1. Introduction

The precise measurement of dynamic parameters such as velocity, trajectory, and spatial position not only represents a fundamental requirement across numerous scientific and engineering domains but has also driven the rapid development of photoelectric detection technologies. Among these, Laser Light Screen Systems (LLSS) have gained widespread attention in dynamic testing applications due to their significant advantages including non-contact operation, high responsivity, and cost-effectiveness [

1,

2,

3,

4]. LLSS function by generating structured light fields within a measurement volume; when a target traverses this field, it reflects laser radiation that is subsequently captured by strategically placed detection screens equipped with photoelectric sensors [

5,

6]. These sensors convert the intercepted light into weak electrical signals that encode critical information about the target's dynamics [

6]. By employing multiple detection screens with known positions and orientations, LLSS enables the reconstruction of high-speed target trajectories through spatial parameter analysis and precise timing of screen passages [

7,

8], proving invaluable in applications like ballistics testing and engineering safety assessments [

7,

9,

10].

However, the practical application of LLSS faces significant challenges, primarily related to signal integrity. As the detection distance increases, the reflected energy attenuates sharply, compounded by the spatial sensitivity characteristics of the detectors, leading to a rapid degradation of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, the resulting photoelectric signals often exhibit complex characteristics, including nonlinearity arising from detector spatial sensitivity, non-periodicity due to the random nature of target passage, and non-stationarity (time-varying statistical properties), which becomes particularly acute when the SNR falls below critical thresholds (e.g., 5 dB) [

13]. These inherent signal degradations severely compromise measurement accuracy and reliability, necessitating the development of sophisticated signal processing techniques capable of extracting meaningful information from these weak and complex waveforms [

3].

Historically, efforts to address these signal processing challenges have evolved through distinct stages. Initial approaches relied heavily on frequency-domain analysis, such as Fourier transforms. While offering spectral insights for periodic signals, these methods struggle with the non-stationary nature of LLSS signals, often introducing artifacts like spectral leakage due to inherent stationarity assumptions [

14]. Wavelet transforms emerged as an improvement, providing multi-resolution analysis capabilities [

15,

16]. However, their efficacy diminishes in extremely low SNR scenarios (<-10 dB), suffering from difficulties in optimal parameter selection and pronounced boundary effects that distort finite-length signals [

17].

Recognizing the limitations of frequency-domain methods for non-stationary and nonlinear signals, time-frequency joint analysis techniques were developed. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) was introduced to adaptively decompose signals but is plagued by mode mixing issues [

18]. While Ensemble EMD (EEMD) alleviates mode mixing, it introduces phase distortions and significantly increases computational demands [

19]. Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) represents a more mathematically grounded advancement, demonstrating success in various fields [

20,

21,

22,

23].Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) offers superior noise robustness compared to Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and its ensemble variant (EEMD); however, its efficacy is critically dependent on the pre-selection of key parameters—namely the mode number

K and penalty factor α—and its convergence can deteriorate under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions. Notably, the reported precision gains in underwater laser ranging via VMD–ICA integration were realized only through meticulous parameter tuning [

23].

More recently, the surge in computational power has spurred the development of data-driven approaches, including deep learning, for weak signal processing [

24,

25,

26,

27]. These methods can achieve remarkable noise suppression and feature extraction capabilities. Nevertheless, their application to LLSS is often constrained by the need for large, representative training datasets, challenges in ensuring real-time performance crucial for high-speed measurements, limited interpretability of complex models, and potential difficulties in generalizing to diverse operational conditions without integrating underlying physical principles.

Collectively, these existing methodologies face several critical limitations when applied to the demanding context of LLSS weak signal processing: (1) a fundamental difficulty in preserving temporal signal integrity under extremely low SNR conditions (e.g., below -10 dB); (2) inadequate real-time processing capabilities for high-speed targets; (3) over-reliance on data without sufficient integration of physical signal characteristics; (4) poor interpretability of 'black-box' models; (5) inherent assumptions of stationarity or linearity that fail to capture the time-varying nature of the signals; and (6) boundary effects in finite-length signal processing leading to energy leakage and distortion. These shortcomings collectively hinder the effective operational range and reliability of LLSS, particularly as target distance increases or ambient noise intensifies.

To overcome these limitations, this paper introduces a novel Multi-stage Collaborative Filtering Chain (MCFC) framework specifically designed for robust processing of weak photoelectric signals from LLSS. The MCFC framework uniquely integrates adaptive bidirectional processing, a multi-stage cascaded filtering strategy, and sophisticated non-stationary signal analysis techniques. This synergistic approach aims to significantly enhance the SNR while meticulously preserving the crucial temporal characteristics embedded within the signal, thereby enabling reliable long-range, high-speed target detection even in complex and noisy environments. We posit that this framework is particularly advantageous for high-precision measurement applications demanding high fidelity, such as ballistics analysis, collision studies, and structural health monitoring. The core contributions of this work, demonstrating the advantages of MCFC over conventional methods, are:

1. Zero-phase FIR Bandpass Filtering Mechanism: A novel filtering approach employing forward-backward processing combined with dynamic phase compensation to rigorously suppress phase distortion, ensuring high-fidelity signal representation throughout the processing chain.

2. Four-stage Cascaded Collaborative Filtering Strategy: An adaptive, multi-stage filtering architecture that synergistically integrates adaptive sampling and sophisticated anti-aliasing techniques. This strategy optimally balances signal reconstruction fidelity, smoothness, and parameter sparsity for enhanced signal quality.

3. Multi-scale Adaptive Transform Algorithm: A robust adaptive transformation algorithm, based on the fourth-order Daubechies wavelet, designed to achieve high-precision signal reconstruction while maintaining stability and effectiveness across diverse and challenging noise environments.

4. Significant Performance Enhancement and Empirical Validation: Rigorous experimental evaluations show that the proposed MCFC framework achieves a remarkable SNR improvement of up to 45 dB for input signals with an SNR as low as -15 dB. Furthermore, correlation coefficients consistently exceeding 0.98 are maintained across various noise conditions, demonstrating superior performance and stability compared to traditional methods.

By addressing the critical bottlenecks in current weak signal processing techniques, the MCFC framework provides an effective solution for photoelectric signal processing, and offering a reliable approach for high-precision measurement applications.

The structure of this article is as follows:

Section 2 covers the MCFC framework's theory and implementation, including bidirectional filtering models and convergence analysis.

Section 3 presents experimental validation and comparisons with state-of-the-art methods.

Section 4 discusses system performance and implementation, while

Section 5 outlines future research directions.

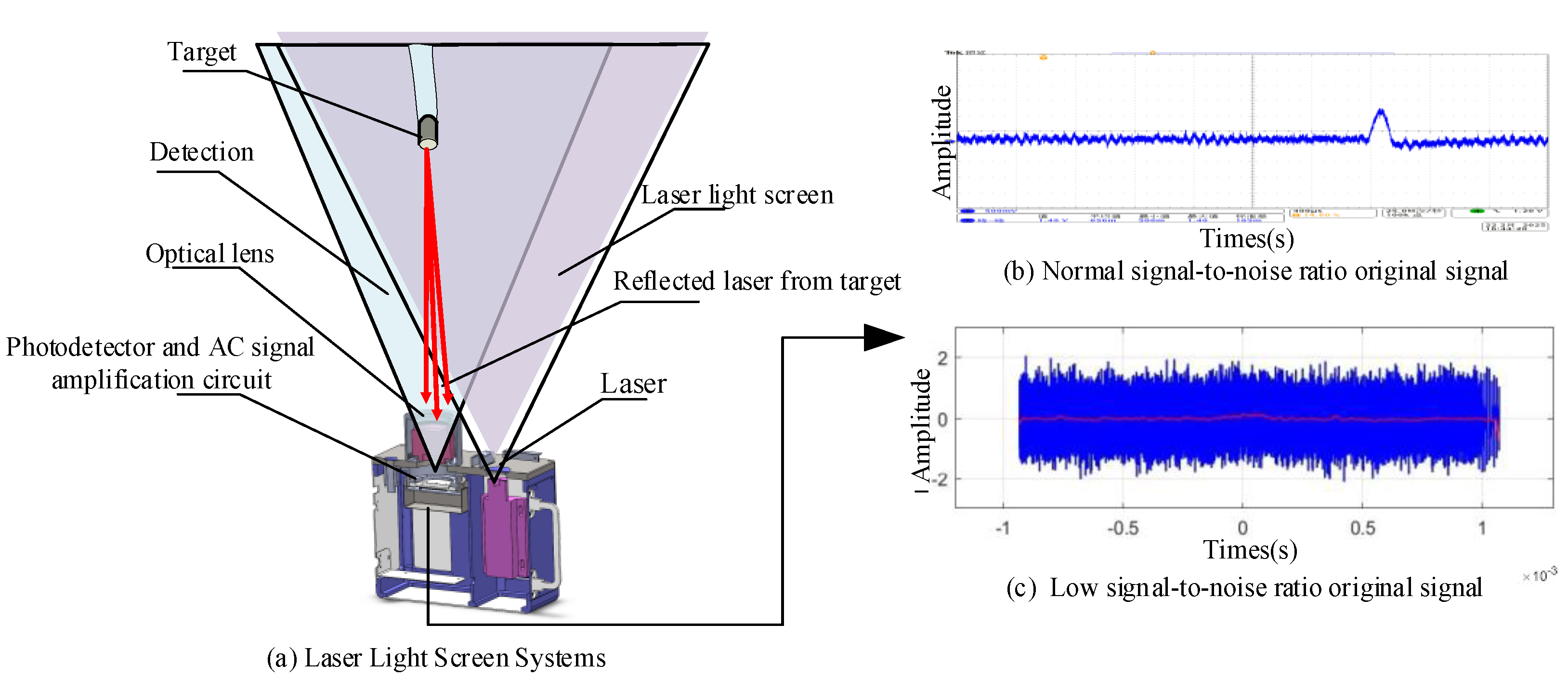

Figure 1 illustrates the signal acquisition and processing scheme, emphasizing target detection under severe noise interference.

