Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Pathophysiology of Cardiac Troponin Release from Injured Myocardium

| cTn baseline ≤URL |

cTn baseline >URL | Clinical criteria (≥1 needed) | |

| UDMI Type 4a AMI [3] | >5x URL plus ECG or imaging criteria | Increase >20% + >5x URL plus ECG or imaging criteria | New signs of myocardial ischemia as evidenced by ECG, imaging, or coronary flow-limiting complications |

| SCAI clinically relevant AMI [65] | ≥70x URL or ≥35x URL plus ECG criteria | ≥70x URL or ≥35x URL plus ECG criteria | New Q waves in ≥ 2 contiguous leads, New persistent LBBB |

| ARC-2 peri-procedural AMI [66] | ≥35x URL plus ECG or imaging criteria |

≥35x URL plus ECG or imaging criteria |

New Q waves or equivalents, evidence in imaging, coronary flow-limiting complications |

| Intact and truncated cTnTIC complexes | Free partially truncated (HMM) cTnT | Intact and truncated cTnIC complexes | Free heavily truncated (LMM) cTnT | |

| AMI | x | x# | x* | x |

| ESRD | x | x | ||

| Post heavy endurance exercise (e.g. marathon) | x | x |

3. Clearance of cTnI and cTnT from the Circulation in Humans

4. Circulating Forms of Cardiac Troponins in Human Blood

5. Are There Clinically Relevant Differences Between cTnI and cTnT?

6. Summary and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thygesen, K.; Mair, J.; Katus, H.; Plebani, M.; Venge, P.; Collinson, P.; et al. Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of the ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. Recommendations for the use of cardiac troponin measurement in acute cardiac care. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 2197–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thygesen, K.; Mair, J.; Giannitsis, E.; Mueller, Ch.; Lindahl, B.; Blankenberg, S.; et al. the Study group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of the ESC Working group on Acute Cardiac Care. How to use high-sensitivity cardiac troponins in acute cardiac care. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2252–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.B.; Morrow, D.A.; et al. Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 237–269. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Cullen, L.; Giannitsis, E.; Hammarsten, O.; Huber, K.; Jaffe, A.; et al. Application of the fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction in clinical practice. Biomarkers 2020, 25, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.; Baron, T.; Albertucci, M.; Prati, F. Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Eurointervention 2021, 17, e875–e887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Lindahl, B.; Müller, Ch.; Giannitsis, E.; Huber, K.; Möckel, M.; et al. What to do when you question cardiac troponin values. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care.

- Mair, J.; Jaffe, A.; Lindahl, B.; Mills, N.; Möckel, M.; Cullen, L.; et al. The clinical approach to diagnosing peri-procedural myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary interventions according to the fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction - from the study group on biomarkers of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Association for Acute CardioVascular Care (ACVC). Biomarkers 2022, 27, 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Giannitsis, E.; Mills, N.L.; Mueller, C. Study Group on Biomarkers of the European Society of Cardiology Association for Acute CardioVascular Care. How to deal with unexpected cardiac troponin results. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care, 11.

- Mair, J.; Hammarsten, O. Potential analytical interferences in cardiac troponin immunoassays. J. Lab. Precis. Med.

- Parmacek, M.S.; Solaro, R.J. Biology of troponin complex in cardiac myocytes. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2004, 47, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrukha, I.A. Human cardiac troponin complex. Structure and functions. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2013, 73, 1447–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Jin, J.P. Troponin T isoforms and posttranscriptional modifications: evolution, regulation and function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 505, 144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Yamashita, A.; Maeda, K.; Maeda, Y. Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca2+ saturated form. Nature 2003, 424, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, T.; Kedes, L.; Gahlmann, R. Cloning, structural analysis, and expression of the human slow twitch skeletal muscle/cardiac troponin C gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 21247–21253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallins, W.J.; Brand, N.J.; Dabhade, N.; Butler-Browne, G.; Yacoub, M.H.; Barton, P.J. Molecular cloning of human cardiac troponin I using polymerase chain reaction. FEBS Lett. 1990, 270, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesnard, L.; Samson, F.; Espinasse, I.; Durand, J.; Neveux, J.Y.; Mercadier, J.J. Molecular cloning and developmental expression of human cardiac troponin T. FEBS Lett. 1993, 328, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.A.W; Greig, A.; Mark, T.M.; Malouf, N.N.; Oakeley, A.E.; Ungerleider, R.M.; et al. Molecular basis of human cardiac troponin T isoforms expressed in developing, adult, anf failing heart. Circ. Res. 1995, 76, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.F. Turnover of cardiac troponin subunits. Kinetic evidence for a precursor pool of troponin I. J. Biol. Chem.

- Remppis, A.; Scheffold, T.; Greten, J.; Haas, M.; Greten, T.; Kübler, W.; et al. Intracellular compartmentation of troponin T: release kinetics after global ischemia and calcium paradox in the isolated perfused rat heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol.

