1. Introduction

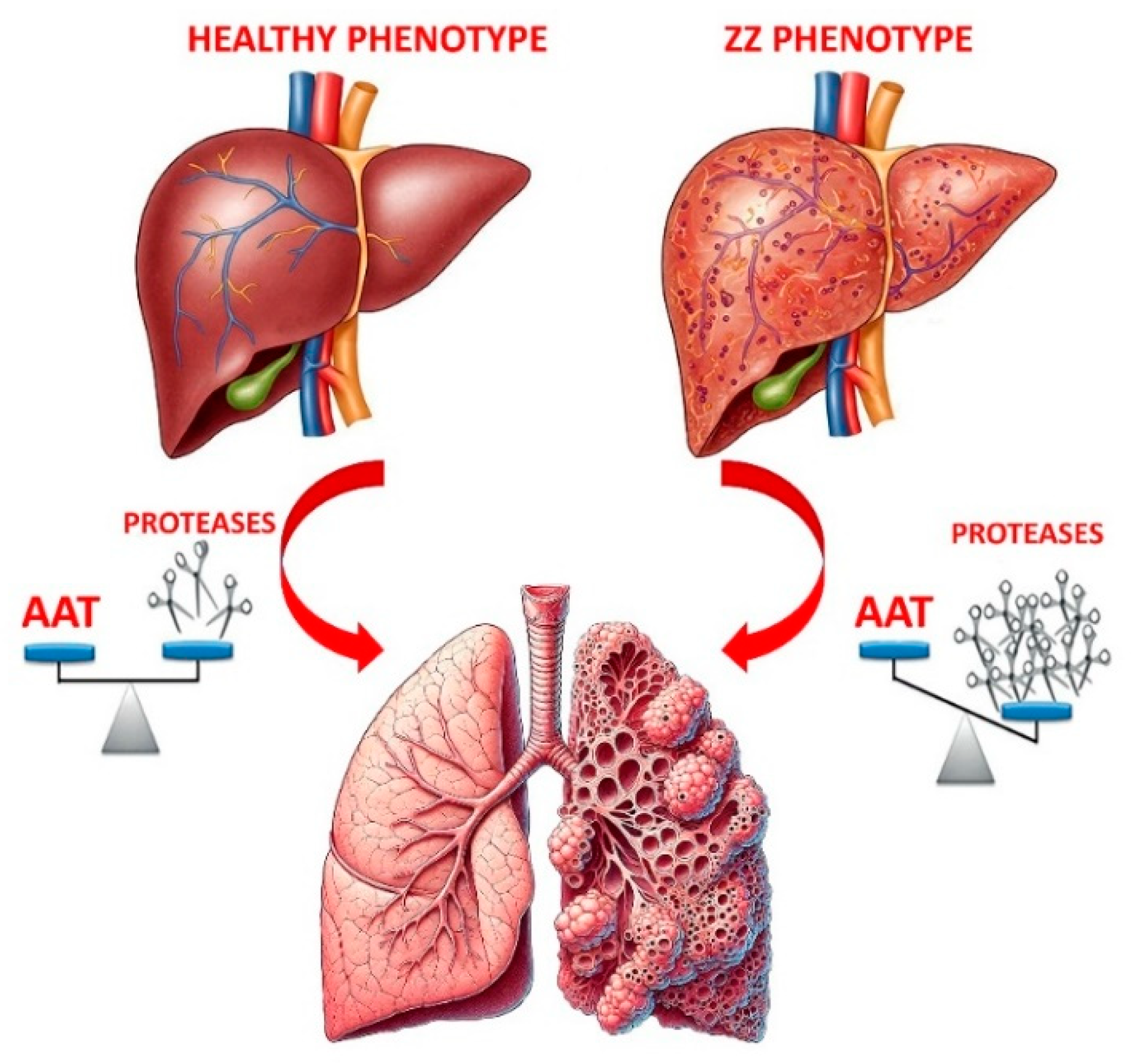

α1-antitrypsin (AAT) is a liver-produced single-chain glycoprotein, synthesized as a 418-amino-acid precursor, that enters the bloodstream to protect tissues from the damaging effects of harmful proteases [

1,

2]. AAT is particularly specific for human neutrophil elastase (HNE), released by neutrophils during inflammation, but also inhibits other proteases, including metalloproteases, cathepsin G, proteinase 3, and cysteine and aspartic proteases [

3]. Encoded by the SERPINA1 gene, also called the Pi gene, located on chromosome 14 (14q31–32.3), AAT belongs to the serpin superfamily. Currently, over two hundred SERPINA1 variants have been identified, most resulting from point mutations in the gene sequence that lead to amino acid substitutions [

4,

5]. Several substitutions may affect the electrophoretic mobility of the protein thus allowing these variants to be detected by isoelectric focusing (IEF). They are labelled A to Z if their electrophoretic mobility is faster or slower, respectively, compared to that of the most common variant, labelled M [

4]. The M variant (normal variant) is not pathogenic, and individuals homozygous for this variant (referred to as Pi*MM individuals) show normal AAT function and serum levels. The most frequent pathogenic AAT variants are the S (c.863A>T; p.Glu288Val) and Z (c.1096G>T; p.Glu366Lys) variants, which express, respectively, approximately 50–60% and 10–20% of normal AAT levels. The MM, MS, MZ, SS, SZ and ZZ protein phenotypes account for >99% of all variants [

