1. Introduction

The basic functions related to the maintenance of daily human life are controlled by endogenous rhythms with a cycle of approximately 24 hours, which are called "circadian rhythms (CRs)". Humans get sleepy, wake up, feel hungry, and eat at roughly the same time every day. This natural rhythm and schedule of life that everyone follows is due to the CR biological clock that exists in the human body [

1,

2]. As the CR is observed even when at rest, when there is no change in light or temperature, it is clear that living organisms have a clock mechanism in their bodies called the "biological clock." The CR is an oscillation with a cycle of approximately 24 hours, which has been observed to participate in almost all physiological functions of the human brain and body [

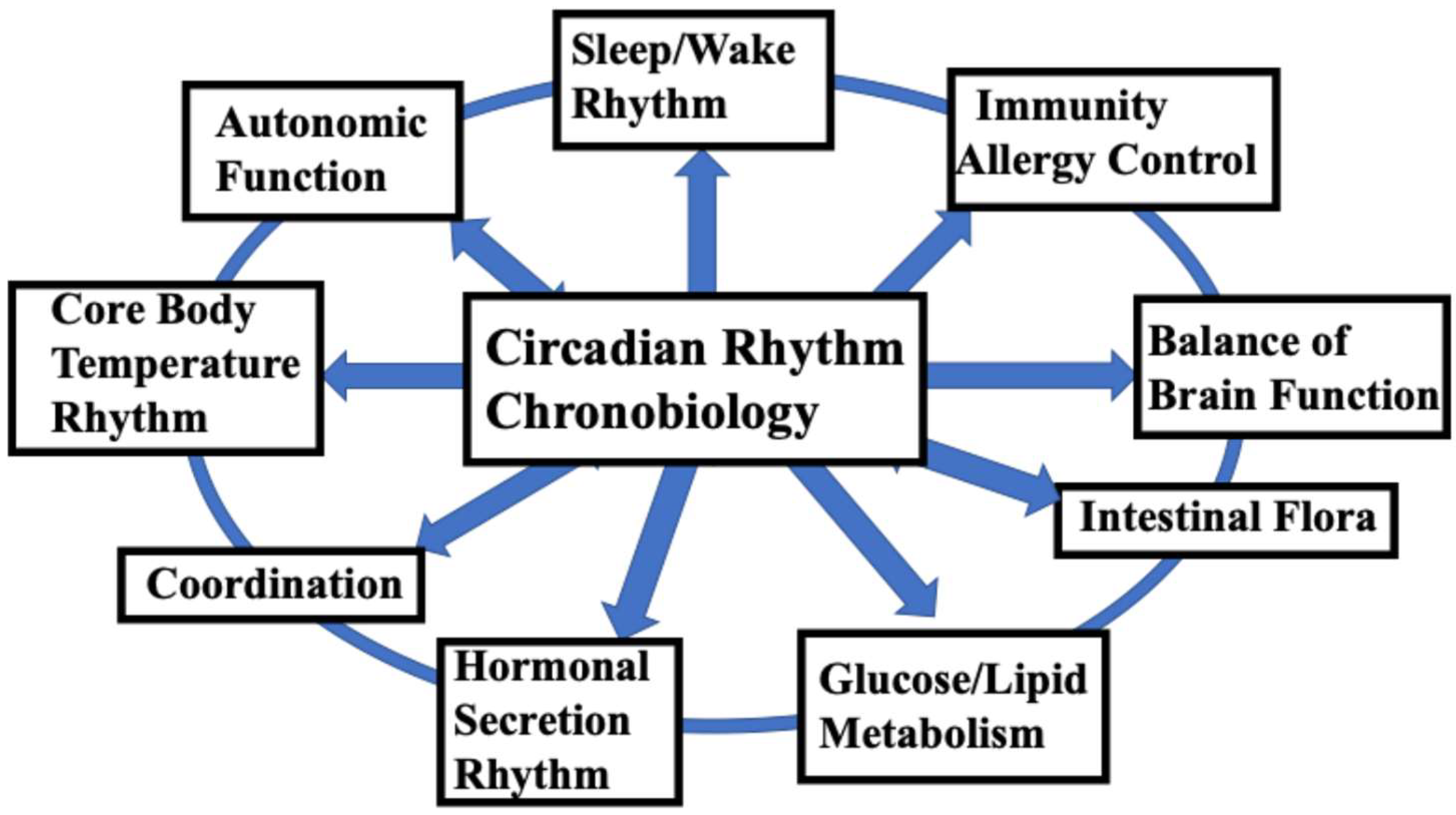

1]. In particular, the central mechanism of the human circadian rhythm biological clock, present in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), controls life-sustaining functions such as the sleep/wake cycle, thermoregulation, hormone secretion, energy metabolism, immune function, and autonomic nervous function, and is an extremely important mechanism related to the maintenance of human life (

Figure 1). In addition to CR, biological clocks include rhythms with cycles shorter than 24 hours (ultradian rhythm, UR), rhythms of approximately half a day (12 hours) such as those observed during naps (circasemidian rhythms), circatidal rhythms (12.4 hours), rhythms with cycles of approximately one month (circalunar rhythms = approximately 1 month), and circannual rhythms (approximately one year). For more details on these biological rhythms, please refer to the many well-known specialist books published to date on these topics.

This review focuses on the relationship between the CR, which is the most relevant rhythm to human life, and the UR, which is the basis of CR formation. The suprachiasmatic nucleus, which is the basis of the circadian clock, is present by the middle of pregnancy in human and non-human primate fetuses [

3,

4]. In other words, the formation of the CR center in the suprachiasmatic nucleus begins during fetal life and is almost complete during early childhood [

5,

6,

7]. The best-known biological clock is the circadian clock, which actively changes the internal environment to match the approximately 24-hour light–dark cycle caused by the rotation of the Earth. The human circadian clock was once thought to be about 25 hours; however, in 1999, it was reported that the biological human CR is 24.18 hours (being shorter in some people). This fact is now widely accepted [

8].

Fortunately, humans have a system (entrainment mechanism) that synchronizes the timing of their biological clocks to the external 24-hour light–dark cycle, although there is a slight deviation associated with the duration of Earth's rotation [

9]. We live in a modern society on Earth and lead lives involving school and society. Therefore, if we can align our biological clocks with the rhythms of modern society, we can adapt to a comfortable daily life without any interference with our mental and physical functions, thus maintaining our mental and physical health throughout our lives. However, disruptions in the CR can cause a variety of mental and physical health disorders at various stages of life [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. This suggests that the function of the human biological clock plays a central and important role in maintaining a comfortable daily life and mental and physical health. In this study, I would like to discuss and propose what is necessary for the proper development of the biological clock, in order to promote the balanced mental and physical development of children and to maintain healthy states throughout their lives.

2. Two CR Biological Clocks

There are two main types of biological clocks: 1) the central clock (also called the master clock) [

1,

15,

16,

17] and 2) the peripheral clock [

18,

19]. As almost all cells in the human body have clock-like functions [

11,

20], some people consider the intracellular clock to be the third clock. However, in general, the intracellular clock is often interpreted as being included in the peripheral clock. In mammals, the 24-hour rhythm of physiological functions and behavior is controlled by a master clock located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus in the brain, and is synchronized by a "slave" oscillator of similar molecular composition located in most cells in the body [

21]. In other words, these two main clocks communicate and cooperate with each other to control the rhythms of the body. Therefore, the state in which these clocks each function to work together is important for maintaining the balanced functioning of the entire body. For more details, please refer to other relevant literature; in this review, only an overview of these clocks is provided.

2.1. Central Clock (Master Clock)

The center of the biological clock is known to be the SCN in the hypothalamus of the brain, a tissue only 2 mm in size, located in each side of the brain [

22]. This tissue is composed of a collection of about 10,000 nerve cells, which exist in pairs on the left and right sides of the brain, for a total of 20,000 cells. The cells that make up these biological clocks keep time through the action of a specific group of genes called clock genes. The left and right tissues work together to tell the time, such that the left and right tissues cannot function separately. The SCN is thought to be the center for adjusting the time of the peripheral clocks (including the intracellular clocks described below), and to control the rhythms and cell division of organs throughout the body. In other words, the role of the central clock is to direct the peripheral cells and form an overall strong rhythm. The SCN functions as a master pacemaker that sets the timing of rhythms by regulating neural activity, body temperature, and hormonal signals [

22].

2.2. Peripheral Clocks

Peripheral clocks are present in almost all organs, tissues, and cells throughout the body, except for sex cells. These cells also keep their own time, and perform a life-sustaining function. While the central clock is reset by light, the peripheral clock is also influenced by factors other than light, such as diet and exercise [

18,

19]. Although the induction of food-predictive activity rhythms by daily feeding schedules does not require the SCN, feeding rhythms show clear circadian clock-controlled properties. The mechanisms of the circadian clock and metabolic processes are clearly closely related. The feeding behavior of many organisms is strongly influenced by circadian rhythms. Restricting feeding is a very strong stimulus for synchronizing the circadian clock. Importantly, daily disruptions to eating behavior cause health problems such as obesity and diabetes [

23]. In other words, time variability and timing deviations in feeding have a detrimental effect on metabolic health. Conversely, even if the nutritional balance is somewhat poor, regular meals reduce the risk of metabolic problems [

24]. While it is important to eat meals, it is also very important to eat at regular times.

