1. Introduction

In the beginning of the 21st century, theories evolve faster because of high-speed computing, data collection, and interdisciplinary science stimulating by the advent of artificial intelligence and quantum computing. In fact, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has transformed from a theoretical concept to a crucial part of modern society. Its evolution has been shaped by advances in mathematics, computing power, neuroscience, and data availability. This transformation is deeply rooted in the evolution of AI theories, which have gradually aligned with the complexities of the real world.

The real world consists of all physical entities and phenomena, such as mountains, rivers, animals, and human-made objects such as cars and phones. Humans interpret and understand this reality through mental representations known as concepts, which are abstract ideas that help categorize and make sense of the myriad elements in our environment. Humans perceive the physical world through their five senses [

1]: sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. For example, when encountering a lion on a mountain, an individual uses these senses to recognize and respond to the animal. Each observed lion is unique; no two lions are identical. However, through experience and learning, humans develop the abstract concept of a "lion", which encompasses the general characteristics and attributes common to all lions. This concept does not exist physically but resides in the cognitive realm, allowing for the classification and understanding of individual lions encountered in reality. Concepts [

2] serve as the foundational elements of human thought, enabling processes such as classification, learning, inference, and decision making. By forming concepts, humans can group individual entities based on shared characteristics, facilitating efficient processing and understanding of information. For example, the concept of a "chair" allows individuals to recognize and categorize various types of chairs, despite differences in design or material, based on their common purpose and features.

In computer science, representing real-world entities and abstract concepts requires the use of appropriate data structures. Sets, as defined in set theory, are fundamental structures employed to model collections of distinct objects. A set is an unordered collection that contains unique elements, reflecting the mathematical concept of a finite set. This abstraction aligns with how concepts group individual instances sharing common properties. For instance, the concept of a "lion" can be represented in a computer system as a set containing all instances of lions; i.e., each lion is an element within this set. This representation allows for efficient data processing and retrieval, enabling machines to perform operations such as classification, search, and pattern recognition based on the defined sets. Hence, sets provide a basis for various computational operations and algorithms. They facilitate the organization of data into manageable and logical groupings, allowing machines to perform tasks such as union, intersection, and difference operations. These set operations are crucial in fields such as database management, information retrieval, and artificial intelligence, where the ability to manipulate and analyze groups of related data is essential.

Consequently, the interplay between the physical world, human cognition, and computational representation is intricate and profound. Humans perceive tangible entities through their senses and abstract commonalities into concepts, which are then utilized in thought processes. In computing, these concepts are modeled using data structures like sets, enabling machines to process and analyze information effectively. This alignment between human cognitive frameworks and computational models underscores the importance of set theory and related abstractions in both understanding the world and designing intelligent systems capable of engaging with the complexities of the real world.

In the near future, AI systems will live with humans in the real world, serving as assistant agents or collaborating in hybrid teams to perform specific tasks autonomously. The relationship between abstract concepts, their mathematical representation as sets, and their human perception is central to understanding how meaning is formed and shared, or misunderstood, across individuals and contexts. In cognitive science, concepts such as “lion” are mental abstractions that can be represented formally as sets that contain all instances that satisfy the concept. For example, the concept “lion” can be modeled as a set L, including biological lions, their behaviors, habitats and symbolic associations.

Now consider a more context-specific abstraction: “lion of Atlas”. This refers to a concept that is a specialization or contextual refinement of L, thus in set-theoretic terms. However, this formal subset relation does not capture the full semantic divergence introduced by individual, cultural, and linguistic contexts. In practice, “lion of Atlas” can mean radically different things to different people, depending on their background knowledge and interpretive context. For example, a biologist can interpret “lion of Atlas” as referring to the subspecies of lion that roamed the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. However, a Moroccan football fan can immediately associate “lion of Atlas” with the national football team.

Thus, concepts, sets, perceptions, and computing are four key cornerstones, which may play a pivotal role in the development of future AI-dependent society, where AI is not just a tool but a new frontier in intelligence and lifestyles. The relationship between the real world, concepts, and mathematical sets is a profound topic that bridges philosophy, cognitive science, and mathematics. In fact, perception is a fundamental issue in epistemology as it directly influences our understanding of reality, knowledge, and truth. Different theories have emerged to explain how humans perceive the world, each with different implications for knowledge acquisition, see

Section 2. Today, computing is challenged by the new roles of machines, which are going beyond their classical role, consisting of playing with numbers to perform very quickly a huge number of numerical operations. In fact, machines interact with and serve humans; they are not only connected together, but they are also connected to humans. But can machines think [

3] and have abilities of humans to live in the world? Humans achieve goals during their daily life using, among other things, their ability to think, see

Section 3. Thus, set theory has evolved significantly from Cantor’s classical set theory to modern extensions such as fuzzy and rough sets. These developments reflect the adaptation of mathematical theories to better model uncertainty, vagueness, and incomplete information in real-world applications, see

Section 4.

This work is part of the evolution of sets that adapt to the real world inhabited by humans. The oSets are sets that depend not only on their members, but also on their observers.

Section 5 introduces fundamental notions and properties, whereas different classes of perception functions are studied in

Section 6. We interpret sets, such as fuzzy and rough sets, through perception in

Section 7. Finally, a general discussion and concluding remarks are developed in

Section 8 and

Section 9, respectively.

2. Perception in Epistemology

Epistemology is the study of knowledge [

4], where perception is a fundamental topic because it relates to how we gain knowledge about the world. In fact, perception plays a crucial role in epistemology, as it is one of the primary ways humans acquire information about the world. Philosophers debate whether perception provides direct or indirect access to reality and whether it can serve as a reliable foundation for knowledge. A fundamental question is: can we trust perception as a "source of knowledge"? This question explores whether sensory experience provides reliable knowledge about reality.

Several arguments are in favor of trusting perception, for example, most of our everyday knowledge (e.g., seeing a tree, hearing a voice) comes from perception, Moreover, our perceptions generally match up over time, i.e., if we see a car on the road, we can later touch it, reinforcing its existence. However, there are other arguments against trusting perception, for example perception errors. In fact, optical illusions, hallucinations, and mirages show that perception can be misleading, so if it can deceive us sometimes, how do we know it is ever accurate? Also, subjectivity of experience, as different people perceive the same thing differently (e.g., color blindness, taste preferences). This suggests that perception is not a purely objective way of knowing.

Beyond trusting perception, the following important question is asked: does perception give us direct access to reality, or is it shaped by the Mind? This question explores whether perception is a passive reflection of the world or if the mind actively interprets sensory input. Two main perceptions theories are developed in epistemology: Direct Access and Indirect Access theories. Direct Access theories (Direct realism or Naive Realism), consider that the world exists as we see it. Objects have properties such as color, shape, and size that we perceive directly. Alternatively, Indirect Access Theories (Constructivism and Idealism) have allowed the emergence of several perception schools [

5]:

Naive realism ([

6]): is an Aristotelian theory, where we directly perceive the world as it is; i.e. things are what they seem and our perception of the world reflects it exactly as it is, unbiased and unfiltered. According to this school, we simply receive information about the world through our senses and our consciousness “mimics” reality in some way, i.e., objects have the properties that they appear to us as they really are. Hence, perception is passive as it consists in the absorption of the external world into consciousness.

Representative Realism (John Locke [

7] and René Descartes [

8]): The mind does not perceive the external world directly; instead, it perceives mental representations of objects. For example, when we see a tree, we are not experiencing the tree itself but an image processed by our brain.

Transcendental Idealism (Immanuel Kant [

9]): The mind actively organizes perception. We never perceive the world "as it is" but only through our mental filters (space and time). For example, imagine wearing colored glasses that tint everything blue. We never see things as they are, only how our mind structures them.

Idealism (George Berkeley [

10]): This school is defended by George Berkeley, who is persuaded by the thought that we only have direct access to our experiences of the world, but not to the world itself, asserting that

to be is to be perceived. Thus, objects are nothing more than our experiences of them, and God is constantly perceiving everything to ensure the continued existence of objects of the world.

In the 1950s, John McCarthy highlighted the epistemological problems of artificial intelligence [

11], and thought that artificial intelligence has closer scientific connections with philosophy than do other sciences [

12]. Since then, AI researchers have sought to replicate human perception, asking: can machines perceive like humans? Today, in computer vision, AI analyzes images to recognize objects, faces, and text, with applications in self-driving cars and medical imaging. In natural language processing (NLP), AI interprets language for tasks such as chatbots and translation. AI also integrates data from multiple sensors, such as cameras, microphones, and radar, to create a more comprehensive perception, used in autonomous robots and drones. In doing so, AI processes data through mathematical models and pattern recognition, lacking intuitive comprehension and requiring specific training for novel scenarios. In contrast, human perception integrates sensory input with memory and experience, enabling holistic understanding and adaptability to new situations. Humans can be deceived by optical illusions due to misinterpretation of sensory information, whereas AI systems are vulnerable to adversarial attacks, where minor input alterations lead to misclassification. Additionally, humans naturally grasp context and subtleties such as sarcasm, whereas AI often struggles with nuanced meanings and contextual variations.