6]. The Z-AAT mutant (and other rare pathogenic variants) predispose to liver disease and/or to a lung disorder known as α1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). If liver disease is caused by the accumulation of this variant as polymeric chains in hepatocytes [

7], the low AAT levels in blood and lungs result in an unbalance between proteinases and anti-proteinases [

8,

9]. This can cause structural changes in lung parenchyma, leading to lung conditions such as bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema [

10,

11,

12,

13]. AATD is a genetically inherited disorder usually diagnosed through serum protein concentration measurement and the identification of allelic variants via phenotyping or allele-specific genotyping [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, the intrinsic complexity of the disorder, and the variety of genetic forms result in significant clinical variability, even among individuals with the same genetic form and similar AAT blood levels.

Thus, AATD often goes unrecognized/underdiagnosed in clinical practice [

19,

20], which is concerning since unchecked deficiency leads to ongoing lung proteolysis, elastin degradation, and alveolar damage. It is well established that individuals diagnosed with AATD before the onset of pulmonary symptoms typically have better outcomes than those diagnosed at later stages when respiratory illness is already in progress. Mass Spectrometry (MS), a powerful analytical tool, is emerging in this context as a promising approach for identifying and quantifying proteins and peptides involved in AATD, potentially improving early detection of disease biomarkers and patient outcomes [

21].

This report aims to update on emerging proteomic techniques for the detection of AATD biomarkers and of common deficiency alleles, S and Z, linked with AATD.

2. Introducing α1-antitrypsin Deficiency (AATD) and Potential Treatments

As noted, AATD is an inherited genetic disorder leading to low circulating levels of AAT, the primary systemic antiproteinase that protects the lungs. Reduced AAT production raises the risk of serious health issues, from liver damage to respiratory symptoms (see

Figure 1).

Liver disease severity varies widely among AATD patients, with liver transplantation being the only available specific treatment. Respiratory disorders are typically chronic cough, shortness of breath and wheezing, resembling emphysema. AATD has no cure, but available treatments, while not being able to reverse lung damage, can offer symptom relief and prevent further harm. Augmentation therapy is the primary treatment specific for lung disease., It consists in the raise of AAT levels by infusing directly into bloodstream purified AAT from healthy blood donors [

22]. This therapy, typically administered weekly, is reserved for individuals with the lowest AAT levels. Although it aims to reduce lung density loss thus slowing disease progression, its efficacy remains debated [

23]. Additional treatments, such as bronchodilators and oxygen therapy reduce inflammation and open airways thus making breathing easier. Other potential strategies, including gene therapy and the use of induced pluripotent stem cells, are under investigation [

16].

