1. Introduction

With an estimated 60 million people affected globally and a steadily rising prevalence, atrial fibrillation (AF) is unquestionably a 21st-century pandemic. As AF is associated with an increased risk of systemic thromboembolism and reduced quality of life, it represents a significant burden to healthcare systems around the world [

1]. Cardioversion (CV) often represents the initial strategy for rhythm control of newly diagnosed AF or patients with symptomatic AF [

2]. Following sinus rhythm restoration, an increased risk of thromboembolic complications (TECs) is often observed, potentially leading to severe disability or death [

3,

4,

5]. The practice of managing patients with acute AF who are at low objective risk of stroke differs substantially. Considering risk assessment, subjects without any risk factors for thromboembolism (i.e. CHA

2DS

2-VA=0 [C: Congestive heart failure; H: Hypertension; A

2: Age 75 or older (2 points); D: Diabetes mellitus; S

2: Stroke or transient ischemic attack (2 points); V: Vascular disease; A: Age 65 to 74]) are felt to be at low risk of peri-cardioversion TEC if their AF episode duration is < 12 hours (American, Canadian and Chinese guidelines indications [

6,

7,

8]), < 24 hours (ESC 2024 recommendations [

9]), or < 48 hours (according to the British and Australian & New Zealand guidelines on AF [

10,

11]). While the Canadian and Chinese guidelines recommend short-term oral anticoagulation (OAC) for 4 weeks in all patients after CV (regardless of arrhythmia duration or risk factors for TECs), the European, US, Australian & New Zealand and UK (NICE) guidelines state that postprocedural anticoagulation is discretionary. Considering the significant variation in international recommendations about the clinical management of these low-risk, acutely cardioverted AF patients, this study sought to evaluate real-world practice patterns through an international survey of physicians.

2. Materials and Methods

Survey creation: Initially, PubMed/MEDLINE and Embase databases were consulted to identify the most recent guidelines on AF via the following research string: “atrial fibrillation AND guidelines”. The following results, in English, dating from 2018 onwards were included for review: ESC 2024 Europe) [

9], China 2024 [

8], USA 2023[

6], UK (NICE) 2021 [

10], CCS 2020 (Canada) [

7] and Australia & New Zealand 2018 [

11] (see Table A, Supplementary Materials).A cross-sectional survey was designed at

Università degli Studi di Torino based on review of the evidence presented in the selected guidelines. A standardized clinical case describing a 64-years old male undergoing electrical CV for his AF discovered within the previous 12 hours, without any other comorbidities and not taking any medications on a regular basis introduced the questionnaire and represented the starting point of the survey, onto which all questions were based. Together with initial questions exploring the demographics of the participants, the survey’s questions specifically investigated the clinical management of acutely cardioverted, low-risk AF patients (see Supplementary Materials).

Survey administration: The survey was distributed in collaboration with UBC – Division of Cardiology and IRCCS Ospedale San Raffaele. We surveyed physicians from 17 centres across 5 countries (Canada, Italy, France, Germany and USA) on 2 continents (Supplementary Materials). The survey was completed between March 2024 and October 2024. The physicians involved in this investigation had different expertise levels and belonged to healthcare systems following different guidelines. Participants were recruited with a fellow approach, based on which the more experienced authors involved refrained from sharing the questionnaire through official channels with their colleagues, in order to truly understand real-world therapeutic choices and to avoid the risk of methodologically influencing responses. Two countries (USA and Germany) were inadvertently involved in the study as the survey link was shared by participants with fellows from these countries with an interest in this topic. The requirement to participate in the survey was acceptance to the website privacy policy (see Supplementary Materials; Google Forms Policies and Guidelines). Since all data were completely anonymous and did not involve patients, but physicians on a voluntary basis (not recruited), Ethics Committee approval was not required. Continuous variables are reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables are reported as the number of cases and percentage. Categorical variables were compared by contingency tables and Chi-square (X2) and Fisher’s exact tests were employed to study the strength of associations. All tests of significance were two-tailed, and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant within a 95% CI. Analysis was performed using Jamovi Desktop (version 2.6.24).

