1. Introduction

Hyperspectral (HS) imaging extends beyond the conventional three-channel RGB representation by capturing a larger number of spectral bands across a continuous electromagnetic spectrum. This rich spectral resolution enables the differentiation of subtle material compositions and surface characteristics that remain indistinguishable in standard RGB imaging modalities. Consequently, HS images have been widely employed across diverse scientific and industrial domains, including image classification [

1,

2,

3], remote sensing for land cover mapping and resource exploration [

4,

5,

6,

7], biomedical imaging for disease diagnosis and tissue characterization [

8,

9], and environmental surveillance for pollution detection and ecological monitoring. Traditionally, HS data acquisition relies on spectrometers that sequentially scan scenes along either the spectral or spatial dimensions, and thus inherently imposes significant temporal constraints. The sequential nature of such scanning methodologies renders them inefficient for capturing dynamically evolving phenomena, thereby limiting their applicability in real-time and high-speed imaging scenarios.

To address the limitations inherent in traditional HS imaging systems, snapshot compressive imaging (SCI) systems [

10,

11,

12,

13] have been developed, enabling the acquisition of HS images at video frame rates. Among these, coded aperture snapshot spectral imaging (CASSI) [

14,

15,

16] has emerged as a promising and innovative imaging modality that allows for the real-time capture of high-quality spatial and spectral information. CASSI leverages a coded aperture along with a disperser to modulate the HS signals across different wavelengths, effectively compressing them into a 2D measurement. Despite the promising potential of video-rate HS capture, the sensing capability of CASSI systems remains constrained by their limited ability to effectively capture sufficient incident light due to significant light attenuation in the coded aperture and dispersive elements. Moreover, the multiplexing nature of CASSI may also result in a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), particularly in low-light conditions or when capturing dynamic scenes. Consequently, enhancing the light efficiency of CASSI remains a critical challenge, necessitating the development of advanced optical designs, improved coding strategies, and noise-robust reconstruction algorithms to mitigate these constraints and optimize the system’s overall sensing performance. More recently, Motoki et al. [

17] implemented a spatial–spectral encoding approach by integrating an array of 64 complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS)-compatible Fabry–P

rot filters directly onto a monochromatic image sensor, dubbed as random Array of Fabry–P

rot Filter (FAFP). This design enables efficient spectral differentiation while maintaining high optical transmission, thereby optimizing light throughput and minimizing signal loss. The system achieves a measured sensitivity of 45% for visible light, ensuring effective photon utilization, while the spatial resolution of 3 pixels at a 3 dB contrast level allows for accurate feature preservation. The integration of these filters facilitates high-fidelity hyperspectral image acquisition by reducing spectral cross-talk and enhancing the robustness of subsequent reconstruction algorithms. In addition this optical encoding system operates at a frame rate of 32.3 frames per second (fps) at VGA resolution, meeting the practical requirements for real-time hyperspectral imaging applications. Similar to the CASSI system, the encoded measurement in the FAFP system remains a 2D snapshot image. Despite employing a different spectral encoding mechanism, FAFP shares the fundamental principle of compressing high-dimensional HS information into a lower-dimensional representation. This compression inherently introduces challenges in the reconstruction process, as recovering the full spectral–spatial information from a single 2D measurement remains an ill-posed inverse problem. Consequently, advanced computational reconstruction techniques are required to accurately retrieve the HS data while mitigating spectral distortion and preserving spatial details.

To tackle the challenging reconstruction task, various advanced methodologies have been proposed, including model-based optimization techniques, end-to-end (E2E) learning-based approaches, and deep unrolling pipelines. Traditional model-based methods [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] typically employ mathematical optimization frameworks that incorporate domain-specific priors, such as sparsity, low-rank constraints, or total variation regularization, to enhance reconstruction accuracy and mitigate ill-posedness. While these methods offer theoretical interpretability and robustness, they often suffer from high computational costs and limited adaptability to complex real-world senarios. In contrast, E2E learning-based techniques [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

29] leverage deep neural networks to establish a direct mapping between the compressed measurements and the target HSIs, effectively bypassing the design of the hand-crafted priors. These methods have demonstrated remarkable performance improvements by learning inherent feature representations from large-scale datasets, enabling efficient and high-quality reconstructions. However, the black-box nature of deep learning models poses challenges in interpretability and generalization to unseen imaging conditions.

To bridge the gap between model-based and deep learning approaches, deep unrolling pipelines (DUN) [

26,

30,

31,

32,

33] have emerged as a hybrid solution, integrating iterative optimization schemes with trainable neural network components. By unrolling traditional iterative algorithms into a finite number of network layers, these methods retain interpretability while potentially accelerating the reconstruction process through learned parameter adaptation. Moreover, the integration of data-driven prior learning through deep neural networks and the explicit model representation in DUNs has the potential to achieve high-fidelity HS image reconstruction.

Although these recent advancements have significantly improved the reconstruction of HS images from compressed measurements, several critical challenges remain unresolved, particularly in terms of computational efficiency and generalization in real-world imaging systems, necessitating further research efforts. The process of HS image reconstruction from highly compressed measurements continues to be a major bottleneck due to the inherent trade-offs between reconstruction accuracy, processing speed, and robustness under diverse imaging conditions. Therefore, a comprehensive review of existing reconstruction methods, along with a detailed analysis of their respective advantages and limitations, is essential to provide deeper insights into the current state of the field. Such an evaluation will not only facilitate a better understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of various approaches but also highlight key areas that require further innovation. Specifically, we begin by introducing the fundamental image formation models for HS images. We then provide a comprehensive review and comparison of three major reconstruction approaches: model-based methods, end-to-end learning-based techniques, and deep unfolding frameworks. Additionally, we briefly summarize the commonly used HS image datasets and performance evaluation metrics associated with these methods. To provide practical insights, we systematically evaluate and compare several representative algorithms through simulations on publicly available open-source datasets. Finally, we highlight key challenges and emerging trends in the field, aiming to inspire future research toward the development of more efficient, accurate, and robust HS image reconstruction frameworks.

2. Spectral Snapshot Imaging Model

The acquisition of a three-dimensional HS data cube-comprising two spatial dimensions and one spectral dimension-without employing scanning mechanism, remains a fundamental challenge. This limitation primarily stems from the constraints of conventional detector technologies, which are typically restricted to one-dimensional (1D) or two-dimensional (2D) sensor arrays. These conventional configurations are inherently incapable of capturing the complete spectral-spatial information simultaneously, necessitating alternative approaches to enable snapshot acquisition. Furthermore, the HS imaging process is intrinsically subject to trade-offs among several critical system parameters, including spectral resolution, spatial resolution, acquisition time, and optical throughput. Optimizing any one of these parameters often necessitates concessions in the others, making the design of high-performance systems a complex and tightly coupled optimization problem.

To address the above-mentioned limitations and facilitate real-time, compact, and efficient HS imaging, compressive sensing (CS) [

34] frameworks have been widely adopted. CS leverages the inherent sparsity or compressibility of natural scenes in appropriate transform domains to enable the reconstruction of high-dimensional data from a significantly reduced number of measurements. By integrating signal sparsity assumptions with innovative optical encoding strategies, CS-based methods offer a viable pathway toward snapshot HS imaging with reduced hardware complexity and faster acquisition speeds. In recent years, a variety of compressive spectral imaging modalities have been developed and demonstrated significant advancements in dynamic spectral data acquisition. Notably, the Computed Tomography Imaging Spectrometer (CTIS) [

35,

36] employs a diffractive optical element to project the three-dimensional spectral data cube into a series of two-dimensional projections, which are subsequently reconstructed through tomographic algorithms. Similarly, the Coded Aperture Snapshot Spectral Imager (CASSI) [

11,

12,

14] utilizes a coded aperture in conjunction with a dispersive element to modulate and shear the incoming light, enabling the encoding of spectral-spatial information into a single 2D snapshot. More recently, a novel HS sensor based on a CMOS-compatible random Array of Fabry–P

rot Filters (FPFA sensor) [

17] has been explored, and manifests great advantages of high sensitivity, compact size (CMOS-compatible). To this end, these systems have collectively demonstrated remarkable potential for real-time and resource-efficient HS imaging. Next, we present the imaging process in the CASSI and the FPFA systems and their mathematical formulation.

