1. Introduction

To optimize safe, quality healthcare, it is essential that clinicians are supported in attending mandatory training, including Basic Life Support (BLS). Competence in BLS is a vital, lifesaving requirement for all health professionals (HPs) working in clinical settings. To achieve competence in BLS, it is usually mandatory for HPs, including nursing, medical, allied health and other health workers, to regularly attend training and education. There is a strong correlation between cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and mortality with health professional education representing the first risk mitigation strategy in terms of negative outcomes [

1]. CPR is usually performed by a team in an often chaotic and always complex clinical setting, requiring collaboration, teamwork and effective communication among interdisciplinary health professionals to enhance any chance of an optimal outcome [

2].

Moreover, there is credible support for interprofessional education (IPE) from the World Health Organisation based on years of research linking IPE with successful clinical outcomes [

2]. Recent research reports that healthcare students identify interactive, practice-based IPE as a significantly meaningful educational experience [

3]. It stands to reason that delivering BSL training within a meaningful educational environment is likely to result in deeper acquisition of knowledge and skill and potentially greater retention of the skill required to sustain life in a real-world cardiac event.

There is evidence that for many HPs, exposure to cardiac arrest is relatively uncommon [

4] while HP competence in BLS is often insufficient [

5]. It is also widely known that prompt initiation of high-quality BLS can optimise outcomes and save lives [

6]. Clearly, there is an imperative for HPs to maintain competence, if not expertise, in BLS through contextual knowledge acquisition and regular training [

7]. It is also important to consider the underlying philosophy of education to inform learning and teaching strategies of mandatory training,

Philosophical viewpoints determine elements of education such as purpose, goals, values, teaching, learning and assessment strategies [

8]. Philosophy underpins clinical practice requiring HPs to not only apply practical skills but also understand the context in which practical skills are applied [

8,

9]. This philosophical approach underpins the ADDIE framework which comprises five cyclical phases: Analyse, Design, Develop, Implement and Evaluate [

10,

11,

12,

13] which will be explained in a later section. The overall aim of using the ADDIE model is twofold: to equip educators with teaching skills based on a robust and flexible theoretical model and to enhance learning and patient outcomes through improved HP attendance and upskilling during mandatory BLS and other training. Thus, the aim of this paper is to outline a theory-based implementation strategy for an interprofessional mandatory training program, including BLS, using a well-known published instructional design framework known by its acronym, ADDIE.

This article extends existing knowledge about ADDIE by integrating instructional design strategies that are effective, efficient, engaging and specific for high-risk scenarios like BLS training. This approach enhances learning and transfer of life saving skills to improve quality and safety patient outcomes.

2. Background

Evidence of staff competence in BLS is required to meet professional and accreditation standards in most healthcare organisations [

14]. However, finding time amid a busy workload to attend mandatory training can be challenging for many HPs. Research indicates that there are several barriers to staff attendance for mandatory training including attitude, scheduling logistics and unrealistic self-perception of skill [

15]. Enablers for attendance at mandatory training such as BLS have been identified as positive attitude, workplace flexibility, leadership, and redesigned, interactive training programs [

15,

16]. Use of an instructional design model such as ADDIE delivered in an interprofessional environment can introduce efficiencies into a training program that impacts patient care. In addressing the aim of this paper, a philosophical approach to implementation of the ADDIE model in a learning environment was explored.

3. Theoretical Foundations

This section outlines a quality learning education and training strategy for health professionals supported by a sound philosophical grounding. This is particularly important in an IPE learning environment where theory underpins broad-based clinical experience and different types and levels of disciplinary knowledge rather than training strategies that are more reliant on learning outcomes [

2,

17]. An evaluation of outcomes of implementation strategies explored in this paper will be reported in a later publication.

Education is underpinned by four main philosophies: pragmatism, realism (both traditional), pragmatism and existentialism (both contemporary) [

8]. Three philosophies of realism, pragmatism and existentialism offer a good fit for implementation of mandatory HP education including BLS training.

