1. Introduction

Protein aggregation disorders are characterized by the misfolding of native proteins, leading to their pathological accumulation. A subset of these proteins adopts β-pleated sheet–rich conformations upon misfolding, forming amyloid aggregates—a hallmark of a group of disorders collectively termed amyloidosis [

1,

2]. In the context of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), islet amyloid deposits represent a prominent pathological feature, found in over 90% of affected individuals upon postmortem histopathological examination [

3,

4,

5]. A strong correlation has been established between amylin aggregation and the progressive loss of pancreatic β-cell mass. In cases where substantial islet amyloid deposition is observed, there is often a concurrent increase in β-cell apoptosis [

5].

Amylin, also known as islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), is a 37-amino acid peptide hormone and the principal constituent of islet amyloid deposits in T2DM [

6]. It is co-localized with insulin in the secretory granules of pancreatic β-cells and is co-secreted with insulin in response to β-cell stimulation [

3]. Physiologically, amylin plays essential roles in glucose homeostasis by regulating gastric emptying, promoting satiety, suppressing glucagon secretion from pancreatic α-cells, and modulating insulin output [

3,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In healthy individuals, insulin and mature amylin are secreted at a molar ratio of approximately 100: 1 (insulin: amylin). In T2DM, chronic hyperinsulinemia is typically accompanied by elevated plasma levels of amylin [

3].

Beyond concentration, several factors influence the amyloidogenic potential of amylin, including the cellular microenvironment, proteostatic imbalance, oxidative stress, and genetic mutations. Among these, pH fluctuations have emerged as key modulators of amylin aggregation. Specifically, aggregation is more favorable at slightly basic pH compared to acidic conditions [

10]. This observation aligns with the physiological transition that occurs when amylin is secreted from the acidic milieu of pancreatic secretory granules (pH ~5.5) into the extracellular space (pH ~7.4), potentially impairing its degradation and promoting deposition as islet amyloid [

7].

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has established a robust association between metabolic syndrome and late-onset dementias [15–18]. Notably, individuals with T2DM are estimated to have a two- to five-fold increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias compared to non-diabetic individuals [

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, AD-associated neuropathologies—including extracellular Aβ plaques—may exacerbate cerebral insulin resistance, suggesting the presence of a bidirectional feedback loop in which amyloid accumulation and insulin signaling deficits reinforce one another.[

15,

16,

17]. This interplay may contribute to progressive neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

In this review, we examine the potential role of pancreatic peptide amylin (IAPP) as a molecular bridge between metabolic dysregulation and neurodegeneration. Specifically, we explore how amylin-induced proteostatic stress might link pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in T2DM with the pathophysiological features of AD and related dementias.

2. Methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Google Scholar using the terms “Islet Amyloid Polypeptide,” “Alzheimer’s disease,” “amyloid-β peptides,” “vascular dementia,” “arteriosclerotic dementia,” “metabolic syndrome,” “type 2 diabetes mellitus,” “dementia,” “proteostasis dysfunction,” and “heat shock proteins.” The search was limited to English-language articles published in the last ten years.

Our primary focus was on studies related to the molecular mechanisms underlying diabetes-associated dementia, with particular emphasis on human amylin, its regulation, and proteostasis. We also reviewed reference lists of relevant articles to identify additional studies. Inclusion criteria emphasized research directly linking diabetes or metabolic syndrome with dementia, where amylin played a significant role in proteostasis or aggregate-prone protein pathology. Studies not in English or not relevant to the topic (based on MeSH terms and keywords) were excluded.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Molecular Insights into Amylin Aggregation and Proteostasis Impairment

IAPP from various mammals shows differing aggregation propensities. Human IAPP (hIAPP) is prone to form β-sheet fibrils (similar in structure to Aβ), whereas rodent IAPP (rIAPP) carries proline substitutions at key positions and does not form amyloid fibrils[