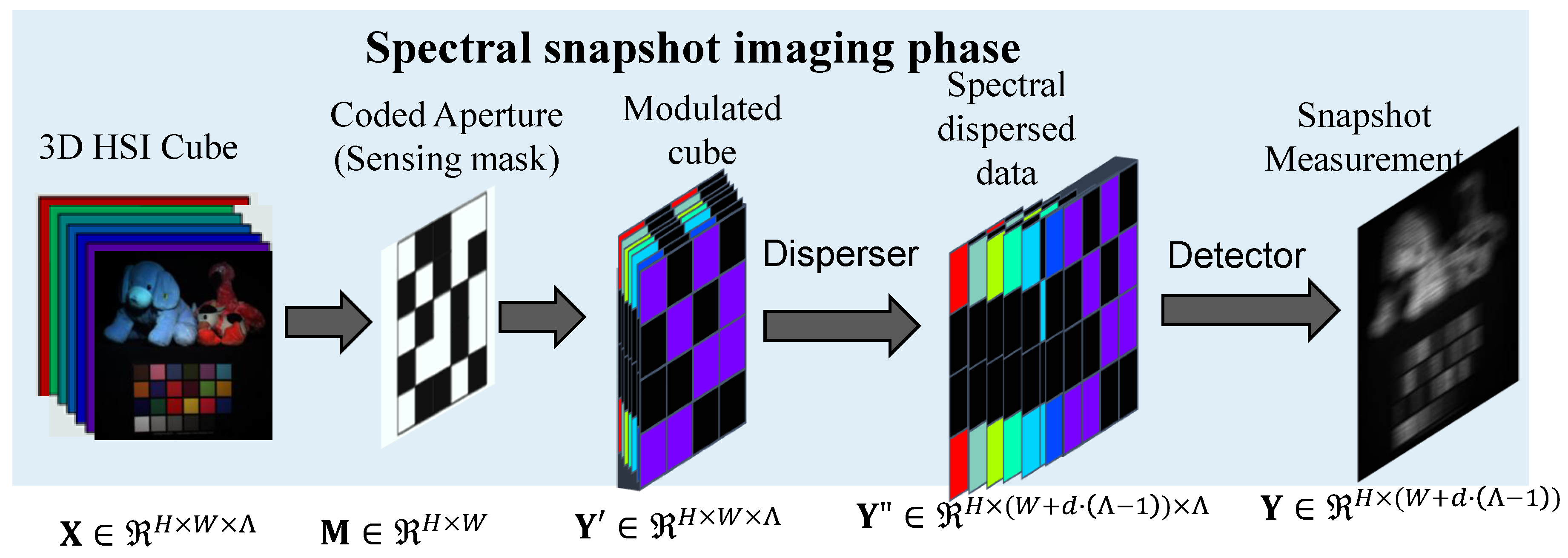

CASSI imaging system: the CASSI imaging or encoding system primarily comprises the following key components: 1) imaging optics for capturing the light from the target scene; 2) coded aperture (sensing mask) as a spatial light modulator for encodeing the incoming light in a spatially varying manner; 3) dispersive element for perfoming wavelength-dependent shift to effectively spread the spectral components across the spatial domain; 4) 2D focal plane array as detector for integrating the spectrally shifted and spatially modulated light into a single 2D compressed measurement. An overview of the fundamental CASSI imaging process is illustrated in

Figure 1. Specifically, let us consider a 3D HS image denoted by

, where

H and

W correspond to the spatial dimensions—height and width of the scene—and

denotes the number of discrete spectral bands. In CASSI system, a coded aperture (also referred to as a spectral sensing mask), represented as

, is employed to spatially modulate the image at each spectral band

. As a result, the modulated intermediate image for each spectral slice is formulated as:

where

denotes the 2D image corresponding to the

-th spectral band, ⊙ indicates the element-wise multiplication, and

represents the modulated cube. Subsequently, the modulated spectral data cube

undergoes a wavelength-dependent spatial displacement along the horizontal axis, implemented by a dispersive optical element. This process introduces a spectral shear, whereby each spectral band is shifted laterally by an amount proportional to its wavelength index. Let

d denote the dispersion step size, i.e., the number of pixels by which each successive spectral band is shifted. As a result, the spectrally dispersed data cube

is generated, where the spatial width is extended to accommodate the cumulative shifts across all

spectral bands. The dispersive process can be formally described as follows:

where,

h and

w denote the spatial coordinates corresponding to the vertical and horizontal positions, respectively, in the imaging plane. After spectral dispersion, the resulting data cube

contains spatially modulated and laterally shifted spectral components. To obtain the final 2D compressive measurement, denoted as

, the system performs an integration along the spectral dimension. This spectral projection aggregates the energy contributions from all shifted spectral bands into a single 2D image on the detector plane. Mathematically, this process can be formulated as:

where

represents the additive measurement noise, which arises from various sources such as sensor readout errors, photon shot noise, and thermal fluctuations during the acquisition process. To facilitate mathematical analysis and algorithmic implementation, the measurement model described from Eqs.

1 to

3 is reformulated using a matrix-vector representation. This compact form allows the compressive sensing problem to be addressed using linear algebraic tools and optimization frameworks. The reformulated model is expressed as follows:

where

refers to the re-shaped sensing matrix, typically characterized by its fat (i.e., underdetermined) and highly structured nature. In most CASSI frameworks, the same coded aperture (sensing mask) is uniformly applied across all spectral bands, and then a dispersive element is incorporated to introduce a wavelength-dependent spatial shift, thereby enabling the spectral encoding of the 3D hyperspectral data cube into a 2D measurement through spatial integration.

The FPFA sensor: a recent approach [

17] introduces a fundamentally different compressive imaging strategy based on spatial-spectral coded optical filters. This imaging method employs a random array of Fabry–P

rot filters monolithically integrated onto a CMOS sensor. Each filter cell transmits light at specific wavelengths, creating a spatially random spectral measurement matrix, where light passes through the filter array directly, with no dispersive element [

17,

37]. The spectral encoding is achieved via the transmittance patterns of the filters, which are designed to minimize correlation between wavelengths. Given a 3D HS image

and the equipped Fabry–P

rot filters

with wavelength-dependent and spatially varying transmittance (weights), and the imaging process in the FPFA sensor can be typically modeled by taking a weighted sum along the spectral dimension as:

Similar as in the CASSI system, Eq.

5 can be rewriten in a compact form:

, where

is typically sparse and highly structured, depending on the specific layout and transmission profile of the FP filters. It reflects the mapping from the 3D spectral space to the 2D measurement space. Thanks to the compact integration of the FPFA with CMOS sensors, the system benefits from: 1) High sensitivity, due to narrowband transmission of the resonant cavities; 2) Compact and CMOS-compatible hardware, suitable for low-power and portable platforms; 3) Single-shot and real-time operation, enabling applications in real-world consumer electronics such as smartphones and drones. The comparisons between the CASSI and FPFA sensors are illustrated in

Table 1.

Following the spectral compressive measurement, a critical step involves reconstructing the latent 3D HS image from the compressed 2D observation . This inverse problem is inherently ill-posed due to the significant dimensionality reduction during acquisition. The subsequent section will presents the existing computational reconstruction methods for the spectral snapshot imaging systems.

3. Computational Reconstruction Methods

To date, a wide range of computational reconstruction techniques have been developed to address the challenges inherent in Coded Aperture Snapshot Spectral Imaging (CASSI) systems. These approaches primarily fall into three major categories: traditional model-based methods [

11,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

38], deep learning-based methods [

23,

24,

25,

26,

39,

40] and deep unfolding framework [

30,

32,

33,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

3.1. Model-Based Computational Reconstruction Methods

Model-based methods [

11,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

38] formulate the HS image reconstruction as an inverse problem, leveraging explicit physical models of the spectral snapshot acquisition process. These methods typically incorporate domain knowledge through regularization terms—such as sparsity, low-rank priors, or total variation—and solve the resulting optimization problem using iterative algorithms. Specifically, given the known sensing matrix

, a straightforward and intuitive strategy for estimating the latent HS signal

from the compressed measurement

is to minimize the reconstruction error via a data fidelity-driven objective. This heuristic approach can be formulated as the following optimization problem:

where

stands for the Frobenium norm. This formulation seeks the solution that best explains the observed measurement in the least-squares sense. It is well recognized that the HS image reconstruction problem from compressive measurements is severely ill-posed, as the number of unknown variables in the latent signal

far exceeds the number of observations in

. This imbalance results in an underdetermined linear system, making the accurate and robust recovery of the HS image extremely challenging.

To mitigate this issue, a substantial body of work has focused on incorporating hand-crafted image priors that capture the intrinsic structure and redundancies within HS data. These priors—such as sparsity, low-rankness, smoothness, or spectral correlation—serve to constrain the solution space and guide the reconstruction process toward more plausible results. Accordingly, the inverse problem is reformulated as a regularized optimization task, expressed as:

where

is the data fidelity term ensuring consistency with the measurement,

denotes the regularization function encoding prior knowledge while

is a hyperparameter that balances the trade-off between measurement fidelity and prior enforcement. Most existing model-based approaches have focused on designing effective prior models and developing efficient optimization algorithms to enhance the stability, robustness, and accuracy of HS image reconstruction. In the following, we introduce several widely adopted and representative model-based reconstruction techniques based on the adopted priors that have demonstrated promising performance in the context of compressive HS imaging.

