1. Introduction

Nowadays, AI can be employed in almost every aspect, segment and domain of a mobile network, enabling automated network operation and user service support [

1]. The network architecture in 6G will comprise a fully end-to-end Machine Learning (ML) and model accessibility, encompassing autonomic networking by taking advantage of AI/ML capabilities. Different AI/ML algorithms (e.g., supervised, unsupervised, federated or reinforcement learning) are having different impact on improving the coordination of resource and service orchestration in 6G systems. Thus, different AI/ML techniques assist a 6G system to realise the end-to-end orchestration by bringing together different enabling technology domains that realise the expected 6G KPIs [

2].

Among the various candidate AI/ML techniques that are considered [

3], the cognitive one is considered the most dominant, since it is capable of managing and synchronizing both the control and the data planes. The mental action or process of learning information and understanding through experience and the senses is characterized as cognition. An autonomous system is a technical application of cognition, since it is designed to perform the operational tasks of understanding by experiencing and sensing. Thus, a 6G Cognitive system becomes an intent-handling coordinating function that comprehends sophisticated and abstract intent semantics and calculates the ideal system goal state, and organizes activities to transition the system into this trustworthy state.

Ensuring the robustness of a cognitive system is of paramount importance, because it ensures not only the proper system operation, but also the reliable and safe operation of the network itself. As these systems increasingly rely on AI, they become susceptible to adversarial black-box attacks. Such attacks can undermine the integrity and reliability of the network, leading to potential vulnerabilities that can be exploited by malicious entities. Hence, it is crucial to design cognitive models that can withstand these adversarial threats, maintaining the smooth and safe coordination of 6G networks. Due to this, and in line with other similar works, the term cognitive coordinator is used in the rest of the paper to name the cognitive systems with coordinating responsibilities in 6G, such the deployment of auxiliary Network Functions (NFs), the application of policy rules and the selection of quality index parameters.

This paper addresses this pressing issue by assessing the robustness of different variations of BERT-based cognitive coordinators, against adversarial black-box attacks. A variety of adversarial black-box attacks are defined and executed in this study without direct access to the model weights. By employing diverse perturbation strategies, the robustness of the cognitive coordinator is rigorously tested. The evaluation metrics include score deviation, regression error, and perturbation coherence, with a particular focus on identifying class-specific vulnerabilities. This comprehensive assessment aims to provide insights into the resilience of the cognitive coordination in 6G systems.

As a representative case, the paradigm of trustworthiness provision is examined in this paper, as a popular task that a cognitive coordinator will be asked to manage in a 6G system. In this case, the user-intents are classified to five classes (trustworthiness dimensions), namely Security, Safety, Privacy, Resilience, and Reliability, based on which actions both at control and data plane will be mandated. Based on this mathematical

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section II provides some definitions of cognitive coordinators in 6G networks, and background of adversarial robustness in different domains. Then, Section III to Section Section IV are devoted to analyse the different cognitive coordinator models, adversarial attacks, and the evaluation process. Finally, main conclusions are drain in Section V.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Related Work in the Cognitive Coordinator Paradigm for Trustworthiness Provision

The mental action or process of learning information and understanding through experience and the senses is characterized as cognition. An autonomous system, such as the Cognitive Coordination component for 6G trustworthiness, is a technical application of cognition since it is designed to perform the operational tasks of understanding by experiencing and seeing.

In recent research initiatives for user-centric 6G networks [

4], the Cognitive Coordinator serves as the central mechanism for ensuring a specific property at the user or the system domain, such as user trust and system trustworthiness (

Figure 1). This paradigm facilitates a dynamic interaction loop where trust semantics initiated by users as intents are processed to ensure robust network operations aligned with user expectations and system integrity.

The starting point of the process is the user, whose trust requirements are pivotal for deciding the system’s response. The user communicates their trust expectations via an AI chatbot [

5], which then classifies their expectations into the five trust dimensions: Security, Safety, Privacy, Resilience, and Reliability. This is mapped output is defined as trust semantics.

Once the trust semantics are defined, they are passed to the Cognitive Coordinator, a central AI assisted component which includes a BERT-based regression model. This model plays a critical role in interpreting the trust semantics to a desired level of trustworthiness (LoTw) and then to the system’s transition actions related to the five trustworthiness dimensions.

