1. Introduction

Centuriation, or land division in equal plots is an essential feature of global impact of the Ancient Roman world to the landscape. It was formed bove ground (walls) orcut into the ground (ditches). Ancient authors such as Frontinus and Hyginus Gromaticus ) illustrate important aspects of the work of land division bydividing balks and roadways (limites) in squares or rectangles (

centuriae), which could then be subdivided to provide allotments for settlers was done by surveyors (mensores, agrimensores or gromatici) as described in the Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum [

1]. The drawing of maps to record land division was due of surveyers as it kept on part of map in teritori Lacimurgenses (Spain) [

2].

Roman colony Siscia was founded on strategical intersection near the border of the Roman provinces Pannonia and Dalmatia [

3]. Numerous documented roads were intersected in this area.

The area between Roman towns Andautonia (Šćitarjevo) and Siscia (Sisak) is long recognized as the important archaeological landscape, primarily because of the location of Roman roads between Emona, Poetovio, Andautonia and Siscia [

4]. Large part of this area is now covered in forest, known as Turopoljski lug [

5,

6]. At the end of 20

th century size of the forest was 4.337,46 ha [

8]. In the late 19

th century the size of the forest was almost two times smaller [

9] which is important for the understanding of the present level of preservation of archaeological features (

Figure 1).

Centuriation was part of the formal process of colonization, where land was conquered and divided into rectangular units, often for agricultural purposes. Most common division is in 20 by 20 actus (regular squares 710x710 m), especially in the Augustan era [

21], but could be also of other measurements such as 12x12 Forum Iulii, 21x20 Cremona, 25x16 Beneventum, or other measurements as indicated by ancient authors [

21]. The 20x20 actus produced area of 200 iugera [

22] by intersecting

limites.

Limites could be built as walls or dug up as ditches in marshy lowlands when they served also for reclamation. The remains of Roman centuriations are, as generally, so on the territory of Croatia better documented on the stone rich environment where it was marked by (dry)walls. At present, remains of centuriarion are detected on the Istrian peninsula, with azimuth of 18° [

10,

11], Zadar (Iadera), island Ugljan, Salona, Epidaurum, Tragurium, Parentium, Pola, Pharos, Cissa [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], all along the Adriatic coast. LIDAR data analysis and visualization confirm the presence of Roman land division and its remains as elevations and drywalls e.g., [19, 20].

The area in focus of our research is forests between Roman towns of Siscia and Anadutonia in the Roman province of Pannonia Superior. Siscia is Roman town since August (from 35 BC), colony status gets probably from 71. AD [

23], in same time Andautonia become municipium [

24] in Flavian urbanization of Roman province Pannonia [

25,

26]. Siscia was of vital importance since it was the starting point of the Roman colonization of the Carpathian Basin and formation of province Pannonia. It was also strategic point in the emperor Traian’s Dacian wars.

The remains of centuriation in Turopoljski lug presents first observation of Roman land division in continental Croatia, which is, unlike the coastal part, formed dy ditches and henges. This observation led to important research question whether it is part of territory of the colony of Siccia or municipium Andautonia. Question of the boundaries between two territories are in constant interest of the researches of this period in the last 100 years.

In the centuriated territory there are clusters of Noric-Pannonian tumuli as well as traces of Roman road connecting Siscia and Andautonia that were previously documented.

2. Materials and Methods

We developed a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous approach, which encompassed the visualization and analysis of LIDAR data, the examination of historical records and maps, the interpretation of aerial and orthophoto imagery, as well as a detailed review of relevant archaeological publications. This multifaceted methodology was designed to ensure the inclusion of all available data pertaining to the landscape under study.

For the observation and interpretation of tumuli and land division, we used the LIDAR dataset provided by the Croatian Geodetic Administration through the project Multisensory Aerial Survey of the Republic of Croatia for Natural Disaster Risk Assessment and Reduction. This dataset had a resolution of at least 4 points per square meter [

27]. To aid in visualization, we used the Digital Model of Relief (DMR) generated by the Croatian Geodetic Administration, which was proved to be of highly adequate quality to support both detailed observation and accurate visualization of the terrain. For these visualizations, we employed the Relief Visualization Toolbox [

28,

29,

30], which offered a variety of tools for enhancing and interpreting the data. Initially, we applied a vertical exaggeration factor of 8 to facilitate the identification of subtle topographic features. After the initial observation, the vertical exaggeration was reduced to a factor of 1 for a more realistic representation of the landscape.

Among the available visualization methods, several proved particularly effective in revealing key features. These included the Hillshade model with a 35° zenith angle and a 315° azimuth, the Multi-directional Hillshade (with 16 directions and a 20° sun elevation), the Simple Local Relief Model with a 20-meter search radius, and the slope model. These techniques provided valuable insights into the underlying topography, and were therefore selected as the most efficient for analysis. The research area spanned a significant region between Andautonia and Siscia, covering a total area of approximately 850 square kilometers. Notably, the region currently occupied by the Turopoljski lug forest extends over 4500 hectares [

31].

