1. Introduction

Participation in physical activity (PA) is fundamental for overall well-being across all life stages, including the early years of childhood. The health benefits of regular PA are well-documented, including improved cardiovascular and skeletal health, cognitive function, as well as social and psychological well-being (Eime et al., 2013; Poitras et al., 2016; Sung et al., 2022). Various campaigns, such as Physical Activity Guidelines for American, along with guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO), have outlined PA recommendations for young individuals, encompassing those with and without disabilities (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2018; WHO, 2021). A systematic review indicates that PA is associated with motor and cognitive development, and physical and psychological health in infant and toddlers (Carson et al., 2017). More recently, another systematic review indicates that infants and toddlers with disabilities can develop muscular fitness and motor skills through PA participation (Eichner-Seitz et al., 2023).

Even though there is no international consensus regarding the PA guideline, a few official guidelines indicate that toddlers and preschoolers are encouraged to participate in PA at least 180 minutes per day (National Health Service, 2022; Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, 2021). A systematic review of 20 independent studies confirmed that toddlers' PA varies widely (72.9 to 636.5 min/day) depending on the studies. (Bruijns et al., 2020). While toddlers without disabilities generally comply with PA guidelines (Lee et al., 2017), infants and toddlers with disabilities (ITWD) tend to show physical inactivity (Rivera et al., 2024). Compared to young children without disabilities, young children with disabilities participate in less PA (Ketcheson et al., 2018) and physical play (Logan et al., 2015). This difference in PA may stem from various factors, such as disability-related impaired physical function, a lack of resources and information about accessible facilities and programs, or negative perceptions and attitudes from the public (Ginis et al., 2021; Rimmer et al., 2004). Moreover, studies have indicated that, similar to their peers without disabilities, the levels of PA tend to decrease as children with disabilities grow older (Lounassalo et al., 2019; Sung et al., 2022).

To promote PA participation in ITWD, it is necessary to examine its associated factors. A pivotal approach in examining factors that influence PA participation is the application of the socio-ecological model. This model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex interplay of personal and environmental factors on health-related behaviors including PA (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Only a few studies have specifically focused on individuals with disabilities (Salvador–GarcÍa et al., 2022; Vancampfort et al., 2022). Lee and colleagues (2022) indicated that proximity to parks and schools, along with active parental encouragement and support, significantly enhances PA levels among children with autism spectrum disorder. A systematic review by Sutherland and colleagues (2021) identified 48 correlates of PA, framed within the socio-ecological model, in children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. The results showed that the identified correlates predominantly focused on intrapersonal-level factors, such as motor development, which was positively associated with PA.

While the aforementioned studies provided promising insights into how various factors in the socio-ecological model influence PA behaviors in the disability community, limited research has explored these factors among ITWD. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the factors influencing PA behaviors among toddlers with disabilities based on the socio-ecological model.

2. Methods

The Disability Status Survey in South Korea has been implemented based on Article 31 of the "Welfare of Persons with Disabilities Act" and Article 18 of the "Enforcement Decree of the Welfare of Persons with Disabilities Act." Surveys have been conducted from the first in 1980 to the eleventh in 2020. The purpose of the survey is to understand the population of people with disabilities and the incidence of disabilities, assess their living conditions and welfare needs, and produce foundational data for the establishment and implementation of both short-term and long-term welfare policies for people with disabilities. The survey is conducted every three years, with the 2020 survey being the most recent publicly available data source as of July 2024. The official report of this survey can be found on the website:

https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10411010100&bid=0019&tag=&act=view&list_no=369030. To gather responses from ITWD, the survey employed a caregiver-proxy approach.

2.1. Data and Sample

Data from the Disability Status Survey 2020 was obtained from Ministry of Health and Welfare Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (Kim et al., 2020). A total number of same in the original data was 2,622,950. The age range of the participants was one to 100 years, and the median of the whole sample was 64.00 (SD: 18.32). For the purpose of the current study, participants aged below five years were selected, resulting in 5,825. There was no missing data in the variables used in the current study. Thus, all data was used in the analysis.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable, PA participation, was measured using a question: ‘Have you regularly participated in physical activity for health management in the past year?’, with two response options of yes or no. Other PA-related information including frequency (week), duration (per opportunity), places, types, and barriers were also measured by following questions: 1) How often do you exercise? 2) How many minutes do you exercise per session? 3) Where do you usually exercise? 4) What is the main type of exercise you participate in? (If multiple, based on the exercise you do most frequently), and 5) If you are not currently exercising, what is the main reason for this?

