Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Isnard, J.; Guenot, M.; Sindou, M.; Mauguiere, F. Clinical manifestations of insular lobe seizures: A stereo-electroencephalographic study. Epilepsia 2004, 45, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzola, L.; Mauguiere, F.; Isnard, J. Electrical Stimulations of the Human Insula: Their Contribution to the Ictal Semiology of Insular Seizures. J Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 34, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.K.; Nguyen, D.B.; Malak, R.; Leroux, J.M.; Carmant, L.; Saint-Hilaire, J.M.; Giard, N.; Cossette, P.; Bouthillier, A. Revisiting the role of the insula in refractory partial epilepsy. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citherlet, D.; Boucher, O.; Tremblay, J.; Robert, M.; Gallagher, A.; Bouthillier, A.; Lepore, F.; Nguyen, D.K. Spatiotemporal dynamics of auditory information processing in the insular cortex: An intracranial EEG study using an oddball paradigm. Brain Struct Funct 2020, 225, 1537–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, A.; Bellier, L.; Blenkmann, A.O.; Ivanovic, J.; Larsson, P.G.; Lin, J.J.; Endestad, T.; Solbakk, A.K.; Knight, R.T. Decision and response monitoring during working memory are sequentially represented in the human insula. iScience 2023, 26, 107653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvizi, J.; Kastner, S. Promises and limitations of human intracranial electroencephalography. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, A.; Thornton, R.C.; Tisdall, M.M.; Scott, R.C. Microelectrode recordings in human epilepsy: A case for clinical translation. Brain Commun 2020, 2, fcaa082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Sanchez, J.C. Quantifying long-term microelectrode array functionality using chronic in vivo impedance testing. J Neural Eng 2012, 9, 026028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.D.; Quiroga, R.Q.; Freeman, J.; Smith, S.L. Improving data quality in neuronal population recordings. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukamel, R.; Fried, I. Human intracranial recordings and cognitive neuroscience. Annu Rev Psychol 2012, 63, 511–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreira, C.; Martinez, J.; Ison, M.J.; Quiroga, R.Q. How many neurons can we see with current spike sorting algorithms? J Journal of neuroscience methods 2012, 211, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, W.C.; Kellis, S.; Greger, B.; Butson, C.R.; Patel, P.R.; Assaf, T.; Mihaylova, T.; Glynn, S. Potential for unreliable interpretation of EEG recorded with microelectrodes. Epilepsia 2013, 54, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

