1. Introduction

Several real-world problems can be mathematically modelled as an equation of the form

where

is a nonlinear operator mapping between the Banach spaces

X and

Y and

E is open convex set in

One of the most challenging problems appearing in real-world is to determine the solution

of (

1). Iterative methods are an alternate attractive technique to approximate solutions of nonlinear equations as obtaining the exact solution to these nonlinear equations becomes difficult. One of the most extensively used quadratically convergent iterative method is Newton’s method as it converges rapidly from any sufficiently good initial guess. Even though this method provides a good convergence rate, the need to compute and invert the derivative of the given operator function in each of the iterative step, limits the applicability of these method. To overcome this several Newton-like methods are available in the literature [

1,

3,

5,

13,

19]. One such successful attempt was made by Ren et al., in [

18] providing iterative method (see(

2)) of order six. Recall [

10] that a sequence

in

X with

is said to be convergent of order

, if there exist a nonzero constant

C such that

Previous studies primarily used Taylor expansion to determine the order of convergence(OC), which necessitates the existence of higher-order derivatives. An alternative method involves employing the computational order of convergence (COC) [

23], defined as:

where

are three consecutive iterates near root

or the approximate computational order of convergence (ACOC) defined as:

where

are four consecutive iterates near root

, to obtain the OC.

The limitation of COC and ACOC for iterative methods lies in their susceptibility to the oscillating behavior of approximations and slow convergence during early iterations [

17]. As a result, COC and ACOC do not accurately reflect the true OC.

In [

18], Ren et al., considered the following iterative scheme defined by

for solving (

1), when

In [

18], Taylor’s expansion is used to achieve a sixth-order convergence, but the analysis requires conditions on the derivatives of

up to the seventh order. These assumptions restrict the applicability of the method (

2) to problems involving operators that are differentiable at least seven times.

In this article, we initially determine the OC of the method (refer to [

9,

13]) defined for all

as follows:

where

X and

Y are Banach spaces. The local convergence of certain Jarratt-type methods was analyzed in [

2] by relying solely on assumptions about the derivative of order one of

. However, the OC was determined using COC and ACOC, which, as previously noted, are not ideal for calculating the convergence order. This raises the question: can we establish a third-order convergence for (

3) and a sixth-order convergence for (

2) without using assumptions on the higher-order derivatives of

or Taylor expansion?

Additionally, we enhance the method to a fifth-order approach, given as follows:

in

Section 4.

In

Section 2, we establish a third-order convergence for method (

3), and in

Section 3, we demonstrate a sixth-order convergence for (

2), relying on assumptions about the derivatives of

up to the second order. Consequently, our analysis broadens the applicability of methods (

3), (

2), and (

4) to problems that could not be addressed using the approaches in [

4,

14,

18,

20,

21].

In

Section 5, we examine the constraints of our approach and propose novel strategies to overcome these limitations for local as well as semi-local convergence scenarios. The convergence conditions are solely tied to the operators involved in the method for both the semi-local and local cases.

The remaining part of the paper includes the efficiency index in

Section 6, numerical demonstration in

Section 7, and basins of attraction in

Section 8, concluding with a summary in

Section 9.

2. Order of Convergence(OC) of (3):

The analysis of local convergence relies on the following assumptions:

- (A1)

&∃

such that

- (A2)

s

such that

- (A3)

- (A4)

Using the constants

and

, we define continuous nondecreasing functions (CNF)

as follows;

and

Given that

and

as

t tends to

, it follows that

has a smallest positive root in the interval

, which we denote by

. Define CNF

by

and

Since

and

as

, it follows that

has a smallest positive root in the interval

, which is denoted by

.

Let

Then, we have

Throughout the paper, we consider

and

, for

and

Theorem 1.

