1. Introduction

Lane detection (LD), the process of recognizing lanes as approximated curves, is a foundational task in the realm of autonomous driving, whereby the detector aims to perceive the accurate shape of each lane in an image captured by a front-mounted camera. In the context of autonomous driving or even human-driven vehicles equipped with advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), accurate lane detection helps keep the vehicle within its proper lane.

Our objective is to develop an interactive lane detection model similar to SAM [

1] (Segment Anything Model). Firstly, when encountering complex road conditions where the model fails to recognize, it can accept human feedback in natural language to weight the model’s spatial attention or can be prompted by a parallel large visual language model. Secondly, autonomous driving requires a large number of manual annotations for training. Before manual annotation, images are auto-annotated by a pretrained LD model, which often underperforms in corner cases that follow a long-tail distribution. If annotators could directly indicate several keypoints of the lane to the model and the model could autoregress complete high-quality lane based on these semantic cues, it would significantly reduce annotation costs. However, existing lane detection models neither possess such interactive capabilities nor can they be prompted. To address these issues, we train the LD model using the language model training method to explore the improvements gained by the model receiving a few prompts.

Existing lane detection methods, whether based on line-anchor regression, segmentation, or keypoint detection, rely on convolutional neural networks (CNN) and spatial attention mechanisms. Firstly, the locality of CNNs makes it difficult to capture the long-range dependencies of lanes across the entire image. Secondly, traditional methods lack the interactive capabilities of language models and cannot specify the position of spatial attention weights in the feature map in corner cases. To address these issues, we convert visual and semantic information into a token sequence, utilizing a cross-attention mechanism, in which queries are language tokens and keys and values are visual tokens. Therefore, the model can determine the location where attention is applied on the feature map.

Inspired by [

1,

2], thanks to Lane2Seq [

3], this study proposes a promptable framework, called

LaneLM, to LD that differs from the mainstream approaches. Similar to pioneer work [

3,

4], our method is based on two intuitions: First, if the detector knows where lanes are, we just need to teach it to read them out so that we can refine the location of keypoints in this context. If an initial set of keypoints, which are discretized into tokens, is given as prompt for each lane , the detector should generate holistic sequence of the lane respectively in a manner of causal language modeling. Second, since language models are few-shot learners[

5], why not use a small number of prompts to enhance the LD performance in corner cases? Besides, we can utilize the instruction-following ability of language models to make LD models follow simple instructions. Furthermore, LaneLM avoids customized heads, relying instead on direct keypoint token classification.

In summary, we make the following contributions:

It is the first attempt to treat the LD task as visual question answering (VQA). Our work paves the way toward unification for language modeling and lane detection.

We develop an interactive lane detection framework that can accept prompts with semantic information to guide the visual modality.

With a small number of keypoint prompts (e.g. 4 adjacent points, about 7% of the total length of each lane), LaneLM easily outperforms the previous SOTA method by 1.09%.

Figure 1.

Corner cases in lane detection. There are many challenging scenarios in the lane detection task, such as at night, with severe occlusions, resulting in no visual clues for visual task.

Figure 1.

Corner cases in lane detection. There are many challenging scenarios in the lane detection task, such as at night, with severe occlusions, resulting in no visual clues for visual task.

2. Related Works

2.1. Traditional Lane Detection Methods

The mainstream approaches can be classified into the following categories:

1) Anchor-based methods. The network structure designing is similar to object detection but [

6,

7,

8,

9] use line-anchor instead of anchor box as lane prior and regress offsets between sampled points and predefined anchor points. At inference time, Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) is applied as post-processing. These methods take both speed and accuracy into account. Nevertheless, these methods struggle to detect lanes with complex topology, the predefined line anchor with a fixed shape fails to serve as a correct reference.

2) Segmentation-based methods [

10,

11,

12] pixel-wisely predict each lane and assign different lanes to different channels, respectively, so that they are flexible enough to detect lanes with complex topology. Segmentation-based methods can be unified with other segmentation tasks. For example, a single model can be used to segment lanes and parking slots simultaneously. However, these methods, which require heuristic post-processing to decode the segmentation map, are not accurate or fast enough compared with anchor-based methods.

3) Keypoint-based methods. [

13,

14,

15] treat each lane as a set of keypoints and then binarily predict foreground points and the background. Compared with segmentation-based methods, keypoint-based methods reduce the complexity of foreground classification. They can handle complex topological structures while also considering real-time performance. However, the post-processing of keypoint-based methods still remains an issue. Researchers have developed complex clustering and filtering methods to distinguish lanes in the same image.

4) Row-wise methods [

16,

17,

18,

19], which rasterize lanes in the image and row-wisely predict the grid occupation for each lane, are simple yet effective. These methods develop the row-anchor representation for lane detection instead of a line-anchor. However, side lanes of the Y-shape, often nearly horizontal, make lane classification difficult. These methods can achieve a high inference speed and easily surpass the methods described above in terms of real-time performance while getting comparable results.

5) Curve-based methods [

20,

21,

22,

23] formulate each lane into a parametric equation, such as polynomials or Bézier curves, predicting the parameters. Benefiting from holistic representation of the lane, inherently eliminate occlusions. These methods predict lanes in an end-to-end manner, require no post-processing but their performance still lag behind other methods by a large margin.

The current SOTA CLRerNet [

9], based on the previous SOTA CLRNet [

6], has introduced the LaneIoU loss for training, taking into account the topological structure of the lanes. CLRNet [

6] integrates high-level features with low-level features that contain more spatial information, and achieves impressive results through the application of a spatial attention mechanism. Previous SOTA GANet [

13] use DCN [

24] to associate keypoints in the same lane with their belonged start points. In summary, traditional LD methods focus only on the spatial information and topological structure of lanes.

2.2. Autoregressive Modeling for Vision

In light of the aforementioned methods, spatial information of lane perception in 2D space is well-exploited. We aim to borrow semantic-aware capability from Natural Language Processing (

NLP) so that our model can capture contextual dependency of input sequences and produce high-quality output. . Autoregressive (

AR) model has found great success in motion prediction [

25,

26], autonomous driving [

27], NLP [

5,

28,

29] and visual tracking [

30,

31]. Apart from Lane2Seq [

3], little work in lane detection focuses on this promising paradigm that utilizes temporal or semantic information, and none of these traditional LD methods are interactive.

Pix2Seq [

4] quantizes bounding boxes into language tokens to describe the objects. Therefore, the model can learn to ground the language tokens on visual observation. Following Pix2Seq, ARTrack [

30,

31] firstly adopts this framework in visual tracking. Flamingo [

28] explores the few-shot learning capability of visual language models and it is visually-conditioned AR language model, i.e. a visual encoder is used to perceive the information in images while a language model is utilized to refine the visual information at the semantic level in the few-shot context and employ a connector to bridge the visual encoder and the language decoder. The same architecture can also be found in many VQA models [

29,

32,

33,

34].