The study began with the observation of tumuli that had been previously published in archaeological publications on LIDAR dana visualisations. During this phase, we also noted the presence of regular lines, which led to the expansion of the initial area of focus. This expansion allowed for the discovery of additional tumuli and remains of the centuriation grid. The identification of these features was crucial for understanding the land division patterns in the area. Historical maps were also instrumental in tracing the evolution of the landscape, enabling us to track changes to the area under forest cover over the last four centuries. These maps, sourced from maps.arcanum.com and Geoportal.dgu.hr, provided valuable context for understanding the shifting toponymy of the region over time, offering further insight into how the area had been used and developed throughout history.

This multi-disciplinary approach, integrating advanced LIDAR data analysis with historical cartographic research, allowed for a comprehensive interpretation of the tumuli, land division patterns, and other archaeological features present in the landscape. It also provided a better understanding of how the region has transformed over the centuries, aiding in the reconstruction of its ancient spatial organization.

3. Results

In this analysis we detected and/or confirmed 3 important elements of Roman landscape on LIDAR data visualisations: tumuli, roads and centuriation division. Some of them are previously documented and researched, while some of them are observed for the first time. The most documented are the remains of Roman roads, then tumuli, while the remains of centuriation were completely unknown until now.

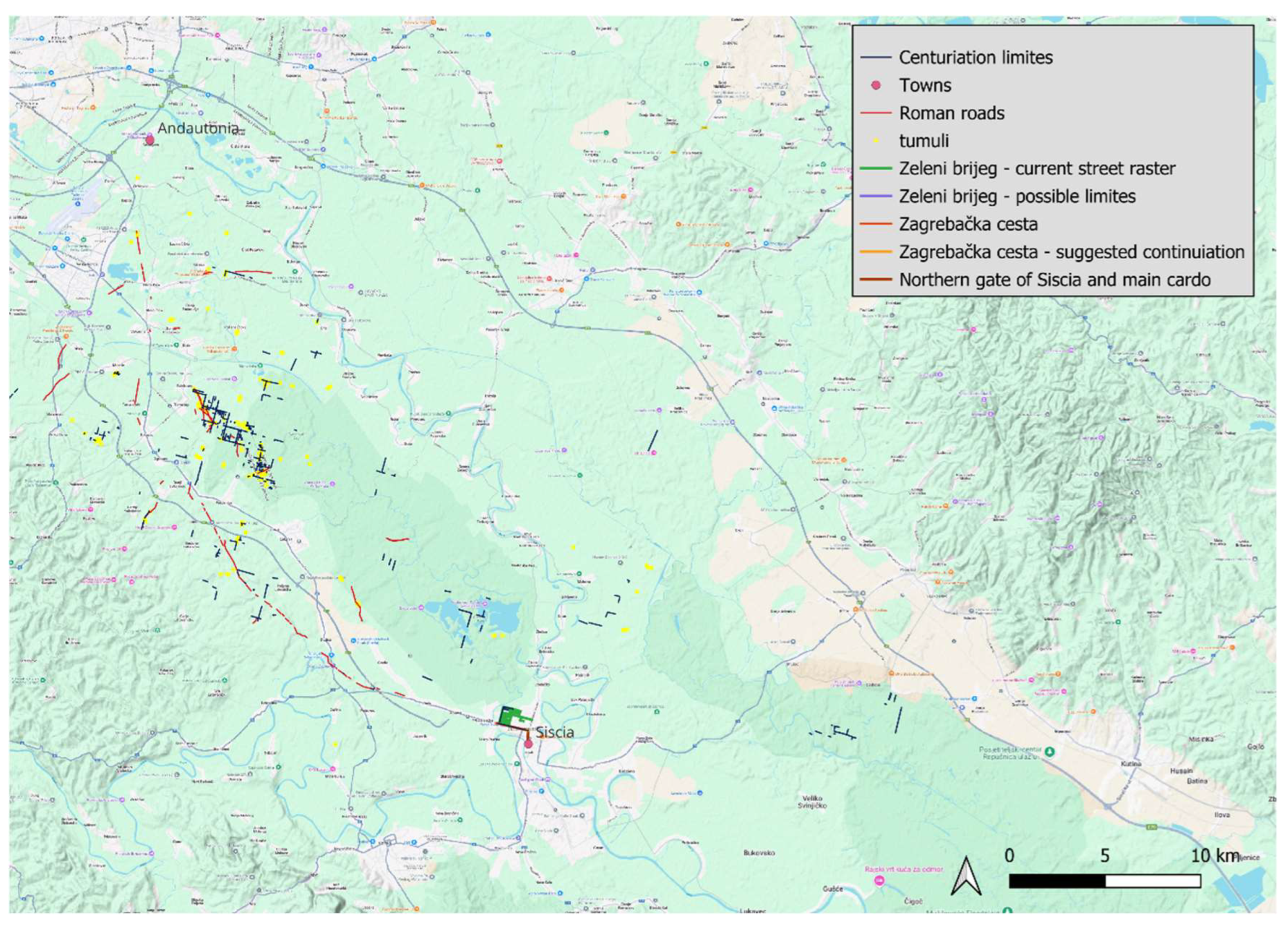

Figure 2.

