Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodologies

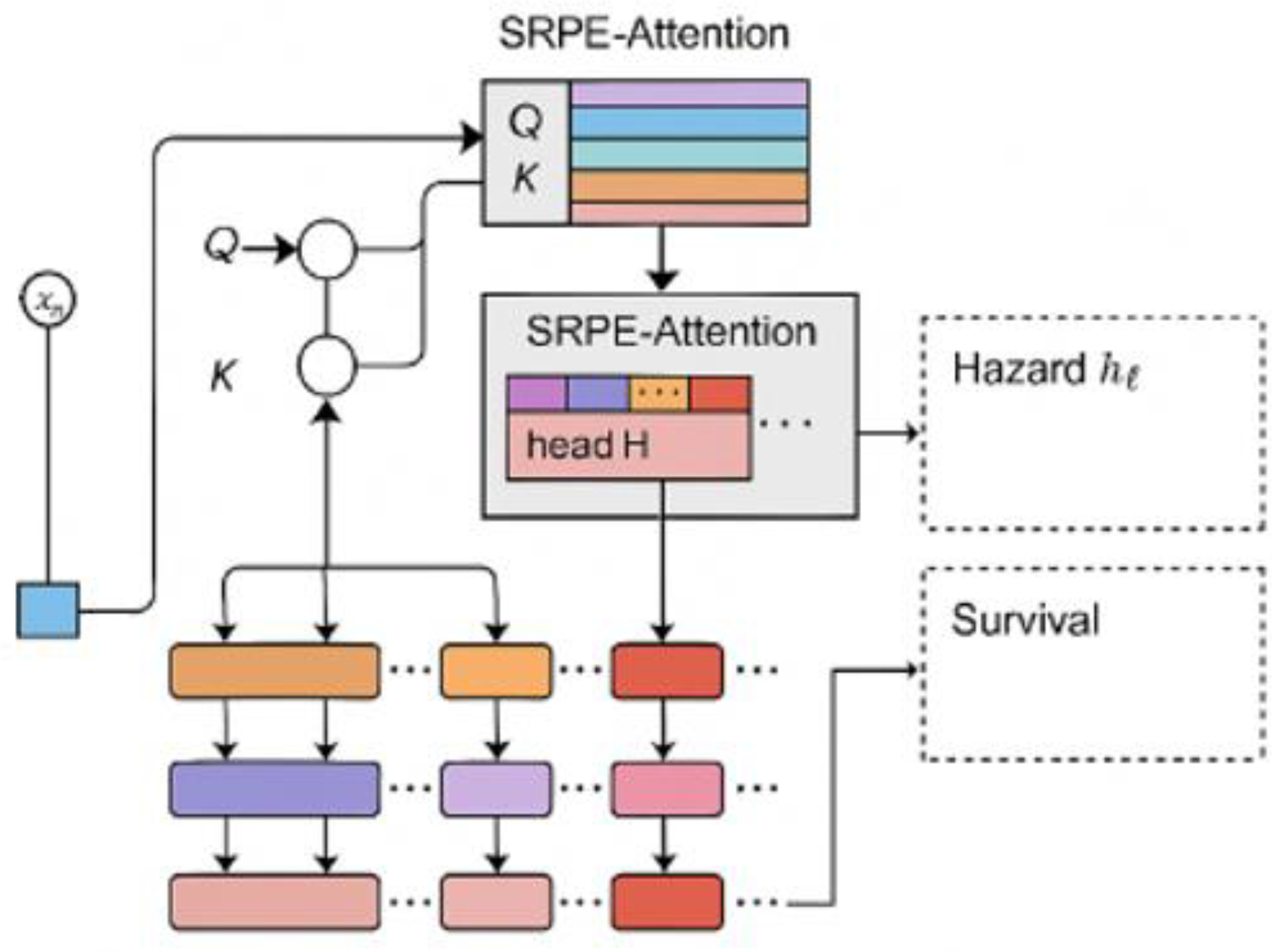

3.1. Relative Position Encoding and Multi-Head Self-Attention Mechanism

- By using this relative position encoding, we can make the model focus on the relative timing structure between different phases. Compared with traditional absolute position encoding, this method can better capture the long-range dependencies between different phases across time periods.

