Submitted:

26 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“Also, among all the localities of contemporary Chennai, it is the one that has that old-world charm the most…Mylapore has a certain architecture to it, and that is vanishing today because of construction of newer buildings.”Nanditha Krishna, historian and environmentalist

“What is more than 200 years old here? Most of the old structures have been redone and the actual ones don’t exist anymore. Mylapore temple gopuram was done in 1900 and so was the pond. Of course, they are named in Devaram of the 8th century, but the structures mentioned in it don’t exist anymore.”Venkatesh Ramakrishnan, historian and novelist

Claim and Argument Structure

2. Theoretical Framework: Vulnerability and Transformation of Urban Heritage Precincts

Theorising Urban Built Heritage: ‘Urban Artefacts’ and ‘Urban Performative Complex’

“I would define the concept of type as something that is permanent and complex, a logical principle that is prior to form and that constitutes it.”Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City 1966, p. 40.

3. Methodology and Empirical Evidence from Kapaleeshwara Temple precincts

Reading Morphological Transformations

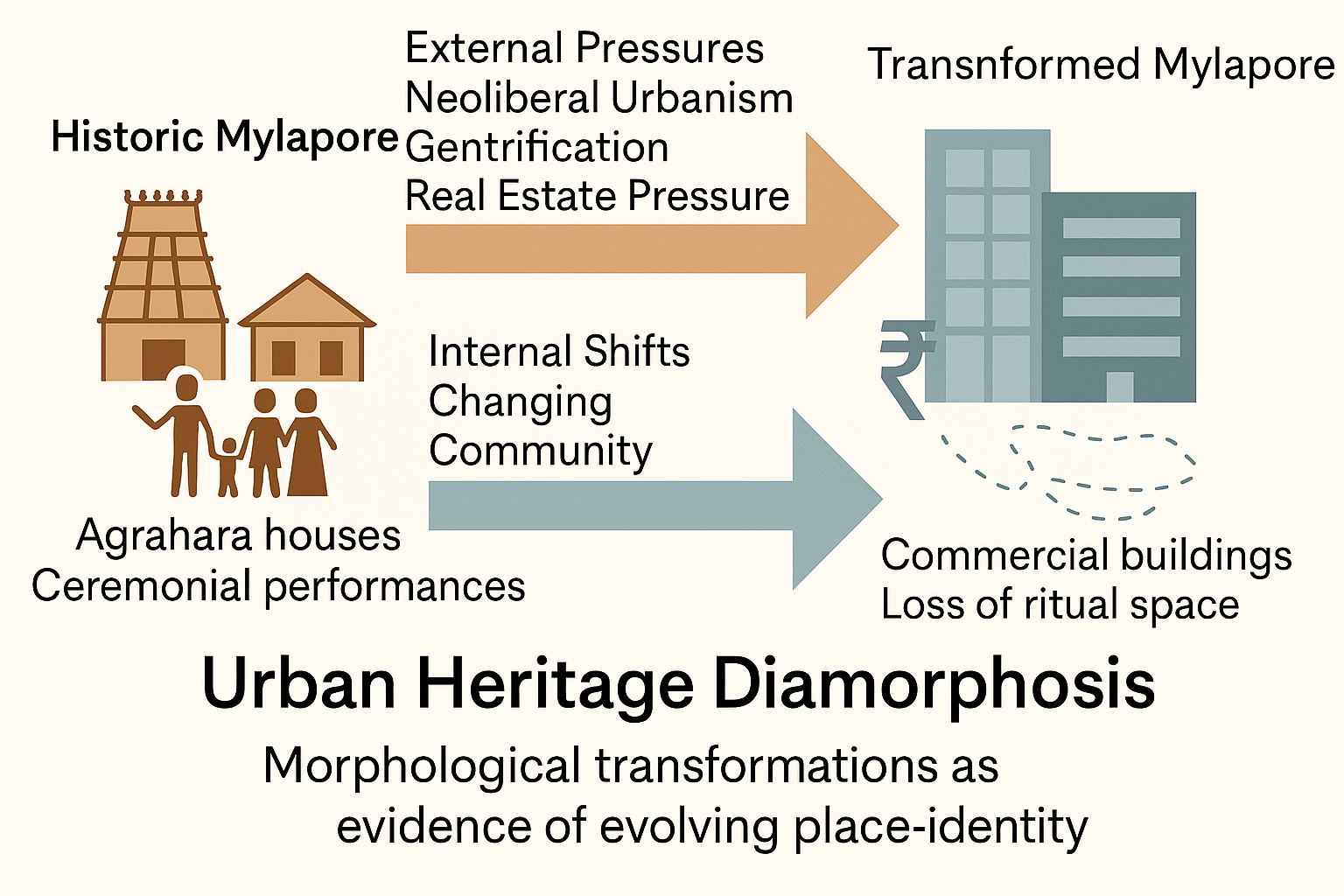

4. Urban Heritage Diamorphosis: A Conceptual Exploration

References

- Aranha, P., 2011. From Meliapor to Mylapore, 1662-1749: The Portuguese presence in São Tomé between the Quṭb Shāhī conquest and its incorporation in British Madras. In: Portuguese and Luso-Asian Legacies in Southeast Asia: The Making of the Luso Asian World: Intricacies of Engagement. Vol. 1, pp. 67-82. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N., Marcuse, P. and Mayer, M., eds., 2012. Cities for people, not for profit: Critical urban theory and the right to the city. London: Routledge.

