1. Introduction

According to the definition [

1], clinical trials (CT) are carefully designed and verified analyses of new diagnostic and treatment methods that follow a pre-approved protocol. Furthermore, the Medical Research Agency, established in Poland by law since 2019, which is responsible for the development of research in the field of medical sciences and health sciences, emphasizes that they are aimed at discovering or confirming the clinical, pharmacological, including pharmacodynamic effects of one or more investigational medicinal products. CT are also performed with the aim to identify adverse reactions and to track the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of one or more investigational medicinal products, considering their safety and efficacy [

2]

Poland, along with the rest of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), has grown into a market leader in innovative bio-pharmaceutical commercial clinical trials (iBPCT): in 2019, it ranked 11th in the world in terms of iBPCT market share, and in 2014–2019, it recorded one of the largest increases in iBPCT market share in the world, ranking 5th behind China, Spain, South Korea, and Taiwan [

3]. Undoubtedly, the issue of recruitment to CT remains a complicated process, and the success of a clinical trial largely depends on the successful recruitment of an appropriate number of participants in the subsequent phases of the study and on participants retention. [

4]. This process requires careful planning, direct networking and awareness-raising among the public [

5]. Recruitment is one of the key stages of clinical trials, encompassing dialogue between researchers and volunteers that begins even before the formal informed consent process. As part of the recruitment process, researchers identify and segment potential participants and compile lists of eligible individuals. At this stage, it is important to provide detailed information that can ignite interest in the study and build trust with potential participants. [

6].

Research shows that patients want to be sure that the expected benefits of participation outweigh the potential risks, inconveniences and other difficulties related to participation in a clinical trial. For many of them, it is crucial to understand exactly what the benefits and risks may be in order to be able to make an informed decision to participate in a clinical trial [

7]. Therefore, it is crucial that researchers and recruiters actively encourage potential participants to share their questions and concerns, provide relevant information, and support them in overcoming their doubts [

8]. Any unresolved doubts and questions contribute to maintaining distrust, which hinders the recruitment process. Additionally, when patients refuse to participate due to unexpressed concerns, they miss out on potential benefits such as access to high-quality diagnostics and medical care, increased sense of security in the face of illness, trust in the therapeutic team, community with other patients, in-depth understanding of one's health condition and satisfaction from the contribution to the development of science [

9,

10].

In the context of the above, improving clear communication skills becomes one of the key elements of improving research engagement [

11], and the surveyed patients emphasize that the quality of communication significantly affects their decisions about participation in clinical trials [

12]. It is worth paying attention to the relationship between the quality of communication in clinical practice and the decision-making process, and considering which methods are the most appropriate for an effective communication with the potential participants.

Many patients when considering participation in clinical trials are motivated by the hope of having health benefits or the possibility of access to modern therapies that go beyond the current therapeutic procedures. Altruism and trust in healthcare professionals are cited as one of the main motivations [

13,

14]. Other participants, on the other hand, are driven by curiosity or interest in scientific research [

15,

16]. Participation in the research takes into account not only free access to medical care, but also the possibility of systematic monitoring of one's health [

17]. Some patients are motivated to participate by the opportunity to meet new people, socialize, and engage in something inspiring and meaningful [

18].

Research also indicates that participants in clinical trials are motivated by a desire to help others and a belief that they fully meet the inclusion criteria to the study [

10,

19,

20]. Some studies, however, suggest that altruism is not always the dominant motivator; When it is present, it often plays a secondary role [

21]. Logistical motivations (such as time and location) are also important in the decision-making process to participate in clinical trials [

6].

According to the findings from one literature review, when looking at healthy people participating in CT, financial compensation is their main motivation, along with others such as contributing to science, the health of others, and the use of additional health care services [

22]. It is emphasized that without a financial incentive in particular, the recruitment of participants for phase I of a clinical trial would be a process of slow, potentially hampering progress in the development of new medicines [

23,

24]. However, the results of many studies have shown that participants' motivations are diverse and not only dominated by financial benefits, thus providing valuable information for the ethical debate on financial incentives. Having an appropriate time frame and flexible schedule, and feeling comfortable participating in the study, were the most frequently reported facilitators, while inflexible schedule and time commitment were the most commonly reported barriers [

25]. In addition, some authors detail that people who choose not to participate in clinical trials as reasons cite the fact that they have already had the disease, concerns about changing treatments, and a lack of information about potential side effects [

26].