3.2. Maximum Likelihood Loss and Regularization

- This pooling mechanism allows the model to assign different weights based on the importance of each time step, thereby enhancing the model's focus on key time points, especially those that are clinically important before and after adverse events.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

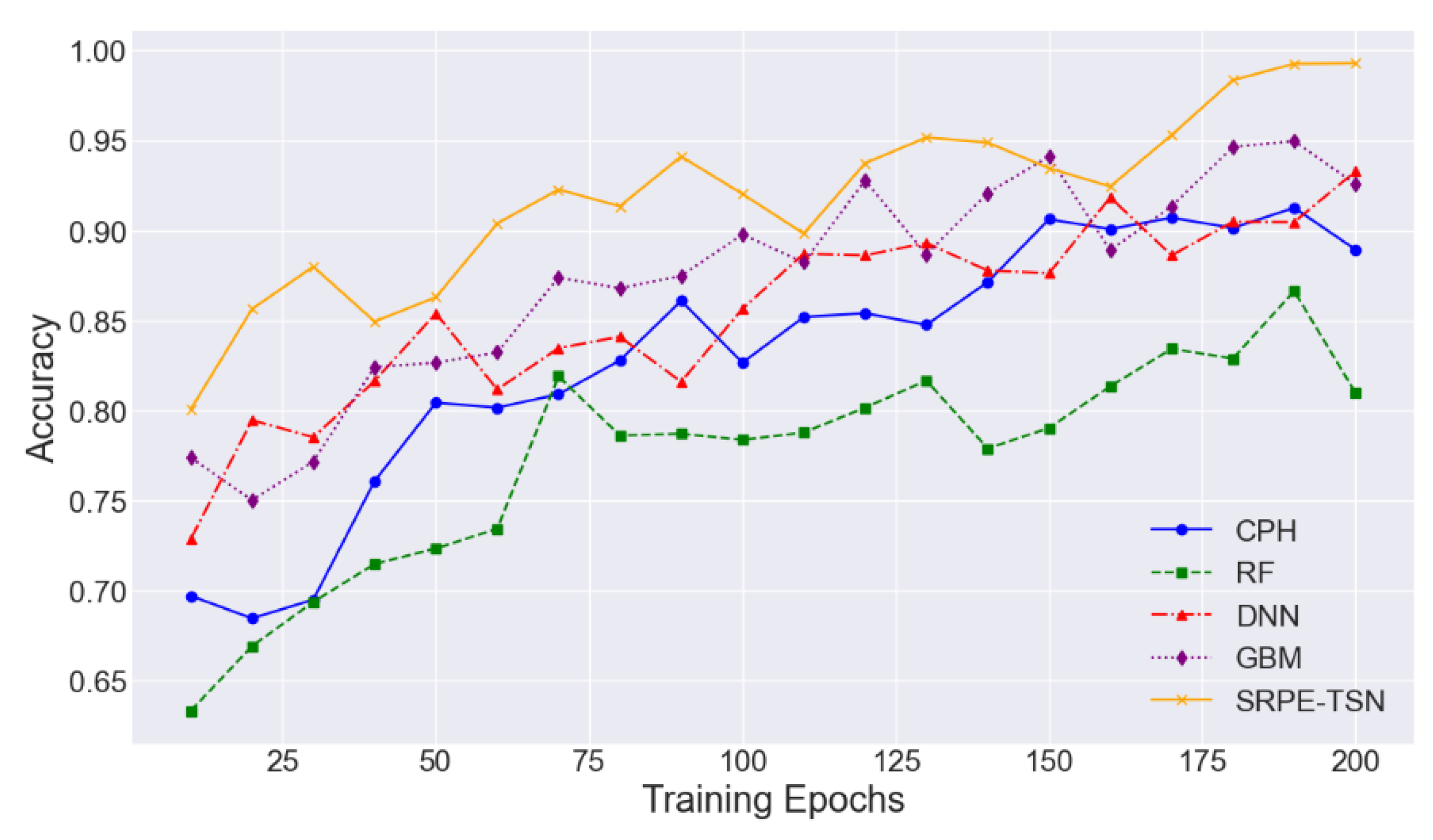

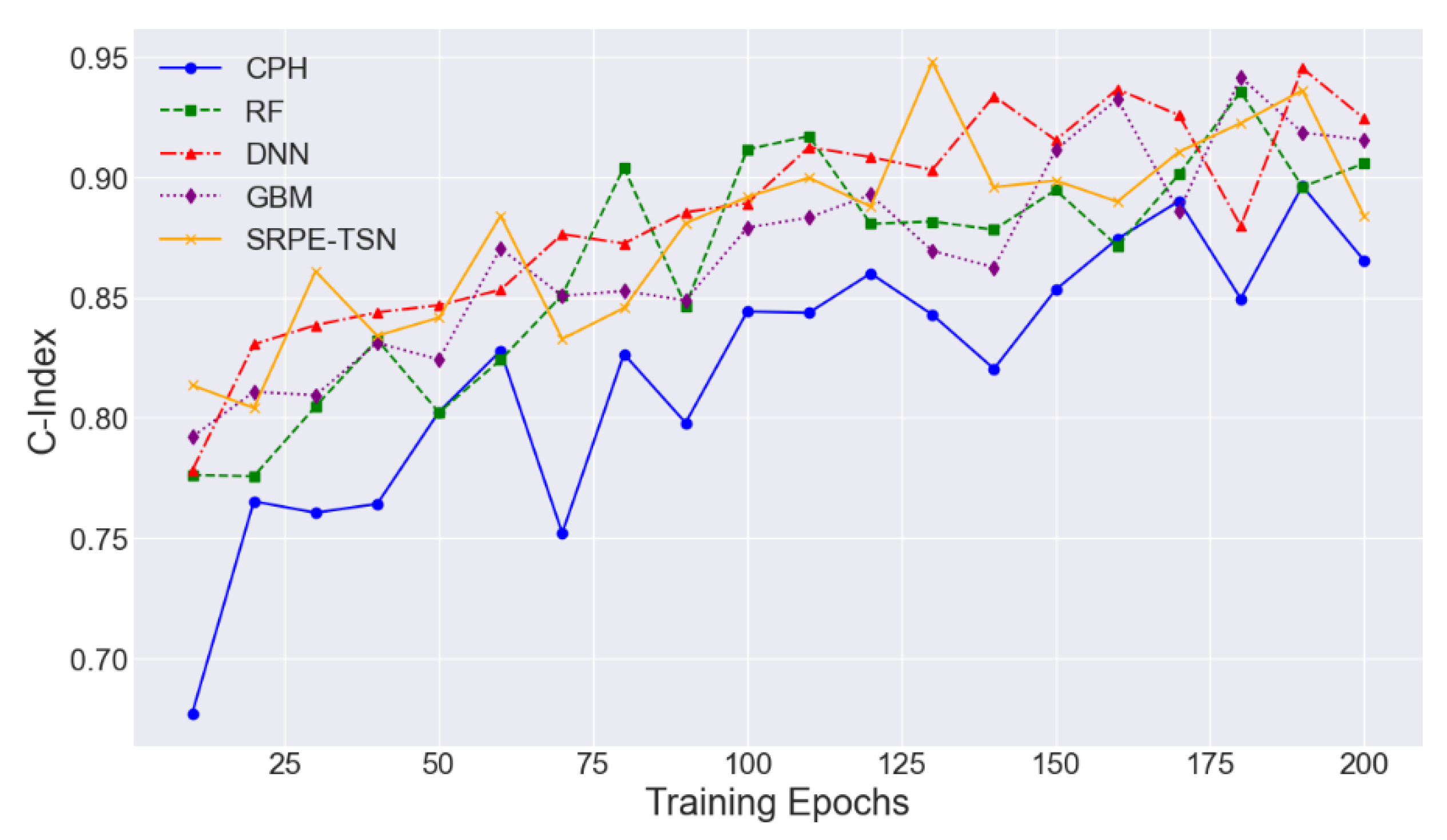

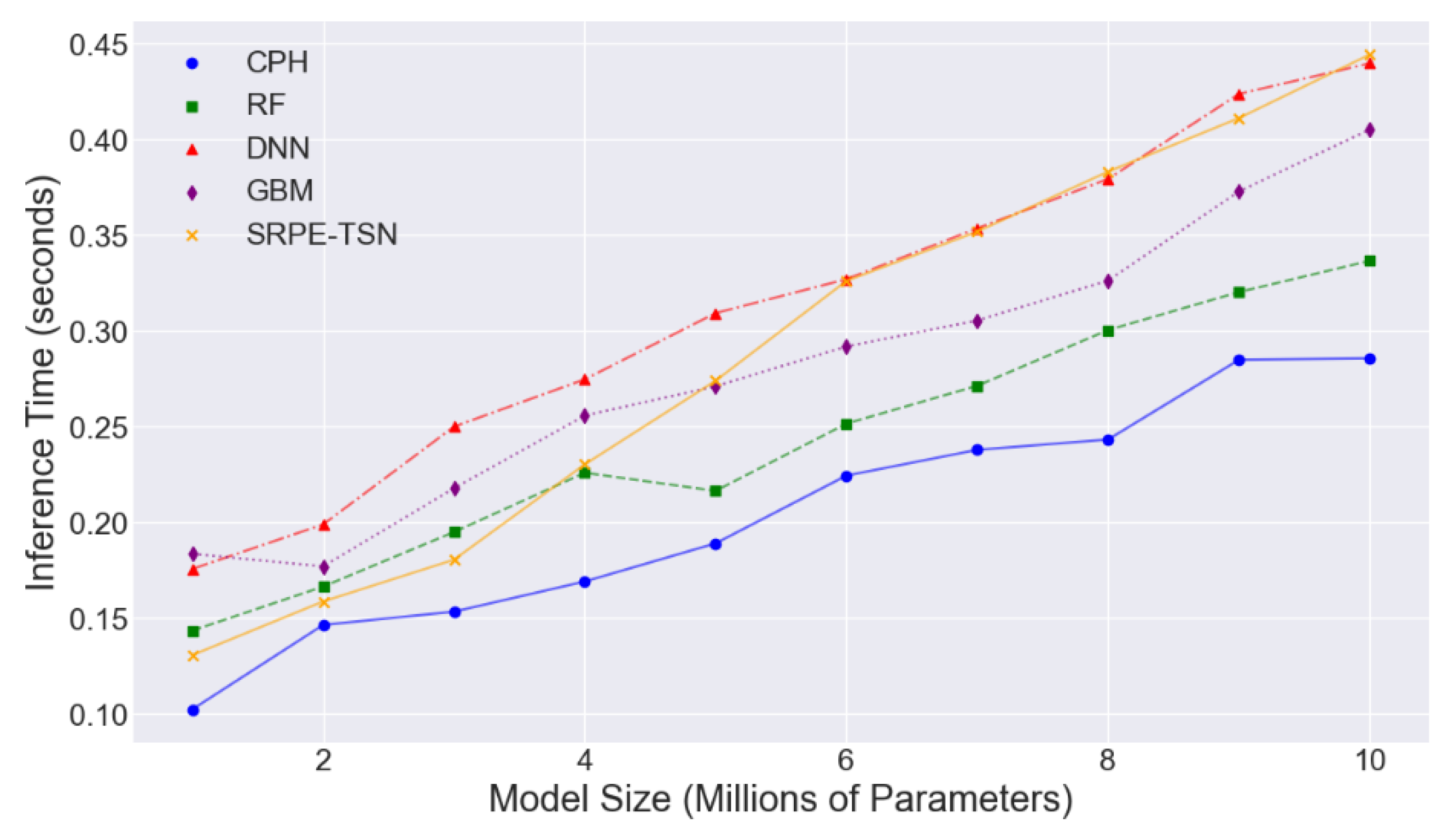

4.2. Experimental Analysis

5. Conclusion

References

- Estupiñán, H.Y.; Berglöf, A.; Zain, R.; & Smith, C.E.; Smith, C. E. Comparative analysis of BTK inhibitors and mechanisms underlying adverse effects. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2021, 9, 630942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aday, J.S.; Davis, A.K.; Mitzkovitz, C.M.; Bloesch, E.K.; & Davoli, C.C.; Davoli, C. C. Predicting reactions to psychedelic drugs: A systematic review of states and traits related to acute drug effects. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2021, 4, 424–435. [Google Scholar]

