Introduction

Despite the World Health Organization’s declaration of the end of the public health emergency on May 11, 20231, people around the globe continue to get sick and die from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). As of September 14, 2024, 60,769 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) related deaths have been reported across Canada, with 5,997 in the most recent 365 days2.

Healthcare providers (HCP) continue to provide care to patients with COVID-19, but for some this care comes with a long-term emotional cost. Previous literature has shown that public health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can lead to symptoms of emotional distress (e.g., depression and anxiety) as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in HCP 3. Meta-analyses have estimated that 22-33% of HCP across the globe experienced depression, 35-41% reported anxiety, and 21-32% had symptoms of PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic4, 5. One study found that 20-23% of Canadian HCP felt anxious, irritable, isolated, or depressed to a “great extent” between April 2020 and February 2022, with the highest estimates for each outcome occurring in March through June 20214.

However, not all HCP respond to the added physical and emotional demands associated with caring for those with COVID-19 in the same manner. According to Wang et al.6, the impact of a traumatic event differs depending on the event itself (intensity and duration) as well as the individual’s perception of the event, personal psychological defense mechanism(s), and support system(s). One systematic review reported that 18-80% of HCP reported psychological distress during outbreaks caused by caused by SARS-CoV-1, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), influenza A(H1N1pdm or H7N9), SARS-CoV-2, or the Ebola virus 7.

The 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) is a ten-question scale to screen for psychological distress that has been shown to discriminate well between cases and non-cases of serious mental illness as defined by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration 8. It has also been used to assess stress in HCP. Two studies conducted with HCP in Canada during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic reported rates of distress, as measured by the K10, of 74% in 2020 9 and 70% in 2021 10.

A review of responses to potentially traumatic events reported that the most frequently reported trajectories of symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression, subjective well-being, life satisfaction, psychological functioning, and distress were: 1) resilient, indicating consistently normal scores; 2) chronic, with persistently elevated scores; 3) recovery indicating an elevated score immediately following the experience with a return to normal score(s); 4) delayed-onset, with initially normal scores followed by elevated score(s); and eight other trajectories that were observed with lower frequency 11. These authors also found that personal characteristics (e.g., age, sex, personality, coping styles) and exposure intensity may impact the response to the traumatic event. The four most frequently observed emotional health trajectories were also identified by Bonanno et al., using the Medical Outcome Study short form health survey (SF-12), among people who had been hospitalized for SARS-CoV-112. Likewise, Hyland et al.13 reported the same four trajectories as measured by a composite score of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress in a representative sample of the Irish adult population during the COVID-19 pandemic (April to December 2020).

PTSD is a mental health disorder that may occur after someone is exposed to what they perceive as traumatic stress that can lead to chronic impairment and increased risk of co-occurring psychiatric conditions14. PTSD is defined as the presence of symptoms for one or more months; however, symptoms may last for varying lengths of time and may not become apparent for six months or longer15. A meta-analysis of HCP with PTSD symptoms following outbreaks or pandemics caused by SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, influenza A(H1N1pdm and H7N9), SARS-CoV-2, or the Ebola virus found that 18.6-28.4% still had PTSD symptoms after 30 days, 17.7% after six months, and 10-40% after one to three years7. A second meta-analysis focusing on the SARS-CoV-1 pandemic determined that 16% of HCP reported PTSD symptoms during the pandemic, 19% within six months, and 8% more than 12 months afterwards16. A Canadian study that was part of that meta-analysis found that 13-26 months after the outbreak, HCP who had provided care to patients infected with SARS-CoV-1 reported significantly higher levels of post-traumatic stress, as measured with the 15-item Impact of Event Scale17, and psychological distress, as measured by the K10, than HCP who did not18.

Canadian HCP participating in theCOVID-19 Cohort Study during the pandemic had a rate of distress, as measured by the K10, of 70% in 2021 that dropped to 49% in 202319. In this same study, it was noted that among patient-facing HCP, 48% and 45% of participants had symptoms at levels of concern for PTSD in 2021 and 2022, respectively, but the rate dropped to 22% in 2023 10. Although these studies provide rates over time, they fail to describe whether the patterns of distress were experienced differently by individuals.

The goal of this explanatory study was to assess the association between non-specific emotional distress trajectories as measured by the K108 and PTSD symptoms as measured by the IES-R20 among Canadian HCP participating in the COVID-19 Cohort Study between March 2021 and December 2023.

