Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

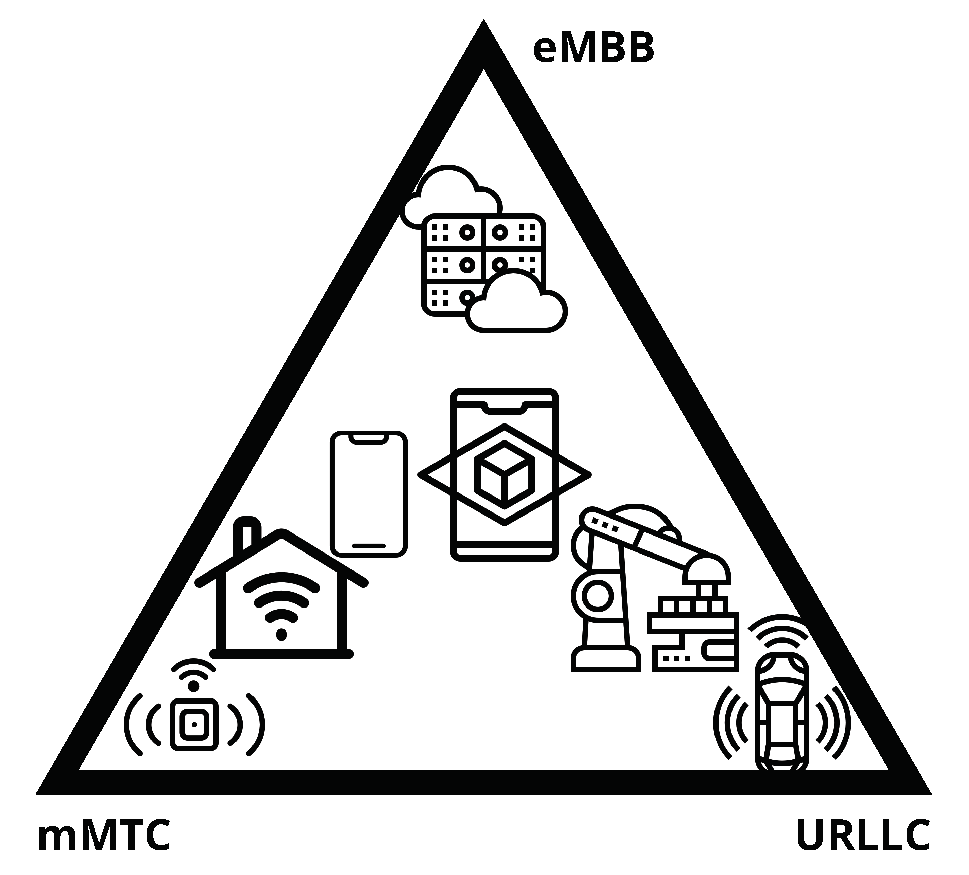

- Enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) to increase speed and capacity. The expected requirements for this case are a data transmission speed of up to and a latency of less than .

- Ultra Reliable, Low-Latency Communications (URLLC), which aims to guarantee low latency and high reliability to comply with requirements of vertical market segments such as industrial, health, transportation, and aviation. Their target requirements are a probability of error from to and a latency of less than .

- Massive Machine-Type Communications (mMTC) support a massive number of connected objects, such as Internet of Things (IoT) environments. To reach this use case, it needs a density of up to 1 million devices per square kilometer and a battery life of up to 10 years without recharging.

- the necessity of an increasing amount of antennas due to the use of higher frequencies.

- the demand for ensuring compatibility between 5G and previous networks considering latency requirements.

- the growing number of devices.

- and deployment complexity, to name a few.

1.2. Scope and Limitations

- Blockchain uses a chain of blocks to record and verify transactions. Each block contains a set of transactions validated by a consensus mechanism.

- Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), a ledger based on a graph structure to record and verify transactions. These transactions are linked in a directed graph rather than a linear chain. DAG ledgers can be more scalable and efficient than linear chains, and they are often used for applications such as IoT and micropayments.

- Distributed Consensus Ledger, a distributed ledger that uses a consensus mechanism to validate transactions and achieve agreement among network participants. It does not necessarily use a chain of blocks to record transactions.

- Federated Ledger, a distributed ledger controlled by a consortium or group of organizations. In this case, participants have a defined level of access and control over the ledger and consensus is reached among participants rather than through a public blockchain or consensus algorithm.

- Hybrid Ledger, that combines different types of DLT.

1.3. Research Questions

- What are the main threats to the Radio Access Networks (RANs)?

- How are Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLT) applicable to enhancing RANs?

- What do studies apply to increase security in RANs?

- How do studies apply DLTs to increase security in RANs?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of DLT usage to improve security in RANs?

- What are the proposed future works (open challenges)?

1.4. Contributions

- We elaborated the SLR protocol, which can be used to replicate or update this study in the future.

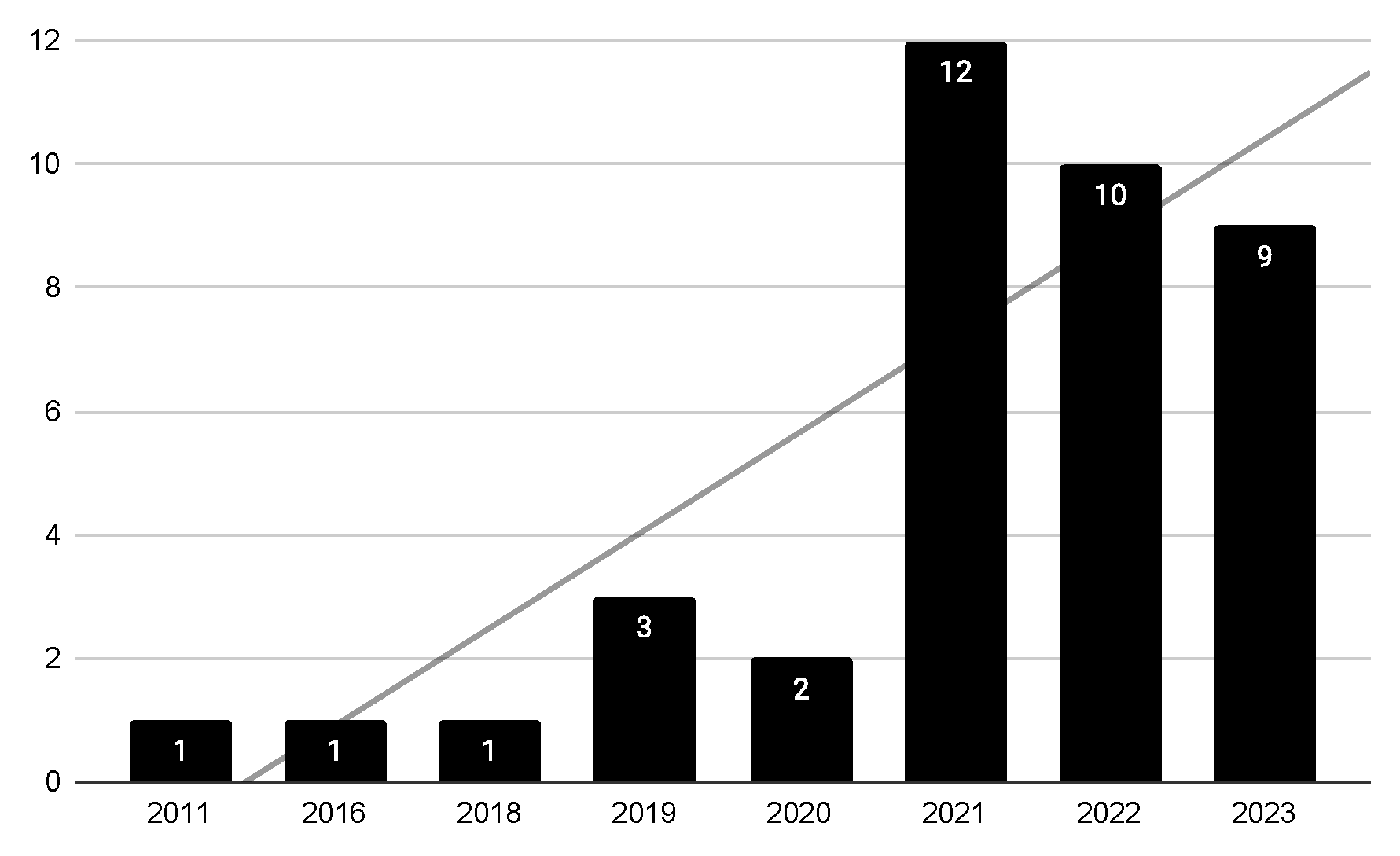

- We defined and reviewed 39 papers considering they explore threats, vulnerabilities, attacks, and solutions for RAN security.

- We analyzed and presented the information extracted from the accepted papers, classifying threats, vulnerabilities, and solutions.

- We presented the state-of-the-art related to security issues in RAN scenarios, discussing important points.

1.5. Review Structure

2. Background

2.1. Security Concepts

-

Attack: a malicious attempt to collect, disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy the system information or the system itself.

- -

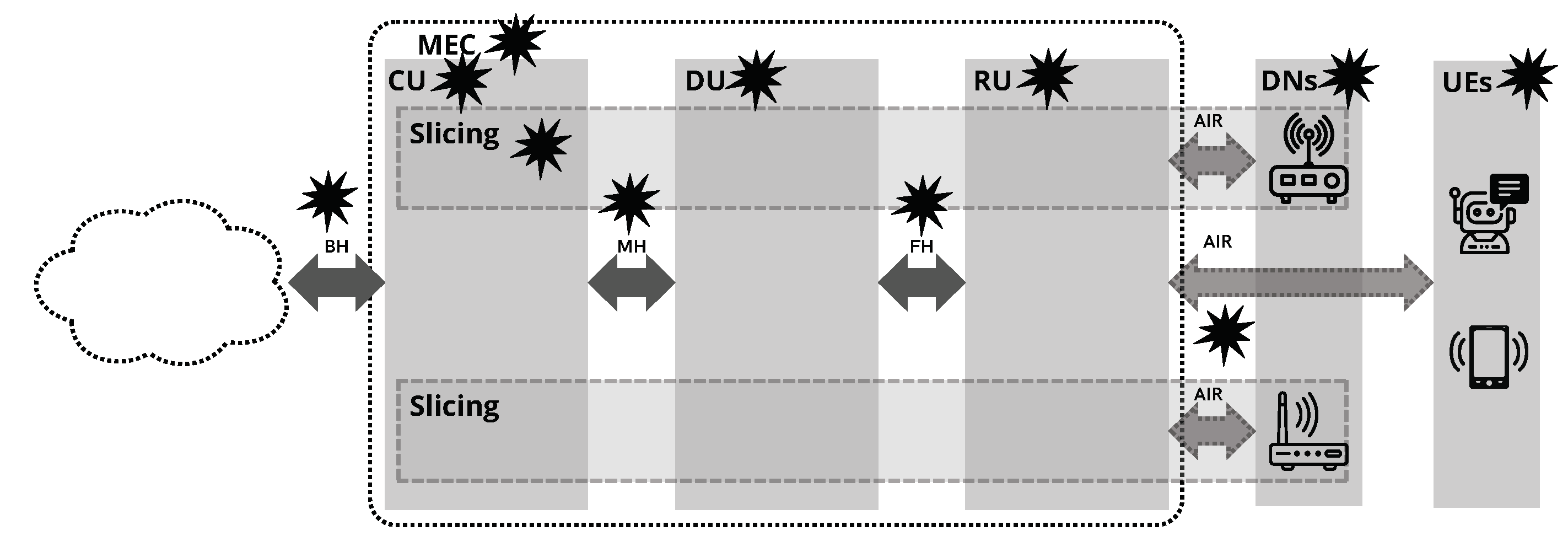

- Attack Surface [23], in the context of the Radio Access Network (RAN), is the set of potential entry points that adversaries can exploit to gain unauthorized access to the network. For example, we can cite the introduction of Network Slicing (NS), a feature that creates virtual slices across the RAN to allow unique network access for several enterprises and applications [24]. However, malware from a slice may be leveraged to infect another slice in the same hardware. A certificateless signature could be a countermeasure, as discussed in SubSection 5.2.5.

-

Security: established and maintained measures to protect the system/component/data. It may involve six functions:

- -

- Deterrence, the threat discouraging.

- -

- Avoidance, reducing the probability of a loss or the value of the potential loss.

- -

- Prevention, countermeasures to minimize possible security violations.

- -

- Detection, identifying occurred or in progress violations.