The human body is made up of 37 trillion cells (some say 35 or 60 trillion), and almost every cell has a molecular clock (including lymphocytes), which forms its own rhythm [

11,

20,

25]. It is thought that when CRs are disrupted, clocks become out of sync among organs, tissues, and cell groups throughout the body [

11]. It is believed that the disruption of entire body's biological clock can lead to adverse physical and mental health outcomes.

3. The Process of CR Biological Clock Formation

3.1. Formation of Fetal Ultradian Rhythm (UR)

The CR is based on an appropriate ultradian rhythm [

26]; thus, let us first consider the formation of ultradian rhythms.

Among biological rhythms, rhythms with a period of several tens of minutes to several hours (up to 20 hours) that is shorter than a 24-hour period are called ultradian rhythms. The development of the ultradian rhythm center in the pons and medulla oblongata begins around the 28th to 30th week of fetal development [

27,

28]. It is also related to the development of sleep (mainly REM sleep), and may serve as the basis of the CR formed after birth. In order to form a healthy CR biological clock from fetal development to postnatal life, it is important that the UR is firmly formed around the 30th week of gestation and that the associated REM sleep develops appropriately, which leads to the smooth development of CR after birth [

26,

27]. The UR control sites (the pons and medulla oblongata) begin to function around 28-30 weeks and mature around 37 weeks of pregnancy [

28]. During fetal life, the cycle of REM sleep (active) and non-REM sleep (quiet) is basically a 40-50-minute UR [

28].

3.2. Formation of CRs During Fetal Development

In order to maintain brain function that can adapt to modern school/social life rhythms after birth, humans begin to adjust their daily rhythms to adapt to social life even during fetal development [

29]. The formation of the circadian clock begins around the 20th to 22nd week of fetal development, when diurnal variations appear in heart rate, fetal movements, and respiratory movements, and circadian clocks appear in cells, tissues, and organs throughout the body [

30]. However, the rhythms of each of these organs are not unified throughout the body, and each operates autonomously [

30,

31]. As the fetus is a part of the mother's body and grows according to the mother's daily rhythm, the mother's lifestyle naturally affects the formation of the fetus's own biological clock during pregnancy [

29]. The intrauterine environment is rhythmic in nature, and the fetus is affected by changes in temperature, substrate, and the circadian rhythms of various maternal hormones. Meanwhile, the fetus develops an endogenous circadian system to prepare for life in an external environment where light, food availability, and other environmental factors change repeatedly and predictably every 24 hours [

32].

3.3. From URs to Circadian Rhythms

Newborn babies up to one month of birth sleep for about 14-17 hours a day [

33], with almost no distinction between day and night. However, the CR that functions autonomously in each tissue and organ is not uniform in each individual and disappears at birth. In the neonatal period, babies spend their days with a sleep/wake rhythm that follows a 3-4-hour UR [

26,

34,

35,

36]. This rhythm in the neonatal period is one of the URs and corresponds to the REM and non-REM sleep cycle, which is a 90-minute cycle in human adults. This rhythm is shorter in children, 40-50 minutes in the fetal and neonatal periods, 40-60 minutes until infancy, and then gradually approaches the 90-minute rhythm of adults by around 10 years of age. URs are divided into four groups according to their length: Group I, 5-30 min; Group II, 30-60 min; Group III, 60-100 min; and Group IV, >100 min [

27]. Thus, the sleep/wake rhythm is not originally a CR but, instead, an UR that is shorter than the CR. The sleep/wake rhythm, which is only found in relatively advanced organisms with brains, is of recent origin and therefore does not belong to the original biological CR. It takes several weeks after birth for the biological CR and the sleep/wake rhythm to correlate, and until then, babies live with the original sleep/wake rhythm (UR). Shortly after birth, the baby begins to experience day and night (light and dark), and the formation of the central CR clock in the SCN progresses. After the neonatal period, the CR biological clock begins to develop rapidly. Eventually, the sleep/wake rhythm gradually comes under the control of the CR throughout daily life, and is incorporated into the 24-hour CR by 3-4 months of age. Early infancy is considered to be a critical period when all the organ, tissue and cell clocks that were formed during fetal development and that operate autonomously are unified in the SCN and begin to function as a coordinated clock [

6].

4. Factors Involved in the Formation of the Biological Clock

4.1. Fetal Period

4.1.1. Living Environment of the Mother During Pregnancy

As the formation of the biological clock begins during fetal development, it is assumed that it is naturally influenced by the mother [

37]. In fact, the fetus—which is considered to be part of the mother's body—is thought to live a life guided by the daily rhythms of the mother's two main clocks, the central clock and the peripheral clock, such as bedtime, wake-up time, and mealtime [

6]. In other words, the fetus is considered to be in a similar state to the mother's peripheral organs such as the heart, liver, and limbs, and it is necessary to consider that the mother's daily life is directly connected to the fetus's daily life [

29,

37,

38,

39,

40]. In this way, the fetus and the mother are in a close cooperative relationship in the womb, and the fetus is protected. After birth, the fetus leaves the mother's protection and transitions to life on Earth, so the uterus is provided with an appropriate environment for this transition. For example, the fetus's internal rhythm is created by various signals such as the mother's body temperature, food, and melatonin (transferred from the mother to the fetus) [

40,

41,

42]. In fact, problems such as nutritional problems during pregnancy, poor lifestyle habits, and exposure to infectious diseases and pollutants (including tobacco and alcohol) may affect the fetus. These influences from the mother are closely related to the child's development, and pregnant mothers should avoid staying up late as much as possible, rest during the day, maintain a regular sleep/wake rhythm, and eat regular meals [

43]. However, the fetal clock is not completely synchronized with the mother's clock, but is adjusted with a difference of several hours [

44]. The meaning of this is not yet fully understood, but it is interpreted as giving us the flexibility to live on Earth after birth.

4.2. Infancy Is an Important Period for CR Formation

As mentioned above, the fetus exists as one of the mother's organs, and the fetus's daily rhythm is thought to be controlled by the central clock in the mother's SCN. However, the formation of CR progresses during fetal development, and CRs begin to form in each organ of the fetus between the 20th and 22nd weeks of pregnancy [

30]. Interestingly, the clocks of each organ formed during fetal development have their own independent rhythms and are not coordinated [

29,

31,

34,

45]. At the end of pregnancy, the mother's CR and the fetal heart rate are synchronized; however, this synchronization ends at birth and the fetus switches to a daily life based on the UR [

46]. After birth, as the fetus experiences day and night (light and dark), the formation of the central clock in the SCN begins, and the CR is almost complete by early infancy (1-2 years of age) [

6]. Therefore, the CR in the newborn is still immature. During the newborn period, the CR of sleep and wakefulness has not yet been fully formed, such that the daily life of the newborn follows a (UR) sleep/wake rhythm with a cycle of approximately 3-4 hours [

26,

35]. This rhythm is important for newborns and, as mentioned above, the formation of this rhythm becomes more stable and the formation of the next CR becomes smoother [

26]. It is gradually becoming clear that the formation of the circadian clock is closely related to brain development, and it is known that many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have poor formation of URs in the neonatal period [

43].

