1. Introduction

Robo-advisors have emerged as automated investment platforms offering data-driven, customized financial advice at a low cost. By simplifying investment processes, these digital advisors are often seen as tools to democratize financial planning and potentially enhance users’ financial decision-making. However, a notable research gap exists regarding their effectiveness in improving investors’ financial literacy and long-term habits. Despite the promise of making investing more accessible, robo-advisors to date show a limited impact on improving users’ financial knowledge, often merely compensating for knowledge gaps with passive, automated strategies (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025; Eichler, 2024; Luo et al., 2024). This raises concerns about whether increased accessibility and advice through technology truly translate into better-informed investors over time.

Moreover, prior studies indicate that financial literacy alone has weak predictive power on prudent investment behavior; interventions to boost financial knowledge explain only a trivial fraction of the variance in actual financial behaviors (Hu et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2024; Abhijith & Bijulal, 2024). In other words, even when individuals become more financially knowledgeable, it does not necessarily follow that they will adopt systematic investing habits or avoid costly mistakes. One reason for this disconnect lies in the psychological and behavioral biases that can override rational decision-making (Othman, 2024; Panchal & Mohadkar, 2024; Eichler & Schwab, 2024). Investors frequently make choices that defy classical rationality, as emotional and cognitive biases lead them to deviate from optimal financial behavior. These biases—such as overconfidence, loss aversion, or herding—can cause even well-informed individuals to act against their own long-term interests (Rawal et al., 2024; Kumar, 2024; Adji & Karmawan, 2024). Thus, neither robo-advisory technology nor financial education, in isolation, seems sufficient to ensure disciplined investing, highlighting a clear gap in the literature at the intersection of fintech, financial literacy, and investor behavior.

This study contributes to understanding the weak correlation between financial literacy and investment behavior. By examining how investors interact with robo-advisors and tracking their subsequent investing patterns, we shed light on why heightened financial knowledge does not automatically translate into consistent, rational investment decisions. The analysis reveals nuances in how educated investors may still falter in practice, reinforcing findings that mere knowledge gains often fail to produce stronger financial habits (Kesharwani et al., 2024; Banerjee, 2025; Eichler & Schwab, 2024). Our work extends the literature by pinpointing factors that mediate the knowledge–behavior gap, such as inertia in investment routines and sensitivity to market fluctuations, thereby explaining the limited predictive power of financial literacy on systematic investment habits (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025; Luo et al., 2024).

The study emphasizes the need to integrate behavioral reinforcement mechanisms into robo-advisory platforms. We argue and demonstrate that embedding principles from behavioral finance into robo-advisors can enhance their effectiveness in shaping user behavior. In particular, features like personalized reminders, default options, and timely feedback can align the robo-advisor’s guidance with the way real investors behave under uncertainty (Luo et al., 2024; Eichler & Schwab, 2024; Kesharwani et al., 2024). Recent research suggests that incorporating behavioral nudges and psychological insights could enhance the predictive power of robo-advisors in guiding investor decisions (Othman, 2024; Adji & Karmawan, 2024; Eichler, 2024). By moving beyond a purely rational, one-size-fits-all approach, robo-advisory services can account for individual behavioral tendencies—for example, counteracting an investor’s loss aversion with reassuring messages during market dips, or curbing overconfidence by tracking and gently exposing prediction errors (Panchal & Mohadkar, 2024; Eichler & Schwab, 2024). This contribution addresses the call for robo-advisors to not just provide algorithmic advice but also to function as a behavioral coach that helps investors stick to rational plans in the face of biases (Banerjee, 2025; Luo et al., 2024).