18,

19,

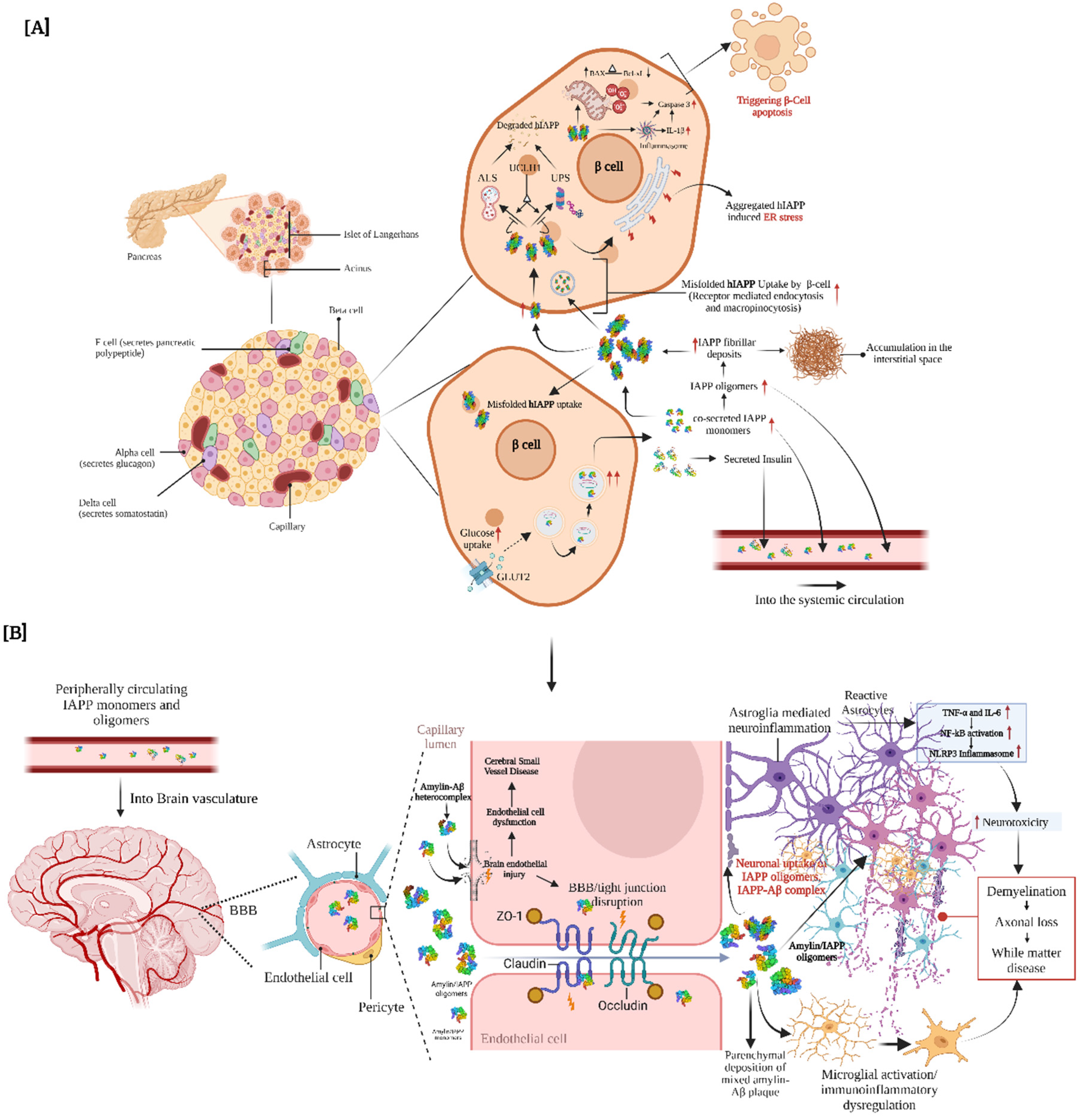

20]. hIAPP aggregates accumulate mainly extracellularly, though small amounts have been reported intracellularly in β-cells [42,44]. Emerging evidence indicates that human amylin exerts cytotoxic effects on β-cells, ranging from membrane disruption and reactive oxygen species production to induction of apoptosis and inflammasome activation. However, the precise cellular pathways mediating amylin toxicity remain to be fully elucidated [45]. Proposed mechanisms include endoplasmic reticulum stress and downstream impairment of protein quality control systems such as the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy-lysosome system (ALS) (

Figure 1A). In recent years, attention has shifted toward oligomeric IAPP species, which are suspected to be more toxic than mature fibrils [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Studies on IAPP clearance by the UPS have yielded mixed results. Casas et al. [

27]. reported that extracellular hIAPP exposure reduced proteasomal activity more than rIAPP in a murine insulinoma cell line. Moreover, hIAPP aggregation was associated with ER stress, whereas non-amyloidogenic rIAPP did not form aggregates and is often used as a control in proteostasis studies. However, other experiments found that adenoviral overexpression of hIAPP or rIAPP in cells increased proteasomal activity, and isolated pancreatic islets from transgenic rats showed no significant difference in proteasome function between hIAPP and rIAPP conditions. These findings suggest that IAPP does not invariably target UPS pathways and that alternate clearance mechanisms may compensate in some contexts. (

Figure 1A).

3.2. hIAPP-Mediated Proteotoxic Stress: Impact on Ubiquitin-Proteasome and Autophagy-Lysosome Systems

Microarray studies have shown that treating β-cells with hIAPP can downregulate key chaperones, including cytosolic Hsp90AA1/AB1 and ER chaperone Hsp90B1[

27]. Hsp90 is a chaperone that assists in 26S proteasome assembly and prevents oxidative inactivation of the 20S proteasome[

31,

32]. Thus, reduced Hsp90 levels could contribute to decreased proteasomal activity. Indeed, hIAPP-treated mouse insulinoma (MIN6) cells, hIAPP transgenic rats, and hIAPP-transduced INS 832/13 insulinoma cells all showed an accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins compared to controls with rIAPP [

27,

33]. In contrast, another β-cell line, RIN-m5F, did not show a marked increase in ubiquitinated proteins upon hIAPP treatment [

34]. Notably, patients with type 2 diabetes have significantly lower levels of the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH-L1, along with decreased proteasome activity, resulting in intracellular buildup of ubiquitinated proteins [

33]. This finding raises the question of whether hIAPP is degraded predominantly by the 20S proteasome (in a ubiquitin-independent manner) or also via the ubiquitin-dependent 26S proteasome.

