Introduction

Computing hardware has seen significant advancements through the integration of three-dimensional architectures, photonic components and neuromorphic principles (Huang et al., 2024; Abderazek, and Dang, 2025). Nevertheless, these approaches face ongoing challenges related to spatial efficiency, thermal regulation, signal latency and manufacturing complexity. Wave-based systems, including optical and acoustic computing platforms, have emerged as promising alternatives due to their inherent parallelism and energy efficiency (Zuo et al., 2018; McMahon 2023). Despite this, the lack of geometrically optimized frameworks to guide, route and manipulate these waveforms limits their practical implementation. Traditional planar geometries fail to exploit the full potential of wave interactions in three-dimensional space, resulting in suboptimal use of physical resources and energy pathways. Recent efforts in bio-inspired design and topological materials suggest that certain mathematical forms—particularly those with periodic and ruled structures—may offer a path toward more efficient physical computing (Velivela et al., 2023). Within this context, we propose the use of Plücker conoid-inspired geometries as a spatial framework for wave manipulation and signal routing (Peternell et al., 2013). The Plücker conoid, a ruled surface defined by sinusoidal modulation around a central axis, provides an analytically tractable and structurally efficient manifold naturally aligning with the behavior of sinusoidal waves (Radzevich 2020). The Plücker’s conoid could be utilized for the mathematical modeling of surface contacts in mechanical engineering applications and for the assessment of geometrical problems in Computer-Aided Design, Computer-Aided Geometric Design and Computer-Aided Manufacturing (Radzevich 2005). This suggests that the Plücker conoid’s combination of geometric simplicity and modulation complexity makes it a promising candidate for supporting the functional requirements of emerging spatial computing systems.

We investigate how the geometric properties of the Plücker conoid influence wave dynamics and spatial organization in a controlled computational environment. Using a combination of parametric modeling and numerical simulation, we evaluate the conoid’s potential to structure electromagnetic and acoustic signals through phase modulation and interference control. By embedding wave behavior into a geometrically defined surface, we aim to demonstrate how the Plücker conoid’s sinusoidal and ruled features contribute to effective signal management within three-dimensional computational topologies. Our experimental approach evaluates both localized wave dynamics and large-scale routing performance, with a specific focus on maintaining signal coherence and analysing the directional characteristics of wave propagation. The periodic modulation along the axis provides opportunities for fine-tuned control over wave behavior, potentially enabling mechanisms such as spatial multiplexing, resonance filtering and interference pattern stabilization. This approach is reinforced by the surface’s inherent capacity to guide directional wave propagation while maintaining physical manufacturability and spatial coherence across multiple domains.

We will proceed as follows: the next section details the parametric modeling framework, simulation and implementation methodology. This is followed by an analysis of the surface’s impact on wave propagation and signal coherence. Subsequent sections present quantitative evaluations, compare results with conventional geometries and conclude with a discussion of the implications and constraints of Plücker conoid-inspired design.

Materials and Methods

Simulation Framework and Computational Environment. The following paragraphs present a simulated comparative analysis evaluated across multiple quantitative metrics between unmodulated (plain) and Plücker-modulated symmetries. All simulations of both the geometries were implemented in Python 3.11 using NumPy for numerical computation, Matplotlib for visualization and SciPy for statistical analysis. The simulation grid was defined using numpy.meshgrid over a two-dimensional spatial domain spanning from −4 to 4 in both the x and y directions, discretized into 400×400 points for sufficient resolution of high-frequency wave behaviors. This resolution ensures a spatial sampling interval , which satisfies the Nyquist criterion for wave

numbers up to approximately .

The waveforms were generated based on time-independent solutions to the scalar wave equation, with time snapshots taken at t=0. The base form of the traveling wave in a homogeneous medium was expressed as:

for a plain wave propagating in the x-direction, where

is the wave number and ϕ is a

randomized initial phase sampled uniformly from [0,2π] for

each independent run. The Plücker conoid modulation was introduced by embedding

a phase offset into the wave function via a spatially dependent term derived

from the conoid geometry. Each simulation was performed 40 times independently

for both the plain and modulated geometries.