3. Results

Seventy-six physicians answered the questionnaire. Cardiologists accounted for the greater part of respondents (60, 78.9%), followed by internists and intensivists (8, 10.5% and 5, 6.5%, respectively). Two respondents (2.6%) were specializing in geriatrics and only 1 (1.3%) in emergency medicine. The majority of clinicians (48, 63.2%) who replied to the question “Would you start this patient on short-term OAC with DOACs?”, selected the option indicating short-term (4 weeks) OAC prescription following acute CV to all patients, regardless of CHA2DS2-VA score or AF duration. Six physicians (7.9%) would anticoagulate patients only starting from CHA2DS2-VA ≥ 1, while 11 participants (14.5%) affirmed they would possibly administer short-term OAC upon discussion with their patient (shared decision-making strategy) and further diagnostic workup. Another 11 practitioners (14.5%) decided not to prescribe any short-term OAC treatment, believing that the patients’ haemorrhagic risk in the study population would outweigh the thromboembolic one. Starting temporary anticoagulation only in patients with a CHA2DS2-VA ≥ 1 was the least chosen approach. Respondents’ replies stratified by specialty and work experience (expressed as years of career duration) are summarized in Table S2, S3 and S4 in the Supplementary Materials section. Although cardiologists mostly opted for proactive anticoagulation (cardiologists vs other specialties, Fisher’s and X2 tests p= 0.029, see Table S5, Supplementary Materials), they also represented the category that would most likely avoid OAC prescription in low-risk patients after sinus rhythm restoration, with 9 of them (15% of all cardiologists) considering post-CV OAC overtreatment.

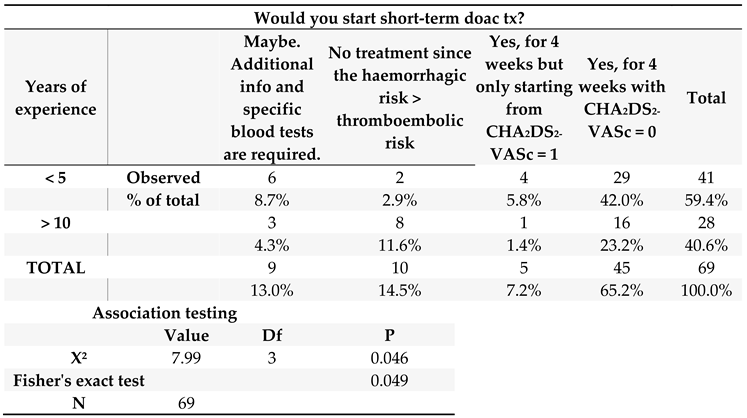

3.1. Stratification by Work Experience

When considering expertise level, only 12 out of 41 participants (29.3%) with a professional experience below 5 years would not directly start their patients on OAC after acute CV. For the “no treatment” category, physicians with an expertise of at least 10 years were the most likely not to prescribe short-term OAC, while among those with an experience >20 years opinions were also divided, with three cardiologists (from AP-HP, Milan and Turin) who would not prescribe any short-term OAC after CV to limit haemorrhagic complications and five other cardiologists (1 from Turin and 4 from UBC) who would surely start any acutely cardioverted patient on anticoagulant therapy (see Table S3 and S4, Supplementary Materials). Overall, younger physicians with experience below 5 years (29/41 or 70.7%) would prescribe short-term OAC more frequently compared to those with an experience of ≥ 10 years (16/28 or 57.1%, grouping together both those with more than 10 and more than 20 years of medical training). This latter association was further confirmed statistically by Fisher’s exact test (p= 0.049, see

Table 1).