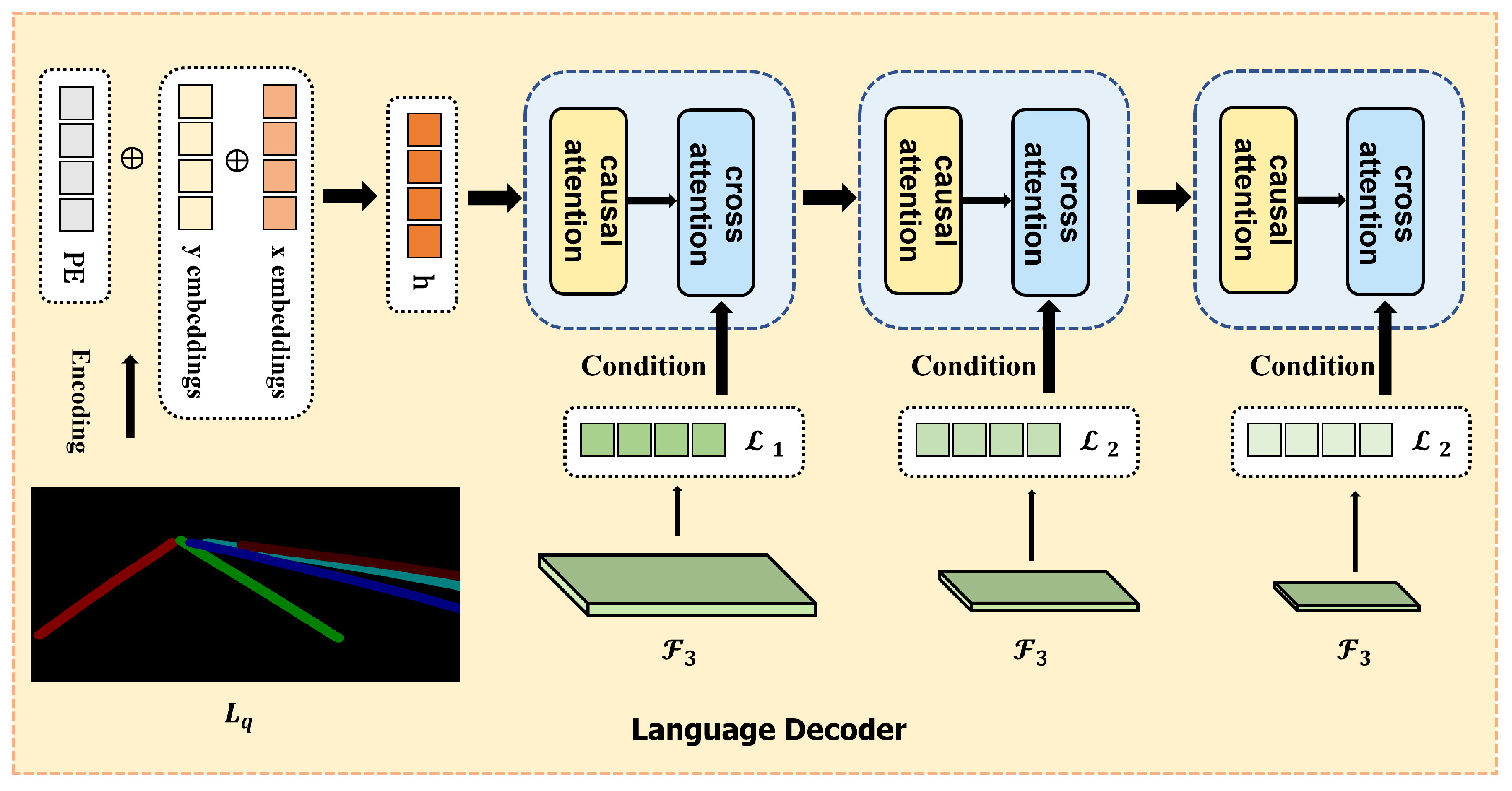

3. Proposed LaneLM

LaneLM has neither complex trick nor sophisticated structure. First, we tokenize the float keypoints and convert them into word embeddings. Then, we use a visual encoder to transform the visual information into visual embeddings. Next, a language decoder (shown in

Figure 4) is designed for prompting. We simply use cross-attention layers to condition the language model [

35] on visual inputs.

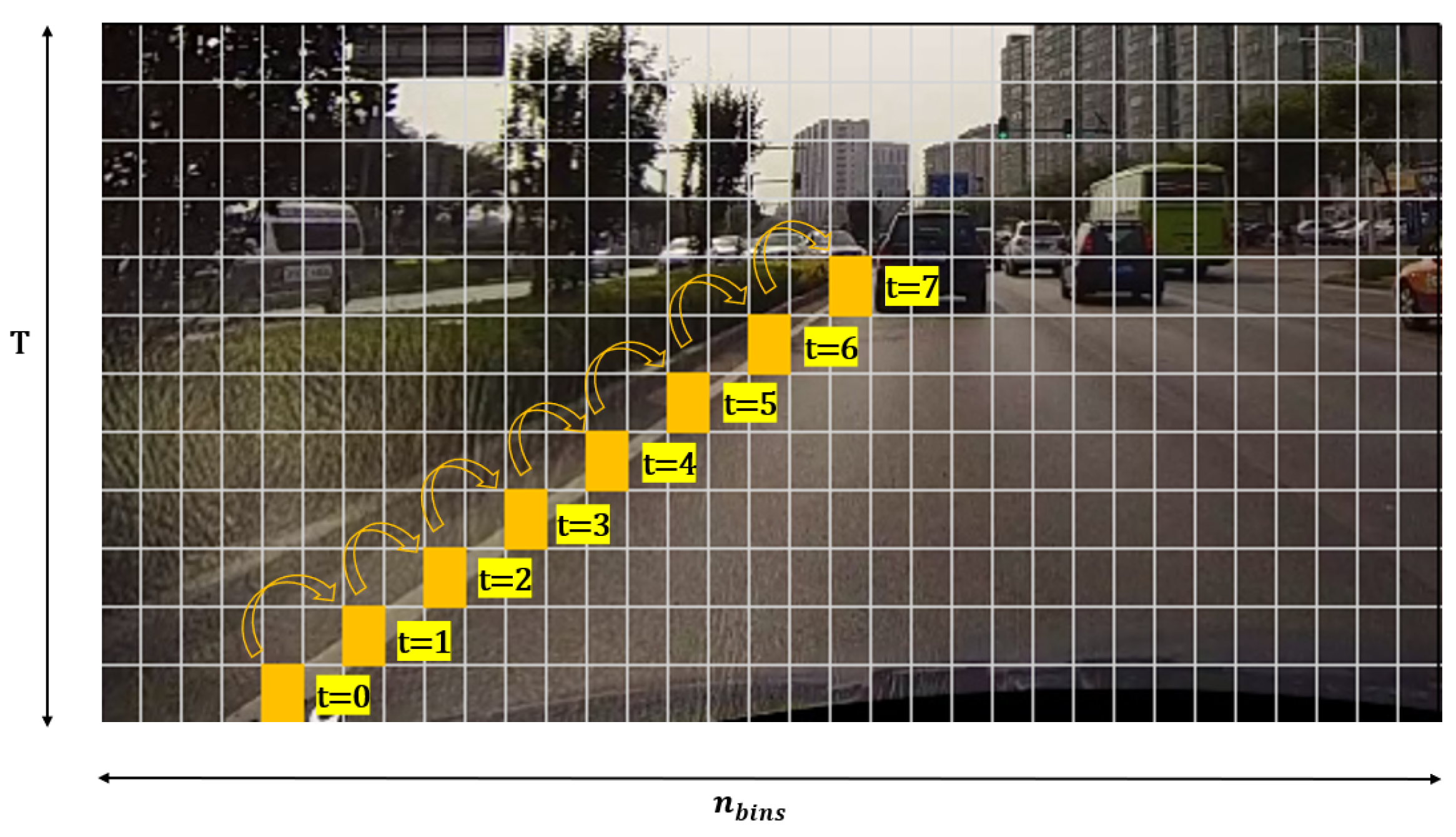

3.1. Lane Representation

A lane is a sequence of xy coordinates represented as tuples of float numbers. First, we quantize the float numbers in these tuples into integer tokens. Then, we integrate the x and y coordinates information into a single embedding, transforming it into a contextual representation that can be processed by a transformer decoder.

Lane tokenization. In order to represent lanes, following [

6,

8], we use equally-spaced 2D-points as lane representation. Each lane

L is expressed as a sequence of keypoints, i.e.

in which

y coordinate is equally and vertically sampled at regression time step

t, i.e.

, where

H is image height. Inspired by row-wise methods mentioned above, we transfer continuous keypoints of lane into discrete counterparts. Then we can rasterize H pixel rows into integer space

T, which is also the vocabulary size for

. Specifically, the keypoint at time step

t is composed of two tokens, i.e.

. For each column,

is quantized to

, in which

is the vocabulary size for

.

Figure 2 shows the row-wise location for a lane. We process the

-classes classification in each row and

T-classes classification at time step

t in each column.

It should be noted that 0 and T are padding tokens for coordinates respectively (i.e. if there is no lane at time step t, let and ). Here, T also refers to the number of rollouts.Then we use the quantized term to index a learnable vocabulary to get the token counterpart, which allows the model to depict the location of keypoints.

