Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

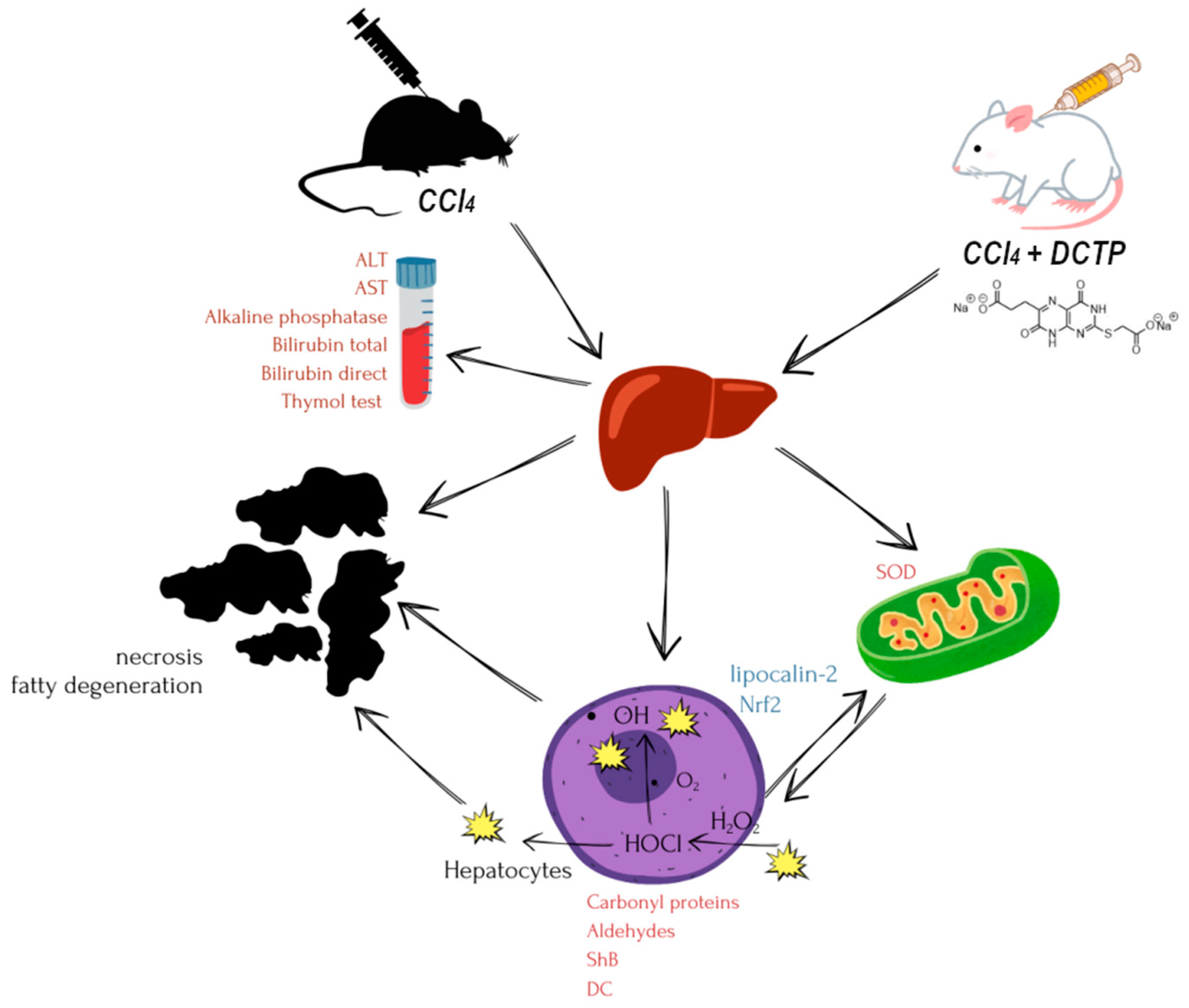

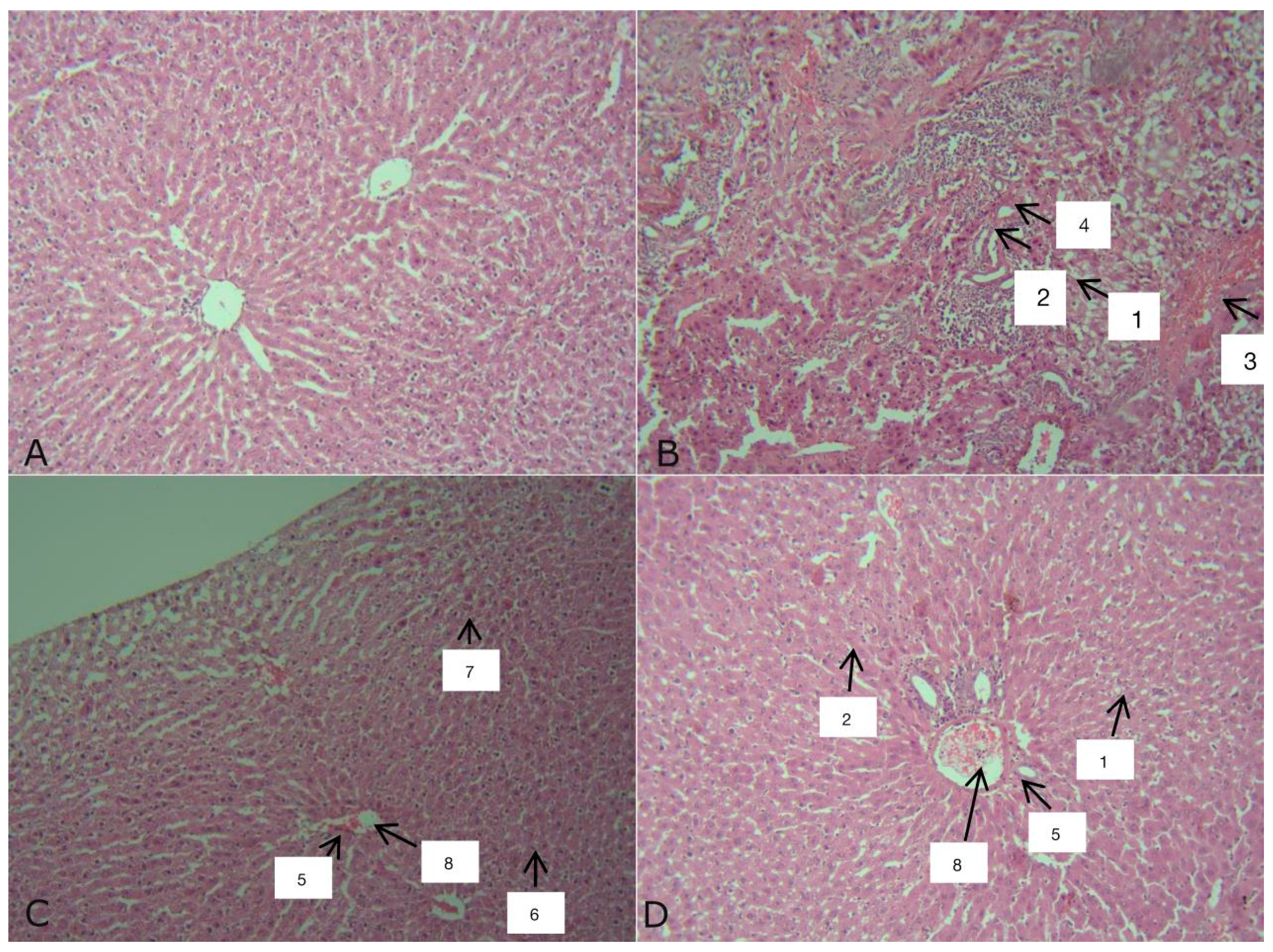

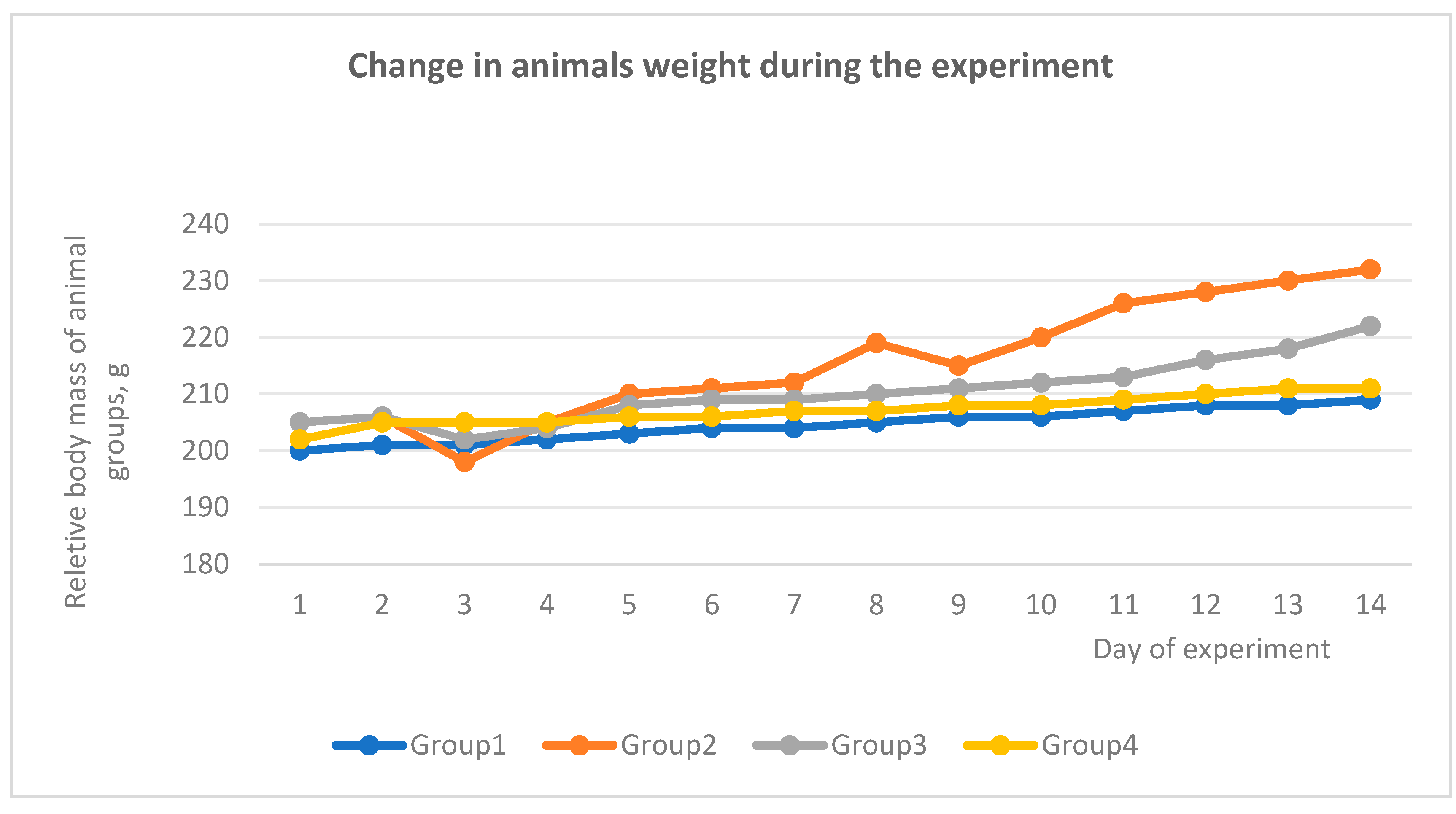

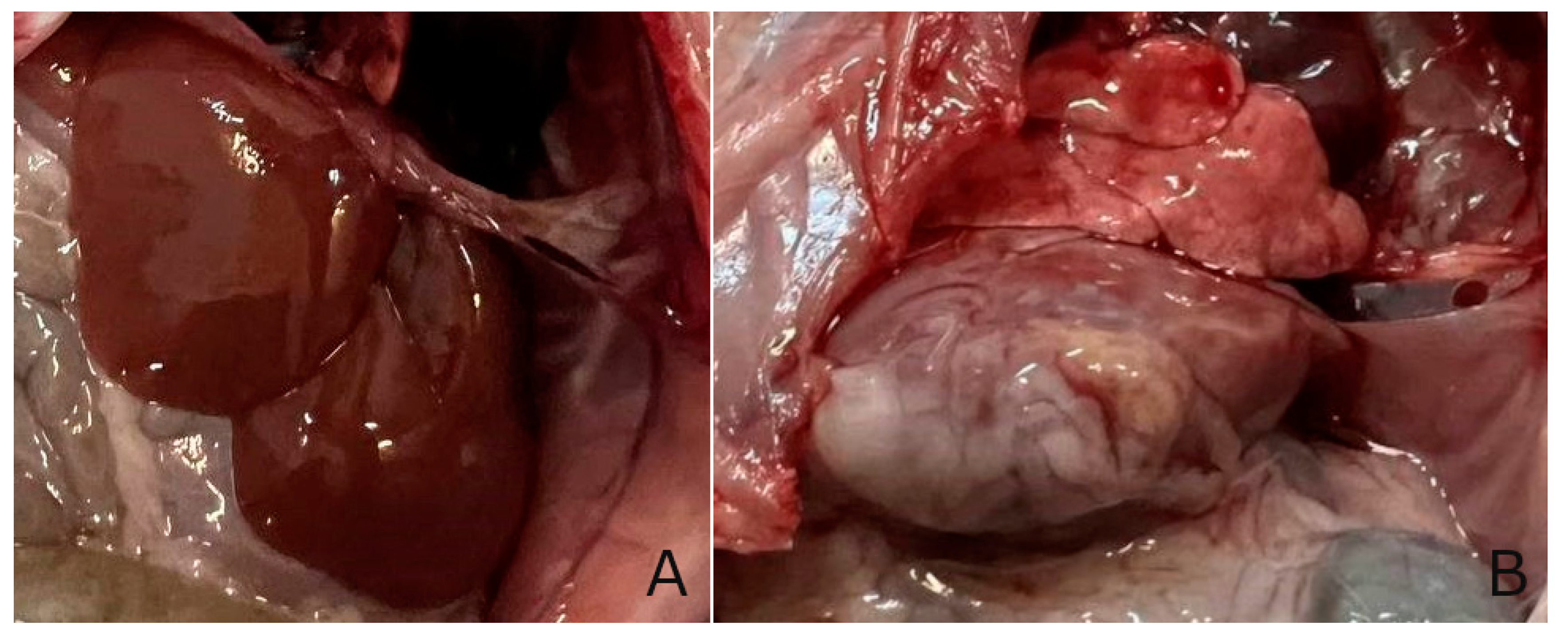

3.1. Hepatoprotective Effect of DCTP on the Model of Toxic Liver Damage by Carbon Tetrachloride.

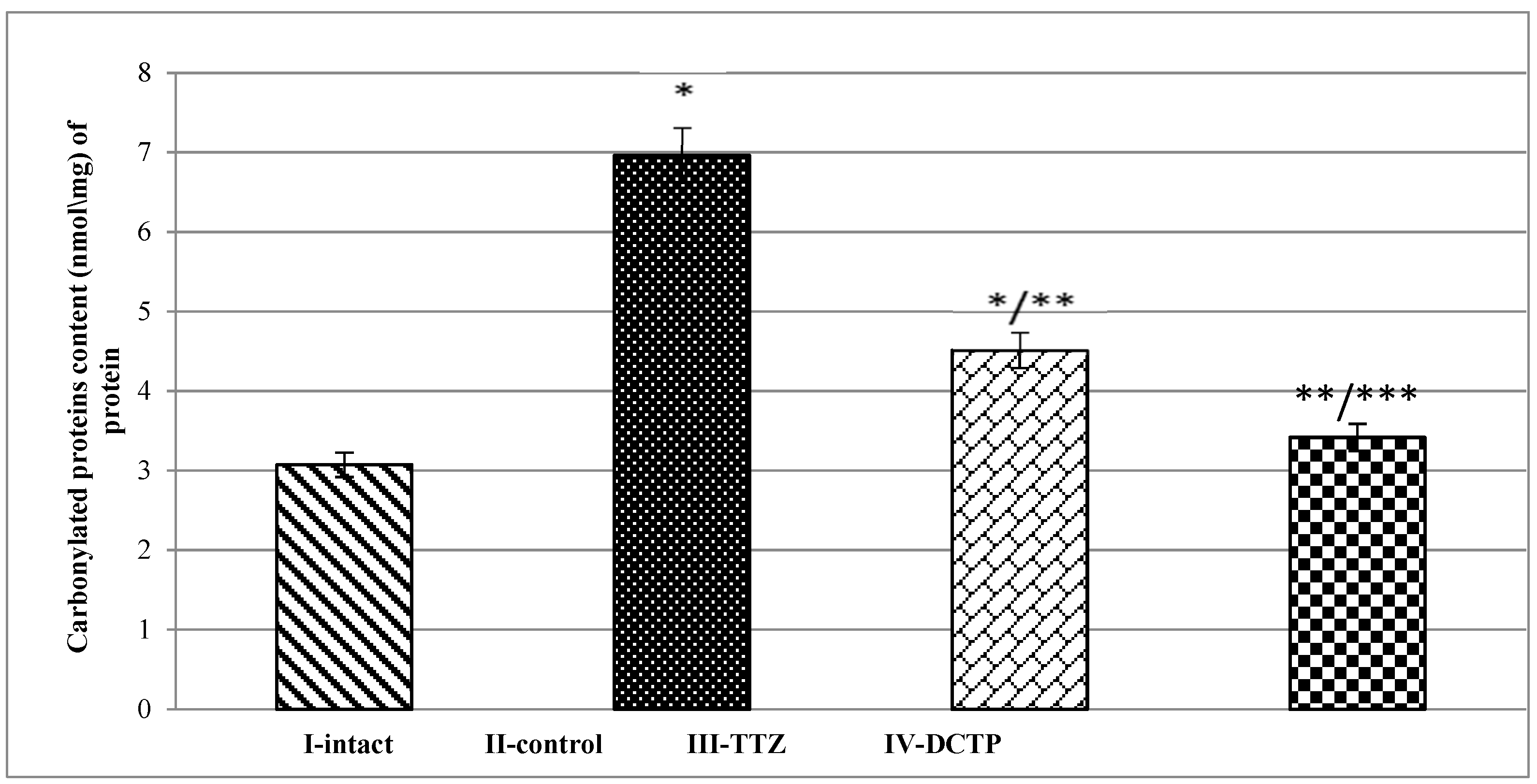

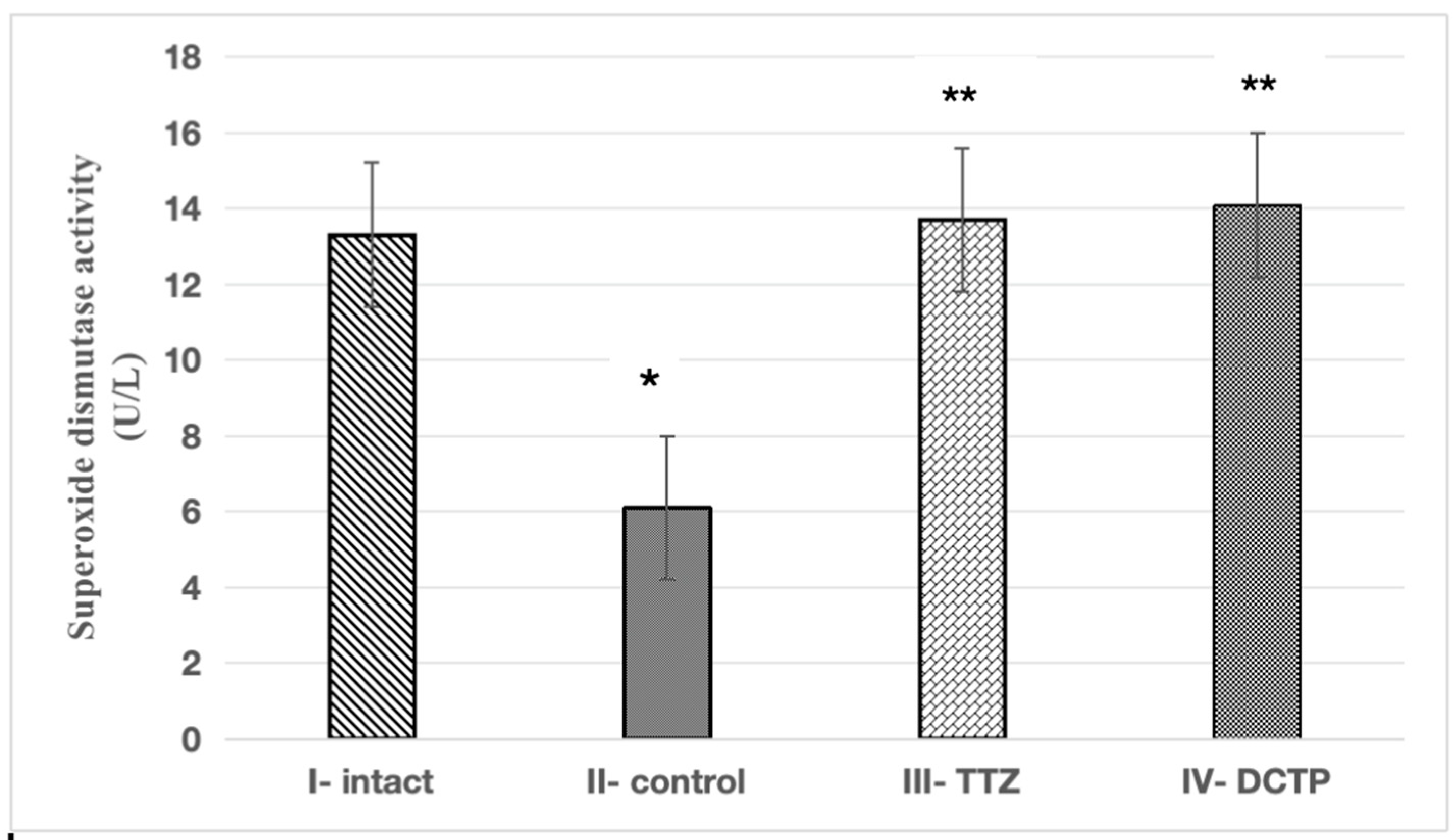

3.2. Some Indicators of the Prooxidant-Antioxidant System in the Studied Groups of Animals

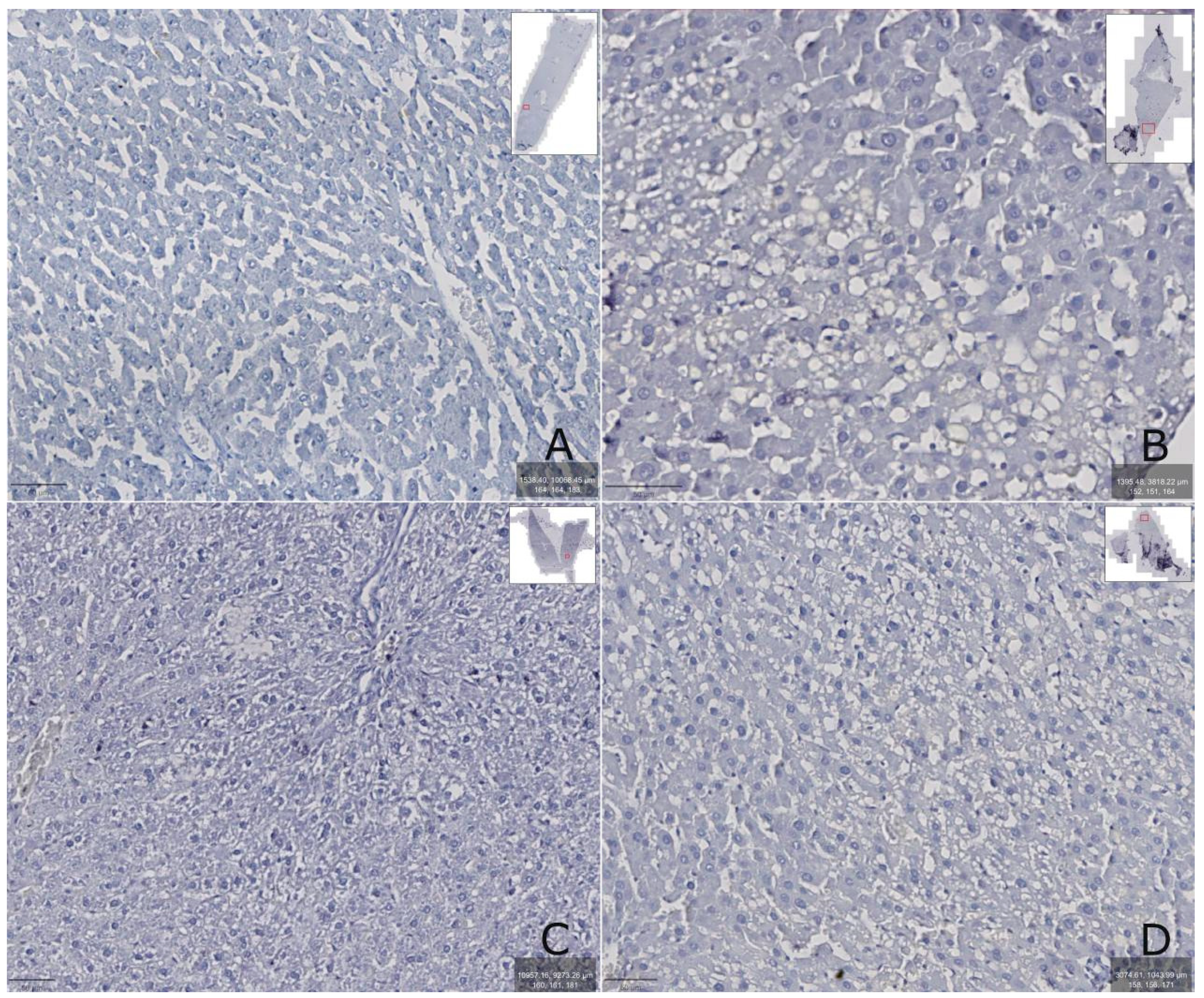

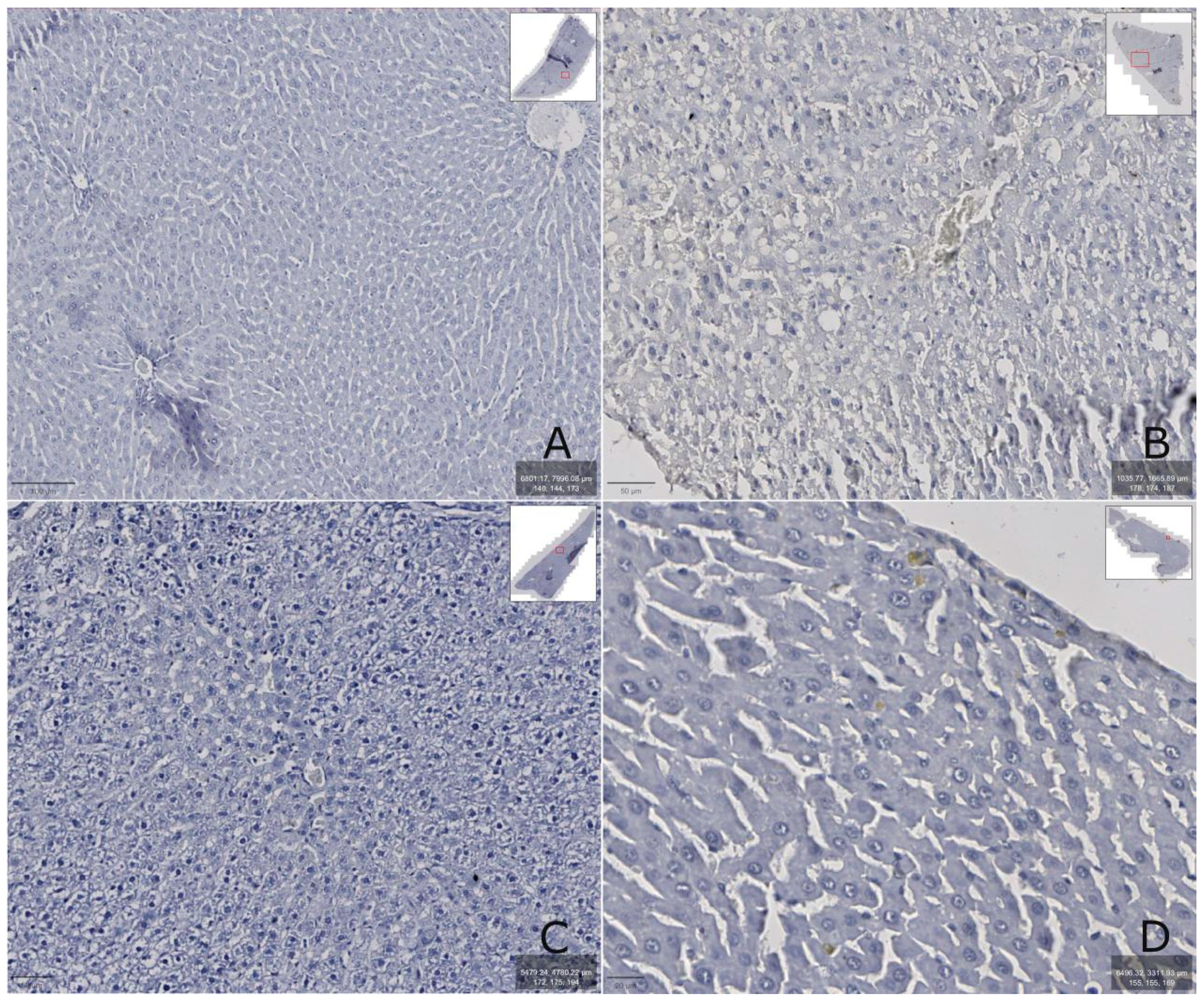

3.3. Immunohistological and Cytological Indices in the Studied Groups of Animals.

3.4. Some Physiological Indicators in the Studied Groups of Animals