A realism perspective is based on natural laws where humanistic knowledge is acquired through logic, abstraction and sensory perception [

8]. Such knowledge is inherent in health service delivery where the human touch is a common feature in interactions between the HP and the patient. Aspects of learning within a realism approach include developing leadership which operates at a high level during cardiopulmonary resuscitation where the HP must demonstrate leadership and authority to optimise patient outcomes.

The philosophical position of pragmatism is relevant to learning in healthcare settings [

18]. From a pragmatist’s perspective, knowledge is viewed as evolving and experiential with a focus on critical thinking and scientific processes [

8,

18]. This perspective supports mandatory training where a learner-centred approach offers opportunity to apply critical thinking, scientific knowledge of the human body and practicing skill in responding to the deteriorating patient.

The existentialist view is that a learner can choose and explore their identity through engaging in activities that are emotionally meaningful [

8]. Mandatory training provides an opportunity for HP participation in group and individual simulation activities with the ability to reflect and share their experience with the clinical assessor, enhancing meaningfulness of the training experience.

4. Instructional Theories and Design

Instructional theories and design have an important part in the development of instructional materials to facilitate learning and performance. Knowledge and skill such as is required for BLS and other mandatory training outcomes, is strengthened by blending learning theories in the instructional design (ID) program through use of theory-based strategies that support acquisition of adaptive expertise in healthcare training environments [

2,

19]. The theory of cognitivism, for example, recognises the importance of prior knowledge and skills that HPs bring to training in acquiring and assimilating new learnings [

20]. A cognitivist perspective will allow HPs to decide at the start of a BLS assessment, for example, how much practice they require before undertaking their assessment [

21].

In contrast to cognitivism, constructivist learning is founded on assimilation of the learner’s understanding and connections in an interactive social environment that contribute towards resilience in facing challenges which frequently occur in the clinical environment [

20]. Mandatory training encapsulates a constructivist learning environment that motivates the HP both intrinsically and extrinsically. For instance, a constructivist approach enables the HP to practice mandatory BLS skill on high-fidelity mannequins before a final assessment [

22]. Whichever approach is applied, clinical assessors should use open-ended questions to promote HP critical thinking, thus providing motivation to assimilate new learning [

23].

Clinical assessors should also maintain a zone of proximal distance, known as Vygotsky’s ‘intentional scaffolding’ to facilitate and motivate learning on a developmental trajectory [

8]. Scaffolding in the design of education benefits all learning preferences and improves knowledge and skills as the HP learns increasingly complex levels of practical skill [

24,

25].

Healthcare provides an effectively complex environment in which to deliver training and education, often requiring effective communication and teamwork across multidisciplinary staff members [

26]. Enhanced teamwork may result from a greater understanding of other professional roles, responsibilities and role relationships that occur within a multidisciplinary learning environment [

16]. Thus, the ADDIE model offers a framework to organise learning within a multidisciplinary environment [

27]. The following section outlines the application of the ADDIE model.

