Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

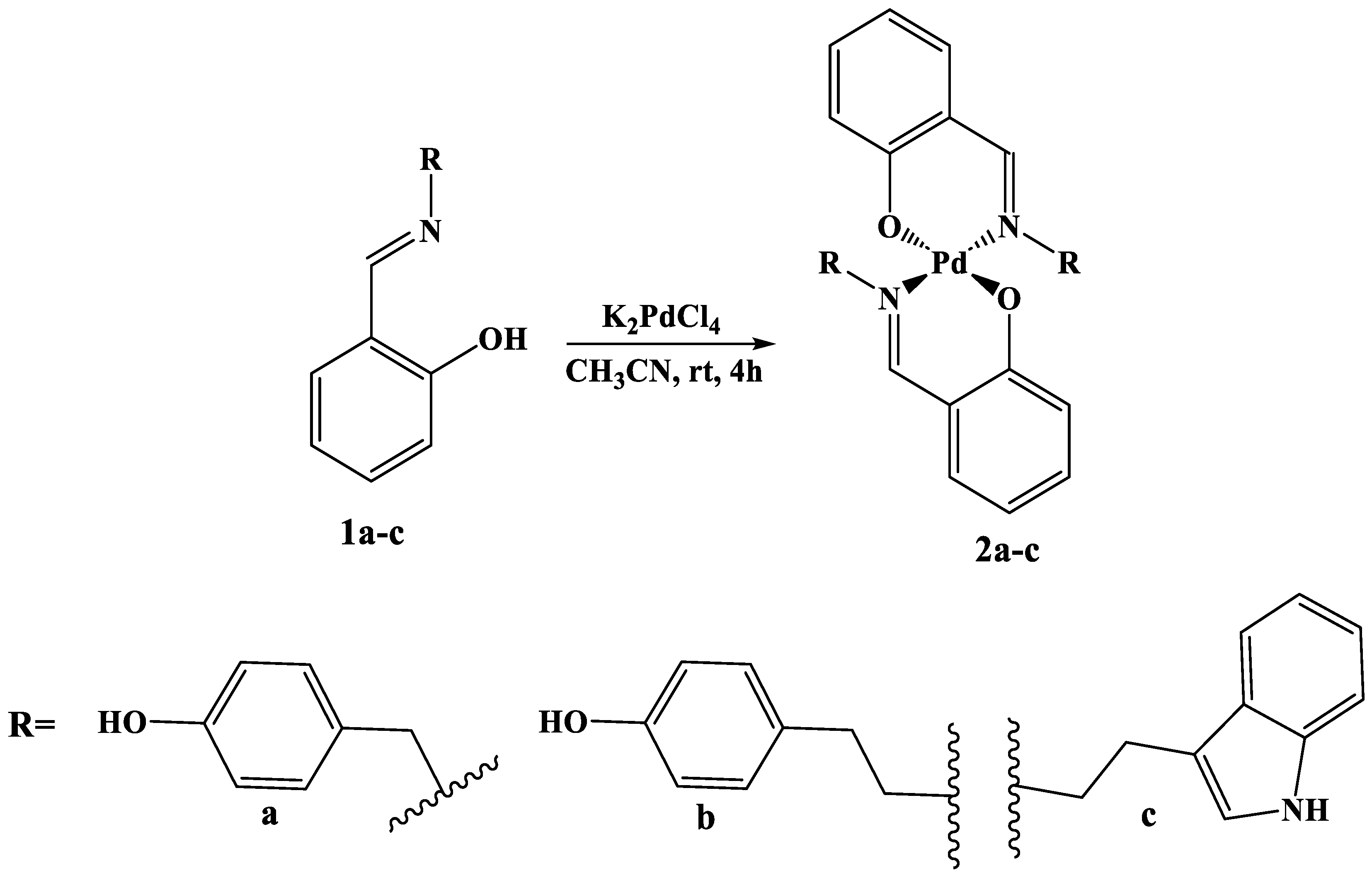

2.1. Synthesis of Pd Complexes 2a-c

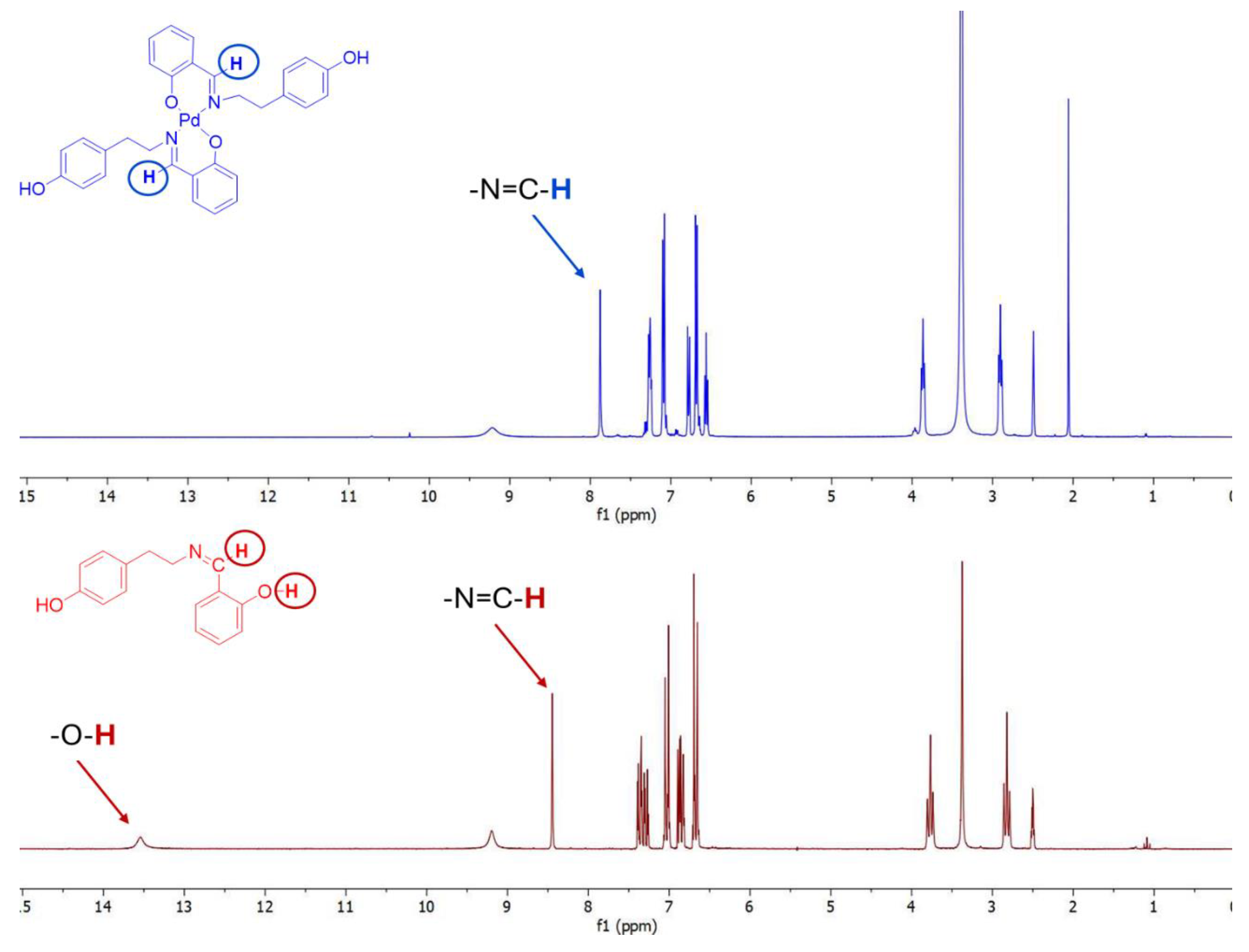

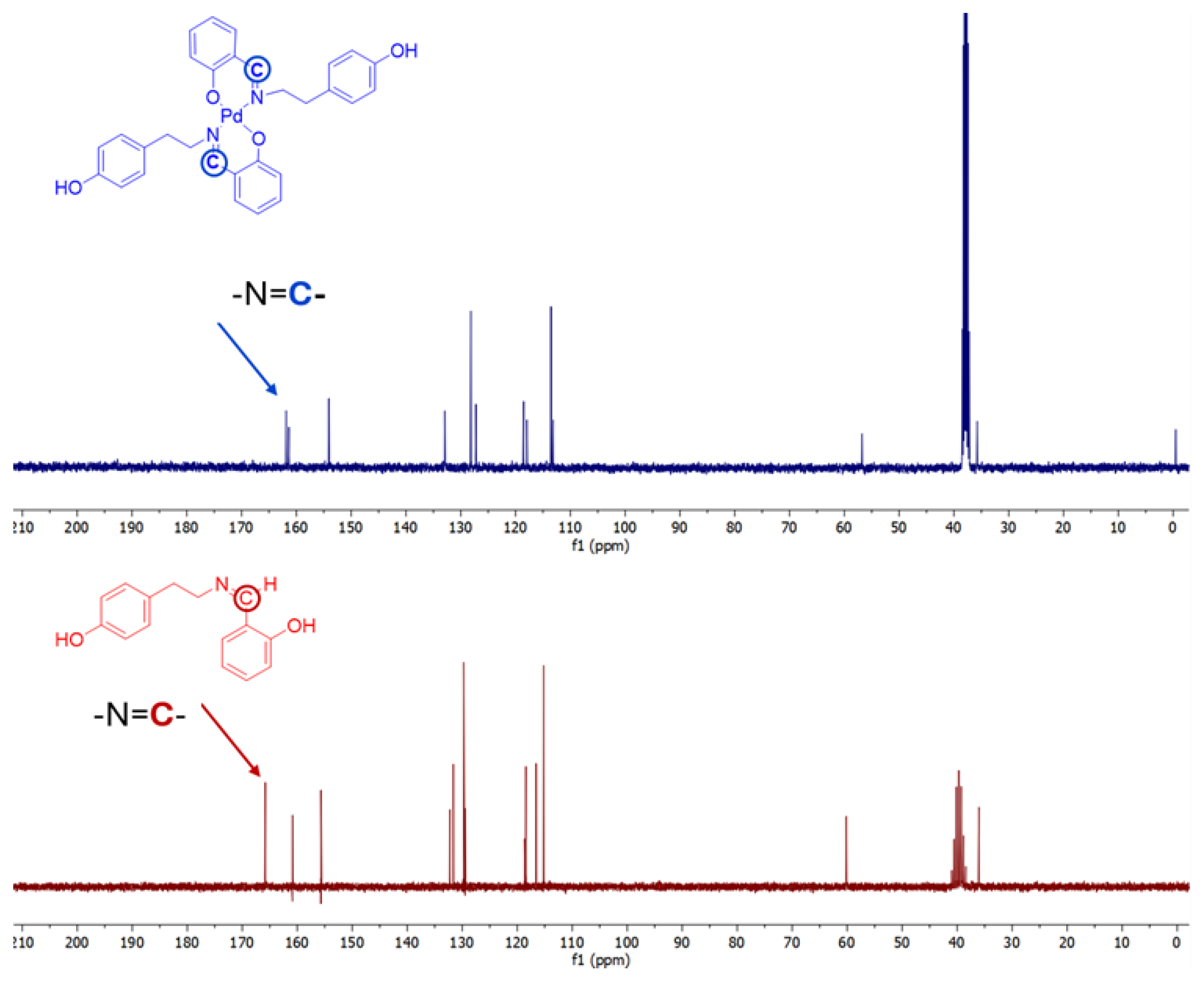

2.2. NMR Studies

2.3. IR Analysis

2.3. Mass Analysis

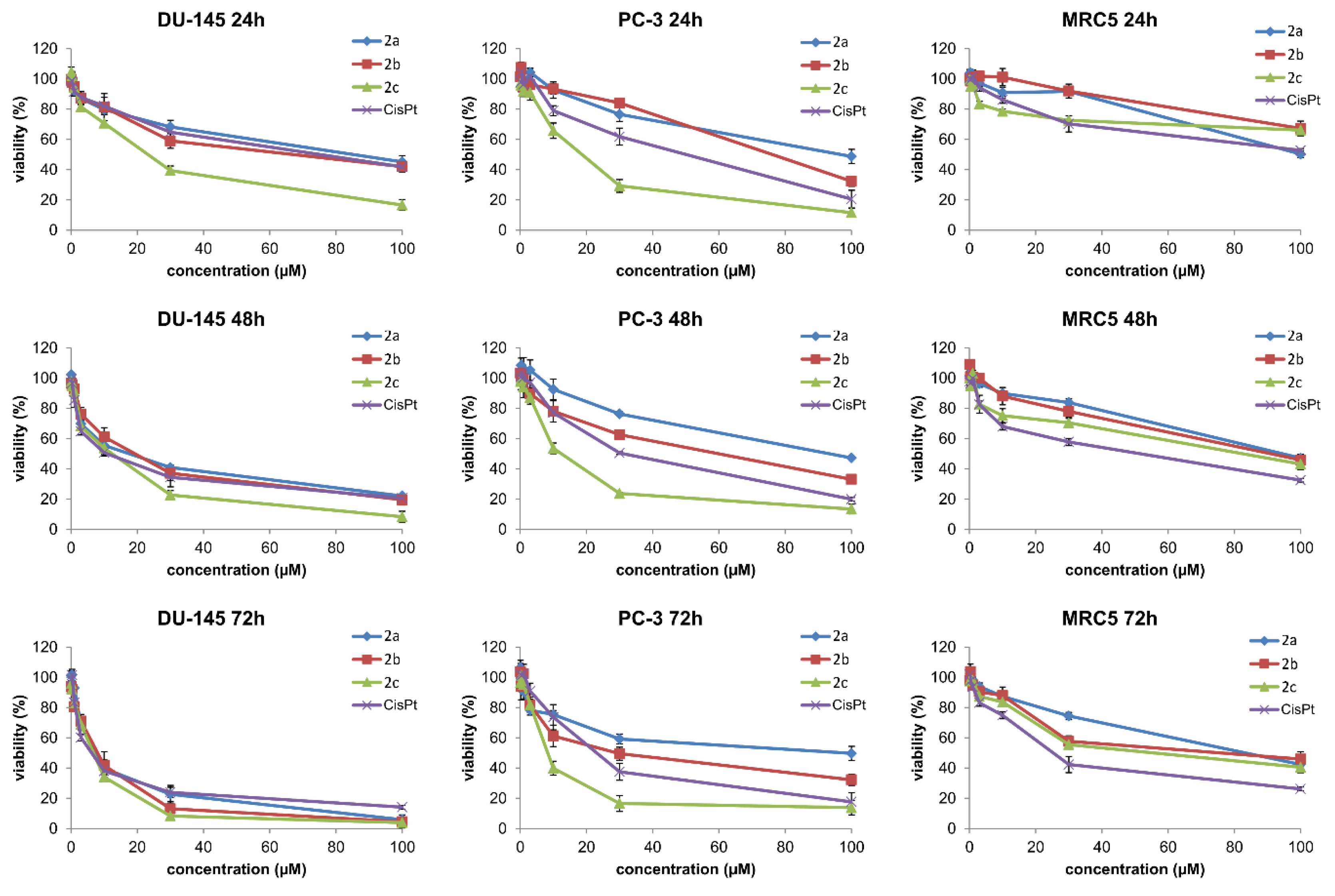

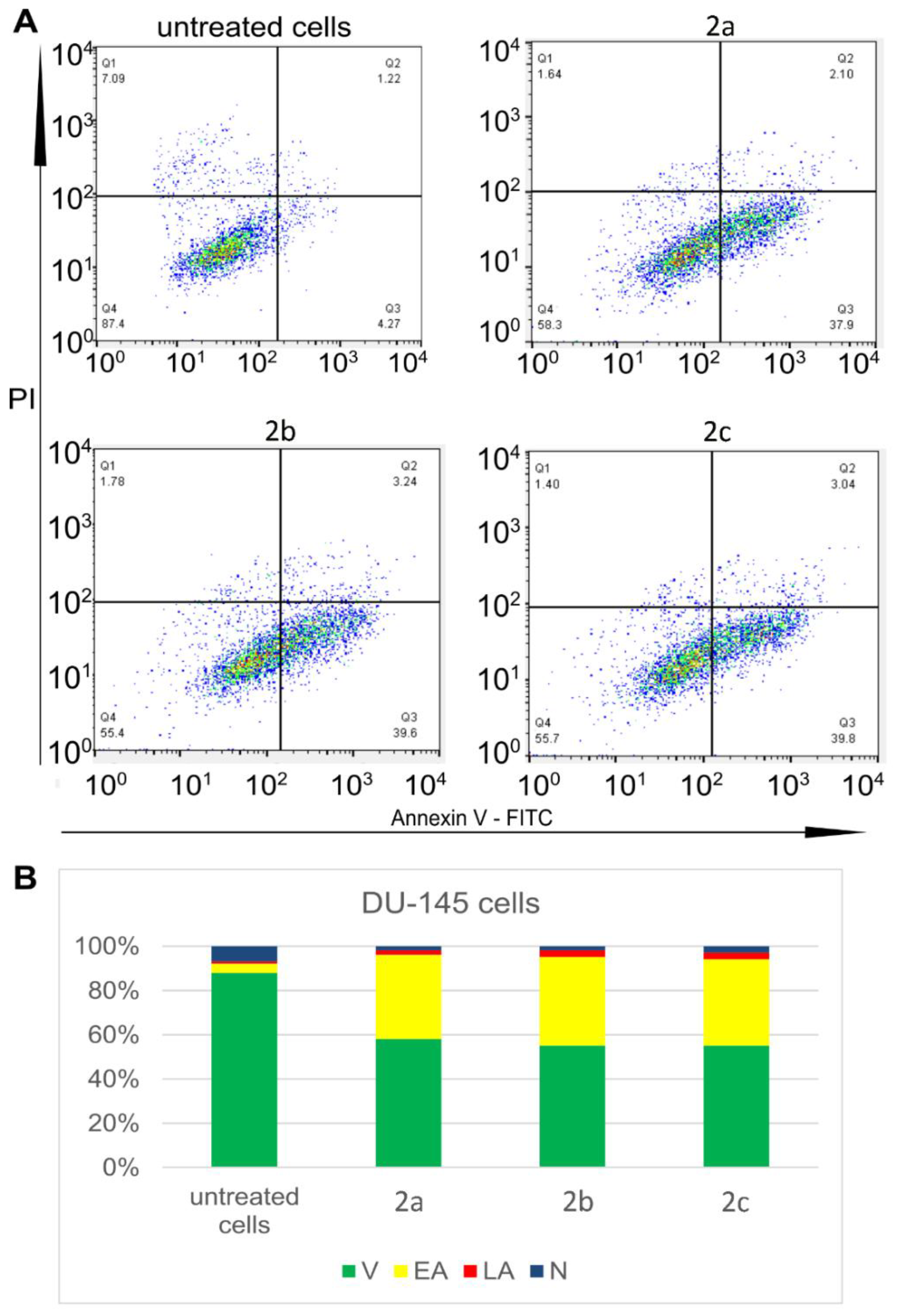

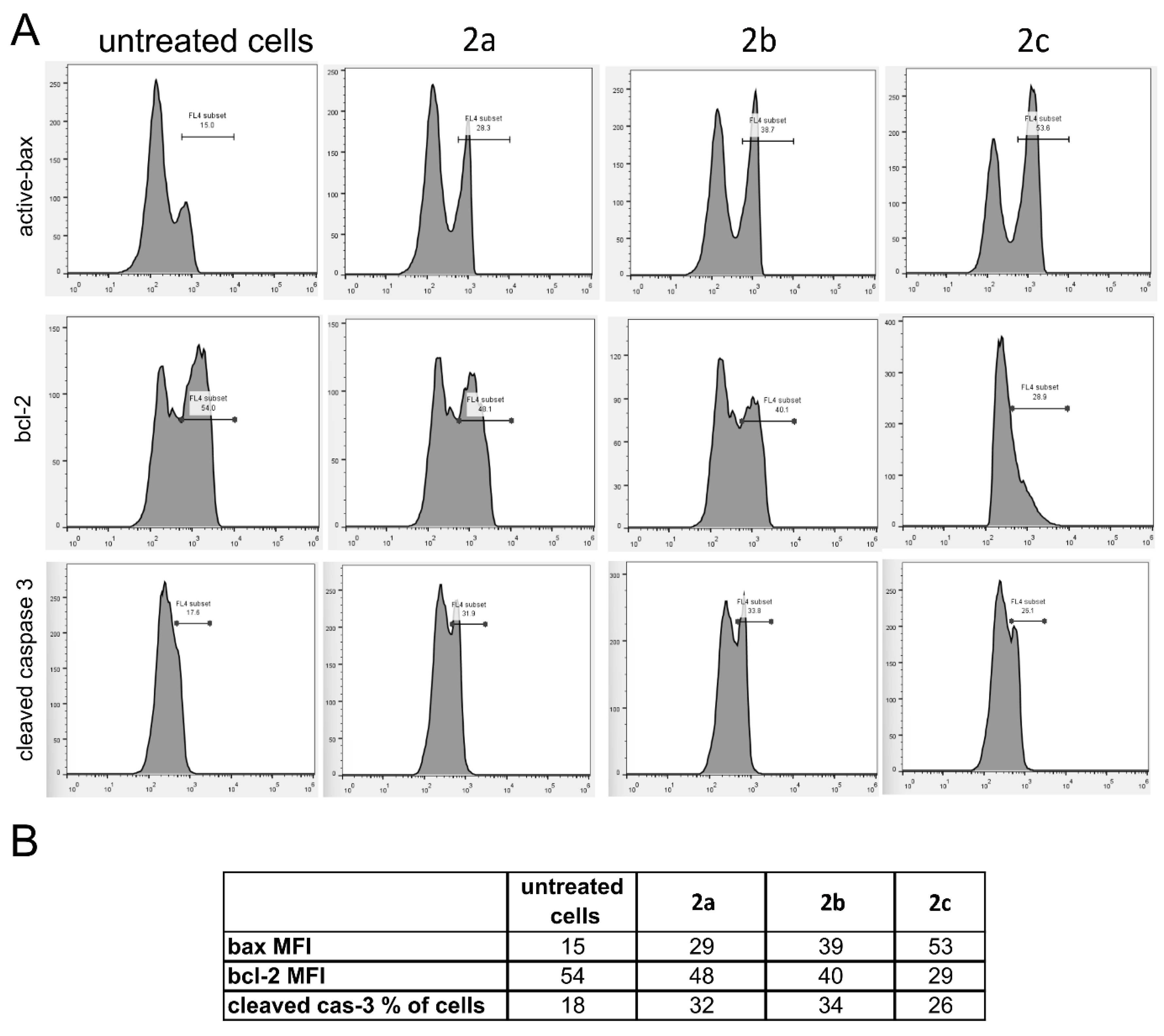

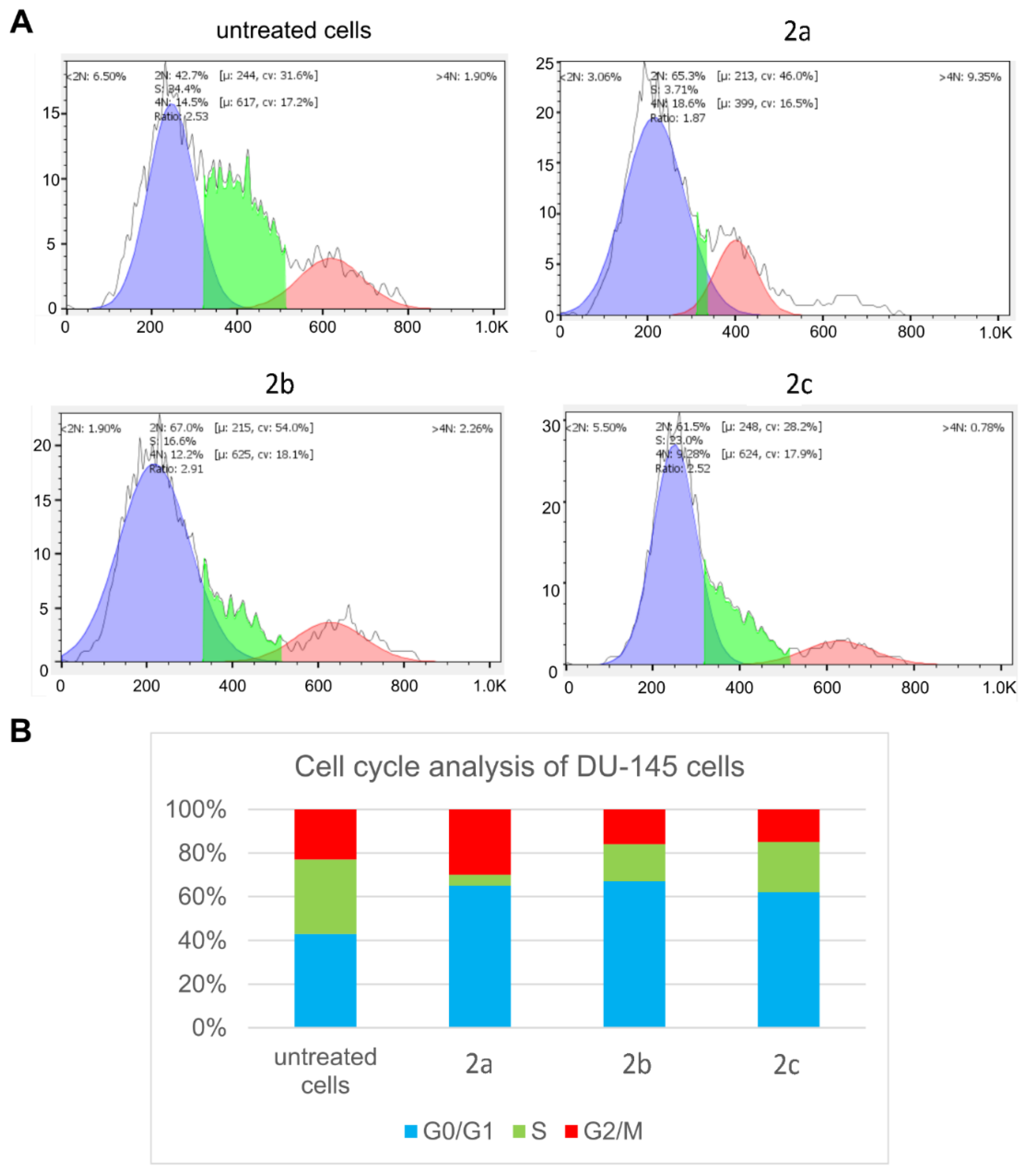

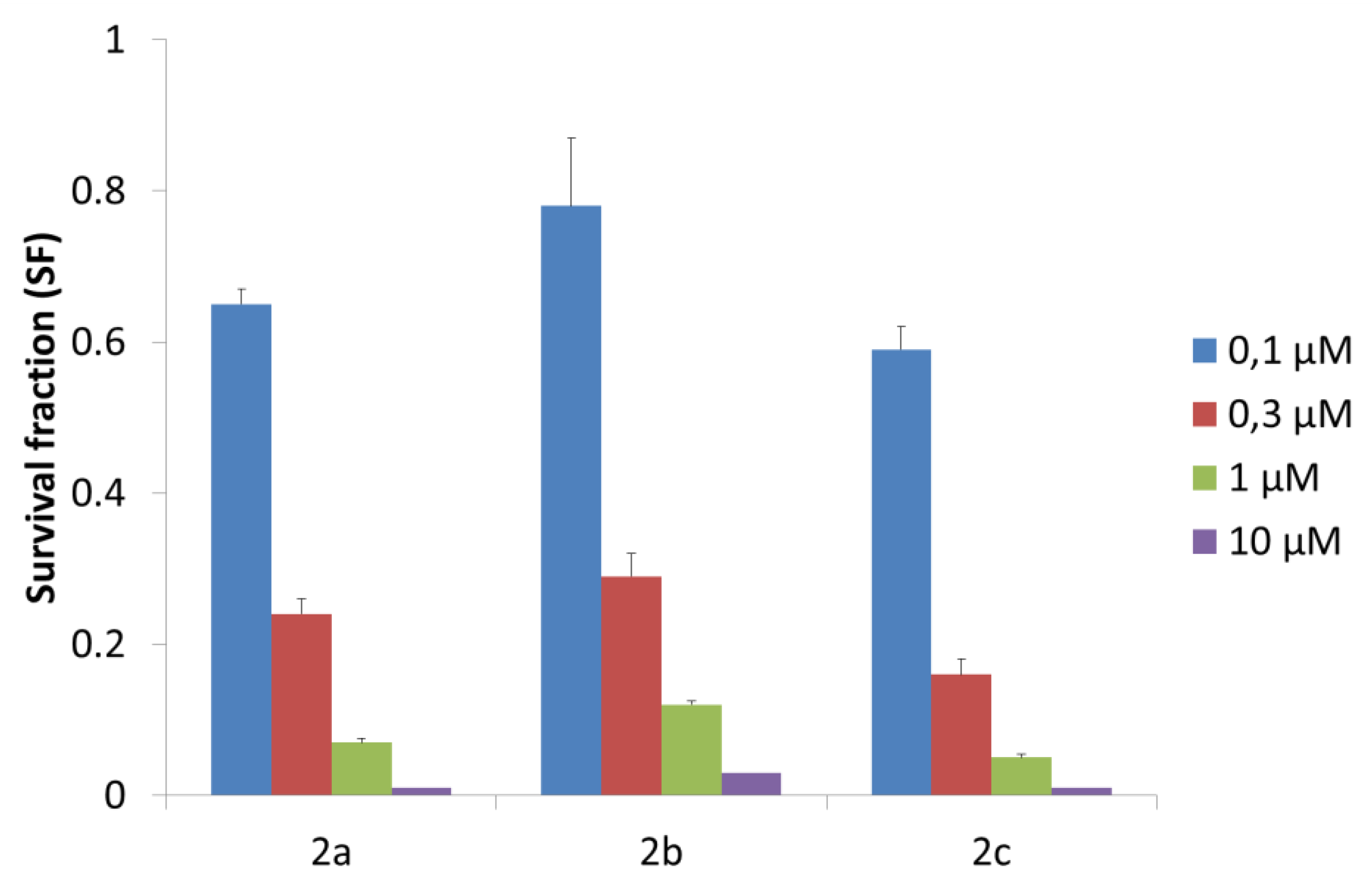

2.4. In Vitro Cytotoxic Study

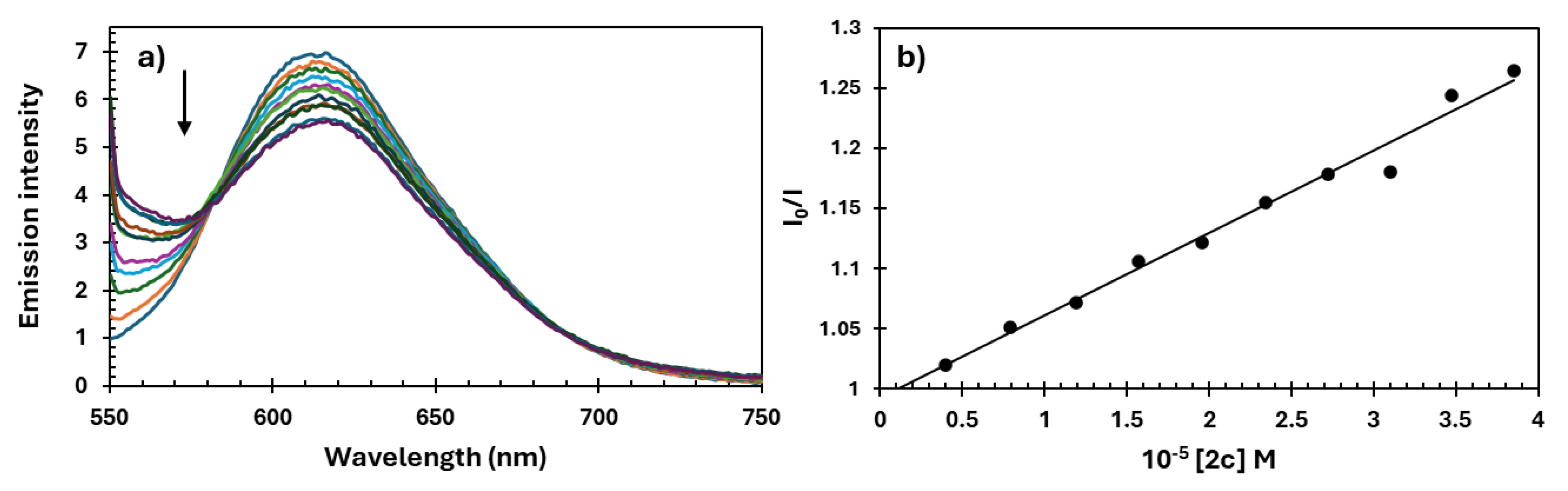

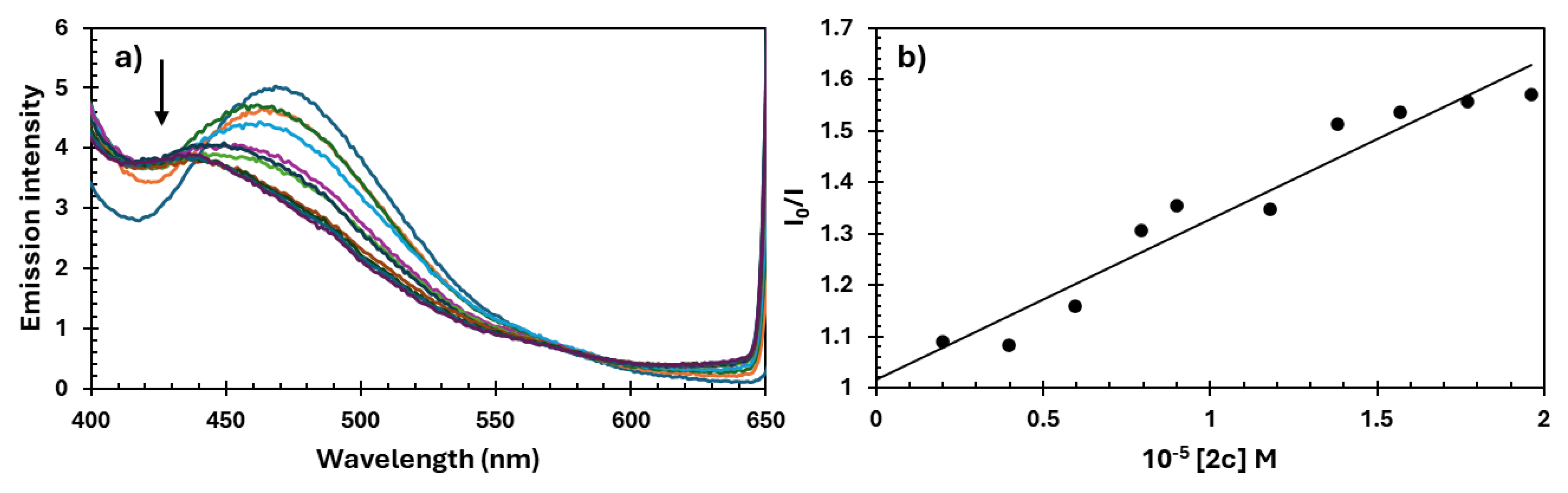

2.5. DNA Interaction Study

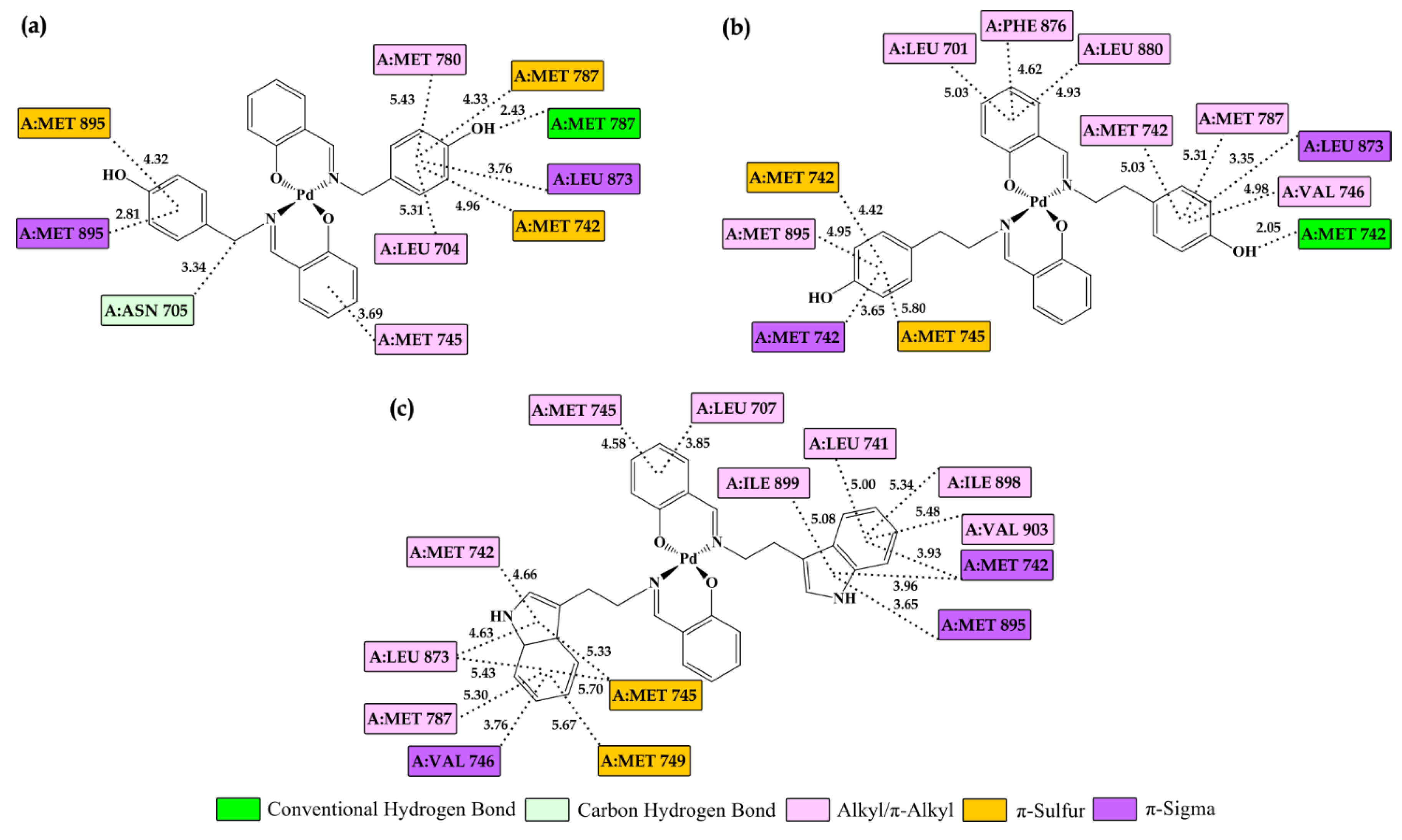

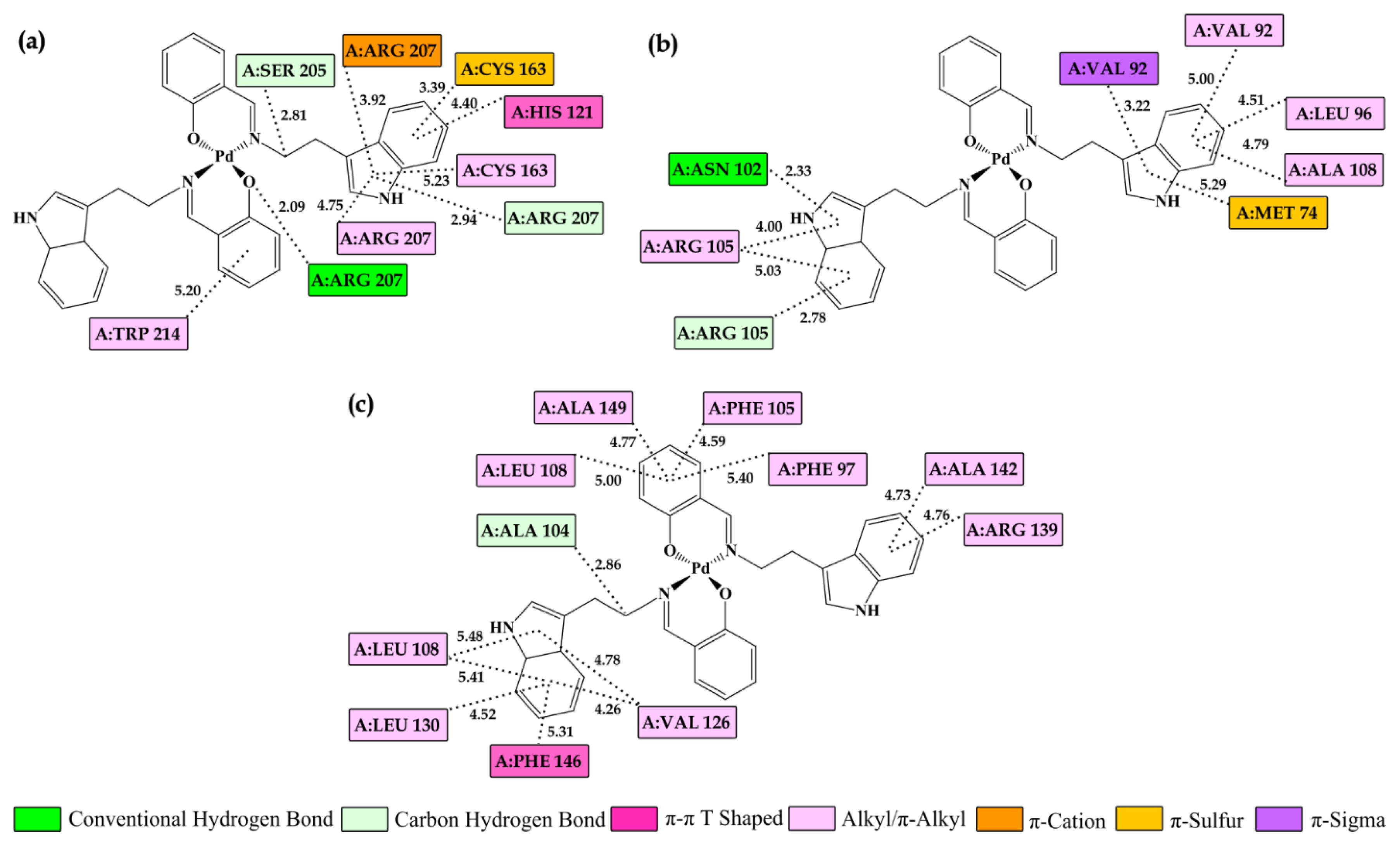

2.6. Molecular Docking Study

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, G.; Cherukommu, S.; Srinivas, G.; Lee, S.W.; Mun, S.H.; Jung, J.; Nagesh, N.; Lee, C.Y. BODIPY-Based Ru(II) and Ir(III) Organometallic Complexes of Avobenzone, a Sunscreen Material: Potent Anticancer Agents. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 189, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, J.M.; Blower, T.R.; Gallagher, N.; Gill, J.H.; Rockley, K.L.; Walton, J.W. Anticancer Ru II and Rh III Piano-Stool Complexes That Are Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Chempluschem 2016, 81, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanski, M.S.; Arion, V.B.; Jakupec, M.A.; Keppler, B.K. Recent Developments in the Field of Tumor-Inhibiting Metal Complexes. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003, 9, 2078–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.K.; Noor, A.; Samantaray, P.K. Ir(III) and Ru(II) Complexes in Photoredox Catalysis and Photodynamic Therapy: A New Paradigm towards Anticancer Applications. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 3270–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathima, T.S.; Choudhury, B.; Ahmad, M.G.; Chanda, K.; Balamurali, M.M. Recent Developments on Other Platinum Metal Complexes as Target-Specific Anticancer Therapeutics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 