1. Introduction

During the 2017 measles epidemic, Lazio was the most affected region in Italy, with an incidence rate of 32.8 cases/100,000 inhabitants, 1,982 cases. Among these, 129 (6.5%) were healthcare workers (HCW), representing 38.6% of national cases in the professional category: 90.9% were not vaccinated, and 53.5% presented at least one complication [

1]. Following the epidemic, vaccination programs were encouraged by the Region [

2,

3,

4], and the initiatives were widespread: hospitals and other healthcare facilities actively offered screening and vaccination with two doses, one month apart, against measles, mumps and rubella (MMR).

Regarding Measles virus (MeV) genotype, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Italian national measles and rubella surveillance system identified the co-circulation of the genotypes B3 and D8 [

5].

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, a sharp decline of measles was observed in the Lazio region in 2020, with 11 cases, and in 2021 no cases were identified. In 2022, only one isolated case was detected in May, the origin of which could not be identified: IgM were confirmed but no sample was available for genotyping. The patient remained at home, and did not cause secondary cases. In October two subsequent cases were observed, one of which was a HCW working in the emergency department (ED) where the first case had been admitted. An epidemiological and molecular investigation was carried out to confirm transmission despite COVID-19 precautions.

Description of cases

In October 2022, a person in their thirties, confused and dehydrated, was admitted to an ED in Rome due to high fever and skin rashes. COVID-19 precautions were in place, so HCW wore respiratory protection (FFP2) and full personal protective equipment (PPE); an FFP2 mask was provided to the patient upon entry. Triage occurred in a single room, and isolation precautions were implemented. Measles was readily suspected, as the patient was not vaccinated, and serology was performed shortly after admission, showing positive IgM with negative IgG. The patient acknowledged contact with a probable case in another region, which was traced and eventually confirmed. After approximately 12 hours, the patient was transferred to the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “L. Spallanzani” - IRCCS (INMI), where also the Regional Reference Laboratory (RRL) for Measles and Rubella Surveillance is located, with airborne precautions, and placed in a negative pressure room. Measles was confirmed by the INMI RRL: RT-PCR was positive in whole blood and urine samples. The patient recovered after one week and was discharged without any complications.

Seventeen days later, an emergency physician working in the same hospital presented to the same emergency room reporting a 6-day high fever, resistant to antipyretics, and was immediately isolated in a single room with an FFP2 mask. During examination, a maculopapular rash was observed, along with hyperemic pharyngitis, and scarlet fever was suspected. Several serologies were performed and measles IgM was positive with negative IgG; the doctor reported no vaccination. Samples were sent to the INMI RRL and measles was confirmed; serology showed higher IgM titer and negative IgG, and urine RT-PCR was positive.

No cases of measles were identified following epidemiological investigation and active surveillance among the doctor’s contacts and residents in the area. ED admissions in the last 21 days prior to the onset of symptoms of the second case were reviewed and, apart from the first confirmed case, no further suspected cases of measles were identified; this also excluded further cases secondary to the two already identified. No other cases were identified in the population served by the hospital during the epidemiological investigation, and in the entire region throughout 2022.

The doctor was on duty the day of admission of the first case, but did not know that a measles case had been seen in the ED, and had not personally visited the patient or entered the isolation room; high compliance with PPE use and infection control procedures was reported during work. Of note, thorough training on FFP2 use had been performed in the ED involving all healthcare personnel. The public health specialists of the territorial unit went to the ED, following the “fever pathway” adopted for the two cases. After triage in a single room, when patients were provided with an FFP2 mask, both cases were placed in an isolation room -there are no negative pressure rooms available in the ED- where the doors have a push-button opening, and then into an “observation unit”, where the door have to be opened with a keyboard combination. No breaches in infections control procedures were identified. The hospital’s Occupational Medicine Unit provided the measles serological status of all ED staff, 49 doctors, and 111 nurses/healthcare assistants: 4 (8.2%) and 16 (14.4%), respectively, had not been tested; among tested HCW, one doctor (the case) (2.2%), and 7 nurses/healthcare assistants (7.4%) were susceptible. Among these 8 susceptible HCW, 7 were on duty the day of the hospitalization of the first case, plus 10 (2 doctors and 8 nurses/healthcare assistants) out of the 20 who had not been tested; apart from the doctor, however, no one else contracted measles.

