1. Introduction

The Sleep is essential for athletes in terms of recovery, immunity and performance (Walsh et al., 2021). An increasing body of evidence highlights the sleep requirements of athletic populations. (Biggins et al., 2019; Charest & Grandner, 2024; Halson, 2014; Leeder et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2021) with research investigating the interaction between nutrition and sleep in athletes being increasingly investigated in recent years (Charest & Grandner, 2024; Doherty et al., 2019; Doherty, Madigan, Warrington, et al., 2023; Gratwicke et al., 2021; Halson, 2014; Moss et al., 2022). The sleep of support staff working in sporting environments has received less attention (Calleja-González et al., 2021; Curtis et al., 2024; Miles et al., 2019a; Pilkington et al., 2022) and requires further investigation.

The human sleep cycle consists of two phases: rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, with NREM further divided into three stages (N1–N3) (Patel et al., 2024). The body typically cycles through these stages 4–6 times nightly, with each cycle lasting approximately 90 minutes (Halson, 2014; Patel et al., 2024). N1, the lightest sleep stage, features theta waves, while N2, the most common stage, includes sleep spindles and K-complexes, which aid memory consolidation. N3, or slow-wave sleep, is the deepest stage, crucial for physical repair and immune function (Hirshkowitz, 2004). REM sleep, accounting for 25% of total sleep, is characterized by vivid dreaming, muscle atonia (except for the diaphragm and eye muscles), and increased brain activity resembling wakefulness (Patel et al., 2024). Sleep is regulated by the circadian rhythm, controlled by the suprachiasmatic nuclei, which influence hormone release, including melatonin and norepinephrine (Patel et al., 2024). Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) plays a key role in sleep induction by inhibiting wake-promoting brain regions through GABA-A receptor activation (Carskadon & Dement, 2005; Patel et al., 2024). See Table 1 for the description of sleep stages.

Table 1.

Sleep Stages, Characteristics and Functions.

Table 1.

Sleep Stages, Characteristics and Functions.

| Sleep Stage |

Characteristics |

Functions |

| NREM Sleep |

|

|

| N1 (Light Sleep) |

Theta waves |

Transition from wakefulness to sleep |

| N2 (Most Common Stage) |

Sleep spindles, K-complexes |

Memory consolidation |

| N3 (Slow-Wave Sleep) |

Deepest sleep, slow-wave activity |

Physical repair, immune function |

| REM Sleep |

Vivid dreaming, muscle atonia (except diaphragm and eyes), increased brain activity |

Cognitive processing, emotional regulation |

| Sleep Cycle |

4–6 cycles per night, ~90 minutes each |

Regulates sleep architecture |

(Adapted from; Halson, 2014; Hirshkowitz, 2004; Patel et al., 2024)

While the essentiality of sleep is clear, a complete understanding of its function remains elusive. Based on our current understanding of sleep, restoration or recovery may be considered a primary function that is paramount for athletes, along with immunity and both mental and physical health (Hirshkowitz, 2004; Patel et al., 2024). However, the physiological functions of sleep are the subject of much research. The current hypotheses as to the function of sleep include neural maturation, facilitation of learning or memory, targeted erasure of synapses to "forget" unimportant information that might clutter the synaptic network, cognition, clearance of metabolic waste products generated by neural activity in the awake brain and conservation of metabolic energy (Hirshkowitz, 2004; Patel et al., 2024).

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) and Sleep Research Society (SRS) recommend that the average adult should sleep 7 or more hours per night on a regular basis to promote optimal health (Watson et al., 2015). The National Sleep Foundation (NSF) concurs with the recommendation of 7 to 9 hours of sleep for adults and 7 to 8 hours of sleep for older adults (Watson et al., 2015). Individual needs vary but consistently sleeping less than 7 hours negatively impacts immunity, the endocrine system, cognitive function, cardiovascular disease risk, and mild cognitive impairments (Watson et al., 2015). Short sleep duration (<7 hours) is associated with coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, as well as increased risk of CHD mortality (Cappuccio et al., 2011). Recent research on sleep health and circadian science highlighted the role of sleep as an additional contributing factor to weight gain and obesity (Kline et al., 2021). Chronically sleeping more than 9 hours per night may indicate sleep apnea, chronic fatigue syndrome and depressive symptoms. Both short and long sleep durations are associated with a greater risk of developing or dying from CHD, stroke and cardiovascular disease (Cappuccio et al., 2011).

Sleep is considered the most effective recovery strategy for athletes (Juliff et al., 2018) yet most sleep research involves non-athletic populations. There is a lack of subjective assessments, objective data and nutrition interventions trials on the sleep of elite athletes and support staff (Walsh et al., 2021). Elite soccer players, due to high travel demands, often experience reduced total sleep time (TST), total time in bed (TTB), and poor sleep quality after late-night games (Lastella et al., 2019; Nédélec et al., 2015). It is also indicated that the quality of sleep in elite athletes can degrade the night after and night of a game or competition (Charest & Grandner, 2024), which applies to a range of team and individual sports abiding to television and competition schedules. Notwithstanding the timing of competition; nerves, adrenaline, caffeine and a high arousal can also detrimentally affect sleep and as a result, performance and recovery (Charest & Grandner, 2024; Lastella et al., 2019).

From a performance perspective, poor sleep impacts concentration levels, reaction time, energy levels during competition, hormonal balance and injury risk (Charest & Grandner, 2024). Chronic poor sleep can impair muscle growth and repair by impairing the release of growth hormone, increased inflammation, glycogen restoration, psychological well-being and moderating hormone balance, particularly cortisol and testosterone (Charest & Grandner, 2024; Lastella et al., 2019). In line with these performance decrements, sleep efficiency (SE) and TST are negatively impacted during periods of intense training (Killer et al., 2017). Poor sleep quality is of particular concern for elite athletes as it can result in a reduction in recovery and/or subsequent athletic performance (Juliff et al., 2018; Leeder et al., 2012). Longer sleep durations correlated positively with finishing place in a multiday netball competition (Juliff et al., 2018) where sleep was objectively evaluated in 42 netball players during a tournament, finding that higher-ranked teams slept longer, had greater TTB, and reported better subjective sleep ratings. Similarly, Leeder et al., (2012) investigated sleep in Olympic athletes (n = 47) using actigraphy, finding poorer sleep characteristics than in non-athletic controls (n = 20), with males exhibiting poorer outcomes than females. Despite poorer sleep markers, athletes remained within the healthy sleep range.

The measurement of sleep quality in athletes indicate that athletes may have a longer TTB, but a lower SE compared to non-athletes (Leeder et al., 2012). This results in a similar TST. Sleep disturbances can occur before important competitions due to reasons like nervousness and alternative surroundings, as well as during normal training due to poor sleep habits, early training times and worrying related to performance (Halson, 2014). Therefore, Walsh et al., (2021) recommend that individual approaches should be taken for sleep recommendations in athletes. Sargent et al., (2021) report that elite ath letes self-assess their sleep need at 8.3 ± 0.9 hours nightly but often obtain only 6.7 ± 0.8 hours. Only 3% of these athletes meet their self-assessed needs, with 71% falling short by an hour or more. Optimal sleep times are generally between 22:00 and 22:30 hours for sleep onset latency (SOL) and 09:00 and 09:30 hours for waking. Team sport athletes (6.9 h) generally sleep more than individual sport athletes (6.4 h), and female athletes have earlier SOL times than males. Sargent et al., (2021) define insufficient sleep as regularly failing to meet sleep needs. It is hypothesized that elite athletes require the upper end of the general population recommendations due to physiological and psychological requirements for recovery so 8 – 9 hrs per night is recommended.