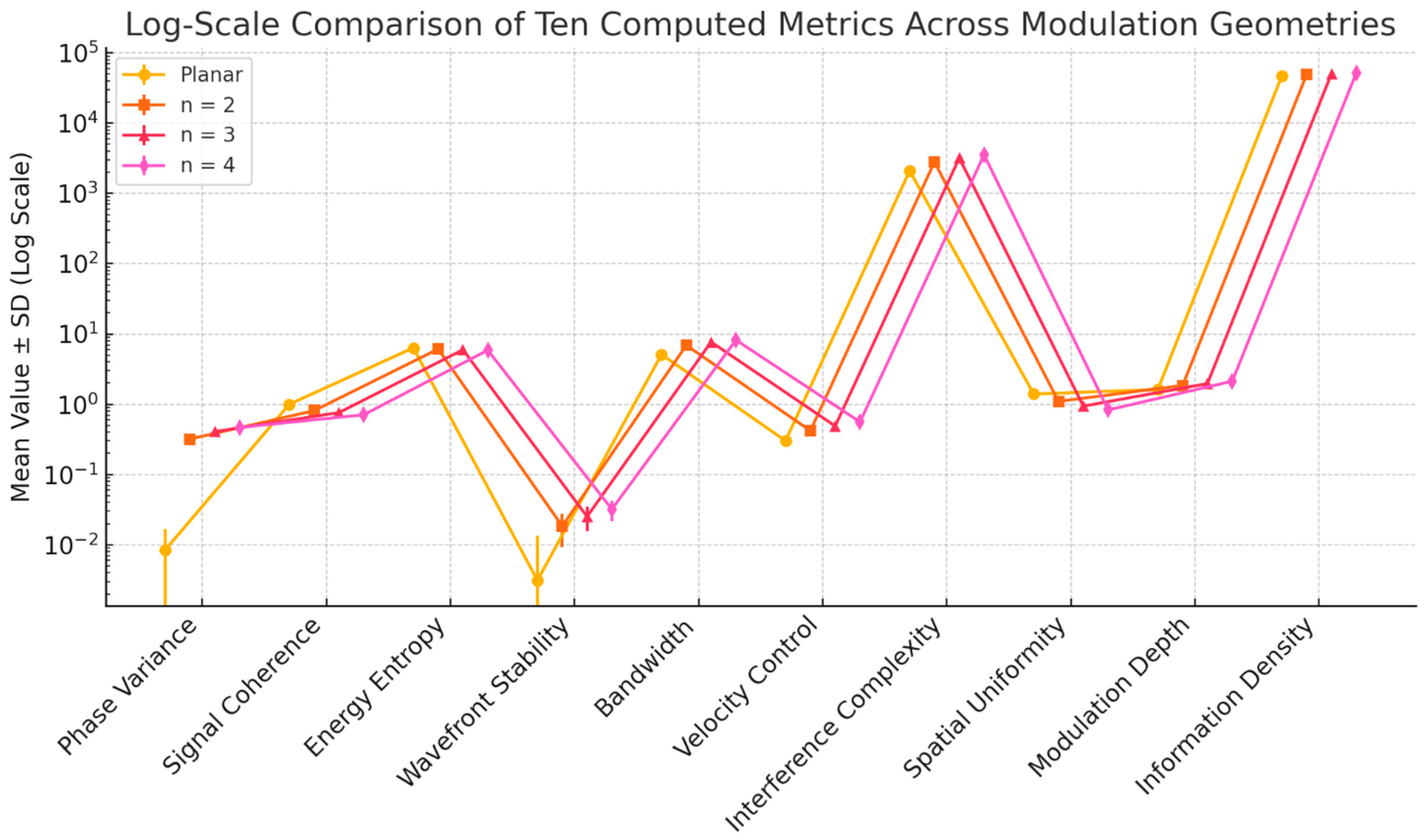

Mathematical Formulation of the Plücker Conoid Modulation. To simulate the effect of a Plücker conoid on wave propagation, we incorporated a phase-modulating function that mimics the geometry of a sinusoidally modulated ruled surface (Radzevich 2020). The Plücker conoid can be parametrized as:

where

a is the amplitude of modulation and

n is the number of sinusoidal lobes around the central axis. In our simulations, we reformulated the modulation into a Cartesian domain by transforming the angular parameter

, yielding a phase offset term:

This modulation was then injected into the phase term of the wave equation, yielding the modulated wave:

This procedure ensured that the modulation was spatially coherent and rotationally symmetric.

Figure 1 illustrates the variation among Plücker conoid geometries with modulation numbers

n=2,

n=3, and

n=4. As

n increases, the number of sinusoidal lobes per full rotation grows, resulting in finer spatial modulation and greater complexity in wave-shaping behaviour. The inclusion of

affected the local phase velocity and interference

characteristics of the wave, which could then be analyzed via metrics such as

coherence, phase control and wavefront complexity. This formulation established

the mathematical basis for evaluating the effect of Plücker-type geometries on

wave propagation dynamics.

Assessed metrics. We analysed a set of factors selected to collectively offer a comprehensive evaluation of how Plücker conoid-inspired modulation may affect wave behaviour across spatial, spectral and structural dimensions. Phase control quantifies the ability to reshape wavefronts, essential for directing or encoding signals (Bowman et al., 2017). Signal coherence assesses structural integrity, ensuring that modulation preserves usable signal correlation (Ramírez et al., 2023). Energy localization, measured via entropy, reflects how efficiently energy concentrates, beneficial for spatial focus. Wavefront stability gauges robustness under perturbations, indicating reliability. Bandwidth reveals frequency richness, supporting signal complexity (Afzal et al., 2023). Velocity control, derived from phase gradients, suggests tunability of wave delay. Interference complexity measures structural richness in the spectral domain, crucial for multi-channel encoding (Praveena et al., 2022). Spatial uniformity indicates pattern regularity, while modulation depth captures dynamic range (Malik et al., 2014). Finally, information density quantifies the number of meaningful transitions, a proxy for spatial resolution (Crocker et al., 2016). Together, these metrics provide insight into amplitude, phase, frequency and spatial structure, offering a multidimensional profile of wave modulation effects that are interpretable, quantifiable and relevant to both physical and computational analysis.

Phase Control and Signal Coherence Evaluation. Phase control was evaluated by computing the variance of the phase difference between the modulated and plain wave fields. The instantaneous phase was approximated by applying the inverse sine function, constrained within [−1,1], as:

Given the limited range and nonlinearity of

arcsin, this method was applied under the assumption of small angular deviation and was consistent across both geometries to ensure comparative validity. The variance of the differential phase field:

Signal coherence was evaluated via normalized cross-correlation between the modulated and plain wave fields. The coherence

C was computed as:

To ensure normalization, both wavefields were z-scored before correlation. These two metrics jointly quantified how well the modulated surface could introduce meaningful phase transformations while maintaining overall structural fidelity of the waveform. Together, they established a robust foundation for analyzing modulation quality in geometrically engineered media.

