1. Introduction

1.1. Change the Systemic Narrative!

Traditional human-centered narratives and social imaginaries have been used as a primary framework for understanding the world and guiding our collective actions. However, these narratives often have harmful consequences for the environment, as they prioritize human interests over other living beings and the natural world. (Ivakhiv, 2013). Grounded in a biocentric perspective that recognizes the intrinsic value of non-human entities and the natural world as a whole (Naess A., 2009), this work advocates for the transformation of narratives, expectations and collective social imaginaries. Such a change aims to align these cultural constructs with a perspective that envisions harmonious coexistence between humanity and the environment. Given the shortcomings observed over 3,000 years of anthropocentric paradigms, adopting a biocentric, or even ecocentric approach appears to be a plausible path to fostering a sustainable and equitable future. By changing our stories, our collective expectations and our imaginations through films, animated films, video games and social networks, which are an integral part of the daily human experience, it becomes possible to reconfigure our worldviews (Smith & Johnson, 2022) (Lee & Kumar, 2023). This approach is based on the recognition of the inherent value of all living and non-living components, paving the way for a more inclusive and sustainable global narrative.

1.2. Man Is Still the Measure of the World!

In the 5th century BCE, the Sophist thinker Protagoras articulated the principle that “man is the measure of all things.” This foundational assertion situates humans as the central criterion for evaluating the paradigm in which they exist. According to this perspective, morals and laws are understood as human constructs, emphasizing that the creation of values and norms is inherently anthropocentric. Such values, under this framework, are seen as contingent on human society, with no existence independent of human interpretation and interaction (Guthrie, 1969) (Kerferd, 1981). If polytheistic religions were sometimes more integrative, monotheistic cults reinforced an anthropocentric vision by giving humanity a central role (Taylor B., 2016) (Nasr, 1968). The Renaissance period brought to the fore the anthropocentric idea of humans creating meaning and progress, thus moving away from the theological framework in favor of human reason. (Hankins, 2007). John McNeill shows how in the modern era the development of science, technology and the industrial age reinforced the idea that nature was present for the sole benefit of its exploitation by humanity (McNeill, 2001). In recent years, ecological concerns have prompted a gradual shift from anthropocentric paradigms toward more ecosystemic and biocentric perspectives. This emerging reevaluation challenges human-centered principles by advocating for approaches that emphasize the intrinsic value and interconnectedness of all living systems (De Lucia, 2013) (Grear, 2017) (Naess A., 1973) (Tallacchini, 1996). However, this Biocentric awareness is struggling to take hold, even in the face of evidence of the correlation between anthropocentric activity and the destruction of biodiversity. Numerous studies carried out during and after the confinement of the COVID-19 pandemic have shown, for example, that during confinement the levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) fell significantly, by 45 at 54%, in the atmosphere, due to the cessation of the exploitation of fossil fuels for cars and industries (Le Quéré, 2020) (Zeng N. e., 2020) (Liu, 2020). Due to the interruption of construction activities, emissions of fine particles PM2.5 and PM10 decreased by 31 to 43%. SPMs were also reduced by 15.9%, leading to a notable improvement in ocean water quality. (Lam, 2022) (Liu, 2020) (Zeng Y. &., 2021). In many cities, noise pollution has also decreased by 60 db (Sordello, 2020) (Forum., 2020). On the banks of certain rivers, where all human activities had ceased, a new life rich in biodiversity was observed. All over the world, an increase in the activity of insects, butterflies, bees, wild and urban animals have been observed during confinement (Bates, 2021) (Owens, 2021) (Woodley, 2021). Thus, for the first time, a global correlation was highlighted between the end of human activities and the rebirth of ecosystems. Recent research from the EEE field has also begun to address how technological systems and media interfaces can be redesigned to promote ecocentric values (Chen & Patel, 2024) (Rodriguez & Nguyen, 2022), further supporting the call for a paradigm shift in our collective imaginaries (Lee & Kumar, 2023).

1.3. Anthropocentrism: Overpopulation and Overexploitation of Resources!

Research on mitochondrial DNA has shown that for nearly 100,000 years, while humans were nomads, the population did not exceed 10 million individuals. (Cochran, 2009). It seems that tribal nomadism, like the movements of groups of numerous animals, quadrupeds, birds, marine mammals, insects, has allowed human beings to live together for more than 100,000 years in a tenuous balance with the rest of biodiversity.

Paleolithic hunter-gatherers did not seem anthropocentric and probably considered other species as their equal, like certain nomadic populations still present at the beginning of the 19th century. (Hayden, Complex hunter-gatherers and the evolution of social complexity., 2011) (Hill, 2011). The Neolithic period beginning in - 8,000 BC will have lastingly modified human society by introducing agriculture, sedentarism develops the notion of property and promotes awareness of hereditary transmission requiring descendants (Galor O. &., 2002). Wars are no longer clashes between tribes, but battles between nations, and the need to create powerful armies generate a pronatalist policy which often persists today. Humans who seemed naturally attentive to their ecosystem, particularly through shamanic rituals, are gradually detaching themselves from a wild nature that frightens them in order to constrain and control it (Rowthorn, 2010) (Zeder, 2008).

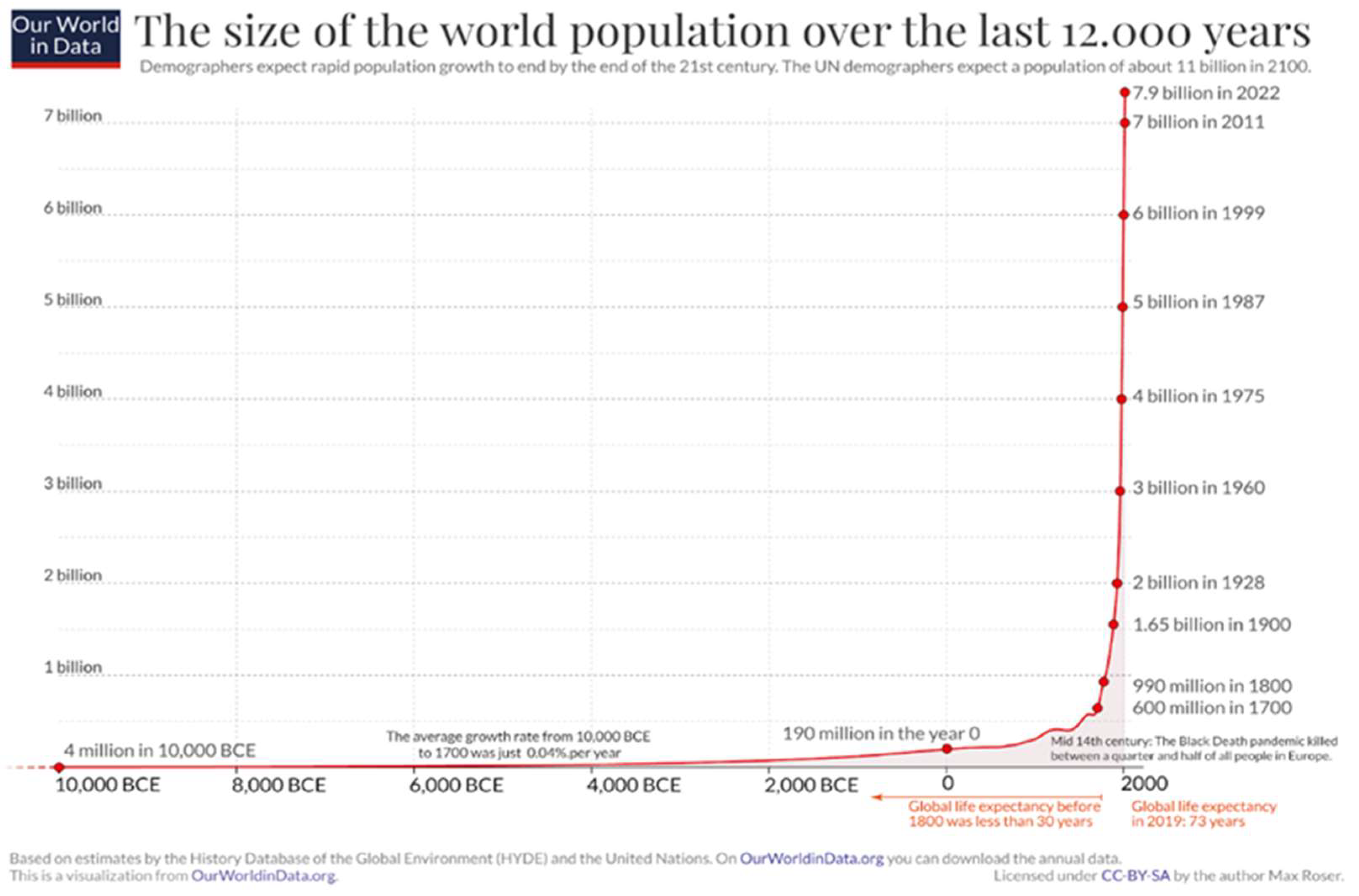

Historical records indicate that the world’s population was approximately 188 million in 1 CE, and it grew slowly until it reached a volume of 990 million people in 1800 at the dawn of industrialization. (McEvedy, 1978). In fact, the population growth was only 990 million individuals in 1800 years and 7.10 billion in just 225 years, reaching with the phenomenon known as “demographic transition” currently 8 billion individuals. (Canning, 2011) (Galor O., 2005).

The massive use of the principles of vaccination, antibiotics, hygiene and food diversification have allowed humanity to prosper exponentially over the last two centuries. (Institute. M. G., 2020) (University., 2018).

Nothing in the dizzying curve of the growth curve of humanity, neither wars, nor even major epidemics like the plague or the Spanish flu, nor Covid-19 have started the demographic growth of the human species. (Norrman, 2023).

Indeed, even pandemics are only difficult to observe in the dizzying growth curve of the human population, they have, in fact, no more effects than the bloodiest conflicts (

Figure 1).