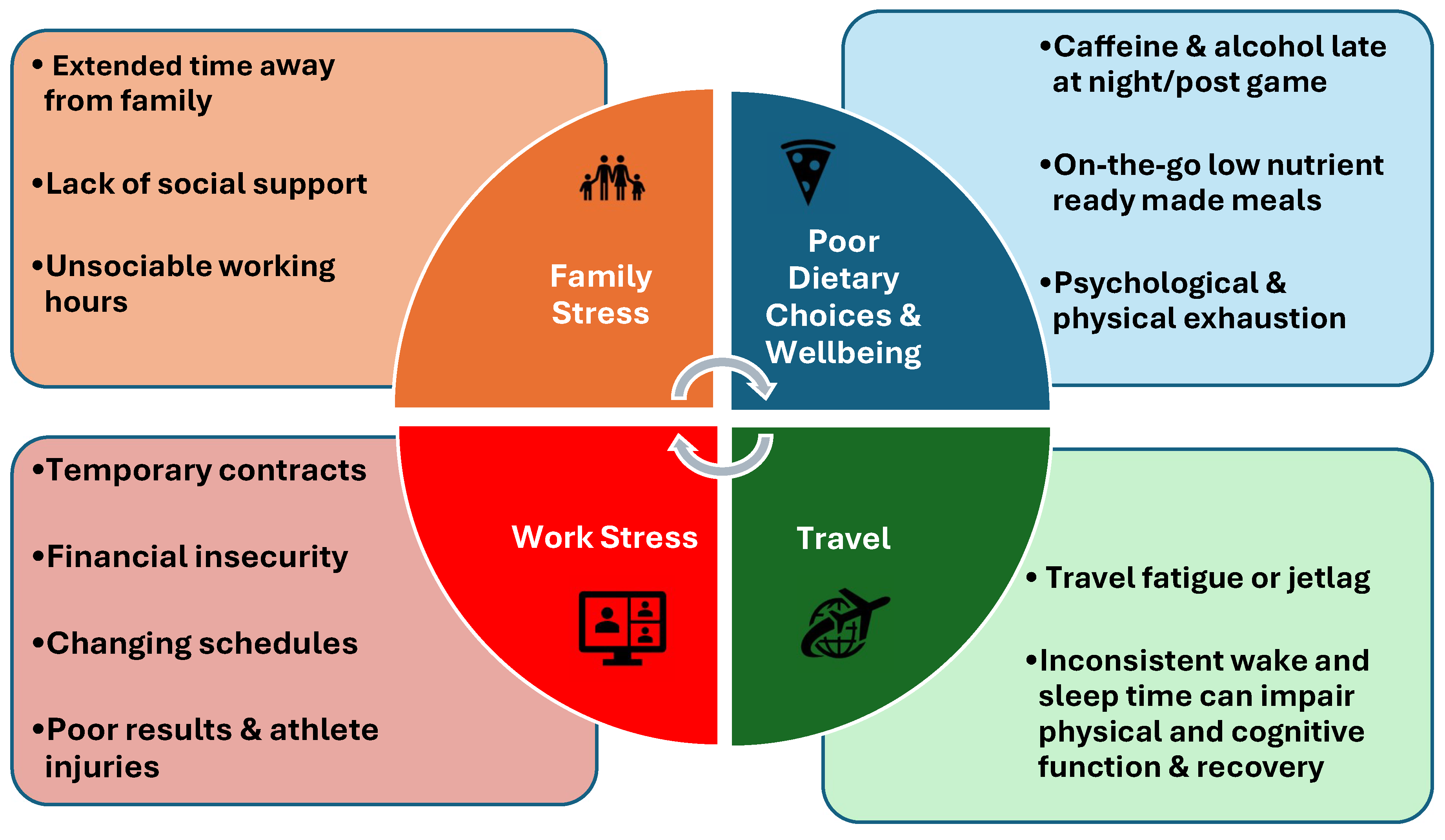

Despite having good sleep knowledge (Miles et al., 2019), support staff report poor sleep and sleep disturbances (Biggins et al., 2019; Pilkington et al., 2022). Research specifically on support staff and sleep in elite sport is lacking (Curtis et al., 2024). Support staff, while part of a high-performance setting, can be considered members of the general population regarding health and sleep, although they experience specific sporting demands such as travel across different time zones, irregular game times and stress related to results (Curtis et al., 2024). Poor diet, high caffeine intake, shift work and alcohol contribute to sleep disturbances in the general population (Jackson et al., 2020) and support staff (Chen et al., 2023; Curtis et al., 2024). Alcohol may alter circadian rhythm and negatively affect the sleep-wake cycle (Doherty et al., 2019) and due to the high demands of sport, alcohol consumption and sleep disruption may be a factor in poor sleep hygiene among support staff. Travel and attempting to sleep after late-night competition may be more prevalent in athletic populations and support staff (Charest & Grandner, 2024) than the general population. Support staff often travel with athletes, sometimes for hours or days, with travel, particularly eastward, disrupting sleep and circadian rhythm (Curtis et al., 2024; Doherty et al., 2019). Short-term contracts (1–2 years) create job and financial insecurity, adding stress (Curtis et al., 2024), which is a leading cause of sleep disturbances (Ramar et al., 2021). Calleja-González et al., (2021) indicated that multidisciplinary sports science support staff experience stressors including travel, fatigue, emotional stress and sleep disorders. Fatigue and mental health symptoms rates range from 39–55%, stress-related disorders from ~70%, and sleep disturbances from ~18% (Curtis et al., 2024). Working on athlete recovery days can lead to longer workdays, late-night meetings, and immediate data demands (Curtis et al., 2024). Specific stressors for support staff may include eye health issues, carpal tunnel syndrome or psychological exhaustion, all potentially affecting sleep quality. Curtis et al., (2024) note that more research is needed beyond soccer to confirm if multidisciplinary staff in all elite sports experience similar stressors and compromised immunity. Walsh et al., (2021) summarized potential contributors to sleep issues in athletes therefore a similar figure is required for support staff. A novel summary of the contributors to poor sleep in this cohort is highlighted in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Factors potentially affecting the sleep of support staff.

Figure 1.

Factors potentially affecting the sleep of support staff.

Due to the disparity and the lack of a clear definition of elite-ness, in the research, Swann et al., (2015) developed a taxonomy which has been further developed by McKay et al., (2022) to allow for classification and reporting of the level of elite athlete cohorts. McKay et al. (2022) introduced a six-tiered Participant Classification Framework to standardize athlete categorization, improving study reliability and comparability. It is worth highlighting that elite athletes experience unique external stressors over and above what non-elite athletes experience due to training volume, changing schedules, contracts and travel and can be categorized using a taxonomy that ranges from regional to Olympic-level competitors (McKay et al., 2022; Swann et al., 2015). Notably, psychological differences also exist between elite and non-elite athletes including higher self-efficacy and a present-focused time perspective, while physiological distinctions involve superior VO₂ max, anaerobic thresholds and running economy in endurance sports (Lorenz et al., 2013; Mitić et al., 2021). It is important to acknowledge the psychological and physiological differences between elite and non-elite athletes, for this research, given that the sleep behaviours and effectiveness of nutrition interventions on sleep may vary between cohorts.

A nutrient-dense diet supports sleep and recovery (Moss et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023; Zuraikat et al., 2020), with emerging evidence suggesting that nutrition interventions enhance sleep quality (Vlahoyiannis et al., 2024). Optimizing sleep is crucial for athletes, due to its influence on recovery, performance and overall health. Several nutritional interventions such as; high GI carbohydrate intake, tryptophan supplementation, kiwifruit, tart cherry juice, zinc and magnesium have been explored to enhance sleep quality and duration in athletes. The potential for nutrition to improve sleep is clear; however, the lack of interventions specifically for elite athletes (Charest & Grandner, 2024; Doherty et al., 2019; Doherty, Madigan, Nevill, et al., 2023; Halson, 2014; Moss et al., 2022) and support staff (Curtis et al., 2024) justified this scoping review. Walsh et al., (2021) recommended that researchers collaborate and use more consistent methods to improve evidence quality and inform practice within sleep research. Therefore, the overarching goal of this scoping review was to map the existing literature, assess the practical applicability of interventions using the Paper to Podium (P2P) Matrix and identify practical nutrition recommendations that influence sleep quality and quantity in these populations for practitioner use.

2. Materials and Methods

The This scoping review adheres to the PRISMA statement for scoping reviews (Prisma-SCR) and the protocol is not registered.

Search strategy

Five databases (PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, CINAHL and Google Scholar) were searched from their inception to December 2024 using predefined keywords (‘Nutrition’ AND ‘Sleep AND ‘Elite Athletes’) and (‘Nutrition’ AND ‘Sleep AND ‘Support Staff’ AND ‘Coaches’. The addition of search terms ‘Support Staff in Sport’ Coaches in Sport’, was applied to ensure no relevant articles were missed. Limits were applied to include studies published in the English language, in humans. A manual search of the reference lists of relevant publications was also conducted to ensure that no relevant articles were missed.

Study Criteria:

To be eligible for inclusion in this review, a study had to be conducted in elite athletes or support staff populations (≥18 years) free of any medically diagnosed health conditions, eating disorders (e.g. anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa), mental health conditions, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Eligible studies reported an intervention that modified either (i) components of diet (e.g. energy intake, macronutrient intake, intake of a specific food/ beverage, or dietary pattern), or (ii) components of sleep health (e.g. sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep timing) or sleep hygiene practices, and reported diet or sleep health outcomes. For the purposes of this review, randomised controlled trials, randomised and non-randomised cross-over studies, and pre-post studies conducted in free-living, laboratory and mixed settings were included. Reviews, meta-analyses, observational studies, case studies, editorials and conference abstracts were excluded.

Study Selection

Duplicates and articles published before 1970 were removed, as collectively these databases report that they reliably index records from 1970 onward. The remaining title and abstracts were screened by the author and lead supervisor using the predetermined inclusion/exclusion criterion. Full texts were retrieved and evaluated against the inclusion/exclusion criteria independently.

Data Charting

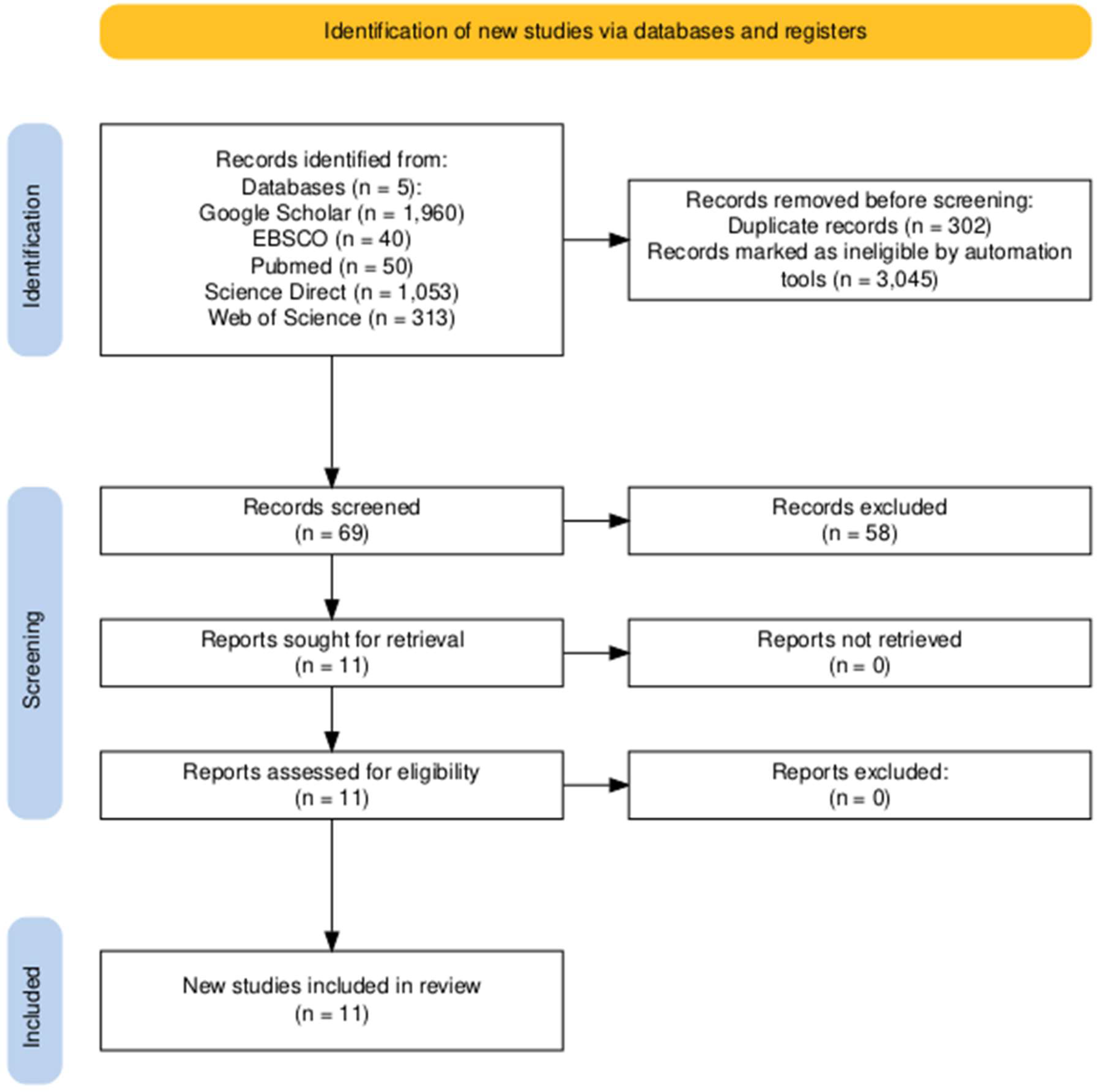

A data extraction form was created by the lead researcher to determine the variables to extract. The form included characteristics and information outlined in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Any disagreements were resolved in discussion with the lead researcher and lead supervisor. Data extracted included study design, participant characteristics, the intervention type and the intervention delivery method. For the purpose of this scoping review the dietary interventions were classified into; Major intervention approach (including supplements), altered nutrient intake (which included interventions where only one aspect of the diet was being modified), fasting/energy restriction, altered overall diet (such as changes in overall diet pattern, low carbohydrate diet) and any ‘other’ interventions could be classified into any of the aforementioned categories. Sleep outcomes were classified as sleep onset SOL, SE, sleep quality, wakening after sleep onset (WASO) or TST. Methodological quality was assessed using NUQUEST.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for nutrition interventions for sleep in elite athletes.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for nutrition interventions for sleep in elite athletes.