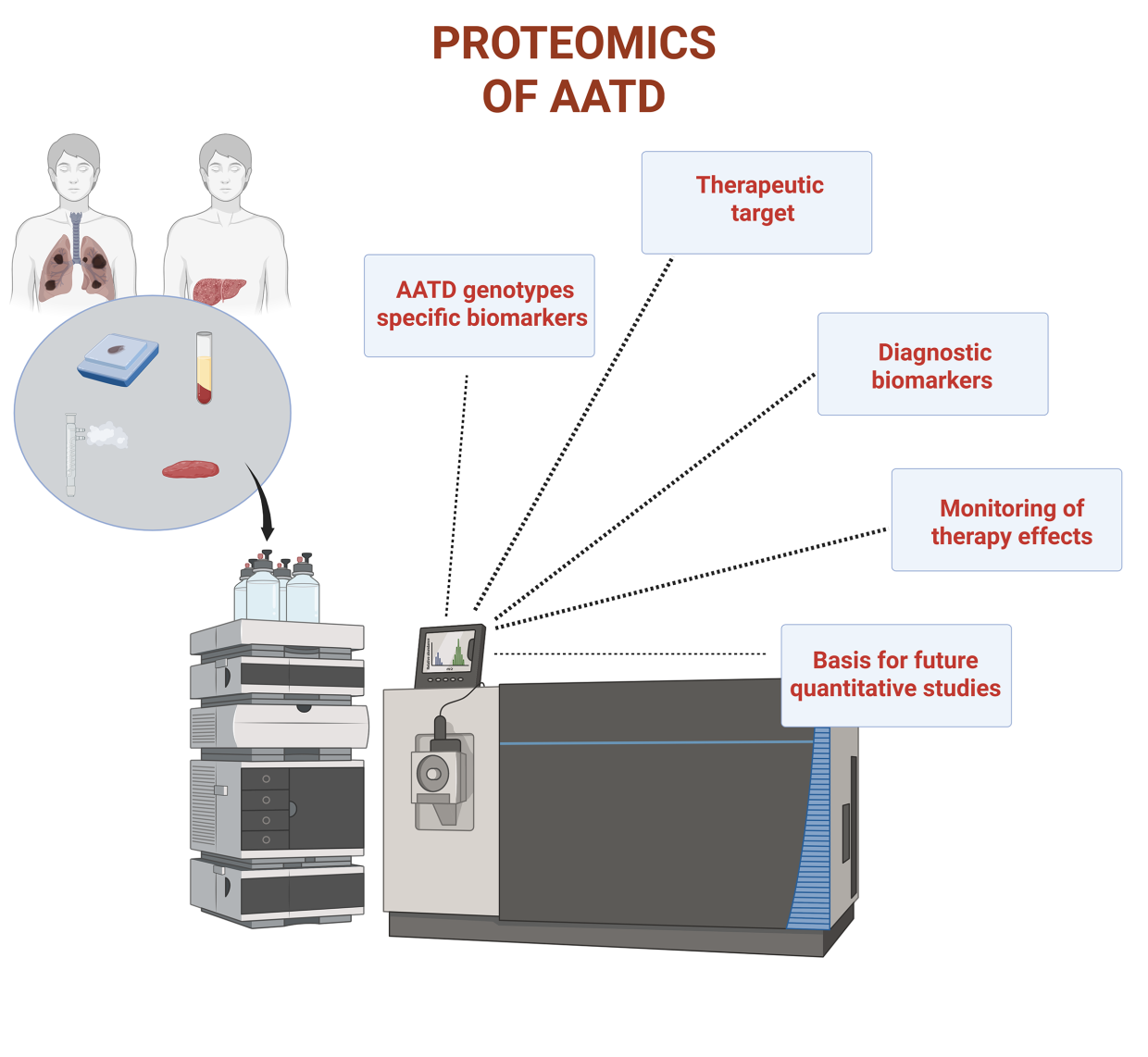

3. Proteomics and Biomarker Discovery

Since early AATD symptoms are often mild and overlap with those of other illnesses, the diagnosis of this disorder may be delayed. Testing for AATD patients with liver symptoms or those diagnosed with COPD could improve the rate of early diagnosis [

19]. A significant advancement in diagnostic and therapeutic technologies may lead to the identification in body fluids or tissues of molecular markers that can efficiently and accurately detect early stages of disorders. Of great interest could also be biomarkers whose level responds to medical treatments. Their use in clinical trials allows monitoring the progression of patient condition and understanding changes in patient’s clinical outcome [

24].

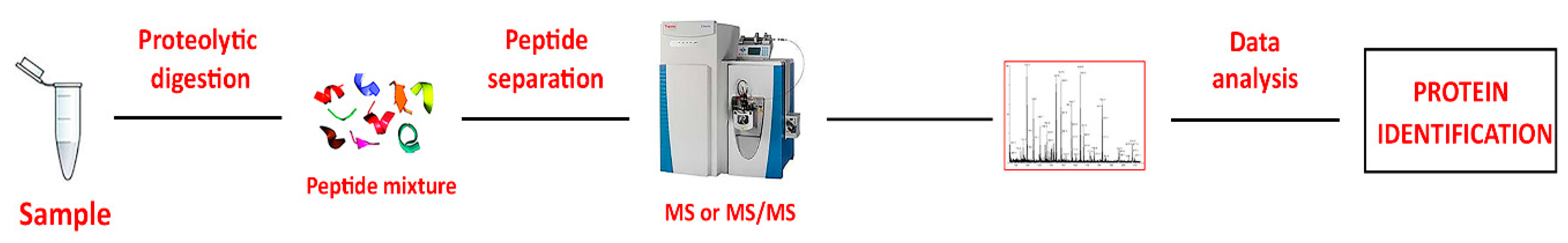

Proteomic analysis using liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [

25] is currently the most widely used method for biomarker discovery. Its high sensitivity and specificity have enabled the identification of numerous potential protein biomarkers for various diseases [

25]. The rationale for this choice is that all disorders are characterized by molecular alterations that often precede clinical manifestations by a considerable time. Thus, the focus of most clinical proteomics studies is the capture of differences in relative protein abundance under different conditions. The so-called “Bottom-up” methods (

Figure 2) are widely used in proteomics for protein identification. In this approach, all proteins in a sample are digested with a protease, typically trypsin, generating a mixture of peptides. These peptides are then separated via liquid chromatography (LC), and their sequences are acquired using MS/MS. Subsequent analysis with advanced software tools for database searching of MS/MS data enables accurate identification and quantification of the proteins from which the peptides originated [

26].

Current proteomic technologies have yielded significantly advancements in our understanding of biological mechanisms underlying health and disease, paving the way for enhanced patient care.

4. Application of Proteomics to AATD

AATD is the most common genetic cause of emphysema and is characterized by unexplained phenotypic heterogeneity among affected individuals [

6]. Due to the diversity of pathogenic mutations, there is limited guidance on monitoring and treating patients when the clinical significance of variants is unknown. To explore the origins of this heterogeneity, Serban et al. [

27] analyzed plasma/serum samples from 5,924 subjects across four independent cohorts, including a large COPD population and three AATD groups. Using the SomaScan V4.0 platform, a multiplex proteomic technology recognized for its reproducibility [

28], the authors aimed to identify new plasma biomarkers for AATD-associated emphysema correlated with clinical outcomes. With the support of different statistical methods, their analysis revealed highly sensitive and specific biomarkers that identified severe- (PiZZ), intermediate- (PiSZ), and mild-deficient (PiMZ) genotypes. Detection of the less severe genotype (PiMS) was lower due to the similarity of AAT levels with those of the normal variant PiMM. They also uncovered unique and shared plasma biomarkers between AATD and COPD patients and identified proteins associated with emphysema in both groups. Specifically, PiZZ patients displayed biomarkers linked to diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and emphysema. Additionally, the results confirmed the elevation of AAT to near-normal levels in PiZZ individuals undergoing augmentation therapy.