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asrani, S.K.; Devarbhavi, H.; Eaton, J.; Kamath, P.S. Burden of Liver Diseases in the World. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, R.; Carey, J.J. Risk of Liver Disease in Methotrexate Treated Patients. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Shea, R.S.; Dasarathy, S.; McCullough, A.J. Alcoholic Liver Disease. Hepatology 2009, 51, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeter, G.; Lee, C.Z.; Schwarze, P.K.; Ous, S.; Chen, D.S.; et al. Changes in Ploidy Distributions in Human Liver Carcinogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1988, 80, 1480–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Gordillo, K.; Shah, R.; Muriel, P. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Hepatic Diseases: Current and Future Therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 3140673. [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.P. The Role of Intestinal Endotoxin in Liver Injury: A Long and Evolving History. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.R.; Marion, D.W.; Cornatzer, W.E.; Duerre, J.A. S-Adenosylmethionine and S-Adenosylhomocysteine Metabolism in Isolated Rat Liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 10822–10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Field, M.S.; Stover, P.J. Cell Cycle Regulation of Folate-Mediated One-Carbon Metabolism. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2018, 10, e1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, C.; Harputlugil, E.; Zhang, Y.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Lee, B.C.; et al. Endogenous Hydrogen Sulfide Production is Essential for Dietary Restriction Benefits. Cell 2015, 160, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, S.M.; Gao, X.; Dai, Z.; Locasale, J.W. Methionine Metabolism in Health and Cancer: A Nexus of Diet and Precision Medicine. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DrugBank. DB12687. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB12687 (accessed on 12 of December 2024).

- Kazunin, M.S.; Groma, N.V.; Nosulenko, I.S.; Kinichenko, A.O.; Antypenko, O.M.; Shvets, V.M.; Voskoboinik, O.Y.; Kovalenko, S.I. Thio-Containing Pteridines: Synthesis, Modification, and Biological Activity. Arch. Pharm. 2022, 355, 2200252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohvinenko, N.; Shvets, V.; Berest, G.; Nosulenko, I.; Voskoboinik, O.; Severina, H.; Okovytyy, S.; Kovalenko, S. Prospects for the Use of Sulfur-Containing Pteridines in Toxic Liver Damage. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2024, 15, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstien, S.; Kapatos, G.; Levine, R.A.; Shane, B. Chemistry and Biology of Pteridines and Folates; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groma, N.; Berest, G.; Antypenko, O.; Voskoboinik, O.; Kopiika, V.; et al. Evaluation of the Toxicity and Hepatoprotective Properties of New S-Substituted Pteridins. Curr. Issues Pharm. Med. Sci. 2023, 36(1), 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhem'yakin, Yu.M.; Khromov, O.S.; Filonenko, M.A. Scientific and practical recommendations for the development of laboratory creatures and robots. K.: Avitsena; 2002; 156.