In conclusion, while AI is powerful in data processing and pattern recognition, human perception remains superior in flexibility, intuition, and contextual awareness. AI continues to evolve, but it has yet to reach the depth of human understanding. Hence, we introduce oSets based on perception theories developed in epistemology while advocating for a computing-with-perception framework to improve Human-AI symbiosis [

13].

3. Computing with Perception

Automation refers to the use of technology, such as software, algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI), and robotic systems, to perform tasks with less or more autonomy and human intervention. Through AI and natural language processing (NLP), it enables real-time analysis of human communication on social networks, filtering, and categorizing massive volumes of data. This improves user experience and platform regulation by detecting trends, monitoring sentiment, and identifying misinformation. However, significant challenges remain, including biases in AI models, privacy concerns, and errors in detecting misinformation.

Beyond data-driven processing, human perception significantly influences how information is understood and interpreted. Perception is shaped not only by the five senses, but also by individual factors such as education, culture, personal experiences, and the real operational context in which human acts. In an increasingly connected world, people continuously share information and perspectives, even when they hold different worldviews. This growing interconnectedness fosters rich exchanges, but also highlights conflicting perceptions, often leading to debate and confrontation. The expansion of digital communication platforms, social media, and transportation technologies has made the world feel smaller than ever. These advances facilitate the rapid dissemination of opinions, sentiments, sarcasm, and even misinformation. The widespread nature of online communication means that information reaches diverse audiences, each interpreting it through their perception. Consequently, AI-powered systems must evolve to account for the diversity of human perception.

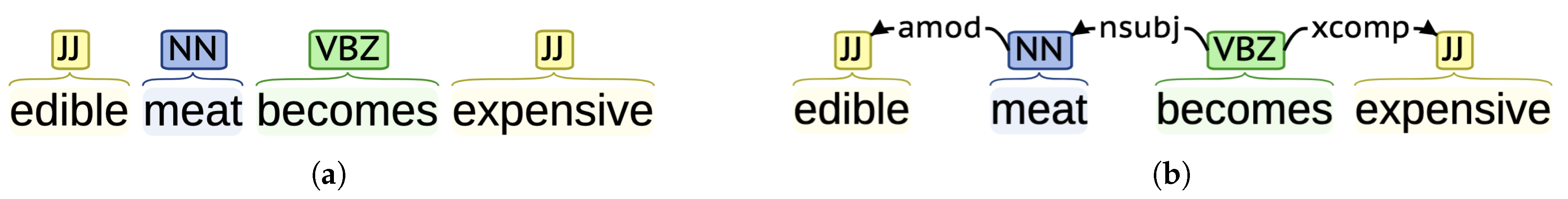

In his paper [

14], L.A. Zadeh pointed out that "Humans have a remarkable capability to perform a wide variety of physical and mental tasks without any measurements and any computations". He introduces the computational theory of perceptions (CTP) by acknowledging the intrinsic imprecision of perceptions and incorporating fuzzy sets. Here, we introduce oSets and focus on the diversity of perceptions. For example, consider the short message "Edible meat becomes expensive!" being shared on social media platforms. It is generally analyzed using natural language processing tools. Let us analyze it using the CoreNLP tool, which assigns specific parts of speech to each word to understand their grammatical roles. In this case, "Edible" is tagged as an adjective (JJ), "meat" as a noun (NN), "becomes" as a verb (VBZ), and "expensive" as an adjective (JJ). Beyond identifying parts of speech, CoreNLP examines the grammatical relationships between words through dependency parsing. This process reveals how words connect to convey meaning. For instance, "edible" modifies "meat," indicating the type of meat being discussed. "Meat" serves as the subject of the verb "becomes", which denotes a change of state. The word "expensive" functions as the complement, describing the new state of "meat" (

Figure 1).

However, understanding "Edible meat becomes expensive!" requires real-world knowledge and contextual awareness. NLP tools recognize the basic sentence structure, but we need to fully capture the meaning of the message according to the diversity of human perception. In fact, "Meat" is a broad term, and different cultures define "edible meat" differently. Some consume beef and pork, while others eat horses, dogs, or cats. The term meat is broad, and the definition of "edible meat" varies across cultures. Although some societies consume beef and pork, others may include horse, dog, or cat meat in their diet. AI often assumes a universal definition of "meat", applying statements indiscriminately across all cultures. However, dietary customs vary significantly. In some Asian countries, dog and cat meat is consumed, whereas in much of Europe, these animals are regarded as pets. Horse meat is eaten in certain parts of Europe but is largely avoided in England. In contrast, while beef is widely consumed in Arab countries, cows are considered sacred in India. Meanwhile, vegetarians and vegans refrain from eating meat altogether. Ultimately, the concept of "edible meat" is shaped by cultural norms, traditions, personal beliefs and preferences. We show in

Section 4 how oSets represent this diversity of perception of the concept "edible meat".

4. From Cantorian Sets to oSets

The classical set theory was introduced by G. Cantor in late 1873, defining a set as "a collection into a whole, of definite, well-distinguished objects (called the ’elements’) of our perception or of our thought..." The standard definition of a classical set is: "a set is a well-determined collections that are completely characterized by their elements". Furthermore, the basic relation in the theory of sets is that of membership, denoted ∈, where

indicates that the element

x is a member of the set

X. However, the naive use of the set notion led to several inconsistencies, such as Russell’s paradox [

15]. To avoid inconsistency, Zermelo and Fraenkel adopted an axiomatic approach leading to the well known ZFC set theory.

Beyond these initial considerations, a multitude of non-classical set theories emerged during the last half-century aspiring to supplement the classical set theory, i.e., Heyting-valued set theory, intuitionistic and constructive set theory, quantum set theory, Fuzzy sets, Rough sets, etc. Various factors have contributed to the development of these theories. For example, the classical membership function is Boolean, assigning values from

and disregarding repetitions, since an element cannot appear more than once in a set. Multisets lift the occurrence constraint, taking into account repeated elements in a set, and the number of times an element occurs is called its multiplicity. Hence, the binary membership function is extended to consider the multiplicity of an element in a set, and

is interpreted as "The element

x belongs to the set

X with a multiplicity of

n". Moreover, Lotfi A. Zadeh noted that the Boolean function is often inadequate in real world scenarios, as objects in the physical world rarely have strictly defined membership criteria [

16]. Consequently, he introduced a membership function that assigns values within the interval

, allowing an element to belong to a set to varying degrees. To maintain notational consistency, we denote the fuzzy membership relation as

, where

means that

x is a member of the fuzzy set

X with a membership degree

. Alternatively, Z. Pawlak pointed out that the relation "belongs to" is not an absolute property, but depends upon our knowledge, which is summarized by the relation

R. He introduced Rough Sets [

17] using an equivalence relation

R as available knowledge claiming that knowledge is deep and rooted in the classificatory abilities of human beings. A set

X is said to be R-definable if it is the union of some R-basic categories; otherwise it is said to be R-undefinable or rough. Hence, a rough set cannot be known exactly, with respect to our knowledge, but it can only be approximated by two sets called lower and upper approximations. Consequently,

x belongs to the lower approximation of

X, denoted

, means that

x surely belongs to

X with respect to

R, whereas

x possibly belongs to

X with respect to

R when it is a member of its upper approximation, i.e,

. More generally, many non-Cantorian sets theories have been put forth to grow beyond the traditional binary ’belongs to’ relation relying on different notions like cardinality, multiplicity, plurality, distinguishability, discernibility, definability, etc.

The aim of this paper is to continue this effort considering that our knowledge is closely related to our perception and assuming this central assumption: the relation "belongs to" does not just involve elements and sets, but it also implies observers. Let us return to the previous message "Edible meat becomes expensive!", which is broadcasted in social networks. Its meaning depends on the semantics of the concept "Edible meat", represented by the set X, which is ultimately private depending on the reader of the message or observer. In fact, the interpretation of a person is shaped by what they consider "edible meat". In some Asian countries, dog and cat meat is consumed, whereas in much of Europe, these animals are regarded as pets. Horse meat is eaten in certain parts of Europe but is largely avoided in England. In contrast, while beef is widely consumed in Arab countries, cows are considered sacred in India. Meanwhile, vegetarians and vegans refrain from eating meat altogether. According to this example, the set X is represented by one of the following sets according to the reader of the boardcasted message, which may be, for example, Asian, European, English, Arabic, Hindu or Vegetarian: , , , , and . Food choices are deeply tied to culture, religion, and personal beliefs, making interpretation highly subjective. For this reason, the concept of "edible meat" cannot be represented by a single set. Thus, we propose to represent the semantics of the concept "Edible meat" by a family of sets to take into account the diversity of its perception, i.e. , where is the semantic function. In conclusion, the concept of "edible meat" is represented by Set , which is a family of sets that reflect the perception diversity of its observers.