Beiko et al.[

29] conducted the quantitative lung computed tomography (CT) unmasking emphysema progression in AATD study (QUANTUM-1) to identify proteomic signatures associated with emphysema progression in patients with severe AATD but normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). Aim of this research was the identification of serum proteins that correlated with CT density decline. The analyses carried out on a cohort of 31 early-stage AATD-associated COPD patients revealed four serum proteins (C-reactive protein, CRP; adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein, AFBP; leptin and tissue plasminogen activator, tPA) correlated with baseline emphysema. After adjustments (e.g. for age and sex) all but leptin were linked to body mass index (BMI) and also to emphysema progression, making these proteins potential therapeutic targets for COPD.

Liver disease in AATD follows a biphasic pattern, peaking in early childhood and adulthood. Karatas et al. [

30] applied proteomic analysis to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) liver tissues to investigate factors underlying adult AATD-related liver disease. They compared samples from eight PiZZ patients (four pediatric, four adult) who underwent liver transplantation with those from healthy controls (three pediatric, four adult). Proteins differentially expressed between pediatric and adult patients were obtained by laser microdissection of hepatocytes and revealed by MS. Among 65 proteins upregulated exclusively in adult PiZZ samples, four members of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family (PDIA4, PDIA3, P4HB, and TXNDC5) were identified. Notably, PDIA4 appeared a good therapeutic target, since its inhibition by cysteamine reduced Z-aggregate formation and its silencing lowered oxidative stress, a feature of AATD-mediated liver disease. This suggested that PDI inhibition is a potential therapeutic approach for AATD treatment.

Ohlmeier et al. [

31] applied two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE) and MS to perform a proteomic study on lung tissues from AATD; idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients, along with nonsmokers, healthy smokers, and smokers with COPD at varying severity. Their study revealed disease-specific protein changes in AATD, IPF, and COPD, with findings transferred from lung tissue to more accessible sputum and plasma samples. The discovery that transglutaminase 2 (TGM2) was increased across all sample types supports its potential as a target for diagnosing and treating AATD-associated COPD.

Building on the observation that patients without AATD typically develop COPD later in life than those with the condition, Murphy et al. [

32] explored whether the absence of plasma AAT could influence the neutrophil characteristics of COPD phenotypes, whether or not they are associated with AATD. Given the established binding of AAT to neutrophil plasma membranes, specifically within membrane lipid rafts [

33], an intriguing question arises: could exogenous AAT administered through augmentation therapy to AATD-COPD patients bind to circulating AATD neutrophils, potentially shifting their phenotype towards that observed in non-AATD-COPD? To explore the potential consequences of altered membrane protein expression on neutrophil function and to assess the impact of AAT augmentation therapy, the authors compared the plasma membrane proteomes of neutrophils from individuals with AATD-COPD to those from non-AATD-COPD patients. The focus on the neutrophil plasma membrane stems from its role as the interface between the cell and its environment, which plays a crucial role in determining how a cell responds to stimuli. A label-free MS/MS proteomic analysis of plasma membranes from neutrophils of AATD- and non-AATD-COPD patients identified an average of 860 proteins. Among the 15 proteins that were differentially expressed between the two groups, eight (including myeloperoxidase, MPO, and bactericidal/permeability increasing protein, BPI) were found to be more abundant in the plasma membrane fractions of AATD-COPD patients compared to non-AATD-COPD patients. These results suggest that AAT augmentation therapy influences the membrane proteome by altering the levels of membrane-associated proteins in circulating neutrophils of AATD-COPD patients, in contrast to their non-AATD-COPD counterparts.

To overcome the limitations of current AATD diagnostic tools, Kemp et al. [

21] developed proteotyping, a qualitative proteomic approach referred to as an alternative for detecting the most common alleles, S and Z, associated with this disorder. This technique involves trypsin-mediated peptide generation followed by LC-MS/MS analysis, enabling the detection of the S and Z alleles. The mutations associated with these alleles cause amino acid changes, leading to differences in the sequence and mass of peptides involved, compared to those from wild-type AAT (M alleles). The ability of MS to detect the mass differences between S/Z peptides and non-S/non-Z peptides enables the easy identification of the mutations. By combining the analysis of peptide patterns with AAT quantification through immunoassay, this approach provides an accurate assessment of deficiency alleles in most patients.

