1. Introduction

In the mathematical theory of linear programming (LP) models, established by Dantzig [

1], the coefficients of the objective function, of the constraint matrix and of the right-hand sides of the constraints are assumed to be constant when uncertainty does not affect the description of a phenomenon. However, uncertainty is unavoidable when a real phenomenon is the object of interest and one of the possibilities if to replace constant coefficients with intervals of possible values (on the basis of seminal Moore’s book [

2]); on this way, the area of interest becomes ILP (interval linear programming) allowing the modelling of several possible scenarios and the description of the best and worst cases (as it is explained in [

3] also in the case of the inverse problem).

In this paper we compare the objective solutions in the ILP by adopting the comparison index introduced in [

4] and [

5] that is based on the generalized Hukuhara difference for intervals; in the two mentioned papers we show that the index summarizes the order relations proposed and analyzed by Ishibuchi and Tanaka in [

6] where they consider the coefficients in mathematical programming problems as intervals and introduce five order relations for ranking two intervals. We provide evidence of the superiority of the comparison index in terms of errors and of worst case loss in many optimization models. The same index has also been tested in the research of the average rate of return for investment appraisal in uncertain conditions (see [

7]).

A rich literature is devoted to ILP, here we summarize some crucial contributions. Optimization problems in which the coefficients of the objective function and the constraints are interval numbers have been investigated in a seminal paper by Tong in [

8]: the interval of the solution is deduced by taking the maximum value range and minimum value range inequalities as constraint conditions. Sengupta and Pal, in [

9], studied the same problem and proposed the concept of the acceptability index; see also reference [

10], an extended presentation of many contributions around the main theme.

A unified scenario for optimal solutions is introduced in [

11] where necessary and sufficient criteria for testing a class of optimality are developed according to the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions.

Hladik in [

12] presents conditions for necessary efficiency in interval multiobjective linear programming and in [

13] he studies robustness of optimal solutions in terms of their capability to stay optimal when perturbations occur; Alolyan investigates interval constraints in [

14].

In [

15] an ensemble framework for assessing solutions of interval programming problems is developed when interval dominance rules are defined and their correlations are described via exclusion, inclusion and equivalence.

The optimal solution set of ILP is deduce as the intersection of regions arising from best and worst scenarios in [

16]; in [

17], a review of some methods for solving ILP (Interval Linear Programming) models with inequality constraints is presented; in [

18] some existing methods for solving interval linear programming problems are described when the model is transformed into two submodels and improvements about them are studied. In [

19] an algorithm useful for large-scale problems is introduced and it is based on the construction of an interval linear equations system that is the union of linear equations coming from the binding constraint indices of the optimal solution.

In [

20], a nonlinear interval programming problem is studied when coefficients are uncertain and the key methodology adopted to solve it is to convert the interval single-objective problem into a two-objective problem, which considers both of the average value and the robustness of the design.

An extended overview of the different approaches reported in the literature to deal with uncertainty in multiple objective linear models through interval programming can be found in [

21] and the research of efficient solutions is focused in [

22] with evidence on some practical financial aspects.

A new method for solving fully fuzzy linear programming problems with inequality constraints and parameterized fuzzy numbers, by means of solving multiobjective linear programming problems, is presented in [

23]. Previously, Arana-Jiménez in [

24] proposes an algorithm, that does not use ranking functions, to find the fuzzy optimal (nondominated) solutions of fully fuzzy linear programming problems with inequality constraints, with triangular fuzzy numbers and not necessarily symmetric, via solving a multiobjective linear problem with crisp numbers.

A unique optimal solution for linear programming problem is obtained in [

25] through a lexicographic ranking-based solution methodology.

Finally, a general study for studying interval optimization problems is developed in [

26].

The paper is organized as follows: after the introduction, in the second section we recall the main properties about the way to compare interval numbers. Section three is devoted to the introduction of linear programming solutions when costs are modelled through interval numbers. Numerical examples and sensitivity analysis are collected in section four and section five closes the paper.

2. Interval Numbers Comparison

An order relation for the ranking of interval numbers has been introduced in [

4] and then it has been detailed in [

5]. Basically we need the following notation:

an interval

with

has a midpoint-radius representation

that is defined by the following values

where

and such that:

Canonical operations are defined in both notations:

and if

is a scalar then:

We need also the generalized Hukuhara difference (detailed in [

27]) that is defined as

in order to define the index for interval numbers comparison:

Definition 1.

Given two distinct intervals , the gH-comparison index (of order 2) is defined as

where is the gH-difference,

is the midpoint value and

is the Hausdorff distance.

A comparison index ratio can be defined when

as:

and the relationship between the two indexes is:

where the sign + holds when

and − when

.

The index satisfies some properties as the invariance of scale and the invariance to interval translation.

In [

5] we also show how it is possible to extend the definition of a comparison index to fuzzy intervals.

When comparing overlapping intervals and if the choice is based on the midpoint values and then two kinds of risk arise and they can be focused as follows:

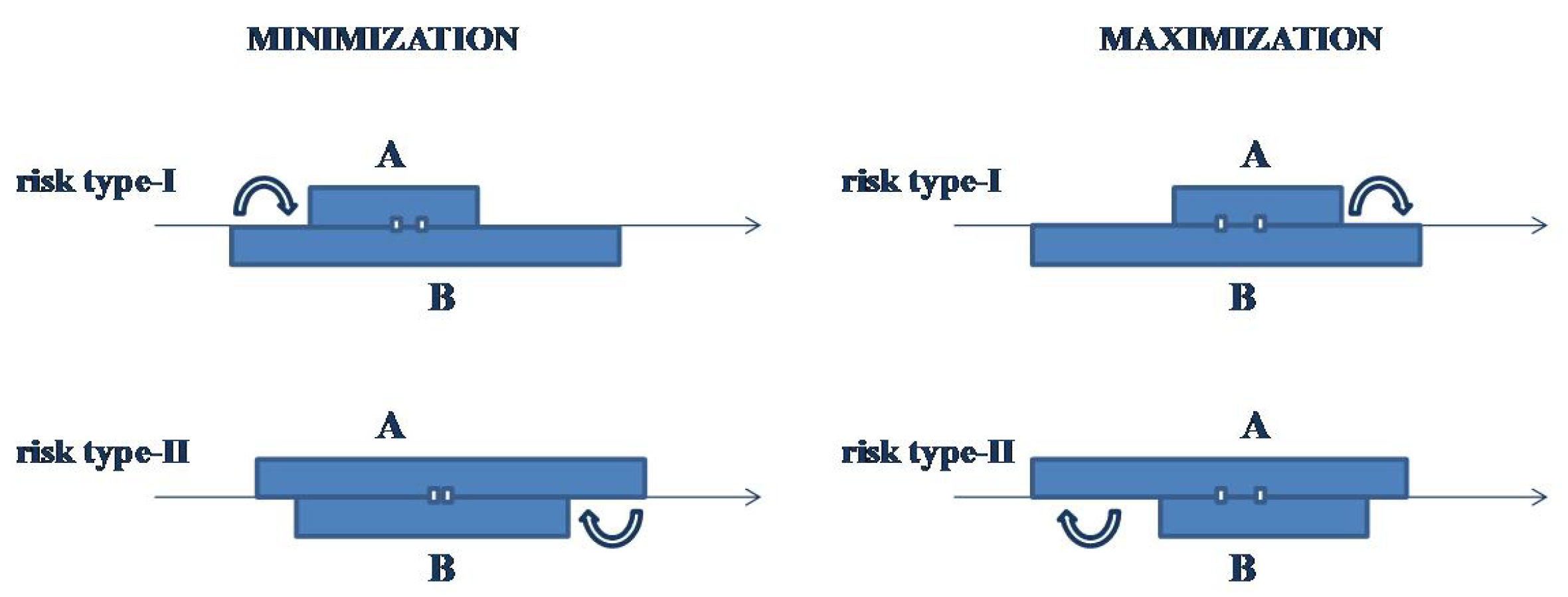

Definition 2. A type I risk is defined to be the possible worst-case loss when, comparing A and we choose A but there exist elements in B which are better than all elements of A.

Definition 3.

A type II risk is defined to be the possible worst-case loss when, comparing A and we choose B but there exist elements in A which are worst than all elements of B.

Figure 1.

The type-I and type-II risks may occur in minimization and maximization problems.

Figure 1.

The type-I and type-II risks may occur in minimization and maximization problems.

The defined value

enables the definition of a "risk" measure that is detailed in [

5] and that we recall as follows:

in a case of a minimization problem, we have a preliminary preference for A against B if (for the moment ) because the difference represents the mid-point gain if we choose A. On the other hand, taking into account the uncertainties given by and , two possible bad situations may arise

(i) , i.e. , and this means that there exist values such that for all ;

(ii) , i.e. , and this means that there exist values such that for all .

In case (i) the positive quantity measures the possible regret, relative to the midpoint gain;

in case (ii) a measure of the possible regret is given by the positive quantity .

In terms of the the comparison index ratio , then, the relative regret measure is positive if or if and the regret measures increases if increases far from the threshold 1 (case (i)) or decreases far from the threshold (case (ii)).

In the presence of worst case loss for the two types of risk, the value can be limited by two fixed values and such that and a new order relation can be introduced:

Definition 4.

Given two intervals and and , we define the following (strict) order relation, denoted ,

It is immediate to see that the relation

with

,

is antisymmetric and transitive; furthermore, there are specific values of

and

which make the order relation (

12) equivalent to the most cited order relations in literature known with the acronyms

as it is shown in the following definition.

Definition 5. and

Let A and B be two intervals with and then it holds that

1)

2)

3)

4)

5) .

By varying the two parameters , , we obtain a continuum of strict (partial) order relations for interval. The set of real intervals with the order relation defined by or ) with is a complete lattice

Consequently, the decision making midpoint representation can be defined as follows:

Definition 6.