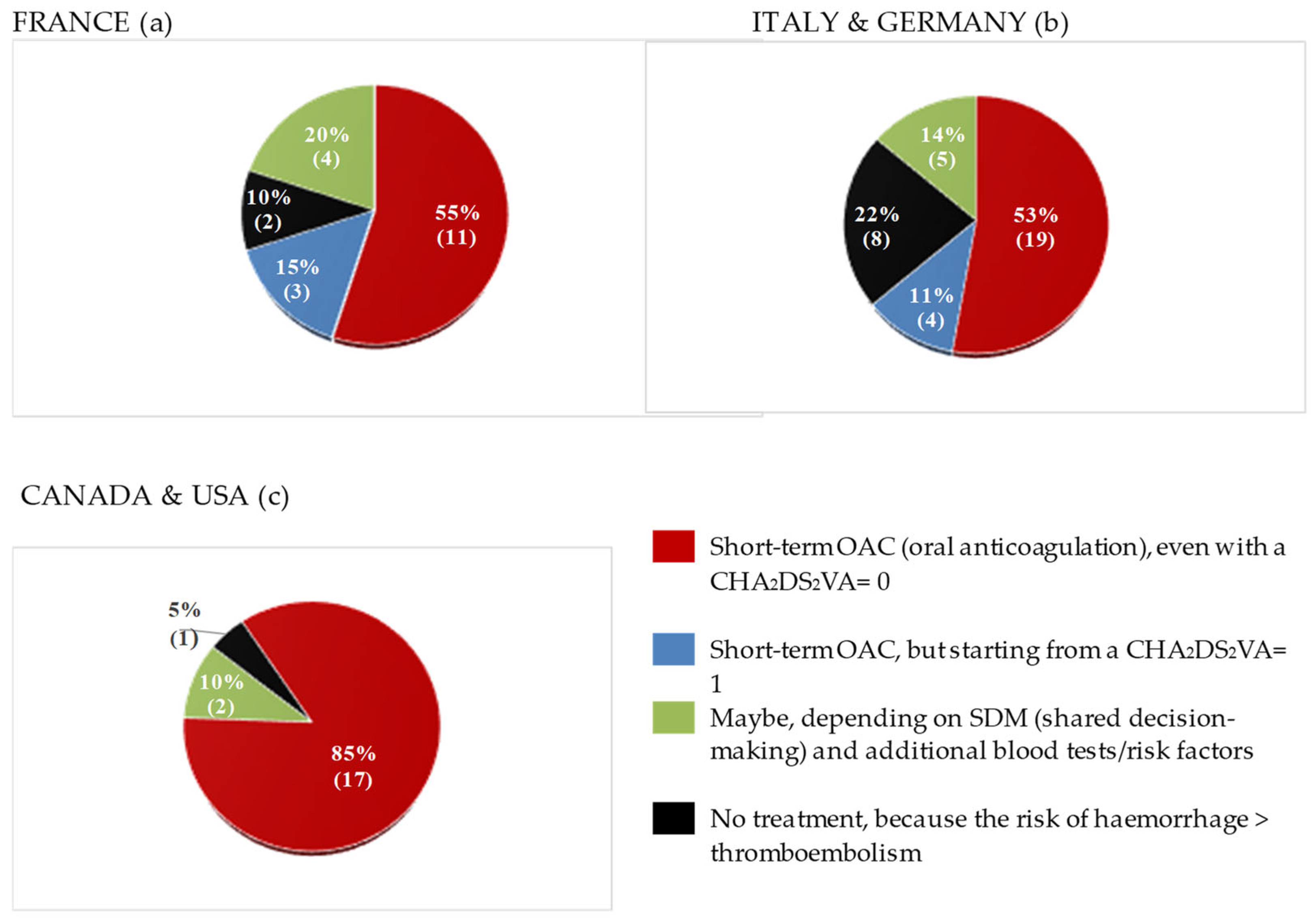

3.2. Stratification by Healthcare System

When comparing responses from geographically distinct healthcare systems, it could be observed that around 50% of European physicians replied they would start their patients on short-term OAC in the specific setting illustrated in the questionnaire, while the other half either would not administer any OAC or they would start it from CHA

2DS

2-VASc ≥ 1 (see

Figure 1). In greater detail, a considerable proportion of French (4, 20% among all French physicians) and of Italian physicians (5, 14% of all Italians, including 1 German respondent) would choose a shared decision-making approach. When performing X

2 and Fisher’s tests to evaluate for the strength of the association between healthcare system or nationality and propensity to prescribe short-term OAC, no statistically significant relationship was found (p= 0.120, see Supplementary Materials, Table S6). However, a “centre-specific” effect was observed in two cases: 1. OAC was the least offered after CV in Turin, compared to all other centres; 2. All practitioners working in Bordeaux uniformly selected the option “Short-term OAC for four weeks for all patients, even with CHA

2DS

2-VASc score= 0”, while responses from Parisian hospitals were much more heterogeneous (

Figure 2 and Table S4, Supplements).