- Bleier, J.; Vorderwinkler, K.P.; Falkensammer, J.; Mair, P.; Dapunt, O.; Puschendorf, B.; et al. Different intracellular compartmentations of cardiac troponins and myosin heavy chains: a causal connenction to their different early release after myocardial damage. Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 1912–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisa, F.; De Tullio, R.; Salamino, F.; Barbato, R.; Melloni, E.; Siliprandi, N.; et al. Specific degradation of troponin T and I by µ-calpain and its modulation by substrate phosphorylation. Biochem. J. 1995, 308, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communal, C.; Sumandea, M.; de Tombe, P.; Narula, J.; Solaro, R.J.; Hajjar, R.J. Functional consequences of caspase activation in cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 2002 99, 6252–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Garrido, A.; Biesiadecki, B.J.; Sakhi, H.E.; Shaifta, Y.; G Dos Remiedios, C.; Ayaz-Guner, S.; et al. Monophosphorylation of cardiac troponin-I at Ser-23/24 is sufficient to regulate cardiac myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity and calpain-induced proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 8588–8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Qi, X.Y.; Dijkhuis, A.J.; Chartier, D.; Nattel, S.; Henning, R.H.; et al. Calpain mediates cardiac troponin degradation and contractile dysfunction in atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2008, 45, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starnberg, K.; Jeppsson, A.; Lindahl, B.; Hammarsten, O. Revision of the troponin T release mechanism from damaged human myocardium. Clin. Chem. 2014, 60, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Morandell, D.; Genser, N.; Lechleitner, P.; Dienstl, F.; Puschendorf, B. Equivalent early sensitivitties of myoglobin, creatine kinase MB mass, creatine kinase isoform ratios and cardiac troponin I and T after acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chem. 1995, 41, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Thome-Kromer, B.; Wagner, I.; Lechleitner, P.; Dienstl, F.; Puschendorf, B.; et al. Concentration time courses of troponin and myosin subunits after acute myocardial infarction. Coron. Artery Dis. 1994, 5, 865–872. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, H.M.; Schwartz, P.; Spahr, R.; Hütter, J.F.; Spieckermann, G. Early enzyme release from myocardial cells is not due to irreversible cell damage. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1984, 16, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump, B.F.; Berezesky, I.K. The role of cytosolic Ca2+ in cell injury, necrosis and apoptosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1992, 2, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.N.; Cheng, C.C.; Lee, Y. F; Chen, J-S.; Ho, S-P.; et al. Early activation of myocardial matrix metalloproteinases and degradation of cardiac troponin I after experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 179, e41–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, E.M.; Sumandea, M.P.; Kobayashi, T.; Nili, M.; Martin, A.F.; Homsher, E.; et al. Phosphorylation or Glutamic Acid Substitution at Protein Kinase C Sites on Cardiac Troponin I Differentially Depress Myofilament Tension and Shortening Velocity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11265–11272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumandea, M.P.; Vahebi, S.; Sumandea, C.A.; Garcia-Cazarin,M. L.; Staidle, J.; Homsher, E. Impact of Cardiac Troponin T N-Terminal Deletion and Phosphorylation on Myofilament Function. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 7722–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, Z.; Zahran, S.; Liu, P.B.; Reiz, B.; Chan, B.Y.H.; Roczkowsky, A.; et al. Structure and proteolytic susceptibility of the inhibitory C-terminal tail of cardiac troponin I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrukha, I.A.; Kogan, A.E.; Vylegzhanina, A.V.; Serebryakova, M.V.; Koshkina, E.V.; Bereznikova, A.V.; et al. Thrombin-mediated degradation of human cardiac troponin T. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Clinical Applications of Cardiac Biomarkers (C-CB). High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I and T Assay Analytical Characteristics Designated by Manufacturer v062024. High-Sensitivity-Cardiac-Troponin-I-and-T-Assay-Analytical-Characteristics-Designated-By-Manufacturer-v062024.pdf (assessed on th 2025). 25 April.