Design and Methods

This analysis is a sub-study of the COVID-19 Cohort Study, a 42-month pan-Canadian (Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, Alberta) prospective study that focused on determining the incidence and risk factors for infection with COVID-1921. In short, enrollment occurred from June 2020 to June 2023 with data collection ending upon participant withdrawal or study termination (December 1, 2023), whichever occurred first. Prior to recruitment, ethical approval was obtained from each of the 14 participating acute care centres. HCP were eligible for the parent study if they were 18 to 75 years old at enrolment, provided written consent, were hospital employees who worked ≥20 hours per week, or were a physician, nurse practitioner, or midwife with hospital privileges or a private practice in Toronto. Participation was voluntary.

For this sub-study, inclusion criteria were COVID-19 Cohort Study participants who submitted their first K10 between March 29, 2021 and March 28, 2022, submitted four K10 surveys with 180 (±60) days between subsequent submissions (minimum study participation: 545 days), and submitted an IES-R at study withdrawal/completion. Incomplete K10 or IES-R scales were excluded from the analysis.

All data were collected anonymously using a secure online platform. Baseline data were collected at enrolment with time-varying measures updated by participants every 12 months. All HCP participants were asked to complete a K10 survey at study inception (March 2021) or upon their recruitment (whichever came first) and every six months thereafter. Participants were asked to complete the IES-R within two weeks of their withdrawal from the study or study termination date.

Explanatory Variable (K10 Score)

The K10 is a widely used screening tool of emotional distress22 that has been used to measure the frequency of non-specific symptoms of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic10. Previous research has established the reliability and validity of the K1023-26. Items were scored from one (none of the time) to five (all of the time) with possible scores of 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater distress. These analyses used a score of ≥16 to identify those most likely to be experiencing distress18.

Outcome Measure (IES-R Score)

The IES-R is a psychometrically sound and widely used measure of PTSD symptoms27 that asks participants to indicate how distressing each of 22 difficulties was during the past seven days on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely)20. For this study, the IES-R was introduced with “You have been working throughout the COVID-19 pandemic”. The IES-R cut offs for this analysis were 0-23 (no concern for PTSD/normal) and ≥24 (indicative of concern for PTSD)20 with three categories of concern including 24-32 (mild), 33-36 (moderate), and ≥37 (severe). Subscale scores (avoidance, intrusion, hyperarousal) are the mean of the subscale item scores (range 0 to 4).

Study Covariates

Participant age, gender, and the use of prescription medications for anxiety, depression, or insomnia were collected from the baseline survey completed at enrolment. Other demographic (any children <19 years of age in the household) and occupational factors (occupation, working on a high-risk unit, level of patient contact) that could vary over time were taken from the baseline survey completed closest, but prior to, the fourth K10 completion date. Individuals who indicated that they worked in the emergency department, on an adult intensive care unit or an adult inpatient medical unit were identified as working on a high-risk unit; other work locations were identified as lower risk. The level of contact participants had with each of inpatients, outpatients, and emergency department patients were categorized into the highest level of contact in any of the three settings as (1) no patient care, (2) in patient room, but no patient contact, or (3) physical care/contact. Since nurses have been identified as being more likely to report symptoms of PTSD 28, occupation was dichotomized to nurse (nurse practitioner, midwife, registered nurse/registered practical nurse) or non-nurse (physician, respiratory therapist, laboratory technician, physical therapist, occupational therapist, imaging technician/technologist, pharmacist, pharmacy technician, psychologist, social worker, infection prevention and control practitioner, food service, ward clerk, administration, healthcare aid, housekeeper, porter, researcher, other clinical support).

Data Analysis

Change patterns in the four dichotomized K10 scores (<16 vs ≥16) were explored to determine distinct emotional response trajectories using the four trajectories described by Galatzer-Levy et al.11 as a starting point; they included 1) resilient: all four K10 scores <16, 2) chronically distressed: all four scores ≥16, 3) delayed onset: first score(s) <16 followed by score(s) always ≥16, and 4) recovery: first score(s) ≥16 followed by score(s) of <16. All other trajectories were categorized as mutable since they fit none of the score patterns.