A question which elicited particular heterogeneity among respondents was whether to administer VKA (Vitamin K Antagonists)-based OAC to patients with the same risk profile as the patient illustrated in the survey’s clinical case, but presenting with valvular AF. In detail, 20% (4) of French respondents, 27.8% (10) of Italian physicians and 9.5% (2) of Canadians stated they would not initiate short-term VKA-based OAC in an acutely cardioverted, valvular AF patient. Other notable international differences appeared in the use of imaging techniques for low-risk patients prior to CV and in rhythm monitoring strategies after successful restoration of sinus rhythm. While 81.8% (27) of Italian and German participants indicated they would perform transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) before CV, 85.7% (6) of Canadian respondents stated they would not, with Fisher’s testing revealing a statistically significant association between participants’ nationality and TTE before CV (Europe vs Canada, p= < 0.001, see Table S7, Supplementary Materials). As far as preprocedural transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) is concerned, opinions were more homogeneous, with only 25% (5) of French, 16.7% (6) of Italian and German and 9.5% (2) of North American practitioners affirming they would always perform it prior to acute CV, regardless of arrhythmia duration and patients’ risk factors for TECs. Also in this case, a statistically significant association between healthcare systems following specific guidelines and peri-CV TOE emerged (Europe vs Canada, p= 0.006, see Table S7, Supplementary Materials). In Canada the preferred rhythm monitoring strategy after successful cardioversion was a 24h or 7-day ECG Holter performed at regular intervals before follow-up visits (option selected by 40% of physicians), while Italian participants were more likely to recommend that their patients purchase a smartwatch capable of recording a 1-lead ECG (45.7% or 16 doctors). In France, discontinuous rhythm monitoring, recording single ECGs at follow-up visits was the most popular approach (46.7%, 7 respondents).

Finally, European and Canadian physicians expressed partially different thoughts regarding long-term rhythm control strategies. About 45% (15) of Italian physicians declared they would offer AF catheter ablation by means of pulmonary veins isolation (PVI) as a first-line treatment after sinus rhythm restoration in young and low-risk individuals, while 51.5% (17) of them would propose it to their patients in case of AF recurrence and reduced quality of life. Although only 7 Canadians replied to this question, 85.7% (6) of them would offer it in case of relapsing arrhythmia, and 14.3% (1) would not consider it necessary in this specific case, thus proving how first-line PVI is offered more frequently by European cardiologists (Europe vs Canada, p= 0.013; see Table S8, Supplementary Materials).

4. Discussion

4.1. Evidence Regarding Peri-Cardioversion OAC

Short-term OAC therapy during the 4 weeks that follow cardioversion is strongly recommended only in two countries: Canada and China [

7,

8]. Conversely, contrasting indications are reported in other guidelines (see Table S1, Supplementary Materials). Overall, recommendations contained in official guidelines are weak in terms of both benefit to the patient and effectiveness and/or are based on low-quality evidence (class IIb or

Weak Recommendation; Low-Quality Evidence). This is because all existing evidence derives from observational studies, with the most relevant and recent being the Finnish CardioVersion (FinCV) study series [

3,

12,

13], the Cleveland Clinic study [

14], a study from the Danish National Patient Registry [

15] and a study from the Emergency Department (ED) at Parma University Hospital [

2]. The only prospective observational research is by Tampieri et al. [

16], which is, however, based on a small sample size (218 cardioversions). Unfortunately, all these studies provide limited data on haemorrhage incidence [

3,

14], making it challenging to estimate short-term OAC-related haemorrhagic outcomes in these low-risk patients. Nonetheless, these studies report that the majority of cardioembolic strokes and other TECs primarily occurred within the first 30 days following acute cardioversion [

3,

17], their incidence was limited (0% to 0.4%) and lowest when the time to CV was <12 hours (0.2%) [

12]. In part, the uncertainty surrounding a definite indication for postprocedural short-term OAC might be related to the complex pathophysiology leading to an increased risk of TECs in the post-CV weeks. More in detail, four main processes have been identified that could explain such a phenomenon:

- I.