Energy Localization and Wavefront Stability. To quantify spatial energy concentration, we used the entropy of the normalized energy field:

The entropy

H was then given by:

This formulation captures how evenly wave energy is distributed across the domain. Lower entropy indicates higher localization, suggesting that energy concentrates in specific zones—a desirable trait for wave-based logic or detection systems.

Wavefront stability was assessed by applying a small Gaussian noise perturbation to the phase of each wave:

where

with σ=0.1. The mean squared deviation between the perturbed and unperturbed wave fields was then computed:

This quantity served as a stability index, with lower values reflecting higher robustness. These two measurements jointly elucidate the behavior of the system under energetic and structural perturbations, providing insight into reliability and fault tolerance.

Bandwidth, Velocity Control and Interference Complexity. Modulation bandwidth was quantified by computing the spectral spread in the spatial frequency domain. Each wave field was Fourier transformed using:

The magnitude of the spectrum was then analyzed and its standard deviation calculated to determine spectral width:

This measurement reflects how diverse the wave frequencies are due to modulation. Broader bandwidth suggests higher capacity for encoding variation.

To approximate group velocity control, we examined the gradient of the spatial phase in the x-direction:

The phase ϕ was estimated as:

and unwrapped to avoid discontinuities. The average magnitude of the spatial gradient served as a proxy for controllable signal timing.

Interference complexity was measured as the number of spatial frequency components exceeding a normalized threshold in the Fourier domain:

with

. This count quantifies the structural richness of interference and node formation within the wave pattern. These metrics collectively highlight the spectral and temporal behavior induced by geometrical phase modulation.

Spatial Uniformity, Modulation Depth and Information Density. Spatial uniformity was assessed by computing the inverse of the standard deviation of the wave field:

This metric reflects how homogenous the wave amplitude is across space. Lower standard deviation (i.e., higher

U) implies greater uniformity, often indicative of regular propagation.

Modulation depth was defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum wave amplitude:

This simple measure captures the amplitude swing, important for encoding and wave discrimination tasks.

Information density was quantified by counting the number of zero crossings in both spatial directions. Let and similarly for . The density was:

This represents the frequency of state changes, analogous to high spatial-frequency content. Taken together, these three metrics describe amplitude variability and spatial resolution potential.

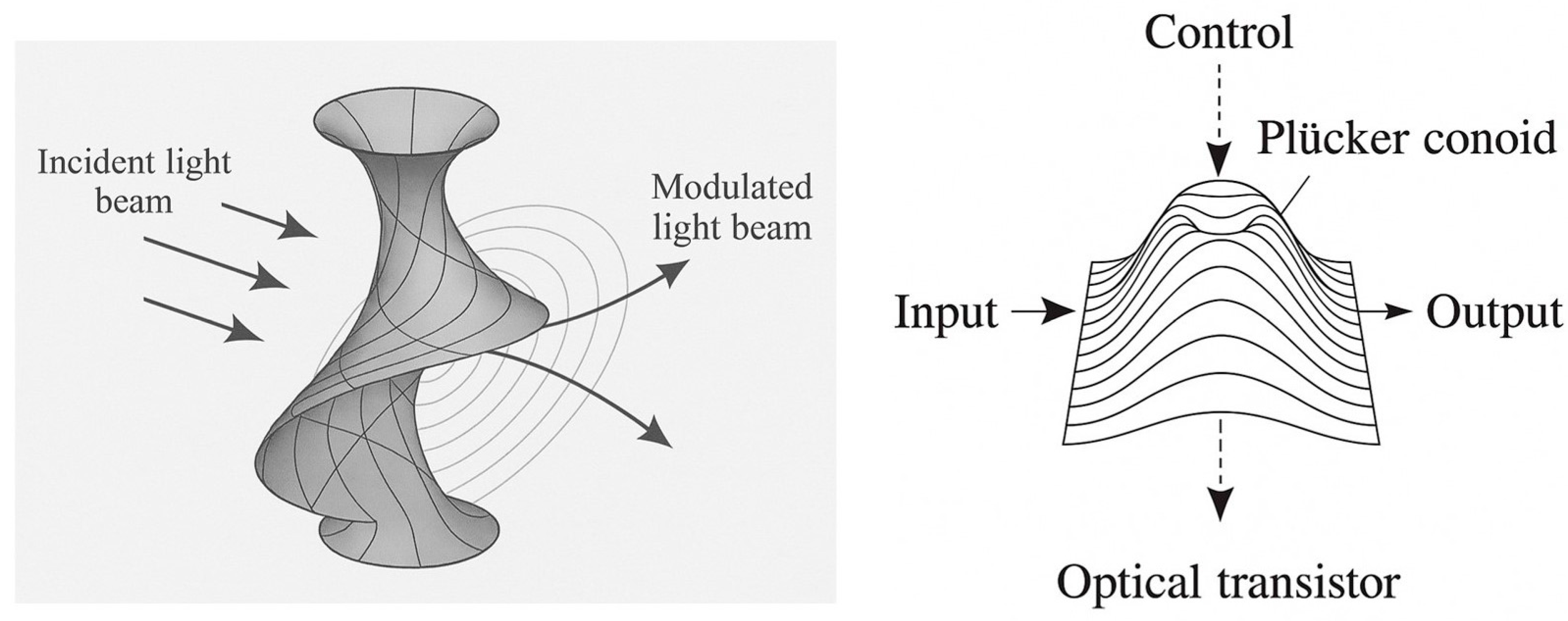

Implementation. The model can be implemented in a wave modulation system characterized by a surface geometry based on a Plücker conoid. This surface geometry may be implemented as a three-dimensional topography or encoded into a two-dimensional metasurface.