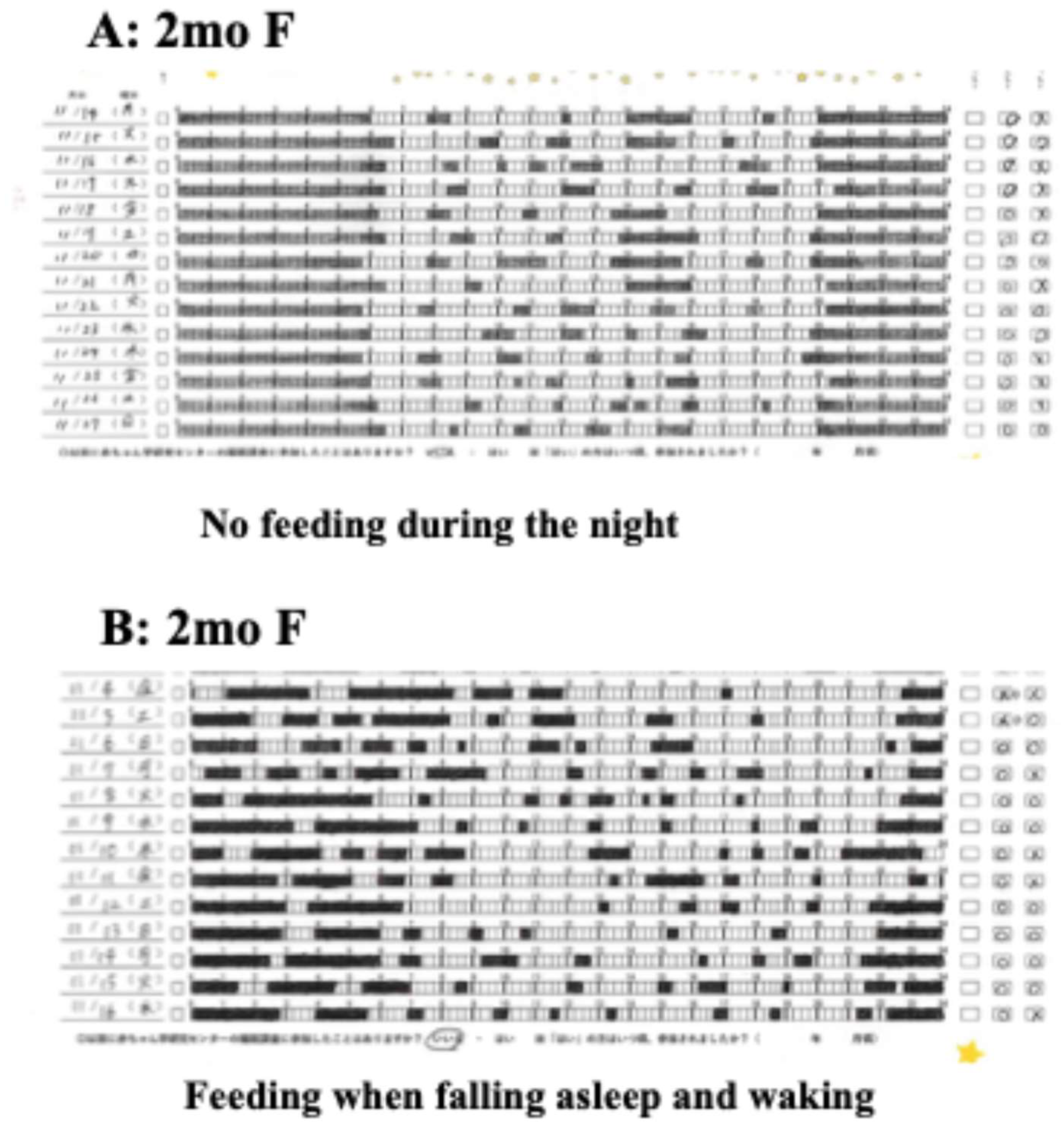

In the newborn period, waking every 3-4 hours throughout the night indicates a proper UR [

6,

26,

36]. However, parents need to feed their babies according to this rhythm, which fragments their sleep and makes daily life difficult. However, after two months of age, the baby is more likely to sleep for more than five or six hours, possibly even continuously through the night, which may make parenting easier overall (

Figure 2-A). On the other hand, frequent awakenings in babies after 2 months of age, especially after 3-4 months of age, indicate an interruption or persistence of UR and that the transition to the next important step, CR formation, has not progressed properly. Infants who inherit various clocks in their organs during fetal development acquire a daily schedule of sleep and wake times while experiencing daily rhythms such as night and day and darkness and light, and solidify the integration of their entire body's biological clocks through this daily rhythm. It is generally believed that a baby's CR begins to become fixed between 6 months and 12 or 18 months of age [

5,

7,

47,

48] and, although there may be some margin of error, it is believed that the circadian biological clock is almost completely established in the suprachiasmatic nucleus by the age of 1.5~ 2, indicating that this is a critical period.

As mentioned above, after the neonatal period, biological CRs begin to develop rapidly. First, the secretion rhythm of the pineal hormone (melatonin), which is said to be the conductor of biological rhythms, begins at the end of the neonatal period [

48]. Subsequently, the sleep/wake rhythm and the thermoregulation rhythm also begin to appear as the CR at 2-3 months of age [

34,

49]. Since the formation of CR in babies is surprisingly early, it is recommended that parents keep this in mind when raising their children. In light of these medical facts, pediatricians in France instruct mothers to stop breastfeeding babies during night-time sleep after the neonatal period [

50]. This instruction is extremely interesting, as it suggests that the formation of a biological clock in infants is an important issue that precedes everything else. Additionally, American pediatricians recommend gradually increasing the interval between night-time feedings after the newborn period and ceasing night-time feedings at 3-4 months of age [

51].

4.3. Full-Scale Biological Clock Formation from Early Infancy

During the first year of life, the sleep/wake rhythm continues to become established, coinciding with the increase in melatonin secretion at sunset [

52]. In particular, the onset of night-time sleep is linked to sunset for the first few months of life, and then to the bedtime of the family. This suggests that the circadian rhythm is initially synchronized with light, but then synchronized with social and environmental factors.

It is difficult to grasp the details of children's daily rhythms with casual observation, so we recommend recording sleep and wakefulness for two weeks several times a year using a sleep chart (

Figure 2-A, B). After two months of age, as the circadian rhythm of hormones and thermoregulation in children begins to appear, sleep is concentrated at night, daytime wakefulness becomes longer, and night-time sleep begins to last longer. It has been reported that night-time sleep time is about 5-6 hours at 2 months of age [

53], about 8-9 hours at 4 months of age [

54], and about 8-12 hours at 6-7 months of age [

51]. Furthermore, it has been reported that children who can maintain sufficient sleep have a higher ability to self-soothe [

53,

54,

55] and cry less at night. In order to foster the habit of self-soothing, parents need to refrain from immediately reaching out to help their baby when it cries, and instead take the time to watch over it [

56]. According to these reports, infants who can sleep through the night (8-12 hours) between the ages of 4 and 6 months no longer need night-time feedings [

51].

In addition, the peripheral clock works closely with the central clock to form a well-regulated CR biological clock, so it is recommended to eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner at approximately the same time for proper CR formation [

57]. CR formation is almost complete by the late lactation period to early infancy (around 1.5 to 2 years of age); the clocks of all organs in the body are integrated and the individual's CR is complete. At this point, the biological clock is not completely fixed, and it is thought to remain flexible until the preschool age. Notably, the ability to correct the biological clock decreases with age, so if the biological clock is not formed properly, early correction is necessary. When the CR begins to be established in the SCN, long night-time sleep and short daytime sleep begin to repeat in a 24-hour cycle, and finally, the sleep/wake rhythm and the circadian rhythm overlap and appear to be the same.

In this way, the CR biological clock, which is centered on the sleep/wake rhythm, is completed relatively early in children's SCN, so setting the time for children to fall asleep should be considered from the neonatal period. Considering that the clock mechanism is almost fixed by early infancy, it is easy to assume that the formation of a lifestyle rhythm that adapts to the long modern school/social life is an unavoidable and important matter. Specifically, with a view to school/social life, it is recommended to establish the habit of waking up on one's own between 6-7 am and falling asleep between 8-9 pm to support this [

51,

58]. This lifestyle rhythm is the background and basis for the formation of the biological clock, so it is recommended to form a lifestyle rhythm that follows this basis.

4.4. The Biological Clock Adapts to the School/Social Life Schedule

Modern people live their school/social life, which requires a relatively strict and regular 24-hour schedule. Globally, social life generally follows a typical morning rhythm, with activities starting around 8:00 am. However, the recent spread of late-night lifestyle habits among modern people, which has become globalized, has often caused a delayed life rhythm, including for infants and young children [

58], creating a breeding ground for the so-called "social jet lag" [

59,

60,

61]. It is obvious that such a shift in life schedule makes it difficult for humans to maintain proper activity and reduces their vitality. In addition to the physical and mental development of infants and young children, the following conditions are thought to be necessary for the proper formation of the circadian rhythm biological clock, which is involved in maintaining mental and physical health throughout one's life [

58,

62].

(1) Wake-up time: In the school/social life of the near future, students must be at school by 8:00 am. It is reported that children need about an hour from the time they wake up in the morning until they can start doing other things, which means they need to be up by 6 or 7 in the morning. If it takes a long time to get to school, they may have to wake up even earlier.

(2) Night-time Basic Sleep Duration (NBSD) [

58]: It is believed that there is a basic amount of night-time sleep that children need from infancy through to toddlerhood. This NBSD varies slightly depending on race and region of residence, with Caucasian children reported to need 10-11 hours (11 hours is common) and Japanese children just under 10 hours. It is more logical to determine whether a child is getting enough NBSD in order to determine whether they are suffering from a lack of sleep, which can be detrimental to them, and problems have been pointed out using the total amount of sleep per day as a criterion.

(3) Time of sleep onset: Based on the above conditions, the recommended time for sleep onset is between 7:00 and 9:00 pm, which is when children's NBSD can be ensured before waking up in the morning.

(4) Duration of night-time sleep: A condition for good quality sleep is that night-time sleep should be continuous, and frequent awakenings or awakenings lasting more than 30-60 minutes during night-time sleep are known to be undesirable.

It is considered appropriate for a circadian biological clock that meets the above conditions to be formed by the time a child is around 1.5 to 2 years old.