The cognitive coordinator does more than just calculates scores; it dynamically decides on the best action to be taken to align network’s behavior with the calculated trustworthiness level. This might involve adjusting network configurations, enhancing security protocols or reallocating resources. This decision-process is responsible to take in account potential impacts of each action, ensuring that decisions deliver trust without compromising the efficiency or performance of the network.

Referred to as the Cognitive Coordinator model, this regression-based system ensures scalability and adaptability, delivering a robust mechanism for preliminary trustworthiness estimation. In this paper, we will evaluate the robustness of the Cognitive Coordinator model—the core computational element of the SAFE-6G framework—to validate its effectiveness and reliability across varying operational conditions.

Figure 1.

AI-assisted cognitive coordination of 6G trustworthiness.

Figure 1.

AI-assisted cognitive coordination of 6G trustworthiness.

2.2. Related work in Adversarial Robustness

Neural networks, despite their impressive performance across various domains, such as image and speech recognition, exhibit vulnerabilities that challenge their robustness and reliability. One notable vulnerability is their susceptibility to adversarial attacks. These attacks exploit the inherent discontinuities in neural networks, allowing small, imperceptible perturbations in input data to cause significant changes in output predictions. The phenomenon of adversarial attacks first started in the domain of image processing [

6], where it is demonstrated that by introducing imperceptible perturbations to images, neural networks could be easily misled into making mistakes in predictions with high confidence. This insight initiated extensive research into the robustness of neural networks and the methodologies for crafting adversarial examples. The visual aspect of these attacks was especially notable, as the altered images looked identical to the originals to human viewers.

Building on the foundational work in image-based attacks [

7,

8], researchers extended their exploration to audio processing. Audio adversarial attacks presented unique challenges due to the temporal and frequency-domain characteristics of audio signals. By introducing subtle perturbations to waveforms or spectral features, such as Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs), adversarial examples could effectively fool speaker recognition systems or speech-to-text models [

9]. These attacks demonstrated that vulnerabilities in neural networks were not limited to static inputs like images, but also extended to dynamic, time-dependent data.

More recently, adversarial research has shifted focus to the text domain [

10], which forms the core of this paper. Text-based adversarial attacks are particularly challenging due to the discrete and structured nature of language. Techniques such as synonym replacement, paraphrasing, and insertion of contextually plausible errors exploit the sensitivity of natural language processing models to slight variations in input, often leading to significant misclassifications [

11].

Adversarial attacks have expanded beyond particular data fields to encompass communication networks, including 5G systems and upcoming network technologies. As machine learning becomes integral to critical operations in these networks, such as spectrum sensing, network slicing, and resource allocation [

12], adversarial machine learning introduces new vulnerabilities. For instance, adversaries can exploit machine learning models used for spectrum sharing in 5G to disrupt communications or mislead the system into allocating resources inefficiently [

13]. These attacks take advantage of the inherent openness of wireless environments, where adversaries can observe and manipulate both data and control signals, creating a novel attack surface.

This evolving landscape of adversarial threats underscores the importance of developing robust defense mechanisms across all domains, from images and audio to text and communication networks. This paper builds on this foundation by investigating adversarial vulnerabilities in text-based applications within the communication networks domain, such as the cognitive coordinator that receives a text-based user-intent input and proposes strategies to mitigate such attacks.

3. Methodology of Assessing Robustness of Cognitive Coordinator

In this section, we describe the methodology employed to develop and evaluate the robustness of the Cognitive Coordinator model, along with the adversarial attack strategies applied. The core of the system is a BERT-based five-head regression model, designed to independently predict scores related to trustworthiness for five trust-related classes: Reliability, Privacy, Security, Resilience, and Safety.

3.1. Dataset Creation Principles

The dataset [

18] was created with the input of five domain experts, each specializing in one of the trust-related classes: Reliability, Privacy, Security, Resilience, and Safety. It consists of annotated phrases and sentences for each class with corresponding trustworthiness scores, which a user could ask for.

To enhance the dataset’s diversity and robustness, data augmentation techniques were applied. These augmentations aim to simulate real-world variations and improve the model’s generalization capabilities:

Each sample in the dataset was tokenized using the BERT tokenizer, with text sequences padded or truncated to a maximum length of 128 tokens. The data was then split into training (70%), validation (15%) and test (15%) sets to ensure balanced evaluation.