Figure 2 illustrates an optical transistor in which a guided input beam interacts with a surface modulated according to a Plücker conoid profile. A wave is directed over the surface, inducing passive spatially varying phase shifts. The resulting structured phase shifts to the wavefront can be interpreted or processed for spatial pattern recognition, analog computation or embedded sensing. The wave may be optical, acoustic or mechanical, while the surface may be fabricated through lithography, embossing, 3D printing or programmable topological deformation. No external energy nor nonlinear media are required for operation beyond the original wave source. Devices may be static or tunable, using mechanical or material actuation to vary the modulation parameters. The modulation parameters—including the number of lobes and amplitude—may be tuned to control propagation behavior.

Acting as a geometric gate, the device supports direction-dependent modulation of optical signals without requiring electronic components, active materials or electronic gating, thus offering a purely spatial and analog alternative for wave-based logic and routing functions. The sinusoidal and radially symmetric geometry passively alters the phase and direction of the wavefront, enabling controllable transmission, reflection or redirection. The system supports analog computation, spatial routing and information encoding in optical, acoustic or mechanical systems. It can operate across a broad range of frequencies and wave types.

Different embodiments can be produced, each one supporting analog computational functions such as filtering, beamforming, edge detection, spatial delay, or wave-based logic operations. In one embodiment, a three-dimensional surface can be fabricated using the exact profile of a Plücker conoid. This physical realization may be scaled for different wavelengths, including microwaves, sound or visible light. In another embodiment, the Plücker modulation profile may be encoded into a flat metasurface using patterned phase delays, suitable for integration into photonic or acoustic chips. A third embodiment incorporates the PCIG structure into a wave-based neural computing element where modulated interference between multiple inputs results in output patterns for classification or transformation.

Statistical Analysis and Visualization. All statistical comparisons between plain and modulated wave behavior were carried out using Welch’s unequal variance t-test via scipy.stats.ttest_ind. For each metric, distributions of 20 simulation results were tested under the null hypothesis of equal means. The p-values were reported and interpreted using conventional thresholds for significance.

Visualizations were created using Matplotlib’s bar and boxplot functions. For overall comparison, metrics were normalized into arbitrary units and displayed with and without log-scaling. In log-scaled figures, values were plotted with a logarithmic y-axis to emphasize magnitude differences. No smoothing or curve fitting was applied to ensure that raw results were visible. All values reported in figures represent empirical means over 20 independent simulations per condition. This statistical and visualization strategy ensured consistency and clarity in reporting simulation-derived findings, completing the methodological pipeline used in the study.

Results

The results from 40 independent simulations for each geometry revealed statistically significant differences across all wave modulation metrics (

Figure 3).

Phase control, quantified via the variance of phase deviation between modulated and unmodulated wave fields, was significantly higher for the Plücker-modulated case (mean variance = 0.414, SD = 0.015) than for the plain wave, which had near-zero variance by design (p < 0.001).

Signal coherence, measured as the normalized cross-correlation between modulated and unmodulated wavefields, was also significantly different (mean = 0.758 for Plücker-modulated, SD = 0.005; mean = 1.0 for plain wave, SD ≈ 0.0; p < 0.001), indicating partial but non-negligible coherence loss.

The entropy of the energy field, used to assess spatial localization, was significantly lower for Plücker waves (mean = 5.96) compared to the plain case (mean = 6.32; p < 0.001), confirming more focused energy patterns.

Perturbation sensitivity, interpreted as wavefront stability, was also lower for the plain wave (mean squared deviation = 0.0058) than for the modulated surface (mean = 0.0239; p < 0.001), reflecting the increased structural reactivity of the modulated field.

These differences in basic wave behavior established the distinct physical character introduced by the Plücker phase modulation and formed a coherent basis for further structural analysis of the geometry-induced signal properties. Further metrics revealed divergence in frequency, directional and spatial pattern characteristics.

Modulation bandwidth, defined as the standard deviation of the spatial frequency spectrum, was broader in the Plücker-modulated case (mean = 7.71) than the plain configuration (mean = 6.05; p < 0.001), indicating higher frequency richness.

Gradient-based velocity control, used as a proxy for phase delay manipulation, was also greater under modulation (mean = 0.495 vs. 0.337; p < 0.001).

Interference complexity, measured as the number of spectral components above a normalized threshold, was significantly higher for the Plücker geometry (mean = 3191 vs. 2525;

p < 0.001). See

Figure 4.

Spatial uniformity, estimated via the inverse of wave amplitude standard deviation, was higher in plain waves (mean = 1.37) than in modulated waves (mean = 0.94; p < 0.001), confirming that modulation introduces nonuniform patterns.

The modulation depth (amplitude range) was wider in Plücker waves (mean = 1.97) than plain (mean = 1.72; p < 0.001).

Information density, calculated as the number of zero crossings in the wavefield, showed an increase from 47456 (plain) to 50769 (modulated; p < 0.05), reflecting a denser signal structure.

Overall, these measurements provide a comprehensive quantification of the effects induced by geometrically imposed phase modulation, capturing the spatial and spectral consequences in terms of both dynamic and structural signal attributes and demonstrating reproducible and statistically robust effects across both spatial and spectral domains.