4.5. Formation of the CR Biological Clock and Naps

According to a report, infants take multiple naps in the morning, afternoon, and evening until around 7 months of age, and then one nap each in the morning and afternoon from 7 to 8 months onwards, and then one nap between 12 and 15:00 at 14 to 18 months of age [

63]. In other report, a pattern of two naps per day is established by 9 to 12 months of age, and one nap in the afternoon is established by 15 to 24 months of age [

64].

It has been reported that children who do not take naps appear as early as 2 years of age (2.5%), nearly 90% of children stop taking naps by the age of 5 years [

64,

65] and, finally, most children do not take a nap by the age of 7 years [

65].

Naps after the age of 2 years are due to a delayed sleep onset, resulting in a poorer quality of sleep and a shorter sleep duration, and if a sleep disorder is suspected in a preschool child, the nap situation should be considered [

66]. In recent years, some children have been reported to not take naps after the age of 3 years; however, the reason for this has not yet been clarified. However, as will be explained in detail later, there are data that suggest that naps are not necessary for maintaining health as long as the NBSD is about 10-11 hours. Naps themselves are common throughout the world, and there are a few ethnic groups that do not take naps, so naps themselves are not considered a problem. Naps are thought to be caused by the semi-daily rhythm of sleepiness from 12:00 to 15:00, and are considered to be a short break to refresh the brain tired from morning activities. It is said that the most gasoline is consumed when starting a car engine; similarly, the brain may also consume the most energy at the start of the day. The benefits of naps are generally known, but the reasons why they are taken remain unclear. Naps are thought to be a semi-circular sleep rhythm that is fundamentally different from the sleep that modern people take to make up for a lack of sleep, as they feel sleepy all day due to insufficient sleep at night.

* Genes that control the biological clock

The clock is controlled by clock genes that are found in almost all tissue cells in the human body, including peripheral lymphocytes. The well-known major clock genes include Period (per), Clock (Clk), and cryptochrome (cry). Incidentally, about 20 clock genes have been reported to date, but about 350 loci related to so-called chronotypes, such as morning type (skylark type), have been found. For example, the time it takes to fall asleep differs by about 25 minutes between people with a very high number of loci that determine morningness and people with a very low number of these loci [

67]. Regarding genes involved in the biological clock, I will refrain from going into detail here, as the reader can refer to the several relevant studies on this topic.

5. Factors Involved in the Formation of CRs

5.1. Fetal Period

5.1.1. Mother's Own Life Rhythms

The stability of the CR during pregnancy is important for both the mother and offspring. For the fetus to successfully transition to extrauterine life, the mother must precisely provide a myriad of time-integrated humoral/biophysical signals. The peripheral clock is entrained by maternal cues such as melatonin signaling via the placenta, resulting in the existence of a circadian cycle in the fetus [

68]. A suboptimal environment during pregnancy increases the risk of offspring developing various chronic diseases later in life [

68,

69,

70]. The intrauterine environment is rhythmic in nature, and the fetus is subject to changes in temperature, substrate, and the circadian rhythms of various maternal hormones [

32]. Meanwhile, the fetus is developing an endogenous circadian system to prepare it for life in an external environment where light, food availability, and other environmental factors change predictably and repeatedly every 24 hours [

29,

31,

34,

44]. In humans, there are many situations that can disrupt the CR, including shift work, international travel, insomnia, and CR disorders (e.g., advanced/delayed sleep phase disorders), and there is a growing consensus that this disruption of the CR can have detrimental consequences for an individual's health and well-being [

32,

69,

70].

Epidemiological studies have reported that pregnant women engaged in chronic shift work have an increased risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and miscarriage [

71,

72,

73,

74]. Abnormalities in sleep, feeding, and work schedules may disrupt maternal rhythms, such as melatonin fluctuations, resulting in the desynchronization of maternal SCN and peripheral oscillators, leading to the deleterious effects of shift work on the fetus. Pregnant rats exposed to simulated shift work (the complete reversal of the light–dark cycle every 3–4 days for several weeks) showed significantly reduced weight gain during early gestation, reduced fat pad and liver weights, and reduced amplitude of rhythms pertaining to corticosterone, glucose, insulin, and leptin levels [

75]. Exposure of pregnant non-human primates to constant light suppresses the emergence of melatonin and body temperature rhythms in postnatal offspring [

75,

76,

77,

78,

79]. This suggests that maternal rhythms are important for the early fetal brain development of CRs [

80]. Changes in the rhythm of circadian gene expression are also associated with spatial memory impairments in these offspring [

80,

81], and these memory impairments can be prevented by the regular supplementation of melatonin to the mother [

80]. These findings suggest that the daily rhythm of the mother during pregnancy may affect the formation of CRs in the fetus. Such studies are particularly important because the proportion of shift work and long working hours has increased in the past decade, as well as long the exposure to light at night and the use of electronic devices due to work and social demands [

82]. These findings can be considered as an indication of the extremely high relevance of the clinical expression throughout life as indicated by the DOHaD theory [

83,

84] (described later) and the target of the formation of circadian rhythms in children from fetal to infant stages. This is because, although there are still many unknowns, we are beginning to better understand how circadian rhythms are closely related to neurotransmission, metabolism, immunity, and other processes. Thus, disruptions to sleep and CRs across the lifespan are strongly linked to the pathophysiology of certain psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

5.1.2. Environmental Contaminants

Exposure to adverse conditions in utero can lead to permanent changes in the structure and function of key physiological systems during fetal development, increasing the risk of disease and premature aging in postnatal life [

85]. Although no specific issues have been reported, one report demonstrated that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), particulate matter, and components of environmental tobacco smoke are significantly transferred from the mother to fetus through the placenta, that the environmental exposure to PAHs from air pollution increases the levels of PAH-DNA adducts in maternal and neonatal leukocytes, and that fetuses are more sensitive to genetic damage than mothers [

86]. What role do pesticides, heavy metals, dioxin derivatives, and polychlorinated diphenyl compounds play as macroenvironmental contaminants in mutagenesis and teratogenesis? To answer this question, substances that are within the control of the exposed person, such as alcohol, drugs, and tobacco smoke, and their microenvironmental effects have been investigated [

87]. The mechanism of action of these air pollutants is thought to be that pollutants such as heavy metals that reach the placenta may change DNA methylation patterns, leading to changes in placental function and fetal reprogramming. Indeed, reports of changes in placental DNA methylation associated with prenatal exposure to air pollution (including heavy metals) have shown that they are associated with changes in total and promoter DNA methylation of genes involved in biological processes such as energy metabolism, circadian rhythm, DNA repair, inflammation, cell differentiation, and organ development [

88]. These issues are also of interest in relation to the DOHaD theory [

83,

84,

85,

89].

5.2. Newborns and Infants

5.2.1. Premature Infants

Constant lighting conditions are common in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) around the world, allowing care and nursing staff to respond quickly to potential emergencies and frequently monitor neonatal health [

90]. However, when premature infants (≥32 weeks of gestation) are raised on a regular light–dark schedule in the NICU, they gain weight faster than infants raised under constant bright or dim light, effectively shortening their length of hospital stay [

91,

92]. Compared with infants raised under constant dim light, these infants cry less and are more active during the day [

93]. A regular light–dark schedule accelerates the maturation of rest-activity, sleep/wake, and melatonin rhythms in premature infants [

93,

94,

95].

5.2.2. Night-Time Feeding

During night-time sleep, infants are in a period of transition from a short ultradian cycle to a continuous circadian cycle, and it is believed that they are physiologically more likely to wake up at certain times during the night. Feeding (particularly breastfeeding) is often used as a method to encourage infants to fall asleep again after waking up. Breastfeeding is considered the optimal feeding method for newborns and their mothers.

In particular, the importance of breastfeeding during the neonatal period has been emphasized [

96,

97]. In addition, breast milk changes during lactation are perfectly adapted to the nutritional and immune needs of the infant, so it is recommended to continue breastfeeding for at least six months of age. However, the composition of breast milk changes throughout the day, and melatonin concentrations are higher in night-time breast milk and are thought to be involved in the formation of CR in children [

98,

99]. Therefore, it is not recommended to give breast milk expressed during the day at night, and feeding habits adapted to the time are required. Circadian variations in some physiologically active compounds are thought to transmit chronobiological information from the mother to child and help the development of the biological clock [

99,

100,

101]. On the other hand, it has been reported that breastfed infants tend to wake up more frequently at night [

102,

103], their mothers tend to get less sleep [

104,

105], and exclusive breastfeeding after birth can lead to vitamin D deficiency [

106,

107,

108]. Therefore, the careful consideration of the aforementioned facts is needed when relying solely on breastfeeding.