with

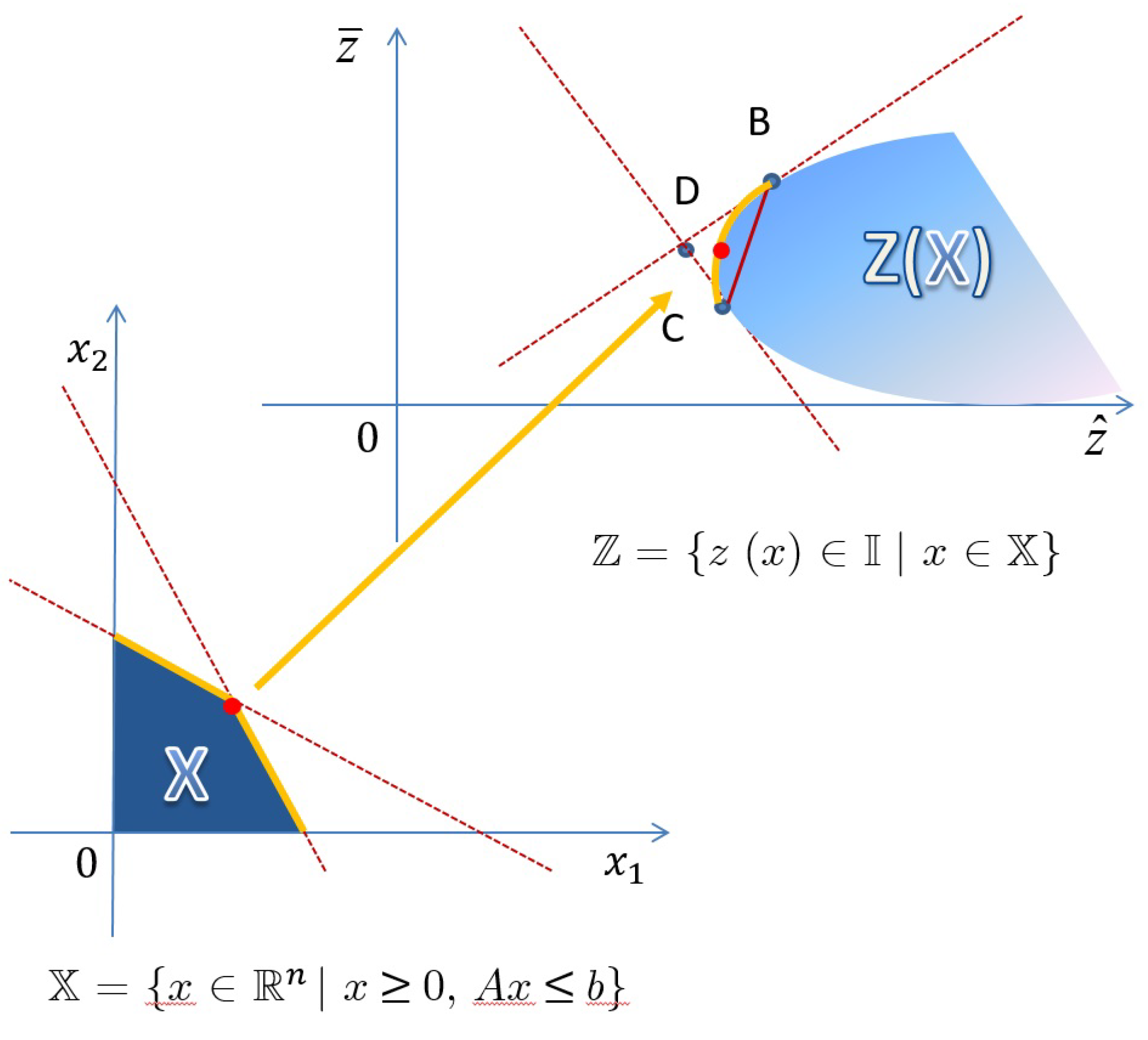

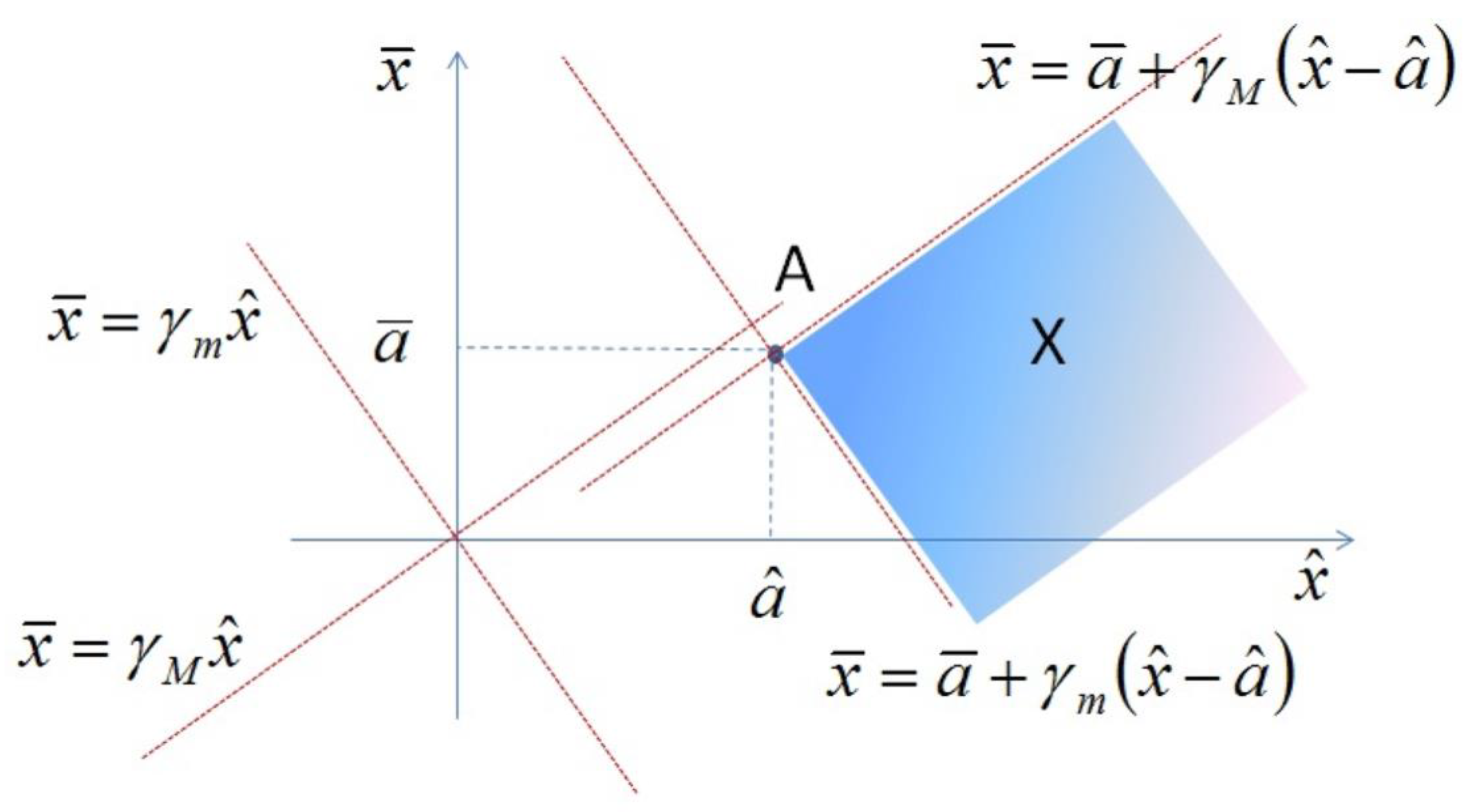

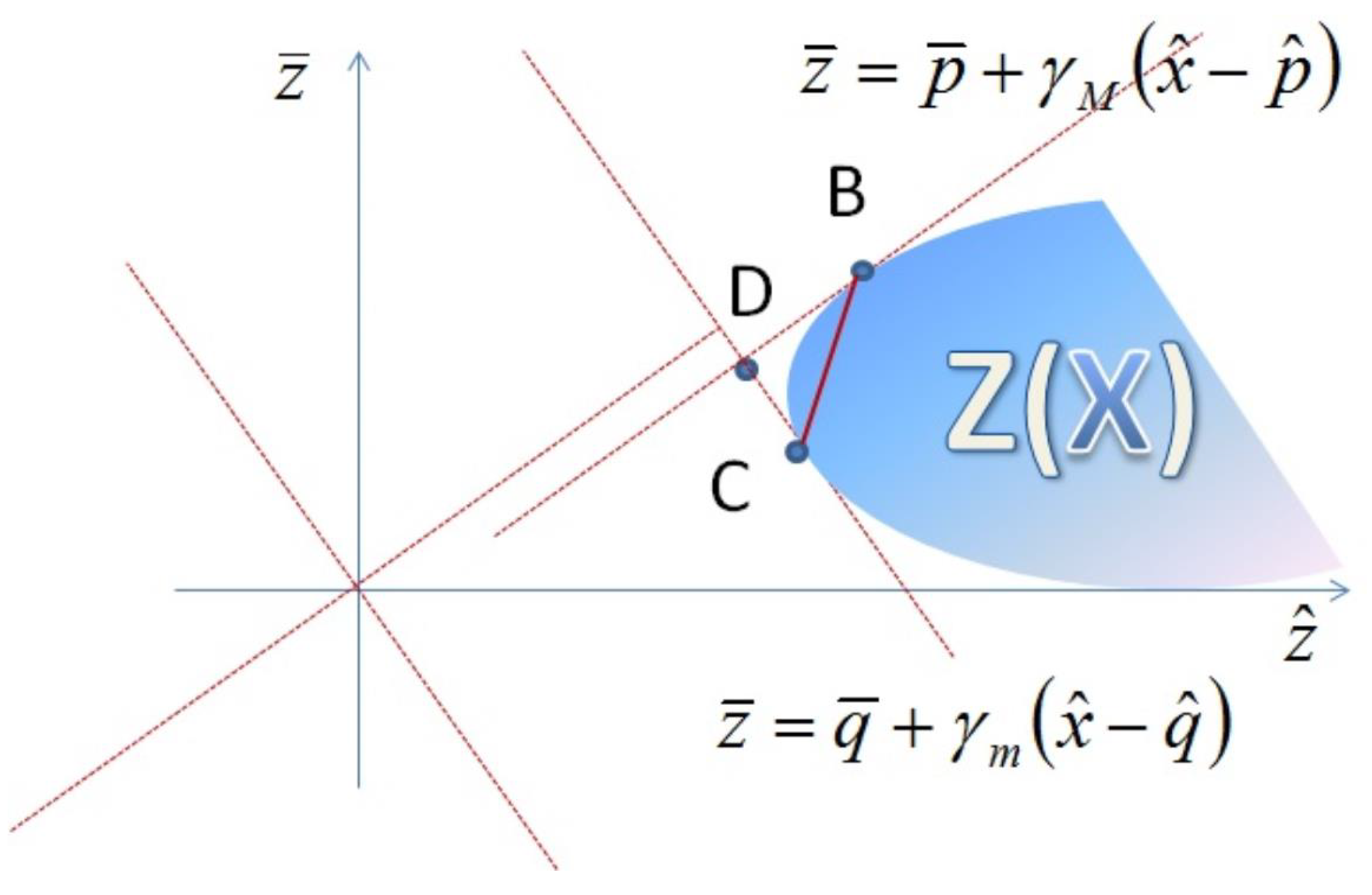

Figure 2.

Visualization of the set of intervals

Figure 2.

Visualization of the set of intervals

For a given interval

, consider the set of intervals

Proposition 7. For any real and (the slopes of the tangent lines) and any intervals , we have

1. if and only if , and

2. if and only if .

Given a family

of intervals (for any finite or infinite index set

) the infimum and the supremum operators with respect to partial order

, respectively

and

, are defined by the two intervals (in mid-point notation)

and

where

are

and

are

Remark 8.

To focus on the interest for an interval ordering index, we mention that the acceptability index for inequality , introduced by Sengupta and Pal (see [9,10]) and defined by (assuming )

is successfully used to convert an interval inequality , with into a "crisp equivalent" form as follows

where is an assumed fixed (optimistic) threshold; substituting the expression for we obtain

This set of inequalities, being , implies that and does not imply a control on the possible worse case losses. In fact we can see that is not equivalent to in the sense that the one can not be transformed into the other.

The comparison index can be applied when a variable interval of the form

is compared with a fixed interval

B;.two possible worst case losses may occur and they are related to the value of

. Supposing

it follows that the value of

for the inequality

is:

In order to control the extent of the possible worst case loss for the two types of risk, we can require that the value be controlled for the type I risk and/or for the type II risk. To do this, we fix two values and and we require that valid values of x satisfy and

The two types of risk are eliminated when and The values and , if negative, give the relative worst case loss with respect to .

In terms of (

12), we can write:

If we are minimizing and we do not accept a risk of type II, we may require that

(we eventually accept only a risk of type I) and we choose

,

; a risk of type II represents the possibility that we realize values in

that are greater than all values in

B. Similarly, if we do not accept a risk of type I, then we choose

,

; a risk of type I represents the possibility that we realize values in

B that are less than all values in

. If

and

no risk of the two types is accepted. It follows that the use of the acceptability index does not avoid the two types of risk that are controlled using the order relationship (

12).