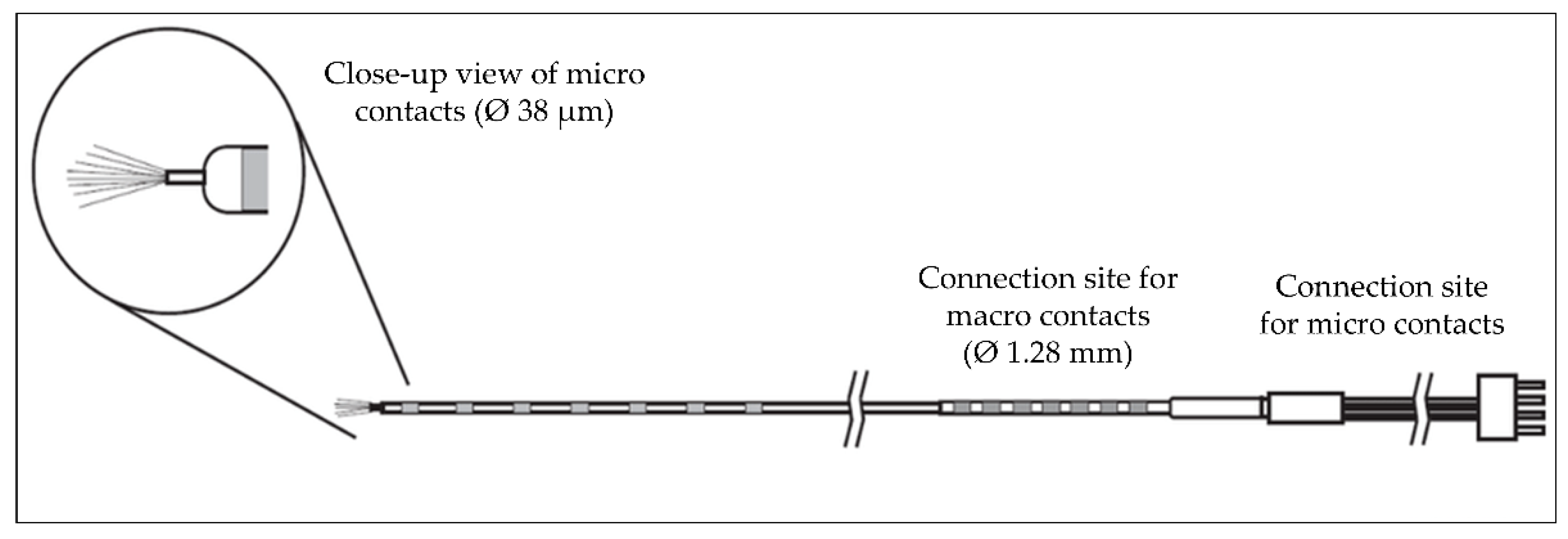

- Carlson, A.A.; Rutishauser, U.; Mamelak, A.N. Safety and Utility of Hybrid Depth Electrodes for Seizure Localization and Single-Unit Neuronal Recording. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2018, 96, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, H.M.; Hall, J.A.; Dubeau, F.; Tani, N.; Oshino, S.; Fujita, Y.; Gotman, J.; Kishima, H. Technical Aspects of SEEG and Its Interpretation in the Delineation of the Epileptogenic Zone. Neurol Med Chir 2020, 60, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, A.; Burke, J.F.; Ramayya, A.G.; Jacobs, J.; Sperling, M.R.; Moxon, K.A.; Kahana, M.J.; Evans, J.J.; Sharan, A.D. Methods for implantation of micro-wire bundles and optimization of single/multi-unit recordings from human mesial temporal lobe. J Neural Eng 2014, 11, 026013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, A.S.-M.S.; Caravan, B.; Mamelak, A.N. Which Are the Most Important Aspects of Microelectrode Implantation? In Intracranial EEG, Axmacher, N., Ed. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp 671-682.