Frequent awakenings and long awakenings during night-time sleep do not lead to a balanced mental and physical development of children, and the habit of breastfeeding every time a child wakes up at night may actually lead to the disruption of night-time sleep continuity and disrupt the rhythm of the biological clock (

Figure 2-B). In other words, the frequent care of a crying or awake child during the night, especially care with food (breast milk, formula, water, etc.), has been reported to stimulate the peripheral biological clock and cause awakening reactions and sleep disorders, and has attracted attention [

109,

110,

111]. In our study [

112], we found that if the habit of breastfeeding every time an infant wakes up continues throughout infancy, it is significantly more likely to cause sleep continuity disorders and develop ASD in the future.

In infants aged 2 to 3 months, body movements may occur during REM sleep, which may be mistaken for waking up during the night. Since these body movements are often not a true awakening, it is thought that caregivers should not respond immediately, but should help the child learn self-soothing to help them acquire the ability to fall asleep again naturally [

51,

113,

114]. In fact, it is known that, at 4 months of age, the night-time sleep time extends to 8-9 hours, and breastfeeding during night-time sleep is no longer necessary for physical or nutritional reasons [

51,

54,

115]. This early cessation of night-time breastfeeding has been reported to prevent future night-time crying and sleep maintenance disorders, to properly form the CR biological clock, to promote healthy physical and mental development [

51], and to help reduce parental fatigue [

51,

112]. Notably, this proposal does not refer to the cessation of breastfeeding itself, but rather to the cessation of breastfeeding during night-time sleep. Thus, there is no problem with continuing breastfeeding during the day.

It is recommended that night-time breastfeeding be stopped while closely observing the development of sleep continuity for each child. In general, it is recommended that night-time breastfeeding be stopped by 6 months of age, as circadian rhythm formation is steadily progressing by that time. It is often seen that breastfeeding continues until after 6 months of age, and stopping breastfeeding is recommended as a countermeasure for night-time crying that becomes severe. However, it is thought that the early cessation of night-time breastfeeding does not cause night-time crying in the first place. Frequent and long awakenings during night-time sleep can distort a child's brain function, so the more times a parent touches the child during night-time sleep, the more the child's sleep is disturbed, leading to sleep disorders [

110,

112]. This is because night-time feedings start the peripheral clock, which promotes wakefulness, and thus interferes with the formation of the central clock function that indicates that night-time is a time for sleep and rest. It is believed that this can lead to frequent night-time awakenings and sleep continuity disorders (fragmentation).

5.3. Early Childhood

Many toddlers (2–3 years) and preschool children (4–6 years) show earlier sleep/wake patterns and a stronger morning preference than adults, even when accounting for large intra- and inter-individual variability in sleep onset, wake-onset, and wake-up times [

116,

117]. However, with age, sleep onset times begin to become later and more children begin to have difficulty waking in the morning. This indicates that social and environmental factors, such as school and parent-imposed schedules, have a significant impact on the survey-based measurements of chronotype. Reportedly, the mean differences between socially scheduled and free days are significant for all sleep/wake parameters. Children on free days went to bed and woke up later, slept about 20 minutes longer, and had shorter sleep latency and sleep inertia estimates than on scheduled days [

117]. It has been reported that, while there is no change in the sleep onset time, the wake-up time on weekends is about 30 minutes later than on weekdays in nursery school children [

58]. The social environment and parental schedule demands may interact with endogenous circadian and sleep rhythms, creating a state of mismatch between social schedules, endogenous circadian physiology, and sleep homeostasis. This indicates that social and environmental factors such as school and parent-imposed schedules have a significant impact on the survey-based measurements of chronotype [

58,

116].

6. Disruption of Biological Clocks

The circadian rhythm in mammals is controlled by endogenous biological oscillators, including a master clock located in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The duration of this oscillation is approximately 24 hours, so to stay synchronized with the environment, the circadian rhythm must be entrained daily by Zeitgeber ("time donor") signals such as the light–dark cycle [

10].

6.1. Jet Lag

The biological clock was originally thought to have a stable rhythm that was unlikely to go out of sync. It is said that the first time humans typically experience a disruption of the biological clock is when they experience jet lag while traveling abroad on a jet plane. It was not so long ago that humans were able to experience the workings of the biological clock. The biological clock was thought to be a relatively stable property of the human body that did not go out of sync easily but, with the invention of airplanes and the evolution of jet planes, humans were able to travel to distant parts of the earth within a short time.

In the days of sea voyages, when we slowly synchronized our biological clocks little by little to reach the living environment of our destination on the other side of the Earth, where day and night are reversed, we did not feel this biological clock at all. Jet lag occurs when the biological rhythm, which occurs after crossing a time zone so rapidly that the circadian rhythm system cannot keep up, becomes out of sync with the day/night cycle of the destination [

118,

119,

120,

121]. It is known that jet lag symptoms are milder when traveling westward. This is explained by the fact that the body clock is more adaptable to travel westward (where the daily cycle is longer), but less adaptable to eastward travel (where the daily cycle is shorter) [

118]. If one is thrown into a living environment that suddenly reverses the rhythm of one's biological clock in a short period of time, the biological clock cannot immediately synchronize and the rhythm of one's life with the outside world is not in sync, leading to a state in which the coordination between cells and organs is disrupted and the life support mechanisms cannot function (jet lag). In other words, the biological clock is a mechanism that supports life activities in accordance with the "night and day" of the place on Earth where humans live constantly. Furthermore, jet lag and shift work disorders have been found to induce circadian rhythm sleep/wake disruptions that arise from behavioral changes in sleep/wake schedules in relation to the external environment [

119,

121].

Jet lag and shift work sleep disorders are the results of dyssynchrony between the internal clock and the external light–dark cycle, brought on by rapid travel across time zones or by working a non-standard schedule. Symptoms can be minimized through optimizing the sleep environment, strategic avoidance of exposure to light, and drug and behavioral therapies [

122].

6.2. Chronodisruption

In this section, I discuss the rapid increase in the number of modern people who suffer from the jet lag state, which is similar to that experienced when traveling abroad but is more persistent, chronic, and malignant, despite living in the country or place where they were born and raised. The background to this may be, for example, the family's lifestyle rhythm; however, it is also common that a child may have been living a ‘night owl’ lifestyle since birth, or may have a chronic lack of sleep and cannot adapt to the school/social rhythm of life due to their lifestyle and environment, such as homework loads, caffeine intake, early school start times, cram school and other academic and sports activities, and increased TV and other screen time [

123]. Recent studies have shown that long-term circadian rhythm disruption is associated with many pathological conditions, including premature death, obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes, mental illness, anxiety, depression, and cancer progression, while short-term disruption is associated with poor health, fatigue, and decreased concentration [

124]. The existence of this condition has been recognized for some time, and has been reported under various names; however, it is safe to assume that all of them refer to the same condition. The different names of this condition are as follows: 1) “biological (circadian) rhythm disturbance” [

125,

126], 2) “chronic fatigue syndrome” [

127,

128], 3) “chronodisruption” [

12,

129,

130], 4) “social jetlag” [

59], 5) “circadian misalignment” [

131], 6) “circadian disruption” [

132], and 7) “circadian syndrome” [

133]. This condition, known as chronodisruption, is worth highlighting as it is closely related to our body clock.

As "chronodisruption" is thought to succinctly describe the pathology of this condition, this term is also used in this report. There are accumulating reports that this pathology, which can occur in any age group, is deeply related to the onset and worsening of other diseases, such as developmental disorders, school refusal, social withdrawal, glucose metabolism disorders (diabetes), depression, kidney disease, digestive diseases, cardiovascular diseases, dementia (Alzheimer's disease), and cancer. Qian J et al. [

11] provided a clear illustration of the pathology of time disruption in tissues throughout the body, which is a recommended reference. The importance of time disruption varies depending on the author; however, in severe cases, the author of this study personally believes that it would be more appropriate to call it "systemic chronodisruption," considering that this pathology extends to the entire body.

6.3. Chronodisruption and DOHaD

Recently, some studies have been published on the relationship between the mother's living environment and the formation of the fetal circadian rhythm, and how this may lead to various diseases in the future [

69,

70,

134]. These studies have reviewed recent information on the mother's shift work, jet travel across time zones, irregular meals, and exposure to light at night during pregnancy that cause deviations and disruptions to the circadian clock, affecting fetal oxidative stress, RAS (renin–angiotensin system), epigenetic regulation, and glucocorticoid programming, leading to various physical and mental health problems from infancy to adulthood (obesity, fatty liver, insulin resistance, kidney disease, hypertension, neurobehavioral disorders, reproductive dysfunction, cancer, and dementia). In other words, the research results indicate that problems in the formation of the circadian clock during fetal development may cause various health problems in adulthood, as stated in the DOHaD hypothesis [

69,

70,

134]. In addition to these health hazards, the authors also report that developmental disorders are closely related to childhood problems such as "school refusal and social withdrawal due to circadian rhythm sleep disorders" [

112,

128]. In fact, many children with developmental disorders and school refusal after elementary school generally have a history of sleep disorders from the neonatal period. In other words, this supports the hypothesis that the misalignment or disruption of the body clock is the basis of the DOHaD hypothesis, and is likely to be an important research topic in the future.