Our study proposes innovative solutions to actively bridge the gap between financial knowledge and investment action. We outline a design for robo-advisory platforms that includes interactive learning modules, scenario-based simulations, and real-time nudges as core components. Unlike traditional robo-advisors that rely on passive portfolio management and do not actively engage users in the learning process, the proposed platform would involve users in an educational dialogue (Ablazov et al., 2024; Kesharwani et al., 2024). For instance, interactive modules can periodically teach or quiz investors on key concepts tailored to their portfolio, reinforcing their understanding in context. Scenario-based simulations would present users with lifelike financial situations such as a sudden market downturn or a windfall and prompt them to make decisions in a risk-free environment, thereby converting abstract knowledge into practical skills (Othman, 2024; Eichler, 2024; Panchal & Mohadkar, 2024). Additionally, real-time nudges and alerts are suggested to guide users at critical decision points: the platform might remind a user to rebalance a portfolio, encourage increasing a monthly investment after a salary raise, or caution against panic-selling during volatility (Luo et al., 2024; Eichler & Schwab, 2024). Such features are designed to create a feedback-rich experience where learning and doing reinforce each other. By introducing these interactive and behaviorally informed elements, this work contributes a novel framework for robo-advisors that could cultivate disciplined investing habits while simultaneously enhancing financial literacy (Banerjee, 2025; Chandani & Bhatia, 2025; Adji & Karmawan, 2024).

Our findings confirm that improvements in financial literacy alone do not guarantee better investment habits. Even when users gain knowledge or receive educational content, in the absence of behavioral reinforcements their investing behavior may remain unchanged or susceptible to impulsive tendencies (Eichler & Schwab, 2024; Luo et al., 2024). This underscores that bridging the knowledge-action gap requires more than information—it requires habit-forming interventions. We suggest that robo-advisory platforms evolve to incorporate features for ongoing engagement and behavior reinforcement. In practice, this means providing investors with personalized notifications, performance tracking, and other nudges to encourage consistent behavior (Rawal et al., 2024; Kesharwani et al., 2024). For example, timely notifications can be used to nudge users toward beneficial actions, such as setting up automatic monthly investments or increasing their savings rate, helping to transform good intentions into routine practices (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025; Panchal & Mohadkar, 2024). Similarly, performance-tracking dashboards with progress indicators can keep users focused on long-term goals; celebrating milestones fosters a sense of accomplishment and commitment (Hu et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2024). Incorporating such real-time feedback and positive reinforcement mechanisms would enable robo-advisors to act as a bridge between financial knowledge and disciplined investing behavior.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Literature review and Hypotheses Development 2. Materials and Methods 3. Results & Discussions 4. Conclusions and Recommendations 5. References.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Financial Literacy and Investment Behavior

The emergence of robo-advisors has transformed the financial advisory sector by offering algorithm-driven investment recommendations tailored to investors with diverse levels of financial knowledge. Their impact on financial literacy and investment decision-making has attracted significant academic attention, particularly regarding their ability to enhance financial knowledge, reduce behavioral biases, and shape investor behavior.

One of the primary benefits of robo-advisors is their role in enhancing financial literacy, particularly among retail investors with limited prior experience. Kamarudin et al. (2024) argue that these platforms provide structured financial education through personalized investment guidance, risk assessment models, and performance tracking. Investors using robo-advisors gradually become more familiar with financial concepts, particularly those related to asset allocation, portfolio diversification, and risk tolerance (Kamarudin et al., 2024). Similarly, Panchal and Mohadkar (2024) examined how financial technology enhances financial education, showing that automated advisory services help investors learn and apply financial concepts but do not necessarily lead to deep learning (Panchal & Mohadkar, 2024).

However, not all studies agree that robo-advisors contribute to long-term financial literacy improvements. Eichler and Schwab (2024) suggest that while these platforms expose users to financial decision-making, they may not necessarily encourage independent financial analysis. Their study found that individuals with higher financial literacy often use robo-advisors as a supplementary tool, while those with limited knowledge tend to follow automated recommendations without critically assessing them (Eichler & Schwab, 2024).

H1: Robo-advisors enhance financial literacy by increasing financial awareness and investment knowledge.