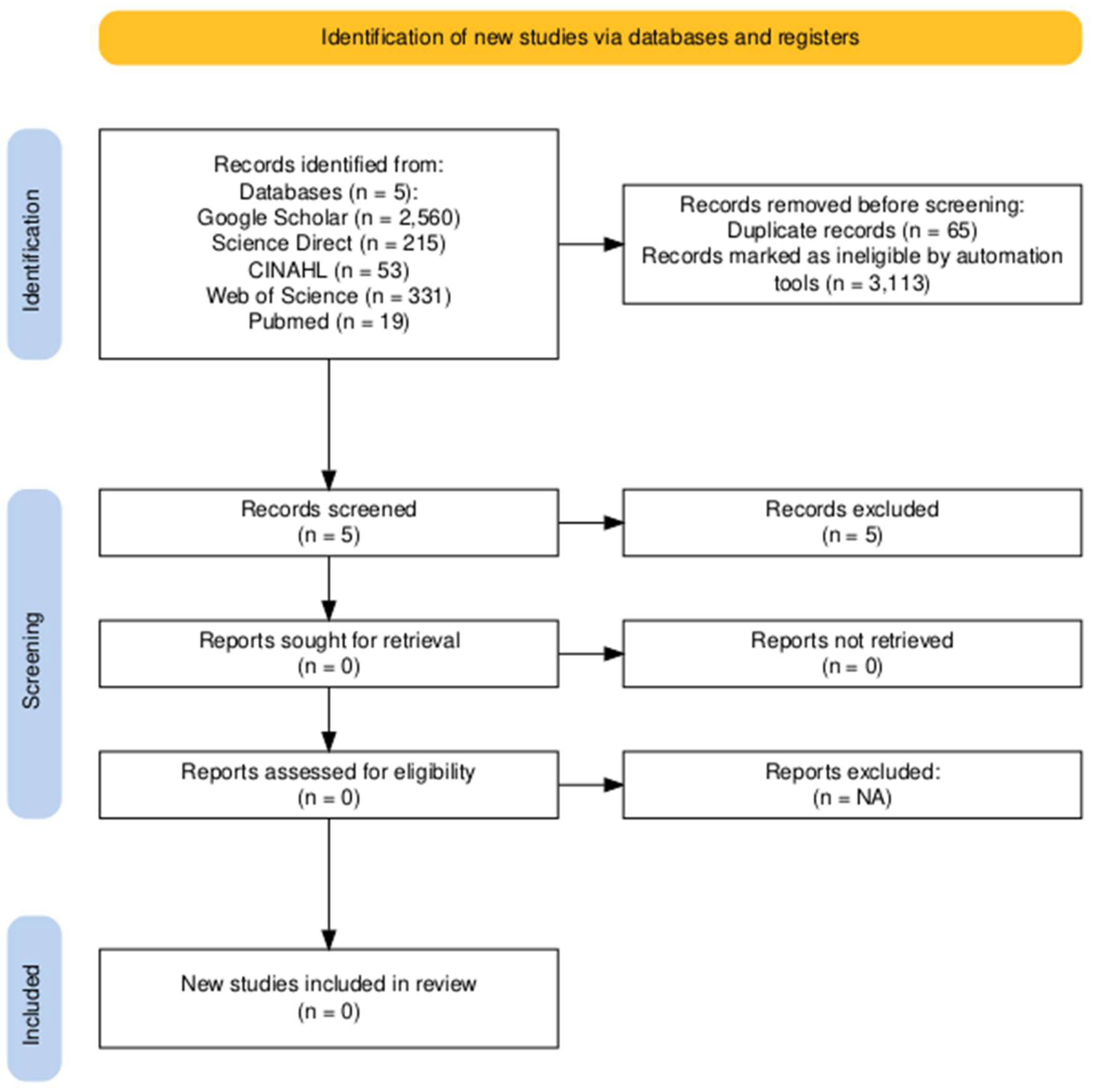

Figure 3.

Flow Diagram for support staff & coaches.

Figure 3.

Flow Diagram for support staff & coaches.

NUQUEST

Using Nutrition Quality Evaluation Strengthening Tools (NUQUEST) for this scoping review involved systematically applying the tool to evaluate the quality and risk of bias (RoB) in each study included. The NUQUEST scoring system assessed the RoB in nutrition studies by evaluating specific methodological domains critical to study quality. These domains included participant selection, exposure and outcome measurement, confounding control, and reporting transparency. Each domain was scored based on predefined criteria, reflecting the extent to which the study adheres to rigorous scientific standards. Higher scores indicated a lower RoB, while lower scores suggest greater susceptibility to methodological flaws. RoB tools for nutrition RCTs, cohort, and case-control studies were utilised (Kelly et al., 2022). These tools were designed to evaluate the RoB in human nutrition studies by integrating nutrition-specific criteria into assessment domains (Kelly et al., 2022). In this scoping review RCTs and cohort studies were applicable. Each domain was rated as either good, neutral, or poor; domain ratings were reached using a prespecified point system already in place by the original researcher (Kelly et al., 2022). A NUQUEST tool for cross-sectional studies does not currently exist. The lead investigator independently performed RoB assessments for each included study, with all investigators participating in reviewing the assessments. RoB assessments are in the Appendices.

The Paper to Podium Matrix

To enhance the practical applicability of the recommendations, from this review, the checklist of criteria from Close et al.'s (2019) paper, "From Paper to Podium (P2P): Quantifying the Translational Potential of Performance Nutrition Research," was utilised. This framework serves as a critical tool for evaluating performance nutrition research and assessing its applicability in real-world practice. This operational framework assesses (1) research context, (2) participant characteristics, (3) research design, (4) dietary and exercise controls, (5) validity and reliability of exercise performance tests, (6) data analytics, (7) feasibility of application, (8) risk/reward and (9) timing of the intervention. A five-point numerical grading scale (−2, −1, 0, +1, +2) was used to calculate the total scores from each assessment area and into one of the following outcomes:

Exercise caution when applying to practice: Studies with a total negative score.

May be appropriate to guide implementation, but some caution is needed: Studies with a zero to low positive total score.

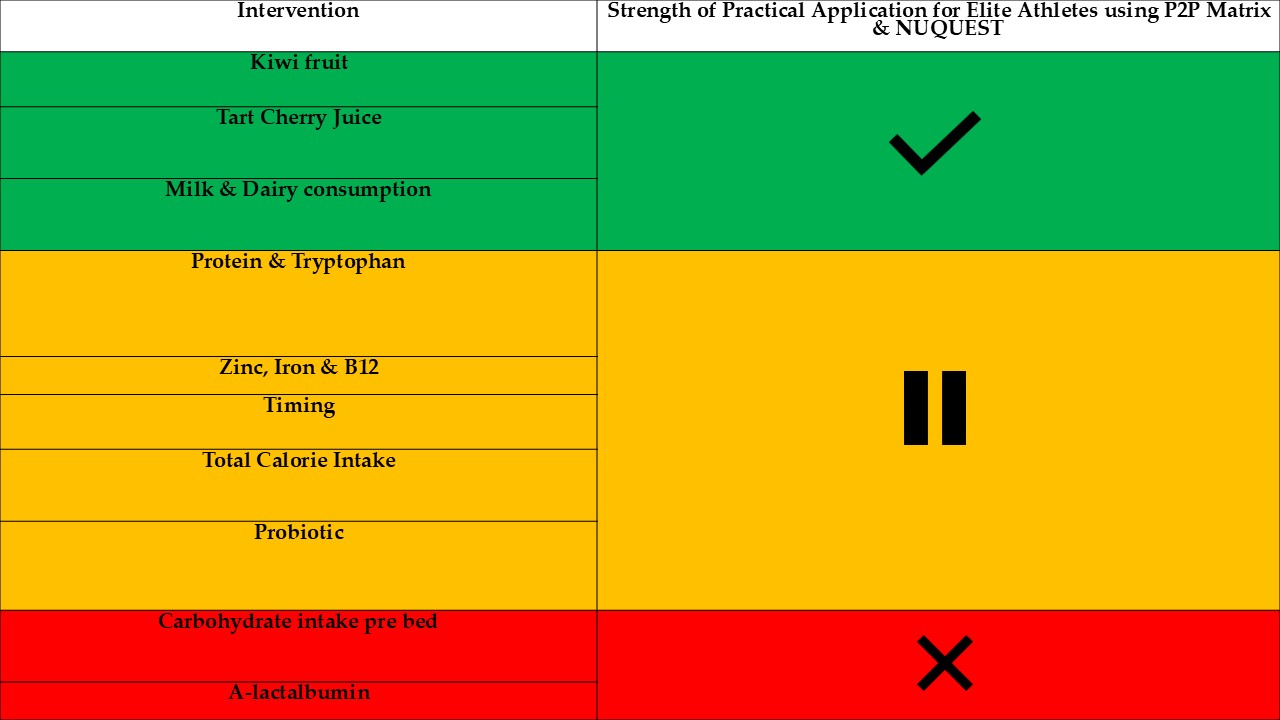

This approach enhances clarity for practitioners by highlighting well-supported recommendations, enabling them to make informed decisions for the athletes they support. Details on the total scores for each study can be found in the supplemental material. See

Table 2 for the colour scheme grading and the scoring system that is later utilised in

Table 4 grading the checklist criteria within each paper. A novel application of using the P2P Matrix alongside NUQUEST gave pronounced practical application and rigour, by evaluating the RoB, for this scoping review. Practitioners can use the P2P scoring system as a point of reference when applying nutrition interventions to elite athletes. The highest score possible on the P2P is +18 and the lowest score possible is -18. As alluded to in the methods and materials section there is an operational framework for rating each study.

Table 2.

Operational framework scoring system from the P2P Matrix.

Table 2.