Assuming (A1)-(A4) are true, the sequence given by (3) with initial value converges to , and the following estimate is valid:

Proof. An inductive argument will be employed for the proof. As a first step, we will demonstrate that the operator

is invertible for all

belonging to the open ball

Note that, by (A1), we have

Therefore, by Banach lemma(BL)on invertible operators,

is invertible and by (

8), we have

Similarly, one can prove that

Next, by the method (

3), we have,

Note that,

For convenience, let

In order to prove (

7), we rearrange the equation (

11) as follows:

Let

and

Then, by (

13), we have

where,

and

Next, we estimate the norms of

and

Note that,

which is obtained using (A2) and (

10)(with

). Note that

and using (

10) we have,

Therefore,

and hence by (

9) (with

and

), we have

Therefore, on using (

17) in (

15) we get,

Next,

Therefore, by (

9), (

10), (A1) and (A3), we have

By using (

9) and (A2), we have

Thus, by (

16) and (

17), we have

Similarly, we have

So, by using (

16) and (

17), we have

Next, we shall obtain an estimate for

Observe that

Therefore, by (

9), (A1)-(A4), we have

Thus, from (

14)-(

24), we have

Therefore, the iterate

because

Simply replace

in the preceding arguments by

to complete the induction for (

7). □

Theorem 2. The method defined by (3) exhibits a convergence order of 3.

Proof. The proof follows a similar argument to that of Theorem 3 in [

6]. However, we include it here for completeness. Let

Let

q be maximal such that for some

Then, since

by (

5) (for large enough

n), we have

So, by (

25) and (

26), we get

Thus, by (

25), we get

Thus convergence order

□

3. Order of Convergence(OC) of (2):

This section examines the OC of method (

2). For our analysis we require some more CNF:

Let

defined by

and

Given that and and , we can conclude that the equation possesses a smallest positive solution within . This solution is denoted as

Let

be CNF defined by

and

Then,

and

as

Therefore

has a smallest positive solution in

denoted by

Let

Then, for all

Theorem 3.

Assuming (A1)-(A4) are true, the sequence given by (2) with initial value converges to , and the following estimate is valid:

Proof. Adopting the same proof strategy as in Theorem 1, we find that:

Note that by (

10) and (A1)

Now since

the iterate

□

Theorem 4. The method defined by (2) exhibits a convergence order of

Proof. Employing a proof strategy analogous to that of Theorem 2.

□

4. Order of Convergence(OC) of (4):

We analyze the OC of method (

4) in this section. We require some more CNFs as in previous sections:

Let

be CNFs defined by

and

Then,

and

as

Therefore

has a smallest positive solution in

denoted by

Let

Then, for all

Theorem 5.

Assuming (A1)-(A4) are true, the sequence given by (4) with initial value converges to , and the following estimate is valid:

Proof. In imitation of the proof presented for Theorem 1, we obtain:

Note that by (

10) and (A1)

Here, we used the inequality

Now since the iterate

□

Theorem 6. The method defined by (4) exhibits a convergence order of

Proof. Resembling the proof of Theorem 2.

□

The subsequent result addresses the uniqueness property of the solutions derived from the methods (

3), (

2), and (

4).

Theorem 7.

Suppose Assumption (A1) holds and the equation , has a simple solution . Then, for the equation the only solution in the set is provided that

Proof. Suppose is such that Define the operator Then by Assumption (A1) and (35), we have

So by BL, N is invertible and hence we get from the identity

5. Convergence Under Generalized Conditions

The applicability of method (

3) and the method (

4) can be extended. Notice that the second condition (A2) can can be violated easily even for simple scalar functions. Define the function

Since

and

is discontinuous at

, condition (A2) is violated in any neighborhood containing 0 and 1. This necessitates a convergence analysis based on generalized conditions and the operators inherent to the methods.

First the local convergence is considered under some conditions. Set

Presume:

- (H1)

Consider a CNF for which the smallest positive solution to is . Let be the interval .

- (H2)

Let

be the SPS of

, where the function

is given by

for some CNF

- (H3)

-

The equation

has a SPS denoted by

where

is given by

Let

- (H4)

The equation

has a SPS denoted by

where

is given by

where

- (H5)

-

The equation

has a SPS denoted by

here

is given by

Let

- (H6)

The equation

has a SPS denoted by

where

is given as

where

Let

The developed functions

and

relate to the operators on the method (

4).