Keypoint token encoding. If

in the i-th lane at time step

t is given, we use two simple embedding layers

and

to get the token embeddings

, where

D is the size of each vector. Therefore, each integer tuple

is mapped to a high-dimensional vector.

where

is positional encoding in language modeling [

35] to provide transformer model with information about the position of each token in the sequence. Eq.

2 encodes the information of the x-coordinate and y-coordinate of tuple

into embeddings, which are then fused through addition, followed by the incorporation of positional information. The sequence composed of these embeddings conditioning on visual features is subsequently processed by a language decoder. In the output layer, each embedding will go through the linear head and predicts the next token by classification:

Therefore, we embed a integer tuple lane sequence

L (see Eq.

1) to its contextual representation

3.2. Probabilistic Rollouts

Probability factorization. Following [

25], let

represent the target keypoints for the

n-th lane at time

t. We cast LD as a next-token prediction task, formulated as a conditional probability

, where

represents the set of target keypoints for all lanes at time

t and

is the visual context, RGB image inputs from camera. Thus, we factorize the distribution over future sequences as a product of conditionals:

Similar to [

25], Eq.

6 represents the fact that we treat each lane as conditionally independent for its keypoint at time

t, given the previous keypoints and visual context.

n-lanes parallelism at time step t. In this formulation, we duplicate the visual context

n times for each lane in an image, where duplication is repeated in batch dimension in our implementation to calculate

in parallel because they are assumed to be conditionally independent as described in Eq.

6.

3.3. Network Architecture

In

Section 3.1, we obtained the embedding sequence for the keypoint modality. Similarly, we first encode the image into an embedding sequence using a visual encoder. Then, the information from both the visual modality and the keypoint modality is fused within the AR language decoder. Ultimately, each output embedding can be utilized by the classification head to predict the next token id. We use an encoder-decoder structure for learning and inference. Such a network architecture is widely used in vision-language model [

28,

29,

36] and language model [

37].

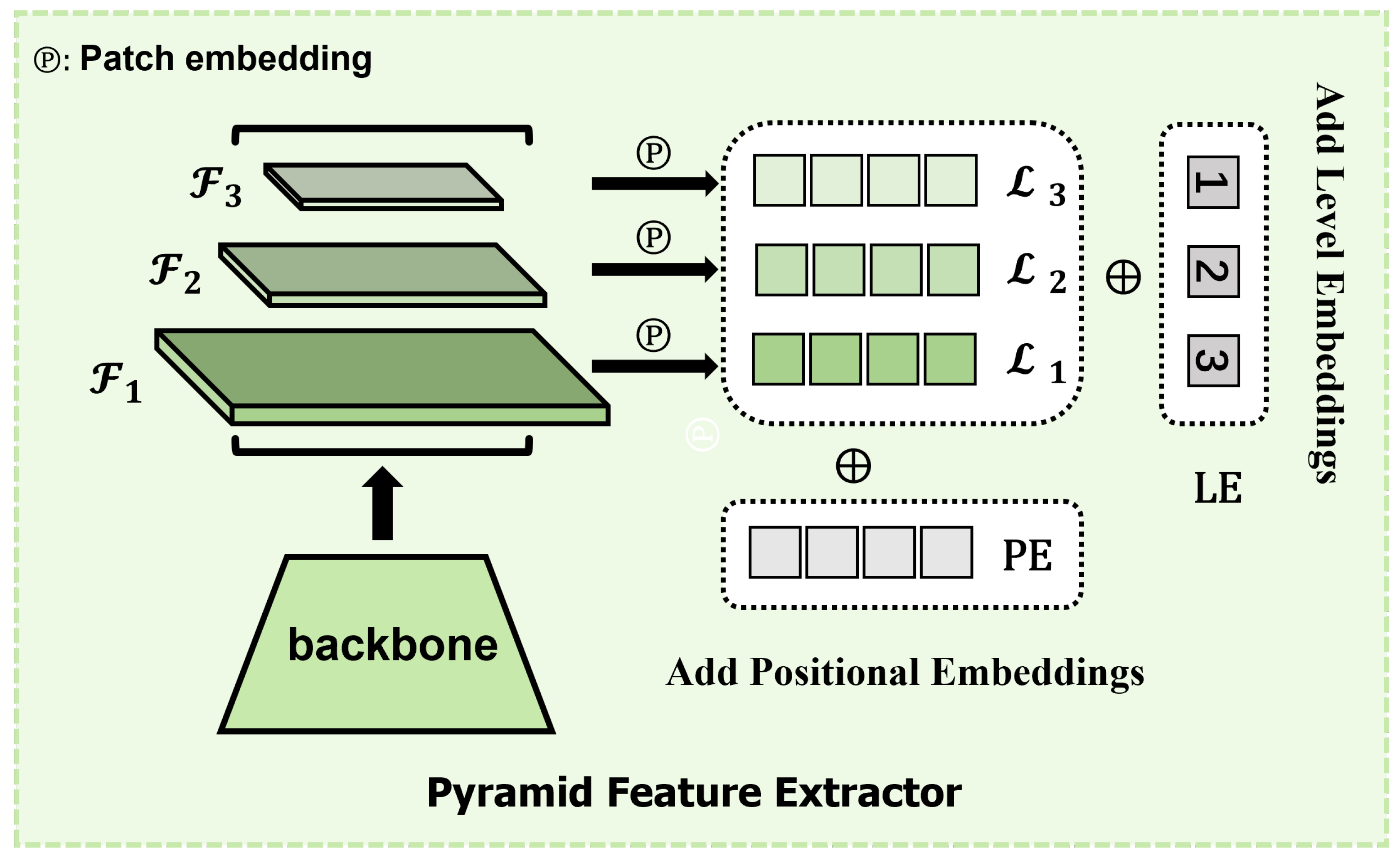

Visual encoder. Our visual encoder has to extract visual features from images and then transform them into embedding sequences. The pyramid feature extractor

f shown in

Figure 3 adopts the standard ResNet[

38] and DLA[

39] as visual feature extractor. And we add a FPN [

40] neck to provide integrated multi-scale features:

where

,

and

is the channel, the height and the width of the i-th level feature

extracted from CNN and FPN [

40].This structure leverages ConvNet’s pyramidal feature hierarchy and demonstrates its efficiency in [

6,

13,

16,

41]. Then we split

into fixed-size patches, linearly embed each of them, add position embeddings:

where

is level embedding that embeds level information into vectors,

is patch embedding in ViT[

42],

is its standard positional encoding layer that retains the positional information of each patches and the result value

represents the token sequence extracted from level feature

, in which

is the number of patches and we linearly embed them into

D-dimensional visual embeddings to aligned with keypoint embeddings

.

Since ViTAdapter [

43] proposes a pretraining-free adapter and achieves SOTA result in dense prediction and more and more visual-language model [

28,

29] use a frozen pretrained visual encoder and with how well the spatial feature in LD has been exploited, there is good reason to believe that we can directly adopt a frozen backbone from pretrained to reach comparable performance.

Language decoder. Our language decoder causally models keypoint sequence and conditions each embeddings

e on visual sequences

. As shown in

Figure 4, we use a transformer decoder for target sequence generation. This decoder consists of 3 layers of LaneLM blocks. For every LaneLM block, we insert new cross-attention layers between OPT[

35] causal attention blocks, trained from scratch. The visual feature sequence

, a sequence of flatten 2D-patch embeddings will serve as keys and values in cross-attention layer of block

i while queries are derived from keypoint prompts:

in which we denote

as hidden state output from block

i and specially,

is original keypoint embedding sequence input.

should go through word embedding layer and add position embedding as OPT[

35] does before feeding into block

i.

Our LaneLM layer can avoid information leak. cross-attention ensures that the outputs for a certain position in a sequence is based only on the known query tokens at previous positions and not on future positions. Besides, each query embedding is conditioned on the whole visual information. Theorem A1 demonstrates the feasibility of the network architecture.

Decoupled head. In training phase, every embedding (except for the last embedding of each sequence) output from language decoder will go through

x head and

y head to predict the next token id of x and y as illustrated in Eq.