- -

- Recovery, actions to restore the normal state of a system.

- -

- Correction, updating the security architecture to reduce or eliminate risks.

-

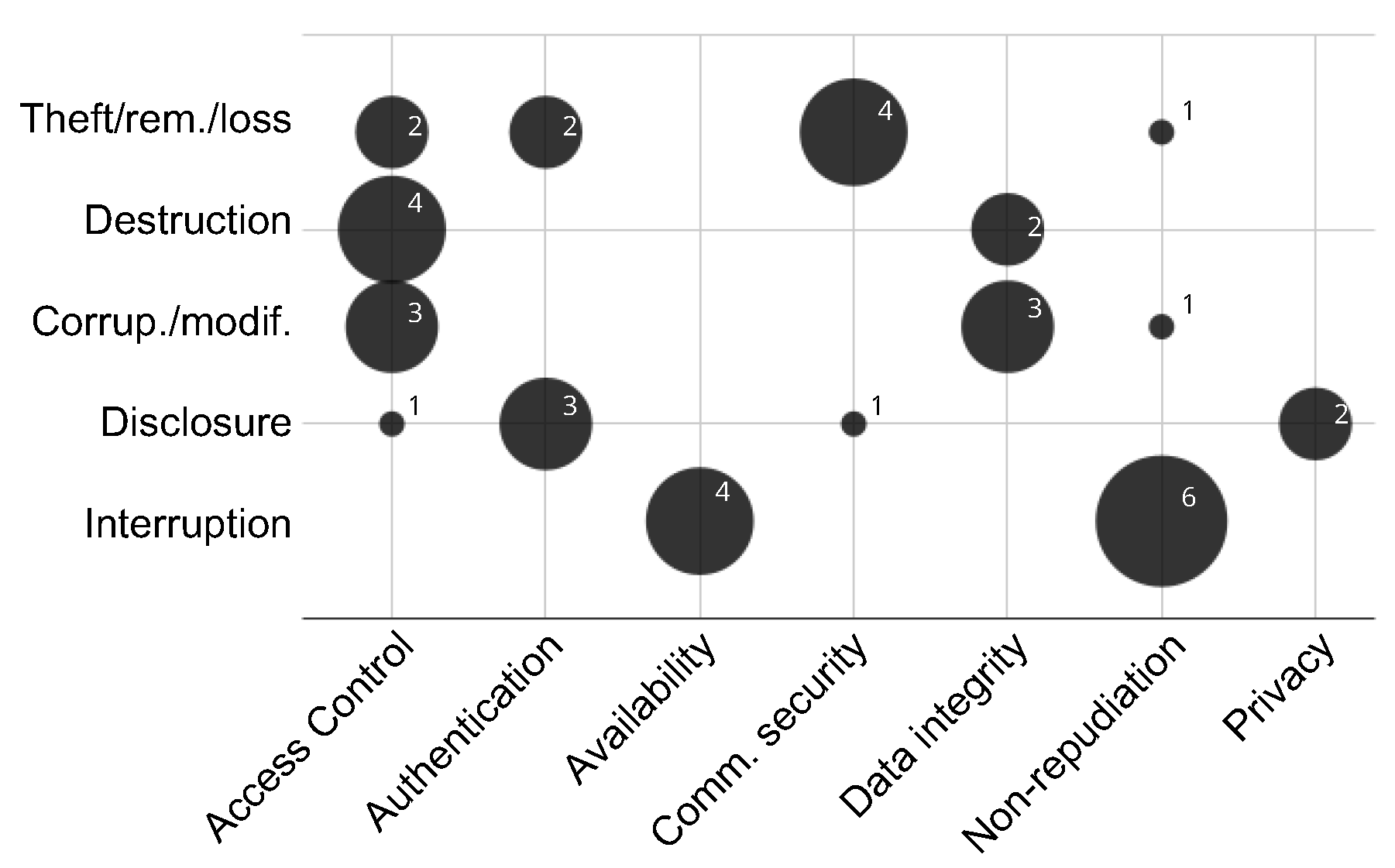

Threat: an intentional or accidental danger that might occur if an attacker is successful. The considered threats [25] in this paper are:

- -

- Destruction of information or other resources.

- -

- Corruption or modification of information.

- -

- Theft, removal, or loss of information or other resources.

- -

- Disclosure of information.

- -

- Interruption of services.

- Vulnerability: a security breach, that could be a flaw or weakness in a system’s design, implementation, or operation and management, and could be exploited to violate a system.

- Access control, the protection against unauthorized use of network resources.

- Authentication, the confirmation of entity identities.

- Availability, the ensuring of authorized access and information availability.

- Communication security, the protection against data diversion or interception.

- Data confidentiality, the protection against data unauthorized disclosure.

- Data integrity, the guarantee of correctness or accuracy of the data.

- Non-repudiation, the correctness in the association between actions and actors.

- Privacy, the protection of the information.

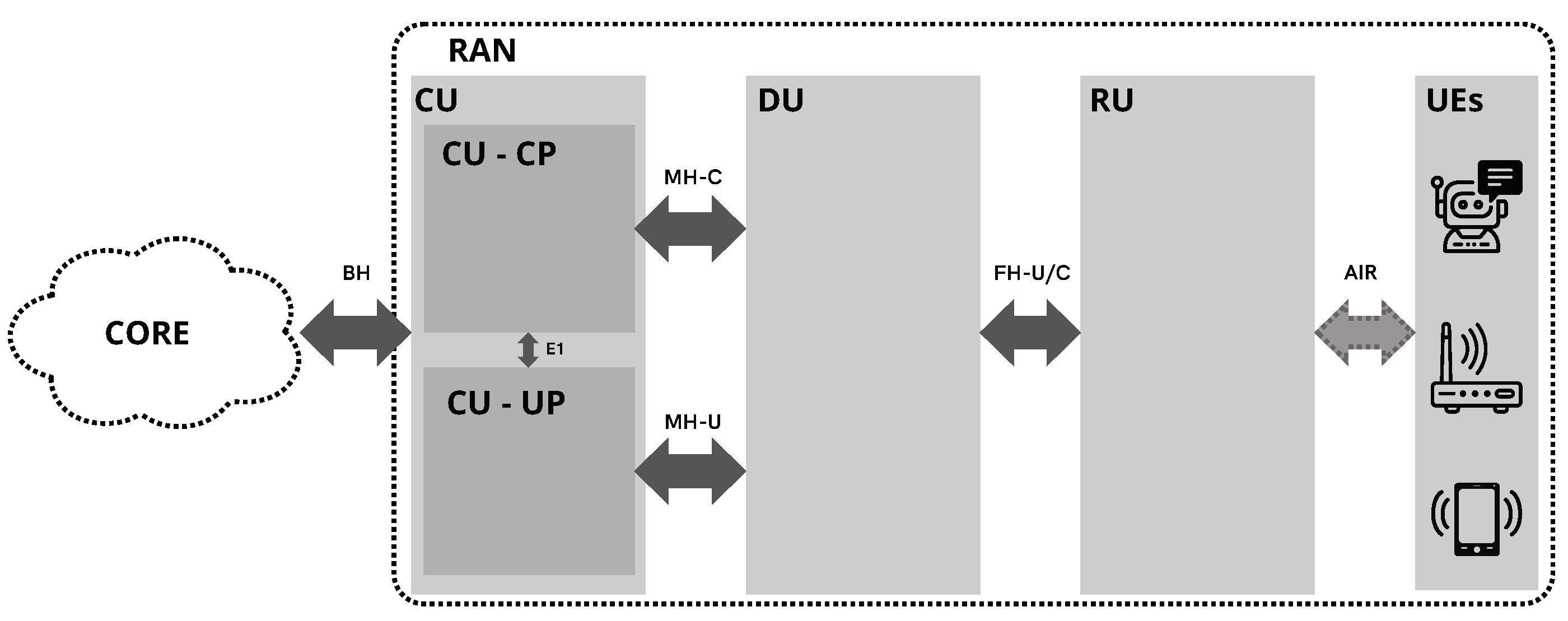

2.2. RAN Architecture

- The Radio Unit (RU) contains radio functions and is located near the antennas.

- The Baseband Unit (BBU) is responsible for radio management, resource utilization, sharing, and other operations like modulation and demodulation, bit-to-symbol mapping, and coding and decoding.

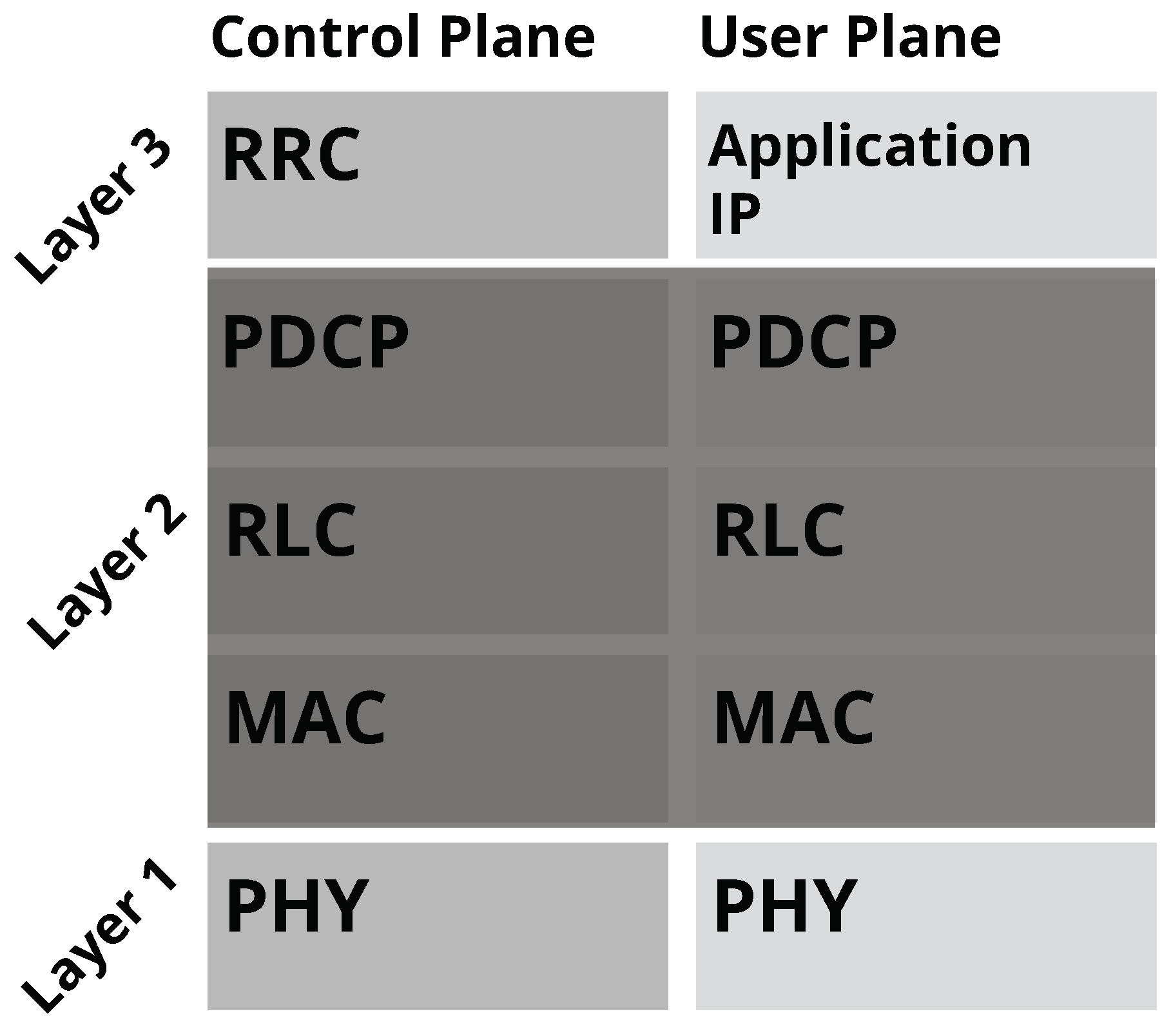

2.2.1. Protocol Layer Stack

- The Centralized Unit (CU) implements the higher layers of the 3GPP stack, namely the Radio Resource Control (RRC) layer, the Service Data Adaptation Protocol (SDAP) layer, and the Packet Data Convergence Protocol (PDCP) layer, among others. It is divided into two interfaced modules, one dedicated to the user plane (UP) and the other to the control plane (CP), due to the Control and User Plane Separation (CUPS) architecture. The CUPS architecture provides flexibility for network improvement compared to the conventional architecture where both planes have a less pronounced separation [38].