2.2.2. Intrapersonal Level

At the intrapersonal level, several factors were assessed, including, child sex, chronic condition, disability level, and perceived health. Child sex was determined based on their parent's report. The question posed was "What is your child's sex?" with two response options of male and female. This contrasts with a national survey in the United States that includes multiple gender options, as the question about the child's sex was limited to a binary choice. Status of chronic condition was determined based on a question: "Do you have a chronic condition that has persisted for more than three months?", with two response options of yes or no. The classification of disability level was based on the 2019 amendment of the "Disability Welfare Act" and its subordinate regulations for registered disabilities in South Korea. Previously classified into six levels (grades 1 to 6), disability is now divided into two categories: "severe disability" (formerly grades 1 to 3) and "less severe disability" (formerly grades 4 to 6). Perceived health was assessed with the question, "How would you rate your usual state of health?" Participants could choose from five response options: 1) very good, 2) good, 3) normal, 4) bad, and 5) very bad. Responses 1 and 2 were grouped into a 'good' category, while responses 3 through 5 were categorized as 'bad.'

2.2.3. Interpersonal Level

At the interpersonal level, status of brothers and sisters, status of grandparents, and satisfaction of number of friends were assessed. The status of brothers and sisters was measured using the question, ‘Please check all the household members residing in your home: Siblings’. It has two options: yes or no. Similarly, the status of grandparents was measured using the question, ‘Please check all the household members residing in your home: grandparents’. It has two options: yes or no. Satisfaction of number of friends was assessed with the question, " How are you satisfied with the number of friends you have?" Participants could choose from four response options: 1) very satisfied, 2) little satisfied, 3) little unsatisfied, and 4) very unsatisfied. Responses 1 and 2 were grouped into a 'satisfied' category, while responses 3 through 4 were categorized as 'unsatisfied.'

2.2.4. Organizational Level

Several factors were examined at the organizational level, including enrollment of physical therapy, enrollment of occupational therapy, and enrollment of pre-school. The enrollment of physical therapy was measured using the question, ‘Please check if you receive regular physical therapy services’ with two response options: yes or no. The enrollment of occupational therapy was measured using the question, ‘Please check if you receive regular occupational therapy services’ with two response options: yes or no. The enrollment in pre-school was determined by the question, "Please check if your child goes to pre-school," with two response options: yes or no.

2.2.5. Environmental Level

At the environmental level, the area of living was assessed through the question asking participants where they currently live, with three options provided: large city, medium-sized city, and town. The responses for large city and medium-sized city were grouped together under the category "urban," while town was categorized as "rural." Perceived government support was assessed through the survey question, "How much support do you feel you receive from the government or society after registering as a person with a disability?" Four response options were provided: 1) Receiving a lot of support, 2) Receiving some support, 3) Receiving little support, and 4) Receiving no support at all. The responses were dichotomized into two groups: options 1 and 2 indicating 'receiving support', and options 3 and 4 indicating 'receiving insufficient support'.

2.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics including means and percentages, were used to analyze the demographic information of participants. Chi-squared tests were conducted on the demographic data to evaluate the homogeneity of the groups. These Chi-squared tests specifically focused on categorical variables within the demographic data to determine any associations between these variables and the two groups. To examine the associated factors of PA participation in young children with disabilities, decision tree analyses were conducted using Chi-Square Automatic Interaction Detection (CHAID). The demographic characteristics of participants were included as covariates in the CHAID analysis. CHAID is a non-parametric statistical method used in data mining and decision tree analysis, designed to uncover relationships and interactions among categorical variables. The statistical model in this study was specified with the following criteria: 1) Pearson’s Chi-square test; 2) adjustment of significance levels using the Bonferroni method; 3) a significance threshold of p < 0.05 for splitting nodes; 4) a minimum change in expected cell frequencies set at 0.001; 5) a maximum tree depth of three levels; 6) a minimum of 10% of the sample for parent nodes (n = 100) and 5% for child nodes (n = 50); 7) at least 10 folds for cross-validation. Demographic information and health risk behaviors of the caregivers were utilized as input variables for the CHAID analysis.

3. Results

Among all participants, approximately 88.17% were four years old. Of these, 51.64% participated in PA. However, among the three-year-olds, 76.04% did not participate in PA (n = 625). Boys constituted 63.11% of the participants and were more active in PA compared to girls. According to Korea's disability level criteria, 72.63% were categorized as severe. Children with mild disabilities were more active in PA compared to those in the severe group. Cerebral palsy was the most prevalent condition (35.28%), followed by language disorders (24.88%) and hearing impairments (12.22%). Among ITWD, PA prevalence was highest in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder (62.23%), followed by those with cerebral palsy (47.29%) and language disorders (43.50%). Additionally, 42.94% reported that their household monthly income ranged from 300 to 400 Korean won.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants.