Consequently, we face classes that are not only characterized by their members but also depend on perceptions of their observers. Such classes do not constitute usual sets, but they form a family of sets depending on the diversity of their perceptions. When a class is reduced to only one set, regardless of its perception, it is said to be accessible. Humans seem to be familiar with non-accessible sets because their education, values, socioeconomic status, experiences, and more generally their egocentric particulars are different, which leads to the diversity of their perception of the world. In short, the diversity of perception necessarily leads to a plurality of representation, so we are in the same world, but each lives in his own world.

5. Fundamental Notions and Properties

No two trees are identical; each is unique, but all trees belong to the general concept of a "tree". Although an individual tree, or object, exists in reality, the concept of a "tree" is an abstract idea.

Given a set

U of objects of the real world denoted by

x, the set of all parts (subsets) of

U is called the power set of

U and is generally denoted by

, which is the collection of all subsets of

U, including the empty set and

U itself. Each object

x of

U is represented by the set

, therefore all objects are represented by the set of parts of

U such that their cardinality is equal to 1. This is the set of all single element subsets (or singleton sets) of

U, denoted by:

where

means that each subset

X contains exactly one element from

U. Concepts are part of

U such that their cardinality is greater than or equal to 2. This is the collection of all subsets of

U that contain at least two elements, denoted by:

These notations clearly define objects and concepts that are subsets of the power set of .

In modern philosophy and cognitive science, the concept notion refers to mental representations or abstract ideas that we use to categorize and understand the world. Concepts are the building blocks of our thoughts and knowledge, allowing us to recognize and reason about objects, events, and ideas. Human perception interacts with reality through the senses, so we introduce a function that encodes how an individual i perceives objects in the world. Moreover, perception also extends to abstract concepts, processed through a separate function . Thus, each individual i possesses a unique perception function , combining both and to perceive objects and concepts, respectively.

Definition 1 (Perception space). A perception space is a pair , where U is a non empty set called universe, and is a set of observers.

When , the observer i perceives only , but not X and, consequently substitutes X in his own perception universe . This perception diversity is summarized as follows: We are in the same world (U), but each lives in his own world (), where is the perception space of i: .

Definition 2 (Object perception function g). Let U be the universe, i be an observer, then , such that is the perception of the object by the observer i.

In the remainder of this paper, we assume that this perception function of objects satisfies the following three minimal coherence properties:

Using these properties, note that objects of the universe are not necessarily perceived as they are, because we assume only that , but note .

Example 1 (Object perception).

Table 1 shows seven objects of the real world U, i.e., a bee, an eagle, a drone, a pigeon, a robot, a lizard, and a parrot, represented by elements and , respectively. These objects are perceived by five observers. The observer 1 perceives objects are they are, i.e., , whereas observers 2 and 3 fail to distinguish some objects from others. In fact, the observer 2 confuses the pigeon with the parrot , and the robot with the lizard , even if he perceives the bee , eagle and drone as they are.

Beyond this individual perception of objects, an observer can also perceive categories of objects, or concepts.

Definition 3 (Concept perception function f). Let U be the universe, i be an observer, then , such that is the perception of X by the observer i.

The concept perception function f can be built on g using a given property . For example, iff , where is a given property, such as , , , , and , where , P and are belief, probability, and plausibility measures, respectively.

Example 2 (Concept perception).

Taking into account the objects introduced in Table 1, the concept "Flying animals" is represented by the set . Considering, for example, that , then the perceptions of the concept Z by the three observers are , . Thus, the observer 1 perceives each object as it is and the concept Z as well, whereas the observer 2 perceives Z as it is even if he confuses some objects of the universe, e.g, . Furthermore, the observer 3. have a partially correct perception of Z.

Beyond these mathematical properties that reflect the imprecise and uncertain character of humans, we can consider other properties based on features behind the diversity of human perception, due to multiple biological, cognitive, cultural, and psychological factors, for example:

Sensory variability: Differences in sensory organs (e.g., vision, hearing) affect perception. Color blindness alters how a person sees colors; what looks "red" to one person might appear as "brown" to another.

Cognitive processing and prior knowledge: The brain filters and interprets information based on past experiences, education, memory, context, goal to meet, etc. Two people watching the same ambiguous image (e.g., the famous "duck-rabbit" illusion) may see different shapes depending on their mental expectations.

Cultural background and social influences: Language, traditions, and education influence how concepts and emotions are understood. In western cultures, white symbolizes purity, while in some eastern cultures it represents mourning. The same color carries different meanings based on cultural perception.

Emotional and psychological state: Mood and mental state shape perception and decision-making. A person feeling anxious might interpret a neutral face as threatening, whereas someone in a calm state may see it as indifferent.

Personal interests and preferences: Subjective biases affect attention and value judgments. A musician and a mathematician listening to a piece of music may focus on different aspects, the melody vs. the mathematical structure of the rhythm.

In short, human perception of the same reality varies due to multiple factors, and these differences shape how individuals interpret, judge, and react to the world around them. Thus, we introduce two perception functions g, and f, which allow us to perceive objects and concepts, respectively. These two functions are the basis for the perception function of the observers.

Definition 4 (Perception function ). Let U be the universe, i be an observer, then , which defines his perception as follows:

A constructive approach to define the perception function is to consider that the object perception function is generated by a binary relation . Hence, the perception of objects is represented by clusters of related objects or granules, that is, granular perception. Then construct based on and a given property to define , which is the perception function of the observer i.

Definition 5 (Granular perception function - see

Table 1).

Let U be the universe, i be a given observer, be a binary relation in U and a predefined property. The perception of i is granular if is generated by on U, i.e., , , and is based on according to a property , i.e., .

To extend the individual perception function considering several observers I, we use a family of sets reflecting the principle of variability of perception. This multiplicity of perception of the same reality between several observers is defined by the function

Definition 6 (Perception function ). Let U be the universe of objects, I be a set of observers, and be the perception function of the set of observers I, which is defined as follows:

Hence, the perception of by a set of observers is a family of sets consisting of an index set I and, for each observer , represents the perception of X by the observer i.

Definition 7 (Accessible set).

Given a perception space , and the perception function of the observer , is said accessible, in , if and only if,

So, if X is accessible, it means that there is a consensus among observers who perceive X as it is; otherwise, an element can be a member of X for an observer, but not for another. Note that this accessibility notion is Boolean as a set is accessible to all observers in I or not. However, a set X may only be accessible to one observer or a subset of observers in I, hence the possible extension of this notion to consider relative accessibility. Thus, the membership function not only links an element x to a set X but also establishes a ternary membership relation that incorporates observers.

Definition 8 (Ternary Membership Relation

).

Given a perception space , and the perception function of the observer . The element is perceived by i, to be a member of the set is denoted , where:

Thus, we introduce a new notion of membership, denoted

, where

indicates that observer i perceives the element x as belonging to the set X. In doing so, we do not exclude the variability of perceptions, assuming their multiplicity. In fact, the observer

i has his own universe

constructed according to his perception function and used for reasoning, decision making, interacting with outside and collaborating in teaming. Such personal universes may be identical to the real world; more or less different or completely different, as developed in epistemology; see

Section 2.

In conclusion, a set X is said to be accessible if it is independent of its observers; otherwise, it is said to be an observer-dependent set or oSet, which cannot be known exactly with respect to its observers, but it can only be approximated by a family of sets representing the diversity of its perception. Thus, accessibility is intrinsically dependent on perception, expressed as to be accessible is to be perceived in contrast to Berkeley’s idealist paradigm, to be is to be perceived, which asserts that the existence of an object is contingent on its perception by a conscious mind. In other words, for something to exist, it must be perceived by a subject; otherwise, it has no independent reality. We will now focus on a some perception function classes, considering, for example, naive, pessimistic, optimistic, and doubtful perceptions.

6. Perception Function Classes

Naive observers perceive the world as it is; therefore, the elementship relation is independent of observers, and consequently, we face an absolute truth as , or for all observers.

6.1. Naive or Cantorian Perception Function (NR class)

Definition 9 (Naive Perception Functions).

Given a perception space , the perception function , where , belongs to the class of naive or Cantorian perception class if and only if:

Hence, all naive observers have the same perception function, which is equal to the identity function. The identity function on a set X is a function that maps every element of X to itself. In other words, for every element , . This means that applying the identity function to any element in X does not change its value, it simply returns the same element. Thus, , where as is the identity perception function (i.e., ).