In vitro studies indicate that ubiquitination of IAPP is not required for 20S proteasomal recognition. However, immunofluorescence studies show strong co-localization of hIAPP with ubiquitin in hIAPP-treated cells and human islets, and intracellular hIAPP can itself be ubiquitinated [

34]. Furthermore, hIAPP co-precipitated with components of the 26S proteasome (such as the 19S subunit Rpn8 and the 20S subunit PSMA4) and co-localized with chaperones Hsp70 and Hsp90 [

34]. These results suggest that a ubiquitin-dependent pathway may also be involved in clearing hIAPP. Consistently, proteasomes can degrade hIAPP under both aggregation-prone and aggregation-inhibiting conditions, implying that hIAPP does not need to form aggregates to be targeted by the proteasome [

34,

35].

Autophagy is another crucial route for protein quality control. One of the earliest studies linking IAPP and autophagy showed that transfecting COS-1 cells (which lack endogenous IAPP) with hIAPP led to enhanced autophagosome formation compared to rIAPP transfection [

36]. Similarly, hIAPP-treated INS-1 cells, hIAPP-transduced INS-1 cells, and islet β-cells in transgenic rats and mice all exhibited increased autophagosome accumulation relative to rIAPP controls [

37,

38]. Rivera

et al. [

37] further noted that even rIAPP-transduced INS 832/13 cells had more autophagosomes than non-transduced cells, though far fewer than hIAPP-transduced cells. It remains unclear whether the observed autophagosome increase reflects an overall rise in autophagic flux or a backlog due to impaired lysosomal degradation.

To clarify autophagy’s role in degrading toxic hIAPP, researchers have used pharmacological and genetic modulators. Inhibition of lysosomal proteases with pepstatin A markedly increased hIAPP-induced apoptosis in β-cells, accompanied by higher intracellular IAPP content in INS 832/13 cells and human islets [

35,

37]. Similarly, Atg7 knockout (autophagy-deficient) cells showed greater hIAPP-induced apoptosis than rIAPP-treated cells [

35,

37,

38]. Conversely, stimulating autophagy with rapamycin (an mTOR inhibitor) significantly reduced hIAPP-induced apoptosis and lowered intracellular IAPP levels. These changes were not due to altered IAPP expression or secretion, and insulin content was unaffected, indicating that autophagy actively regulates IAPP turnover. Indeed, rapamycin-induced autophagy appears to protect β-cells by facilitating IAPP clearance. Rivera et al.[

37] reported that hIAPP becomes polyubiquitinated in cells, potentially targeting it for p62-mediated autophagy. Ubiquitination could also mark proteins for 26S proteasomal degradation, so both pathways may converge on clearing IAPP aggregates.

Different pathways may handle intracellular vs. extracellular IAPP. In one study, exogenous hIAPP or rIAPP was added to RIN-m5F cell cultures to model the uptake of circulating amylin. After uptake, IAPP localized predominantly to the nucleus, with very little co-localizing to lysosomes [

34]. In this context, inhibiting autophagy with pepstatin A did not significantly change intracellular IAPP levels [

34]. These observations underscore that cells employ multiple clearance mechanisms for IAPP, and the predominant pathway may depend on how and where the protein is encountered.

Collectively, these findings highlight the complex proteostatic stress caused by misfolded amylin. Early protein aggregation could potentially serve as a biomarker for the progression of diabetes or the onset of diabetes-associated cognitive impairment. Disruption of either proteasomal or autophagic pathways can exacerbate amylin toxicity, suggesting that maintaining all arms of the protein quality control network is critical to mitigate disease (

Figure 1A).

3.3. hIAPP Accumulation in the Neurovascular System: A Possible Origin of Metabolic Dementia

Emerging imaging and biomarker studies in humans are shedding light on how T2DM and insulin resistance may influence neurodegeneration. Here, we consider key mechanisms connecting T2DM and AD as suggested by in vitro and in vivo studies (

Figure 1B).

Multiple clinical and animal studies suggest that pancreatic amyloid (amylin) may mediate neuronal injury in AD, implicating amylin as a potential link between T2DM and dementia [

39,

40,

41]. For instance, Fawver et al. [

41] identified amylin in the cerebrospinal fluid and brains of patients with AD or vascular dementia, including individuals without diabetes. Postmortem analyses revealed co-localized deposits of amylin and Aβ in brain tissue from diabetic patients with vascular dementia or AD, as well as in non-diabetic AD patients [

40,

41]. Jackson et al. [

40] reported that patients with chronic T2DM exhibited amylin deposits in the temporal lobe gray matter, often co-depositing with Aβ. Strikingly, significant amylin deposition was also found in cerebral blood vessels and parenchyma of patients with late-onset AD who had no clinical history of diabetes [

40]. These findings suggest that amylin can traverse the blood-brain barrier and exacerbate amyloid pathology in the brain.

Animal models strongly support amylin’s neurodegenerative role. Transgenic rats overexpressing pancreatic amylin develop progressive neurological deficits associated with extensive amylin accumulation in the brain [

42]. Compared to wild-type rats, these amylin-overexpressing rats showed large amylin deposits (>50 μm) and elevated oligomeric amylin levels in the brain. More recently, Oskarsson et al. [

39] demonstrated that intravenous injection of preformed amylin fibrils (and Aβ fibrils) into transgenic mice expressing human amylin induced amyloid deposition in both the pancreas and the brain. This

in vivo “cross-seeding” supports the idea of a molecular link between peripheral amylin and cerebral amyloid.