| |

|

All (n = 5,826) |

PAP (n = 2,556) |

No PAP (n = 2,730) |

Child age

(%) |

3 years

(n = 625) |

11.83 |

23.96 |

76.04 |

| |

4 years

(n = 4,659) |

88.17 |

51.64 |

48.36 |

Child sex

(%) |

Boys

(n = 3,335) |

63.11 |

58.18 |

41.82 |

| |

Girls

(n = 1,949) |

36.89 |

31.55 |

68.45 |

| Disability level (%) |

Severe

(n = 3,839) |

72.63 |

42.54 |

57.46 |

| |

Mild

(n = 1,446) |

27.37 |

63.83 |

36.17 |

| Disability type (%) |

ASD

(n = 421) |

7.96 |

62.23 |

37.77 |

| |

Cerebral palsy

(n = 1,865) |

35.28 |

47.29 |

52.71 |

| |

ID

(n = 814) |

15.40 |

100 |

0 |

| |

Language

Disorder

(n = 1,315) |

24.88 |

43.50 |

56.50 |

| |

Hearing impairment

(n = 646) |

12.22 |

0 |

100.00 |

| |

Others

(n = 225) |

4.26 |

11.56 |

88.44 |

| Monthly income (10,000won; %) |

150 – 299

(n = 1,641) |

27.44 |

64.96 |

35.04 |

| |

300 – 400

(n = 2,269) |

42.94 |

23.62 |

76.38 |

| |

401 – 600

(n = 1,090) |

20.62 |

87.43 |

12.57 |

| |

>601

(n = 285) |

9.00 |

0 |

100.00 |

3.1. PA Participation

Among all participants, 48.36% reported that they regularly engaged in PA over the past year. Of these, 43.6% participated in PA more than three times per week, with an average duration of 34.78 minutes per session. The most frequent location for PA was at home (38.99%), followed by disability-specific PA centers (18.54%), and public PA centers (15.58%). Furthermore, the most common type of PA was balance-related activities (32.55%), followed by stretching (25.94%), and bicycling (15.58%). If participants reported that they did not currently participate in PA, the most frequent reason was lack of disability knowledgeable professionals (28.78%), lack of disability programs (24.46%), and PA is not priority (19.75%).

Table 2.

Information of PA participation in ITWD (n = 2,556).

Table 2.

Information of PA participation in ITWD (n = 2,556).

| PA frequency (%) |

Two times / week |

More than three times / week |

Almost everyday |

| 33.0 |

43.60 |

22.60

|

| PA minutes |

Mean |

Median |

| 34.78 |

30.00

|

| PA places (%) |

Home |

Outside |

Private PA center |

Public PA center |

Disability PA center |

Others |

| 38.99 |

14.26 |

10.80 |

15.58 |

18.54 |

1.83

|

| PA types (%) |

Walking |

Stretching |

Balance activity |

Bicycling or tricycling |

Swimming |

Others |

| 14.26 |

25.94 |

32.55 |

15.58 |

6.76 |

4.92 |

Table 3.

The percentages of parent-reported barriers to physical activity participation among inactive ITWD (n = 2,730).

Table 3.

The percentages of parent-reported barriers to physical activity participation among inactive ITWD (n = 2,730).