3. Considering that predicting ordered

y sequence is a simple task, we use two decoupled classification heads,

x head,

y head, to predict the next token of

x and

y, respectively, instead of predicting

tokens like [

25]. Such decoupled prediction strategy greatly reduces complexity of classification from

to

. To further reduce computational overhead, these heads share the same hidden state input because the embedding

contains the information of both x-coordinate and y-coordinate (see Eq.

2).

Figure 4.

To condition the LM on visual inputs, we insert cross-attention layers between causal attention layers. The keys and values are obtained from the visual features while queries are derived from keypoint prompts

Figure 4.

To condition the LM on visual inputs, we insert cross-attention layers between causal attention layers. The keys and values are obtained from the visual features while queries are derived from keypoint prompts

3.4. Training and Inference

Visual question answering. If the detector knows where lanes are, we just need to teach it to read them out so that we can refine the location of keypoints in this context. For instance, during training, each image is pre-annotated by other lane detection models. The output labels are converted into pseudo labels using the method described in

Section 3.1. These pseudo labels are then used as lane priors and fed into the language decoder as queries to extract spatial information from the keys and values in its cross-attention modules. In this way, the model gains an approximate understanding of the lane locations. Our goal is to refine these locations or just read them out if pseudo labels are accurate enough. Moreover, These pseudo-labels can be regarded as questions in VQA, while their corresponding ground truth serves as the answers to these questions. In this way, the LD task is transformed into a VQA task.

Self-supervised labels. Following [

28,

29], we design a muti-turn conversation between LaneLM and a pretrained teacher. For an input image

, we consider the pretrained detecor [

6], which provides pseudo keypoint labels

as init queries for laneLM. Then we generate multi-turn conversation data

, where

N, the max number of turns is also the max number of lanes in each image and

is the first lane of ground truth in the image. We organize them as a sequence by treating ground truth as the answer of pseudo label. Therefore, the multi-modal self-supervised label

S for image

can be expressed as follows:

where ∘ means concatenating two sequences. We adopt the bipartite matching to find the matching that minimizes the distance of the start points between the query sequence

and the answer

, and then take the matched pair

as the self-supervised label for each lane.

Loss. We only adopt standard loss in the decoder-only language models. We train our model by minimizing negative log-likelihoods of keypoint tokens conditioned on the visual inputs

with cross entropy loss at each time stamp

t:

where

T is the length of the sequence.

Inference. We sample tokens from the model likelihood

and

using the argmax sampling as illustrated in Eq.

3.The same as language models, we apply the standard greedy search with fixed length and EOS (the End of Sequence token) stop criteria to generate

tokens at the same time (i.e. we stop prediction when EOS token is predicted or the current sequence reaches the max length). After obtaining the discrete tokens, we de-quantize them to get continuous coordinates.

To speed up the inference, in addition to adopting the parallel strategy outlined in

Section 3.2, each level of visual sequence

is cached into the decoder’s corresponding cross-attention layer. Further more, we adopt the KV-cache strategy in each causal self-attention layer only at inference time.

Prompting strategy. We have the following three prompting strategies. (1) A regression network is employed to provide the two initial keypoints, for each lane. LaneLM is responsible for completing the remaining keypoints. The regression network (we use CLRNet [

6]) only gives start points for each lane rather than the holistic lane, which is easier than the LD task. Keypoint-based methods [

13,

14,

15] use the similar start point regression. However, they are struggling to design keypoint decoding strategy while we leverage contextual representation of lane and just rollout the keypoints. (2) Pseudo labels in

Section 3.4 are given as questions, our language decoder leverage the few-shot capability to generate the answers and refine the read input or just read them out. (3) We simulate the annotation process performed by annotators by introducing a certain level of noise to the ground truth (randomly shifting the x-coordinates by -5 to 5 pixels) to demonstrate LaneLM’s capability of interaction. (4) We give some simple instruction tokens to LaneLM to accomplish some post-processing tasks.

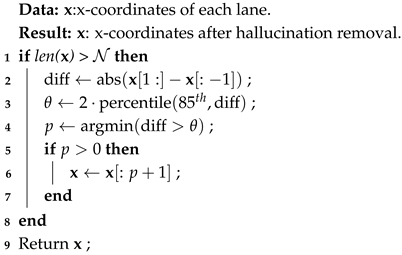

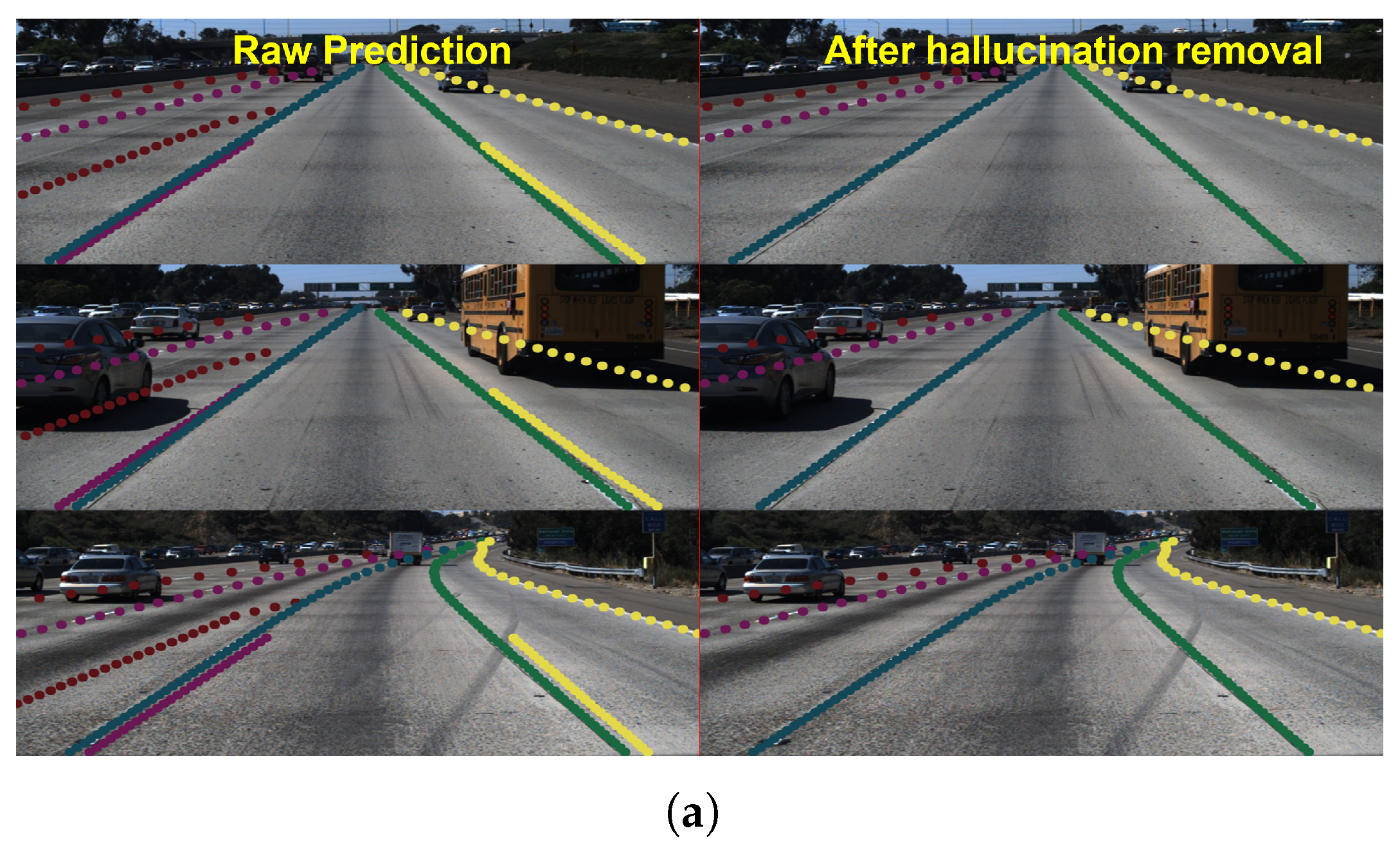

3.5. Hallucination Removal

Language models are prone to hallucination, generating plausible but non-factual content [

44]. As shown in Figure 6(a), like most language models, LaneLM may exhibit hallucination on side lanes. In order to mitigate such hallucination, we have developed a threshold filtering strategy

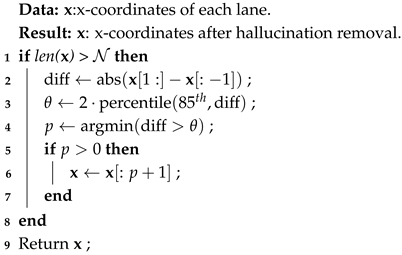

HR (Hallucination Removal) based on clustering at the 85th percentile, in which points with offsets of adjacent x-coordinates exceeding twice the 85th percentile, along with their subsequent points, will be filtered out. Figure 6(a) shows the mitigation of hallucination after filtering by HR.