Operational framework scoring system from the P2P Matrix.

| Colour co-ordinated grading scheme |

| Exercise caution when applying to practice: Studies with a total negative score. |

| May be appropriate to guide implementation, but some caution is needed: Studies with a zero to low positive total score. |

| Appropriate to guide practice: Studies with a moderate to high positive total score. |

3. Results

This Search Results

The search criteria strategy identified 3,416 articles for screening (

Figure 2) and an additional 3 articles were identified through a manual search of reference list of included studies. Following title and abstract screening 69 studies were identified for full text review, from which 58 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. In total 11 studies were included for the current review. Five studies focused on dietary interventions reporting sleep outcomes, while six studies focused on sleep outcomes based on dietary intake. The support staff PRISMA flow diagram yielded no results (

Figure 3).

Table 3 presents participant characteristics. The mean (SD) age was 22.92 (2.61) years (range: 16–30 years). Three studies (27.27%) included mixed sexes, four (36.36%) included only males, and three (27.27%) included only females. Sex was not reported in one study (Valenzuela et al., 2023). Ten studies reported body mass (kg), with a mean (SD) of 76.92 (18.99 kg) (range: 47–119 kg).

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants.

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants.

| Characteristic |

Mean ± SD |

| Gender |

M = 542 / F = 408 |

| Unknown Gender |

24 participants |

| Age (years) |

22.92 ± 2.61 |

| Body Mass (kg) |

76.92 ± 18.99 |

| Height (cm) |

174.11 ± 10.37 |

| Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with ranges where available |

Sport Breakdown and Sleep Assessments

All participants were designated as elite athletes within their given sport (McKay et al., 2022; Swann et al., 2015) and no specific dietary intervention study returned for support staff. The included studies utilised a various designs, including randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 4), cohort studies (n = 3), crossover trials (n = 2), a retrospective study (n = 1), and a pilot study (n = 1). The total number of participants across all studies was 974 elite athletes, representing various sports. It must noted that the primary contributor to the 974 athletes was the 679 Olympic candidates recruited in one study (Yasuda et al., 2019).

Sleep was assessed through wrist activity monitors and actigraphy (Condo et al., 2022; Falkenberg et al., 2021; Ferguson et al., 2022), WHOOP bands (Greenwalt et al., 2023) and salivary melatonin biomarkers (Harnett et al., 2021). Self-reported measures included sleep diaries (Condo et al., 2022; Doherty et al., 2023; Ferguson et al., 2022), questionnaire batteries such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Doherty et al., 2023b) and the Richard-Campbell Sleep Scale (RCSQ) (Eroğlu et al., 2024). Additionally, self-rated sleep quality surveys were employed in several studies (Chung et al., 2022; Valenzuela et al., 2023; Yasuda et al., 2019). Collectively, these methods were used to examine TST, SOL, WASO, SE and subjective sleep quality.

NUQUEST

NUQUEST classifications, as seen in

Table 5, catergorised 9 of the 11 studies as good (+), and two were rated as neutral (0) regarding risk of bias. See Appendices for scoring system on NUQUEST grading.

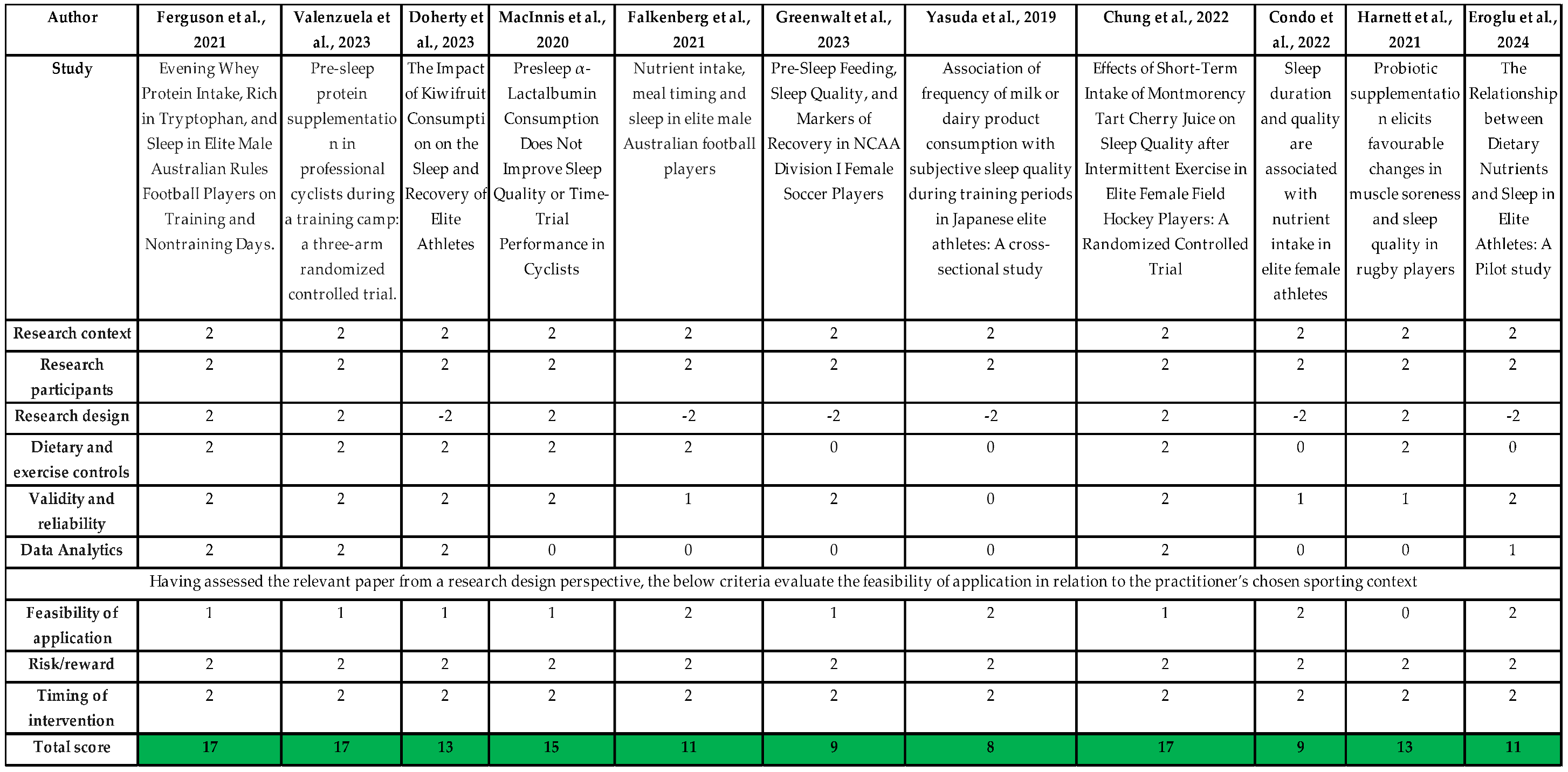

Paper to Podium Matrix

Three studies scored + 17 on the P2P scoring system (Chung et al., 2022; Ferguson et al., 2022; Valenzuela et al., 2023) which indicates a positive score in each of the areas in the framework (context, participants, design, dietary & exercise controls, validity & reliability, data analytics, feasibility of application, risk/reward and timing of intervention) ass seen in

Table 4. Each of the research designs were double-blind randomised trials investigating a nutrition intervention on sleep outcomes. Outcomes varied within the three studies but no significant improvement was demonstrated in sleep duration (Ferguson et al., 2022; Valenzuela et al., 2023), however subjective measures of sleep did improve (Chung et al., 2022).

A prospective study (Condo et al., 2022), cross sectional study (Yasuda et al., 2019) and retrospective study (Greenwalt et al., 2023) were each marked in the lowest 3 in relation to the P2P scoring system. The reason for this was not due to validity or reliability or the research participants more so their research designs been categorized -2 as ‘no control group and no blinding of intervention and no consideration of sample size’ was deemed the most appropriate reference point for their studies. Interestingly, 2 of the lowest rated studies on the P2P criteria were also rated as neutral on the NUQUEST risk of bias (Greenwalt et al., 2023; Yasuda et al., 2019) this is due to the studies being retrospective and cross sectional and used WHOOP bands, self-reported surveys and self-reported questionnaire to assess sleep. This may have an increased risk of bias on behalf of the participants to choose a positive sleep outcome.

Table 4.

Outcomes of the Paper to Podium Matrix using the included studies.

Table 4.

Outcomes of the Paper to Podium Matrix using the included studies.

Table 5.

Nutrient Interaction with Sleep Outcomes in Elite Athletes with PICO Framework, NUQUEST & P2P.

Table 5.

Nutrient Interaction with Sleep Outcomes in Elite Athletes with PICO Framework, NUQUEST & P2P.

| Author |

Study Design |

Population |

Sleep Assessment |

Nutrient Intervention |

Timing |

Sleep Outcome |

NUQUEST Rating |

P2P Rating |

| Ferguson et al., 2021 |

Double-blinded, counterbalanced, randomised, cross-over study |

15 elite male AFL players |

Wrist activity monitors and sleep diaries |

55 g whey protein (1 g tryptophan) |

Evening (on training and 2 non-training days) |

No improvement in sleep duration or quality who already have adequate sleep |

Good (+) |

17 |

| Valenzuela et al., 2023 |

Double-blinded, parallel-group, three-arm, randomised controlled design. |

24 Pro U23 Cyclists |

Self-rated sleep quality |

40 g casein |

40 g casein (10.30 PM), 40 g casein (6.30 PM), or 40 g carbs (10.30 PM) at 6-day training camp |

No significant group differences in sleep quality |

Good (+) |

17 |

| Doherty et al., 2023 |

Open Label Trial |

15 elite national sailors and middle-distance runners |

Questionnaire battery (RESTq Sport, PSQI, CSD-C, RU- Stated, sleep diary |

130 g or 2 kiwi fruit. Following the baseline assessment (Week 1) all subjects began the intervention (Weeks 2–5). |

1 hour pre-bed |

Improved sleep quality, increased TST & SE %, fewer awakenings and WASO |

Good (+) |

13 |

| MacInnis et al., 2020 |

Randomized, Double- Blind Cross over Design |

6 male elite cyclists |

Wrist based acti-graphy |

A 40-g serving of LA contained 19.7, 4.3, and 1.9 g of essential amino acids, leucine, and tryptophan |

2 hours pre-sleep (3 consecutive evenings) |

No improvement in TST, time in bed, or SE |

Good (+) |

15 |

| Falkenberg et al., 2021 |

Prospective cohort study design |

36 male elite AFL |

Wrist actigraphy, sleep diaries |

Evening sugar, protein and meal timing analysis |

10 consecutive days (pre-season) |

High sugar and long time between eating and bed reduced TST; evening protein reduced SOL |

Good (+) |

11 |

| Greenwalt et al., 2023 |

Retrospective Study |

14 Div 1 female soccer players |

WHOOP bands (24h monitoring), surveys |

Pre-sleep protein intake (>5 g) |

Various times |

>5 g protein before bed lowered recovery score by 11.41 percentage points but no significant effect |