- Asayama, J.; Yamahara, Y. , Ohta; B., Miyazaki; H., Tatsumi; T., Matsumoto; T., et al. Release kinetics of cardiac troponin T in coronary effluent from isolated rat hearts during hypoxia and reoxygenation. Bas. Res. Cardiol., 1992, 87, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinchant, J.P.; Polge, A.; Robert, E.; Sabbah, N.; Fabbo-Paray, P.; Poirey, S.; et al. Time-course of cardiac troponin I release from isolated perfused rat hearts during hypoxia/reoxygenation and ischemia/reperfusion, Clin. Chim. Acta 1999, 283, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzler, B.; Hammerer-Lercher, A.; Jehle, J.; Dietrich, H.; Pachinger, O.; Xu, Q.; et al. Plasma cardiac troponin T closely correlates with infarct size in a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2002, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, M.; Hohnloser, S.H.; Köster, W.; Prinz, M.; Kasper, W.; Just, H. Analysis of creatine kinase; CK-MB, myoglobin, and troponin T time-activity curves for early assessment of coronary artery reperfusion after intravenous thrombolysis. Circulation 1993, 87, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katus, H.A.; Remppis, A.; Scheffold, T.; Diederich, K.W.; Kuebler, W. Intracellular compartmentation of cardiac troponin T and its release kinetics in patients with reperfused and nonreperfused myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1991, 67, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.T; McNeil, P.L. Membrane Repair: Mechanisms and Pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 1205–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, M.H.; Michielsen, E.C.; Atsma, D.E.; Schalij, M.J.; van der Valk, E.J.; Bax, W.H.; et al. Release kinetics of intact and degraded troponin I and T after irreversible cell damage. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2008, 85, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, H.M.; Schwartz, P.; Hutter, J.F.; Spieckermann, P.G. Energy metabolism and enzyme release of cultured adult rat heart muscle cells during anoxia, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1984, 16, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Saffitz, J.E.; Mealman, T.L.; Grace, A.M.; Roberts, R. Reversible myocardial ischemic injury is not associated with increased creatine kinase activity in plasma. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersten, O.; Mair, J.; Möckel, M.; Lindahl, B.; Jaffe, A.S. Possible mechanisms behind cardiac troponin elevations. Biomarkers 2018, 23, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, B.R.; Young, R.F.; Shen, X.; Suzuki, G.; Qu, J. Malhotra S; Canty JM; Jr. Brief Myocardial Ischemia Produces Cardiac Troponin I Release and Focal Myocyte Apoptosis in the Absence of Pathological Infarction in Swine. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Basic Transl. Sci. 2017, 2, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, B.R.; Suzuki, G.; Young, R.F.; Iyer, V; Canty, J. M.Jr. Troponin Release and Reversible Left Ventricular Dysfunction After Transient Pressure Overload. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2906–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streng, A.S.; Jacobs, L.H.; Schwenk, R.W.; Cardinaels, E.P.; Meex, S.J.; Glatz, J.F.; et al. Cardiac troponin in ischemic cardiomyocytes: intracellular decrease before onset of cell death. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2014, 96, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassenstein, K.; Breuckmann, F.; Bucher, C.; Kaiser, K.; Konzora, T.; Schäfer, L.; et al. How much myocardial damage is necessary to enable detection of focal gadolinium enhancement at cardiac MR imaging? Radiology 2008, 249, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatzki, J.; Giannitsis, E.; Hegenbarth, A.; Mueller-Hennessen, M.; André, F.; Frey, N.; et al. Absence of visible infarction on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging despite the established diagnosis of myocardial infarction by 4th Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2024, 13, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjot, J.; Kaier, T.E.; Martin, E.D.; Reji, S.S.; Copeland, O.; Iqbal, M.; et al. Quantifying the Release of Biomarkers of Myocardial Necrosis from Cardiac Myocytes and Intact Myocardium. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, B.; Auckland, M.L.; Cummins, P. Cardiac-specific troponin-I radioimmunoassay in the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 1987, 113, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitsis, E.; Kurz, K.; Hallermayer, K.; Jarausch, J.; Jaffe, A.S.; Katus, H.A. Analytical validation of a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Clin Chem 2010, 56, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krintus, M.; Kozinski, M.; Boudry, P.; Capell, N.E.; Köller, U.; Lackner, K.; et al. European multicenter analytical evaluation of the Abbott Architect STAT high sensitivity troponin I assay. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2014, 52, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Portbury, A.L.; Willis, M.S.; Patterson, C. Tearin’ Up My Heart: Proteolysis in the Cardiac Sarcomere. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 9929–9934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, AF. Turnover of cardiac troponin subunits. Kinetic evidence for a precursor pool of troponin I. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Morrow, D.A.; de Lermos, J.A.; Jarolim, P.; Braunwald, E. Detection of acute changes in circulating troponin in the setting of transient stress test-induced myocardial ischemia using an ultrasensitive assay: results from TIMI 35. Eur. Heart. J 2009, 30, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardena, M.; Campbell, V.; Richards, A.M.; Pemberton, C.J. Cardiac Biomarker Responses to Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography in Healthy Volunteers and Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 1492–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannssen, S.L.J.E.; de Fries, F.; Mingels, A.M.A.; Kleinnibbelink, G.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Mosterd, A.; et al. Exercise-induced cardiac troponin release in athletes with versus without coronary atherosclerosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 326, H1045–H1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turer, A.T.; Addo, T.A.; Martin, J.L.; Sabatine, M.S.; Lewis, G.D.; Gerszten, R.E.; et al. Myocardial ischemia induced by rapid atrial pacing causes troponin T release detectable by a highly sensitive assay: insights from a coronary sinus sampling study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 2398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnadottir, A.; Pedersen, S.; Bo Hasselbalch, R.; Goetze, J.P.; Friis-Hansen, L.J; . Bloch-Munster, A.M.; et al. Temporal Release of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T and I and Copeptin After Brief Induced Coronary Artery Balloon Occlusion in Humans. Circulation 2021, 143, 1095–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oemrawsingh, R.M.; Cheng, J.M.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Regar, E.; van Geus, R-J. ; et al. High-sensitivity troponin T in relation to coronary plaque characteristics in patients with stable coronary artery disease; results of the ATHEROREMO-IVUS study. Atherosclerosis 2016, 247, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