| Economic issue |

No time |

Lack of disability programs |

Lack of disability knowledgeable professionals |

Lack of information |

No community-based PA center |

PA is not priority |

Others |

| 1.97 |

3.83 |

24.46 |

28.78 |

9.91 |

5.00 |

19.75 |

6.31 |

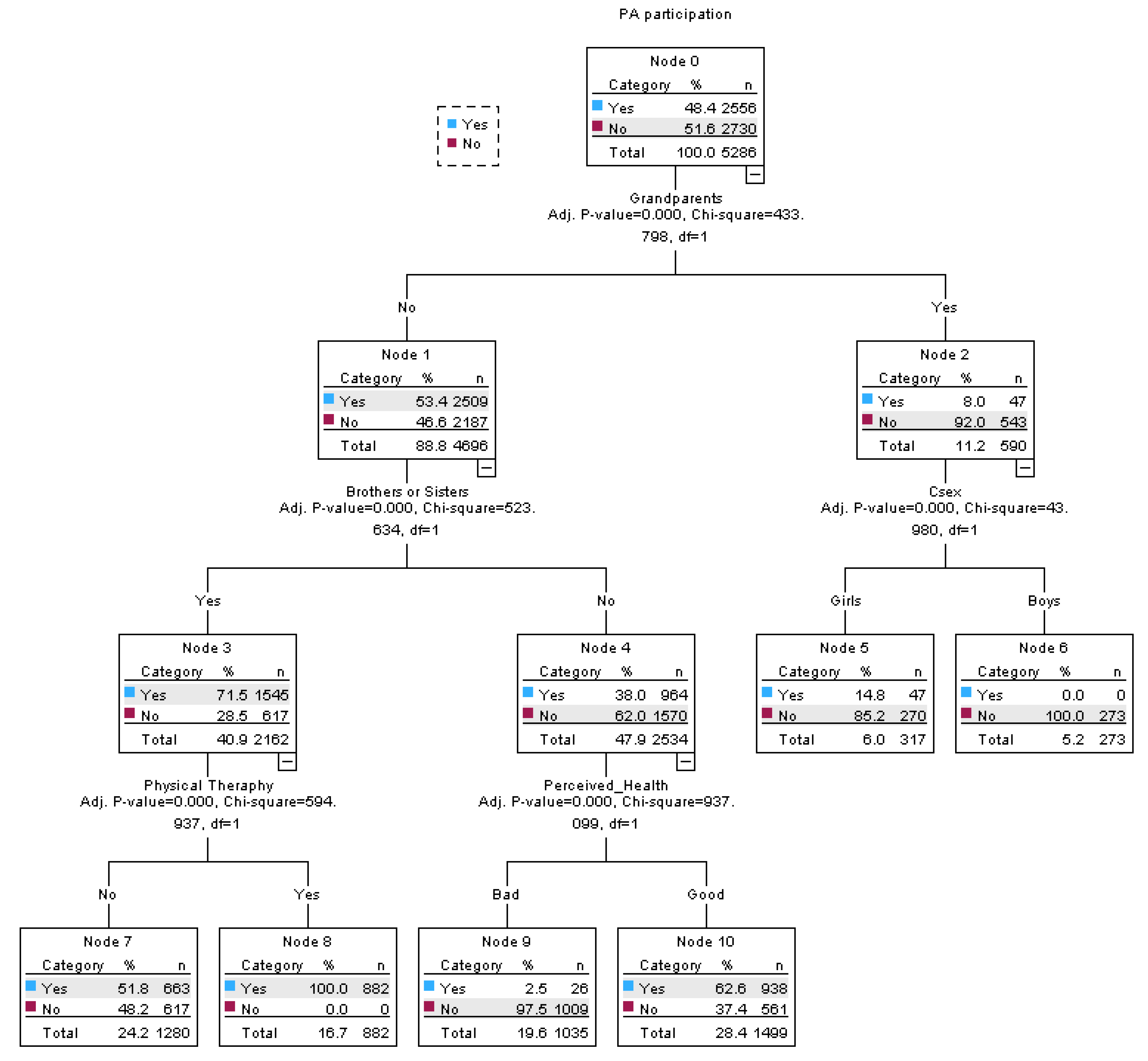

3.2. Decision Tree Analysis

The decision tree analysis conducted to understand the determinants of PA participation yielded a three-level, six-terminal node model. In the study sample, 48.4% of participants reported participating in PA. The initial split in the decision tree is based on whether the participants' grandparents were living together, with those who answered 'Yes' being less likely to participate in PA (8.0%, n = 47) compared to those who answered 'No' (53.4%, n = 2509). Further differentiation within the 'No' category for grandparents is made based on the presence of brothers or sisters, with those having siblings more likely to participate in PA (71.5%, n = 1545). At Node 4, perceived health plays a role, with individuals who perceived their health as 'Bad' being less likely to engage in PA (2.5%, n = 26) than those with a 'Good' perception of health (62.6%, n = 938). Physical therapy was another influential factor belonging to ‘yes’ category under brothers and sisters. Those who attended physical therapy were more likely to participate in PA compared to those who did not. When breaking down by sex after Node 2, it was found that girls were more likely to participate in PA.

Table 4.

Differences in socio-ecological factors of PA between groups.

Table 4.

Differences in socio-ecological factors of PA between groups.

| |

|

All

(n = 5,826) |

PAP

(n = 2,556) |

No PAP

(n = 2,730) |

p-value |

| Interpersonal level |

|

|

|

|

|

Brothers and

sisters |

Yes |

46.06 |

63.48 |

35.46 |

<.001 |

| |

No |

53.94 |

36.52 |

64.54 |

|

| Grandparents |

Yes |

11.17 |

7.97 |

92.03 |

<.001 |

| |

No |

88.83 |

46.56 |

53.44 |

|

Organizational

level |

|

|

|

|

|

| Physical therapy |

Yes |

35.28 |

47.29 |

52.71 |

<.001 |

| |

No |

64.72 |

48.95 |

51.05 |

|

| Pre-kindergarten |

Yes |

37.36 |

56.94 |

43.06 |

<.001 |

| |

No |

62.64 |

43.25 |

56.75 |

|

Environmental

level |

|

|

|

|

|

| Living area |

Rural |

51.57 |

52.90 |

47.10 |

<.001 |

| |

Urban |

48.43 |

43.53 |

56.47 |

|

Government

support |

High |

42.64 |

54.33 |

45.67 |

<.001 |

| |

Low |

57.36 |

43.91 |

56.09 |

|

Figure 1.