- (H7)

-

There exist an invertible linear operator

L and

solving the equation

such that for each

Notice that under condition (H1) and (

36)

Thus is invertible. Let

- (H8)

-

for each

and

- (H9)

The main local analysis for the method (

4) follows in the next result.

Theorem 8.

Let the conditions (H1)-(H9) hold. Then, the following assertions are satisfied provided that

and where the functions are provided previously and the radius is defined by the formula (36).

Proof. Let

It follows that for each

and

The assertions (

37)-(

40) are shown by induction. Let

but be arbitrary. The condition (H1) and the formula (

36) give

Thus,

is invertible,

and the iterate

exists by the method (

4) if

Moreover, the first substep gives

Using (

36), (

44) (for

), (H8), (

45) and (

46)

Thus, the iterate

and the item (

38) holds if

The following estimate establishes the invertability of the linear operator

and iterate

by the second substep of the method (

4):

where we used the conditions (H3), (H7), formulas (

36), (

42) and (

37). Hence, by (

48)

Moreover, the second substep gives

It follows by (

36), (

44) (for

), (

45), (

47), (

49) and (

50)

Thus, the iterate

and for

the assertion (

39) holds. Next the invertability of the linear operator

establishes the existence of the iterate

as follows:

so

Then, the last substep of the method (

4) gives in turn

Using (

36), (H8), (

44) (for

), (

51), (

52) and (

53)

Hence, the iterate

and the assertion (

40) holds for

The induction is terminated if

replaces

in the preceding calculations. Finally, from the estimate

where

It follows

and the iterate

□

The isolation of the solution is discussed in the next result.

Proposition 1.

Suppose: there exists a solution for some the condition (H7) holds in the ball and there exists such that

Let

Then, the equation is uniquelly solvable by in the region

Proof. Define the linear operator

Then, by the condition (H7) in the ball

and (

56)

Hence,

follows from the identity

□

Remark 1.

-

(1)

A possible choice for In practice L shall be chosen to tighten the function Notice also that it does not necessarily follow from (H7) that is a simple solution or that is differentiable at

-

(2)

The results for the method (3) are obtained by restriction to the first two substep of the method (4).

A analogous approach is followed in the semi-local analysis but the role of is exchanged by and that of function and by and respectively which are developed below.

Suppose:

- (e1)

-

There exists CNF such that the equation has a SPS denoted by

Set

Let

be a CNF. Define the sequence

for

and each

by

and

- (e2)

-

There exists

such that for each

It follows that and there exists such that

The functions

and

are connected to the operators on the method (

4).

- (e3)

-

There exists

such that

Let Notice that (e1) and (e3) imply that the linear operator is invertible. Let

- (e4)

for each and

- (e5)

As in the local case we obtain in turn and induction the estimates

where

where

and

and

It follows by (

57)-(

65) that the sequence

is complete, since

is convergent by the condition (e2). But

X is a Banach space. Hence, there exists

such that

Then, by letting

in

we deduce that

Finally, notice that for

thus for

Hence, the semi-local result for the method (

4) is achieved.

Theorem 9.

Let that the conditions (e1)-(e5) hold. Then, there exists solving the equation Moreover, the following assertions hold

and

The uniqueness property of the solution is specified in the next result.

Proposition 2.

Suppose: There exists a solution of the equation for some the condition (e3) holds in the ball and there exists such that

Let Then, the only possible solution of the equation in the region is

Proof. Let

with

and the linear operator

It follows

Thus, we deduce

□

Remark 2.

-

(1)

A possible choice for

-

(2)

Suppose that the conditions (e1)-(e5) hold. Then, set and in Proposition 2.

-

(3)

Replace the limit point by in the condition (e5).

-

(4)

Clearly the results for the method (3) are obtained by simply restricting in the first two substeps of the method (4).

6. Efficiency Indices

There are several measures for comparing iterative methods other than OC, one of them is efficiency of the method. Recall the informational efficiency, introduced by Traub [

22] is given by

where

o is the order of the methods and

s is the number of function evaluations. Ostowski [

16], introduced a term before Traub called efficiency index or computational efficiency defined as

where

is the OC of the method and

is the number of function evaluations. Thus, the E.I and the C.E of the method (

2) are

and

the E. I and C. E of the method (

3) are

and

and E. I and C. E of the method (

4) are

and

7. Numerical Example

Example 1.