Conclusion

The CR center, which begins to form in the fetal stage and is nearly completely formed by early childhood, plays an important role in controlling life-sustaining functions such as sleep/wake, thermoregulation, and hormone secretion rhythms. Furthermore, it is known that the CR is strongly related to mental and physical development and the maintenance of health throughout life. Therefore, in order to form an appropriate CR biological clock, it is recommended to consider the possibility that the mother’s living environment during fetal development may affect the formation of CR after birth as a predisposing factor, and to pay attention to the following points: 1) It is recommended that the mother's daily rhythm during pregnancy, such as sleep/wake and meal times, be regular, as this is strongly related to the formation of the circadian rhythm of the fetus. In addition to the qualities developed during the fetal period, the way of spending daily life after birth also greatly affects the formation of CR. 2) Especially from the neonatal period to infancy, it is recommended to base the life rhythm on one that can adapt to the future rhythms of school and social life. 3) It is recommended to live a life in which there is no discrepancy between one's own life rhythm and the schedule required by the living environment, or to minimize such a discrepancy throughout one's life. As a concrete indicator of a child's life, it is important to avoid the habit of staying up late from the moment of birth. As we grow up, environments that encourage staying up late—such as earlier start times for nursery schools, kindergartens, and schools, more homework, caffeine intake, studying at cram schools, sports, and increased screen time due to watching TV—increase the gap between one's own life rhythm and social life, leading to future chronodisruption. Therefore, correcting one's life rhythm as soon as one notices this discrepancy is an effective way to maintain an appropriate biological clock and prevent the occurrence of chronodisruption, and it is advisable for those involved in childcare to be fully aware of the need for this correction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript to disclose.

Abbreviations

| CR |

circadian rhythm |

| UR |

ultradian rhythm |

| SCN |

suprachiasmatic nucleus |

| NBSD |

Night-time Basic Sleep Duration |

| DOHaD |

Developmental Origin Health and Disease |

References

- Reppert, S.M.; Weaver, D.R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 2002, 418, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornhauser, J.M.; Mayo, K.E.; Takahashi, J.S. Light, immediate-early genes. Behav. Genet. 1996, 26, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serón-Ferré, M.; Torres-Farfán, C.; Forcelledo, M.L.; Valenzuela, G.J. The development of circadian rhythms in the fetus and neonate. Semin. Perinatol. 2001, 25, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkees, S.A.; Hao, H. Developing circadian rhythmicity. Semin. Perinatol. 2000, 24, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, S. The Science of Sleep (in Japanese); Asakura Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2006; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Serón-Ferré, M.; Mendez, N.; Abarzua-Catalan, L.; Vilches, N.; Valenzuela, F.J.; Reynolds, H.E.; Llanos, A.J.; Rojas, A.; Valenzuela, G.J.; Torres-Farfan, C. Circadian rhythms in the fetus. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 349, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchette, E.; Dionne, G.; Forget-Dubois, N.; Petit, D.; Pérusse, D.; Falissard, B.; Tremblay, R.E.; Boivin, M.; Montplaisir, J.Y. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Daytime and Nighttime Sleep Duration in Early Childhood. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1874–e1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, C.A.; Duffy, J.F.; Shanahan, T.L.; Brown, E.N.; Mitchell, J.F.; Rimmer, D.W.; Ronda, J.M.; Silva, E.J.; Allan, J.S.; Emens, J.S.; et al. Stability, Precision, and Near-24-Hour Period of the Human Circadian Pacemaker. Science 1999, 284, 2177–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golombek, D.A.; Rosenstein, R.E. Physiology of Circadian Entrainment. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1063–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Merrow, M. The Circadian Clock and Human Health. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R432–R443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Scheer, F.A. Circadian System and Glucose Metabolism: Implications for Physiology and Disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 27, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erren, T.C.; Reiter, R.J.; Piekarski, C. Light, timing of biological rhythms, and chronodisruption in man. Sci. Nat. 2003, 90, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, A.B.; Knutson, K.L.; Zee, P.C. Circadian disruption and human health. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, S.M.; Malkani, R.G.; Zee, P.C. Circadian disruption and human health: A bidirectional relationship. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 51, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibner, C.; Schibler, U.; Albrecht, U. The Mammalian Circadian Timing System: Organization and Coordination of Central and Peripheral Clocks. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 517–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.S. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 18, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Alcocer, V.; Rohr, K.E.; Joye, D.A.M.; Evans, J.A. Circuit development in the master clock network of mammals. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 51, 82–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schibler, U.; Gotic, I.; Saini, C.; Gos, P.; Curie, T.; Emmenegger, Y.; Sinturel, F.; Gosselin, P.; Gerber, A.; Fleury-Olela, F.; et al. Clock-Talk: Interactions between Central and Peripheral Circadian Oscillators in Mammals. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2015, 80, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J. Circadian Clocks: Setting Time By Food. J. Neuroendocr. 2006, 19, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takimoto, M.; Hamada, A.; Tomoda, A.; Ohdo, S.; Ohmura, T.; Sakato, H.; Kawatani, J.; Jodoi, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Terazono, H.; et al. Daily expression of clock genes in whole blood cells in healthy subjects and a patient with circadian rhythm sleep disorder. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 289, R1273–R1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuninkova, L.; Brown, S.A. Peripheral circadian oscillators: interesting. mechanisms and. powerful tools. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1129, 358–370. [Google Scholar]

- Piggins, H.D.; Guilding, C. The neural circadian system of mammals. Essays Biochem. 2011, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtold, D.A.; Loudon, A.S. Hypothalamic clocks and rhythms in feeding behaviour. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challet, E. The circadian regulation of food intake. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, R.G.; Timmons, G.A.; Cervantes-Silva, M.P.; Kennedy, O.D.; Curtis, A.M. Immunometabolism around the Clock. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, C.; Menna-Barretoet, L. Development of sleep/wake, activity and temperature rhythms in newborns maintained in a neonatal intensive care unit and the impact of feeding schedules. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2016, 44, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakayama, K.; Ogawa, T.; Goto, K.; Sonoda, H. Development of ultradian rhythm of EEG activities in premature babies. Early Hum. Dev. 1993, 32, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K.; Morokuma, S.; Nakano, H. Fetal behavior: ontogenesis and transition to neonate. In Donald School Textbook, seconded; Kurjak, A., et al., Eds.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, 2008; pp. 641–655. [Google Scholar]

- Seron-Ferre, M.; Valenzuela, G.J.; Torres-Farfan, C. Circadian clocks during embryonic and fetal development. Birth Defects Res. Part C: Embryo Today: Rev. 2007, 81, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.; Visser, G.; Mulder, E.; Prechtl, H. Diurnal and other variations in fetal movement and heart rate patterns at 20–22 weeks. Early Hum. Dev. 1987, 15, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkees, S.A. DEVELOPING CIRCADIAN RHYTHMICITY: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 1997, 44, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varcoe, T.J.; Gatford, K.L.; Kennaway, D.J. Maternal circadian rhythms and the programming of adult health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 314, R231–R241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Adams Hillard, P.J.; Katz, E.S.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, M.; Maas, Y.G.; Ariagno, R.L. Development of fetal and neonatal sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep Med. Rev. 2003, 7, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meierkoll, A.; Hall, U.; Hellwig, U.; Kott, G.; Meierkoll, V. A biological oscillator system and the development of sleep-waking behavior during early infancy. Chronobiologia 1978, 5, 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, R.; Lim, J.; Famina, S.; Caron, A.M.; Dowse, H.B. Sleep-wake behavior in the rat: ultradian rhythms in a light-dark cycle and continuous bright light. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2012, 27(6), 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppert, S.M.; Schwartz, W.J. Maternal coordination of the fetal biological clock in utero. Science. 1983, 22, 969–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellon, S.M.; Longo, L.D. Effect of Maternal Pinealectomy and Reverse Photoperiod on the Circadian Melatonin Rhythm in the Sheep and Fetus during the Last Trimester of Pregnancy1. Biol. Reprod. 1988, 39, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheli, K.; Komninos, I.; Bagkeris, E.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Koutis, A.; Kogevinas, M.; Chatzi, L. Sleep Patterns in Late Pregnancy and Risk of Preterm Birth and Fetal Growth Restriction. Epidemiology 2011, 22, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.X.; Korkmaz, A.; Rosales-Corral, S. A Melatonin and stable circadian rhythms optimize maternal, placental and fetal physiology. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014, 20, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.R.; Reppert, S.M. Periodic feeding of SCN-lesioned pregnant rats entrains the fetal biological clock. Dev. Brain Res. 1989, 46, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serón-Ferré, M.; Torres, C.; Parraguez, V.H.; Vergara, M.; Valladares, L.; Forcelledo, M.L.; Constandil, L.; Valenzuela, G.J. Perinatal neuroendocrine regulation. Development of the circadian time-keeping system. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002, 186, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miike, T.; Toyoura, M.; Tonooka, S.; Konishi, Y.; Oniki, K.; Saruwatari, J.; Tajima, S.; Kinoshita, J.; Nakai, A.; Kikuchi, K. Neonatal irritable sleep-wake rhythm as a predictor of autism spectrum disorders. Neurobiol. Sleep Circadian Rhythm. 2020, 9, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, M.; Iwata, S.; Okamura, H.; Saikusa, M.; Hara, N.; Urata, C.; Araki, Y.; Iwata, O. Paradoxical diurnal cortisol changes in neonates suggesting preservation of foetal adrenal rhythms. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreck, K.A.; Mulick, J.A.; Smith, A.F. Sleep problems as possible predictors of intensified symptoms of autism. Res. Dev. Disabil 2004, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, M.; Jost, K.; Gensmer, A.; Pramana, I.; Delgado-Eckert, E.; Frey, U.; Schulzke, S.M.; Datta, A.N. Immediate effects of phototherapy on sleep in very preterm neonates: an observational study. J. Sleep Res. 2016, 25, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, O.; Baumgartner, E.; Sette, S.; Ancona, M.; Caso, G.; Di Cosimo, M.E.; Mannini, A.; Ometto, M.; Pasquini, A.; Ulliana, A.; et al. Longitudinal Study of Sleep Behavior in Normal Infants during the First Year of Life. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardura, J.; Gutierrez, R.; Andres, J.; Agapito, T. Emergence and Evolution of the Circadian Rhythm of Melatonin in Children. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2003, 59, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, S.; Nishihara, K.; Horiuchi, S.; Eto, H. The influence of feeding method on a mother's circadian rhythm and on the development of her infant's circadian rest-activity rhythm. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 145, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dracckerman, P. French Children Don't Cry at Night: The Secret of Parenting from Paris, (in Japanese) Tokyo, Shueisha, Japan, 2014.