Atrial stunning, a temporary depression in left atrial appendage (LAA) mechanical function, resulting in decreased LAA emptying velocities, potentially favouring intracardiac thrombus formation [

18]. The intensity of this phenomenon is strictly dependent on previous arrhythmia duration and can occur both after electrical and pharmacological CV [

19].

- II.

An inaccurate estimation of the real onset of AF. Up to 4–8% of patients whose AF lasts for just 6 to 48 hours are completely asymptomatic [

20]. Thus, these individuals might be mistakenly cardioverted well beyond 48 hours from their real AF onset. This is clinically relevant, because longer AF episodes (even if asymptomatic) lead to more profound atrial stunning and a higher probability of post-CV thrombus formation [

20].

- III.

Transient prothrombotic state associated with sinus rhythm restoration. Even in case of AF lasting < 48 hours, the increased atrial volume and pressures in AF patients lead to stretching of the atrial cavities and to endothelial dysfunction, further promoting blood stasis and thrombin synthesis [

21], both of which are risk factors for intracardiac thrombus formation.

- IV.

Pre-formed thrombus within the left atrial appendage (LAA) or left atrium (LA). Although it has been demonstrated that intra-atrial thrombi can already form in patients whose atrial fibrillation has lasted for less than 48 hours [

22] , Anselmino et al. [

23] detected no intracardiac thrombi in patients in sinus rhythm, with CHA

2DS

2-VASc = 0-1 and with no past history of AF ablation undergoing TOE before AF pulmonary vein isolation (PVI), making this hypothesis unlikely in the study population described in this research. Moreover, the absence of echocardiographic evidence of LAA thrombus is not an indication for safe CV without postprocedural OAC and does not prevent TECs from occurring once sinus rhythm is restored [

3].

Importantly, no statistically significant reduction in the rate of thromboembolic complications has been proven upon administration of short-term OAC following acute CV in low-risk patients [

13,

14], potentially making OAC a form of overtreatment in this specific scenario [

16]. However, as pointed out by Andrade et al., the absence of statistical significance for OAC in reducing TECs in the post-CV period in this population is likely a consequence of insufficient power for subgroup analysis [

24]. Still, two elements exist that could favour postprocedural short-term OAC for this category of AF subjects: uncertainty about precise AF duration and patient’s individuality and personal preferences. Indeed, asymptomatic paroxysmal AF patients could be at greater risk of being cardioverted well beyond the 12–48-hour window from the onset of atrial fibrillation [

20] and without OAC they might show a higher embolic stroke following CV, potentially resulting in devastating consequences in these otherwise healthy patients. Furthermore, as the 30-day rate of thromboembolic events after acute CV (even if this latter is performed < 12 hours from the beginning of AF) is of about 0.2% [

12], such an incidence is considered well above the monthly 0.12% (or 1.5% annual) cut-off threshold for embolic events employed by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) to justify antithrombotic treatment, therefore making OAC mandatory in this specific scenario, according to the CCS 2020 AF guidelines. Nonetheless, as the incidence of bleeding is highest during the initial 30 days of OAC initiation [

25], the ESC, AHA, Australian and NICE (UK) indications recommend a more cautious and individualized assessment of the risks and benefits of this treatment in young patients (< 65 years old) with no other comorbidities that can predispose to TECs. Notably, Saglietto et al. estimated that in a low-risk population (CHA

2DS

2-VASc = 0 and HAS-BLED 0-1), the 30-day incidence of clinically significant bleeding following 4 weeks of OAC therapy after acute CV would be approximately 0.46%, with a projected 0.08% risk of fatal intracranial haemorrhage (ICH), compared to a 0.2% risk of TECs if no OAC is prescribed [

26]. A final point to consider is that AF guidelines are also adopted by emergency room (ER) physicians who can both perform CV and prescribe short-term oral antithrombotic therapy. Hence, a uniformly adopted approach that leaves little room for individualized care or reliance on precise timing of AF onset may be easier to implement in the hectic ER setting. In summary, as the Canadian guidelines wisely point out: “

The relative importance of a stroke prevented, and major bleed caused is a subjective judgement” [

7].