3.2. Model Architecture of Cognitive Coordinator

The architecture of our Cognitive Coordinator model builds upon the widely used BERT transformer framework. It uses a shared BERT encoder alongside five distinct regression heads, each designed to predict scores for specific trust-related dimensions. The key components of the architecture are as follows:

Bert Encoder: Pretrained BERT model serves as the shared feature extractor. It processes input text into a pooled output vector, the size of which corresponds to the hidden dimension of the BERT model.

Independent Regression Heads: These are fully connected layers, each tailored for a specific trust-related dimension: Reliability, Privacy, Security, Resilience, and Safety. This modular approach allows each head to specialize in its respective task.

Forward Pass: For every input, the BERT encoder generates a pooled representation, which is then passed to the appropriate regression head. This head computes the trustworthiness score for the corresponding dimension.

This architecture strikes a balance between shared learning across dimensions and specialized prediction, promoting both efficiency and accuracy.

3.3. Model Training

The model was fine-tuned using a systematic grid search to identify optimal hyperparameters, including the learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, and weight decay. Additionally, the grid search evaluated multiple transformer-based pre-trained models to benchmark their performance in trustworthiness quantification. The models considered in the search included:

BERT-Base-Uncased: A widely adopted general-purpose model with 12 layers and 110M parameters.

RoBERTa-Base: A robustly optimized variant of BERT, trained on a larger dataset with enhanced pre-training techniques.

ALBERT-Base (v2): A lightweight version of BERT that reduces model size via factorized embeddings and parameter sharing, while retaining high accuracy.

ELECTRA-Base: A model that trains with a discriminator-generator framework, offering faster pre-training and strong downstream performance.

These models were selected for their unique approaches in addressing the challenges of language modeling processing. Their selection helps to ensure that different aspects of natural language processing (NLP) challenges, such as computational efficiency, model size, and training methodology, are adequately explored and addressed.

The final grid search hyperparameter values that yielded the best performance were:

Learning rate = 2e-5

Batch size = 16

Epochs = 5

Weight decay: 0.01

The training utilized the AdamW optimizer paired with a linear learning rate scheduler. The mean squared error (MSE) was employed as the loss function, and early stopping based on validation loss was implemented to mitigate overfitting.