- Lambrecq, V.; Lehongre, K.; Adam, C.; Frazzini, V.; Mathon, B.; Clemenceau, S.; Hasboun, D.; Charpier, S.; Baulac, M.; Navarro, V.; Le Van Quyen, M. Single-unit activities during the transition to seizures in deep mesial structures. Ann Neurol 2017, 82, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schevon, C.A.; Ng, S.K.; Cappell, J.; Goodman, R.R.; McKhann, G., Jr.; Waziri, A.; Branner, A.; Sosunov, A.; Schroeder, C.E.; Emerson, R.G. Microphysiology of epileptiform activity in human neocortex. J Clin Neurophysiol 2008, 25, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schevon, C.A.; Weiss, S.A.; McKhann, G., Jr.; Goodman, R.R.; Yuste, R.; Emerson, R.G.; Trevelyan, A.J. Evidence of an inhibitory restraint of seizure activity in humans. Nat Commun 2012, 3, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.A.; Alvarado-Rojas, C.; Bragin, A.; Behnke, E.; Fields, T.; Fried, I.; Engel, J., Jr.; Staba, R. Ictal onset patterns of local field potentials, high frequency oscillations, and unit activity in human mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahian, B.; Lado, N.E.; Mankin, E.; Vangala, S.; Misra, A.; Moxon, K.; Fried, I.; Sharan, A.; Yeasin, M.; Staba, R.; Bragin, A.; Avoli, M.; Sperling, M.R.; Engel, J., Jr.; Weiss, S.A. Low-voltage fast seizures in humans begin with increased interneuron firing. Ann Neurol 2018, 84, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truccolo, W.; Donoghue, J.A.; Hochberg, L.R.; Eskandar, E.N.; Madsen, J.R.; Anderson, W.S.; Brown, E.N.; Halgren, E.; Cash, S.S. Single-neuron dynamics in human focal epilepsy. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staba, R.J.; Wilson, C.L.; Bragin, A.; Fried, I.; Engel, J., Jr. Quantitative analysis of high-frequency oscillations (80-500 Hz) recorded in human epileptic hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol 2002, 88, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, M.; Bower, M.; Brinkmann, B.H.; Lee, K.; Marsh, W.R.; Meyer, F.B.; Litt, B.; Van Gompel, J.; Worrell, G.A. Microseizures and the spatiotemporal scales of human partial epilepsy. Brain 2010, 133, 2789–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.K.; Moll, C.K.; Fried, I.; Ojemann, G.A. Invasive recordings from the human brain: Clinical insights and beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005, 6, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Cosgrove, G.R.; Madsen, J.R.; Eskandar, E.N.; Hochberg, L.R.; Cash, S.S.; Truccolo, W. Early Detection of Human Epileptic Seizures Based on Intracortical Microelectrode Array Signals. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2020, 67, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.M.; Dykstra, A.R.; Jayaram, V.; Leonard, M.K.; Travis, K.E.; Gygi, B.; Baker, J.M.; Eskandar, E.; Hochberg, L.R.; Halgren, E.; Cash, S.S. Speech-specific tuning of neurons in human superior temporal gyrus. Cereb Cortex 2014, 24, 2679–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, M.J.; Quian Quiroga, R.; Fried, I. Rapid Encoding of New Memories by Individual Neurons in the Human Brain. Neuron 2015, 87, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucewicz, M.T.; Michael Berry, B.; Bower, M.R.; Cimbalnik, J.; Svehlik, V.; Matt Stead, S.; Worrell, G.A. Combined Single Neuron Unit Activity and Local Field Potential Oscillations in a Human Visual Recognition Memory Task. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2016, 63, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, R.Q. Concept cells: The building blocks of declarative memory functions. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, J.; Sullivan, S.; Chung, J.M.; Ross, I.B.; Mamelak, A.N.; Rutishauser, U. Persistently active neurons in human medial frontal and medial temporal lobe support working memory. J Nature neuroscience 2017, 20, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutishauser, U.; Reddy, L.; Mormann, F.; Sarnthein, J. The Architecture of Human Memory: Insights from Human Single-Neuron Recordings. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutishauser, U.; Ross, I.B.; Mamelak, A.N.; Schuman, E.M. Human memory strength is predicted by theta-frequency phase-locking of single neurons. Nature 2010, 464, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Tudusciuc, O.; Mamelak, A.N.; Ross, I.B.; Adolphs, R.; Rutishauser, U. Neurons in the human amygdala selective for perceived emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, E3110–E3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yu, R.; Tyszka, J.M.; Zhen, S.; Kovach, C.; Sun, S.; Huang, Y.; Hurlemann, R.; Ross, I.B.; Chung, J.M.; Mamelak, A.N.; Adolphs, R.; Rutishauser, U. The human amygdala parametrically encodes the intensity of specific facial emotions and their categorical ambiguity. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterman, Y.; Mukamel, R.; Malach, R.; Fried, I.; Nelken, I. Ultra-fine frequency tuning revealed in single neurons of human auditory cortex. Nature 2008, 451, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decramer, T.; Premereur, E.; Zhu, Q.; Van Paesschen, W.; van Loon, J.; Vanduffel, W.; Taubert, J.; Janssen, P.; Theys, T. Single-Unit Recordings Reveal the Selectivity of a Human Face Area. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 9340–9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormann, F.; Niediek, J.; Tudusciuc, O.; Quesada, C.M.; Coenen, V.A.; Elger, C.E.; Adolphs, R. Neurons in the human amygdala encode face identity, but not gaze direction. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 1568–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, S.; Zerouali, Y.; Nguyen, D.K. Insular Epilepsy: Semiology and Noninvasive Investigations. J Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 34, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surbeck, W.; Bouthillier, A.; Weil, A.G.; Crevier, L.; Carmant, L.; Lortie, A.; Major, P.; Nguyen, D.K. The combination of subdural and depth electrodes for intracranial EEG investigation of suspected insular (perisylvian) epilepsy. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ture, U.; Yasargil, D.C.; Al-Mefty, O.; Yasargil, M.G. Topographic anatomy of the insular region. J Neurosurg 1999, 90, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolla, N. The insular cortex. Curr Biol 2017, 27, R580–R586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, L.Q.; Nomi, J.S.; Hebert-Seropian, B.; Ghaziri, J.; Boucher, O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 34, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamm, C.; Singer, T. The role of anterior insular cortex in social emotions. Brain Struct Funct 2010, 214, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shura, R.D.; Hurley, R.A.; Taber, K.H. Insular cortex: Structural and functional neuroanatomy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014, 26, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, L.Q.; Kinnison, J.; Pessoa, L.; Anderson, M.L. Beyond the tripartite cognition-emotion-interoception model of the human insular cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 2014, 26, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchewka, A.; Zurawski, L.; Jednorog, K.; Grabowska, A. The Nencki Affective Picture System (NAPS): Introduction to a novel, standardized, wide-range, high-quality, realistic picture database. Behav Res Methods 2014, 46, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaure, F.J.; Rey, H.G.; Quian Quiroga, R. A novel and fully automatic spike-sorting implementation with variable number of features. J Neurophysiol 2018, 120, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, C.; Henze, D.A.; Koch, C.; Buzsaki, G. On the origin of the extracellular action potential waveform: A modeling study. J Neurophysiol 2006, 95, 3113–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, M.; Wiseman, S.; Domany, E. Superparamagnetic clustering of data. Phys Rev Lett 1996, 76, 3251–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraut, M.C.M.; Carlson, A.A.; Sullivan, S.; Tudusciuc, O.; Ross, I.; Reed, C.M.; Chung, J.M.; Mamelak, A.N.; Rutishauser, U. Dataset of human medial temporal lobe single neuron activity during declarative memory encoding and recognition. Sci Data 2018, 5, 180010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, R.Q.; Nadasdy, Z.; Ben-Shaul, Y. Unsupervised spike detection and sorting with wavelets and superparamagnetic clustering. Neural Comput 2004, 16, 1661–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, G.R.; Softky, W.R.; Koch, C.; Douglas, R.J. Comparison of discharge variability in vitro and in vivo in cat visual cortex neurons. J Neurophysiol 1996, 75, 1806–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afif, A.; Chabardes, S.; Minotti, L.; Kahane, P.; Hoffmann, D. Safety and usefulness of insular depth electrodes implanted via an oblique approach in patients with epilepsy. Neurosurgery 2008, 62 (Suppl. S2), ONS471–9; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Sánchez-Morla, E.M.; Santos, J.L. A new method for removal of powerline interference in ECG and EEG recordings. Comput Electr Eng 2015, 45, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehongre, K.; Lambrecq, V.; Whitmarsh, S.; Frazzini, V.; Cousyn, L.; Soleil, D.; Fernandez-Vidal, S.; Mathon, B.; Houot, M.; Lemarechal, J.D.; Clemenceau, S.; Hasboun, D.; Adam, C.; Navarro, V. Long-term deep intracerebral microelectrode recordings in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: Proposed guidelines based on 10-year experience. Neuroimage 2022, 254, 119116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.A.; Miriani, R.M.; Langhals, N.B.; Joseph, M.D.; Anderson, D.J.; Kipke, D.R. Using a common average reference to improve cortical neuron recordings from microelectrode arrays. J Neurophysiol 2009, 101, 1679–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banstola, A.; Silva, C.; Ulrich, K.; Ruan, M.; Robertson, L.; McNaughton, N. Construction of simple, customised, brain-spanning, multi-channel, linear microelectrode arrays. J Neurosci Methods 2021, 348, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient number |

