Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Products with SAT

3.2. Analysis of HTA Opinions in Selected EU Countries

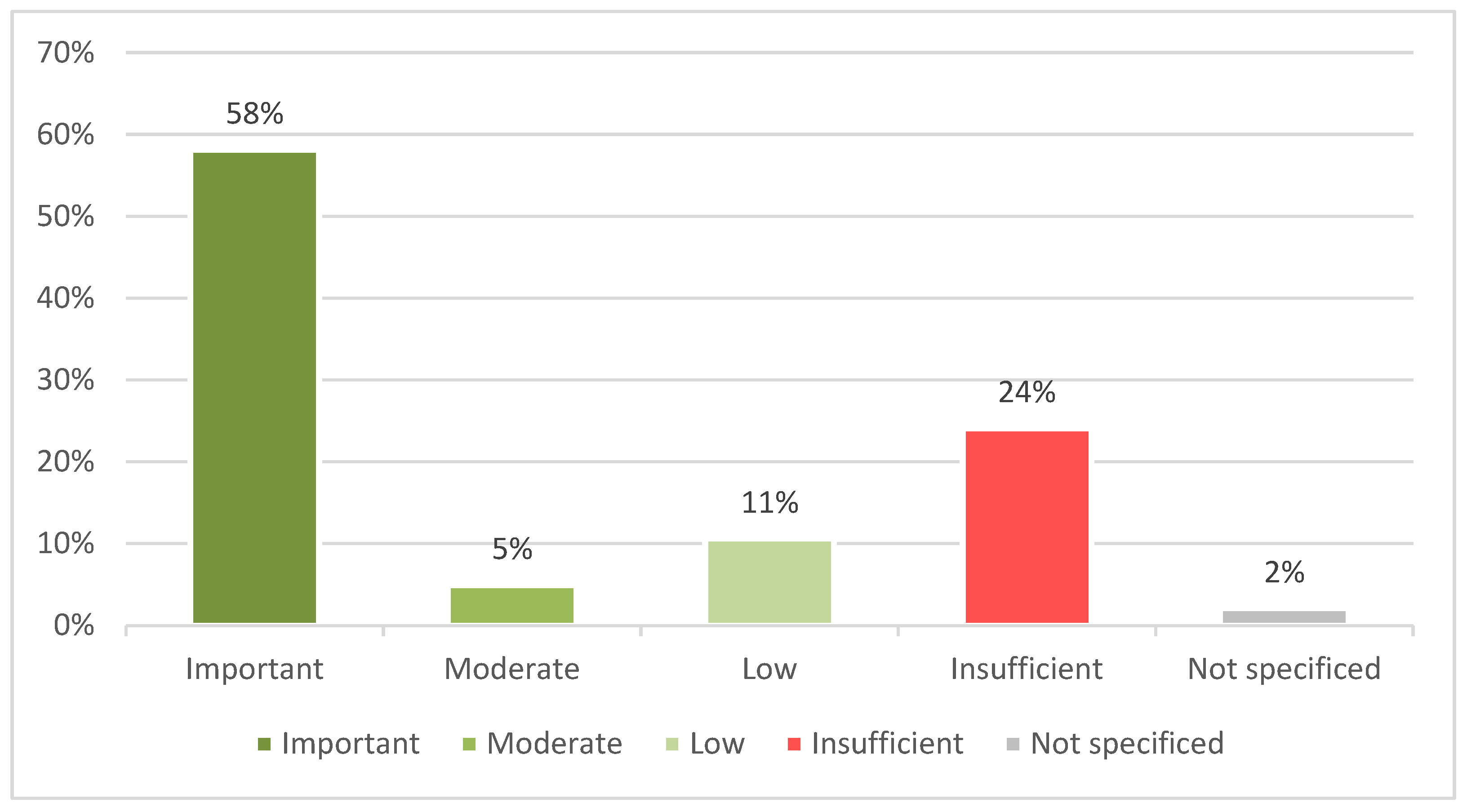