Despite a certain decline in the Birth Rate that began in the 1970s (Lesthaeghe, 2010), the scientific developments of the last half century, correlated with capitalist, warlike populationist policies, as well as theological or dogmatic thoughts based on expansion, continue to produce population growth which follows the less optimistic forecasts of the second Meadow report 30- Year Update (Meadows D. H., 1972) (Meadows D. H., 2004) report whose projections have been updated with data provided by the UN in the World 3/2000 simulation model published by the organization: “Institute for Policy and Social Science Research” (Randers, 2004).

Indeed, reality has exceeded the projections of this 1972 report and its 30-Year Update regarding population growth. The world’s population will reach around 8 billion in 2022, much earlier than predicted in the pessimistic scenarios of the 1970s and 2000s.

In 2020, a study published in The Lancet by IHME projected that even with continued declines in birth rates, the world’s population could peak at around 9.7 billion in 2064. (Vollset, 2020).

Recent contributions have also illuminated the links between technological systems, resource exploitation, and population dynamics. For instance, Nguyen and Chen (Nguyen & Chen, 2023) integrated IoT and AI technologies for smart population monitoring in urban environments. Rodriguez and Lee (Rodriguez & Lee, Modeling energy consumption in urban environments: A non-anthropocentric approach., 2022) modeled energy consumption using non-anthropocentric frameworks, while Patel and Kumar (Patel & Kumar, 2024) assessed the impact of overpopulation on sustainable power systems. In another filed Zhang and Wang (Zhang & Wang, 2023) explored eco-innovations in urban infrastructure to mitigate resource overexploitation. These studies underscore the technological dimensions of our challenges, enhancing the need for a paradigm shift in our collective narratives, social imaginaries and infrastructures.

Published by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the World Population Prospects report projects that the global population could reach around 10.4 billion people by 2080. (United Nations, 2022). With potentially disastrous impacts on biodiversity and the climate. Paradoxically, the decline in the birth rate continues to frighten economists and reports from the World Bank and the World Economic Forum (WEF) further emphasize the socio-economic implications of demographic transitions, particularly for regions where rapid aging and reduction working populations could create economic challenges (Forum, 2022). The WEF’s Global Risks Report and World Bank reports also discuss the effects of depopulation in some countries. The WEF’s concerns are economic stimuli much more frightening for populations than those produced by the disappearance of biodiversity or climate change. They produce social imaginaries inclined to favor demographic growth to the detriment of a decline synonymous with loss of wealth and loss of economic comfort (Bank, 2022).

Anthropocentrism supports a social imaginary of power and control of humanity over all biodiversity as well as continuous growth supposed to ultimately conquer and subdue the limits of the universe (Crist, 2017) (Robin, 2013) (Moore, 2016). Even if this growth inexorably follows the law of economic entropy, according to which any exploitation of limited resources produces chaos (Silverman, 2022). Thousands of species of vertebrates and invertebrates are already permanently extinct, and millions still threatened with extinction, in what scientists like Gerardo Ceballos describe as the VI wave of extinction, the only one directly attributable to human activities. Humanity itself risks suffering from its irrational growth (Ceballos, 2015).

Afferents several thousand years old have enabled humans and other animals to survive thanks to primary cerebral mechanisms favoring reproductive principles and those of accumulation of resources (Kelley, 2002). But at the dawn of this new century and because he was able to thwart the mechanisms of his greatest benefactors and predators, Viruses and Bacteria, man should have been able to reassess the loop essential to the survival of all species (Estrella, 2013).

Even though the innate capacity of many mammals causes them to cease all reproductive activity and causes them to enter idle life cycles when resources decrease too quickly in relation to the size of their population. (Perry, 2020). Our anthropocentric social imaginations do not produce the stimuli to call into question our principles of demographic growth or consumption (Washington, 2020). All the reports produced by the IISD (International Institute for Sustainable Development), even the most optimistic, show an inevitable deterioration in the happiness of human beings because of their actions in future decades. (Report., 2024). It seems that, chained in its cognitive biases, optimism biases and SQB (status quo biases) (Sharot, 2011) (Samuelson, 1988), humanity is in a situation of inaction incapable of pragmatism and reflection. Recent study has shown that this optimism bias persists even when advanced technologies are deployed (Wang & Chen, 2022). Thus, SQB can become an issue when there is a crucial need for progress (Godefroid, Plattfaut, & Niehaves, 2023).

2. Development

2.1. From Anthropocentrism Towards a Biocentric Paradigm, Deep Ecology

The concept of Deep Ecology, an eco-philosophy derived from intuitive ethical principles, is stated by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess one of the founders of this environmental philosophy, as "biospheric egalitarianism in principle" (Naess A., 1973). It appears to have been first inspired by the birth of modern ecological consciousness, with the work of authors such as the conversationist Rachel Carson (Carson, 1962), the biologist Paul R. Ehrlich and his work “the population bomb” (Ehrlich, 1968) and the advocacy work of environmentalist David Brower (Eliot Porter, 1962). Deep ecologists view the failure of anthropocentrism through the prism of capitalism since the beginning of the industrial era (Naess A., 1989). They relate the risk that this exacerbated anthropocentrism, with its growth curve and exploitation of exponential resources, will lead biodiversity and therefore also humanity to possible extinction. The concept of Deep ecology, which is opposed in a sense to that of shallow ecology which is described as a form of superficial ecology of good conscience without real positive effects on the biosphere, has been iterated several times by other authors (Devall, 1985) (Fox, 1995).

In 1985 Devall and Sessions proposed the 8 essential non-anthropocentric rules of deep ecology. Among this, the first proposes a global non-anthropocentric approach to knowing how to live on earth and in the universe: “The well-being of human and nonhuman life on earth is of intrinsic value irrespective of its value to humans. » and another promotes a sustainable demographic decline “The flourishing of human and nonhuman life is compatible with a substantial decrease in human population. » (Devall, 1985). While the world had only 4 billion people, Arne Naess and several other leaders of deep ecology argue that the consumerist and materialist paradigm must be replaced and that growth behaviors continue, both economically and in terms of world population must cease by entering a global phase of decline (Naess A., 1973). From the 1980s, echoing the Meadows report, several Deep ecologists suggested that a total world population of 1.5 billion individuals should not be exceeded in order to guarantee, in a holistic vision of the world, that a global balance of ecosystems can be developed (Devall, 1985). Arne Naess, for his part maintains that the world should not have more than 100 million individuals to guarantee this balance (Bodian, 1982). In short, he proposes to return to the volume of humans present on earth for more than 40,000 years. If real efforts are made by the followers of environmental education of Ecopedagogy (Harding, n.d.). In regards of the latest alarmist reports on global warming, and the persistence of its effects on biodiversity (Pörtner, 2023) (Institute. W. R., 2023) (IPBES), 2023). As well as the global and exponential loss of other species due to human growth activities (Finn, 2023) (Birmingham., 2023); It is clear that the non-anthropocentric principles of Deep Ecology have not resonated in our modern societies for more than 50 years. We must now acknowledge its failure. It seems appropriate to us to encourage the use of media, such as cinema, video games or any other social media, relating but also major players in the founding of our common social imagination, in order to massively promote the generation of consciousness of the need to become non-anthropocentric, and to consider more humbly that we do not have a role of guardian of biodiversity, but that we must more simply step aside by considering the intrinsic value of each living creature.

2.2. Proposal of New Social Imaginaries

Social imaginaries designate all of the collective frameworks shared by a society to define its social world. These principles have been defined by thinkers like Cornelius Castoriadis or more recently Charles Taylor (Castoriadis, 1998) (Taylor C., 2004). The shared collective framework’s structure social interactions but they also produce collective visions of the future, a vision capable of changing or shaping the destinies of societies. The combination of norms, values, beliefs as well as all the symbols forming social interactions, these imaginations allow individuals to forge social relationships as well as a collective historical narrative (Garcia & Chen, 2023). Within social imaginations, media such as video games and films reproduce and disseminate values and beliefs (Murray, 2017) (Bogost, 2007) (Lee & Patel, Exploring media influence on social narratives. A computational analysis of video game content., 2022; Wang & Li, 2024), but they also forge anthropocentric images of the future by encouraging, as was the case during the industrial revolution, the imagination of a flourishing collective thanks to the emergence of technology and progress. (Taylor C., 2004). Our social imaginations are both the stimuli and the products of our anthropocentrism. Literature, films and video games in the context of climate catastrophe called cli-fi (abbreviation of climate fiction) today reflect the concerns of our societies regarding global warming or overpopulation. (Bogost, 2007). If they participate in public debate by reflecting collective priorities, they are generally anthropocentric: with a human point of view (Garrard, 2012). Many highlight issues based on the preservation of humanity, nature is, or an element of decor, or hostile. This is very rarely considered to have a significant existence (Garrard, 2012). These stories give us little to think that another non-anthropocentric future is possible. Stephen Hawking expressed deep concerns about the consequences of global overpopulation (Hawking, Brief Answers to the Big Questions., 2018), “By 2600, the world’s population will be shoulder to shoulder and electricity consumption will turn the Earth into a ball of fire. » (Hawking, Tencent WE Summit.

https://www.weforum.org, 2016). However, locked into an anthropocentrism perspective, it also created the stimuli of anthropocentric social imagination considering as the only prospect of survival of humanity, the colonization of other planets and the exploitation of all their natural wealth. (Hawking, Humanity must colonize space to survive., 2013).