To verify whether nosocomial transmission had occurred, the epidemiological investigation was combined with molecular investigation by measles virus genotyping [

6].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viral RNA Detection and Sequencing

Measles diagnosis was performed using a commercial real-time RT-PCR (Measles Virus Real Time RT-PCR LiferiverTM) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For sequence determination, a 450 nucleotides fragment of the N gene was amplified, using a nested PCR as previously described [

7]. Genotyping was determined based on Sanger sequencing, and both INMI cases were B3.

The Whole Genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on residual pellet urine samples from the INMI two cases.

The full genome of MeV was reverse transcript and amplified using OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) by a multiplexed PCR amplicon approach, using two pools of primers specific for B3, D4 and D8 genotypes (totalling 20 overlapping amplicons with a medium length of 1000 bps) according to Ponedos et al [

8].

Libraries were then prepared starting from 10-100 ng of DNA using Ion Xpress Plus Fragment Library Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and sequencing was performed on Gene Studio S5 Prime Sequencer (Thermofisher scientific Waltham, MA) to obtain approximately 1 million reads per sample.

2.2. Data Analysis

Raw data were analysed and all reads with average quality Phred score <20 were trimmed using Trimmomatic software v.0.39 [

9]. The entire MeV genome was reconstructed by mapping reads to the reference (MN630026) using BWA [

10]. In the subsequent analysis, only positions with a minimum coverage of 50 were considered.

The reference was selected using Blast on nr databases and the complete sequence closest to the Sanger fragment was selected. The assembled genomes were also manually checked using Geneious Prime v.2019.2.3. and the sequences alignment was represented as a logo using the WebLogo(10.1101/gr.849004) web application.

2.3. Phylogenetic Tree and Genetic Distance

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using all representative full-length sequenced genomes in B3 genotypes on NCBI (86 sequences). Furthermore, the recent complete genomes of the D8 strain sequenced in Italy were added and used as a phylogenetic outgroup. All 89 sequences were aligned with MAFFT v7.271 [

11] and checked manually using the Geneious prime program. Regions not covered in the INMI genomes were excluded in all genomes. Finally, only non-redundant sequences, identified with cd-hits, were considered in the subsequent analysis. Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis was performed with IQ-TREE v.1.6.12 [

12] and the best tree model was selected using the best DNA model included in MEGA X. The tree was built with the NT93+G model and 5000 bootstrap repetitions.

The average intra- and inter-group genetic distance of the B3 genomes detected in Europe, World, Italy and in the two INMI cases was calculated using MEGA X.