490, 215231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, T.; Rilak, A.; Bugarčić, Ž.D. Platinum, Palladium, Gold and Ruthenium Complexes as Anticancer Agents: Current Clinical Uses, Cytotoxicity Studies and Future Perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 142, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vojtek, M.; Marques, M.P.M.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O.; Mota-Filipe, H.; Diniz, C. Anticancer Activity of Palladium-Based Complexes against Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, T.J.; Martins, A.S.; Marques, M.P.M.; Gil, A.M. Metabolic Aspects of Palladium(II) Potential Anti-Cancer Drugs. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Surrah, A.; Kettunen, M. Platinum Group Antitumor Chemistry: Design and Development of New Anticancer Drugs Complementary to Cisplatin. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 1337–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, H.G.; Akkoç, S.; Kökbudak, Z. Anticancer Activities of Various New Metal Complexes Prepared from a Schiff Base on A549 Cell Line. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 111, 107645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Yazdi, S.A.; Mirzaahmadi, A.; Khandar, A.A.; Eigner, V.; Dušek, M.; Lotfipour, F.; Mahdavi, M.; Soltani, S.; Dehghan, G. Synthesis, Characterization and in Vitro Biological Activities of New Water-Soluble Copper(II), Zinc(II), and Nickel(II) Complexes with Sulfonato-Substituted Schiff Base Ligand. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2017, 458, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdhami, B.; Ambika, S.; Karthiyayini, B.; Ramya, V.; Kadalmani, B.; Vimala, R.T.V.; Akbarsha, M.A. Potential Application of Two Cobalt (III) Schiff Base Complexes in Cancer Chemotherapy: Leads from a Study Using Breast and Lung Cancer Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2021, 75, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, M.M.; Ali, H.I.; Anwar, M.M.; Mohamed, N.A.; Soliman, A.M. Synthesis, Antitumor Activity and Molecular Docking Study of Novel