Sparsity-based Prior: Despite the inherently high ambient dimensionality of HS images, their intrinsic information content can often be effectively captured using only a limited number of active components when represented in a suitable transform or dictionary domain. This property reflects the inherent sparsity of HS data, which serves as a powerful prior in addressing the challenges of reconstruction from compressed measurements. Zhang et al. [

46] presents a reconstruction method tailored for miniature spectrometers, and combine sparse optimization with dictionary learning to effectively capture and represent the spectral signatures of the scene. By learning an over-complete dictionary from training data, the method promotes a sparse representation of the hyperspectral signal, enabling accurate reconstruction from a limited number of measurements. Figueiredo et al. [

22] introduce an efficient gradient projection algorithm designed to solve sparse reconstruction problems via

-norm minimization. Operating within the compressed sensing framework, the method iteratively projects the solution onto a set defined by sparsity constraints, thereby efficiently solving the underdetermined inverse problem. Its generality and computational efficiency have made it a foundational algorithm, supporting a range of applications including hyperspectral image reconstruction where robust recovery from compressed measurements is critical. In addition, Wang et al. [

19] exploits the nonlocal self-similarity of hyperspectral images by adaptively learning sparse representations from similar patches. By integrating nonlocal priors into the sparse reconstruction framework, the method effectively captures both spatial and spectral correlations, leading to enhanced restoration quality—especially in preserving fine details and reducing noise. Bioucas-Dias at el. [

47] introduced the two-step iterative shrinkage/thresholding algorithm (TwIST) for solving the optimization task with multiple nonquadratic convex regularizers including sparsity. TwIST has popularly applied for the HS image reconstruction as a baseline model-based method.

Total Variation (TV)-based Prior: TV-based methods represent a prominent class of model-based approaches for HS image reconstruction. These methods are grounded in the assumption that natural images exhibit spatial piecewise smoothness, where intensity variations are often sparse and localized. In the context of HS images, this property is commonly exploited to preserve salient edges and suppress noise during the recovery process. A representative implementation is the

Generalized Alternating Projection with TV (GAP-TV) [

21], which alternates between enforcing data fidelity through projection onto the measurement constraint and applying TV denoising. Concretely, the GAP optimization iterately update the HS estimation by projecting the current estimate onto two sets: 1) data consistency set for enforcing

and 2) prior constraint set for enforcing the TV regularization. Moreover, Eason at el. [

48] proposed to solve the TV-regularized optimization probelem for CS inverse task with a continuation method, which involves gradually reducing the regularization parameter (or using a sequence of progressively “tighter” TV constraints). Such a scheme allows the optimization to start from an easier (more regularized) problem and slowly transition to the target problem, thereby improving both convergence speed and reconstruction quality. The method exhibits robustness to noise and measurement artifacts, making it well-suited for for practical compressive HS imaging applications.

Low-Rank-based Prior: By representing a HS image as a matrix or a tensor, one leverages the observation that the data often reside in a subspace of considerably lower dimension than the full ambient space. In other words, while the ambient space of a HS image with dimensions

is very high-dimensional, the intrinsic information contained in the data exhibits strong correlations among spectral bands (and, often, across spatial locations). Thus, the rank of the matrix represntation or the multilinear rank of the tensor is typically much lower than the maximum possible rank. Inspired by the low-rank insight in HS imaging, Liu et al. [

18] concentrate on global matrix rank minimization, employing a nuclear norm surrogate to enforce the low-dimensional structure of the underlying image. This approach demonstrates that by exploiting this global low-rankness—even when the number of measurements is significantly limited—it is possible to achieve high-quality reconstructions in snapshot compressive imaging systems. In contrast, Fu et al. [

49] incorporate the low-rank property at a more localized level, taking advantage of the fact that HS images exhibit strong correlations not only across spectral bands but also among spatially similar regions. This dual exploitation of spectral and spatial redundancy leads to an enhanced restoration performance by better preserving fine details and reducing artifacts. Furthemore, Zhang et al. [

50] extend the concept by treating HS data as a multidimensional tensor and applying dimension-discriminative low-rank tensor recovery. By directly modeling the inherent multi-way structure of HS images, the method retains the intrinsic spectral and spatial correlations that are often lost in vectorized formulations, culminating in superior reconstruction quality and robustness.

Nonlocal-Self Similarity-based prior: Nonlocal self-similarity (NSS) describes the intrinsic property of natural images wherein small, localized regions—referred to as patches or blocks—exhibit substantial resemblance to other spatially distant patches within the same image. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in HS images, which, due to their high spectral resolution and inherent spatial redundancy, often contain repetitive spatial structures such as textures, edges, and homogeneous regions across different locations. By leveraging the NSS property, it becomes possible to more effectively constrain the ill-posed inverse problem of HS image reconstruction. This is achieved by enforcing that groups of nonlocally similar patches maintain a coherent, typically low-dimensional, structural representation. He et al.[

20] exemplify the application of this concept by proposing an iterative framework that integrates nonlocal spatial denoising—guided by NSS priors—with a global low-rank spectral subspace model. While the primary objective of their work is HS image restoration (specifically denoising and inpainting), the underlying methodology grounded in NSS can be naturally extended to the context of compressive spectral snapshot reconstruction. Moreover, the NSS prior is conceptually aligned with low-rank modeling approaches, as both capitalize on structural redundancy. The integration of NSS-based regularization within HS reconstruction frameworks is further explored and validated in works such as [

49,

50].

Table 2 provides a comprehensive comparison of four representative categories of model-based HS image reconstruction methods. While these approaches effectively integrate knowledge of the physical image degradation process—leading to enhanced interpretability and well-defined mathematical formulations—they often face inherent limitations in representational capacity. This shortcoming primarily arises from the difficulty in designing hand-crafted priors that are both expressive and sufficiently generalizable across diverse scenes and imaging conditions. As a result, the performance of model-based methods may degrade when confronted with complex or nonstationary structures that deviate from the assumed prior assumptions.

3.2. Deep Learning-Based Reconstruction Methods

Motivated by the significant breakthroughs achieved by deep learning in various computer vision tasks, researchers have increasingly turned to data-driven approaches for HS image reconstruction. Among these, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

24,

25,

27,

51] and, more recently, transformer-based architectures[

28,

39,

40] have emerged as dominant frameworks due to their superior capacity to model complex spatial–spectral dependencies. These methods depart from traditional model-based paradigms by employing end-to-end (E2E) learning schemes, wherein a neural network is trained to directly learn a non-linear mapping from the compressed spectral measurements to the corresponding high-dimensional HS image [

24,

25,

29,

39,

51].

This deep learning strategy eliminates the need for explicit prior modeling and physical forward operators, instead relying on large amounts of measurement/gtarget pairs to implicitly learn underlying structures. Specifically, given a set of

N training samples consisting of snapshot measurements and their corresponding HS targets, denoted as

for

, end-to-end (E2E) methods aim to learn a mapping function parameterized by

that models the relationship between the snapshot inputs and the HS targets. This is achieved by minimizing a predefined loss function that quantifies the discrepancy between the reconstructed outputs and the ground-truth targets. When the loss is defined by the mean squared error (MSE), the optimization problem is given by:

where

denotes the output of the neural network parameterized by

, taking the snapshot measurement

as input and producing the corresponding HS reconstruction. Notably, conventional E2E learning methods [

23,

24,

25,

27,

29,

40,

51,

52,

53] do not require prior knowledge of the sensing mask, as the reconstruction model implicitly learns the inverse mapping from the measurement space to the HS domain directly from data. Recently, several studies [

28,

39,

54,

55] have proposed incorporating the sensing mask into the network architecture to improve reconstruction performance. This paradigm has been explored in both Coded Aperture Snapshot Spectral Imaging (CASSI) systems [

28,

39] and Filter-Pixel-Focal-Array (FPFA) based sensors [

54,

55], where the integration of sensing priors into the learning process has demonstrated notable performance gains. In addition to the learning paradigm, the design of network architectures within E2E methods has been a critical factor influencing the performance of HS image reconstruction. The architecture directly determines the model’s capacity to capture and exploit the complex spatial-spectral correlations inherent in hyperspectral data. To this end, recent research efforts have focused on developing more effective and computationally efficient neural network architectures tailored for HS image reconstruction. These advancements have evolved progressively from CNNs[

23,

24,

25], which are adept at capturing local spatial features to Transformer [

28,

39,

40], which leverage self-attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies across spatial and spectral dimensions, and multi-layer perceptron (MLP)-based models[

55], which offer enhanced modeling flexibility and global feature extraction through linear projections. Subsequently, we present the representative architecture design in the E2E learning methods.

CNN-base architecture: CNNs have been widely adopted in early E2E HS image reconstruction methods due to their strong ability to capture local spatial structures and spectral correlations. These architectures typically consist of stacked convolutional layers that progressively extract hierarchical features from the input measurements. The use of small receptive fields enables the model to focus on fine-grained spatial patterns, while deeper layers can aggregate contextual information to improve reconstruction quality. For example, Hu et al. [

24] investigate a high-resolution dual-domain learning strategy by utilizing a CNN architecture that jointly operates in both the spatial and spectral domains. Through dedicated convolutional blocks and multi-scale feature extraction, HDNet [

24] effectively preserves spatial details while maintaining spectral fidelity. This dual-domain approach mitigates the common trade-off between resolution and spectral accuracy encountered in compressive spectral imaging. Miao et al. [

25] propose a dual-stage generative model designed for efficient and high-quality HS image reconstruction, dubbed as

-net.