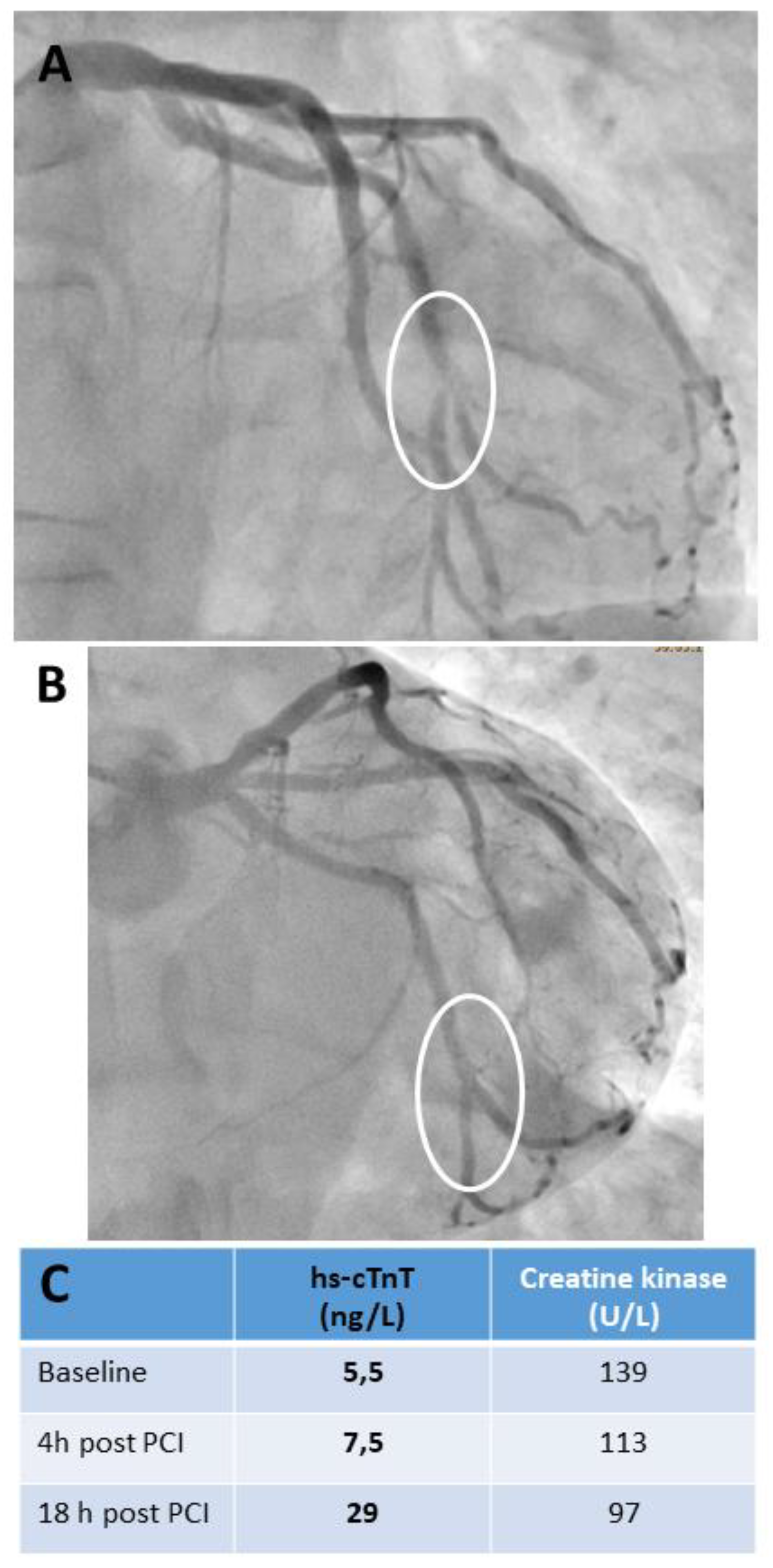

- Silvain, J.; Zeitouni, M.; Paradies, V.; Zheng, H.L.; Ndrepepa, G.; Cavallini, C.; et al. Cardiac procedural myocardial injury, infarction, and mortality in patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention: a pooled analysis of patient-level data. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitouni, M.; Silvain, J.; Guedeney, P.; Kerneis, M.; Yan, Y.; Overtchouk, P.; et al.; ACTION Study Group Periprocedural myocardial infarction and injury in elective coronary stenting. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, I.D.; Klein, L.W.; Shah, B.; Mehran, R.; Mack, M.J.; Brilakis, E.S.; et al. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; McFadden, E.P.; Farb, A.; Mehran, R.; Stone, G.W.; Spertus, J.; et al.; Academic Research Consortium Standardized End Point Definitions for Coronary Intervention Trials: The Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 2192–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; George, K.; Duan, F.; Tong, T.K.; Tian, Y. Histological evidence for reversible cardiomyocyte changes and serum cardiac troponin T elevations after exercise in rats. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e13083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, N.; George, K.; Whyte, G.; Gaze, D.; Collinson, P.; Shave, R. Cardiac troponin T release is stimulated by endurance exercise in healthy humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1813–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aengevaeren, V.L.; Baggish, A.L.; Chung, E.H.; George, K.; KLeiven, O.; Mingels, A.M.A; et al. Exercise-induced cardiac troponin elevation: from underlying mechanisms to clinical relevance. Circulation 2021, 144, 1955–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.; Lee, K.K.; Stewart, S.D.; Wild, A.; Fujisawa, T.; Ferry, A.V.; et al. Effects of exercise intensity and duration on cardiac troponin release. Circulation 2020, 141, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharhag, J.; Urhausen, A. , Schneider, G.; Hermann, M.; Schuhmacher, K.; Haschke, M.; et al. Reproducibility and clinical significance of exercise-induced increases in cardiac troponins and N-terminal N-termional pro brain natriuretic peptide in endurance athletes. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2006, 13, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Gaze, D.; Mohan, S.; Williams, K.L.; Sprung, V.; George, K.; et al. Post-exercise cardiac troponin release is related to exercise training history. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 33, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Gerche, A.; Burns, A.T.; Mooney, D.J.; Inder, W.J.; Taylor, A.J.; Bogaert, J.; et al. Exercise-induced right ventricular dysfunction and structural remodelling in endurance athletes. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shave, R.; Oxborough, D. Exercise-induced cardiac injury: evidence from novel imaging techniques and highly sensitive cardiac troponin assays. Prog. in Cardiovasc. Disease 2012, 54, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlenkamp, S.; Leineweber, K.; Lehman, N.; et al. Coronary atherosclerosis burden, but not transient troponin elevation, predicts long-term outcome in recreational marathon runners. Basic Res. Card. 2014, 109, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aengevaeren, V.L.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Thompson, P.D.; Bakker, E.A.; George, K.P.; et al. Exercise-induced cardiac troponin I increase and incident mortality and cardiovascular events. Circulation 2019, 140, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skadberg, O.; Kleiven, O.; Bjorkavoll-Bergeth, M.; Melberg, T.; Bergseth, R.; Selvag, J.; et al. Highly increased troponin I levels following high-intensity endurance cycling may detect subclinical coronary artery disease in presumably healthy leisure sport cyclists: The North Sea Race Endurance Exercise Study (NEEDED) 2013. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Schoor, F.R.; Aengevaeren, V.L.; Hopman, M.T.; Oxborough, D.L.; George, K.P.; Thompson, P.D.; et al. Myocardial fibrosis in athletes. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muslimovic, A.; Friden, V.; Tenstad, O.; Starnberg, K.; Nystrom, S.; Wesen, E.; et al. The liver and kidneys mediate clearance of cardiac troponin in the rat. Sci. Rep. 6791. [Google Scholar]