The marked positions of Roman tumuli, roads and centuriation, and documented historical forest clearances area.

Figure 2.

The marked positions of Roman tumuli, roads and centuriation, and documented historical forest clearances area.

3.1. Tumuli

In Turopoljski lug 10 areas with concentration of tumuli was discovered almost 50 years ago, with the total of 104 tumuli. Concentration of tumuli is from 1 to 23 in a group [

5,

6,

7]. Six of those tumuli were excavated and all confirmed to the Roman period, from late 1

st till the beginning of 3

rd century AD [

5]. The tumuli represent specific group known by the name of Norricum-Pannonian tumuli.

The areas with preserved tumuli is confirmed on LIDAR data and field survey, while some new areas with tumuli were detected (

Figure 3-5).

Z. Gregl [

6] noted the regular concertation of tumuli group VI in parallel lines and mentions the possibility that they were aligned alongside the road, but that could not be confirmed (

Figure 4a). The space between groups he observed is line of the centuriation (

Figure 4b). On LIDAR data we recognized 389 tumuli in 32 zones (

Table 1), (

Figure 5).

3.2. Centuriation

Beside main division in squares Main squares are 710x710 m. The remains of 11 squares well preserved is marked in Turopoljski lug. On some, internal division is preserved 8x8 parts what is not traditional inner measures.

The division identified on LIDAR visualization presents a typical Roman centuriated landscape. Limites are formed by drains or ditches, frequently flanked by trees and henges [

32],

Figure 1 in that text. That is why the edges of ditches are usually elevated. Both ditches and hedges were visible on LIDAR data visualisations (

Figure 3). The inner grid are was also made by ditches and hegdes as documented elsewhere e.g., [

33] and observed in this analysis (

Figure 3,

Figure 4).

Figure 6.

The are with biggest concentration with centuriation grid and tumuli in Turopoljski lug. Visualisation Simple local relief model. Search radius 20 m.

Figure 6.

The are with biggest concentration with centuriation grid and tumuli in Turopoljski lug. Visualisation Simple local relief model. Search radius 20 m.

During the 18

th century exhaustive forest clearing was undertaken and transformed into arable land which is documented by written records, plans and topographical names. The biggest one happened in second half of 18

th century when organized deforestation took place and the new land was equally divided among Turopolje nobility [

34]. It lasted from 1776. In 1779. And as a remembrance to this big event, memorial gate was erected –

Vrata od krča (Deforstation gates). The gates were destroyed and restored several times and are now protected monument [

9]. The area that were cleared frequently are recognizable by the toponim KRČ (Croatian word for clearing forest/bush to transform into arable land same Krčevina or Kerč/ć bed noted by historical map). Historical maps prove that the areas where centuriation lines are not visible were areas where deliberate deforestation and clearances took place (

Figure 2, 7). Some are near modern villages like Buševac, Lekenik on east Krči; Poljan on east Krčevina; west from Suša Kerči, Kerčinci all on Habsburg Empire – Cadastral maps (XIX. Century) (

Figure 7a). On First Military Survey (1783–1784) Provinz Kroatien west from Veleševac is toponym Kerchevina [Mapire] (

Figure 7b). on modern map Krči Geoportal same toponym is in vicinity village Ogulinec [Geoportal].

In 1876 government approved sale of forest Kozjak [

35]. It is later mentioned as meadow, as well as big cleared areas of Krči and Vratovo [

36] which are toponyms on the areas where there are no remains of centuriation. We can conclude that the lack of centuriation remains is the result of subsequent forest clearance activities and preparation for agricultural activities. Here it is not documented, as elsewhere that the limites ditches were used in later periods, probably because for a period of time the entire area was abandoned.

The azimuth of centuriation is 15 degrees. It is worth mentioning that the streets of present day Sisak in its northern part (Zeleni brijeg), outside of the Roman town perimeter have the same inclination, while the street raster in the part of the town that was Roman Siscia have different orientation. We can conclude than that this block of land division finished at the northern entrance to Roman Siscia. The existing Zagrebačka cesta entering Sisak from the west Siscia follows that azimuth as well as Zeleni brijeg part of the town (

Figure 8). On LIDAR visualization there are some features visible that could present remains of limites since are not part of present streets and blocks.