-net firstly employs a self-attention generator with a hierarchical channel reconstruction (HCR) strategy to generates an initial reconstruction of the HS imageI from the 2D snapshot measurement, and then a refinement stage composed of a small U-net and residual learning is developed to boost up the quality of reconstructed images from the first stage. Wang et al. [

26] focuse on the incorporation of a learned deep spatial-spectral prior into the reconstruction process. The designed CNN architecture is purposefully designed to capture both local spatial context and long-range spectral dependencies. By integrating spatial and spectral cues into the feature extraction process, the network can resolve complex variations in hyperspectral data, leading to more faithful reconstructions. Meng et al. [

23] embed spatial-spectral self-attention mechanisms into the CNN framework to explore feature dependencies more effectively. The self-attention modules enable the network to dynamically focus on the most informative spatial and spectral features, thereby enhancing the reconstruction accuracy. Moreover, the design prioritizes computational and hardware efficiency, making it particularly attractive for low-cost, end-to-end compressive spectral imaging systems. Moreover, Zhang et al. [

27] emphasize both reconstruction quality and interpretability by integrating an optimal sampling strategy into its end-to-end learning process, thereby directly aligning the data acquisition with the reconstruction paradigm, while Cai et al. [

56] introduce a binarization strategy into the CNN-based architecture. By employing binary weights and activations, the method achieves substantial reductions in memory usage and inference time, which is crucial for real-time or resource-constrained applications. More recently, Han et al. [

29] employ Neural Architecture Search (NAS) to automatically discover optimal architectural configurations composed of diverse convolutional variants. The resulting architecture demonstrates both high efficiency and strong reconstruction performance, thereby validating the effectiveness of NAS in identifying specialized network structures tailored for HS image reconstruction.

Each aformentioned method leverages CNN-based architectures but distinguishes itself through unique design choices—ranging from optimization unrolling and dual-domain processing to architecture search and efficient quantization—to address specific aspects of the reconstruction problem. Despite their effectiveness, CNNs are inherently limited in capturing long-range dependencies due to the locality of convolutional operations, which has motivated the exploration of alternative architectures such as MLPs and Transformers in recent studies.

Transformer-base architecture: Transformer-based architectures have recently emerged as a powerful alternative to convolutional-based models in the E2E learning paradigm for HS image reconstruction. Originally developed for natural language processing and later adapted for vision tasks, Transformers are particularly well-suited for modeling long-range dependencies across both spatial and spectral dimensions—a crucial aspect in HS imaging, where complex correlations often exist over distant regions in both domains. In the context of spectral snapshot measurements, Transformer-based models typically begin by exploring self-attention in window-based spatial and spectral domain to reduce computatioal complexity, enabling the network to adaptively weigh the relevance of different spatial-spectral features [

28,

39,

40,

54,

57,

58,

59]. Cai et al. [

39] initially intruduce a Transformer to HS image reconstruction with the main innovations: Spectral-wise Multi-Head Self-Attention (S-MSA) and Mask-Guided Mechanism (MM), dubbed as mask-guided spectral-wise transformer (MST). The overall architecture follows popular encoder–decoder designs (U-Net) to progressively extracts and fuses hierarchical features while keeping computational costs low. The encoder–decoder arrangement facilitates both local (via convolutions prior to attention) and global (via S-MSA) feature extraction. MST model achieves state-of-the-art reconstruction quality with lower memory and computational overhead by tailoring the attention mechanism to the spectral dimension and by incorporating prior physical knowledge (i.e. the mask). Takabe et al. [

28] propose a versatile HS reconstruction framework that integrates a U-Net backbone with a spectral attention-based Transformer module. To enhance the model’s generalization capability across different measurement conditions, the training process incorporates a diverse set of sensing masks, enabling robust reconstruction performance under varying mask configurations. Cai et al. [

40] introduce a coarse-to-fine sparse Transformer (CST) that leverages a multi-stage refinement strategy by integrating sparse attention mechanisms with hierarchical feature processing. This design effectively balances the modeling of global contextual information—critical for maintaining spectral fidelity—with the refinement of local spatial details, thereby achieving impressive HS image reconstruction. More recently, Wang et al. [

58] investigate a Spatial–Spectral Transformer (denoted as

-Tran) by using two interconnected streams with sptial and sepctral self-attention modeling, repectively. Furthemore, inspired the spatial nonuniform degradation (sensing mask), the

-Tran directly integrate the mask information into both the network’s attention mechanism and its loss function to disentangle the entangled measurement caused by spatial shifting and mask coding. Luo et al. [

59] propose a dual-window multiscale transformer (DWMT) to capture both fine local details and broad contextual information by employing dual-window processing. Since DWMT realize the attention mechanism separately within each window, reducing the computational burden compared to a global self-attention while still providing a sufficient receptive field to capture the complex spatial–spectral relationships. In addition, Yao et al. [

54] propose a spatial–spectral cumulative-attention Transformer (SPECAT) for high-resolution HS image reconstruction in FPFA sensor. The model leverages a dual-branch architecture to independently capture spatial and spectral dependencies through cumulative attention modules, enabling effective cross-dimensional feature fusion. By progressively integrating multi-scale context, SPECAT attains superior reconstruction quality while ensuring computational efficiency.

Overall, Transformer-based architectures have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in HS image reconstruction, offering a powerful framework for extracting complex spatial–spectral features, particularly under compressed sensing scenarios such as snapshot spectral imaging.

MLP-base architecture: Although recent Transformer-based architectures have significantly advanced the efficiency of HS image reconstruction, their computational demands remain a critical bottleneck, particularly for deployment on real-world imaging systems with constrained resources. In response, emerging research has explored the substitution of the self-attention mechanism in Transformers with multi-layer perceptron (MLP)-like operations as a promising alternative [

62,

63,

64,

65]. These MLP-based architectures are adept at capturing non-local correlations and modeling long-range dependencies, offering competitive performance in various computer vision tasks while markedly reducing memory consumption and computational complexity. For instance, Cai et al. [

60] construct a teacher-student network configured with Spectral–Spatial MLP (SSMLP) block for strategically fusing information from conventional RGB imaging and CASSI. This MLP-based model is designed to learn a robust mapping from the jointly encoded RGB–CASSI measurements to the corresponding HS images, and thus not only compensates for the reduced spectral resolution inherent to the CASSI data but also leverages the rich spatial details from the RGB inputs, thereby enhancing the overall reconstruction fidelity. Han et al. [

55] employ cycle Fully-connected layers (CycleFC) to realize the spatial/spectral MLP-based model (S2MLP) for HS image reconstruction in the FPFA sensor, and further embed the mask information into the S2MLP learning branch to mitigate information entangling. Moreover, Cai et al. [

61] extend the MLP paradigm by exploiting an adaptive mask strategy within a dual-camera snapshot framework, named as MLP-AMDC model. In this design, the dual-camera setup enables the simultaneous capture of complementary information streams, while the adaptive mask dynamically modulates the measurement process to optimize the acquisition of spectral data. The MLP-AMDC incorporates these adaptive measurements directly into its learning pipeline, using fully connected layers to integrate information from both cameras. With the explicit cues regarding the spatial and spectral encoding imposed during data collection, a more accurate and robust recovery of HS images has been achieved from highly compressed snapshot measurements.

Overall, MLP-based architectures often achieve performance comparable to Transformer-based methods while being significantly more lightweight, positioning them as an attractive choice for deployment in real-world HS imaging systems.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive comparison of the representative CNN-, Transformer-, and MLP-based categories of the E2E learning methods for HS image reconstruction. Each category is analyzed in terms of its core architectural components, representative models, and design characteristics relevant to HS image reconstruction. The comparison highlights the trade-offs among these approaches, particularly in their ability to capture spatial–spectral correlations, handle global dependencies, and balance reconstruction accuracy with computational efficiency. This classification serves to guide future research directions and practical implementation choices in developing robust and efficient reconstruction networks tailored for snapshot compressive imaging systems. Despite the notable advancements, these brute-force E2E learning approaches face inherent limitations: (1) they fail to exploit the underlying physical degradation models associated with the imaging process, and (2) they often suffer from limited interpretability, making it challenging to analyze or justify the reconstruction outcomes from a principled perspective.

3.3. Deep Unfolding Model (DUM)

To harness the complementary strengths of model-based and deep learning-based approaches, model-guided learning frameworks have garnered considerable attention in the field of HS image reconstruction [

30,

41,

42]. Early efforts in this direction focused on plug-and-play (PnP) algorithms [

41,

42], which integrate pre-trained deep denoisers as implicit priors within an iterative optimization framework. In this setup, the denoiser functions as a regularization component that steers the reconstruction process toward plausible solutions. However, the use of fixed pre-trained denoisers in PnP frameworks often limits adaptability to the specific characteristics of HSI data, resulting in suboptimal reconstructions and slower convergence. To address these limitations, recent work has shifted toward the deep unfolding (or unrolling) paradigm [

32,

33,

43,

44,

45,

66], wherein the iterative steps of a model-based optimization algorithm are reformulated as a trainable deep neural network. This approach enables end-to-end learning of both the data fidelity and prior components, while explicitly incorporating known degradation models.