Proposing the development of a non-anthropocentric systemic approach to promote the development of social imaginaries capable of reducing the impact of humans on the ecosystem and the biodiversity that shelters them, may seem ethically fragile. In a world where the majority of humans struggle to fight against social injustices, or quite simply for their survival in search of the most basic resources (Sen, 1999), It may seem inappropriate, even ethically inappropriate, to worry more about the disappearance of animal species, insects or even rivers or forests than about the misfortune of one’s fellow human beings. Malthus had pointed out the inconsistency of human expansionist nature in these terms: “If it is not curbed, the population increases in geometric progression. Subsistence only increases in arithmetic progression. (Malthus, 1798). Later, communism opposed its thinking with the miracle of industrialization supposed to provide more resources through the technology of agriculture and intensive breeding. Marx and Engels assert that social misery is not caused by demographic surpluses but by capitalist economic and social structures; they reject the idea that poverty is a natural consequence of the overexploitation of natural resources and anthropocentrism. (Marx, Die heilige Familie, oder Kritik der kritischen Kritik : Gegen die Philosophie der Elenden., 1845) (Marx, La Sainte Famille, ou Critique de la Critique de la Philosophie de la Religion de Hegel, 1975). Many political and theological dogmas still reject Malthusian and biocentric principles (Harris, 1994). Certain authors like Boserup argue in a progressive anthropological position that technological solutions will be implemented to avoid famine and destruction of biodiversity (Boserup, 1981). Moreover, like the philosopher Luc Ferry, ecologists critical of demographic growth and overconsumption are extremist reactionaries inclined to blame the failure of humanity on Third World countries, without considering the consumerism of the richest countries (Ferry, 1992) (Sagoff, 2008). He describes Arne Næss as anti-humanist, in fact claiming the supposed right to anthropocentrism (Ferry, 1992).

However, a non-anthropocentric approach does not reflect a lack of empathy. Indeed, the causal correlation between demographic overgrowth, resource consumption and ecosystem destruction can no longer be ignored. (Meadows D. H., 1972) (Meadows D. H., 2004). Rapid population growth intensifies resource strain and drives unsustainable energy consumption patterns, which in turn exacerbate environmental degradation (Doe & Smith, 2023). Finally, the modification of the general climate of our planet, which in view of the paradox described by Fermi is perhaps the only one in the universe to have seen life develop (Fermi, 1950) (Zuckerman, 1995), is probably an additional stimulus to the misfortunes hitting disadvantaged social classes, as well as minorities of all kinds (Kahn, 2005).

By precipitating the scarcity of resources essential to the survival of humanity, this has the effect of creating distensions, wars and withdrawals of identity, community and nationalism (Homer-Dixon, 1999). Recalling that the world’s two greatest conflicts took place during resource abundance, what will happen to empathy and compassion in a world with limited and diminishing essential resources, such as fresh water, as well as energy?

The construction of our anthropocentric social imaginations based on our cognitive biases of social psychology such as our heuristic bias of judgment and optimism (Kahneman, 2011) leads humanity to adopt a haughty attitude and an inability to objectify the imbalance that our growth induces. If some of these social imaginaries may have been effective in the natural environments which hosted human evolution, by allowing evaluation and gain in performance, then social and industrial revolution reducing inequalities and controlling a hostile part of nature, at least for certain populations (Harari, 2014), they prove unsuitable in the face of the issues of proportion and harmony that should inspire us today. It is precisely another future, another field of possibilities, non-anthropocentric, based on the balance and sharing of our current ecosystem that we would like to support and propose in the collective construction of new social imaginaries, through media like video games and cinema. The proposal of a humanity with a balanced volume compared to other species, respectful of the intrinsic value of other living beings, and wishing to use the benefit of its remarkable intelligence to remain invisible as humbly as possible in a controlled non-interaction with nature. ecosystem of which it is one of the elements.

3. Introducing a Framework for Assessing the Non-Anthropocentric Value of Media

The creation of a tool for evaluating the non-anthropocentric value of a media seems to us to be an essential step in the process of creating non-anthropocentric media capable of modifying social imaginations. This subjective semantic questionnaire is intended for the game director, movies director or writer and it can be used throughout the creation process or to assess the relevance of the non-anthropocentric impact of the media versus others. Media sharing or not these concerns. We designed the questionnaire following the recommendations of Osgood, Suci & Tannebaum who are references in this field (Osgood, 1957) (Suci, 1967). As well as the work of reference authors like DeVellis and Nunnally’s systemic processes for iterative evaluations thereof (DeVellis, 2016) (Nunnally, 1994).

3.1. Conception

The design of the semantic subjective form followed a structured approach grounded in psychometrics, measurement theory, and semantic analysis. By following the following steps: Finding the Non-Anthropocentric value

, defining the respective dimensions values

of

value. Definition and application of coefficients

of each dimension. Calculating the value of

is expressed in the following equation:

Developing questions for each dimension is an essential part of the process; each dimension is assessed through 5 semantic questions designed through the Schwarz recommendation (Schwarz, 1994) structured on an odd Likert scale from 0 to 5 (Likert, 1932) with differential semantic scales included (from “Never!” to “All the time!”). The questionnaire is thus structured in 6 dimensions containing a total of 30 questions. We conducted several iterative pilot tests with small groups to ensure the questions are cleared and the data collected is valid (Furr, 2011). Once the data is collected, we have proceeded to a factor analysis statistical validation (Cronbach, 1951) to ensure the questionnaire reliability measures the intended dimensions.

3.2. Dimensions and Coefficients

Initially the first of the dimensions that we included in our questionnaire corresponded to the dimension of of the “Fun Interest” of each media. Supported by a large scientific literature, we evaluated the relevance of each media in terms of interest to ensure its impact in terms of social imagination.

After our first iterations, it appeared to us that the “Fun interest” dimension of all the test questionnaires was high and corresponded to strong interest, which seems consistent with the fact that each evaluator chooses a media of which he has a strong knowledge. However, this high value introduced a bias into our evaluation by affirming that none of the media evaluated reached extreme values and suggesting that none of the media were totally anthropocentric. A media like the soccer simulation video game FIFA 18, for example, did not appear to be totally anthropocentric, even though nothing in this video game allows us to assert that it is not. Also, this dimension of “Fun interest” was deleted to retain only dimensions corresponding to an evaluation of non-anthropocentrism.

The definition of the dimensions of non-anthropocentric and biocentric value of media led us to the development of 5 interconnected dimensions through 25 questions. The first of these dimensions highlight the Ecocentric value of the media and its capacity to consider that all forms of life, human and non-human, have dynamic values and deserve equal respect. (Naess A., 1973) (Naess A., 1989). Thus, for Taylor each living organism is considered as a “teleological center of life” with its own value. (Taylor P. W., 1986). This first dimension is listed under the name: Ec, for Ecocentric Dimension.The second dimension: St, reflects the Sustainability values of the media by focusing questions on Global Warming, the destruction of the integrity of the biosphere and pollution by measuring to what extent the media alarms on these facts. This dimension evaluates the media’s desire to induce a reduction in the human footprint, by adjusting practices to minimize their negative impacts on other species and more generally on the planet. (Callicott, 1994).

The value of the third dimension Sd reflects the media’s desire to alarm the consequences of a constantly growing demographic (Devall, 1985) (Meadows D. H., 1972).

As well as on the impact and responsibility of each human being in the consumption of limited resources as well as in putting into perspective the anthropocentric perception of other species as resources in the service of humanity (Naess A., 1973) (Finn, 2023).

The fourth dimension explored is the Ma, questionnaire, for “Away From” AF, focuses on the supposed real direct effects of the media in producing positive consequences on biodiversity. For example, by instantly offsetting carbon production or by generating greater human discretion regarding biodiversity in gamified applications or games. This dimension responds to the need for immediate actions noted by biocentric or non-anthropocentric authors highlighting the need for direct and immediate action in the face of environmental crises and threats to biodiversity. (Lovelock, 2006) (Bookchin, 1982) (Jensen, 2006) (Taylor P. W., 1986) (Naess A., 1973).

Finally, the last of the dimensions evaluated by the questionnaire is the AI, for “Anthropocentric Insignificance”. This dimension rejects anthropocentrism from a perspective of decentering according to which humans are neither the center nor the summit of existence or value in the universe (Sagan, 1994) (Berry, 1999) (Morton, 2010).

Are the respective dimension values.

Using the systematic framework for creating subjective semantic questionnaire measurement scales proposed by DeVellis, emphasizing the need for multiple iterations (DeVellis, 2016). As well as the principles listed by Nunnally (Nunnally, 1994), we refined the values of each dimension during exploratory factor analysis to best reflect a balance in all the responses before our Cronbach reliability evaluation tests (Cronbach, 1951). These iterations made it possible to add the following coefficients to each of the dimensions:

3.3. Evaluation

A Cronbach reliability test (Cronbach, 1951) was carried out on data collected from 138 users of the 5D25Q subjective semantic questionnaire for evaluating the non-anthropocentric value of a media (Tabachnick, 2019) (Tavakol, 2011) (Field, 2013). A total of 3450 responses on a Likert scale from 0 to 5 (Likert, 1932). Scale reliability Statistics: Cronbach’ α scale= 0.966. Analysis of internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient; revealed excellent reliability of the scale with a coefficient α = 0.966, which indicates very high consistency of the questionnaire items (Tavakol, 2011).