Sex | No. of electrodes implanted |

Localization of electrodes implanted | No. of hybrid depth electrodes and localization1 | Surgery following implantation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 17 | 8 R (aI, pI, amygdala, aH, pH, PCC, precuneus, cuneus) and 9 L (aI, pI, amygdala, aH, pH, PCC, precuneus/cuneus) | 2 (R pI, L pI) | L temporal lobectomy |

| 2 | M | 12 | 6 R (aI, pI, amygdala, aH, pH, OT, O) and 6 L (aI, pI, amygdala, aH, pH, OT, O) | 2 (L and R aI/pI) | No surgery |

| 3 | F | 14 | 2 R (pI, aI) and 12 L (pI, aI, P, angular, T, F, PCC) | 1 (R pI) | No surgery |

| 4 | M | 10 | 10 R (aI, pI, aH, pH, amygdala, OF, F op) | 1 (R pI) | No surgery |

| 5 | M | 10 | 10 R (aI, pI, amygdala, aH, pH, OF, ACC, PCC, median F) | 2 (R aI, R pI) | No surgery |

| 6 | F | 13 | 4 R (ACC, mesial F, OF) and 9 L (amygdala, aH, pH, OF, ACC, MCC, median F) | 2 (L aI, L pI) | L temporal lobectomy |

| 7 | F | 12 | 12 R (pI, P, ant and post precuneus, PCC, ACC, MCC) | 1 (R pI) | No surgery |

| 8 | F | 12 | 12 R (aI, pI, amygdala, pH, aH, ACC, IFG, OF, F P T op, P) | 2 (R aI, R pI) | R anterior temporal lobectomy |

| 9 | F | 11 | 1 R (aI) and 10 L (aI, pI, amygdala, aH, pH, OF, T) | 2 (R aI, L pI) | No surgery |

| 10 | M | 10 | 10 L (aI, pI, p parahippocampal, op T, fusiform, OF) | 2 (L aI, L pI) | L insular lobe resection |

| 11 | M | 10 | 10 R (aI, pI, ACC, MCC, PCC, OF, median F) | 2 (R aI, R pI) | No surgery |

| 12 | F | 14 | 8 R (aI, superior insula, T, OF, PCC, op P-T) and 6 L (aI, pI, amygdala, aH, pH, OF) | 2 (R aI, L aI) | No surgery |

| 13 | M | 16 | 16 R (aI, pI, amygdala, F op, P op, ACC, PCC, ant/mid/post median frontal, fusiform area) | 2 (R aI, R amygdala) | R frontal corticectomy |