Proposition 1. The following properties hold for naive perception functions:

(6.1.1) Equality: ;

(6.1.2) ;

(6.1.3) Union: = ;

(6.1.4) Monotony: ;

(6.1.5) Idempotent: ;

(6.1.6) Accessibility: ;

Proposition 2. For naive observers, all sets are accessible.

Proof: by (6.1.6)

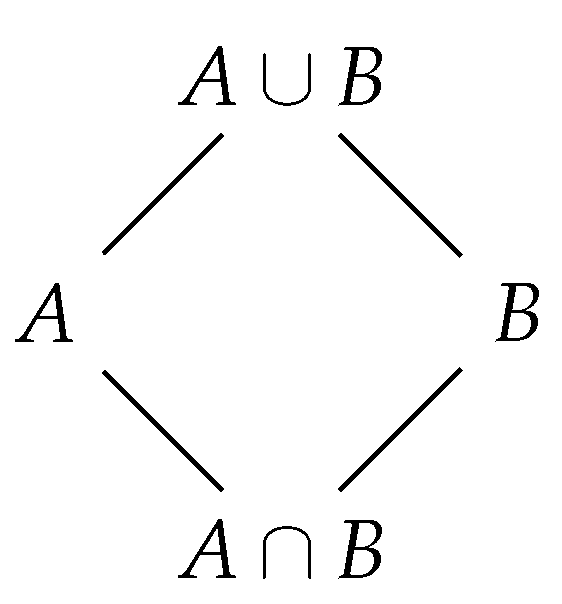

Furthermore, naive observers construct the algebraic structure

, for example,

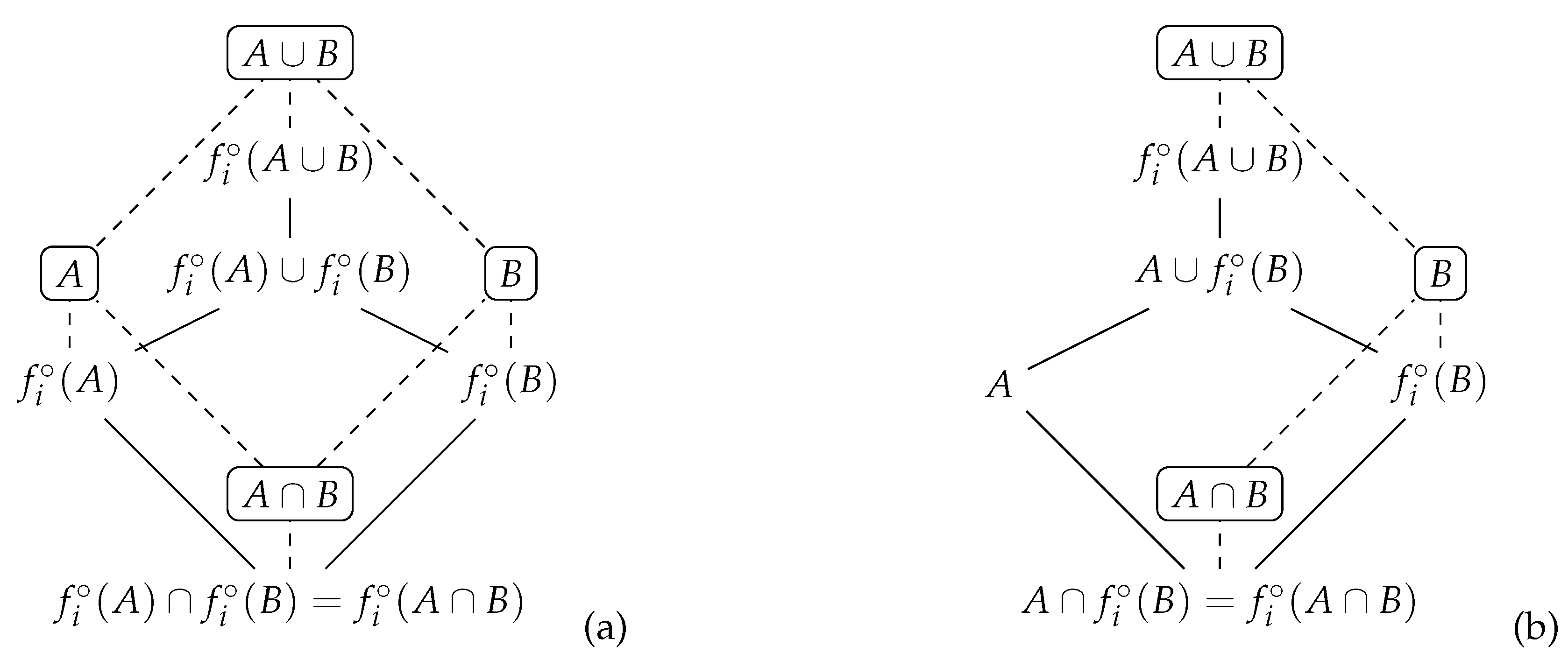

Figure 2 depicts this structure considering two sets

A and

B.

In conclusion, naive perception corresponds to the

naive realism theory (see

Section 2), where perception is a passive process, as objects of the world have the properties that they appear to us to have. Furthermore, from a mathematical viewpoint, this perception corresponds to Cantor’s set theory, which defines crisp sets using a Boolean membership relation excluding any variation of their perception.

Now, we consider that objects have primary and secondary qualities as assumed by the representative realism school (see

Section 2), and consequently, they can be perceived differently from one observer to another. In this Representative Realism (RR) class, we distinguish three different perception functions called Pessimistic, Optimistic, and Doubtful. For simplicity, we consider that the perception fondtion of objects (i.e.,

g) is always the same for all these three perception functions; see

Table 1, and then we construct the perception functions of concepts accordingly.

6.2. Pessimistic Perception Function

Definition 10 (Pessimistic Perception).

Given a perception space , an observer , the pessimistic perception function, denoted , is defined as follows:

Thus, an object x is a member of perception , if and only if the perceptions of its members are included in X (i.e., ).

Proposition 3. The following properties hold for pessimistic perceptions:

(6.2.1) Intersection:

(6.2.2) Union:

(6.2.3) Monotony:

(6.2.4) Idempotent:

(6.2.5) Accessibility:

The main difference from naive perception concerns both the union and the monotony of perceptions. In fact, the union of two perceptions is not necessarily equal to the perception of their union (

6.2.2). In addition, a pessimistic perception of

X is only included in it, but not necessarily equal to it (

6.2.5). Furthermore, a pessimistic perception

is not necessarily injective, for example

(see

Table 1,

).

Proposition 4. Not all sets are necessarily accessible for pessimistic perceptions.

Proof: by (6.2.5).

Proposition 5. If are accessible, then and are also accessible for pessimistic perceptions.

Proof:

if A and B are accessible, then is accessible by (6.2.1).

We have by , and . Furthermore, if A and B are accessible, we have , therefore, by and by . So, .

A pessimistic perception of X is included in it, but under what conditions is it equal to it (i.e., X is accessible)?

Proposition 6. if then X is accessible.

Proof: Consider that , using (6.2.3), we obtain , thus . So, X is accessible by (6.2.5).

We use this proposition to check if a given set X is accessible by computing and the response is affirmative if this union is equal to X.

Example 3. Table 1 shows that is true for all objects x and observers and 3. Furthermore, the observer 1 perceives objects as they are, whereas the observer 2 confuses objects and . In addition, the observer 3 confuses objects , , and . Now, we want to compute the perception of concepts and, as we have said before, this computation depends on the class of perception functions. The perception functions of observers 2, 3, are pessimistic because , with . Consider the concept Flying objects, which is defined by the set then because . By adding the following two concepts, which are (Animals) and (Flying animals), we want to compare their accessibility according to the perceptions of the three observers 2, and 3. Using property 6, we conclude that X is accessible for observers 2 and 3, Z is accessible only for the observer 2, however, Y is not accessible for observers 2 and 3 (see Table 2).

A pessimistic observer constructs and uses the following algebraic structure

, ∩, ∪, −,

, The dashed lines in Figure 3 connect concepts that are not accessible and cannot be used by pessimistic observers, where their structure is only defined by solid lines (Figure 3 - considers only two sets

A and

B).

Table 3.

Pessimistic Perception: Not all sets are necessarily accessible - example of two cases: (a) both A and B are not accessible, (b) A is accessible but not B

Table 3.

Pessimistic Perception: Not all sets are necessarily accessible - example of two cases: (a) both A and B are not accessible, (b) A is accessible but not B

To what extent is observer i more pessimistic than observer j? To answer this question, we define the structure , where is a binary relation that allows us to compare the pessimism of observers defined by I.

Definition 11 (more pessimistic). Given a perception space , we say that i is more pessimistic than j, denoted , iff .