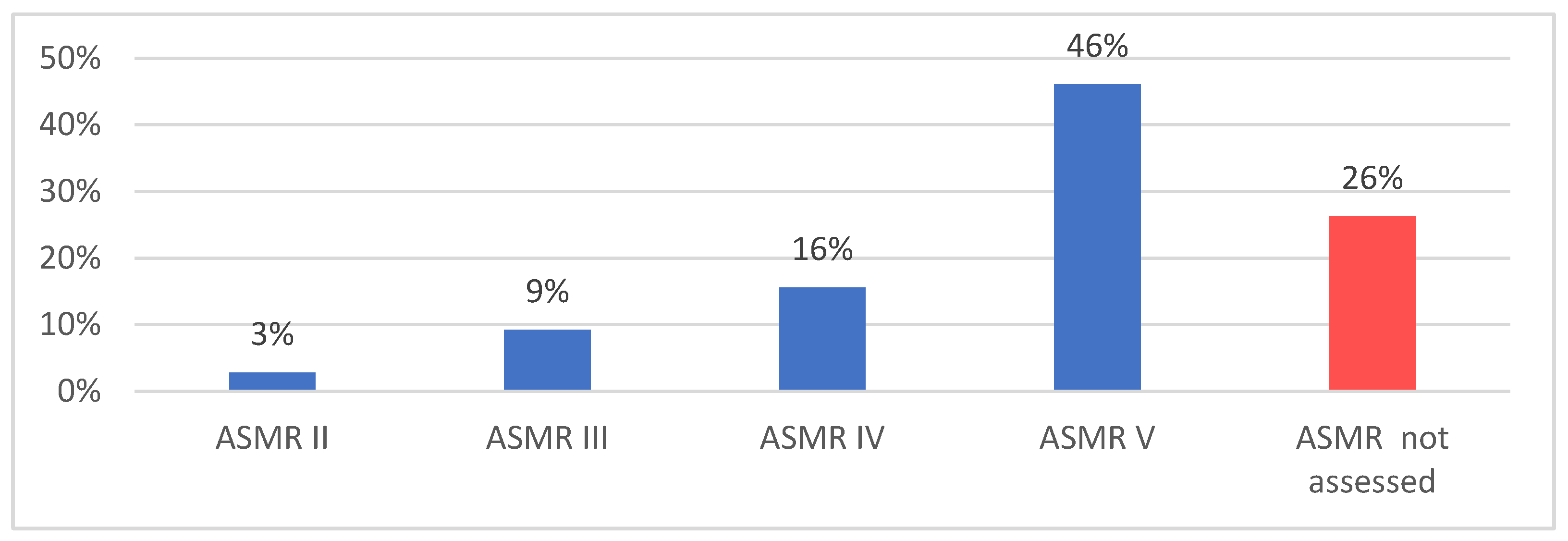

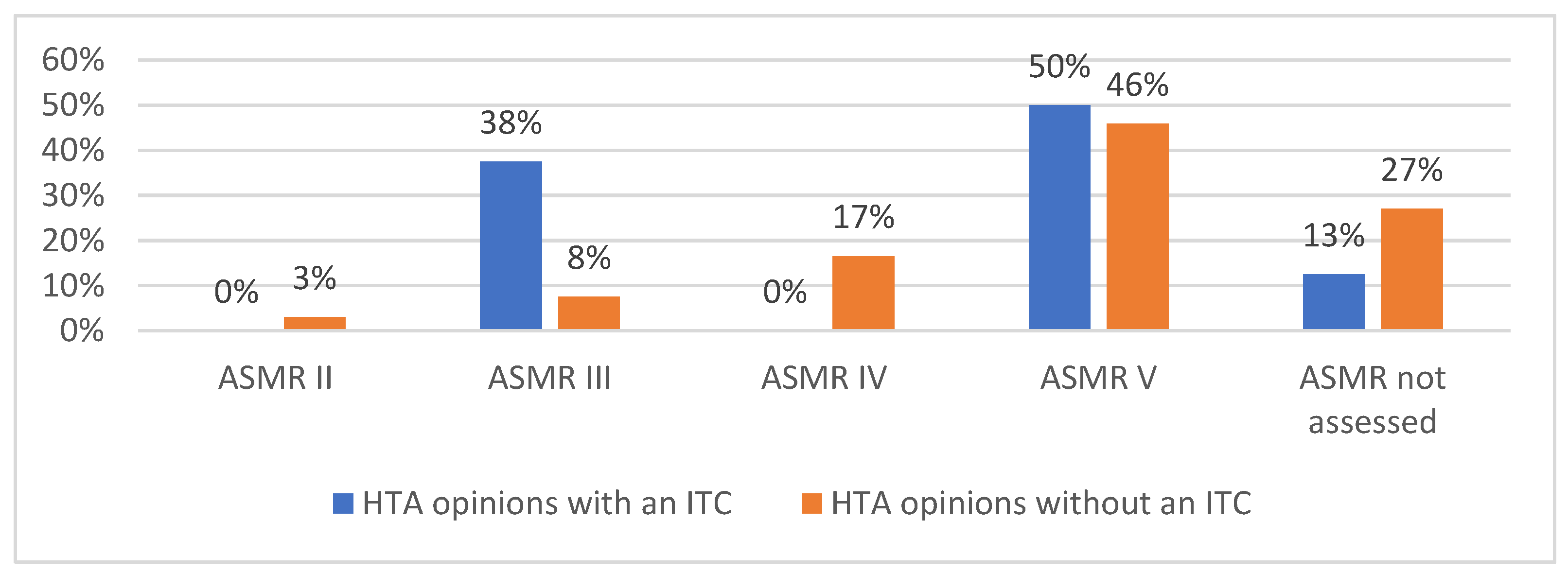

3.1.1. France

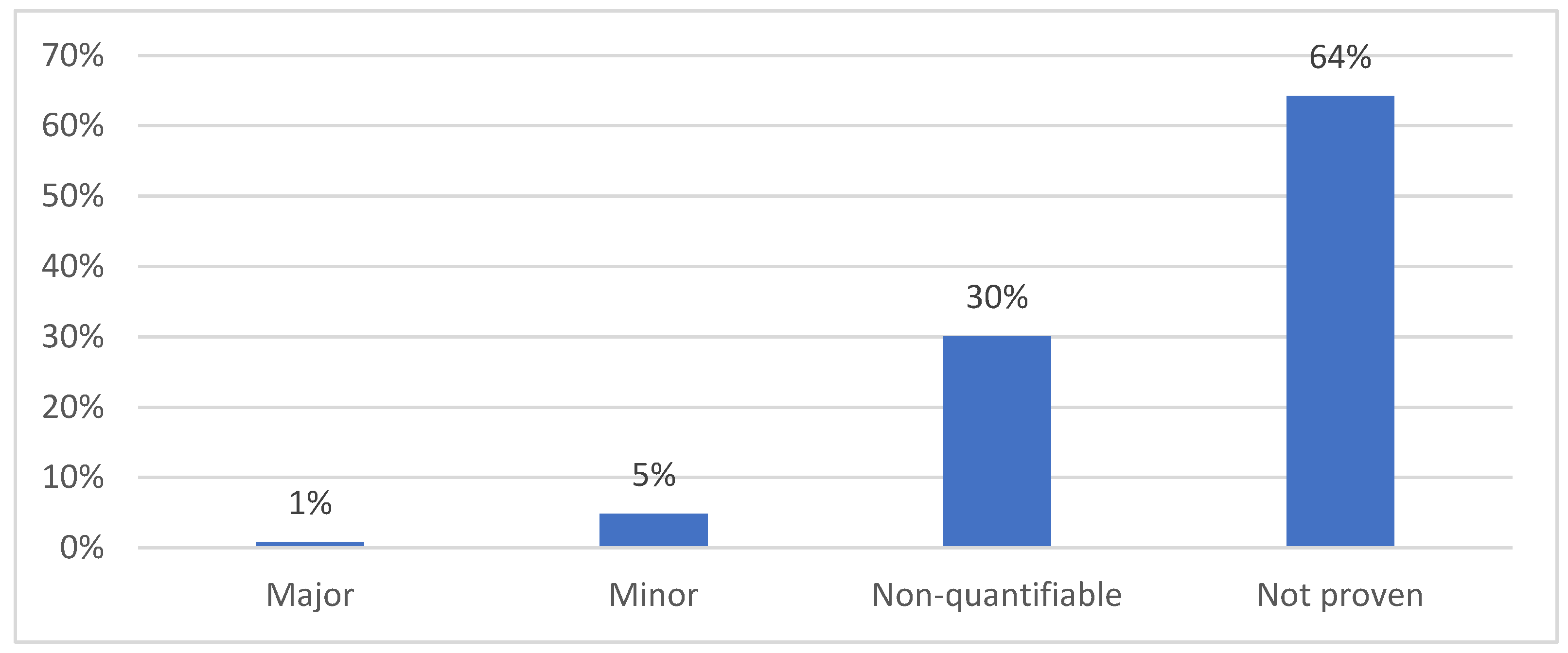

3.1.2. Germany

3.1.3. Poland