- The Distributed Unit (DU) is responsible for some functionalities of the physical layer, the Medium Access Control (MAC), and Radio Link Control (RLC), among others.

- The Medium Access Control (MAC) protocol multiplexes RLC packet-data units (PDUs) through logical channels and performs mapping between logical and transport channels [42]. Other MAC layer functions include uplink and downlink scheduling, scheduling information reporting, hybrid-ARQ processing and retransmissions in 4G-LTE (automatic repeat request, ARQ, is an error-control method based on acknowledgments), and multiplexing/demultiplexing data for carrier aggregation. [41].

- The Radio Link Control (RLC) protocol’s main functions include segmentation and concatenation, retransmission handling, duplicate detection, and in-sequence delivery to upper layers [42]. Regardless of its generation, the RLC layer supports three transmission modes – Transparent Mode (TM) to broadcast data, Unacknowledged Mode (UM) to support data loss-tolerant services such as voice, and Acknowledged Mode (AM) with an ARQ retransmission mechanism for services such as TCP/IP and RRC signaling that require data reliability. RLC UM and AM modes support data segmentation and resegmentation at the transmitter, and AM provides duplicate detection [41].

- The Packet Data Convergence Protocol (PDCP) provides data packet encryption and integrity protection for the control plane and, for the user plane, ciphering/deciphering, header compression/decompression using Robust Header Compression (RoHC) for IP traffic, in-sequence delivery, duplicate detection, and retransmission (continuously in 5G-NR networks, especially during handovers in 4G-LTE ones) [39,41]. The PDCP layer does not have synchronicity constraints with the lower layers, and 3GPP assumes that the 4G dual connectivity functions can be used as a baseline in 4G/5G interworking since PDCP functions are access/service-agnostic [42].

2.3. Distributed Ledger Technologies

- the transaction validation, to verify the individual transaction compliance with the established rules;

- the record validation, to verify the record can be done according to the protocol; and

- the transaction finality, to determine if the transaction is finalized and, therefore, immutable.

- Paxos [62] provides a fault-tolerant implementation in an asynchronous message-passing system in which clients send commands to a leader that assigns these commands and, in a second step, a message is sent to a set of acceptor processes.

- Raft [60] elects a leader to coordinate the replication actions of the DLT.

- Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) [60] is also based on a leader-follower approach but demands agreement among a high percentage of the participants to attach a new transaction.

3. Threat Modeling

- User Equipment(UE) is the equipment served by the RAN, which can be a smartphone, a sensor, or anything that can connect to the RAN.

- Air Interface(Air) is the interface between the UE and the RAN.

- Radio Unit(RU) contains radio functions and is located near the antennas.

- Fronthaul(FH) is the interface between the RU and the DU.

- Distributed Unit(DU), where the most decentralized base band functionalities are deployed.

- Midhaul(MH) is the interface between the DU and the CU.

- Centralized Unit(CU), where the high-layered base-band functionalities are deployed.

- Backhaul(BH) is the interface between the RAN and the Core Network.

4. Vulnerabilities, Threats, Attacks, and Solutions

4.1. Overview of Security Threats and Vulnerabilities in Access Networks

-

Process: when the vulnerability is related to common processes.

- -

- Authentication issues, such as lack of, weak, or broken authentication. If RAN nodes are not properly authenticated, attackers could impersonate legitimate devices, carry out brute-force attacks, or decrypt communications.

- -

- Broken access control or lack of its validation. In this case, adversaries can access sensitive network functions and exploit misconfigured interfaces to inject malicious traffic or disrupt services.

- -

- Data storage problems, i.e., unprotected storage. This may result in leakage of private data and network settings.

-

Code: when the vulnerability is related to the software and development process. In this sense, it is important to highlight the difference between coding and development. While development focuses on managing actions and overseeing the software creation process, coding is focused on implementation, translating ideas into actionable code using programming languages [110]. Since analyzing these details is beyond the scope of this work, it was decided to consider them under the same heading for the sake of simplicity. In this context, we can cite encryption mechanisms that are both conceptual (designed through development) and practical (implemented via coding) and, so, can then be viewed at different implementation layers.

- -

- Lack of cryptography, which attackers can exploit to lack private data or set up a rogue BTS.

- -

- Codification or development problems, such as the absence of secure coding practices. Vulnerabilities in the software running on the network or in the UE can arise from poor coding practices, such as buffer overflows, injection flaws, improper error handling, lack of input validation, which could allow attackers to inject malicious commands or data.

- -

- Cryptographic algorithm lag or weakness. Weak or deprecated cryptographic algorithms can make RANs susceptible to attacks, i.e., brute-force attacks.

-

Communication: when the vulnerability is related to protocols or data transmission. This class of vulnerability may affect RANs due to loss of confidentiality if an attacker exposes sensitive user and network data, loss of integrity if adversaries modify communications or inject malicious data, loss of availability due to jamming attacks or physical tampering, and reputation damage, that can reduce user trust and lead to regulatory penalties.

- -

- Lack or weakness of security mechanisms, such as resistance to tampering.

- -

- Communication problems can include unreliable communication channels, ease of UE impersonation, and susceptibility to eavesdropping due to the openness of the wireless interface.

-

Operation: when the vulnerability is related to the nodes’ use or configuration.

- -

- Outdated assets can include lack of updates, network exposure, incorrect software configuration, and bad user practices, to name a few.

4.2. Considered Attacks

- Network unavailability (NU) attacks make it impossible for the user to access the network.

- Data corruption (DC) attacks aim to intercept, inject, corrupt, delete, or steal data to manipulate communication.

- Unauthorized access (UA) attacks include malicious actions to gain unauthorized access.

- Data leakage (DL) attacks aim to acquire and steal confidential and sensitive information.

- Physical resource spoliation (PR) attacks are the ones that menace hardware and other physical resources.

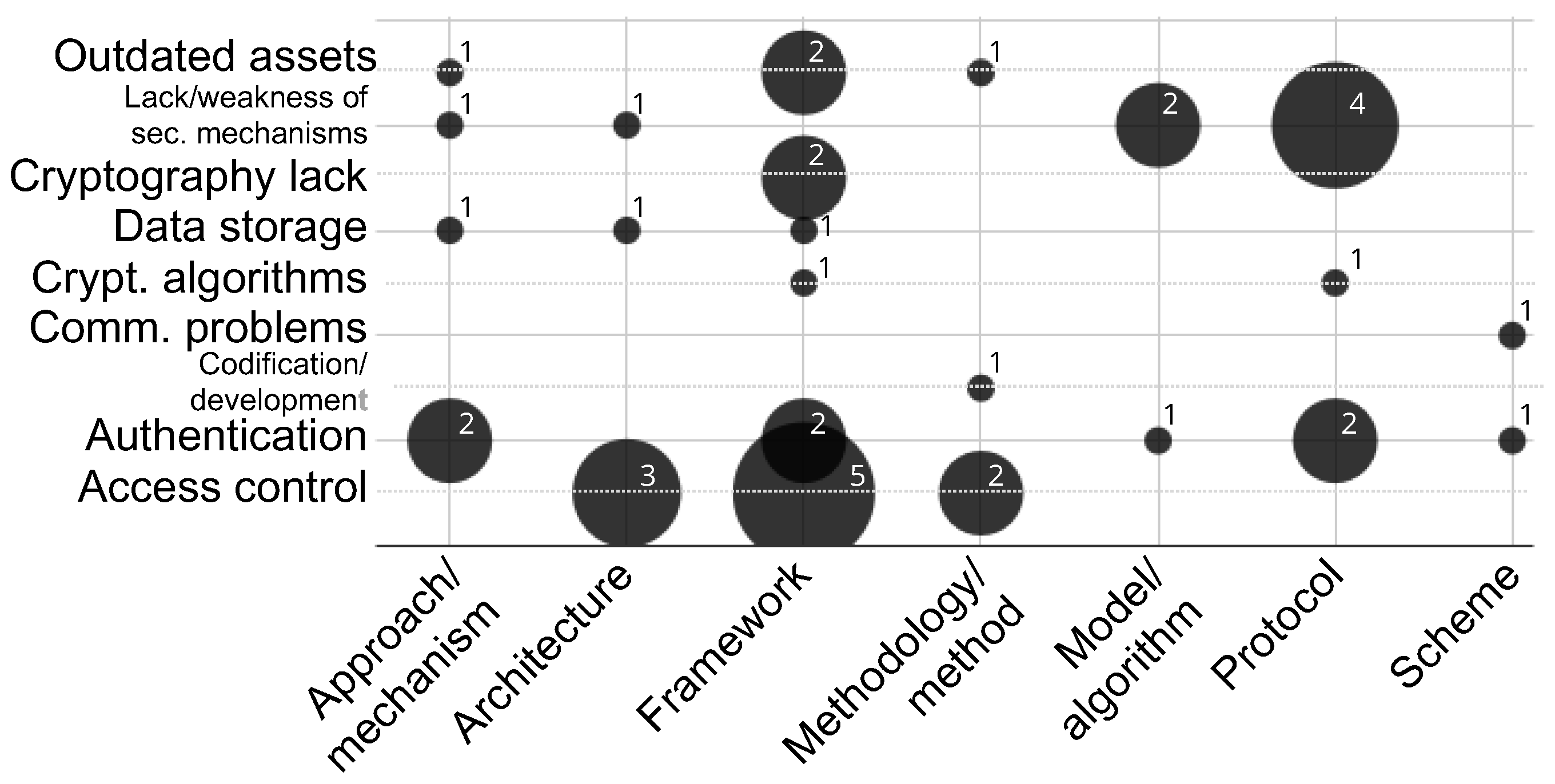

4.3. Description of Suggested Security Solutions

- Approach/Mechanism.

- Architecture.

- Framework.

- Methodology/Method.

- Model/Algorithm.

- Protocol.

- Scheme.

- Detect.

- Detect/Mitigate.

- Mitigate.

- Planning.

- Mitigating threats and addressing vulnerabilities in edge-based IoT networks such as authentication issues, network attacks, and user-to-root attacks to safeguard data [103].

- Developing defense systems against threats in 5G networks, including malware, phishing, hacking, DoS, DDoS, SQL injections, and MitM attacks [88].

- Detecting and preventing attacks such as DoS, Botnet attacks, Network intrusion, MitM attacks, and Quantum attacks to mitigate risks related to theft or loss of information and resource threats [86].

5. Discussion

5.1. Answers to Research Questions

5.1.1. RAN Threats

5.1.2. DLT Usage to Enhance RANs

- DLT-based intrusion detection can be employed to detect and prevent intrusions. Furthermore, it can ensure trusted communications [81].

5.1.3. Approaches to Increase RAN Security

5.1.4. DLTs to Increase RAN Security

- RANs can reach secure and transparent resource allocation and transactions due to the ability of DLTs to increase resource trading since they enforce participants to behave honestly and follow predefined rules [82].

5.1.5. Advantages and Disadvantages of DLT Usage to Improve Security in RANs

5.1.6. Future Work Suggestions

- Incorporating blockchain and IoT technologies in mobile networks with, for example, artificial intelligence techniques to accelerate towards decentralized networks in smart cities and other applications and analyzing the performance of blockchain/mobile network combination for improved efficiency and scalability [73,79,84].

- Testing authentication, encryption, and integrity over the wireless link in Femtocells [100].