- Streng, A.S.; de Boer, D.; van Doorn, W.P.; Kocken, J.M.; Bekers, O.; Wodzig, W.K. Cardiac troponin T degradation in serum is catalysed by human thrombin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 481, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klocke, F.J.; Copley, D.P.; Krawczyk, J.A.; Reichlin, M. Rapid renal clearance of immunoreactive canine plasma myoglobin. Circulation 1982, 65, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friden, V.; Starnberg, K.; Muslimovic, A.; Ricksten, S-E. ; Bjurman, C.; Forsgard, N.; et al. Clearance of cardiac troponin T with and without kidney function. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 50, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.E.; Coluccio, G.; Hirkaler, I.; Mikaelian, R.; Nicklaus, R.; Lipschutz, S.E.; et al. The complete pharmacokinetic profile of serum cardiac troponin I in the rat and dog. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 123, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.H.; Hasselbalch, R.B.; Strandkjaer, N.; Jorgensen, N.; Ostergaard, M.; Moller-Sorensen, P.H.; et al. Half-Life and Clearance of Cardiac Troponin I and Troponin T in Humans. Circulation 2024, 150, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, S.M.; Tuominen, T.J.K.; Raiko, K.I.S; Vasankari, T.; Aalto, R.; Hellman, T.A.; et al. Highly sensitive immunoassay for long form of cardiac troponin T using upconversion luminescence. Clin. Chem. 2024, 70, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerer-Lercher, A.; Halfinger, B.; Sarg, B.; Mair. J.; Puschendorf, B.; Griesmacher, A.; et al. Analysis of circulating forms of proBNP and NT-proBNP in patients with severe heart failure. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amplatz, B.; Sarg, B.; Faserl, K.; Hammerer-Lercher, A.; Mair, J.; Lindner, H.H. Exposing the High Heterogeneity of Circulating Pro B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Fragments in Healthy Individuals and Heart Failure Patients. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peronnet, E.; Becquart, L.; Poirier, F.; Cubizolles, M.; Choquet-Kastylevsky, G.; Jolivet-Reynaud, C. SELDI-TOF MS analysis of the cardiac troponin I forms present in plasma from patients with myocardial infarction. Proteomics 2006, 6, 6288–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Katrukha, I.A.; Zhang, L.; Shu, X.; Xu, A.; et al. Design and analytical evaluation of novel cardiac troponin assays targeting multiple forms of the cardiac troponin I–cardiac troponin T–troponin C complex and fragmentation forms. Clin. Chem. 2025, 71, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airaksinen, K.E.J.; Aalto, R.; Hellman, T.; Vasankari, T.; Lahtinen, A.; Wittfooth, S. Novel Troponin Fragmentation Assay to Discriminate Between Troponin Elevations in Acute Myocardial Infarction and End-Stage Renal Disease. Circulation 2022, 146, 1408–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riabkova, N.S.; Kogan, A.E.; Katrukha, I.A.; Vylegzhanina, A.V.; Bogomolova, A.P.; Alieva, A.K.; et al. Influence of Anticoagulants on the Dissociation of Cardiac Troponin Complex in Blood Samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci.

- Katrukha, A.G.; Bereznikova, A.V.; Esakova, T.V.; Petterson, K.; Lövgren, T.; Severina, M.E.; et al. Troponin I is released in blood stream of patients with acute myocardial infarction not in free form but as complex. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.H.B.; Feng, Y.J.; Moore, R.; Apple, F.S.; McPherson, P.H.; Buechler, K.F.; Bodor, G. Characterization of cardiac troponin subunit release into serum after acute myocardial infarction and comparison of assays for troponin T and I. Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, J.L.; Arrell, D.K.; Van Eyk, J.E. Troponin I degradation and covalent complex formation accompanies myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ. Res.