- European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes. European Treaty Series - No. 123. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; 1986.

- Stefanov, O.V. Preclinical Study of Drugs (Methodical Recommendation). Kyiv: Avitsena; 2001; 527.

- Bhakuni, G.S.; Bedi, O.; Bariwal, J.; Deshmukh, R.; Kumar, P. Animal Models of Hepatotoxicity. Inflammation Research 2015, 65, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, I.A.; Voloshin, N.A.; Chekman, I.S. Thiotriazolin: Pharmacological Aspects and Clinical Application. Lvov: Zaporizhye; 2005; 160.

- Recknagel, R.O.; Ghoshal, A.K. Quantitative Estimation of Peroxidative Degeneration of Rat Liver Microsomal and Mitochondrial Lipids After Carbon Tetrachloride Poisoning. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 1966, 5, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, M.C.R.; Diplock, A.T.; Rice-Evans, C.A. Techniques in Free Radical Research; Elsevier Science & Technology Books: 1991. ISBN 978008085 8913.

- Kostyuk, V.A. A Simple and Sensitive Method for Determining Superoxide Dismutase Activity Based on the Oxidation Reaction of Quercetin. Questions Med. Chem. 1990, 36, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.L.; Stadtman, E.R. Oxidative Modification of Proteins During Aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlizlo, V.V.; Fedoruk, R.S.; Ratych, I.B.; Vishurt, O.I.; Sharan, M.M.; Vudmaska, I.V.; Fedorovych, E.I. Laboratory Research Methods in Biology, Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine: A Guide; Spolom: Lviv, 2012; 764p. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann, G.; Klauke, R.; Canalias, F.; Bossert-Reuther, S.; Franck, P.F.H.; et al. IFCC Primary Reference Procedures for the Measurement of Catalytic Activity Concentrations of Enzymes at 37 °C. Part 9: Reference Procedure for the Measurement of Catalytic Concentration of Alkaline Phosphatase. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2011, 49, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, V.V.; Shvets, V.N. Guide to Practical Classes in Biological Chemistry (for Students of Medical Schools III-IV Level of Accreditation); KhNU Named after V.N. Karazin: Kharkiv, 2011; 316p, ISBN 978-966-623-774-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jendrassik, L.; Grof, P. Colorimetric Method of Determination of Bilirubin. Biochem. Z. 1938, 297, 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Menshikov, V.V. Laboratory Research Methods in Clinic. Meditsina 1987, 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Borkham-Kamphorst, E.; Kovalenko, E.; Van Roeyen, C.R.C.; Gassler, N.; Bomble, M.; et al. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Isoform Expression in Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Chronic Liver Injury. Lab. Invest. 2008, 88, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-Y.; Yuan, W.-G.; He, P.; Lei, J.-H.; Wang, C.-X. Liver Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cells: Etiology, Pathological Hallmarks and Therapeutic Targets. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; et al. Dose and Time Dependent Effects of Intraperitoneal Administration of Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4) on Blood Lipid Profile in Wistar Rats. EC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 8, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Manhar, N.; Singh, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Bishnolia, M.; Khurana, A.; et al. Methyl Donor Ameliorates CCl4-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Fibrosis Through the Attenuation of Kidney Injury Molecule 1 and Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Expression. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2025, 39, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Kantartzis, K.; Häring, H.-U. Causes and Metabolic Consequences of Fatty Liver. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagawa, M. Protein Carbonylation: Molecular Mechanisms, Biological Implications, and Analytical Approaches. Free Radic. Res. 2020, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friguet, B.; Bulteau, A.-L.; Chondrogianni, N.; Conconi, M.; Petropoulos, I.-B. Protein Degradation by the Proteasome and Its Implications in Aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 908, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, V.V.; Bozhkov, A.I.; Kulchitsky, O.K. Physiological and Pathophysiological Role of Endogenous Aldehydes; Palmarium Academic Publishing: Saarbrucken, 2012; 240p. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, D.L.; Doorn, J.A.; Kiebler, Z.; Ickes, B.R.; Petersen, D.R. Modification of Heat Shock Protein 90 by 4-Hydroxynonenal in a Rat Model of Chronic Alcoholic Liver Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 315, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, D.L.; Doorn, J.A.; Kiebler, Z.; Petersen, D.R. Cysteine Modification by Lipid Peroxidation Products Inhibits Protein Disulfide Isomerase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005, 18, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.M.; Cho, H.-Y.; Kleeberger, S.R. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in the Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Potential Role for Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.M.; Cheema, A.K.; Zhang, L.; Suzuki, Y.J. Protein Carbonylation as a Novel Mechanism in Redox Signaling. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knockaert, L.; Berson, A.; Ribault, C.; Prost, P.-E.; Fautrel, A.; et al. Carbon Tetrachloride-Mediated Lipid Peroxidation Induces Early Mitochondrial Alterations in Mouse Liver. Lab. Invest. 2011, 92, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VI International Scientific and Theoretical Conference «Sectoral Research XXI: Characteristics and Features»; Primedia eLaunch LLC, 2023; ISBN 9798889557678. [CrossRef]