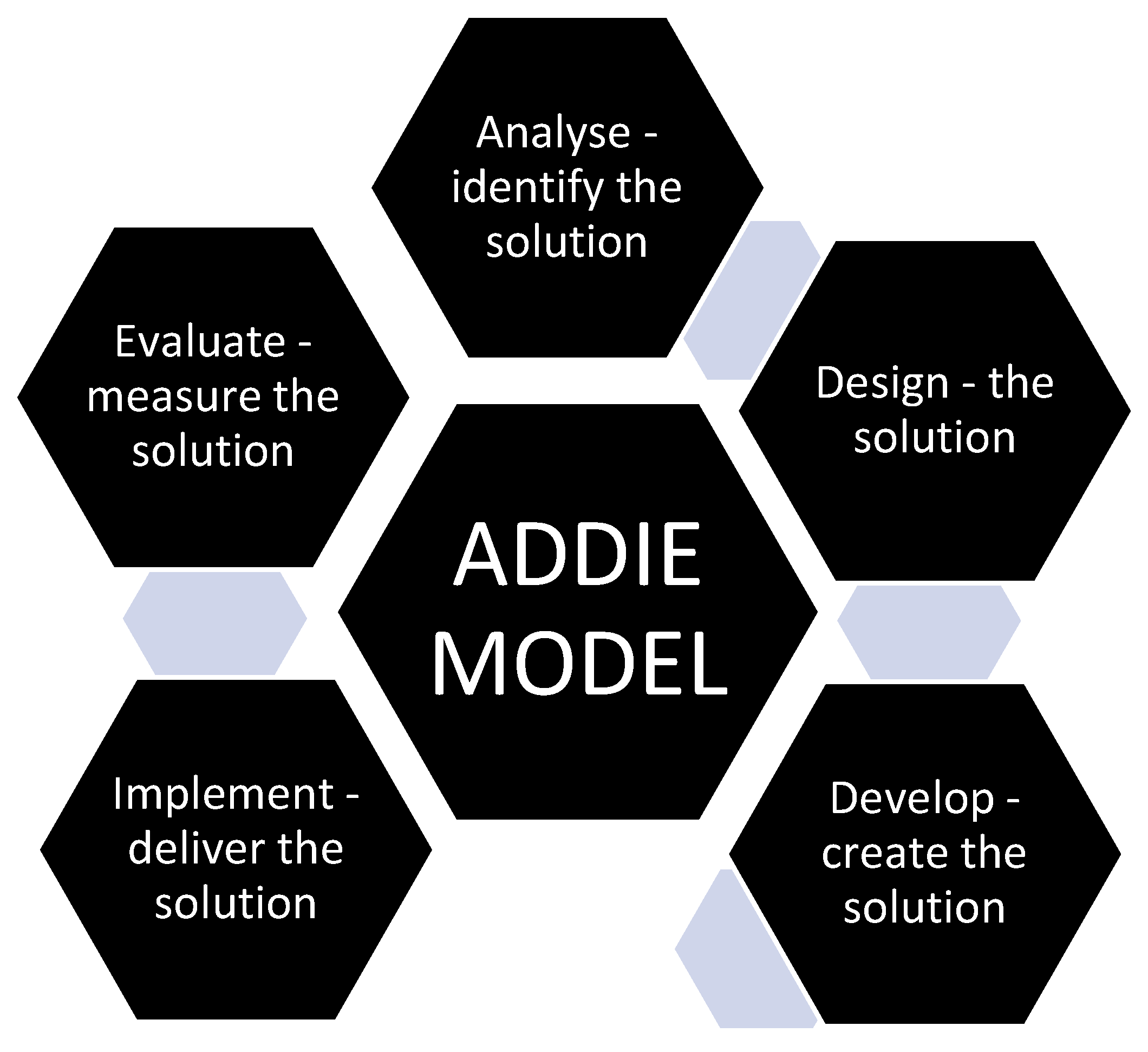

5. Method - Mandatory Training Process Using the ADDIE Model

Integration of learning is especially important when the components of instruction are planned. The heart of instructional design is the design for the active learner. In the context of poor HP attendance at mandatory training, the authors investigated learning methods that would encourage greater HP attendance. The ADDIE model (see

Figure 1) was selected as an appropriate instructional model for mandatory training in a healthcare environment due to its wide application, flexibility with goal setting and ease of use [

13,

28,

29].

5.1. Figure 1: Elements of the instructional design ‘ADDIE’ Model

As noted, the ADDIE model encompasses five cyclical phases: Analyse, Design, Develop, Implement, Evaluate [

31,

32]. The five-step iterative process is often used by instructional designers and is applicable to mandatory training including BLS, due to its flexibility, systematic approach and promotion of rapid skill acquisition [

29]. The ADDIE process focuses on learning needs, goals, learning strategies and evaluation of relevant training skills [

31]. The five cyclical phases incorporate:

Figure 1.

Elements of the instructional design ‘ADDIE’ Model. Source [

30].

Figure 1.

Elements of the instructional design ‘ADDIE’ Model. Source [

30].

5.2. Analysis – Best Approach to Design and Develop

Analysing the health professional (HP) learner profiles (learner needs, cultural and special needs, working backgrounds and learning environment) and professional standards, and how mandatory practical training processes will be undertaken and the specific content to be taught.

Analysing the broad goals of training and using task analysis (skills, knowledge, and communication) required by the HP. Discussing objectives and expectations of key stakeholders, underlying philosophies to be used and training resources and constraints.