Stakeholders involved in clinical trials see the need to increase the effectiveness of recruitment and retention of trial participants, which can be fostered by improving the involvement of the public, patients and their families [

27]. Some of the scientific studies, like ours, focus on identifying the opinions of not only clinical trial participants, but also people who did not participate in them. In the long perspective, this allows to capture the tendency to change knowledge and social attitudes. The Centre for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation (CISCRP) conducts a global online survey every two years called the Perceptions & Insights (P&I). Since 2013, this study has examined public and patient perceptions, motivations, and experiences related to clinical research. The results of such studies are extremely important because they can be the basis for building effective involvement of the public and patients in clinical trials [

28]. So far, beliefs and attitudes towards clinical trials have already been examined in Poland [

29] and awareness of the general population [

30]. In the light of the knowledge available to us, the research presented here is the first such large-scale research conducted in our country. A better understanding of the reasons why individuals choose to participate in these studies will allow us to design interventions that translate into social benefits and eliminate a number of existing barriers to recruitment [

16].

The aim of the study is to assess the attitudes of people using medical services representing the general population to participate in clinical trials. Attention is paid to the main factors related to the interest in participating in this type of research and to the main factors determining the variability of the perception index of related benefits and side effects for health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

The survey study was conducted as part of the project Humanization of the treatment process and clinical communication between patients and medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemics. The project, carried out at the University of Warsaw, was funded by the state budget through a grant from the Medical Research Agency (2021/ABM/COVID/UW).

The quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted online between 2

nd and 20

th March 2022, among individuals registered in a research panel. The inclusion criterion was having used medical services as a patient within the past 24 months. The exclusion criteria included employment in the healthcare sector and limiting contact with medical services to vaccinations, obtaining prescriptions, or other administrative procedures. The nationwide sample was stratified by gender, age, education, region, type of locality, as well as the nature of the medical service (in-person consultation, teleconsultation) and its setting (hospital, outpatient clinic) [

31].

The study included a total of 2,050 individuals, and patient anonymity and data protection were ensured. In this article, a significant segment of the analyses focuses on the subset of 1,155 respondents who answered affirmatively to the question of whether they would be interested in participating in clinical trials in the future.

The study received a positive approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Pedagogical Faculty of the University of Warsaw (decision number 2021/8).

2.2. Dependent Variables

The block of questions assessing attitudes toward clinical research was developed by the research team following a literature review and consultations with experts. It included both researcher-generated questions and items adapted from the available frameworks, such as the Study Participant Feedback Questionnaire (SPFQ) and prior studies on patient satisfaction in clinical trials. The questions were preceded by an introductory section explaining the concept of clinical research. [

32,

33]. This section of the questionnaire identified three main thematic areas related to the decision to participate or not in the clinical trials. These included: potential burdens, such as for example the follow-up visits; factors related to communication and the physician-patient relationship; and health benefits or side effects. This article focuses on the third thematic area, while the findings related to the previous areas are described in the report on the implementation of the entire project on the humanisation of medical care [

31].