2.2. Financial Literacy and Dependence on Robo-Advisors

Some research suggests that financially literate individuals make more independent financial decisions and are less likely to rely on automated guidance (Namyslo & Jung, 2024). However, others argue that financially knowledgeable investors still find value in robo-advisors due to their ability to process large amounts of data and provide objective investment recommendations (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025).

For example, Luo et al. (2024) examined how investors with different levels of financial literacy interact with robo-advisors. Their findings suggest that individuals with low financial literacy often follow automated recommendations without second-guessing them, while more knowledgeable investors use robo-advisors as decision-support tools rather than as a primary source of guidance (Luo et al., 2024). This aligns with the findings of Chandani & Bhatia (2025), who argue that robo-advisors create an illusion of objectivity, where investors assume the recommendations are optimal without considering external market conditions (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025).

H2: Financially literate individuals are less dependent on robo-advisors for decision-making.

2.3. Behavioral Biases in Investment Decision-Making

Despite the availability of algorithm-driven investment strategies, investor behavior continues to be influenced by psychological and cognitive biases. Research in behavioral finance suggests that individuals frequently make investment decisions based on emotions rather than rational analysis (Rawal et al., 2024).

Othman (2024) explores the role of psychological biases in investment outcomes, finding that even with access to rational, data-driven advice, investors often override robo-advisor recommendations due to emotional biases such as overconfidence and loss aversion (Othman, 2024). Namyslo and Jung (2024) further analyze how investors interact with robo-advisors, showing that while algorithmic advisory services reduce certain irrational behaviors, they do not entirely eliminate them. Instead, investors with higher financial literacy are more likely to modify algorithmic recommendations, whereas those with lower financial knowledge trust the automated system without second-guessing it (Namyslo & Jung, 2024).

H3: Behavioral biases, such as overconfidence and loss aversion, influence investment decisions even when using robo-advisors.

2.4. Trust and Adoption of Robo-Advisors

Trust in technology is a critical determinant of robo-advisor adoption. Studies indicate that trust in AI-driven financial services significantly affects investor willingness to use robo-advisors (Nain & Rajan, 2024).

For instance, Kumari et al. (2024) analyzed consumer behavior in financial markets and found that investors exhibit varying levels of trust in robo-advisors based on their demographic characteristics, income levels, and financial experience. Their research suggests that younger investors, particularly Millennials and Gen Z, demonstrate higher confidence in automated financial solutions, whereas older investors are more likely to prefer human advisors for complex investment decisions (Kumari et al., 2024).

Similarly, Chandani and Bhatia (2025) found that trust in robo-advisors correlates with transparency in investment decision-making. Their study suggests that investors who trust the accuracy of algorithmic recommendations are more likely to adopt robo-advisors as a long-term investment tool (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025).

H4: Trust in robo-advisors positively influences adoption rates.

2.5. Demographic Differences in Robo-Advisory Effectiveness

Several studies have explored demographic differences in the effectiveness of robo-advisors. Othman (2024) suggests that younger investors are more comfortable relying on digital advisory tools, whereas older investors often lack confidence in technology-driven financial planning.

Furthermore, Chandani and Bhatia (2025) found that individuals with lower income levels are more likely to depend on robo-advisors due to cost advantages, while high-net-worth individuals prefer hybrid advisory models combining human expertise with AI-driven recommendations (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025).

These findings align with the research of Luo et al. (2024), who found that investor preferences vary based on financial literacy levels. Their study indicates that novice investors rely more on automation, while advanced investors tend to critically assess algorithmic strategies before implementing them (Luo et al., 2024).

H5: The effectiveness of Robo-advisors varies significantly based on age, income, and investment experience.