3.4. Biophysical Links Between Pancreatic Amylin and Cerebral Amyloid-β

Multiple lines of evidence suggest mechanistic connections between pancreatic and cerebral amyloids, specifically amylin and Aβ. Amylin shares several biophysical and physiological properties with Aβ. Despite little sequence homology, the two peptides are similar in size and adopt comparable β-sheet secondary structures [

43].

Experiments indicate that amylin can directly interact with Aβ, potentially seeding Aβ aggregation [

41]. It has been hypothesized that amylin modulates Aβ conformation and aggregation, forming stable amylin–Aβ heterocomplexes [

41,

44,

45,

46]. Whether these heterocomplexes have altered structures that confer greater toxicity remains to be determined.

Aging is accompanied by an increased accumulation of amyloidogenic proteins and a decline in proteolytic clearance via autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome pathways. The long-term health of cells—especially terminally differentiated neurons—relies on robust protein quality control. Extensive research over the past few decades has linked amyloid aggregates to a variety of cellular dysfunctions, including mitochondrial impairment [

47,

48,

49,

50], oxidative stress [

47,

51], aberrant receptor-mediated signaling [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56], disruption Ca

2+ mediated homeostasis [

57,

58], membrane destabilization [

59,

60], and microglial activation [

61]. Fibrillar amyloid plaques are pathological hallmarks of both AD and T2DM, often accompanied by cellular injury and inflammation. Interestingly, amyloid plaque burden correlates poorly with clinical symptoms; instead, smaller soluble oligomers are now thought to be the primary toxic species driving disease progression [

62]. Across various amyloidoses (including Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, and prion diseases), soluble protein oligomers are better predictors of cell death and dysfunction than insoluble fibrils [

63,

64]. Notably, oligomeric and fibrillar aggregates may form via distinct mechanisms influenced by external cofactors (binding partners such as other proteins, metals, and lipids, among others) [

65,

66].

The neurotoxicity of amylin has not been as extensively characterized as that of Aβ. Nonetheless, like Aβ, human amylin is neurotoxic to cultured neurons in a dose-dependent manner, whereas non-amyloidogenic rodent amylin lacks such toxicity [

67]. Furthermore, both amylin and Aβ induce mitochondrial dysfunction: they reduce the activity of electron transport chain complex IV, impair cellular respiration, and increase reactive oxygen species generation [

68]. It remains to be seen whether oligomeric vs. fibrillar forms of amylin and Aβ differ in their toxic effects on neurons. However, current evidence suggests these peptides may converge on common pathways—such as mitochondrial injury and oxidative stress—to induce neurodegeneration. Further comparative studies are needed to fully elucidate these shared mechanisms of toxicity (

Figure 2).