3.4. Adversarial Attack Setup

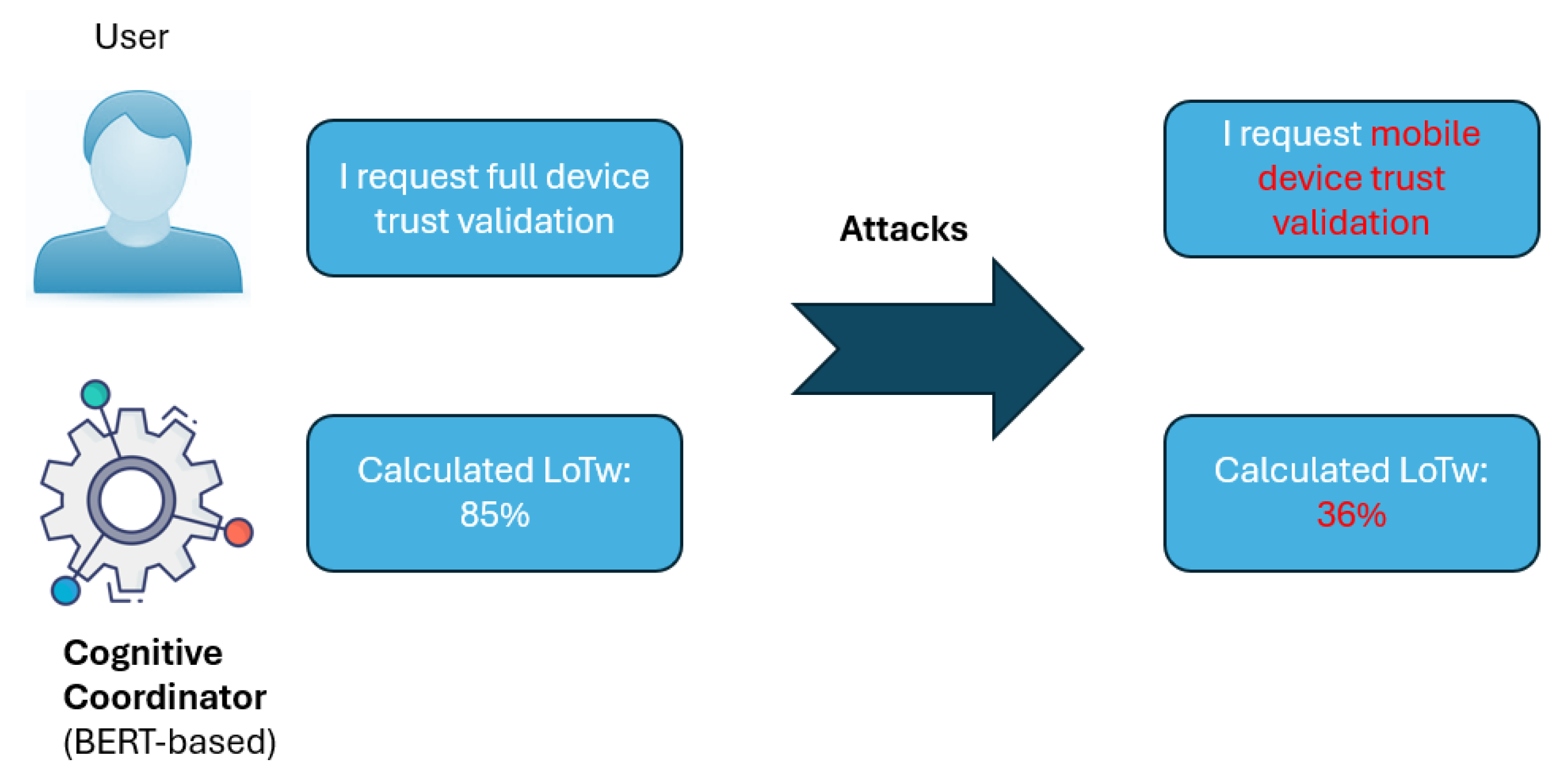

To assess the robustness of the model, three popular adversarial black-box attacks were implemented. These attacks targeted the text input, using perturbation strategies such as synonym replacement to manipulate semantics while retaining coherence (

Figure 2). The attacks aimed to evaluate the model’s sensitivity to input variations and its ability to maintain accurate trust assessments.

Figure 2.

Example of slightly input change but completly altered calculation result.

Figure 2.

Example of slightly input change but completly altered calculation result.

-

1)

The TextFooler attack

The TextFooler attack [

15] was employed as the primary adversarial strategy. This attack operates by identifying and perturbing the most salient words in the input, which have the highest impact on the model’s predictions. The attack framework includes the following steps:

● Salient Word Identification: Identifies the most impactful words by masking and analyzing the drop in model confidence.

● Synonym Replacement: Replaces identified words with synonyms using WordNet, ensuring grammatical consistency.

● Semantic and Perturbation Constraints: Maintains semantic similarity and minimizes the proportion of altered words to preserve input coherence.

-

2)

The BERT-Attack for textual entailment

To complement TextFooler, we employed the BERT-Attack for textual entailment (BAE) [

16], which utilizes a masked language model to replace or insert contextually appropriate words. This attack uses BERT’s ability to predict masked tokens in the text, allowing for more sophisticated perturbations. The framework for BAE includes the following steps:

● Salient Word Identification: Similar to TextFooler, BAE identifies salient words based on their contribution to the model’s predictions. Words are prioritized based on the drop in the model’s confidence when masked.

● Masked Word Replacement: Uses BERT’s masked language model to predict and replace words contextually.

● Semantic and Perturbation Constraints: Perturbations are constrained to maintain semantic coherence and minimize the number of modified tokens, ensuring that adversarial examples remain close to the original text in meaning.

-

3)

The Probability Weighted Word Saliency attack

To further evaluate the model’s robustness, we implemented the PWWS (Probability Weighted Word Saliency) attack [

17], which employs a saliency-based strategy to target the most impactful words in the input. PWWS utilizes a probability-weighted approach to rank word importance, making it particularly effective for identifying and replacing critical words in a sentence. The framework for PWWS includes the following steps:

● Saliency Score Computation: Assigns scores to words based on their impact on model predictions.

● Synonym Replacement: Focuses on high-saliency words, replacing them with contextually appropriate alternatives.

● Iterative Perturbation: The attack proceeds iteratively, replacing words until a significant deviation in the model’s prediction is achieved or all high-saliency words have been perturbed.

● Semantic and Perturbation Constraints: Like TextFooler and BAE, PWWS enforces constraints to preserve the original text’s meaning and ensure coherence. The number of modifications is minimized to create adversarial examples that remain realistic and meaningful.

PWWS differs from TextFooler by using probability-weighted saliency metrics, providing a more granular ranking of word importance. This approach often leads to fewer and more targeted perturbations, making it an effective complement to the other attacks.