4.2. Study Results

The most striking finding of this study is that participants, both at the national and international level, provided varying responses on several aspects of the management of a simple, common clinical scenario, including imaging techniques before CV, timing and type of rhythm monitoring, post-CV anticoagulation and first-line AF catheter ablation for long-term rhythm control. As this investigation showed, some physicians may occasionally prefer individualized strategies according to their own professional knowledge and personal experience, which apparently go against guidelines, although these latter represent the standard of care, mirroring different local priorities and health needs and being designed on solid evidence. For instance, 15% (3) of Canadian respondents chose not to administer short-term OAC, while Canadian guidelines strongly recommend it to all patients after CV. Conversely, the fact that physicians with an experience < 5 years appeared to prescribe OAC more frequently after CV compared to their older colleagues may possibly stem from two factors. On one hand, younger physicians might be more familiar with the latest guidelines and tend to prioritize a minimize stroke risk approach, which is now a core principle emphasized in all AF guidelines. On the other hand, the more experienced physicians in this study appeared to prefer a case-by-case strategy, carefully selecting patients who would benefit most from short-term OAC based on their professional judgment, while also aiming to minimize haemorrhagic risk in these individuals.

4.3. Future Implications

Overall, the degree of diversity in participants’ responses reflects the need to further refine the specific recommendations contained in guidelines on short-term OAC after acute CV, so to better orient and support physicians’ choices. Given the above results, we propose three distinct strategies which might be considered in the development of future recommendations, so to better take care of these low-risk, acutely cardioverted AF patients:

1)

The cutoff threshold to perform a safe acute cardioversion without post-procedural OAC should ideally be reduced to less than 12 hours, as already indicated in the American [

6] AF guidelines. The rationale for this suggestion derives from the FinCV studies [

12], illustrating how only patients with CHA

2DS

2-VA= 0 and cardioverted within less than 12 hours from AF onset truly carry a neglectable post-CV risk of thromboembolic complications (i.e. 0.2% within the first month that follows CV). This 12-hour limit is further supported by Sohara et al. [

27] who showed that the transient prothrombotic state associated with AF becomes more intense with arrhythmia duration greater than 12 hours, facilitating intracardiac thrombus formation.

2)

Regional differences in access to DOACs and local or individual stroke risk profile should always be considered. DOACs are to be preferred for short-term OAC after acute CV of patients with nonvalvular AF, due to their lower propensity to cause intracranial haemorrhage (ICH), compared to Warfarin. Furthermore, as the American and the Australian & New Zealand guidelines for AF management specifically mention, inequalities in access to DOACs and discriminations regarding anticoagulation should always be considered. For instance, among Oceanian Aboriginals with AF, the risk of stroke (of all types) is 3 times higher than in the general population, particularly among younger individuals [

11]. Such populations also often reside in geographically isolated areas in which frequent INR monitoring for Warfarin therapy is impractical and DOACs are only accessible through out-of-pocket insurance, representing a relevant barrier to their use [

11]. American guidelines are the only to mention insurance coverage when selecting the optimal OAC treatment option for patients with AF. However, these latter recommendations also state that all patients should be equitably prescribed guideline-directed OAC, regardless of adverse social determinants of health, so as to minimize discrimination within the US healthcare system [

6]. It is also important to think of medications which can interact with the metabolism of OAC (e.g. ritonavir or other CYP inhibitors that might increase to dangerous levels plasmatic concentrations of DOACs) [

28] and any other modifiable risk factors for TECs or bleeding not already part of CHA

2DS

2-VA or HAS-BLED.