| Total | 161 | 23 | |||

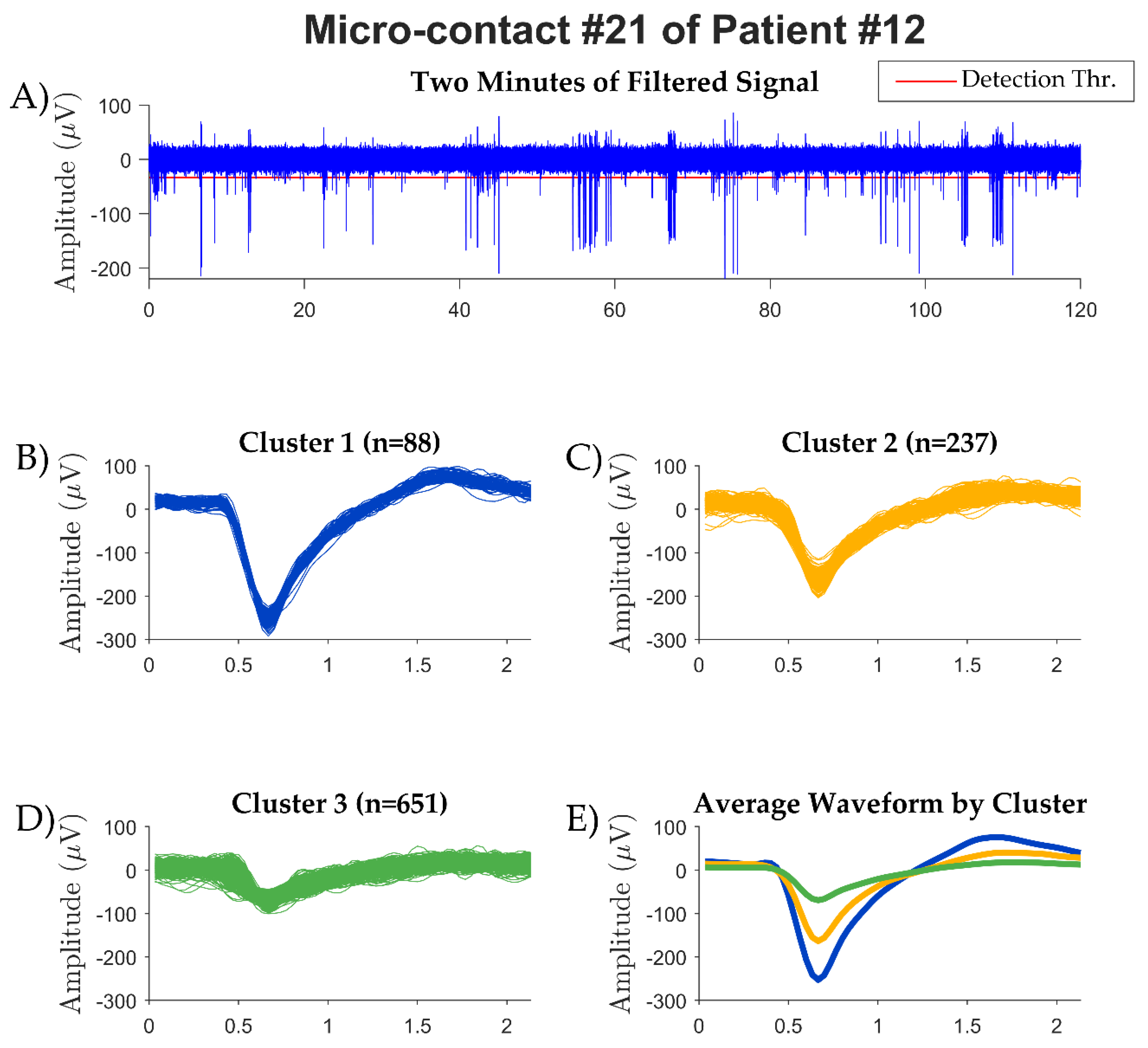

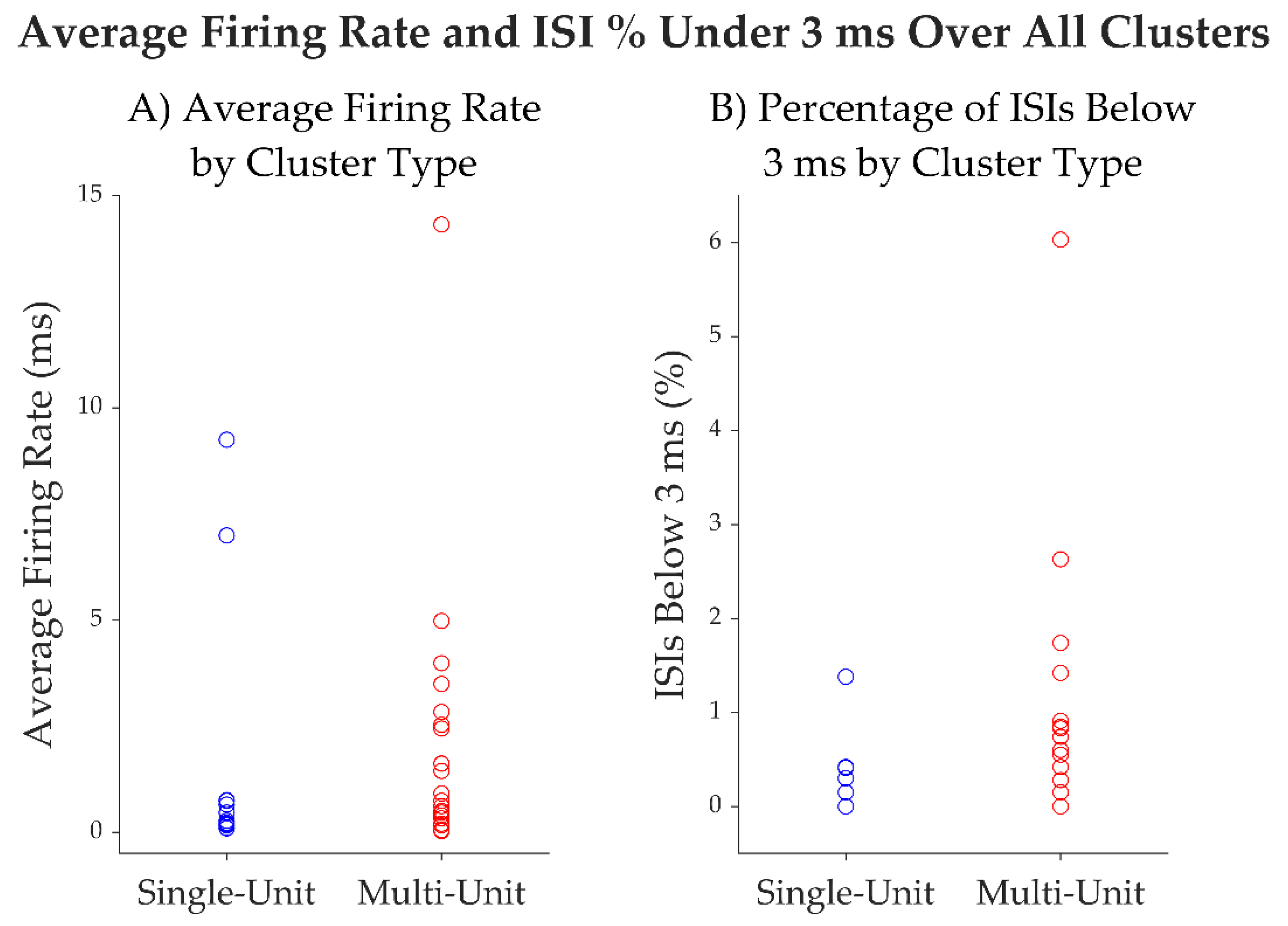

| Patients1. | duration of recording (min:sec) |

No. of microcontacts2 with neuronal activity | No. of well isolated units | No. of putative multi units detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 05:08 | 2/16 | 1 | 3 |