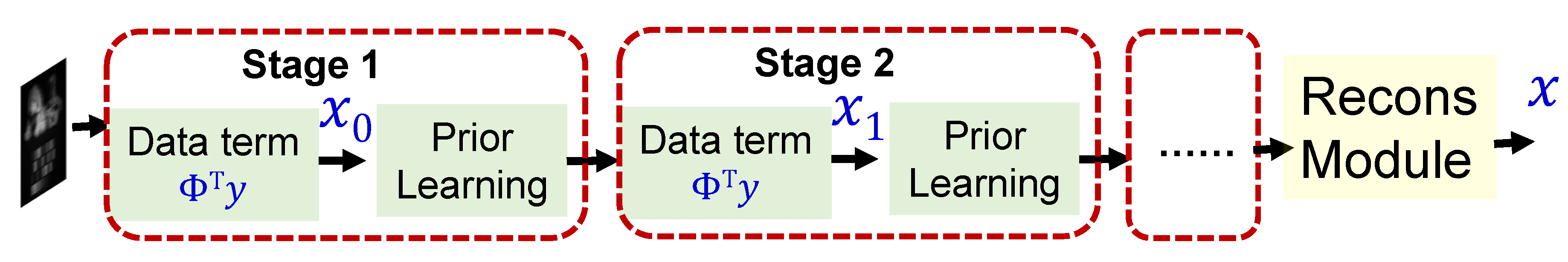

To revisit the optimization formulation presented in Eq.

7, we introduce an auxiliary variable

to facilitate the use of the half quadratic splitting (HQS) technique. This method reformulates Eq.

7 into the following unconstrained minimization problem:

where

is a penalty parameter that enforces consistency between the variables

and

. By decoupling the variables

and

, Eq.

9 can be efficiently solved via alternating minimization over two subproblems:

These two subproblems are solved iteratively until convergence. The first subproblem in Eq.

10, which enforces the data fidelity constraint, admits a closed-form solution and can be interpreted as an inverse projection step. This solution is given by:

The second subproblem in Eq.

10, associated with the regularization term, is typically addressed using a learned image prior implemented via a deep neural network. The update at the

iteration thus be represented as:

where

denotes a neural network parameterized to capture the structural prior of HS images, often tailored for denoising or feature enhancement. This learning-based regularization enhances both the adaptability and performance of the unfolding framework across diverse sensing configurations. These two subproblems are alternately solved in an iterative, multi-stage manner, where each stage corresponds to one iteration of the optimization process. This iterative scheme underpins many model-based deep unfolding networks, where learnable modules are embedded into each iteration to improve flexibility and reconstruction quality. The overall implementation of the DUM is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The state-of-the-art (SoTA) DUMs mainly devote to 1) effective and efficient prior learning network design for spectral-spatial feature synergy and memory-enhanced unfoldinge; 2) adaptive degradation modeling in the data fedelity term. Prior to 2021, most prior learning networks were predominantly constructed using CNN architectures [

51,

53,

67]. However, there has since been a paradigm shift towards Transformer-based models [

32,

33,

43,

44,

45,

66,

68]. In the following, we introduce several representative deep unrolling models (DUMs) that leverage Transformers as the backbone for prior learning.

Degradation-Aware Unfolding Half-Shuffle Transformer (DAUHT) [32]: DAUHT explicitly incorporates degradation modeling into the unfolding process by leveraging a half-shuffle Transformer module. The model alternates between enforcing data fidelity and applying a learned degradation-aware prior, thereby capturing both local and non-local spectral–spatial dependencies. The half-shuffle attention mechanism improves the efficiency of the self-attention computation while mitigating the influence of hardware-induced degradation artifacts.

Pixel Adaptive Deep Unfolding Transformer (PADUT) [33]: This approach aim s to enhance the DUM with pixel-adaptive mechanisms within its Transformer modules. By adjusting the reconstruction parameters on a per-pixel basis, PADUT effectively accounts for spatial variability in HS data. This adaptive strategy enables the DUM to capture fine-grained local variations while simultaneously modeling global contextual information, leading to more accurate and robust reconstructions.

Memory-Augmented deep Unfolding Network (MAUN) [43]: MAUN augments the traditional DUM with an external memory component that stores and refines intermediate features across iterations. This memory module promotes the capture of long-range dependencies and historical reconstruction information, which is particularly beneficial for recovering subtle spectral details. The MAUN thereby achieves improved convergence and reconstruction quality through efficient reuse of contextual information.

Residual Degradation Learning Unfolding Framework (RDLUF) [66]: RDLUF integrates residual learning into the deep unfolding process, directly modeling and compensating for degradation effects. By employing mixing priors that capture both spectral and spatial characteristics, the framework effectively disentangles the reconstruction problem into manageable subproblems. The residual learning component helps in iteratively refining the reconstructed signal, while the dual-prior strategy ensures that both global context and local details are maintained.

Dual Prior Unfolding (DPU) [44]: DPU decomposes the reconstruction process into two intertwined subproblems, each governed by distinct priors. One prior typically captures the data fidelity and degradation characteristics, while the other encodes the intrinsic image structure. The alternating minimization guided by these dual priors enables the network to robustly recover the high-dimensional HS image by enforcing consistency in both the measurement and prior domains.

Spectral-Spatial Rectification (SSR) [45]: SSR focuses on rectifying errors that arise in spectral snapshot compressive imaging by incorporating a spectral-spatial rectification module into the unfolding iterations. The rectification step functions to correct inconsistencies between the spectral and spatial domains, ensuring that the final reconstruction preserves both the global spectral signature and the fine local spatial details. This integrated strategy enhances overall fidelity and mitigates error accumulation inherent in highly compressed reconstructions.

In summary, these DUMs represent a significant shift toward hybrid models that combine principled optimization with learnable components. They address the limitations of purely data-driven approaches by embedding physical degradation models and adaptive mechanisms into the reconstruction process, thereby achieving improved interpretability, convergence speed, and reconstruction quality in HS imaging applications.

4. Hypespectral Image Datasets

Datasets play a pivotal role in assessing the performance of HS image reconstruction algorithms. In recent years, several emerging HS datasets have become available, facilitating both the training and validation of deep learning frameworks. In the following section, we provide an overview of open-source datasets that have significantly contributed to advancing research in HS image reconstruction.

CAVE Dataset: The CAVE dataset [

69] comprises 32 high-quality HS images of various objects and scenes captured under controlled laboratory conditions. Each image typically has a spatial resolution of

pixels and is acquired over a spectral range spanning approximately, sampled in

about 31 narrow spectral bands. Owing to its high spectral fidelity and controlled acquisition conditions, the CAVE dataset has become a de facto benchmark for evaluating reconstruction algorithms under idealized scenarios.

Harvard Dataset: The Harvard dataset [

70] comprises approximately 75 high-resolutionHS images (50 under daylight, 25 under artificial/mixed illumination), and is capturedunder controlled illumination conditions using a Nuance FX camera with an apo-chromatic lens. With roughly 31 spectral channels spanning the visible range (approximately 420–720 nm), it is widely used for developing and testing algorithms that require precise spectral fidelity.

The Harvard dataset, frequently referenced in spectral recovery literature, consists of a relatively small set of hyperspectral images captured in a well-calibrated environment. Characterized by high spatial and spectral resolution, the images in this dataset are obtained under controlled illumination, covering a similar visible spectral range with narrow band spacing. The dataset’s uniformity and precision make it particularly useful for assessing the performance of reconstruction methods in terms of spectral accuracy and fine detail recovery.

ICVL Dataset: Developed by research groups at institutions such as Imperial College London, the ICVL dataset [

71] offers an extensive collection of HS images that capture natural scenes in both indoor and outdoor environments. Typically containing 201 images, each sample in the ICVL dataset is acquired across the visible spectrum (often with 31 to 33 bands) and exhibits a higher level of diversity in scene content. This large-scale dataset serves as an excellent resource for benchmarking RGB to hyperspectral reconstruction methods, as it challenges algorithms with variations in illumination, texture, and natural content.

KAIST Dataset: The KAIST dataset [

72] includes around 30 HS images acquired from real-world outdoor environments. Typically, these images have a resolution of approximately

pixels and feature about 28 spectral channels. Its realistic acquisition conditions highlight the challenges encountered in practical imaging scenarios, such as noise and illumination variability.

Table 4 summarizes four widely adopted HSI datasets in the community, each characterized by small to medium sizes. These datasets vary in key attributes such as data volume, spatial resolution, number of spectral channels, and scene diversity. As HS imaging technology continues to evolve, the availability of larger and more diverse datasets is anticipated, thereby further propelling the research in this field.