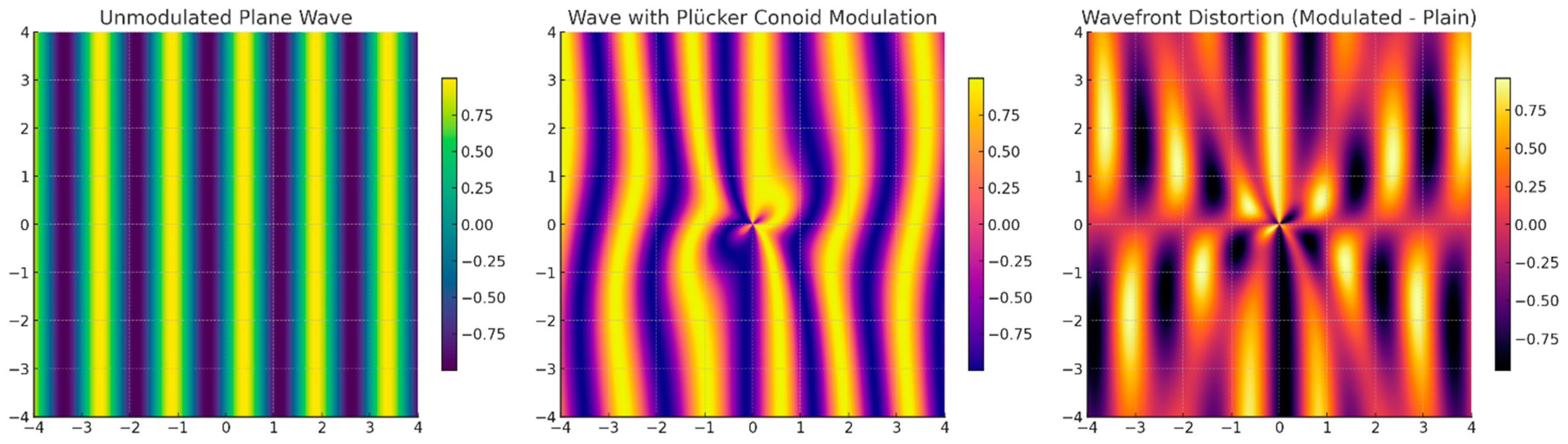

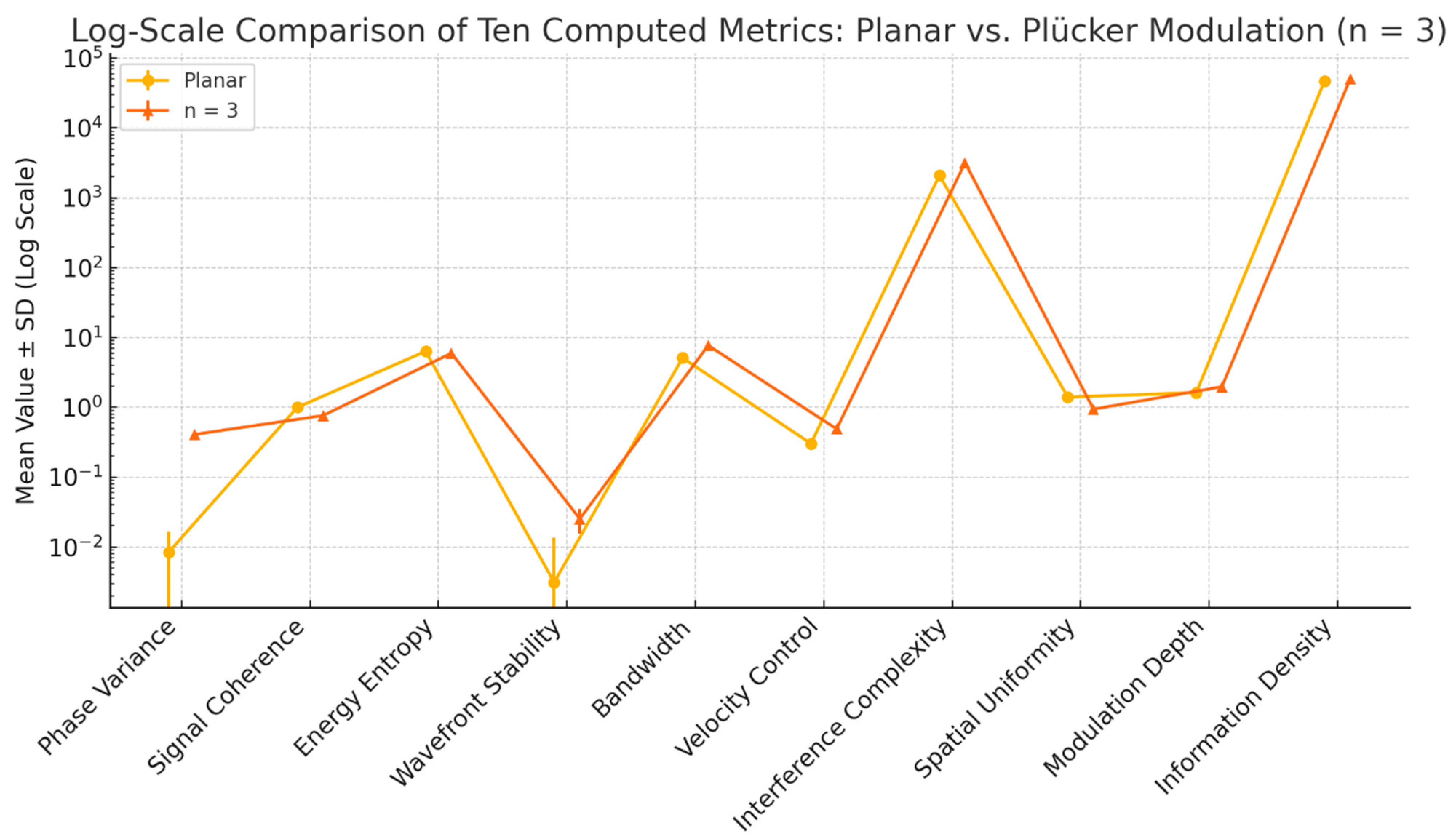

Next, we conducted simulations to determine the optimal modulation number for achieving the best computational performance in an optical transistor. Across forty independent simulations for each configuration—planar propagation, and Plücker conoid-inspired geometries with modulation numbers

n=2,

n=3 and

n=4—statistical comparisons confirmed highly significant differences in all ten evaluated metrics (

Figure 5). Compared to the planar case, all modulated geometries showed dramatic increases in phase variance (

p < 0.001), spectral bandwidth (

p < 0.001), velocity control, interference complexity and modulation depth, reflecting enhanced spatial modulation and directional asymmetry. At the same time, energy entropy decreased significantly (

p < 0.001), indicating more localized energy distributions, while signal coherence and spatial uniformity were both significantly reduced (

p < 0.001), highlighting the geometric modulation’s effect on correlation and homogeneity.

The comparison between n=2, n=3 and n=4 geometries revealed a monotonic progression in modulation strength, with phase variance, bandwidth and modulation depth increasing steadily with n, each with p-values below p < 0.001. However, the higher values of n also yielded sharper declines in coherence and stability, with n=4 producing the greatest complexity at the cost of increased wavefront perturbation and reduced uniformity. Specifically, coherence between n=3 and n=4 dropped significantly (p < 0.001) and stability degraded further (p = 0.05), reflecting amplified reactivity to phase interference. Overall, while all modulated configurations outperformed the planar baseline across key computational parameters, the geometry with n=3 provides the optimal trade-off, achieving significant enhancements in modulation performance—high phase diversity, spectral enrichment, and energy localization—while retaining better coherence and spatial regularity than the more aggressive n=4 configuration. This balance makes n=3 the most computationally effective modulation profile in terms of structured wave control and analog information encoding.

Overall, our simulations confirmed significant modulation-induced differences in all evaluated metrics. Each parameter demonstrated a statistically robust response to Plücker modulation.

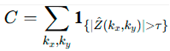

Figure 4.

Wavefront distortion in different waves. Left: A planar wave propagating in the x-direction exhibits uniform, parallel phase fronts, characteristic of unmodulated wave behavior. Center: Wave propagation subjected to Plücker conoid-inspired phase modulation displays angular asymmetry and interference effects, indicating spatially varying phase influence. Right: The differential wavefront map, computed as the pointwise difference between modulated and unmodulated fields, visualizes spatial phase deviations and coherence disruption induced by the underlying geometric modulation.

Figure 4.