5.2. Key Findings and Implications

5.2.1. Blockchain

5.2.2. RRC

5.2.3. IDS/IPS

5.2.4. Fronthaul

5.2.5. Network Slicing

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Methodology

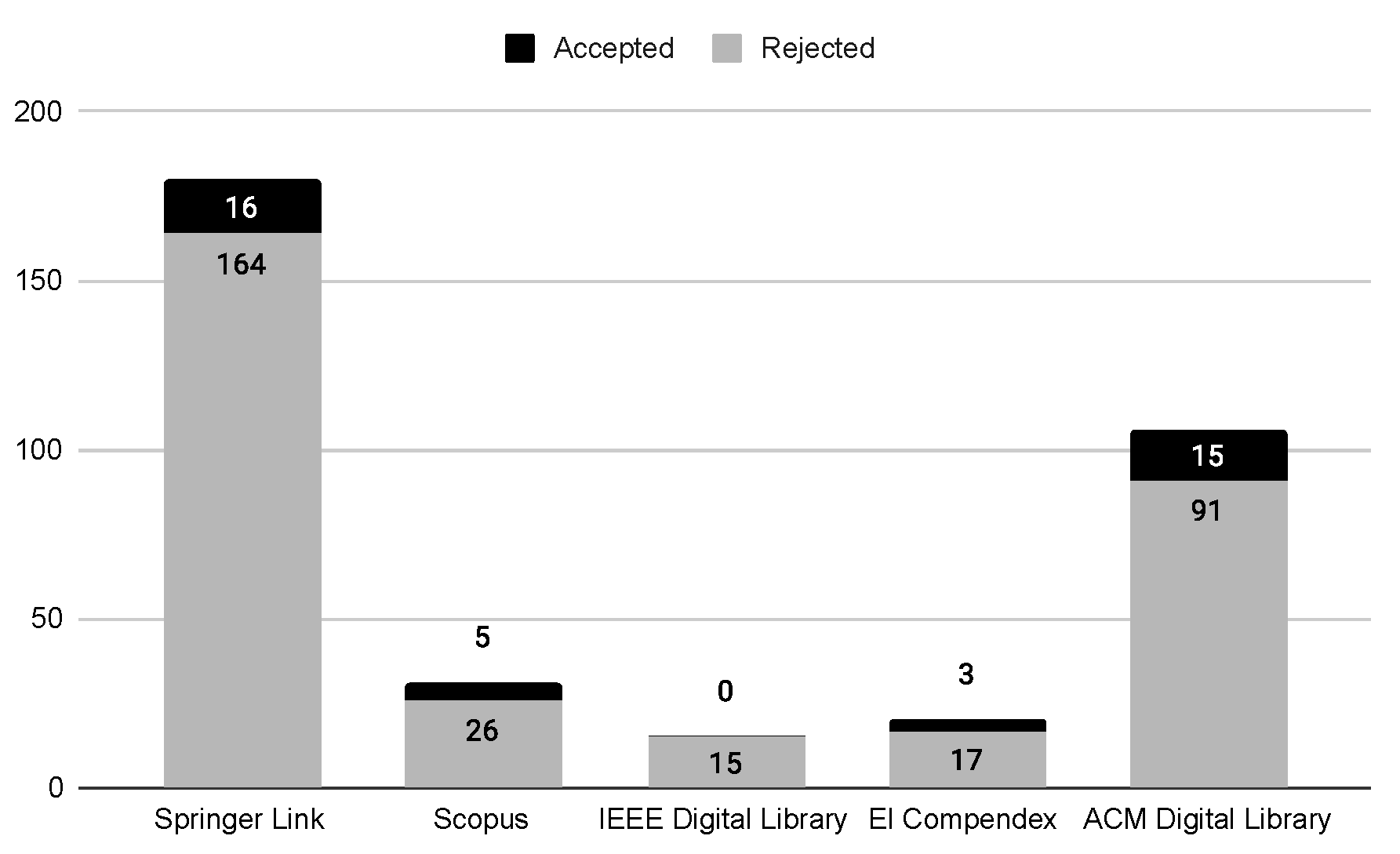

Appendix A.1. Search Strategy

- Population: Radio Access Network, RAN, Open Radio Access Network, OpenRAN, Open RAN, Open-RAN, O-RAN.

- Intervention: Distributed Ledger Technology, Distributed Ledger, DLT, Security Mechanisms, IOTA, Blockchain, Distributed Consensus Ledger, Federated Ledger.

- Context: Security, Privacy, Confidentiality, Integrity, Trustworthiness, Protection, Availability.

- Outcome: Solution, Technique, Tool, Approach, Method, Mechanism, Advantage, Benefit, Positive Point, Disadvantage, Drawback, Negative Point.

Appendix A.2. Search String

Appendix A.3. Search Repositories

| Repository | URL |

|---|---|

| ACM Digital Library | https://dl.acm.org/ |

| EI Compendex | https://www.engineeringvillage.com/ |

| IEEE Digital Library | https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/ |

| Scopus | https://www.scopus.com/ |

| Springer Link | https://link.springer.com/ |

Appendix A.4. Selection Criteria

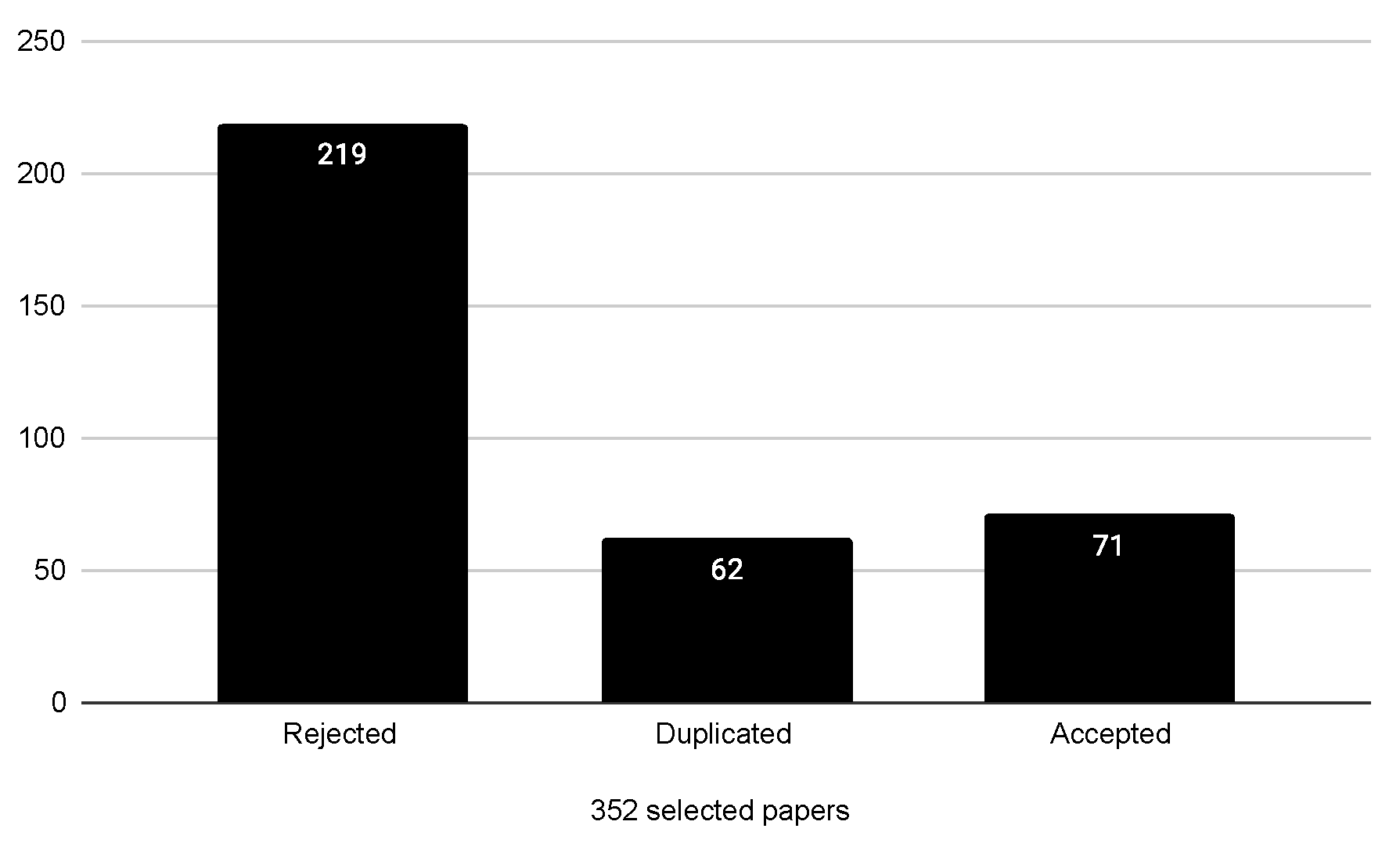

Appendix A.5. Selection Procedure

- Exclusion of duplicate papers.

- Exclusion of white papers, short papers, and book chapters.

- Exclusion of papers that don’t answer the research questions.

- Exclusion of papers about lower layers of interconnection.

- Exclusion of master and PhD theses.

- Exclusion of papers not written in English.

- Exclusion of papers published before 2010.

- Exclusion of secondary and tertiary studies.

- Exclusion of papers not published in journal or conference papers.

- Exclusion of papers whose full content is not available.

- Exclusion of papers not related to the topics.

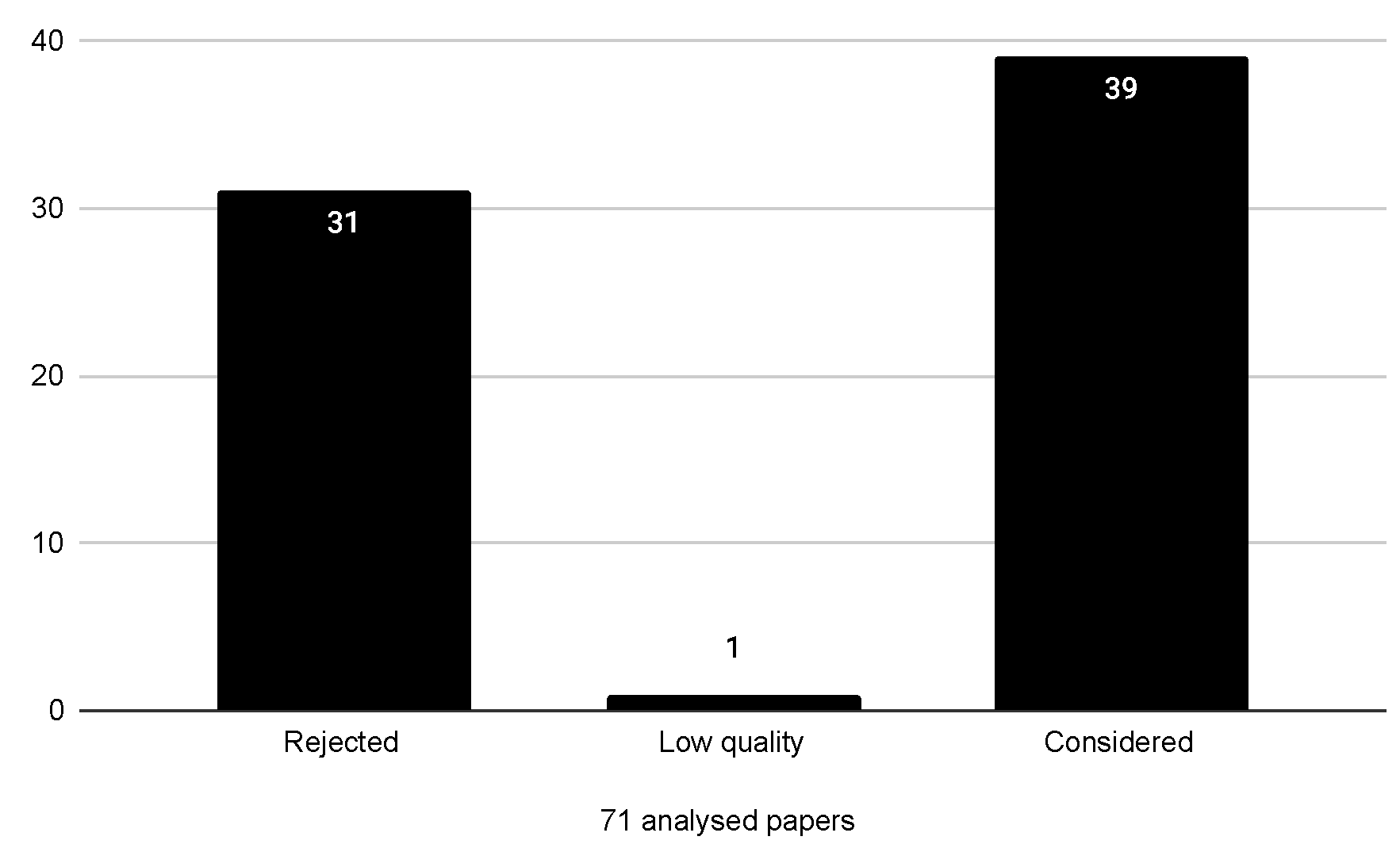

- Deep analysis of the remaining papers to identify irrelevant ones.