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

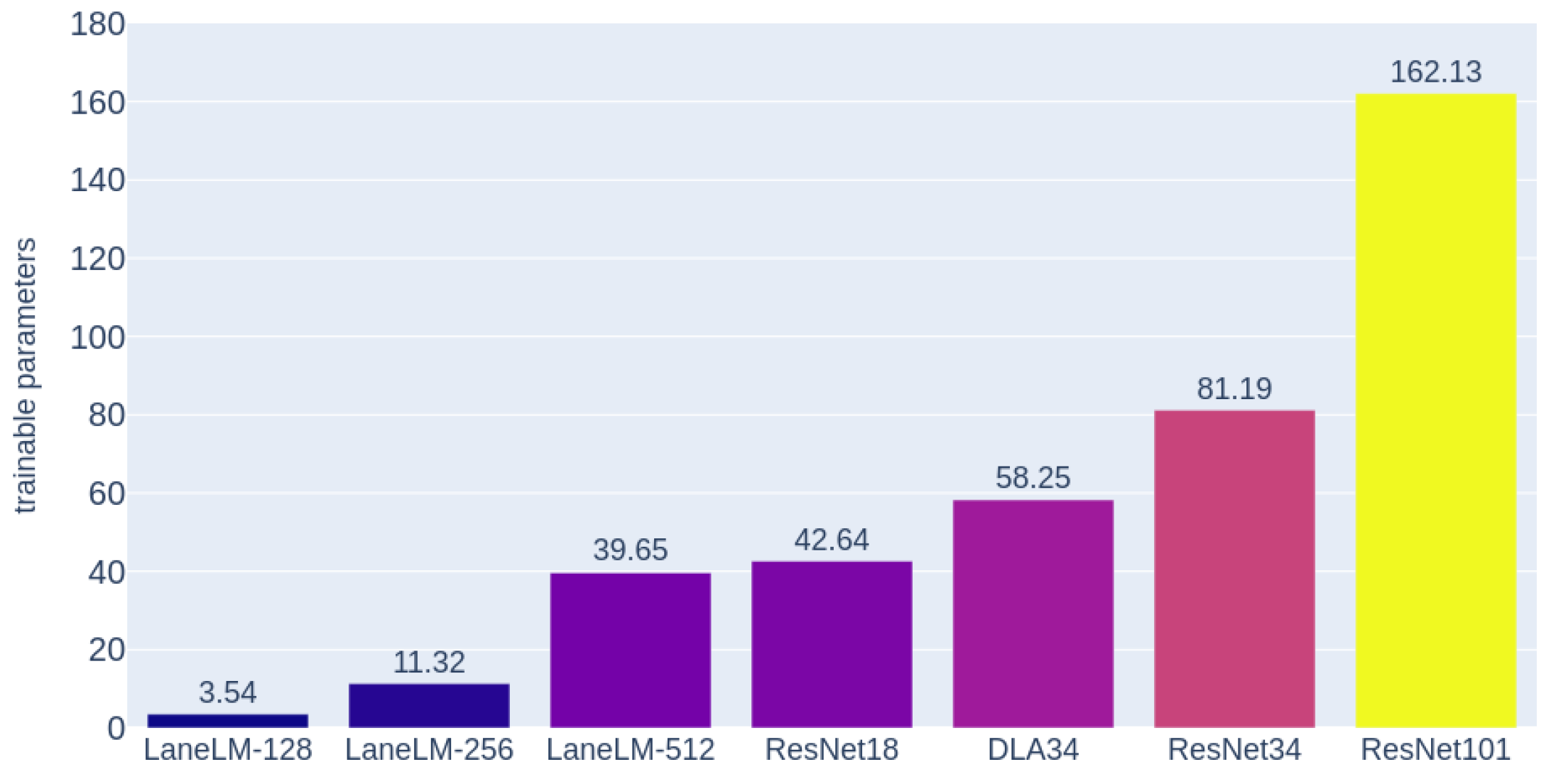

Model variants. We have three model variants and their trainable parameters are shown in

Figure 5. With the different hidden size of the decoder, the visual encoders of LaneLM-128, LaneLM-256, and LaneLM-512 are ResNet18, ResNet34 [

38] and DLA34 [

39].

Hyperparameters. We generate 40 points (

) for CULane [

45], 56 for TuSimple [

46] and LLAMAS [

47]. We only apply HR for lanes whose valid number of points is greater than

in Alg. 1. On CULane [

45] and LLAMAS [

47], the max number of lanes

, while on TuSimple [

46]

. The padding value for

x-offsets is 0, while

T for

y. EOS is a special token that represents the end of the sentence.

is an EOS token when

or

. In our additional study, we use EOS token as cmd to control the output and LaneLM stops its inference until the second EOS token is predicted.

|

Algorithm 1: HR(·) |

|

Training environment. All experiments are carried out with a single NVDIA GeForece RTX 4090, 128 batch size, 800

and 100 training epochs and we report the best results in Table 3, Table 2 and Table 4. All visual encoders are frozen in the training phase and pretrained from [

6].

4.2. Real-Time Performance and Computational Overhead

Figure 5 shows that the trainable parameter of LaneLM is extremely low. We aim to make LaneLM like an adapter, bridging the visual and language modalities. Similar to multimodal models, there is no need for pre-training the visual encoder. LaneLM is easy to plugin into any LD models.

Table 1 reports FPS (Frames Per Second) of LaneLM. We did not measure the inference time for the visual encoder

f in Eq.

7 because it is frozen and shared with the teacher model CLRNet [

6], which can also be replaced with other pretrained models. We set batch size to 1 and measure the max memory allocated during inference using the corresponding function in pytorch. T=80 indicates that we rollout 80 keypoints for each lane. The impact of sequence length on memory overhead is minimal when the batch size is relatively small.

The real-time performance of LaneLM can be attributed to our cache strategies. We cache the visual sequence of each level feature in each cross-attention layer in language decoder and adopt KV-cache at inference time. All lanes in the same image can be batch processed after padding. Lane2Seq [

3] is an AR LD model, which can not reach real-time performance.

Figure 5.

The comparison of trainable parameters in LaneLM with some backbones.

Figure 5.

The comparison of trainable parameters in LaneLM with some backbones.

4.3. Datasets

Our experiments are conducted on three lane detection benchmark datasets:

CULane [

45] and

TuSimple [

46] and

LLAMAS [

47].

CULane [

45] is a large-scale dataset that poses significant challenges for lane detection. It encompasses nine challenging categories, including crowded scenes, nighttime conditions, crossroads, etc. It has 100,000 images. Each image in CULane has a resolution of 1640 × 590 pixels.

Tusimple [

46] lane detection benchmark is among the most widely used datasets in lane detection. It consists solely of highway scenes and contains 3268 images for training, 358 for validation, and 2782 for testing. These images have a resolution of 1280 × 720 pixels.

LLAMAS [

47] is a large lane detection dataset that has more than 100,000 images. The annotations in LLAMAS are automatically generated using high-definition maps. The images in LLAMAS are all from highway scenarios. For evaluation purposes, the CULane’s F1 metric is utilized. The annotations of the testing set are not publicly available.