3.1.4. Spain

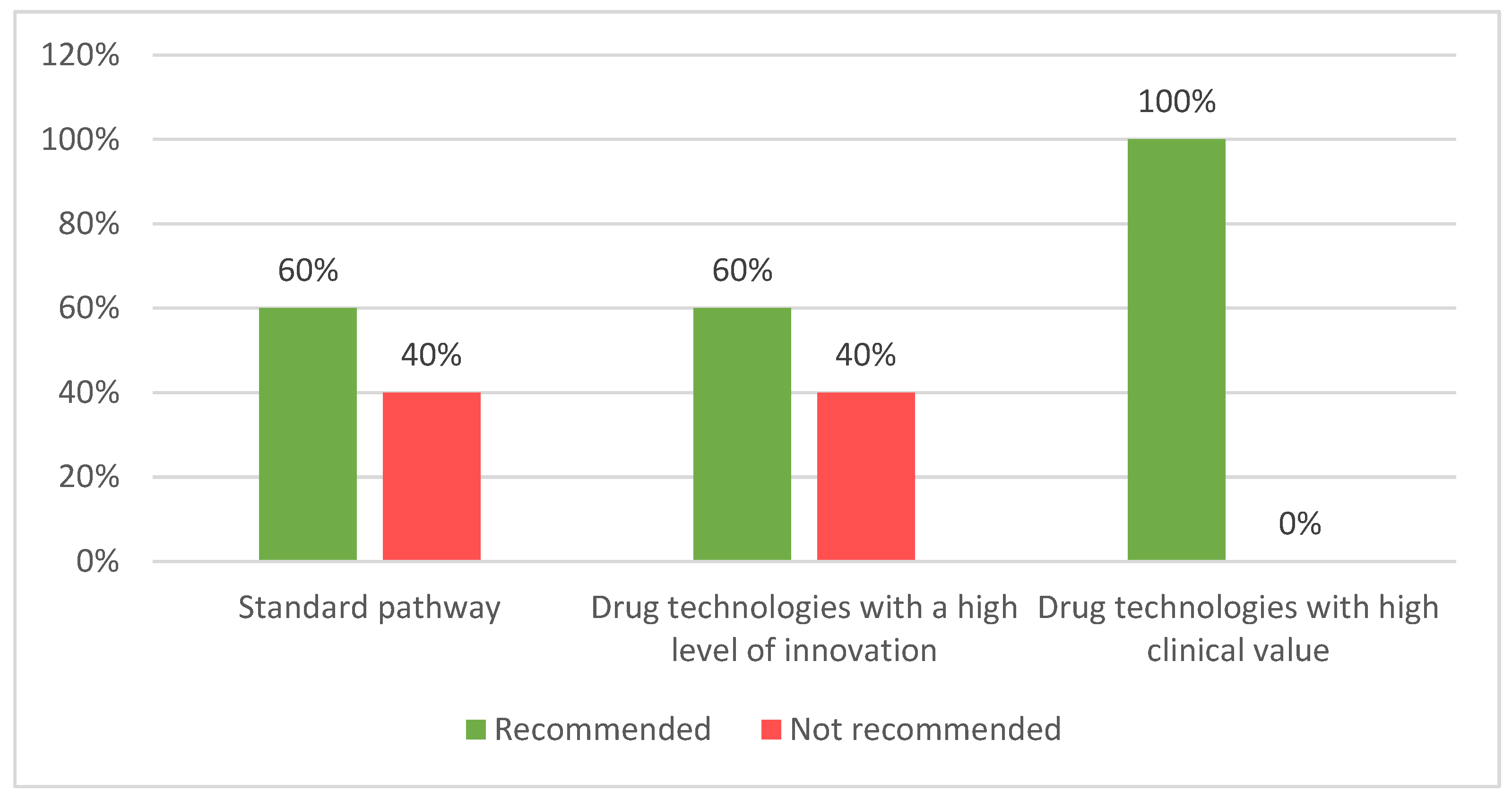

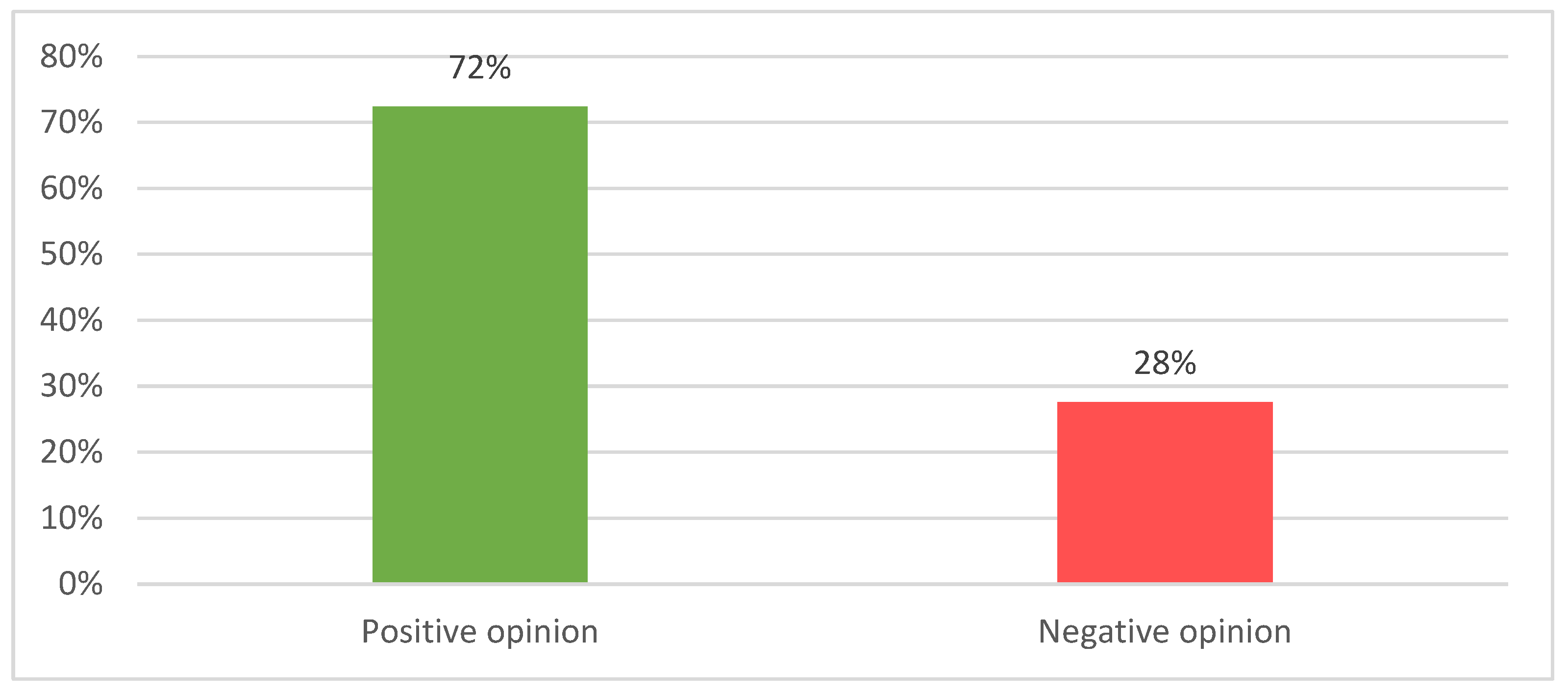

3.2. Simulation of JCA of Drugs Supported by SATs and Comparison