4. Results

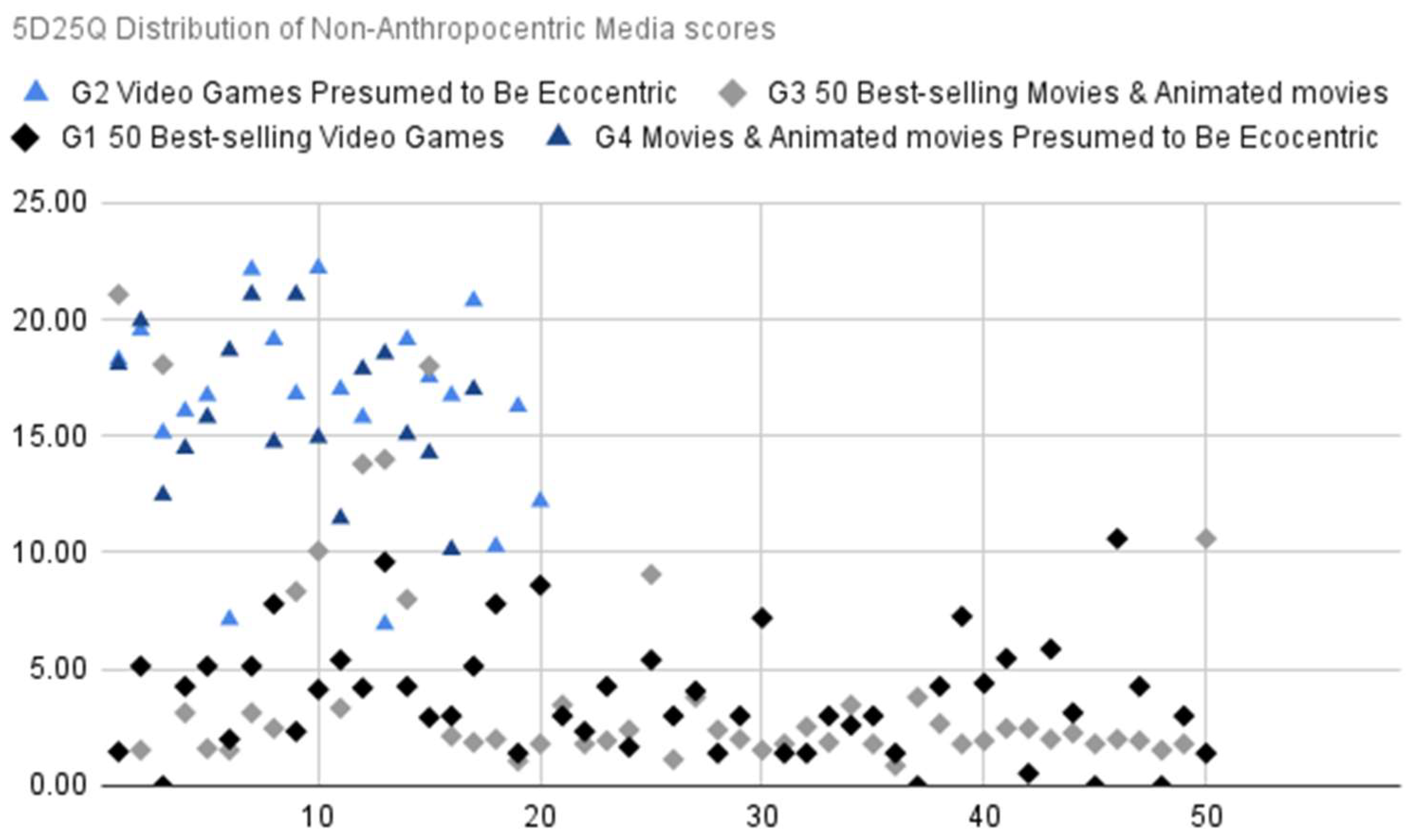

A total of 138 media works were evaluated using the 5D25Q questionnaire by paid adult participants (n = 242) via the online research platform Prolific Academic Ltd. The initial sample included 356 participants; however, a number of responses were excluded from the final analysis to ensure the reliability and integrity of the data. These exclusions were made on ethical and methodological grounds, as some responses appeared to have been generated randomly or failed to align with the expected evaluative patterns, indicating a lack of engagement with the questionnaire’s content. Several independent studies have reported superior data quality and participant attention on the alternative online platform Prolific, compared to that of CloudResearch, MTurk, Qualtrics and SONA (Douglas, 2023) (Albert, 2023). The distribution of these media was carried out in four groups: G1 corresponds to the list of the 50 best-selling video games since 1984. This continually iterated list was built on the aggregation of data produced by Wikipedia. G2 corresponds to the list of the 50 films and animated films, having generated the most revenue since 1993. This continually iterated list was also built on the aggregation of data carried out by Wikipedia. G3 corresponds to a selection of 20 supposedly non-anthropocentric video games published by the CNAP (Center for Non-Anthropocentric Play) on their website. Finally, the G4 group corresponds to a selection of 17 movies and animated movies for which the specialized press has noted the non-anthropocentric or biocentric character. The distribution of the results of these media is reported in the chart below (

Figure 2).

General data:

Score range: Values vary between 0 (lowest score) and 22.20 (highest score). These scores represent an underuse of the total scale, which ranges from 0 to 25. The absence of a high score can be revealed by the very low scores of the dimension

In fact, few media really have real AFK effects at this stage with an overall positive response score of only 0.58%.

Interpretation:

Concentration around low to average scores:

The Average (μ): 7.35 shows that many media studied have an overall anthropocentric character. Higher scores >20 but they are in the minority. This likely reflects a strong inclination of video games and movie media to represent the world from an anthropocentric point of view, with a more activist tendency of some of these media to be intentionally non-anthropocentric and biocentric. The Standard Deviation (σ): 6.63 indicates a concentration around the mean with a wide variation. These data illustrate a dominant anthropocentric balance with more limited attempts at non-anthropocentrism.

4.1. Score Distribution

For the G1 group representing the 50 Best-selling video games, the mean is (μ): 3.76 for possible scores range from 0 to 25. Suggest that most of the media evaluated are concentrated at the lower end of the range. This may reflect an overall anthropocentric bias in the most sold video game in the world, failing to prioritize biocentric or non-anthropocentric narratives. G1 Standard Deviation (σ): 2.50 reflects moderate variability, with most scores relatively consistent and close to the mean.

In the G2 representing the results of Video Games “presumed to be Non-Anthropocentric and Ecocentric” mean (μ): 16.3 3 is 65.2% of the maximum possible score (25) which suggests strong adherence to non-anthropocentric or biocentric principles. This is consistent with media explicitly designed to prioritize ecological and biocentric narratives. The Standard Deviation (σ): 4.28 reflects moderate to high variability, this spread could reflect a diversity of interpretation of non-anthropocentric and biocentric values in G2.

As for the G1 group G3, which represents the best-selling movies and animated movies the mean (μ): 4.36 indicates these films exhibit only a weak alignment with non-anthropocentric values. They are predominantly anthropocentric in nature. 95% Confidence Interval: Within \mu\pm2\sigma about 95% of the scores are expected to fall between −5.42 and 14, further demonstrate that most scores will cluster in the low range. G3 Standard Deviation (σ): 4.89 indicates substantial variability in the scores. Some films achieve moderate alignment with non-anthropocentric values, while others score near 0, showing minimal alignment.

The G4 score representing the group presumed to be non-anthropocentric and biocentric movies and animated movies span from 0 to 25, with a mean (μ): 16.2 2 positioned relatively higher on the scale compared to previous groups like G1 (μ): 3.76 and G3 (μ): 4.36, but close to the G2 (μ): 16.3. The average indicates a moderate alignment with non-anthropocentric and biocentric values. With 64.8% of the maximum score (25), this suggests that movies and animated movies of this selected group generally adhere to ecocentric narratives more than anthropocentric ones but still leave room for improvement. G4 Standard Deviation (σ): 3.21 21 indicates if the group is largely consistent in its alignment with non-anthropocentric themes, there are still some considerable variabilities.

The concept of Deep Ecology, an eco-philosophy derived from intuitive ethical principles, is stated by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess one of the founders of this environmental philosophy, as "biospheric egalitarianism in principle" (Naess A., 1973). It appears to have been first inspired by the birth of modern ecological consciousness, with the work of authors such as the conversationist Rachel Carson (Carson, 1962), the biologist Paul R. Ehrlich and his work “the population bomb” (Ehrlich, 1968) and the advocacy work of environmentalist David Brower (Eliot Porter, 1962). Deep ecologists view the failure of anthropocentrism through the prism of capitalism since the beginning of the industrial era (Naess A., 1989). They relate the risk that this exacerbated anthropocentrism, with its growth curve and exploitation of exponential resources, will lead biodiversity and therefore also humanity to possible extinction. The concept of Deep ecology, which is opposed in a sense to that of shallow ecology which is described as a form of superficial ecology of good conscience without real positive effects on the biosphere, has been iterated several times by other authors (Devall, 1985) (Fox, 1995).

In 1985 Devall and Sessions proposed the 8 essential non-anthropocentric rules of deep ecology. Among this, the first proposes a global non-anthropocentric approach to knowing how to live on earth and in the universe: “The well-being of human and nonhuman life on earth is of intrinsic value irrespective of its value to humans. » and another promotes a sustainable demographic decline “The flourishing of human and nonhuman life is compatible with a substantial decrease in human population. » (Devall, 1985). While the world had only 4 billion people, Arne Naess and several other leaders of deep ecology argue that the consumerist and materialist paradigm must be replaced and that growth behaviors continue, both economically and in terms of world population must cease by entering a global phase of decline (Naess A., 1973). From the 1980s, echoing the Meadows report, several Deep ecologists suggested that a total world population of 1.5 billion individuals should not be exceeded in order to guarantee, in a holistic vision of the world, that a global balance of ecosystems can be developed (Devall, 1985). Arne Naess, for his part maintains that the world should not have more than 100 million individuals to guarantee this balance (Bodian, 1982). In short, he proposes to return to the volume of humans present on earth for more than 40,000 years. If real efforts are made by the followers of environmental education of Ecopedagogy (Harding, n.d.). In regards of the latest alarmist reports on global warming, and the persistence of its effects on biodiversity (Pörtner, 2023) (Institute. W. R., 2023) (IPBES), 2023). As well as the global and exponential loss of other species due to human growth activities (Finn, 2023) (Birmingham., 2023); It is clear that the non-anthropocentric principles of Deep Ecology have not resonated in our modern societies for more than 50 years. We must now acknowledge its failure. It seems appropriate to us to encourage the use of media, such as cinema, video games or any other social media, relating but also major players in the founding of our common social imagination, in order to massively promote the generation of consciousness of the need to become non-anthropocentric, and to consider more humbly that we do not have a role of guardian of biodiversity, but that we must more simply step aside by considering the intrinsic value of each living creature.