3.2.1. Main Grid

The main grid is formed as regular rectangles dimension 710 x 710 m (most typical centuriation grid). It was formed by digging channels 4 to 10 meters wide for the main grid. On the both sides of the channels, there are remains of the elevations, so we can conclude that the henges were formed on the edges of the channels, thus forming the most typical centuriation features for the lowlands, especially marshy areas which Turpoljski lug most certainly is. A total of 425 horizontal of vertical grid lines (both main and internal) were documented in this research (

Figure 9,

Figure 10).

3.2.2. Internal Division

The internal division is visible within several main divisions. The width of the channel is 3-5 meters. It is not so well preserved in all areas, but in the central area with most finds of tumuli and main grid, there are also numerous remains of the internal division. The internal division was formed similar to main one, with channels and henges, but much more narrow (

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13).

3.3. Roads

Matija Petar Katančić in late 18

th centurydescribed the route of the Roman road from Andautonia to Siscia [

37]. In modern village of Buševec road split in two branches – one towards the west, and the other towards the southeast, in the direction of Siscia [

38]. The road was still visible in 18

th century and was called “Roman path”. Field surveys confirmed those conclusions [

38]. The branch from Buševec is visible on LIDAR visualisations, almost in continuity, till village Sela (

Figure 14), from where it is covered by the modern road till Siscia (Sisak), but the archaeological excavations preceding the reconstruction of the aforementioned road confirmed presence of Roman road [

39].

This main Roman road route is on the Western side of the best preserved part of the land division, but there are also remains (though much less numerous) to the west from this road.

Auxiliary roads – they were not made of pebbles and cobbles. In the vicinity, remains of such road were excavated [

40].

Traces of possible small auxiliary Roman roads are visible in the area. Remains of Roman auxiliary road were discovered during the rescue excavation in Donji Vukojevac, on the route of the motorway Zagre-Sisak, as well as remains of Roman rural settlement [

40]. Remains of such type of roads were also found during the excavations for the same motorway more towards the North [

41]. Elevated narrow features visible on LIDAR visualisations are therefore interpreted also as remains of auxiliary roads.

The remains of the road entering Siscia at the Northern Gate were discovered along the present day Zagrebačka cesta, confirming the direction suggested from 18

th century. This road has the same orientation as centuriation (

Figure 8). This road crosses the Odra river, close the confluence with Kupa river. In 1968, remains of the Roman bridge were discovered nearby [

42], and interpreted as bridge connecting the road leading to Andautonia [

42]. The remains of the road in the direction of N-E was found in the area of Zeleni brijeg on two places [

42] also following 15 degrees azimuth, in Roman period as today.

4. Discussion

The analysis of LIDAR datasets and historical data provide concrete evidence for interpretation of the Roman land division, centuriation. The areas where centuriation is not preserved mostly coincides with the areas that were deforested during the historical periods. as seen on historical images. LIDAR offers significant advantages in detecting and analyzing Roman centuriation, including non-invasive surveying, high-resolution data, and the ability to access hard-to-reach areas, its limitations—such as difficulties with subtle features, environmental factors, and historical changes—must be considered. Complementing LIDAR with other archaeological techniques and historical records will help overcome these limitations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of ancient land divisions. At the moment, the potential of application of LIDAR data analysis in archaeology highly overcomes potential limitations. It will take time until we reach those limitations.

This is especially clear in the research of forested and marshy areas where archaeological remains are difficult to observe using traditional methods but on the other hand, better preserved because of environmental factors. With LIDAR we can now reach areas that were out of modern infrastructure impact as well as archaeological methodology.

The land is, even though marshy, sutiable foragriculture which is confirmed through use in historical and recent periods.

If we accept the northern raster of present day Zeleni Brijeg area of Sisak and Zagrebačka street as remains of orientation from the Roman period we could suggest that the Siscia ager starting point was at the northern city walls of Siscia. Present day Zagrebačka street ends at the roundabout and the following road in the direction toward the East (Ferde Hefelea street) changes orientation. This roundabout is around 300 meters from the Northern gate to Siscia. This Northern Gate were confirmed by archaeological excavations [

45]. If we continue to follow direction of Zagrebačka street it ends precisely at the location of the Northern Gate. [

45]. The existence of the Roman road was confirmed in 2013 during archaeological rescue excavation preceding reconstruction of Zagrebačka street (39). This road today crosses the bridge across Odra river. Along the road there were finds of graves on various places (Koprivnjak 2014). Zagrebačka street is the continuation of the modern road which partly follows the route of the Roman road Andautonia-Siscia which was recognized in the early Modern Period [

37], and confirmed in 19

th and 20

th century [

4,

38] (

Figure 15).

The azimuth of our centuriation does not follow neither Andautonia [] or Siscia azimuth []The azimuth of street raster of municipium Siscia is 5 degrees.

The orientation of the town and its ager does not have to be (or usually is not) the same. [

46]. Both cities and land are planned according to specific characteristics of the city structure demands or local topography, relations with surrounding areas and also astronomical aspects. [

46]. Around some towns are even several different orientations of land. It is common practice that the orientation of the city does not match orientation of the

ager. [

46]. Also, orientation of centuriation of two different towns is usually different. One of the rare opposite examples, where there are the same is between Parentium and Pola on Istrian peninsula [

11].

