3.1. Individual Analysis

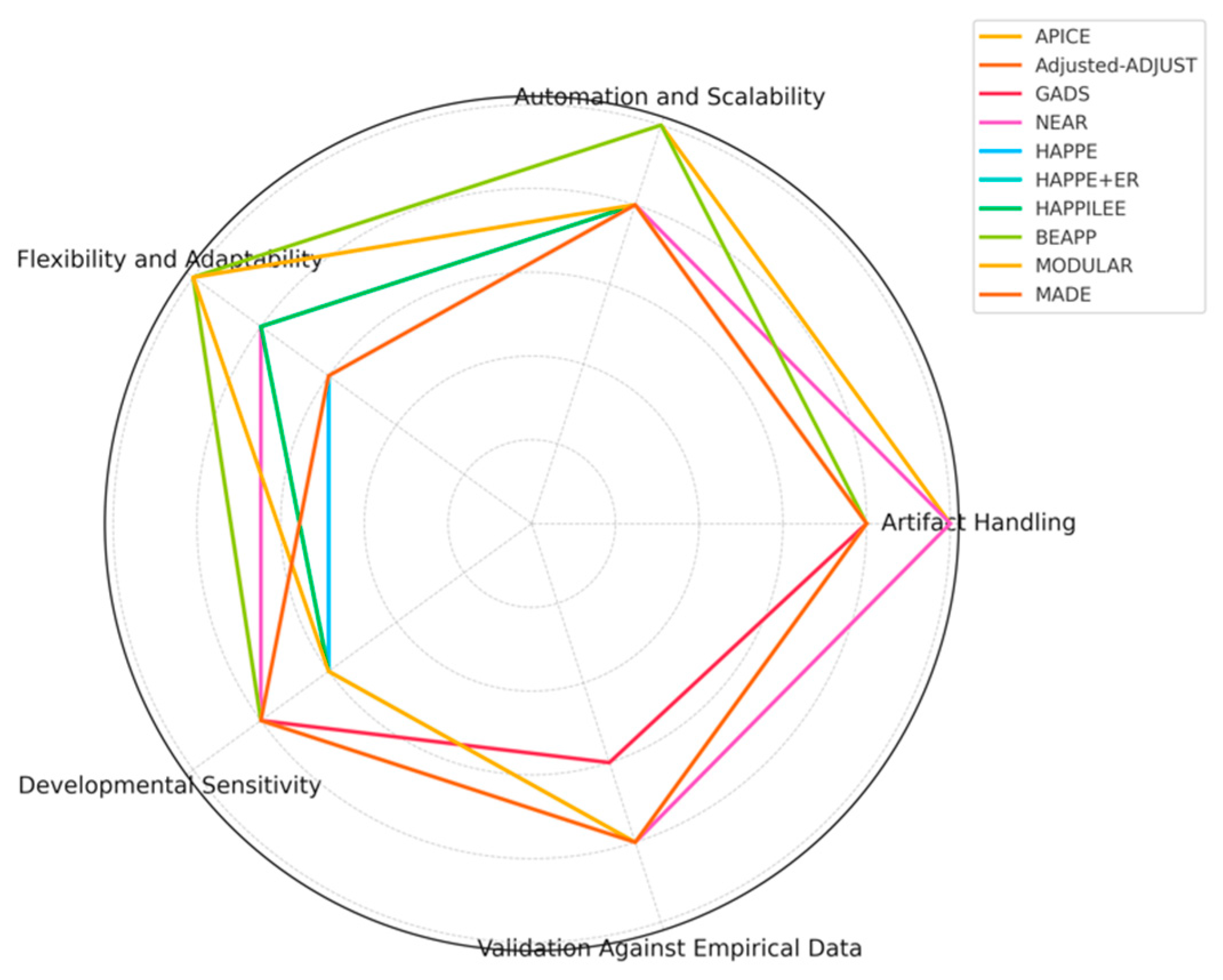

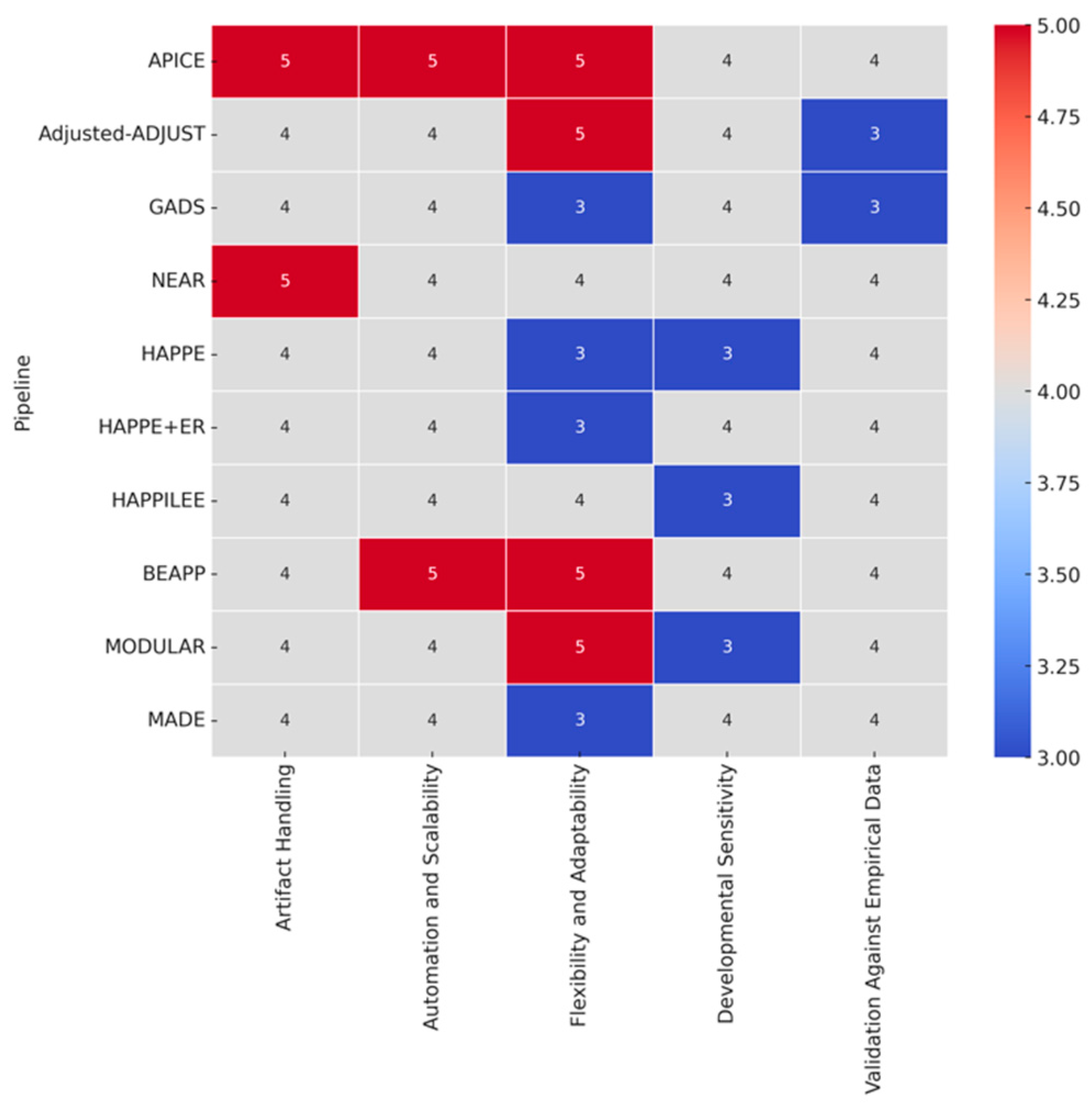

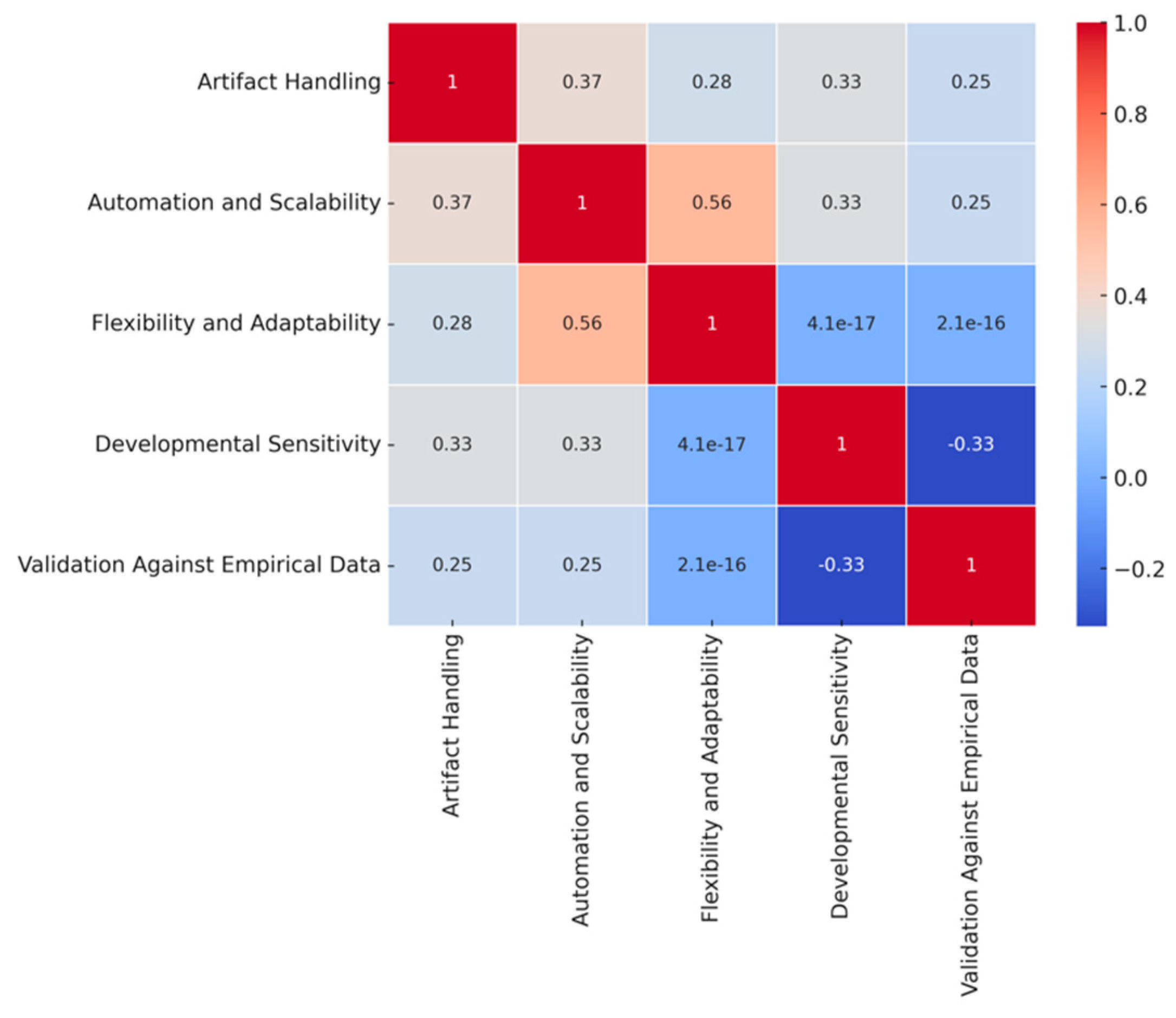

APICE: APICE demonstrates strong versatility in handling high artifact loads with iterative artifact detection and adaptive thresholds using multiple algorithms, such as DSS and ICA to target both physiological and non-physiological artifacts. The use of adaptive thresholds, which are based on the distribution of voltage values for each subject, allows APICE to detect and correct artifacts in a targeted manner, especially in high-artifact datasets like those collected from infants. This subject-level adaptability enhances the robustness of artifact detection across different populations without the need for main adjustments. The pipeline also performs artifact correction on continuous data, incorporating adaptive correction methods such as automated drift removal and targeted denoising, significantly enhancing data recovery before epoching. This approach is particularly effective in retaining signal integrity by reducing the impact of non-stereotyped artifacts over long recording periods. APICE excelled in artifact handling (index of 5), automation and scalability (index of 5), and flexibility (index of 5). However, although artifact handling received a descriptor index of 5, it is important to note that the effectiveness of ICA was limited in neonate data, which could temper the final choice of descriptor slightly when considering this specific subset. Developmental sensitivity received an index of 4, indicating room for improvement in specific optimizations for neonatal EEG – as mentioned above –, particularly due to the high inter-trial variability and developmental changes affecting artifact decomposition techniques like ICA and DSS. Finally, validation against empirical data received an index of 4, reflecting its strong but not exhaustive validation efforts. This descriptor index takes into account specific limitations, such as the marginal effect of ICA or DSS improvements across the different datasets evaluate in the literature.