Consider , , Define function on E for by

Then, the first and second Fréchet derivatives are as follows:

and

Now, we can observe that Thus we get Thus,

Hence , and . With respect to and , we get .

Example 2.

Consider the non-linear integral equation of the Hammerstein-type given by

where H is any function such that

defined on , the space of all continuous functions on the on the interval let Then, we obtain first Fréchet derivatives as

we can observe that is a solution of Then, by applying the conditions we have and . With respect to and , we get and .

In the next example, we compare the iteration and the convergence order of methods (

3), (

2) and (

4) with that of following methods:

Noor Waseem-type methods [10]: given for

as

where

and

Newton Simpson-type methods [11]: given for

as

where

and

Example 3.

Let Consider the system of equations [12]

Observe, and are the solutions of the above system of equations. The approximation to the solution using the methods (67)-(72), (3), (2) and (4) starting with is given. The results are displayed in Table 1- Table 3.

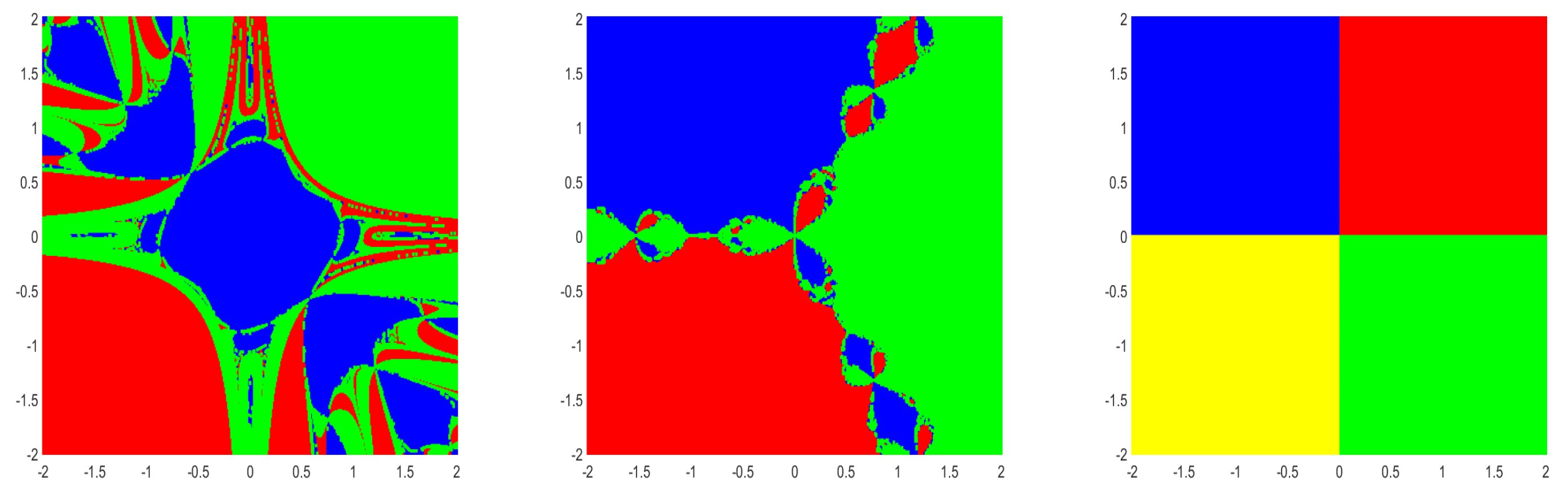

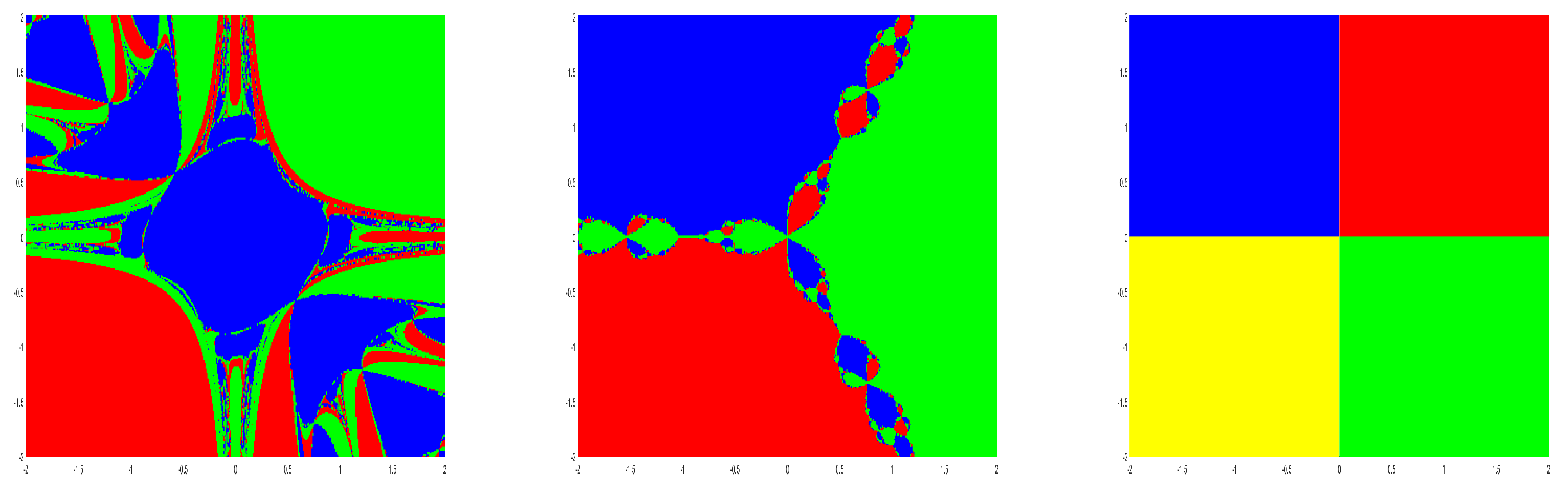

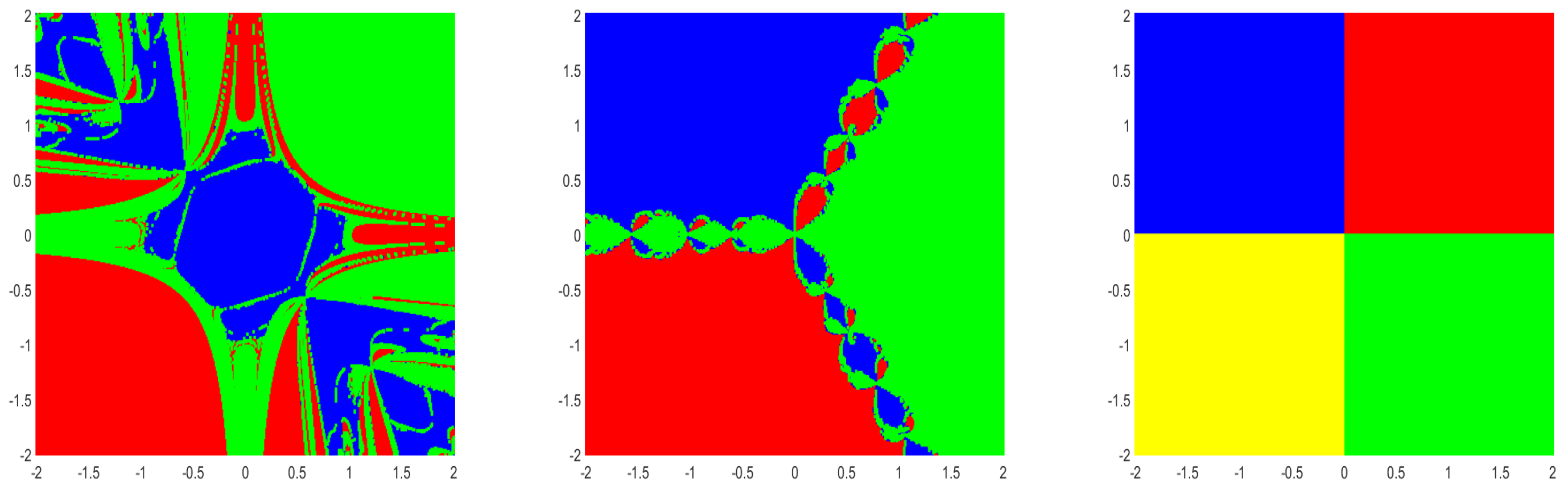

8. Basins of Attraction

For an iterative method, the set of all initial points which converges to a solution of an equation is known as Basins of attraction [

7,