Neutral (0) |

9 |

| Yasuda et al., 2019 |

Cross Sectional Study |

679 Japanese elite athletes (2016 Rio candidates) |

Self-reported questionnaires |

Frequency of milk/dairy consumption (0-2x, 3-5x, 6-7x per week) |

Ongoing |

Higher milk consumption associated with better sleep quality in women, not men |

Neutral (0) |

8 |

| Chung et al., 2022 |

Double Blind Randomised Control Trial |

19 elite female hockey players |

Sleep quality, melatonin & cortisol levels |

30 mL tart cherry juice in 200 mL water |

5 doses over 48 hours (morning and evening) |

No effect on melatonin/cortisol, but improved sleep quality |

Good (+) |

17 |

| Condo et al., 2022 |

Prospective Cohort Study |

32 elite female Australian footballers |

Activity monitors, sleep diaries |

Diet monitored (carbohydrate, fat, iron, zinc, B12) |

10 consecutive days (pre-season) |

Increased carbohydrate intake associated with increased WASO & decreased SE. Higher iron, zinc, and B12 improved sleep outcomes |

Good (+) |

9 |

| Harnett et al., 2021 |

Double Blind randomised control trial |

19 elite male rugby athletes |

Self-reported sleep quality, salivary biomarkers |

Daily probiotic (Ultrabiotic 60TM & SBFloractvi TM with 250 mg Saccharomyces boulardii) vs. placebo |

Daily for 17 weeks |

Across both groups, increased muscle soreness & CRP reduced sleep quality; decreased soreness & CRP improved sleep |

Good (+) |

13 |

| Ergolu et al., 2024 |

A Pilot Study – Cross sectional design |

115 elite athletes (swimming, canoeing, archery, volleyball, taekwondo) |

Richard-Campbell Sleep Scale (RCSQ) |

24-hour food consumption recorded and analysed using nutritional software (Nutrition Information Systems (BeBiS version 8.1) |

None |

Insufficient calorie intake associated with poorer sleep. Good sleepers consumed 1.6 g/kg BM protein and 1350 mg tryptophan |

Good (+) |

11 |

3.1. The nutrition interventions and resultant sleep outcomes

All nutrient interventions and their effect on sleep parameters are summarised in

Table 5.

3.1.1. Kiwi Fruit:

One included study investigated kiwi fruit (Doherty, Madigan, Nevill, et al., 2023). PSQI global scores reduced significantly from baseline (6.47 ± 2.17) to post-intervention after consumption of 2 kiwis 1 hour before bed for 4 weeks (4.13 ± 1.19; z = 91, p = 0.002). Sleep quality improved significantly from baseline (1.53 ± 0.84) to post-intervention (0.27 ± 0.46; z = 78, p = 0.002). TST improved week to week from baseline to post-intervention (F (4, 44) = 6.653, p = 0.001 partial η2 = 0.38). TST increased from baseline 7.6 ± 0.75 h to 8.55 ± 0.44 hr at week 4, a statistically significant increase of 0.83 ± 0.23 ([mean ± standard error], p < 0.05). Number of awakenings (NoA) reduced significantly from baseline to intervention: χ2(4) = 12.6, p < 0.05. There was a statistically significant reduction in NoA compared to baseline in weeks 3 (p = 0.003) and 4 (p = 0.012). WASO reduced significantly from baseline to intervention: χ2(4) = 12.5, p < 0.05. Statistically significant reduction in WASO compared to baseline in week 3 (p = 0.002), week 4 (p = 0.003) and week 5 (p = 0.014). SE increased significantly from baseline to intervention: χ2(4) = 21.2, p ≤ 0.001. statistically significant increase in SE compared to baseline in week 2 (p = 0.018), week 3 (p < 0.001), week 4 (p < 0.001) and week 5 (p < 0.001). was a statistically significant reduction in Fatigue in the Morning compared to baseline in week 5 (p = 0.041).

3.1.2. Tart Cherry Juice:

One included study investigated tart cherry juice (Chung et al. 2022). Significant interaction effects (group × time) between sleep quality variables and the consumption of tart cherry juice (TCJ) five times over 48 hours. Specifically, TCJ intake influenced TTB (p = 0.015), WASO (p = 0.044), and Movement Index (MI) (p = 0.031). TTB showed significant differences (p = 0.005) before and after in the TCJ group and significant differences (p = 0.005) between the PLA group and the TCJ group after the intake of tart cherry juice. In the case of WASO, it showed significant differences (p = 0.024) before and after in the TCJ group. Levels of melatonin and cortisol could not be changed significantly, however.

3.1.3. Probiotic:

One included study investigated probiotics (Harnett et al., 2021) and found that muscle soreness was ~0.5 units lower (F (1, 343) = 42.646, p < 0.0001) and leg heaviness scores ~0.7 units lower (F1, 334) = 28.990, p < 0.0001) in the probiotic group versus placebo group in 19 elite rugby union male athletes over 17 weeks. Across both groups as self-reported muscle soreness scores and salivary c-Reactive Protein (CRP) concentrations increased, sleep quality, quantity and motivation scores decreased. Conversely as muscle soreness scores and CRP decreased, sleep quality, quantity and motivation scores improved.

3.1.4. Protein & Typtophan:

Ferguson et al., (2022) demonstrated that the habitual sleep/wake behaviour during the 5-day preintervention period for bedtime, SOL, WASO, SE, wakeup time, and sleep duration on training days was 23:18 ± 1:12 (hr:min) time, 18.8 ± 10.0 min, 52.6 ± 31 min, 90.0 ± 5.6%, 08:36 ± 01:18 (hr:min), and 7.9 ± 1.1 hr, respectively, and on non-training days was 22:54 ± 1:06 (hr:min), 20.8 ± 13.1 min, 49.5 ± 23.6 min, 89.7 ± 4.3%, 07:18 ± 00:30 (hr:min), and 7.1 ± 0.8 hr, respectively. The average habitual daily protein intake was 226.8 ± 53.5 g (2.6 ± 0.7 g·kg⁻¹) on training days and 205.9 ± 64.8 g (2.4 ± 0.7 g·kg⁻¹) on non-training days. No differences were observed for all sleep outcomes between consumption of the whey protein supplement (55g), rich in tryptophan (1g), and the placebo on training and non-training days.

3.1.5. Casein:

Timing of casein (40g) (Valenzuela et al., 2023) before sleep or earlier in the day resulted in no significant time effect interaction on sleep scores (1-7) measured during the 6 day training period. The findings revealed a significant increase in training loads during the camp, leading to elevated indicators of fatigue and decreased performance, between day 1 and day 6. Despite high protein intake (>2.5 g/kg on average), no significant differences were observed between the protein supplement groups and the placebo in any of the outcomes. Protein supplementation did not show beneficial effects during the short-term strenuous training period, indicating that professional cyclists naturally consuming a high-protein diet may not benefit additionally from supplementation. Macronutrient intake during the camp was similar among the groups for total energy, carbohydrate, and fat intake. However, protein intake was significantly higher in the pre-sleep PRO and Afternoon PRO groups compared to the Placebo group (p < 0.001). A significant time effect was noted for the total Hooper index score, fatigue, and DOMS, all increasing over time, except for sleep and stress. No significant group-by-time interaction effect was observed for these factors.

3.1.6. A-lactalbumin (LA):

One included study investigated A-lactalbumin (LA), MacInnis, (2020) and showed there were no differences between the collagen peptides (CP) and pre-sleep consumption of α-lactalbumin (LA), a fraction of whey with a high abundance of tryptophan, in terms of TTB, TST or SE in 6 elite male endurance track cyclists (LA: 568 ± 71 min, 503 ± 67 min, 88.3% ± 3.4%; CP: 546 ± 30 min, 479 ± 35 min, 87.8% ± 3.1%; p = .41, p = .32, p = 0.74, respectively.

3.1.7. Dairy:

One included study investigated the effect of dairy consumption on sleep (Yasuda et al., 2019). It was indicated that no significant associations of sex with type of sport, subjective sleep quality or frequency of milk or dairy product consumption being observed in 679 elite athletes looking to qualify for the Olympic games. The men (n = 379) showed significantly higher values of age, height, weight, BMI, waking time, bedtime, midpoint of sleep, and sleep duration, although they showed a lower frequency of dairy product consumption than the women (p< 0.001). There was also no statistically significant association between subjective sleep quality and frequency of milk consumption in all subjects and men, a greater frequency of milk consumption was significantly associated with good subjective sleep quality in women (p < 0.001). In men, there were no statistically significant associations of the frequencies of either milk or dairy product consumption with subjective sleep quality in any model. A greater frequency of milk consumption was significantly associated with a lower risk of decrease in subjective sleep quality, during training periods in women only.

3.1.8. Energy Intake:

As seen in

Table 5, in the prospective cohort study by Condo et al., (2022) 32 female AFWL players showed no significant association between energy intake and any sleep outcome. For 1g increase in daily carbohydrate intake WASO increased by 0.05 min (p = 0.010) and SE decreased by 0.01% (p = 0.007). For each 1 g·kg⁻¹ increase in daily carbohydrate WASO increased by 3.6 min (p = 0.007) and SE decreased by 0.6% (p = 0.007). For 1g increase in saturated intake SOL decreased by 0.27 min (p = 0.030) and for 1 g·kg⁻¹ increase in saturated fat SOL decreased by 17 min (p = 0.049). Condo et al., (2022) showed that for each 1mg increase in daily iron intake sleep duration increased by 0.55 min (p < 0.001) and SE increased by 0.05% (p < 0.001). For 1mg increase in sodium, sleep decreased by 0.012min (p < 0.001). For each 1-μg increase in vitamin B12, WASO decreased by 1.7 min (p = 0.020) and SE increased by 0.4% (p = 0.033). For each 1-mg increase in zinc SE increased by 0.23% (p = 0.006). For each 1-mg increase in vitamin E, SE decreased by 0.08% (p = 0.016). For each 1-mg increase in calcium, SOL reduced by 0.005 min (p = 0.015). For each 1mg increase in magnesium SOL reduced by 0.02 min (p = 0.031).