| 10 | 24:25 | 6/16 | 6 | 9 |

| 12 | 14:40 | 3/16 | 4 | 6 |

| 13 | 03:57 | 2/16 | 1 | 3 |

| 13/64 (20.3%) | 12 | 21 |

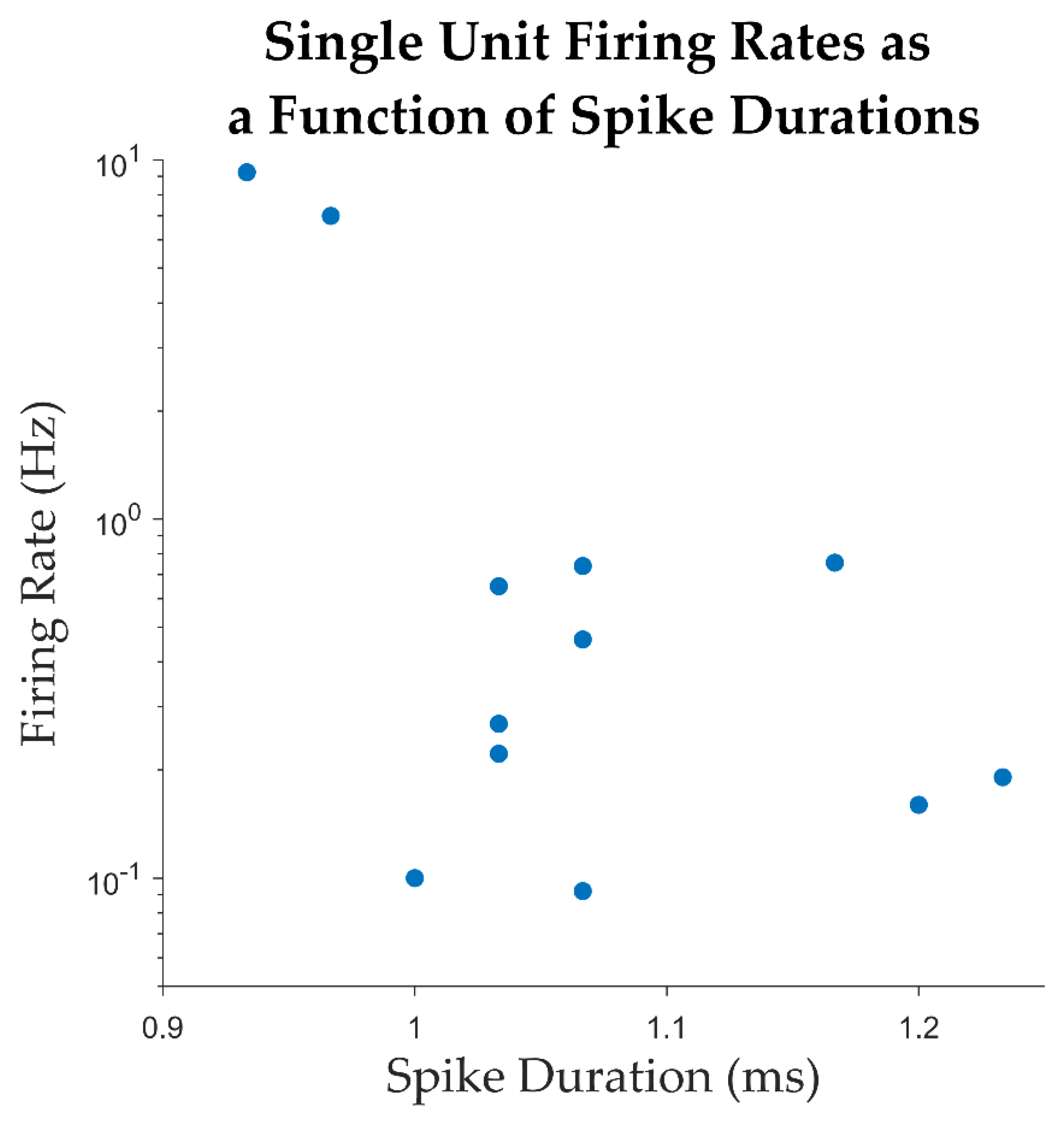

| Unit ID | Average firing rate (Hz) |

Average spike width (ms) | % intervals below 3 ms | Trough to Peak SNR | CV2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.22 | 1.03 | 0 | 5.87 | 1.1 |