8]. Using the approach of the basins of attractions we obtain the convergence area of the methods (

2), (

3) and (

4) when applied to the following examples;

Example 4. with solutions

Example 5.

with solutions

Example 6.

with solutions

Corresponding to the roots of system of nonlinear equations, the basins of attraction are generated in a rectangle domain with equidistant grid points of . According to root, each initial point is assigned a color, to which the corresponding iterative method converges, starting from . If either the method converges to infinity or it does not converge, then the point is marked black. In a maximum of 100 iterations a tolerance of is used.

Figure 1.

Dynamical plane of the method (

2) with Basins of attraction for Example 4(left), Example 5(middle) and Example 6(right).

Figure 1.

Dynamical plane of the method (

2) with Basins of attraction for Example 4(left), Example 5(middle) and Example 6(right).

Figure 2.

Dynamical plane of the method (

3) with Basins of attraction for Example 4(left), Example 5(middle) and Example 6(right).

Figure 2.

Dynamical plane of the method (

3) with Basins of attraction for Example 4(left), Example 5(middle) and Example 6(right).

Figure 3.

Dynamical plane of the method (

4) with Basins of attraction for Example 4(left), Example 5(middle) and Example 6(right).

Figure 3.

Dynamical plane of the method (

4) with Basins of attraction for Example 4(left), Example 5(middle) and Example 6(right).

9. Conclusion

We studied Jarrat-type method of convergence order three and its two extensions with convergence order six and five, respectively. As mentioned in the introduction, we used assumptions on

and

only, so these methods (

2), (

3) and (

4) can be used to solve problems which were not possible if we use the earlier convergence analysis using Taylor expansion. We discussed the limitations of our approach and developed new ways to overcome these limitations in

Section 5. Finally, we compare the methods with other similar methods using an example. Also using Basins of attraction approach the convergence areas of the methods (

2), (

3) and (

4) are given. In future research our ideas shall be applied on other methods to obtain similar benefits analogously [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]

References

- Argyros, I.K. The theory and applications of iteration methods. CRC Press, Engineering Series, Taylor and Francis Group 2022, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Argyros, I.K.; George, S. Extended Convergence Of Jarratt Type Methods. Appl. Math. E-Notes 2021, 21, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bartle, R. G . Newton’s method in Banach spaces. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1955, 6, 827–831. [Google Scholar]