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Epidemiology

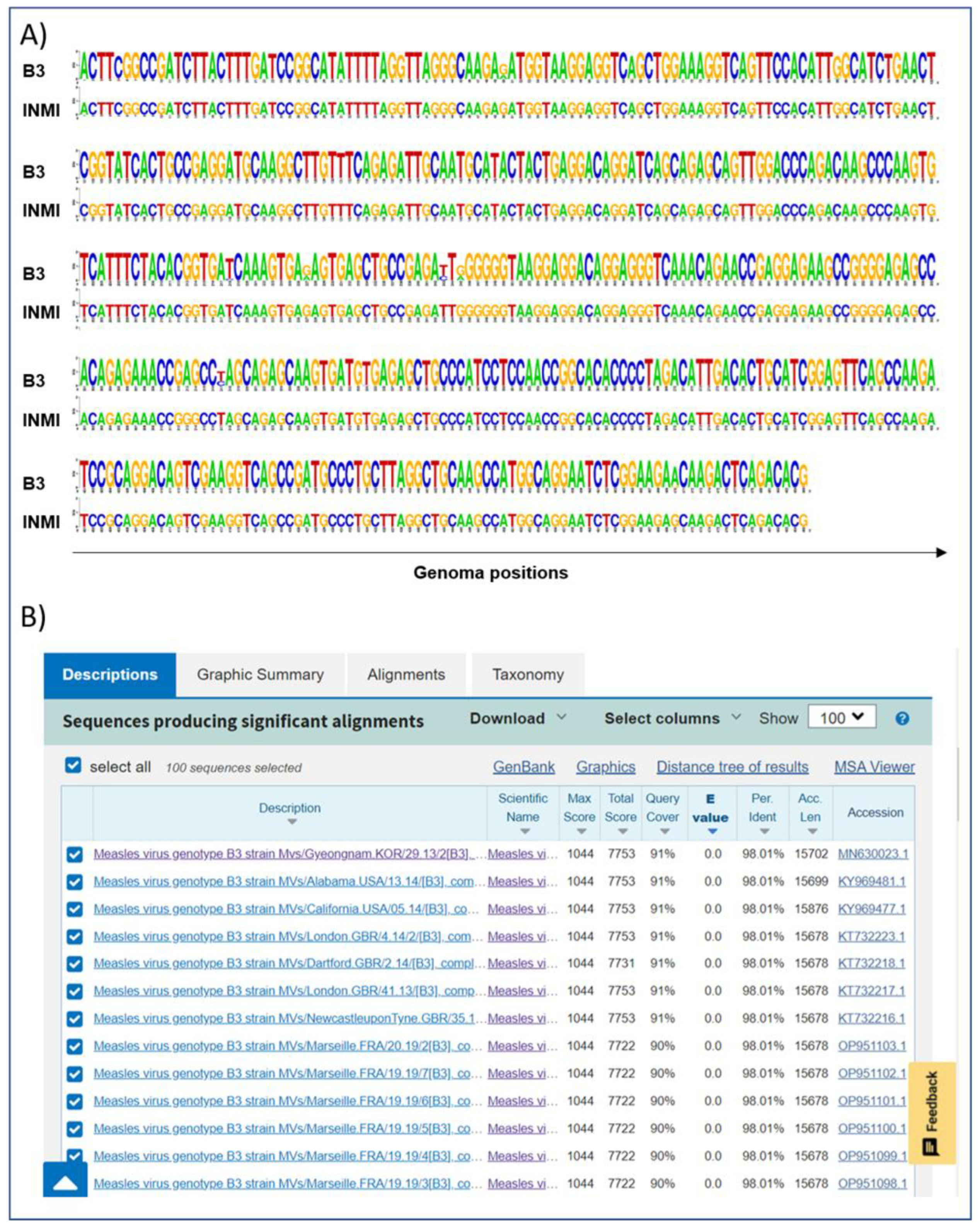

After identification by RT-PCR, a 450 bp amplicon on the N gene was sequenced with Sanger technology. The region covered by the sequencing shows that the two genomes belong to the B3 genotype and that the two fragments were identical (

Figure 1A).

To validate the correlation between the two infections, the entire MeV genome of the two patients was sequenced. The N fragment, obtained by the Sanger method, was used to identify the closest whole measles genome present in the GenBank nr database (MN630026,

Figure 1B) and, subsequently, this was used as a reference for the reconstruction of the entire MeV sequence in the patients studied.