3.1.9. Energy intake:

In the other prospective cohort study in 36 male elite athletes (Falkenberg et al., 2021) every 1g and 1 g·kg⁻¹ increase in total daily protein intake was associated with a decrease in SE by 0.01% (p = 0.007) and 0.7% (p = 0.006) respectively. Every 1 Mega Joule (MJ) increase in total daily energy intake was associated with a three-minute increase in WASO (p = 0.032). Every 1g and 1 g·kg⁻¹ increase in total protein intake was associated with an increase in WASO by 0.04 min (2 s; p = 0.014) and 4 min (p = 0.013), respectively. Every 1g and 1 g·kg⁻¹ increase in evening sugar was associated with a decrease in TST by 0.1 min (6 s; p = 0.039) and 5 min (p = 0.027), respectively; an increase in SE by 0.002% (p = 0.015) and 0.2 % (p = 0.021), respectively and a decrease in WASO by 0.012 min (1s; p = 0.003) and one minute (p = 0.005), respectively. Significant associations were found between evening energy and protein intakes and SOL. Every 1MJ increase in evening energy intake was associated with an increase in SOL by 5 min (p = 0.011). Every 1g and g·kg⁻¹ increase in evening protein intake was associated with a decrease in SOL by 0.03 min (2 s; p = 0.013) and 2 min (p = 0.013), respectively. Every additional hour between the main evening meal and bedtime was associated with a decrease in TST by 8 min (p = 0.042) and decrease in WASO by 2 min (p = 0.015). Every additional hour between the last food or drink (excluding water) consumed and bed time was associated with a decrease in TST by 6 min (p = 0.014) (Falkenberg et al., 2021).

3.1.10. Energy intake:

In 115 elite athletes Eroğlu et al., (2024) the RCSQ scores were used to compare the intake of nutrients in poor sleeper and good sleeper groups. The good sleeper group had higher energy (kcal), protein (g·kg⁻¹ and g) and tryptophan (g·kg⁻¹ and g) intakes (p < 0.05). Glycaemic index (GI) values of last meal was similar (p > 0.05).

3.1.11. Type of Macronutrient pre sleep:

In 14 Division 1 females soccer players Greenwalt et al., (2023) concluded that sleep duration (p = 0.10, 0.69, 0.16, 0.17) and sleep disturbances (p = 0.42, 0.65, 0.81, 0.81) were not affected by high versus low kilocalorie (kcal), protein (PRO), fat, carbohydrate (CHO) intake, respectively. Recovery (p = 0.81, 0.06, 0.81, 0.92) was also not affected by high versus low kcal, PRO, fat, or CHO consumption. Consuming a small meal before bed may have no impact on sleep or recovery. Those who had more than 5 g of protein before bed had a recovery score of 11.41 percentage points lower than those who ate less than 5 g of protein pre-sleep.

Table 6.

Summary of potential nutrition strategies for elite athletes to promote sleep or mitigate sleep loss.

Table 6.

Summary of potential nutrition strategies for elite athletes to promote sleep or mitigate sleep loss.

| Intervention |

Application of Intervention |

Strength of Practical Application using P2P Matrix & NUQUEST |

| Kiwi fruit |

2 x kiwifruit (1 hr. Before bed) may improve sleep duration, SE, NoA, sleep quality and reduce fatigue the morning after. |

High |

| Tart Cherry Juice |

30ml tart cherry juice consumed 5 times over 48 hours, morning and evening, may improve TTB, reduced periods of WASO and reduced movement index while sleeping. |

High |

| Milk & Dairy consumption |

Greater frequency of milk consumption (5-7d/wk), during training periods, is associated lower risk of decrease in subjective sleep quality in elite female athletes but not male. |

High |

| Protein & Tryptophan |

Higher evening protein intake (> 1 hr. pre sleep) is associated with shorter SOL. Both male and female elite athletes, categorised as good sleepers, tend to consume protein of ~1.6g·kg⁻¹ per day and a tryptophan intake of ~1350mg. Improvements inconclusive if already consuming high protein diet (>2.5kg. g -1) |

Moderate |

| Zinc, Iron & B12 |

Optimal levels of Zinc, Vitamin B12 and Iron may improve reported quality in elite female athletes. |

Moderate |

| Timing |

Every additional 1 hour between the main evening meal and bedtime may be associated with a decrease in TST and in reduced periods of WASO. |

Moderate |

| Total Calorie Intake |

Insufficient calorie intake is associated with poorer sleep so appropriate refuelling strategies to meet caloric demands closer to bed time may increase TST for elite male & female athletes. |

Moderate |

| Probiotic |

Daily probiotic (Ultrabiotic 60TM & SBFloractvi TM with 250 mg Saccharomyces boulardii) consumption for 17 weeks may help leg heaviness and muscle soreness with reduced CRP concentrations & muscle soreness being related to improved sleep quality and quantity. |

Moderate |

| Carbohydrate intake pre bed |

Elite female athletes should carefully plan their carbohydrate intake to meet energy & recovery needs, as high carbohydrate intakes are associated with increased WASO and reduced SE. |

Moderate – Low |

| A-lactalbumin |

No difference in sleep quality compared to collagen peptides. |

Moderate – Low |

4. Discussion

Several nutritional interventions have been explored to enhance sleep quality and duration in athletes. The potential for nutrition to improve sleep is clear; however, there are a lack of interventions specifically for elite athletes (Charest & Grandner, 2024; Doherty et al., 2019; Doherty, Madigan, Nevill, et al., 2023; Halson, 2014; Moss et al., 2022) and support staff (Curtis et al., 2024). One of the primary interventions is relationship between carbohydrate consumption and sleep. Some studies suggest that high GI carbohydrates consumed in the evening may reduce SOL, potentially by increasing tryptophan availability, a precursor to serotonin and melatonin, which regulate sleep (Afaghi et al., 2007). However, evidence is inconclusive, and further research is needed to establish definitive guidelines (Doherty et al., 2019; Gratwicke et al., 2021). Tryptophan supplementation has shown potential to improve SOL and subjective sleep quality. Doses as low as 1g can potentially be effective, which can be obtained through dietary sources such as turkey or pumpkin seeds (Doherty, Madigan, Warrington, et al., 2023; Halson, 2014). Tart cherry juice is rich in melatonin and antioxidants and studies have shown that consuming tart cherry juice over a two-week period can improve TST and sleep quality (Halson, 2014). Kiwifruit contains antioxidants and serotonin, which may contribute to improved sleep and research indicates that consuming kiwifruit before bedtime may SOL, duration, and SE (Doherty, Madigan, Warrington, et al., 2023; Gratwicke et al., 2021). Adequate intake of micronutrients like magnesium and zinc are hypothesized to maintain sleep health. Deficiencies in these minerals can disrupt sleep patterns. Ensuring sufficient levels through diet or supplementation may support better sleep quality (Doherty, Madigan, Warrington, et al., 2023; Gratwicke et al., 2021).

The 11 selected research papers provide valuable insights into the impact of various nutrient interventions and their effect on sleep outcomes in elite athletes. They collectively contribute to the broader understanding of how nutrition and supplementation can influence elite athlete recovery and performance through sleep improvements. Summary of potential nutrition strategies for elite athletes to promote sleep or mitigate sleep loss is seen in

Table 6.

Fruit

Fruit containing interventions demonstrated some of the most beneficial outcomes on sleep in elite athletes with studies from Doherty, Madigan, Nevill, et al., (2023) and Chung et al., (2022) demonstrating positive impacts. Kiwifruit consumption led to improvements in sleep quality, while tart cherry juice intake resulted in enhanced sleep quality metrics. These findings support the notion that certain fruits, like kiwifruit and tart cherry, may offer natural interventions to promote better sleep and recovery in elite athletes. Kiwifruit has been hypothesized to aid sleep due to its melatonin (24 µg/g) and serotonin (5.8 µg/g) content, which may enhance circadian rhythm regulation by increasing melatonin availability before sleep (Lin et al., 2011). The antioxidant properties of kiwifruit may also reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, while its folate content could mitigate insomnia and restless leg syndrome. Doherty, Madigan, Nevill, et al., (2023) examined the impact of kiwi consumption on sleep in 15 elite athletes, including a national sailing squad (n = 9) and middle-distance runners (n = 6). Participants consumed two kiwis (130g) one hour before bed for four weeks. Sleep quality, measured using the PSQI, significantly improved from baseline to the end of the intervention. Improvements were observed in SE, TST, and reduced awakenings, aligning with previous research in adults with sleep issues (Lin et al., 2011) and students with insomnia (Nødtvedt et al., 2017). Although not in athletes, Lin et al., (2011) examined the effects of consuming two kiwifruits one hour before bedtime over a four-week period in adults with self-reported sleep disturbances. The intervention led to significant improvements in SOL, duration, and SE suggesting potential benefits. Similarly, in a randomized, single-blind crossover study conducted by (Kanon et al., 2023), 24 male participants consumed either fresh or dried green kiwifruit alongside a standardized evening meal. The results demonstrated that both forms of kiwifruit consumption were associated with improved aspects of sleep quality and mood. These benefits were potentially mediated through changes in serotonin metabolism, as evidenced by increased urinary concentrations of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). Despite the open label trial participants being aware of the intervention throughout the trial, kiwi fruit offers a potential natural intervention to improve sleep quality in elite athletes although further trials investigating its effectiveness during competition phase are required.

Regarding the positive effects seen from TCJ, a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled study with 20 volunteers also investigated the consumption of Montmorency tart cherry juice and reported that participants spent less time napping, and more time sleeping and had higher total SE scores compared with baseline and placebo effect of tart cherry juice (Howatson et al., 2012). It was shown that consumption of tart cherry juice concentrates for 7 days significantly reduced napping time but had a non-significant increase in SOL and non-significant increase in SE. Total melatonin content was significantly elevated (p<0.05) in the cherry juice group, whilst no differences were shown between baseline and placebo trials. This suggests that consumption of tart cherry juice concentrate provides an increase in exogenous melatonin that may be beneficial in improving sleep duration and quality in healthy men and women and might be of benefit in managing disturbed sleep. Chung et al., (2022) notes slightly differing outcome measures in the short-term consumption of tart cherry juice consumed 5 times in 48 hrs. in a randomised control trial involving 19 elite hockey players. That group showed a non-significant change in melatonin and cortisol levels while sleep quality did improve. This may be due to the increased requirement for antioxidant intake in elite athletes during training. TCJ offers a food blended supplement intervention that can affect sleep quality, although the application of consuming the supplement 5 times in 48 hours may prove difficult in for elite athletes in a sporting environment.

Milk and Dairy consumption

Yasuda et al., (2019) examined the relationship between milk and dairy product consumption frequencies and subjective sleep quality in Japanese elite athletes training for the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. A total of 679 athletes participated in the study. The participants provided information on demographics, lifestyle, subjective sleep quality, bedtime, waking time, sleep duration, and frequencies of milk and dairy consumption. Athletes were categorized based on low, middle, and high consumption of milk and dairy products. Findings revealed that higher frequencies (5-7 d/wk) of milk consumption were significantly associated with a lower risk of decreased subjective sleep quality in the elite female athletes, after adjusting for factors like smoking, drinking habits, and sleep duration. Logistic regression models showed that the middle and high consumption groups had lower risks of decreased subjective sleep quality compared to the low consumption group in women.