Figure 1 illustrates the signal acquisition and processing workflow of the LLSS: in

Figure 1a, this system integrates a line-type semiconductor infrared laser as an active illumination source into conventional Light Screen architecture. The system incorporates optical lenses, slit apertures, and photoelectric detection devices to construct the detection unit, forming a light screen and a laser light screen. When a target goes through the light screen, laser energy reflected from its surface is captured by the photoelectric detection devices through the optical system and converted into electrical signals.

Figure 1b depicts the time-domain signal recorded under normal signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions, where the target-induced pulse appears prominently above a low-level noise floor (horizontal axis: time in seconds; vertical axis: amplitude in arbitrary units), demonstrating the LLSS’s ability to resolve return signals reliably when ambient interference is modest. In contrast,

Figure 1c shows the corresponding waveform under low-SNR conditions, where high-amplitude noise fluctuations mask the target transit signature, rendering direct detection ineffective and underscoring the necessity of active laser illumination and specialized signal-processing techniques to maintain robust detection performance across challenging noise environments.

4. Discussion

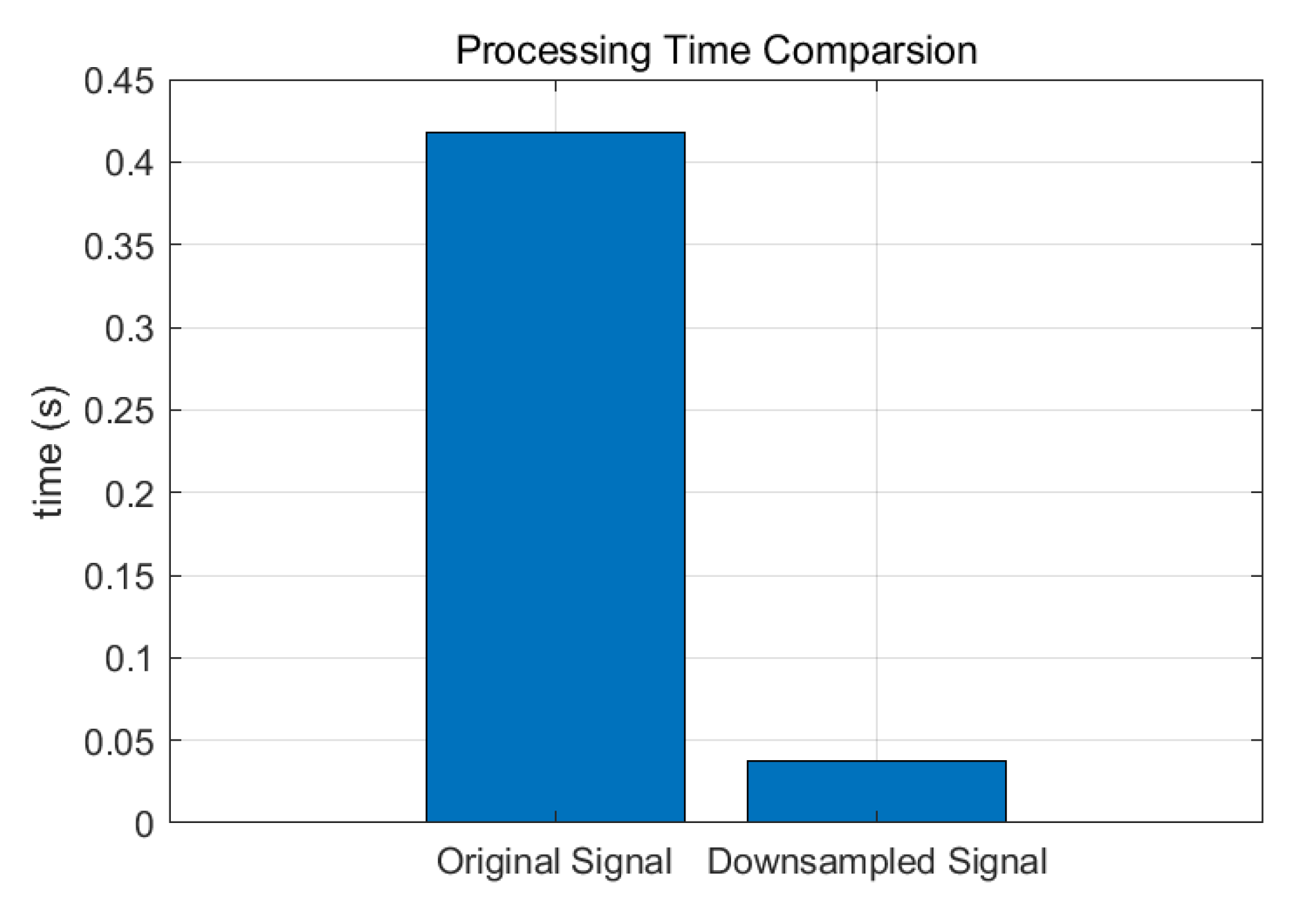

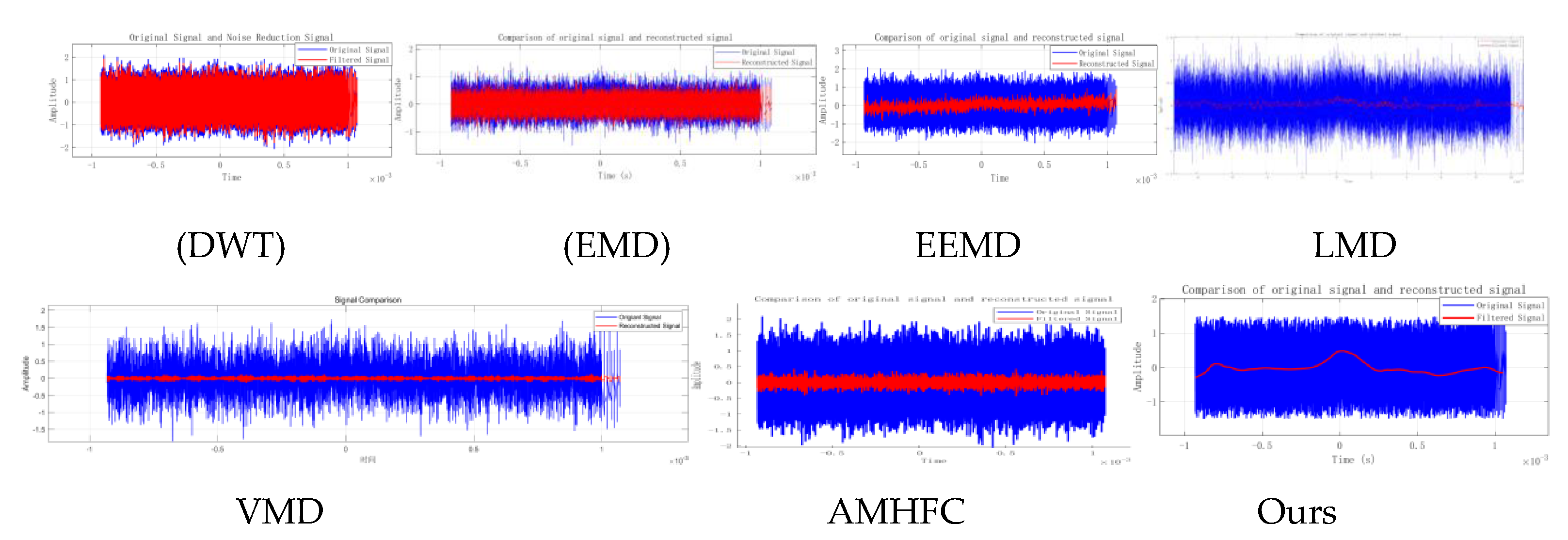

The challenge of reliably extracting weak signals from extremely noisy environments remains a critical bottleneck in Laser Light Screen Systems (LLSS) and similar detection applications. Conventional signal processing techniques often exhibit significant performance degradation under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions, limiting their practical effectiveness [Reference citations needed here, e.g., 7, 13]. This study introduces the Multi-stage Collaborative Filtering Chain (MCFC) framework, designed specifically to overcome these limitations by synergistically integrating adaptive filtering stages. Our findings demonstrate that MCFC not only significantly enhances signal fidelity but also addresses key deficiencies observed in prior methodologies. The core strength of MCFC lies in its ability to achieve substantial signal recovery even from inputs with deeply embedded noise, evidenced by an approximate 25 dB SNR improvement and a remarkable correlation coefficient of 0.981 starting from an input SNR of -20 dB. This level of enhancement is not merely an incremental improvement; it signifies the potential to reliably operate LLSS in noise conditions previously deemed prohibitive. This performance stems from the synergistic interplay of MCFC's core innovations: (1) The zero-phase FIR bidirectional processing is crucial for maintaining the precise temporal characteristics of the transient signals typical in LLSS, a factor often compromised in methods leading to phase distortions, particularly evident near event boundaries (e.g., t = 2×10⁻⁴ s) where MCFC shows clear advantages over methods cited in [