Analysing achievements, for example, quality of HP skill development and evaluating increased HP attendance rates.

Determining training and competency needs for the BLS clinical assessors undertaking BLS assessments and requirements of other educational experts delivering mandatory training.

Considering organisational requirements around mandatory training and BLS.

5.3. Design – Using the Analysis Information to Inform Design of the Learning and Assessment Resources

Benchmarking involves comparing performances against known standards using appropriate assessment measures, that is, identifying learning outcomes and evaluating how the HP achieved successful completion of the assessment (learning objectives).

Designing and selecting appropriate instructional strategies, for example, applying e-learning, assessment processes that are underpinned by the philosophies of realism, pragmatism and existentialism using blended learning theories of cognitivism and constructivism.

Determining organisational requirements of the sequence of BLS skills to achieve.

5.4. Develop – Learning Materials Are Created

Utilising instructional strategies to facilitate the learning objectives and validate the learning resources for the mandatory training sessions. Planning the logistics for the training (scheduling, venue, clinical assessors, tools, high fidelity mannequins).

Ensuring that training aligns with safety and quality standards

5.5. Implementation – Delivering the Training to HP

Preparing the training setting to engage the HP for the training and trialling of a mandatory training session. For instance, provide feedback during practice, ensuring appropriate ergonomics of equipment and assessment processes.

5.6. Evaluation – Ensure Quality Training and Quality Learning Assessment Outcomes

Confirming that training resources are accurate and up to date.

Ensuring a safe work environment during BLS training and assessment.

Reviewing and updating content to maintain quality.

Evaluating the mandatory training pre/post implementation of ADDIE via pre and post self-assessed survey, assessor skill level observation or application of an assessment tool. Reviewing what was successful, what was learnt and what needs changing. Repeat ADDIE again, if required.

6. Evaluation

Quality and safety considerations are embedded in each stage of ADDIE to promote desired learning outcomes. The model utilises a systematic process for training development for HPs that is reliable [

31,

32]. Instructional design can also be instrumental in accomplishing planned changes. Evaluation of the learning setting should form part of the overall evaluation of the mandatory training and education process. This aspect of the instructional design process will be reviewed in the following sections.

6.1. The Learning Setting

Evaluating the setting determines the usefulness and effectiveness of mandatory training delivered within an educational environment. While numerous methods of evaluating the outcome of training and education have been described [

20,

33], a realist evaluative approach which is framed in terms of context (C) mechanism (M) and outcomes (O) is recommended [

34,

35]. In this approach, data is collected using multi methods followed by analysis of the ‘C M O’ concepts [

34,

35]. To provide balance, the following section outlines an alternative evaluation method that could be utilised in the training process.

6.2. P Model Incorporating Presage-Process-Product

Another method that can be used to evaluate the learning and teaching setting is the 3P model incorporating presage-process-product [

36]. Presage is described as planning and design which incorporates context and characteristics of the learners and facilitators; process reflects content delivery; and product is the outcome of student learning, with all 3Ps being analysed to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the learning and teaching environment.

6.3. Task Analysis

The aim of the ADDIE model is to improve attitude, knowledge and skills of the HP through [instructional] design of the mandatory training program [

33]. Task analysis of training includes (a) task; (b) knowledge; (c) skills and (d) attitudes of the HP to mandatory training [

31,

33]. Bloom’s Taxonomy has long been the standard and remains useful for curriculum development applicable to the ADDIE model with the following concepts of cognition (knowledge), affective (attitude) and mandatory motor skills that require higher order thinking [

37] while Fink’s taxonomy offers a an alternative in developing learning objectives appropriate for BLS training by focusing on learning that is contextual with authentic real world experiences [

37]. The point here is that alternative options can be explored during content development.

6.4. Post Implementation Evaluation

It is important that there is an evaluation of the ADDIE instructional design model post implementation of the learning and teaching program. A useful model to follow for post implementation evaluation is Kirkpatrick’s educational outcomes framework which has been successfully utilised in both an IPE environment and in ADDIE designed training and education programs [

2,

11]. Evaluation criteria appraise four learning outcome-based domains: reaction, learning, behaviour and results that can be combined with other evaluation models to provide a broad and accurate reflection of the success of the program [

11]. The evaluation process also provides an assessment of any adjustments that need to be made to the design and mode of delivery.