In the next section, a comparison of the three different attacks is presented, while metrics, such as score deviation, regression error, and perturbation coherence are presented to quantify the impact of each adversarial attack.

4. Experimental Results of Cognitive Coordinator Model Under Adversarial Perturbations

This section evaluates the robustness of the Cognitive Coordinator model under adversarial perturbations, examining the three attacking strategies that have been explained in the previous section: TextFooler, BAE, and PWWS. The analysis employs key metrics—Score Deviation, Mean Squared Error (MSE), Perturbation Coherence, and Success Rate—to comprehensively assess the model’s vulnerabilities and resilience against these attacks. Together, these metrics demonstrate the model’s capacity to maintain reliable trustworthiness assessments under adversarial conditions.

More specifically, the following KPIs were used for quantifying the model robustness:

Score Deviation: Measures the average change in the predicted score between the original and adversarial examples, reflecting the model’s sensitivity to perturbations.

MSE: Quantifies the overall error introduced by adversarial attacks.

Perturbation Coherence: Evaluates the semantic similarity between the original and adversarial examples, ensuring that the meaning of the input remains intact despite perturbations.

Success Rate: Represents the percentage of adversarial examples that achieve a significant deviation in the model’s prediction, indicating the attack’s effectiveness.

The quantitative results for these metrics across all attacks are summarized in

Table 1.

The results reveal several key insights into the performance of the Cognitive Coordinator model under adversarial attacks. Among the models evaluated, RoBERTa-Base consistently demonstrated the highest Perturbation Coherence, with a maximum score of 0.985 for TextFooler, indicating its strong ability to preserve semantic meaning in adversarial conditions. However, it was also the most vulnerable to attacks, as evidenced by the high success rates across all attack strategies, which reflect the ease with which adversarial examples disrupted its predictions. This increased vulnerability was further supported by its higher MSE and Score Deviation values compared to other models.

ALBERT-Base, on the other hand, showed exceptional semantic resilience, achieving a Perturbation Coherence of 0.992 with TextFooler. Despite this strength, it exhibited reduced robustness against BAE and PWWS attacks, as seen in the higher Success Rates under these strategies. Bert-uncased emerged as the most balanced model, maintaining relatively low Score Deviations and MSE while preserving semantic coherence effectively, making it the most robust across different attack scenarios.

From an attack-specific perspective, TextFooler caused minimal semantic disruption while inducing significant score deviations, making it a suitable strategy for evaluating subtle vulnerabilities in the models. In contrast, BAE introduced more aggressive semantic changes, leading to a marked decrease in perturbation coherence. PWWS provided a balanced approach, combining moderate semantic preservation with effective adversarial impact, offering valuable insights into the practical resilience of the models.

Additionally,

Table 2 provides qualitative insights by showcasing examples of original and adversarial texts.

The results underscore several critical observations:

Model Selection and Use Cases: The choice of the transformer model depends on the operational context. For environments requiring high semantic coherence, RoBERTa-Base and ELECTRA-Base are not preferable. In resource-constrained scenarios, ALBERT-Base offers an efficient alternative.

Attack-specific Performance: TextFooler exhibited minimal semantic disruption but caused notable score deviations, making it suitable for subtle adversarial testing. BAE, while more aggressive, significantly impacted coherence. PWWS balanced perturbation impact and coherence, offering practical insights into adversarial robustness.

The next section discusses the implications of these results and outlines potential paths for improving the robustness of a cognitive coordinator model in a 6G network

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the various BERT-based cognitive coordinators in 6G networks, Bert-uncased emerges as the most balanced choice. It offers a robust defense against adversarial attacks while maintaining high levels of perturbation coherence, making it ideally suited for environments where maintaining semantic integrity is critical. On the other hand, RoBERTa-Base, despite its high sensitivity to adversarial manipulations, might be preferable in scenarios where higher vulnerability can be compensated by its superior performance in undisturbed conditions. Future research should focus on refining these models by integrating advanced adversarial defend techniques such as adversarial training. Additionally, testing these models in real world senarios will be crucial to further validate their effectiveness and adaptability in the dynamic network environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A. and H.K.; methodology, I.A, H.K. and V.R.; validation, I.A., V.R. and G.P.; formal analysis, I.A., H.K and G.M; investigation, I.A and S.G.; resources, H.K. and V.R.; data curation, I.A. and V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A. and H.K.; writing—review and editing, V.R., G.P., S.G. and G.M.; visualization, S.G.; supervision, H.K. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by i) the SAFE-6G project that has received funding from the Smart Networks and Services Joint Undertaking (SNS JU) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 101139031, ii) the 6G-VERSUS project that has received funding from the SNS JU under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 101192633.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 6G |