3. Interval Costs in Linear Programming

We apply the order relation

to linear programming with interval costs (ILP problem) that has the following general form:

where

A is a matrix with

m rows and

n columns,

b is

m-vector of right-hand side terms,

,

are

n intervals representing the coefficients of the linear objective function

to be minimized that is represented by an interval

where

and

are given by

Figure 3.

Visualization of the process from the feasible convex set to the feasible objective intervals

Figure 3.

Visualization of the process from the feasible convex set to the feasible objective intervals

An optimal solution

is computed with the corresponding objective value:

where

x is in the feasible convex set:

and the set of feasible objective intervals is again a convex set:

Remark 9. It is well known that is a convex polygon in and this implies that is a convex polygon in the space of intervals.

Definition 10. If are two feasible solutions and are the corresponding objective interval values then dominates (or in other words dominates if and only if

The search of a solution requires the following method: among all the feasible objective values, the not dominated values, with respect to the interval relation order (with fixed , ) have to be selected . In particular, given two feasible solutions and with the corresponding objective intervals given by: and the problem is to chose the best interval between them. Three possible situations may occur:

Given two feasible solutions and with the corresponding objective intervals given by: and the best interval between them corresponds to three cases:

is better than (dominates) or equivalently

is better than (dominates) or equivalently

and are not comparable because of the incomparability between and

Consequently, a solution

x is called efficient if there is no feasible solution

such that

dominates

x. It follows that, as it is shown in

Figure 2, the tangent lines to

determine the ideal objective interval that has values between the tangent points called

and

The main interpretation of the expression is that:

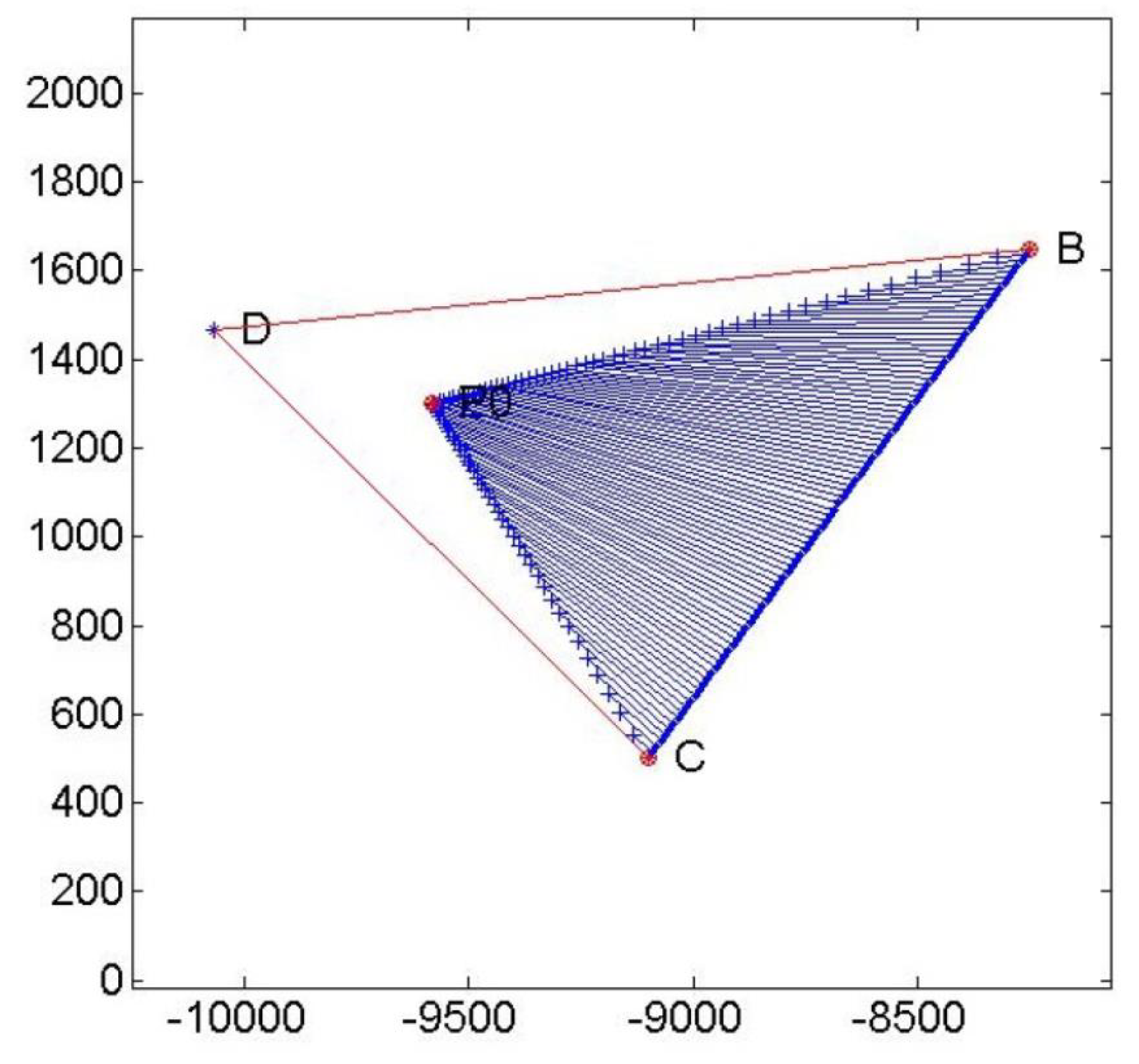

Figure 4.

Representation of tangent lines to

Figure 4.

Representation of tangent lines to

The DBC triangle construction provides two important information :

the efficient boundary of the LP problem, in the target value space , is inside the triangle DBC;

-

value D identifies the ideal objective solution, it is unique in , but not necessarily in and this implies

Greatest Lower Bounded respect to

if then D is unique and is the ideal solution

The efficient frontier is determined by two "tangent" lines or better "support lines":

1) where P is feasible,

and with such that is the largest.