- McDonough, J. .L; Labugger, R.; Pickett, W.; Tse, M.Y.; MacKenzie, S.; Pang, S.C.; et al. Cardiac troponin I is modified in the myocardium of bypass patients. Circulation 2001, 103, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, I.; Bertinchant, J.P.; Granier, C.; Laprade, M.; Chocron, S.; Toubin, G.; et al. Determination of cardiac troponin I forms in the blood of patients with acute myocardial infarction and patients receiving crystalloid or cold blood cardioplegia. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labugger, R.; Organ, L.; Collier, C.; Atar, D.; van Eyk, J.E. Extensive troponin I and troponin T modification detected in serum from patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2000, 102, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, I.; Bertinchant, J.P.; Lopez, M.; Coquelin, H.; Granier, C.; Laprade, M.; et al. Determination of cardiac troponin I forms in the blood of patients with unstable angina pectoris. Clin. Biochem. 2002, 35, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahie-Wilson, M.N.; Carmichael, D.J.; Delaney, M.P.; Stevens, P.E.; Hall, E.M.; Lamb, E.J. Cardiac troponin T circulates in the free, intact form in patients with kidney failure. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, L.H.; Christensen, G.; Lund, T.; Serebruany, V.L.; Granger, C.B.; Hoen, I.; et al. Time course of degradation of cardiac troponin I in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 troponin substudy. Circ. Res. 2006, 99, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michielsen, E.C.; Diris, J.H.; Kleijnen, V.W.; Wodzig, W.K.; Van Dieijen-Visser, M.P. Investigation of release and degradation of cardiac troponin T in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, K.J.; Hall, E.M.; Fahie-Wilson, M.N.; Kindler, H.; Bailey, C.; Lythall, D.; Lamb, E.J. Circulating immunoreactive cardiac troponin forms determined by gel filtration chromatography after acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chem. 2010, 56, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaels, E.P.; Mingels, A.M.; van Rooij, T.; Collinson, P.O.; Prinzen, F.W.; van Dieijen-Visser, M.P. Time-dependent degradation pattern of cardiac troponin T following myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 2013, 59, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streng, A.S.; de Boer, D.; van Doorn, W.P.T.M.; Bouwman, F.G.; Mariman, E.C.M.; Bekers, O.; et al. Identification and characterization of cardiac troponin T fragments in serum of patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingels, A.M.; Cardinaels, E.P.; Broers, N.J.; van Sleeuwen, A.; Streng, A.S.; van Dieijen-Visser, M.P.; et al. Cardiac Troponin T: Smaller Molecules in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease than after Onset of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijk, X.M.R.; Claassen, S.; Enea, N.S.; Li, P.; Yang, S.; Brouwer, M.A.; et al. Cardiac troponin I is present in plasma of type 1 myocardial infarction patients and patients with troponin I elevations due to other etiologies as complex with little free I. Clin. Biochem. 2019, 73, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vylegzhanina, A.V.; Kogan, A.E.; Katrukha, I.A.; Koshkina, E.V.; Bereznikova, A.V.; Filatov, V.L.; et al. Full-size and partially truncated cardiac troponin complexes in the blood of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chem. 2019, 65, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, S.A.J.; Cramer, G.E.; Dieker, H-J. ; Gehlmann, H.; Ophuis, T.J.M.O.; Aengevaeren, W.R.M., et al. Cardiac troponin composition characterization after non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: relation with culprit artery, ischemic time window, and severity of injury. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrukha, I.A.; Riabkova, N.S.; Kogan, A.E.; Vylegzhanina, A.V.; Mukharyamova, K.S.; Bogomolova, A.P.; et al. Fragmentation of human cardiac troponin T after acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 542, 117281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroemen, W.H.M.; Mezger, S.T.P.; Masotti, S.; Clerico, A.; Bekers, O.; de Boer, D.; et al. Cardiac troponin T: only small molecules in recreational runners after marathon completion. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2019, 3, 909–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airaksinen, K.E.J.; Paana, T.; Vasankari, T.; Salonen, S.; Tuominen, T.; Linko-Parvinen, A.; et al. Composition of cardiac troponin release differs after marathon running and myocardial infarction. Open Heart, 0029. [Google Scholar]

- Airaksinen, K.E.J.; Tuominen, T.; Paana, T.; Hellman, T.; Vasankari, T.; Salonen, S.; et al. Novel troponin fragmentation assay to discriminate between Takotsubo syndrome and acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2024, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Katrukha, I.A.; Zhang, L.; Shu, X.; Xu, A.; et al. Characterization of cardiac troponin fragment composition reveals potential for differentiating etiologies of myocardial injury. Clin. Chem. 2025, 71, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damen, S.A.J.; Vroemen, W.H.M.; Brouwer, M.A.; Mezger, S.T.P.; Suryapranata, H.; van Royen, N.; et al. Multi-Site Coronary Vein Sampling Study on Cardiac Troponin T Degradation in Non-ST segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Toward a More Specific Cardiac Troponin T Assay. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2019, 8, e012602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, K.M.; Hammarsten, O.; Lindahl, B. Differences between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and I in stable populations: underlying causes and clinical implications. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2023, 61, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, K.M.; Hammarsten, O.; Aldous, S.J.; Cullen, L.; Greenslade, J.H.; Lindahl, B.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic performance of the ratio between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I and troponin T in patients with chest pain. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0276645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