6.3. Optimistic Perception Function

We now introduce a second perception function of class RR, designed to be optimistic.

Definition 12 (Optimistic Perception).

Given a perception space , an observer , the optimistic perception function, denoted , is defined as follows:

Note that for an optimistic observer, an element x can belong to the perception of X (i.e., ) without being a member of X. The properties of the optimistic perception functions are presented in the following way:

Proposition 7. The following properties hold for optimistic perception functions:

(6.3.1) Intersection: ;

(6.3.2) Union: ;

(6.3.3) Monotony: ;

(6.3.4) Idempotent: .

(6.3.5) Accessibility: ;

For optimistic observers, the perception of the intersection of two sets is not equal to the intersection of their perception textit(6.3.1), and sets are not necessarily accessible textit(6.3.5). In addition, a optimistic perception is not necessarily injective.

Proposition 8. Not all sets are necessarily accessible for optimistic perceptions.

Proof: by (6.3.5).

Proposition 9. accessible, then and are accessible.

Proof:

by , is accessible if both A and B are accessible.

In addition, we have by and by . As A and B are accessible, then . Consequently .

Similarly to pessimistic perception, the accessibility of a set can be determined using the proposition 10. Specifically, we compute and verify whether the result is included in or equal to X. If the computing result is a subset of or equal to X, then X is considered accessible; otherwise, X is deemed inaccessible.

Proposition 10. if then X is accessible.

Proof: we have , by (6.3.2). Considering that , we have and we conclude that X is accessible using (6.3.5).

Example 4. Consider observers 2 and 3 with the following perception functions . The three concepts "Flying objects" (X), "Animals" (Y) and "Flying animals" (Z) are they accessible for each observer (see Table 4)?

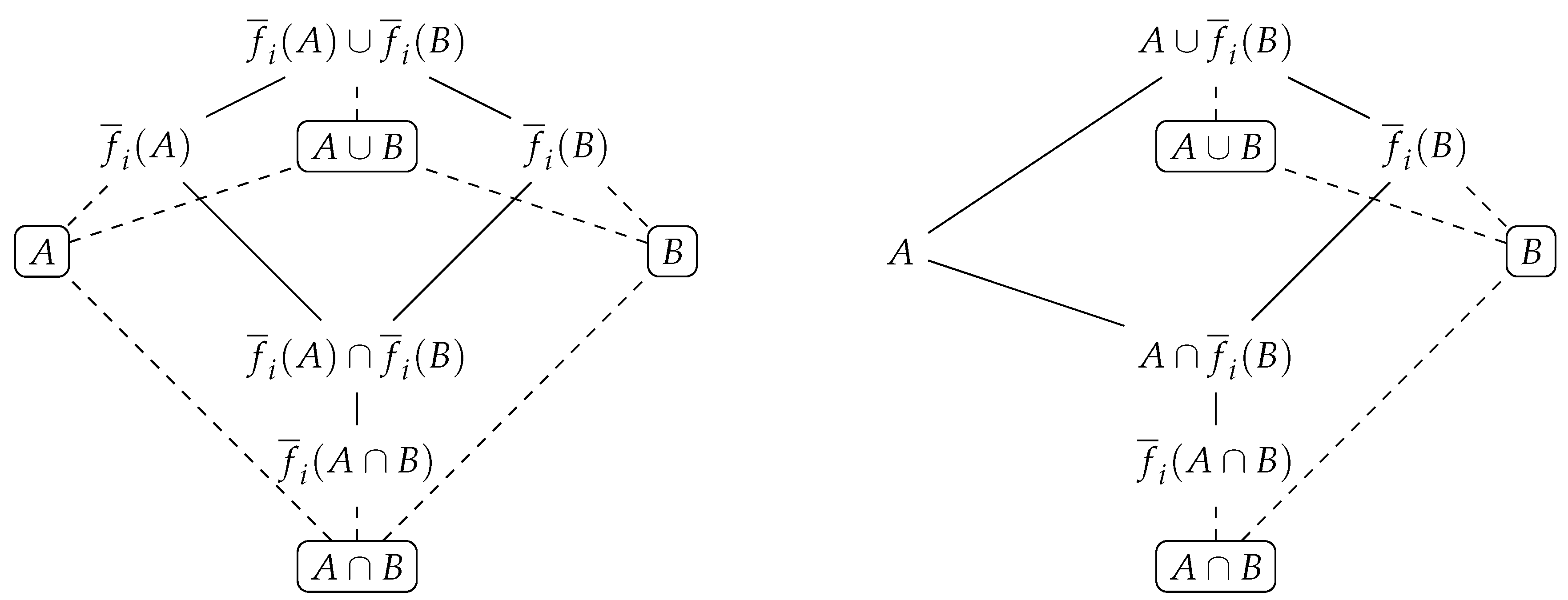

More generally, optimistic perception leads to the algebraic structure , which is based on the power set of the universe U (Table 5 considers only two sets A and B).

In order to compare observers according to their optimistic observers according to perception, we introduce the binary relation .

Definition 13 (more optimistic). Given a perception space , we say that i is more optimistic than j, denoted , iff .

Table 5.

Optimistic Perception: Not all sets are necessarily accessible - (a) both A and B are not accessible, (b) A is accessible but not B

Table 5.

Optimistic Perception: Not all sets are necessarily accessible - (a) both A and B are not accessible, (b) A is accessible but not B

We have introduced the class NR for which all sets are accessible, and next we have defined pessimistic and optimistic perceptions that are representatives of the class RR. Now, we focus on perceptions related to idealism, i.e, class I, where no set is accessible.

6.4. Doubtful Perception Function

Definition 14 (Doubtful Perception).

Given a perception space , an observer , the optimistic perception function, denoted , is defined as follows:

For a doubtful observer, an element x belongs to the perception of X (i.e., ) only if the perception of the object x intersects at the same time X and its complement (i.e., and ). Hence, the perception of the object x is never true.

Proposition 11. The doubtful perception function is not necessarily monotonic.

Proof: Let be a doubtful perception function, , considering and . , resp. have an non empty intersection with both X and , respectively, with Y and , however, even if .

The properties of the Doubtful Perception Functions are:

Proposition 12. The following properties hold for monotonic doubtful perception functions:

(6.4.1) Intersection:

(6.4.2) Union:

(6.4.3) Idempotent:

(6.4.4) Accessibility:

In the reminder part of this paper, we will consider only monotonic doubtful functions assuming axiom.

Axiom:

The structure used by doubtful monotonic observers is deduced from the properties , with the monotony axiom, and drawn in Table 7. Consequently, we cannot compute exactly the perception of concept X, we can only give its lower approximation because , but unfortunately, is not necessarily equal to , see . Thus, we approximate by its lower approximation . Moreover, the perception of an intersection can only be approximated by its upper approximation , see , whereas is only approximated by its lower approximation , see ,

Proposition 13. No set is accessible for doubtful perceptions; i.e. ;

Proof: By .

Example 5. Let us compute the perception of the concept Flying Objects considering observers 1, 2, and 3. The three concepts X (Flying objects), Y (Animals) and Z (Flying animals): How to approximate the perception of concepts X, Y, and Z for the three observers 1, 2, and 3 (see Table 6)?

Similarly, doubtful perception leads also to the algebraic structure

, which is based on the power set of universe U (Figure 5 - considers only two sets A and B).

Table 7.

Monotonic Doubtful Perception: No set is accessible

Table 7.

Monotonic Doubtful Perception: No set is accessible

How much more doubtful is one observer than another? The relation allows for the comparison of two doubtful observers i and j.

Definition 15 (more doubtful). Given a perception space , we say that i is more doubtful than j, denoted , iff .

7. Interpreting Sets Through Perception

For Cantorian sets, the perception is passive, adopting a Boolean approach where an element is a member of a set or not. In this context, the perception function is equal to the identity, i.e, . It corresponds to the Naive Realism (NR) school in epistemology, where we perceive the world as it is, which can be rewritten, in terms of accessibility, as follows: all sets are accessible regarding their observers.

7.1. Zadeh’s Perception of Sets

In classical set theory, the membership function ∈ expresses a connection between an element

x and a set

X, allowing us to know if the element

x is a member of

X or not. This assumes that sets or classes of objects have precisely defined criteria of membership, which is not always the case in the real world. For example, the term "animal" seems straightforward, but, it is actually ambiguous due to differences in biological classification, common language use, and conceptual boundaries. In everyday use, "animal" often refers to vertebrates such as dogs and cats, making it unclear whether things like starfish or jellyfish count. Taxonomy shows a clear definition, but perception varies, leading to confusion in non-experts. Moreover, bacteria are not animals, and despite this, some people might mistakenly group bacteria with animals because both are living organisms that move and consume energy. Also, several concepts are subjective such as "tall people", "fat person", "expensive price", etc. Ambiguity is ignored in the classical set theory even if it arises in the real world. For this reason, Lotfi A. Zadeh introduced fuzzy sets to handle vagueness and ambiguity [

16]. Thus, the membership function is not a function connecting elements of

U to sets, but, each set

X has its own membership function, denoted

, where

is the membership degree of

x to

X. In short, a fuzzy set is a pair

, where

and

, allowing the gradual assessment of the membership of elements in a set:

x is not included in

X iff

, fully included iff

, and partially included otherwise (i.e.,

).