- Court, S. and Wijesuriya, G., 2015. People-centred approaches to the conservation of cultural heritage: Living heritage. Rome: ICCROM.

- Harini, S. and Kitchley, J.L., 2021. Social sustainability in a culturally sound but disrupted urban fabric: The case of Mylapore. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Special Issue on STAAUH, (November), pp.193-208.

- Harvey, D., 1989. The condition of postmodernity: An enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Oxford: Blackwell.

- oseph, A.I., Suganth, M. & Sharanya, C.R., 2016. Mylapore, a UNESCO cultural heritage site?. Times of India. Available online: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/54427242.cms?

- Maassen, A. and Galvin, M., 2019. What does urban transformation look like? Findings from a global prize competition. Sustainability, 11(17), p. 4653. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H., 1996. Writings on Cities. Edited by E. Kofman and E. Lebas. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Prasad, D., 1994. The traditional settlement of Mylapore. Architecture + Design, Gurgaon, India, pp. 24-25.

- Rittel, H.W.J. and Webber, M.M., 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), pp.155-169. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A., 1982. The architecture of the city. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Smith, L., 2006. Uses of heritage. London: Routledge.

- Srinivas, S., 2001. Landscapes of urban memory: The sacred and the civic in India’s high-tech city. NED—New edition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Vincent, D.S., 2017. Mylapore: Succumbing to real estate pressure, needs preservation. Retrieved July 10, 2021. Available online: http://www.epaper.newindianexpress.com.

- Weise, K., 2013. Discourse. In: K. Weise, ed. Revisiting Kathmandu: Safeguarding Living Urban Heritage. Kathmandu: UNESCO Kathmandu Office, pp. 1–52. Available online: https://publik.tuwien.ac.at/files/publik_229747.pdf.

- Zukin, S., 1995. The cultures of cities. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

| Traditional Urban Public Life | Socio-Spatial Dimensions of Transformation |

|---|---|

| The tradition of "Veedhi Bhajans," or on-street devotional music processions, has been a musical heritage for centuries, occurring during the holy month of Margazhi from December to January. These processions take place at dawn, with hymns from sacred scriptures creating a spiritual experience. Bhajan mandalis like Haridasa Giri, Paapanasa Shivan, and Gnanananda Mandali participate, singing devotional hymns while circumambulating the Kapaleeshwara Temple. Passersby often join in, and performances usually conclude in front of the temple, followed by breakfast at a local devotee's home. | Residents draw kolams in front of their houses to honor the musicians. Traditional houses featured porticos or platforms for resting during the bhajans. The Agraharam's concentric road network defines the bhajans' procession path. Community participation has shifted over the years; while locals once warmly welcomed participants, today's backdrop sometimes features closed shops and deserted streets. The bhajans, traditionally encircling the temple, now extend to neighbouring communities, inviting broader participation. |

| The Palkudam, or Milk Pot Festival, is a one-day celebration during Chitirai Pournami in Mylapore, Chennai, involving hundreds of women carrying pots of milk in a vibrant procession to the Mundaga Kanni Temple for abhisheka, a sacred bathing ritual believed to heal diseases. | During the festival, streets are adorned with neem leaves, flowers, and other natural items, symbolizing the deity's healing qualities. A total of 101 pots, each smeared with turmeric and filled with milk, are offered to the goddess Mundaga Kanni after a neighbourhood procession. The Palkudam festival highlights the local community's active participation in preserving and celebrating their heritage. |

| During February, Mylapore hosts the vibrant tradition of Samudra Snanam (Shore Processions). Accompanied by musical instruments and Vedic chants, deities are taken from their temples to the sea for immersion, a significant religious event typically lasting one or two days. | Festivities include erecting pandals at the temples and the seashore. Processions start at various temples, winding through neighbourhoods before reaching the sea, symbolizing the historical link between the temples and the sea. Residents welcome the deity with flowers along the way. The redevelopment of Marina Beach lacks dedicated facilities to accommodate these large gatherings. |

| In Mylapore, the Shivaratri celebrations are a one-night festival that has a unique temporal character, lasting for a single night but filled with vibrant activities. | During Shivaratri, pandals are erected near the seven Sapta Shiva temples, creating a festive atmosphere. Temple roads are adorned with lights to guide devotees. Pandals are built ten days prior, with road corners becoming workshops for bamboo crafts. Devotees undertake a symbolic pilgrimage, visiting all seven temples on foot. Cultural programs are held in playgrounds and open spaces, forming territorial zones near temples, as people stay awake to enjoy performances. Recently, celebrations have moved to auditoriums, and traditional routes connecting the temples have changed. |