3)

Extra preventive measures to limit the risk of clinically significant haemorrhage and ICH should be actively implemented in those healthcare systems where short-term OAC is systematically administered to all patients after CV (e.g. Canada and China). In fact, while the CCS 2020 AF guidelines provide clear instructions on oral anticoagulation after CV, they do not mention how to actively instruct patients to minimize their risk of severe bleeding, potentially associated with short-term OAC. More precisely, acutely cardioverted, low-risk AF patients are mostly composed of relatively young (< 65 years of age), active and otherwise healthy individuals, a population somewhat similar to that of individuals undergoing oral anticoagulation in the setting of venous thoracic outlet syndrome or athletes receiving OAC after pulmonary embolism. As it is recommended in these latter populations [

29,

30], while on OAC (i.e. for 4 weeks in the case of low-risk AF patients), any form of contact sports and risky behaviours or hobbies should be categorically avoided. In addition, cardioverted patients and their families should be educated on how to recognize early signs of severe bleeding and what to do in case such an event occurs.

5. Limitations

Although this study represents the first specifically assessing real-word choices of physicians in the setting of acute cardioversion of low-risk AF patients, it presents significant limitations. Firstly, the study sample size was small (76 participants), making it impossible to draw any conclusive message on the subject. Secondly, not enough ED physicians have been involved, while most replies were submitted by cardiologists, potentially skewing results in favour of anticoagulation and not precisely describing therapeutic tendencies in emergency departments.

6. Conclusions

This investigation shows how in low-risk, acutely cardioverted AF patients, choosing between and balancing the benefits of short-term OAC against no antithrombotic therapy might often be problematic. Reducing time limit to safely not prescribe OAC to < 12 hours, while caring for local access to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and regional or individual stroke risk profile and actively preventing haemorrhage in patients receiving short-term OAC could represent effective measures, implementable in future guidelines, to limit CV-related complications and improve outcomes in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and M.A.; methodology, M.A.; software, A.P.; validation, A.P.S., L.R. and J.G.A.; formal analysis, J.G.A. and M.A.; investigation, A.P.; resources, A.P.; data curation, A.P., M.A., A.P.S. and L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P..; writing—review and editing, M.A:, J.G.A., A.P.S., L.R.; supervision, M.A. and J.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting reported results can be found in the Supplementary Materials section.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all physicians who took part in this survey for their time and commitment to improve the care of AF patients. We would also like to warmly thank Dr Christopher Fordyce and Dr Paolo Emilio Della Bella for their support in carrying out this investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| CV |

Cardioversion |

| OAC |

Oral Anticoagulation |

| TECs |

Thromboembolic complications |

References

- Linz D., Gawalko M., Betz K. et al., ‘Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, screening and digital health’, Lancet Reg. Health - Eur., vol. 37, p. 100786, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti L. Annovi A., Sanchis-Gomar F. et al., ‘Effectiveness and safety of electrical cardioversion for acute-onset atrial fibrillation in the emergency department: a real-world 10-year single center experience’, Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 64–69, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Airaksinen K. E. J., Grönberg T., Nuotio I. et al., ‘Thromboembolic Complications After Cardioversion of Acute Atrial Fibrillation’, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., vol. 62, no. 13, pp. 1187–1192, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Scheuermeyer F.X., Grafstein E., Stenstrom R. et al. ‘Thirty-day Outcomes of Emergency Department Patients Undergoing Electrical Cardioversion for Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter’, Acad. Emerg. Med., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 408–415, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Palomäki A., Mustonen P., Hartikainen J.E.K. et al., ‘Strokes after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation — The FibStroke study’, Int. J. Cardiol., vol. 203, pp. 269–273, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Joglar et al., ‘2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines’, Circulation, vol. 149, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Andrade et al., ‘The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation’, Can. J. Cardiol., vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 1847–1948, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ma C.-S. et al.,‘Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation’, J. Geriatr. Cardiol., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 251–314, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Van Gelder et al., ‘2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)’, Eur. Heart J., vol. 45, no. 36, pp. 3314–3414, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘Recommendations | Atrial fibrillation: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE’. Accessed: Dec. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng196/chapter/Recommendations.