4.4. Evaluation Metric

For

CULane [

45] and

LLAMAS [

47], we use the F1@50 measure as the evaluation metric. We compute intersection-over-union (IoU) of two lanes, which is defined as the IoU of the two lane masks within 30 pixels and used to determine whether a sample is true positive (TP), false positive (FP), or false negative (FN), between prediction lane and ground truth. Predicted lanes with an IoU greater than a threshold (50%) are regarded as true positives (TP). Further, F1 score is calculated as follows:

In particular, since there are no lanes in the cross-road scenes, the false negative will be adopted as the evaluation metric.

For

Tusimple [

46], we report three official metrics: false positive rate, false negative rate and accuracy:

where

is the total number of ground truth lane points and

is the number of correct lane points in prediction of a clip. A predicted lane is considered correct if more than 85% of its predicted lane points are within 20 pixels of the ground truth. In addition, we also report the F1 score on TuSimple.

4.5. Benchmark Results

Performance on TuSimple. Table 2 presents the performance comparison with SOTA methods on TuSimple. * indicates that LaneLM only uses prompting strategy (1) from

Section 3.4. The performance difference on this dataset is very small because TuSimple is a dataset of small scale and it contains single scene only. Our prompting strategy has a limited effect on performance. The result in this dataset seems to be saturated. Therefore, The prediction can easily overlap with the ground truth. It is hard to get a significant improvement on TuSimple.

Performance on CULane.

Table 3 reports the main results on CULane. Our model receives two adjacent keypoints output from CLRNet [

6] as init prompts for each lane and rollouts the remaining keypoints in the * version. To explore the interactive capability of LaneLM, (2-kp) denotes that the holistic lane predicted from CLRNet is given and two adjacent ground truth keypoints with ramdom shift at the commencement of each lane are also supplied to enhance model performance.

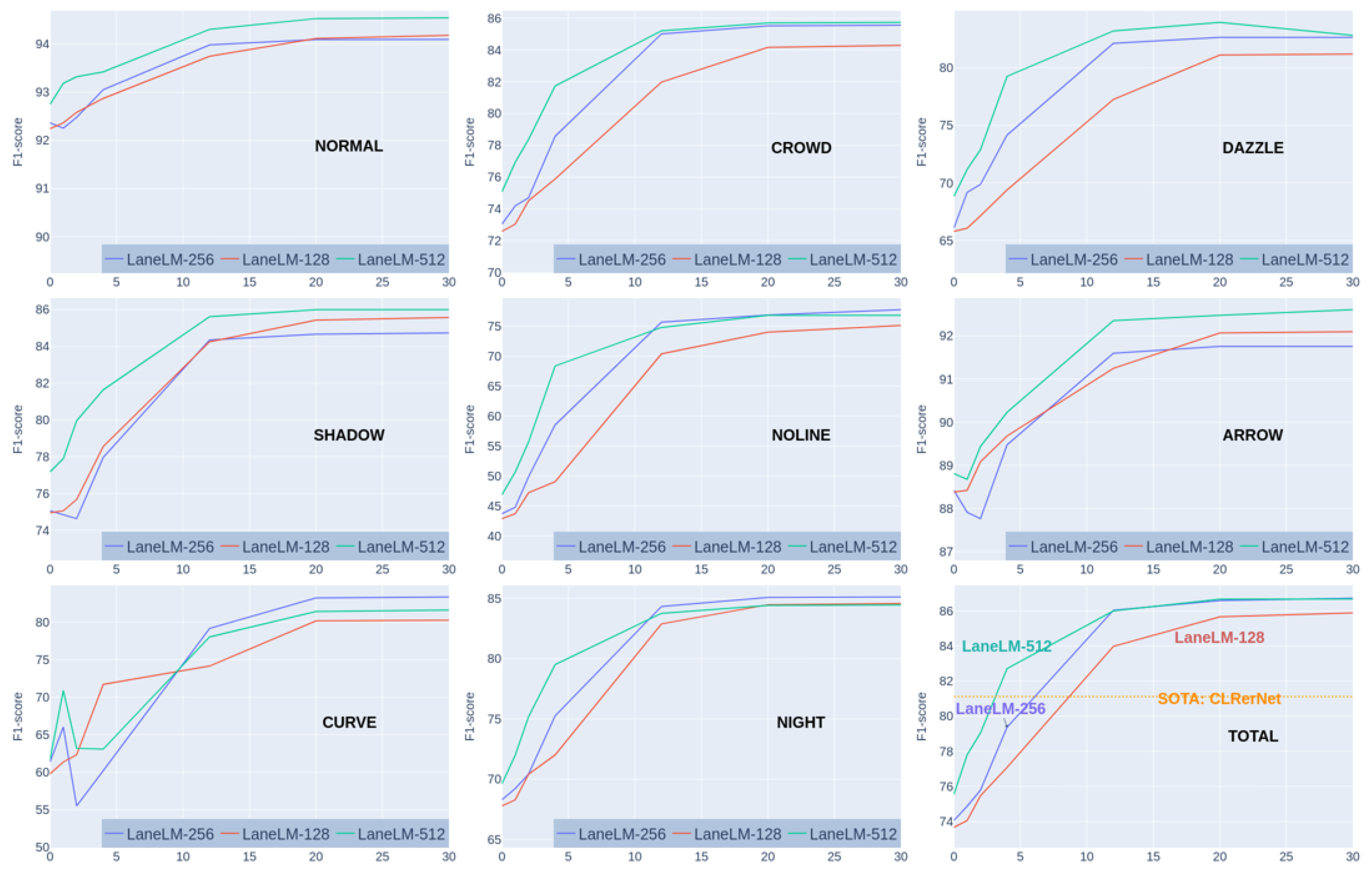

We observed that with the increase in the number of keypoint prompts, F1-score has significantly improved in most corner cases, which can be attributed to the powerful language modeling capability. The results on CULane demonstrate that our model has surpassed the SOTA [

9] after prompting and is particularly suitable for application in the annotation of corner cases. More results can be found in

Figure A1

Analysis on Limitations.

(1) In the * version, LaneLM underperforms CLRNet because, in Eq.

10, LaneLM actually predict pseudo-labels from CLRNet i.e. the knowledge of this part in LaneLM is distilled from the CLRNet.

(2) LaneLM with fewer keypoint prompts is worse than the * version because, in the training sequence, a sudden jump occurs at the junction between the pseudo-label and the ground truth (see Eq.

10), which disrupts the contextual semantic information and confuses the model. It has been observed that the model often hallucinates on the side lanes, indicating that the model struggles to cope with abrupt changes in semantic information.

Performance on LLAMAS. The result on the LLAMAS is shown in

Table 4. LaneLM-512 outperforms PolyLaneNet [

20] by 7.05 and LaneATT [

8] by 2.08. The training strategy is slightly different with CULane and TuSimple. We directly use

as self-supervised label

S and

is not used during training, which is different with Eq.

10. Thus, we can avoid knowledge distilling from the teacher model.

4.6. Ablation Study

We have maintained a minimalist design for the model. LaneLM has neither complex trick nor sophisticated structure. To investigate the impact of pure language modeling architectures on LD tasks, we did not design complex spatial attention mechanisms.

Table 5 illustrates ablation study on CULane and shows effects of each module and prompting strategy in our method, where cmd refers to the command token. We use LaneLM-512 (0-kp) with DLA34 encoder but without

HR (Hallucination Removal), as our baseline to conduct our experiments. Experiments have proven that, compared with other methods which add the attention module to LD model, following the prompting protocol for inference can improve the accuracy of the model by a large margin in complex scenarios, demonstrating LaneLM’s powerful interactive capability. Modules specifically designed to handle spatial information, such as FPN [

40], can also significantly enhance the model’s performance.

Additionally, to explore the instruction-following ability of LaneLM, we conduct extra ablation study on command token that sets the predictions to null, in which a cmd token is given at the beginning of the sequence when it comes to no lanes in the image. This instruction can reduce the post-processing of autonomous driving, enabling the visual model to receive semantic feedback from human being and other models (e.g. large language models).