7. Results

The literature has shown that through its iterative capability, the ADDIE model promotes rapid acquisition of clinical skills that can reduce time spent when attending mandatory BLS training. There is also an obvious link between higher order critical thinking, enhanced clinical practice among nurses and improved patient outcomes. Theoretical based learning is enhanced when learners are provided with opportunities to connect knowledge components in structuring connectivity between information [

38,

39] which can be facilitated from within a learning environment. From a practical implication perspective, and as previously noted, a positive attitude towards BLS training has also been identified as an enabler for mandatory training attendance.

8. Discussion

The importance of basing practical training on sound theoretical principles in a healthcare environment was highlighted in an observation and control study that sought to analyse the effects of blended learning based on the ADDIE model [

19]. Findings revealed an improvement in theoretical knowledge, practical skills, self-directed learning abilities, critical thinking skills and teaching satisfaction among nursing staff members [

19]. In comparing conventional nurse education delivered to a control group, with blended learning based on the ADDIE model delivered to an observation group, significantly higher scores of critical thinking among the observation group were reported [

19]. The authors concluded that teaching based on the ADDIE model could improve self-learning and theoretical knowledge that enhanced clinical nursing practice [

19].

Further evidence of the utility of ADDIE as an instructional design model was found in a study that applied the ADDIE model to develop a mobile application (app) that would educate and support self-care for patients undergoing breast cancer surgery. During development of the app, the authors noted that ADDIE supported content that appealed to multiple senses [

28] which accommodates different learning needs for students.

The ADDIE model has also been utilised in an Australian based pharmacy preceptor training study [

11]. Pharmacist preceptors (n=28) completed an ADDIE design preceptor training program and reported the interactivity and networking aspects as highlights of the program. While the limitation of the study was the low number of preceptor training completions, the authors noted the positive response from participants who underwent the training as well as the flexibility of the model as a mode of delivery and predict the model will be expanded across a broad range of interprofessional healthcare training sites going into the future [

11].

A quasi-experimental study conducted among 55 HPs attending BLS-AED training revealed that repeated BLS-AED training improved attitudes associated with responding to patient deterioration that impacted positively on patient survival rates [

16]. Study findings also revealed that the more highly trained HPs were, the more likely they were to have a positive attitude towards BLS-AED training compared to peers with limited experience [

16]. Scheduling regular skill refreshers with immediate feedback has also been identified as a motivating factor for staff attendance [

16,

38,

39].

While interprofessional collaborative education and training practice to improve competence is important for healthcare professionals who commonly practice in a complex team environment, there are some barriers to be considered. In acknowledging a recent trend towards collaborative health education, research reports that healthcare is still delivered in professional silos, often a consequence of traditional disciplinary-based hierarchical approaches to education [

39]. A siloed approach overlooks the benefits of planned scheduling in a multidisciplinary educational environment. There is also the issue of limited knowledge and understanding of different healthcare roles among HPs which can result in lack of skill in collaborative teamwork [

39]. Similar findings that hierarchical professional differences and negative perceptions of teamwork could act as barriers to learning have been identified [

39]. A barrier to attendance and undertaking assessments may also be a factor contributing to low attendance for mandatory training. It is also clear that further research is required to identify the impact of instructional design and other methods of training and education on health outcomes [

39,

40].

The literature demonstrates an ethical responsibility to promote learning for HP to support professional development in mandatory training including BLS [

41]. This includes instructional learning strategies to promote inclusion of all learners. A potential limitation to the strategy includes the role of the trainer and clinical assessor facilitators undertaking BLS assessments. Using blended learning theories of cognitivism and constructivism relies on the facilitator to promote learning rather than work from expert teacher style for BLS assessments [

20,

23].

The strategy requires an inclusive learning environment, bringing equality, diversity and right issues to the training [

41,

42]. It is essential for facilitators to provide a positive and equitable learning environment that values diversity and promotes equality and autonomy of the HP undertaking mandatory training including BLS [

42].