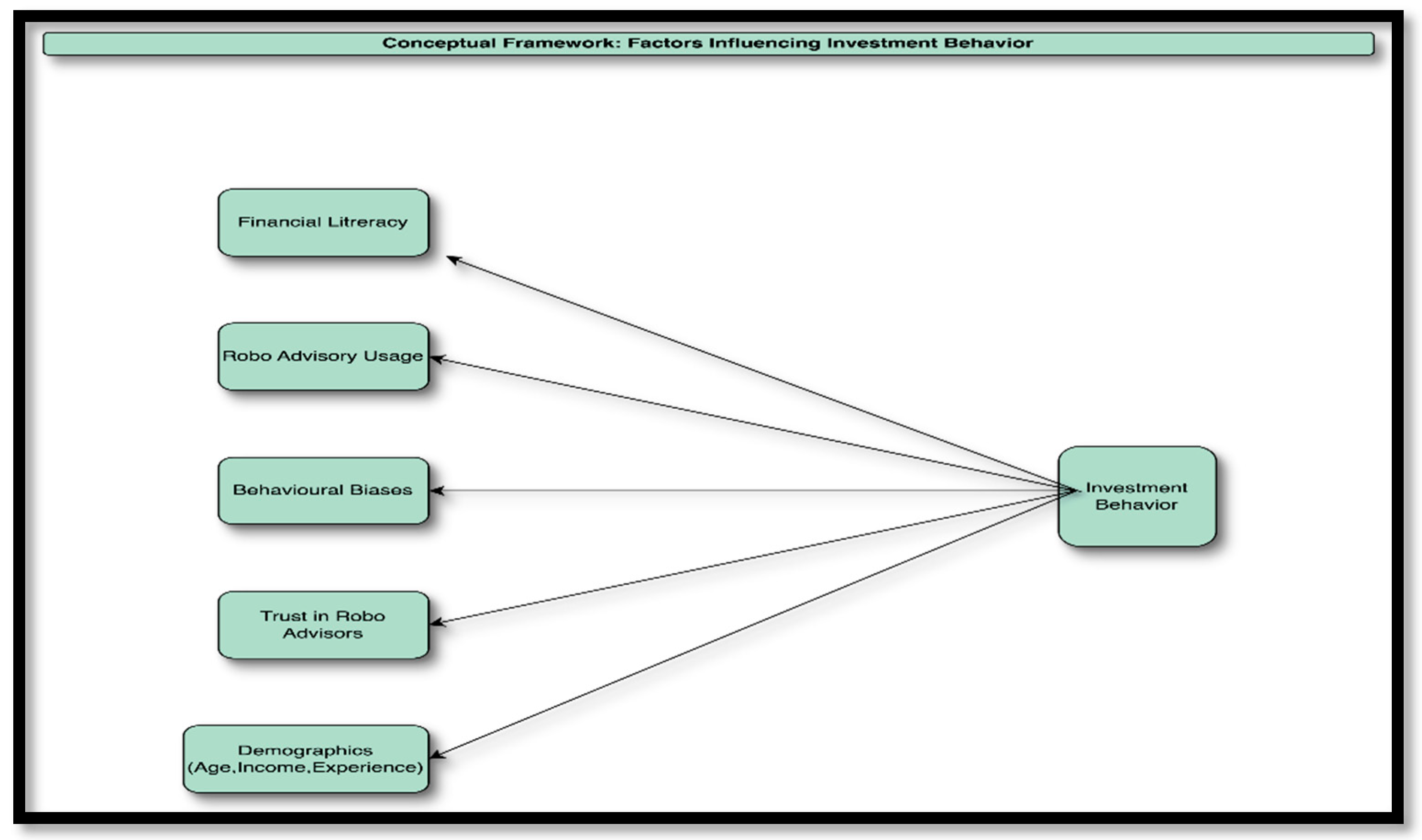

Based on the reviewed literature and existing behavioral finance theories, we propose a conceptual framework that links financial literacy, robo-advisory usage, behavioral biases, trust in technology, and demographic variables to investment behavior. The relationships among these variables are illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a quantitative descriptive-correlational research design to examine the relationship between financial literacy, robo-advisor usage, behavioral biases, trust in technology, and demographic factors on investment behavior among retail investors in the United Arab Emirates. The design was appropriate for investigating non-experimental relationships in a natural, real-world context, allowing the researchers to identify trends without manipulating variables.