4.2. Experimental Conclusions and Proposal for a Scoring Scale for the 5D25Q

Inside group G1 Mainstream media, might naturally prioritize human-centered narratives due to audience expectations. When G2 represents a group with a strong and consistent alignment with non-anthropocentric or biocentric principles. While there is some variability, most media perform well, positioning this group as a benchmark for ecocentric values. While G1 and G3 share low mean scores, the greater variability in G3 suggests more opportunities for films to achieve moderate alignment, albeit inconsistently. G4’s meaning is comparable to G2, indicates that selected presumed movies and animated movies are generally with similar values as the group of CNAP selected presumed non-anthropocentric video games. Which means that these media are sharing a similar focus on non-anthropocentrism.

Moderate Variability: High scores (up to 20.82) show that some media outlets are attempting to move beyond anthropocentric narratives, but these efforts remain isolated.

We perform a One-Way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, the high value of χ² = 70.3 suggests a substantial difference between groups. There is a significant variation in scores between the different groups, this difference is statistically significant with p-value < 0.001 which allows us to reject the null hypothesis which stipulates the equality of the medians of the groups. Finally, ε² = 0.517 indicates a moderate to large effect size. The difference between the groups is therefore significant, but also the difference between the groups is substantial. There are therefore notable differences between the G1, G2, G3 and G4 groups, and these differences are large enough to be considered significant from a statistical and practical point of view.

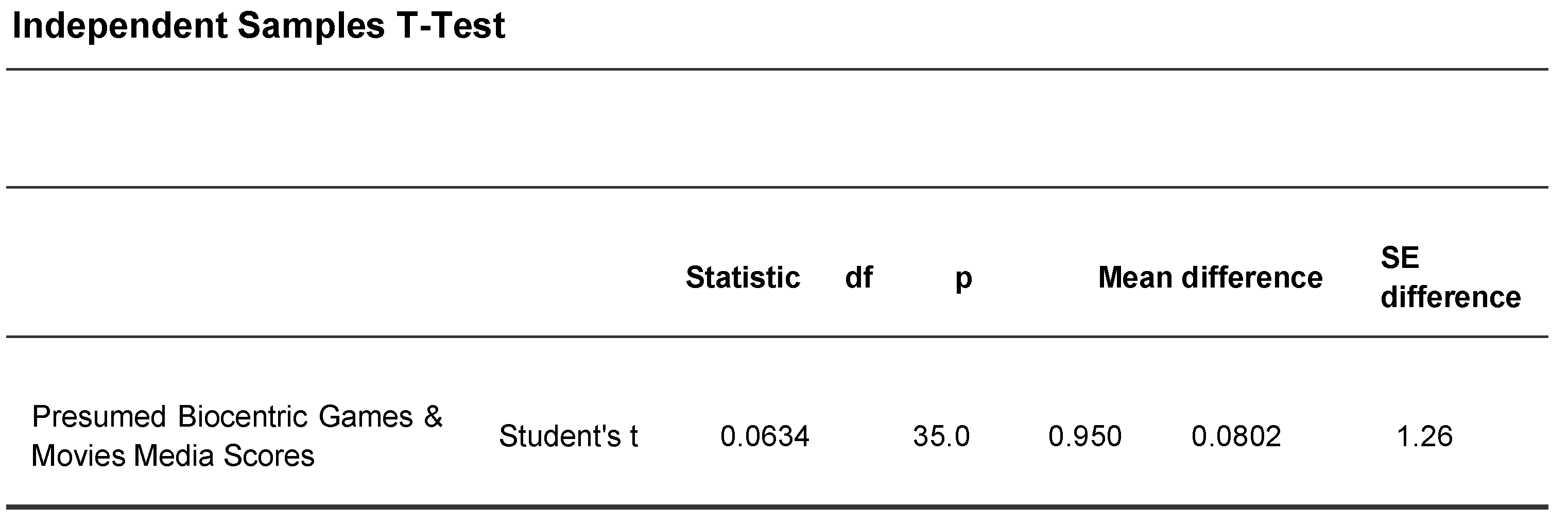

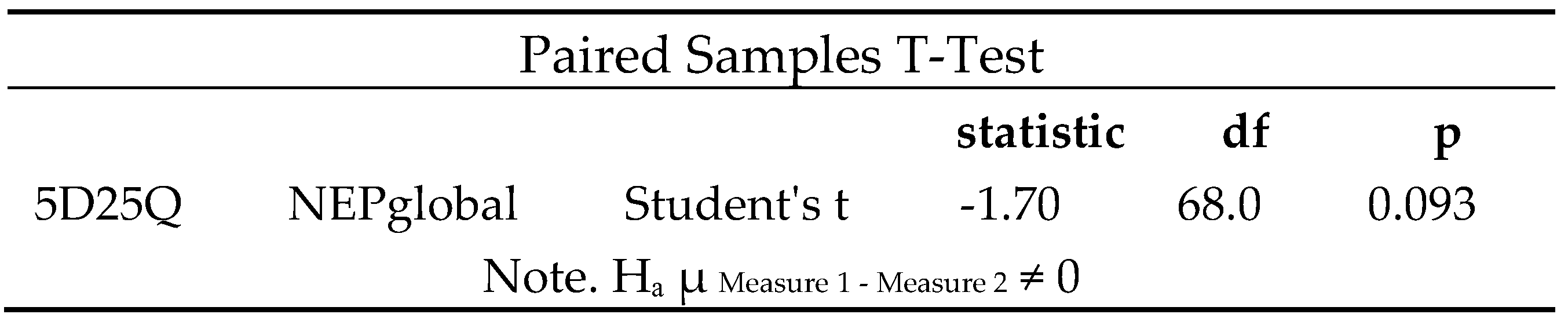

We then carried out an independent Samples T-test between the two groups G2 and G4 Media Scores which correspond to the two presumed Biocentric groups, to see if differences existed between the presumed biocentric group of video games and that presumed biocentric of Movies and animated movies (

Figure 3).

It appears that p-value 0.950 indicates no statistically significant difference between the presumed biocentric video games scores (group G2) and biocentric movies media scores (group G4). The null hypothesis (H0: μG2 = μG4) cannot be rejected, as there is insufficient evidence to suggest that the means of the two groups differ. The test provides strong evidence that the scores for presumed biocentric games (G2) and biocentric movies (G4) are not significantly different, supporting the idea that both types of media may be perceived as equally biocentric in terms of the evaluation criteria. This gives a good indicator of the markers of the biocentric and non-anthropocentric values of the expected scores in the 5D25Q questionnaire during the evaluations. The 2 groups scores may be perceived as moderate to highly non-anthropocentric.

A second Independent Samples T-test was also carried out on the two dependent variables G1 representing the 50 best-selling video games and G3 representing the 50 best-selling movies. The p-value 0.445 indicates no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups, the null hypothesis (H0: μG1 = μG3) cannot be rejected, and the test provide strong evidence that the groups scores may be perceived as equally very to anthropocentric.

4.3. Suggested Scale Range for the 5D25Q Questionnaire

Considering the average results of the groups, here is the suggested range for each category based on the scoring system provided:

Below 5 points: Very anthropocentric

This category represents media that are heavily anthropocentric and emphasize human interests and perspectives.

6–10 points: Anthropocentric

This category represents media that are still human-centered, but with some subtle inclusion of environmental or non-anthropocentric themes.

11–15 points: Moderately non-anthropocentric

This category includes media that gradually incorporate more biocentric or ecocentric values, though they still retain a focus on human perspectives to some extent.

16–22 points: Highly non-anthropocentric

This range represents media that strongly emphasize non-anthropocentric or biocentric narratives, reflecting a deep concern for environmental and non-human perspectives.

23–30 points: Non-anthropocentric activist

This category includes media that actively advocate for non-anthropocentric or biocentric values, often aiming to inspire environmental or social change, and showing a clear commitment to activism.

5. In-Depth Comparisons with NEP

Although several instruments exist to measure individuals’ecological worldviews or their connectedness to nature, there does not appear to be a standardized questionnaire specifically designed to assess the non-anthropocentric dimension or the ecological content of media. While instruments such as the Connectedness to Nature Scale (Mayer & Frantz, 2004) and the Nature Relatedness Scale (Nisbet, Zelenski, & Murphy, 2009) could serve as indirect benchmarks for our 5D25Q tool, these scales primarily focus on individual cognitive, emotional, and affective interpretations, and therefore do not offer a direct basis for comparison. In contrast, the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) Scale (Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, & Jones, 2000) measures the endorsement of ecological values and a non-anthropocentric worldview among individuals.The questionnaire consists of 15 items, divided into odd- and even-numbered statements. Agreement with the even-numbered items reflects alignment with the Dominant Social Paradigm (DSP), which corresponds to current anthropocentric social imaginaries. Conversely, agreement with the odd-numbered items indicates support for the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP), which is more closely associated with biocentric and ecocentric, non-anthropocentric perspectives.

The original NEP items have been slightly adapted to suit the analysis of media content in video games and cinema. The resulting reformulated items are as follows:

1- The media content suggests that humanity is approaching the ecological limits of the Earth’s capacity to support human life.

2- The media portrays the belief that humans have the right to alter the natural environment to fulfill their needs.

3- The media implies that human interference with nature frequently results in harmful or disastrous consequences.

4- The media conveys confidence that human ingenuity will prevent the Earth from becoming uninhabitable.

5- The media depicts humanity as significantly contributing to environmental degradation.

6- The media promotes the view that Earth has abundant natural resources, provided we develop them appropriately.

7- The media supports the idea that non-human life—plants and animals—possesses equal rights to exist as humans do.

8- The media reflects the belief that nature’s balance is robust enough to withstand the impact of modern industrial societies.