The results of decision tree analysis for socio-ecological factors of PA participation in ITWD.

Figure 1.

The results of decision tree analysis for socio-ecological factors of PA participation in ITWD.

4. Discussion

Overall, multi-level factors such as living with grandparents, the status of siblings, the child's sex, enrollment in physical therapy, and perceived health were significant factors influencing PA participation in ITWD. Grandparents were the mostly associated factor with PA participation of ITWD. As grandparents can serve as another caregiver supporting young children’s PA such as doing PA together or taking them to a park (Xie et al., 2018a), it was expected that living with grandparents may be a positive influencing factor. However, ITWD living with grandparents were less likely to participate in PA compared to their counterparts. Although further research is required to explore the mechanisms underlying this association, a few possible explanations can be the low PA support in grandparents.

The first explanation may be differences in grandparents’ perspectives on the appropriateness of engaging PA at home. A semi-structured interview conducted by Parrish and colleagues (2022) revealed that the majority of families interviewed believed it was inappropriate for their preschool-aged children to engage in PA at home, particularly due to specific restrictions set by grandparents against certain types of PA within the house. Moreover, barriers perceived by grandparents, such as the absence of safe and accessible programs/facilities and constraints related to transportation, financial resources, energy, and time, might be attributed to lower PA participation observed from toddlers living with their grandparents (Xie et al., 2018b). A study revealed that co-residence with grandparents may lead to disagreement in support child’s PA, which in turn negatively affect grandparent’s PA support (Xie et al., 2022). The negative influence of living with grandparents on PA in ITWD aligns with previous research indicating that children raised by caregiving grandparents are more likely to be overweight or obese compared to those raised by their parents (Li et al., 2015). In addition, a review study indicates that grandparent involvement negatively affects child’s weight status (Pulgaron et al., 2016). In addition, co-residence of grandparents was positively associated with screen time in young children (Xie et al., 2021). Grandparents may have physical challenges in doing physical activity with their grandchildren (Duflos et al., 2024). They perceived themselves as storyteller or historian rather than active playmates (Swartz & Crowley, 2004).

Among ITWD who did not live with their grandparents, those with siblings were more likely to engage in PA compared to their peers without siblings. This finding is supported by studies that have revealed the influence of siblings on PA levels in youth living in the same household (Edwards et al., 2015; Raudsepp & Viira, 2000). Siblings may shape and foster positive PA preferences, particularly when multiple siblings are present, creating opportunities for engagement and providing supervision during activities (Kracht & Sisson, 2018). They serve as role models, and ITWD may observe and imitate their siblings' behaviors, including engaging in PA (Bontinck, Warreyn, Van der Paelt, Demurie, & Roeyers, 2018). Interactions with siblings can positively influence the social support and physical development of children with disabilities (Cuskelly & Gunn, 2003). Having siblings may foster a more relaxed and inclusive environment, encouraging greater physical engagement (Blazo & Smith, 2018).

Another associated factor was enrolling in physical therapy. ITWD who received regular physical therapy were more likely to participate in PA compared to those who did not. Regular engagement in PA through physical therapy can help individuals with disabilities incorporate PA into their daily lives (Sorsdahl, Moe-Nilssen, Kaale, Rieber, & Strand, 2010; Toscano et al., 2022). Studies have shown that consistent, structured interventions can lead to higher levels of PA beyond therapy sessions (Bania, Dodd, & Taylor, 2011). In addition, physical therapy often involves training and educating parents and caregivers on how to support and encourage their child's PA. This may lead to more opportunities for the child to be active at home and participate in community activities, benefiting children with disabilities (Lillo-Navarro et al., 2015). For example, parents serve as a co-therapist so do PA with their child at home such as balance activity or stretching.