2) where Q is feasible,

and with such that is the smallest.

The intersection between tangent lines is the ideal solution

It follows that:

A solution x is efficient if there is no feasible solution such that dominates x.

Tangent lines ( support lines ) to determine the ideal objective interval that has values between the tangent points called and

The interval valued LP optimal solution is

4. Numerical Examples and Sensitivity Analysis

We now apply the mentioned results to some linear programming problems with interval costs and we extend preliminary results shown in [

28]. An exahustive scenario of properties concerning calculus of interval-valued functions can be found in [

29,

30].

Example 1. The first example is specified with the following data:

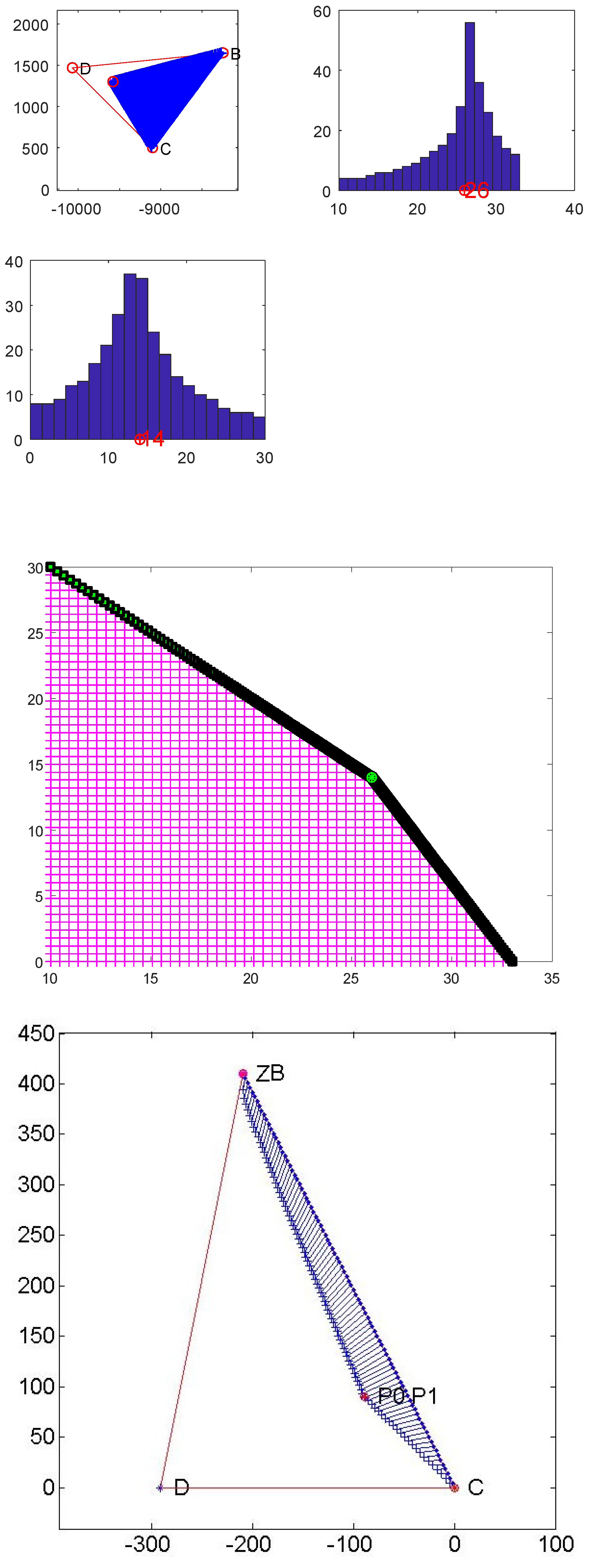

Figure 4 shows the two red tangent lines and the third red line connecting the tangent points. The area described by blue lines is the feasible set,

D is

in () that does not belong to the feasible set and it requires the mentioned goal programming technique to identify the minimum value