Sulfonamide-Schiff’s Bases, Thiazolidinones, Benzothiazinones and Their C-Nucleoside Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, T.; Sang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Luo, Y. Design and Synthesis of Novel Pyrimidine Derivatives as Potent Antitubercular Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 163, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiriveedhi, A.; Nadh, R.V.; Srinivasu, N.; Bobde, Y.; Ghosh, B.; Sekhar, K.V.G.C. Design, Synthesis and Anti-Tumour Activity of New Pyrimidine-Pyrrole Appended Triazoles. Toxicol. Vitr. 2019, 60, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, L.H.T.; Shawer, T.Z.; El-Naggar, A.M.; El-Sehrawi, H.M.A. Design, Synthesis, Anticancer Evaluation and Docking Studies of New Pyrimidine Derivatives as Potent Thymidylate Synthase Inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 91, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmidi, S.; Anouar, E.H.; El Hafi, M.; Boulhaoua, M.; Ejjoummany, A.; El Jemli, M.; Essassi, E.M.; Mague, J.T. Synthesis, X-Ray, Spectroscopic Characterization, DFT and Antioxidant Activity of 1,2,4-Triazolo [1,5-a]Pyrimidine Derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1177, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Yu, S.; Quan, L.; Mansoor, M.; Chen, Z.; Hu, H.; Liu, D.; Liang, Y.; Liang, F. Synthesis and Antitumor Activities of Transition Metal Complexes of a Bis-Schiff Base of 2-Hydroxy-1-Naphthalenecarboxaldehyde. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 210, 111173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchsheela Ashok, U.; Prasad Kollur, S.; Prakash Arun, B.; Sanjay, C.; Shrikrishna Suresh, K.; Anil, N.; Vasant Baburao, H.; Markad, D.; Ortega Castro, J.; Frau, J.; et al. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of 4(3H)-Quinazolinone Derived Schiff Base and Its Cu(II), Zn(II) and Cd(II) Complexes: Preparation, X-Ray Structural, Spectral Characterization and Theoretical Investigations. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2020, 511, 119846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhivya, R.; Jaividhya, P.; Riyasdeen, A.; Palaniandavar, M.; Mathan, G.; Akbarsha, M.A. In Vitro Antiproliferative and Apoptosis-Inducing Properties of a Mononuclear Copper(II) Complex with Dppz Ligand, in Two Genotypically Different Breast Cancer Cell Lines. BioMetals 2015, 28, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.-Y.; Qiao, X.; Xie, C.-Z.; Shao, J.; Xu, J.-Y.; Qiang, Z.-Y.; Lou, J.-S. Activities of a Novel Schiff Base Copper(II) Complex on Growth Inhibition and Apoptosis Induction toward MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells via Mitochondrial Pathway. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 117, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbağ, B.; Ballı, E.; Yıldırım, M.; Ünver, H.; Temel, G.; Yılmaz, M.K.; Değirmenci, E.; Kibar, D. Investigation of the Anticancer of Photodynamic Therapy Effects by Using the Novel Schiff Base Ligand Palladium Complexes on Human Breast Cancer Cell Line. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 7611–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolski-Renić, A.; Čipak Gašparović, A.; Valente, A.; López, Ó.; Bormio Nunes, J.H.; Kowol, C.R.; Heffeter, P.; Filipović, N.R. Schiff Bases and Their Metal Complexes to Target and Overcome (Multidrug) Resistance in Cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 270, 116363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, B. The Role of the Androgen Receptor in the Development of Prostatic Hyperplasia and Prostate Cancer. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 253, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cheng, D.; Li, P. Androgen Receptor Dynamics in Prostate Cancer: From Disease Progression to Treatment Resistance. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacar, O.; Cevatemre, B.; Hatipoglu, I.; Arda, N.; Ulukaya, E.; Yilmaz, V.T.; Acilan, C. The Role of Cell Cycle Progression for the Apoptosis of Cancer Cells Induced by Palladium(II)-Saccharinate Complexes of Terpyridine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 