Adjusted-ADJUST: The Adjusted-ADJUST pipeline is notable for enhancing artifact detection using modified ICA and additional algorithms tailored specifically to infant EEG data collected with geodesic nets. It employs modifications aimed at handling the unique properties of infant data, such as adjustments for ocular artifact detection and modifications for blink and horizontal eye movement detection. Specifically, the ocular artifact detection algorithms were adjusted by changing the spatial feature parameters and removing the temporal measure for more robustness against noise, which is often higher in infant datasets. These features improve artifact classification for developmental EEG and make the pipeline more robust against increased noise levels. The authors of the algorithm compared the adjusted pipeline to the original-ADJUST and ICLabel algorithms in terms of three performance measures: classification agreement with expert coders, number of trials retained after artifact removal, and reliability of the EEG signal after preprocessing. Adjusted-ADJUST demonstrated higher classification agreement scores with expert coders compared to the original-ADJUST and ICLabel (i.e., the adjusted-ADJUST algorithm achieved an agreement score of 80.78% compared to 57.83% for original-ADJUST and 73.46% for ICLabel). Based on these characteristics, Adjusted-ADJUST received in my analysis an index of 4 for artifact handling due to its reliance on manual parameter adjustments, which however introduces variability and reduces full automation effectiveness. Flexibility and adaptability were indexed at 5, thanks to the pipeline's customization options and compatibility with external EEG tools like EEGLAB. The pipeline also allows users to modify parameters such as z-score thresholds for blink detection, enabling greater adaptability for different datasets. Developmental sensitivity was indexed at 4 when compared to other pipelines, as it includes specific adjustments for ocular artifacts, with the need of further refinements and validations to handle the physiological and behavioral variabilities across all developmental stages effectively, such as the differences in blink rates, skull density, and movement artifacts. Finally, validation against empirical data received an index of 3, reflecting the need for more extensive empirical validation across multiple diverse infant populations, including different developmental stages, acquisition setups, and experimental paradigms. Compared to other pipelines, such as APICE, NEAR, and HAPPE, which have been validated across a variety of datasets and paradigms, Adjusted-ADJUST lacks validation across multiple setups and does not seem to produce comprehensive quality metrics at each preprocessing stage.

GADS: The GADS pipeline utilizes a two-stage SVM-based approach to distinguish between major and minor artifacts in neonatal EEG, achieving high accuracy in artifact detection, especially for major artifacts with a median AUC of 1.00 (IQR: 0.95-1.00). The first stage of the SVM-based approach specifically employs 14 different features extracted from EEG epochs, including mean amplitude, frequency-band energies, Hurst exponent, and other measures, across different time scales (2s, 4s, 16s, and 32s epochs) to classify the artifacts effectively. In this approach, detection is relatively straightforward for major artifacts, due to significant differences in amplitude and frequency between background EEG and artifact, whereas the detection of minor artifacts is more challenging. The median AUC for minor artifacts presented to be 0.89 (IQR: 0.83-0.95), indicating substantial but variable accuracy. However, GADS is less consistent in detecting subtle low-amplitude artifacts, often failing to identify minor fluctuations that could still significantly impact the overall signal quality. For this quite comprehensive yet focused approach, GADS received an index of 4 for artifact handling, while its reliance on pre-set features, which are not optimized for different neonatal conditions, limits the pipeline's generalizability across diverse datasets, achieving an index of 3 for flexibility and adaptability. The pipeline received an index of 4 for automation and scalability, as it effectively automates artifact detection but lacks the flexibility of fully modular pipelines like APICE or BEAPP. Unlike APICE, which offers adaptive thresholds and multiple algorithms for artifact detection, or BEAPP, which provides extensive batch processing capabilities across diverse acquisition systems, GADS relies on a more fixed approach, limiting its adaptability across different datasets. Developmental sensitivity also received an index of 4, as it addresses neonatal-specific EEG characteristics but lacks specific adaptations for older children, while the validation against empirical data received an index of 3 as it was performed specifically in a NICU setting, using leave-one-out cross-validation on a cohort of 51 neonates, which limits broader applicability.