- Borkham-Kamphorst, E.; Drews, F.; Weiskirchen, R. Induction of Lipocalin-2 Expression in Acute and Chronic Experimental Liver Injury Moderated by Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Interleukin-1β Through Nuclear Factor-κB Activation. Liver Int. 2011, 31, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.L.; Woodworth, J.S.; Lerche, C.J.; Cramer, E.P.; Nielsen, P.R.; et al. Lipocalin-2 Functions as Inhibitor of Innate Resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCicco, L.A.; Rikans, L.E.; Tutor, C.G.; Hornbrook, K.R. Serum and Liver Concentrations of Tumor Necrosis Factor α and Interleukin-1β Following Administration of Carbon Tetrachloride to Male Rats. Toxicol. Lett. 1998, 98, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschke, R.; Vierke, W.; Goldermann, L. Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4) Levels and Serum Activities of Liver Enzymes Following Acute CCl4 Intoxication. Toxicol. Lett. 1983, 17, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, Y.M.; Kosynskaya, S.I. The Use of Thiotriazoline in Patients with Chronic Liver Diseases. Zaporizhzhya Med. J. 2010, 5, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Gómez-Díaz, R.; González-Molina, Á.; Vidal-Serrano, S.; Díez-Manglano, J.; et al. Oxidative Stress, Telomere Shortening, and Apoptosis Associated to Sarcopenia and Frailty in Patients with Multimorbidity. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, Z. The Nrf2 Pathway in Liver Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 826204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Ueyama, T.; Nishi, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kawakoshi, A.; et al. Nrf2-Inducing Anti-Oxidation Stress Response in the Rat Liver - New Beneficial Effect of Lansoprazole. PLoS ONE 2014, 9(5), e97419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulou, A.; Weiskirchen, S.; Weiskirchen, R. Lipocalin 2 (LCN2) Expression in Hepatic Malfunction and Therapy. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn, J.; Fede, C.; Loneker, A.E.; Friday, C.S.; Hast, M.W.; et al. Glisson’s Capsule Matrix Structure and Function Is Altered in Patients with Cirrhosis Irrespective of Etiology. JHEP Rep. 2023, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecco, C.; Sfriso, M.M.; Porzionato, A.; Rambaldo, A.; Albertin, G.; et al. Microscopic Anatomy of the Visceral Fasciae. J. Anat. 2017, 231(1), 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, W.E. Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology and Terminologia Histologica: International Terms for Human Cytology and Histology. J. Anat. 2009, 215(2), 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benias, P.C.; Wells, R.G.; Sackey-Aboagye, B.; Klavan, H.; Reidy, J.; et al. Structure and Distribution of an Unrecognized Interstitium in Human Tissues. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 23062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S.; Murakami, G.; Ohtsuka, A.; Itoh, M.; Nakano, T.; et al. Connective Tissue Configuration in the Human Liver Hilar Region with Special Reference to the Liver Capsule and Vascular Sheath. J. Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Surg. 2008, 15(6), 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kubes, P. A Reservoir of Mature Cavity Macrophages That Can Rapidly Invade Visceral Organs to Affect Tissue Repair. Cell 2016, 165(3), 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.A.; Venkataraman, S.; Buettner, G.R. The Rate of Oxygen Utilization by Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51(3), 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Chouhan, K.; Weiskirchen, S.; Weiskirchen, R. Cellular Mechanisms of Liver Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 671640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilliams, M.; Bonnardel, J.; Haest, B.; Vanderborght, B.; Wagner, C.; et al. Spatial Proteogenomics Reveals Distinct and Evolutionarily Conserved Hepatic Macrophage Niches. Cell 2022, 185, 379–396.e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Kang, C.H.; Gou, X.; Peng, Q.; Yan, J.; et al. Quantification of Liver Fibrosis via Second Harmonic Imaging of the Glisson's Capsule from Liver Surface. J. Biophotonics 2015, 9(4), 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balog, S.; Li, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Miki, T.; Saito, T.; et al. Development of Capsular Fibrosis Beneath the Liver Surface in Humans and Mice. Hepatology 2020, 71(1), 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Asahina, K. Mesothelial Cells Give Rise to Hepatic Stellate Cells and Myofibroblasts via Mesothelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Liver Injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110(6), 2324–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozhkov, A.; Ionov, I.; Kurhuzova, N.; Novikova, A.; Katerynych, O.; et al. Vitamin A Intake Forms Resistance to Hypervitaminosis A and Affects the Functional Activity of the Liver. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2022, 41, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

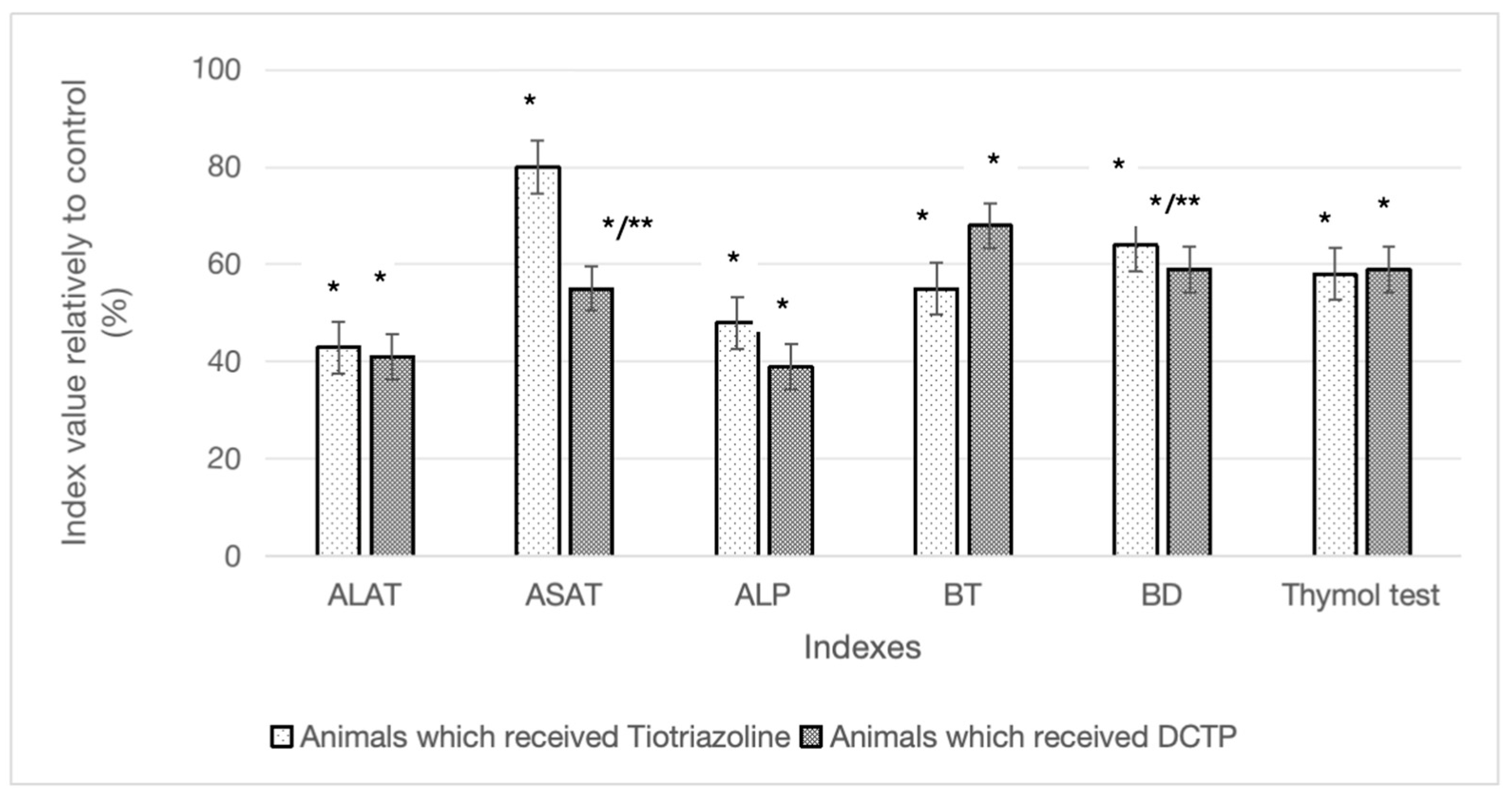

| Indicators | Experimental groups | |||

| Group I (intact) | Group II (control) | Group III (TTZ) | Group IV (DCTP) | |

| АLТ (Units/L) | 42.60±2.80 | 147.90±9.49* | 63.03±10.50*/** | 60.50±6.80*/** |

| АSТ (Units/L) | 78.10±5.30 | 162.70±12.80* | 129.50±11.49*/** | 92.70±9.80*/**/*** |