Wavefront distortion in different waves. Left: A planar wave propagating in the x-direction exhibits uniform, parallel phase fronts, characteristic of unmodulated wave behavior. Center: Wave propagation subjected to Plücker conoid-inspired phase modulation displays angular asymmetry and interference effects, indicating spatially varying phase influence. Right: The differential wavefront map, computed as the pointwise difference between modulated and unmodulated fields, visualizes spatial phase deviations and coherence disruption induced by the underlying geometric modulation.

Figure 5.

Log-scale comparison of ten computed metrics across modulation geometries. Each curve represents the mean from 40 simulations for planar propagation and Plücker conoid modulations with n=2, n=3 and n=4. The logarithmic scale points towards clear distinctions across configurations, highlighting the progressive increase in spectral richness, phase complexity and modulation depth with higher n, as well as corresponding reductions in coherence and uniformity.

Figure 5.

Log-scale comparison of ten computed metrics across modulation geometries. Each curve represents the mean from 40 simulations for planar propagation and Plücker conoid modulations with n=2, n=3 and n=4. The logarithmic scale points towards clear distinctions across configurations, highlighting the progressive increase in spectral richness, phase complexity and modulation depth with higher n, as well as corresponding reductions in coherence and uniformity.

Conclusions

Quantitative Impact of Plücker Modulation on Wave Behavior. Our analysis conducted through twenty independently randomized simulations established clear, statistically significant differences between unmodulated plane wave propagation and waveforms modulated using a Plücker conoid-inspired geometry. Key metrics revealed distinctive dynamic and structural signatures associated with the Plücker surface. Among its most critical benefits is the ability to deliver passive phase control: indeed, phase variance increased substantially in the modulated case, enabling effective spatial information encoding through geometry alone. Signal coherence decreased modestly, suggesting that the modulation introduced sufficient structural transformation to alter, but not destabilize, waveform correlation. Spectral enrichment is another key strength, with modulation bandwidth increasing from a planar baseline, supporting enhanced signal resolution and complexity. The conoid geometry also promotes energy localization, as evidenced by a reduction in energy entropy, which is essential for spatially targeted computation and reduced cross-talk. Furthermore, Plücker modulation increases both modulation depth and information density, reflecting a richer and more expressive encoding of data. These combined results confirm that Plücker-based modulation introduces phase diversity, concentrates energy and enriches frequency content. Simultaneously, spatial uniformity and coherence were moderately reduced, reflecting a trade-off consistent with physically meaningful signal transformations. Overall, the consistent reproduction of statistically significant effects across a broad range of metrics confirms that Plücker-based modulation produces a distinct computational impact while preserving numerical stability and structural coherence, indicating a high degree of consistency, generalizability and robustness.