A qualitative proteome profiling of exhaled breath condensate (EBC) from COPD patients without emphysema, individuals with pulmonary emphysema linked to AATD, non-smokers (NS), and healthy smokers (HS) was conducted by Fumagalli et al. [

34] with the goal of determining whether protein patterns could reflect the distinct lung conditions across the different groups. LC-MS/MS analysis revealed a "fingerprint" of proteins in the EBC, including several inflammatory cytokines, type I and II cytokeratins, two isoforms of surfactant protein A (SP-A), calgranulins A and B, and AAT. Since all proteins found in the COPD and AATD groups were also present in the NS/HS control group, these findings could serve as a foundation for future quantitative studies aimed at identifying specific proteins that may differentiate healthy individuals from AATD patients or monitor effects of therapeutic interventions. The results obtained by the same research group from metabolomic analysis of EBC in two groups of AATD patients (with moderate and severe emphysema) compared to healthy individuals were notably more intriguing [

35]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis produced distinct profiles, revealing both qualitative and quantitative differences between these homogeneous patient and control groups. Among the metabolites that most effectively distinguished patients from controls, acetoin, propionate, acetate, and propane-1,2-diol exhibited the greatest discrepancies. The clear differentiation between the two groups, based on their metabolite content, was confirmed through univariate and multivariate statistical analyses. Using the MetaboAnalyst 3.0 platform to explore the relationships among metabolites, it was found that pyruvate metabolism is the most prominently involved pathway, with most metabolites originating from pyruvate. The ability of NMR to differentiate between the two groups of AATD patients and from healthy controls based on the metabolic fingerprints of their EBC highlights its significant potential for clinical application in this area.

A schematic summary of all articles commented above is shown in

Table 1.

5. Is Proteomics Still in the Early Stages of Research on AATD?

AATD has traditionally been regarded as a rare disease predominantly affecting Caucasians of northern European descent. However, recent research indicates that it is not as rare as previously thought, especially when compared to other genetic disorders, and is not limited to the Caucasian population [

36]. With a prevalence of approximately 1 in 2,000 to 5,000 live births and a global distribution across all major racial groups, the carriers of deficiency alleles are millions. As a result, AATD may be one of the most common single-gene genetic disorders, leading to various clinical manifestations, primarily impacting the lungs and liver [

37,

38]. However, at the onset, these manifestations can be challenging to interpret, as they include asymptomatic or mild/moderate conditions which progress to more severe, debilitating systemic issues. Furthermore, disease progression often spans long periods and varies due to genetic and phenotypic differences, complicating both care decisions and the development of new treatments. Thus, early diagnosis is essential, allowing clinicians to initiate treatment at the earliest opportunity.

Assuming that proteomics can be applied to any disorder without limitations and is significantly advancing our understanding of various diseases, it seems reasonable to believe it could also be extremely valuable in studying AATD. However, given the limited number of publications, it appears that proteomics is still in its early stages in this field. If this is the case, it is still unclear why this platform has been underutilized in studying the disorder. One might question whether the reasons mentioned above could explain the low utilization of proteomics. Indeed, if AATD is continued to be regarded as a "rare" disease, like to many other rare conditions, it tends to be overlooked in research. The absence of a definitive cure, the availability of only one approved therapy, and the lack of clinical tools and validated biomarkers all support this hypothesis. However, there is progress happening in this field. While few in number, it is important to highlight some recent studies using a proteomic approach that expand on existing data.

A notable example is the study by Park et al. [

39] who identified, by using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, club cell protein-16 (CC16) as a potential biomarker for lung function and disease progression in PiZZ patients. The recent proteomic research of Spittle et al. [

40] further supports these findings revealing that elevated serum levels of CC16 are associated with a significant reduction in the transfer factor for carbon monoxide (TLCO). The unique pattern observed in PiZZ patients, compared to typical COPD cases, suggested that PiZZ individuals possess distinct characteristics that deserve more attention. The authors also highlighted the value of proteomics in validating these findings and identifying additional potential biomarkers for AATD. A very recent report by Moll et al. [

41] further affirms the considerable potential of this platform within the AATD research community in identifying biomarkers crucial to this disorder. Also this study can be seen as an extension and the validation of the previous data from Serban et al. [

27] on plasma biomarkers for AATD-associated emphysema. In their study, the authors analyzed a large cohort of individuals from the COPD Gene (PiM) and the AAT Genetic Modifier Study (PiZZ), identifying 16 blood proteins linked to airflow obstruction in both groups. Of these proteins, 14 were highly expressed in the lungs, and a network-based enrichment analysis revealed alterations in immune system function, changes in cytokine and interleukin signaling, and in the regulation of matrix metalloproteinases. These findings could enhance our understanding of the pathogenesis of airflow obstruction and inform potential therapeutic strategies for individuals with severe AATD.

The previously cited work of Kemp et al. [

21] also builds upon earlier studies [

42,

43], offering a relevant breakthrough in the field. It introduces an LC-MS/MS method that minimizes offline purification and reduces the labor involved in sample preparation, while also demonstrating potential in identifying correlations between allele concentrations and the development or severity of clinical symptoms. This approach enables allele-specific quantification in heterozygous patients, providing valuable biological and clinical insights into AAT function and deficiency. This work clearly demonstrates the significant role that proteomics plays in advancing the quantification of AAT allele protein expression in the serum of heterozygous individuals, identifying the most prevalent alleles, S and Z, associated with the disorder.