7,

13]. (2) The multi-stage cascaded filtering architecture provides inherent adaptability, allowing the framework to dynamically respond to diverse and varying noise characteristics, unlike fixed-filter approaches or methods optimized for specific noise types [

19,

20]. (3) The multi-scale adaptive wavelet transformation, specifically optimized for boundary condition handling, effectively suppresses noise across different frequency scales without introducing significant artifacts at signal edges, a common issue in standard wavelet denoising. A critical evaluation against established techniques (DWT, EMD, EEMD, LMD, VMD, AMHFC) reveals the distinct advantages of the MCFC framework. While methods like VMD or EMD variants offer improvements over basic transforms, they often struggle with mode mixing, endpoint effects, or sensitivity to parameter selection, especially under extremely low SNR (-15 dB to -20 dB). MCFC's collaborative chain structure appears to mitigate these issues, consistently achieving higher SNR enhancement (up to 45 dB reported in comparative tests) and maintaining superior signal correlation (>0.98). Furthermore, the significant reduction in processing latency (~90% reduction, achieving 0.04 seconds) compared to computationally intensive methods like EEMD or certain VMD implementations [

18,

19,

20] is paramount. This near real-time capability dramatically enhances the feasibility of deploying advanced signal processing in high-speed target detection scenarios where rapid response is essential. The framework's robustness, demonstrated by stable autocorrelation coefficients (0.9773–0.9823) across a challenging SNR range (-15 dB to 10 dB) and its moderate parameter sensitivity (1.243), suggests a practical advantage over methods potentially requiring more frequent recalibration or exhibiting less stability in fluctuating operational conditions [

25,

26].Despite the promising results, certain limitations and avenues for future investigation warrant discussion. The current validation, while thorough across various noise types, primarily relies on simulated and laboratory-generated data. Empirical validation under real-world, extreme environmental conditions [Future Direction 3] is crucial to fully ascertain the framework's operational robustness. While MCFC exhibits moderate parameter sensitivity, the optimal selection of certain parameters (e.g., stage-specific filter orders, wavelet parameters) may still benefit from expert knowledge or further heuristics. Therefore, developing automatic parameter optimization techniques [Future Direction 2], perhaps using machine learning or metaheuristic algorithms, would significantly enhance user accessibility and deployment efficiency. Furthermore, the current MCFC operates on single-channel data. Many LLSS deployments involve multiple screens; thus, extending the framework to multi-channel joint processing [Future Direction 1] could leverage spatial correlations between sensors to potentially achieve even greater noise suppression and target localization accuracy. Looking forward, integrating physics-informed deep learning models [Future Direction 4] presents an exciting prospect. While deep learning offers powerful feature extraction capabilities, maintaining interpretability is crucial for safety-critical detection systems. A physics-informed approach, potentially guided by the signal formation principles in LLSS and incorporating insights from MCFC's structure, could offer a pathway to harness the power of deep learning while preserving algorithmic transparency and trustworthiness, building upon foundational work like [

27]. Such hybrid models could potentially adapt more dynamically to unforeseen noise patterns or system variations encountered in complex field deployments. In conclusion, the MCFC framework represents a significant advancement in weak signal processing for LLSS operating under severe noise. Its architectural innovations translate to demonstrable improvements in SNR, signal fidelity, processing speed, and robustness compared to existing methods. While further real-world validation and automation are beneficial future steps, MCFC provides a robust and effective solution, expanding the operational envelope for LLSS and potentially benefiting other fields facing similar weak signal extraction challenges.

5. Conclusions

The processing framework based on MCFC and multi-scale adaptive wavelet transform proposed in this paper represents significant progress in addressing the challenge of weak signal processing in photoelectric detection. Specifically, the framework encompasses two primary technological innovations:

Firstly, the MCFC approach effectively integrates zero-phase FIR preprocessing with a parameter-adaptive optimization mechanism guided by Wiener filtering criteria. This integration achieves precise phase control and significantly reduces boundary artifacts, thus overcoming the inherent signal distortion issues encountered in conventional methodologies.

Secondly, the multi-scale adaptive wavelet transform introduces a novel adaptive threshold selection algorithm. Under challenging conditions with a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of -20 dB, this algorithm achieves an impressive signal gain of 45.36 dB and maintains a high signal reconstruction correlation coefficient of 0.981. These results highlight the method's superior robustness across varying noise environments. Additionally, the implementation optimization leveraging fast wavelet transform techniques notably decreases the system processing delay to approximately 40 ms, corresponding to a computational efficiency improvement of 90.48%.

The proposed framework demonstrates substantial enhancements in key performance metrics, including signal fidelity, noise resistance, and real-time processing capabilities. Thus, it offers both theoretical contributions and practical applicability in weak signal detection tasks.

Figure 1.

Signal acquisition based on Laser Light Screen Systems.

Figure 1.

Signal acquisition based on Laser Light Screen Systems.

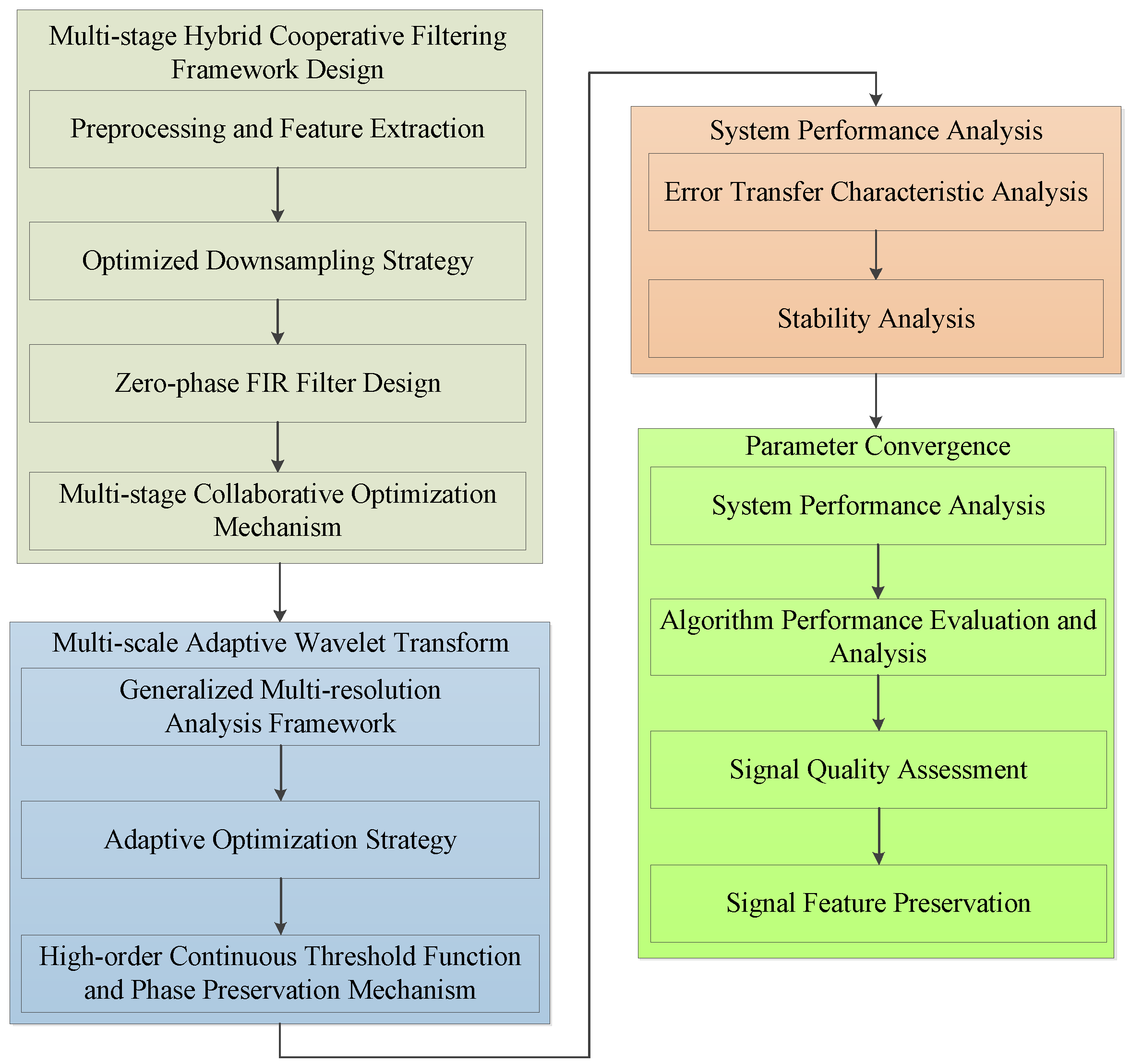

Figure 2.