- Behl, R.; Cordero, A.; Motsa, S.S.; Torregrosa, J. R. On developing fourth-order optimal families of methods for multiple roots and their dynamics. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2015, 265, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Israel, A. A Newton-Raphson method for the solution of systems of equations. Journal of Mathematical analysis and applications 1966, 15, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, E.; Castro, R.; Sierra, W. A Newton-type midpoint method with high efficiency index. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2020, 491, 124381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.; Lee, M.Y.B.; Neta, B.; Džunić, J. On optimal fourth-order iterative methods free from second derivative and their dynamics. Applied mathematics and computation 2012, 218, 6427–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.; Neta, B.; Chun, C. Basin attractors for various methods. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2011, 218, 2584–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, A.; Hueso, J.L.; Martínez, E.; Torregrosa, J.R. A modified Newton-Jarratt’s composition. Numer. Algor. 2010, 55, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Sadananda, R.; Jidesh, P.; Argyros, I.K. On the Order of Convergence of Noor-Waseem Method. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Kunnarath, A.; Sadananda, R.; Jidesh, P.; Argyros, I.K. Order of convergence, extensions of Newton-Simpson method for solving nonlinear equations and their dynamics. Fractal Fract 2023, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, A.; Iliev, I. Numerical method with order t for solving system nonlinear equations. Collection of scientific works 2000, 30, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jarratt, P. Some fourth order multipoint iterative methods for solving equations. Mathematics of Computation 1966, 20, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magreñán, A.A. Different anomalies in a Jarratt family of iterative root finding methods. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 233, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, J.M.; Rheinboldt, W.C. terative solution of nonlinear equations in several variables. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics 2000, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski, A.M. Solution of Equations and Systems of Equations: Pure and Applied Mathematics, A Series of Monographs and Textbooks. Elsevier 2016, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Petković, M.S.; Neta, B.; Petković, L.D.; Džunić, J. Multipoint methods for solving nonlinear equations: A survey. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2014, 226, 635–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wu, Q.; Bi, W. New variants of Jarratt’s method with sixth-order convergence. Numerical Algorithms 2099, 52, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheya, B.; Chen, G.Q.; Sui, Y.K.; Wu, C.Y. A new Newton-like method for solving nonlinear equations. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhno, S. M.; Iakymchuk, R. P.; Yarmola, H. P. Convergence analysis of a two step method for the nonlinear squares problem with decomposition of operator. J. Numer. Appl. Math. 2018, 128, 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhno, S. M.; Gnatyshyn, O. P. On an iterative algorithm of order 1.839. . . for solving nonlinear operator equations. Appl. Math. Appl. 2005, 161, 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Traub, J.F. Iterative methods for the solution of equations. American Mathematical Society 1982, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerakoon, S.; Fernando, T. A variant of Newton’s method with accelerated third-order convergence. Applied mathematics letters 2000, 8, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, W. Über ein Verfahren der Ordnung 1+2 zur Nullstellenbestimmung. Numerische Mathematik 1979, 32, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Methods of order 3.

Table 1.

Methods of order 3.

| k |

Noor Waseem Method (67) |

Ratio |

Newton Simpson method (70) |

Ratio |

Method(3) |

Ratio |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

| 1 |

(1.264067,-0.166747) |

0.052791 |

(1.263927,-0.166887) |

0.052792 |

(1.151437,0.051449) |

0.040459 |

| 2 |

(1.019624,0.265386) |

0.259247 |

(1.019452,0.265424) |

0.259156 |

(0.994771,0.304342) |

0.536597 |

| 3 |

(0.992854,0.306346) |

1.578713 |

(0.992853,0.306348) |

1.580144 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

1.951273 |

| 4 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

1.977941 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

1.977957 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

1.979028 |

| 5 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

1.979028 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

1.979028 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

1.979028 |

Table 2.

Methods of order 5.

Table 2.

Methods of order 5.

| k |

Noor Waseem Method (68) |

Ratio |

Newton Simpson method (71) |

Ratio |

Method(4) |

Ratio |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

| 1 |

(1.127204,0.054887) |

0.004363 |

(1.127146,0.054883) |

0.004363 |

(1.144528,0.069067) |

0.004375 |

| 2 |

(0.993331,0.305731) |

0.501551 |

(0.993328,0.305734) |

0.501670 |

(0.994305,0.304922) |

0.495553 |

| 3 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

3.889725 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

3.889832 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

3.847630 |

| 4 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

3.916553 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

3.916553 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

3.916553 |

Table 3.

Methods of order 6.

Table 3.

Methods of order 6.

| k |

Noor Waseem Method (69) |

Ratio |

Newton Simpson method (72) |

Ratio |

Method(2) |

Ratio |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

(2.000000,-1.000000) |

|

| 1 |

(1.067979,0.174843) |

0.001211 |

(1.067906,0.174885) |

0.001211 |

(1.027012,0.256566) |

0.001057 |

| 2 |

(0.992784,0.306436) |

1.383068 |

(0.992784,0.306436) |

1.384152 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

3.122403 |

| 3 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

5.509412 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

5.509414 |

(0.992780,0.306440) |

5.509727 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).