as

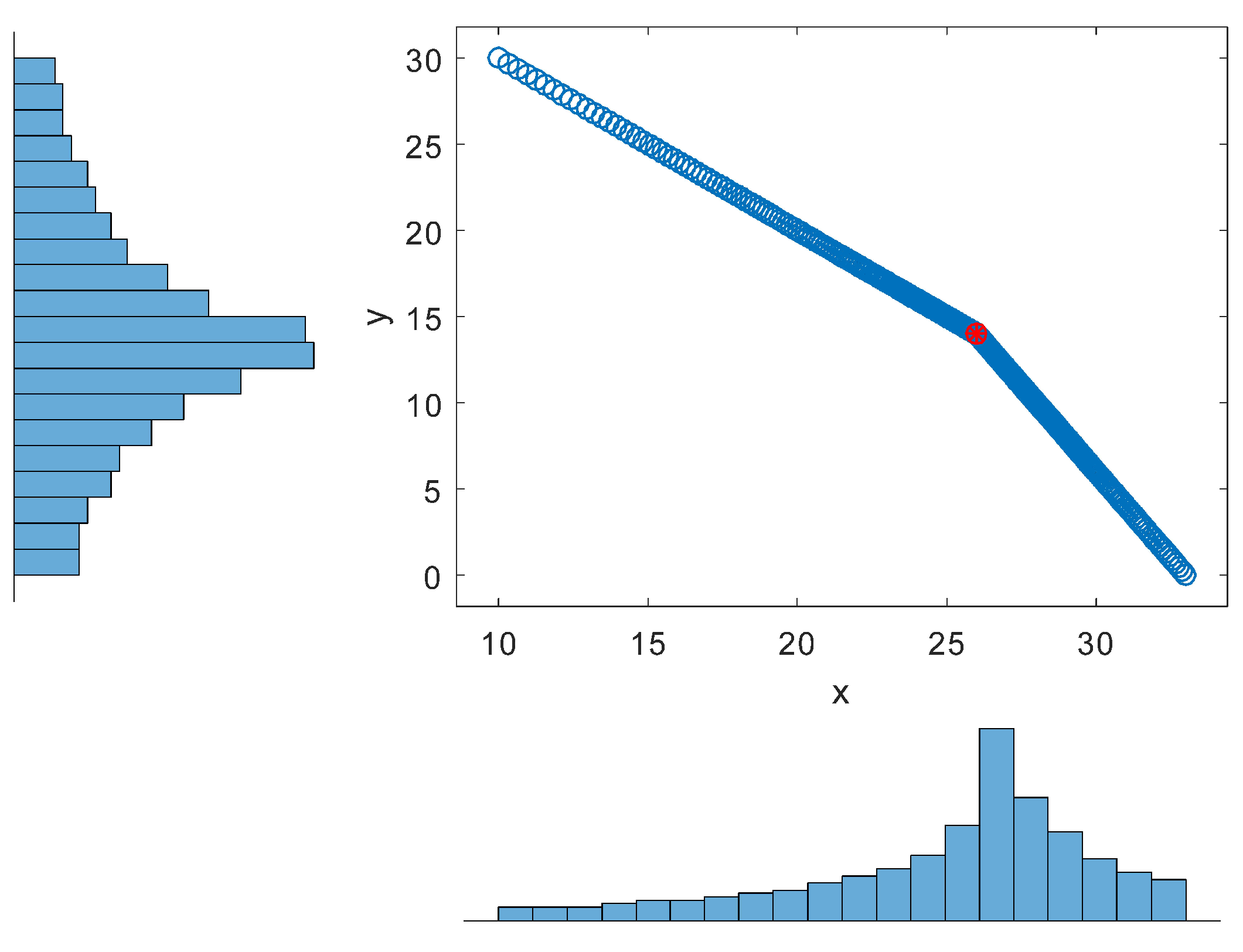

The sensitivity analysis for the optimal solution is carried out through a scatter plot where values of the two variables and and their frequencies are shown in order to observe the robustness of the solution. The vertical and horizontal histograms show the distribution of the values of and around the optimal solution.

Example 2. The second example comes from [

31] where the optimization problem is described as follows (

):

Figure 5.

Ideal and optimal solution of example 1 are shown

Figure 5.

Ideal and optimal solution of example 1 are shown

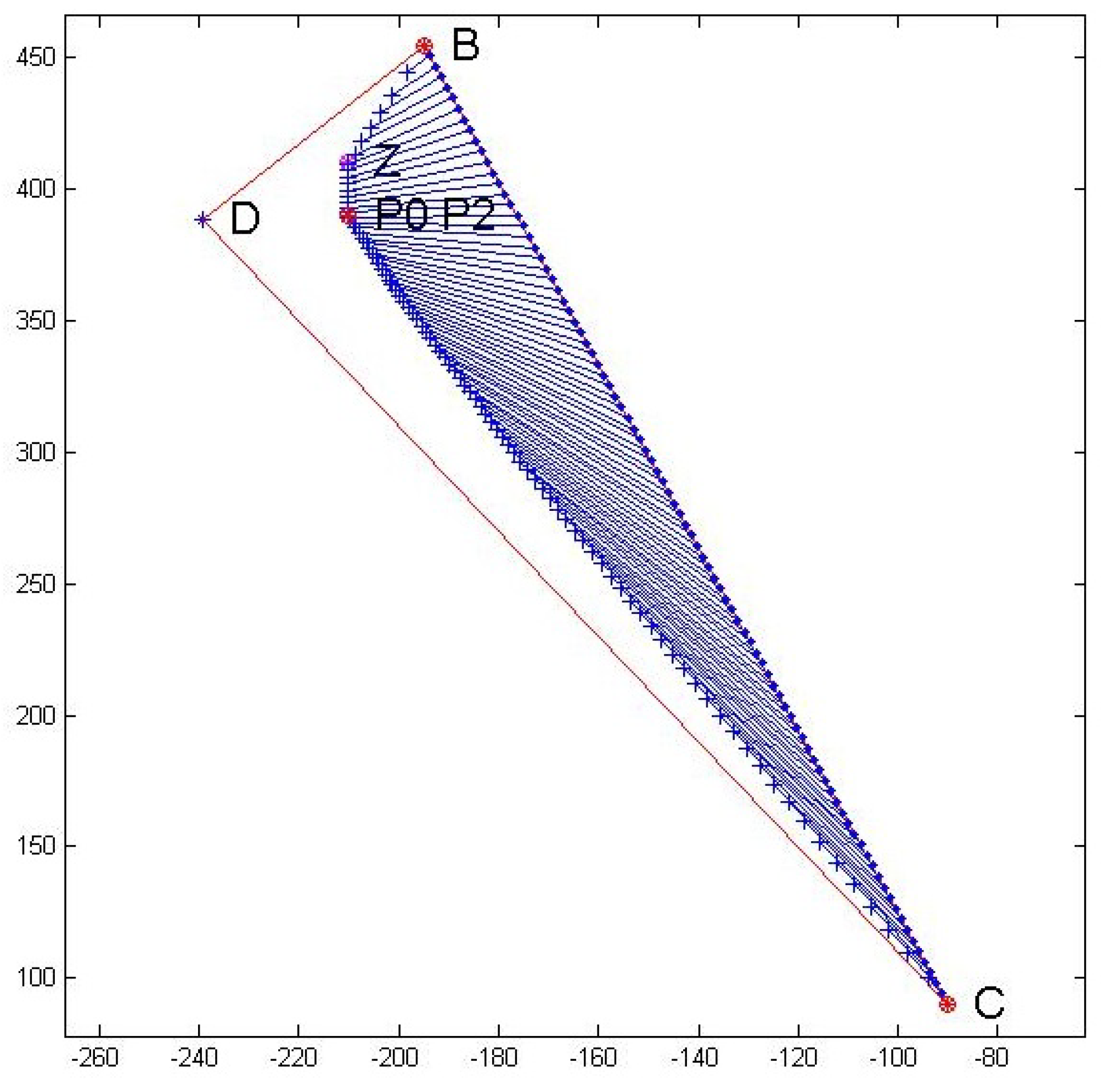

We have solved the problem in the minimization form so that the midpoint values of the objective function are negative.