1770–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deljanin, M.; Nikolic, M.; Baskic, D.; Todorovic, D.; Djurdjevic, P.; Zaric, M.; Stankovic, M.; Todorovic, M.; Avramovic, D.; Popovic, S. Chelidonium Majus Crude Extract Inhibits Migration and Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Tumor Cell Lines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 190, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, M.M.; AbdElhameid, M.K.; Adel, M.; Al-Shorbagy, M.Y.; Negmeldin, A.T. Design, Synthesis, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Novel Indolin-2-One Based Molecules on Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells as Protein Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2025, 30, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.M.; Abdel-hameid, M.K.; El-Nassan, H.B.; El-Khouly, E.A. Synthesis and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Novel Indole Derivatives as Potential Anti-Cancer Agents. Med. Chem. (Los. Angeles). 2019, 15, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, A.; Conforti, F.; Crispini, A.; De Martino, A.; Condello, R.; Stellitano, C.; Rotilio, G.; Ghedini, M.; Federici, G.; Bernardini, S.; et al. Synthesis, Oxidant Properties, and Antitumoral Effects of a Heteroleptic Palladium(II) Complex of Curcumin on Human Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulukaya, E.; Frame, F.M.; Cevatemre, B.; Pellacani, D.; Walker, H.; Mann, V.M.; Simms, M.S.; Stower, M.J.; Yilmaz, V.T.; Maitland, N.J. Differential Cytotoxic Activity of a Novel Palladium-Based Compound on Prostate Cell Lines, Primary Prostate Epithelial Cells and Prostate Stem Cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plutín, A.M.; Mocelo, R.; Alvarez, A.; Ramos, R.; Castellano, E.E.; Cominetti, M.R.; Graminha, A.E.; Ferreira, A.G.; Batista, A.A. On the Cytotoxic Activity of Pd(II) Complexes of N,N-Disubstituted-N′-Acyl Thioureas. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 134, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laginha, R.C.; Martins, C.B.; Brandão, A.L.C.; Marques, J.; Marques, M.P.M.; Batista de Carvalho, L.A.E.; Santos, I.P.; Batista de Carvalho, A.L.M. Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Effect of Pd2Spm against Prostate Cancer through Vibrational Microspectroscopies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.K.; Ameta, R.K.; Singh, M. Biological Impact of Pd (II) Complexes: Synthesis, Spectral Characterization, In Vitro Anticancer, CT-DNA Binding, and Antioxidant Activities. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, J.; Fernández-Delgado, E.; Estirado, S.; de la Cruz-Martinez, F.; Villa-Carballar, S.; Viñuelas-Zahínos, E.; Luna-Giles, F.; Pariente, J.A. Synthesis and Structure of a New Thiazoline-Based Palladium(II) Complex That Promotes Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis of Human Promyelocytic Leukemia HL-60 Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinlik, S.; Erkisa, M.; Ari, F.; Celikler, S.; Ulukaya, E. Palladium (II) Complex Enhances ROS-Dependent Apoptotic Effects via Autophagy Inhibition and Disruption of Multiple Signaling Pathways in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 1284–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, W.; Paz, J.; Carrasco, F.; Vaisberg, A.; Spodine, E.; Manzur, J.; Hennig, L.; Sieler, J.; Blaurock, S.; Beyer, L. Synthesis and Characterization of New Palladium(II) Thiosemicarbazone Complexes and Their Cytotoxic Activity against Various Human Tumor Cell Lines. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2013, 2013, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontek, R.; Matławska-Wasowska, K.; Kalinowska-Lis, U.; Kontek, B.; Ochocki, J. Evaluation of Cytotoxicity of New Trans-Palladium(II) Complex in Human Cells in Vitro. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2011, 68, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Recio Despaigne, A.; Da Silva, J.; Da Costa, P.; Dos Santos, R.; Beraldo, H. ROS-Mediated Cytotoxic Effect of Copper(II) Hydrazone Complexes against Human Glioma Cells. Molecules 2014, 19, 17202–17220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarushi, A.