NEAR: NEAR takes an innovative approach by employing LOF for bad channel detection and ASR for transient artifact removal, specifically calibrated for newborn EEG. LOF is a density-based algorithm that identifies bad channels by comparing the local density of data points to those of its neighbors, which is effective for detecting channels with atypical noise levels. To achieve optimal results, LOF is calibrated using the F1 Score metric (a measure that combines precision and recall to provide a balanced evaluation of classification performance), allowing NEAR to effectively distinguish between good and bad channels, even in challenging newborn datasets. ASR, on the other hand, is used to remove transient, high-amplitude artifacts, supporting two ASR processing modes: Correction (ASRC) and Removal (ASRR). The ASRR mode is generally preferred for newborn EEG, as it has been found to remove artifacts more effectively while preserving the underlying neural activity (e.g., ANOVA results: ASRR showed significant effects (F(1,13) = 5.13, P = 0.041) compared to ASRC (F(1,13) = 1.68, P = 0.22); power spectrum peak recovery was higher in ASRR; ERP effects were clearer with ASRR). In this context, NEAR excelled in artifact handling (index of 5) due to its novel use of LOF for channel detection and calibrated ASR for artifact removal. Developmental sensitivity was indexed at 4, reflecting its precise targeting of newborn EEG and tailored parameters for neonatal characteristics, although not incorporating parameters for prematurity, while automation and scalability were indexed at 4, featuring batch processing and adaptive calibration, though the requirement for manual adjustments for data for different experimental setups or different artifact profiles limited scalability. For this latter reason, flexibility and adaptability also received an index of 4. Finally, validation against empirical data received an index of 4, with successful validation across multiple neonatal datasets using metrics like the F1 Score. I did not assign an index of 5 in this case due to limitations such as the lack of validation across all developmental stages and other experimental contexts, which would be necessary to establish broader generalizability.

HAPPE: The Harvard Automated Processing Pipeline for EEG (HAPPE) utilizes Wavelet-enhanced Independent Component Analysis (W-ICA) and the Multiple Artifact Rejection Algorithm (MARA) to effectively separate artifacts and perform automated component rejection. Due to these advanced techniques that effectively reduce artifacts while preserving the EEG signal it achieved an index of 4 for artifact handling. However, it did not receive the highest index for this criterion because of challenges in handling certain complex artifacts and limitations in achieving full automation, necessitating manual intervention at times. Speaking about automation and scalability, these were indexed at 4, as the reliance on MATLAB limits scalability to broader environments. By the same token, although HAPPE includes batch processing capabilities, which enhances scalability for large datasets, the same dependency on MATLAB may pose challenges for integrating with other software platforms commonly used in research environments, justifying once more the assigned index for this specific criterion. In the same line of reasoning, flexibility and adaptability were indexed at 3, as customization options are limited due to the pipeline's primary optimization for MATLAB, restricting adaptation to different experimental setups, electrode configurations, or cross-platform use. However, the integration with BEAPP partially addresses these limitations by providing a user-friendly interface that supports diverse channel layouts and enhances flexibility in large-scale studies. Developmental sensitivity was also indexed at 3, indicating that more focused calibration for neonatal EEG characteristics is needed. While HAPPE includes some developmental adjustments, it lacks the granularity and optimizations essential for neonatal EEG, especially compared to specialized pipelines like NEAR, which are calibrated for neonatal-specific data. Finally, validation against empirical data received an index of 4, supported by extensive testing on a large developmental dataset, including EEG data from infants and young children, demonstrating its effectiveness in high-artifact conditions. However, further validation across multiple contexts, such as different developmental stages and experimental paradigms, would confirm its robustness and generalizability for diverse developmental conditions.

HAPPE+ER: HAPPE+ER is an extension of HAPPE, specifically optimized for event-related potential (ERP) analyses. As an extension, it inherits both the strengths and limitations of the original HAPPE framework. For this reason, HAPPE+ER showcased slightly better capabilities from HAPPE, with indices of 4 for artifact handling, automation and scalability, and validation against empirical data. Flexibility and adaptability were indexed with a 3, while developmental sensitivity with a 4. In this extension of HAPPE, the improvements for ERP analyses include the addition of automated event marker detection, enhanced epoch segmentation, and wavelet-based denoising, which collectively enhance artifact handling and data quality especially in ERP settings. Additionally, developmental sensitivity was improved by incorporating event-specific preprocessing techniques that better account for the characteristics of ERP signals in infants, though optimizations for other developmental stages are still lacking. Despite these enhancements, limitations in customization and broader validation persist as in the HAPPE pipeline.