Comparison with Electronic Computation. Semiconductor-based electronic computers are limited by heat dissipation, energy efficiency and signal delay at nanoscales, particularly as transistor densities approach physical limits. Interconnect bottlenecks and clock synchronization also constrain performance in highly parallel architectures. Unlike these systems, the Plücker conoid approach operates through passive geometric modulation of waves, enabling parallel, analog signal processing without active switching or energy loss from charge transport. While electronic computers offer high precision and programmability, Plücker-based systems provide scalable, low-energy alternatives for spatial computation. Plücker conoid-inspired modulation may offer advantages in computational wave systems by enabling structured, passive and deterministic control of wave behaviour. The benefits are all achieved through scalable and material-independent geometric shaping, with no need for electrical power or nonlinear materials, making the approach especially attractive for low-energy, geometry-driven spatial computing. The geometry imposes nontrivial phase shifts without relying on active materials or external energy sources, making it well-suited for analog, optical, acoustic, and neuromorphic computing contexts.

Comparison with Existing Optical Modulation Techniques. While optical transistors have traditionally relied on active materials, dynamic components or external energy sources—such as gain modulation, absorption tuning, nonlinear susceptibilities (Nardone and Mandel 1986; Matthaiakakis et al., 2017)—the use of Plücker conoid geometry introduces a passive alternative. Optical and acoustic computing systems, though promising, are constrained by diffraction, coherence loss and limitations in spatial resolution. Optical platforms require costly materials and tight alignment tolerances, while acoustic systems face slower propagation speeds and bulkier wavelengths. Both struggle with real-time adaptability and scalable geometric control. In contrast, Plücker conoid-based modulation enables deterministic wave shaping using fixed, passive structures, with no need for refractive index variation or active tuning. It supports enhanced spectral bandwidth and directional control, both critical for wave-based computing. Though less experimentally developed, our approach promises simpler fabrication and easier integration into hybrid analog architectures, where geometry-driven phase control can play a foremost role.

Modulation Geometry and Its Computational Uniqueness. Embedding sinusoidal phase modulation based on a Plücker conoid imposes a structured, rotationally symmetric distortion on wavefields that differs from random or linear phase modulations. Unlike conventional lensing or planar phase gratings, Plücker modulation combines radial symmetry with directional anisotropy, producing a compound transformation of the wavefront. The resulting phase modulation is smooth, continuous and periodic, avoiding the discontinuities and singularities typical of more aggressive shaping methods. Compared to alternative geometries such as linear chirps, sinusoidal strips or radial Gaussian profiles (Capus et al., 2000), the Plücker conoid induces a controlled, multidimensional alteration in wavefront topology. This leads to structured energy localization and enhanced spatial complexity, evidenced by entropy reduction, richer spectral content and increased zero-crossing density. Remarkably, these effects mimic nonlinear propagation characteristics—such as asymmetric interference and localized energy concentration—yet arise purely from geometric phase control in a linear medium, without any nonlinear materials.

Limitations and Boundary Conditions. Several limitations merit consideration. First, all simulations were conducted in a two-dimensional spatial domain using idealized sine wave formulations and static snapshots. While this allows for clear comparisons under controlled conditions, it omits the temporal evolution and three-dimensional propagation effects that occur in physical systems. The choice of noise amplitude and perturbation scale, while reasonable, introduces an implicit parameter sensitivity that may vary under different wave frequencies or boundary conditions. Moreover, the simulation assumed homogeneous media and did not account for inhomogeneities, reflections or nonlinearities that may alter wave behavior in real-world materials. In physical implementations, material imperfections, phase wrapping effects and fabrication constraints could reduce the fidelity of the theoretical model. Additionally, while we used statistical metrics that are standard in wave physics and signal processing, some metrics—such as interference complexity and zero-crossing density—may benefit from further theoretical grounding or alternative normalization schemes for broader comparability. Lastly, all statistical tests were applied under the assumption of independent, identically distributed trials, which may not generalize directly to hardware variability. These constraints suggest that our framework’s extension to physical realizations should proceed with careful attention to material and temporal parameters.

Computational Potential and Domain-Specific Use Cases. Compared with semiconductor-based electronic computers, our Plücker conoid approach lacks general-purpose flexibility and digital logic depth, making it complementary rather than replacement for semiconductor-based architectures in specific computing domains. Still, Plücker-based systems could become the gold standard in areas that demand precise wave manipulation, passive analog computation and ultra-low power operation. In photonic or acoustic circuits, they may enable structured signal routing, filtering and transformation without requiring active materials or external energy inputs. Their ability to shape phase and interference patterns through geometry alone makes them ideal for spatial computing tasks such as image processing, pattern recognition and analog transformation, where digital architectures are either inefficient or overly complex. In neuromorphic systems, Plücker modulation supports distributed, parallel signal interactions that resemble biological computation, offering an alternative to conventional logic gates. These systems are particularly well suited for reconfigurable metasurfaces and embedded sensor arrays, where wave behaviour must be guided or processed locally without centralized control. In extreme environments such as underwater, aerospace, or infrastructure monitoring, where reliability and power constraints dominate, the passive and geometry-driven nature of Plücker-based platforms offers resilience and efficiency. Their physical simplicity and compatibility with wave-based modalities position them as a compelling architecture in domains where computation is spatially embedded, inherently parallel, and physically constrained.