The last important finding of the current study was the perceived barriers to physical activity (PA) for toddlers with disabilities. The study revealed that the most significant barriers to PA participation among infants and toddlers with disabilities (ITWD) include a lack of professionals knowledgeable about disabilities, an absence of disability-specific programs, and the perception that PA is not a priority. These findings are consistent with the reports from Rimmer et al. (2004), who indicated that individuals with disabilities face over 100 barriers that hinder their PA participation, as compared with their typically developing peers. These barriers consist of limited information about accessible programs, negative attitudes from the public, and lack of knowledge, education, and training among fitness professionals (Rimmer et al., 2004). Further, a systematic review analyzed factors related to PA participation among individuals with disabilities based on the socio-ecological model, highlighting institutional barriers such as program availability, as well as the knowledge of people within institutions/organizations, encountered in this population (Martin Ginis et al., 2016). Lastly, in Asian culture particularly, ITWD might spend more time receiving treatment and other therapies (e.g., speech therapy) (Chiu & Turnbull, 2014), and might force parents to restrict the amount of time their child spent in PA participation (Lin et al., 2017). Collectively, these findings underscore the multifaced nature of the barriers to PA among ITWD and suggest the need for multifaceted interventions that address these specific barriers.

This study's strength lies in its comprehensive exploration of the obstacles and facilitators of physical activity for children with disabilities. Notably, it is one of the pioneering studies to incorporate the socio-ecological model to delineate the factors associated with PA participation among ITWD.

Data availability statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest disclosure

None.

Ethics approval statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yong-In University under protocol number 2-1040966-AB-N-01.

References

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. (2021, May 6). Physical activity and exercise guidelines for infants, toddlers and preschoolers (birth to 5 years). https://www.health.gov.au/topics/physical-activity-and-exercise/physical-activity-and-exercise-guidelines-for-all-australians/for-infants-toddlers-and-preschoolers-birth-to-5-years.

- Alhumaid, M. M. (2024). Parental physical activity support for parents of children with.

- disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon, 10(7), e29351. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D., Dumont, S., Jacobs, P., & Azzaria, L. (2007). The personal costs of caring for a child with a disability: a review of the literature. Public Health Reports, 122(1), 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R., & Sweeney, R. (2023). Principles and strategies of inclusive physical activity: a European Delphi study. Journal of Public Health, 31(12), 2021-2028. [CrossRef]

- Bania, T., Dodd, K. J., & Taylor, N. (2011). Habitual physical activity can be increased in people with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Clinical rehabilitation, 25(4), 303-315. [CrossRef]

- Blazo, J. A., & Smith, A. L. (2018). A systematic review of siblings and physical activity experiences. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 122-159. [CrossRef]

- Bontinck, C., Warreyn, P., Van der Paelt, S., Demurie, E., & Roeyers, H. (2018). The early development of infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder: Characteristics of sibling interactions. PloS one, 13(3), e0193367. [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R. C., Baker, E. A., Housemann, R. A., Brennan, L. K., & Bacak, S. J. (2001). Environmental and policy determinants of physical activity in the United States. American journal of public health, 91(12), 1995-2003. [CrossRef]

- Carver, A., Timperio, A., Hesketh, K., & Crawford, D. (2012). How does perceived risk mediate associations between perceived safety and parental restriction of adolescents’ physical activity in their neighborhood? International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 9, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E. R., Sang, M. K., Sigei, T. K., Dingwall, H. L., Okutoyi, P., Ojiambo, R.,... Lieberman, D. E. (2016). Physical fitness differences between rural and urban children from western K enya. American Journal of Human Biology, 28(4), 514-523. [CrossRef]

- Clinch, J., & Eccleston, C. (2009). Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: assessment and management. Rheumatology, 48(5), 466-474. [CrossRef]

- Cortis, C., Puggina, A., Pesce, C., Aleksovska, K., Buck, C., Burns, C.,... Ciarapica, D. (2017). Psychological determinants of physical activity across the life course: A" DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity"(DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. PloS one, 12(8), e0182709. [CrossRef]

- Cuskelly, M., & Gunn, P. (2003). Sibling relationships of children with Down syndrome: Perspectives of mothers, fathers, and siblings. American journal on mental retardation, 108(4), 234-244. [CrossRef]

- Eime, R. M., Payne, W. R., Casey, M. M., & Harvey, J. T. (2010). Transition in participation in sport and unstructured physical activity for rural living adolescent girls. Health education research, 25(2), 282-293. [CrossRef]

- Fiss, A. C. L., & Effgen, S. K. (2007). Use of groups in pediatric physical therapy: survey of current practices. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 19(2), 154-159. [CrossRef]

- Fragala-Pinkham, M. A., O'Neil, M. E., Bjornson, K. F., & Boyd, R. N. (2012). Fitness and physical activity in children and youth with disabilities. In (Vol. 2012): Hindawi.