- Paul, I.M.; Savage, J.S.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Marini, M.E.; Mindell, J.A.; Birch, L.L. INSIGHT Responsive Parenting Intervention and Infant Sleep. Pediatrics 2016, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkees, S.A. Developing circadian rhythmicity in infants. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev 2003, 1, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, T.; Birch, L.L. Help me make it through the night: behavioral entrainment of breast-fed infants' sleep patterns. . 1993, 91, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.M.; France, K.G.; Blampied, N.M. The consolidation of infants' nocturnal sleep across the first year of life. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011, 15, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, C.; Gross-Hemmi, M.H.; Meyer, A.H.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Schneider, S. Temporal Patterns of Infant Regulatory Behaviors in Relation to Maternal Mood and Soothing Strategies. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2019, 50, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, A.; Juda-Hanael, M.; Livne-Karp, E.; Kahn, M.; Tikotzky, L.; Anders, T.F.; Calkins, S.; Sivan, Y. Low parental tolerance for infant crying: an underlying factor in infant sleep problems? J. Sleep Res. 2016, 25, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Circadian clock genes and the transcriptional architecture of the clock mechanism. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2019, 63, R93–R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, T.; Murata, S.; Kagimura, T.; Omae, K.; Tanaka, A.; Takahashi, K.; Narusawa, M.; Konishi, Y.; Oniki, K.; Miike, T. Characteristics and Transition of Sleep–Wake Rhythm in Nursery School Children: The Importance of Nocturnal Sleep. Clocks Sleep 2024, 6, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Dinich, J.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. Social Jetlag: Misalignment of Biological and Social Time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levandovski, R.; Dantas, G.; Fernandes, L.C.; Caumo, W.; Torres, I.; Roenneberg, T.; Hidalgo, M.P.L.; Allebrandt, K.V. Depression Scores Associate With Chronotype and Social Jetlag in a Rural Population. Chrono- Int. 2011, 28, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remi, J. Humans Entrain to Sunlight - Impact of Social Jet Lag on Disease and Implications for Critical Illness. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 3431–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miike, T. Insufficient Sleep Syndrome in Childhood. Children 2024, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Segawa, M.; Nomura, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Yanagitani, M.; Higurashi, M. The Development of Sleep-Wakefulness Rhythm in Normal Infants and Young Children. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 1993, 171, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbluth, M. Naps in children: 6 months-7 years. Sleep. 1995, 18, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staton, S.; Rankin, P.S.; Harding, M.; Smith, S.S.; Westwood, E.; LeBourgeois, M.K.; Thorpe, K.J. Many naps, one nap, none: A systematic review and meta-analysis of napping patterns in children 0-12 years. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2020, 101247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, K.; Santon, S.; Sawyer, E.; Pattinson, C.; Haden, C.; Smith, S. Napping, development and health from 0 to 5 years: a systematic review. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.E.; Lane, J.M.; Wood, A.R.; van Hees, V.T.; Tyrrell, J.; Beaumont, R.N.; Jeffries, A.R.; Dashti, H.S.; Hillsdon, M.; Ruth, K.S.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, N.; Spichiger, C.; Mendez, N.; Abarzua-Catalan, L.; Galdames, H.A.; Hazlerigg, D.G.; Richter, H.G.; Torres-Farfan, C. Gestational Chronodisruption Impairs Hippocampal Expression of NMDA Receptor Subunits Grin1b/Grin3a and Spatial Memory in the Adult Offspring. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e91313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, R.W.; McClung, C.A. Rhythms of life: circadian disruption and brain disorders across the lifespan. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-N.; Tain, Y.-L. Light and Circadian Signaling Pathway in Pregnancy: Programming of Adult Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisanti, L.; Olsen, J.; Basso, O.; Thonneau, P.; Karmaus, W. Shift Work and Subfecundity: A European Multicenter Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1996, 38, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspholm, R.; Lindbohm, M.-L.; Paakkulainen, H.; Taskinen, H.; Nurminen, T.; Tiitinen, A. Spontaneous Abortions Among Finnish Flight Attendants. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1999, 41, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, J.E.; Vaughan, L.M.; Huete, A.; Samuels, S.J. Reproductive health outcomes among female flight attendants: an exploratory study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1998, 40, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M.M. Shift work, jet lag, and female reproduction. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 813764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varcoe, T.J.; Boden, M.J.; Voultsios, A.; Salkeld, M.D.; Rattanatray, L.; Kennaway, D.J. Characterisation of the maternal response to chronic phase shifts during gestation in the rat: implications for fetal metabolic programming. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Farfan, C.; Richter, H.G.; Germain, A.M.; Valenzuela, G.J.; Campino, C.; Rojas-García, P.; Forcelledo, M.L.; Torrealba, F.; Serón-Ferré, M. Maternal melatonin selectively inhibits cortisol production in the primate fetal adrenal gland. J. Physiol. 2004, 554, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serón-Ferré, M.; Forcelledo, M.L.; Torres-Farfan, C.; Valenzuela, F.J.; Rojas, A.; Vergara, M.; Rojas-Garcia, P.P.; Recabarren, M.P.; Valenzuela, G.J. Impact of Chronodisruption during Primate Pregnancy on the Maternal and Newborn Temperature Rhythms. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e57710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Hess, D.L.; Kaushal, K.M.; Valenzuela, G.J.; Yellon, S.M.; Ducsay, C.A. Circadian myometrial and endocrine rhythms in the pregnant rhesus macaque: Effects of constant light and timed melatonin infusion. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991, 165, 1777–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nováková, M.; Sládek, M.; Sumová, A. Exposure of Pregnant Rats to Restricted Feeding Schedule Synchronizes the SCN Clocks of Their Fetuses under Constant Light but Not under a Light-Dark Regime. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2010, 25, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, N.; Spichiger, C.; Mendez, N.; Abarzua-Catalan, L.; Galdames, H.A.; Hazlerigg, D.G.; Richter, H.G.; Torres-Farfan, C. Gestational Chronodisruption Impairs Hippocampal Expression of NMDA Receptor Subunits Grin1b/Grin3a and Spatial Memory in the Adult Offspring. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e91313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, S.E.; Le Duc, D.; Roșca, A.E.; Zeca, V.; Chiţimuș, D.M.; Arsene, A.L.; Drăgoi, C.M.; Nicolae, A.C.; Zăgrean, L.; Schöneberg, T.; et al. Behavioral and molecular effects of prenatal continuous light exposure in the adult rat. Brain Res. 2016, 1650, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, R.M.; Blask, D.E.; Andrew, N.; Coogan, A.N.; Figueiro, M.G.; Gorman, M.R.; Janet, E.; Hall, J.E.; Hansen, J.; Nelson, R.J.; et al. Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: a report on the National Toxicology Program’s workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 607–608, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, G.-P.; Stein, Z.A.; Susser, M.W. Obesity in Young Men after Famine Exposure in Utero and Early Infancy. New Engl. J. Med. 1976, 295, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.; Osmond, C.; Winter, P.; Margetts, B.; Simmonds, S. Weight in infancy and death from ischemic heart disease. Lancet 1989, 334, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Lopez-Tello, J.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N. Developmental programming of the female reproductive system-a review. Biol Reprod. 2021, 104, 745–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, F.P.; Jedrychowski, W.; Rauh, V.; Whyatt, R.M. Molecular epidemiologic research on the effects of environmental pollutants on the fetus. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 1999, 107, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, P.; Dhok, A. Effects of Pollution on Pregnancy and Infants. Cureus 2023, 15, e33906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, T.; Naidoo, P.; Naidoo, R.N.; Chuturgoon, A.A. Prenatal Air Pollution Exposure and Placental DNA Methylation Changes: Implications on Fetal Development and Future Disease Susceptibility. Cells 2021, 10, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapehn, S.; Paquette, A.G. The Placental Epigenome as a Molecular Link Between Prenatal Exposures and Fetal Health Outcomes Through the DOHaD Hypothesis. Curr. Environ. Heal. Rep. 2022, 9, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmira, M.; Ariagn, R.L. Influence of light in the NICU on the development of circadian rhythms in preterm infants. Semin. Perinatol. 2000, 24, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morag, I.; Ohlsson, A. Cycled light in the intensive care unit for preterm and low birth. weight infants. Cochrane. Database. Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD006982. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez-Ruiz, S.; Maya-Barrios, J.A.; Torres-Narváez, P.; Vega-Martínez, B.R.; Rojas-Granados, A.; Escobar, C.; Ángeles-Castellanos, M. A light/dark cycle in the NICU accelerates body weight gain and shortens time to discharge in preterm infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2014, 90, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyer, C.; Huber, R.; Fontijn, J.; Bucher, H.U.; Nicolai, H.; Werner, H.; Molinari, L.; Latal, B.; Jenni, O.G. Cycled Light Exposure Reduces Fussing and Crying in Very Preterm Infants. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e145–e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyer, C.; Huber, R.; Fontijn, J.; Bucher, H.U.; Nicolai, H.; Werner, H.; Molinari, L.; Latal, B.; Jenni, O.G. Very preterm infants show earlier emergence of 24-hour sleep–wake rhythms compared to term infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkees, S.A.; Mayes, L.; Jacobs, H.; Gross, I. Rest-activity patterns of premature infants are. regulated by cycled lighting. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binns, C.; Lee, M.; Low, W.Y. The Long-Term Public Health Benefits of Breastfeeding. Asia Pac. J. Public Heal. 2016, 28, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, C.; Lyden, E.; Furtado, J.; Van Ormer, M.; Anderson-Berry, A. A Comparison of Nutritional Antioxidant Content in Breast Milk, Donor Milk, and Infant Formulas. Nutrients 2016, 8, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessì, A.; Pianese, G.; Mureddu, P.; Fanos, V.; Bosco, A. From Breastfeeding to Support in Mothers’ Feeding Choices: A Key Role in the Prevention of Postpartum Depression? Nutrients 2024, 16, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanalçı, C.; Bilici, S. Biological clock and circadian rhythm of breast milk composition. Chrono- Int. 2024, 41, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italianer, M.F.; Naninck, E.F.G.; Roelants, J.A.; Van Der Horst, G.T.; Reiss, I.K.M.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Joosten, K.F.M.; Chaves, I.; Vermeulen, M.J. Circadian Variation in Human Milk Composition, a Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, L.A.; Wilson, D.; Spong, J.; Fitzgibbon, C.; Deacon-Crouch, M.; Lenz, K.E.; Skinner, T.C. Maternal Circadian Disruption from Shift Work and the Impact on the Concentration of Melatonin in Breast Milk. Breastfeed. Med. 2024, 19, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manková, D.; Švancarová, S.; Štenclová, E. Does the feeding method affect the quality of infant and maternal sleep? A systematic review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2023, 73, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madar, A.A.; Kurniasari, A.; Marjerrison, N.; Mdala, I. Breastfeeding and Sleeping Patterns Among 6–12-Month-Old Infants in Norway. Matern. Child Heal. J. 2023, 28, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Forrester, R.I. Association between breastfeeding and new mothers’ sleep: a unique Australian time use study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitzthum, V.J.; Thornburg, J.; Spielvogel, H. Impacts of nocturnal breastfeeding, photoperiod, and access to electricity on maternal sleep behaviors in a non-industrial rural Bolivian population. Sleep Heal. 2018, 4, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Ganesh, R. Vitamin D deficiency in exclusively breast-fed infants. Indian J. Med. Res. 2008, 127, 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Terashita, S.; Nakamura, T.; Igarashi, N. Longitudinal study on the effectiveness of vitamin. D supplements in exclusively breast-fed infants. Clin. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2017, 26, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durá-Travé, T.; Gallinas-Victoriano, F. Pregnancy, Breastfeeding, and Vitamin D. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhamou, I. Sleep disorders of early childhood: a review. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2000, 37, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sadeh, A.; Tikotzky, L.; Scher, A. Parenting and infant sleep. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, H.; Cook, F.; Bayer, J.; Le, H.N.; Mensah, F.; Cann, W.; Symon, B.; James-Roberts, I.S. Preventing Early Infant Sleep and Crying Problems and Postnatal Depression: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e346–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miike, T.; Oniki, K.; Toyoura, M.; Tonooka, S.; Tajima, S.; Kinoshita, J.; Saruwatari, J.; Konishi, Y. Disruption of Circadian Sleep/Wake Rhythms in Infants May Herald Future Development of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Clocks Sleep 2024, 6, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, R.ö.; Temel, A.B. Effect of soothing techniques on infants' self- regulation behaviors (sleeping, crying, feeding): A randomized controlled study. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 16, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.L.; Master, L.; Buxton, O.M.; Savage, J.S. Patterns of infant-only wake bouts and night feeds during early infancy: An exploratory study using actigraphy in mother-father-infant triads. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, S.; Davlantis, K.S.; Georgieff, N.; Geoffray, M.-M.; Speranza, M.; Anderson, G.M.; Xavier, J.; Botbol, M.; Oriol, C.; Bellissant, E.; et al. Autism as a Disorder of Biological and Behavioral Rhythms: Toward New Therapeutic Perspectives. Front. Pediatr. 2015, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.; Lebourgeois, M.K.; Geiger, A.; Jenni, O.G. Assessment of chronotype in four-to. eleven-year-old children: reliability and validity of the Children’s Chronotype Questionnaire (CCTQ). Chronobiol. Int. 2009, 26, 992–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpkin, C.T.; Jenni, O.G.; Carskadon, M.A.; Wright, K.P.; Akacem, L.D.; Garlo, K.G.; LeBourgeois, M.K. Chronotype is associated with the timing of the circadian clock and sleep in toddlers. J. Sleep Res. 2014, 23, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herxheimer, A. Jet lag. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008, 2008, 2303. [Google Scholar]