Data were collected through a structured, self-administered online questionnaire distributed via social media platforms, investment groups, and professional networks. The final sample comprised 150 valid responses. A purposive sampling method was used to target individuals with at least basic exposure to investment platforms, ensuring relevance to the research context.

The survey instrument consisted of multiple sections: demographic questions (age, income, investment experience), Likert-scale items measuring financial literacy, behavioral biases (e.g., overconfidence, herding, loss aversion), trust in robo-advisory services, frequency of robo-advisor usage, and systematic investment behavior. Each construct was assessed through multiple items adapted from prior validated studies. Items were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

To ensure internal consistency of the measurement scales, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were computed, with all values exceeding 0.75, indicating acceptable reliability. The data were analyzed using SPSS v27. Descriptive statistics were generated to summarize key variables, followed by Spearman’s rank-order correlation to explore relationships, chosen due to the ordinal nature of Likert-scale responses and to avoid normality assumptions.

A simple linear regression was then conducted to evaluate the influence of financial literacy and robo-advisor usage on investment behavior. Regression coefficients, standard errors, and p-values were reported, with statistical significance determined at the 0.05 level. Results were interpreted in relation to the proposed hypotheses. Finally, thematic coding was applied to open-ended responses to support quantitative findings, capturing qualitative insights on investor perceptions of robo-advisors. (

Table 1).