with National HTA Opinions

4. Discussion

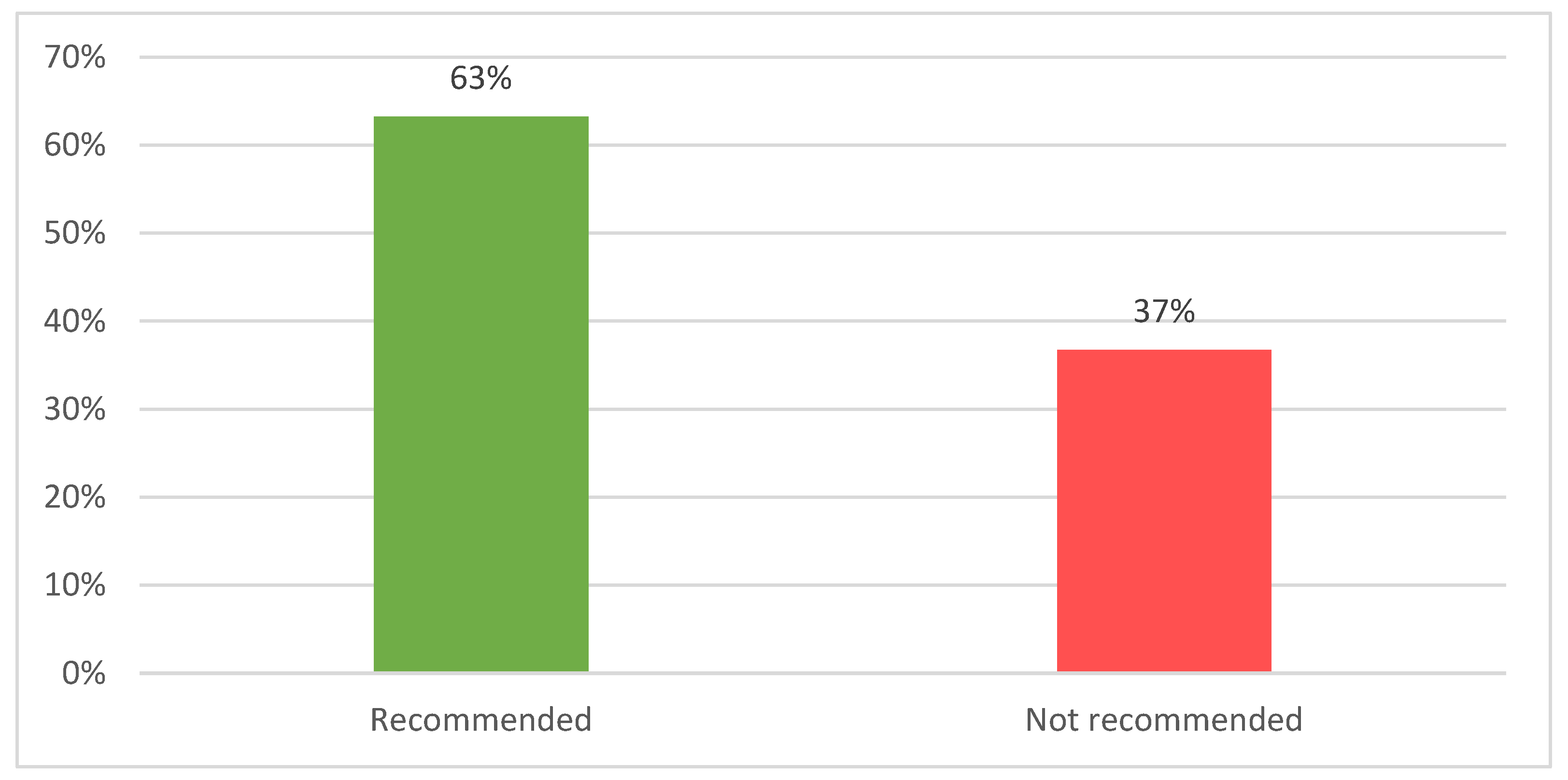

4.1. SAT-Supported Products Enjoy a Fair Recognition

4.2. The Low Value of JCA for SAT-Supported Products Justifies Their Exemption from JCA

- Prevent potential restrictions on access to important interventions;

- Align with current HTA practices that often favour SAT-supported products;

- Reduce workload for already stretched Member State Coordination Group on Health Technology Assessment (HTACG) resources.