The study did not find significant associations between total milk and dairy consumption frequencies and subjective sleep quality in all subjects or sexes. It highlighted a sex difference, indicating that a greater frequency of milk consumption was linked to good subjective sleep quality in women but not in men. The research suggested that the composition of milk, particularly its tryptophan content, may play a role in improving sleep quality. Tryptophan is a precursor to serotonin and melatonin, which are essential for enhancing sleep quality (Afaghi et al., 2007). The study acknowledged limitations, including its cross-sectional design and reliance on subjective evaluations of sleep quality. The research emphasized the need for further longitudinal and experimental studies to investigate the causal effects of milk consumption on sleep quality in elite athletes. The study's results indicated the practicality of using milk as a dietary strategy to potentially enhance the sleep quality of elite athletes, particularly women, and support their overall well-being during training periods. The findings contribute to the existing knowledge on the association between milk consumption and sleep quality, particularly in elite athletes. The study underscores the importance of exploring the timing and amount of milk consumption and the potential benefits of milk as a cost-effective and accessible dietary option for improving subjective sleep quality in athletes.

Protein & Tryptophan

Ferguson et al., (2022) aimed to investigate the impact of evening whey protein supplementation, rich in tryptophan, on sleep in elite male AFL players. The research was conducted as a double-blinded, counterbalanced, randomized, cross-over study on 15 elite male AFL players in preseason. The participants consumed either an isocaloric whey protein supplement or a placebo 3 hours before bedtime on training and non-training days. The study found that evening whey protein supplementation did not enhance acute sleep duration or quality in elite male athletes. The results showed no significant differences in sleep duration, SOL, SE, or WASO between the whey protein supplement and the placebo on both training and non-training days. The findings contradicted the hypothesis that whey protein supplementation, rich in tryptophan, would lead to improved sleep outcomes due to increased tryptophan availability and melatonin synthesis. The study suggested that there might be a ceiling effect for sleep duration in populations already obtaining adequate sleep, like these athletes. Additionally, the high habitual protein intake of the participants could have limited the potential benefits of additional protein intake on sleep. A hypothesis for this ceiling effect is tryptophan competing with other large neutral amino acids for transport across the blood-brain barrier via the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (Fernstrom, 2013). This competition influences tryptophan availability in the brain, subsequently affecting serotonin and melatonin synthesis, which are crucial for sleep regulation (Fernstrom, 2013). The study highlighted that the consumption of high protein/energy meals in the evening did not negatively impact sleep duration and quality in athletes. However, further research is recommended to explore the effects of evening whey protein supplementation on elite athletes with poor sleep, during restricted sleep periods or with lower habitual protein intake. The study also suggested investigating the impact of protein intake on sleep staging through polysomnography to gain a comprehensive understanding of its effects on athletes' recovery and performance.

In similar results to Ferguson et al., (2022), Valenzuela et al., (2023) found no effect of consuming protein pre sleep on indicators like fatigue/recovery, body composition, and performance outcomes. Valenzuela et al., (2023) aimed to investigate the effects of pre-sleep protein supplementation on professional cyclists during a training camp, focusing on the timing of protein intake and its impact. The research involved a three-arm randomized controlled trial with twenty-four U23 cyclists. They were divided into groups consuming 40g of casein protein before sleep, 40g casein in the afternoon, or an isoenergetic placebo before sleep. Regarding sleep, the Hooper Index, which includes a sleep quality subscale, showed no significant changes across the groups. Sleep quality remained statistically unchanged throughout the study (p = 0.148), indicating that neither pre-sleep protein nor afternoon protein had a meaningful effect on sleep quality compared to the placebo. Additionally, the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes (RESTQ-Sport) assessed stress and recovery markers, including sleep quality and disturbed breaks during sleep. These measures did not show significant differences between the groups, further supporting the conclusion that pre-sleep protein supplementation did not influence sleep compared to other supplementation strategies. Overall, the study found no evidence that pre-sleep protein supplementation improved or worsened sleep quality during a short-term, high-training-load period in professional cyclists. Despite the findings that a significant increase in training loads during the camp lead to elevated indicators of fatigue and decreased performance and a high protein intake (>2.5 g/kg. BM on average) of participants, no significant differences were observed between the protein supplement groups and the placebo in any of the outcomes. The study highlighted the need for further research to confirm the benefits of pre-sleep protein supplementation in endurance athletes, particularly under strenuous training conditions. The lack of significant effects observed in this study could, again, be attributed to the already high dietary protein intake of the cyclists, exceeding recommended levels. This is a similar hypothesis to Ferguson et al., (2022) with tryptophan competing with other with other large neutral amino acids for transport across the blood brain barrier (Fernstrom, 2013). Future studies could explore the impact of restricting dietary protein intake or adjusting timing of protein intake to determine its potential benefits in endurance athletes with different dietary profiles.

Another comparable outcome was seen with 6 male elite athletes and their sleep quality not improving (MacInnis, 2020). The athletes partook in a study to investigate the impact of consuming α-lactalbumin (LA), a whey protein rich in tryptophan, on sleep quality in cyclists. Participants consumed either 40 g of LA or an isonitrogenous CP supplement 2 hours before sleep. Sleep quality was assessed using wrist-based actigraphy. The results showed no significant differences between the LA and CP groups in total time in bed, total sleep time, or sleep efficiency. Therefore, pre-sleep consumption of LA did not improve sleep quality in the studied cyclists. Again, questioning the efficacy of a protein specific, tryptophan rich interventions is required if elite athletes are already meeting the nutrient targets required.

Vitamin B12, Zinc and Iron

Condo et al., (2022) et al., examined the associations between nutrient intake and sleep in elite female athletes. The study revealed that certain nutrients, such as iron, zinc & vitamin B12, were linked to improved SE. Vitamin B12 potentially contributes to melatonin secretion, pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is involved in the synthesis of serotonin from tryptophan and niacin (vitamin B3) may stimulate a tryptophan sparing effect (Peuhkuri et al., 2012). Niacin can be synthesized endogenously from tryptophan via the Kynurenine Pathway, therefore, consuming an adequate amount of niacin is necessary to inhibit 2,3-dioxygenase activity eliciting a tryptophan sparing effect, increasing its availability for synthesis serotonin and melatonin (Peuhkuri et al., 2012). Folate (vitamin B9) and pyridoxine are involved in the conversion of tryptophan into serotonin (Ordóñez et al., 2016). The reduced form of folate (5-methyltetratrahydrofolate) increases tetrahydrobiopterin, a co-enzyme of tryptophan-5-hydroxylase, which converts tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) (Ordóñez et al., 2016). Pyridoxine’s role in the conversion of tryptophan into serotonin is related to the amino acid decarboxylase which speeds up the conversion rate of 5-HT to serotonin (Ordóñez et al., 2016). Mixed effects have been observed, with different doses of cobalamin (vitamin B12) on sleep-wake rhythms and delayed sleep phase syndrome (a significant delay in circadian rhythm), while no effect was observed for sleep duration (Roehrs & Roth, 2001).

Kardasis et al., (2023) highlights the critical role of iron in athletic performance, emphasizing that impaired iron levels can hinder performance by affecting cellular respiration and metabolism. In contrast to Condo et al., (2022), Kardasis et al., (2023) doesn't directly link iron supplementation to improved sleep however, maintaining optimal iron levels is essential for overall well-being, particularly in females meeting the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of more than 18mg/d (Kardasis et al., 2023).

Zinc, however, does show promise in promoting sleep outcomes by potentially contributing to the modulation of neurotransmitters such as GABA, which promote relaxation and sleep and play a role in the synthesis of melatonin (Cherasse & Urade, 2017; Edwards et al., 2024; Jazinaki et al., 2024). Adequate zinc levels may support optimal melatonin production, facilitating better sleep quality. Edwards et al., (2024) investigated the impact of a zinc-containing supplement, ZMA (zinc magnesium aspartate) which contains zinc, magnesium and vitamin b6, on sleep quality and morning performance in recreationally trained males. Participants received an acute dose of ZMA before bedtime, and results indicated improvements in SOL and SE compared to a placebo group. These findings suggest that zinc supplementation may enhance sleep quality, potentially benefiting athletic recovery. In summary, vitamin b12 and zinc may play a direct role in promoting sleep quality in elite female athletes with avoiding iron deficiency being the primary goal.

Carbohydrate Intake Pre-Sleep

High GI carbohydrate intake before bed has been hypothesized to influence sleep through serotonin secretion, a precursor to melatonin (Afaghi et al., 2007; Porter & Horne, 1981). Carbohydrate intake can elevate plasma tryptophan levels, a key factor in serotonin production, but evidence on its efficacy for improving sleep in elite athletes remains inconclusive. A key finding seems to be that total diet quality may be more important than CHO timing or type as several studies suggest that overall dietary intake has a greater influence on sleep than manipulating carbohydrate timing or GI. Daniel et al., (2019) found that in nine male basketball players, total food intake had a stronger effect on sleep parameters than altering carbohydrate intake at night. Similarly, Falkenberg et al., (2021) and Condo et al., (2022) found mixed results regarding carbohydrate manipulation before bed in males and female elite athletes, respectively, highlighting the need for a well-balanced dietary approach rather than focusing solely on CHO timing.

There are also mixed effects of high carbohydrate intake on sleep quality. Killer et al., (2017) examined the impact of high-carbohydrate (HCHO) vs. moderate-carbohydrate (CON) intake in 13 trained cyclists over a 9-day intensified training period. While the HCHO group maintained performance and mood, they experienced increased WASO, movement time and reduced SE, despite spending more time in bed. Similarly, Greenwalt et al., (2023) noted a potential negative association between high carbohydrate intake and reduced SE, suggesting that excessive CHO consumption before sleep may impair sleep quality in Division 1 NCAA female soccer players during an entire season.

When considering timing and GI considerations, timing of carbohydrate intake appears to play a role in sleep outcomes. Afaghi et al., (2007) found that a high-GI meal consumed 4 hours before bedtime significantly shortened SOL compared to a low-GI meal or a high-GI meal taken 1 hour before bed. These findings, though based on non-athletic men, align with earlier research (Porter & Horne, 1981) and could be relevant for elite athletes training late in the evening. Vlahoyiannis et al., (2024) investigated personalized dietary plans combined with exercise training, finding significant improvements in sleep quality across different carbohydrate distribution strategies. While all groups (Sleep Low-No Carbohydrates (SL-NCHO), Sleep High-Low Glycaemic Index (SH-LGI), and Sleep High-High Glycaemic Index (SH-HGI)) experienced better sleep metrics, TST and REM sleep were enhanced regardless of CHO type or timing. This suggests that overall energy balance and training adaptation may be more critical than specific carbohydrate strategies.