System architecture of signal processing based on zero-phase multi-stage collaborative filtering chain.

Figure 2.

System architecture of signal processing based on zero-phase multi-stage collaborative filtering chain.

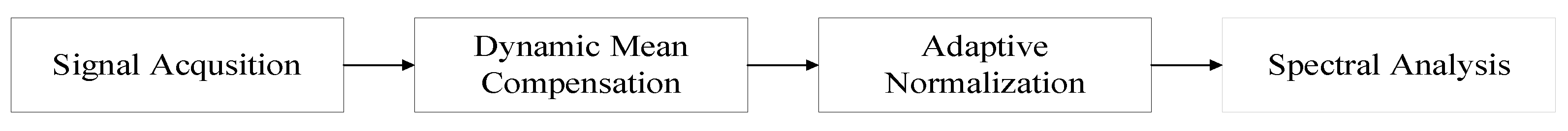

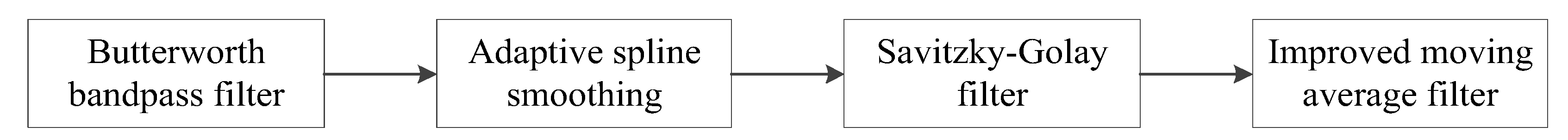

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of signal pre-processing flow.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of signal pre-processing flow.

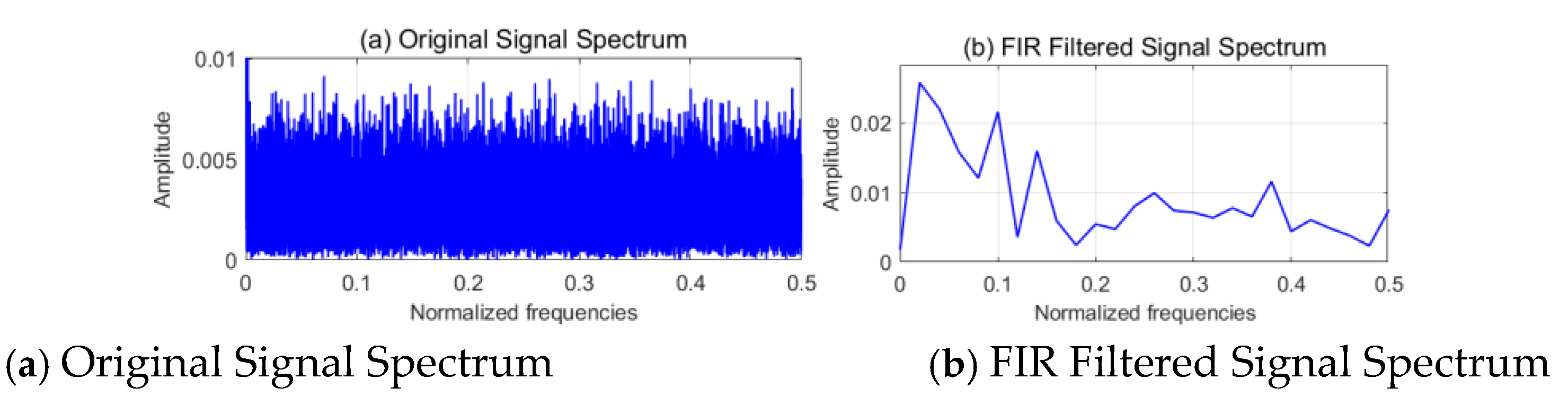

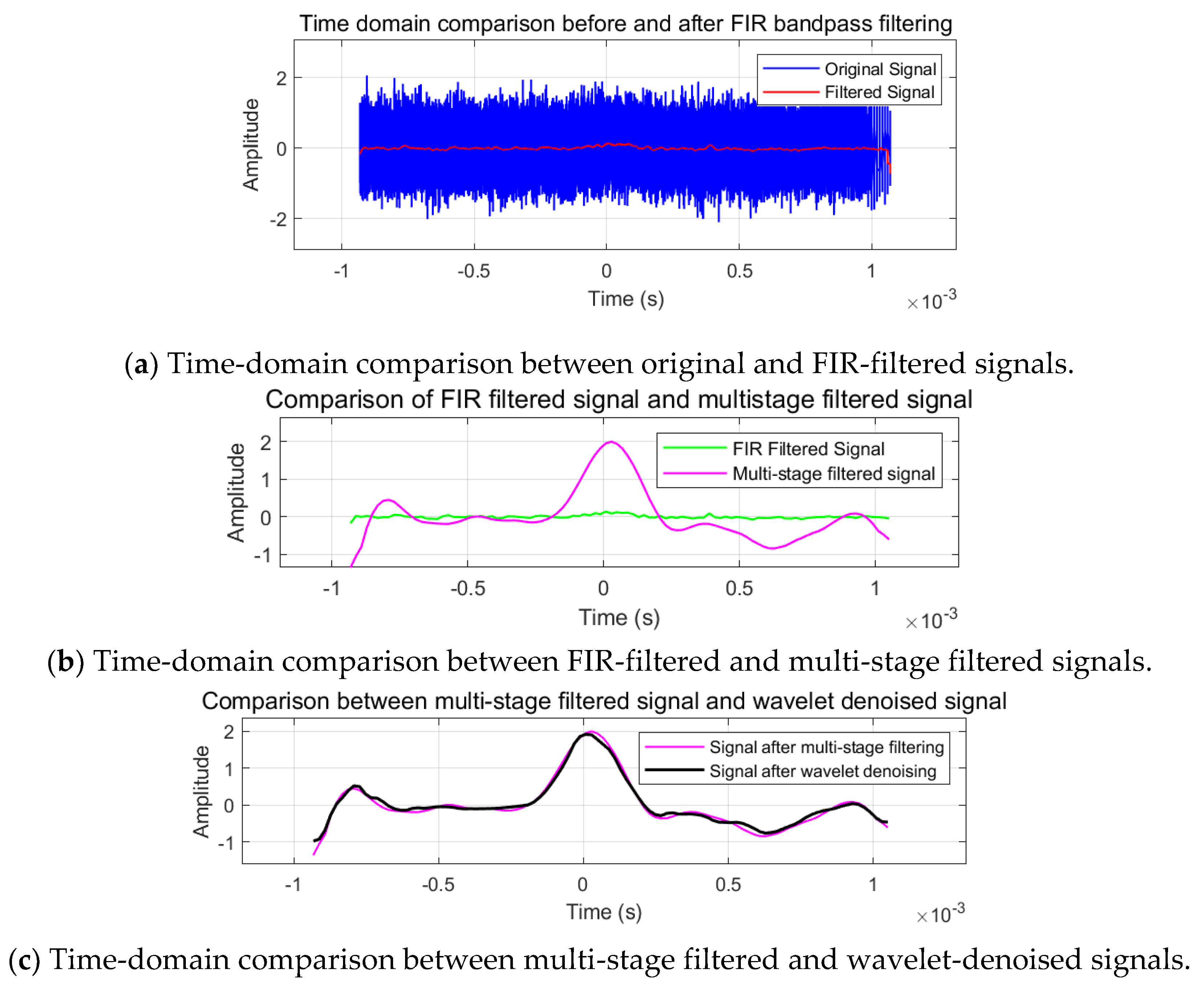

Figure 4.