Sixth Generation |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BAE |

BERT-Attack for textual entailment |

| BERT |

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| KPIs |

Key Performance Indicators |

| LoTw |

Level of Trustworthiness |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MSE |

Mean Squared Error |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| PWWS |

Probability Weighted Word Saliency |

References

- G. Makropoulos, D. Fragkos, H. Koumaras, N. Alonistioti, A. Kaloxylos and F. Setaki, “Exploiting Core Openness as Native-AI Enabler for Optimised UAV Flight Path Selection,” in IEEE Conference on Standards for Communications and Networking (CSCN), 2023.

- D. Tsolkas, H. Koumaras, S. Charismiadis and A. Foteas, “Artificial intelligence in 5G and beyond networks,” in Applied Edge AI, Auerbach Publications, 2022, pp. 73-103.

- Christopoulou, Maria; Barmpounakis, Socratis; Koumaras, Harilaos; Kaloxylos, Alexandros, “Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning as key enablers for V2X communications: A comprehensive survey” in Vehicular Communications 39, 100569, vol. 39, p. 100569, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Gkatzios, H. Koumaras, D. Fragkos and V. Koumaras, “A Proof of Concept Implementation of an AI-assisted User-Centric 6G Network,” in Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EUCNC), 2024.

- N. Gkatzios, N. Vryonis, C. Fragkos, C. Sakkas, V. Mavrikakis, V. Koumaras, G. Makropoulos, D. Fragkos and H. Koumaras, “A chatbot assistant for optimizing the fault detection and diagnostics of industry 4.0 equipment in the 6g era,” in IEEE Conference on Standards for Communications and Networking (CSCN), 2023.

- C. Szegedy, W. Zaremba, I. Sutskever, J. Bruna, D. Erhan, I. Goodfellow and R. Fergus, “Intriguing properties of neural networks,” 2014.

- S. Y. Khamaiseh, D. Bagagem, A. Al-Alaj, M. Mancino and H. W. Alomari, “Adversarial Deep Learning: A Survey on Adversarial Attacks and Defense Mechanisms on Image Classification,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 102266-102291, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Zeng, C. Liu, Y.-S. Wang, W. Qiu, L. Xie, Y.-W. Tai, C.-K. Tang and A. L. Yuille, “Adversarial Attacks Beyond the Image Space,” in Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019.

- H. Tan, L. Wang, H. Zhang, J. Zhang, M. Shafiq and Z. Gu, “Adversarial Attack and Defense Strategies of Speaker Recognition Systems: A Survey,” Electronics, vol. 11, no. 14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. E. Zhang, Q. Z. Sheng, A. Alhazmi and C. Li, “Adversarial Attacks on Deep-learning Models in Natural Language Processing: A Survey.,” ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST), vol. 11, no. 3, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Han, Y. Zhang, W. Wang and B. Wang, “Text Adversarial Attacks and Defenses: Issues, Taxonomy, and Perspectives,” Security and Communication Networks, vol. 2022, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alexandropoulos, V. Rentoula, D. Fragkos, N. Gkatzios and H. Koumaras, “An AI-assisted User-Intent 6G System for Dynamic Throughput Provision,” in IEEE International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD 2024), Athens, Greece, 2024.

- Y. E. Sagduyu, T. Erpek and Y. Shi, Adversarial Machine Learning for 5G Communications Security, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2021.

- P. University, “WordNet,” [Online]. Available: https://wordnet.princeton.edu/.

- D. Jin, Z. Jin, J. T. Zhou and P. Szolovits, “Is {BERT} Really Robust? Natural Language Attack on Text Classification,” CoRR, vol. abs/1907.11932, 2019.

- S. Garg and G. Ramakrishnan, “BAE: BERT-based Adversarial Examples for Text Classification,” in Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2020.

- S. Ren, Y. Deng, K. He and W. Che, “Generating Natural Language Adversarial Examples through Probability Weighted Word Saliency,” in Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 2019.

- Dataset available online at https://github.com/FRONT-research-group/Cognitive_Coordinator/blob/main/dataset.csv.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).