Fuzzy sets can be interpreted in terms of perception considering only one observer that has an imprecise perception function , where and . Hence, objects are perceived as they are, and the perception of X may be imprecise since is a fuzzy set, and consequently all properties of fuzzy sets are inherited.

There are several generalizations of fuzzy sets that extend and complement the original theory in order to deal with more specific problems. For example, Intutionistic fuzzy sets (IFS), introduced by Atanassov [

18], allow us to consider not only imprecision, but also hesitation. To do so, an IFS

has the form

, where the functions

and

define respectively, the degree of membership and degree of non-membership of the element

x to the set

X. These two degrees respect the following constraints:

,

and

. Moreover, these two degrees are aggregated into a single degree

, which is called the hesitation margin or the degree of indeterminacy of

. How to interpret the IFS in terms of perception? Similarly to the interpretation of fuzzy sets, we consider only one intuitionistic observer, which is imprecise and hesitant at the same time. His perception function is

, where

and

. Hence, objects are perceived as they are, and concepts are perceived with imprecision and hesitantation, since

is an intuitionistic fuzzy set and consequently all properties of intuitionistic fuzzy sets are inherited.

Another generalization of fuzzy set is called Hesitant fuzzy set (HFS) [

19], which considers situations where there are some difficulties in determining the membership of an element to a set, caused by a doubt between a few different values. For example, in decision making, experts may have divergent opinions on alternatives due to varying knowledge backgrounds or interests. Since they cannot easily persuade each other, reaching a consensus evaluation can be challenging. However, multiple evaluation values may exist, reflecting the diversity of expert perspectives and the complexity of aggregating judgments in a structured decision-making process. In cases where we have a set of possible values, hesitant fuzzy set (HFS) permits the membership degree of an element to a set presented by several possible values between 0 and 1. Thus, a hesitant fuzzy set

X is defined as follows:

, where

is a set of possible membership degrees of

to the set

X. For example, let

be the universe,

,

,

, and

, which are members degrees of elements

, and

to

X, respectively. So,

X is an HFS like

. Unlike Fuzzy and Intuitionistic fuzzy sets where there is only one observer, which is imprecise and also hesitant, respectively, in the case of hesitant fuzzy sets, there is a set of imprecise observers, denoted

, perceiving the same reality (an element

x, and a set

X), and each one gives a member degree of elements

x to

X. Note that the number of observers depends on the reality they observe. In this context, the hesitant perception function is

, where

and

, where, |

| is the number of observers perceiving the same reality (

x, and

X). In addition, the perception space is

where

. In short, the same reality is perceived by a set of imprecise observers, which may change according to the observed reality, with disagreements among themselves. Moreover, objects are perceived as they are, and concepts are perceived by multiple imprecise observers, since

is a hesitant fuzzy set and consequently all properties of hesitant fuzzy sets are inherited.

Beyond fuzzy, intuitionistic and hesitant sets that we have interpreted in terms of perception, there are several other extensions of fuzzy sets [

20], like type-2 fuzzy set, and fuzzy multiset, etc. However, interpreting all of these sets in terms of perception is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, we continue by interpreting rough sets to show how perception is related to roughness, and better understanding the relationship between rough and fuzzy sets to shed different light.

7.2. Pawlak’s Perception of Sets

The rough set theory (RST), introduced by Zdzisław Pawlak in 1982, is a mathematical framework for dealing with vagueness and uncertainty in data analysis - Book Pawlak [

21]. Unlike classical set theory, which assumes sharp and precise membership, rough sets allow for incomplete or imprecise knowledge by approximating a set using two definable boundaries: a lower approximation and an upper approximation. Rough set theory provides a mathematically rigorous framework for dealing with uncertainty and vagueness, particularly in decision systems, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. It differs from fuzzy set theory by focusing on indiscernibility relations rather than membership degrees. Its ability to perform data reduction, classification, and knowledge discovery makes it a powerful tool in data science and AI applications. Let

U be a universal set (also called the universe of discourse) and let

R be an equivalence relation on

U, called an indisernibility relation as if

x,

and

we say that

x and

y are indistinguishable in

U. This means that

R partitions

U into equivalence classes called granules or information granules. The pair

is called an approximation space. For a given target subset

, we define its rough approximation as follows:

Lower approximation: The lower approximation of X, denoted as , consists of all elements of U that definitely belong to X based on the equivalence relation R: , where is the equivalence class of x under R.

Upper approximation: The upper approximation of X, denoted as , consists of all elements of U that possibly belong to X, meaning that their equivalence class overlaps with X:

Using these two approximations, the boundary region of X is given by the difference between the upper and lower approximations: , representing elements that cannot be definitively classified as belonging to X or not. Hence, the roughness of a set X can be quantified using the accuracy measure: , with . So, if then X is a crisp (classical) set (i.e., its boundary region is empty), whereas, if then X is a rough set, meaning there is uncertainty in classifying some elements of U, i.e., those of the boundary of X, as an element of X or not.

To interpret rough sets in terms of perception, we have to consider the equivalence relation

R, which leads to perception of objects as granules and consequently inherit granular perceptions of objects; see definition 5. In this context, observers do not have direct access to all objects in the universe

U, but perceive them through the relation

R. Hence, the perception of concepts, or sets, is a consequence of the granular perception of objects, which is based on the lower and upper approximation operators. That is why we consider two observers

l and

u, who perceive objects using their relation

and

, respectively. The first observer

l is sure and expresses a necessity, whereas the second observer

u is uncertain and expresses a possibility. Consequently, we define the rough perception function as

, where

and

represent perception functions of the observers

l and

u, respectively. For this rough perception, both observers do not perceive objects as they are because

and

. In fact, objects are observed as granules (i.e.,

,

) because of indiscernibility because both observers cannot separate some objects from each other, even if they are not identical, leading to the perception of granules. In addition, these two observers

l and

u perceive concepts using the functions

and

, respectively. So, a set

X is crisp or accessible, if there is a consensus between these two observers, i.e.,

, and rough otherwise. For more details on the relationship between roughness and accessibility, see [

22], where the author shows that rough sets are

-accessible. Note that

belongs to the pessimistic perception class introduced in

Section 6.2, while

is an optimistic perception function (

Section 6.3).

Many proposals have been made for generalizing rough sets, especially in relation with fuzzy sets, focusing on the indiscernibility relation as granules play a pivotal role in Rough Set Theory (RST). For example,

-RST [

23] has been developed to approximate fuzzy sets using a parameterized indiscernibility relation

based on the classical indiscernibility relation

R, a similarity function

S and a threshold

to control the size of granules:

Then, all basic concepts of rough sets are extended using instead of R. Similarly to rough sets, we also consider two observers, but here and , controlling the size of granules they perceive with a parameter . In addition, the parametrized perception function is , where and . As for rough observers used for rough sets, these two parametrized rough observers also do not perceive objects as they are, but they perceive them at the same level , where and . Moreover, they also perceive concepts at the same level using their perception functions and , respectively.

More generally, rough set theory is particularly useful in machine learning, data mining, pattern recognition, and artificial intelligence, where data often contain incomplete, inconsistent, or noisy information. Several other extensions of rough sets were developed, however, interpreting them in terms of perception is beyond the scope of this paper.

In conclusion, this section elucidates and reinterprets established set theories by situating them within the oSet formalism, which explicitly incorporates the role of observers. This unified perspective facilitates the comparison of different types of sets, regardless of their notational and structural heterogeneity. For instance, in fuzzy sets, elements of the universe are clearly distinguished, but their membership is uncertain. In contrast, rough sets introduce indiscernibility, where some objects cannot be distinguished from others, leading to granular representations. Thus, imprecision in fuzzy sets arises from uncertainty in membership attribution, whereas uncertainty in rough sets results from indistinguishability among elements. Additionally, intuitionistic fuzzy sets simultaneously capture both membership and non-membership uncertainties, explicitly accounting for hesitancy. In contrast, hesitant fuzzy sets primarily represent the diversity of expert opinions rather than any inherent hesitation. This distinction makes hesitant fuzzy sets particularly suitable for multi-expert decision-making, where diverse yet imprecise judgments must be aggregated into a coherent evaluative framework.