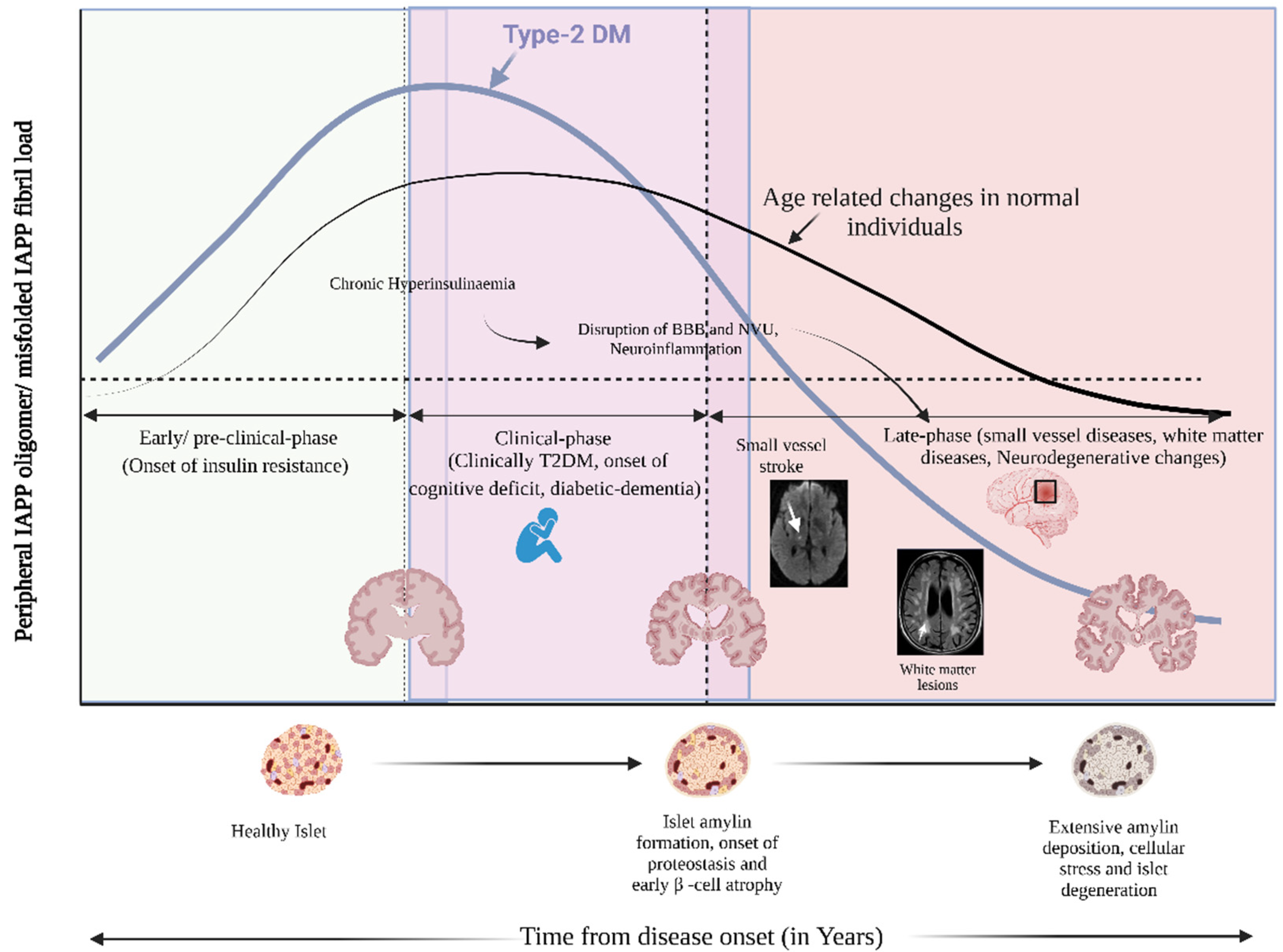

Early Preclinical Phase (Onset of Insulin Resistance): Chronic hyperinsulinemia drives excessive hIAPP secretion, leading to early islet amyloid formation before the onset of clinical diabetes. As β-cell stress intensifies, proteostatic imbalances result in intra- and extracellular hIAPP accumulation, promoting inflammation and cellular degeneration.

Clinical Phase (Overt T2DM, Onset of Cognitive Deficits, and Diabetic Dementia): Circulating hIAPP aggregates compromise the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and disrupt the neurovascular unit (NVU), contributing to neuroinflammation and cerebral small vessel pathology.

Late Phase (Small Vessel Disease, White Matter Lesions, and Neurodegenerative Changes): This cascade progresses to cerebral small vessel disease, white matter lesions, and advanced neurodegeneration, including diabetic dementia.

The bold blue curve represents the hIAPP oligomer and fibril burden over time in individuals with T2DM, peaking during the clinical phase and persisting into late-stage disease. In contrast, the thinner black curve illustrates the age-related amyloid burden in non-diabetic individuals, which remains relatively low. Cross-sections of pancreatic islets and brain tissue depict the sequential pathological transitions from healthy states to advanced β-cell damage and neurovascular injury, highlighting the interplay between peripheral metabolic dysfunction and central neurodegeneration.

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Amylin is a peptide hormone positioned at the crossroads of metabolic disease and neurodegeneration. Our review highlights that while amylin serves important physiological functions, its misfolding and aggregation can be highly deleterious—causing β-cell loss in the pancreas and potentially contributing to neuronal injury in the brain. Evidence of amylin deposition in the brain and cerebral vasculature suggests a mechanistic link between peripheral metabolic dysfunction (diabetes) and central neuropathology (AD and related dementias), possibly mediated by common proteostatic disturbances.

We explored amylin’s cellular proteostasis in terms of its synthesis, aggregation, degradation, and clearance. Amylin aggregation imposes harmful effects that engage both major protein quality control systems: the UPS and ALS. Disruption of molecular chaperones or either clearance pathway exacerbates amylin’s proteotoxicity, underscoring the need for all components of the proteostasis network to function in concert to prevent aggregation-related damage. We also discussed the influence of amylin on neurodegeneration—particularly how amylin deposition and interaction with Aβ may contribute to cerebrovascular pathology and cognitive decline.

However, a direct causal relationship between amylin pathology and neurodegeneration has yet to be fully established. In the future, studies should aim to clarify how amylin, Aβ, and other amyloidogenic proteins interact within the brain and how chaperones and degradation systems (UPS/ALS) modulate these interactions. Identifying key intervention points in these pathways could yield biomarkers to predict which diabetic patients are at risk for cognitive decline and could reveal novel therapeutic targets. For example, enhancing amylin clearance or stabilizing proteostasis may prove beneficial in mitigating “diabetic dementia” (

Figure 2).

Given the projected rise in both diabetes and dementia incidence due to aging populations and lifestyle factors, there is an urgent need to fill these knowledge gaps. Targeting components of the proteostasis network (such as specific chaperones or autophagy/lysosomal regulators) and monitoring protein aggregation biomarkers might enable early intervention before irreversible neurodegeneration occurs. In summary, maintaining a healthy balance of amylin production, folding, and clearance is crucial. Future research and therapeutic efforts focused on regulating amylin levels and aggregation could play a vital role in combating the intertwined epidemics of diabetes and dementia.