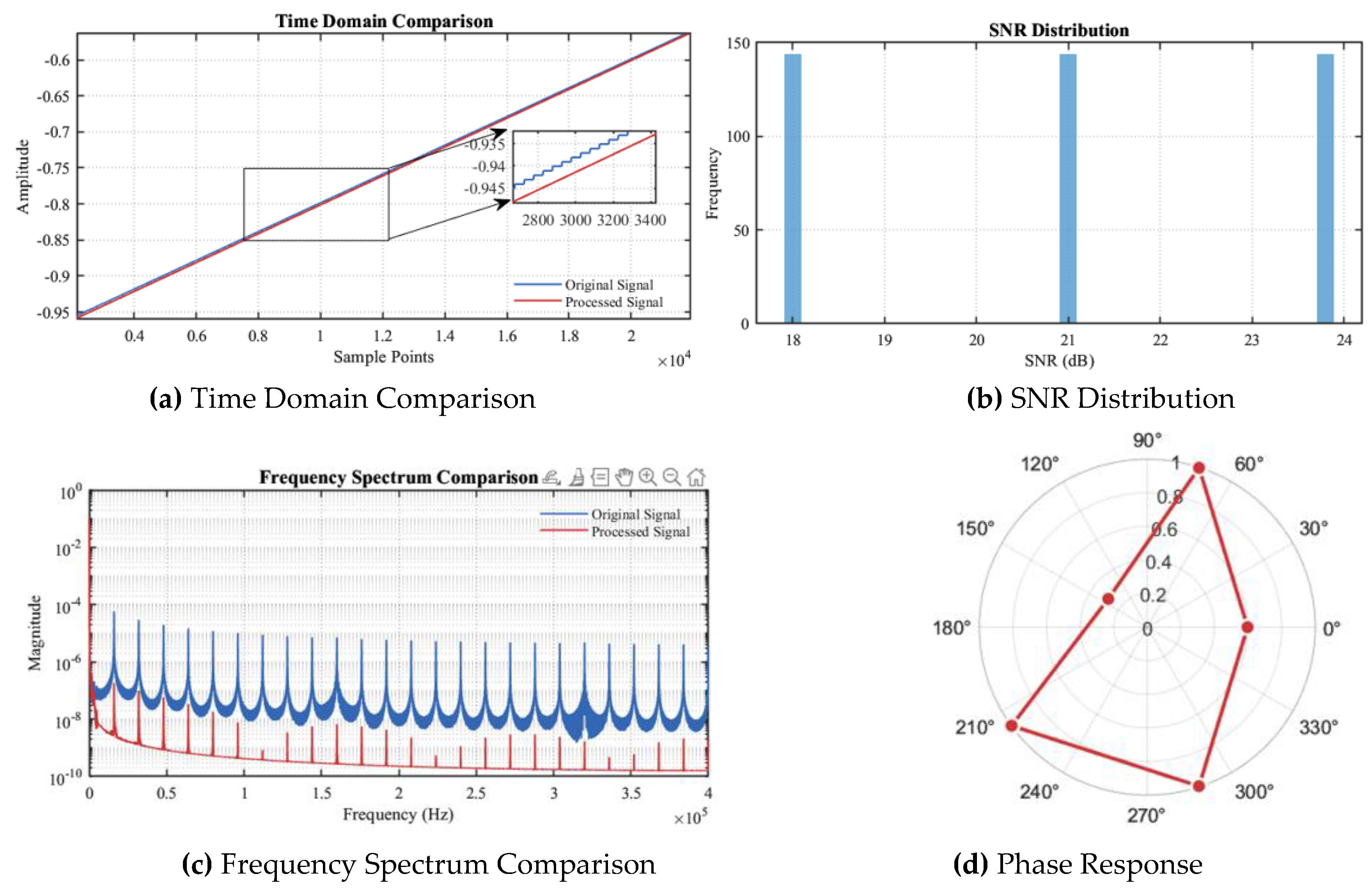

Signal preprocessing results.

Figure 4.

Signal preprocessing results.

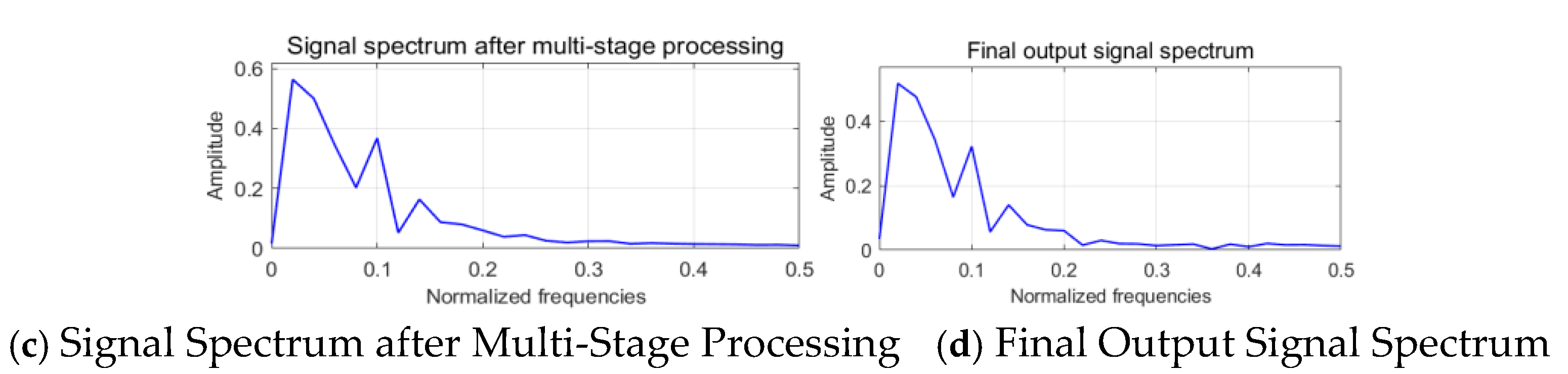

Figure 5.

Experimental graph after adaptive downsampling filtering.

Figure 5.

Experimental graph after adaptive downsampling filtering.

Figure 6.

Experimental results of signal processing with downsampling.

Figure 6.

Experimental results of signal processing with downsampling.

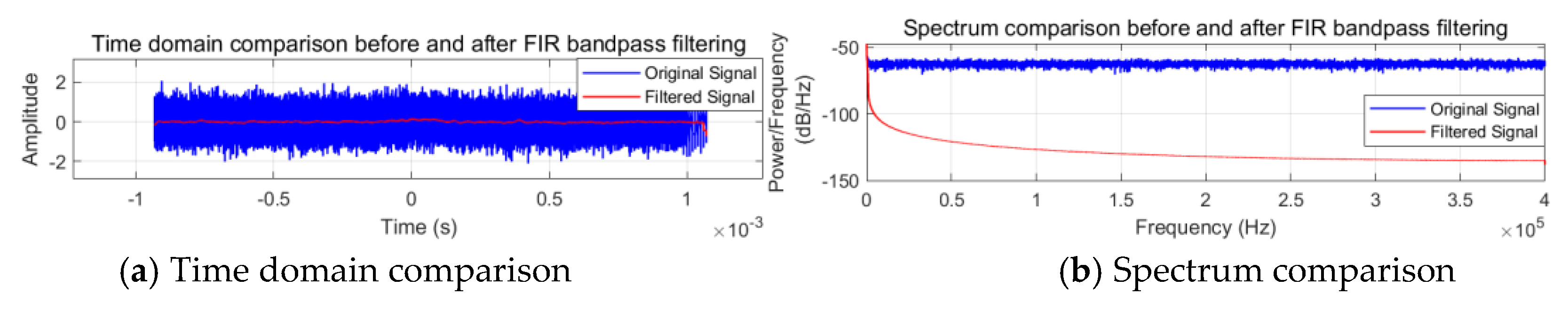

Figure 7.

Time-frequency domain analysis before and after FIR bandpass filtering.

Figure 7.

Time-frequency domain analysis before and after FIR bandpass filtering.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of multi-stage filtering co-processing flow.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of multi-stage filtering co-processing flow.

Figure 9.

Photoelectric Signal Experiment Site.

Figure 9.

Photoelectric Signal Experiment Site.