6. Future Perspectives

Since the majority of AATD cases remain undiagnosed, these individuals, though patients in their own right, often do not receive treatment. Therefore, it makes sense to prioritize early diagnosis of the disease. Over the past decade, new testing methods have been developed, offering rapid, reliable alternatives to traditional approaches. One such test, the AAT Genotyping Test, is a minimally invasive technique that uses DNA extracted from a buccal swab or dried blood spot to simultaneously analyze the 14 most prevalent AATD mutations [

44]. Now that LC-MS has become a standard platform in many clinical laboratories, the approach described above [

21,

42,

43] could support/serve as a complementary method for this analysis. It is an important advancement as the potential of this technique to move beyond the lab will be crucial in bridging the gap between bench research and patient care. This will enable the swift translation of new discoveries into real-world clinical applications and could help address the issue of underdiagnosis thus increasing the detection rate of AATD and potentially reducing the harmful effects of delayed diagnosis. Another critical aspect that requires further development is the treatment of the disease. In AATD, diagnosis and treatment are closely connected, earlier diagnosis in fact offers access to better treatment options and, in turn, improves patient outcomes. AATD involves treating both lung and liver diseases, which are distinct pathologies. Augmentation therapy, the only specific treatment for AATD, has proven effective in treating lung disease but not in addressing the damaging polymers that cause liver disease and death in patients [

19,

45]. Thus, the assessment of liver fibrosis is crucial in the evaluation and follow-up of these patients. While liver transplantation can effectively treat AATD, it is not appropriate in the early stages of the disease. Several new therapeutic approaches are being explored for the treatment of AATD-related liver disease. These strategies aim to reduce the intrahepatic Z-AAT burden by reducing Z-AAT polymers through stimulation of their degradation or silencing their production and/or correcting or stabilizing the folding of the mutated Z-AAT to enable its secretion [

45]. Silencing the production of mutated AAT using small-interfering RNAs shows promise as a strategy compared to other approaches [

46]. DNA and RNA editing holds the potential to not only reduce the production of mutant Z-AAT but also increase the synthesis of wild-type M-AAT. This will, effectively address both the gain-of-function liver disease and the loss-of-function lung disease in affected individuals. Additionally, it enables the preservation of the body's natural regulatory mechanisms for SERPINA1 expression, ensuring that wild-type M-AAT is produced as an acute phase reactant in response to inflammation and tissue injury [

45]. Data from proteomic and metabolomic analyses could offer valuable insights for evaluating therapeutic responsiveness to potential drug. We are confident that the LC-MS platform could play a crucial role in analyzing the glycans present on Z-AAT in the future. This will offer a deeper understanding of how glycosylation affects the immune-modulatory functions of AAT. While extensive glycoanalysis has been conducted on normal AAT from healthy individuals, only one study has so far examined plasma AAT from Z-AAT-deficient individuals [

47]. Nonetheless, the increased fucosylation observed on the N-glycans of Z-AAT in this study suggests ongoing inflammation in individuals with AATD, underscoring the potential for early therapeutic intervention.

One might question whether animal models could provide more detailed insights into the underlying mechanisms of the disease and guide future treatment strategies.

Given the limitations of mouse models in studying lung diseases, PiZZ ferret models have been used as a platform for preclinical testing of therapeutics, including gene therapy, for the progressive COPD seen in AAT-deficient patients [

48]. Despite some differences between the ferret models of AATD and human disease, the similarities offer hope that this model could enable longitudinal assessment of pulmonary function in humans [

48]. The expected answers from this approach aim to address several critical questions, such as the onset of the disease, its initial manifestations, and the ideal time for intervention. Additional inquiries focus on the roles of AAT beyond its antiprotease function, the most suitable genetic therapy for this complex gain- and loss-of-function disease, and whether gene therapy alone can reverse lung function decline after the disease has progressed. Clearly, proteomics and metabolomics analyses of fluids and tissues from these animals could offer significant insights in resolving these questions.

5. Conclusions

Two central questions frequently arise among physicians: Is AATD truly a rare disease? And is it a fatal inherited disorder, or treatable? The ongoing efforts in identifying disease biomarkers and developing therapies that complement or replace augmentation therapy appear to be aimed at shifting the long-held perception of the disease. The growing use of advanced proteomic techniques, along with the development of new therapeutic strategies, will soon enhance our understanding of this complex disease, facilitating earlier diagnoses and enabling targeted interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.I. and S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, P.I; S.V.; and M.A.G.; writing—review and editing, M.A.G.; M.D.; M.G.; and T.R.; supervision, P.I. and S.V.; funding acquisition, S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to thank the Italian Ministry of Research and University for funding this paper in the framework of the project PRIN 2022F5N25M.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAT |

α1-antitrypsin |

| AATD |

α1-antitrypsin deficiency |

| COPD |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| IEF |

Isoelectric focusing |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry |

| DIGE |

Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis |

| IPF |

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| NS |

Non-smokers |

| HS |

Healthy smokers |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

References

- Viglio, S.; Iadarola, P.; D’Amato, M.; Stolk, J. Methods of Purification and Application Procedures of Alpha1 Antitrypsin: A Long-Lasting History. Molecules 2020, 25, 4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janciauskiene, S.M.; Bals, R.; Koczulla, R.; Vogelmeier, C.; Köhnlein, T.; Welte, T. The Discovery of A1-Antitrypsin and Its Role in Health and Disease. Respir Med 2011, 105, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gettins, P.G.W. Serpin Structure, Mechanism, and Function. Chem Rev 2002, 102, 4751–4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrarotti, I.; Wencker, M.; Chorostowska-Wynimko, J. Rare Variants in Alpha 1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: A Systematic Literature Review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2024, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foil, K.E. Variants of SERPINA1 and the Increasing Complexity of Testing for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Ther Adv Chronic Dis, 2021; 12_suppl, 20406223211015954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Serres, F.J.; Blanco, I. Prevalence of A1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Alleles PI*S and PI*Z Worldwide and Effective Screening for Each of the Five Phenotypic Classes PI*MS, PI*MZ, PI*SS, PI*SZ, and PI*ZZ: A Comprehensive Review. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2012, 6, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teckman, J.H.; Buchanan, P.; Blomenkamp, K.S.; Heyer-Chauhan, N.; Burling, K.; Lomas, D.A. Biomarkers Associated With Future Severe Liver Disease in Children With Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency. Gastro Hep Adv 2024, 3, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miravitlles, M.; Turner, A.M.; Sucena, M.; Mornex, J.-F.; Greulich, T.; Wencker, M.; McElvaney, N.G. Assessment and Monitoring of Lung Disease in Patients with Severe Alpha 1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: A European Delphi Consensus of the EARCO Group. Respir Res 2024, 25, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Crisford, H.; Scott, A.; Sapey, E.; Stockley, R.A. A Novel in Vitro Cell Model of the Proteinase/Antiproteinase Balance Observed in Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1421598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnone, M.; Piloni, D.; Ferrarotti, I.; Di Venere, M.; Viglio, S.; Magni, S.; Bardoni, A.; Salvini, R.; Fumagalli, M.; Iadarola, P.; et al. A Pilot Study to Investigate the Balance between Proteases and A1-Antitrypsin in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid of Lung Transplant Recipients. High Throughput 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockley, R.A.; Parr, D.G. Antitrypsin Deficiency: Still More to Learn about the Lung after 60 Years. ERJ Open Res 2024, 10, 00139–02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulkareddy, V.; Roman, J. Pulmonary Manifestations of Alpha 1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Am J Med Sci 2024, 368, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mornex, J.-F.; Traclet, J.; Guillaud, O.; Dechomet, M.; Lombard, C.; Ruiz, M.; Revel, D.; Reix, P.; Cottin, V. Alpha1-Antitrypsin Deficiency: An Updated Review. Presse Med 2023, 52, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Hinojosa, C.; Fatela-Cantillo, D.; Lopez-Campos, J.L. Measuring of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Concentration by Nephelometry or Turbidimetry. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2750, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlata, S.; Ottaviani, S.; Villa, A.; Baglioni, S.; Basile, F.; Annunziata, A.; Santangelo, S.; Francesconi, M.; Arcoleo, F.; Balderacchi, A.M.; et al. Improving the Diagnosis of AATD with Aid of Serum Protein Electrophoresis: A Prospective, Multicentre, Validation Study. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024, 62, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnad, P.; Brantly, M.L.; Bals, R. Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency; ERS Monograph; 1st ed.; European Respiratory Society: Sheffield, 2019; ISBN 978-1-84984-108-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gruntman, A.M.; Xue, W.; Flotte, T.R. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2750, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasí, F. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Med Clin (Barc) 2024, 162, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, M.; Ellis, P.; Pye, A.; Turner, A.M. Obstacles to Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Current Perspectives. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2020, 16, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Durán, M.; Lopez-Campos, J.L.; Barrecheguren, M.; Miravitlles, M.; Martinez-Delgado, B.; Castillo, S.; Escribano, A.; Baloira, A.; Navarro-Garcia, M.M.; Pellicer, D.; et al. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Outstanding Questions and Future Directions. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2018, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J.; Ladwig, P.M.; Snyder, M.R. Alpha-1-Antitrypsin (A1AT) Proteotyping by LC-MS/MS. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2750, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, P.H. Diagnosis and Augmentation Therapy for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Current Knowledge and Future Potential. Drugs Context 2023, 12, 2023-3–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantly, M. Treatment for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Does Augmentation Therapy Work? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023, 208, 948–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischak, H.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Argiles, A.; Attwood, T.K.; Bongcam-Rudloff, E.; Broenstrup, M.; Charonis, A.; Chrousos, G.P.; Delles, C.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. Implementation of Proteomic Biomarkers: Making It Work. Eur J Clin Invest 2012, 42, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, A.G. Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics as an Emerging Tool in Clinical Laboratories. Clin Proteomics 2023, 20, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, J.S. Protein Identification Using MS/MS Data. J Proteomics 2011, 74, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, K.A.; Pratte, K.A.; Strange, C.; Sandhaus, R.A.; Turner, A.M.; Beiko, T.; Spittle, D.A.; Maier, L.; Hamzeh, N.; Silverman, E.K.; et al. Unique and Shared Systemic Biomarkers for Emphysema in Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. EBioMedicine 2022, 84, 104262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candia, J.; Cheung, F.; Kotliarov, Y.; Fantoni, G.; Sellers, B.; Griesman, T.; Huang, J.; Stuccio, S.; Zingone, A.; Ryan, B.M.; et al. Assessment of Variability in the SOMAscan Assay. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 14248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiko, T.; Janech, M.G.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Atkinson, C.; Coxson, H.O.; Barth, J.L.; Stephenson, S.E.; Wilson, C.L.; Schnapp, L.M.; Barker, A.; et al. Serum Proteins Associated with Emphysema Progression in Severe Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2017, 4, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, E.; Raymond, A.-A.; Leon, C.; Dupuy, J.-W.; Di-Tommaso, S.; Senant, N.; Collardeau-Frachon, S.; Ruiz, M.; Lachaux, A.; Saltel, F.; et al. Hepatocyte Proteomes Reveal the Role of Protein Disulfide Isomerase 4 in Alpha 1-Antitrypsin Deficiency. JHEP Rep 2021, 3, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlmeier, S.; Nieminen, P.; Gao, J.; Kanerva, T.; Rönty, M.; Toljamo, T.; Bergmann, U.; Mazur, W.; Pulkkinen, V. Lung Tissue Proteomics Identifies Elevated Transglutaminase 2 Levels in Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016, 310, L1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P.; McEnery, T.; McQuillan, K.; McElvaney, O.F.; McElvaney, O.J.; Landers, S.; Coleman, O.; Bussayajirapong, A.; Hawkins, P.; Henry, M.; et al. A1 Antitrypsin Therapy Modulates the Neutrophil Membrane Proteome and Secretome. Eur Respir J 2020, 55, 1901678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, D.A.; Reeves, E.P.; Meleady, P.; Henry, M.; McElvaney, O.J.; Carroll, T.P.; Condron, C.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Clynes, M.; O’Neill, S.J.; et al. α-1 Antitrypsin Regulates Human Neutrophil Chemotaxis Induced by Soluble Immune Complexes and IL-8. J Clin Invest 2010, 120, 4236–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, M.; Ferrari, F.; Luisetti, M.; Stolk, J.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Capuano, D.; Viglio, S.; Fregonese, L.; Cerveri, I.; Corana, F.; et al. Profiling the Proteome of Exhaled Breath Condensate in Healthy Smokers and COPD Patients by LC-MS/MS. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 13894–13910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, C.; Ciaramelli, C.; Fumagalli, M.; Bussei, R.; Mazzoni, V.; Viglio, S.; Iadarola, P.; Stolk, J. 1H NMR To Explore the Metabolome of Exhaled Breath Condensate in A1-Antitrypsin Deficient Patients: A Pilot Study. J Proteome Res 2016, 15, 4569–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Serres, F.J. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Is Not a Rare Disease but a Disease That Is Rarely Diagnosed. Environ Health Perspect 2003, 111, 1851–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Lopez, R.; Barjaktarevic, I. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: A Rare Disease? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2020, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Singh, K. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Navigating Challenges Through Collaborative Innovation. Chest 2024, 166, 1288–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Churg, A.; Wright, J.L.; Li, Y.; Tam, S.; Man, S.F.P.; Tashkin, D.; Wise, R.A.; Connett, J.E.; Sin, D.D. Club Cell Protein 16 and Disease Progression in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013, 188, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, D.A.; Mansfield, A.; Pye, A.; Turner, A.M.; Newnham, M. Predicting Lung Function Using Biomarkers in Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, M.; Hobbs, B.D.; Pratte, K.A.; Zhang, C.; Ghosh, A.J.; Bowler, R.P.; Lomas, D.A.; Silverman, E.K.; DeMeo, D.L. Assessing Inflammatory Protein Biomarkers in COPD Subjects with and without Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency 2025, 2025.01.11.25320392.