Future Research Directions. Given the measurable effects observed in structured wavefields, our approach motivates several lines of future research. First, extending the simulations to three dimensions and incorporating full time-domain wave propagation would allow the study of dynamic effects such as dispersion, reflection and group delay in modulated wave packets. Time-dependent models could also investigate how modulated wavefronts interfere in multilayered or feedback-driven systems. A natural direction is the construction of experimental analogs using deformable membranes, acoustic plates or photonic lattices fabricated to mimic the Plücker modulation function. This would enable direct empirical verification of energy localization and coherence behavior. The structural regularity of the Plücker conoid lends itself to lithographic or programmable fabrication techniques, making experimental testing feasible. Additionally, future research could explore adaptive or tunable versions of this geometry, for example, by changing the modulation parameter aaa or the number of lobes nnn in real time to manipulate interference or delay patterns. Other analytical directions include combining Plücker modulation with external potential fields or embedding it within active systems to produce nonlinear wave control. New testable hypotheses include whether energy localization in the Plücker-modulated case correlates with modal concentration in bounded domains and whether group delay effects can be tuned by modifying modulation parameters. Further, interference fringe spacing could be measured and compared with predictions from FFT complexity metrics. Researchers may also compare the modulation effects of Plücker geometries with hyperbolic, toroidal or ellipsoidal surfaces to isolate the role of ruling and sinusoidal wrapping.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the primary objective of this study was to determine whether geometrically embedded phase modulation inspired by the Plücker conoid could produce consistent and quantifiable differences in wave behavior across multiple independent simulations. The answer, based on comprehensive numerical evidence and statistical analysis, is affirmative. Every simulated metric showed a statistically significant divergence between plain wave and Plücker-modulated geometries. The key take-away is that Plücker modulation is not merely a visual or geometric transformation, rather it creates measurable, structured impacts on phase control, spatial energy distribution, frequency complexity and signal coherence. These effects are reproducible, interpretable and distinct from unmodulated systems.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Afzal, Ayesha, Georg Hager, and Gerhard Wellein. The Role of Idle Waves, Desynchronization, and Bottleneck Evasion in the Performance of Parallel Programs. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2023, 34, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdallah, Abderazek, and Khanh N. Dang. Neuromorphic Computing: Principles and Organization. 2nd ed. Cham: Springer, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D., T. L. Harte, V. Chardonnet, C. De Groot, S. J. Denny, G. Le Goc, M. Anderson, P. Ireland, D. Cassettari, and G. D. Bruce. High-Fidelity Phase and Amplitude Control of Phase-Only Computer Generated Holograms Using Conjugate Gradient Minimisation. Optics Express 2017, 25, 11692–11700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capus, C. Y. Rzhanov, and L. Linnett. 2000. The Analysis of Multiple Linear Chirp Signals. Paper presented at IEE Seminar on Time-scale and Time-Frequency Analysis and Applications (Ref. No. 2000/019), February 29. London: IET. [CrossRef]

- Crocker, Matthew W. , Vera Demberg, and Elke Teich. Information Density and Linguistic Encoding (IDeaL). Künstliche Intelligenz 2016, 30, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Chaoran, Bhavin Shastri, and Paul Pruncal. Photonic Computing: An Introduction. In Phase Change Materials-Based Photonic Computing, 37–65. Materials Today, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Malik, Wasim Q. , Leigh R. Hochberg, John P. Donoghue, and Emery N. Brown. Modulation Depth Estimation and Variable Selection in State-Space Models for Neural Interfaces. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2014, 62, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaiakakis, N. , Xingzhao Yan, H. Mizuta, and M. D. B. Charlton. Tuneable Strong Optical Absorption in a Graphene-Insulator-Metal Hybrid Plasmonic Device. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, Peter L. The Physics of Optical Computing. Nature Reviews Physics 2023, 5, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, P. and P. Mandel. 1986. Dynamic Gain of an Optical Transistor. In Optical Bistability III, edited by H. M. Gibbs, P. Mandel, N. Peyghambarian, and S. D. Smith, 158–164. Springer Proceedings in Physics, vol. 8. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Peternell, Martin, Lukas Gotthart, J. Rafael Sendra, and Juana Sendra. The Relation Between Offset and Conchoid Constructions. arXiv (2013).

- Praveena, Nalamani G., Kandasamy Selvaraj, David Judson, and Mahalingam Anandaraj. Low Complexity Ordered Successive Interference Cancelation Detection Algorithm for Uplink MIMO SC-FDMA System. ETRI Journal 2022. [CrossRef]

- Radzevich, S. P. A Possibility of Application of Plücker's Conoid for Mathematical Modeling of Contact of Two Smooth Regular Surfaces in the First Order of Tangency. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2005, 42, 999–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzevich, S. P. Plücker Conoid: More Characteristic Curves. In Geometry of Surfaces, 137–158. Cham: Springer, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, David, Ignacio Santamaría, and Louis Scharf. Coherence: In Signal Processing and Machine Learning. Cham: Springer, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Velivela, Pavan Tejaswi, and Yaoyao Fiona Zhao. Supporting Multifunctional Bio-Inspired Design Concept Generation through Case-Based Expandable Domain Integrated Design (xDID) Model. Designs 2023, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Shuyu, Qi Wei, Ye Tian, Ying Cheng, and Xiaojun Liu. Acoustic Analog Computing System Based on Labyrinthine Metasurfaces. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 10103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).