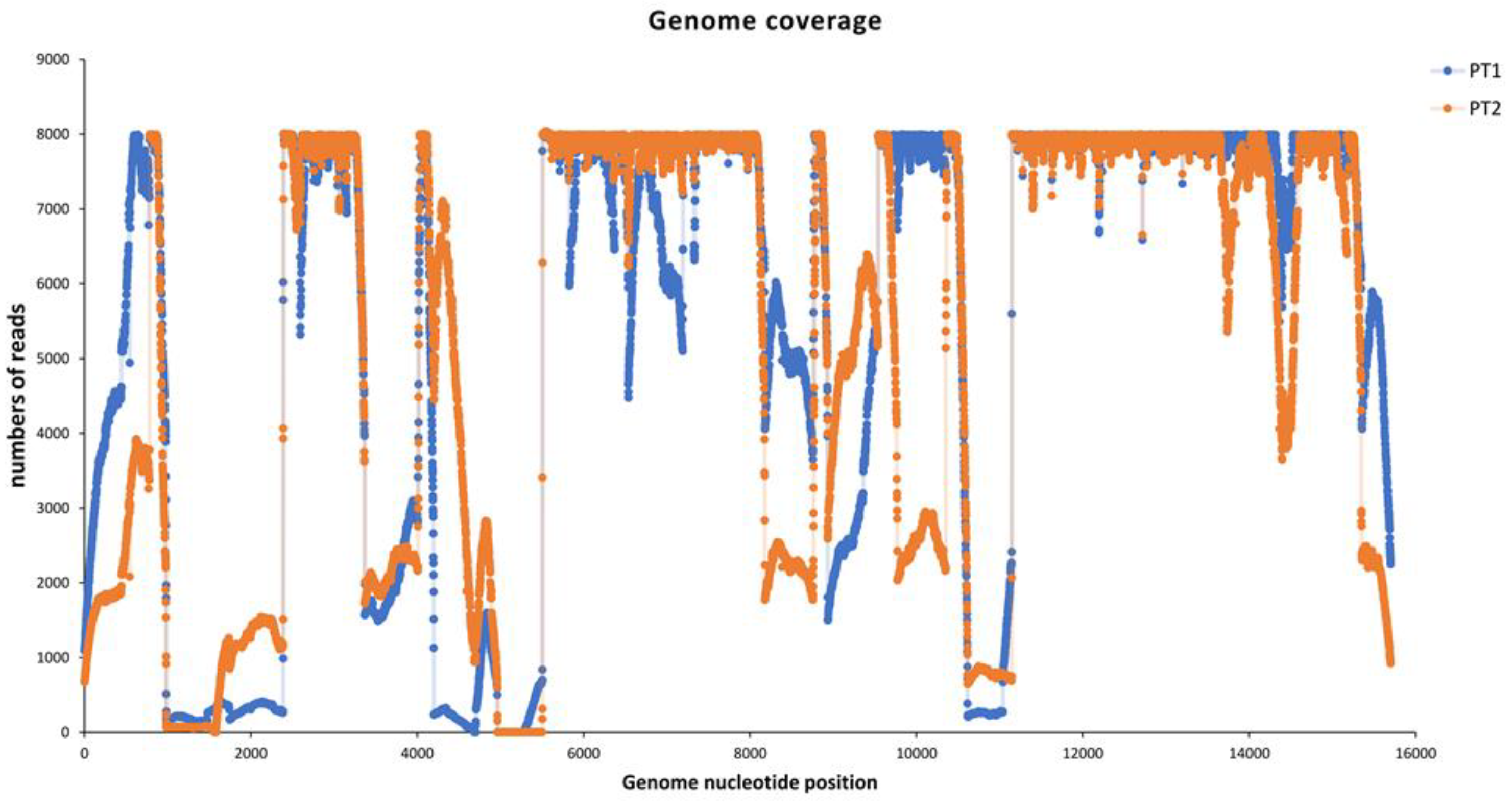

More than 1 million MeV reads were obtained for each sample, and the entire genome was reconstructed by mapping the reads to the reference. Full coverage of 97.9% and 96.6% was achieved for Pt1 and Pt2, respectively, with an average deep coverage of 14369.0±16678.3 and 12076.11±13761.5 (

Figure 2). In both genomes the same region of approximately 600 nt (near the reference position 4900 nu) showed coverage of less than 50 reads.