Chi-square, Fisher’s exact tests, or median tests, as appropriate, were used to compare the demographic and occupational characteristics associated with each of the categories. Modified Poisson regression29 was then used to assess the relationship between the K10 trajectories and IES-R scores (0-23 vs ≥24). Possible demographic and occupational confounding variables were eliminated from a saturated model retaining covariates associated at p-values of ≤0.2. Covariates that were removed were added back in, one at a time, being retained if the variable changed the adjusted estimate between the trajectory and the IES-R score by ≥10%. All variance estimates were adjusted for clustering within province and all models were adjusted for the time between the completion of the fourth K10 survey and the IES-R (per 30-days). Negative binomial models of each of the IES-R subscales that included the variables identified in the previous analysis were then generated using the same procedures as described above. All analyses were done in Stata (v.18)30.

Results

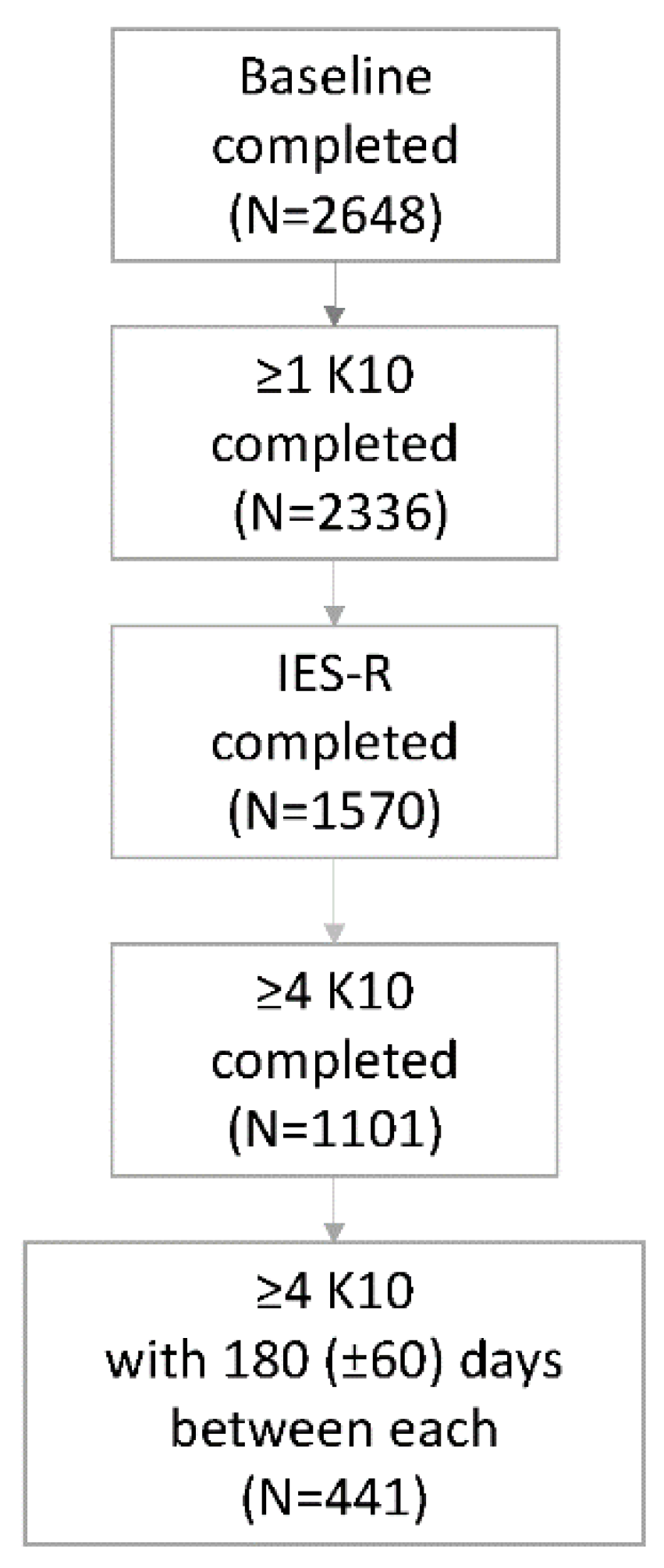

Of the 2648 HCP who participated in the parent study, 441 (16.7%) met the sub-study inclusion criteria (see

Figure 1). The first K10s were completed between March 29, 2021 and March 7, 2022 while the fourth K10s were completed July 4, 2022 to November 6, 2023. Most (n=384, 87.1%) IES-R scales were completed in 2023; there was an average of 179 (±18) days between submission of the fourth K10 and the IES-R. The majority (n=385, 87.3%) of sub-study participants were female, 138 (31.3%) were nurses, 316 (71.1%) reported very good or excellent health, 116 (26.3%) worked on a high-risk unit, and 88 (20.0%) reported using medication to treat anxiety, depression or insomnia at study enrolment (

Table 1).