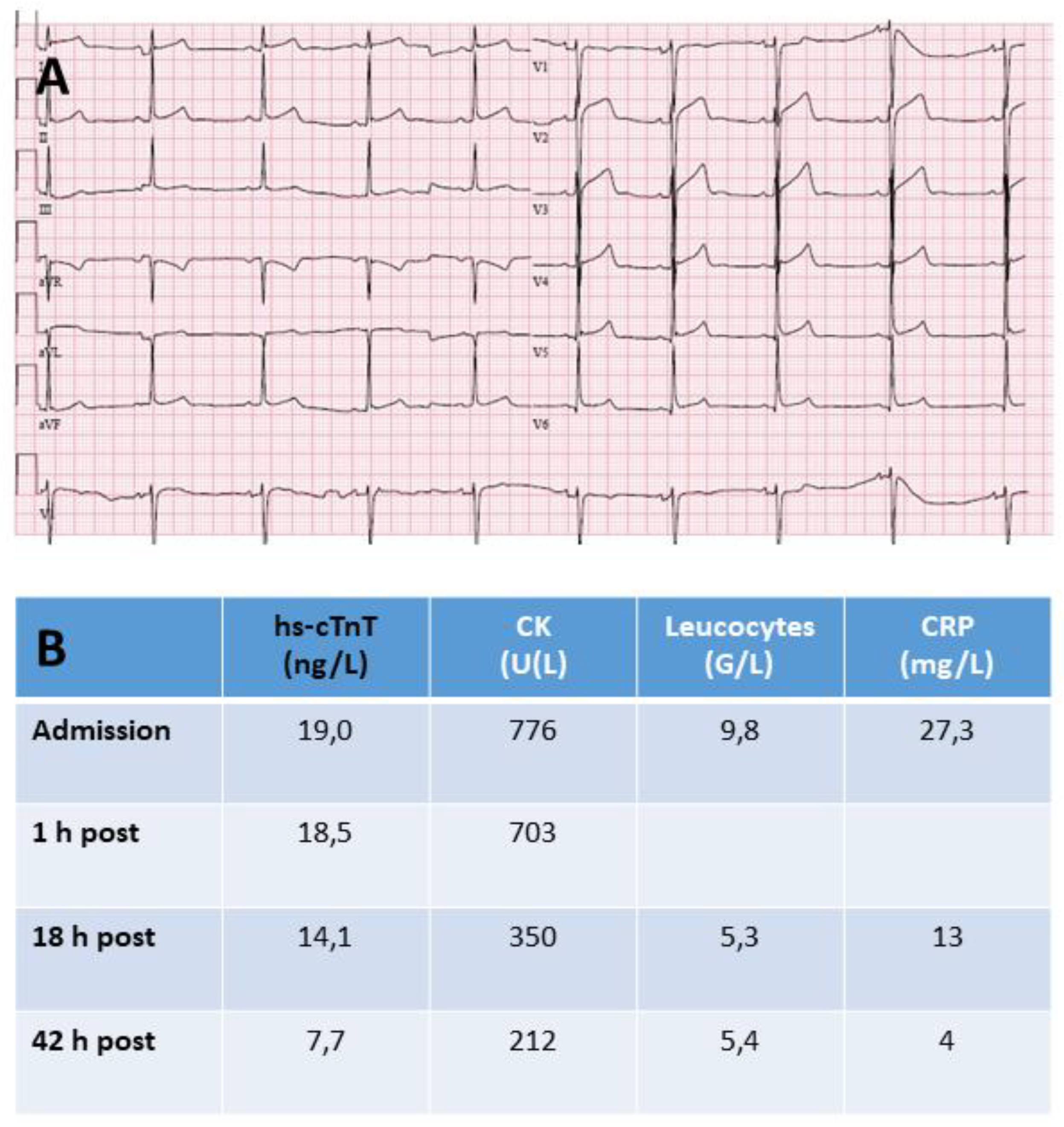

- Laugaudin, G.; Kuster, N.; Petiton, A.; et al. Kinetics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and I differ in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary coronary intervention. Eur. Heart. J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2016, 5, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, L.; Aldous, S.; Than, M.; Greenslade, J.H.; Tate, J.R.; George, P.M.; et al. Comparison of high sensitivity troponin T and I assays in the diagnosis of non-ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in emergency patients with chest pain. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 47, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubini Gimenez, M.; Twerenbold, R.; Reichlin, T.; Wildi, K.; Haaf, P.; Schaefer, M.; et al. Direct comparison of high-sensitivity-cardiac troponin I vs. T for the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2303–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wereski, R.; Kimenai, D.M.; Taggart, C.; Doudesis, D.; Lee, K.K.; Lowry, M.T.H.; et al. Cardiac Troponin Thresholds and Kinetics to Differentiate Myocardial Injury and Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2021, 144, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, W.; Vroemen, W.H.M.; Smulders, M.W.; van Suijlen, J.D.; van Cauteren, Y.J.M.; Bekkers, S.; et al. High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I and T Kinetics after Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2020, 5, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinstadler, S.J.; Feistritzer, H.J.; Klug, G.; Mair, J.; Minh-Duc Tu, A.; Kofler, M.; et al. High-sensitivity troponin T for prediction of left ventricular function and infarct size one year following ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 202, 188–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, J.; Wagner, I.; Morass, B.; Fridrich, L.; Lechleitner, P.; Dienstl, F.; et al. Cardiac troponin I release correlates with myocardial infarction size. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1995, 33, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wagner, I.; Mair, J.; Fridrich, L.; Artner-Dworzak, E.; Lechleitner, P.; Morass, B.; et al. Cardiac troponin T release in acute myocardial infarction is associated with scintigraphic estimates of myocardial scar. Coron. Artery Dis. 1993, 4, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