3.2. Phylogenetic and Distance Analysis

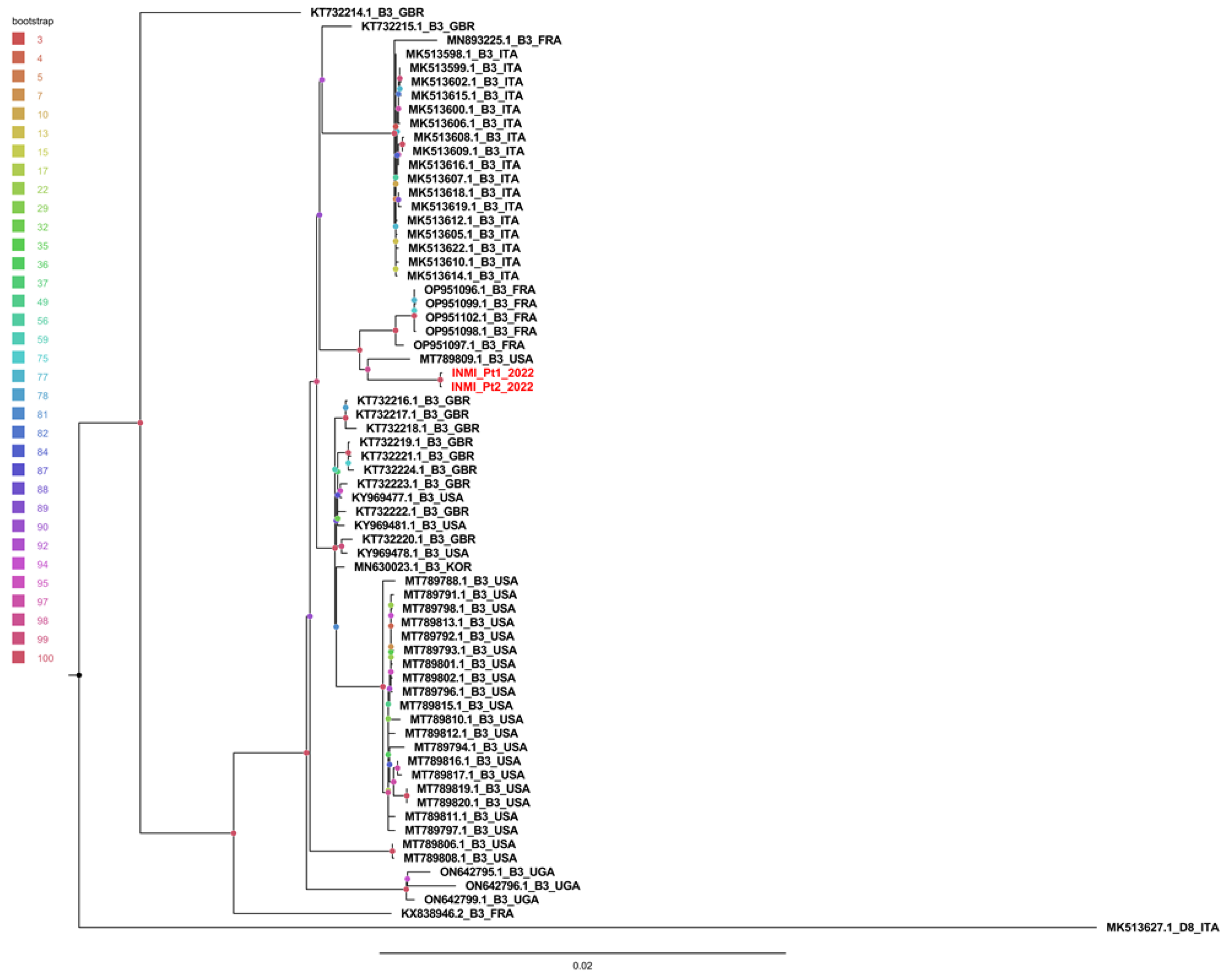

Phylogenetic tree was obtained using 87 whole MeV genomes (86 B3 genotypes and one D8 outgroup). Redundant genomes were eliminated, and the tree was constructed with 64 B3 genomes and 1 D8 genome. As shown in

Figure 3, INMI sequences clustered separately from other sequences with a significant bootstrap of 100%.

The sequences were then divided, with respect to the country of origin, into Italian, European and non-European, and compared with the INMI sequenced cases.

The average intragroup genetic distance (calculated using the p-distance model) showed that the distance between INMI sequences was significantly smaller than the distance between sequences present in other groups (

Table 1A). Furthermore, the average distance between groups revealed that INMI sequences were closer to European sequences than to Italian ones (Table1B).

4. Discussion

Molecular analysis provided evidence of nosocomial, patient-to-HCW transmission: the almost complete genome sequences obtained from the samples of the two cases studied here showed only one mutation and no sequences of other countries were identified as phylogenetically related. A minimum coverage of 50 reads was achieved across most of the entire genome, and a reliable consensus was reconstructed in 97% of MeV sequences. Only a region of ~500 bp was not covered in both sequences, near position 4900 of the genome reference, corresponding to the end of the M gene encoding the matrix protein. Although the diversity of the M protein in wildtype strain is relatively low and the gene is conserved in different members of paramyxoviruses, high tolerance for mutagenic events was observed [

13], consistently with the low amplification of this region we observed. However, the two regions that WHO identified as important for assessing epidemiological linkage were covered and the molecular results generated can be considered robust. Furthermore, in the phylogenetic tree the two INMI sequences clustered together with a 100% bootstrap, and were closer to the European and non-European sequences than to the Italian ones. This could mean that the virus came from foreign countries, or that not all the Italian circulating strains were sequenced and shared in the databases. However, the similarity was so close that hospital transmission could be confirmed by molecular and epidemiological data.