- D. Brieger et al., ‘National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation 2018’, Heart Lung Circ., vol. 27, no. 10, pp. 1209–1266, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Nuotio I., Hartikainen J. E. K., Grönberg T. et al., ‘Time to Cardioversion for Acute Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolic Complications’, JAMA, vol. 312, no. 6, p. 647, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Grönberg T., Hartikainen J. E. K., Nuotio I. et al.Gronberg T et al., ‘Anticoagulation, CHA2DS2VASc Score, and Thromboembolic Risk of Cardioversion of Acute Atrial Fibrillation (from the FinCV Study)’, Am. J. Cardiol., vol. 117, no. 8, pp. 1294–1298, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Garg A., Khunger M., Seicean S. et al., ‘Incidence of Thromboembolic Complications Within 30 Days of Electrical Cardioversion Performed Within 48 Hours of Atrial Fibrillation Onset’, JACC Clin. Electrophysiol., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 487–494, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hansen M. L., H. G. Jepsen R.M., Olesen J. B. et al., ‘Thromboembolic risk in 16 274 atrial fibrillation patients undergoing direct current cardioversion with and without oral anticoagulant therapy’, EP Eur., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 18–23, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tampieri A., Cipriano V., Mucci F. et al., ‘Safety of cardioversion in atrial fibrillation lasting less than 48 h without post-procedural anticoagulation in patients at low cardioembolic risk’, Intern. Emerg. Med., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 87–93, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Dagres N., Kornej J. and Hindricks G., ‘Prevention of Thromboembolism After Cardioversion of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation’, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., vol. 62, no. 13, pp. 1193–1194, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Grimm R. A., Stewart W.J., Maloney J.D. et al., ‘Impact of electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation on left atrial appendage function and spontaneous echo contrast: characterization by simultaneous transesophageal echocardiography’, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 1359–1366, Nov. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Khan I. A., ‘Atrial stunning: basics and clinical considerations’, Int. J. Cardiol., vol. 92, no. 2–3, pp. 113–128, Dec. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Flaker G. C., Belew K., Beckman K.et al., ‘Asymptomatic atrial fibrillation: demographic features and prognostic information from the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study’, Am. Heart J., vol. 149, no. 4, pp. 657–663, Apr. 2005. [CrossRef]

- ‘Prothrombotic markers in atrial fibrillation: what is new? - PubMed’. Accessed: Jan. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11511115/.

- Stoddard M. F., Dawkins P. R., Prince C. R. et al., ‘Left atrial appendage thrombus is not uncommon in patients with acute atrial fibrillation and a recent embolic event: a transesophageal echocardiographic study’, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 452–459, Feb. 1995. [CrossRef]

- Anselmino M., Garberoglio L., Gili S. et al., ‘Left atrial appendage thrombi relate to easily accessible clinical parameters in patients undergoing atrial fibrillation transcatheter ablation: A multicenter study’, Int. J. Cardiol., vol. 241, pp. 218–222, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Andrade J. G., Macle L., Verma A. et al., ‘Comment on “The Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2018 guideline update for atrial fibrillation – A different perspective”’, CJEM, vol. 22, no. 3, p. E3, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lamberts M., Staerk L., Olesen J. B. et al., ‘Major Bleeding Complications and Persistence With Oral Anticoagulation in Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: Contemporary Findings in Real-Life Danish Patients’, J. Am. Heart Assoc., vol. 6, no. 2, p. e004517, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Saglietto A., De Ferrari G. M., Gaita F. et al., ‘Short-term anticoagulation after acute cardioversion of early-onset atrial fibrillation’, Eur. J. Clin. Invest., vol. 50, no. 11, p. e13316, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sohara H., Amitani S., Kurose M. et al,, ‘Atrial fibrillation activates platelets and coagulation in a time-dependent manner: a study in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation’, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 106–112, Jan. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Tamemoto Y., Shibata Y., Hashimoto N. et al., ‘Involvement of multiple cytochrome P450 isoenzymes in drug interactions between ritonavir and direct oral anticoagulants’, Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet., vol. 53, p. 100498, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- ‘Athletes and Anticoagulation: Return to Play After DVT/PE’, American College of Cardiology. Accessed: Feb. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2016/10/19/15/13/http%3a%2f%2fwww.acc.org%2flatest-in-cardiology%2farticles%2f2016%2f10%2f19%2f15%2f13%2fathletes-and-anticoagulation.

- Weiske N., Baumbach H., and Bürger T., ‘Treatment of venous thoracic inlet syndrome – Specialties in athletes’, Phlebologie, vol. 49, no. 01, pp. 10–15, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).