Author Contributions

All authors fulfilled the authorship requirements outlined by the International Journal of Molecular Sciences (IJMS), have contributed substantially to the conception, drafting, and revision of the manuscript, and have approved its final version.

Acknowledgments

Julián Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NINDS #R01 NS39422 and R01 NS094607) and the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant TED2021-130174B-C33 and NETremor and grant PID2022-138585OB-C33, Resonate).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

References

- Aguzzi, A.; O'Connor, T. Protein aggregation diseases: pathogenicity and therapeutic perspectives. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2010, 9, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisele, Y.S.; Monteiro, C.; Fearns, C.; Encalada, S.E.; Wiseman, R.L.; Powers, E.T.; Kelly, J.W. Targeting protein aggregation for the treatment of degenerative diseases. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2015, 14, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzban, L.; Park, K.; Verchere, C.B. Islet amyloid polypeptide and type 2 diabetes. Experimental gerontology 2003, 38, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanke, T.; Bell, G.I.; Sample, C.; Rubenstein, A.H.; Steiner, D.F. An islet amyloid peptide is derived from an 89-amino acid precursor by proteolytic processing. The Journal of biological chemistry 1988, 263, 17243–17246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurgens, C.A.; Toukatly, M.N.; Fligner, C.L.; Udayasankar, J.; Subramanian, S.L.; Zraika, S.; Aston-Mourney, K.; Carr, D.B.; Westermark, P.; Westermark, G.T.; et al. β-cell loss and β-cell apoptosis in human type 2 diabetes are related to islet amyloid deposition. The American journal of pathology 2011, 178, 2632–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.N.; Leighton, B.; Todd, J.A.; Cockburn, D.; Schofield, P.N.; Sutton, R.; Holt, S.; Boyd, Y.; Day, A.J.; Foot, E.A.; et al. Molecular and functional characterization of amylin, a peptide associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1989, 86, 9662–9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, A.; Schmidt, A.M. Mechanisms of islet amyloidosis toxicity in type 2 diabetes. FEBS letters 2013, 587, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Morales-Scheihing, D.; Butler, P.C.; Soto, C. Type 2 diabetes as a protein misfolding disease. Trends in molecular medicine 2015, 21, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, R.; Cao, P.; Noor, H.; Ridgway, Z.; Tu, L.H.; Wang, H.; Wong, A.G.; Zhang, X.; Abedini, A.; Schmidt, A.M.; et al. Islet Amyloid Polypeptide: Structure, Function, and Pathophysiology. Journal of diabetes research 2016, 2016, 2798269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.R.; An, S.S. Causative factors for formation of toxic islet amyloid polypeptide oligomer in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clinical interventions in aging 2015, 10, 1873–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillon, L.; Hoffmann, A.R.; Botz, A.; Khemtemourian, L. Molecular Structure, Membrane Interactions, and Toxicity of the Islet Amyloid Polypeptide in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of diabetes research 2016, 2016, 5639875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, A.; Stolk, R.P.; Hofman, A.; van Harskamp, F.; Grobbee, D.E.; Breteler, M.M. Association of diabetes mellitus and dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Diabetologia 1996, 39, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hölscher, C. Common pathological processes in Alzheimer disease and type 2 diabetes: a review. Brain research reviews 2007, 56, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Di Domenico, F.; Barone, E. Elevated risk of type 2 diabetes for development of Alzheimer disease: a key role for oxidative stress in brain. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2014, 1842, 1693–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, R.; Deb, S.; Chowdhury, D.; Sarkar, S.; Guha Roy, A.; Shome, G.; Sarkar, V.; Lahiri, D.; Benito-León, J. Neurometabolic substrate transport across brain barriers in diabetes mellitus: Implications for cognitive function and neurovascular health. Neuroscience letters 2024, 843, 138028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Monte, S.M. Contributions of brain insulin resistance and deficiency in amyloid-related neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs 2012, 72, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Monte, S.M.; Tong, M. Brain metabolic dysfunction at the core of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemical pharmacology 2014, 88, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.H.; O'Brien, T.D.; Betsholtz, C.; Westermark, P. Islet amyloid polypeptide: mechanisms of amyloidogenesis in the pancreatic islets and potential roles in diabetes mellitus. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 1992, 66, 522–535. [Google Scholar]