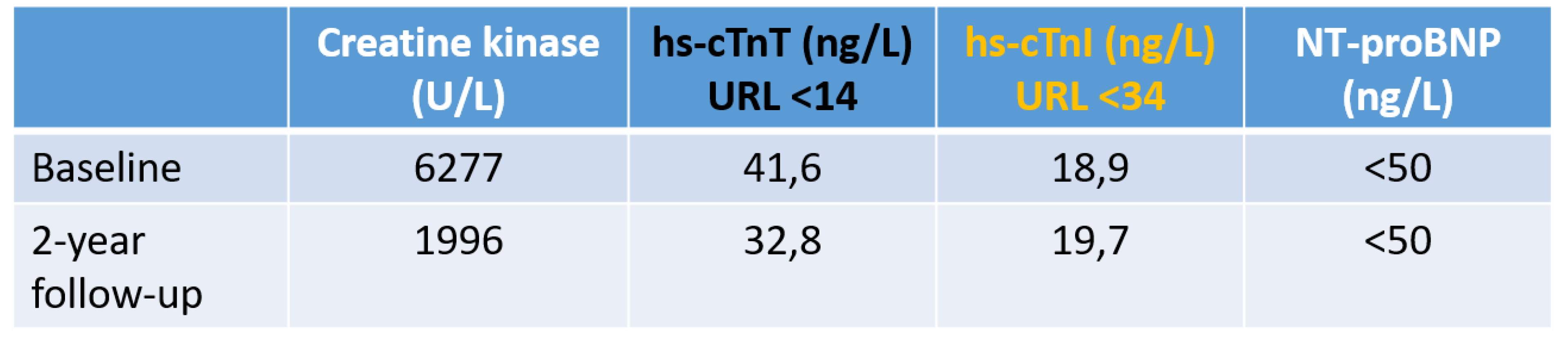

- Starnberg, K.; Friden, V.; Muslimovic, A.; Ricksten, S-V. ; Nystrom, S.; Forsgard, N.; et al. A possible mechanism behind faster clearance and higher peak concentrations of cardiac troponin I compared with troponin T in acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerer-Lercher, A.; Erlacher, P.; Bittner, R.; Korinthenberg, R.; Skladal, D.; Sorichter, S.; et al. Clinical and experimental results on cardiac troponin expression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin. Chem. 2001, 47, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlacher, P.; Lercher, A.; Falkensammer, J.; Nassanov, M.I. , Shtutman, V.Z., Puschendorf, B.; et al. Cardiac troponin and beta-type myosin heavy chain concentrations in patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2001, 306, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.S.; Vasile, V.C.; Milone, M.; Saenger, A.K.; Olson, K.N.; Apple, F.S. Diseased skeletal muscle. A noncardiac source of increased circulating concentrations of cardiac troponin T. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittoo, D.; Jones, A.; Lecky, B.; Neithercut, D. Elevation of cardiac troponin T but not cardiac troponin I in patients with neuromuscular diseases: implications for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2411–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wens, S.C.A.; Schaaf, G.J.; Michels, M.; Kruijshaar, M.E.; van Gestel, T.J.M.; In`t Groen, S.; et al. Elevated plasma cardiac troponin T levels caused by skeletal muscle damage in Pompe disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2016, 9, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.; Liesinger, L.; Birner-Gruenberger, R.; Stojakovic, T.; Scharnagl, H.; Dieplinger, B.; et al. Elevated cardiac troponin T in patients with skeletal myopathies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1540–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Fay de Lavallaz, J.; Prepoudis, A.; Wendebourg, M.J.; Kesenheimer, E.; Kyburz, D.; Daikeler, T.; et al. Skeletal muscle disorders: a non-cardiac source of cardiac troponin T. Circulation 2022, 145, 1764–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, L.H.; Heckmann, M.B.; Bailly, G.; Finke, D.; Procureur, A.; Power, J.R.; et al. Cardiomuscular Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Prognostication of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Myocarditis. Circulation 2023, 148, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saggin, L.; Gorza, L.; Ausoni, S.; Schiaffino, S. Cardiac troponin T in developing, regenerating and denervated rat skeletal muscle. Development 1990, 110, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.A.W.; Malouf, N.N.; Oakeley, A.E.; Pagani, E.D.; Allen, P.D. Troponin T isoform expression in humans: a comparison among normal and failing adult heart, fetal heart, and adult and fetal skeletal muscle. Circ. Res. 1991, 69, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, M.A.; Dhoot, G.K. Identification of and pattern of transitions of cardiac, adult slow and slow skeletal musle-like embryonic isoforms of troponin T in developing rat and human skeletal muscles. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1991, 12, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesnard, L.; Samson, F.; Espinasse, I.; Durand, J.; Neveux, J.Y.; Mercadier, J.J. Molecular cloning and developmental expression of human cardiac troponin T. FEBS Letters 1993, 328, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaurin, M.D.; Apple, F.S.; Voss, E.M.; Herzog, C.A.; Sharkey, S.W. Cardiac troponin I, cardiac troponin T, and creatine kinase MB in dialysis patients without ischemic heart disease: evidence of cardiac troponin T reexpression in skeletal muscle. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodor, G.S.; Survant, L.; Voss, E.M.; Smith, S.; Porterfield, D.; Apple, F.S. Cardiac troponin T composition in normal and regenerating human skeletal muscle. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricchiuti, V.; Apple, F.S. RNA expression of cardiac troponin T isoforms in diseased human skeletal muscle. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 2129–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, B.; Baum, H.; Fischer, P.; Quasthoff, S.; Neumeier, D. Expression of messenger RNA of cardiac isoforms of troponin T and I in myopathic skeletal muscle. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 114, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, P.E.; McGill, D.; Potter, J.M.; Koerbin, G.; Apple, F.S.; Talaulikar, G. Multiple biomarkers including cardiac troponin I and T measured by high-sensitivity assays, as predictors of long-term mortality in patients with chronic renal failure who underwend dialysis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 115, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buiten, M.S.; de Bie, M.K.; Rotmans, J.I.; et al. Serum cardiac troponin I is superior to troponin T as a marker for left ventricular dysfunction in clinically stable patients with end-stage renal disease. PloS One 2015, 10, e0134245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twerenbold, R.; Wildi, K.; Jaeger, C.; Rubini Gimenez, M.; Reiter, M.; Reichlin, M.; et al. Optimal cutoff levels of more sensitive cardiac troponin assays for early diagnosis of myocardial infarction in patients with renal dysfunction. Circulation 2015, 131, 2041–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolland, M.; Amenitsch, J.; Schreiber, N.; Ginthör, N.; Schuller, M.; Riedl, R.; et al. Changes in cardiac troponin during hemodialysis depend on hemodialysis membrane and modality: a randomized crossover trial. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 17, sfad297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaze, D.C.; Collinson, P.O. Cardiac troponin I but not cardiac troponin T adheres to polysulfone dialyser membranes in an in vitro hemodialysis model: explanation for lower cTnI concentrations following dialysis. Open Heart, 0001. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, C.; Zehelein, J.; Remppis, A.; Müller-Bardorff, M.; Katus, H.A. Cardiac troponin T in patients with end stage renal disease: absence of expression in truncal skeletal muscle. Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isoform | Gene, location |

Expression | Aminoacids | Molecular mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cTnC | TNNC1, 3p21.1 |

Heart, slow-twitch skeletal muslce |

161 | 18.4 kDa |

| cTnI | TNNI3, 19q13.42 |

Heart | 210 | 24 kDa |

| cTnT | TNNT2, 1q32.1 |

Heart, skeletal muscle (fetal period, chronic injury) | 287-298* | about 34-36 kDa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).