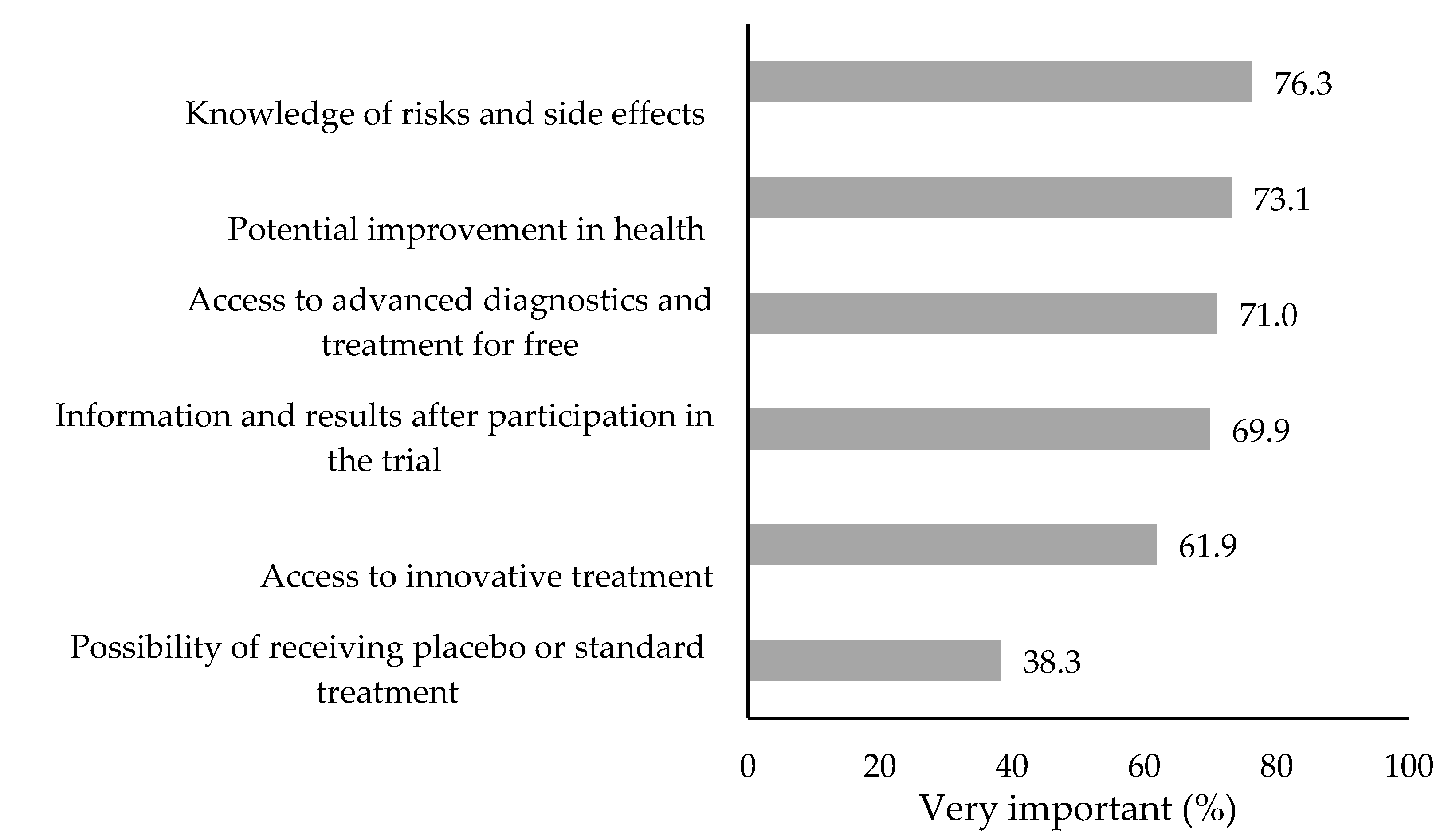

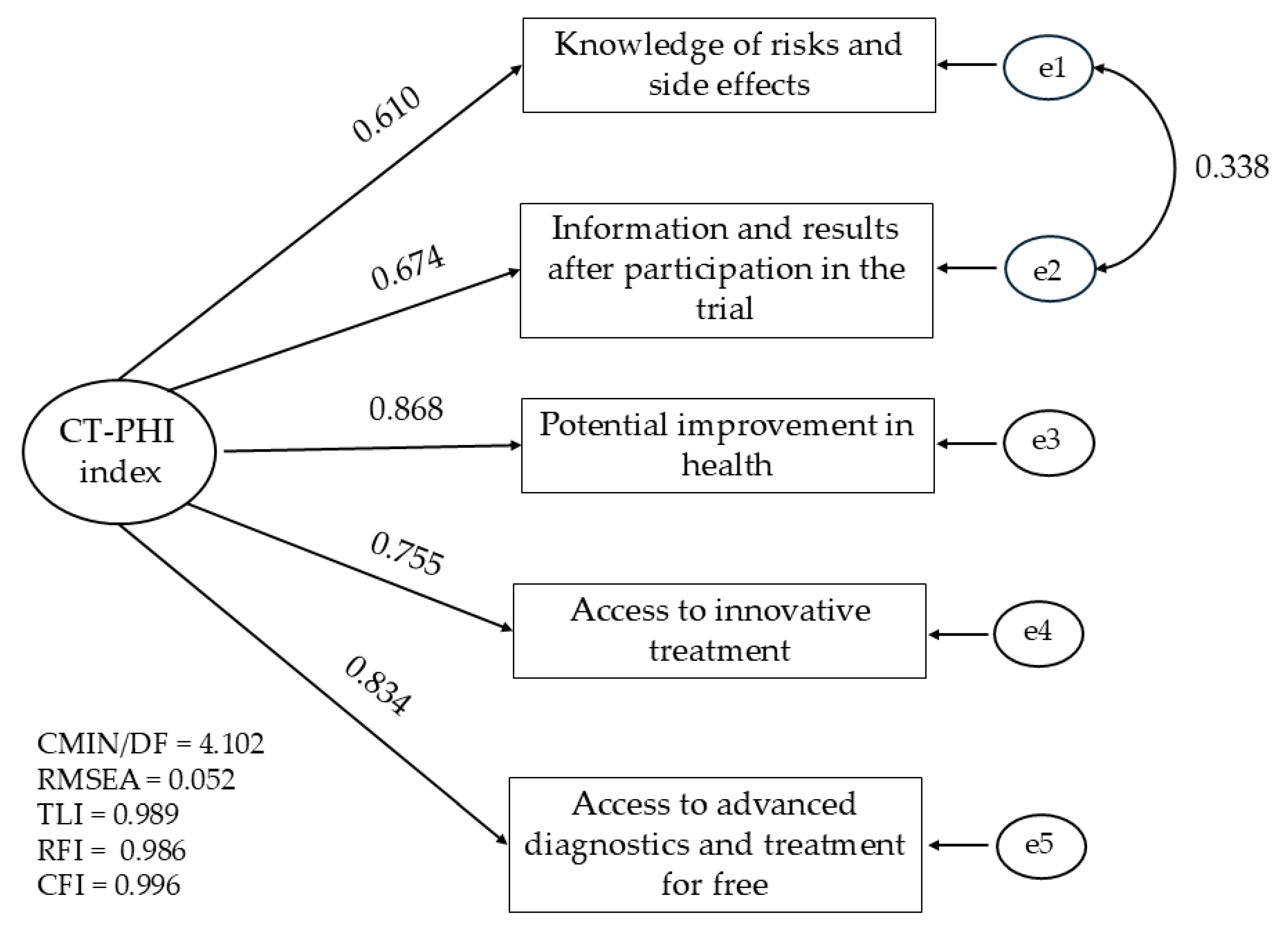

The first key variable was the interest in future participation in clinical trials. Respondents who answered affirmatively were asked about the health benefits and side effects they would consider when deciding whether to participate or withdraw from a clinical trial at the present moment or not. The importance of six reasons was assessed on a five-point scale ranging from "completely unimportant" to "very important," and a summary index referring to perceived health benefits and side effects was proposed, hereinafter referred to as Clinical Trials – Perceived Health Impact (CT-PHI).

2.3. Independent Variables

Socio-demographic factors and factors related to health assessment and use of medical services were taken into account when examining the determinants of interest in clinical trials and the variability of the CT-PHI index.

Socio-demographic factors:

Gender: men and women

Age groups: 18-35 years old; 36-50 years old, 51-65 years old, 66 years old or older

Place of residence: urban and rural

Education level: below secondary, secondary, above secondary

Being in a stable relationship in categories: yes, no

Current employment status: yes, no

Material status coded into four categories: low, average, rather high, and definitely high.

It was assessed based on a standard national question regarding the ability to meet basic living needs. Individuals with the lowest status could not afford to meet their most urgent needs, while those with the highest status were able to save part of their income or invest.

Health-Related Factors:

Self-perceived health coded into 3 categories: poor (a combination of the categories rather poor and definitely poor), average (the category neither good nor bad), and good (a combination of the categories rather good and definitely good).

Severity of five problems reducing quality of life according to the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire [

34,

35], including problems related to: mobility, looking after myself, doing usual activities, having pain or discomfort, feeling worried, sad, or unhappy. The original five response categories were recoded into four, combining the two most aggravating.

The level of knowledge of patient rights was assessed in three categories: no knowledge (I have never heard of patient rights), limited awareness (I have heard of patient rights, but I cannot name any), and comprehensive knowledge (I am familiar with patient rights).

Use of public health care in the last 24 months with response options: public only (National Health Fund), private only, both public and private

Adherence to doctor's recommendations with response categories: rarely or not at all (merger of responses: sometimes, almost never, never), almost always, always.