Figure 2 shows the minimum value

obtained with the slope of tangent lines specified as follows:

and

. The point

is the minimum obtained in [

31] and it is the same a the one obtained by our method (as the nearest interval to the ideal solution

corresponding to the chosen values of

and

. The second solution suggested by Chanas and Kuchta is

, obtained by our method with the partial order generated by

and

and represented in

Figure 3.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis for example 1

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis for example 1

Example 3. The third numerical example is a problem called ITPMPF (Interval-valued Transportation Problem with Multiple Penalty Factors) that comes from chapter 7 of the book [

10] and it is defined as:

where

We chose

and

In

Figure 3,

is the minimum obtained with our methodology,

and

are the minima obtained with the reduction into a standard LPP structure as in [

10] and

is the solution of the same problem obtained in [

32]. We remark that the solutions

,

and

are not on the efficient frontier of the feasible objective values.

The figure shows that is the closest to the ideal minimum stressing the goodness of our methodology.

A further example is the same as in papers [

15,

18]; they consider a numerical interval linear programming example as follows:

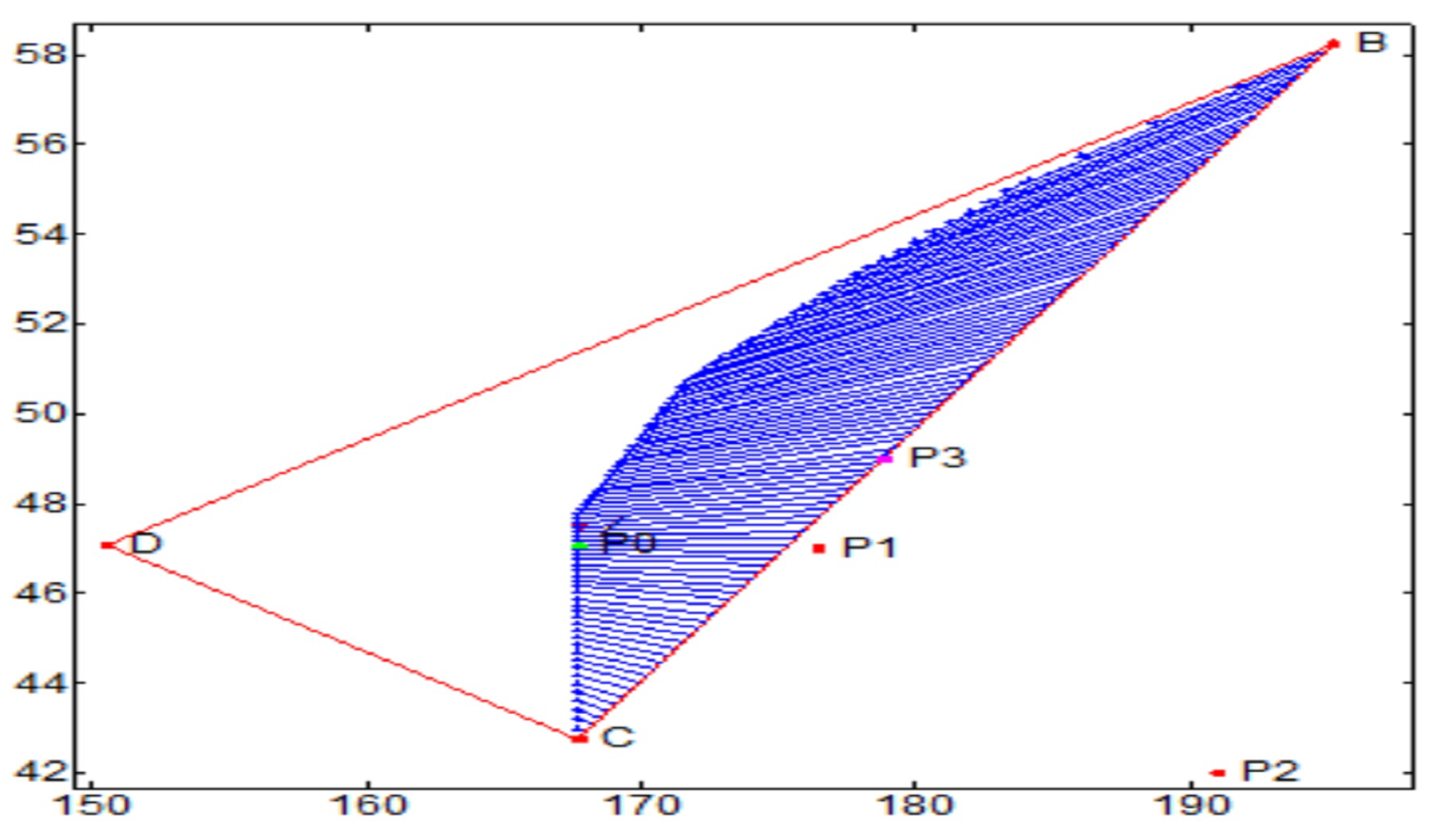

Figure 7.

Numerical example n.2 (Chanas and Kuchta) with = 0, = 5.0

Figure 7.

Numerical example n.2 (Chanas and Kuchta) with = 0, = 5.0

Figure 8.

Numerical example n.2 (Chanas and Kuchta) with = −2, = 1.5

Figure 8.

Numerical example n.2 (Chanas and Kuchta) with = −2, = 1.5

Figure 9.

Numerical example 3. (Sengupta and Pal)

Figure 9.

Numerical example 3. (Sengupta and Pal)