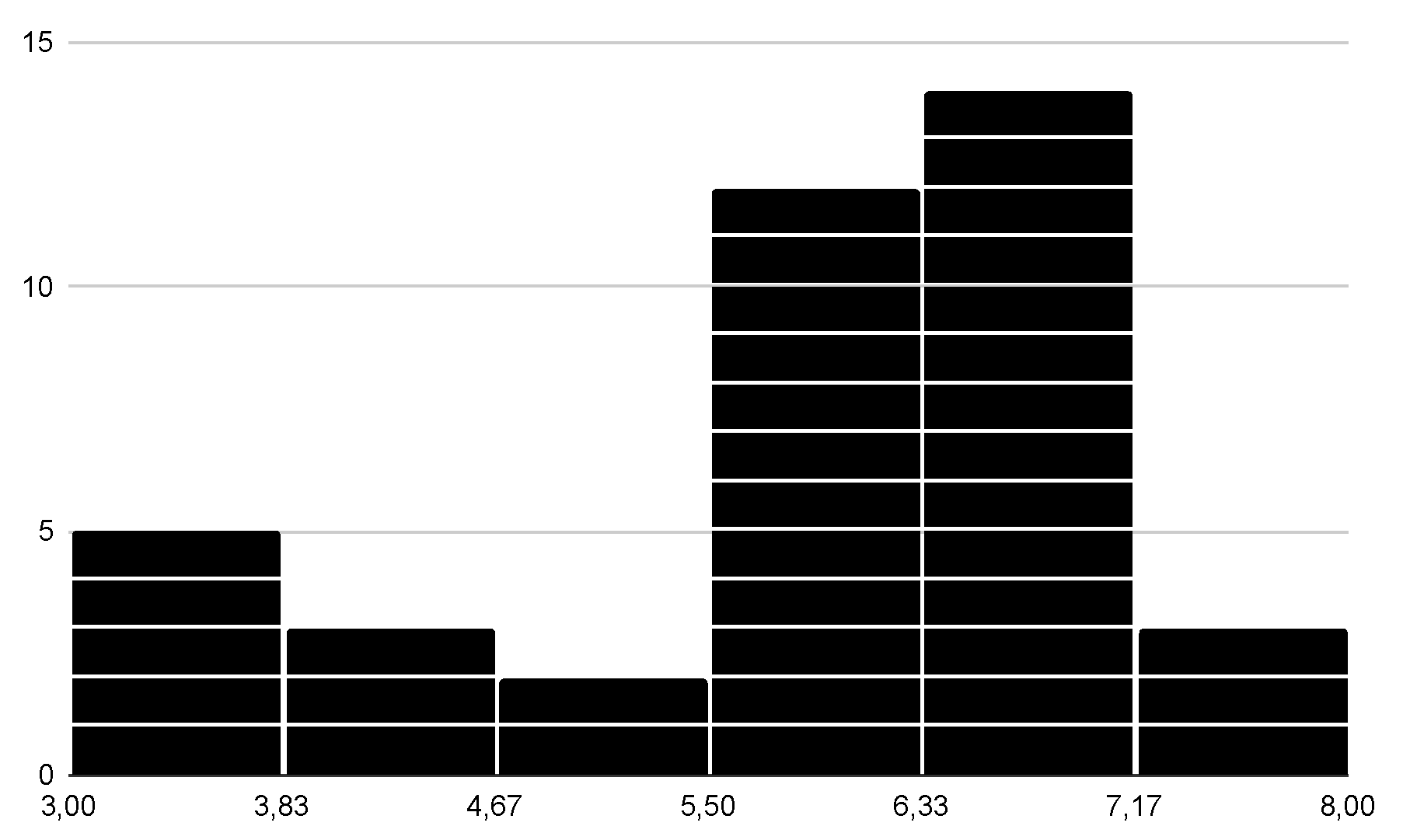

Appendix A.6. Quality Assessment

- Yes = 1

- Partially = 0.5

- No = 0

-

Has the paper been peer-reviewed and published in a reputable journal?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the paper was published in a vehicle with a minimum impact factor of 2.

-

Is the methodology used in the paper appropriate and clearly explained?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the paper has a clear methodology and is well written.

-

Does the paper provide a thorough and balanced review of the literature on RAN or DLTs?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the paper has a broad approach to evaluating the formal literature on RAN or DLTs.

-

Are the research results presented and supported by the data?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the paper validates the results in a well-structured way.

-

Are the conclusions of the paper supported by the evidence presented?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the conclusion is coherent with the results and the argumentation.

-

Are any potential limitations or biases in the research acknowledged and discussed?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the structure of the paper respects the scientific method.

-

Does the paper contribute new and relevant information to the field of RAN or DLTs?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the paper is innovative.

-

Are the references cited in the paper current and relevant to RAN or DLTs?

- -

- Only receives 1 if the paper is well-grounded, with good, related references.

- High quality, if the paper scored above 5.

- Medium quality, if the paper scored between 3.5 and 5.

- Low quality if the paper scored up to 3.

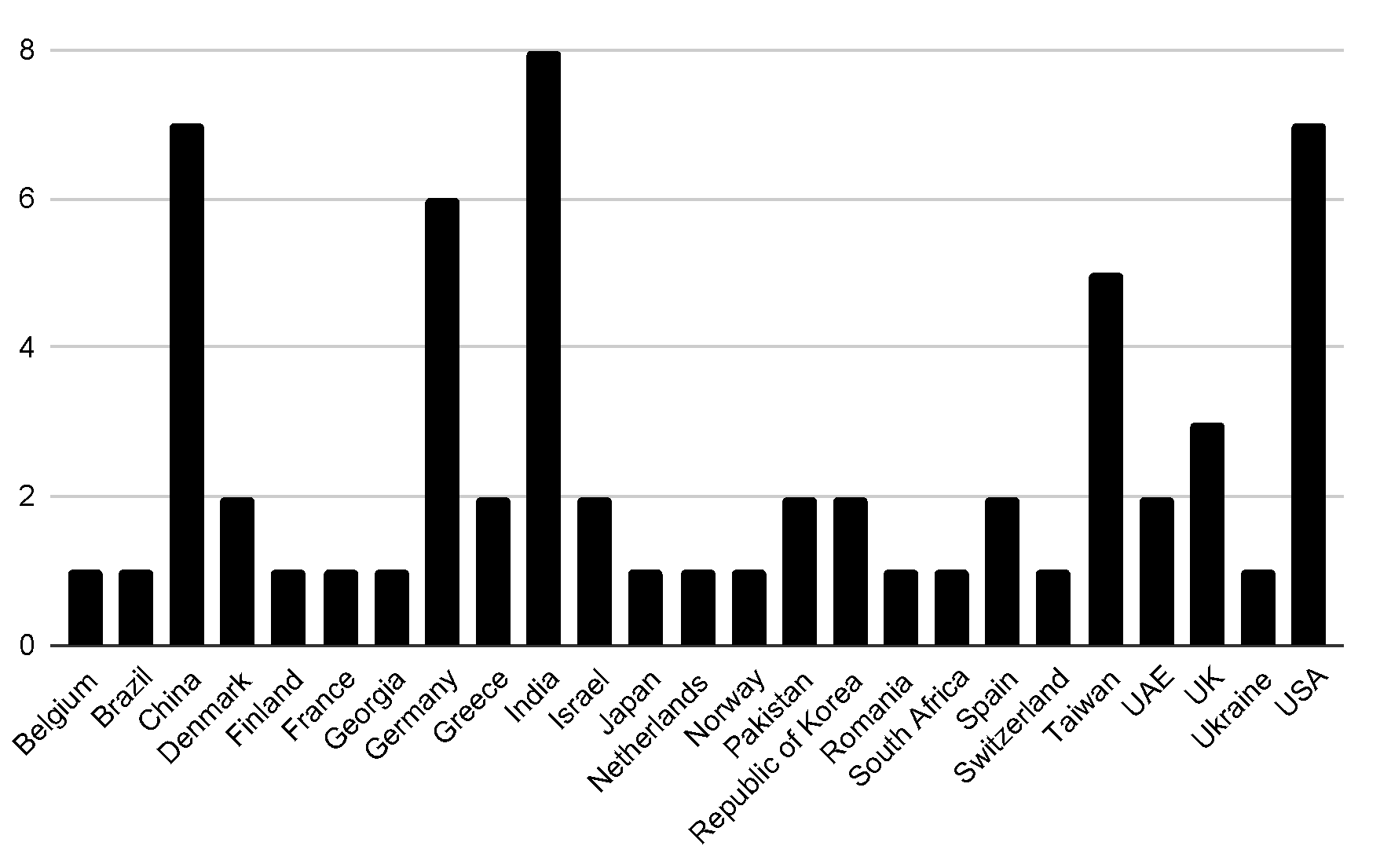

Appendix A.7. Data Extraction

- Title

- Authors

- Abstract

- Year

- Type of paper

- Conference/journal name

- Country(ies) where the research was carried out

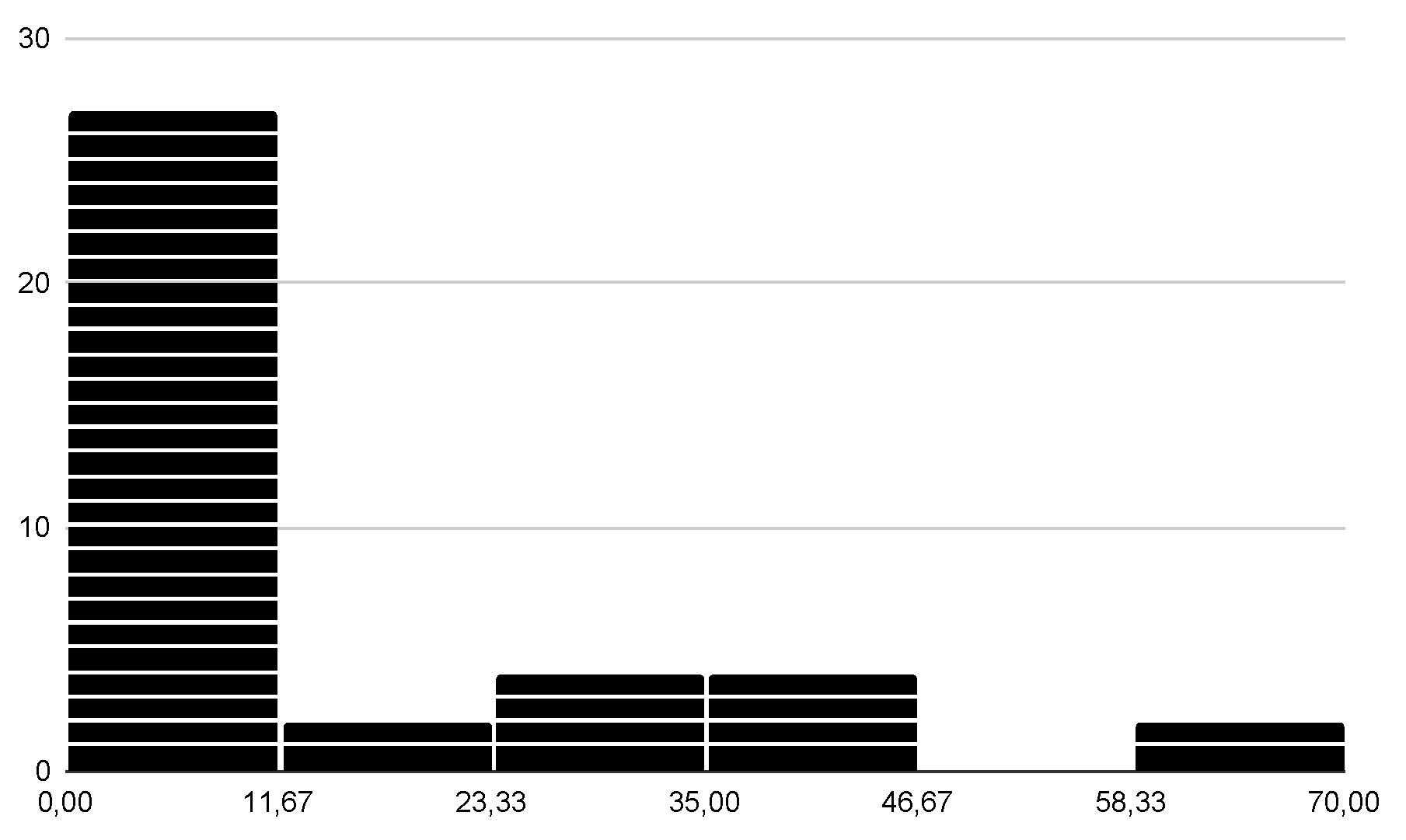

- Number of pages

- Number of citations

- Quality

- Identified RAN threats

- DLT employment to enhance RANs

- Approaches to increase RAN security

- DLT usage to increase RAN security

- Pros and cons of DLT to improve RAN security

- Future work suggestions

Appendix B. General Results

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | QoS flow is a stream between the UE and the data network that follows the data flow with different levels of priority, data rate, latency, and so on. |

References

- Vivier, G. IoT: How 5G differs from LTE; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Olwal, T.O.; Djouani, K.; Kurien, A.M. A Survey of Resource Management Toward 5G Radio Access Networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2016, 18, 1656–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udell, C. 5G Security Concerns & Privacy Risks, 2023.