5. Result Comparison and Analysis

Recent SoTA studies frequently adopt the extended CAVE dataset for model training, owing to its moderate spatial resolution and diverse scene content, which collectively facilitate efficient learning and robust generalization. For performance evaluation, it is common practice to utilize a representative subset comprising 10 cropped HS scenes from the KAIST dataset, as demonstrated in several recent studies [

23,

24,

32,

33,

39,

66]. The simulation spectral snapshot imaging is widely set as the measurement process in the CASSI. To quantitatively assess reconstruction quality, two widely employed evaluation metrics are the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), which measures pixel-wise fidelity, and the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), which captures perceived structural consistency between the reconstructed and ground-truth images.

We conducte a thorough comparative analysis of between different types of SoTA HS image reconstruction methods. In the CASSI setting, the SoTA techniques included three model-based approaches: TwIST [

47], GAP-TV [

21] and DeSCI [

18], 7 E2E methods:

-Net [

25], DSSP [

26], TSA-Net [

23], HDNet [

24], MST [

39], CST [

40] and DWMT [

59], and 10 DUMs: DGSMP [

31], GAP-Net [

53], ADMM-Net [

51], DAUHST [

32], PADUT [

33], MAUN [

43], RDLUF-L [

66], DPU [

44] and SSR [

45]. All methods were trained using identical training datasets and hyperparameter settings to ensure a fair comparison, and performance was evaluated under the same experimental conditions. Quantitative results were computed using two standard image quality metrics, PSNR and SSIM, across 10 simulated hyperspectral scenes. The comparative results are summarized in

Table 5(a). As shown in

Table 5(a), the E2E learning-based methods consistently outperform conventional model-based approaches, demonstrating the effectiveness of data-driven frameworks in complex reconstruction tasks. Notably, Transformer-based E2E models—such as MST [

39], CST [

40], and DWMT [

59]—exhibit superior performance over CNN-based alternatives including

-Net [

25], DSSP [

26], TSA-Net [

23], and HDNet [

24]. Moreover, DUMs that incorporate Transformer-based prior learning further enhance reconstruction accuracy by effectively leveraging both model-based interpretability and deep feature learning.

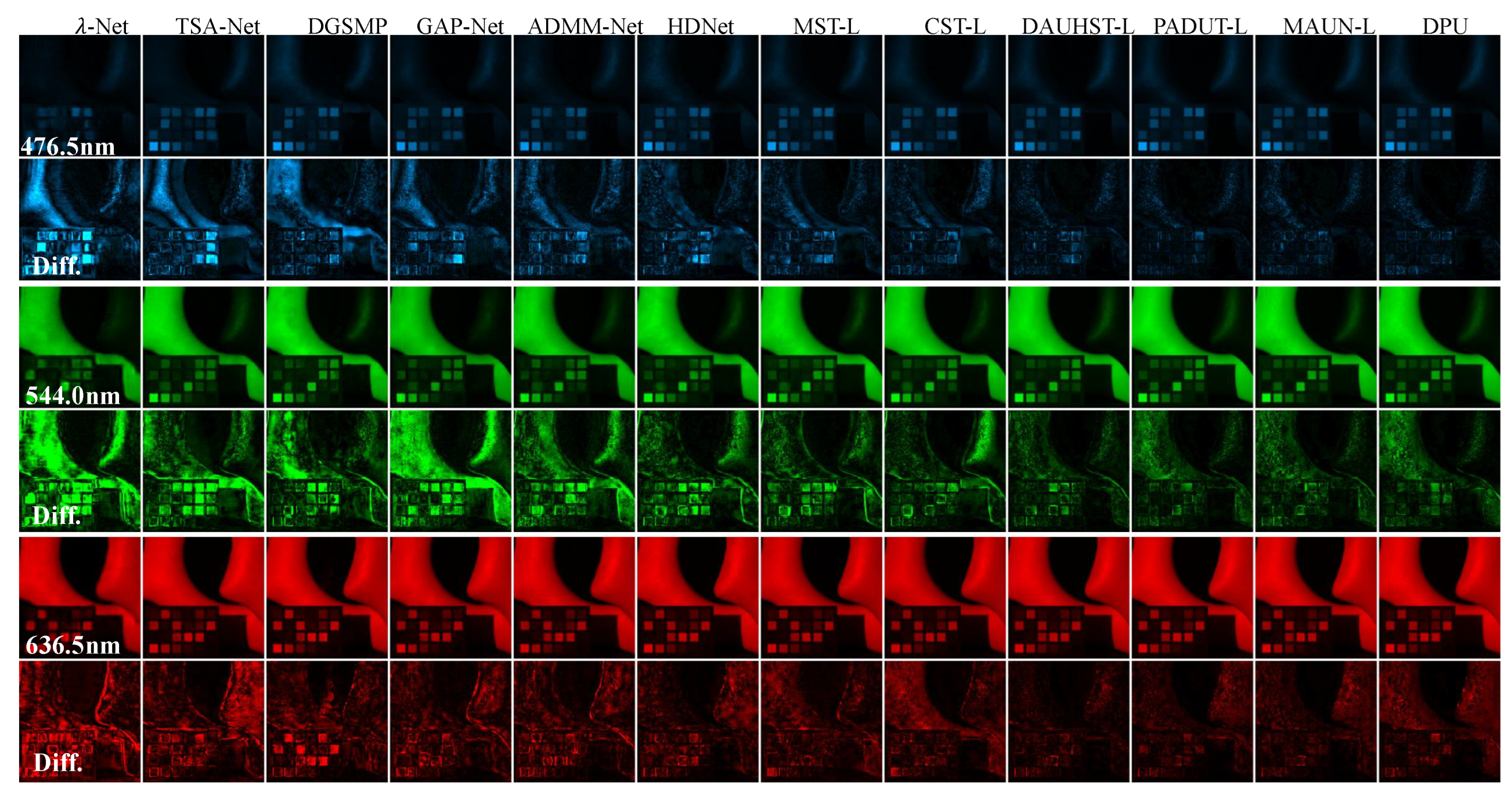

Figure 3 illuatrates the visualization comparison of 12 HS reconstruction mehods by evaluating three out of the 28 spectral channels from Scene 3 including the reconstructed images and the differences with the cprresponding ground-truth.

In 2023, the FPFA sensor [

17] has been introduced, and consequently, only a limited number of studies—such as MG-S2MLP [

55] and SPECAT [

54]—have investigated HS image reconstruction from snapshot measurements acquired using the FPFA setting. Both MG-S2MLP and SPECAT adopt an E2E learning paradigm, which enables the development of reconstruction models with significantly reduced parameter sizes and lower computational overhead.

Table 5(b) presents the comparative results across ten simulated scenes. Owing to the effective encoding mechanism employed by the 3D sensing mask, these E2E-based methods attain PSNR values comparable to those of the best-performing DUM-based method, SSR [

45], while achieving notably higher SSIM scores—despite their substantially lower computational demands.

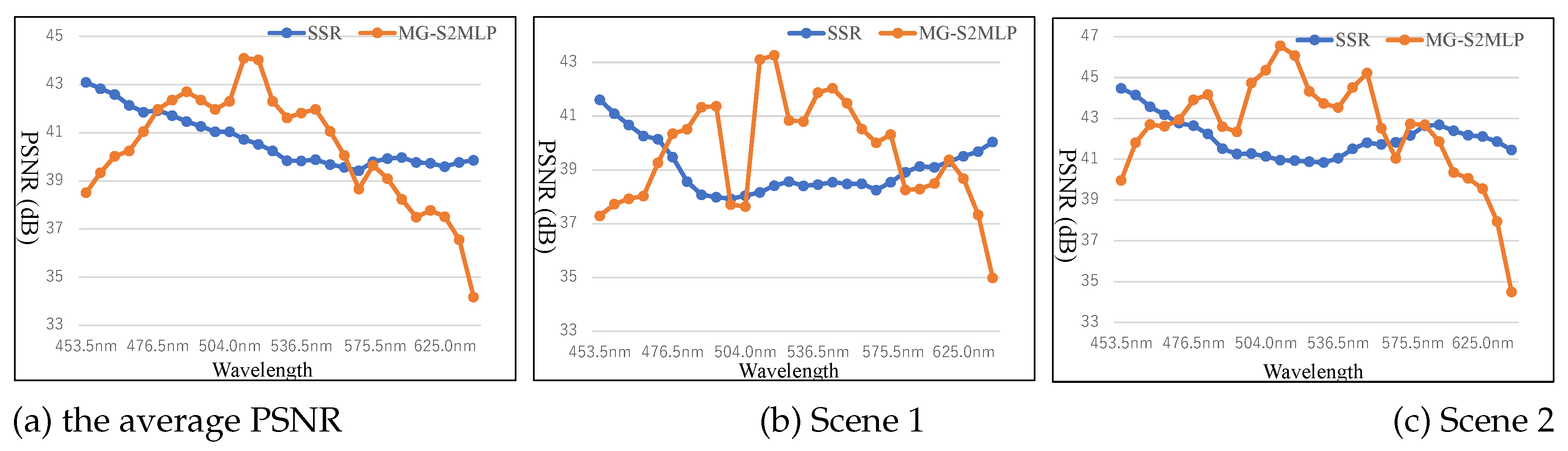

To examine the differences in reconstruction performance between the CASSI and FPFA sensing configurations, we compute the PSNR for each spectral band of the HS images reconstructed using the SSR and MG-S2MLP methods.