In summary the practical considerations for elite athletes should be to carefully plan carbohydrate intake to meet energy and recovery demands while minimizing potential sleep disturbances. High carbohydrate intake close to bedtime may increase TST and SE but could also elevate WASO (Condo et al., 2022). Additionally, Falkenberg et al., (2021) reported that while higher CHO intake generally supports sleep, excessive sugar consumption and long gaps between meals may negatively impact TST, potentially indicating under-recovery. The relationship between pre-sleep carbohydrate intake and sleep outcomes in elite athletes remains complex and inconsistent. While some evidence suggests benefits of high-GI CHO intake when consumed at the right time (Afaghi et al., 2007) other studies highlight potential sleep disturbances linked to excessive CHO intake (Greenwalt et al., 2023; Killer et al., 2017). Instead of focusing solely on CHO timing or GI, athletes should prioritize overall dietary quality, energy availability, and recovery strategies to optimize sleep and performance.

Meeting Energy Demands and Timing

Falkenberg et al., (2021) investigated the relationship between nutrient intake, meal timing, and sleep in elite male AFL players over a 10-day period. Key findings related to the effects of timing and type of food on sleep concluded that a longer gap between the last meal and bedtime was associated with shorter TST. This suggests that delaying food intake too much before sleep could reduce sleep duration. However, consuming meals too close to bedtime led to more disturbed sleep, indicated by an increase WASO. In contrast to Ferguson et al., (2022) and Valenzuela et al., (2023), evening protein intake was, in fact, associated with a shorter SOL, meaning athletes fell asleep faster. This effect may be due to the amino acid composition of proteins, particularly those high in tryptophan. Higher evening sugar, intake, however, was linked to shorter TST, suggesting that excessive sugar before bed might negatively impact sleep duration. Higher total daily protein intake was associated with longer WASO and reduced SE however, indicating that high protein consumption might lead to more fragmented sleep. Higher total energy intake was also correlated with longer SOL, meaning it took longer to fall asleep. Similarly, Eroğlu et al., (2024) focused on the relationship between dietary nutrients and sleep quality in elite athletes however it was found that good sleepers had higher intakes of energy, protein, and tryptophan compared to poor sleepers. It was concluded by noting that tailored interventions may be required to promote sleep quality and the efficacy of a protein specific, tryptophan rich interventions may not be required if elite athletes are already meeting the nutrient targets required (Ferguson et al., 2022; MacInnis, 2020).

Greenwalt et al., (2023) approached the topic from a different angle by exploring the effects of pre-sleep nutrition intake on sleep quality and recovery in female soccer players. Contrary to the positive outcomes seen with kiwifruit (Doherty, Madigan, Nevill, et al., 2023) and TCJ (Chung et al., 2022), this study found that pre-sleep consumption of protein, fat or carbohydrates did not significantly affect sleep duration or recovery metrics. This suggests that the impact of pre-sleep nutrition on sleep outcomes may vary depending on the specific nutrients consumed and their quantities again highlighting the need for further tailored interventions.

Probiotics

The study by Harnett et al., (2021) examined the effects of a multispecies probiotic supplement on sleep quality and muscle soreness in elite rugby players over a 17-week period during domestic and international competition. Probiotic supplementation was associated with improved self-reported sleep quality. The elite athletes taking probiotics reported better sleep when muscle soreness decreased, suggesting a link between reduced inflammation and sleep improvement. Higher levels of CRP, an inflammatory marker, were correlated with poorer sleep quality, but this relationship was weaker in the probiotic group. Improved sleep quality correlated with better motivation and reduced muscle soreness in the probiotic group. This aligns with previous research showing that gut microbiota influences sleep quality by regulating neurotransmitters like serotonin, GABA, and melatonin (Barrett et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2015). A study in Japanese medical students found that Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 improved sleep and reduced stress (Sawada et al., 2017). Similarly, a meta-analysis by Irwin et al., (2020) suggested that probiotic supplementation could reduce inflammation and improve perceived sleep health. In conclusion, Harnett et al., (2021) suggests that long-term probiotic supplementation may enhance sleep quality in elite athletes, possibly by reducing inflammation and muscle soreness. However, further research is needed to confirm these effects across different athlete populations and training conditions.

In summary promising interventions such as kiwifruit, tart cherry juice and dairy consumption were identified as interventions for use in elite athletes as highlights in Table 5 and Table 6. Further research is needed to confirm their efficacy and explore their role in improving sleep among other elite athletic populations and support staff. Dairy and milk consumption improving sleep was limited to female athletes only so the further research examining higher doses in different ethnicities is plausible. The research regarding carbohydrate intake prior to sleep is complex with varying results with individual nutrition recommendations to meet energy demands being recommended to maintain sleep quality. The use of tryptophan rich supplementation may hold promise but there may be a ceiling effect, in elite athletes consuming >2.5g. kg -1, when competing with other LNAA. Extended probiotic supplementation may result in improved sleep scores as a bi-product of reduced muscle soreness.

Limitations

Limited sample size of randomised control trials exists within the current nutrition intervention studies on sleep in elite athletes and none exist for support staff. The small sample size (n = 11) may exclude rigorous studies undertaken in highly trained athletes or athletes in lower category demographics. Therefore, given these were excluded, single study reference points were used for kiwi fruit, tart cherry consumption and LA pre bed. No studies met the criteria for carbohydrate intake pre bed in elite athletes despite previous evidence in the area. This suggests the requirement for further research in nutrition intervention elite athletes and support staff to demonstrate if interventions that may be applicable outside the elite sport setting are beneficial inside it.

5. Conclusions

The 11 studies reviewed provide insights into the impact of nutrient interventions on sleep in elite athletes. However, no studies met the inclusion criteria for support staff or coaches. It can be hypothesized that findings from this review, along with previous literature (Curtis et al., 2024; Doherty et al., 2019; Doherty, Madigan, Warrington, et al., 2023; Ordóñez et al., 2016), may be applicable to coaches and support staff in sporting environments to enhance sleep quality given their unique work demands. While each study focused on different approaches, they collectively contribute to the understanding of how nutrition influences sleep and recovery in elite athletes. This scoping review utilized a novel approach combining the P2P Matrix (Close et al., 2019) and NUQUEST (Kelly et al., 2022) to ensure clarity in the practical application for practitioners while minimizing bias across studies. Promising interventions such as kiwifruit, tart cherry juice, and dairy were identified but further research is needed to confirm their efficacy and explore their role in improving sleep among support staff and other elite athletic populations. Future studies should focus on larger, well-designed trials across diverse elite athlete populations and support personnel. While this review provides a template for practitioners working with elite athletes (

Table 5and

Table 6), the findings emphasise the need for individualised nutritional strategies to optimise sleep and recovery in both athletes and support staff.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afaghi, A.; O’connor, H.; Chow, C.M. (2007). High-glycemic-index carbohydrate meals shorten sleep onset 1-3. https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article-abstract/85/2/426/4649589.

- Barrett, E.; Ross, R.P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Stanton, C. γ-Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2012, 113, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggins, M.; Purtill, H.; Fowler, P.; Bender, A.; Sullivan, K.O.; Samuels, C.; Cahalan, R. Sleep in elite multi-sport athletes: Implications for athlete health and wellbeing. Physical Therapy in Sport 2019, 39, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calleja-González, J.; Bird, S.; Huyghe, T.; Jukic, I.; Cuzzolin, F.; Cos, F.; Marqués-Jiménez, D.; Milanovic, L.; Sampaio, J.; López-Laval, I.; et al. The Recovery Umbrella in the World of Elite Sport: Do Not Forget the Coaching and Performance Staff. Sports 2021, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappuccio, F.P.; Cooper, D.; Delia, L.; Strazzullo, P.; Miller, M.A. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. European Heart Journal 2011, 32, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carskadon, M.A.; Dement, W.C. (2005). Chapter 2. Normal Sleep: An overview. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 5th Edition, 16–26.

- Charest, J.; Grandner, M.A. (2024). Sleep, nutrition, and supplements: Implications for athletes. Sleep and Sport: Physical Performance, Mental Performance, Injury Prevention, and Competitive Advantage for Athletes, Coaches, and Trainers, 233–269. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, R.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Association of eating habits with health perception and diseases among Chinese physicians: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Nutrition 2023, 10, 1226672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherasse, Y.; Urade, Y. Dietary Zinc Acts as a Sleep Modulator. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Choi, M.; Lee, K. Effects of Short-Term Intake of Montmorency Tart Cherry Juice on Sleep Quality after Intermittent Exercise in Elite Female Field Hockey Players: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, G.L.; Kasper, A.M.; Morton, J.P. From Paper to Podium: Quantifying the Translational Potential of Performance Nutrition Research. Sports Medicine 2019, 49, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condo, D.; Lastella, M.; Aisbett, B.; Stevens, A.; Roberts, S. Sleep duration and quality are associated with nutrient intake in elite female athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2022, 25, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Carling, C.; Tooley, E.; Russell, M. ‘Supporting the Support Staff’: A Narrative Review of Nutritional Opportunities to Enhance Recovery and Wellbeing in Multi-Disciplinary Soccer Performance Staff. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, N.V.S.; Zimberg, I.Z.; Estadella, D.; Garcia, M.C.; Padovani, R.C.; Juzwiak, C.R. Effect of the intake of high or low glycemic index high carbohydrate-meals on athletes’ sleep quality in pre-game nights. Anais Da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2019, 91, e20180107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, R.; Madigan, S.; Nevill, A.; Warrington, G.; Ellis, J.G. The Impact of Kiwifruit Consumption on the Sleep and Recovery of Elite Athletes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, R.; Madigan, S.; Warrington, G.; Ellis, J. Sleep and nutrition interactions: Implications for athletes. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, R.; Madigan, S.; Warrington, G.; Ellis, J.G. Sleep and Nutrition in Athletes. Current Sleep Medicine Reports 2023, 9, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.J.; Adam, R.L.; Drummond, D.; Gallagher, C.; Pullinger, S.A.; Hulton, A.T.; Richardson, L.D.; Donovan, T.F. Effects of an Acute Dose of Zinc Monomethionine Asparate and Magnesium Asparate (ZMA) on Subsequent Sleep and Next-Day Morning Performance (Countermovement Jumps, Repeated Sprints and Stroop Test). Nutrients 2024, 16, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, M.N.; Köse, B.; Sabur Öztürk, B. The Relationship Between Dietary Nutrients and Sleep in Elite Athletes: A Pilot Study. Spor Bilimleri Dergisi 2024, 35, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, E.; Aisbett, B.; Lastella, M.; Roberts, S.; Condo, D. Nutrient intake, meal timing and sleep in elite male Australian football players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2021, 24, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.; Aisbett, B.; Lastella, M.; Roberts, S.; Condo, D. Evening Whey Protein Intake, Rich in Tryptophan, and Sleep in Elite Male Australian Rules Football Players on Training and Nontraining Days. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2022, 32, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]