the module’s average surface temperature by 57.25% and increased the maximum amount of power produced by 51.1% compared to the configuration without a cooling system. |

| Authors | Methods used to enhance efficiency | Outcome/Remarks |

| Vaziri Rad et al., (2021) [39] | Aluminium shaving combined with salt hydrate phase change material (PCM) into a water-based photovoltaic (PV/T) thermal system | Average temperature reduced by 24% and also electrical efficiency by 2.5% compared to standalone PV panel. The melting period of PCM reduced from 19% to 25% due to improved thermal conductivity by the porous material. |

| Kiwan et al., (2020) [40] | PCM used was paraffin graphite panel covered with an aluminium sheet for better heat dissipation | PCM improved the efficiency of the system. The efficiency ranged from 10% to 12%. If the cell temperature doesn’t surpass the melting temperature of PCM it affects the efficiency negatively because the PCM will act as thermal insulator. |

| Aneli et al., (2021) [41] | Rubitherm RT28 and RT35 PCM is combined with PV module | PV-PCMRT35 shows lower temperature the whole day compared to conventional module maximum difference was 20°C at noon. From 6.00am to 10.00am PV-PCMRT28 showed the lowest cell temperature. 10% increase in peak power also 3.5% improvement in annual energy production compared to traditional PV modules. |

| Badi et al., (2023) [42] | PCM-OM37P pack were attached to the rear of the panel | Temperature reduction improved from 5°C to 6°C during peak hours. Voltage drop improvement seen at least 0.6V. Power Enhancement Percentage were around 3% observed. |

| Rajaee et al., (2020) [43] | Cooling with Co3O4/water nanofluid of different concentrations. Another study where PCM (paraffin wax combined with Alumina powder) and nanofluid combined was conducted | Utilizing a 1% Co3O4/water nanofluid as the coolant increased the total electrical efficiency by 12.28% in comparison to utilizing only water. Compared to water cooling, an improved PCM and nanofluid increased exergy efficiency by 11.6%. |

| Bayrak et al., (2020) [44] | Different methods used including PCM, thermoelectric modules (TEM) and aluminum fins | Fins showed highest cooling result which is 47.88W power generated compared to PCM and TEM which resulted in 44.26W. |

| Elavarasan et al., (2020) [45] | OM29 PCM was coated directly to the back of the PV module, removing any barriers to heat conduction and enabling direct heat transfer from the panel to the PCM. |

By integrating OM29 PCM directly on the rear surface of the PV module, the temperature fell by up to 1.2°C by 08:30 AM. After 09:00 AM, OM29 could not continue the cooling effect because it could not preserve the latent heat characteristics for long durations. The PCM back sheet proved poor in dispersing stored thermal energy, rendering it unsuitable for high-temperature applications. |

| Jamil et al., (2021) [46] | Nano phase change material (nano-PCMs). Three different nano-PCMs Combining multiwall carbon nanotubes, graphene nanoplatelets, and magnesium oxide nanoparticles with a phase transition material known as PT-58. Concentrations used are 0.25 wt% and 0.5 wt%. |

The panels coated with 0.5 wt% concentration graphene nanoplatelets/PT-58 nano-PCM showed the greatest decrease in temperature and electrical effectiveness. The biggest temperature decrease recorded was 9.94°C at a concentration of 0.5 wt% of graphene nanoplatelets, while the greatest increase in electrical power was 33.07% for the same setup. |

| Zhao et al., (2019) [47] | Analysis made using 1-D thermal resistance model created with MATLAB. Five distinct photovoltaic-phase change material (PV-PCM) systems were modeled using actual meteorological data from Shanghai in 2017, each including various phase change materials (PCMs). |

The greatest annual increase in power production was around 2.46% when compared to a conventional PV system lacking PCM. |

| Selabi et al., (2021) [48] | Composite PCM-metal matrix implementation. Different PCM were tested which are CaCl2-6H2O, paraffin wax, RT25, RT27, SP29 and n-octadecane paired with metals such as copper, aluminium, steel and nickel and polymers such as polystyrene and polypropylene for composite matrix. | RT25, when combined with a metal matrix, showed superior compatibility by effectively regulating the temperature of the PV cell at lower levels in comparison to other PCM varieties. |

| Marudaipillai et al., (2023) [49] | Uses polyethylene glycol/expanded graphite to create a stable phase change material (FSPCM) |

With reductions of 11.5°C for the FSPCM setup and 9.45°C for the heat sink setup, the application of FSPCM led to a notable decrease in PV panel surface temperature when compared to the heat sink approach. The FSPCM-equipped PV panel demonstrated an overall efficiency improvement of 3.667%, outperforming the typical cooling technology (heat sink) which achieved 1.072%. |

| Karthikeyan et al., (2020) [50] | A thermal heat transfer network was created to enhance the efficiency of the PV module by utilizing radiation mode to address the problem of PCM re-conduction. | The PV module with composite PCM achieved an efficiency of 14.75% and a temperature of 47.81°C when the optimum thickness of 2.5 cm was used. The results showed that the composite PCM had superior thermal conductivity, leading to improved heat dissipation compared to pure PCM. |

| Arıcı et al., (2018) [51] | A numerical model is concentrated on maximizing the parameters of the PCM layer. Numerical analysis using a one-dimensional finite volume approach. | The findings demonstrated that PV panels’ working temperature can be considerably lowered by up to 10.26°C when PCMs are used, leading to an increase in efficiency of up to 3.73%. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).