| De Ritis coefficient | 1.80±0.10* | 1.10±0.03* | 2.12±0.49** | 1.56±0.29*/**/*** |

| Alkaline phosphatase Units/L | 90.50±15.80 | 228.30±44.70* | 101.50±5.45** | 89.40±21.00** |

| Total bilirubin (mmol/L) | 9.60±1.80 | 19.18±1.80* | 10.35±1.05** | 12.90±2.10** |

| Direct bilirubin (mmol/L) | 3.30±0.10 | 5.58±0.78* | 3.56±0.19** | 3.30±0.40** |

| Thymol test (Sh) | 0.90±0.05 | 4.62±0.56* | 1.93±0.46** | 1.90±0.20** |

| Mean values and standard errors are presented, there were 10 surviving rats in the intact group, 7 surviving rats in the control group (tetrachloromethane intoxication), 8 surviving rats in the group receiving TTZ (Thiotriazoline) at a dose of 10 mg/100 g, and 10 surviving rats in the group receiving DCTP at a dose of 6 mg/100 g. *Significant difference from intact (P<0.05). **Significant difference from control (P<0.05). ***Significant difference from TTZ (P<0.05) | ||||

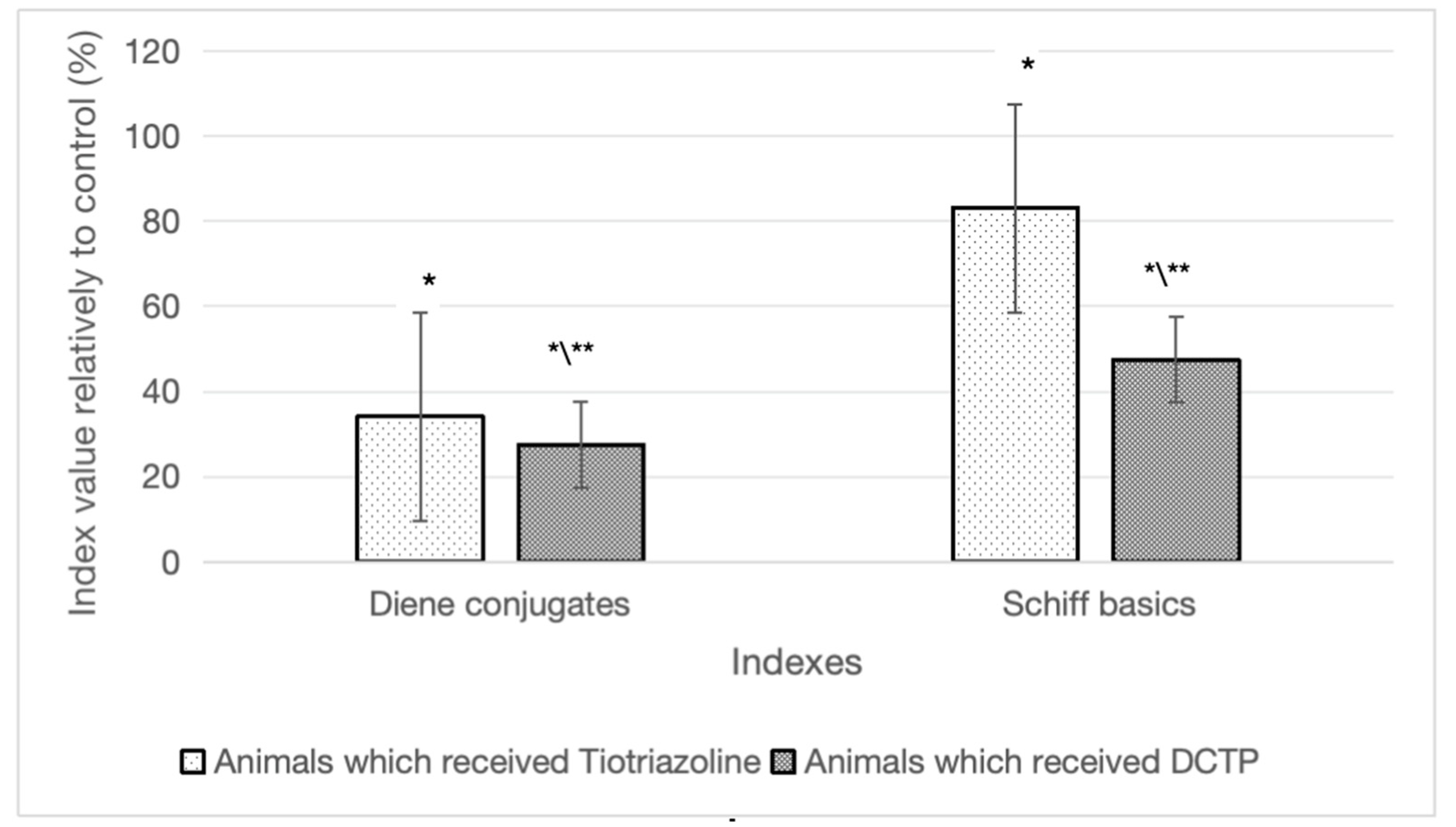

| Animal group | Diene conjugates (nmol/g) | Schiff bases (nmol/g) |

| Group I (intact) | 25.19±2.38 | 38.80±17.69 |

| Group II (control) | 48.34±1.06* | 116.00±28.33* |

| Group III (TTZ) | 34.22±2.63** | 83.11±14.94** |

| Group IV (DCTP) | 27.48±1.34**/*** | 47.56±10.67**/*** |

| The mean values and standard errors are presented. There were 10 surviving rats in the intact group, 7 surviving rats in the control group (tetrachloromethane intoxication), 8 surviving rats in the group receiving TTZ (Thiotriazoline) at a dose of 10 mg/100 g, and 10 surviving rats in the group receiving DCTP at a dose of 6 mg/100 g. *Significant difference from intact (P<0.05). **Significant difference from control (P<0.05). ***Significant difference between DCTP and TTZ (P<0.05). | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).