The participants in this sub-study are similar to those in the full study that was largely (85.1%) female; 33.0% were nurses; 75.0% reported very good or excellent health; 31.1% worked on a high-risk unit; and 18.1% used medication to treat anxiety, depression or insomnia. Further, in this sub-study, 43.5% (95% CI 38.5, 48.5) had an average K10 score of ≥16 in 2023, which is similar to the rate (49%; 95% CI 44.4, 54.0) reported in our study of K10 scores10. Similarly, 21.9% (95% CI 18.0, 26.2) of participants in this sub-study had IES-R scores of concern in 2023; this is very similar with the 22.5% (95% CI 18.1, 27.5) reported in 2023 in our study of HCP engaged in patient care19.

Five K10 trajectories of psychological response to working during the COVID-19 pandemic were identified including resilient (n=111, 25.2%), chronically distressed (n=131, 29.7%), delayed onset (n=43, 9.8%), recovery (n=83, 18.8%), and mutable (n=73, 16.6%). As shown in

Table 1, the median K10 score varied significantly by trajectory from 11.8 (resilient) to 23.8 (chronically distressed).

Concern for PTSD

The percentage of participants whose IES-R score was >24 (of concern for PTSD) varied significantly different across K10 trajectories, ranging from 6.3% for HCP in the resilient group to 42.7% in the chronically distressed group (see

Table 2).

Emotional Distress and Concern for PTSD

HCP whose K10 scores were

not considered resilient had significantly higher risks of having IES-R scores indicative of concern for PTSD. The adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) for those whose trajectories were considered chronically distressed was 6.9 (3.7, 13.0) times higher than for those whose K10 scores were resilient, after adjusting for occupation, province of work, and number of days between the submission of the fourth K10 and the IES-R (see

Table 3). Participants in the other three K10 trajectories were also at higher risk of IES-R scores of concern for PTSD as compared to those with resilient scores, with aIRRs of 2.6 (delayed onset), 3.1 (recovery), and 4.0 (mutable).

Subscale Models

Subscale Kendel’s tau correlations varied from 0.69 (hyperarousal: intrusion) to 0.61 (hyperarousal: avoidance). As shown in

Table 2, symptoms of avoidance and intrusion were more common than those of hyperarousal. Among all regression models of K10 trajectories on IES-R subscale scores, the highest aIRR was associated with the comparison of the resilient group to the chronically distressed group while the lowest aIRR was associated with the comparison of participants in the resilient and the recovery groups (see

Table 3).

Discussion

In this longitudinal cohort study of Canadian HCP, five trajectories of psychological responses to working during the COVID-19 pandemic were detected, as measured using the K10. These trajectories were associated with the risk of having a score indicative of concern for PTSD (i.e., ≥24 as measured with the IES-R). The relative risk of scoring in the ‘of concern’ category of the IES-R was seven times higher for the 30% of HCP whose K10 scores were consistently ≥16 (i.e., chronically distressed) than for those who scores were consistently below that cut-off. The risk of having IES-R scores of concern was significantly higher for HCP in other non-resilient trajectories as well, with relative risks 2-4 times higher. Twenty-four percent of HCP who participated in this study had symptoms at a level indicative of concern for PTSD; 13% had severe symptoms as assessed by the IES-R, demonstrating the considerable long-term emotional health impact of the pandemic among HCP. Given that there are an estimated 2.0 million people working in healthcare in Canada31, these findings suggest that up to 260,000 Canadian HCP may be in need of psychological assistance.

A temporal relationship between emotional distress and symptoms of PTSD was reported by Laurent et al.32 during the first peak of the pandemic in France. They found that the odds of having symptoms of PTSD (IES-R score >33) were 1.4 times higher for intensive care unit staff who had scores indicative of distress than those with lower scores, as measured three months earlier using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Although the odds of having symptoms of PTSD were lower in the French study than in the current one, there are significant differences in study design including the period and duration of data collection, the measure of distress, and the threshold used for the IES-R.