- Firouzi, R.; Rahmani, R. Delay-sensitive resource allocation for IoT systems in 5G O-RAN networks. Internet of Things 2024, 26, 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU, I.T.U. Recommendation ITU-R M.2083-0 (09/2015) IMT Vision – Framework and overall objectives of the future development of IMT for 2020 and beyond, 2015.

- Condoluci, M.; Mahmoodi, T. Softwarization and virtualization in 5G mobile networks: Benefits, trends and challenges. Computer Networks 2018, 146, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- hacen Diallo, E.; Agha, K.A.; Martin, S. TRADE-5G: A Blockchain-Based Transparent and Secure Resource Exchange for 5G Network Slicing. In Blockchain: Research and Applications; 2024; p. 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, T.; Portmann, M. The (In)Security of Virtualization in Software Defined Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 66584–66594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- for Mobile Communications GSMA, G.S. 5G Security Issues. White paper, Global System for Mobile Communications - GSMA, 2019.

- Hari Krishna, S.; Sharma, R. Survey on application programming interfaces in software defined networks and network function virtualization. Global Transitions Proceedings 2021, 2, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Telecommunications Agency. Resolution no. 740/2020, 2020.

- Chaer, A.; Salah, K.; Lima, C.; Ray, P.P.; Sheltami, T. Blockchain for 5G: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Waikoloa, HI, USA; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, D. What’s blockchain got to do with edge computing?, 2023.

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele, UK, Keele University 2004, 33, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S.; Budgen, D.; Brereton, P.; Turner, M.; Linkman, S.; Jørgensen, M.; Mendes, E.; Visaggio, G. Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Technical report, Technical report, ver. 2.3 ebse technical report. ebse, 2007.

- Houy, S.; Schmid, P.; Bartel, A. Security Aspects of Cryptocurrency Wallets—A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 56, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachiega, J.; Costa, B.; Carvalho, L.R.; Rosa, M.J.F.; Araujo, A. Computational Resource Allocation in Fog Computing: A Comprehensive Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooshideh, M.; Beheshti, A.; Qi, Y.; Farhood, H.; Simpson, M.; Gatland, N.; Soltany, M. Presentation Attack Detection: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 1, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, L.; Cimato, S.; Damiani, E. A Comparative Analysis of Current Cryptocurrencies. In Proceedings of the ICISSP; 2018; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencic, F.M.; Zarko, I.P. Distributed Ledger Technology: Blockchain Compared to Directed Acyclic Graph. CoRR, abs/1804.10013. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, B.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Yan, W. LedgerDB: A Centralized Ledger Database for Universal Audit and Verification. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2020, 13, 3138–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirey, R. RFC 4949: Internet Security Glossary, Version 2, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Group, N.C. ENISA Report on the cybersecurity of Open RAN, 2022.

- Frank, W.; Rahman, A.; Daiekh, S.; Lee, J. Thinking like a 5G attacker: Leverage attack graphs to illuminate 5G network vulnerabilities, 2022.

- ITU, I.T.U. Recommendation X.800 (03/91) Security architecture for open systems interconnection for CCITT applications, 1991.

- Ahmad, I.; Shahabuddin, S.; Kumar, T.; Okwuibe, J.; Gurtov, A.; Ylianttila, M. Security for 5G and Beyond. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2019, 21, 3682–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU, I.T.U. Recommendation X.805 (10/03) Security architecture for systems providing end-to-end communications, 2003.

- 3GPP. 5G; NG-RAN; Architecture description (3GPP TS 38.401 version 15.10.0 Release 15). Technical Specification (TS) 38.401, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), 2023. Version 15.10.0.

- Singh, S.K.; Singh, R.; Kumbhani, B. The Evolution of Radio Access Network Towards Open-RAN: Challenges and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference Workshops (WCNCW), Seoul, South Korea; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Prasad, A.R.; Mihovska, A.; Nidhi, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. 6G Enabling Technologies: New Dimensions to Wireless Communication, 1 ed.; River Publishers: New York, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erni, S.; Kotuliak, M.; Leu, P.; Roeschlin, M.; Capkun, S. AdaptOver: Adaptive Overshadowing Attacks in Cellular Networks. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing And Networking; MobiCom ’22; New York, NY, USA, 2022, pp. 743–755. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.E.; Santos, G.L.; Ferreira, L.; Rocha, É.d.S.; de Souza, L.M.F.; Moreira, A.L.C.; Kelner, J.; Sadok, D. Flying to the Clouds: The Evolution of the 5G Radio Access Networks. In The Cloud-to-Thing Continuum: Opportunities and Challenges in Cloud, Fog and Edge Computing; chapter 3; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Architectural Evolution and Novel Design of Fiber-Wireless Access Networks. In Fiber-Wireless Convergence in Next-Generation Communication Networks; chapter 8; Springer Cham: Cham, 2017; pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- America, A. Understanding Cable and Antenna Analysis, 2021.

- Dik, D.; Berger, M.S. Open-RAN Fronthaul Transport Security Architecture and Implementation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 46185–46203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Why do open RAN? | C-RAN, vRAN and open-RAN explained, 2023.

- Polese, M.; Bonati, L.; D’Oro, S.; Basagni, S.; Melodia, T. Understanding O-RAN: Architecture, Interfaces, Algorithms, Security, and Research Challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2023, 25, 1376–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, X.; Ge, X.; Li, Q. Coverage and Handover Analysis of Ultra-Dense Millimeter-Wave Networks With Control and User Plane Separation Architecture. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 54739–54750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, I.; Mildh, G.; Rune, J.; Wallentin, P.; Vikberg, J.; Schliwa-Bertling, P.; Fan, R. Tight Integration of New 5G Air Interface and LTE to Fulfill 5G Requirements. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 81st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 05 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeydan, E.; Mangues-Bafalluy, J.; Baranda, J.; Requena, M.; Turk, Y. Service Based Virtual RAN Architecture for Next Generation Cellular Systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 9455–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 5G Radio Access Network Architecture: The Dark Side of 5G; Sirotkin, S., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, C.; Ericson, M.; Rugeland, P.; Da Silva, I.; Zaidi, A.; Aydin, O.; Venkatasubramanian, V.; Filippou, M.C.; Mezzavilla, M.; Kuruvatti, N.; et al. 5G Multi-RAT Integration Evaluations Using a Common PDCP Layer. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 85th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring), Glasglow, UK, 06 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 5G NR and Enhancements, 1 ed.; Shen, J., Du, Z., Zhang, Z., Yang, N., Tang, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Radarweg 29, PO Box 211, 1000 AE Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuzzi, A.; Perala, P.H.; Boggia, G.; Pentikousis, K. 3GPP radio resource control in practice. IEEE Wireless Communications 2012, 19, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnuru, S.; Nakarmi, P.K. Berserker: ASN.1-based Fuzzing of Radio Resource Control Protocol for 4G and 5G. In Proceedings of the 2021 17th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), Bologna, Italy, 10 2021; pp. 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.R.; Echeverria, M.; Karim, I.; Chowdhury, O.; Bertino, E. 5GReasoner: A Property-Directed Security and Privacy Analysis Framework for 5G Cellular Network Protocol. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhan, W.; Chen, Q.; Yin, Y.; Sun, X. Modeling and Performance Analysis of 5G RRC Protocol with Machine-Type Communications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 33rd Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC), Kyoto, Japan, 09 2022; pp. 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanampudi, H.; Dhuli, R. Performance analysis of Heterogeneous Cloud-Radio Access Networks: A user-centric approach with network scalability. Computer Communications 2022, 194, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateen, A.; Zhu, Q.; Afsar, S.; Rashid, W. Optimization of Fog Computing Based Radio Access Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Software Engineering and New Technologies, New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauchs, M.; Glidden, A.; Gordon, B.; Pieters, G.C.; Recanatini, M.; Rostand, F.; Vagneur, K.; Zhang, B.Z. Distributed Ledger Technology Systems: A Conceptual Framework. SSRN 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhelezov, D. PoW, PoS and DAGs are NOT consensus protocols, 2018.

- Beyer, S. Proof-of-Work is not a Consensus Protocol: Understanding the Basics of Blockchain Consensus, 2019.

- Bains, P. Blockchain Consensus Mechanisms: A Primer For Supervisors. Technical report, International Monetary Fund, 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lou, W.; Hou, Y.T. A Survey of Distributed Consensus Protocols for Blockchain Networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22, 1432–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. An Overview of Blockchain Technology: Architecture, Consensus, and Future Trends. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Congress on Big Data (BigData Congress), 06 2017; pp. 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, X.; Dai, Y.; Maharjan, S.; Zhang, Y. Blockchain and Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserved Data Sharing in Industrial IoT. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2020, 16, 4177–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.J.M.; Ferdous, M.S.; Biswas, K.; Chowdhury, N.; Kayes, A.S.M.; Alazab, M.; Watters, P. A Comparative Analysis of Distributed Ledger Technology Platforms. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 167930–167943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, R.; Yaga, D.; Voas, J. Rethinking Distributed Ledger Technology. Computer 2019, 52, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussaoui, M.; Aryal, N.; Bertin, E.; Crespi, N. Distributed Ledger Technologies for Cellular Networks and Beyond 5G: a survey. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th Conference on Blockchain Research & Applications for Innovative Networks and Services (BRAINS), 09 2022; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, C.A.; Naranjo, S.S.; Toasa, V.J.; Yoo, S.G. A Systematic Literature Review of Blockchain Technology: Applications Fields, Platforms, and Consensus Protocols. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, B.; Musilek, P. A Comprehensive Review of Blockchain Consensus Mechanisms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43620–43652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamport, L. Generalized Consensus and Paxos. Microsoft Research Technical Report MSR-TR-2005-33.