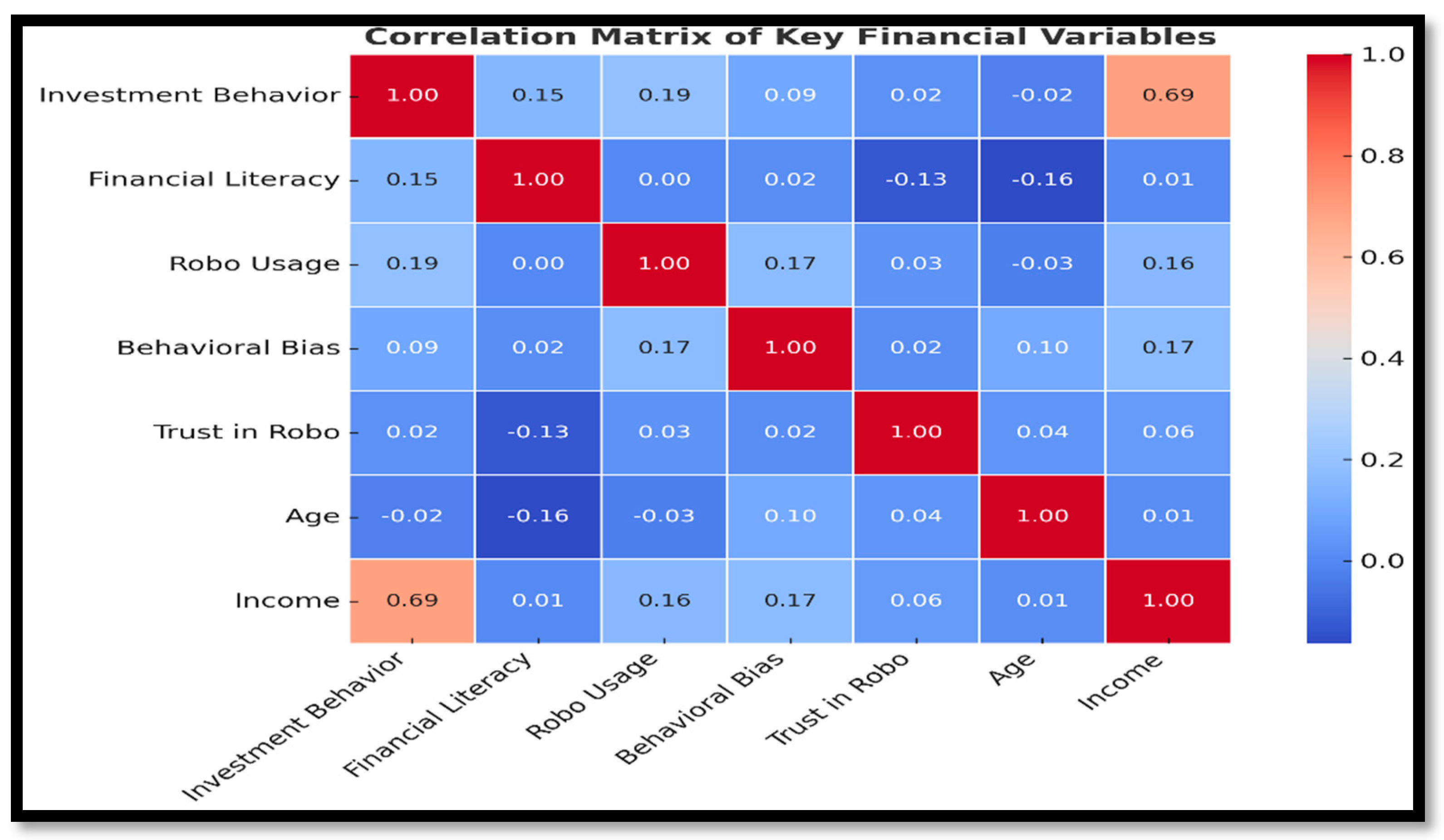

To assess associations among variables, Spearman’s rank-order correlation was employed, chosen due to the ordinal nature of the data and to avoid assumptions of normality. The correlation matrix (

Table 2) highlighted a moderate positive association between financial literacy and investment behavior (ρ = 0.15), and a notably strong correlation between income and investment behavior (ρ = 0.68).

These patterns are further visualized in the heatmap (

Figure 1), illustrating inter-variable strengths and directions, reinforcing that demographic and cognitive factors such as income and knowledge play a more direct role in shaping disciplined investment patterns than mere platform usage.

Figure 2.

Spearman Correlation Heatmap.

Figure 2.

Spearman Correlation Heatmap.

To evaluate predictive relationships, a simple linear regression model was estimated with investment behavior as the dependent variable and financial literacy and robo-advisor usage as independent variables. The results (

Table 3) showed that financial literacy had a statistically significant positive effect on investment behavior (B = 0.273, p = 0.002), while robo-advisor usage exhibited no significant influence (B = 0.770, p = 0.172), suggesting that knowledge enhancement may be more impactful than automation alone in driving rational investment practices.

In addition to the statistical assessment, qualitative responses were collected via open-ended survey items and analyzed thematically using a hybrid inductive–deductive coding approach. Recurring themes included users' perceived lack of human interaction, their trust (or mistrust) in algorithmic recommendations, and appreciation of simplicity in robo-platforms. These qualitative insights contextualize the regression findings, revealing that while robo-advisors offer efficiency, their effectiveness in behavior change may be contingent on personalized reinforcement and perceived user control. The integration of statistical and thematic data enables a more nuanced understanding of how technology, cognition, and behavior interact in contemporary investment decision-making.

4. Results & Discussions

The results offer critical insights into the relationships between financial literacy, robo-advisor usage, and systematic investment behavior. Descriptive analysis indicated considerable variation across key constructs, with the financial literacy and investment behavior variables exhibiting sufficient distribution to justify regression modeling (

Table 1). The correlation analysis using Spearman’s rank-order coefficients revealed meaningful associations. Financial literacy demonstrated a positive but modest correlation with investment behavior (ρ = 0.15), while income showed a stronger, more robust association (ρ = 0.68), suggesting that while knowledge is a factor in promoting disciplined investing, socioeconomic status remains a dominant driver (

Table 2). These findings align with prior research suggesting that access to financial resources and structural stability are significant predictors of sound investment behavior (Kesharwani et al., 2024; Eichler & Schwab, 2024).