9- The media acknowledges that, despite their unique capabilities, humans remain subject to the fundamental laws of nature.

10- The media downplays the severity of the current ecological crisis, implying it has been largely overstated.

11- The media likens Earth to a spaceship, emphasizing its finite space and limited resources.

12- The media supports the anthropocentric notion that humans are destined to dominate the rest of nature.

13- The media represents the balance of nature as fragile and easily disturbed.

14- The media suggests that humans will eventually acquire sufficient knowledge of nature to fully control it.

15- The media warns that, if current trends continue, a major ecological catastrophe is likely in the near future.

As for the 5D25Q questionnaire, a Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Never”) to 5 (“All the time!”) was employed to evaluate each item (Likert, 1932). A total of 69 media previously used in the 5D25Q study were subsequently assessed with the modified NEP questionnaire—comprising 32 video games, 4 animated films, and 33 movies—by 155 paid adult participants via the same online research platform (Prolific Academic Ltd) used in earlier experiments and participants University. Although the initial sample included 223 participants, a subset of responses was excluded from the final analysis to ensure the reliability and integrity of the data.

Since the total number of NEP items is odd, resulting in an uneven distribution between paradigms, the NEP score was computed using 8 items while the DSP score was derived from 7 items. To address this imbalance and enable meaningful comparisons, a normalization algorithm was developed and expressed in percentage terms. This approach incorporates an inverted DSP value into a unified global NEP index, thereby representing a continuous measure of the biocentric orientation of the evaluated media.

We employ a normalization algorithm wherein DSP responses are inverted and integrated into a unified global NEP index, reflecting a continuous ecological orientation.

The final global NEP score ranges from –100 to 100, with values below 0 indicating a fully anthropocentric perspective consistent with the prevailing Dominant Social Paradigm, values above 0 (up to 100) reflecting a fully ecocentric stance, and a score of 0 representing a neutral, balanced position between NEP and DSP orientations, without a clear ideological leaning.

5.1. Results

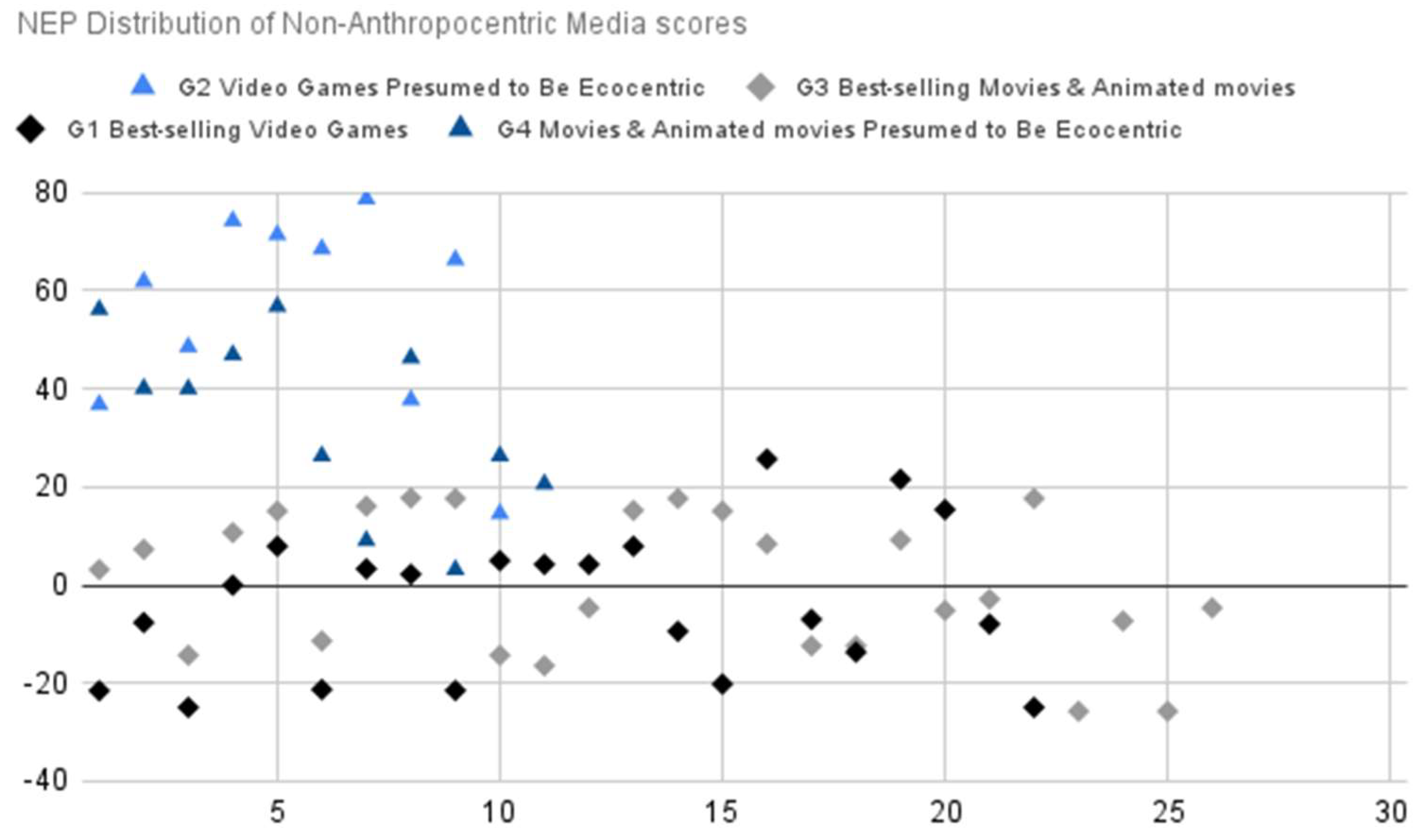

An analysis of the dataset reveals a considerable spread in the scores (

Figure 4). The observed values range from approximately –25.71 to about 78.73, resulting in a spread of roughly 104.44. With an overall mean near 12.5, the responses tend to be modestly skewed toward the positive end. Based on prior observations from the 5D25Q results, the data appear to reflect a median DSP value slightly above 0—likely around 10. This suggests that most media within groups G1 and G3 typically do not incorporate ecocentric perspectives, but rather display consumerist orientations strongly aligned with the DSP framework. Additionally, the high standard deviation indicates significant dispersion around the mean, reflecting marked variability among respondents. This distribution suggests that the underlying concept reflects a continuum of orientations, with some media showing a pronounced anthropocentric bias, while others lean strongly toward an ecocentric perspective. At this stage in the analysis, the dispersion observed in the distribution of Non-Anthropocentric Media Scores (NEP) (

Figure 4) closely mirrors that observed in the distribution of the 5D25Q (

Figure 5).

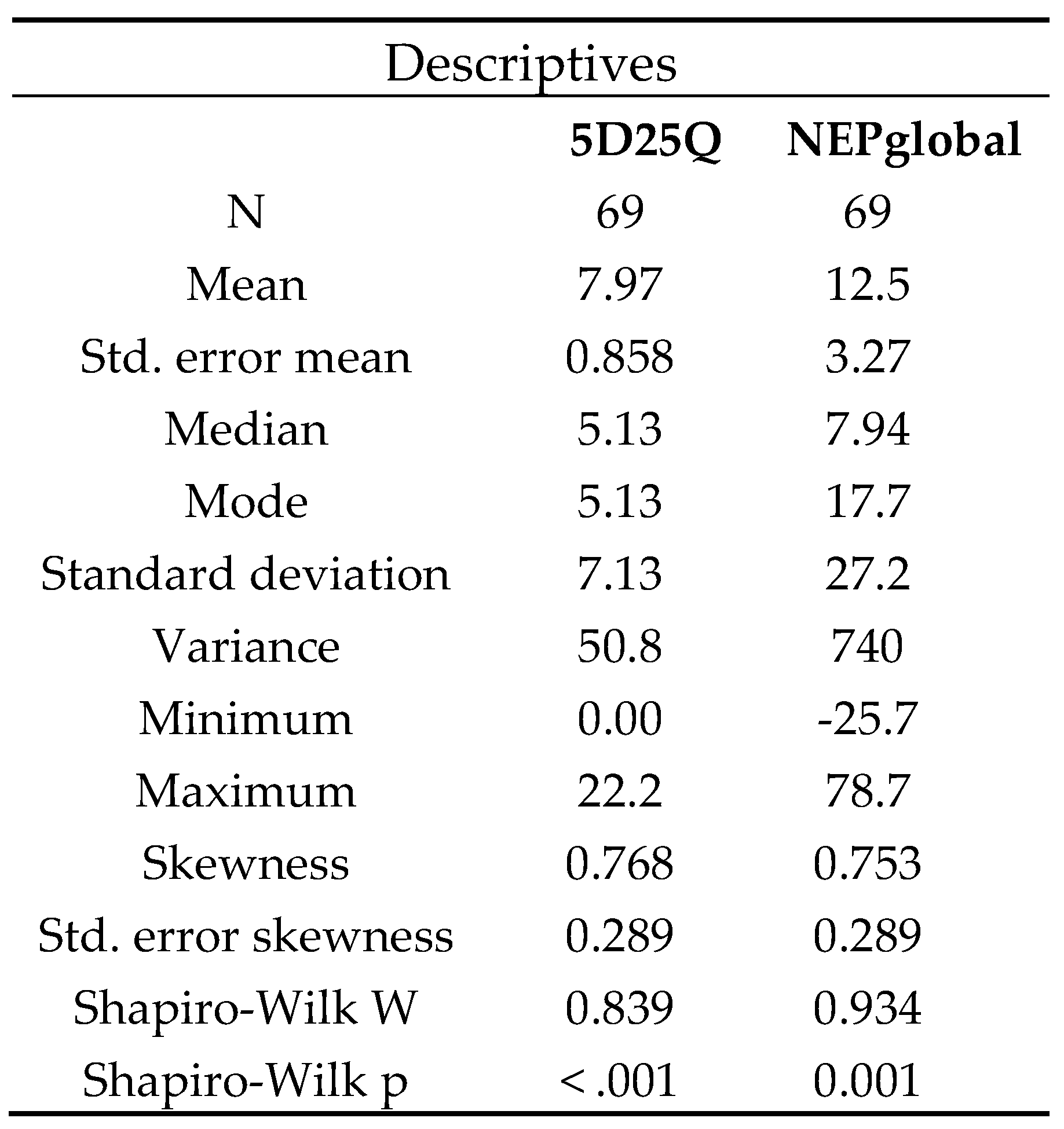

The descriptive statistics indicate that the 5D25Q variable, designed to assess the non-anthropocentric engagement of media content, has a mean of 7.97, a median of 5.13, and a standard deviation of 7.13. These figures suggest a moderate inclination towards ecocentric perspectives. In contrast, the NEPglobal measure, which encompasses both anthropocentric and ecocentric orientations, exhibits a mean of 12.5, a median of 7.94, and a notably higher standard deviation of 27.2. The NEPglobal scores range from –25.7 to 78.7, reflecting substantial variability. Negative values indicate media with strong anthropocentric characteristics, whereas positive scores denote a shift towards ecocentric evaluations.