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Contextualisation and deliberative processes are critical for SAT and, by essence, overlooked in JCA.

- If JCA express a negative opinion for SAT-supported products and this opinion impacts negatively availability at MS level, it will contradict the primary strategic objective of EU-HTA regulation.

- If JCA express a negative opinion for SAT-supported products and this opinion does not affect the decision of MS to grant a high rate of availability, this would evidence low impact of JCA.

- The JCA process is unlikely to impact the decision of HTD to engage in SAT development.

- Exempting SAT from JCA is unlikely to increase the number of SAT-supported medicinal products.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASMR | Improvement in the actual benefit |

| ATMP | Advanced therapy medicinal products |

| EMA | European Medicine Agency |

| EU | European Union |

| HTA | Health Technology Assessment |

| HTD | Health Technology Developers |

| ITC | Indirect treatment comparison |

| JCA | Joint Clinical Assessment |

| MAIC | Matching-adjusted indirect comparison |

| MS | Member States |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes |

| RCT | Randomized control trials |

| RE | Relative effectiveness |

| SATs | Single-arm trials |

| SMR | Rating of actual benefit |

References

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2024/1381 of 23 May 2024 laying down, pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2021/2282 on health technology assessment, procedural rules for the interaction during, exchange of information on, and participation in, the preparation and update of joint clinical assessments of medicinal products for human use at Union level, as well as templates for those joint clinical assessments. 23 May 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L_202401381 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the EU. Regulation (EU) 2021/2282 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2021 on health technology assessment and amending Directive 2011/24/EU (Text with EEA relevance). 15 December 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/2282 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- European Commission. Joint Clinical Assessments. 2025. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/health-technology-assessment/implementation-regulation-health-technology-assessment/joint-clinical-assessments_en (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Gentilini, A.; Parvanova, I. Managing experts’ conflicts of interest in the EU Joint Clinical Assessment. BMJ Open 2024, 14(11), e091777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HTA Coordination Group. Guidance on outcomes for joint clinical assessments. 10 June 2024. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/a70a62c7-325c-401e-ba42-66174b656ab8_en?filename=hta_outcomes_jca_guidance_en.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- European Commission. Implementation Rolling Plan. 10 January 2025. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/397b2a2e-1793-48fd-b9f5-7b8f0b05c7dd_en?filename=hta_htar_rolling-plan_en.pdf.