The suggested area of Andautonia ager stretches up to village of Lekenik, in the area where LIDAR data confirmed presence of centuriation with 15 degrees azimuth [

43]. This research was concentrated on the area south of Sava river, and confirms for that area that the azimuth was different (15 degrees as mentioned here). Considering all this data we can suggest that the border between Siscia and Andautonia ager is somewhere to the north of the suggested line. Since there are no undisputable traces detected so far of 15 degrees centuriation north of village Ribnica, it is to early to hypothesize whether the ager of Andautonia started only north of the city perimeter. Kadi places eastern edge of the Andautonia ager at the village Orli [

43], but the western edge is deep in 15 degrees azimuth, in our opinion, Siscia ager and should be placed at least 6 km in the direction of NW concerning current data (

Figure 15). The eastern edge of the Siscia ager is yet to be determined since the traces of centuriation reach at least village Osekovo which is the distance of 18 km from Siscia.

The practice of detecting centuriation through analysis of modern infrastructure was proven efficient and in use e.g., [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Therefore we accept Kadi suggestion of 22,5 asimuth of Andautonia centuriation, especially since partly confirmed by geophysical research and archaeological excavation [

43,

44]. The focus on future research should be to find the border zone between two agers.

This research could also have implications for some of the traditional general knowledge about the are, for examplethe famous cattle bread bear the name of the Turopolje (tur) and is traditionally regarded as remains of auroch. The fact that this area was cultivated land during Roman period call for re-evaluation of this knowledge, since this data clearly shows that the area was not covered in forest in all periods..

Turopolje is often mentioned as very swampy densely forested area until the melioration in 19

th century, while the elevated Roman roads were the only passable areas [

52]. It is clear now that during the Roman period the area was agricultural land, and numerous ditches forming inner and main divisions were probably part of complex water regulation system because of the topographical characteristics of the area. First mention of Turopolje forest as a forest dates from 1217 [

35].

In this case, centuriation system, with all its advantages as efficient drainage system was not later in use. Floods were frequent and the area is “famous” for it. There are numerous documented cases where Roman centuriation system was later in use and constantly maintained, especially in the marshy enmironment [

50,

53], but not in this case. Current forest division visible on aerial and satellite photos does not follow Roman land division.

After Roman period the land division is abandoned. The excavated tumuli are dated from late 1

st century till early 3

rd century[

5]. Most of the tumuli respect the centuriation limites. Only some of them are in the inner part. This could mean that these parts were used specifically for burial areas or that the land could have been gradually abandoned and its function replaced. The Turopolje after Roman period became densely forested space and in tradition those forests are called “Prehistoric forests”. The kind of isolation reflects in the fact that the forests were regarded as a possible refugia for late remaining aurochs between Roman period and Middle Ages. Archaeogenetical analysis in the future should conclude whether there were aurochs in historical periods in the region. Abandoned forested places that were only again cleared up for agriculture in the Early modern period could reflect the special relations later inhabitants had with these visible burials in the environment – area of the dead. Slav toponims Trebarjevo and Veleševec (from Veles, in Slavic mythology god of the could support that interpretation.

5. Conclusions

Based on the analysis of LIDAR data, it is evident that the centuriation discovered in the Turopoljski lug forest is linked to the land division of Roman colony Siscia. Our preliminary findings suggest that the remains of the centuriation, combined with the current street layout and orientation in Sisak, point to the land division of Siscia. The centuriation pattern detected in the forest of Turopoljski lug is most likely part of the larger colonial land division structure of Siscia. The alignment of the visible remnants of centuriation, when considered alongside the modern street grid, strongly supports the idea that they belong to Siscia’s ancient land division. The position and alignment of the current centuriation remains observed in Sisak further confirm its association with the Roman colony of Siscia. Considering Siscia’s role as a Roman colony, its high-ranking status among provincial authorities helps explain the sophisticated land divisions, such as the centuriation found in Turopoljski lug. LIDARdata analysis is proven as highly powerful tool for observation and analysis of Roman landscapes as well as better understanding of relations between towns.

Supplementary Materials

All materials are presented in the text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K., B.Š. and R.Š.K.; methodology, B.Š., H.K. and R.Š.K.; investigation, R.Š.K., B.Š. and H.K.; resources, R.Š.K., B.Š. and H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Š.K., B.Š. and H.K.; writing—review and editing, H.K, B.Š. and R.Š.K.; funding acquisition, R.Š.K., H.K. and B.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Croatian Science Foundation, IP-2024- 05-1598, Istraživanje prostornog planiranja u neolitiku Slavonije neinvazivnim arheološkim metodama and Sinergija različitosti: arheologija krajolika i tehnološke tradicije u Kontinentalnoj i Jadranskoj Hrvatskoj (SirAkt).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Campbell, B. (2000). The Writings of the Roman Land Surveyors. Introduction, Text, Translation and Commentary. Journal of Roman Studies Monographs 9. London.