The regression analysis further clarified the predictive relationships. Financial literacy was found to be a statistically significant predictor of investment behavior (B = 0.273, p = 0.002), supporting H1 that increased awareness and understanding of financial concepts are associated with more systematic and rational investment decisions (Luo et al., 2024; Kamarudin et al., 2024). However, contrary to expectations under H4, robo-advisor usage did not exhibit a statistically significant effect on behavior (p = 0.172), indicating that the presence of automated advice alone does not necessarily translate into better financial habits. This finding reinforces earlier claims that fintech platforms, although designed to democratize financial decision-making, often lack mechanisms for behavioral reinforcement and engagement (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025; Eichler, 2024). Simply offering access to automated tools does not ensure that users adopt or retain disciplined financial habits—especially in the absence of contextual education and motivational nudges (Banerjee, 2025; Luo et al., 2024).

Visual inspection of the correlation heatmap (

Figure 1) supports these findings by showing the comparative strength of associations among the study variables. The strongest observed linkage remains between income and investment behavior, followed by a more modest but positive correlation between financial literacy and behavior, and weaker associations with robo-advisor usage and behavioral bias. These results reinforce previous findings that financial literacy, while beneficial, accounts for only a small portion of behavioral variance, with emotional and contextual factors often overriding rational intentions (Hu et al., 2024; Othman, 2024; Adji & Karmawan, 2024).

Qualitative findings complemented the statistical results. Respondents frequently mentioned the “lack of human interaction” as a drawback in robo-advisory platforms, aligning with studies that highlight user hesitancy to trust impersonal systems, especially in times of market uncertainty (Namyslo & Jung, 2024; Eichler & Schwab, 2024). Others appreciated the “ease of use” and “efficiency” provided by these platforms for routine tasks, reflecting prior observations that robo-advisors perform well in task automation but less so in adaptive behavior change (Panchal & Mohadkar, 2024). The theme of “trust in automation” appeared to be divided by age and experience, supporting findings that digitally fluent investors are more likely to accept robo-advisory guidance, while others prefer human interaction in higher-stakes scenarios (Kumari et al., 2024; Othman, 2024).

Overall, the findings support the notion that financial literacy enhances investment behavior more consistently than technological adoption. Robo-advisors, when not paired with behavioral design features such as real-time feedback, educational prompts, or interactive modules, appear limited in transforming investor conduct (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025; Luo et al., 2024). This study reinforces growing calls in the literature to embed behavioral nudges into digital advisory tools—such as reminders, simulated scenarios, or goal-tracking dashboards—to bridge the gap between knowing and doing (Eichler, 2024; Rawal et al., 2024; Banerjee, 2025). Merely providing access to algorithmic recommendations does not ensure financial discipline unless the tools are cognitively and behaviorally aligned with user tendencies.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study set out to examine the extent to which robo-advisors influence financial literacy and investment behavior among retail investors, while accounting for behavioral biases and demographic moderators. Through a mixed analytical approach combining quantitative modeling with qualitative thematic insights, the research offers several key takeaways.

First, the empirical findings affirm that financial literacy has a significant and positive impact on systematic investment behavior, reinforcing previous claims that knowledge remains a foundational component of rational financial decision-making (Luo et al., 2024; Kamarudin et al., 2024). However, the relatively low correlation coefficient and limited explanatory power suggest that knowledge alone is not a panacea. This supports prior studies which note that improving financial literacy is necessary but insufficient for cultivating disciplined behavior in isolation (Hu et al., 2024; Eichler & Schwab, 2024).

Second, the results indicate that robo-advisor usage, while popular, does not directly enhance investment discipline. Despite their accessibility and low-cost features, these platforms appear to function more as passive allocation tools than as agents of behavioral transformation. This aligns with research suggesting that automation often replaces, rather than reinforces, financial engagement, especially for users with limited financial acumen (Chandani & Bhatia, 2025; Eichler, 2024).