A single assessment can identify HCP who are (or are not) distressed at the time of the measurement. However, as our study highlights, individual levels of distress during a prolonged traumatic event may not be static; repeated assessments are needed to identify people whose levels of distress change over time. Other studies conducted with HCP also report changes in the rates of distress as assessed early in the pandemic and over shorter periods of assessment. Rapisarda et al.33 asked Canadian HCP to complete questionnaires to measure distress for eight consecutive weeks between May 2020 and January 2021. In that study, 53% of HCP were deemed resilient while 34% exhibited short-term distress (<4 weeks) and 13% had longer-term distress (≥4 weeks). Roberts et al.34 studied front-line physicians’ level of distress and trauma over a 16-week period (March to June 2020) during the first wave of the pandemic in the United Kingdom. They reported that the incidence of distress, measured using the GHQ-12, was 45% during the initial increase in COVID-19 cases, 37% during the peak, and 32% when case counts were waning; patterns of individual trajectories were not reported. A similar study conducted among Canadian intensive care unit staff found that clinically relevant distress, using the GHQ-12, was experienced by 62%, 40%, and 31% of respondents during the increase, peak, and waning phases of the first wave of the pandemic 35. Of the 62% of participants who initially reported distress, 45% were persistent while 55% recovered. Fattori et al.28 reported that Italian HCP who completed two assessments (July 2020-July 2021 and July 2021-July 2022) showed differences using the GHQ-12. Forty-three percent of HCP in that study scored below the threshold of clinical concern at both periods, 14% were chronically distressed, 9% had delayed onset, and 34% recovered. The rates of distress vary considerably between studies which is not unexpected given the differences in study methods. However, the findings are consistent in that levels of distress change over time making it important to monitor them at regular intervals during a protracted event such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Assessment should also continue long after the end of a prolonged traumatic event such as the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown by Maunder et al., pandemics can have long-lasting impacts on some HCP18. In their study, more than 40% of HCP who had worked at a hospital that provided care to people hospitalized with SARS-CoV-1 experienced adverse outcomes including burnout, psychological distress, post-traumatic stress and work-related impacts such as missed work shifts due to stress or illness more than 18 months after the pandemic had ended18. A systematic review and meta-analysis similarly reported that the prevalence of PTSD among HCP was 16% during the SARS-CoV-1 pandemic and 8% more than one year later16. Maunder et al. suggest that HCP be given time and space for reflection that brings attention to effective, available coping strategies36. These investigators also suggest that leadership need to recognize the importance of maintaining staff resilience and to provide infection control training, reassurance that jobs won’t be lost due to illness/leaves, and access to adequate supplies of personal protective equipment to help alleviate distress.

In our study, participants whose K10 scores indicated a chronically distressed trajectory were at the highest risk of IES-R scores indicative of concern for PTSD and for each of the IES-R’s subscale scores (hyperarousal, intrusion, and avoidance). Moallef et al.37 also examined levels of depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology following the SARS-CoV-1 pandemic among Toronto-based HCP who had contracted SARS-CoV-1 and survived. These investigators found that 59% of participants scored above the scale’s cut-off for PTSD seven years after infection, demonstrating the wide-reaching long-term impact of pandemics. For example, correlations between PTSD subscale scores and functional outcomes showed that higher hyperarousal scores in 2004 were associated with lower social functioning in 2007 as well as decreased overall well-being in 2007 and 2010 and decreased physical functioning in 2010. Meanwhile, avoidance scores in 2004 were associated with lower personal well-being and social functioning in 2007. These findings suggest the need to focus long-term attention on those who have chronic distress and elevated hyperarousal and/or avoidance scores.

We recognize that there are limitations to this study. Although the questionnaires were completed anonymously, the findings are based on self-reported data that may be subject to over- or under-reporting of symptoms. The data for the K10 and IES-R were collected between February 2021 and December 2023, so results cannot be generalized beyond those dates. The IES-R was only collected once, at the end of the participant’s tenure, so the temporal relationship between PTSD symptoms and trajectories of general distress cannot be known. This analysis identifies important vulnerable groups, those with non-resilient K10 trajectories and high PTSD scores long into the pandemic but does not clarify the relationship between those variables. Also, although participants were from four of the 13 provinces/territories in Canada, the hospitals were located in larger urban centres and participation was voluntary limiting generalizability to smaller sub-urban or rural settings, or to HCP at large. Further to this, participation in this sub-study was limited to participants who completed at least four K10s. As such, representation of HCP is further limited to those who were able to manage the added workload of participating in the study during the pandemic; these participants may not represent all HCP.