- Donato, L.J.; Karras, R.M.; Katzmann, J.A.; Murray, D.L.; Snyder, M.R. Quantitation of Circulating Wild-Type Alpha-1-Antitrypsin in Heterozygous Carriers of the S and Z Deficiency Alleles. Respir Res 2015, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Snyder, M.R.; Zhu, Y.; Tostrud, L.J.; Benson, L.M.; Katzmann, J.A.; Bergen, H.R. Simultaneous Phenotyping and Quantification of α-1-Antitrypsin by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Clin Chem 2011, 57, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardim, J.R.; Casas-Maldonado, F.; Fernandes, F.L.A.; Castellano, M.V.C. de O.; Torres-Durán, M.; Miravitlles, M. Update on and Future Perspectives for the Diagnosis of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol 2021, 47, e20200380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erion, D.M. : Liu, L. Y.; Brown, C.R.; Rennard, S.; Farah, H. Editing approaces to treat alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Chest 2025, 167, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, N.; Pereira, V.M.; Pestana, M.; Jasmins, L. Future Perspectives in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Liver Disease Associated with Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. GE Port J Gastroenterol 2023, 30, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.; Saldova, R.; O’Brien, M.E.; Bergin, D.A.; Carroll, T.P.; Keenan, J.; Meleady, P.; Henry, M.; Clynes, M.; Rudd, P.M.; et al. Increased Outer Arm and Core Fucose Residues on the N-Glycans of Mutated Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Protein from Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficient Individuals. J Proteome Res 2014, 13, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Liu, X.; Vegter, A.R.; Evans, T.I.A.; Gray, J.S.; Guo, J.; Moll, S.R.; Guo, L.J.; Luo, M.; Ma, N.; et al. Ferret Models of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Develop Lung and Liver Disease. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e143004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).