- Campbell, B. 1995. Shaping the rural environment: surveyors in ancient Rome', JRS 86 (1996), 74-99.

- Durman, A. O geostrateškom položaju Siscije. Opvscvla archaeologica, 1992, 16, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Klemenc, J. Archeologische Karte von Jugoslawien, Blatt Zagreb 1938 Beograd.

- Koščević & Makjanić (1986/1987). Antički tumuli kod Velike Gorice i nova opažanja o panonskoj radionici glazirane keramike. Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu, 3/4 (-), 25-70. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/1074.

- Gregl, Z. 1990, Noričko-panonski tumuli u Hrvatskoj, Izdanja Hrvatskog arheološkog društva, 14, 101–109.

- Gregl, Z. 1990. Turopolje. Arheološki pregled, 9 (1988), Ljubljana, 250-252.

- Tustonjić, A. , Pavelić, J., Farkaš-Topolnik, N., Đuričić-Kuric, T. 1999. Šume unutar prostornog plana Zagrebačke županije. Šumarski list 9-10. 469-485.

- Župetić, V. Povijest nastanka i očuvanja Vrata od Krča u Turopoljskom lugu. Godišnjak zaštite spomenika kulture Hrvatske, 2021, 45, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bulić, Davor Rimska centurijacija Istre // Tabula (Pula), 10 (2012), 50-74. [CrossRef]

- Bulić, Davor Rimska ruralna arhitektura Istre u kontekstu ekonomske i socijalne povijesti / Matijašić, Robert (mentor). Zadar, Odjel za arheologiju, 2015.

- Bradford, J. (1947) A Technique for the Study of Centuriation, Antiquity, XXI, pp. 197-204.

- Bradford, J. (1957) Ancient Landscapes. Studies in Field Archaeology. London, Bell.

- Suić, M. 1. (1956). Limitacija agera rimskih kolonija na istočnoj jadranskoj obali: -Zbornik radova Instituta za historijske nauke u Zadru, 1. Zadar.

- Chevallier, R. (1961) La centuriazione romana dell'Istria e della Dalmazia (The Roman centuriation of Istria and Dalmatia). Atti e Memorie della Società Istriana di Archeologia e Storia Patria, Vol. 9, pp. 11-24.

- Ilakovac, B. (1997). Land division of the Roman ager at Cissa on the island of Pag. Vjesnik Arheološkog muzeja u Zagrebu, 30-31 (1), 81-82. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/25333.

- Kadi, M. 2016. Centurijacija otoka Ugljana : rimski katastar = The centuriation of the island of Ugljan : the Roman land division, Zadar : Sveučilište ; Preko : Općina.

- Kadi, M. 2019. Centurijacija otoka Ugljana. Kartografija i geoinformacije, 18 (31), 98-107. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/222073.

- Popović, Sara ; Bulić, Davor ; Matijašić, Robert ; Gerometta, Katarina ; Boschian, Giovann Roman land division in Istria, Croatia: historiography, LIDAR, structural survey and excavations // Mediterranean Archaeology & Archaeometry, 21 (2021), 1; 165-178. [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, Federico. (2023). Rediscovering the Lost Roman Landscape in the Southern Trieste Karst (North-Eastern Italy): Road Network, Land Divisions, Rural Buildings and New Hints on the Avesica Road Station. Remote Sensing. 15. [CrossRef]

- Romano, David. (2013). The Orientation of Towns and Centuriation. [CrossRef]

- Dilke, O.A.W. 1971. The Roman land surveyors. An introduction to the Agrimensores. Newton Abbot: David and Charles.

- Hoti, M 1992. Sisak u Antičkim izvorima. Opuscula archaeologica. 16 (1), 133-163.

- Kušan Špalj, D. and Nemeth-Ehrlich, D. 2003. Municipium Andautonia, in M. Šašel Kos and P. Scherrer (eds) The Autonomous Towns of Noricum and Pannonia / Die autonomen Städte in Noricum und Pannonien, Pannonia I (Situla 41), Ljubljana 2003: 107–117.

- Kovacs, P. (2013). Territoria, pagi and vici in Pannonia. In W. Eck, B. Fehér, & P. Kovács (Eds.), Studia Epigraphica in memoriam Géza Alföldy (pp. 131–153). Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH.

- Sokol 1981 Vladimir Sokol, Najnovija arheološka istraživanja u Prigorju, in: Arheološka istraživanja u Zagrebu i njegovoj okolici, IzdHAD 6, Zagreb, 169-185.

- DGU LIDAR https://dgu.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/Istaknute%20teme/Multisenzorno%20snimanje/LiDAR%20snimanje%20iz%20zraka.

- Kokalj, Ž. , Somrak, M. 2019. Why Not a Single Image? Combining Visualizations to Facilitate Fieldwork and On-Screen Mapping. Remote Sensing 11(7): 747.