- Hanifah, L., Nasrulloh, N., & Sufyan, D. L. (2023). Sedentary Behavior and Lack of Physical Activity among Children in Indonesia. Children, 10(8), 1283. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M. P., DeVille, N. V., Elliott, E. G., Schiff, J. E., Wilt, G. E., Hart, J. E., & James, P. (2021). Associations between nature exposure and health: a review of the evidence. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(9), 4790. [CrossRef]

- Karakaş, G., & Yaman, C. (2014). The role of family in motivating the children with disabilities to do sport. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152, 426-429. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. A., McKenzie, G., Holmes, C., & Shields, N. (2022). Social support initiatives that facilitate exercise participation in community gyms for people with disability: a scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(1), 699. [CrossRef]

- King, A. C., Jeffery, R. W., Fridinger, F., Dusenbury, L., Provence, S., Hedlund, S. A., & Spangler, K. (1995). Environmental and policy approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention through physical activity: issues and opportunities. Health Education Quarterly, 22(4), 499-511. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Lee, M., Oh, U., Oh, D., Hwang, J., Oh, M., Kim, J., Lee, Y., Kang, D., Kwan, S., Baek, E., Yoon, S., & Lee, S. (2020). Disability Status Survey. Ministry of Health and Welfare Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

- Ku, B., & Rhodes, R. E. (2020). Physical activity behaviors in parents of children with disabilities: A systematic review. Research in developmental disabilities, 107, 103787. [CrossRef]

- Law, M., Petrenchik, T., King, G., & Hurley, P. (2007). Perceived environmental barriers to recreational, community, and school participation for children and youth with physical disabilities. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 88(12), 1636-1642. [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Navarro, C., Medina-Mirapeix, F., Escolar-Reina, P., Montilla-Herrador, J., Gomez-Arnaldos, F., & Oliveira-Sousa, S. L. (2015). Parents of children with physical disabilities perceive that characteristics of home exercise programs and physiotherapists’ teaching styles influence adherence: a qualitative study. Journal of physiotherapy, 61(2), 81-86. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Green, R. J. (2023). The effect of exposure to nature on children’s psychological well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 81, 127846. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A., Fletcher, G., Farmer, J., Kenny, A., Bourke, L., Carra, K., & Bariola, E. (2016). Participation in rural community groups and links with psychological well-being and resilience: a cross-sectional community-based study. BMC psychology, 4, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, S. S. (2016). Does a physiotherapy programme of gross motor training influence motor function and activities of daily living in children presenting with developmental coordination disorder? South African Journal of Physiotherapy, 72(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Malina, R. M., Reyes, M. E. P., Tan, S. K., & Little, B. B. (2008). Physical activity in youth from a subsistence agriculture community in the Valley of Oaxaca, southern Mexico. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 33(4), 819-830. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S. J., & Ramirez, E. (2011). Reducing sedentary behavior: a new paradigm in physical activity promotion. American Journal of lifestyle medicine, 5(6), 518-530. [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K. A., Ma, J. K., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., & Rimmer, J. H. (2016). A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health psychology review, 10(4), 478-494. [CrossRef]

- McHale, F., Ng, K., Taylor, S., Bengoechea, E., Norton, C., O’Shea, D., & Woods, C. (2022). A systematic literature review of peer-led strategies for promoting physical activity levels of adolescents. Health Education & Behavior, 49(1), 41-53. [CrossRef]

- Monton, K., Broomes, A.-M., Brassard, S., & Hewlin, P. (2022). The role of sport-life balance and well-being on athletic performance. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 21(1), 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P., Cleary, S., Dutia, I., Bow, K., & Shields, N. (2023). Community-based physical activity interventions for adolescents and adults with complex cerebral palsy: A scoping review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 65(11), 1451-1463. [CrossRef]

- NHS. (2022, June 1). Physical activity guidelines for children (under 5 years). NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/physical-activity-guidelines-children-under-five-years/.

- Owen, K. B., Smith, J., Lubans, D. R., Ng, J. Y., & Lonsdale, C. (2014). Self-determined motivation and physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive medicine, 67, 270-279. [CrossRef]

- Palisano, R. J., Chiarello, L. A., King, G. A., Novak, I., Stoner, T., & Fiss, A. (2012). Participation-based therapy for children with physical disabilities. Disability and rehabilitation, 34(12), 1041-1052. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z., Hu, L., Yu, J. J., Yu, Q., Chen, S., Ma, Y.,... Zou, L. (2020). The influence of social support on physical activity in Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of exercise self-efficacy. Children, 7(3), 23. [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J. A., & Rowland, J. L. (2008). Physical activity for youth with disabilities: a critical need in an underserved population. Developmental neurorehabilitation, 11(2), 141-148. [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, R. R., Ridley, K., Guagliano, J. M., & Rosenkranz, S. K. (2023). Physical activity capability, opportunity, motivation and behavior in youth settings: theoretical framework to guide physical activity leader interventions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 529-553. [CrossRef]