HAPPILEE: HAPPILEE is also designed as an extension of the HAPPE pipeline, but for low-density EEG setups. This pipeline extension was indexed at a high level in artifact handling (index of 4) due to the effective artifact correction methods tailored for low-density configurations, while automation, thanks to several automated processing steps that simplify data handling, was also indexed with a 4; though some complex artifacts still require manual intervention, and full automation across different research contexts remains a challenge. Flexibility and adaptability were indexed with a 4, reflecting the pipeline’s focus on low-density configurations, which nevertheless limits broader applicability. Developmental sensitivity was indexed with a 3, as it lacks broader calibration for different developmental stages. The pipeline's current methods for bad channel detection, while functional for low-density setups, are not fully optimized for varying channel densities and often fail to account for the unique characteristics of neonatal and infant EEG, leading to less effective identification of bad channels – after all this is a specialized version and should be treated as such. Moreover, the thresholding system for segment rejection is not adequately adaptive, making it less effective for data with high artifact variability typically seen in infant populations. This results in either over-rejection or retention of noisy data, which impacts data quality and limits the pipeline's utility in diverse developmental research settings when also considered along its low-density set-up inclination. Finally, validation against empirical data was indexed at 4, reflecting robust validation efforts with multiple neonatal datasets, although the focus on specific experimental contexts limits generalizability as in the previous cases of HAPPE+ER and HAPPE.

BEAPP: BEAPP integrates several freely available preprocessing tools, such as EEGLAB, FieldTrip, and the PREP pipeline, into a highly flexible framework designed to support multisite and longitudinal EEG studies. BEAPP stands out for its ability to seamlessly handle data from multiple acquisition setups and its emphasis on automation, making it particularly suited for large-scale, multi-site studies requiring consistent and reproducible workflows. It provides extensive capabilities for artifact minimization, such as muscle artifacts, eye movement artifacts, and line noise, and re-referencing across various EEG systems, all of which are facilitated by an accessible graphical user interface (GUI). The GUI makes it particularly accessible for non-programmers, enabling a broader range of users to effectively manage preprocessing steps by offering intuitive parameter setting, visual feedback on processing progress, and easy-to-navigate options for customizing analysis workflows. BEAPP includes advanced artifact removal tools, such as automated line noise removal and ICA, which help to maintain data quality even in large and heterogeneous datasets. For all this, BEAPP was indexed at 4 for artifact handling due to its use of sophisticated tools like Cleanline, ICA, and MARA, which effectively handle common EEG artifacts. However, manual adjustments for filtering parameters, such as determining appropriate cutoff frequencies or adjusting notch filter settings, may require user expertise to optimize data quality and avoid unintended distortions, which can be challenging without a solid understanding of signal processing. It goes without saying that automation and scalability were indexed with a 5, as BEAPP supports extensive batch processing – all within the user-friendly GUI –, while flexibility and adaptability also received an index of 5, owing to its modular framework, which allows seamless integration with multiple external tools, making it highly customizable for different EEG systems and datasets. Developmental sensitivity received an index of 4, as BEAPP incorporates features from pipelines like HAPPE, which provides effective solutions for handling infant EEG, such as targeted artifact rejection tailored to high-artifact infant data and enhanced preprocessing steps to accommodate shorter attention spans and high variability in data quality. However, it inherits certain limitations from these pipelines, too, such as the need for more extensive validation across different brain maturation groups and experimental contexts. Finally, validation against empirical data received an index of 4, reflecting successful validation efforts compared to other established pipelines and strong data retention rates. So far, BEAPP has been validated on datasets involving pediatric EEG and typical adult EEG in controlled lab environments, such as data from the Infant Sibling Project (ISP; for the pediatric EEG cohort), which included different sampling rates and acquisition setups like 64-channel and 128-channel Geodesic Sensor Nets. However, further validation on more diverse datasets, such as clinical populations, multi-site international datasets, and datasets with different EEG acquisition systems, remains pending and would definitely help towards its generalizability.