Both variables display moderate positive skewness (approximately 0.75), and the Shapiro–Wilk tests (p < 0.001 for 5D25Q and p = 0.001 for NEPglobal) confirm significant deviations from normality in their distributions. These findings suggest that while a significant portion of the evaluated media tends to exhibit anthropocentric orientations, there is a notable minority that reflects ecocentric perspectives, contributing to a heterogeneous pattern of media engagement (

Figure 6).

Our results suggest that the two questionnaires, 5D25Q and NEPglobal, produce scores that do not differ statistically significantly. The paired samples t-test we conducted yielded a t-statistic of -1.70 with 68 degrees of freedom and a p-value of 0.093. With p >0.05, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the means of the two questionnaires are equal.

Results indicate similarity in the average scores of the two questionnaires. As the revised NEP questionnaire is considered the most widely used environmentmental values and attitude measure in the world (Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, & Jones, 2000), this consolidates the reliability of the results of our 5D25Q questionnaire of the non-anthropocentric nature of the media.

6. Questionnaire 5D25Q Conclusion

The evaluation outcomes of our subjective semantic questionnaire, developed to measure non-anthropocentric media values, indicate a high degree of reliability. Iterative refinements during its creation contributed to the development of a robust instrument capable of encompassing a wide range of anthropocentric and non-anthropocentric values across diverse media types, both interactive and non-interactive. The findings also demonstrate a consistent correlation in value assessments regardless of the media’s origins or the subjective evaluations previously conducted. The application of the 5D25Q questionnaire appears promising, offering potential for more detailed analyses of the biocentric dimensions of media, whether during the production process or post-release. The reliability of our questionnaire is further substantiated through its comparative analysis with the widely recognized New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale. The observed alignment in results between the two instruments underscores the robustness of our tool, particularly in its capacity to assess non-anthropocentric values within media content. Moreover, our questionnaire offers a tailored framework that is more attuned to the nuances of media analysis and the imperative of transitioning towards a non-anthropocentric paradigm. This paradigm shift is pivotal in reshaping social imaginaries and fostering a deeper ecological consciousness.

7. Discussion

If more and more video game companies seem concerned by sustainable development and the desire to clearly display a green ecological positioning to meet the expectations of some of their customers (Ischenco, 2024) (Fjællingsdal, 2023). In fact, it appears that very few of them compensate for their carbon production (Earth.Org., 2024). The same goes for the film and animation industries (Scott, 2017) (Bevan, 2019) (Ravettine, 2020). In many cases it seems that green washing could be described as shallow ecology, rather than deep questioning with the desire to promote a biocentricity, which could by nature be opposed to the anthropocentric narrative expectations of their customers. If real non-anthropocentric positions exist, in the field of video games, they are often the result of individuality or small indies studios of committed and activist independents (Pais, 2024) (Ruffino, 2021). In the field of movies and animated movies, the analysis of our results shows that some of the block buster’s clearly show a non-anthropocentric commitment. However, these successes only represent a tiny portion of the best-selling movies, and it is unlikely that they will revolutionize the paradigm of our social imaginations. If it seems important to us that the major players in the fields of interactive and non-interactive media take their responsibilities as creators of collective imaginations.

It is important to note that with the advent of social networks, social imaginations seem less collective than in the past. A growing body of research links social networks to societal fragmentation, reinforcing divisions within collective consciousness (Boyd, 2014) (Fayon, 2011) (Cardon, 2010) (Van Dijck, 2013). As digital interactions increasingly reshape societies into fragmented and tribal like structures, the necessity of reorienting collective social imaginaries toward a non-anthropocentric paradigm becomes even more pressing. This shift entails moving beyond the anthropocentric view that regards both living and non-living entities solely as resources for human consumption, emphasizing instead the intrinsic value and interconnectedness of all forms of life.

8. Materials

The 5D25Q Non-Anthropocentric Media Score Subjective Semantic Questionnaire is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) license, allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and adaptation, provided that appropriate credit is given to the author.

The questionnaire can be accessed and downloaded from ResearchGate at the following link:

Additionally, it is referenced under the DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.19804.71042, ensuring its traceability and proper attribution in academic and research contexts.

9. Conclusions

Current interactive and non-interactive AAA media seldom offers viable solutions to the ongoing crisis by significantly influencing collective social imaginaries. In fact, these media rarely present pathways that could rapidly halt the decline of biodiversity, facilitate the adoption of sustainable democratic practices, or promote a reduction in the consumption of natural resources, all while advancing a non-anthropocentric philosophy. Achieving such a utopian vision would require, at the very least, the widespread adoption of a biocentric approach, fostering a balanced paradigm of population management that accounts for the finite nature of resources and acknowledges the intrinsic value of all forms of life.

Most contemporary media remain entrenched in anthropocentric perspectives, often reflecting societal challenges such as urbanization, dystopian narratives, and consumer culture. Some media even entertain the notion of humanity’s future in extraterrestrial colonization, should the planet’s ecosystems fail. This trajectory suggests that humanity could perpetuate its patterns of exploitation and consumption of both natural resources and non-human life across distant environments, paralleling the detrimental consequences we are currently witnessing in biodiversity and climate degradation. Our hypothesis, supported by numerous scholarly sources cited within this work, asserts that humanity does not have the luxury of such an outlook. Adopting a biocentric posture may be a crucial factor in addressing the necessary paradigm shift confronting our species. This transition could be facilitated through the incorporation of novel, non-anthropocentric narrative frameworks that generate new collective social imaginaries capable of redefining our future and safeguarding biodiversity. Based on our results, the subjective semantic questionnaire designed to assess the non-anthropocentric value of media appears poised to assist influential stakeholders in shaping media that promotes biocentric equilibrium.

Future research should prioritize extending the evaluation of non-anthropocentric values to other influential media platforms, particularly social networks. These platforms play a pivotal role in shaping social imaginaries, yet their growing influence has often contributed to societal fragmentation and the emergence of tribalized communities with diverging perspectives. This underscores the urgency for a paradigm shift that integrates a non-anthropocentric philosophy into the design and conceptualization of such systems. Educating system designers about the broader social imaginaries they influence is crucial to this transformation.

Given the historical shortcomings of anthropocentric approaches, tools like the 5D25Q questionnaire hold significant potential for facilitating this shift. By promoting a coherent, non-anthropocentric vision, such frameworks can serve as a foundation for reimagining the future of collective social imaginaries and fostering more sustainable interactions between humanity and the natural world.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- IPBES. The nexus between climate change and biodiversity loss: Impacts, adaptation, and policy implications. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipbes.net (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Albert, D.A. Comparing attentional disengagement between Prolific and MTurk samples. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 20574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bank, W. World Development Report 2022: Finance for an Equitable Recovery. Washington, D.C. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Bates, A.E. Global wildlife responses to COVID-19 lockdowns. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2021, 5, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, T. The Great Work: Our Way into the Future; Bell Tower, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, R. The carbon footprint of the entertainment industry: Analyzing the impact of film and television production. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham., U.O. Birmingham., U.O. Exponential Biodiversity Loss Linked to Human Activities. 2023. Available online: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Bodian, S. Simple in Means, Rich in Ends - A Conversation with Arne Naess. 1982. Available online: https://openairphilosophy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/OAP_Naess_Int_Bodian.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Bogost, I. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames; MIT Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bookchin, M. The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy; Cheshire Books, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Boserup, E. Population and Technological Change: A Study of Long-Term Trends; University of Chicago Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens; Yale University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Callicott, J.B. Earth’s Insights: A Survey of Ecological Ethics from the Mediterranean Basin to the Australian Outback; University of California Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Canning, D. The causes and consequences of the demographic transition. PGDA Working Paper No. 79. 2011. Harvard School of Public Health.