Moreover, the oSet framework can serve as a foundation for constructing new set theories, such as Intuitionestic-Hesitant Sets, that integrate multiple imprecise hesitant observers. Formally, let , be a set of representing a hesitation margin or the degree of indeterminacy of . In this case, we consider multiple imprecise and hesitant observers, and consequently, these sets can be viewed as a generalized framework encompassing fuzzy, intuitionistic, and hesitant sets simultaneously.

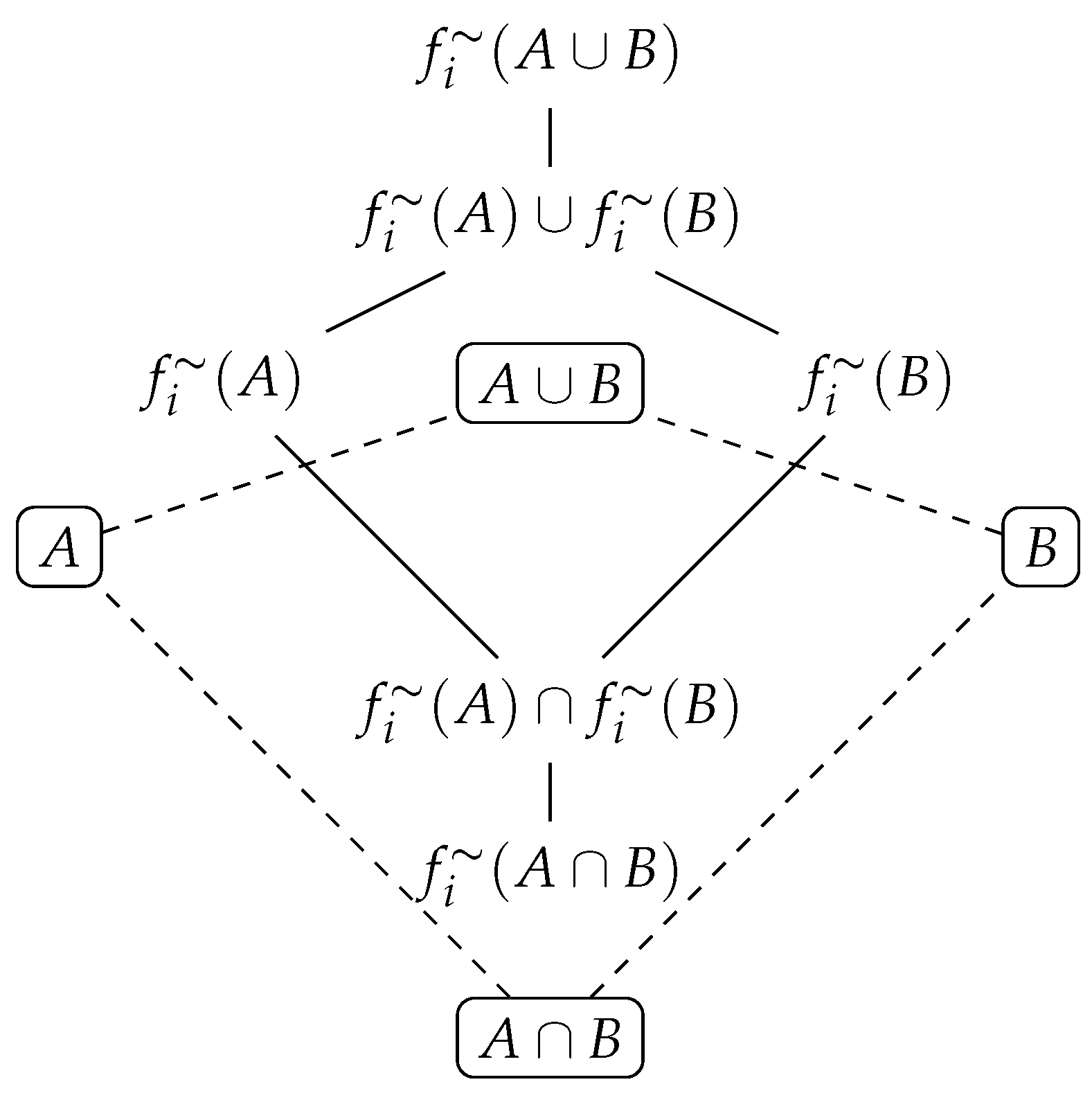

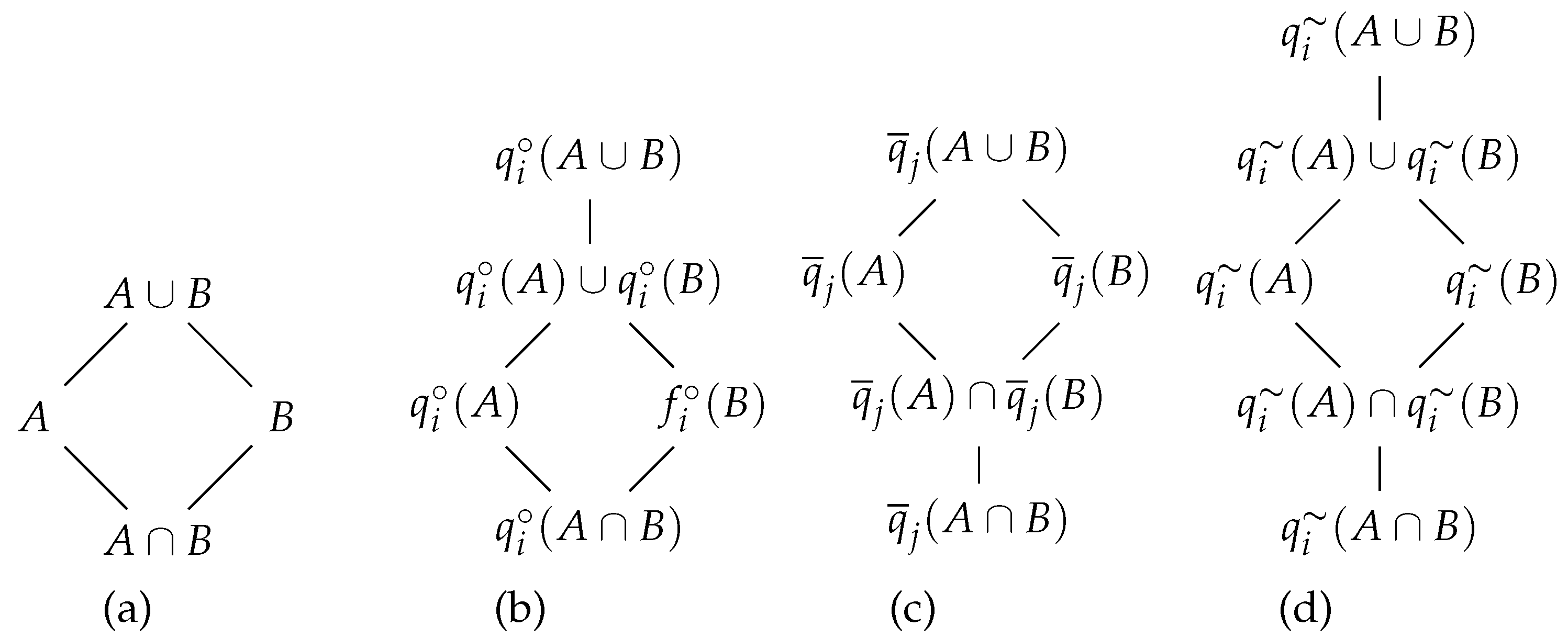

8. Discussion

We have introduced four perception functions, main classes of which are denoted Class NR, Class RR and Class I corresponding, respectively, to Naive Realism, Representative Realism and Idealism well-known schools in epistemology. The accessibility plays a key role in bridging the gap between sets and perceptions, i.e., all sets are accessible for naive perceptions, not all sets are necessarily accessible for optimistic perceptions, whereas no set is accessible for idealists observers. Considering that each observer has his own perception function, one may induce a relationship between sets and observers. More precisely, we have induced the algebraic structure associated with each perception function; see Table 8.

Table 8.

Class NR - Naive (a). Class RR - Pessimistic (b), Optimistic (c), Doubtful (d)

Table 8.

Class NR - Naive (a). Class RR - Pessimistic (b), Optimistic (c), Doubtful (d)

The view of the world that naive observers derive from their perception faithfully represents objects and concepts of the real world assuming a sharp distinction between them and excluding any variability of their perception. Thus, all objects and concepts are perceived as they are; i.e., all sets are accessible. Consequently, all naive observers, living in the same real world, construct the same algebraic structure (Table 8 (a)), which can be used for decision-making and general reasoning. However, the limitations of this naive perception occur when dealing with concepts in the real world, which may be imprecisely defined. In addition to their imprecision, the boundaries of such concepts are unsharp, culminating in the problematic situation, where we can neither confirm with certainty that an element is a member of a set or not.