- Bastiaan, M. Preventing the 51%-attack: a stochastic analysis of two phase proof of work in bitcoin (2015). In Proceedings of the Twente Student Conference on IT; 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sanda, O.; Pavlidis, M.; Seraj, S.; Polatidis, N. Long-Range attack detection on permissionless blockchains using Deep Learning. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 218, 119606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Hammad, E. 5G Security Challenges and Opportunities: A System Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 3rd 5G World Forum (5GWF); 2020; pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. An Overview of Network Slicing for 5G. IEEE Wireless Communications 2019, 26, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.A.; Nasimi, M.; Han, B.; Schotten, H.D. A Comprehensive Survey of RAN Architectures Toward 5G Mobile Communication System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 70371–70421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, C.K. Wireless ATM and Ad-Hoc Networks: Protocols and Architectures; Springer: New York, NY, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, H.; Jayasumana, A. Collaborative applications over peer-to-peer systems–challenges and solutions. Peer-to-Peer Network Applications. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.S.; Wismüller, R. Routing in Multi-Hop Cellular Device-to-Device (D2D) Networks: A Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 2018; 2622–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.K.; Verma, R.; Prakash, A.; Agrawal, A.; Naik, K.; Tripathi, R.; Alsabaan, M.; Khalifa, T.; Abdelkader, T.; Abogharaf, A. Machine-to-Machine (M2M) communications: A survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 2016; 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavat, S.; Sapavath, N.N.; Rawat, D.B. Recent advances in mobile edge computing and content caching. Digital Communications and Networks 2020, 6, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Dong, X.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, J. BC-RAN: Cloud radio access network enabled by blockchain for 5G. Computer Communications 2020, 162, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ling, X.; Le, Y.; Huang, Y.; You, X. Blockchain-enabled wireless communications: a new paradigm towards 6G. National Science Review 2021, 8, nwab069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.P.d.B.; de Resende, H.C.; Villaca, R.d.S.; Municio, E.; Both, C.B.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. Distributed network slicing management using blockchains in E-health environments. Mobile Networks and Applications 2021, 26, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, J.M.J.; Sánchez, P.M.S.; Lekidis, A.; Hidalgo, J.F.; Pérez, M.G.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Celdrán, A.H.; Pérez, G.M. Design of a Security and Trust Framework for 5G Multi-domain Scenarios. Journal of Network and Systems Management 2022, 30, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Ding, Z. Data Broker: Dynamic Multi-Hop Routing Protocol in Blockchain Radio Access Network. IEEE Communications Letters 2021, 25, 4000–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Iqbal, M.; Saxena, N. Future Industry Internet of Things with Zero-trust Security. Information Systems Frontiers 2022, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, V.; Manoharan, R.; Ramachandran, S.; Rajasekar, V. Blockchain Based Privacy Preserving Framework for Emerging 6G Wireless Communications. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 18, 4868–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, B.; Liu, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, L. Blockchain-based fog radio access networks: Architecture, key technologies, and challenges. Digital Communications and Networks 2022, 8, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B.K.; Saxena, V.; Barve, A.; Bhagat, A.K.; Devi, R.; Gupta, R. Evaluation of soft computing in intrusion detection for secure social Internet of Things based on collaborative edge computing. Soft Computing 2023, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Ling, X.; Wang, J.; Guo, R.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.X.; You, X. Resource Sharing and Trading of Blockchain Radio Access Networks: Architecture and Prototype Design. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 12025–12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liao, S.; Yin, Y.; Ni, R.; Zhang, Y. Radio optical network security analysis with routing in quantum computing for 5G wireless communication using blockchain machine learning model. Optical and Quantum Electronics 2023, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yan, J.; Chakraborty, C.; Sun, Y. Hedera: A Permissionless and Scalable Hybrid Blockchain Consensus Algorithm in Multiaccess Edge Computing for IoT. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 21187–21202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.Y.; Sergeev, A.; Zou, J. Securing Ethernet-based Optical Fronthaul for 5G Network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.Y.; Sergeev, A. Secure Open Fronthaul Interface for 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, D.; Berger, M.S. Transport Security Considerations for the Open-RAN Fronthaul. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th 5G World Forum (5GWF), Los Alamitos, US; 2021; pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.T.; Leu, F.Y. Detecting DoS and DDoS Attacks by Using CuSum Algorithm in 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Networked-Based Information Systems; Barolli, L., Li, K.F., Enokido, T., Takizawa, M., Eds.; Cham, 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benslimen, Y.; Sedjelmaci, H.; Manenti, A.C. Attacks and failures prediction framework for a collaborative 5G mobile network, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Iavich, M.; Gnatyuk, S.; Odarchenko, R.; Bocu, R.; Simonov, S. The Novel System of Attacks Detection in 5G. In Proceedings of the Advanced Information Networking and Applications; Barolli, L.; Woungang, I.; Enokido, T., Eds., Cham; 2021; pp. 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chatterjee, K.; Satapathy, S. An edge based hybrid intrusion detection framework for mobile edge computing. In Proceedings of the Complex & Intelligent Systems, Cham; 2021; pp. 3719–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaselvi, M.; Dhanaraj, R.K.; Sathya, M.; Memon, F.H.; Krishnasamy, L.; Dev, K.; Ziyue, W.; Qureshi, N.M.F. A highly secured intrusion detection system for IoT using EXPSO-STFA feature selection for LAANN to detect attacks. Cluster Computing 2023, 26, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, N.; Grijalva, S.; Chaudhari, N.S. Authentication Protocol for an IoT-Enabled LTE Network. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, A.; Borgaonkar, R.; Park, S.; Seifert, J.P. On the Impact of Rogue Base Stations in 4G/LTE Self Organizing Networks. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Security & Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec ’18. New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlosta, M.; Rupprecht, D.; Holz, T.; Pöpper, C. LTE Security Disabled: Misconfiguration in Commercial Networks. In Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec ’19. New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsikas, E.; Khandker, S.; Salous, A.; Ranganathan, A.; Piqueras Jover, R.; Pöpper, C. UE Security Reloaded: Developing a 5G Standalone User-Side Security Testing Framework. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, New York, NY, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Karakoc, B.; Fürste, N.; Rupprecht, D.; Kohls, K. Never Let Me Down Again: Bidding-Down Attacks and Mitigations in 5G and 4G. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec ’23. New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.J.; Fan, C.I.; Hsu, Y.C.; Karati, A. A Fast Authentication Scheme for Cross-Network-Slicing Based on Multiple Operators in 5G Environments. In Proceedings of the Security in Computing and Communications; Thampi, S.M., Wang, G., Rawat, D.B., Ko, R., Fan, C.I., Eds.; Singapore, 2021; pp. 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzogovic, B.; Mahmood, T.; Santos, B.; Feng, B.; Do, V.T.; Jacot, N.; Van Do, T. Advanced 5g network slicing isolation using enhanced vpn+ for healthcare verticals. In Proceedings of the Smart Objects and Technologies for Social Good: 7th EAI International Conference, GOODTECHS 2021, Proceedings 7, Cham, 2021. Virtual Event, September 15–17, 2021; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgaonkar, R.; Redon, K.; Seifert, J.P. Security Analysis of a Femtocell Device. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Security of Information and Networks, SIN ’11. New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tu, G.H.; Lei, X.; Xie, T.; Li, C.Y.; Chou, P.Y.; Hsieh, F.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Peng, C. Insecurity of Operational Cellular IoT Service: New Vulnerabilities, Attacks, and Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, New York, NY, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Rao, S.P. Adversarial trends in mobile communication systems: from attack patterns to potential defenses strategies. In Proceedings of the Secure IT Systems: 26th Nordic Conference, NordSec 2021, Virtual Event, 2021, Proceedings 26, Springer, Tampere, FI, 2021, November 29–30; pp. 153–171. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Qureshi, K.N.; Anwar, M.; Masud, F.; Imtiaz, J.; Jeon, G. Link-based penalized trust management scheme for preemptive measures to secure the edge-based internet of things networks. Wireless Networks 2022, 30, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamarthi, S.; Narmadha, R. Intelligent privacy preservation proctol in wireless MANET for IoT applications using hybrid crow search-harris hawks optimization. Wireless Networks 2022, 28, 2713–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekidis, A. Cyber-Security Measures for Protecting EPES Systems in the 5G Area. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, New York, NY, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, M.Y.; Tu, G.H.; Li, C.Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Xie, T.; Xiao, L.; Peng, C.; Tan, Z.; et al. Uncovering Insecure Designs of Cellular Emergency Services (911). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing And Networking, New York, NY, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Reshma, G.; Prasanna, B.; Murthy, H.; Murthy, T.; Parthiban, S.; Sangeetha, M. Privacy-aware access control (PAAC)-based biometric authentication protocol (Bap) for mobile edge computing environment. Soft Computing 2023, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, M.Y.; Tu, G.H.; Li, C.Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Xie, T.; Xiao, L.; Peng, C.; Tan, Z.; et al. Unveiling the Insecurity of Operational Cellular Emergency Services (911): Vulnerabilities, Attacks, and Countermeasures. GetMobile: Mobile Comp. and Comm. 2023, 27, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadares, D.; Will, N.; Sobrinho, Á.; Lima, A.; Morais, I.; Santos, D. Systematic Literature Review on 5G-IoT Security Aspects. Preprints 2023, 1, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Lin, Z. 2024; arXiv:cs.CY/2410.02156]. [CrossRef]

- Corporation, I. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2024, 2024.

- Landi, M. Global IT outage knocks airlines, banks and others offline, 2024.

- Sarah, A.; Nencioni, G.; Khan, M.M.I. Resource Allocation in Multi-access Edge Computing for 5G-and-beyond networks. Computer Networks 2023, 227, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.A.; Raza, H.W.; Alam, M.M.; Su’ud, M.M.; Sajak, A.b.A.B. Resource allocation schemes for 5G network: A systematic review. Sensors 2021, 21, 6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Z.; Chen, T.Y.H.; Su, P.J.; Liu, C.T. 2023; arXiv:cs.NI/2311.02311]. [CrossRef]

- Mimran, D.; Bitton, R.; Kfir, Y.; Klevansky, E.; Brodt, O.; Lehmann, H.; Elovici, Y.; Shabtai, A. Security of Open Radio Access Networks. Computers & Security 2022, 122, 102890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, J.; Shorov, A.; Abdelrazek, L.; Whitefield, J. Zero trust and 5G – Realizing zero trust in networks, 2021.

- Costlow, J. How Decryption of Network Traffic Can Improve Security, 2021.

- Wu, X.; Farooq, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J. LLM-xApp: A Large Language Model Empowered Radio Resource Management xApp for 5G O-RAN. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Networks and Distributed Systems Security (NDSS), Workshop on Security and Privacy of Next-Generation Networks (FutureG 2025), San Diego, CA; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Randewich, N. Musk’s bitcoin bet fuels gains in companies already invested, 2021.

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Zong, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, P. Resource Allocation Based on Radio Intelligence Controller for Open RAN Toward 6G. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 97909–97919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Khoa Nguyen, K. Joint Selection of Local Trainers and Resource Allocation for Federated Learning in Open RAN Intelligent Controllers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2022; pp. 1874–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaz, A.; Lipman, J.; Abolhasan, M.; Hiltunen, M. Toward Integrating Intelligence and Programmability in Open Radio Access Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 67747–67770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.S.; Upadhyaya, P.S.; Shah, V.K.; Marojevic, V. Toward Next Generation Open Radio Access Networks: What O-RAN Can and Cannot Do! IEEE Network 2022, 36, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldawlatly, A.; Alshehri, H.; Alqahtani, A.; Ahmad, A.; Al-Dammas, F.; Marzouk, A. Appearance of Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome as research question in the title of articles of three different anesthesia journals: A pilot study. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia 2018, 12, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.; Petrin, G. ITU World Radiocommunication Seminar highlights future communication technologies, 2010.

| Subject | Paper | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BC | BC-RAN: Cloud radio access network enabled by blockchain for 5G | [73] |

| Blockchain-enabled wireless communications: a new paradigm towards 6G | [74] | |

| Distributed Network Slicing Management Using Blockchains in E-Health Environments | [75] | |

| Design of a Security and Trust Framework for 5G Multi-domain Scenarios | [76] | |

| Data Broker: Dynamic Multi-Hop Routing Protocol in Blockchain Radio Access Network | [77] | |

| Future Industry Internet of Things with Zero-trust Security | [78] | |

| Blockchain Based Privacy Preserving Framework for Emerging 6G Wireless Communications | [79] | |

| Blockchain-based fog radio access networks: Architecture, key technologies, and challenges | [80] | |

| Evaluation of soft computing in intrusion detection for secure social Internet of Things based on collaborative edge computing |

[81] | |

| Resource Sharing and Trading of Blockchain Radio Access Networks: Architecture and Prototype Design | [82] | |

| Radio optical network security analysis with routing in quantum computing for 5G wireless communication using blockchain machine learning model |

[83] | |

| Hedera: A Permissionless and Scalable Hybrid Blockchain Consensus Algorithm in Multi-Access Edge Computing for IoT | [84] | |

| FH | Securing Ethernet-based optical fronthaul for 5G network | [85] |

| Secure Open Fronthaul Interface for 5G Networks | [86] | |

| Transport Security Considerations for the Open-RAN Fronthaul | [87] | |

| Open-RAN Fronthaul Transport Security Architecture and Implementation | [35] | |

| IDS/IPS | Detecting DoS and DDoS Attacks by Using CuSum Algorithm in 5G Networks | [88] |

| Attacks and failures prediction framework for a collaborative 5G mobile network | [89] | |

| The Novel System of Attacks Detection in 5G | [90] | |

| An edge based hybrid intrusion detection framework for mobile edge computing | [91] | |

| A highly secured IDS for IoT using EXPSO-STFA feature selection for LAANN to detect attacks | [92] | |

| RRC | Authentication Protocol for an IoT-Enabled LTE Network | [93] |

| On the Impact of Rogue Base Stations in 4G/LTE Self Organizing Networks | [94] | |

| LTE Security Disabled: Misconfiguration in Commercial Networks | [95] | |

| 5GReasoner: A Property-Directed Security and Privacy Analysis Framework for 5G Cellular Network Protocol | [46] | |

| AdaptOver: Adaptive Overshadowing Attacks in Cellular Networks | [31] | |

| UE Security Reloaded: Developing a 5G Standalone User-Side Security Testing Framework | [96] | |

| Never Let Me Down Again: Bidding-Down Attacks and Mitigations in 5G and 4G | [97] | |

| NS | A Fast Authentication Scheme for Cross-Network-Slicing Based on Multiple Operators in 5G Environments | [98] |

| Advanced 5G Network Slicing Isolation Using Enhanced VPN+ for Healthcare Verticals | [99] | |

| Others | Security Analysis of a Femtocell Device | [100] |

| Insecurity of Operational Cellular IoT Service: New Vulnerabilities, Attacks, and Countermeasures | [101] | |

| Adversarial Trends in Mobile Communication Systems: From Attack Patterns to Potential Defenses Strategies | [102] | |

| Link-based penalized trust management scheme for preemptive measures to secure the edge-based Internet of Things networks |