|

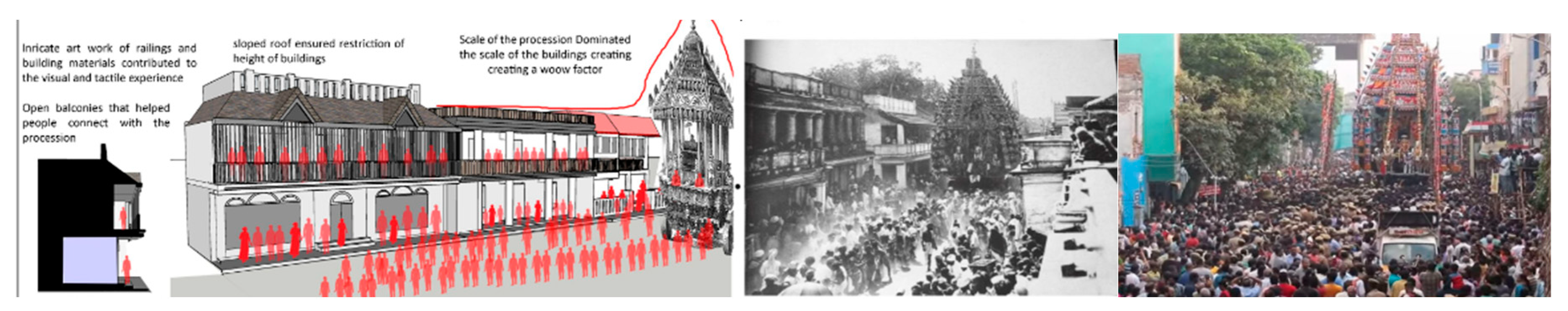

Brahmotsavam, or the Panguni Festival, is a 10-day celebration in March at the Kapaleeswara Temple precincts, with the Ther temple car festival as its highlight on the 7th day. During the Ther, a tall, ornate temple car is paraded through the four mada streets. Devotees eagerly await the first glimpse of the deity on the chariot, considered very auspicious. The procession includes sounds of conches, instruments, drums, and cymbals, with devotees pulling the chariot using large ropes. It pauses at key locations like the temple tank and Velleeswarar Temple for spiritual enactments, drawing massive crowds (Thinamani Deepavali Malar). The Arubathimoovar Festival on the 8th day features a grand procession of palanquins bearing the 63 Nayanmars, revered Tamil Shaivite saints. The procession includes active participation from local residents who carry the palanquins. The route is lined with shops offering food and beverages, including buttermilk, to the devotees. |

The tall temple car contrasts with surrounding low-rise buildings, with balconies and front yards becoming vantage points. Residents along the Mada Streets host relatives to watch the procession, showering water and flowers on participants. Temporary pandals and shops create a bustling atmosphere, with maps of the procession route marking pause points and food distribution areas. Traffic restrictions ensure attendee safety. However, streets along the route have transformed into tall commercial buildings, obstructing views, especially on north Mada Street. Overcrowding has disrupted the peaceful flow and led to the discontinuation of story enactments, musical concerts, and cultural elements. Changing building typology has eliminated front yards for viewing, and the participation of elephants and horses, once significant, has been halted due to excessive crowds. |

| Karthigai Deepam, celebrated in December, is a four-day festival marking Lord Kartikeya's birthday. On the first day, known as Karthigai Deepam, residents light up to 10,000 deepas along the temple tank's edge for four days, creating a mesmerizing spectacle. | As the festival unfolds, temporal changes occur around the temple and tank. Tables are set up, and hundreds of volunteers arrange the deepas (oil lamps). The low-height walls around the temple tank offer convenient access for devotees to view the rituals. The full moon night transforms the temple tank bed into a breathtaking sight, with the glow of the lamps casting a radiant aura. The temple tank has a rich history as an ancient rainwater harvesting method, providing a vital resource for Agrahara residents. |

| The Teppa Utsava, or Temple Tank Festival, is held in January. The sacred idol is processed around the temple before being set afloat in the temple tank on a specially crafted boat that can accommodate up to 100 people. On the first day, there is an oorvalam (procession) of the Kapaleeswarar deity, followed by processions of Lord Murugar with Deivanai and Valli on the next two days. A highlight of the festival is the illuminated raft casting its glow on the water, accompanied by Vedic chants from the mantapa at the tank's center, creating a mystical experience. | In preparation, large drums are brought to the temple, and a raft is constructed. The five mantapas around the tank are decorated, and the tank's edges are adorned with bright lights. However, the festival faces challenges: temporary shops encroach on one side of the tank, reducing visibility from nearby roads. Restricted access to the tank area limits participation, and the poorly maintained tank edge further hinders visibility. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).