- Zakšek, K. , Oštir, K., Kokalj, Ž. Sky-View Factor as a Relief Visualization Technique. Remote Sensing 2011, 3, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokalj & Čonč 2023 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371226392_QGIS_Relief_Visualisation_Toolbox_plugin_AARG_Online_workshop_25_May_2023.

- Beuk, Josip; Rončević, Juraj; Drvodelić, Damir 2023 Turopoljski lug: file:///C:/Dropbox/DOWNLOADS/beuk-2023-turopoljski_lug_blago_turopolja-sumfak_3386-publishedversion-he2lpu-s.

- Caravello, G. U., & Michieletto, P. (1999). Cultural Landscape: Trace Yesterday, Presence Today, Perspective Tomorrow For “Roman Centuriation” in Rural Venetian Territory. Human Ecology Review, 6(2), 45–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24707056.

- Kremenić, T. , Varotto, M., & Ferrarese, F. (2024). Forgotten Ecological Corridors: A GIS Analysis of the Ditches and Hedges in the Roman Centuriation Northeast of Padua. Sustainability, 16(20), 8962. [CrossRef]

- Dubravica, B. 1997. Turopoljsko plemstvo poslije ukidanja kmetstva. Narodno sveučilište Velika Gorica & Plemenita općina Turopoljska.

- Kolar Dimitrijević, M. 2008. Kratak osvrt na povijest šuma Hrvatske i Slavonije od 1850. godine do Prvoga svjetskog rata. Ekonomska i ekohistorija 4. 71-93.

- Božić, A. 2016. Magna Silva Turopoljski lug. Knjiga 1.

- Katančić, Matija Petar (1795), Specimen philologiae et geographiae Pannoniorum in quo de origine lingua et literatura Croatorum, simul de Sisciae, Andautonii, Nevioduni, Poetovionis urbium in Pannonia olim celebrium et his intriectarum via militari mansionum situ disseritur auctore Math. Petro Katancsich in Archigymn. Zagreb. schol. human. professore p. o., Zagrabiae: Typis Episcopalibus.

- Knezović, I. (2008). Katančićev Andautonij: vrhunac znanstvenog istraživanja arheologije i stare povijesti na zagrebačkom području u 18. st.. Radovi Zavoda za hrvatsku povijest Filozofskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, 40 (1), 11-47. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/49036.

- Koprivnjak, V. 2014. Sisak-Zagrebačka ulica. Hrvatski arheološki godišnjak 10/2013. 278-280.

- Dizdar, M., Tonc, A. & Ložnjak Dizdar, D. (2011). Zaštitna istraživanja nalazišta AN 6 Gornji Vukojevac na trasi auto-ceste Zagreb – Sisak, dionica Velika Gorica jug – Lekenik. Annales Instituti Archaeologici, VII (1), 61-64. Retrieved from https://hrcak.srce.hr/89817.

- Bugar 2009 Aleksandra Bugar, Šepkovčica, Hrvatski arheološki godišnjak 5/2008, Zagreb, 2009: 269 – 273.

- Vrbanović, S. - Prilog proučavanju topografije Siscije. IzdHAD, 6/1981: 187-199.

- Kadi, M. (2021). Centurijacija andautonijskog agera, Rimski katastar. Kartografija i geoinformacije, 20 (35), 77-91. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/307190.

- Groh, S. (2014). Novosti u urbanizmu municipija Andautonije-Ščitarjevo (Gornja Panonija, Hrvatska): analiza i arheološko-povijesna interpretacija geofizičkih mjerenja iz 2012. godine. Vjesnik Arheološkog muzeja u Zagrebu, 46 (1), 89-113. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/117906.

- Lolić, T. 2022 Urbanism of Roman Siscia. Interpretation of Historical and Modern Maps, Drawings and Plans. Archaeopress Roman archaeology, 89. Archaeopress, Oxford.200 p, 263 figs, 2 maps. ISBN 978-1-78969-623-3.

- Rodríguez-Antón, A.; Magli, G.; González-García, A.C. Between Land and Sky—A Study of the Orientation of Roman Centuriations in Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, D.G. , Tolba, O. 1996. Remote Sensing and GIS n the Study of Roman Centuriation in the Corinthia, Greece. Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 28.

- Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Roman Centuriation in Satellite Images. Philica, 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Dell'Acqua et al., "A landscape archaeology application of “big heritage data”: Detecting traces of Roman centuriations in large-scale, old aerial photos," 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 2015, pp. 3080-3082. [CrossRef]

- De Haas, T. 2017 Managing the marshes: An integrated study of the centuriated landscape of the Pontine plain, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports,15, 470-481. [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, Federico & Vinci, Giacomo & Forte, Emanuele & Mocnik, Arianna & Višnjić, Josip & Pipan, Michele. (2021). Integrating Airborne Laser Scanning and 3D Ground-Penetrating Radar for the Investigation of Protohistoric Structures in Croatian Istria. Applied Sciences. 11. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Latinčić, D, Regan, K. 2021. Turopljske utvrde. Studia lexicographica 15 (2021) 29, 7-49.