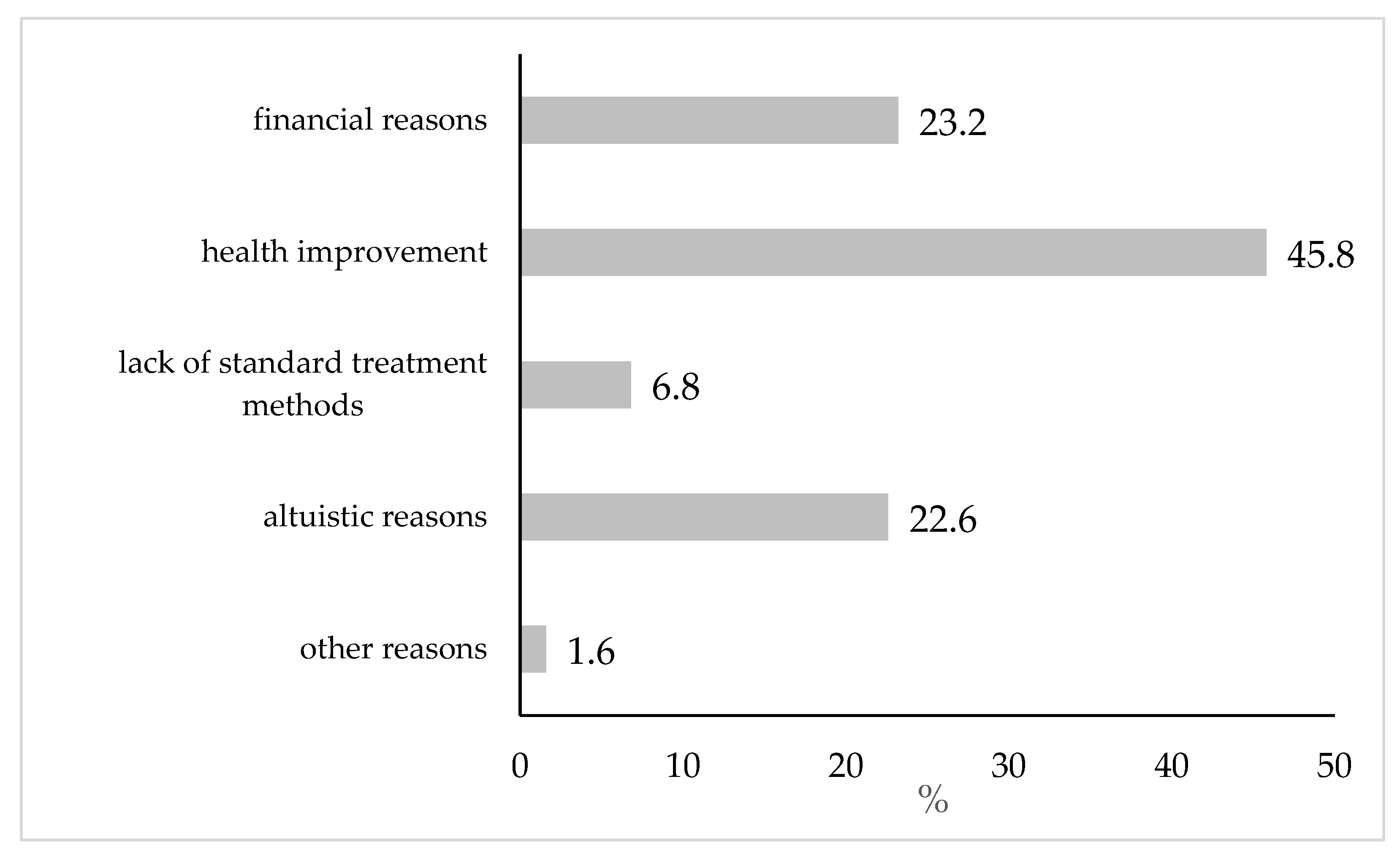

An additional feature used in the stratification of the analyses was the main reason given for participating in the clinical trials. Respondents had a choice of financial reasons, improvement of their own health, lack of available standard treatment methods of their disease, willingness to contribute to science development and improvement of the health of others (hereinafter referred to as altruistic considerations) and other reasons (to be entered).

The sample characteristics concerning the aforementioned factors are presented in the following tables. The characteristics of the full sample of 2,050 respondents and the subset of 1,155 individuals who expressed interest in participating in clinical trials are shown separately.

2.4. Data Analysis

The percentage of individuals who expressed interest in participating in clinical trials is presented according to the characteristics described above. The differences were tested with a chi-square test, interpreting the differences based on adjusted standardized residuals. A logistic model was estimated to identify independent predictors of future participation in clinical trials. The results are presented as odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The percentage distribution of responses to the question about the main reason for positive attitude towards clinical trials and the distribution of the answers provided to six questions about the potential benefits and side effects of participating in clinical trials are presented.

The psychometric properties of alternative summary CT-PHI indices were examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in order to assess the structure and reliability of both the longer and shorter scales. Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Decisions regarding the elimination of specific items were based on changes in this coefficient and the values of modification indices obtained through CFA. Detailed CFA model estimation results are provided as supplementary electronic material, which also includes an explanation of the model fit parameters. The exact results of the CFA model estimation are included as supplementary electronic material, and the importance of model fitting parameters is also explained in this appendix. The main parameter was the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) indicator, for which values below 0.08 are considered acceptable, and above 0.10 are considered poor.

The means of the CT-PHI index were compared in groups distinguished due to socio-demographic characteristics, self-assessment of health and other factors related to the use of medical services. The differences were tested with a nonparametric Mann-Whitney (MW) or Kruskal-Wallis (KW) tests depending on the number of groups compared. In the justified cases, a post hoc analysis of multiple comparisons of all group pairs for the KW test was performed.

In the last step of the analysis, generalized linear models (GLMZ) were estimated, identifying independent predictors of CT-PHI index variability, including the previously analysed demographic and social characteristics of respondents and factors related to health assessment and use of medical services as independent variables. The method was adapted to the distribution of the dependent variable and the independent variables measured on an ordinal or nominal scale. The basic model for the entire study group and models for the groups of respondents after stratification due to the main reason for interest in participating in clinical trials were estimated. When presenting the results of the estimation, the level of significance of the parameters for the explanatory variables that were included in the final model and the estimated level of fit with the R-squared coefficient of determination were given.