In Lazio, the adoption of strict isolation precautions against SARS-CoV-2 in ED was issued for the first time with a regional note dated 14 February 2020, imposing the use of standard precautions including respiratory hygiene, airborne, contact and droplet precautions [

14], and further strengthened several times, the last of which on 31 October 2022 [

15]. Thorough training was performed on proper use of PPE and facial respirators, and regularly repeated during the COVID-19 pandemic, in all hospitals, and certainly in the involved ED, by the infection control service staff.

Although all HCW wore full protective clothing and the source patient was provided with a face respirator, which has been shown to be more effective in reducing the viral spread of SARS-CoV2 in the environment [

16], the only susceptible doctor on duty contracted measles in spite of wearing full PPE, without having had any contact with the patient. Nosocomial transmission could have occurred either through the air, even after the patient’s discharge from hospital, given the long stay in the ED and the possible non-optimal adherence to the use of FFP2 due to the altered patient conditions. Alternatively, transmission could have occurred through indirect contact: the staff who treated the first case could have touched contaminated surfaces in close proximity to the patient, and subsequently opened doors with contaminated gloves; the ED doctor may subsequently have touched the contaminated buttons and inadvertently touched the mucous membranes of the face before removing the gloves. Though no evident breaches in infection control precautions could be identified, it was recommended to replace the button openings with a photoelectric opening, as well as vaccinating the remaining susceptible healthcare personnel. This outbreak confirms the absolute importance of primary prevention based on vaccinating susceptible HCW against measles and not relying solely on the effectiveness of personal protective equipment and infection control precautions. Indeed, in the case of SARS-CoV-2 even N95 masks were not able to completely block the transmission of virus droplets/aerosols even when completely sealed [

16]. If any additional preventive measure could be suggested in the ED against pathogens that transmit through the air [

17], and particularly against measles, whose infectious emission rate ranks first among respiratory pathogens [

18], this would be enhanced ventilation using engineering controls [

19].

5. Conclusions

As it already happened with SARS [

20], isolation precautions and use of full PPE including facial respirators were widely implemented in the ED during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, this did not prevent nosocomial measles transmission to occur. HCW, and particularly those who work in the ED, are the frontliners in healthcare delivery, and should therefore be vaccinated to act as a barrier against the spread of diffusive infectious diseases, such as measles, to protect themselves and their patients. Furthermore, they represent a reliable source of information on the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Their acceptance of measles vaccination will convey a stronger message to the general population, helping to curb the epidemic and move towards measles elimination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.C. and E.G.; methodology, E.G., G.B., M.R.; validation, E.G., E.L., L.F. and F.M.; formal analysis, M.D.A.; investigation, G.D.C., A.C., E.G., E.L., G.B., M.R., L.F., L.B.; data curation, M.C.F., V.V.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D.C., E.G..; writing—review and editing, F.V., P.S.; visualization, G.D.C.; supervision, P.S.; funding acquisition, F.V., F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health “Ricerca Corrente – Linea 1 – Progetto 2 - INMI L. Spallanzani I.R.C.C.S.” funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not needed for this study because human samples were collected as part of surveillance activities and the analysis was conducted as part of public health practice. Written informed consent was obtained from the cases to use the results of the analysis of human samples collected as part of surveillance activities and the report of clinical and epidemiological data collected as part of public health practice. Care was taken to present anonymized data that limit the possibility to identify individuals.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data obtained in this study have been deposited into GenBank (Accession numbers: PP446317 - PP446318).