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Psycharis, V.; Terzis, A.; Psomas, G.; Kessissoglou, D.P. Zinc(II) Complexes of the Second-Generation Quinolone Antibacterial Drug Enrofloxacin: Structure and DNA or Albumin Interaction. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 2678–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarushi, A.; Lafazanis, K.; Kljun, J.; Turel, I.; Pantazaki, A.A.; Psomas, G.; Kessissoglou, D.P. First- and Second-Generation Quinolone Antibacterial Drugs Interacting with Zinc(II): Structure and Biological Perspectives. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 121, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakowicz, J.R.; Weber, G. Quenching of Fluorescence by Oxygen. Probe for Structural Fluctuations in Macromolecules. Biochemistry 1973, 12, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakowicz, J.R.; Gryczynski, I.; Gryczynski, Z.; Dattelbaum, J.D. Anisotropy-Based Sensing with Reference Fluorophores. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 267, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira de Freitas, R.; Schapira, M. A Systematic Analysis of Atomic Protein–Ligand Interactions in the PDB. Medchemcomm 2017, 8, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.A.; Castellano, R.K.; Diederich, F. Interactions with Aromatic Rings in Chemical and Biological Recognition. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 1210–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissantz, C.; Kuhn, B.; Stahl, M. A Medicinal Chemist’s Guide to Molecular Interactions. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 5061–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki, S.; Honda, K.; Uchimaru, T.; Mikami, M.; Tanabe, K. Origin of Attraction and Directionality of the π/π Interaction: Model Chemistry Calculations of Benzene Dimer Interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevi, A.S.; Sastry, G.N. Cation−π Interaction: Its Role and Relevance in Chemistry, Biology, and Material Science. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 2100–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Imine Proton -HC=N |