- Sack, R.L. The pathophysiology of jet lag. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2009, 7, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, J. Approaches to the Pharmacological Management of Jet Lag. Drugs 2018, 78, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, K.J.; Abbott, S.M. Jet Lag and Shift Work Disorder. Sleep Med. Clin. 2015, 10, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolla, B.P.; Auger, R.R. Jet lag and shift work sleep disorders: How to help reset the internal clock. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2011, 78, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J.A.; Weiss, M.R. Insufficient sleep in adolescents: causes and consequences. Minerva Pediatr. 2017, 69, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serin, Y.; Tek, N.A. Effect of Circadian Rhythm on Metabolic Processes and the Regulation of Energy Balance. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, A.; Miike, T.; Uezono, K.; Kawasaki, T. A school refusal case with biological rhythm disturbance and melatonin therapy. Brain Dev. 1994, 16, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldham, M.A.; Lee, H.B.; Desan, P.H. Circadian Rhythm Disruption in the Critically Ill: An Opportunity for Improving Outcomes. Crit. Care. Med. 2016, 44, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, A.; Jhodoi, T.; Miike, T. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Abnormal Biological Rhythms in School Children. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 2000, 8, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miike, T.; Tomoda, A.; Jhodoi, T.; Iwatani, N.; Mabe, H. Learning and memorization impairment in childhood chronic fatigue syndrome manifesting as school phobia in Japan. Brain Dev. 2004, 26, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriazo, S.; Ramos, A.M.; Sanz, A.B.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Kanbay, M.; Ortiz, A. Chronodisruption: A Poorly Recognized Feature of CKD. Toxins 2020, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, J.A.; Lombardi, G.; Weydahl, A.; Banfi, G. Biological rhythms, chronodisruption and chrono-enhancement: The role of physical activity as synchronizer in correcting steroids circadian rhythm in metabolic dysfunctions and cancer. Chrono- Int. 2018, 35, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.J.; Purvis, T.E.; Mistretta, J.; Scheer, F.A.J.L. Effects of the Internal Circadian System and Circadian Misalignment on Glucose Tolerance in Chronic Shift Workers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touitou, Y.; Reinberg, A.; Touitou, D. Association between light at night, melatonin secretion, sleep deprivation, and the internal clock: Health impacts and mechanisms of circadian disruption. Life Sci. 2017, 173, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]