MODULAR: The Modular EEG preprocessing pipeline provides extensive customization options through the selection of different ICA methods, such as SOBI and Extended Infomax, and re-referencing strategies like CAR, REST, and RESIT. SOBI is known for its effectiveness in separating sources based on second-order statistics, while Extended Infomax is an advanced version of the Infomax algorithm that can handle both sub-Gaussian and super-Gaussian sources. CAR helps in reducing common noise by averaging signals from all electrodes, REST aims to reconstruct the signal as if referenced to a neutral point, and RESIT provides a refined approach to minimize residual artifacts through interpolation. Because of these collective characteristics, Modular received a high index of 5 for flexibility and adaptability, reflecting its extensive customization options. On the other hand, artifact handling was indexed with a 4, as there is some inconsistency in managing subtle or low-amplitude artifacts, such as eye blinks or muscle twitches, which often require manual refinement and adjustment to ensure data quality across different experimental contexts. Automation and scalability were also indexed with a 4 due to the inclusion of batch processing, although the need for manual selection of artifact components and re-referencing methods somewhat diminishes the ability towards full automation. For instance, manual intervention is often required to accurately identify and reject noisy components that automated methods may misclassify, as evidenced in the relevant literature (Coelli et al., 2024), which found that applying ICA led to a higher percentage of components classified as 'Other' due to misclassifications, requiring human correction to improve the quality of signal processing. Developmental sensitivity received a 3 as Modular does not incorporate age-specific adaptations for developmental EEG datasets, such as specialized filtering techniques or reference options tailored to the unique characteristics of differentiating infant EEG signals. Finally, validation against empirical data received an index of 4, based on quantitative measures such as Mutual Information Reduction (MIR) and empirical tests across adult datasets. MIR provides insights into the independence of signal components, but as suggested by the creators and authors, it may be beneficial to also consider other validation metrics like Dipolarity or Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) for a more comprehensive assessment of signal quality and physiological plausibility. Additionally, broader validation in developmental populations is particularly important, as already mentioned a few times, due to the unique neurophysiological characteristics and variability in EEG signals at different stages of development.

MADE: MADE is specifically tailored for developmental EEG, utilizing ASR and ICA to address the high variability and artifact prevalence typical in infant EEG. It also incorporates feature-based component selection and the FASTER EEGLAB plugin for bad channel removal and interpolation, which ensures that critical developmental signals are retained, thereby enhancing its applicability for understanding early brain maturation. Compared to other commonly used methods, such as traditional threshold-based artifact rejection, MADE's feature-based component selection offers a more targeted and efficient approach, minimizing data loss while retaining essential neural signals. MADE employs an automatic classification of independent components (ICs) using the adjusted-ADJUST method, enhancing artifact rejection by avoiding subjective biases and targeting features that are better suited for developmental data, and ensuring more effective artifact removal and better preservation of valuable data. However, the pipeline has several limitations, including its reliance on MATLAB, which restricts accessibility to users without appropriate software licenses and training. The computational demands of ICA, especially for high-density EEG, can also be a bottleneck, requiring significant processing time and hardware resources. Additionally, the fixed parameters used for artifact rejection may not be optimal for all datasets, reducing the flexibility needed to adapt to different recording conditions or developmental age groups, which could limit its broader applicability across varied research contexts. For these characteristics, MADE received specific indices for each criterion as follows: Artifact handling was indexed with a 4 due to its effective use of ICA and automated artifact correction techniques to address high artifact contamination. Automation and scalability were also assigned a 4, with MADE being fully automated, incorporating batch processing, and supporting data from various hardware systems, though computational demands and reliance on MATLAB limit accessibility. Flexibility and adaptability were indexed with a 3, as it is heavily focused on low-density EEG setups, while the reliance on the EEGLAB environment also means that users need familiarity with this specific software, which further limits its broader applicability without significant modification. Developmental sensitivity was assigned a 4, with MADE effectively addressing challenges unique to infant EEG, such as high artifact levels and shorter recording lengths, though further customization for different developmental stages could improve its utility. Finally, validation against empirical data was indexed at 4 based on successful validation with large developmental datasets, including EEG recordings from infants (12 months old), young children (3-6 years old), and late adolescents (16 years old). The infant data was collected using a 128-channel EGI system, the childhood data with a 64-channel BioSemi Active 2 system, and the late adolescent data with a 64-channel EGI system, demonstrating effective artifact removal and high data retention. The validation involved comparing the percentage of retained trials and the quality of processed EEG signals across different preprocessing pipelines, highlighting MADE's superior performance in retaining clean data while minimizing artifact influence. However, the specific index of 4 also reflects certain limitations in the validation process, including for example the challenges in maintaining consistency in artifact rejection across datasets with varying noise profiles. Additionally, the empirical validation lacked a comprehensive assessment of inter-rater reliability in identifying artifacts, which could affect consistency in real-world applications.