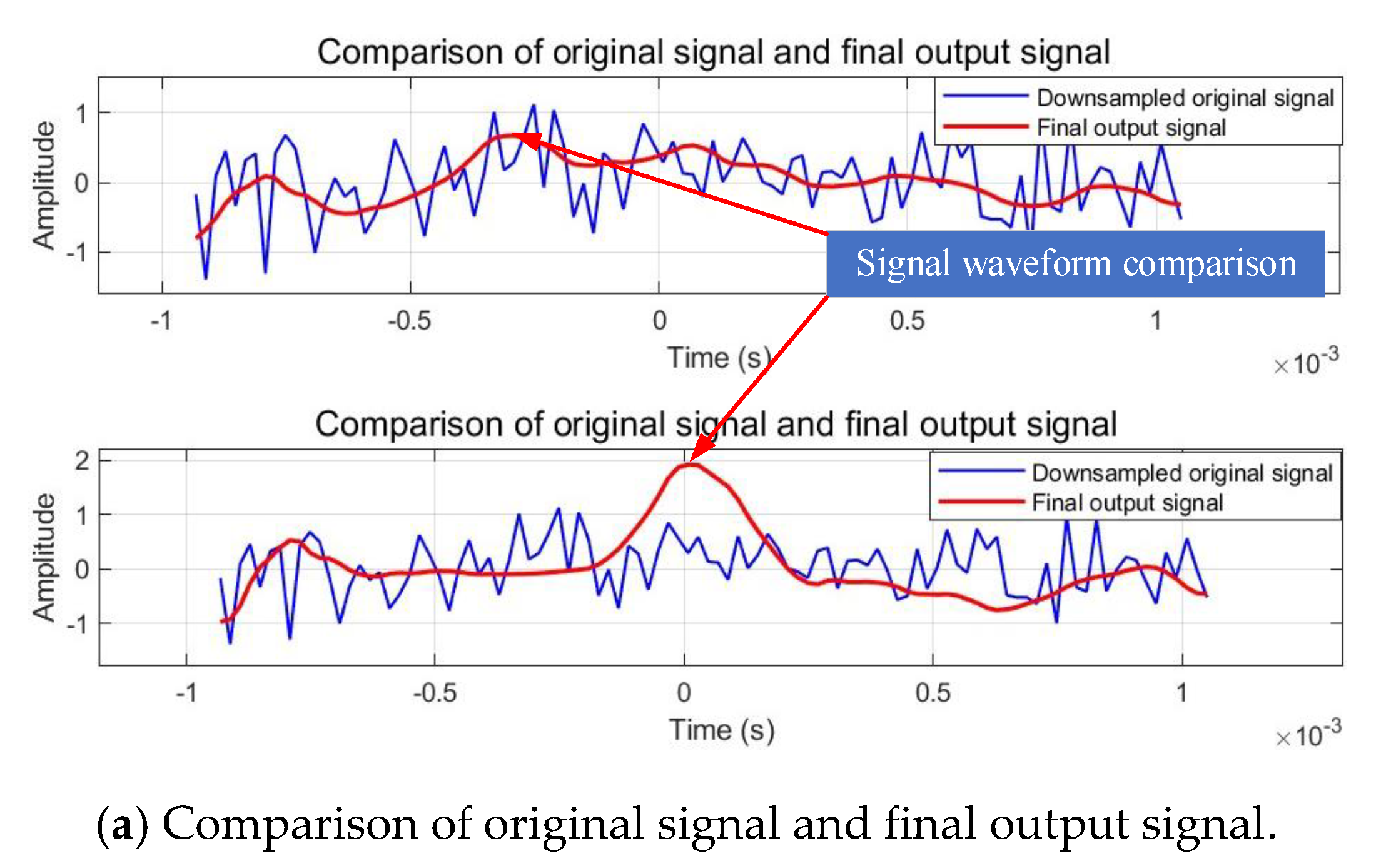

Figure 10.

Results of Time-Domain Analysis.

Figure 10.

Results of Time-Domain Analysis.

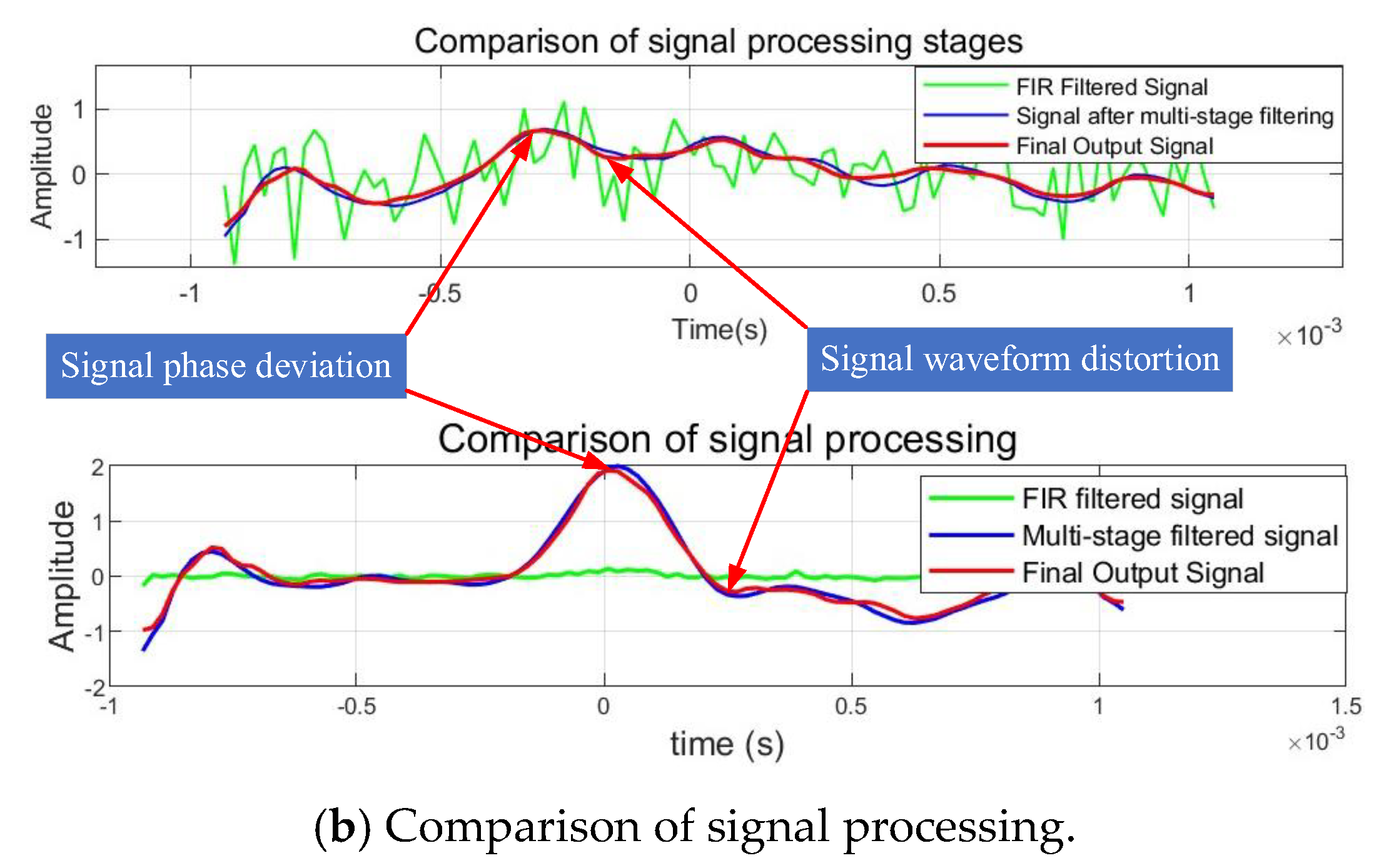

Figure 11.

Comparative Diagram of Phase Experiment.

Figure 11.

Comparative Diagram of Phase Experiment.

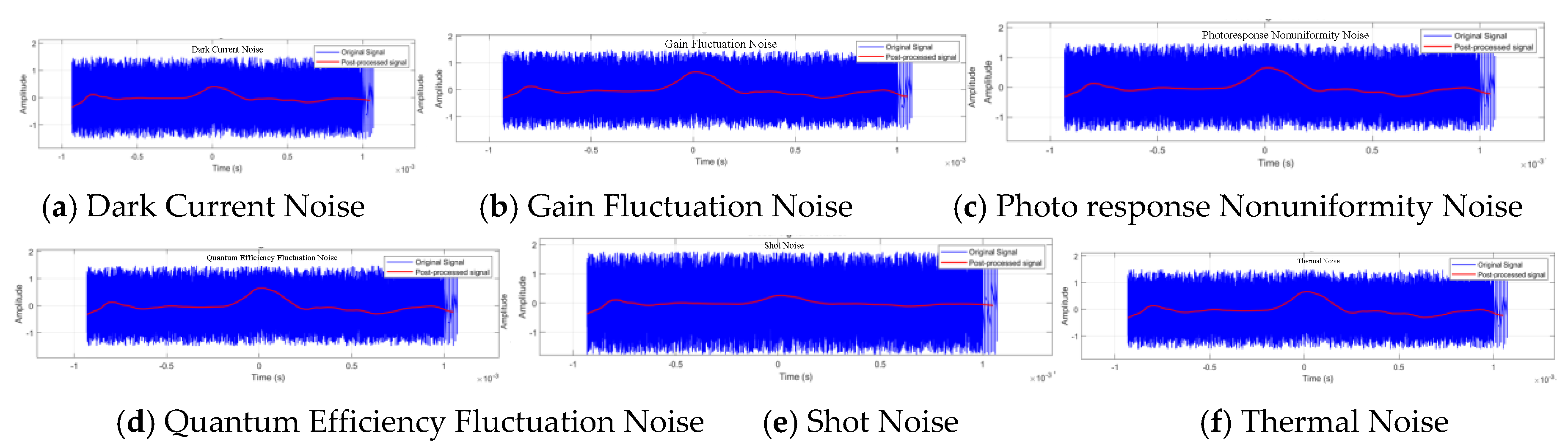

Figure 12.