Logistic and linear models were estimated with a full list of sixteen independent variables and then recalculated to reduce missing data once the final solution was obtained.

Data was analysed using SPSS® version 29 (IBM, New York, NY, USA) with AMOS® (29, IBM, New York). All tests were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

4. Discussion

In our study, we assessed patients' attitudes toward CT participation by looking at key factors influencing their interest and the variability in perceptions of benefits and potential side effects. In this section, we will discuss socio-demographic factors such as age, financial situation, professional activity, place of residence, marital status and gender, and then we will analyse the factors related to health and the use of medical services that can affect this variability. However, it should be borne in mind that there is a lack of empirical research on this subject in Poland, therefore in the discussion we will refer primarily to the results of the research conducted in other countries.

4.1. Approach to Clinical Trials and Demographic and Social Characteristics of Respondents

In our own studies, the second most common choice in terms of interest in clinical trials resulted to be financial considerations (23.2%). Altruistic reasons were indicated with a similar frequency (22.7%). However, the vast majority of the respondents associated their interest in clinical trials with the desire to improve health (45.8%), which seems to be a general trend in Polish research – because in the Report "Awareness of Poles about clinical trials – Pratia 2022” [

30] the most important and most common motivation for participation in clinical trials for respondents was the chance to cure the diseases for which other methods failed (66%). Such motivations are also confirmed by studies in which the motivations to participate in later phases of clinical trials, where it is indicated that the strongest factor inducing patients to participate is the prospect of personal therapeutic benefits were analysed [

21]. Patients described the benefits of participating in CT in terms of receiving screening, learning about their own health, and improving their daily health routines [

38]. Therefore, the possibility of obtaining health benefits from participation in trials should be taken into account in order to encourage patients to participate in clinical trials [

39], especially in Poland, where it is the most frequently declared reason for interest in CTs.

The performed research has found a relationship between the reasons for interest in clinical trials and the family financial situation. People from the poorest families were less likely to indicate altruistic reasons, and more often to financial altruism. In comparison to people with a significantly high financial status, people with low status were more likely to express their intention to participate in clinical trials. People with a lower financial status may treat participation in clinical trials as an opportunity to improve their financial situation, which may explain their greater willingness to participate. Research conducted in the U.S. indicates that people with lower education and the unemployed are more likely to perceive participation in research as a way to obtain additional financial resources. For the unemployed, the economic benefits remain crucial, while they are less likely to perceive the social aspects of participation [

38]. In addition, monetary compensation as a major motivator for participation in phase I trials was less valued by healthy volunteers with higher incomes and education [

40] It is also worth noting that healthy volunteers who were driven by financial motives took part in more clinical trials. This suggests that the financial compensation may encourage them to participate repeatedly, which is worth considering when recruiting for research [

13].

On the other hand, the literature indicates that people with low incomes and lower education are less willing to participate in clinical trials and are less likely to be asked to participate in clinical trials compared to people with higher incomes and higher education [

41]. For example, in the case of CT, the existing literature has shown that lower levels of education and income in particular are associated with lower levels of health literacy, which may discourage referring physicians from informing people in these groups about the possibility of participating in the trials. This may be due to biased assumptions, such as the belief that people of lower socioeconomic status are unable to afford certain procedures or will not understand basic instructions, and thus will not follow strict study protocols [

42].

Working people were significantly more likely to express interest in participating in clinical trials compared to those who were not employed. This result suggests that professional activity may be associated with a greater propensity to participate in CT, which may result from, among other things, greater health awareness, financial stability or access to information about research. One study actually showed that people who were out of work for various reasons (e.g. retirement, disability, inability to find a job) were less likely to join the studies compared to those who were fully employed.[

41]. Moreover, research indicates that longer periods of unemployment are associated with worsening health-promoting behaviours and health outcomes, with the worst rates reported among those unable to work [

43]. These results highlight the existence of social inequalities that can affect the ability to participate in clinical trials, limiting access to them among people in a more difficult financial and professional situation.

Our research also shows greater openness to clinical trials among people living in rural areas, which is confirmed by other studies [

44]. Taking into account the Polish situation, one of the possible explanations for this relationship is limited access to highly specialized health care in rural areas, which may encourage residents to look for alternative treatment options, including participation in clinical trials. However, it is worth noting that despite the greater willingness to participate, logistical barriers, such as the need to travel to study sites, may actually limit the actual participation of rural residents in clinical trials [

45].