This study is one of few that assesses the temporal relationship between symptoms of distress and PTSD and despite the above-mentioned limitations, the study is unique in the duration of data collection (March 2021 to December 2023) and the scope of participation with HCP from 19 hospitals across four Canadian provinces and a variety of occupations. Also, the scales used to measure symptoms of distress and PTSD were validated and are used across the globe.

Conclusions

Although the majority of HCP did not experience chronic distress during the COVID-19 pandemic, about 40% reported chronic or delayed distress. Among those with chronic distress, the risk of having symptoms of PTSD were seven times higher than for HCP who had no symptoms of distress. These people need to be identified and supported. Studies of HCP with levels of distress of clinical concern during the COVID-19 pandemic need to be followed over a longer period to understand the multi-year impacts of working during this pandemic.

Authors’ contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: BLC, RM, AM; data curation: BLC, IG; formal analysis: BLC, IG; funding acquisition: BLC, AM, RM; methods: BLC; project administration: BLC; resources: BLC; supervision: BLC; validation: BLC; original draft: IG, BLC; review & editing: BLC, IG, RM, AM, CCS Working Group.

Funding statement

This study received funding from three sources: 1. the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [173212 & 181116]; 2. Physician Services Incorporated Foundation [6014200738]; and 3. the Weston Family Foundation [no number]. Please note that the Funders played no role in any aspect of data collection, analysis, or interpretation. Funding agencies were not involved in manuscript preparation and submission for publication.

Significance for public health

A better understanding of patterns of psychological responses to potentially traumatic events, including pandemics or other natural or man-made disasters, is essential so that future events are met with strategies aimed at preventing or mitigating adverse outcomes.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and

approved by the Research Ethics Boards of Sinai Health System (20-0080-E, 2020-04-17), Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (1644, 2020-04-13), Michael Garron Hospital (807-2004-Inf-055, 2020-04-29), North York General

Hospital (20-0017, 2020-05-06), University Health Network (20-5368, 2020-05-21), Unity Health Toronto (20-109, 2020-06-01), Oak Valley Health (121-2010, 2020-11-04), William Osler Health System (2020-12-18), Hamilton Health Sciences Centre (12809, 2020-12-31), St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton (13044, 2020-12-31), University of Alberta (Pro00106776, 2021-01-13), Nova Scotia Health (1026317, 2021-02-02), The Ottawa Hospital (20210024-

01H, 2021-02-05), and Centre hospitalier universitaire de Sherbrooke (MP-31-2021-4104, 2021-06-09).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

To ensure the privacy of research participants, datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available. Data files are available from Dr. Coleman upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The investigators thank their staff, who worked tirelessly throughout the study and the participants who gave freely of their time to advance knowledge while also working during the pandemic.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

References

- World Health Organization. Emergencies: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (2024, accessed 2024-08-22 2024).

- Government of Canada. COVID-19 epidemiology update: Summary, https://healthinfobase.canada.ca/covid-19/ (2022, accessed 13 May 2024 2024).

- Naushad VA, Bierens JJ, Nishan KP; et al. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Disaster on the Mental Health of Medical Responders. Prehosp Disaster Med. [CrossRef]

- Boucher VG, Haight BL, Léger C; et al. Canadian healthcare workers' mental health and health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from nine representative samples between April 2020 and February 2022. Can J Public Health 2023; 114: 823-839. 20230807. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK; et al. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res, 2020; 293: 113382. 20200811. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Wei Z, Yao N; et al. Association Between Sunlight Exposure and Mental Health: Evidence from a Special Population Without Sunlight in Work. Risk Manag Healthc Policy, 2023; 16: 1049-1057. [CrossRef]

- Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G; et al. The Psychological Impact of Epidemic and Pandemic Outbreaks on Healthcare Workers: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2020; 22: 43. 20200710. [CrossRef]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ; et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med, 2002; 32: 959-976. [CrossRef]

- Voth J, Jaber L, MacDougall L; et al. The presence of psychological distress in healthcare workers across different care settings in Windsor, Ontario, during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Front Psychol, 2022; 13: 960900. 20220829. [CrossRef]

- Gutmanis I, Coleman BL, Ramsay K; et al. Psychological distress among healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Patterns over time. BMC Health Serv Res, 2024; 24: 1214. 20241010. [CrossRef]

- Galatzer-Levy IR, Huang SH and Bonanno GA. Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev, 2018; 63: 41-55. 20180606. [CrossRef]

- Bonanno GA, Ho SM, Chan JC; et al. Psychological resilience and dysfunction among hospitalized survivors of the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: A latent class approach. Health Psychol, 2008; 27: 659-667. [CrossRef]

- Hyland P, Vallières F, Daly M; et al. Trajectories of change in internalizing symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal population-based study. J Affect Disord, 2021; 295: 1024-1031. 20210903. [CrossRef]

- Mann SK, Marwaha R and Torrico TJ. Posraumatic Stress Disorder. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024.