- Rowland, J. L., Fragala-Pinkham, M., Miles, C., & O'Neil, M. E. (2015). The scope of pediatric physical therapy practice in health promotion and fitness for youth with disabilities. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 27(1), 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J., Ball, K., Crawford, D., Booth, M., Telford, A., Hume, C.,... Worsley, A. (2005). Reducing sedentary behaviour and increasing physical activity among 10-year-old children: overview and process evaluation of the ‘Switch-Play’intervention. Health promotion international, 20(1), 7-17. [CrossRef]

- Sango, P. N., Bello, M., Deveau, R., Gager, K., Boateng, B., Ahmed, H. K., & Azam, M. N. (2022). Exploring the role and lived experiences of people with disabilities working in the agricultural sector in northern Nigeria. African Journal of Disability, 11, 897. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P., Southerland, J. L., & Slawson, D. L. (2019). Social Support for Physical Activity for High Schoolers in Rural Southern Appalachia. Southern Medical Journal, 112(12), 626-633. [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D. F., Franco, L., Lin, B. B., Gaston, K. J., & Fuller, R. A. (2016). The benefits of natural environments for physical activity. Sports medicine, 46(7), 989-995. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, J., Legg, D., & Pritchard-Wiart, L. (2021). Do paediatric physiotherapists promote community-based physical activity for children and youth with disabilities? A mixed-methods study. Physiotherapy Canada, 73(1), 66-75. [CrossRef]

- Siebert, E. A., Hamm, J., & Yun, J. (2017). Parental influence on physical activity of children with disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 64(4), 378-390. [CrossRef]

- Sit, C., Aubert, S., Carty, C., Silva, D. A. S., López-Gil, J. F., Asunta, P.,... Nicitopoulos, K. P. A. (2022). Promoting physical activity among children and adolescents with disabilities: the translation of policy to practice internationally. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 19(11), 758-768. [CrossRef]

- Sollerhed, A.-C., Andersson, I., & Ejlertsson, G. (2013). Recurrent pain and discomfort in relation to fitness and physical activity among young school children. European journal of sport science, 13(5), 591-598. [CrossRef]

- Sorsdahl, A. B., Moe-Nilssen, R., Kaale, H. K., Rieber, J., & Strand, L. I. (2010). Change in basic motor abilities, quality of movement and everyday activities following intensive, goal-directed, activity-focused physiotherapy in a group setting for children with cerebral palsy. BMC pediatrics, 10, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S. R., Colwell, T., & Zhao, Y. (2008). Motives for participation and importance of social support for athletes with physical disabilities. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 2(4), 317-336. [CrossRef]

- Swartz, M., & Crowley, K. (2004). Parent beliefs about teaching in a children’s museum. Visitor Studies, 7(2), 1–16.

- Te Velde, S. J., Lankhorst, K., Zwinkels, M., Verschuren, O., Takken, T., de Groot, J., & Wittink, H. s. g. F. B. J. d. G. K. L. T. N. T. T. D. S. O. V. J. V.-M. M. V. H. (2018). Associations of sport participation with self-perception, exercise self-efficacy and quality of life among children and adolescents with a physical disability or chronic disease—a cross-sectional study. Sports medicine-open, 4, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Liu, L., Wang, X., Zhang, X., Zhai, Y., Wang, K., & Liu, J. (2021). Urban-rural differences in physical fitness and out-of-school physical activity for primary school students: A county-level comparison in western China. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(20), 10813. [CrossRef]

- Toscano, C. V., Ferreira, J. P., Quinaud, R. T., Silva, K. M., Carvalho, H. M., & Gaspar, J. M. (2022). Exercise improves the social and behavioral skills of children and adolescent with autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 1027799. [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J., Flowers, E., Ball, K., Deforche, B., & Timperio, A. (2020). Exploring children’s views on important park features: A qualitative study using walk-along interviews. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(13), 4625. [CrossRef]

- Wakely, L., Langham, J., Johnston, C., & Rae, K. (2018). Physical activity of rurally residing children with a disability: A survey of parents and carers. Disability and health journal, 11(1), 31-35. [CrossRef]

- Woods, C. B., Kelly, L., Volf, K., Gelius, P., Messing, S., Forberger, S.,... Bengoechea, E. G. (2022). S09-4 The development of the Physical Activity Environment Policy Index (PA-EPI): a tool for monitoring and benchmarking government policies and actions to improve physical activity. European Journal of Public Health, 32(Supplement_2), ckac093. 048. [CrossRef]

- Wright, A., Roberts, R., Bowman, G., & Crettenden, A. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation for children with physical disability: comparing and contrasting the views of children, young people, and their clinicians. Disability and rehabilitation, 41(13), 1499-1507. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).