Processing Results under Various Noise Environments.

Figure 12.

Processing Results under Various Noise Environments.

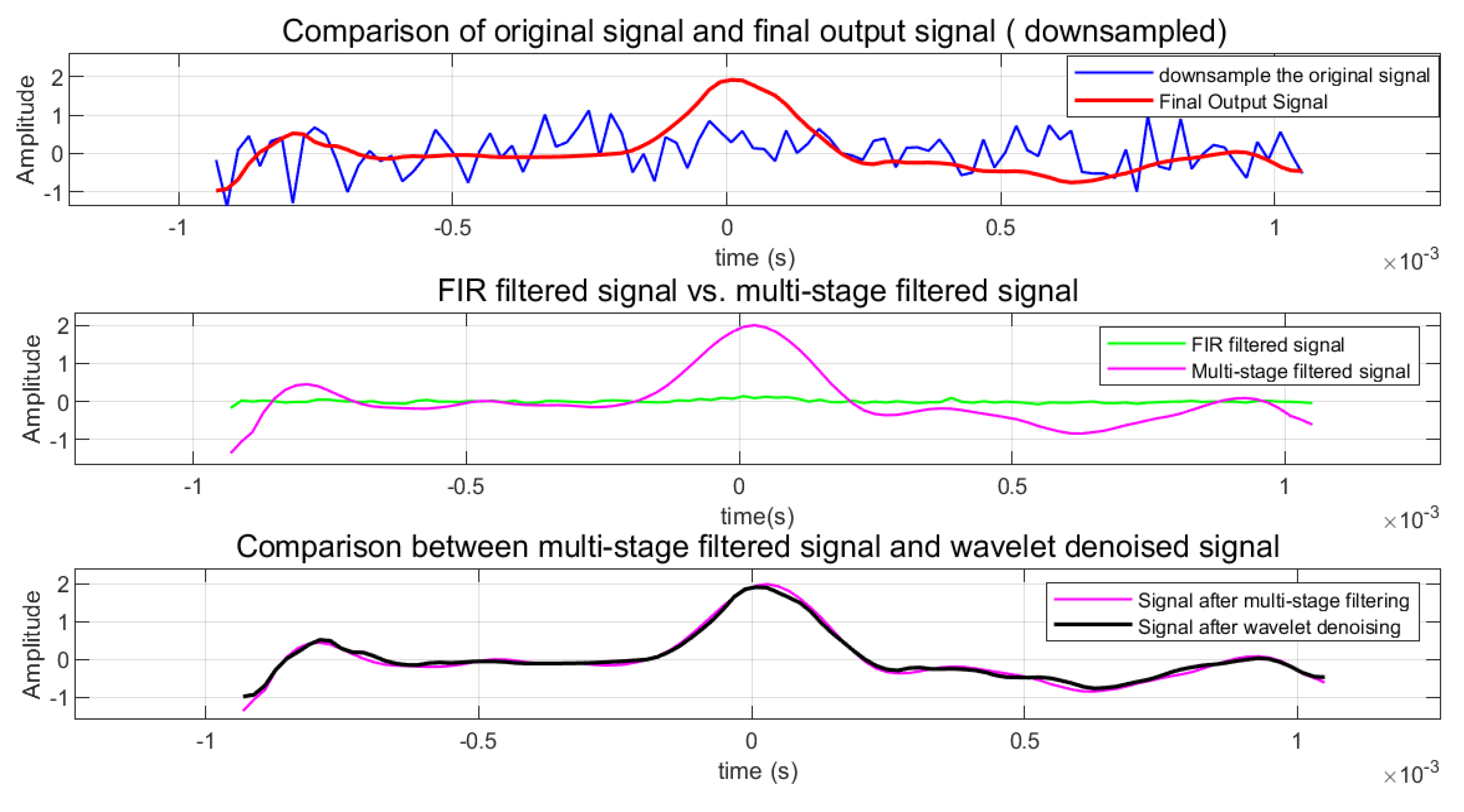

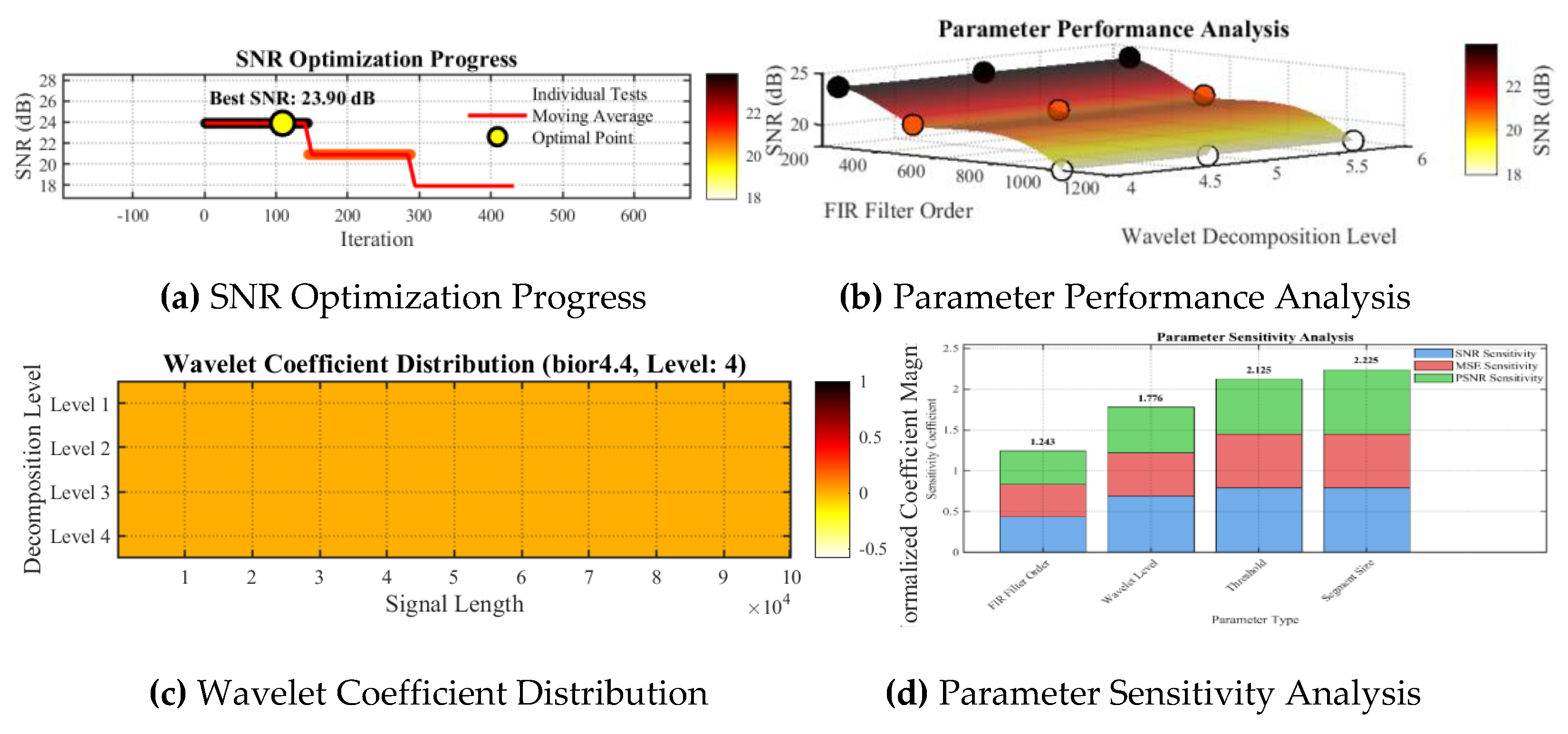

Figure 13.

Comparison of experimental results of different modules.

Figure 13.

Comparison of experimental results of different modules.