- Sevink, Jan & de Haas, Tymon & Bakels, Corrie & Alessandri, Luca & Mario, Francesco. (2023). The Pontine Marshes: An integrated study of the origin, history, and future of a famous coastal wetland in Central Italy. The Holocene. 33. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Position of theTuropoljski lug forest on the map of Europe.

Figure 1.

Position of theTuropoljski lug forest on the map of Europe.

Figure 3.

Archaeological (VAT) general terrain RWT isualization (a) and Multi-direction hillshade (number of directions:16, sun elevation: 20) of tumuli group VI according to [

6]. The horizontal and vertical limites are visible between tumuli.

Figure 3.

Archaeological (VAT) general terrain RWT isualization (a) and Multi-direction hillshade (number of directions:16, sun elevation: 20) of tumuli group VI according to [

6]. The horizontal and vertical limites are visible between tumuli.

Figure 4.

Tumuli and centuriation in Turopoljski lug a) sketch by Gregl [

6]; (b) Hillshade isualization (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth).

Figure 4.

Tumuli and centuriation in Turopoljski lug a) sketch by Gregl [

6]; (b) Hillshade isualization (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth).

Figure 5.

Previously undocumented tumuli in Turopoljski lug discovered by LIDAR data analysis and confirmed by field survey.

Figure 5.

Previously undocumented tumuli in Turopoljski lug discovered by LIDAR data analysis and confirmed by field survey.

Figure 7.

(a) Lekenik Turopoljski, Habsburg Empire – Cadastral maps (XIX. Century) Arcanum with toponimy Stari Krč and Novi Krč; (b) First Military Survey (1783–1784) Arcanum – toponimy Novi Krč.

Figure 7.

(a) Lekenik Turopoljski, Habsburg Empire – Cadastral maps (XIX. Century) Arcanum with toponimy Stari Krč and Novi Krč; (b) First Military Survey (1783–1784) Arcanum – toponimy Novi Krč.

Figure 8.

The street raster of Northern part of Siscia.

Figure 8.

The street raster of Northern part of Siscia.

Figure 9.

Visible traces of ditch and hinge of main limites in Turopoljski lug.

Figure 9.

Visible traces of ditch and hinge of main limites in Turopoljski lug.

Figure 10.

Tumuli and centuriation grid. Visualisation Sky-View Factor. R20 D 23 A270. 20 m search radius in 23 directions with 270° azimuth.

Figure 10.

Tumuli and centuriation grid. Visualisation Sky-View Factor. R20 D 23 A270. 20 m search radius in 23 directions with 270° azimuth.

Figure 11.

Turopoljski lug the best preserved part of centuriaction, (a) Hillshade isualization (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth); (b) plotted main limits, internal divisions and auxiliary roads.

Figure 11.

Turopoljski lug the best preserved part of centuriaction, (a) Hillshade isualization (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth); (b) plotted main limits, internal divisions and auxiliary roads.

Figure 12.

Turopoljski lug the best preserved part of centuriaction, Hillshade visualisation (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth); (a) plotted main limits, internal horizontal divisions and auxiliary road (b) plotted main limits, internal vertical divisions.

Figure 12.

Turopoljski lug the best preserved part of centuriaction, Hillshade visualisation (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth); (a) plotted main limits, internal horizontal divisions and auxiliary road (b) plotted main limits, internal vertical divisions.

Figure 13.

Turopoljski lug the best preserved part of centuriaction, Hillshade visualisation (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth, with remains of tumuli, main centuriation limites (on left side probably with original depth), inner division and the auxiliary road.

Figure 13.

Turopoljski lug the best preserved part of centuriaction, Hillshade visualisation (35° zenith angle, 315° azimuth, with remains of tumuli, main centuriation limites (on left side probably with original depth), inner division and the auxiliary road.

Figure 14.

Position of the Roman road Andautonia – Siscia on Archaeological map from Klemenc 1938.

Figure 14.

Position of the Roman road Andautonia – Siscia on Archaeological map from Klemenc 1938.

Figure 15.

The marked positions of Turopoljski lug forest (1), Andautonia, Siscia, Roman roads (red), centuriation (blue) tumuli (yelow).

Figure 15.

The marked positions of Turopoljski lug forest (1), Andautonia, Siscia, Roman roads (red), centuriation (blue) tumuli (yelow).

Table 1.

Number of tumuli in Turopoljski lug.

Table 1.

Number of tumuli in Turopoljski lug.

| Reference |

number of tumuli |

number of areas with tumuli |

| Koščević Makjanić 1986 |

49 |

4 |

Gregl 1990

LIDAR data 2024 |

104

389 |

10

32 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).