- Cardon, D. La Démocratie Internet; Seuil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, R. Silent Spring; Houghton Mifflin, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Castoriadis, C. L’institution Imaginaire de la Société; Éditions du Seuil, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, G.E. Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Science Advances 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.H.; Patel, S. Non-anthropocentric design in cyber-physical systems: Implications for sustainable media and social change. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Green and Sustainable Computing (ICGSC); 2024; pp. 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, G. The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution; Basic Books, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Crist, E.M. The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection. Science 2017, 356, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, V. Beyond Anthropocentrism and Ecocentrism: A Biocentric Approach to Environmental Law. Journal of Environmental Law and Practice 2013, 12, 189–215. [Google Scholar]

- Devall, B. Deep Ecology: Living as If Nature Mattered; Gibbs Smith, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Doe, J.; Smith, A. Impact of demographic growth on resource consumption and environmental sustainability: An IEEE perspective. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing 2023, 9, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, B.D. Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earth.Org. The Environmental Impacts of the Video Game Industry. 2024. Available online: https://earth.org/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ehrlich, P.R. The Population Bomb; Sierra Club/Ballantine Books, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot Porter, D.B. In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World; Sierra Club/Ballantine Books, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Estrella, M. The Role of Ecosystems in Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations University Press, 2013; pp. 1–486. [Google Scholar]

- Fayon, D. Les réseaux sociaux menacent-ils nos libertés individuelles? Terminal 2011, 108-109, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermi, E. What Is the Evidence for the Existence of Extraterrestrial Civilizations? Conference on the Origin of Life. University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry, L. Le nouvel ordre écologique: L’arbre, l’animal et l’homme; Éditions Grasset, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, C.P.-D. The Global Loss of Biodiversity Is Significantly more Alarming than Previously Suspected. Biological Reviews 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjællingsdal, K.S. Gaming Green: The Educational Potential of Eco—A Digital Simulated Ecosystem. Frontiers in Psychology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum, W.E. The Global Risks Report 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Forum., W.E. Forum., W.E. COVID-19 and Its Effects on Global Noise Levels. 2020. Available online: www.weforum.org/stories/2020/05/covid19-lockdowns-silenced-urban-noise-now-its-coming-back/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Fox, W. Toward a Transpersonal Ecology: Developing New Foundations for Environmentalism; State University of New York Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Furr, M. Psychometrics: An introduction; SAGE Publications, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Galor, O. Natural selection and the origin of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2002, 117, 1133–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galor, O. 93. In From stagnation to growth: Unified growth theory. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Durlauf, P.A., Ed.; Elsevier, 2005; pp. 171–293. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.L.; Chen, F. Digital storytelling and its impact on social values: A study of interactive media. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Digital Media Technology (ICDMT), 2023; pp. 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, G. Ecocriticism, 2nd ed.; Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Godefroid, M. , Plattfaut, R.; Niehaves, B. How to measure the status quo bias? A review of current literature. Management Review Quarterly 2023, 73, 1667–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grear, A. Human Rights and New Nature Relations. Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 2017, 8, 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, W.K. The Sophists; Cambridge University Press, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hankins, J. The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Philosophy; Cambridge University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harari, Y.N. Sapiens: A brief History of Humankind; Harvill Secker, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. Deep Ecology in the Holistic Science Programme. Available online: https://www.schumachercollege.org.uk (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Harris, M. Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture; Random HouseL, Random HouseL. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S. Humanity Must Colonize Space to Survive. Available online: https://www.space.com/21055-hawking-humanity-colonize-space-survival (accessed on 13 April 2013).

- Hawking, S. Tencent WE Summit. 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org (accessed on 13 April 2013).

- Hawking, S. Brief Answers to the Big Questions; Bantam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, B. Complex Hunter-Gatherers and the Evolution of Social Complexity; T. C. Price & J. Brown, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, B. &. Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals and Mobilization. In Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals and Mobilization; Hayden, B., Ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2011; pp. 334–350. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, B. Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals and Mobilization; Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, K.W. Hunter-Gatherer Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation; Ember, M.R., Ember, C.R., Eds.; Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Homer-Dixon, T.F. Environment, Scarcity, and Violence; Princeton University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Institute., M.G. Institute., M.G. Life Expectancy more than Doubled over the Past Century. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Institute., W.R. Institute., W.R. State of Climate Action 2023: Biodiversity at the crossroads. 2023. Available online: https://www.wri.org (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ischenco, A. Gamification in Sustainable Development: Applying Game Design to Motivate Environmental Action; UC Berkeley International & Executive Programs, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ivakhiv, A.J. Ecologies of the Moving Image: Cinema, Affect, Nature; Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, D. Endgame, Vol. 1: The Problem of Civilization; Seven Stories Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, M.E. The death toll from natural disasters: The role of income, geography, and institutions. The Review of Economics and Statistics 2005, 87, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, A.E. The neuroscience of natural rewards: Relevance to addictive drugs. Journal of Neuroscience 2002, 22, 3306–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerferd, G.B. The Sophistic Movement. In The Sophistic Movement; Kerferd, G.B., Ed.; Cambridge University Press, 1981; Volume 84. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, K.S. Public health co-benefits of PM2.5 reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of fifteen cities worldwide. Environmental Research 2022, 204, 111897. [Google Scholar]

- Le Quéré, C. e. Temporary Reduction in Daily Global CO2 Emissions During the COVID-19 Forced Confinement. Nature Climate Change 2020, 10, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.F.; Kumar, R. Towards a sustainable digital future: Evaluating media technologies through an ecocentric lens. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing 2023, 8, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.F.; Patel, S. Exploring media influence on social narratives. A computational analysis of video game content. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2022, 13, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesthaeghe, R. The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review 2010, 36, 211–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology 1932, 140, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. e. Near-Real-Time Monitoring of Global CO2 Emissions Reveals the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, J. The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth is Fighting Back – and How We Can Still Save Humanity; Penguin Books, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Malthus, T.R. An Essay on the Principle of Population, 1st ed.; J. Johnson, 1798. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Die heilige Familie, oder Kritik der kritischen Kritik: Gegen die Philosophie der Elenden; Verlag von Otto Meissner, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. La Sainte Famille, ou Critique de la Critique de la Philosophie de la Religion de Hegel; Éditions Sociales, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- McEvedy, C. Atlas of World Population History; Penguin Books, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, J.R. Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World (The Global Century Series); WW Norton & Company, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update; Chelsea Green Publishing, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.W. Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism; PM Press: Oakland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, T. The Ecological Thought; Harvard University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace; MIT Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement. A Summary. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy (D. Rothenberg, Trans.); Cambridge University Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. The Ecology of Wisdom; Catapult, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, S.H. Man and nature: The spiritual crisis of modern man. 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Chen, G.H. Smart sensing for sustainable population monitoring: Integrating IoT and AI for environmental management. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrman, K.-E. World population growth: A once and future global concern. World 2023, 4, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, C.E. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, B. The positive and negative impacts of COVID on nature. Smithsonian Magazine. 2021. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Pais, F. Exploring More-Than-Human Worlds and Becoming with Living and Non-Living Entities Through Play; Gray, C., Ciliotta Chehade, E., Hekkert, P., Forlano, L., Ciuccarelli, P., Lloyd, P., Eds.; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Kumar, R. Renewable energy and population dynamics: Assessing the impact of overpopulation on sustainable power systems. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2024, 15, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.A. Evolution of innate behavioral strategies through competitive population dynamics. PLOS Computational Biology 2020, 16, e1009934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.O. Climate change and biodiversity: Synergies, challenges, and solutions. Nature Climate Change 2023, 13, 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Randers, J. Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse, Envisioning a Sustainable Future; Chelsea Green Publishing: 2004.

- Ravettine, T. Sustainable animation practices: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Animation Studies 2020, 13, 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Report., W.H. Report., W.H. World Happiness Report 2024: Assesses Happiness Across Generations. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. 2024. Available online: https://sdg.iisd.org/news/world-happiness-report-2024-assesses-happiness-across-generations:contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}.

- Robin, L. Anthropocene: The human era and its environmental consequences. Environmental History 2013, 18, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Lee, E. Modeling energy consumption in urban environments: A non-anthropocentric approach. Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Sustainable Energy Technologies (ICSET), 2022; pp. 112–119.

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Lee, E.F. Modeling energy consumption in urban environments: A non-anthropocentric approach. Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Sustainable Energy Technologies (ICSET), 2022; pp. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Nguyen, T.P. Reimagining media narratives for sustainability: A cybernetic approach. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2022, 52, 556–568. [Google Scholar]

- Rowthorn, R. &. Property rights, warfare, and the Neolithic transition. TSE Working Paper, No. 10-207. 2010.

- Ruffino, P. Independent Videogames: Cultures, Networks, Techniques, and Politics; Routledge: 2021.

- Sagan, C. Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space; Random House: 1994.

- Sagoff, M. The economy of the Earth: Philosophy, Law, and the Environment; Cambridge University Press: 2008.

- Samuelson, W. Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 1988, 1, 7–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. Asking Questions: The Definitive Guide to Questionnaire Design; Jossey-Bass: 1994.

- Scott, M. Greening the screen: Environmental sustainability in the global film industry. Film Quarterly 2017, 70, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Alfred, A. Knopf: 1999.

- Sharot, T. The Optimism Bias: A Tour of the Irrationally Positive Brain; Pantheon Books: 2011.

- Silverman, M. Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and ecological economics. Portland State University Economics Working Papers, No. 54. 2022. Available online: https://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/37815.

- Smith, A.B.; Johnson, C.D. Integrating ecocentric perspectives in digital media design: A framework for sustainable ICT. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 12345–12356. [Google Scholar]

- Sordello, G. e. Positive global environmental impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Environmental Science & Policy.

- Suci, G.J. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: 1967.

- Tabachnick, B.G. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: 2019.

- Tallacchini, M. Environmental Ethics: Nature as Law, Nature as Rights. International Journal for Philosophy of Law 1996, 9, 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B. The Greening of Religion Hypothesis (Part One): From Lynn White, Jr and Claims That Religions Can Promote Environmentally Destructive Attitudes and Behaviors to Assertions They Are Becoming Environmentally Friendly. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature & Culture 2016, 10, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. Modern Social Imaginaries; Duke University Press: 2004.

- Taylor, P.W. Respect for Nature: A Theory of Environmental Ethics; Princeton University Press: 1986.

- United Nations, D.O. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/World-Population-Prospects-2022.

- University., M. University., M. Why Has the World Population Grown so much so Quickly? 2018. Available online: https://lighthouse.mq.edu.au.

- Van Dijck, J. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media; Oxford University Press: 2013.

- Vollset, S.E. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: A forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Chen, L. Investigating status quo bias in adaptive energy management systems. Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), 2022; pp. 987–994. [CrossRef]