Figure 4 presents the average spectral-wise PSNR values obtained across 10 simulated scenes, as well as the individual results for Scene 1 and Scene 2. As shown in

Figure 4, the spectral-wise PSNR distributions reveal distinct reconstruction characteristics for the HS images obtained using SSR under the CASSI setting and MG-S2MLP under the FPFA setting. Specifically, the SSR method applied to CASSI measurements tends to yield higher PSNR values at the spectral extremes (i.e., the shorter and longer wavelengths), while the performance deteriorates in the middle spectral bands. In contrast, MG-S2MLP under the FPFA configuration demonstrates significantly higher PSNR values in the central spectral bands, with much lower performance at the spectral boundaries. Furthermore, the PSNR values obtained from MG-S2MLP reveal substantially greater variability across spectral bands compared to those from SSR, indicating a less uniform reconstruction performance. These observations underscore that the characteristics of the reconstructed HS images are intrinsically linked to the underlying measurement configurations. By systematically analyzing these spectral-wise reconstruction patterns, valuable insights can be gained into the nature and distribution of information captured during the measurement process, thereby informing the design of more effective and tailored imaging systems. In addition, the spectral-wise PSNR analysis offers guidance for enhancing reconstruction algorithms, enabling adaptive calibration strategies that account for band-specific reconstruction quality.

6. Challenges and Trends

Previously, we presented different categories of state-of-the-art (SoTA) hyperspectral image (HSI) reconstruction methods and compared their quantitative performance in terms of PSNR and SSIM. In summary, traditional model-based methods rely on handcrafted priors and optimization algorithms rooted in signal processing theory. These approaches typically offer high interpretability but often suffer from limited reconstruction performance. In contrast, End-to-End (E2E) deep learning methods focus on designing effective and efficient network architectures for modeling high-dimensional spatial and spectral correlations. These methods, particularly those based on Transformer architectures, generally outperform model-based approaches by a significant margin. Meanwhile, deep unfolding models integrate the advantages of both model-based and E2E methods, achieving further performance improvements by combining interpretability with data-driven learning. Despite the remarkable progress made by advanced reconstruction methods, many challenges remain for future development in this field. In the following, we discuss the existing challenges faced by current SoTA HS image reconstruction methods, along with potential solution trends aimed at addressing these limitations.

Spectral distortion:One of the key challenges inHS image reconstruction is spectral distortion, which refers to inaccuracies or artifacts introduced in the reconstructed spectral signatures of pixels. In HS data, each pixel contains a rich spectral profile that reflects the material composition of the scene. Preserving this spectral fidelity is crucial for downstream applications such as classification, target detection, and material identification. The SoTA HS reconstruction methods maily focus on designing effective network architectures to implicitly model spatial and spectral information. However, they often make limited explicit effort to preserve spectral fidelity. This can lead to several issues: 1) Altered or smoothed spectral curves, misrepresenting the true material signatures; 2) Reduced classification or detection performance, even if spatial metrics (e.g., PSNR, SSIM) are high; 3) Poor generalization, especially in real-world datasets with complex spectral variability.

For example, the SoTA learning-based methods generally concentrate more on minimizing pixel-wise loss functions without explicitly enforcing spectral integrity, and then the spectra-wise evalation metric may largly vary across different band illustrated in

Figure 4, indicating lower spectral fidelity. To mitigate spectral distortion and enhance the fidelity of reconstructed HS data, future research is expected to advance in the following directions: 1) Spectral-Aware Loss Functions such as incorporating such as spectral angle mapper (SAM), correlation-based losses, or perceptual spectral loss; 2) Spectral Attention and Context Modeling to dynamically focus on informative spectral bands and model inter-band dependencies; 3) Physics-Informed and Domain-Prior Integration to guide the learning process toward physically plausible reconstructions; 4) Adaptive and Band-Wise Modeling to handle spectral variations.

Computational efficiency:HS images contain dozens to hundreds of spectral bands per pixel, leading to significant memory consumption and computational load during the reconstruction process. Despite recent advancements, computational efficiency remains a major challenge. SoTA learning-based methods often rely on complex network architectures—such as deep CNNs or Transformers—that demand substantial computational resources, including high-end GPUs and long processing times. This challenge becomes even more critical when reconstruction algorithms are required to be deployed directly on resource-constrained imaging sensors, making the development of real-time and lightweight techniques increasingly important. These limitations manifest in several ways: 1) Limited real-time applicability in time-sensitive or on-board scenarios; 2) High training and inference costs, hindering scalability and deployment in low-resource environments; 3) Memory bottlenecks, particularly when processing large-scale or high-resolution scenes.

To enable practical and scalable deployment of HS image reconstruction methods, especially in real-time and resource-constrained scenarios, future research is expected to focus on several key trends: 1) Lightweight and Efficient Network Design, to reduce model complexity while maintaining reconstruction quality; 2) Spectral-Spatial decomposition, enabling separate modeling of spectral and spatial domains to lower computational overhead; 3) Model Compression and Acceleration, through techniques such as pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation to create compact, fast models; 4) Neural Architecture Search (NAS), for automatically discovering optimal architectures tailored to HSI reconstruction tasks; 5) Hardware-Aware Optimization, involving the co-design of algorithms and hardware (e.g., FPGA or edge AI chips) for efficient real-world deployment.

Generalization capabilty:the generalization problem—the ability of a model trained on specific datasets or imaging conditions to perform well across diverse scenes, sensors, or environmental settings, is a fundamental challenge in learning-based methods. Many SoTA learning-based methods achieve impressive results on curated benchmark datasets. However, their performance often degrades when applied to: 1) Unseen spectral distributions or different sensor characteristics; 2) Varied environmental conditions, such as lighting, noise, or atmospheric effects; 3) Complex real-world scenes with diverse materials and fine-grained textures.

The limited generalizability of current HS image reconstruction methods primarily stems from overfitting to training data and a lack of robust mechanisms to handle domain shifts. Moreover, models trained on synthetic or simulation-based data often struggle to capture the complexity and variability of real-world measurements, further widening the performance gap in practical applications. Improving generalization is therefore a critical step toward the reliable and scalable deployment of HSI reconstruction models in real-world scenarios. To enhance the robustness and adaptability of these models, future research may focus on the following directions: 1) Domain Adaptation and Generalization, including techniques such as unsupervised domain adaptation or meta-learning to adapt models to new domains without extensive retraining; 2) Physics-Guided and Model-Based Hybrid Learning, which incorporates physical priors or signal modeling to provide inductive bias and improve generalization across datasets; 3) Data Diversity and Augmentation, by building more comprehensive training datasets that span various scenes, sensors, and acquisition conditions, and applying advanced spectral-spatial augmentation strategies to simulate real-world variations; 4) Unsupervised and Self-Supervised Learning, which leverages inherent structures and priors in the captured measurements to learn more generalizable representations without relying on extensive labeled data.

7. Conclusion

In this survey, we have conducted a comprehensive and systematic review of recent advancements in HS image reconstruction from compressive measurements, particularly focusing on snapshot-based spectral compressive imaging systems. The reconstruction problem is fundamentally rooted in the mathematical modeling of the compressive sensing process, which establishes a relationship between the observed low-dimensional snapshot measurement and the high-dimensional latent HS. This formulation serves as the theoretical foundation for the design and development of diverse reconstruction algorithms. We categorize existing reconstruction methods into three main paradigms: model-based approaches, which rely on handcrafted priors and iterative optimization; end-to-end deep learning-based methods, which directly learn the mapping from measurements to reconstructed HS images; and deep unfolding-based approaches, which integrate the interpretability of model-based techniques with the learning capability of deep networks. For each category, we highlight representative methods and analyze their architectural designs, strengths, and limitations. Furthermore, we evaluate several state-of-the-art methods using two widely adopted benchmark datasets in the field. Through a comparative study of both quantitative results and qualitative reconstructions, we provide a consolidated perspective on the relative performance of each approach, offering practical guidance for selecting appropriate mechanisms in various HS image reconstruction scenarios.