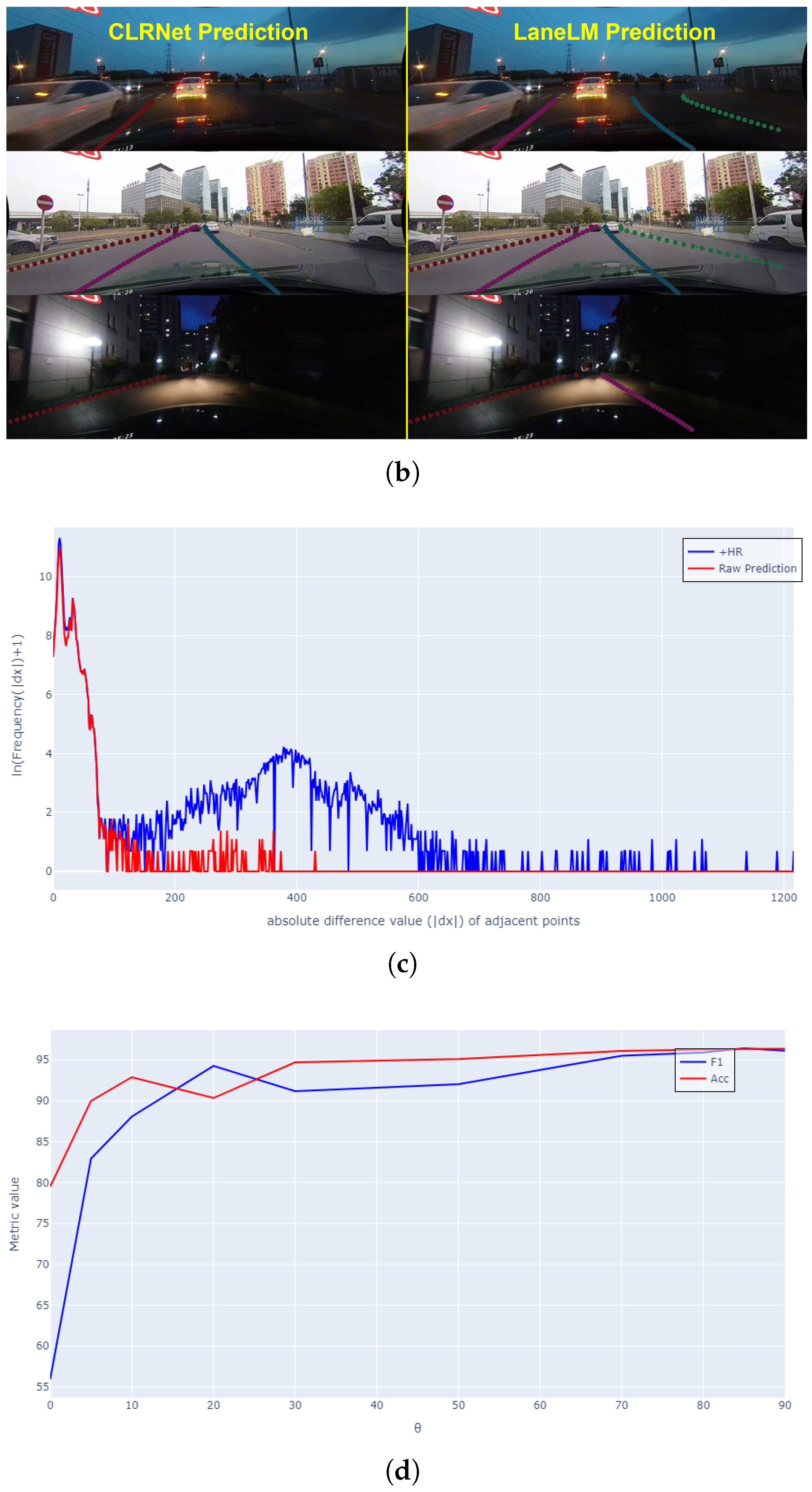

Analysis on hallucination. Current large language models are still struggling with hallucination. Figure 6(a) shows hallucination in LaneLM. Eq.

10 endows the model with the capability of VQA but it makes it easier for the model to predict cyclic sequences. Figure 6(a) illustrates that the model has learned the abrupt change points that connecting

and

on the side. LaneLM has learned the contextual representation of abrupt change points and consequently results in hallucination.

Study on hallucination removal. As shown in Figure 6(c), we collect the statistic results of lanes with hallucination from TuSimple, in which the red line demonstrates that a significant number of x-offsets with abnormal values have been filtered out by HR. As shown in Figure 6(d), to find the best percentile, we conducted a search for the performance of

on the F1 and Acc metrics on TuSimple using LaneLM-128 (0-kp). We report the detailed metric values in

Table 6.

Study on per pixel. To investigate the impact of the resolution of bins (i.e.,

per pixel) on performance, we vary the

and conduct our training on TuSimple using LaneLM-512 (0-kp). We report our result in

Table 7. Most LD methods resize images into 800 pixel width in training and inference.

=800 aligns with our intuition. Using large

, which increases the vocabulary size, has no significant improvement and it will slow down training. Choosing a larger

does not yield benefits because the model’s hidden size is too small relative to

, making classification difficult.

Qualitative results. We display the qualitative results in Figure 6(a-b). After keypoint prompting (2-kp), LaneLM can recall more lanes at night. The results show that LaneLM can effectively detect lanes in the multi-lane scenario (see Figure 6(a) right). The results demonstrate that LaneLM can be prompted from the semantic feedback. Semantic information directly determines the spatial attention of the model.

Figure 6.

(a) The left image shows the hallucination on the side lane, while the right image is post-processed with the HR algorithm. (b) The left image shows the CLRNet prediction and the right is LaneLM prediction. (c) shows the frequency distribution of horizontal distances between adjacent keypoints, with the x-axis as the ln(frequency) and the horizontal axis as the distance values. (d) shows the impact of different -percentile thresholds on F1-score and accuracy.

Figure 6.

(a) The left image shows the hallucination on the side lane, while the right image is post-processed with the HR algorithm. (b) The left image shows the CLRNet prediction and the right is LaneLM prediction. (c) shows the frequency distribution of horizontal distances between adjacent keypoints, with the x-axis as the ln(frequency) and the horizontal axis as the distance values. (d) shows the impact of different -percentile thresholds on F1-score and accuracy.

5. Discussion

Current autonomous driving technologies mainly focus on the fusion of visual sensors like LiDAR [

52,

53,

54], radar, and cameras. Visual modality often fail in corner cases. Many recent works [

55,

56,

57] has concentrated on Large Language Models (LLMs) to address the long-tail distribution in corner cases. However, they cannot interact with the visual models. Future autonomous vehicles will incorporate multiple redundant sensors for visual perception. In harsh conditions where sensors fail, a parallel LLM will leverage semantic information to prompt and enhance visual tasks, making the system more robust.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we present autoregressive LaneLM and treat the LD task as visual question answering. We use the language model to make LD task promptable and interactive. The lanes and images are transformed into multi-modal embedding sequences and interact with each other in LaneLM. Then we alleviate the hallucination by HR. Experiments show our proposed method outperforms previous unpromptable SOTA methods. The design of LaneLM is quite simple and doesn’t have overly complicated structures. We hope that LaneLM can serve as a baseline for language-modeling-based approaches. We believe that our work will pave the way towards unification for LLM and visual models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization Y.Z.; methodology Y.Z.; software, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; writing—original draft, Y.Z.; writing—review & editing, X.B. and Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62472349).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LD |

Lane Detection |

| VQA |

Visual Question Answering |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| HR |

Hallucination Removal |

| SAM |

Segment Anything Model |

| ADAS |

Advanced Driver Assistance Systems |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| NMS |

Non-Maximum Suppression |

| AR |

Autoregressive |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| SOTA |

State-Of-The-Art |

| FPN |

Feature Pyramid Networks |

| DCN |

Deformable Convolutional Network |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Theorem A1. cross-attention mechanism does not leak the information of the future query tokens.

Proof (Proof). Let’s revisit the cross-attention function:

Obviously, the softmax function preserves the order information of the query embeddings and does not leak information about future embeddings. Let

n,

m,

D and

be the sequence length of the query tokens, the value tokens, the hidden size and the embedding of the query token, respectively. According to the principle of matrix block calculation, the information interaction in cross-attention is equivalent to:

Therefore, cross-attention preserves the order information of the query tokens, preventing any information leakage and every query embedding is conditioned on the whole visual information

. □

Figure A1.