However, very little attention was given to the mathematical foundations of concepts perception and its variability despite its fundamental importance to human thinking and the social nature of human being. In addition to our perception of the universe through our five senses, our age, education, gender, psychological peculiarities, and past individual experiences determine our perceptions of the world and suggest the nature of our decision and reasoning. Guided by this need, three perception functions of the Class RR are introduced to represent hidden nature of observers like pessimism (Table 8 (b), optimism (Table 8 (c)) or doubt (Table 8 (d).

Instead of considering each perception separately, we present some properties of cross-perception functions:

Proposition 14. The following properties are directly inferred from the definition of perception functions and axioms:

(6.1.1)

(6.1.2)

(6.1.3)

(6.1.4)

(6.1.5)

(6.1.6)

(6.1.7)

(6.1.8)

We remind you that the perception function of the observer i is based on his objects’ perception function , according to a given property . Consequently, we can study other perception functions considering different properties , for example, , which may be among the following properties , , , etc. Moreover, we can extend to also consider the context of observation.

Finally, let us focus on the bridge that we are attempting to build between perception theories developed in epistemology and sets to define oSets, which depend on their observer. In this spirit, we introduced different perception functions, which are discussed in the light of perception theories, mathematical structures, and the notion of accessibility. More precisely, we have considered only naive and representative realism. If we want to define a new perception function representing the idealism school, we need to change the perception space, replacing by , under the constraint , with U representing the real world and is the perception world of the observer i. Alternatively, with the advent of new technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR) headset and artificial intelligence (AI), we can develop new perception functions according to representative realism and transcendental idealism approaches. In fact, imagine wearing a VR headset, the mind does not structure the reality through our mental filters. The observer is living in a virtual and/or augmented reality which evolves dynamically according to the observer behavior and to its context, also.

oSets are particularly useful for computing without consensus, i.e., no unique solution or decision to deal with the different alternatives. They can play a central role in the Human-AI collaboration [

24], because AI systems must account for the diversity of human perceptions as individuals construct their own reality based on experiences, culture, and cognitive biases, even when observing the same objective world. This diversity profoundly impacts reasoning, decision making, and problem solving. AI systems that rigidly impose ranking methods overlook the nuances of human subjectivity, potentially leading to biased or contextually inappropriate decisions. Instead, AI should incorporate perception-aware models, enabling adaptive, context-sensitive collaboration. For example, in medical diagnosis or legal reasoning, diverse expert opinions shape better outcomes than a single ranking approach, promoting inclusion, adaptability, and trust in AI. A hypergraph-based method was introduced to compute shared perceptions with respect to all observers [

13].

9. Concluding Remarks

In computing, particularly in artificial intelligence, acknowledging the variability of human perception is fundamental for designing systems that can adapt to diverse interpretations of reality. Traditional AI models operate under the assumption of an objective and well-defined world, often failing to capture the nuances of human subjectivity. However, future AI systems must go beyond rigid one-size-fits-all approaches to integrate perceptual diversity into their decision-making and modeling processes.

To achieve this, AI must incorporate frameworks that allow observer-dependent representations, accommodating uncertainty, ambiguity, preferences, cultural variability, and contexts. This requires moving from purely data-driven models to hybrid approaches that blend neural computation with symbolic reasoning, enabling AI to process and reason with multiple, sometimes conflicting, perspectives. Such models will be crucial in fields like natural language processing, human-computer interaction, and autonomous decision making, where understanding human intent and perception is vital.

Furthermore, in an increasingly interconnected world, AI systems will not operate in isolation but will coexist and interact with humans in shared environments. Future intelligent systems must be designed to dynamically adapt to human interpretations of reality rather than imposing a singular computational perspective. This calls for the development of perception-aware AI capable of recognizing when different observers interpret the same reality differently and adjusting their responses accordingly.

Ultimately, integrating human perception into AI systems will not only enhance their robustness and fairness, but will also ensure their alignment with human values. As AI becomes embedded in daily life, shaping everything from personalized recommendations to autonomous decision making, its ability to recognize and respect the diversity of human experiences will define its success in creating meaningful and responsible interactions within the globally connected small world.

The oSets framework is designed to align with the complexities of the real world, taking into account the diversity of human perceptions for effective communication, AI development, and decision making in multidisciplinary fields. We also try to open new horizons for interdisciplinary research by building bridges between epistemology and more particularly theories of perception, mathematics starting with set theories, artificial intelligence and computing.

In summary, our vision is for an AI revolution that prioritizes human-centric collaboration. We advocate for AI systems that are not only technically advanced, but also sensitive to the rich diversity of human experiences, ethical standards, and cultural contexts. This approach ensures that AI becomes a powerful tool for positive transformation, enabling a fair, diverse, and respectful interaction between technology and humanity.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| U |

The universe representing the real world |

|

Power set |

|

Complement of set X |

| I |

Set of observers |

| R |

Equivalence relation |

|

Perception space |

| ∧ |

"and" logical operator |

|

Ternary membership relation of the observer i

|

|

multiplicity of an element in a set |

|

fuzzy membership relation |

|

lower approximation membership function |

|

upper approximation membership function |

|

lower approximation of X

|

|

upper approximation of X

|

|

Semantic function |

|

Object’s perception function of the observer i

|

|

Concept’s perception function of the observer i

|

|

Perception function of the observer i

|

|

Perception function of the set of observers in I

|

| NR |

Naive realism |

| RR |

Representative realism |

|

Naive, or Cantorian, perception function |

|

Pessimistic perception function |

|

Optimistic perception function |

|

Doubtful perception function |

|

Zadeh’s perception function |

|

Intuitionistic object’s perception function |

|

Intuitionistic concept’s perception function |

|

Hesitant object’s perception function |

|

Hesitant concept’s perception function |

|

Pawlak’s perception function |

|

Pawlak’s pessimistic perception function |

|

Pawlak’s optimistic perception function |

References

- Serres, Michel. The five senses: A philosophy of mingled bodies. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2008.

- Carey, S., The Origin of Concepts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- A.M. Turing, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, MIND, Vol. LIX, N° 236, pp. 433-460, 1950.

- Audi, Robert, Epistemology: A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge, New York: Routledge, 1998.

- Lewis White Beck, Secondary Quality, The Journal of Philosophy, Volume 43, Issue 22, pp. 599-610, 1946.

- Logue, Heather, Why Naive Realism?, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 112: 211–237, 2012.

- Uzgalis, William L., Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding—A Reader’s Guide, London: Continuum, 2007.

- René Descartes Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy, Hackett Publishing Company, 4th Edition, 1999, 128 pages.

- Allais, L. , Kant’s transcendental idealism and contemporary anti-realism, International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 11: 369–392, 2003.

- Berkeley, George. The works of George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne. Edited by A. A. Luce and T. E. Jessop. 9 volumes. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1948-1957.

- McCarthy, J., Epistemological problems of artificial intelligence. In IJCAI,1038–1044, 1977.

- McCarthy, John, The Philosophy of AI and the AI of Philosophy, Philosophy of Information, 12, pp. 711-740, 2008.

- Mohamed Quafafou, Perception in Human-Computer Symbiosis. HCI International 2020, Springer International Publishing, pp.83-89, 2020.

- Zadeh, Lotfi A. A new direction in AI: Toward a computational theory of perceptions. AI magazine 22, no. 1, 73-73, 2001.

- Russell, An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth, Penguin Books Publisher, Pelican book Series, 1967, 332 p.

- L.A. Zadeh, Fuzzy sets, Information and Control 8, 338–353, 1965.

- Z., Pawlak, Rough Sets, International Journal of Computer and Information Sciences, 11, 341-256, 1982.

- K. Atanassov, Intuitionistic fuzzy sets, Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 20, 87–96, 1986.

- V. Torra, Y. V. Torra, Y. Narukawa, On hesitant fuzzy sets and decision, International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 25, 529–539, 2010.

- Didier Dubois and Henri Prade, The legacy of 50 years of fuzzy sets: A discussion, In Fuzzy Sets and Systems, vol. 281: 21-31 (2015).

- Pawlak, Zdzisław. Rough sets: Theoretical aspects of reasoning about data. Vol. 9. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Mohamed Quafafou, Rough Sets are ε-Accessible. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Rough Sets (IJCRS), Santiago de Chile, Chile, October 7-11, pp.77-86, 2016.

- Mohamed Quafafou, α-RST: a generalization of rough set theory, Information Sciences, 124, 1, 301-316, 2000.

- Mohamed Quafafou, Diversity of Perception in Human-AI Collaboration. 13th International Conference on Human Interaction and Emerging Technologies (IHIET-AI), 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).