Salicylic OH Proton |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | 8.65 ppm, s | 13.56 ppm, s |

| 2a | 8.20 ppm, s | missing |

| 1b | 8.45 ppm, s | 13.54 ppm, s |

| 2b | 7.91 ppm, s | missing |

| 1c | 8.48 ppm, s | 13.69 ppm, s |

| 2c | 7.96 ppm, s | missing |

| Cell Line | Time | 2a | 2b | 2c | CP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DU-145 | 24 h | 83.6±9.2 | 75.9±7.3 | 48.4±5.1 | 22.3±2.4 |

| 48 h | 17.5±1.6 | 19.2±2.1 | 11.0±1.2 | 11.4±1.1 | |

| 72 h | 9.3±0.9 | 8.7±0.8 | 7.1±0.8 | 8.2±0.8 | |

| PC-3 | 24 h | 94.1±9.1 | 75.2±7.2 | 38.4±3.6 | 15.6±1.4 |

| 48 h | 89.8±8.8 | 58.6±5.6 | 12.5±1.1 | 29.7±3.1 | |

| 72 h | 79.3±7.7 | 29.1±2.8 | 8.6±0.9 | 21.9±2.2 | |

| MRC-5 | 24 h | 94.3±9.7 | 87.7±8.8 | 80.7±8.1 | 90.1±9.2 |

| 48 h | 92.4±9.1 | 78.5±7.7 | 75.6±7.7 | 41.9±4.4 | |

| 72 h | 83.0±8.1 | 49.2±5.1 | 42.3±4.1 | 24.4±0.8 |

| Complex | ΔGbind | Ki (µM) |

ΔGinter | ΔGvdw+hbond+desolv | ΔGelec | ΔGtotal | ΔGtor | ΔGunb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | ||||||||

| 2a | -5.56 | 83.36 | -7.21 | -7.23 | 0.02 | -1.29 | 1.65 | -1.29 |

| 2b | -8.44 | 0.65 | -10.64 | -10.62 | -0.02 | -1.74 | 2.20 | -1.74 |

| 2c | -10.51 | 0.02 | -12.16 | -12.21 | 0.05 | -2.47 | 1.65 | -2.47 |

| BIC | -9.11 | 0.21 | -10.76 | -10.65 | -0.11 | -1.92 | 1.65 | -1.92 |

| Complex | ΔGbind | Ki (µM) |

ΔGinter | ΔGvdw+hbond+desolv | ΔGelec | ΔGtotal | ΔGtor | ΔGunb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | ||||||||

| CASP3 | -7.88 | 1.66 | -9.53 | -9.49 | -0.04 | -1.18 | 1.65 | -1.18 |

| BCL2 | -7.92 | 1.56 | -9.57 | -9.39 | -0.18 | -1.39 | 1.65 | -1.39 |

| BAX | -7.68 | 2.36 | -9.32 | -9.27 | -0.05 | -1.54 | 1.65 | -1.54 |

| 2b | ||||||||

| CASP3 | -7.98 | 1.42 | -10.17 | -9.92 | -0.25 | -1.90 | 2.20 | -1.90 |

| BCL2 | -8.08 | 1.20 | -10.27 | -10.22 | -0.06 | -1.87 | 2.20 | -1.87 |

| BAX | -6.86 | 9.31 | -9.06 | -8.98 | -0.08 | -2.18 | 2.20 | -2.18 |

| 2c | ||||||||

| CASP3 | -8.81 | 0.35 | -10.46 | -10.41 | -0.05 | -2.89 | 1.65 | -2.89 |

| BCL2 | -8.26 | 0.88 | -9.91 | -9.85 | -0.06 | -2.91 | 1.65 | -2.91 |

| BAX | -8.44 | 0.65 | -10.09 | -10.11 | 0.02 | -2.72 | 1.65 | -2.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).