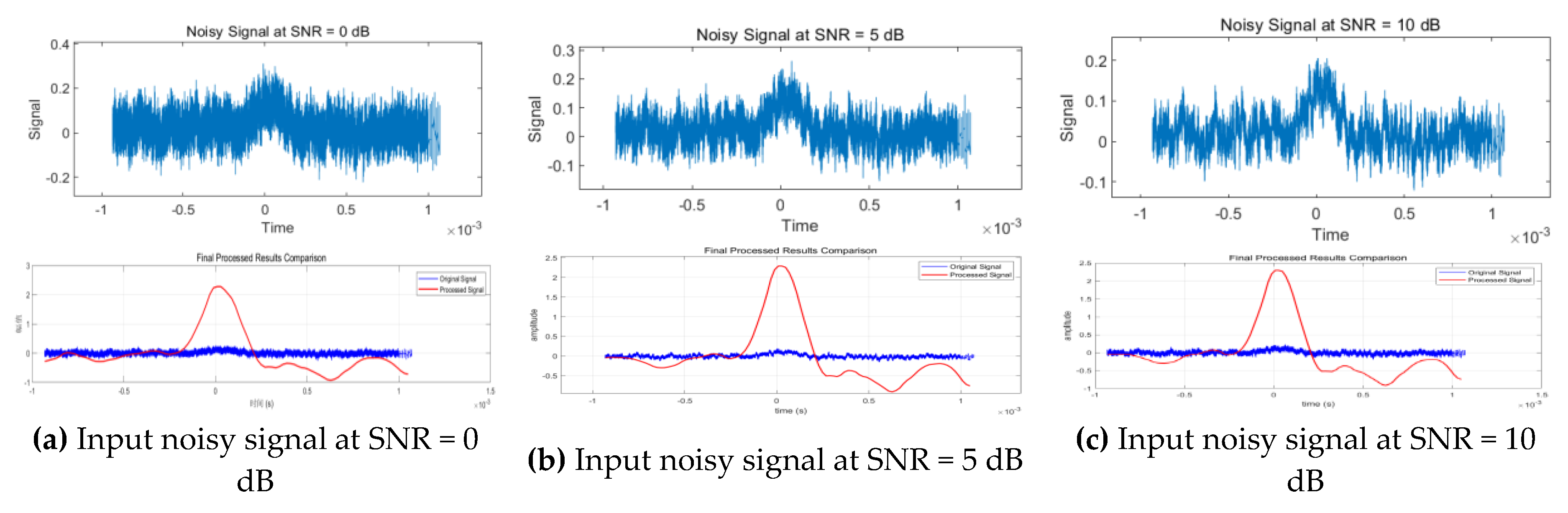

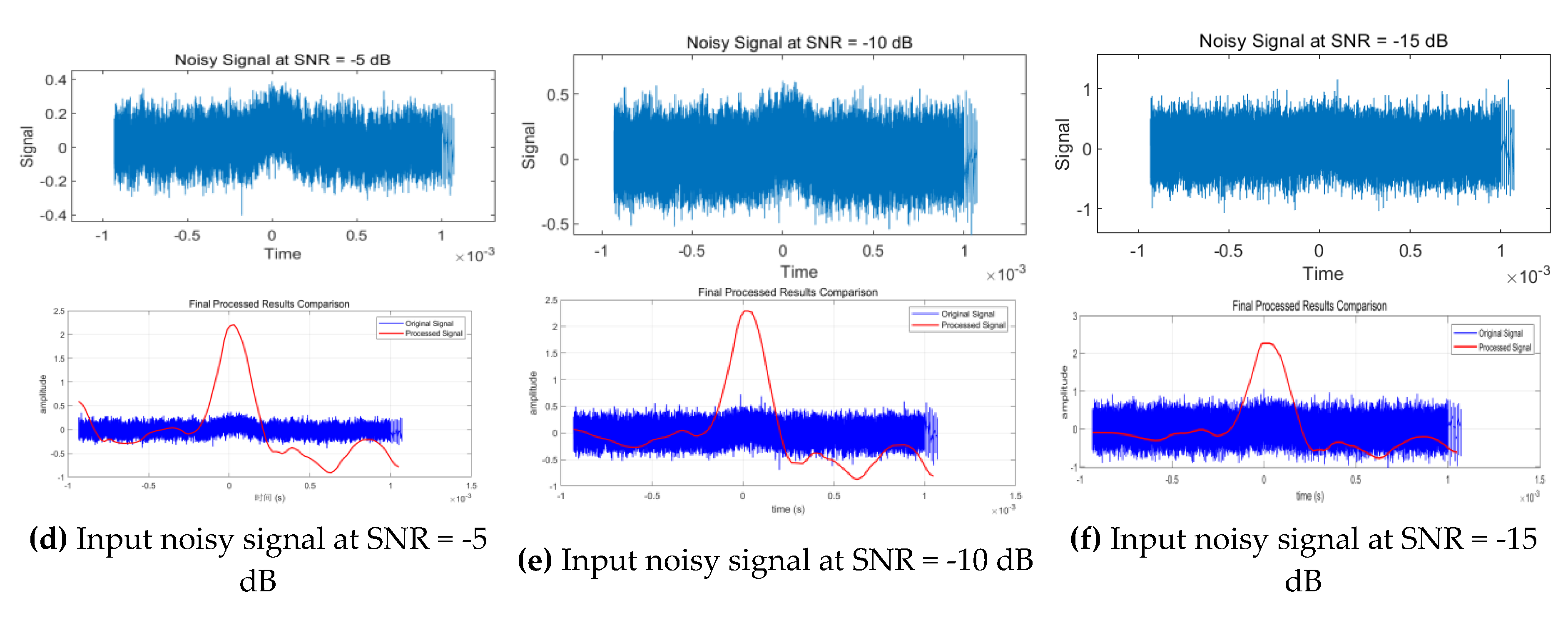

Figure 14.

Graph of the effect of multi-group experiments.

Figure 14.

Graph of the effect of multi-group experiments.

Figure 15.

Time domain analysis diagram.

Figure 15.

Time domain analysis diagram.

Figure 16.

Degree of influence of parameter sensitivity.

Figure 16.

Degree of influence of parameter sensitivity.

Figure 17.

Comparison experiment of different algorithms.

Figure 17.

Comparison experiment of different algorithms.

Table 2.

Comparison of time domain metrics.

Table 2.

Comparison of time domain metrics.

| Method |

Correlation coefficient |

Mean square error |

Signal-to-noise ratio (dB) |

| FIR Filtering |

0.4328 |

0.009996745 |

17.10db |

| Multi-stage filtering |

0.9854 |

0.01331926 |

24.77db |

| Optimized Wavelet Transform |

0.9890 |

0.009579688 |

25.83db |

| Final Output |

0.9890 |

0.009579688 |

25.83db |

Table 3.

Effects of Different Noise Processing Techniques.

Table 3.

Effects of Different Noise Processing Techniques.

| Noise Type |

Original Signal(SNR) |

Processed Signal (SNR) |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio Improvement |

| Dark Current Noise |

-20dB |

2.43dB |

22.43dB |

| Gain Fluctuation Noise |

-20dB |

4.88dB |

24.88dB |

| Photo response Nonuniformity Noise |

-20dB |

4.088dB |

24.08dB |

| Quantum Efficiency Fluctuation Noise |

-20dB |

4.11dB |

24.11dB |

| Shot Noise |

-20dB |

1.19dB |

21.19dB |

| Thermal Noise |

-20dB |

4.67dB |

24.67dB |

Table 5.

Results of quantitative analysis of multiple sets of experimental data.

Table 5.

Results of quantitative analysis of multiple sets of experimental data.

| Case |

Original (db) |

Processed(db) |

Changed(db) |

Coefficient of Variation |

Autocorrelation Function |

| Case 1 |

0 db |

26.82 db |

26.82 db |

1.5070 |

0.9812 |

| Case 2 |

5 db |

28.23 db |

23.23 db |

1.5061 |

0.9818 |

| Case 3 |

10 db |

28.05 db |

17.05 db |

1.5117 |

0.9817 |

| Case 4 |

-5 db |

28.06 db |

33.06 db |

1.4337 |

0.9773 |

| Case 5 |

-10 db |

28.60 db |

38.60 db |

1.4980 |

0.9808 |

| Case 6 |

-15 db |

30.36 db |

45.36 db |

1.4950 |

0.9823 |

Table 6.

Comparison of the performance of different methods (-20dB SNR condition).

Table 6.

Comparison of the performance of different methods (-20dB SNR condition).

| Method |

Signal-to-noise ratio of original signal |

Signal-to-noise ratio of processed signal |

Signal-to-noise ratio improvement (dB) |

Correlation coefficient |

| DWT [30] |

-20 dB |

-15 dB |

5 dB |

0.175 |

| EMD [18] |

-20 dB |

2.85 dB |

22.85 dB |

0.815 |

| EEMD [19] |

-20 dB |

-8.3768 dB |

11.6232 dB |

0.195 |

| LMD [31] |

-20 dB |

6.53 dB |

26.53 dB |

0.901 |

| VMD [20] |

-20 dB |

0.01 dB |

20.01 dB |

0.301 |

| AMHFC [32] |

-20 dB |

-0.06 dB |

19.94 dB |

0.765 |

| Ours |

-20 dB |

25 dB |

45 dB |

0.981 |