- Jaikaran, E.T.; Higham, C.E.; Serpell, L.C.; Zurdo, J.; Gross, M.; Clark, A.; Fraser, P.E. Identification of a novel human islet amyloid polypeptide beta-sheet domain and factors influencing fibrillogenesis. Journal of molecular biology 2001, 308, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermark, P.; Engström, U.; Johnson, K.H.; Westermark, G.T.; Betsholtz, C. Islet amyloid polypeptide: pinpointing amino acid residues linked to amyloid fibril formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1990, 87, 5036–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.F. Membrane permeabilization by Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. Chemistry and physics of lipids 2009, 160, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, J.; Ashley, R.H.; Harrison, D.; McIntyre, S.; Butler, P.C. The mechanism of islet amyloid polypeptide toxicity is membrane disruption by intermediate-sized toxic amyloid particles. Diabetes 1999, 48, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P. Neuroprotective signaling and the aging brain: take away my food and let me run. Brain research 2000, 886, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, D. Serpins inhibit the toxicity of amyloid peptides. The European journal of neuroscience 1997, 9, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Cooper, G.J. Fas-associated death receptor signaling evoked by human amylin in islet beta-cells. Diabetes 2008, 57, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, P. [Community investigation of the activities of daily living (ADL) and medical conditions of the elderly in Shanghai]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi 1998, 78, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, S.; Gomis, R.; Gribble, F.M.; Altirriba, J.; Knuutila, S.; Novials, A. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is a downstream endoplasmic reticulum stress response induced by extracellular human islet amyloid polypeptide and contributes to pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2284–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, S.L.; O'Neill, L.A. Disease-associated amyloid and misfolded protein aggregates activate the inflammasome. Trends in molecular medicine 2011, 17, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.; Straub, J.; Thirumalai, D. Sequence and crowding effects in the aggregation of a 10-residue fragment derived from islet amyloid polypeptide. Biophysical journal 2009, 96, 4552–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguiano, M.; Nowak, R.J.; Lansbury, P.T., Jr. Protofibrillar islet amyloid polypeptide permeabilizes synthetic vesicles by a pore-like mechanism that may be relevant to type II diabetes. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 11338–11343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, J.; Maruya, M.; Yashiroda, H.; Yahara, I.; Tanaka, K. The molecular chaperone Hsp90 plays a role in the assembly and maintenance of the 26S proteasome. The EMBO journal 2003, 22, 3557–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONCONI, M.; PETROPOULOS, I.; EMOD, I.; TURLIN, E.; BIVILLE, F.; FRIGUET, B. Protection from oxidative inactivation of the 20S proteasome byheat-shock protein 90. Biochemical Journal 1998, 333, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costes, S.; Huang, C.-j.; Gurlo, T.; Daval, M.; Matveyenko, A.V.; Rizza, R.A.; Butler, A.E.; Butler, P.C. β-Cell Dysfunctional ERAD/Ubiquitin/Proteasome System in Type 2 Diabetes Mediated by Islet Amyloid Polypeptide–Induced UCH-L1 Deficiency. Diabetes 2010, 60, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Trikha, S.; Sarkar, A.; Jeremic, A.M. Proteasome regulates turnover of toxic human amylin in pancreatic cells. The Biochemical journal 2016, 473, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.F.; Costes, S.; Gurlo, T.; Glabe, C.G.; Butler, P.C. Autophagy defends pancreatic β cells from human islet amyloid polypeptide-induced toxicity. The Journal of clinical investigation 2014, 124, 3489–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, S.; Sakagashira, S.; Shimajiri, Y.; Eberhardt, N.L.; Kondo, T.; Kondo, T.; Sanke, T. Autophagy protects against human islet amyloid polypeptide-associated apoptosis. Journal of diabetes investigation 2011, 2, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.F.; Gurlo, T.; Daval, M.; Huang, C.J.; Matveyenko, A.V.; Butler, P.C.; Costes, S. Human-IAPP disrupts the autophagy/lysosomal pathway in pancreatic β-cells: protective role of p62-positive cytoplasmic inclusions. Cell Death & Differentiation 2011, 18, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigihara, N.; Fukunaka, A.; Hara, A.; Komiya, K.; Honda, A.; Uchida, T.; Abe, H.; Toyofuku, Y.; Tamaki, M.; Ogihara, T.; et al. Human IAPP–induced pancreatic β cell toxicity and its regulation by autophagy. The Journal of clinical investigation 2014, 124, 3634–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, M.E.; Paulsson, J.F.; Schultz, S.W.; Ingelsson, M.; Westermark, P.; Westermark, G.T. In vivo seeding and cross-seeding of localized amyloidosis: a molecular link between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease. The American journal of pathology 2015, 185, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.; Barisone, G.A.; Diaz, E.; Jin, L.W.; DeCarli, C.; Despa, F. Amylin deposition in the brain: A second amyloid in Alzheimer disease? Annals of neurology 2013, 74, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawver, J.N.; Ghiwot, Y.; Koola, C.; Carrera, W.; Rodriguez-Rivera, J.; Hernandez, C.; Dineley, K.T.; Kong, Y.; Li, J.; Jhamandas, J.; et al. Islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP): a second amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Current Alzheimer research 2014, 11, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srodulski, S.; Sharma, S.; Bachstetter, A.B.; Brelsfoard, J.M.; Pascual, C.; Xie, X.S.; Saatman, K.E.; Van Eldik, L.J.; Despa, F. Neuroinflammation and neurologic deficits in diabetes linked to brain accumulation of amylin. Molecular neurodegeneration 2014, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.A.; Ittner, L.M.; Lim, Y.L.; Götz, J. Human but not rat amylin shares neurotoxic properties with Abeta42 in long-term hippocampal and cortical cultures. FEBS letters 2008, 582, 2188–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.M.; Velkova, A.; Tatarek-Nossol, M.; Andreetto, E.; Kapurniotu, A. IAPP mimic blocks Abeta cytotoxic self-assembly: cross-suppression of amyloid toxicity of Abeta and IAPP suggests a molecular link between Alzheimer's disease and type II diabetes. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2007, 46, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.M.; Velkova, A.; Kapurniotu, A. Molecular characterization of the hetero-assembly of β-amyloid peptide with islet amyloid polypeptide. Current pharmaceutical design 2014, 20, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreetto, E.; Yan, L.M.; Tatarek-Nossol, M.; Velkova, A.; Frank, R.; Kapurniotu, A. Identification of hot regions of the Abeta-IAPP interaction interface as high-affinity binding sites in both cross- and self-association. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2010, 49, 3081–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Drake, J.; Pocernich, C.; Castegna, A. Evidence of oxidative damage in Alzheimer's disease brain: central role for amyloid beta-peptide. Trends in molecular medicine 2001, 7, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrks, T.; Dyrks, E.; Hartmann, T.; Masters, C.; Beyreuther, K. Amyloidogenicity of beta A4 and beta A4-bearing amyloid protein precursor fragments by metal-catalyzed oxidation. The Journal of biological chemistry 1992, 267, 18210–18217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmblad, M.; Westlind-Danielsson, A.; Bergquist, J. Oxidation of methionine 35 attenuates formation of amyloid beta -peptide 1-40 oligomers. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 19506–19510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustbader, J.W.; Cirilli, M.; Lin, C.; Xu, H.W.; Takuma, K.; Wang, N.; Caspersen, C.; Chen, X.; Pollak, S.; Chaney, M.; et al. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2004, 304, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.N.; Harper, C.G.; Stokes, G.B.; Masters, C.L. Increased cerebral glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in Alzheimer's disease may reflect oxidative stress. Journal of neurochemistry 1986, 46, 1042–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaar, M.; Zhai, S.; Pilch, P.F.; Doyle, S.M.; Eisenhauer, P.B.; Fine, R.E.; Gilchrest, B.A. Binding of beta-amyloid to the p75 neurotrophin receptor induces apoptosis. A possible mechanism for Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of clinical investigation 1997, 100, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Norton, D.D.; Wang, X.; Kusiak, J.W. Abeta 17-42 in Alzheimer's disease activates JNK and caspase-8 leading to neuronal apoptosis. Brain : a journal of neurology 2002, 125, 2036–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Ferreiro, E.; Cardoso, S.M.; de Oliveira, C.R. Cell degeneration induced by amyloid-beta peptides: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN 2004, 23, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, K.; Miller, M.; Chludzinski, A.; Herrup, K.; Zagorski, M.; Lamb, B.T. The PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway regulates Abeta oligomer induced neuronal cell cycle events. Molecular neurodegeneration 2009, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba, R.A.; Farias, G.; Scheu, J.; Bronfman, M.; Marzolo, M.P.; Inestrosa, N.C. Signal transduction during amyloid-beta-peptide neurotoxicity: role in Alzheimer disease. Brain research. Brain research reviews 2004, 47, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P.; Tomaselli, K.J.; Rydel, R.E. Calcium-destabilizing and neurodegenerative effects of aggregated beta-amyloid peptide are attenuated by basic FGF. Brain research 1993, 621, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, H.; Eckert, A.; Müller, W.E. Disturbances of the neuronal calcium homeostasis in the aging nervous system. Life sciences 1994, 55, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, W.E.; Kirsch, C.; Eckert, G.P. Membrane-disordering effects of beta-amyloid peptides. Biochemical Society transactions 2001, 29, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier, Y.; Zarándi, M.; Penke, B. Amyloid beta-peptide interactions with neuronal and glial cell plasma membrane: binding sites and implications for Alzheimer's disease. Journal of peptide science : an official publication of the European Peptide Society 2004, 10, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulian, D.; Haverkamp, L.J.; Yu, J.H.; Karshin, W.; Tom, D.; Li, J.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Kuo, L.M.; Roher, A.E. Specific domains of beta-amyloid from Alzheimer plaque elicit neuron killing in human microglia. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 1996, 16, 6021–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haass, C.; Selkoe, D.J. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2007, 8, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S.T.; Vieira, M.N.; De Felice, F.G. Soluble protein oligomers as emerging toxins in Alzheimer's and other amyloid diseases. IUBMB life 2007, 59, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glabe, C.G.; Kayed, R. Common structure and toxic function of amyloid oligomers implies a common mechanism of pathogenesis. Neurology 2006, 66, S74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, P.R.; Dubey, A.K.; Masters, C.L.; Martins, R.N.; Macreadie, I.G. Abeta aggregation and possible implications in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2009, 13, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, R.; Deb, S.; Shome, G.; Sarkar, V.; Lahiri, D.; Datta, S.S.; Benito-León, J. Molecular dynamics of amyloid-β transport in Alzheimer's disease: Exploring therapeutic plasma exchange with albumin replacement – Current insights and future perspectives. Neurologia (Barcelona, Spain) 2025, 40, 306–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.C.; Boggs, L.N.; Fuson, K.S. Neurotoxicity of human amylin in rat primary hippocampal cultures: similarity to Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta neurotoxicity. Journal of neurochemistry 1993, 61, 2330–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.A.; Rhein, V.; Baysang, G.; Meier, F.; Poljak, A.; Raftery, M.J.; Guilhaus, M.; Ittner, L.M.; Eckert, A.; Götz, J. Abeta and human amylin share a common toxicity pathway via mitochondrial dysfunction. Proteomics 2010, 10, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).