9. Conclusions

This paper has detailed the aim, theoretical underpinnings and recommended processes to implement an interprofessional mandatory training program using a well-known published instructional design framework known by its acronym, ADDIE. The overall aim is to motivate HP attendance and maintain competence in essential practical skills such as BLS through regular training and education. Attendance by health professionals for mandatory training is well-identified as a challenge for both the health professional and the organisation. Many organisations struggle to meet their compliance targets for HPs undertaking mandatory training and assessment and are at risk of not meeting accreditation requirements. This situation potentially places patients within the organisation at risk of BLS being performed by staff who may not be competent to deliver such vital quality care. By drawing on current literature, this conceptual paper has shown that training and education founded on theory, framed by the ADDIE instructional design model offers an efficient combination for quality learner training, education and development. Combining different approaches to health professional education can be an effective educational strategy, particularly when the purpose is to improve HP compliance in attending and undertaking mandatory training including BLS.

Funding

No funding has been received in relation to this manuscript or its content.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was not required as no human data was collected.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors attest that, in submitting this manuscript, no conflict of interest exists.

References

- Spinelli G; Brogi E; Sidoti A; Pagnucci A; Forfori F. Assessment of the knowledge level and experience of healthcare personnel concerning CPR and early defibrillation: an internal survey. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. [CrossRef]

- Gum L; Salfi J. Interprofessional education (IPE): Trends and context. In Clinical education for health professions: Theory and practice, 1 ed.; Nestel D, Reedy G, McKenna L, Gough S, Eds.; Springer: 2023; pp. 168 - 180.

- O’Leary N; Salmon N; Clifford A. ‘It benefits patient care’: The value of practice-based IPE in healthcare curriculum. BMC Medical Education 2022, 20, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran KV; Abraham SV. Basic Life Support: Need of the Hour—A Study on the Knowledge of Basic Life Support among Young Doctors in India. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine 2020, 24, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix LD; Skjødt-Jensen AM; Jensen TH; Aarkrog V. Enhancing nursing students’ self-reported self-efficacy and professional competence in basic life support: the role of virtual simulation prior to high-fidelity training. Teaching and Learning in Nursing 2025, 20, e236 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation. ANZCOR guidelines 8 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- Cheung JH; Kulasegaram KM. Beyond the tensions within transfer: Implications for adaptive expertise in the health professions. Advances in Health Sciences Education 2022, 27, 1293–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornstein AC; Hunkins FP. Curriculum: Foundations, principles, and issues; Pearson Education Limited: 2018; Volume 7.

- Dalrymple K; di Napoli R. Philosophy for healthcare professions education: A tool for thinking and practice. In Clinical education for health professions: Theory and practice, Nestel D, Reedy G, McKenna L, Gough S, Eds.; Springer: 2023; pp. 555 – 572.

- Chen Q; Li Z; Tang S; Zhou C; Castro A; Jiang S; Huang C; Xiao J. Development of a blended emergent research training program for clinical nurses (part 1). BMS Nursing 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott G; Mylrea M; Glass B. How should we prepare our pharmacist preceptors? Design, development and implementation of a training program in a regional Australian university. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang B; Zhang J; Qu Z; Jiang N; Chen C; Cheng S. Development of COVID-19 infection prevention and control training program based on ADDIE model for clinical nurses: A pretest-posttest study. Nursing and Health Sciences 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J; Chen H; Wang X; Huang X; Xie D. Application of flipped classroom teaching method based on ADDIE concept in clinical teaching for neurology residents. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). National safety and quality health service standards. 2021, doi:https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/.