- HTA Coordination Group. Methodological Guideline for Quantitative Evidence Synthesis: Direct and Indirect Comparisons. 8 March 2024. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/4ec8288e-6d15-49c5-a490-d8ad7748578f_en?filename=hta_methodological-guideline_direct-indirect-comparisons_en.pdf&prefLang=el#:~:text=The%20objective%20of%20this%20document%20is%20to%20describe,comparisons%2C%2 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- HTA Coordination Group. Guidance on Validity of Clinical Studies. 04 July 2024. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/9f9dbfe4-078b-4959-9a07-df9167258772_en?filename=hta_clinical-studies-validity_guidance_en.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Wang, M.; et al. Single-arm clinical trials: design, ethics, principles. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2024, 15(1), 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMA. Single-arm trials as pivotal evidence for the authorisation of medicines in the EU. 21 April 2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/single-arm-trials-pivotal-evidence-authorisation-medicines-eu (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- GlobalData. Pharmaceutical Prices (POLI) Database . Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/marketplace/pharmaceuticals/pharmaceutical-prices-poli-database/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- EMA. Download medicine data. Orphan designations . 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/download-medicine-data#orphan-designations-69050 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- EMA. Download medicine data . Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/download-medicine-data (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- G-BA. Benefit Assessment of Medicinal Products with New Active Ingredients according to Section 35a SGB V Cer-liponase Alfa (reassessment after the deadline (type 2 neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis)) . 2022. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/downloads/40-1465-9111/2022-12-15_AM-RL-XII_Cerliponase-Alfa_D-849_TrG_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- G-BA. Benefit Assessment of Medicinal Products with New Active Ingredients according to Section 35a SGB V Cemiplimab (new therapeutic indication: basal cell carcinoma, locally advanced or metastatic) . 2022. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/downloads/40-1465-8181/2022-01-20_AM-RL-XII_Cemiplimab_D-706_TrG_EN.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- G-BA. Beschlüsse über die Nutzenbewertung von Arzneimitteln mit neuen Wirkstoffen nach § 35a SGB V - Sofosbuvir . 2014. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/downloads/40-268-2899/2014-07-17_AM-RL-XII_Sofosbuvir_2014-02-01-D-091_TrG.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Navlin. Novartis Withdraws Tabrecta in Germany . 2023. Available online: https://www.navlindaily.com/article/18714/novartis-withdraws-tabrecta-in-germany (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Ned, P. Bluebird to withdraw gene therapy from Germany after dispute over price. 20 April 2021. Available online: https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/bluebird-withdraw-zynteglo-germany-price/598689/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- EMA. Gavreto (pralsetinib) - Withdrawal of the marketing authorisation in the European Union. 17 January 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/public-statement/public-statement-gavreto-withdrawal-marketing-authorisation-european-union_en.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- AOTMiT. Assessment of reimbursement applications. June 2024. Available online: https://www.aotm.gov.pl/en/medicines/assessment-of-reimbursement-applications/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Fundusz Medyczny. D Subfundusz Terapeutyczno_Innowacyjny (STI) . 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/d-subfundusz-terapeutyczno-innowacyjny-sti (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Macabeo, B.; et al. The Acceptance of Indirect Treatment Comparison Methods in Oncology by Health Technology Assessment Agencies in England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Pharmacoecon Open 2024, 8(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remuzat, C.; Toumi, M.; Falissard, B. New drug regulations in France: what are the impacts on market access? Part 1 - Overview of new drug regulations in France. J Mark Access Health Policy 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HAS. Transparency Committee doctrine. 02 December 2020. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-07/doctrine_de_la_commission_de_la_transparence_-_version_anglaise.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Ivandic, V. Requirements for benefit assessment in Germany and England - overview and comparison. Health Econ Rev 2014, 4(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranz, P.; et al. Results of health technology assessments of orphan drugs in Germany-lack of added benefit, evidence gaps, and persisting unmet medical needs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2024, 40(1), e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, S.; et al. The Evaluation of Orphan Drugs by the German Joint Federal Committee-An Eight-Year Review. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020, 117(50), 868–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IQVIA. HTA Uncovered. July 2016. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/library/white-papers/hta-uncovered-july-2016.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Heidbrede, T.; et al. Health technology assessments of single-arm clinical trials in Germany and France; ISPOR Poster 121937, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, A.; Santos, S. Use of single arms studies for Health Technology Assessment in Portugal; ISPOR Poster, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- HTA Coordination Group. Practical Guideline for Quantitative Evidence Synthesis: Direct and Indirect Comparisons . 2024. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/1f6b8a70-5ce0-404e-9066-120dc9a8df75_en?filename=hta_practical-guideline_direct-and-indirect-comparisons_en.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- G-BA. Benefit Assessment of Medicinal Products . 2025. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/english/benefitassessment/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Blümel, M.; et al. Germany. Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition 2020, 22(6), i-273. [Google Scholar]

| HTA framework | Number of products with SAT | Number of products assessed | Number of products accepted 1 | Acceptability rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 96 | 96 | 82 | 85% |

| Germany | 65 | 61 | 94% | |

| Poland | 40 | 36 | 90% | |

| Spain | 46 | 35 | 76% | |

| JCA | 6 2 | 0 3 | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).