F1@50 in 9 categories on CULane for keypoint prompting. LaneLM reaches the state of the art on CULane [

45] with keypoint prompting, significantly outperforming unpromptable SOTA method [

9] with as few as 4 keypoint prompts at the beginning of each lane. We found that in corner cases, the marginal benefit of prompting is quiet large.

Figure A1.

F1@50 in 9 categories on CULane for keypoint prompting. LaneLM reaches the state of the art on CULane [

45] with keypoint prompting, significantly outperforming unpromptable SOTA method [

9] with as few as 4 keypoint prompts at the beginning of each lane. We found that in corner cases, the marginal benefit of prompting is quiet large.

References

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 4015–4026.

- Xu, N.; Price, B.; Cohen, S.; Yang, J.; Huang, T.S. Deep interactive object selection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 373–381.

- Zhou, K. Lane2Seq: Towards Unified Lane Detection via Sequence Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 16944–16953.

- Chen, T.; Saxena, S.; Li, L.; Fleet, D.J.; Hinton, G. Pix2seq: A language modeling framework for object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.10852 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, T.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, W.; Yang, Z.; Cai, D.; He, X. Clrnet: Cross layer refinement network for lane detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 898–907.

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Yang, J. Line-cnn: End-to-end traffic line detection with line proposal unit. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2019, 21, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabelini, L.; Berriel, R.; Paixao, T.M.; Badue, C.; De Souza, A.F.; Oliveira-Santos, T. Keep your eyes on the lane: Real-time attention-guided lane detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021; pp. 294–302.

- Honda, H.; Uchida, Y. CLRerNet: Improving Confidence of Lane Detection with LaneIoU. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2024; pp. 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Shin Yoon, J.; Shin, S.; Bailo, O.; Kim, N.; Lee, T.H.; Seok Hong, H.; Han, S.H.; So Kweon, I. Vpgnet: Vanishing point guided network for lane and road marking detection and recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017; pp. 1947–1955.

- Abualsaud, H.; Liu, S.; Lu, D.; Situ, K.; Rangesh, A.; Trivedi, M.M. LaneAF: Robust Multi-Lane Detection With Affinity Fields. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2021, 6, 7477–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Gao, X.; Jin, D.; Li, J. Channel Attention in LiDAR-camera Fusion for Lane Line Segmentation. Pattern Recognition 2021, 118, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Huang, S.; Hui, T.; Wang, F.; Qian, C.; Zhang, T. A keypoint-based global association network for lane detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022; pp. 1392–1401.

- Qu, Z.; Jin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, W. Focus on local: Detecting lane marker from bottom up via key point. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021; pp. 14122–14130.

- Xu, S.; Cai, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Fu, Y.; Xue, X. Rclane: Relay chain prediction for lane detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer, 2022; pp. 461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Zhu, S.; Tan, P. Condlanenet: a top-to-down lane detection framework based on conditional convolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 3773–3782.

- Qin, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Ultra fast structure-aware deep lane detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XXIV 16; Springer, 2020; pp. 276–291. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, X. Ultra fast deep lane detection with hybrid anchor driven ordinal classification. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2022, 46, 2555–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gong, M.; Du, B.; Qian, G.; Smith-Miles, K. Generating dynamic kernels via transformers for lane detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 6835–6844.

- Tabelini, L.; Berriel, R.; Paixao, T.M.; Badue, C.; De Souza, A.F.; Oliveira-Santos, T. Polylanenet: Lane estimation via deep polynomial regression. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR). IEEE; 2021; pp. 6150–6156. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Guo, S.; Tan, X.; Xu, K.; Wang, M.; Ma, L. Rethinking efficient lane detection via curve modeling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022; pp. 17062–17070.

- Liu, R.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, T.; Xiong, Z. End-to-end lane shape prediction with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 2021; pp. 3694–3702.

- Niu, J.; Lu, J.; Xu, M.; Lv, P.; Zhao, X. Robust Lane Detection using Two-stage Feature Extraction with Curve Fitting. Pattern Recognition 2016, 59, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017; pp. 764–773.

- Seff, A.; Cera, B.; Chen, D.; Ng, M.; Zhou, A.; Nayakanti, N.; Refaat, K.S.; Al-Rfou, R.; Sapp, B. Motionlm: Multi-agent motion forecasting as language modeling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 8579–8590.

- Jia, X.; Shi, S.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, L.; Liao, W.; He, T.; Yan, J. AMP: Autoregressive Motion Prediction Revisited with Next Token Prediction for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.13331 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, B.; Gao, H.; Liao, B.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vadv2: End-to-end vectorized autonomous driving via probabilistic planning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13243 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; et al. Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 23716–23736. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Bai, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, D.; Gong, Y. Autoregressive visual tracking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; pp. 9697–9706.

- Bai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Gong, Y.; Wei, X. Artrackv2: Prompting autoregressive tracker where to look and how to describe. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 19048–19057.

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning; Krause, A.; Brunskill, E.; Cho, K.; Engelhardt, B.; Sabato, S.; Scarlett, J., Eds. PMLR, 23–29 Jul 2023, Vol. 202, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 19730–19742.

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. BLIP: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training for Unified Vision-Language Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning; Chaudhuri, K.; Jegelka, S.; Song, L.; Szepesvari, C.; Niu, G.; Sabato, S., Eds. PMLR, 17–23 Jul 2022, Vol. 162, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 12888–12900.

- Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, X. CooKie: commonsense knowledge-guided mixture-of-experts framework for fine-grained visual question answering. Information Sciences 2025, 695, 121742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Roller, S.; Goyal, N.; Artetxe, M.; Chen, M.; Chen, S.; Dewan, C.; Diab, M.; Li, X.; Lin, X.V.; et al. Opt: Open pre-trained transformer language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.01068 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Boukhers, Z.; Hartmann, T.; Jürjens, J. COIN: Counterfactual Image Generation for Visual Question Answering Interpretation. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 770–778.

- Yu, F.; Wang, D.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Deep layer aggregation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 2403–2412.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 2117–2125.

- Xiao, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Kong, Y. Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Enhancement for Underwater Object Detection. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; He, J.; Lu, T.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y. Vision transformer adapter for dense predictions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.08534 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions. ArXiv abs/2311.05232. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Shi, J.; Luo, P.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. Spatial As Deep: Spatial CNN for Traffic Scene Understanding. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- TuSimple: TuSimple benchmark, 2019. https://github.com/TuSimple/tusimple-benchmark.

- Behrendt, K.; Soussan, R. Unsupervised labeled lane markers using maps. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision workshops, 2019; pp. 0–0.

- Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, H. Lane Detection with Versatile AtrousFormer and Local Semantic Guidance. Pattern Recognition 2023, 133, 109053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Deng, X.; Cai, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, H.; Xu, C.; Liang, X. Laneformer: Object-aware row-column transformers for lane detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 799–807.

- Xiao, L.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Yang, W. ADNet: Lane Shape Prediction via Anchor Decomposition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2023; pp. 6404–6413.

- Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y. Bsnet: Lane detection via draw b-spline curves nearby. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.06910 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Park, G.; Koh, J.; Kim, J.; Moon, J.; Choi, J.W. LiDAR-Based 3D Temporal Object Detection via Motion-Aware LiDAR Feature Fusion. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, G.; Hao, B.; Xiang, Y.; Yuan, K. DeployFusion: A Deployable Monocular 3D Object Detection with Multi-Sensor Information Fusion in BEV for Edge Devices. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfeqy, L.; Abdelmunim, H.E.H.; Maged, S.A.; Emad, D. Kalman Filter-Based Fusion of LiDAR and Camera Data in Bird’s Eye View for Multi-Object Tracking in Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, E.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wong, K.Y.K.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H. Drivegpt4: Interpretable end-to-end autonomous driving via large language model. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, A.M.; Chen, L.; Hünermann, J.; Karnsund, A.; Hanotte, B.; Chidananda, P.; Nair, S.; Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Shotton, J.; et al. LingoQA: Visual question answering for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2024; pp. 252–269. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.; Ma, Y.; Cao, X.; Ye, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, K.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.; Yang, Z.; Liao, K.D.; et al. A survey on multimodal large language models for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024; pp. 958–979.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).