[103] | |

| Intelligent privacy preservation proctol in wireless MANET for IoT applications using hybrid crow search-harris hawks optimization |

[104] | |

| Cyber-Security Measures for Protecting EPES Systems in the 5G Area | [105] | |

| Uncovering Insecure Designs of Cellular Emergency Services (911) | [106] | |

| Privacy-aware access control (PAAC)-based biometric authentication protocol (Bap) for mobile edge computing environment |

[107] | |

| Unveiling the Insecurity of Operational Cellular Emergency Services (911): Vulnerabilities, Attacks, and Countermeasures |

[108] |

| Vulnerability Class | Vulnerability | Main papers | Other works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Codification/development | [102] | [94] |

| Cryptographic algorithms | [104] [79] | [92] [78] | |

| Lack of cryptography | [106] [108] | [101] [99] [77] [105] [78] [79] [100] [84] [85] [86] [104] [107] [95] |

|

| Communication | Communication problems | [103] | [97] [80] [105] [73] [91] [46] [106] [108] [74] [76] [79] [96] [83] [102] [94] [90] [35] |

| Lack or weakness of security mechanisms |

[85] [88] [90] [86] [87] [105] [35] [101] |

[93] [99] [77] [81] [80] [103] [82] [92] [89] [91] [31] [76] [96] [100] [102] |

|

| Operation | Outdated assets | [75] [76] [94] [95] | [100] [93] |

| Process | Access control | [100] [46] [89] [91] [92] [31] [80] [81] [82] [83] |

[97] [101] [105] [95] [78] [74] [76] [90] [85] [86] [107] [103] |

| Authentication | [93] [98] [99] [78] [107] [96] [97] [84] |

[105] [46] [95] [31] [106] [108] [79] [100] [102] [90] [87] [35] [104] [103] |

|

| Data storage | [73] [74] [77] | [97] [101] [105] [82] [89] [91] [46] [95] [31] [76] [79] [96] [102] [90] [93] [35] [107] [103] |

|

|

Main papers: Other works: |

Papers whose main vulnerability is as described Papers that study such vulnerability in addition to its main one |

||

| Security dimension | Main threat | Main papers | Other works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access control | Corruption or Modification of Information | [92] [80] [81] | [31] [100] |

| Destruction of Information or Other Resources | [100] [89] [91] [83] | — | |

| Disclosure of Information | [31] | [91] [46] [79] [107] | |

| Theft/Removal/Loss of Information or Other Resources | [46] [82] | — | |

| Authentication | Disclosure of Information | [98] [78] [97] | [93] |

| Theft/Removal/Loss of Information or Other Resources | [93] [84] | — | |

| Availability | Interruption of Services | [106] [108] [99] [96] | — |

| Communication security | Disclosure of Information | [101] | [85] [86] [87] [35] |

| Theft/Removal/Loss of Information or Other Resources | [85] [86] [87] [35] | [101] | |

| Data integrity | Corruption or Modification of Information | [73] [74] [77] | — |

| Destruction of Information or Other Resources | [104] [75] | — | |

| Non-repudiation | Corruption or Modification of Information | [76] | [105] [95] [90] [103] |

| Disclosure of Information | — | [105] [76] [102] [90] [103] | |

| Interruption of Services | [102] [103] [88] [90] [105] [94] | [76] | |

| Theft/Removal/Loss of Information or Other Resources | [95] | [102] | |

| Privacy | Disclosure of Information | [79] [107] | — |

|

Main papers: Other works: |

Papers whose main threat is as described Papers that study such threat in addition to its main one |

||

| Threat | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability | Interruption | Disclosure | Corrup./modif. | Destruction | Theft/rem./loss | Total |

| Communication | IDS/IPS: 2 Others: 2 |

Others: 1 | Fronthaul: 4 | 9 | ||

| Process | RRC: 1 Slicing: 1 |

Blockchain: 1 RRC: 2 Slicing: 1 Others: 1 |

Blockchain: 5 IDS/IPS: 1 |

Blockchain: 1 IDS/IPS: 2 Others: 1 |

Blockchain: 2 RRC: 2 |

21 |

| Code | Others: 3 | Blockchain: 1 | Others: 1 | 5 | ||

| Operation | RRC: 1 | Blockchain: 1 | Blockchain: 1 | RRC: 1 | 4 | |

| Total | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 39 |

|

Interruption: Disclosure: Corrup./modif.: Destruction: Theft/rem./loss: |

Interruption of Services Disclosure of Information Corruption or Modification of Information Destruction of Information or Other Resources Theft, Removal, or Loss of Information or Other Resources |

|||||

| Paper | UE | Air | RU | FH | DU | MH | CU | BH | NS | DN | MEC | Paper | UE | Air | RU | FH | DU | MH | CU | BH | NS | DN | MEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [100] | X | X | [99] | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [93] | X | X | [78] | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| [94] | X | X | X | [103] | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [95] | X | [104] | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| [85] | X | [92] | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| [46] | X | X | [79] | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| [88] | X | X | [105] | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [73] | X | X | [31] | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [89] | X | [106] | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| [98] | X | [80] | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| [74] | X | X | X | X | [107] | X | |||||||||||||||||

| [90] | X | X | [108] | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| [75] | X | [35] | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| [86] | X | [81] | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [91] | X | [96] | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| [101] | X | [97] | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [76] | X | X | X | [82] | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [87] | X | [83] | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| [102] | X | X | [84] | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| [77] | X | Total | 20 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 7 |

| Attack class | Attack | Papers | # papers |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Network unavailability (NU) |

DoS/DDoS | [87] [31] [105] [106] [108] [35] [79] [81] [91] [92] [89] [99] [102] [103] [88] [90] [107] [75] [78] [83] [46] [85] [94] |

23 |

| Flooding/signaling | [80] [76] [92] [99] [102] [46] [94] | 7 | |

|

Data corruption (DC) |

MitM | [87] [86] [96] [31] [101] [35] [79] [82] [74] [104] [88] [90] [98] [46] [85] [93] | 16 |

| False data injection | [87] [86] [105] [35] [74] [81] [89] [102] [88] [107] [100] [46] [93] | 13 | |

| Replay | [87] [105] [35] [79] [98] [93] | 6 | |

| Insider | [73] [91] | 2 | |

| Spamming | [101] | 1 | |

|

Unauthorized access (UA) |

Backdoor | [81] [91] [92] [90] [107] [85] | 6 |

| Hijacking | [106] [84] [81] [89] [88] [94] | 6 | |

| Sybil | [79] [77] [84] [76] [104] [83] | 6 | |

| Tampering | [105] [73] [80] [82] [74] [103] | 6 | |

| Malware spreading | [105] [91] [103] [88] | 4 | |

| User-to-root | [91] [103] | 2 | |

|

Data leakage (DL) |

Eavesdropping | [87] [86] [97] [35] [82] [74] [76] [102] [46] [85] | 10 |

| Impersonation/spoofing | [87] [35] [76] [95] [100] [93] [31] [104] [102] [103] | 10 | |

| Identity theft | [31] [76] [92] [102] [107] [78] [100] [93] | 8 | |

| Sniffing | [86] [73] [91] [103] [90] [85] | 6 | |

| Cryptanalytic | [79] [81] [104] | 3 | |

| Quantum | [86] [85] | 2 | |

| Phishing | [88] | 1 | |

| Wormhole | [83] | 1 | |

|

Physical resource spoliation (PR) |

Jamming | [31] [105] [102] [103] [83] | 5 |

| Rogue BTS | [96] [31] [97] [94] | 4 | |

| Bidding-down | [97] [90] | 2 | |

| Physical damage | [83] [100] | 2 | |

| Signal overshadowing | [96] [31] | 2 | |

| Resource exhaustion | [89] | 1 |

| Class | Vulnerabilities | Threats | Security dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| NU | Access control Lack/weakness |

Disclosure Interruption |

Non-repudiation Access control Availability |

| DC | Access control Lack/weakness Authentication Data storage |

Disclosure Interruption |

Non-repudiation Comm. security |

| UA | Access control Lack/weakness Comm. problems Data storage |

Disclosure Interruption Corrup./modif. |

Non-repudiation Access control |

| DL | Access control Data storage |

Disclosure Interruption |

Non-repudiation Access control |

| PR | Access control Data storage Authentication Lack/weakness |

Disclosure Interruption |

Non-repudiation Access control |

| Lack/weakness: | Lack or weakness of security mechanisms | ||

| Attack classes |

Total of papers |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | NU | DC | UA | DL | PR | |

| Blockchain | 7 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Fronthaul | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| IDS/IPS | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| RRC | 3 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Slicing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Others | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| Solution class | Purpose | Proposed solution | Paper (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach/Mechanism | Detect/Mitigate | Prevention mechanism against bidding-down attacks | [97] (2023) |

| Suite of solution approaches | [101] (2021) | ||

| Mitigate | Isolation of healthcare vertical slicing approach | [99] (2022) | |

| Blockchain-ledger safeguard mechanism | [77] (2021) | ||

| Blockchain to secure the NS management layer in private networks | [75] (2021) | ||

| Architecture | Detect | Blockchain network IDS architecture | [81] (2023) |

| Detect/Mitigate | Blockchain-based Fog-RAN | [80] (2022) | |

| Cyber-security measures applied to a power plant to detect/mitigate unwanted actions | [105] (2022) | ||

| Mitigate | Blockchain-unified architecture for resource sharing and trading | [82] (2023) | |

| Blockchain-enabled architecture | [73] (2020) | ||

| Framework | Detect | Intrusion detection framework for IoT | [92] (2022) |

| Several security prediction agents framework | [89] (2021) | ||

| Intrusion detection framework for MEC | [91] (2021) | ||

| Framework for verification of the control-plane | [46] (2019) | ||

| Security testing framework | [95] (2019) | ||

| Detect/Mitigate | Security testing framework | [31] (2022) | |

| Suite of standard-compliant solutions | [106] (2022) | ||

| Suite of standard-compliant solutions | [108] (2023) | ||

| Mitigate | Blockchain zero-trust framework for IoT | [78] (2022) | |

| Trustworthy and secure Blockchain paradigm for 6G networking | [74] (2021) | ||

| Blockchain security and trust framework | [76] (2021) | ||

| Privacy preserving Blockchain framework | [79] (2022) | ||

| Planning | Security testing framework | [96] (2023) | |

| Methodology/Method | Detect | Security analysis methodology | [100] (2011) |

| Blockchain method for analysing radio optical networks | [83] (2023) | ||

| Adversarial trends analysis methodology | [102] (2021) | ||

| Detect/Mitigate | Security analysis methodology | [94] (2018) | |

| Model/Algorithm | Detect | Attack detection algorithm | [90] (2021) |

| Detect/Mitigate | Security algorithm to detect and mitigate DoS/DDoS attacks | [88] (2020) | |

| Mitigate | Permissionless, scalable Blockchain consensus algorithm | [84] (2023) | |

| Protocol | Mitigate | Authentication protocol for the IoT-enabled LTE network | [93] (2016) |

| WireGuard security protocol | [85] (2019) | ||

| MACSec security protocol | [86] (2021) | ||

| MACSec security protocol | [87] (2021) | ||

| MACSec security protocol | [35] (2023) | ||

| IoT security protocol in MANET | [104] (2022) | ||

| Authentication protocol for MEC | [107] (2023) | ||

| Scheme | Detect/Mitigate | Trust-based routing scheme | [103] (2022) |

| Mitigate | Authentication scheme for slicing | [98] (2021) |

| Threat | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability | Interruption | Disclosure | Corrup./modif. | Destruction | Theft/rem./loss | Total |

| Communication | D/M: 3 Detect: 1 |

D/M: 1 | Mitigate: 4 | 9 | ||

| Process | Mitigate: 1 Planning: 1 |

D/M: 2 Mitigate: 3 |

Detect: 2 D/M: 1 Mitigate: 3 |

Detect: 4 | Detect: 1 Mitigate: 3 |

21 |

| Code | Detect: 1 D/M: 2 |

Mitigate: 1 | Mitigate: 1 | 5 | ||

| Operation | D/M: 1 | Mitigate: 1 | Mitigate: 1 | Detect: 1 | 4 | |

| Total | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 39 |

| D/M: | Detect/Mitigate | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).