- Canadian Psychological Association. Traumatic stress section: Facts about traumatic stress and PTSD, https://cpa.ca/sections/traumaticstress/simplefacts/ (2024, accessed 2024-07-31).

- Alberque B, Laporte C, Mondillon L; et al. Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Healthcare Workers following the First SARS-CoV Epidemic of 2003: A Systematic Review and Meta-

Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19 20221011. [CrossRef]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N and Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. [CrossRef]

- Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE; et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006; 12: 1924-1932. [CrossRef]

- Gutmanis I, Sanni A, McGeer A; et al. Level of patient contact and Impact of Event scores among Canadian healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res, 2024; 24: 947. 20240820. [CrossRef]

- Weiss DS and Marmar, CR. The impact of event scale—Revised. In: Wilson J and Keane T (eds) Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. The Guilford Press, 1997.

- Coleman BL, Gutmanis I, Bondy SJ; et al. Canadian health care providers' and education workers' hesitance to receive original and bivalent COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine, 2024; 42: 126271. 20240902. [CrossRef]

- Stolk Y, Kaplan I and Szwarc J. Clinical use of the Kessler psychological distress scales with culturally diverse groups. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, 2014; 23: 161-183. 20140415. [CrossRef]

- Brooks RT, Beard J and Steel Z. Factor Structure and Interpretation of the K10. Psychol Assess, 006; 18: 62-70. [CrossRef]

- Andrews G and Slade, T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health, 2001; 25: 494-497. [CrossRef]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2003; 60: 184-189. [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Zamorski MA and Colman I. The psychometric properties of the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) in Canadian military personnel. PLoS ONE, 018; 13: e0196562-e0196562. [CrossRef]

- Elhai JD, Gray MJ, Kashdan TB; et al. Which instruments are most commonly used to assess traumatic event exposure and posttraumatic effects?: A survey of traumatic stress professionals. J Trauma Stress, 2005; 18: 541-545. [CrossRef]

- Fattori A, Comotti A, Mazzaracca S; et al. Long-Term Trajectory and Risk Factors of Healthcare Workers' Mental Health during COVID-19 Pandemic: A 24 Month Longitudinal Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2023; 20: 4586. [CrossRef]

- Zou, G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol, 2004; 159: 702-706. [CrossRef]

- StatCorp LLC. Stata/SE. 18.0 ed. College Station, TX2024.

- Government of Canada. Canadian occupational projection system (COPS), industrial summary, health care, https://occupations.esdc.gc.ca/sppc-cops/l.3bd.2t.1ils@-eng.jsp?lid=85 (2023, accessed 2024-08-30).

- Laurent A, Fournier A, Lheureux F; et al. Risk and protective factors for the possible development of post-traumatic stress disorder among intensive care professionals in France during the first peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. Eur J Psychotraumatol, 2022; 13: 2011603. 20220126. [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda F, Bergeron N, Dufour MM; et al. Longitudinal assessment and determinants of short-term and longer-term psychological distress in a sample of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Quebec, Canada. Front Psychiatry, 1112. [CrossRef]

- Roberts T, Daniels J, Hulme W; et al. Psychological distress and trauma in doctors providing frontline care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom and Ireland: A prospective longitudinal survey cohort study. BMJ Open, 2021; 11: e049680. 20210709. [CrossRef]

- Pestana D, Moura K, Moura C; et al. The impact of COVID-19 workload on psychological distress amongst Canadian intensive care unit healthcare workers during the 1st wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal cohort study. PLoS ONE, 2024; 19: e0290749. 20240307. 0290. [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: Lessons learned. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2004; 359: 1117-1125. [CrossRef]

- Moallef P, Lueke N, Gardner P; et al. Chronic PTSD and other psychological sequelae in a group of frontline healthcare workers who contracted and survived SARS. Can J Behav Sci, 2021; 53: 342-352. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).