Third, the strong correlation between income and investment behavior highlights the structural dimensions of financial planning. Even with adequate knowledge or digital tools, limited financial capacity may constrain behavioral outcomes. As such, interventions aimed at improving investment behavior must not only target cognition but also account for economic realities.

In terms of user psychology, qualitative responses emphasized a divergence in trust toward automation. While younger, tech-savvy investors appreciated the efficiency of robo-advisors, others were deterred by the lack of human interaction or contextual advice. These findings suggest that trust and usability are mediated by user profiles, and that one-size-fits-all automation may limit broader adoption or impact.

Based on these insights, several recommendations emerge. First, robo-advisory platforms should integrate behavioral reinforcement mechanisms—such as personalized nudges, feedback loops, scenario-based simulations, and milestone tracking—to convert knowledge into consistent action. Such design interventions have the potential to reduce cognitive overload, counteract biases, and close the knowledge-action gap (Banerjee, 2025; Rawal et al., 2024).

Second, hybrid advisory models may offer a more effective approach, particularly for segments that value human engagement or face complex decision environments. Pairing algorithmic efficiency with occasional human touch points could foster both trust and personalization.

Third, financial literacy programs must be context-aware and actionable. Rather than focusing solely on abstract knowledge, curricula should be embedded into real-time platforms where users can apply insights through interactive features.

Finally, policymakers and fintech developers should recognize that accessibility is not equivalent to empowerment. True investor empowerment arises when information, motivation, and capacity are aligned—an outcome that requires intentional behavioral design and inclusive technology strategies.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the growing literature at the intersection of fintech, behavioral economics, and financial education by illuminating the nuanced dynamics between knowledge, tools, and action. It underscores that technology, when intelligently designed and contextually deployed, can serve as more than an advisor—it can become a behavioral ally.

References

- Abhijith, R.; Bijulal, D. Artificial intelligence in fintech: Behavioural factors influencing robo-advisor adoption. AIMS Int. J. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Adji, Y.B.; Karmawan, I.G.M. Analysis of the robo-advisor investment applications on investor satisfaction using modified UTAUT. IEEE Trans. Technol. Finance 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. Portfolio management with the help of AI: What drives retail Indian investors to robo-advisors? Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandani, A.; Bhatia, A. Are robo-advisors robbing financial advisors? A systematic literature review paper. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, K.S. Automation meets behavior: Challenges of robo-advisors in enhancing financial literacy. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 41, 101105. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, K.S.; Schwab, E. Evaluating robo-advisors through behavioral finance: A critical review of technology potential, rationality, and investor expectations. Front. Behav. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Luo, H.; Liu, X.; Lv, X. Investors' willingness to use robo-advisors: Extrapolating influencing factors based on the fiduciary duty of investment advisors. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, F.; Smith, J.; Ali, Z. The effectiveness of fintech in enhancing financial literacy: A behavioral perspective. J. Bank. Finance 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kesharwani, S.; Prakash, A.; Gangwar, J.D. Robo-advisors: Automated algorithm-driven wealth management services—A literature review. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, I. Implications of market structure on the financial advisory industry. ProQuest Diss. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y. Analysis of behavioral biases in robo-advisory decision making. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nain, I.; Rajan, S. A scoping review on the factors affecting the adoption of robo-advisors. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubice 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Namyslo, N.; Jung, D. Designing a robo-advisor for group decision-making to support enterprise financial planning. Res. Gate 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, N. Emotional economics: The role of psychological biases in personal investment outcomes. SSRN Work. Pap. Ser. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S.; Mohadkar, A.D. Transforming money management: Analyzing the impact of technology on personal finance. SSRN Work. Pap. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, A.; Saroha, J.; Gopalkrishnan, S. Robo advisors revolution: Transforming the landscape of mutual fund investments. IEEE Symp. Bank. Finance 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Iqbal, N.; Sharma, R. Generational differences in trust toward automated financial services. J. Financ. Techno. 2024, 6, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).