People in a stable relationship also have a significantly higher tendency to declare their intention to participate in clinical trials than single people. This may suggest that the support of a life partner influences a positive attitude towards research, e.g. by encouraging people to take care of their health or a greater sense of security in the context of participation in the study [

46]. These results indicate the importance of information activities addressed not only to potential participants, but also to their immediate environment. Incorporating the role of peer support into your recruitment strategies can increase the effectiveness of your research campaigns.

In addition, the female gender remained associated with a higher propensity to participate in clinical trials. However, it was a significant predictor only in models Health improvement and Altruistic reasons, where women had higher levels of CT-PHI. This may be due to their greater concern for health and more frequent involvement in pro-social activities. The lack of a gender effect in Model 1, on the other hand, suggests that both women and men are guided by similar considerations when it comes to financial motivation. It is worth noting here that despite regular contact with healthcare providers, women often face barriers that limit their participation in clinical trials. These barriers include increased stigma and economic and caring responsibilities that deprioritize their own health [

38,

47]. Therefore, it is extremely important to recognize women as a group interested in participating in clinical trials. Especially since the research has shown significant differences between the sexes in terms of the impact of social factors on the decision to participate in clinical trials. Women were more often than men guided by the opinions of relatives and researchers, as well as altruistic considerations [

48].

The last socio-demographic variable is age. The literature emphasizes that older people have different motivations, namely they expect to receive the best available treatment when participating in a study [

13,

38], which is confirmed by the results of our own research. Our analyses show that people aged 66 or over had the highest CT-PHI index value, and with age, the percentage of people who chose financial reasons decreased and the popularity of health reasons increased. Older people, regardless of motivation, showed the greatest openness to participation in clinical trials. Perhaps older participants are more likely to favour health benefits because they are more sensitive to the number and type of health problems that develop with age [

49], therefore confirmation of good health through screening may be of particular importance to them.

4.2. Approach to Clinical Trials and the Severity of Health Problems

As far as health factors are concerned, it has been shown that interest in clinical trials is associated with the severity of pain and symptoms of deterioration of mental health. People with more serious health problems were much more likely to declare their willingness to participate in a clinical trial. It's also important to recognize that chronic pain and depression can be challenging for recruitment and retention in clinical trials. In a literature review of clinical trial participation among patients with chronic pain, participants ranked professional relationships with study staff among the top three motivations (along with access to treatment and altruism) for study participation [

19]. Therefore, the declarative attitude of these people alone does not necessarily have to be an indicator of their staying in CT. In our own studies, people with moderate pain did not differ significantly in their intention to participate compared to people without pain, while people reporting severe or extreme pain were significantly more likely to report their willingness to participate in the studies [

50]. On the one hand, many patients with chronic pain have a high burden of disease and are dissatisfied with the effectiveness of available treatments, which is a factor related to the motivation to participate in clinical trials. On the other hand, patients with chronic pain often experience fatigue, insomnia, depression, anxiety, disability, and many have comorbidities that may have an impact on their willingness or ability to participate in clinical trials [

51,

52]. Certainly, effective communication and maintaining a professional environment are critical to optimizing engagement and supporting the successful delivery of clinical trials involving participants with chronic pain [

7].

At the same time, our own research has shown that people with average health ratings may be less interested in participating in studies, perhaps because they perceive their condition as stable enough not to seek additional intervention. The results of research in this area remain inconclusive as, on the one hand, patients who perceived themselves as in good/excellent health were more likely to participate in clinical trials than those who reported good/moderate/poor health [

53]. Other authors, however, did not note a relationship between the respondent's perception of their health and participation in the study [

54]. It may be that people with average health ratings have a hard time balancing the potential gains and losses of participating in studies, especially if they perceive their condition as being so good that they don't need any interventions at that moment.

The results of our own research also suggest that moderate difficulties in self-care may negatively affect the willingness to participate in studies. The degree of functional independence can affect an individual's ability to participate in clinical trials, and moderate difficulty can be a barrier to deciding whether to participate.

4.3. Approach to Clinical Trials and the Use of Medical Care

People using both public and private health care had a significantly higher level of CT-PHI index than people using public care alone. This may mean that people with access to both healthcare systems are more likely to engage in clinical trials, perhaps because of more contacts with doctors and greater awareness of the possibility of participating in trials.