Finally, we discuss key challenges that persist in the field, including spectral distortion, computational inefficiency, and limited generalization across diverse scenes and acquisition conditions. We also identify emerging research directions aimed at overcoming these limitations, such as the use of spectral-aware learning strategies, lightweight model design, domain adaptation, and physics-informed architectures. We hope that this survey serves as a valuable reference for researchers and practitioners, and inspires future innovations in hyperspectral image reconstruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, and visualization, X.-H. Han; writing—review and editing, X.-H. Han, J. Wang and H. Jiang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maggiori, E.; Charpiat, G.; Tarabalka, Y.; Alliez, P. Recurrent neural networks to correct satellite image classification maps. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2016, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Song, W.; Fang, L.; Chen, Y.; Ghamisi, P.; Benediktsson, J.A. Deep learning for hyperspectral image classification: An overview. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 6690–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanachi, R.; Sellami, A.; Farah, I.R.; Mura, M.D. Multi-view graph representation learning for hyperspectral image classification with spectral–spatial graph neural networks. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 3737–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borengasser, M.; Hungate, W.S.; Watkins, R. Hyperspectral remote sensing: principles and applications. CRC press 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Melgani, F.; Bruzzone, L. Classification of hyperspectral remote sensing images with support vector machines. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensin 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.; Rock, B. Imaging spectrometry for earth remote sensing. Science 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Zheng, M.; Zheng, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wei, W. Integrating prototype learning with graph convolution network for effective active hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, L.; Zhang, D.; qi Yan, J.; Li, Q.L.; lin Tang, Q. Classification of hyperspectral medical tongue images for tongue diagnosis. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2007, 31, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, B. Hyperspectral imaging in medical applications. In Data Handling in Science and Technology 2019, 32, 523–565. [Google Scholar]

- Llull, P.; Liao, X.; Yuan, X.; Yang, J.; Kittle, D.; Carin, L.; Sapiro, G.; Brady, D.J. Coded aperture compressive temporal imaging. Optics Express 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagadarikar, A.; John, R.; Willett, R.; Brady, D. Single disperser design for coded aperture snapshot spectral imaging. Applied Optics 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagadarikar, A.A.; Pitsianis, N.P.; Sun, X.; Brady, D.J. Video rate spectral imaging using a coded aperture snapshot spectral imager. Optics Express 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Yue, T.; Lin, X.; Lin, S.; Yuan, X.; Dai, Q.; Carin, L.; Brady, D.J. Computational snapshot multispectral cameras: Toward dynamic capture of the spectral world. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehm, M.E.; John, R.; Brady, D.J.; Willett, R.M.; Schulz, T.J. Single-shot compressive spectral imaging with a dual-disperser architecture. Optics express 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arce, G.R.; Brady, D.J.; Carin, L.; Arguello, H.; Kittle, D.S. Compressive coded aperture spectral imaging: An introduction,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2013, 31, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Z.; Gao, D.; Shi, G.; Zeng, W.; Wu, F. High-speed hyperspectral video acquisition with a dual-camera architectur. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2015, pp. 4942––4950.

- Motoki, Y.; Yoshikazu, Y.; Takayuki, K. Video-rate hyperspectral camera based on a cmoscompatible random array of fabry–pe´rot filters. Nature Photonics 2023, 17, 218–223. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Suo, J.; Brady, D.J.; Dai, Q. Rank minimization for snapshot compressive imaging. TPAMI 2018, 41, 2990–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Z.; Shi, G.; Wu, F.; Zeng, W. Adaptive nonlocal sparse representation for dual-camera compressive hyperspectral imaging. TPAMI 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Yao, Q.; Li, C.; Yokoya, N.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. Non-local meets global: An iterative paradigm for hyperspectral image restoration. TPAMI 2020, 44, 2089–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X. Generalized alternating projection based total variation minimization for compressive sensing. ICIP 2016, pp. 2539–2543.

- Figueiredo, M.A.; Nowak, R.D.; Wright, S.J. Gradient projection for sparse reconstruction: Application to compressed sensing and other inverse problems. IEEE Journal of selected topics in signal processing 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Ma, J.; Yuan, X. End-to-end low cost compressive spectral imaging with spatial-spectral self attention. ECCV 2020, pp. 187–204.

- Hu, X.; Cai, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Timofte, R.; Gool, L.V. Hdnet: High-resolution dual-domain learning for spectral compressive imaging. CVPR 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Yuan, X.; Pu, Y.; Athitsos, V. λ-net: Reconstruct hyperspectral images from a snapshot measurement. ICCV 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Sun, C.; Fu, Y.; Kim, M.H.; Huang, H. Hyperspectral image reconstruction using a deep spatial-spectral prior. CVPR 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, R.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J. Herosnet: Hyperspectral explicable reconstruction and optimal sampling deep network for snapshot compressive imaging. CVPR 2022, pp. 17532–17541.

- Takabe, T.; Han, X.; Chen, Y. Deep Versatile Hyperspectral Reconstruction Model from A Snapshot Measurement with Arbitrary Masks. ICASSP 2024, pp. 2390–2394.

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y. Hyperspectral Image Reconstruction Using Hierarchical Neural Architecture Search from A Snapshot Image. ICASSP 2024, pp. 2500–2504.

- Wang, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, M.; Fu, Y.; Huang, H. Dnu: Deep non-local unrolling for computational spectral imaging. CVPR 2022, pp. 1661–1671.

- Huang, T.; Dong, W.; Yuan, X.; Wu, J.; Shi., G. Deep gaussian scale mixture prior for spectral compressive imaging. CVPR 2021, pp. 16216––16225.

- Cai, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y.; Timofte, R.; Gool, L.V. Degradation-aware unfolding half-shuffle transformer for spectral compressive imaging. NeurIPS 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Fu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Pixel adaptive deep unfolding transformer for hyperspectral image reconstruction. ICCV 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Donoho, D.L. Compressed sensing. IEEE Transactions on information theory 2006, 52, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descour, M.; Volin, C.; Ford, B.; Dereniak, E.; Maker, P.; Wilson, D. Snapshot hyperspectral imaging. Integrated computational imaging systems, Optica Publishing Group 2001.

- Han, W.; Wang, Q.; Cai, W. Computed tomography imaging spectrometry based on superiorization and guided image filtering. Optics Letter 2021, 46, 2208–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Wang, Z. et al. Y.Z. A broadband hyperspectral image sensor with high spatio-temporal resolution. Nature 2024, 635, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Fu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Huang, H. Computational hyperspectral imaging based on dimension-discriminative low-rank tensor recovery. ICCV 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Lin, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Timofte, R.; Gool, L.V. Mask-guided spectral-wise transformer for efficient hyperspectral image reconstruction. CVPR 2022, pp. 17502–17511.

- Cai, Y.; Lin, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Timofte, R.; Gool, L.V. Coarse-to-fine sparse transformer for hyperspectral image reconstruction. ECCV 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Liu, Y.; Suo, J.; Dai, Q. Plug-and-play algorithms for large-scale snapshot compressive imaging. CVPR 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Z.; Qiao, M.; Tong, Z.; Yang, X.; Han, S.; Yuan, X. Deep plug-and-play priors for spectral snapshot compressive imaging. Photonics Research 2021, 9, B18–B29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ma, J.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, J.; Yuan, Y. MAUN: Memory-Augmented Deep Unfolding Network for Hyperspectral Image Reconstruction. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2024, 11, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; Cao, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhao, Y.P. Dual Prior Unfolding for Snapshot Compressive Imaging. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2024, pp. 25742–25752.

- Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhao, Y.P. Improving Spectral Snapshot Reconstruction with Spectral-Spatial Rectification. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2024, pp. 25817–25826.

- Zhang, S.; Dong, Y.; Fu, H.; Huang, S.L.; Zhan, L. A spectral reconstruction algorithm of miniature spectrometer based on sparse optimization and dictionary learning. Sensors 2018, 18, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Figueiredo, M.A. A new twist: Two-step iterative shrinkage/thresholding algorithms for image restoration. TIP 2007, 16, 2992–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eason, D.T.; Andrews, M. Total variation regularization via continuation to recover compressed hyperspectral images. IEEE Transaction on Image Processing 2014, 24, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Sato, I.; Sato, Y. Exploiting spectral-spatial correlation for coded hyperspectral image restoration. CVPR 2016, pp. 3727–3766.

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Fu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Huang, H. Computational hyperspectral imaging based on dimension-discriminative low-rank tensor recovery. ICCV 2019, pp. 10183–10192.

- Ma, J.; Liu, X.; Shou, Z.; Yuan, X. Deep tensor admm-net for snapshot compressive imaging. ICCV 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yorimoto, K.; Han, X.H. HyperMixNet: Hyperspectral Image Reconstruction with Deep Mixed Network From a Snapshot Measurement. ICCVW 2021, pp. 1184–1193.

- Meng, Z.; Jalali, S.; Yuan, X. Gap-net for snapshot compressive imaging. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.08364 2020.

- Yao, Z.; Liu, S.; Yuan, X.; Fang, L. SPECAT: SPatial-spEctral Cumulative-Attention Transformer for High-Resolution Hyperspectral Image Reconstruction. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2024.

- Han, X.H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.W. Mask-Guided Spatial–Spectral MLP Network for High-Resolution Hyperspectral Image Reconstruction. Sensors 2024, 24, 7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Binarized Spectral Compressive Imaging. The 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing System 2023, pp. 38335–38346.