- Askr, H.; Elgeldawi, E.; Aboul Ella, H.; Elshaier, Y.A.; Gomaa, M.M.; & Hassanien, A.E.; Hassanien, A. E. Deep learning in drug discovery: an integrative review and future challenges. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 5975–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, L.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Jetha, K.; Thakur, R.R.S.; Solanki, H.K.; & Chavda, V.P.; Chavda, V. P. Artificial intelligence in pharmaceutical technology and drug delivery design. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Tu, X.; Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; & Su, Y.; Su, Y. Toward better drug discovery with knowledge graph. Current opinion in structural biology 2022, 72, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S.; Talbot, K.; McDermott, C.J.; Hardiman, O.; Shefner, J.M. . & Turner, M.R. Improving clinical trial outcomes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature Reviews Neurology 2021, 17, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kimmelman, J.; Mandel, D.R.; & Benjamin, D.M.; Benjamin, D. M. Predicting clinical trial results: A synthesis of five empirical studies and their implications. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 2023, 66, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Ascenzo, F.; De Filippo, O.; Gallone, G.; Mittone, G.; Deriu, M.A.; Iannaccone, M. . & Arfat, Y. Machine learning-based prediction of adverse events following an acute coronary syndrome (PRAISE): a modelling study of pooled datasets. The Lancet 2021, 397, 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Qaiser, T.; Lee, C.Y.; Vandenberghe, M.; Yeh, J.; Gavrielides, M.A.; Hipp, J. . & Reischl, J. Usability of deep learning and H&E images predict disease outcome-emerging tool to optimize clinical trials. NPJ precision oncology 2022, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Ostropolets, A.; Makadia, R.; Shoaibi, A.; Rao, G.; Sena, A.G. . & Prieto-Alhambra, D. Characterising the background incidence rates of adverse events of special interest for covid-19 vaccines in eight countries: multinational network cohort study. bmj 2021, 373. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Salvadó, G.; Ashton, N.J.; Tideman, P.; Stomrud, E.; Zetterberg, H. . & Hansson, O. Prediction of longitudinal cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease using plasma biomarkers. JAMA neurology 2023, 80, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chi, W.Y.; Li, Y.D.; Huang, H.C.; Chan, T.E.H.; Chow, S.Y.; Su, J.H. . & Wu, T.C. (). COVID-19 vaccine update: vaccine effectiveness, SARS-CoV-2 variants, boosters, adverse effects, and immune correlates of protection. Journal of biomedical science 2022, 29, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Plana, D.; Palmer, A.C.; & Sorger, P.K.; Sorger, P. K. Independent drug action in combination therapy: implications for precision oncology. Cancer discovery 2022, 12, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Abel, L.; Langford, O.; Monaghan, G.; Aronson, J.K.; Stevens, R.J. . & Sheppard, J.P. Associations between statins and adverse events in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review with pairwise, network, and dose-response meta-analyses. Bmj 2021, 374. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).