People who always followed medical recommendations had a significantly higher level of CT-PHI than those who rarely or never adhered to recommendations, in the case of altruistic motivation, adherence plays a less significant role. These results indicate that adherence may be an important predisposing factor for participation in clinical trials, which may result from the desire to take control of one's own health rather than being a passive recipient of medical services [

55] and from the experience of better contact with doctors. This may be because people who have high levels of adherence often experience better contact with their physician. When physicians empathically acknowledge patients' feelings and encourage them to pursue their treatment goal, patients show a reduction in anxiety symptoms and increased confidence in physicians' recommendations [

56]. The reverse effect is also possible– although studies on bias among clinicians referring patients for computed tomography scans are sparse, one qualitative study conducted among key stakeholders in several cancer clinics in the US found that clinicians were less likely to refer individuals whom they perceived as unlikely to adhere to the study protocol [

57].

4.4. Summary of Multivariate Analysis

Summarizing, the results show differences in the factors affecting CT-PHI levels depending on the motivation to participate in clinical trials. The largest number of relevant predictors were identified in Model 2, which may mean that individuals motivated by health reasons are most susceptible to the influence of a variety of demographic and health factors. In model 1 (financial motivations), socioeconomic factors played a greater role, while in model 3 the effect on CT-PHI was the least diverse, which may suggest that altruistic people make the decision to participate in studies in a more homogeneous way and less dependent on individual conditions.

4.5. Strenghts and Limitations

According to our best knowledge, the study is the first in Poland that analyses the attitudes of the general public towards clinical trials, not limited only to people currently facing the decision to accept an invitation to participate in a CT. A broad sample of respondents, including 2,050 individuals, allows for the generalization of the obtained results to the population of adult Poles using medical services. We also tested a short scale that can be implemented in future studies of this kind.

One of the main limitations of the study is its cross-cutting nature, which makes it impossible to determine cause-and-effect relationships. In addition, due to the self-reported nature of the data collected, there is a risk of errors resulting from the tendency of respondents to provide socially desirable answers (social desirability bias) [

58], particularly concerning the motivation to participate in clinical trials. An important limitation may also be the recruitment method, which was conducted online [

59], which may have resulted in an overrepresentation of individuals who are more digitally active. It was challenging to fully capture the clinical context. Participants were not asked whether they were currently or had previously participated in clinical trials, but we assume such cases were rare. Although the introductory text explained the concept of clinical trials, it did not differentiate that these also include Phase I trials involving the recruitment of healthy participants. However, the questions regarding the willingness to help others relate to this aspect.

It was assumed that health status might influence the perception of clinical trials, but the survey did not include space for a detailed medical interview. Here, self-rated health and responses to the EQ-5D-5L components provide a general characterization of health status without delving into whether the respondent has any medical conditions, their severity, or their specific nature. The survey was conducted two years after the pandemic, which may have contributed to a more positive attitude toward scientific research on new therapeutic methods than before—for example, in the context of vaccine development to protect against symptoms caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Future studies should consider analysing changes over time and tracking actual participation in clinical trials after initial interest is expressed. This would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms influencing participants' decisions.

5. Conclusions

The study revealed that more than half of respondents (56.3%) expressed their willingness to participate in clinical trials in the future, indicating a growing interest in this type of research. The primary motivation for participation was the prospect of improving health, suggesting that effective communication about potential therapeutic benefits could enhance patient engagement.

Analyses also showed that the decision to participate in clinical trials is influenced by socio-demographic factors. The introduction of the CT-PHI index allowed for a better understanding of perceived benefits and risks, highlighting significant differences depending on participants' primary motivation—whether health-related, financial, or altruistic. This underscores the need for diverse recruitment strategies tailored to the profiles of potential participants.

These findings emphasise the necessity of strengthening educational and informational efforts regarding clinical trials, as well as optimising recruitment processes by considering the diverse motivations of patients. This approach could contribute to increasing public trust in clinical research and improving participant engagement in clinical trials in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alicja Kozakiewicz, Joanna Mazur, Monika Szkultecka-Dębek, Maciej Białorudzki and Zbigniew Izdebski; Data curation, Joanna Mazur; Formal analysis, Joanna Mazur; Funding acquisition, Maciej Białorudzki and Zbigniew Izdebski; Investigation, Alicja Kozakiewicz and Joanna Mazur; Methodology, Joanna Mazur; Project administration, Alicja Kozakiewicz, Maciej Białorudzki and Zbigniew Izdebski; Software, Joanna Mazur, Maciej Białorudzki and Zbigniew Izdebski; Supervision, Joanna Mazur, Monika Szkultecka-Dębek and Zbigniew Izdebski; Validation, Alicja Kozakiewicz and Joanna Mazur; Visualization, Alicja Kozakiewicz; Writing – original draft, Alicja Kozakiewicz, Joanna Mazur, Monika Szkultecka-Dębek and Maciej Białorudzki; Writing – review & editing, Alicja Kozakiewicz, Joanna Mazur, Monika Szkultecka-Dębek, Maciej Białorudzki and Zbigniew Izdebski.