| 2 | 9.24 | 0.93 | 1.38% | 3.82 | 1 |

| 3 | 6.99 | 0.97 | 0.41% | 4.32 | 0.8 |

| 4 | 0.65 | 1.03 | 0 | 5.62 | 1 |

| 5 | 0.16 | 1.20 | 0 | 7.33 | 1.2 |

| 6 | 0.19 | 1.23 | 0 | 3.87 | 1.3 |

| 7 | 0.09 | 1.07 | 0 | 6.22 | 1.2 |

| 8 | 0.76 | 1.17 | 0.30% | 2.93 | 1.1 |

| 9 | 0.27 | 1.03 | 0.42% | 7.64 | 1.2 |

| 10 | 0.74 | 1.07 | 0.15% | 3.27 | 1.1 |

| 11 | 0.1 | 1.00 | 0 | 12.33 | 1.2 |

| 12 | 0.46 | 1.07 | 0 | 3.55 | 1.1 |

| mean | 1.66 | 1.07 | 0.22 | 5.56 | 1.10 |

| median | 0.3 | 1.05 | 0.00 | 4.97 | 1.1 |

| SD | 3.07 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 2.65 | 0.14 |

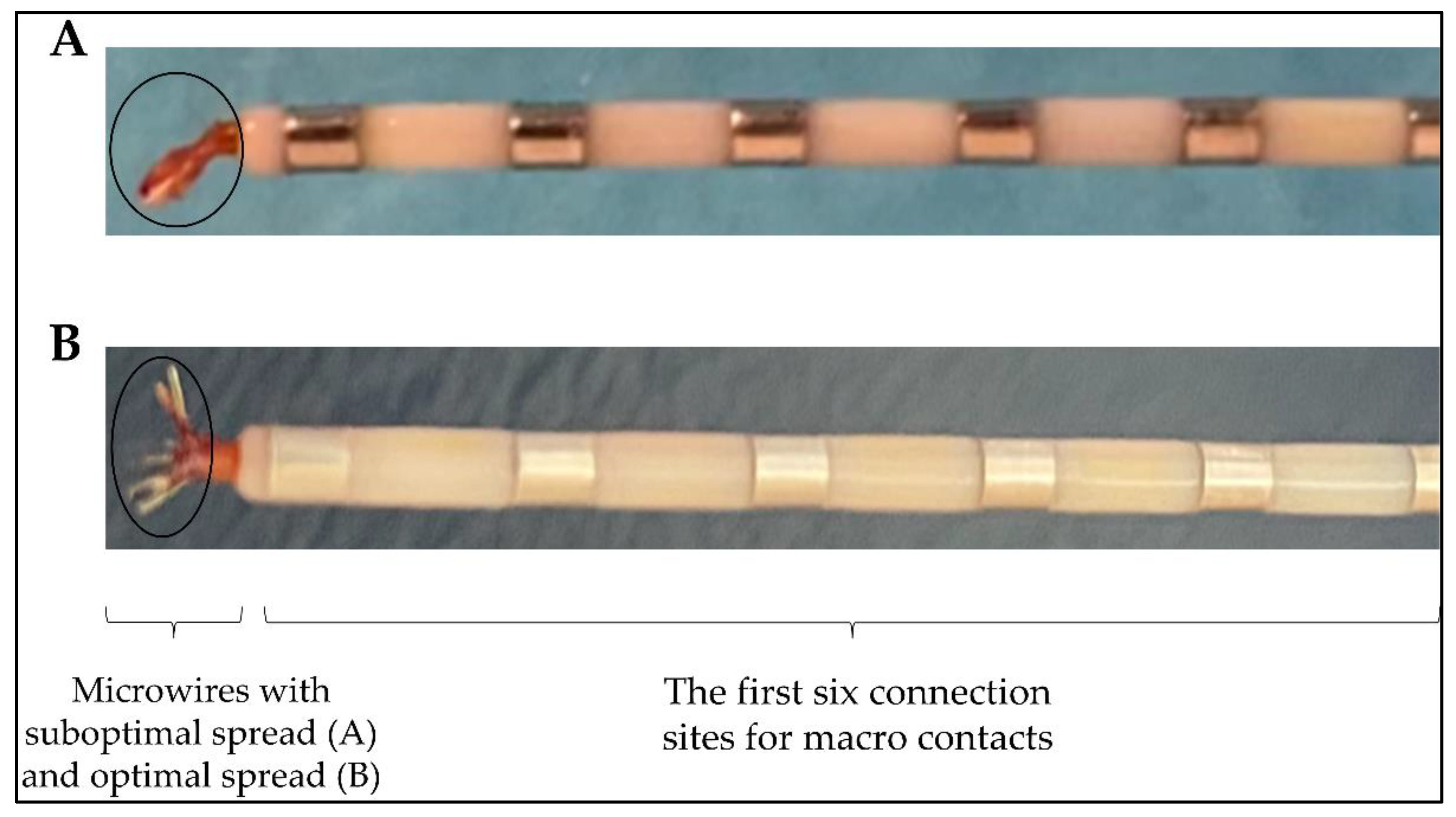

| Encountered difficulties | Recommendations | |

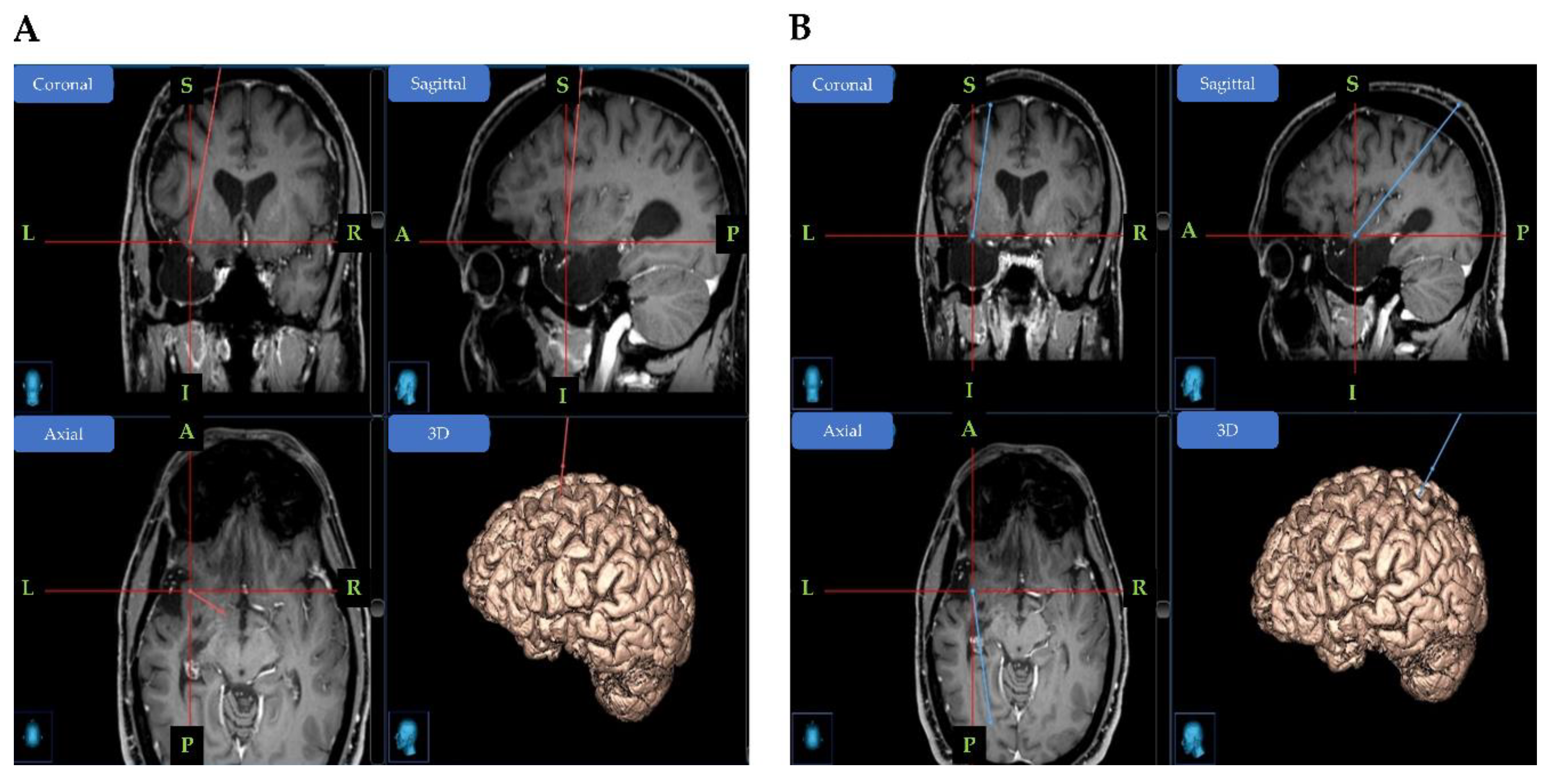

| Implantation surgery | Microwires bundled | Spread the wires before insertion.Check the spread wires in the MRI post-implantation. |

| Hybrid electrode trajectories | Prior to the insertion of microelectrodes into the macroelectrodes, microwires must be cut to the desired length defined during the planning surgery. | |

| Post- implantation surgery |

Hybrid electrodes without microcontact signal | Do not bend and/or pull the cables of the electrodes.Test the patient as soon as possible following the surgery implantation.Confirm the localization of the microcontacts in the grey or white matter. |

| Testing | Power line contamination | Use shielded cables, aluminum foils.Unplug all devices in the room of the patient.Use a power conditioner for laptop, optical cable and/or wireless.No cellphone in the room. |

| Artifacts | Check the reference electrode and the ground.Stabilize the Cabrio connector, headstage and cables.Minimize movements by the patient. All connector cables in the same direction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).