- McAuliffe MJ; Gledhill S. Enablers and barriers for mandatory training including Basic Life Support in an interprofessional environment: An integrated literature review. Nurse Education Today 2022, 119, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolfotouh MA; Alnasser MA; Berhanu AN; Al-Turaif DA; Alfayez AI. Impact of basic life-support training on the attitudes of health-care workers toward cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation. BMC Health Services Research 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones T; Burdett T; Chow YL; Jönsson L; Lasater K; Mathews L. Case studies of interprofessional education initiatives from five countries. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2018, 50, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlis D; Gkiosis J. John Dewey, from philosophy of pragmatism to progressive education. Journal of Arts and Humanities 2017, 6, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo R; Li J; Zhang X; Tian D; Zhang Y. Effects of applying blended learning based on the ADDIE model in nursing staff training on improving theoretical and practical operational aspects. Frontiers in Medicine 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braungart MM; Braungart RG; Gramet PR. Applying learning theories to healthcare practice. In Nurse as educator: Principles of teaching and learning, 6 ed.; Bastable, S., Ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: 2021; pp. 79-120.

- Cecilio-Fernandes D; Patel R; Sandars J. Using insights from cognitive science for the teaching of clinical skills: AMEE Guide No. 155. Medical Teacher 2023, 35, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks KW; Coben D; O’Neill D, J. A.; Weeks A; Brown M; Pontin D. Developing and integrating nursing competence through authentic technology-enhanced clinical simulation education: Pedagogies for reconceptualising the theory-practice gap. Nurse Education in Practice 2019, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang LH; Lin CC; Han CY; Huang YL; Hsiao PR; Chen LC. Undergraduate nursing student academic resilience during medical surgical clinical practicum: A constructivist analysis of Taiwanese experience. Journal of professional nursing 2021, 37, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess A; Matar E; Roberts C; Haq I; Wynter L; Singer J; Kalman E; Bleasel J. Scaffolding medical student knowledge and skills: team-based learning (TBL) and case-based learning (CBL). BMC Medical Education 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, N. Back to basics for nursing education in the 21st century. Nurse Education Today 2018, 68, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel H; Perry S; Badu E; Mwangi F; Mazurskyy A; Walters J; Tavener M; Noble D; Sherphard C; Lethbridge L; et al. A scoping review of interprofessional education in healthcare: Evaluating competency development, educational outcomes and challenges. BMC Medical Education 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim S-O. Effect of case-based small-group learning on care workers’ emergency coping abilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin A; Gursoy A; Karal H. Mobile care app development process; Using the ADDIE model to manage symptoms after breast cancer (step 1). Discover Oncology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackh, BM. Pivoting your instruction: A guide to comprehensive instructional design for faculty; Routledge: 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Addie Model. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/training/development/addie-model.html (accessed on.

- Branch, RM. Instructional Design: The ADDIE Approach, 1 ed.; Springer: 2009.

- Branch, RM. Instructional design for training programs. In Educational technology to improve quality and access on a global scale Papers from the Educational Technology World Conference (ETWC 2016), Persichitte KA, Suparman A, Spector M, Eds.; Springer: 2018; pp. 1-7.

- Oudbier J; Verheijck E; van Diermen D; Tams J; Bramer J; Spaai G. Enhancing the efectiveness of interprofessional education in health science education: a state-of-the-art review. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham AC; McAleer S. An overview of realist evaluation for simulation-based education. Advances in Simulation 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra JD; Edwards Jr DB. Systems, complexity and realist evaluation: Reflections from a large-scale education policy evaluation in Colombia. In Systems thinking in international education and development, M Faul, Savage., L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: 2023; pp. 183-203.

- Chan, YK. Investigating the relationship among extracurricular activities, learning approach and academic outcomes: A case study. Active Learning in Higher Education 2016, 17, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes TC; Guinan EM. Interprofessional education focused on medication safety: A systematic review. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2023, 37, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabney B; Eid F. Comparing educational frameworks: Unpacking differences between fink’s and Bloom’s taxonomies in nursing education. Teaching and Learning in Nursing 2024, 19, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diggele C; Roberts C; Burgess A; Mellis C. Interprofessional education: tips for design and implementation. BMC Medical Education 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, T. Building interprofessional teams through partnerships to address quality. Nursing Science Quarterly 2019, 32, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Q; Chen Q; Ma C; Zhang Y; Gou M; Yang W. Moral sensitivity, moral courage, and ethical behaviour among clinical nurses. Nursing Ethics 2025, 32, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop J; Lane J; Hegarty D; Thomas J. ‘Being and becoming a practice educator’: An AHP online programme. Clinical Teacher 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).