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank the patients for agreeing to have their cases reported for the good of public health.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Servizio Regionale per l'Epidemiologia Sorveglianza e controllo delle Malattie Infettive, SeRESMI. Report dei casi di morbillo notificati nella Regione Lazio 01/01/2017-31/12/2017. Available online: https://www.inmi.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Report_Morbillo_2017.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Regione Lazio-Direzione Salute e Integrazione Sociosanitaria. Nota Regionale U.0523849.17-10-2017. Available online: https://www.vaccinarsinlazio.org/assets/uploads/files/7/06.circolare-0523849-17-10-2017-pnpv-2017-2019-operatori-sanitari.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Decreto – legge n. 73 del 7 giugno 2017, convertito con modificazioni dalla legge 31 luglio 2017, n. 119. Available online: http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/dettaglioAtto?id=60201, and enclosed, Piano Nazionale per la Prevenzione Vaccinale (PNPV) 2017 - 2019 http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Regione Lazio-Direzione Salute e Integrazione Sociosanitaria. Nota Regionale U.0397892.24-05-2019. Situazione epidemiologica Morbillo. Regione Lazio - Indicazioni di Sorveglianza, controllo e prevenzione.

- Magurano F, Baggieri M, Mazzilli F, Bucci P, Marchi A, Nicoletti L; MoRoNet Group. Measles in Italy: Viral strains and crossing borders. Int J Infect Dis. 2019, 79, 199-201. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genetic Analysis of Measles Viruses Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/php/laboratories/genetic-analysis.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/measles/lab-tools/genetic-analysis.html. (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Bankamp B, Byrd-Leotis LA, Lopareva EN, Woo GK, Liu C, Jee Y, Ahmed H, Lim WW, Ramamurty N, Mulders MN, Featherstone D, Bellini WJ, Rota PA. Improving molecular tools for global surveillance of measles virus. J Clin Virol.. 2013, 58, 176-82. [CrossRef]

- Penedos AR, Myers R, Hadef B, Aladin F, Brown KE. Assessment of the Utility of Whole Genome Sequencing of Measles Virus in the Characterisation of Outbreaks. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0143081. [CrossRef]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014, 30, 2114-20. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25, 1754-60. [CrossRef]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013, 30, 772-80. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015, 32, 268-74. [CrossRef]

- Beaty SM, Lee B. Constraints on the Genetic and Antigenic Variability of Measles Virus. Viruses. 2016, 8, 109. [CrossRef]

- Regione Lazio-Direzione Salute e Integrazione Sociosanitaria. Nota Regionale 0133296.14-02-2020: Infezione da nuovo coronavirus 2019 nCoV (COVID-19). Indicazioni operative per la gestione e la sorveglianza nella Regione Lazio. Available online: https://www.snamiroma.org/wp1/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Prot.0133296_Coronavirus_Indicazioni-operative_14-02-2020.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Regione Lazio-Direzione Salute e Integrazione Sociosanitaria. Determinazione 31 ottobre 2022, n. G14889. Misure per la prevenzione e gestione dei contagi da COVID-19: utilizzo delle mascherine nelle strutture sanitarie, socio-sanitarie e socio-assistenziali, nel periodo 1° novembre 2022 - 31 marzo 2023. Available online: https://www.inapp.gov.it/strumenti-normativa/norme-regionali/lazio-determinazione-direttoriale-31-ottobre-2022-n-g14889/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Ueki H, Furusawa Y, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Imai M, Kabata H, Nishimura H, Kawaoka Y. Effectiveness of Face Masks in Preventing Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. mSphere. 2020, 5, e00637-20. [CrossRef]

- Global technical consultation report on proposed terminology for pathogens that transmit through the air. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-technical-consultation-report-on-proposed-terminology-for-pathogens-that-transmit-through-the-air (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Mikszewski A, Stabile L, Buonanno G, Morawska L. The airborne contagiousness of respiratory viruses: A comparative analysis and implications for mitigation. Geosci Front. 2022, 13, 101285. [CrossRef]

- Morawska L, Tang JW, Bahnfleth W, Bluyssen PM, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, Cao J, Dancer S, Floto A, Franchimon F, Haworth C, Hogeling J, Isaxon C, Jimenez JL, Kurnitski J, Li Y, Loomans M, Marks G, Marr LC, Mazzarella L, Melikov AK, Miller S, Milton DK, Nazaroff W, Nielsen PV, Noakes C, Peccia J, Querol X, Sekhar C, Seppänen O, Tanabe SI, Tellier R, Tham KW, Wargocki P, Wierzbicka A, Yao M. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Environ Int. 2020, 142, 105832. [CrossRef]

- Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Infection control for the disinterested. CMAJ. 2003, 169, 122-3. PMID: 12874160; PMCID: PMC164978.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).